Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the perinatal outcomes of SR using radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in MC pregnancies, identified factors affecting these outcomes, and assessed the associated learning curve.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included all consecutive MC pregnancies that required RFA from September 2013 to April 2023 at our institution. The perinatal outcomes were compared on the basis of various indications, and binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the risk factors for cotwin loss. Clinical datas of two periods (2013–2018 vs. 2019–2023) were compared to demonstrate the learning curve.

Results

The 107 cases composed of 40 (37.4 %) twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), 17 (15.9 %) selective intrauterine growth restriction (sFGR), 12 (11.2 %) twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence (TRAPS), 25 (23.4 %) fetal discordant anomalies, 10 (9.3 %) elective fetal reduction (EFR), and three (2.8 %) twin anemia polycythemia sequence (TAPS) cases. The overall live birth rate for cotwins was 83.2 %. The earliest gestational age at delivery was noted in the TTTS group (p=0.021). The procedure-to-delivery interval was the shortest in the TTTS group and the longest in the EFR group (p<0.001). Comparing the 2013–2018 period with the 2019–2023 period, we noted a significant increase in the live birth rate (p=0.01) and the procedure-to-delivery interval (p=0.003), mainly due to improved outcomes in TTTS cases.

Conclusions

RFA for SR is a safe and effective method for managing complicated MC pregnancies. The type of indication affects postoperative perinatal outcomes, with TTTS showing the most adverse effects. With the increasing number of cases and accumulation of experiences with simultaneous enhancement of technique proficiency, the postprocedural outcomes can be further improved.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, assisted reproductive technologies have advanced greatly, leading to a substantial increase in the prevalence of multiple pregnancies. These pregnancies are associated with high risks of maternal and perinatal complications [1], 2] and thus are difficult to manage. Approximately 30 % of multiple pregnancies are monochorionic (MC) twin pregnancies [3], 4]. Furthermore, approximately one-third of MC twins, who share a placenta and have vascular anastomoses, may develop severe complications, including twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR), twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence (TRAPS), twin anemia polycythemia sequence (TAPS), and discordant anomalies. These complications substantially increase the risks of perinatal morbidity and mortality, including preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), intrauterine fetal death (IUFD), preterm birth, stillbirth, and neonatal death [1], 3], 5].

In MC twin pregnancies, due to the presence of placental vascular anastomoses, a life-threatening condition of one twin causes abrupt blood flow from the cotwin into the affected twin through the connecting vessels. This imbalance in circulation can trigger an immediate hypotensive and hypoxic event, resulting in the intrauterine death of or neurological injury to the unaffected twin [6], [7], [8]. Thus, selective reduction (SR) may be considered in severe fetal conditions to reduce the risk of harm, prevent the loss of the cotwin, and improve the outcomes of pregnancy [1], 9]. In addition, SR can be performed in cases of discordant fetal anomalies, high-order multiple gestations, maternal comorbidities, or even for social reasons to improve the prognosis of the surviving fetus or reduce the complications and risks associated with MC twin pregnancies.

SR can be performed using several techniques, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA), bipolar cord coagulation, microwave ablation, and interstitial laser coagulation [1], [10], [11], [12]. RFA is associated with better perinatal outcomes because it is a simple and fast procedure and the instrument used in this procedure has a small diameter [9], 12], 13].

Although numerous studies have examined the outcomes of RFA for SR and identified the factors affecting these outcomes, the results remain debatable. This variability may be attributed to the differences in the study populations and sample sizes, inconsistent surgical indications, diverse clinical conditions, and varying technical expertise levels across different centers. Since the introduction of RFA for SR in our center in 2013, we have gained extensive experience and refined our techniques. Thus, we conducted this retrospective study to evaluate and compare the perinatal outcomes of SR using RFA in complex MC pregnancies and identify factors affecting these outcomes. In addition, we present our center’s learning curve to enhance the application of RFA and provide clinical insights and recommendations for patients.

Materials and methods

Study strategy and population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Peking University First Hospital, a tertiary regional referral center for prenatal diagnosis and fetal medicine. We included all consecutive MC pregnancies that required RFA between September 2013 and April 2023. This study was approved by our Institutional Ethics Committee.

Indications for RFA reduction included TTTS stages II–IV, sFGR stages II and III, TRAPS, fetal discordant anomalies, elective fetal reduction (EFR) for multiple pregnancies with MC components, and TAPS cases.

Prior to RFA, a comprehensive ultrasound assessment covering fetuses, Doppler flow, and cervical length was conducted for all cases. Details of the RFA procedure were explained to all participants along with its potential risks, such as miscarriage, IUFD, preterm delivery, and neurological damage to the surviving twin.

RFA was performed using a 15-cm, 17-gauge electrode needle (LeVeen SuperSlim Needle Electrode System, Boston Scientific Corp., Marlborough, MA, USA) under continuous ultrasound guidance by two experienced fetal medicine doctors. The needle was percutaneously inserted into the targeted fetus’s abdominal umbilical cord insertion site. After confirming the placement, an umbrella electrode was deployed. Radiofrequency power energy was initiated at 20 W and increased by 10 W every minute. The ablation generator feedback system would automatically switch off the power once the target tissue was completely desiccated or the ablation would continue for 2–3 min after the temperature reached 100 °C. Ablation cycles were repeated using the same algorithm until the cessation of cord blood flow was confirmed by color and power Doppler. Amniocentesis and amnioreduction were performed when clinically indicated.

Patients were hospitalized for observation post-procedure, and contraction inhibitors were provided, if necessary. On the first postoperative day, an ultrasound examination was performed to evaluate the cotwin’s status, amniotic fluid, umbilical artery’s Doppler flow, middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity, and cervical length. Subsequently, the patients were discharged to their obstetrician for further ultrasound monitoring and prenatal care.

Date collection and definitions

Relevant data and information were collected from the electronic medical record or through telephone interviews. Demographic and obstetrical characteristics, main pregnancy complications, and perinatal outcomes, including live birth, miscarriage (delivery before 28 weeks without live birth), IUFD, PPROM before 28 weeks, termination of pregnancy (TOP), stillbirth (death of a fetus at or after 28 weeks), gestational age (GA) at delivery, the procedure-to-delivery interval, mode of delivery, and birth weight of newborns, were recorded and analyzed based on various indications. For analysis, cotwin survival was defined as survival up to four weeks after birth. Outcomes for both single and twin survivors (in cases of triplets) were considered collectively. Cotwin loss was defined as having no survivors, including miscarriage, IUFD, TOP, and stillbirth. Furthermore, information on potential factors affecting the survival rate of the cotwin, including GA at RFA, chorioamnionitis, order of multiple pregnancy, indications for RFA, cervical length before and after RFA, and procedural details such as amnioreduction and the number of ablation cycles, was collected and examined. On the basis of the time of operation, the data were divided into two periods (2013–2018 and 2019–2023) for comparison and to obtain the learning curve.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student’s t test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare continuous variables with and without normal distributions, respectively. For categorical variables, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used. GA at delivery and the procedure-to-delivery interval were illustrated using the Kaplan–Meier curve. The log-rank test was used to assess differences between the groups. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the potential factors affecting the survival rate of the cotwin. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (approval number: 2021 study 408-001) on October 7, 2021, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

During the study period, 108 consecutive cases underwent RFA procedures. Of these, one case lost to follow-up and thus was excluded, resulting in a total of 107 (99.1 %) cases, including 91 (85.0 %) monochorionic diamniotic twins, 2 (1.9 %) monochorionic monoamniotic twins, 9 (8.4 %) monochorionic triamniotic triplets, and 5 (4.7 %) dichorionic triamniotic triplets. All triplets were reduced to twins. The most common indication for RFA was TTTS (n=40), followed by fetal discordant anomalies (n=25), sFGR (n=17), TRAPS (n=12), EFR (n=10), and TAPS (n=3). The procedures were successfully completed in all cases, and the demographic, obstetric, and procedural details are presented in Table 1.

Demographic, obstetric, and procedural characteristics of the study subjects.

| Characteristic | Total (n=107) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age at operation, years | 30.16 ± 4.32 |

| BMI at operation, kg/m2 | 24.39 (22.54–26.67) |

| Gravidity, time | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) |

| Parity, time | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) |

| GA at operation, weeks | 22.14 (18.57–24.29) |

| ART | 11 (10.3 %) |

| Main complications | |

| Pre-eclampsia, n (%) | 1 (0.9 %) |

| Gestational hypertension, n (%) | 0 (0.0 %) |

| Chronic hypertension, n (%) | 3 (2.8 %) |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 6 (5.6 %) |

| Pre-gestational diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1 (0.9 %) |

| Chorioamnionicity | |

| MCDA | n=91 (85.0 %) |

| MCMA | n=2 (1.9 %) |

| MCTA | n=9 (8.4 %) |

| DCTA | n=5 (4.7 %) |

| Type of multiple pregnancies | |

| Twins | n=93 (86.9 %) |

| Triplets | n=14 (13.1 %) |

| Characteristics of operation | |

| Indication for RFA, n (%) | |

| TTTS | 40 (37.4 %) |

| sFGR | 17 (15.9 %) |

| TRAPS | 12 (11.2 %) |

| Discordant anomalies | 25 (23.4 %) |

| EFR | 10 (9.3 %) |

| TAPS | 3 (2.8 %) |

| Amnioreduction | |

| Yes | 30 (28.0 %) |

| No | 77 (72.0 %) |

| Number of ablation cycles | |

| ≤2 | 74 (69.2 %) |

| >2 | 33 (30.8 %) |

-

Data are given as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (interquartile range). GA, gestational age; BMI, body mass index; ART, assisted reproduction techniques; MCDA, monochorionic diamniotic; DCDA, dichorionic diamniotic; MCMA, monochorionic monoamniotic; MCTA, monochorionic triamniotic; DCTA, dichorionic triamniotic; TTTS, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome; sFGR, selective fetal growth restriction; TRAPS, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence; EFR, elective fetal reduction; TAPS, twin anemia–polycythemia sequence.

Overall perinatal outcomes following RFA

In this study, all newborns survived up to four weeks, resulting in an overall cotwin survival rate of 89/107 (83.2 %). The median GA at delivery was 35.43 (31.14–37.71) weeks, and the mean procedure-to-delivery interval was 84.82 ± 44.27 days. The average birth weight of the newborns was 2,493.2 ± 668.60 g. We noted 18 (16.8 %) cases of cotwin losses, including five (4.7 %) instances of IUFD, with three (2.8 %) occurring within one week of RFA, eight (7.5 %) miscarriages (none within two weeks after RFA), four (3.7 %) TOP, and one (0.9 %) stillbirth. TOP was considered in cases of genetic abnormalities or dysplasia in the cotwin, including one case of Klinefelter syndrome and one case of oligoamnios in the TTTS group, one case of 45X mosaicism, and one case of XXY combined with a LAMB1 gene mutation in the discordant anomaly group. The stillbirth occurred at 28+1 weeks of gestation during a preterm delivery at a local hospital. Four (3.7 %) cases experienced PPROM before 28 weeks, and in three (2.8 %) of these cases, PPROM occurred within two weeks following RFA (Table 2).

Perinatal outcomes and post-procedure complications.

| Variable | All (n=107) |

|---|---|

| GA at delivery, weeks | 35.43 (31.14–37.71) |

| Interval from operation to delivery, days | 84.82 ± 44.27 |

| Pregnancies with live birth | 89 (83.2 %) |

| GA at live birth ≤33+6 weeks | 19 (21.3 %) |

| GA at live birth 34–36+6 weeks | 29 (32.6 %) |

| GA at live birth ≥37 weeks | 41 (46.1 %) |

| PPROM (<28 weeks) | 4 (3.7 %) |

| Gestational age at PPROM (<28 weeks) | 21.43 (15.93–26.50) |

| Interval from operation to PPROM (<28 weeks) | 9.0 (0.5–25.3) |

| PPROM within two weeks post-RFA | 3 (2.8 %) |

| IUFD | 5 (4.7 %) |

| Interval from operation to IUFD, days | 3.0 (1.0–28.0) |

| IUFD within one week post-RFA | 3 (2.8 %) |

| Miscarriage | 8 (7.5 %) |

| Miscarriage within two weeks post-RFA | 0 |

| Interval from operation to miscarriage | 25.5 ± 9.81 |

| TOP | 4 (3.7 %) |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Vaginal, n (%) | 68 (63.6 %) |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 39 (36.4 %) |

| Stillbirth (≥28 weeks) | 1 (0.9 %) |

| Total live born neonates, n | 100 |

| Newborn weight, ga | 2,493.2 ± 668.60 |

-

aThree newborns with unknown body weight. Data are given as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (interquartile range). GA, gestational age; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membranes; IUFD, intrauterine fetal death; TOP, termination of pregnancy.

Perinatal outcomes of RFA according to indications

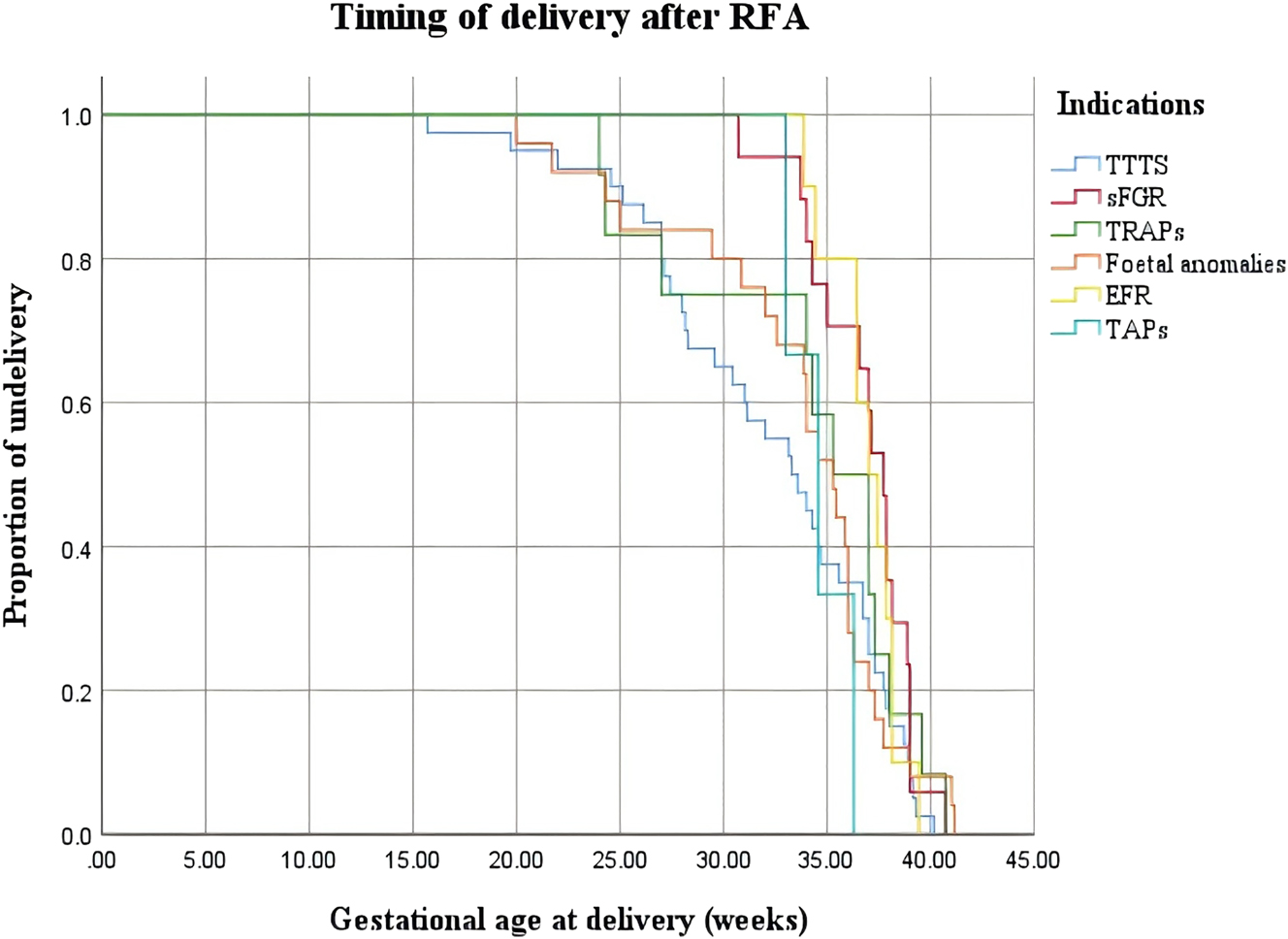

As presented in Table 3, the GA at the time of the procedure for the EFR group (17.64 [17.04–18.96] weeks) was the smallest among the six groups (p=0.005). The survival rates in the TTTS, sFGR, TRAPS, fetal discordant anomaly, EFR, and TAPS groups were 75.0 % (30/40), 100.0 % (17/17), 75.0 % (9/12), 80.0 % (20/25), 100.0 % (10/10), and 100.0 % (3/3), respectively, with the TTTS and TRAPS groups having the lowest rates. The GA at delivery for the TTTS group was the smallest among the six groups (33.43 [27.57–37.21] weeks, p=0.021). The procedure-to-delivery interval was the shortest (60.0 [25.5–103.8] weeks) in the TTTS group and the longest (135.0 [126.5–143.3] weeks, p<0.001) in the EFR group among the six groups. Of the four cases of PPROM before 28 weeks, three occurred in the TTTS group, with two within one week of RFA, and one in the EFR group. Moreover, of the eight miscarriages, five were in the TTTS group and three in the TRAPS group. No significant differences were noted in PPROM before 28 weeks, PPROM within two weeks after RFA, IUFD, miscarriage, TOP, and stillbirth across all the six groups (p>0.05). The Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrated that the TTTS group had a significantly lower proportion of ongoing pregnancies and a higher proportion of early deliveries after RFA than the other groups (Figures 1 and 2).

Perinatal outcomes and post-procedure complications based on indications.

| Variable | TTTS (n=40) | sFGR (n=17) | TRAPS (n=12) | Discordant anomalies (n=25) | EFR (n=10) | TAPS (n=3) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA at operation, weeks | 22.43 (19.71–24.54) | 20.71 (17.64–25.14) | 21.29 (17.57–23.04) | 22.43 (21.21–25.29) | 17.64 (17.04–18.96) | 24.57 (22.57–25.21) | 0.005 |

| GA at delivery, weeks | 33.43 (27.57–37.21) | 37.71 (34.64–38.93) | 36.14 (28.75–37.82) | 35.29 (31.43–36.64) | 37.21 (35.93–38.14) | 34.57 (33.79–35.43) | 0.021 |

| Pregnancies with live birth | 30 (75.0 %) | 17 (100.0 %) | 9 (75.0 %) | 20 (80.0 %) | 10 (100.0 %) | 3 (100.0) | 0.097 |

| GA at live delivery, weeks | 34.81 ± 3.72 | 36.86 ± 2.54 | 37.02 ± 2.26 | 35.64 ± 2.94 | 36.91 ± 1.72 | 34.62 ± 1.64 | 0.125 |

| GA at live birth ≤33+6 weeks | 11 (36.7 %) | 2 (11.8 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 4 (20.0 %) | 1 (10.0 %) | 1 (33.3 %) | 0.127 |

| GA at live birth 34–36+6 weeks | 7 (23.3 %) | 4 (23.5 %) | 3 (33.3 %) | 10 (50.0 %) | 3 (30.0 %) | 2 (66.7 %) | 0.280 |

| GA at live birth ≥37 weeks | 12 (40.0 %) | 11 (64.7 %) | 6 (66.7 %) | 6 (30.0 %) | 6 (60.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.086 |

| Operation-to-delivery interval, days | 60.0 (25.5–103.8) | 112.0 (77.0–137.5) | 91.0 (51.0–139.0) | 81.0 (48.5–109.5) | 135.0 (126.5–143.3) | 73.0 (71.5–80.0) | 0.000 |

| PPROM (<28 weeks) | 3 (7.5 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 1 (10 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.414 |

| PPROM within two weeks post-RFA | 2 (5.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 1 (10 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.440 |

| IUFD | 2 (5.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 3 (12.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.578 |

| IUFD within one week post-RFA | 1 (2.5 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 2 (8.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.749 |

| Miscarriage | 5 (12.5 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 3 (25.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.063 |

| TOP | 2 (5.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 2 (8.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.888 |

| Stillbirth (≥28 weeks) | 1 (2.5 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 1.000 |

-

Data are given as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (interquartile range). GA, gestational age; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; TTTS, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome; sFGR, selective fetal growth restriction; TRAPS, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence; EFR, elective fetal reduction; TAPS, twin anemia–polycythemia sequence; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membranes; IUFD, intrauterine fetal death; TOP, termination of pregnancy. The definition for the significance of bold value is p<0.05.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of different indications based on the procedure-to-delivery interval. The TTTS group had a significantly lower proportion of remaining undelivered after RFA compared to other groups.

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves of different indications based on the GA of delivery. The TTTS group had a significantly higher proportion delivered at early GA after RFA compared to other groups.

Factors affecting perinatal outcomes following RFA

Logistic regression was performed to identify risk factors for cotwin loss following RFA (Table 4). The results of univariate logistic regression revealed that cervical length after RFA<25 mm was the only significant factor (p=0.032; odds ratio, 4.800). However, this factor was not found to be significant in multivariable analysis after adjustment for confounders.

Univariate and multivariate analysis to confirm possible risk factors of cotwin loss after RFA.

| Variable | Survival n=89 |

Loss n=18 |

Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95 % CI) | p-Value | Odds ratio (95 % CI) | p-Value | |||

| GA at RFA | ||||||

| ≤24 weeks (n=78) | 62 (69.7 %) | 16 (88.9 %) | 1.461 (0.511–4.175) | 0.479 | 9.156 (0.920–91.097) | 0.059 |

| >24 weeks (n=29) | 27 (30.3 %) | 2 (11.1 %) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Chorionicity | ||||||

| Monochorionic n=102 (95.3 %) | 85 (95.5 %) | 17 (94.4 %) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Dichorionic n=5 (4.7 %) | 4 (4.5 %) | 1 (5.6 %) | 1.250 (0.131–11.887) | 0.846 | 0.880 (0.001–13.227) | 0.341 |

| Type of multiple pregnancies | ||||||

| Twins (n=93) | 77 (86.5 %) | 16 (88.9 %) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Triplets (n=14) | 12 (13.5 %) | 2 (11.1 %) | 0.802 (0.163–3.937) | 0.786 | 3.083 (0.158–60.213) | 0.458 |

| Indication for RFA | ||||||

| TTTS II (n=10) | 7 (7.9 %) | 3 (16.7 %) | Reference | Reference | ||

| TTTS III (n=19) | 16 (18.0 %) | 3 (16.7 %) | 0.438 (0.070–2.728) | 0.376 | 0.650 (0.082–5.136) | 0.683 |

| TTTS IV (n=11) | 7 (7.9 %) | 4 (22.2 %) | 1.333 (0.214–8.288) | 0.758 | 0.804 (0.098–6.580) | 0.839 |

| sFGR II (n=6) | 6 (6.7 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | N/A | 0.999 | N/A | 0.999 |

| sFGR III (n=11) | 11 (12.4 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | N/A | 0.999 | N/A | 0.999 |

| TRAPS (n=12) | 9 (10.1 %) | 3 (16.7 %) | 0.778 (0.119–5.100) | 0.793 | 0.584 (0.053–6.449) | 0.661 |

| Discordant anomalies (n=25) | 20 (22.5 %) | 5 (27.8 %) | 0.583 (0.110–3.099) | 0.527 | 0.673 (0.098–4.597) | 0.686 |

| EFR (n=10) | 10 (11.2 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | N/A | 0.999 | N/A | 0.999 |

| TAPS (n=3) | 3 (3.4 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | N/A | 0.999 | N/A | 0.999 |

| CL before RFA<25 mm | ||||||

| Yes (n=7) | 4 (4.5 %) | 3 (16.7 %) | 4.250 (0.863–20.933) | 0.075 | 11.419 (0.691–188.821) | 0.089 |

| No (n=100) | 85 (95.5 %) | 15 (83.3 %) | Reference | Reference | ||

| CL after RFA<25 mm | ||||||

| Yes (n=9) | 5 (5.6 %) | 4 (22.2 %) | 4.800 (1.147–20.085) | 0.032 | 5.182 (0.728–36.892) | 0.100 |

| No (n=98) | 84 (81.5 %) | 14 (77.8 %) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Amnioreduction (n=30) | ||||||

| Yes (n=30) | 22 (24.7 %) | 8 (44.4 %) | 0.410 (0.144–1.169) | 0.096 | 1.157 (0.258–5.180) | 0.849 |

| No (n=77) | 67 (75.3 %) | 10 (55.6 %) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Number of ablation cycles | ||||||

| ≤2 (n=74) | 61 (68.5 %) | 13 (72.2 %) | 1.193 (0.388–3.673) | 0.758 | 0.681 (0.165–2.818) | 0.596 |

| >2 (n=33) | 28 (31.5 %) | 5 (27.8 %) | Reference | Reference | ||

-

OR, odds ratio; N/A, not applicable; GA, gestational age; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; MCDA, monochorionic diamniotic; DCDA, dichorionic diamniotic; MCMA, monochorionic monoamniotic; MCTA, monochorionic triamniotic; DCTA, dichorionic triamniotic; TTTS, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome; sFGR, selective fetal growth restriction; TRAPS, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence; EFR, elective fetal reduction; TAPS, twin anemia–polycythemia sequence; CL, cervical length.

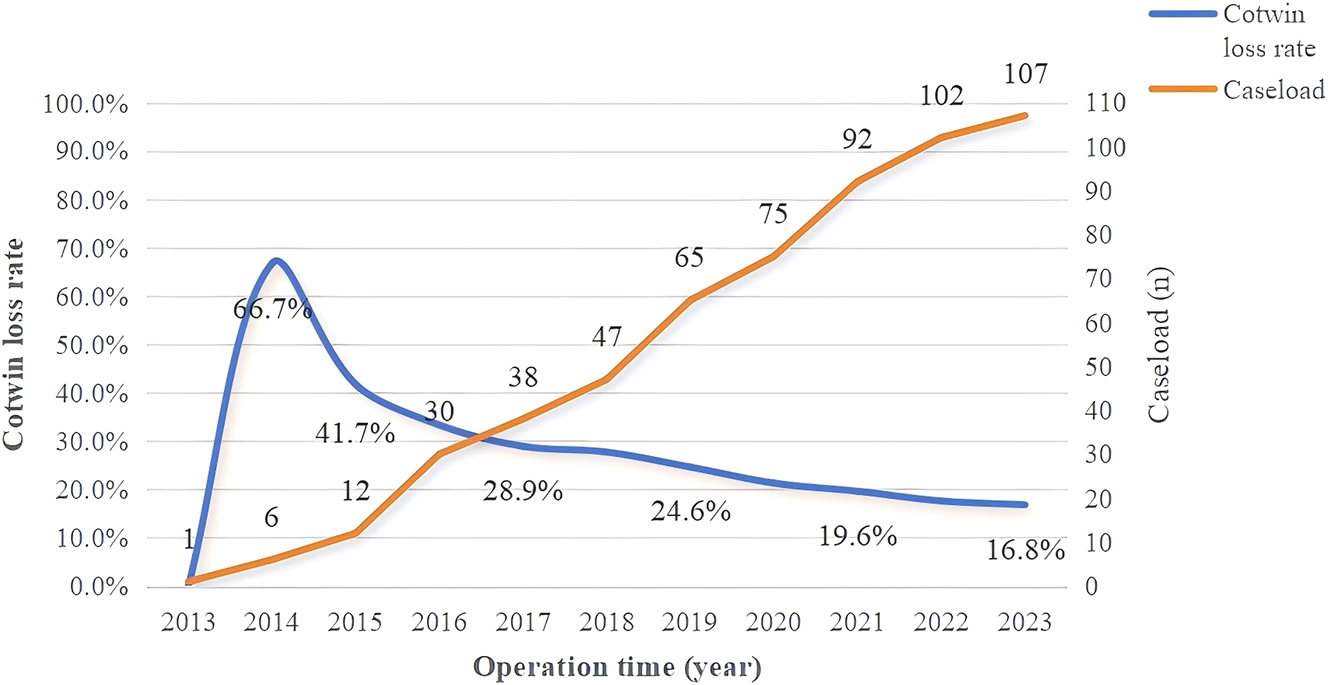

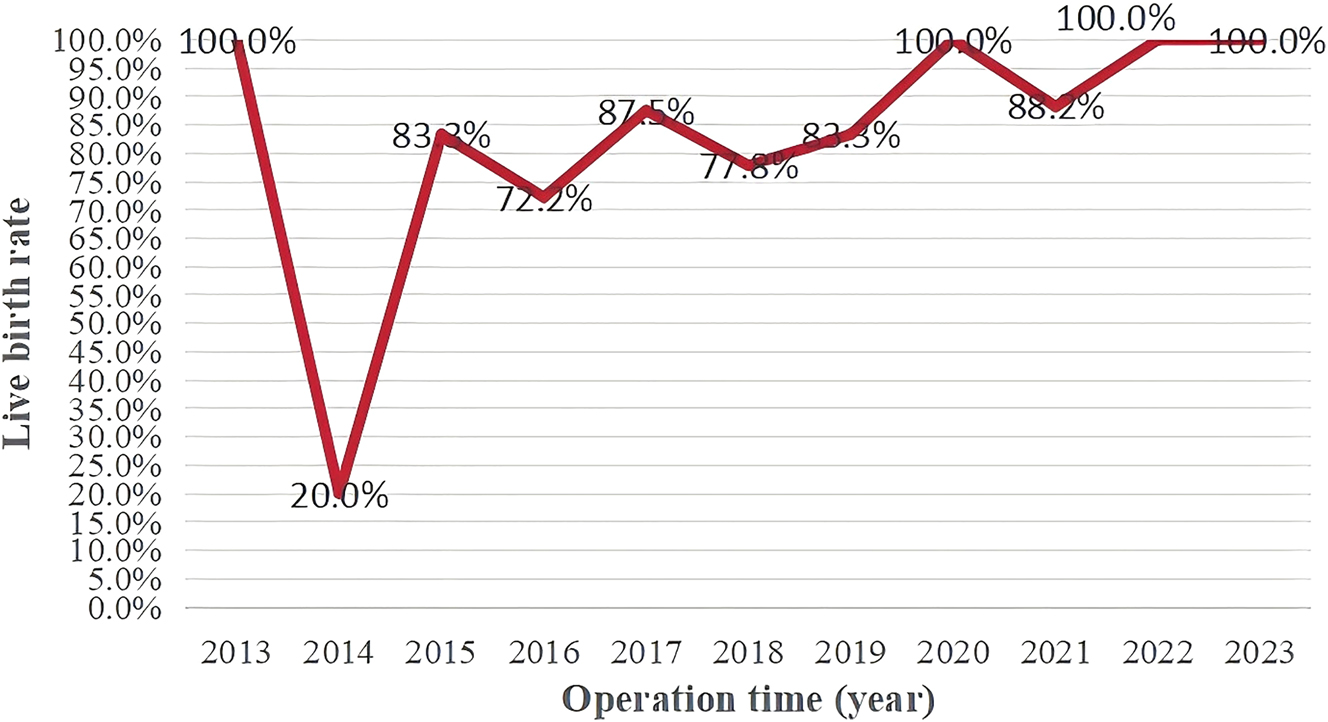

Comparison of outcomes throughout various time periods and learning curve

As depicted in Figure 3, the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing illustrates changes in the cotwin loss rate and caseload over the study period. During the 10-year period, the overall cotwin loss rate decreased to 16.8 %, with a notable decline in the earlier years before stabilizing around 2018. In addition, the annual survival rate fluctuated but gradually increased, reaching approximately 90 % in the last three years (Figure 4). Accordingly, we divided the cases into two periods for analysis: period 1 (2013–2018) and period 2 (2019–2023). Table 5 presents a comparison of perinatal outcomes between the two periods.

The changes of cotwin loss rate and caseload over the past years.

Survival rate in each year during the study period.

Comparison of obstetric characteristics and perinatal outcomes following RFA of the two periods.

| Variable | Period 1 (n=47) | Period 2 (n=60) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at operation, years | 29.00 (27.00–33.00) | 30.00 (28.00–32.00) | 0.275 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.54 (22.12–26.67) | 24.17 (22.76–27.17) | 0.853 |

| Gravidity, time | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.81 |

| Parity, time | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.937 |

| GA at operation, weeks | 22.86 (19.00–25.71) | 21.36 (18.07–23.54) | 0.032 |

| ART | 1 (2.1 %) | 10 (16.7 %) | 0.021 |

| Chorioamnionicity | |||

| MCDA | 44 (93.6 %) | 47 (78.3 %) | 0.058 |

| MCMA | 1 (2.1 %) | 1 (1.7 %) | |

| MCTA | 2 (4.3 %) | 7 (11.7 %) | |

| DCTA | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 5 (8.3 %) | |

| Type of multiple pregnancies | |||

| Twins | 45 (95.7 %) | 48 (80.0 %) | 0.020 |

| Triplets | 2 (4.3 %) | 12 (20.0 %) | |

| Indication for RFA, n (%) | |||

| TTTS | 19 (40.4 %) | 21 (35.0 %) | 0.173 |

| sFGR | 6 (12.8 %) | 11 (18.3 %) | |

| TRAPS | 8 (17.0 %) | 4 (6.7 %) | |

| Discordant anomalies | 12 (25.5 %) | 13 (21.7 %) | |

| EFR | 2 (4.3 %) | 8 (13.3 %) | |

| TAPS | 0 (0.0 %) | 3 (5.0 %) | |

| Perinatal outcome | |||

| GA at delivery, weeks | 34.71 (28.00–37.29) | 36.00 (33.75–37.86) | 0.133 |

| Interval from operation to delivery, days | 73.00 (23.00–101.00) | 100.00 (70.00–129.00) | 0.003 |

| Pregnancies with survival | 34 (72.3 %) | 55 (91.7 %) | 0.010 |

| GA at live delivery, weeks | 37.00 (34.39–38.04) | 36.29 (34.00–37.86) | 0.836 |

| GA at live birth ≤33+6 weeks | 8 (23.5 %) | 11 (20.0 %) | 0.792 |

| GA at live birth 34–36+6 weeks | 8 (23.5 %) | 21 (38.2 %) | 0.171 |

| GA at live birth ≥37 weeks | 18 (52.9 %) | 23 (41.8 %) | 0.383 |

| Interval from operation to live delivery, days | 90.41 ± 38.40 | 102.00 ± 35.08 | 0.148 |

| PPROM (<28 weeks) | 3 (6.4 %) | 1 (1.7 %) | 0.318 |

| PPROM within two weeks post-RFA | 3 (6.4 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.082 |

| IUFD | 3 (6.4 %) | 2 (3.3 %) | 0.652 |

| IUFD within one week post-RFA | 3 (6.4 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.082 |

| Miscarriage | 8 (17.0 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.001 |

| TOP | 2 (4.3 %) | 2 (3.3 %) | 1.000 |

| Stillbirth (≥28 weeks) | 1 (2.1 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | NA |

-

Data are given as median (interquartile range), or n (%). GA, gestational age; BMI, body mass index; ART, assisted reproduction techniques; MCDA, monochorionic diamniotic; DCDA, dichorionic diamniotic; MCMA, monochorionic monoamniotic; MCTA, monochorionic triamniotic; DCTA, dichorionic triamniotic; TTTS, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome; sFGR, selective fetal growth restriction; TRAPS, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence; EFR, elective fetal reduction; TAPS, twin anemia–polycythemia sequence; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membranes; IUFD, intrauterine fetal death; TOP, termination of pregnancy. The definition for the significance of bold value is p<0.05.

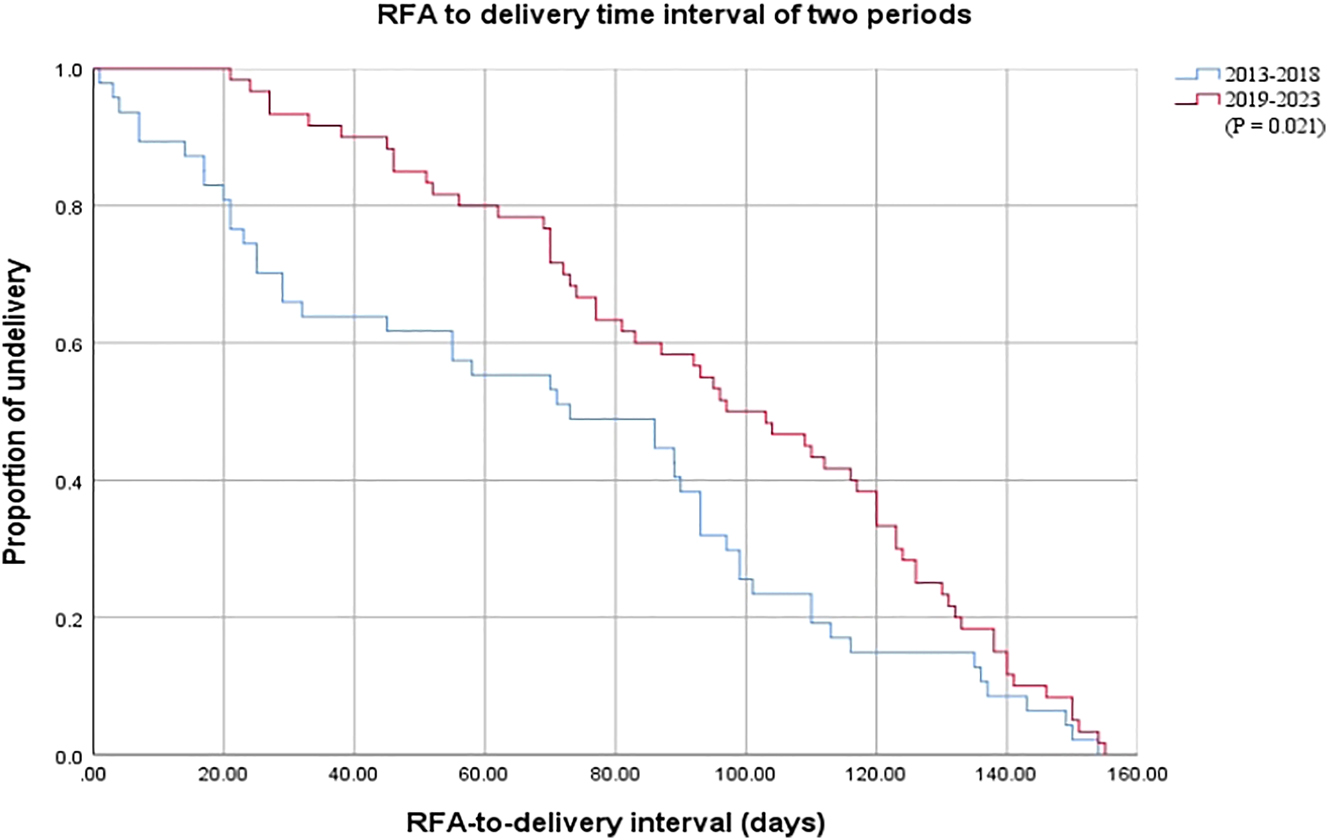

The survival rate in period 2 was significantly higher than that in period 1 (72.3 vs. 91.7 %, p=0.01), with the procedure-to-delivery interval also being higher in period 2 [73.00 (23.00–101.00) days vs. 100.00 (70.00–129.00) days, p=0.003]. The miscarriage rate in period 2 declined to 0.0 % from 17.0 % in period 1 (p=0.001), with the only stillbirth occurring in period 1. Rates of PPROM before 28 weeks, PPROM within two weeks of RFA, cotwin IUFD, and TOP did not significantly differ between the groups (p>0.05). The Kaplan–Meier curves indicated a higher proportion of ongoing pregnancies following RFA in period 2 than in period 1 (p=0.021, Figure 5).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of two periods after RAF. There was a higher proportion of undelivered pregnancies following RFA in period 2 compared with period 1 (p=0.021).

Table 6 presents a comparison of the perinatal outcomes between the two periods (2013–2018 vs. 2019–2023) for each indication, showing significant differences only in TTTS as the indication of RFA. In the TTTS group, the procedure-to-delivery interval was significantly longer in period 2 than in period 1 (29.00 [21.00–90.00] days vs. 95.00 [42.00–121.50] days, p=0.006), and the survival rate increased from 63.2 % in period 1–85.7 % in period 2. In addition, we noted a decrease in the miscarriage rate in period 2 (26.3 vs. 0.0 %, p=0.018) compared with period 1.

Comparison of the perinatal outcomes of two periods according to indications.

| Perinatal outcomes | Period | TTTS | % | SIUGR | % | TRAPS | % | Discordant anomalies | % | EFR | % | TAPS | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live birth (n=89) | Period 1 | 12/19 | 63.2 % | 6/6 | 100.0 % | 5/8 | 62.5 % | 9/12 | 75.0 % | 2/2 | 100.0 % | 0/0 | – |

| Period 2 | 18/21 | 85.7 % | 11/11 | 100.0 % | 4/4 | 100.0 % | 11/13 | 84.6 % | 8/8 | 100.0 % | 3/3 | 100.0 % | |

| p-value | 0.148 | – | 0.491 | 0.645 | – | – | |||||||

| GA at delivery, weeks | Period 1 | 31.00 (26.14–35.57) | 38.50 (37.54–39.00) | 37.00 (24.97–39.18) | 34.93 (29.79–36.75) | 35.43 (33.85–37.00) | – | ||||||

| Period 2 | 34.28 (30.00–37.93) | 36.57 (34.00–37.86) | 34.79 (34.07–36.79) | 35.85 (32.93–37.64) | 37.64 (36.43–38.14) | 34.57 (33.79–35.43) | |||||||

| p-value | 0.083 | 0.098 | 0.808 | 0.470 | 0.267 | – | |||||||

| Interval from operation to delivery, days | Period 1 | 29.00 (21.00–90.00) | 97.00 (78.25–138.75) | 91.00 (30.00–141.25) | 72.00 (9.50–106.75) | 126.50 (116.00–137.00) | – | ||||||

| Period 2 | 95.00 (42.00–121.50) | 120.00 (77.00–140.00) | 98.00 (69.25–136.50) | 83.00 (61.00–113.00) | 135.50 (130.50–147.75) | 73.00 (71.50–80.00) | |||||||

| p-value | 0.006 | 0.884 | 1.000 | 0.270 | 0.533 | – | |||||||

| PPROM within two weeks post-RFA (n=3) | Period 1 | 2/19 | 10.5 % | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/2 | 50.0 % | – | – |

| Period 2 | 0/21 | 0.0 % | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0/8 | 0.0 % | – | – | |

| p-value | 0.219 | – | – | – | 0.200 | – | |||||||

| IUFD with one week (n=3) | Period 1 | 1/19 | 5.3 % | – | – | – | – | 2/12 | 16.7 % | – | – | – | – |

| Period 2 | 0/21 | 0.0 % | – | – | – | – | 0/13 | 0.0 % | – | – | – | – | |

| p-value | 0.475 | – | – | 0.220 | – | – | |||||||

| Miscarriage (n=8) | Period 1 | 5/19 | 26.3 % | – | – | 3/8 | 37.5 % | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Period 2 | 0/21 | 0.0 % | – | – | 0/4 | 0.0 % | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| p-value | 0.018 | – | 0.491 | – | – | – | |||||||

| TOP (n=4) | Period 1 | 1/19 | 5.3 % | – | – | – | – | 1/12 | 8.3 % | – | – | – | – |

| Period 2 | 1/21 | 4.8 % | – | – | – | – | 1/13 | 7.7 % | – | – | – | – | |

| p-value | 1.000 | – | – | 1.000 | – | – | |||||||

| Stillbirth (≥28 weeks) (n=1) | Period 1 | 1/19 | 5.3 % | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Period 2 | 0/21 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| p-value | 0.475 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

-

Data are given as median (interquartile range), or n (%). GA, gestational age; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; MCDA, monochorionic diamniotic; DCDA, dichorionic diamniotic; MCMA, monochorionic monoamniotic; MCTA, monochorionic triamniotic; DCTA, dichorionic triamniotic; TTTS, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome; sFGR, selective fetal growth restriction; TRAPS, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence; EFR, elective fetal reduction; TAPS, twin anemia–polycythemia sequence; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membranes; IUFD, intrauterine fetal death; TOP, termination of pregnancy. The definition for the significance of bold value is p<0.05.

Discussion

RFA, a minimally invasive technique characterized by ease of access and application, has become a well-established method for managing complex MC pregnancies.

In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Gaerty et al. [11] reported a survival rate of 76.8 % (67.6–87.2 %, 238/310) for RFA reduction in MC pregnancies. Similarly, Li et al. [14] reviewed the studies on RFA reduction in multiple pregnancies conducted from 2008 to 2021 and determined the mean and maximum survival rates of 76.55 % ± 8.01 % and 91.9 % [13], respectively. They also reported their survival rate as 78.76 %. The overall survival rate in the current study was 82.3 %, which is comparable to that reported in previous studies. These results collectively indicate that RFA is an effective approach for SR in complicated MC multiple pregnancies, consistently demonstrating a favorable cotwin survival rate of over 70 %.

In our study, the median GA at delivery was 35.4 weeks, which is in agreement with the findings of Gaerty et al. [11], who reported a mean GA at delivery of 34.7 ± 1.7 weeks, and Li et al. [14], who reported the median GA at delivery in the range of 31.6–36.8 weeks.

PPROM is a major concern following intrauterine inventions. In this study, three of the four cases of PPROM before 28 weeks occurred within two weeks of RFA, potentially contributing to miscarriages and other adverse outcomes. In addition, IUFD is an undesirable outcome of RFA, typically occurring within 24–48 h of surgery; however, it can also occur weeks later [15], 16]. Previous studies have indicated that the IUFD rate ranges from 4.5 to 14.7 % [11], 14], [17], [18], [19], and in this study, this rate was 4.7 % (5/107), with two cases occurring within 48 h following RFA. Early IUFD likely occurs due to interfetal hemorrhage and incomplete vessel occlusion, leading to transfusion of the cotwin’s blood to the moribund fetus [12], 15], 20]. The causes of later IUFD instances remain unclear. Moreover, miscarriage, with reported incidence rates ranging from 5.3 to 17.3 % [11], [21], [22], [23], is another undesirable outcome of RFA. Some studies have suggested that the location of the targeted fetus and the indications for RFA can affect the likelihood of miscarriage [21], 24]. In our cohort, all eight miscarriage cases were associated with TTTS or TRAPS as indications for RFA, aligning with the findings of previous studies. However, additional studies are warranted to clarify these relationships.

In the current cohort, the most common indication for RFA was TTTS, followed by discordant anomalies, sFGR, and TRAPS. Li et al. [14] demonstrated that cotwin loss after RFA may be associated with the indications for RFA. In addition, our findings indicated that indications can affect the perinatal outcomes of the procedure.

In our study, the TTTS and TRAPS groups had the lowest overall survival rate (75.0 %). Furthermore, among the six groups, the TTTS group exhibited the worst perinatal outcomes, with the smallest GA at delivery, the shortest RFA to delivery interval, and a higher frequency of adverse consequences. A meta-analysis by Wang et al. [25] reported a survival rate of 69.3 % for TTTS, which is significantly lower than that for other RFA indications. Similarly, a systematic review by Donepudi et al. [26] reported a lower cotwin survival rate for TTTS cases undergoing RFA. Previous systematic reviews by Gaerty et al. [11] and others [22], 23], 27], 28] have also indicated that TTTS outcomes were less favorable than those of other RFA indications. This trend is likely related to the pathophysiological mechanisms of TTTS, where the hemodynamic imbalance may adversely affect both fetuses. The donor twin experiences hypovolemia, oliguria, and oligohydramnios, potentially leading to hypertension and renal dysfunction, whereas the recipient twin experiences hypervolemia and circulatory overload, which can cause polyuria and polyhydramnios, ultimately leading to hypertension and cardiac dysfunction [3], 29], 30]. Thus, the morbidity of the cotwin might not be preventable through the reduction of the affected twin. In addition, the high amniotic fluid pressure caused by severe polyhydramnios increases the risks of PPROM, miscarriage, and preterm delivery [31].

Fetoscopic laser photocoagulation is the preferred treatment for TTTS [8], and RFA is frequently preferred for cases where laser therapy is not feasible, due to factors such as the advanced Quintero stage, proximity of umbilical cord insertion sites, poorly accessible anastomoses owing to the position of the placenta or fetuses, and parental preference. At our facility, we provide individualized counseling to all pregnant women with TTTS and their families based on the specific clinical situation of the woman and the fetuses. The procedure details and possible risks associated with both fetoscopic laser surgery and RFA are fully explained to the pregnant women and their families, as well as the possible outcomes of the fetuses after the procedures, and the choice is made by the women and their families after consideration. This study included 10 TTTS II cases, 19 TTTS III cases, and 11 TTTS IV cases, who preferred to undergo RFA owing to multiple factors, including fetal factors such as advanced stage, fetal anomaly, growth restriction, severe fetal hydrops and heart failure, maternal factors such as history of cesarean section, advanced age, and severe maternal complication, or concerns regarding the difficulties and risks of fetoscopic laser surgery, fetal prognosis, and costs (Supplementary Table 1).

Zhang et al. [32] reported a survival rate of 70 % for the pump twin in TRAPS cases treated with RFA, a finding echoed by Rahimi-Sharbaf et al. [33]. We obtained a similar result in our study. Treating TRAPS can be challenging due to significant tissue edema, potentially necessitating multiple circulations and a longer duration of operation [24], 34]. In addition, a pump twin experiencing persistently high output can lead to polyhydramnios, which can increase the risks of PPROM and miscarriage. In our study cohort, polyhydramnios was noted in two miscarriage cases in the TRAPS group, potentially contributing to adverse outcomes.

We identified factors affecting perinatal outcomes following RFA. Univariate logistic regression indicated that a cervical length of <25 mm after RFA may be the only risk factor for cotwin loss after RFA. Given the established association between short cervical length and increased risks of miscarriage and preterm birth [35], [36], [37], [38], cervical length may be a risk factor for unfavorable outcomes following RFA. However, in multiple pregnancies, its significance may be intertwined with other variables, and thus it may become nonsignificant after multivariate adjustment.

We also examined other potential factors affecting the perinatal outcomes, including various maternal and procedural characteristics. However, univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the impact of these covariates was not discernible. The plausible explanation for the cotwin loss following RFA is the presence of several, interconnected, and mutually reinforcing factors, warranting additional studies to clarify the associations between various risk factors and the adverse outcomes after reduction by RFA.

Although the precise causes of cotwin loss after RFA remain to be clarified, we acknowledge the significant effects of proficiency in the use of refined techniques on perinatal outcomes following RFA. Thus, we reviewed data from our center, spanning 10 years since the introduction of RFA. During the study period, as case numbers increased, the annual survival rate was found to gradually increase. Comparing the perinatal outcomes from the earlier years with the recent ones, we noted a significant increase in survival rates, an extension in the procedure-to-delivery interval, and a reduction in miscarriage rates across the cohort. A sub-analysis based on indications revealed a similar increase in the procedure-to-delivery interval and a decrease in miscarriage rates, particularly in TTTS cases. This significant increase in the survival rate may be partially attributed to advancements in antenatal management and ultrasound technology for early diagnosis, as well as to a learning curve effect in the RFA procedure. The enhanced perinatal outcomes, especially in TTTS cases, provide strong evidence of our clinical progress.

At the inception of the application of a new technique, the accumulation of cases and procedural experiences contributes to the enhancement of technical proficiency, as observed in the first few years of period 1, with further improvements in perinatal outcomes, as observed in period 2. The dynamic improvement in survival rates could be due to the initial tacking of technically simpler cases, then progressing to more challenging ones, which might temporarily lower survival rates until technical improvements lead to subsequent increases. The findings demonstrated that as a center’s experience enriches, the survival rate increases significantly, indicating the effectiveness of refined techniques in improving perinatal outcomes following RFA. These results emphasize the significance of mastering advanced techniques in optimizing RFA treatment outcomes.

The strengths of our study include the inclusion of consecutive cases over a decade, providing a relatively large sample size. In addition, we covered nearly all types of MC pregnancy complications, enabling comparisons of perinatal outcomes across various indications and an exploration of factors affecting RFA outcomes. Moreover, we demonstrated the expertise and learning curve of our center, which may be beneficial for other centers and serve as a reference to improve clinical management and patient counseling.

This study has some limitations that should be addressed. First, due to the retrospective nature of the study, the documentation of certain procedural details such as whether the instruments crossed the placenta during the operation was missing in some of the early cases. Besides, it has a observational design and was conducted in a single center. Moreover, because most of our patients were referred to our center from across the country and continued their perinatal care and delivery with their local obstetricians, the detailed information about delivery and newborns could not be obtained, and the long-term neurological development outcomes of the surviving fetus remain unknown. Additional large-scale multicenter prospective studies of thorough recording operative details during operations with the long-term follow-up of survivors’ neurodevelopmental outcomes should be conducted to identify factors affecting outcomes following RFA more comprehensively.

Conclusions

This study describes our 10-year experience of SR in complex MC pregnancies using RFA at a tertiary regional referral center for prenatal diagnosis and fetal medicine. Our findings highlight that RFA for fetal reduction is a safe and effective method for managing complicated MC pregnancies. The postoperative perinatal outcomes may be affected by the indications for RFA, with TTTS resulting in the most undesirable outcomes. The accumulation of experience with the increasing number of cases, contributing to improved technical proficiency, can further enhance the postprocedural outcomes of RFA.

Funding source: National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Interdepartmental Clinical Research Project of Peking University First Hospital)

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2022CR21

Funding source: National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Scientific Research Seed Fund of Peking University First Hospital)

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2022SF51

-

Research ethics: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013), and has been approved by Peking University First Hospital’s Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

-

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: The study was concepted and designed by SL, YS, and ZL. Data collection and analysis were performed by SL. The draft of the manuscript was written by SL, and ZL critically revised the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work is supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Scientific Research Seed Fund of Peking University First Hospital) (2022SF51) and the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Interdepartmental Clinical Research Project of Peking University First Hospital) (2022CR21).

-

Data availability: The datasets analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of the local Ethics Committee.

References

1. Sebghati, M, Khalil, A. Reduction of multiple pregnancy: counselling and techniques. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2021;70:112–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.06.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Di Renzo, GC, Yang, H. Multiple pregnancy: an increasingly important situation in the current era. Matern Fetal Med 2022;4:233. https://doi.org/10.1097/fm9.0000000000000123.Search in Google Scholar

3. Micheletti, T, Eixarch, E, Bennasar, M, Martinez, JM, Gratacos, E. Complications of monochorionic diamniotic twins: stepwise approach for early identification, differential diagnosis, and clinical management. Matern Fetal Med 2021;3:42–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/fm9.0000000000000076.Search in Google Scholar

4. Liu, J, Liu, Q, Zhao, J, Li, D, Zhou, Y. The controversies and challenges in the management of twin pregnancy: from the perspective of International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Guidelines. Matern Fetal Med 2022;4:255–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/fm9.0000000000000170.Search in Google Scholar

5. Gestations, M, Twin, T. Higher-order multifetal pregnancies: ACOG practice bulletin, number 231. Obstet Gynecol 2021;137:e145–62.10.1097/AOG.0000000000004397Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Morris, RK, Mackie, F, Garces, AT, Knight, M, Kilby, MD. The incidence, maternal, fetal and neonatal consequences of single intrauterine fetal death in monochorionic twins: a prospective observational UKOSS study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0239477. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239477.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Conte, G, Righini, A, Griffiths, PD, Rustico, M, Lanna, M, Mackie, FL, et al.. Brain-injured survivors of monochorionic twin pregnancies complicated by single intrauterine death: MR findings in a multicenter study. Radiology 2018;288:582–90. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018171267.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Knijnenburg, PJC, Lopriore, E, Oepkes, D, Vreeken, N, Tan, RNGB, Rijken, M, et al.. Neurodevelopmental outcome after fetoscopic laser surgery for twin-twin transfusion syndrome: a systematic review of follow-up studies from the last decade. Matern Fetal Med 2020;2:154–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/fm9.0000000000000033.Search in Google Scholar

9. Donepudi, R, Hessami, K, Nassr, AA, Espinoza, J, Sanz Cortes, M, Sun, L, et al.. Selective reduction in complicated monochorionic pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis of different techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226:646–55.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.10.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Bebbington, M. Selective reduction in complex monochorionic gestations. Am J Perinatol 2014;31:S51–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1383852.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Gaerty, K, Greer, RM, Kumar, S. Systematic review and metaanalysis of perinatal outcomes after radiofrequency ablation and bipolar cord occlusion in monochorionic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:637–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.04.035.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Abdel-Sattar, M, Chon, AH, Llanes, A, Korst, LM, Ouzounian, JG, Chmait, RH. Comparison of umbilical cord occlusion methods: radiofrequency ablation versus laser photocoagulation. Prenat Diagn 2018;38:110–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5196.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Shinar, S, Agrawal, S, El-Chaâr, D, Abbasi, N, Beecroft, R, Kachura, J, et al.. Selective fetal reduction in complicated monochorionic twin pregnancies: a comparison of techniques. Prenat Diagn 2021;41:52–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5830.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Li, N, Sun, J, Wang, J, Jian, W, Lu, J, Miao, Y, et al.. Selective termination of the fetus in multiple pregnancies using ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:821. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04285-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Gabby, LC, Chon, AH, Korst, LM, Llanes, A, Chmait, RH. Risk factors for Co-twin fetal demise following radiofrequency ablation in multifetal monochorionic gestations. Fetal Diagn Ther 2020;47:817–23. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509401.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Hillman, SC, Morris, RK, Kilby, MD. Co-twin prognosis after single fetal death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:928–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e31822f129d.Search in Google Scholar

17. Wang, HM, Li, HY, Wang, XT, Wang, YY, Li, L, Liang, B, et al.. Radiofrequency ablation for selective reduction in complex monochorionic multiple pregnancies: a case series. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2017;56:740–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2017.10.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Wang, H, Zhou, Q, Wang, X, Song, J, Chen, P, Wang, Y, et al.. Influence of indications on perinatal outcomes after radio frequency ablation in complicated monochorionic pregnancies: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03530-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Yinon, Y, Ashwal, E, Weisz, B, Chayen, B, Schiff, E, Lipitz, S. Selective reduction in complicated monochorionic twins: prediction of obstetric outcome and comparison of techniques. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46:670–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14879.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Mackie, FL, Rigby, A, Morris, RK, Kilby, MD. Prognosis of the co-twin following spontaneous single intrauterine fetal death in twin pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2019;126:569–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15530.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Pan, P, Huang, D, Tang, L, Yang, Z, Qin, G, Wei, H. Application and influencing factors of radiofrequency ablation in monochorionic pregnancy. Matern Fetal Med 2022;4:245–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/fm9.0000000000000163.Search in Google Scholar

22. Meng, XL, Wang, XT, Wang, HM, Wang, YY, Li, L, Li, HY. Clinical application for pregnancy outcomes of radiofrequency ablation in complex multiple pregnancies (in Chinese). Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2019;54:730–5. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567x.2019.11.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Sun, L, Zou, G, Yang, Y, Zhou, F, Tao, D. Risk factors for fetal death after radiofrequency ablation for complicated monochorionic twin pregnancies. Prenat Diagn 2018;38:499–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5269.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Yuan, PWX, Wang, Y. Selective feticide in management of complicated monochorionic twin pregnancies in second trimester (in Chinese). Chin J Perinat Med 2016;19:827–32.Search in Google Scholar

25. Wang, XQH, Shan, N. Safety of radiofrequency ablation for fetal reduction in monochorionic twin pregnancies over 26 weeks of gestation (in Chinese). Chin J Perinat Med 2019;22:657–62.Search in Google Scholar

26. Donepudi, R, Hessami, K, Nassr, AA, Espinoza, J, Cortes, MS, Belfort, MA, et al.. Co-twin survival after selective fetal reduction in complicated multiple gestations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of survival rate according to indication for intervention. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2022;274:182–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.05.028.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Shi, XM, Rao, TZ, Liu, Q, Fang, LY, Shi, LS, Huang, HM, et al.. Perinatal outcomes and influencing factors following radiofrequency ablation in multiple pregnancies (in Chinese). Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2019;54:736–40. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567x.2019.11.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Wang, JLN, Chen, M. Selective fetal reduction in multiple pregnancies: 173 cases in one center (in Chinese). J Pract Obstet Gynecol 2017;33:512–6.Search in Google Scholar

29. Mercanti, I, Boivin, A, Wo, B, Vlieghe, V, Le Ray, C, Audibert, F, et al.. Blood pressures in newborns with twin-twin transfusion syndrome. J Perinatol 2011;31:417–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2010.141.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Van Mieghem, T, Klaritsch, P, Doné, E, Gucciardo, L, Lewi, P, Verhaeghe, J, et al.. Assessment of fetal cardiac function before and after therapy for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:400.e1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.051.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Hoffman, M, Habli, M, Donepudi, R, Boring, N, Johnson, A, Moise, KJJr., et al.. Perinatal outcomes of single fetal survivor after fetal intervention for complicated monochorionic twins. Prenat Diagn 2018;38:511–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5278.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Zhang, ZT, Yang, T, Liu, CX, Li, N. Treatment of twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence with radiofrequency ablation and expectant management: a single center study in China. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018;225:9–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.03.046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Rahimi-Sharbaf, F, Ghaemi, M, Nassr, AA, Shamshirsaz, AA, Shirazi, M. Radiofrequency ablation for selective fetal reduction in complicated monochorionic twins; comparing the outcomes according to the indications. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03656-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Dadhwal, V, Sharma, KA, Rana, A, Sharma, A, Singh, L. Perinatal outcome in monochorionic twin pregnancies after selective fetal reduction using radiofrequency ablation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2022;157:340–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13785.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Ville, Y, Rozenberg, P. Predictors of preterm birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;52:23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.05.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Li, J. Cervical assessment by transvaginal ultrasound for predicting preterm birth in asymptomatic women. Matern Fetal Med 2020;2:95–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/fm9.0000000000000043.Search in Google Scholar

37. Prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: ACOG practice bulletin, number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:e65–e90.10.1097/AOG.0000000000004479Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Lim, K, Butt, K, Crane, JM. No. 257-Ultrasonographic cervical length assessment in predicting preterm birth in singleton pregnancies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2018;40:e151–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2017.11.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2024-0201).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Sex differences in lung function of adolescents or young adults born prematurely or of very low birth weight: a systematic review

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Shifts in peak month of births and socio-economic factors: a study of divided and reunified Germany 1950–2022

- The predictive role of serial transperineal sonography during the first stage of labor for cesarean section

- Gestational weight gain and obstetric outcomes in women with obesity in an inner-city population

- Placental growth factor as a predictive marker of preeclampsia in twin pregnancy

- Learning curve for the perinatal outcomes of radiofrequency ablation for selective fetal reduction: a single-center, 10-year experience from 2013 to 2023

- External validation of a non-invasive vaginal tool to assess the risk of intra-amniotic inflammation in pregnant women with preterm labor and intact membranes

- Placental fetal vascular malperfusion in maternal diabetes mellitus

- The importance of the cerebro-placental ratio at term for predicting adverse perinatal outcomes in appropriate for gestational age fetuses

- Comparing achievability and reproducibility of pulsed wave Doppler and tissue Doppler myocardial performance index and spatiotemporal image correlation annular plane systolic excursion in the cardiac function assessment of normal pregnancies

- Characteristics of the pregnancy and labour course in women who underwent COVID-19 during pregnancy

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Sonographic visualization and measurement of the fetal optic chiasm and optic tract and association with the cavum septum pellucidum

- The association among fetal head position, fetal head rotation and descent during the progress of labor: a clinical study of an ultrasound-based longitudinal cohort study in nulliparous women

- Fetal hypoplastic left heart syndrome: key factors shaping prognosis

- The value of ultrasound spectra of middle cerebral artery and umbilical artery blood flow in adverse pregnancy outcomes

- Original Articles – Neonates

- A family-centric, comprehensive nurse-led home oxygen programme for neonatal chronic lung disease: home oxygen policy evaluation (HOPE) study

- Effects of a respiratory function indicator light on visual attention and ventilation quality during neonatal resuscitation: a randomised controlled crossover simulation trial

- Short Communication

- Incidence and awareness of dysphoric milk ejection reflex (DMER)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Sex differences in lung function of adolescents or young adults born prematurely or of very low birth weight: a systematic review

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Shifts in peak month of births and socio-economic factors: a study of divided and reunified Germany 1950–2022

- The predictive role of serial transperineal sonography during the first stage of labor for cesarean section

- Gestational weight gain and obstetric outcomes in women with obesity in an inner-city population

- Placental growth factor as a predictive marker of preeclampsia in twin pregnancy

- Learning curve for the perinatal outcomes of radiofrequency ablation for selective fetal reduction: a single-center, 10-year experience from 2013 to 2023

- External validation of a non-invasive vaginal tool to assess the risk of intra-amniotic inflammation in pregnant women with preterm labor and intact membranes

- Placental fetal vascular malperfusion in maternal diabetes mellitus

- The importance of the cerebro-placental ratio at term for predicting adverse perinatal outcomes in appropriate for gestational age fetuses

- Comparing achievability and reproducibility of pulsed wave Doppler and tissue Doppler myocardial performance index and spatiotemporal image correlation annular plane systolic excursion in the cardiac function assessment of normal pregnancies

- Characteristics of the pregnancy and labour course in women who underwent COVID-19 during pregnancy

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Sonographic visualization and measurement of the fetal optic chiasm and optic tract and association with the cavum septum pellucidum

- The association among fetal head position, fetal head rotation and descent during the progress of labor: a clinical study of an ultrasound-based longitudinal cohort study in nulliparous women

- Fetal hypoplastic left heart syndrome: key factors shaping prognosis

- The value of ultrasound spectra of middle cerebral artery and umbilical artery blood flow in adverse pregnancy outcomes

- Original Articles – Neonates

- A family-centric, comprehensive nurse-led home oxygen programme for neonatal chronic lung disease: home oxygen policy evaluation (HOPE) study

- Effects of a respiratory function indicator light on visual attention and ventilation quality during neonatal resuscitation: a randomised controlled crossover simulation trial

- Short Communication

- Incidence and awareness of dysphoric milk ejection reflex (DMER)