Abstract

Graphene oxide hydrosol was added dropwise to the surface of chitosan (CS) to successfully obtain graphene oxide/chitosan composite (GC). The composite material was characterized by scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction. The prepared adsorbent was used to simulate the static adsorption of copper, lead, and cadmium ions from 100 mL of 50 mg/L simulated wastewater samples. When the pH of the simulated wastewater is 6, initial dosage is 70 mg, adsorption time is 90 min, and temperature is 20°C; the adsorption capacities for copper, lead, and cadmium are 60.7, 48.7, and 32.3 mg/g, respectively. The adsorption and desorption cycle experiments show that the adsorption capacity of GC for copper ions can reach 86% of the initial adsorption capacity after ten cycles. The adsorption of lead ions on the composite conforms to the Freundlich adsorption isotherm model.

1 Introduction

In recent years, toxic heavy metal ions have widely been introduced into the aquatic environment due to the dumping of e-waste, the burning of fossil fuels, municipal waste treatment, mining and smelting, the application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and sewage [1]. Lead poisoning is generally chronic, causing some changes in bones, leading to red blood cell disorders and therefore anemia and cancer. Cadmium enters the aquatic ecosystem through erosion of soil and bedrock, precipitation of atmospheric pollutants from industrial units, wastewater from polluted areas, and sludge and fertilizers used in agriculture. Most importantly, they easily accumulate in living organisms and cause a variety of diseases and death. Because these ions have high mobility and spread rapidly over large areas, removing them from the environment is one of the challenges facing science today [2,3,4,5,6]. At present, industrial methods for treating heavy metal wastewater mainly include chemical treatment methods such as chemical precipitation method [7] and electrochemical method [8,9,10], physical treatment methods such as ion exchange method [11,12] and adsorption method [13], and biological treatment methods such as plant treatment [14,15,16] and microbial treatment [17,18]. Among them, the adsorption method is considered to be an effective and economical method, and the design and operation of the adsorption process are also flexible, and some composite adsorbents are low in cost, and the treatment effect is observable [19,20].

Graphene oxide (GO) is one of the most widely studied adsorption materials in the past decade. It offers the advantages of large specific surface area, fast adsorption speed, and low preparation cost. Its structure contains a large number of oxygen-containing functional groups (epoxy, hydroxyl, carboxyl, etc.) that can react with heavy metal ions to form metal ion chelate compounds. Its unique structure with larger voids effectively shortens the diffusion path of heavy metal ions and thus has excellent ion trapping capabilities [21,22,23,24,25]. Chitosan (CS) is a chitin from seafood processing waste and is manufactured by the deacetylation of chitin. It is an environmentally friendly biopolysaccharide with an annual output of more than 10 billion tons. It has good biodegradability, biofunctionality, biocompatibility, and good safety. Its molecule contains a large number of amino groups and hydroxyl groups, which can provide dynamic adsorption sites and can coordinate with heavy metal ions, so it can be used as a high-performance composite adsorbent for various heavy metal ions [26,27,28].

So far, some published reports on graphene oxide/chitosan composites (GC) for wastewater adsorption treatment show that GC and GO composites have high stability and good mechanical properties [29,30,31,32,33]. It has excellent adsorption effect on toxic heavy metals such as Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+. At present, most studies are restricted to the study of the adsorption performance of a heavy metal ion, and there are relatively few reports on the treatment of multiple heavy metal ions in wastewater. In this study, GO and CS were added together to prepare composite adsorption material GC. The adsorption mechanism was investigated by means of scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and other characterization methods. The adsorption characteristics of GC for copper, lead, and cadmium and the adsorption isotherm model of the adsorption process were discussed. It can be seen that GC material reduces GO agglomeration, increases specific surface area, and effectively increases active adsorption sites, resulting in the material having good adsorption performance. When the contaminated water contains copper, lead and cadmium ions at the same time, the use of this material allows the adsorption process to proceed better.

2 Experiment

2.1 Materials

Graphite powder (analytical grade), CS (Shanghai LanJi Biological Company), 30% H2O2, NaNO3, H2SO4, HCl, NaOH, and K2MnO4 are analytical purification reagents.

2.2 Preparation of composite adsorbent

According to the Hummers method, the graphite oxide solids were prepared in three stages of low temperature, medium temperature, and high temperature, ground into powder, and dried for use [34]. The prepared graphite oxide powder accurately weighing 0.25 g was added to 250 mL of distilled water, and after ultrasonic dispersion for 300 min at 300 W, 1.0 mg/mL of GO hydrosol was obtained.

The prepared 1.0 mg/mL of the GO hydrosol was added dropwise to 0.5 g of CS, and the mixture was adjusted to a paste and fully wetted and dried. The above dropping process was repeated ten times, the coating thickness of GO on CS was increased, and drying was carried out to obtain a dark brown GC adsorbent which was ground, weighed, and dried.

2.3 Characterization

The structural characterization of all samples was performed using SEM EVO MA 25/LS25 tungsten wire scanning electron microscope for morphology analysis. XRD (LabxXRD-6100 type) was carried out under the conditions of a Cu target as a radiation source, a test voltage and current of 40 kV and 40 mA, respectively, and a scan rate of 5°/min.

2.4 Static adsorption experiment

A certain concentration of Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ standard mixture was prepared as simulated wastewater sample, and the Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ concentrations were determined to be 50 mg/L. At a certain temperature, separate standard volume mixtures of different volumes were placed in a 250 mL shake flask, pH of the standard mixture was adjusted with HCl solution and NaOH solution, and then quantitative GC was added as a composite adsorbent and shaken with a constant temperature oscillator. At different times, after centrifugation, the supernatant in the mixture was taken to measure the concentration of lead, cadmium, and copper ions, and the adsorption capacity of the composite adsorbent was calculated.

In this experiment, the general calculation formula for the adsorption capacity of the composite adsorbent for the metal ion solution is as follows:

where qe is the adsorption capacity after adsorption equilibrium (mg/g), c0 is the ion concentration of simulated wastewater sample before adsorption (mg/L), ce is the ion concentration of simulated wastewater sample after adsorption (mg/L), W is the dosage of the composite adsorbent (g), and V is the volume of simulated wastewater samples (L).

In this experiment, the calculation formula for the adsorption rate of metal ions in simulated wastewater samples by composite materials as adsorbents is as follows:

where R is the adsorption rate (%).

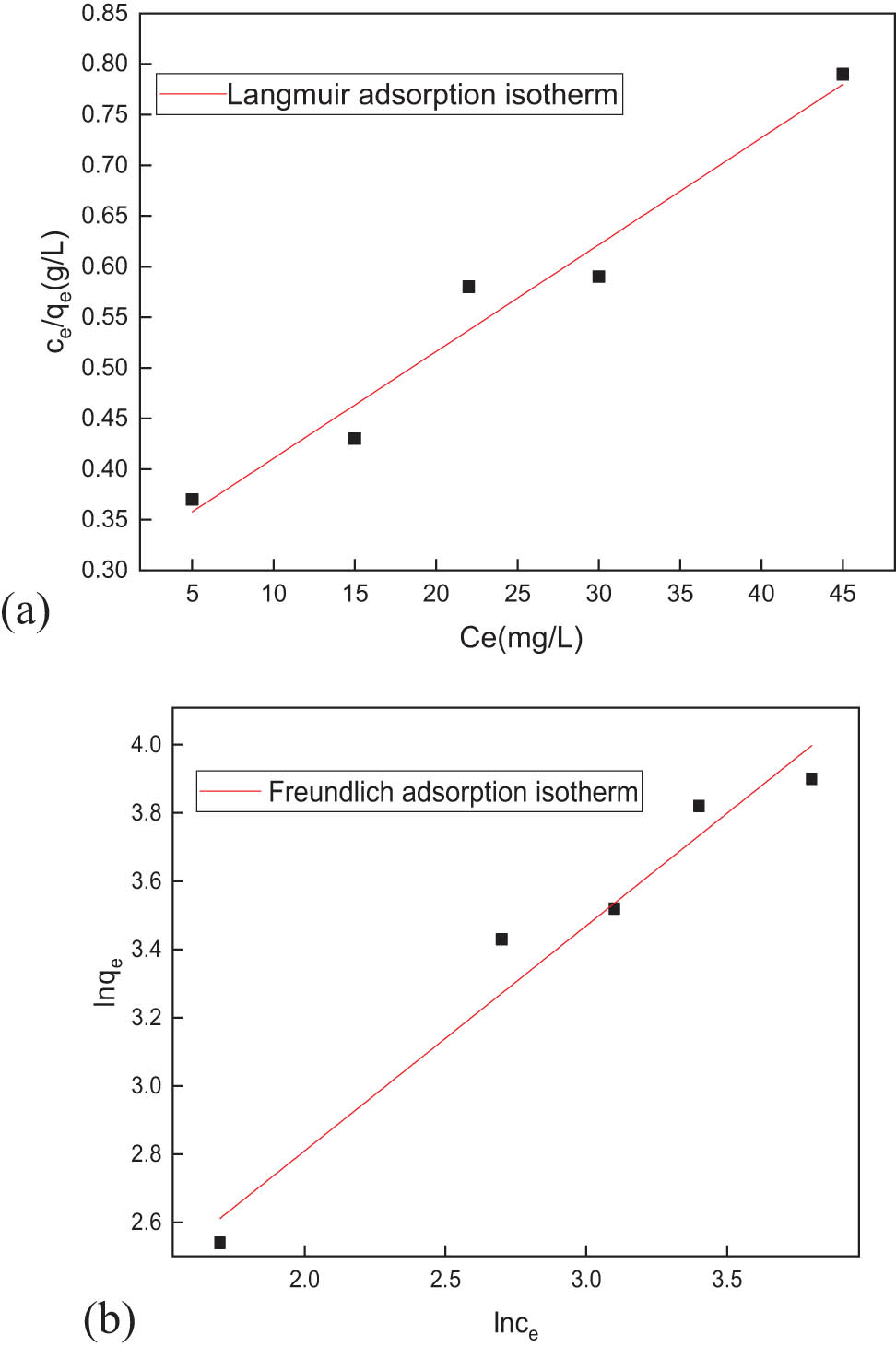

2.5 Adsorption isotherm fitting experiment

The adsorption isotherm of lead ions is taken as an example. Initial concentrations of 50 mL Pb2+ solution are 20, 50, 60, 80, and 100 mg/L, respectively. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 6, and 50 mg of GC adsorbent was added, and the reaction was carried out for 90 min at ambient temperature. After the reaction, the mixture was separated, the concentration of lead ions in supernatant is measured, and the adsorption capacity of the composite adsorbent was calculated. The obtained data are fitted by Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherm models [35,36,37].

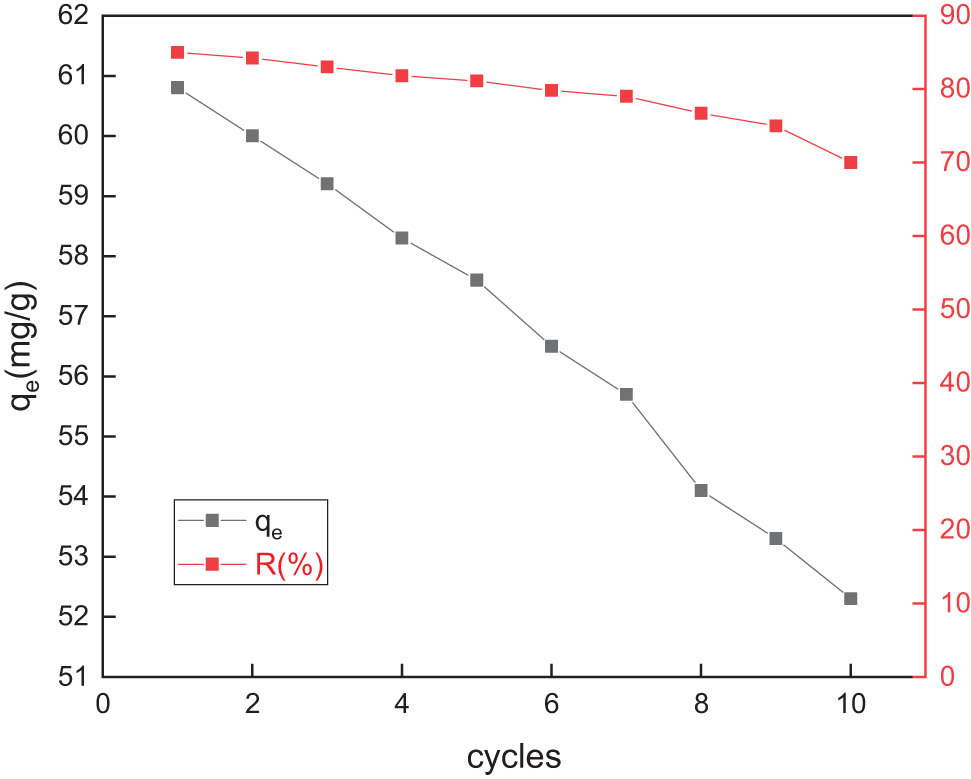

2.6 Adsorption–desorption cycle experiment

In order to further research the adsorption and reuse performance of the prepared GC materials, adsorption–desorption cycle experiments were performed taking adsorption of copper ions as an example. In a 250-mL shake flask, 100 mL of 50 mg/L copper ion solution was taken, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 6, and 70 mg of the adsorbent was added to the solution. The mixture was centrifuged at ambient temperature, rotated at 150 rpm and shaken for 90 min, and the supernatant was measured. The concentration of copper ions was calculated, and the adsorption capacity and adsorption rate were calculated. Then, the adsorbed saturated GC material was washed with distilled water and placed in a clean shaking flask, to which an HCl solution of pH 1 was added. The mixture was shaken under the above-mentioned shaking conditions, and the fully desorbed GC material was washed and dried. To determine the reusability of the GC material, the adsorption experiments were repeated ten times according to the above procedure. The adsorption capacity and the adsorption rate of the composite material for Cu2+ were obtained.

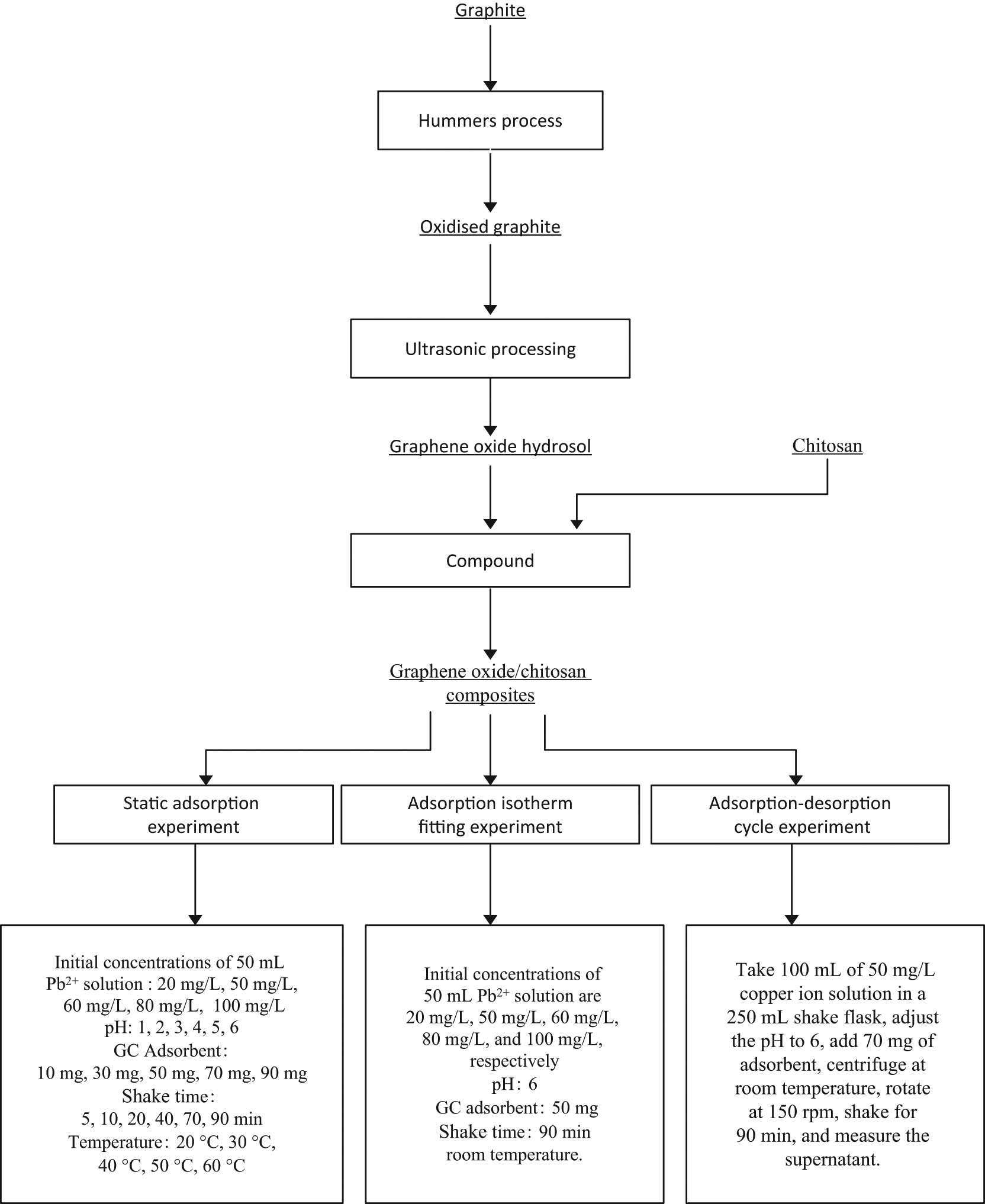

The experimental ideas and experimental conditions of this study are presented in Scheme 1.

Experimental ideas and experimental conditions of this study.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Material characterization results and analysis

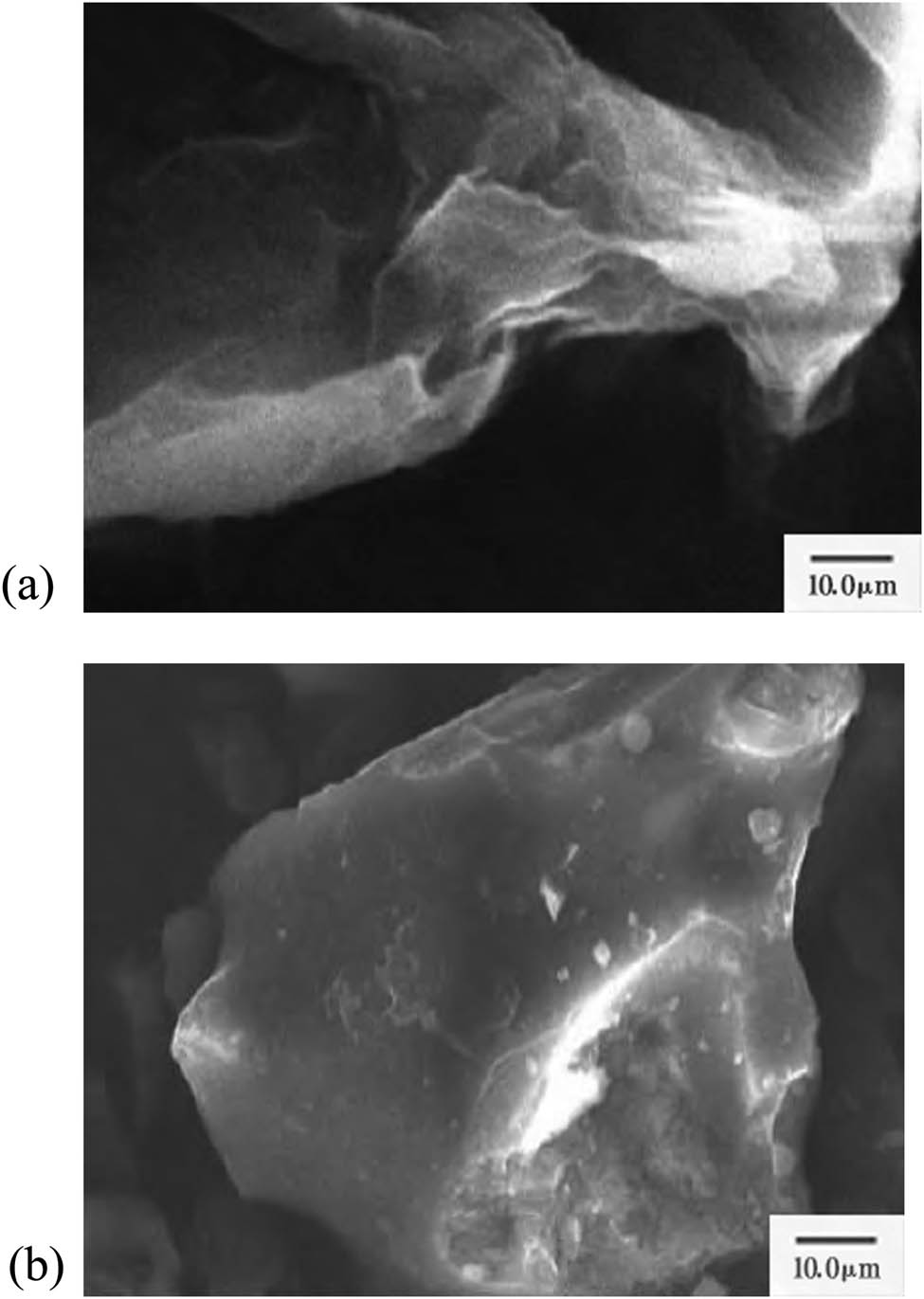

As can be seen from Figure 1a, GO after sonication exists in the form of a single-layer sheet structure, and wrinkles are formed on the surface due to folding and curling between the graphite sheets. In Figure 1b it can be clearly seen that the inside of the sheet-like structure is more evenly dispersed with some irregular particles. Analysis shows that CS is uniformly loaded into the interior of GO, and CS does not undergo significant agglomeration. GO loaded with CS has a large load dispersibility, which increases the specific surface area of GC, thereby increasing the reaction rate of the reactive functional groups on the composite with the copper, lead, and cadmium ions in the simulated wastewater sample, which is beneficial to improving the adsorption performance of the material.

Scanning electron micrographs of (a) GO and (b) GC.

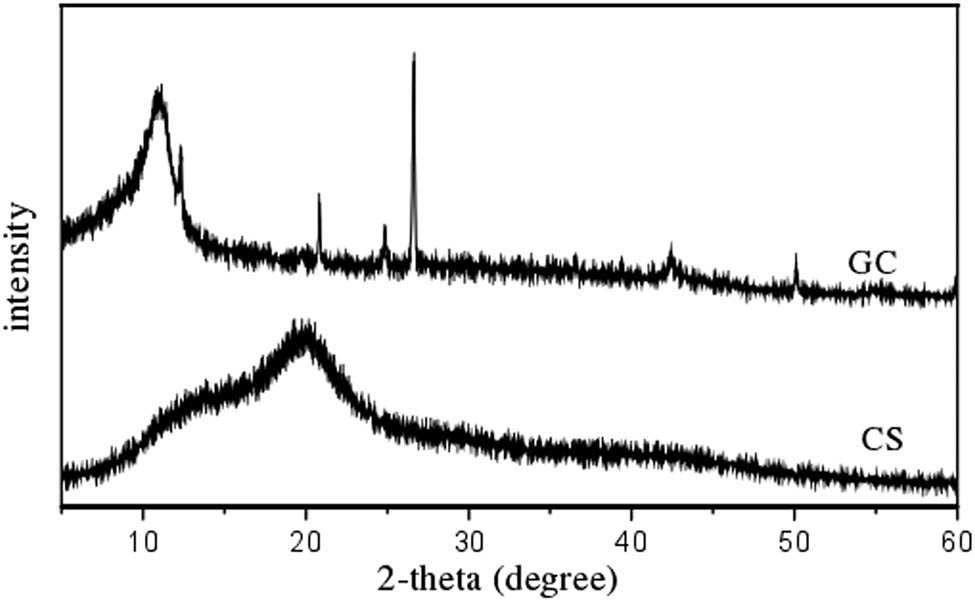

It can be seen from Figure 2 that GC exhibits a characteristic peak of GO at 2θ = 10.8° and a weak characteristic peak of CS at 2θ = 20.3°. From the comparison of the diffraction angles of the two materials, it is obvious that the diffraction angle of GC is smaller than that of CS, which indicates that the GC is more crystalline compared to CS, thereby improving the adsorption performance of GC.

XRD patterns of CS and GC.

3.2 BET aperture analysis

As can be seen from Table 1, the GC material has an average pore diameter of 10.28 nm. It can be seen that the surface of the composite material has a relatively uniform mesoporous structure. Therefore, in the adsorption process, some physical adsorption effects are inevitable, and the column filling rate in the adsorption process will increase with the increase in the lead, cadmium, and copper ion concentration. This greatly helps in improving the physical adsorption performance of the composite adsorbent.

BET aperture analysis results

| Report item | Result value |

|---|---|

| Single point total pore adsorption average pore diameter | 10.28 nm |

3.3 Static adsorption of simulated wastewater samples by GCs

3.3.1 Effect of pH on the adsorption performance of GC in simulated wastewater samples

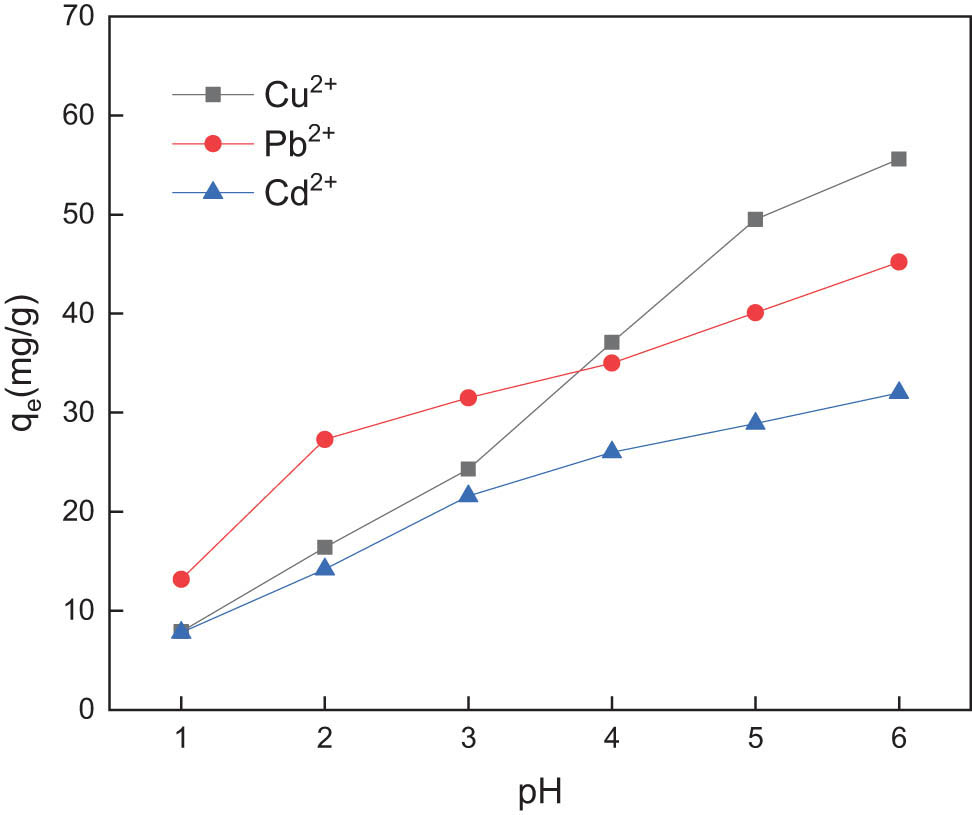

The pH of quantitatively mixed standard simulated wastewater samples was 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively, so that the adsorption equilibrium was fully achieved, and adsorption capacity was calculated. Figure 3 shows the effect of pH on the adsorption of Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ on GC in simulated wastewater samples.

Effect of pH on the adsorption of Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ by GC.

The pH of the simulated wastewater affects the active adsorption sites on the molecular structure of the composite and the presence of metal ions in the wastewater. As shown in Figure 3, when the pH is less than 2, the adsorption capacity of the GC complex for copper, lead, and cadmium ions is relatively low, but as the pH value increases, the adsorption capacity also increases. When the pH is less than 3, the adsorption capacity of the composite adsorbent for lead is higher than that for copper and cadmium, which indicates that the active adsorption sites on the GC are more likely to bind to lead ions at a lower pH of the solution. During the process of improving pH from 1 to 6, there was no sediment in the simulated wastewater. The copper, lead, and cadmium ions in water samples only chelated with the complex, indicating that there was no further loss of copper, lead, and cadmium ions. Among the different pH values selected by the experiment, the optimal adsorption pH for the copper, lead, and cadmium ions in the simulated wastewater samples was 6.

3.3.2 Effect of dosage on the adsorption performance of GC in simulated wastewater samples

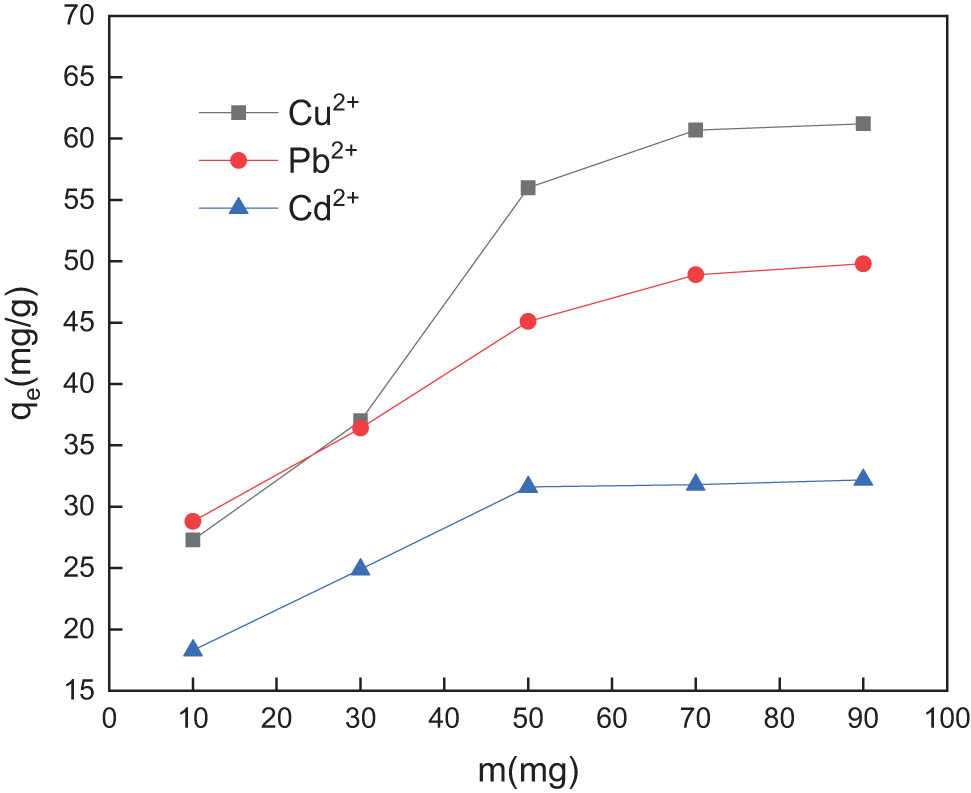

GC of 10, 30, 50, 70, 90 mg were added to the quantitatively mixed standard simulated wastewater samples as adsorbents. The adsorption capacity was calculated after the adsorption was completed. The effect of dosage on the adsorption of Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ on GC in simulated wastewater is shown in Figure 4.

Effect of dosage on the adsorption of Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ by GC.

As can be seen from Figure 4, the adsorption capacity of GC for copper, lead, and cadmium ions generally increases with increasing dosage. When the dosage is less than 70 mg, the adsorption capacity of the composite for copper and lead increases linearly, but when the dosage is more than 70 mg, the adsorption capacity for copper and cadmium remains basically unchanged; when the dosage is more than 50 mg, the adsorption capacity for cadmium does not increase significantly. In order to ensure that the GC has high adsorption capacity for copper, lead, and cadmium ions and reduces cost, the optimum amount of GC is 70 mg. With the increase in the dosage, the active adsorption sites the GC complex provides increase, the binding probability of the copper–lead–cadmium ions to the functional sites increases, and the adsorption capacity increases rapidly. When the dosage continues to increase, the concentration of copper, lead, and cadmium ions in the simulated wastewater sample decreases as the adsorption process progresses, resulting in a decrease in the binding rate. An excessive addition of the composite causes it to agglomerate in the water sample, and the specific surface area is reduced. Hence, it becomes difficult to increase the adsorption capacity.

3.3.3 Effect of adsorption time on the adsorption performance of GC in simulated wastewater samples

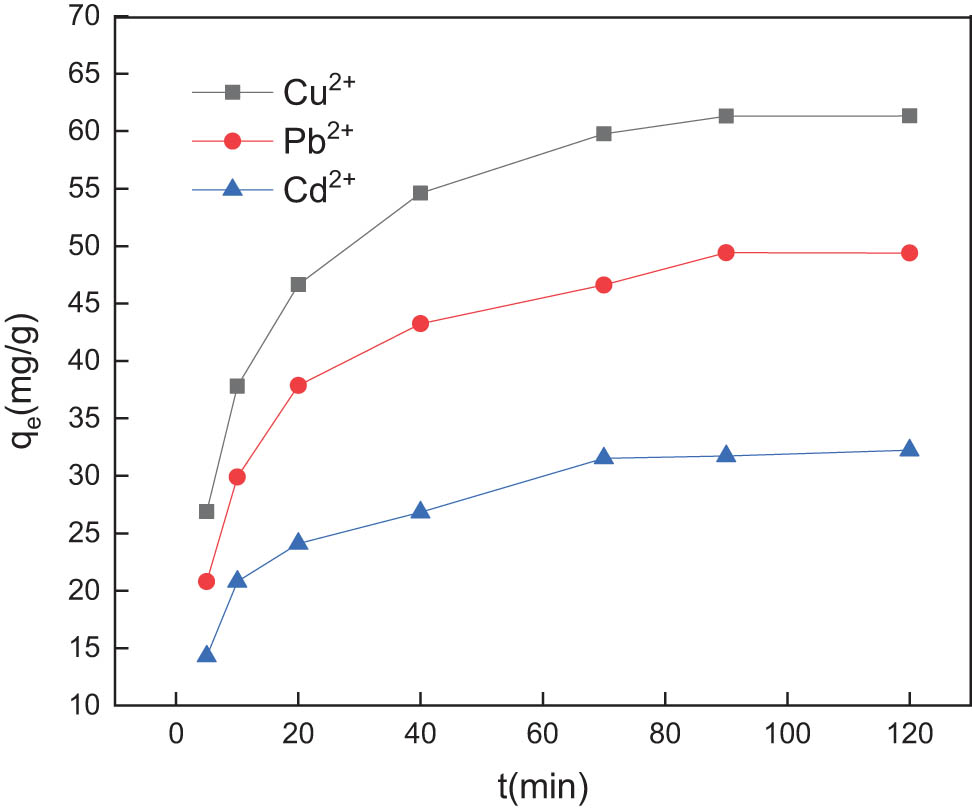

One hundred milliliters of 50 mg/L simulated wastewater sample were taken, the pH of the sample was adjusted to 6, and 70 mg of the prepared composite material was added as adsorbent. The mixture was oscillated 5, 10, 20, 40, 70 min, respectively, at ambient temperature and 150 rpm. After centrifugal separation at 90 and 120 min, the concentrations of Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ in the supernatant were measured. The adsorption capacity of the composite material was calculated based on the changes in ion concentration before and after adsorption for different adsorption times, and the results are shown in Figure 5.

Effect of adsorption time on the adsorption of Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ by GC.

It is known from Figure 5 that in the initial adsorption stage of 0–20 min, the concentration of copper, lead, and cadmium ions is relatively large, and a large number of active sites on the adsorbent can chelate copper, lead, and cadmium ions. Therefore, the adsorbent is under a particularly strong adsorption capacity for copper, lead, and cadmium ions. However, after 20 min, the adsorption capacity increased slowly with the increase in adsorption time. After 90 min, the adsorption equilibrium was attained, and the adsorption capacity did not increase significantly. This is because the active sites on the adsorbent are reduced and the concentration of copper, lead, and cadmium ions in the water sample is lowered, resulting in a reduced possibility of chelation. In addition, the proton H+ in the reactive functional groups in the GC complex amino group is released into the solution. In the middle, the pH of the water sample is reduced, and the electronegativity of the solution is weakened, which hinders the adsorption of copper, lead, and cadmium ions by the adsorbent and increases the adsorption time to reach equilibrium. Therefore, optimal adsorption time for GC to adsorb copper, lead, and cadmium is 90 min.

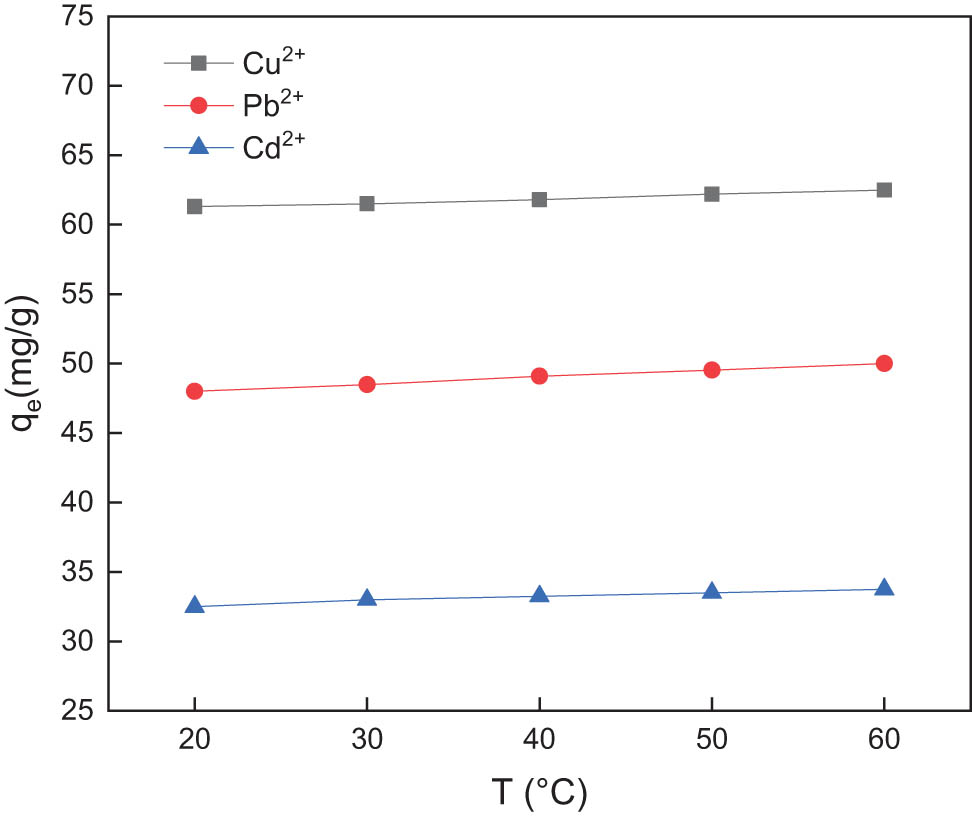

3.3.4 Effect of adsorption temperature on the adsorption performance of GC in simulated wastewater samples

GC were used to simulate the adsorption process of wastewater samples at temperatures of 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60°C. The adsorption capacity of the composites was calculated after the adsorption was completed. The experimental results are presented in Figure 6. Analysis shows that the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent for lead, cadmium, and copper ions increases with the increase in the adsorption temperature, but the effect is not noticeable. Considering consumption reduction in experiments and industrial production, the adsorption experiments can be performed at ambient temperature.

Effect of adsorption temperature on the adsorption of Cu2+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ by GC.

3.4 Data analysis of adsorption isotherm fitting experiment

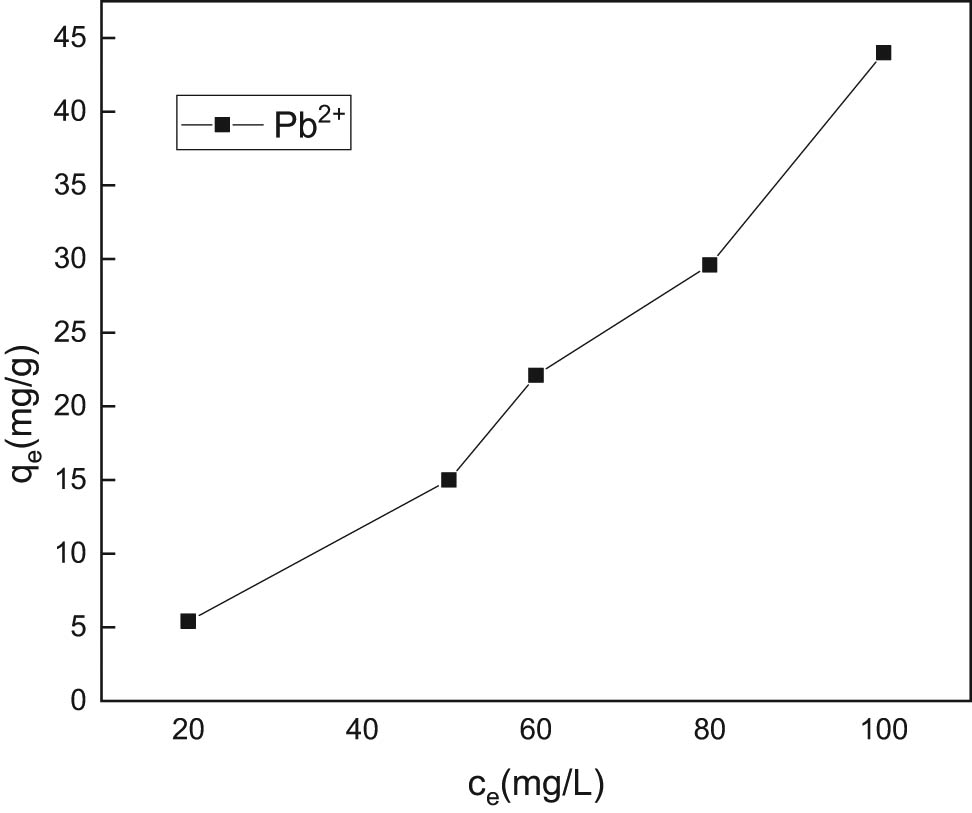

The effect of initial concentration of lead ions in the solution on the adsorption capacity of GC adsorbent is shown in Figure 7.

Effect of initial concentration of lead ion solution on the adsorption performance of GC adsorbent.

It can be seen from Figure 7 that when the initial concentration of lead ions is 20 mg/L or less, since the concentration of lead ions is relatively low, the effective active sites on GC adsorbent at this stage are not fully utilized. When the concentration changes from 20 to 100 mg/L, the utilization rate of the effective active sites on the GC adsorbent gradually increased and the adsorption capacity of the composite adsorbent for lead ions also gradually increased [38,39].

In order to further study GC, based on the above experimental data, Langmuir and Freundlich simulation equations were fitted to the process of adsorption of lead ions on GC, and kinetics of the adsorption of lead ions on the composite adsorbent was further studied. The results are shown in Figure 8.

(a) Langmuir adsorption isotherm and (b) Freundlich adsorption isotherm.

According to Figure 8, the fitting correlation RL = 0.95 of the Langmuir model is lower than the fitting correlation RF = 0.96 of the Freundlich model. This indicates that the adsorption process is more consistent with the Freundlich model. Analysis of Figure 8 shows that the heterogeneity constant of the Freundlich model is more than 1, indicating that the ion concentration on the surface of the adsorbent is increased, the critical energy of adsorption is increased, and the attraction between metal ions is enhanced, which can further increase layer adsorption capacity.

Combined with the applicable characteristics of the Freundlich adsorption model, it is concluded that as the concentration of lead ions in the sample increases, the surface of the adsorbent becomes a heterogeneous surface, which in turn achieves multilayer adsorption effect of the adsorbent and causes the surface of the adsorbent to strongly interact with lead ions; on the other hand, reason for improving adsorption capacity of adsorbent for lead ions is that lead ions are filled into the pores and cracks on the surface of the adsorbent, and efficiency of combining active sites on the surface of the adsorbent with lead ions increases.

Based on the above analysis, the Langmuir and Freundlich empirical models were compared to the results of fitting lead ions to GC. The composites are known to be suitable for medium- and high-concentration adsorption. In the case where the other conditions described above are unchanged, the concentration of simulated wastewater should be appropriately increased. In the process of adsorption of lead ions with respect to the lead ion concentration, the adsorption rate of lead ions remained basically stable, while the adsorption capacity showed a linearly increasing trend.

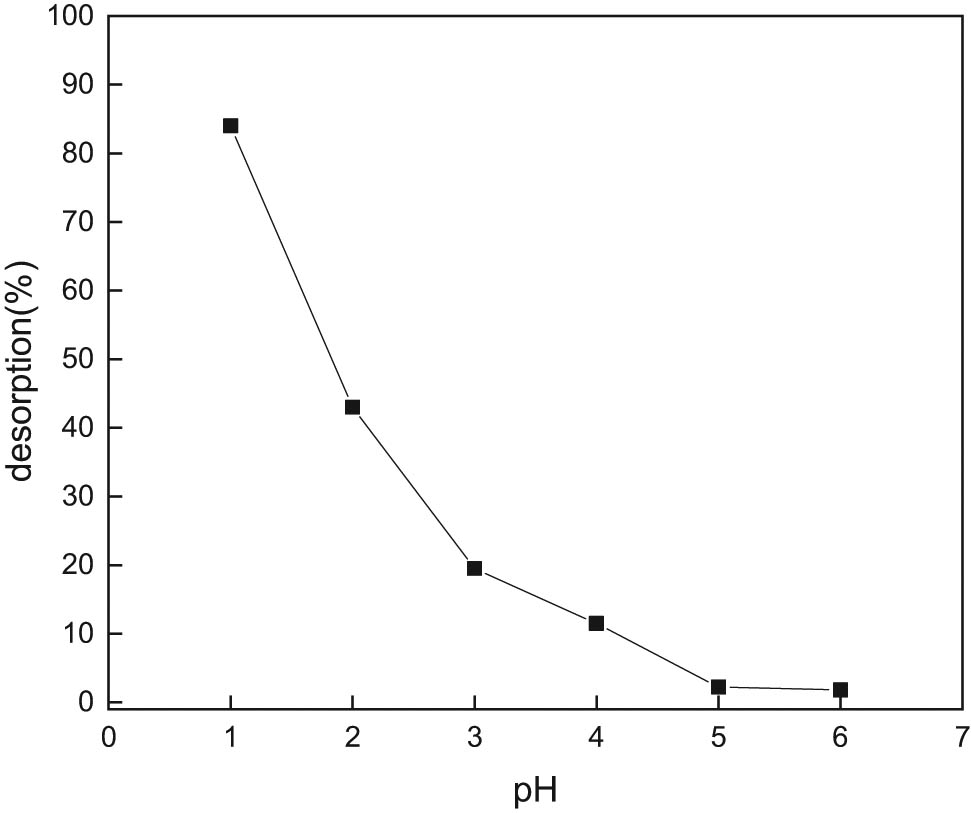

3.5 Adsorption analysis experiment results

The analytical results of adsorption of copper ions at different pH are illustrated in Figure 9. When the pH is 1, more than 82% of copper ions on GC material adsorbed with copper ions are desorbed. As pH increases, desorption rate decreases significantly. The reason for that is proton hydrogen ions in the solution compete with GC adsorbing copper ions for active sites. When pH is less, the copper ions bound on the GC material are easily replaced by proton hydrogen ions in the solution.

Desorption rate of Cu2+ in hydrochloric acid solution at different pH.

It can be seen from Figure 10 that after ten adsorption–desorption cycles, the copper adsorption capacity of the GC material can reach 86% or more of the initial adsorption capacity. It can be seen that GC materials can be reused to adsorb heavy metal ions.

Changes in adsorption capacity and adsorption rate of Cu2+ by adsorption and desorption of GC for ten times.

4 Conclusions

The characterization results of SEM, XRD, and the like show that the GC adsorbent has been successfully synthesized. The pore size analysis showed that the single point total pore adsorption average pore diameter was 10.28 nm, which is characteristic of a mesoporous material, and the adsorption process exhibited physical adsorption.

When the pH is 6, the initial dosage is 70 mg, and the adsorption reaction time is 90 min, at ambient temperature, after GC adsorption in simulated wastewater samples, the maximum adsorption capacity for copper, lead, and cadmium can reach 60.7, 48.7, and 32.3 mg/g, respectively. The adsorption isotherm fitting experiment finds that the adsorption process of lead ions by GC is more consistent with the Freundlich model. The reutilization performance of GC was determined by adsorption analysis experiments. The experimental results have shown that hydrochloric acid is an effective solution for desorption. After using GC for ten adsorptions, the copper ion adsorption capacity can still reach 86% of the initial adsorption capacity, which shows that in addition to the advantages of low cost and high adsorption capacity, GC also have good cycle performance.

GC not only overcomes the disadvantages of graphene and CS, but also makes full use of the advantages of large adsorption capacity of graphene material and excellent chelation ability of CS, and realizes the complementary advantages of the two materials. The GC adsorbent obtained through a simple synthesis process can achieve better results, which provides another new idea to the industry for developing simple, economical, and rapid treatment of sewage containing lead, cadmium, and copper ions.

References

[1] Dashtian K, Zare-Dorabei R. An easily organic–inorganic hybrid optical sensor based on dithizone impregnation on mesoporous SBA-15 for simultaneous detection and removal of Pb2+ ions from water samples: response-surface methodology. Appl Organomet Chem. 2017;12(31):1–14.10.1002/aoc.3842Search in Google Scholar

[2] Mahar FK, He L, Wei K, Mehdi M, Zhu M, Gu J, et al. Rapid adsorption of lead ions using porous carbon nanofibers. Chemosphere. 2019;225:360–7.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.131Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Arulkumar A, Nigariga P, Paramasivam S, Rajaram R. Heavy metals accumulation in edible marine algae collected from Thondi coast of Palk Bay, Southeastern India. Chemosphere. 2019;221:856–62.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Soraya P, Carmen R, Inmaculada F, Dailos JGÁ, Verónica G-W, Consuelo M, et al. Toxic metals (Al, Cd, Pb and Hg) in the most consumed edible seaweeds in Europe. Chemosphere. 2019;218:879–84.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.165Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Saghanejhad Tehrani M, Zare-Dorabei R. Highly efficient simultaneous ultrasonic-assisted adsorption of Methylene Blue and Rhodamine B onto Metal Organic Framework MIL-68(Al): central composite design optimization. RSC Adv. 2016;6(33):27416–25.10.1039/C5RA28052DSearch in Google Scholar

[6] Keramat A, Zare-Dorabei R. Ultrasound-assisted dispersive magnetic solid phase extraction for preconcentration and determination of trace amount of Hg(II) ions from food samples and aqueous solution by magnetic graphene oxide (Fe3O4@GO/2-PTSC): central composite design optimiza. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;38:421–9.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.03.039Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Chen Q, Yao Y, Li X, Lu J, Zhou J, Huang Z. Comparison of heavy metal removals from aqueous solutions by chemical precipitation and characteristics of precipitates. J Water Proc Eng. 2018;26:289–300.10.1016/j.jwpe.2018.11.003Search in Google Scholar

[8] Jasiński A, Guziński M, Lisak G, Bobacka J, Bocheńska M. Solid-contact lead(II) ion-selective electrodes for potentiometric determination of lead(II) in presence of high concentrations of Na(I), Cu2+, Cd2+, Zn(II), Ca(II) and Mg(II). Sens Actuators B. 2015;218:25–30.10.1016/j.snb.2015.04.089Search in Google Scholar

[9] Tran TK, Chiu KF, Lin CY, Leu HJ. Electrochemical treatment of wastewater: selectivity of the heavy metals removal process. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42(45):27741–8.10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.05.156Search in Google Scholar

[10] Vajedi F, Dehghani H. The characterization of TiO2-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites and their performance in electrochemical determination for removing heavy metals ions of cadmium(II), lead(II) and copper(II). Mater Sci Eng B. 2019;243:189–98.10.1016/j.mseb.2019.04.009Search in Google Scholar

[11] Nekouei RK, Pahlevani F, Assefi M, Maroufi S, Sahajwalla V. Selective isolation of heavy metals from spent electronic waste solution by macroporous ion-exchange resins. J Hazard Mater. 2019;371:389–96.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.03.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Ma A, Abushaikha A, Allen SJ, Mckay G. Ion exchange homogeneous surface diffusion modelling by binary site resin for the removal of nickel ions from wastewater in fixed beds. Chem Eng J. 2019;358:1–10.10.1016/j.cej.2018.09.135Search in Google Scholar

[13] Al-Senani GM, Al-Fawzan FF. Adsorption study of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution by nanoparticle of wild herbs. Egyptian J Aquatic Res. 2018;44:187–94.10.1016/j.ejar.2018.07.006Search in Google Scholar

[14] Verma S, Kuila A. Bioremediation of heavy metals by microbial process. Environ Technol Innov. 2019;14:100369.10.1016/j.eti.2019.100369Search in Google Scholar

[15] Rezania S, Taib SM, Md Din MF, Dahalan FA, Kamyab H. Comprehensive review on phytotechnology: heavy metals removal by diverse aquatic plants species from wastewater. J Hazard Mater. 2016;318:587–99.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.07.053Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Xin J, Tang J, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Tian R. Pre-aeration of the rhizosphere offers potential for phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated wetlands. J Hazard Mater. 2019;374:437–46.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.04.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Jacob JM, Karthik C, Saratale RG, Kumar SS, Prabakar D, Kadirvelu K, et al. Biological approaches to tackle heavy metal pollution: a survey of literature. J Environ Manage. 2018;217:56–70.10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.03.077Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Cui Z, Zhang X, Yang H, Sun L. Bioremediation of heavy metal pollution utilizing composite microbial agent of Mucor circinelloides, Actinomucor sp. and Mortierella sp. J Environ Chem Eng. 2017;5(4):3616–21.10.1016/j.jece.2017.07.021Search in Google Scholar

[19] Kyzas GZ, Bomis G, Kosheleva RI, Efthimiadou EK, Favvas EP, Kostoglou M, et al. Nanobubbles effect on heavy metal ions adsorption by activated carbon. Chem Eng J. 2019;356:91–7.10.1016/j.cej.2018.09.019Search in Google Scholar

[20] Hong M, Yu L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Chen Z, Dong L, et al. Heavy metal adsorption with zeolites: the role of hierarchical pore architecture. Chem Eng J. 2019;359:363–72.10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.087Search in Google Scholar

[21] Peng W, Li H, Liu Y, Song S. A review on heavy metal ions adsorption from water by graphene oxide and its composites. J Mol Liq. 2017;230:496–504.10.1016/j.molliq.2017.01.064Search in Google Scholar

[22] Qian H. Preparation and application of graphene oxide/chitosan composites. Shandong, China: Shandong University; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Lim J, Mujawar M, Abdullah E, Nizamuddin S, Khalid M, Inamuddin. Recent trends in the synthesis of graphene and graphene oxide based nanomaterials for removal of heavy metals – a review. J Ind Eng Chem. 2018;66:29–44.10.1016/j.jiec.2018.05.028Search in Google Scholar

[24] Hao S-M, Qu J, Yang J, Gui C-X, Wang Q-Q, Li Q-J, et al. K2Mn4O8/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for excellent lithium storage and adsorption of lead ions. Chemistry. 2016;22(10):3397–404.10.1002/chem.201504785Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Vakili M, Deng S, Cagnetta G, Wang W, Meng P, Liu D, et al. Regeneration of chitosan-based adsorbents used in heavy metal adsorption: a review. Sep Purif Technol. 2019;224:373–87.10.1016/j.seppur.2019.05.040Search in Google Scholar

[26] Jiang C, Wang X, Wang G, Hao C, Li X, Li T. Adsorption performance of a polysaccharide composite hydrogel based on crosslinked glucan/chitosan for heavy metal ions. Composites Part B. 2019;169:45–54.10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.03.082Search in Google Scholar

[27] Rajamani M, Rajendrakumar K. Chitosan-boehmite desiccant composite as a promising adsorbent towards heavy metal removal. J Environ Manage. 2019;244:257–64.10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.056Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Aili Y. Preparation and adsorption properties of graphene oxide–chitosan composite adsorbent. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2018;47(5):1583–8.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Guixia Z, Xuemei R, Xing G, Xiaoli T, Jiaxing L, Changlun C, et al. Removal of Pb2+ ions from aqueous solutions on few-layered graphene oxide nanosheets. Dalton Trans. 2011;40(41):10945–52.10.1039/c1dt11005eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Li Shiyou SD. Characteristics and mechanism of adsorption of U(VI) on chitosan/graphene oxide composites. J Environ Sci. 2017;37(04):1388–95.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Li L, Fan L, Sun M, Qiu H, Li X, Duan H, et al. Adsorbent for hydroquinone removal based on graphene oxide functionalized with magnetic cyclodextrin–chitosan. Colloids Surf B. 2013;58(7):169–75.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.03.058Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Chen AH, Liu SC, Chen CY, Chen CY. Comparative adsorption ofCu2+, Zn(II), and Pb2+ ions in aqueous solution on the crosslinked chitosan with epichlorohydrin. J Hazard Mater. 2008;154(1):184–91.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.10.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Ramnani SP, Sabharwal S. Adsorption behavior of Cr(VI) onto radiation crosslinked chitosan and its possible application for the treatment of wastewater containing Cr(VI). React Funct Polym. 2006;66(9):902–9.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2005.11.017Search in Google Scholar

[34] Lulu F. Preparation of chitosan-based magnetic adsorbent and its application in water treatment. Shandong, China: University of Jinan; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Putro JN, Santoso SP, Ismadji S, Ju YH. Investigation of heavy metal adsorption in binary system by nanocrystalline cellulose – bentonite nanocomposite: improvement on extended Langmuir isotherm model. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017;246:166–77.10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.03.032Search in Google Scholar

[36] Gui CX, Wang Q-Q, Hao SM. Sandwichlike magnesium silicate/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for enhanced Pb2+ and Methylene Blue adsorption. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;16:14653–9.10.1021/am503997eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Tadjarodi A, Moazen Ferdowsi S, Zare-Dorabei R, Barzin A. Highly efficient ultrasonic-assisted removal of Hg(II) ions on graphene oxide modified with 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone: adsorption isotherms and kinetics studies. Ultrason Sonochem. 2016;33:118–28.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.04.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Tadjarodi A, Moazen Ferdowsi S, Zare-Dorabei R, Barzin A. Organic–inorganic hybrid optical sensor based on disulfide zone impregnated on mesoporous SBA-15 for simultaneous detection and removal of Pb(II) ions in water samples: response surface method. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;S1350417716301286.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Zare-Dorabei R, Rahimi R, Koohi A, Zargari S. Preparation and characterization of a novel tetrakis(4-hydroxyphenyl)porphyrin–graphene oxide nanocomposite and application in an optical sensor and determination of mercury ion. RSC Adv. 2015;5(113):93310–7.10.1039/C5RA17047HSearch in Google Scholar

© 2020 Linbo Li et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Obituary for Prof. Dr. Jun-ichi Yoshida

- Regular Articles

- Optimization of microwave-assisted manganese leaching from electrolyte manganese residue

- Crustacean shell bio-refining to chitin by natural deep eutectic solvents

- The kinetics of the extraction of caffeine from guarana seed under the action of ultrasonic field with simultaneous cooling

- Biocomposite scaffold preparation from hydroxyapatite extracted from waste bovine bone

- A simple room temperature-static bioreactor for effective synthesis of hexyl acetate

- Biofabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles, characterization and cytotoxicity against pediatric leukemia cell lines

- Efficient synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using guar gum as stabilizer and their applications as catalyst in reduction reactions and degradation of azo dyes

- Isolation of biosurfactant producing bacteria from Potwar oil fields: Effect of non-fossil fuel based carbon sources

- Green synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic applications of silver nanoparticles using Diospyros lotus

- Dielectric properties and microwave heating behavior of neutral leaching residues from zinc metallurgy in the microwave field

- Green synthesis and stabilization of silver nanoparticles using Lysimachia foenum-graecum Hance extract and their antibacterial activity

- Microwave-induced heating behavior of Y-TZP ceramics under multiphysics system

- Synthesis and catalytic properties of nickel salts of Keggin-type heteropolyacids embedded metal-organic framework hybrid nanocatalyst

- Preparation and properties of hydrogel based on sawdust cellulose for environmentally friendly slow release fertilizers

- Structural characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic effects of iron nanoparticles synthesized using Asphodelus aestivus Brot. aqueous extract

- Phase transformation involved in the reduction process of magnesium oxide in calcined dolomite by ferrosilicon with additive of aluminum

- Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles from Syzygium cumini extract for photo-catalytic removal of lead (Pb) in explosive industrial wastewater

- The study on the influence of oxidation degree and temperature on the viscosity of biodiesel

- Prepare a catalyst consist of rare earth minerals to denitrate via NH3-SCR

- Bacterial nanobiotic potential

- Green synthesis and characterization of carboxymethyl guar gum: Application in textile printing technology

- Potential of adsorbents from agricultural wastes as alternative fillers in mixed matrix membrane for gas separation: A review

- Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of green synthesized nanosilver using Rosmarinus officinalis leaves

- Synthesis of biomass-supported CuNi zero-valent nanoparticles through wetness co-impregnation method for the removal of carcinogenic dyes and nitroarene

- Synthesis of 2,2′-dibenzoylaminodiphenyl disulfide based on Aspen Plus simulation and the development of green synthesis processes

- Catalytic performance of the biosynthesized AgNps from Bistorta amplexicaule: antifungal, bactericidal, and reduction of carcinogenic 4-nitrophenol

- Optical and antimicrobial properties of silver nanoparticles synthesized via green route using honey

- Adsorption of l-α-glycerophosphocholine on ion-exchange resin: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using dried extracts of Chlorella vulgaris and antibacterial activity studies

- Preparation of graphene oxide/chitosan complex and its adsorption properties for heavy metal ions

- Green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles from plant leaf extracts and their applications: A review

- Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical properties of carbon nanotubes used as cathode materials for Al–air batteries from a renewable source of water hyacinth

- Optimization of medium–low-grade phosphorus rock carbothermal reduction process by response surface methodology

- The study of rod-shaped TiO2 composite material in the protection of stone cultural relics

- Eco-friendly synthesis of AuNPs for cutaneous wound-healing applications in nursing care after surgery

- Green approach in fabrication of photocatalytic, antimicrobial, and antioxidant zinc oxide nanoparticles – hydrothermal synthesis using clove hydroalcoholic extract and optimization of the process

- Green synthesis: Proposed mechanism and factors influencing the synthesis of platinum nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of 3-(1-naphthyl), 4-methyl-3-(1-naphthyl) coumarins and 3-phenylcoumarins using dual-frequency ultrasonication

- Optimization for removal efficiency of fluoride using La(iii)–Al(iii)-activated carbon modified by chemical route

- In vitro biological activity of Hydroclathrus clathratus and its use as an extracellular bioreductant for silver nanoparticle formation

- Evaluation of saponin-rich/poor leaf extract-mediated silver nanoparticles and their antifungal capacity

- Propylene carbonate synthesis from propylene oxide and CO2 over Ga-Silicate-1 catalyst

- Environmentally benevolent synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Olea ferruginea Royle for antibacterial and antioxidant activities

- Eco-synthesis and characterization of titanium nanoparticles: Testing its cytotoxicity and antibacterial effects

- A novel biofabrication of gold nanoparticles using Erythrina senegalensis leaf extract and their ameliorative effect on mycoplasmal pneumonia for treating lung infection in nursing care

- Phytosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using the costus extract for bactericidal application against foodborne pathogens

- Temperature effects on electrospun chitosan nanofibers

- An electrochemical method to investigate the effects of compound composition on gold dissolution in thiosulfate solution

- Trillium govanianum Wall. Ex. Royle rhizomes extract-medicated silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activity

- In vitro bactericidal, antidiabetic, cytotoxic, anticoagulant, and hemolytic effect of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles using Allium sativum clove extract incubated at various temperatures

- The green synthesis of N-hydroxyethyl-substituted 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines with acidic ionic liquid as catalyst

- Effect of KMnO4 on catalytic combustion performance of semi-coke

- Removal of Congo red and malachite green from aqueous solution using heterogeneous Ag/ZnCo-ZIF catalyst in the presence of hydrogen peroxide

- Nucleotide-based green synthesis of lanthanide coordination polymers for tunable white-light emission

- Determination of life cycle GHG emission factor for paper products of Vietnam

- Parabolic trough solar collectors: A general overview of technology, industrial applications, energy market, modeling, and standards

- Structural characteristics of plant cell wall elucidated by solution-state 2D NMR spectroscopy with an optimized procedure

- Sustainable utilization of a converter slagging agent prepared by converter precipitator dust and oxide scale

- Efficacy of chitosan silver nanoparticles from shrimp-shell wastes against major mosquito vectors of public health importance

- Effectiveness of six different methods in green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles using propolis extract: Screening and characterization

- Characterizations and analysis of the antioxidant, antimicrobial, and dye reduction ability of green synthesized silver nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of bio-fabricated selenium nanoparticles to improve the growth of wheat plants under drought stress

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Valeriana jatamansi shoots extract and its antimicrobial activity

- Characterization and biological activities of synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using the extract of Acantholimon serotinum

- Effect of calcination temperature on rare earth tailing catalysts for catalytic methane combustion

- Enhanced diuretic action of furosemide by complexation with β-cyclodextrin in the presence of sodium lauryl sulfate

- Development of chitosan/agar-silver nanoparticles-coated paper for antibacterial application

- Preparation, characterization, and catalytic performance of Pd–Ni/AC bimetallic nano-catalysts

- Acid red G dye removal from aqueous solutions by porous ceramsite produced from solid wastes: Batch and fixed-bed studies

- Review Articles

- Recent advances in the catalytic applications of GO/rGO for green organic synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Obituary for Prof. Dr. Jun-ichi Yoshida

- Regular Articles

- Optimization of microwave-assisted manganese leaching from electrolyte manganese residue

- Crustacean shell bio-refining to chitin by natural deep eutectic solvents

- The kinetics of the extraction of caffeine from guarana seed under the action of ultrasonic field with simultaneous cooling

- Biocomposite scaffold preparation from hydroxyapatite extracted from waste bovine bone

- A simple room temperature-static bioreactor for effective synthesis of hexyl acetate

- Biofabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles, characterization and cytotoxicity against pediatric leukemia cell lines

- Efficient synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using guar gum as stabilizer and their applications as catalyst in reduction reactions and degradation of azo dyes

- Isolation of biosurfactant producing bacteria from Potwar oil fields: Effect of non-fossil fuel based carbon sources

- Green synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic applications of silver nanoparticles using Diospyros lotus

- Dielectric properties and microwave heating behavior of neutral leaching residues from zinc metallurgy in the microwave field

- Green synthesis and stabilization of silver nanoparticles using Lysimachia foenum-graecum Hance extract and their antibacterial activity

- Microwave-induced heating behavior of Y-TZP ceramics under multiphysics system

- Synthesis and catalytic properties of nickel salts of Keggin-type heteropolyacids embedded metal-organic framework hybrid nanocatalyst

- Preparation and properties of hydrogel based on sawdust cellulose for environmentally friendly slow release fertilizers

- Structural characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic effects of iron nanoparticles synthesized using Asphodelus aestivus Brot. aqueous extract

- Phase transformation involved in the reduction process of magnesium oxide in calcined dolomite by ferrosilicon with additive of aluminum

- Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles from Syzygium cumini extract for photo-catalytic removal of lead (Pb) in explosive industrial wastewater

- The study on the influence of oxidation degree and temperature on the viscosity of biodiesel

- Prepare a catalyst consist of rare earth minerals to denitrate via NH3-SCR

- Bacterial nanobiotic potential

- Green synthesis and characterization of carboxymethyl guar gum: Application in textile printing technology

- Potential of adsorbents from agricultural wastes as alternative fillers in mixed matrix membrane for gas separation: A review

- Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of green synthesized nanosilver using Rosmarinus officinalis leaves

- Synthesis of biomass-supported CuNi zero-valent nanoparticles through wetness co-impregnation method for the removal of carcinogenic dyes and nitroarene

- Synthesis of 2,2′-dibenzoylaminodiphenyl disulfide based on Aspen Plus simulation and the development of green synthesis processes

- Catalytic performance of the biosynthesized AgNps from Bistorta amplexicaule: antifungal, bactericidal, and reduction of carcinogenic 4-nitrophenol

- Optical and antimicrobial properties of silver nanoparticles synthesized via green route using honey

- Adsorption of l-α-glycerophosphocholine on ion-exchange resin: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies

- Microwave-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using dried extracts of Chlorella vulgaris and antibacterial activity studies

- Preparation of graphene oxide/chitosan complex and its adsorption properties for heavy metal ions

- Green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles from plant leaf extracts and their applications: A review

- Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical properties of carbon nanotubes used as cathode materials for Al–air batteries from a renewable source of water hyacinth

- Optimization of medium–low-grade phosphorus rock carbothermal reduction process by response surface methodology

- The study of rod-shaped TiO2 composite material in the protection of stone cultural relics

- Eco-friendly synthesis of AuNPs for cutaneous wound-healing applications in nursing care after surgery

- Green approach in fabrication of photocatalytic, antimicrobial, and antioxidant zinc oxide nanoparticles – hydrothermal synthesis using clove hydroalcoholic extract and optimization of the process

- Green synthesis: Proposed mechanism and factors influencing the synthesis of platinum nanoparticles

- Green synthesis of 3-(1-naphthyl), 4-methyl-3-(1-naphthyl) coumarins and 3-phenylcoumarins using dual-frequency ultrasonication

- Optimization for removal efficiency of fluoride using La(iii)–Al(iii)-activated carbon modified by chemical route

- In vitro biological activity of Hydroclathrus clathratus and its use as an extracellular bioreductant for silver nanoparticle formation

- Evaluation of saponin-rich/poor leaf extract-mediated silver nanoparticles and their antifungal capacity

- Propylene carbonate synthesis from propylene oxide and CO2 over Ga-Silicate-1 catalyst

- Environmentally benevolent synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Olea ferruginea Royle for antibacterial and antioxidant activities

- Eco-synthesis and characterization of titanium nanoparticles: Testing its cytotoxicity and antibacterial effects

- A novel biofabrication of gold nanoparticles using Erythrina senegalensis leaf extract and their ameliorative effect on mycoplasmal pneumonia for treating lung infection in nursing care

- Phytosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using the costus extract for bactericidal application against foodborne pathogens

- Temperature effects on electrospun chitosan nanofibers

- An electrochemical method to investigate the effects of compound composition on gold dissolution in thiosulfate solution

- Trillium govanianum Wall. Ex. Royle rhizomes extract-medicated silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activity

- In vitro bactericidal, antidiabetic, cytotoxic, anticoagulant, and hemolytic effect of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles using Allium sativum clove extract incubated at various temperatures

- The green synthesis of N-hydroxyethyl-substituted 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines with acidic ionic liquid as catalyst

- Effect of KMnO4 on catalytic combustion performance of semi-coke

- Removal of Congo red and malachite green from aqueous solution using heterogeneous Ag/ZnCo-ZIF catalyst in the presence of hydrogen peroxide

- Nucleotide-based green synthesis of lanthanide coordination polymers for tunable white-light emission

- Determination of life cycle GHG emission factor for paper products of Vietnam

- Parabolic trough solar collectors: A general overview of technology, industrial applications, energy market, modeling, and standards

- Structural characteristics of plant cell wall elucidated by solution-state 2D NMR spectroscopy with an optimized procedure

- Sustainable utilization of a converter slagging agent prepared by converter precipitator dust and oxide scale

- Efficacy of chitosan silver nanoparticles from shrimp-shell wastes against major mosquito vectors of public health importance

- Effectiveness of six different methods in green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles using propolis extract: Screening and characterization

- Characterizations and analysis of the antioxidant, antimicrobial, and dye reduction ability of green synthesized silver nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of bio-fabricated selenium nanoparticles to improve the growth of wheat plants under drought stress

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Valeriana jatamansi shoots extract and its antimicrobial activity

- Characterization and biological activities of synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using the extract of Acantholimon serotinum

- Effect of calcination temperature on rare earth tailing catalysts for catalytic methane combustion

- Enhanced diuretic action of furosemide by complexation with β-cyclodextrin in the presence of sodium lauryl sulfate

- Development of chitosan/agar-silver nanoparticles-coated paper for antibacterial application

- Preparation, characterization, and catalytic performance of Pd–Ni/AC bimetallic nano-catalysts

- Acid red G dye removal from aqueous solutions by porous ceramsite produced from solid wastes: Batch and fixed-bed studies

- Review Articles

- Recent advances in the catalytic applications of GO/rGO for green organic synthesis