Abstract

Dry gas seals (DGSs) are emerging as advanced forms of sealing under high-speed working conditions owing to their low wear, zero leakage, and long-life characteristics. However, it is difficult to accurately and efficiently achieve the theoretical optimal groove depth and minimum roughness requirements using existing laser technology, which limits their practical application in high-speed working conditions. Using ultrafast laser technology, the minimum laser power corresponding to the ablation threshold of the material was taken as the reference to achieve precision machining of the target groove depth. The maximum groove depth error and roughness were controlled within 4.06% and 0.425 μm, respectively. In addition, the relationship between the minimum spot diameter and continuous machining was investigated. Ultrafast laser machining experiments demonstrated that single-direction discontinuous machining could form an ordered texture, which not only improved the sealing performance but also simplified groove processing. The processing time was reduced by ∼30% compared with traditional laser processing. Finally, a quality detection and evaluation method, which can be used to scientifically determine the quality and depth of DGS grooving, is proposed. Our results provide a guideline for DGS processing and manufacturing.

1 Introduction

The main feature of a dry gas seal (DGS) is that the friction pair can be operated without contact using laser surface texturing (LST) technology [1,2,3]. In terms of structure, various textures or grooves with depths of 3–10 μm are arranged on the end face of the dynamic or static ring [4,5]. Therefore, the core technology of a DGS is reflected in the design and level of precision machining of the micrometer groove. DGS processing methods mainly include chemical corrosion, electric spark erosion, sand blasting, and LST. Among these methods, LST has become the mainstream processing method in this field owing to its high efficiency, good material adaptability, and high processing quality [6,7]. The main parameters of laser processing include laser power, minimum spot diameter, laser processing spacing, and scanning speed. The specific adjustment methods and forms of action of these laser processing parameters are detailed in Sections 2 and 4.

Groove depth, flatness, and roughness are three key parameters in DGS precision machining, and with the aid of fine grinding technology, the average roughness of the seal end face can be reduced to 0.1 μm [8]. However, the grinding method based on the contact machining mechanism cannot be used for the precision machining of microscale groove bottoms of DGSs; therefore, it is difficult to efficiently and precisely control the groove depth and roughness at the micrometer level with conventional laser machining. Relevant studies [9,10,11] showed that when the ratio of the film thickness to the root mean square of the roughness exceeds 3–4, the influence of roughness can be neglected. Greater roughness can improve the sealing opening force, gas film stiffness, and friction torque, while significantly increasing the amount of leakage. However, with an increase in rotational speed, increased roughness is harmful to the low-speed performance of the DGS.

This suggests that the effect of roughness on the DGS cannot be ignored and that the mechanism of action is complex. The relevant industrial technical standards and requirements [12] specify that the bottom roughness of a DGS should not exceed 0.8 μm. This high-quality requirement results from the theoretical depth being meaningless when the roughness is too close to the magnitude of the depth. To ensure effective guidance of theoretical research on DGSs for practical application, on the premise that the roughness meets the requirements, the grooving technology should be as accurate as possible to achieve the depth precision required by theoretical research. However, relevant literature studies [13,14,15,16,17] showed that modification of the texture of the groove bottom offers good performance improvement and is more practical in engineering, enabling improvement in the allowable roughness value of the groove bottom and reducing processing requirements. This concept provides the basis for the research conducted in this study.

Establishing a set of high-efficiency and low-cost design and processing technology to optimize the performance of a DGS is challenging to achieve. Addressing this challenge is the primary concern of this study. The contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

A precise DGS machining process with minimum roughness is established as the target based on the minimum laser power corresponding to the ablation threshold of the material.

A technical method is explored to realize precise processing of the ordered texture of the groove bottom of a DGS using an ultrafast laser based on the design of an ordered texture structure. Table 1 shows the parameters related to laser processing.

Multipoint random depth quality evaluation methodology, capable of delivering the required roughness, flatness, evaluation length, and mean square error, is proposed.

Main processing parameters of laser processing

| Nomenclature | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| V | Scanning speed (mm·s−1) | β | Helix angle (°) |

| V e | Rated scanning speed (mm·s−1) | R a | Mean roughness (μm) |

| x | Laser scanning direction | h g | Groove depth (μm) |

| y | Laser processing direction | h go | Laser single scan groove depth under certain parameters (μm) |

| S | Laser spacing (μm) | Δx | Laser spot overlap area in x-direction (μm2) |

| S x | Laser spacing in x-direction (μm) | Δy | Laser spot overlap area in y-direction (μm2) |

| S y | Laser spacing in y-direction (μm) | P | Laser power (W) |

| f | Repetition frequency (kHz) | P o | Laser power corresponding to material ablation threshold (W) |

| n | Cycle number |

|

Mean square deviation of groove depth (μm) |

| d s | Minimum spot diameter (μm) |

|

Mean square deviation of roughness (μm) |

| α | Filling angle (°) |

|

Allowable mean square deviation of groove depth (μm) |

| r o | Outer radius of the seal ring (mm) |

|

Allowable mean square deviation of roughness (μm) |

| r g | Bottom radius of the seal ring (mm) | E | Energy of a single pulse (J·cm−2) |

| r i | Inner radius of the seal ring (mm) | E 0 | Ablation threshold of the material (J·cm−2) |

| e g | Groove width of the seal ring (mm) | l r | Sampling length (mm) |

| e w | Weir width of the seal ring (mm) | m | Number of random tests |

| λ | Width ratio of the groove to the ridge (e g /e w) | Q m | Material removal per unit time (cm3·s−1) |

| N g | Spiral groove number | e | The energy density of a single pulse (J·cm−2) |

2 Experimental basis

2.1 Laser machining mechanism

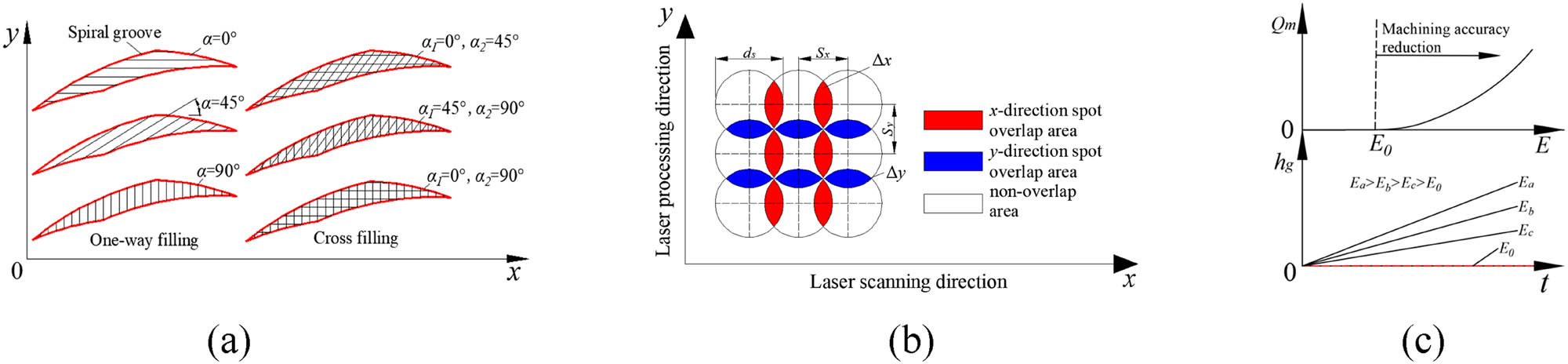

When a laser is used to process a DGS, the methods that are typically used to fill the spiral groove are one-way filling or cross-filling, as shown in Figure 1(a). The one-way filling angle α can be adjusted arbitrarily from 0° to 180°, with α = 0° and α = 90° being more commonly used. The principle of cross-filling is the same as that of one-way filling and can be regarded as a combination of two one-way fillings. Different filling angle combinations can form different cross-filling modes, among which the combination of α = 0° and α = 90° is the most common.

Parameters related to laser processing. (a) Laser filling mechanism. (b) Laser processing schematic. (c) Laser energy characteristic curve.

In the process of ultrafast laser grooving of a DGS, many parameters affect the processing accuracy. The logical relations between the parameters are shown in equations (1)–(3).

where P is the laser power, e is the energy density of a single pulse, h g is the (target) groove depth, and h go is the laser single scan groove depth for certain parameters, which can be obtained from the experiments. The subscripts x and y in S x and S y represent the scanning and processing directions, respectively, as shown in Figure 1(b). The minimum spot diameter d s is determined by the laser property, the laser spacing S x in the x-direction can be adjusted by system setting, and the laser spacing S y in the y-direction can be controlled by modifying the scanning speed V and repetition frequency f. Δx and Δy represent the laser spot overlap area in the scanning and processing directions, respectively. Whether the laser can achieve continuous machining is closely related to the spot overlap area. When S x > d s or S y > d s, Δx = 0 or Δy = 0, in which case local laser discontinuous processing occurs, which leads to uneven processing surfaces and even potholes.

2.2 Precision machining process

New ultrafast laser precision machining technology based on the minimum laser energy corresponding to the ablation threshold of the material is proposed. The technology adheres to the principle of ultrafast laser processing and takes the characteristics of the sealing material into consideration. The brief process of laser processing is as follows: First determine the silicon carbide (SiC) processing minimum ablation threshold, and adjust the laser processing power to slightly greater than the processing power corresponding to the threshold of material ablation. Then, using parallel or cross fill mode, realizing orderly processing groove in the x direction (S y > d s), y direction in order processing (S x > d s) or precision machining.

2.2.1 Laser power

Equation (1) shows that the laser energy density (E) is determined by the laser power (P) and repetition frequency (f). When the laser energy density is lower than a certain critical energy density (E < E 0), no material is removed from the specimen surface even after a long period of laser irradiation (t → ∞), and the groove depth h g and roughness R a are almost unchanged, as shown in Figure 1(c). This critical energy density is the minimum laser energy density corresponding to the ablation threshold of the material. Only when the laser energy density reaches or exceeds the minimum laser energy density (E ≥ E 0), will the surface layer of the material in the irradiated area be ablated. The longer the irradiation time, the larger the amount of material that is removed (Q m) and the deeper the groove. Moreover, at higher laser energy density, more material is removed per unit time and the processing accuracy becomes worse. In practice, different laser energy densities are obtained by changing the laser power based on a certain repetition frequency.

Clearly, the processing efficiency and quality cannot be considered simultaneously in laser processing. In actual production, the laser power needs to be selected by comprehensively considering the processing efficiency, precision requirements, and cost control.

2.2.2 Minimum spot diameter

To ensure that the processing direction and scanning direction of the spot overlap is not zero, the laser spacing in both the x- or y-directions (S x or S y ) should not be larger than the minimum spot diameter. Otherwise, discontinuous processing occurs and potholes may emerge. These will seriously affect the realization of micrometer-level groove depth, low roughness, and high planeness.

2.2.3 Scanning velocity

Scanning speed mainly affects the spot overlap area and material removal efficiency in the y-direction. On the one hand, as the scanning speed decreases, the processing efficiency increases, and also the surface processing quality decreases. On the other hand, although an increase in the scanning speed can improve the machining accuracy, when the scanning speed continues to increase, discontinuous processing and potholes may occur. There is an optimal value for the selection of scanning speed, and deviation from the optimal value in different directions will affect the processing efficiency and quality. This is an aspect that needs to be emphasized in the experiment in this work.

2.2.4 Laser spacing

Similar to scanning speed, the laser spacing also has an optimal value. In theory, the smaller the laser distance is, the greater the spot overlap will be, and the higher the processing efficiency will be. However, in practice, deviation from the optimal spacing value should result in the decreased processing efficiency due to laser beam shielding with plasma and ablated material debris. At the same time, the increase in laser spacing is limited by the spot diameter, so it is one of the tasks of this work to find out the optimal laser spacing reasonably.

2.2.5 Cycle indexes

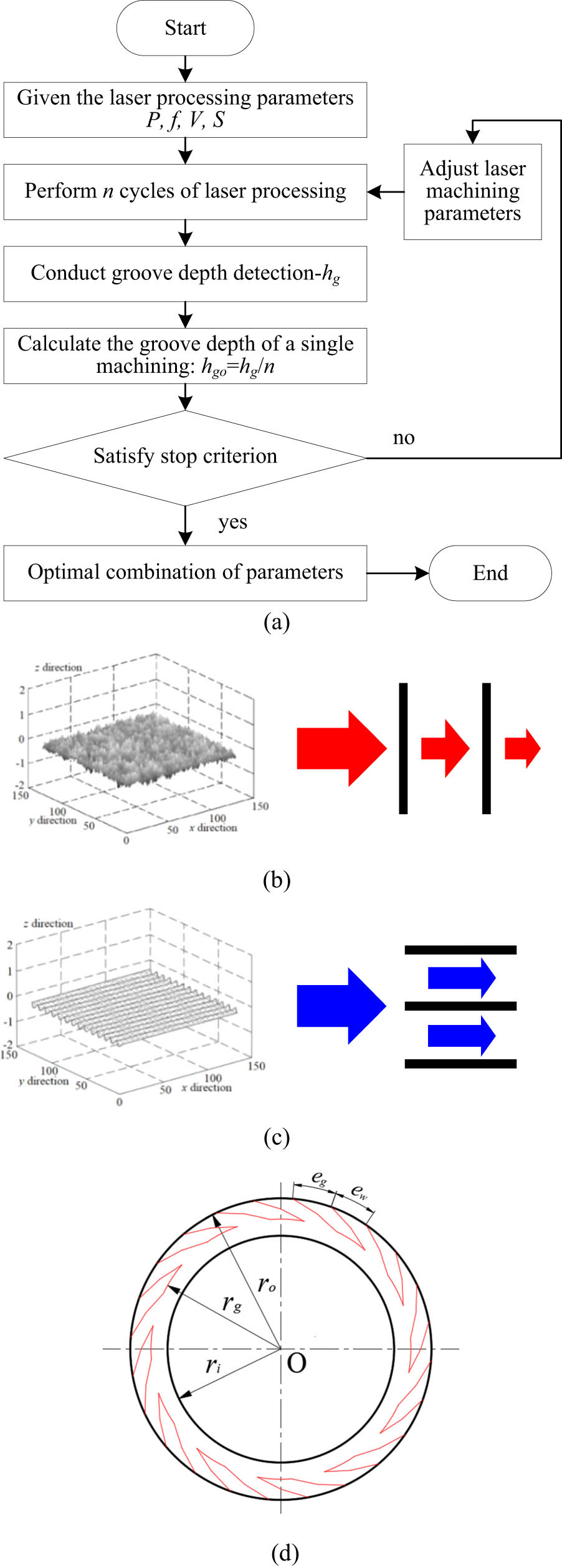

In theory, after determining the combination of laser parameters, the cycle index n can be calculated according to the single processing depth h go and the target groove depth h g: n = h g/h go. However, in practice, a single machining depth is difficult to detect and errors cannot be avoided. Moreover, the subsequent fitting calculation further amplifies the error, and the single machining depth is determined by averaging the detection results of multiple cycles. If the final fitting value h go is not ideal and inconvenient for further fitting of the target groove depth, it would be necessary to recombine the initial laser parameters until a satisfactory value is obtained for the single processing depth. A detailed flowchart is shown in Figure 2(a).

Method for determining the combination of laser parameters, three-dimensional schematic of groove bottom and schematic diagram of the logarithmic spiral groove. (a) Method for determining the combination of laser parameters. (b) Isotropic surfaces and corresponding flow patterns. (c) Anisotropic surfaces and corresponding flow patterns. (d) Schematic of a logarithmic spiral groove.

2.3 Ordered texture structure machining process

In traditional laser processing, the random roughness of the surface at the groove bottom is isotropic because the laser filling mode is mostly cross filling. A schematic of the groove bottom and its microscale flow form are shown in Figure 2(b). Under this condition, the fluid flow undergoes damping, causing the flow rate and velocity to gradually decrease owing to the damping effect. Relevant studies [18,19] have shown that the texture direction considerably influences the tribological and sealing properties of the surface of the material. By combining the flow orientation effect of the ordered texture and the dynamic pressure generation mechanism of the DGS [20,21], we propose the concept of designing the groove bottom of the DGS such that it has an ordered texture. Let us assume that the scanning path of the laser is relatively orderly according to the direction of fluid pumping and that the texture of the groove bottom after processing will also be in an overall orderly shape. A schematic of the groove bottom and flow form is shown in Figure 2(c). Here the flow form has an orientation effect, and enables the fluid to pass through the seal without a reduction in the flow rate. In particular, when the DGS is rotating at high speed, this can enhance the effects of fluid pumping and dynamic pressure. The validity of this concept has been proven by studying various groove types [22,23,24,25]. A groove bottom with an ordered texture promotes the orderly flow of fluid in the flow field and further enhances the pumping and dynamic pressure effects of the spiral groove. Based on these principles, in the present study, we discuss the way in which an ultrafast laser can be used to realize a groove bottom with an ordered texture.

In ordered texture processing, the laser filling method should first be changed; that is, it should be changed from cross-filling to parallel filling in a single direction. Then, the relevant parameters need to be adjusted to ensure that the laser spacing in the x- or y-direction exceeds the spot diameter (S x > d s or S y > d s); this is expected to result in orderly processing in a single direction. The laser spacing S x can be directly adjusted by system setting, and the laser spacing S y is determined jointly by the repetition frequency f and the scanning speed V. We experimentally adjusted the parameters and found the discontinuous processing effect corresponding to the different parameters to be quite different. Certain changes could not achieve the expected ordered texture effect. This is discussed in detail in Section 3.

2.4 Sealing sample preparation

SiC is a high-quality engineering material with high hardness, high strength, high temperature resistance, and low cost. The material is commonly used in the DGS industry. Based on these advantages, a DGS consisting of SiC was selected for research on ultrafast laser precision machining. The common type of groove in a DGS is shaped in the form of a logarithmic spiral, which is shown in equation (4).

where r is the radial coordinate of any point on the spiral groove, r g is the radius at the root of the spiral groove, β is the helix angle, and θ is the circumferential angle between the logarithmic helix at the polar diameter r and the starting point.

Two logarithmic spirals and arcs are grouped into a completed spiral groove, which is evenly distributed on the seal end face, as shown in Figure 2(d). The basic geometric parameters of the groove are listed in Table 2.

Geometric parameters of spiral groove laser machining

| Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Outer radius of the seal ring r o (mm) | 85 |

| Root radius of the seal ring r g (mm) | 65 |

| Inner radius of the seal ring r i (mm) | 60 |

| Groove width of the seal ring e g (mm) | 22.25 |

| Weir width of the seal ring e w (mm) | 22.25 |

| Width ratio of the groove to the weir λ (e g /e w) | 1 |

| Spiral groove number N g | 12 |

| Helix angle β (°) | 15 |

3 Experiments and methods

3.1 Experimental equipment

3.1.1 Laser machining equipment

According to the technical index of DGS technical conditions [26], the roughness of the groove bottom should not exceed 0.8 μm; however, it is difficult to achieve this technical requirement. Based on the advantages and characteristics of ultrafast lasers [27], the laser processing equipment chosen for this experiment was the NI-LG-3120 picosecond laser micromachining platform independently developed by the Nanjing Institute of Advanced Laser Technology. Based on the experimental test, the laser power corresponding to the silicon carbide ablation threshold (P o) is ∼6 W. Further test analysis and calculations enabled us to draw up the parameter range for ultrafast laser precision machining of DGSs. The laser equipment parameters and selection range are provided in Table 3(a).

Laser processing parameters and equipment parameters

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Textureless structure | Ordered texture | |

| (a) Parameters related to ultrafast laser precision machining | ||

| Spot diameter d s/(μm) | 15 | 15 |

| Filling mode | Cross | Parallel |

| Laser power P/(W] | 6 | 6 |

| Scanning speed V/(mm·s−1) | 1,000–2,000 | 1,000–2,000 |

| Laser spacing in scanning direction S x /(μm) | 3 | 20 |

| Frequency f/(kHz) | 100–400 | 100–400 |

| Laser spacing in processing direction S y /(μm) | 3–20 | 3–20 |

| Cycle number n | <30 | <20 |

| Manufacturer | Typ | Minimum step height | Accuracy | Measuring range in Z direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (b) Equipment parameters | ||||

| NI-LG | 3,120 | 0.5 nm | <1.5% | <6.5 μm |

| Rtec | UP-Lambda | 0.1 nm | <0.7% | 0.1–15 mm |

| Linear accuracy | Resolution scale | Repeatability | ||

| Weir | SPR2000 | ≦ ± (5 nm + 2.8%) | 1/262,144 | ≦1 nm |

3.1.2 Inspection equipment

In this study, a two-dimensional probe contact profilometer equipped with a picosecond micromachining platform was selected for groove depth detection. The principle of contact detection is to convert the change in the height of the scanning probe on the measured surface into a change in magnetic flux, which is then converted to a voltage signal as output. The measured minimum step height can reach 0.5 nm and the measurement accuracy is usually <1.5%, which meets the detection accuracy requirement. To observe the microscale morphology and flatness of the groove bottom, an UP-Lambda three-dimensional (3D) confocal profilometer (Rtec Instruments) was selected. The SPR2000 series roughness tester and its matching detection platform, developed by Shaanxi Weir Mechanical and Electrical Technology Co., Ltd, were selected as the roughness detection equipment. The linear accuracy is ≦±(5 nm + 2.8%), which meets the experimental requirements. Related equipment parameters are provided in Table 3(b).

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Laser discontinuous machining

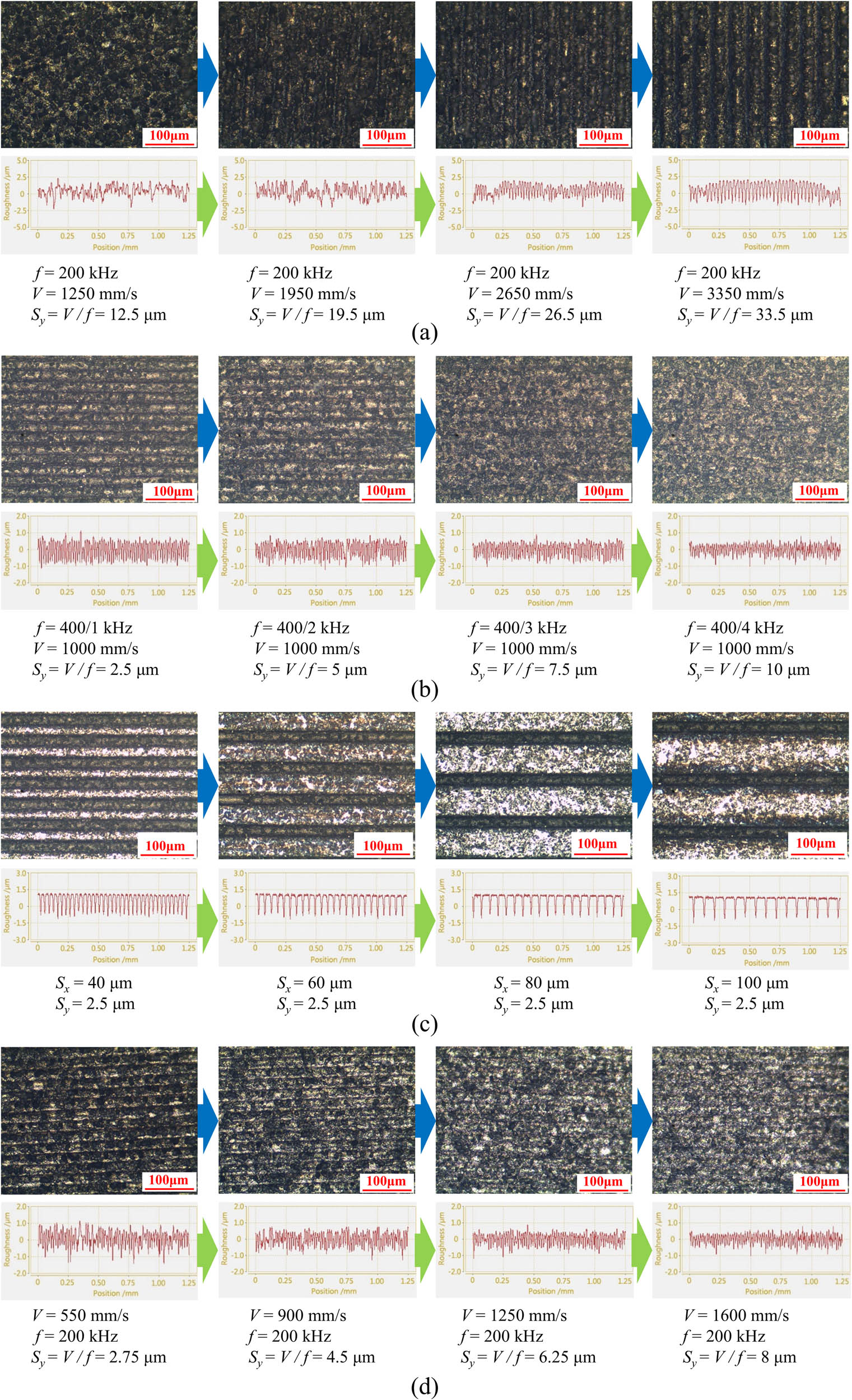

According to the theoretical analysis presented above, the condition for laser discontinuous machining is S x > d s or S y > d s, which was further analyzed and verified by conducting experiments.

4.1.1 Increasing the laser spacing in the y-direction

As shown in Figure 3(a), with the premise that S x = 3 μm < d s, S y increases as the scanning speed increases when the repetition frequency remains unchanged. Once the spacing exceeds d s as S y increases, the macroscopic structure of the ordered texture structure becomes more obvious, and the regular morphology of the microscopic structure of the ordered texture becomes more significant.

Influence of different processing parameters on the macroscopic modeling of discontinuous machining. (a) Influence of laser spacing in the y-direction (S x = 3 μm < d s = 15 μm, P = 6 W, n = 20). (b) Influence of laser spacing in the y-direction (S x = 20 μm > d s = 15 μm, P = 6 W, n = 20). (c) Influence of laser spacing in the x-direction (P = 6 W, f = 400 kHz, V = 1,000 mm·s−1, n = 16). (d) Influence of scanning speed (P = 6 W, S x = 20 μm, n = 16).

Figure 3(b) shows the opposite situation. At this time, S x > d s (S x = 20 μm > d s). When the scanning velocity remains unchanged, a decrease in the repetition frequency increases S y , the macroscopic structure of the ordered texture gradually weakens and even disappears, and the morphology amplitude of the macroscopic structure of the ordered texture also gradually becomes moderate.

The aforementioned experiments demonstrate that an ordered texture cannot be formed when S x or S y is larger than or smaller than d s at the same time. It is necessary to ensure that the laser spacing in one direction does not exceed d s and then adjust the spacing in the other direction such that the laser spacing is greater than d s, thereby obtaining a structure with a unidirectional ordered texture.

Further analysis of the microscopic morphological features of Figure 3(a) and (b) shows that, by adjusting S y with the scanning speed or frequency, the amplitude of the ordered texture is affected while the laser spacing is changed, which is not conducive to accurate regulation of a single parameter of the structure of the ordered texture.

4.1.2 Increasing the laser spacing in the x-direction

The laser spacing in the x-direction, S x , can be set directly by adjusting the laser. As shown in Figure 3(c), with the premise that S y < d s (S y = 2.5 μm < d s), a structure with an ordered texture can be obtained once S x exceeds d s. The corresponding amplitude of a texture with different S x values is constant, and the larger the value of S x , the greater the spacing between adjacent textures.

Compared with S y , S x can achieve an effective adjustment of texture spacing without changing the texture parameters (width and amplitude), and the parameters of the obtained ordered texture are more consistent. The setup for the process is both direct and convenient. It does not involve changes in the scanning speed or repetition frequency, which in turn would affect the laser energy and texture amplitude, complicating the machining and introducing uncertainties.

4.1.3 Scanning speed

To further analyze the influence of the scanning velocity, the influence thereof on the laser processing was studied based on the condition that S x > d s. Figure 3(d) shows the laser processing micromorphology at different scanning speeds when S x = 20 μm. As shown in the figure, an increase in the scanning speed also causes S y to increase. In addition, the macroscopic structure of the ordered texture becomes increasingly fuzzy and the morphology amplitude of the microscopic ordered texture decreases gradually. This is because, as S y increases, the spot coincidence rate in the y-direction decreases and the amount of material removed per unit time decreases. Based on these results, it can be concluded that, when laser processing meets the requirements of ordered texture structure, the higher the scanning speed, the smaller the amplitude of the ordered texture morphology, and the less obvious the texture characteristics are.

4.2 Laser processing and microscopic analysis of texture

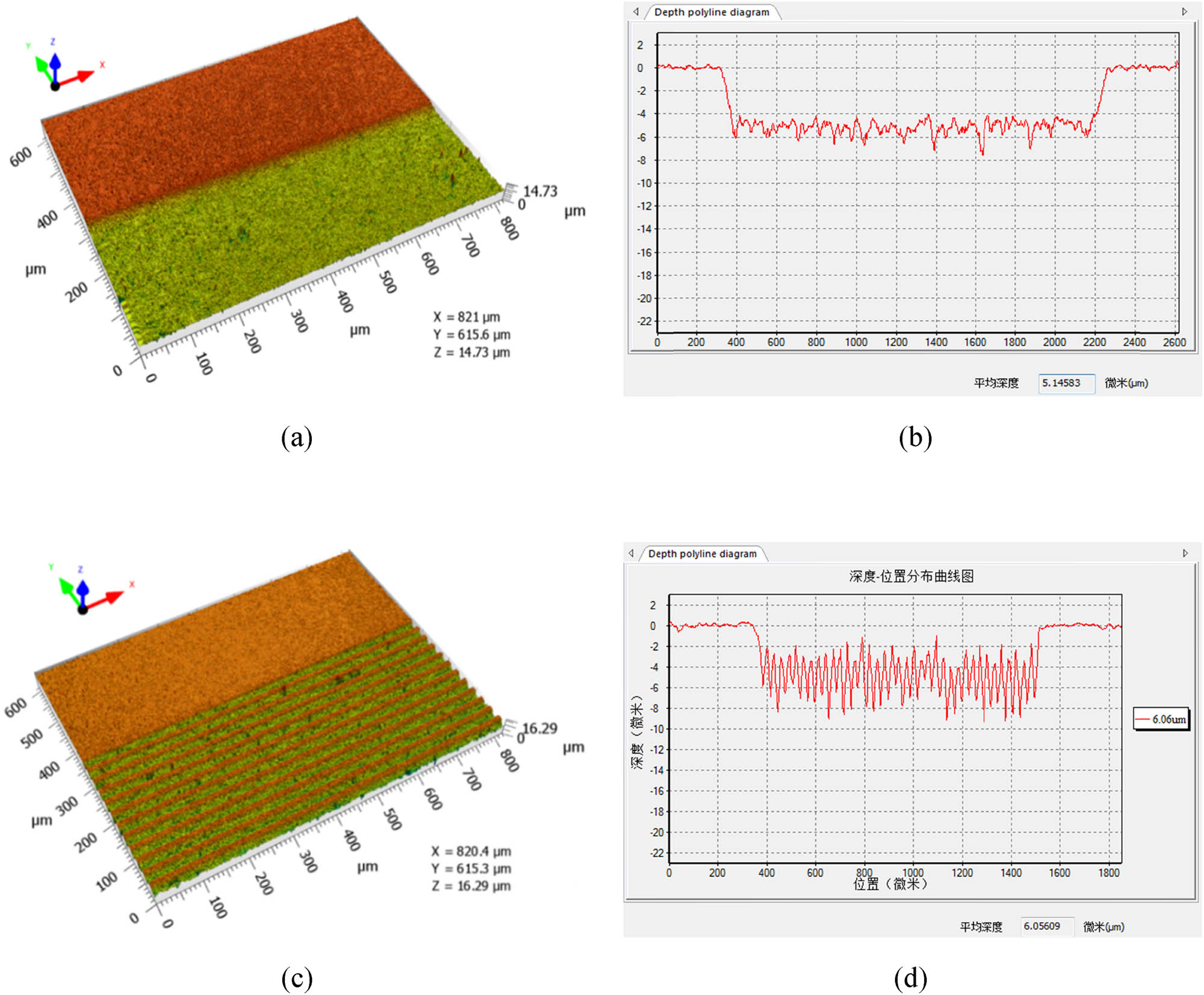

4.2.1 Precision machining of textureless structure

Figure 4(a) and (b) shows the results of 3D topography detection and groove depth detection of the textureless structure, respectively. The reddish-brown area in Figure 4(a) is the non-grooved area, which corresponds to the detection result with a depth of 0 in Figure 4(b). The surface of the non-grooved area is clearly of very high quality after fine grinding. The flatness and 3D morphology of the groove bottom in the processing zone are slightly lower than those in the non-processing zone. Compared with the processing results of the fiber laser [28,29], the amplitude interval of the groove bottom is significantly reduced (∼2 μm compared to 10 μm in the aforementioned studies), and the overall flatness and morphology are also superior.

Detection results of textureless structure and ordered texture structure. (a) 3D topography of the textureless structure. (b) Groove depth test results (P = 6 W, f = 400 kHz, V = 2,200 mm·s−1, S x = 3 μm, n = 10). (c) 3D topography of the ordered texture structure. (d) Groove depth test results (P = 6 W, f = 400 kHz, V = 2,000 mm·s−1, S x = 20 μm, n = 5).

4.2.2 Precision machining of ordered texture structure

Figure 4(c) and (d) shows the 3D confocal profilometer and groove depth detection results of the ordered texture structure, respectively. The figure shows that the ordered texture obtained based on the technical methods employed in this study has good accuracy and is easily recognizable. The results demonstrate that the amplitude range of the ordered texture structure is obviously increased, and the difference between the peak and valley of the groove bottom is large but more uniform, which is mainly affected by the sinusoidal structure of the groove bottom section. The average depth is selected as the groove depth of the ordered texture groove, which is based on the axis of sinusoidal symmetry and is representative to a certain extent.

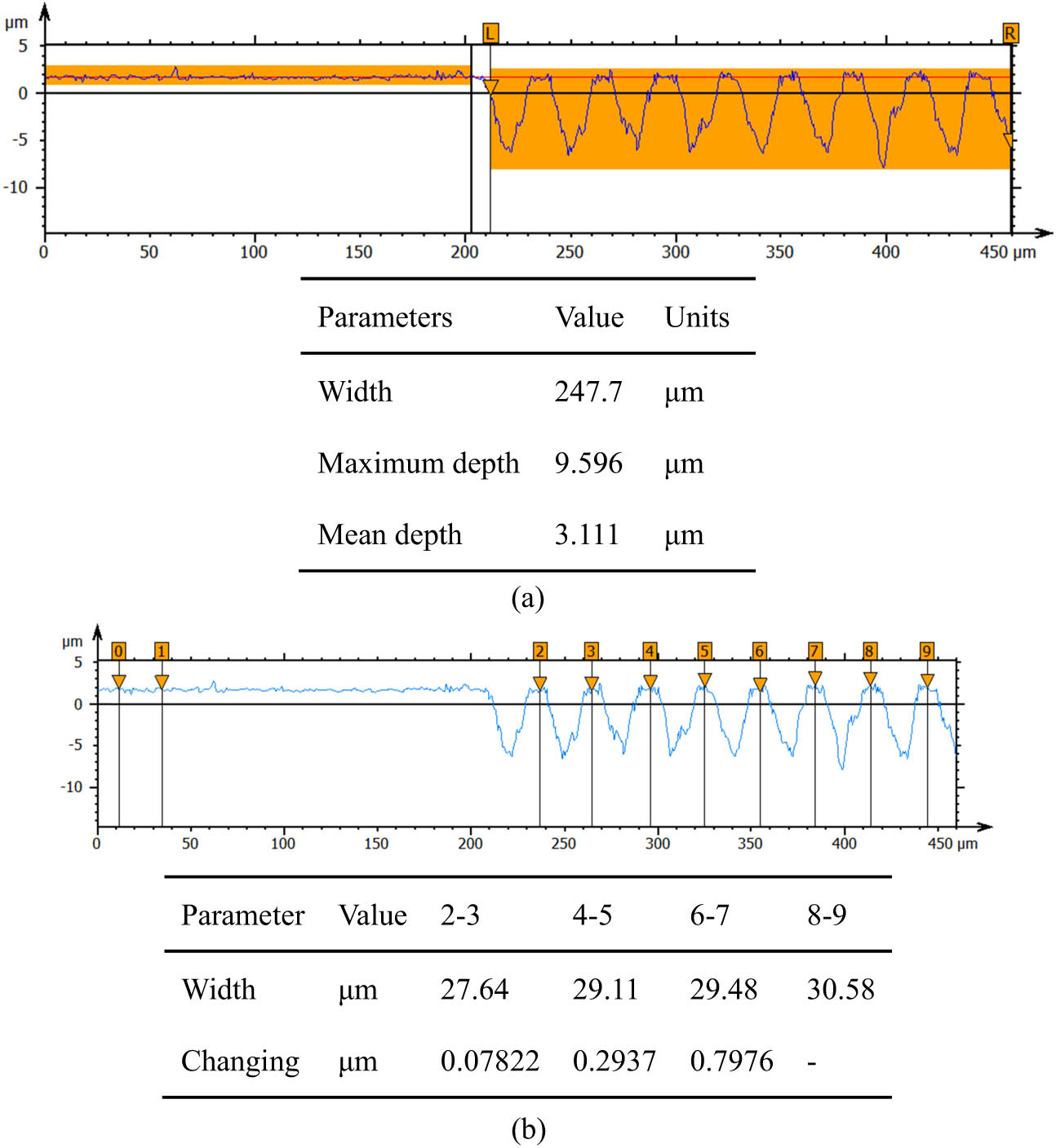

4.2.3 Microscale analysis of ordered texture

To further study the microstructure of the ordered texture structure, the depth and spacing of the microstructure were analyzed using a 3D confocal profilometer, as shown in Figure 5(a). The sinusoidal morphology features of the ordered texture were clear and consistent. Figure 5(b) shows the analysis and detection results of the texture spacing. The average texture spacing at positions 2–3, 4–5, 6–7, and 8–9 is 29.20 µm, and the maximum error is only 5.65%. These values are only used for theoretical analysis. Additional texture spacing data should be selected in the actual detection to improve the reliability of the results. This result shows that the proposed processing method to obtain the ordered texture structure more effectively ensures the consistency of the microstructure. Furthermore, the proposed processing method is able to realize precision machining of the ordered texture of DGSs.

Detection results of 3D morphometry of the ordered texture structure. (a) Groove depth test results. (b) Texture parameter detection results.

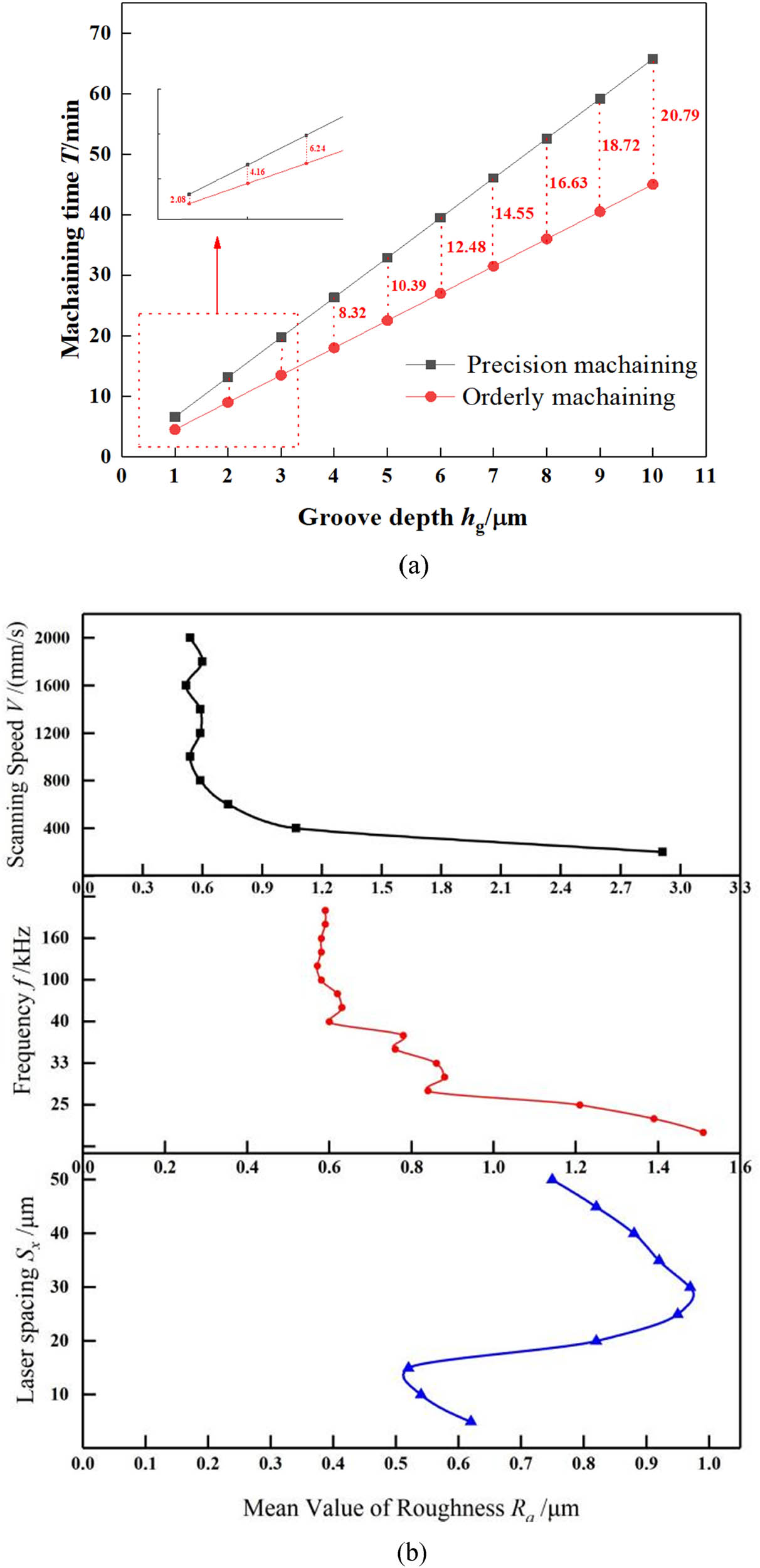

4.3 Processing efficiency

In order to compare the processing efficiency of ordered structure technology and traditional precision machining, a fiber laser commonly used in produkty was used to carry out a comparative experimental study on the processing efficiency of the two processing processes based on the parameter settings shown in Table 4. Through analysis and testing, the grooving depth of the two processes in a single cycle per unit time can be calculated, and then the machining time of the two processing processes corresponding to different target grooving depths can be obtained by fitting. The fitting results are shown in Figure 6(a). It can be seen that the order processing of DGS based on the ordered structure technology has high efficiency and short cycle. Compared with conventional laser precision (the textureless structure method), the machining time of the ordered structure technology was reduced by 31%. Taking the groove depth h g = 5 μm as an example, the time of the ordered structure technology is saved by about 10.39 min compared with the traditional precision machining method.

Processing prediction and outcome analysis

| Groups | Expected groove depth | |

|---|---|---|

| Textureless structure | Ordered texture | |

| (a) Expected groove depth for each group | ||

| 1 | h g-a = 5 μm | h g-A = 5 μm |

| 2 | h g-b = 6 μm | h g-B = 6 μm |

| 3 | h g-c = 8 μm | h g-C = 7 μm |

| Sample | Random selection 1 (μm) | Random selection 2 (μm) | Random selection 3 (μm) | Mean value (μm) | Groove type | Mean square deviation σ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (b) Results and analysis of roughness measurement | ||||||||||||

| A | 0.234 | 0.27 | 0.299 | 0.315 | 0.297 | 0.264 | 0.307 | 0.315 | 0.307 | 0.290 | Textureless | 0.0000006 |

| B | 0.325 | 0.338 | 0.385 | 0.328 | 0.311 | 0.313 | 0.362 | 0.351 | 0.374 | 0.343 | Textureless | 0.0000005 |

| C | 0.430 | 0.410 | 0.435 | 0.413 | 0.437 | 0.477 | 0.417 | 0.402 | 0.404 | 0.425 | Textureless | 0.0000003 |

| D | 1.169 | 1.058 | 1.006 | 1.067 | 1.010 | 1.029 | 0.828 | 0.886 | 0.906 | 0.995 | Ordered | 0.0001227 |

| E | 0.927 | 0.898 | 0.895 | 1.142 | 1.158 | 1.162 | 1.091 | 1.098 | 1.104 | 1.053 | Ordered | 0.0001618 |

| F | 1.093 | 1.129 | 1.090 | 0.910 | 1.061 | 1.179 | 1.016 | 0.985 | 1.033 | 1.055 | Ordered | 0.0000414 |

| Sample | Random selection 1 (μm) | Random selection 2 (μm) | Random selection 3 (μm) | Mean value (μm) | Groove type | Mean square deviation σ | Machining error | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (c) Results and analysis of groove depth measurements | |||||||||||||

| A | 5.186 | 5.083 | 5.266 | 5.041 | 5.316 | 5.221 | 5.234 | 5.146 | 5.058 | 5.17 | Textureless | 0.0000900 | 3.45% |

| B | 6.210 | 6.216 | 6.168 | 6.216 | 6.237 | 6.281 | 6.212 | 6.300 | 6.355 | 6.24 | Textureless | 0.0000100 | 4.06% |

| C | 8.357 | 8.476 | 8.240 | 8.270 | 8.270 | 8.226 | 8.304 | 8.270 | 8.263 | 8.30 | Textureless | 0.0000300 | 3.72% |

| D | 4.807 | 4.950 | 4.953 | 5.099 | 5.011 | 5.011 | 5.120 | 5.183 | 5.154 | 5.03 | Ordered | 0.0002000 | 0.64% |

| E | 6.056 | 6.027 | 6.135 | 5.995 | 6.107 | 5.969 | 6.182 | 6.017 | 6.176 | 6.07 | Ordered | 0.0000400 | 1.23% |

| F | 6.895 | 6.971 | 7.077 | 7.182 | 7.031 | 6.811 | 7.028 | 7.000 | 6.811 | 6.98 | Ordered | 0.0002200 | −0.31% |

Processing efficiency and machining parameters. (a) Comparison of processing cycles of DGSs with ordered and textureless structures. (b) Distribution of groove roughness under different scanning speed V, frequency f, and laser spacing S x .

In order to obtain the ideal range of machining parameters, supplementary experiments have been designed. The effects of laser spacing S x , scanning speed V, and frequency f on the groove bottom roughness were studied separately. As shown in Figure 6(b), when the filling spacing is 5–20 μm, the scanning speed is 1,000–2,000 m·s−1 and the repetition frequency is >100 Hz, the groove bottom roughness performs well. It means, the processing parameters are within the above range, which is conducive to improving the processing quality.

5 Quality inspection specification

A search of the literature and patent information in this field reveals that a standard or specification related to DGS precision machining does not exist. To realize unified planning and standard recognition of the processing quality of DGSs, we considered the key characterization parameters and errors in the processing of DGSs, while at the same time referring to the relevant industrial manufacturing standards [30]. A preliminary method for the quality detection and evaluation of DGS processing was proposed. The groove depth and roughness were randomly detected several times based on the same detection method. When the sampling length l r > 0.8 mm and the number of random tests m ≥ 9, under the premise that the mean roughness R a ≤ 0.8 μm, the mean square deviations of the groove depth and roughness would have to meet the following requirements which is shown in equation (5).

where

The novelty of the proposed quality detection and evaluation method mainly reflected in the following aspects:

The number of detections is specified, which can effectively reduce the influence of single detection error.

The sampling length is calibrated to avoid the influence of insufficient overall characterization caused by excessively small sample length.

The combination of random multi-groove and single groove random multiple times can improve the validity of sample data.

The fluctuation range of roughness and groove depth data is defined by means of mean square deviation, which further improves the reliability of detection data.

Based on this evaluation method and the ultrafast laser processing technology concept proposed in this work, both textureless and ordered textures were selected for detection and analysis. The NI-LG-3120-type picosecond laser processing platform was used to produce three groups (six samples) of seal samples with different depths. The expected groove depths calculated from the single-cycle depth are listed in Table 4(a).

The groove depth and roughness were tested. First, three grooves were randomly selected on the seal ring, and then three positions were randomly selected for each groove. The final test results of the groove depth and roughness consist of nine groups, as provided in Table 4(b) and (c). As indicated in Table 4(b), the processing quality of the textureless structure is relatively ideal, and the maximum average roughness is only 0.425 μm, meeting the requirement of R a ≤ 0.8 μm. The maximum mean square deviations of the groove depth and roughness are 0.0000900 and 0.0000006, respectively, indicating that the proposed processing technology has good stability. The results in Table 4(c) show that, compared with the textureless structure, the roughness of the ordered texture is generally greater (with a maximum roughness of 1.104 μm), and the mean square deviations of the groove depth and roughness are also higher (with maximum values of 0.0002200 and 0.0001227, respectively). This is because, although the regularity of the groove bottom of the ordered structure is good, the existence of texture increases the fluctuation of groove depth and roughness, which affects the detection results.

According to the aforementioned experimental results, the allowable mean square deviations of groove depth and roughness for a textureless structure are suggested as follows:

Further analysis of the results in Table 4(c) indicates that the maximum error between the actual groove depth and the expected groove depth is only 4.06%, demonstrating that the proposed technology can more accurately meet the actual machining requirements.

6 Conclusion

In practice, different parameter combinations correspond to different production and processing efficiencies for DGS precision machining of either the textureless or ordered texture type. Given the requirement for high production efficiency and based on the parameter combination corresponding to the ablation threshold of the material, parameters such as the laser power, scanning speed, and repetition frequency can be adjusted to reduce the processing precision and improve the processing efficiency until the accuracy–efficiency trade-off is optimal. The conclusions are summarized as follows:

For precision machining of DGSs, it is very important to scientifically identify the optimal parameter combination corresponding to the ablation threshold of the material; this is crucial for further exploration of high-efficiency processing technology that satisfies the requirement of precision.

The “cold machining” feature of picosecond ultrafast lasers increases the accuracy of the processed surface, which is suitable for high-efficiency and high-quality precision machining of DGSs with micrometer-level texture groove depth, thereby meeting the production requirements of industrial applications.

Under the premise of ensuring that the laser scanning spacing corresponding to the repetition frequency and scanning speed does not exceed the minimum spot diameter and thus does not cause discontinuous processing, an ordered texture structure with good morphological characteristics and high precision can be realized by reasonably adjusting the laser spacing in the x-direction.

A quality detection and evaluation method based on random depth and roughness mean square deviations at multiple points under the same test method is proposed. The method can be used as a reference for the subsequent development of quality testing schemes for DGS grooving in line with industrial testing standards and efficiency requirements.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 52275192); Lianyungang City “521” Project (Grant number LYG06521202262); Jiangsu Province Graduate Research and Practice Innovation Program (Grant number KYCX23-3453).

-

Funding information: This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 52275192), the Lianyungang City “521” Project (Grant number LYG06521202262), and the Jiangsu Province Graduate Research and Practice Innovation Program (Grant number KYCX23-3453).

-

Author contributions: Yiming He: writing – review and editing, data curation, software, and methodology; Yan Wang: writing – original draft, conceptualization, and supervision; Zhouxin Huang: investigation; Kangjie Kong: resources; Quanzhong Zhao: supervision; Xucheng Jin: validation; Yiqin Wang: resources; and Wei Liu: software.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Kolomoets, A. and V. Dotsenko. Experimental investigation dry gas-dynamic seals used for gas-compressor unit. Procedia Engineering, Vol. 39, 2012, pp. 379–386.10.1016/j.proeng.2012.07.041Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ding, X. and J. Lu. Theoretical analysis and experiment on gas film temperature in a spiral groove dry gas seal under high speed and pressure. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, Vol. 96, 2016, pp. 438–450.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2016.01.045Search in Google Scholar

[3] Shen, W., X. Peng, J. Jiang, and J. Li. Analysis on real effect of supercritical carbon dioxide dry gas seal at high speed. CIESC Journal, Vol. 70, No. 7, 2019, pp. 2645–2659.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wang, Y., W. Liu, and Y. Liu. Current research and developing trends on non-contacting mechanical seals. Hydraulics Pneumatics & Seals, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2011, pp. 29–33.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ding, X., W. Zhang, and S. Yu. Dry gas seal dynamics, Machinery Industry Press, Beijing, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Fu, Y., X. Tang, X. Hua, and Q. Huang. Study on performance test of different types of laser surface texturing seal. Fluid Machinery, Vol. 38, No. 8, 2010, pp. 1–4.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Wang, Y., X. Yu, L. Lu, and Y. He. Current research on slotting technology of non-contact mechanical seal. Hydraulics Pneumatics & Seals, Vol. 36, No. 11, 2016, pp. 1–6.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Feng, X. and X. Peng. Effect of surface roughness on performance of a spiral groove gas seal. Lubrication Engineering, Vol. 173, No. 1, 2016, pp. 20–22.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Song, P., X. Hu, and H. Xu. Effect of real gas on dynamic performance of t-groove dry gas seal. CIESC Journal, Vol. 65, No. 4, 2014, pp. 1344–1352.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Song, P., S. Zhang, and H. Xu. Analysis of performance of spiral groove dry gas seal considered effects of both real gas and slip flow. CIESC Journal, Vol. 67, No. 4, 2016, pp. 1405–1415.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Li, W., P. Song, D. Cao, and Y. Zhao. The influent of roughness of seal faces on the operating performance of gas face seal at slow speed. Lubrication Engineering, Vol. 182, No. 10, 2006, pp. 87–91.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ministry of industry and information technology of the People's Republic of China. JB/T 11289-2012 Specification for dry gas seal, China Machine Press, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Zhang, Y., S. Bai, X. Meng, J. Li, and X. Peng. Analysis of performance of a tapered-t-groove dry gas face seal. Lubrication Engineering, Vol. 36, No. 9, 2011, pp. 19–23.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Shahin, I., M. Gadala, M. Alqaradawi, and O. Brdr. Three dimensional computational study for spiral dry gas seal with constant groove depth and different tapered grooves. Procedia Engineering, Vol. 68, 2013, pp. 205–212.10.1016/j.proeng.2013.12.169Search in Google Scholar

[15] Jiang, J., X. Peng, J. Li, and C. Yuan. A comparative study on the performance of typical types of bionic groove dry gas seal based on bird wing. Journal of Bionic Engineering, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2016, pp. 324–334.10.1016/S1672-6529(16)60305-0Search in Google Scholar

[16] Blasiak, S. and A. V. Zahorulko. A parametric and dynamic analysis of non-contacting gas face seals with modified surfaces. Tribology International, Vol. 94, 2016, pp. 126–137.10.1016/j.triboint.2015.08.014Search in Google Scholar

[17] Ma, C., Y. Duan, B. Yu, J. Sun, and Q. Tu. The comprehensive effect of surface texture and roughness under hydrodynamic and mixed lubrication conditions. Journal of Engineering Tribology, Vol. 231, No. 10, 2017, pp. 1–13.10.1177/1350650117693146Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ren, X., C. Wu, and P. Zhou. Gas sealing performance study of rough surface. Journal of Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 46, No. 16, 2010, pp. 176–181.10.3901/JME.2010.16.176Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ma, C., H. Zhu, and J. Sun. Optimal design model of surface texture with surface roughness considered. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Natural Science Edition), Vol. 39, No. 8, 2011, pp. 14–18, 35.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Liu, D., Y. Liu, and S. Chen. Hydrostatic gas lubrication, Harbin Institute of Technology Press, Harbin, 1990.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Bai, S. and S. Wen. Gas thermal lubrication and sealing, Tsinghua University Press, Beijing, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Wang, Y., J. Sun, Q. Hu, D. Wang, and X. Zheng. Orientation effect of orderly roughness microstructure on spiral groove dry gas seal. Tribology International, Vol. 126, 2018, pp. 97–105.10.1016/j.triboint.2018.05.009Search in Google Scholar

[23] Hu, Q., Y. Wang, R. Dai, J. Sun, and X. Zheng. Performance study of arc-groove dry gas seal based on orderly micro-structure. CIESC Journal, Vol. 70, No. 3, 2019, pp. 1006–1015.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Hu, Q., M. Zhu, Y. Wang, X. Tang, and W. Xu. Performance analysis of fir tree-groove dry gas seal with radial orderly micro-structure. Advanced Engineering Sciences, Vol. 52, No. 1, 2020, pp. 153–160.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Wang, Y., J. Sun, Q. Hu, Y. Zhu, D. Wang, and X. Zheng. Numerical analysis of dry gas seal flow orderliness based on microstructure modeling. Tribology, Vol. 36, No. 6, 2018, pp. 673–683.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of The People's Republic of China. JB/T 11289-2012 Specification for dry gas seal, China Machine Press, Beijing, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Chichkov, B. N., C. Momma, S. Nolte, F. Alvensleben, and A. Tünnermann. Femtosecond, picosecond and nanosecond laser ablation of solids. Applied Physics A, Vol. 63, No. 2, 1996, pp. 109–115.10.1007/BF01567637Search in Google Scholar

[28] Jiang, J. Theoretical and experimental study of the bionic design of grooved surface of a high-speed dry gas seal, Doctoral dissertation. Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Chen, Y. Theoretical and experimental studies of dynamic performance of spiral groove dry gas seals at High Speeds, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, 2018.10.1016/j.triboint.2018.04.005Search in Google Scholar

[30] General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People's Republic of China. GB/T 1301-2009 Geometrical product specifications (GPS)-Surface texture: Profile method-Surface roughness parameters and their values, Standards Press of China, Beijing, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Endpoint carbon content and temperature prediction model in BOF steelmaking based on posterior probability and intra-cluster feature weight online dynamic feature selection

- Thermal conductivity of lunar regolith simulant using a thermal microscope

- Multiobjective optimization of EDM machining parameters of TIB2 ceramic materials using regression and gray relational analysis

- Research on the magnesium reduction process by integrated calcination in vacuum

- Microstructure stability and softening resistance of a novel Cr-Mo-V hot work die steel

- Effect of bonding temperature on tensile behaviors and toughening mechanism of W/(Ti/Ta/Ti) multilayer composites

- Exploring the selective enrichment of vanadium–titanium magnetite concentrate through metallization reduction roasting under the action of additives

- Effect of solid solution rare earth (La, Ce, Y) on the mechanical properties of α-Fe

- Impact of variable thermal conductivity on couple-stress Casson fluid flow through a microchannel with catalytic cubic reactions

- Effects of hydrothermal carbonization process parameters on phase composition and the microstructure of corn stalk hydrochars

- Wide temperature range protection performance of Zr–Ta–B–Si–C ceramic coating under cyclic oxidation and ablation environments

- Influence of laser power on mechanical and microstructural behavior of Nd: YAG laser welding of Incoloy alloy 800

- Aspects of thermal radiation for the second law analysis of magnetized Darcy–Forchheimer movement of Maxwell nanomaterials with Arrhenius energy effects

- Use of artificial neural network for optimization of irreversibility analysis in radiative Cross nanofluid flow past an inclined surface with convective boundary conditions

- The interface structure and mechanical properties of Ti/Al dissimilar metals friction stir lap welding

- Significance of micropores for the removal of hydrogen sulfide from oxygen-free gas streams by activated carbon

- Experimental and mechanistic studies of gradient pore polymer electrolyte fuel cells

- Microstructure and high-temperature oxidation behaviour of AISI 304L stainless steel welds produced by gas tungsten arc welding using the Ar–N2–H2 shielding gas

- Mathematical investigation of Fe3O4–Cu/blood hybrid nanofluid flow in stenotic arteries with magnetic and thermal interactions: Duality and stability analysis

- Influence on hexagonal closed structure and mechanical properties of outer heat treatment cycle and plasma arc transfer Ti54Al23Si8Ni5XNb+Ta coating for Mg alloy by selective laser melting process

- Effect of rare-earth yttrium doping on the microstructure and texture of hot-rolled non-oriented electrical steel

- Study on the rheological behavior and microstructure evolution of isothermal compression of high-chromium cast steel

- Topical Issue on Conference on Materials, Manufacturing Processes and Devices - Part II

- Effects of heat treatment on microstructure and properties of CrVNiAlCu high-entropy alloy

- Enhanced bioactivity and degradation behavior of zinc via micro-arc anodization for biomedical applications

- Study on the parameters optimization and the microstructure of spot welding joints of 304 stainless steel

- Research on rotating magnetic field–assisted HRFSW 6061-T6 thin plate

- Efficient preparation and evaluation of dry gas sealed spiral grooves

- Special Issue on A Deep Dive into Machining and Welding Advancements - Part II

- Microwave hybrid process-based fabrication of super duplex stainless steel joints using nickel and stainless steel filler materials

- Special Issue on Polymer and Composite Materials and Graphene and Novel Nanomaterials - Part II

- Low-temperature corrosion performance of laser cladded WB-Co coatings in acidic environment

- Special Issue for the conference AMEM2025

- Effect of thermal effect on lattice transformation and physical properties of white marble

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Endpoint carbon content and temperature prediction model in BOF steelmaking based on posterior probability and intra-cluster feature weight online dynamic feature selection

- Thermal conductivity of lunar regolith simulant using a thermal microscope

- Multiobjective optimization of EDM machining parameters of TIB2 ceramic materials using regression and gray relational analysis

- Research on the magnesium reduction process by integrated calcination in vacuum

- Microstructure stability and softening resistance of a novel Cr-Mo-V hot work die steel

- Effect of bonding temperature on tensile behaviors and toughening mechanism of W/(Ti/Ta/Ti) multilayer composites

- Exploring the selective enrichment of vanadium–titanium magnetite concentrate through metallization reduction roasting under the action of additives

- Effect of solid solution rare earth (La, Ce, Y) on the mechanical properties of α-Fe

- Impact of variable thermal conductivity on couple-stress Casson fluid flow through a microchannel with catalytic cubic reactions

- Effects of hydrothermal carbonization process parameters on phase composition and the microstructure of corn stalk hydrochars

- Wide temperature range protection performance of Zr–Ta–B–Si–C ceramic coating under cyclic oxidation and ablation environments

- Influence of laser power on mechanical and microstructural behavior of Nd: YAG laser welding of Incoloy alloy 800

- Aspects of thermal radiation for the second law analysis of magnetized Darcy–Forchheimer movement of Maxwell nanomaterials with Arrhenius energy effects

- Use of artificial neural network for optimization of irreversibility analysis in radiative Cross nanofluid flow past an inclined surface with convective boundary conditions

- The interface structure and mechanical properties of Ti/Al dissimilar metals friction stir lap welding

- Significance of micropores for the removal of hydrogen sulfide from oxygen-free gas streams by activated carbon

- Experimental and mechanistic studies of gradient pore polymer electrolyte fuel cells

- Microstructure and high-temperature oxidation behaviour of AISI 304L stainless steel welds produced by gas tungsten arc welding using the Ar–N2–H2 shielding gas

- Mathematical investigation of Fe3O4–Cu/blood hybrid nanofluid flow in stenotic arteries with magnetic and thermal interactions: Duality and stability analysis

- Influence on hexagonal closed structure and mechanical properties of outer heat treatment cycle and plasma arc transfer Ti54Al23Si8Ni5XNb+Ta coating for Mg alloy by selective laser melting process

- Effect of rare-earth yttrium doping on the microstructure and texture of hot-rolled non-oriented electrical steel

- Study on the rheological behavior and microstructure evolution of isothermal compression of high-chromium cast steel

- Topical Issue on Conference on Materials, Manufacturing Processes and Devices - Part II

- Effects of heat treatment on microstructure and properties of CrVNiAlCu high-entropy alloy

- Enhanced bioactivity and degradation behavior of zinc via micro-arc anodization for biomedical applications

- Study on the parameters optimization and the microstructure of spot welding joints of 304 stainless steel

- Research on rotating magnetic field–assisted HRFSW 6061-T6 thin plate

- Efficient preparation and evaluation of dry gas sealed spiral grooves

- Special Issue on A Deep Dive into Machining and Welding Advancements - Part II

- Microwave hybrid process-based fabrication of super duplex stainless steel joints using nickel and stainless steel filler materials

- Special Issue on Polymer and Composite Materials and Graphene and Novel Nanomaterials - Part II

- Low-temperature corrosion performance of laser cladded WB-Co coatings in acidic environment

- Special Issue for the conference AMEM2025

- Effect of thermal effect on lattice transformation and physical properties of white marble