Abstract

Academic achievement matters to students’ opportunities and well-being. Although previous research has shown the relation between achievement and student engagement, the role played by students’ developmental needs demands further deepening. In this context, the aim of the present study is to analyse the mediating role of psychosocial development in the relationship between student engagement and academic achievement. The study included 708 adolescent students between 11 and 19 years of age (M = 13.98, SD = 2.16) and used the Student Engagement in School Four-Dimensional Scale, the short version of the Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory, and the grades for Portuguese and Mathematics. Results showed significant, positive, and weak to moderate correlations between student engagement, psychosocial development, and achievement. Findings of structural equation modelling, controlling for gender, age, and school type showed that (1) industry fully mediated the relation between cognitive, affective, and behavioural engagement and achievement; (2) identity fully mediated the association between cognitive engagement and achievement, and partially mediated the relation between affective engagement and achievement. In conclusion, the findings highlighted the role of psychosocial development in explaining the relation between student engagement and academic achievement, thus opening new perspectives for research and action.

1 Introduction

Academic achievement is a yardstick of school adjustment, with critical impacts on students’ present and future opportunities and well-being (Beck & Wiium, 2019; García-Martínez, Augusto-Landa, Quijano-López, & León, 2022; Olivier, Archambault, De Clercq, & Galand, 2019; Tao, Meng, Gao, & Yang, 2022). It is especially critical in adolescence, when achievement and student engagement in school tend to decrease as students face new developmental challenges, including school changes and career decisions (Bakadorova & Raufelder, 2019; Cadime et al., 2016; Hafen et al., 2012; Lemos, Gonçalves, & Cadima, 2020; Li, 2018; Olivier et al., 2019; Widlund, Tuominen, & Korhonen, 2021). In addition, research shows how academic achievement mirrors inequalities in students’ social contexts and opportunities (Beck & Wiium, 2019; Behr & Fugger, 2020; Dixson, Roberson, & Worrell, 2017; Tomaszewski, Xiang, & Western, 2020; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2013), thus integrating education’s challenge regarding quality, equality, and equity (UNESCO, 2016, 2019).

In this context, research highlights student engagement as a protective asset regarding adolescent students’ achievement and well-being, responsive to contextual features, relations, and opportunities (Lemos et al., 2020; Tao et al., 2022). Student engagement addresses student involvement and commitment to learning and school (Chase, Hilliard, John Geldhof, Warren, & Lerner, 2014; Lam et al., 2014). It is “a centripetal force attracting students to school” (Veiga et al., 2021, p. 1). One important feature is the concept’s multidimensionality, which enriches its explanatory power and allows customised interventions (Estévez et al., 2021; Fung, Tan, & Chen, 2018; Li, 2018). Many studies found evidence justifying a three-fold model of student engagement comprising cognitive, affective, and behavioural dimensions (Carvalho & Veiga, 2023; Salmela‐Aro, Tang, Symonds, & Upadyaya, 2021). The cognitive dimension encompasses students’ self-regulatory and learning strategies; the affective dimension conveys students’ identification with school and affection towards teachers and peers; and the behavioural dimension addresses students’ behaviours in school and classroom (Veiga et al., 2021). Other studies found that the agentic dimension amplified the concept’s explanatory power by adding students’ proactive, constructive, and reciprocal contributions to their own learning and success (Mameli & Passini, 2017; Reeve, Cheon, & Jang, 2020; Veiga et al., 2021).

However, despite its strength, the engagement-achievement relation does not fully explain academic achievement, and research should consider other factors (Lam et al., 2014; Tomaszewski et al., 2020), including students’ developmental needs (Cadime et al., 2016; Marttinen, Dietrich, & Salmela-Aro, 2018). Consequently, this study aims to deepen the engagement–achievement relation in adolescent students by analysing the mediating role of Erikson’s psychosocial development (Erikson, 1968/1994; Newman & Newman, 2015).

Erikson suggests that, at each stage of human development, the interplay of the contextual, biological, and psychological systems presents specific changes and challenges, which trigger a sort of crisis represented by two opposite poles. Handling each crisis demands reorganisation, learning, and changes in self-concept, meaning “a new view of the self in society and a new way of relating to others” (Newman & Newman, 2015, p. 65). It is almost as if, at each stage, one should answer a fundamental question (Veiga, 2002). To Erikson, a human strength (ego quality) or pathology emerges from each stage’s successful or unsuccessful resolution. Table 1 presents the five stages of childhood and adolescence, their respective strengths or pathologies, and the questions that may illustrate each stage. Psychosocial development shows the importance of nurturing and enhancing skills and strengths to cope with new development challenges (Newman & Newman, 2015), including, for example, school transitions, achievement demands, and level of stress (Cadime et al., 2016; Lemos et al., 2020; Li, 2018).

Erikson’s psychosocial development stages

| Age | Stage | Strength and pathology | Sample question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infancy | Basic trust vs mistrust | Hope/withdrawal | Can I trust my surroundings and myself? |

| Early childhood | Autonomy vs shame or doubt | Will/compulsion | How free do I feel to explore objects and my surroundings? |

| Play age | Initiative vs guilt | Purpose/inhibition | Do I feel that my initiatives are valued? |

| School-age | Industry vs inferiority | Competence/inertia | Am I capable of doing what I am requested to do well? |

| Adolescence | Identity vs identity confusion | Fidelity/repudiation | Do I know who I am and what I want to be? |

Despite the contribution of psychosocial development to school adjustment (Batra, 2013; Cross & Cross, 2017), research on its relation with student engagement is considered scarce and necessary (Carvalho & Veiga, 2022, 2023). It is this challenge that the present study aims to address. To this end, this introduction is complemented by relevant findings on student engagement, psychosocial development, achievement, and their relation. The section concludes with the presentation of the main questions and hypotheses of the study.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Student Engagement and Academic Achievement

The relevance of student engagement for adolescents’ academic achievement is well supported by extant research (Carvalho & Veiga, 2023; Chase et al., 2014; Lei, Cui, & Zhou, 2018; Li, 2018; Martínez, Oliveira, Murgui, & Veiga, 2024; Tao et al., 2022), especially in students facing higher social disadvantage (Salmela-Aro et al., 2022; Tomaszewski et al., 2020; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2013). The engagement–achievement relation was confirmed across countries and cultures (Fung et al., 2018; Lam et al., 2014; Li, 2018; Tao et al., 2022). However, this relation is not straightforward (Lei et al., 2018). After all, students may achieve and not be engaged in school or be engaged in school and still find it challenging to achieve (Chase et al., 2014; Shernoff, 2013). In addition, while some studies found a significant relation between achievement and the four dimensions of engagement, including the agentic dimension (Mameli & Passini, 2017; Veiga, 2016), others emphasised the role of behavioural and agentic engagement as predictors of achievement (Reeve et al., 2020; Tomás, Gutiérrez, Georgieva, & Hernández, 2020). Therefore, more studies are needed to further the engagement–achievement relation and the role of student engagement’s dimensions.

2.2 Student Engagement and Psychosocial Development

The decline in school adjustment, motivation, and student engagement in adolescence (Carvalho & Veiga, 2023; Ramos-Díaz, Rodríguez-Fernández, & Revuelta, 2016; Yeager, Lee, & Dahl, 2018) brings forward the confluence of academic, developmental, and social challenges that begin with adolescence onset (Binning et al., 2019). This reality requires considering the complexity of adolescence’s developmental demands and tasks, with particular attention to identity (Cadime et al., 2016; Flum & Kaplan, 2012; Marttinen et al., 2018). Accordingly, the present study suggests that psychosocial development, following Erikson’s five stages of childhood and adolescence – trust autonomy, initiative, industry, and identity (Erikson, 1968/1994) – may further the engagement-achievement relation.

Although we found no specific evidence on the relation between psychosocial stages and student engagement or its dimensions (Carvalho & Veiga, 2022, 2023), other studies confirmed the relation between psychosocial resources, with particular emphasis on identity, the main psychosocial stage and task of adolescence, and adolescent students’ health, well-being, and school adjustment (Almroth, László, Kosidou, & Galanti, 2020; Beck & Wiium, 2019; Binning et al., 2019; Flum & Kaplan, 2012; Hafen et al., 2012; Marttinen et al., 2018; Smith, Mann, & Kristjansson, 2020). Other studies underlined the critical relation between self-concept, a concept closely related to psychosocial development, and adolescent student engagement (Dixson, 2021; Veiga, García, Reeve, Wentzel, & Garcia, 2015). Consequently, there are expectations regarding the relationship between psychosocial development stages and student engagement. Nevertheless, considering the scarcity of studies, further research is deemed needed.

2.3 Psychosocial Development and Academic Achievement

Although research using a broad definition of psychosocial factors in academic research exists (e.g. Dixson et al., 2017), studies on the relation between psychosocial development, including identity, and school adjustment, including achievement, seem missing (Almroth et al., 2020; Carvalho & Veiga, 2022; Flum & Kaplan, 2012; Grbić & Maksić, 2022). However, the relation between psychosocial development and adolescents’ strengths, mental and psychological health, well-being, and prosocial behaviour (Carvalho & Veiga, 2022; Dixson et al., 2017) raises expectations of a positive association with academic achievement.

Moreover, studies addressing psychosocial constructs with some relatedness to Erikson’s theory presented promising findings regarding achievement. It is the case of trust (Binning et al., 2019), autonomy (Hafen et al., 2012), academic self-concept (Bakadorova & Raufelder, 2019; Fernández-Lasarte, Goñi, Camino, & Zubeldia, 2018; Gasparotto, Szeremeta, Vagetti, Stoltz, & Oliveira, 2018), global self-worth (Fairlamb, 2022; Manrique Millones, Ghesquière, & Van Leeuwen, 2014), positive identity (Beck & Wiium, 2019), self-affirmation intervention (Borman, Grigg, Rozek, Hanselman, & Dewey, 2018), identity exploration interventions (Flum & Kaplan, 2012), vocational identity (Marttinen et al., 2018), or ethnic-identity (Debrosse, Rossignac-Milon, Taylor, & Destin, 2018; Schotte, Stanat, & Edele, 2018).

Erikson’s theory offers a cohesive framework for the study of the relation between psychosocial development and achievement (Mahama, Asamoah-Gyimah, & Dramanu, 2024). However, one challenge arises: to go beyond the study of isolated concepts or stages, such as identity, and valuing psychosocial development as a whole, that is, including all the intertwined childhood and adolescence stages (Carvalho & Veiga, 2022; Dunkel & Harbke, 2017; Erikson, 1968/1994).

2.4 Mediating Role of Psychosocial Development

Research in the context of the self-system models valued student engagement as a mediator between, on the one hand, students’ perceptions of the context and motivational beliefs and, on the other, academic achievement (Reeve et al., 2020; Tao et al., 2022; Wang & Eccles, 2013). The relation context → self → engagement → achievement (Reeve et al., 2020) is so widespread that it is difficult to find research studying how variables, such as psychosocial development, may explain the engagement–achievement relation (Carvalho & Veiga, 2023; Demirci, 2020), which, as we said earlier, is not straightforward (Lam et al., 2014; Lei et al., 2018; Tomaszewski et al., 2020).

Previous studies reinforced this idea, showing how self-efficacy reduced student engagement explanation power (Olivier et al., 2019), how student engagement explains a small percentage of achievement when academic self-concept is considered (Dixson, 2021), how psychosocial variables, such as hope and social competencies, mediated student engagement relation to well-being (Demirci, 2020). In synthesis, these findings stressed that student engagement does not fully account for achievement (Lam et al., 2014; Tomaszewski et al., 2020), the need to deepen the engagement–achievement relation and, in this relation, the role of psychosocial development.

2.5 Current Study

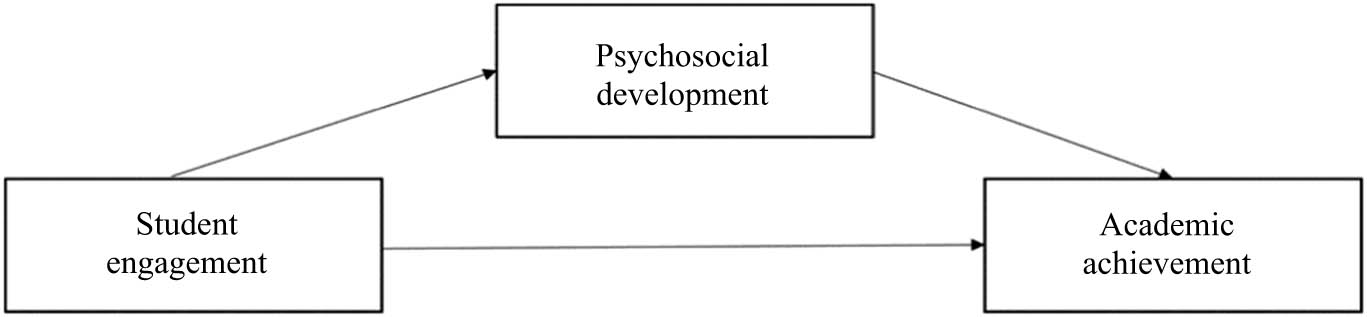

The aim of this research is to deepen the study of student engagement–achievement relations by analysing the mediating role of psychosocial development. The theoretical model is presented in Figure 1, suggesting that student engagement has a direct and predictive effect on academic achievement and an indirect effect mediated by psychosocial development.

Mediation model.

The research considers two questions and four hypotheses derived from the literature review. The first question of the study is: How do student engagement, psychosocial development, and academic performance correlate? This question is based on studies that highlight the importance of multidimensional engagement for academic performance (Carvalho & Veiga, 2023; Chase et al., 2014; Lei et al., 2018; Li, 2018; Tao et al., 2022) and the relevance of psychosocial development for school adaptation (Batra, 2013; Cross & Cross, 2017). The hypotheses are as follows:

H1: There are positive and significant correlations between the dimensions of student engagement (cognitive, affective, behavioural, and agent) and academic performance, as evidenced by studies such as those by Lam et al. (2014) and Veiga (2016).

H2: There are positive and significant correlations between the dimensions of student engagement (cognitive, affective, behavioural, and agentic) and the stages of psychosocial development (trust, autonomy, initiative, industry, and identity), supported by research exploring the relationship between engagement and psychosocial development (Carvalho & Veiga, 2022; Dixson, 2021).

H3: There are positive and significant correlations between the stages of psychosocial development (confidence, autonomy, initiative, industry, and identity) and academic performance, as suggested by studies on the influence of psychosocial development on school adaptation (Almroth et al., 2020; Beck & Wiium, 2019).

The second question is: How do stages of psychosocial development mediate the relationship between student engagement and academic performance? This question is based on the literature that suggests the mediation of psychosocial variables in the relationship between engagement and performance (Reeve et al., 2020; Tao et al., 2022). Our hypothesis suggests:

H4: Psychosocial stages mediate the relationship between student engagement and academic performance, as discussed in studies exploring the mediation of psychosocial factors (Demirci, 2020; Olivier et al., 2019).

3 Method

3.1 Sample

The study’s exploratory nature was reflected in the option for a non-probabilistic convenience sampling, including adolescent students from the 6th, 9th, and 11th grades from three different schools in Lisbon, Portugal. The study included 708 students. The mean age was 13.98 years (SD = 2.16) and included 385 early adolescents, aged between 10 and 14 years (54.4%), and 323 late adolescents, aged between 15 and 19 years (45.6%). Regarding gender, 397 students were girls (56.1%) and 311 were boys (43.9%). Regarding schools, 414 studied in public schools (58.5%) and 294 in private schools (41.5%).

3.2 Measures

Student engagement in school was assessed using the Student Engagement in School: Four-Dimensional Scale (SES-4DS) (Veiga, 2016), assessing cognitive, affective, behavioural, and agentic dimensions of engagement. The measure has 20 items, 7 of which are reversed. The scale presented five items per dimension, including the cognitive dimension (e.g. “I try to connect what I learn in one discipline with what I learn in others”), the affective dimension (e.g. “My school is a place where I feel excluded.”), the behavioural dimension (e.g. “I am distracted in the classroom”), and the agentic dimension (e.g. “During lessons, I intervene to express my opinions”). Participants answered using a Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). The scale’s psychometric properties found in earlier studies (Veiga, 2016) were confirmed in later research (e.g. Veiga et al., 2021). The CFA results in this study presented a good model fit – χ 2(161) = 548.28, p < 0.001, χ 2/df = 3.41, goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.925, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.921; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.058 – and factor loadings between 0.30 and 0.87. In the present study, the cognitive, affective, and agentic dimensions of engagement presented adequate internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha values (Table 1). According to Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black (1998), these dimensions had good reliabilities (α ≥ 0.70). The behavioural dimension showed a lower but acceptable value (α = 0.68).

Psychosocial development assessment used a shorter version of the Erikson Psychosocial Inventory (EPSI) scale (Rosenthal, Gurney, & Moore, 1981), built to assess Erikson’s six stages of childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. The original scale has 72 items, evaluating each stage’s crisis positive and negative resolution (12 items per stage). Although supported by earlier adaptations to Portuguese higher education students (Cabral & Matos, 2010), the adaptation followed the steps suggested by the International Test Commission (ITC, 2017). Aiming for a shorter version, an exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation allowed a solution of 3 items assessing each stage, which explained 61.14% of the variance. A confirmatory factor analysis validated the model’s good fit – χ 2(80) = 234.93, p < 0.001, χ 2/df = 2.94, CFI = 0.933; RMSEA = 0.052 – with factor loadings ranging between 0.35 and 0.90. This shorter version of EPSI, presented in Appendix 1, addressed the psychosocial stages of childhood and adolescence, including trust (e.g. “I trust people”), autonomy (e.g. “I can’t make sense of my life”), initiative (e.g. “I am able to be first with new ideas”), industry (e.g. “I’m trying hard to achieve my goals”), and identity (e.g. “The important things in life are clear to me”). Five items are reversed. Participants answered using a Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). As to reliability (Table 1), the total score of the psychosocial development presented an adequate internal consistency (α = 0.78), and the five dimensions’ values ranged between 0.57 (autonomy) and 0.69 (industry and identity).

Academic achievement and background variables – Students answered two questions regarding their academic grades in Portuguese and Mathematics last year (1–5 scale). The study used the average of the two grades to measure academic achievement. The study also considered gender (girls and boys) and age (years) using two closed questions. Regarding age, the study followed the UN’s adolescence definition, valuing the distinction between early-young (10–14 years) and late-older (15–19 years) adolescence (Patton et al., 2016). Finally, the study considered school type, distinguishing between public (government funding) and private (family fees) schools.

3.3 Procedure

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Education – University of Lisbon, the Portuguese Ministry of Education, and each school board. The authors ensured ethics warrants concerning informed consent, privacy, and confidentiality. Informed consent included two actions: (a) a visit to all classrooms presenting the study, ensuring that students understood the voluntary nature of participation and the warrants regarding confidentiality and anonymity; (b) a letter to parents presenting the study and requesting a signed authorisation for their children’s participation.

Researchers conducted the data collection process in each school, using IT equipment specifically lent by Microsoft Portugal and an online questionnaire (Google Form). The fact that all questions were mandatory reduced data missing issues. A total of 804 students participated in the study. After a general analysis, 74 questionnaires filled in automatically, randomly, or in less than 10 min were removed. Later, after exploratory analysis, 22 questionnaires were removed as outliers. Finally, 708 questionnaires entered the study.

3.4 Data Analyses

First, IBM SPSS (27 version) was used to conduct a preliminary exploratory and descriptive analysis of the study’s main variables and examine their correlations using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Correlation coefficients between pairs of variables were all less than 0.80, suggesting that there is no significant multicollinearity problem in the data. Additionally, there were no missing values in the data. The main hypotheses of this study were tested using a structural equation model (SEM) with AMOS 27 version (Arbuckle, 2020). First, Harman’s single-factor test was used to verify common method bias. The total variance explained by a single factor was 19.88%, below the threshold of 50%, suggesting that common method bias is not a significant concern in this dataset. The SEM model was assessed using a series of goodness-of-fit indicators, namely, the chi-square test (χ 2) and its associated probability (p), χ 2/df, the GFI, CFI (Bentler, 1990) and the root RMSEA (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), along with its 90% confidence interval (CI), as recommended by MacCallum and Austin (2000). Model fit was considered good when χ 2/df was lower than 3 (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003), CFI and GFI values were above 0.90, and RMSEA was lower than 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

To determine possible problems with the hypothesised models that could be solved in the context of the available data, modification indices provided by AMOS (Arbuckle, 2020) were examined. According to the recommendations concerning model re-specification, only the most significant modifications to the hypothesised model were carried out when these were conceptually and theoretically justifiable (Kleine, 2016; MacCallum, 1995).

The mediation analyses analysed the indirect effect of student engagement on academic achievement via psychosocial development using a bootstrap bias-corrected confidence interval (BC 90% CI) method (Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). The size of the bootstrap resample was defined as 200 (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This method is recommended in the literature, rather than more traditional approaches, such as Sobel’s test (Cheung & Lau, 2008).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between Study Variables

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics regarding the main study variables, student engagement in school, psychosocial development, academic achievement, correlation matrix, and reliability. Findings show that all dimensions of student engagement in school were positively correlated [r (min–max) = 0.17–0.50], except the behavioural and agentic dimensions, which were not significantly correlated. Similarly, all dimensions of psychosocial development were positively correlated, the weakest relation being the one between trust and initiative (r = 0.08) and the strongest being between initiative and industry (r = 0.43). In what regards the associations between student engagement and academic achievement, all correlations were significant, positive, and weak [r (min–max) = 0.13–0.26], providing support to H1. As to the relations between student engagement and psychosocial development, positive and weak to moderate correlations were found between all dimensions, the weakest being the relation between autonomy and cognitive engagement (r = 0.13) and the strongest being the one between trust and affective engagement (r = 0.50). Therefore, these results support H2. Regarding the associations between psychosocial development and academic achievement, all correlations were significant, positive, and weak to moderate [r (min–max) = 0.09–0.37], except for the relation between identity and academic achievement, which was not statistically significant. Therefore, these findings partially support H3.

Descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and Cronbach’s alpha for study variables (N = 708)

| Variables | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement | ||||||||||||

| Cognitive (1) | 3.64 (.96) | (0.70) | ||||||||||

| Affective (2) | 4.60 (1.05) | 0.19*** | (0.88) | |||||||||

| Behavioural (3) | 5.11 (0.75) | 0.27*** | 0.17*** | (0.68) | ||||||||

| Agentic (4) | 3.63 (1.14) | 0.50*** | 0.36*** | 0.07 | (0.81) | |||||||

| Psychosocial development | ||||||||||||

| Trust (5) | 4.34 (0.99) | 0.23*** | 0.50*** | 0.21*** | 0.20*** | (0.60) | ||||||

| Autonomy (6) | 4.53 (1.06) | 0.13*** | 0.46*** | 0.15*** | 0.31*** | 0.28*** | (0.57) | |||||

| Initiative (7) | 4.87 (0.74) | 0.38*** | 0.21*** | 0.14*** | 0.47*** | 0.08* | 0.28*** | (0.59) | ||||

| Industry (8) | 4.36 (1.00) | 0.46*** | 0.27*** | 0.42*** | 0.32*** | 0.27*** | 0.25*** | 0.43*** | (0.69) | |||

| Identity (9) | 4.86 (0.91) | 0.28*** | 0.39*** | 0.20*** | 0.31*** | 0.30*** | 0.38*** | 0.29*** | 0.34*** | (0.69) | ||

| Total (10) | 4.59 (0.62) | 0.44*** | 0.57*** | 0.35*** | 0.48*** | 0.61*** | 0.69*** | 0.58*** | 0.70*** | 0.70*** | (0.78) | |

| Academic achievement (11) | 3.57 (0.79) | 0.17*** | 0.13*** | 0.26*** | 0.19*** | 0.09* | 0.10* | 0.19*** | 0.37*** | −0.04 | 0.22*** | — |

Note. The scales for engagement and psychosocial development range from 1 to 6; the scale for academic achievement range from 1 to 5; the reliability is presented in parentheses along diagonals; no Cronbach’s alpha was computed for academic achievement.

*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

4.2 Structural Models: Psychosocial Development as Mediator Between Student Engagement and Academic Achievement

Five mediation models were analysed, with each dimension of psychosocial development as a mediator; only industry and identity were shown to mediate the relationship between engagement and academic achievement. Therefore, these two models are described in detail below.

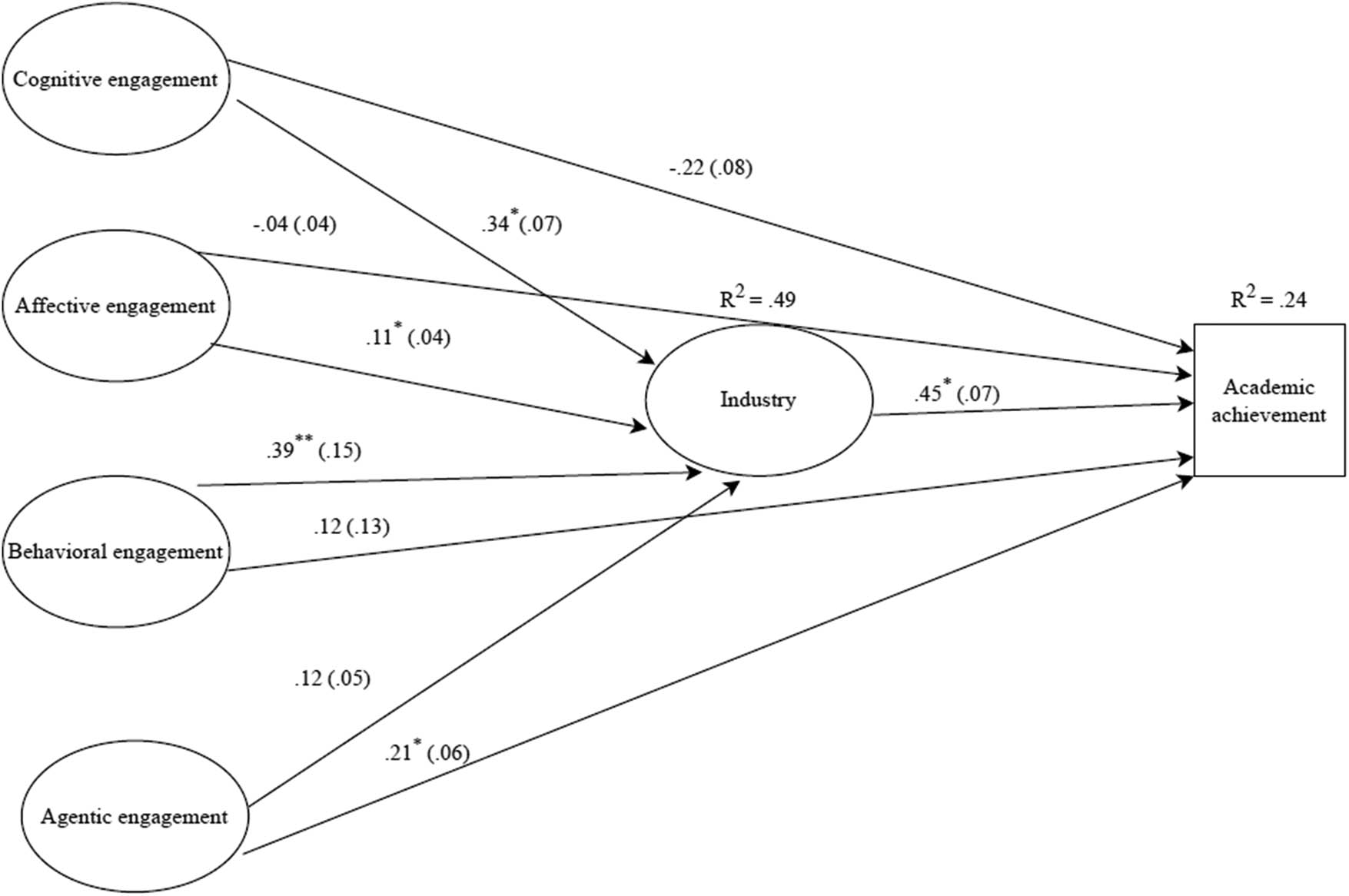

As shown in Figure 2, the cognitive, affective, and behavioural dimensions of student engagement were positively related to industry: β = 0.34, p = 0.013 for the cognitive dimension, β = 0.11, p = 0.016 for the affective dimension, and β = 0.39, p = 0.007 for the behavioural dimension. Conversely, none of these dimensions were directly associated with academic achievement (all p > 0.05). Industry was also positively and significantly associated with academic achievement, β = 0.45, p = 0.020. The mediation analysis, as Table 3 shows, evidenced that the indirect effects were statistically significant for the cognitive dimension, β = 0.15, 95% CI [0.06; 0.25], p = 0.012, for the affective dimension, β = 0.05, 95% CI 0.02; 0.10], p = 0.016, and for the behavioural dimension, β = 0.18, 95% CI 0.11; 0.25], p = 0.014. As the direct effects were non-significant, the industry fully mediates the relationship between the cognitive, affective, and behavioural dimensions and academic achievement. Additionally, the agentic dimension showed a direct positive and significant relation with academic achievement, β = 0.21, p = 0.034. The same results were obtained when controlling for gender, age (early vs late adolescence) and school type (public vs private), except for the mediation of the relationship between cognitive engagement and achievement, in which industry is a partial mediator (Figure 2). The model also presented an acceptable model fit (χ 2 = 810.82, df = 236; χ 2/df = 3.44; CFI = 0.903; GFI = 0.907; RMSEA = 0.059, RMSEA 90% CI [0.054, 0.063]).

Results of the structural model for academic achievement with industry as mediator. Note. While not presented, the standardised covariances between engagement dimensions were included, varying between 0.04 and 0.67, all with p < 0.001, except for the covariance between agentic and behavioural engagement. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Direct and indirect effects

| Path | Mediator | Direct effect | Indirect effect | 95% CI for indirect effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive → Achievement | Industry | −0.22 | 0.15* | 0.06; 0.25 |

| Affective → Achievement | −0.04 | 0.05* | 0.02; 0.10 | |

| Behavioural → Achievement | 0.12 | 0.18* | 0.11; 0.25 | |

| Agentic → Achievement | 0.21* | 0.06 | 0.00; 0.12 | |

| Cognitive → Achievement | Identity | 0.00 | −0.05* | −0.10; −0.01 |

| Affective → Achievement | 0.12** | −0.10** | −0.15; −0.07 | |

| Behavioural → Achievement | 0.30* | −0.02 | −0.06; 0.00 | |

| Agentic → Achievement | 0.28* | −0.03 | −0.06; 0.02 |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

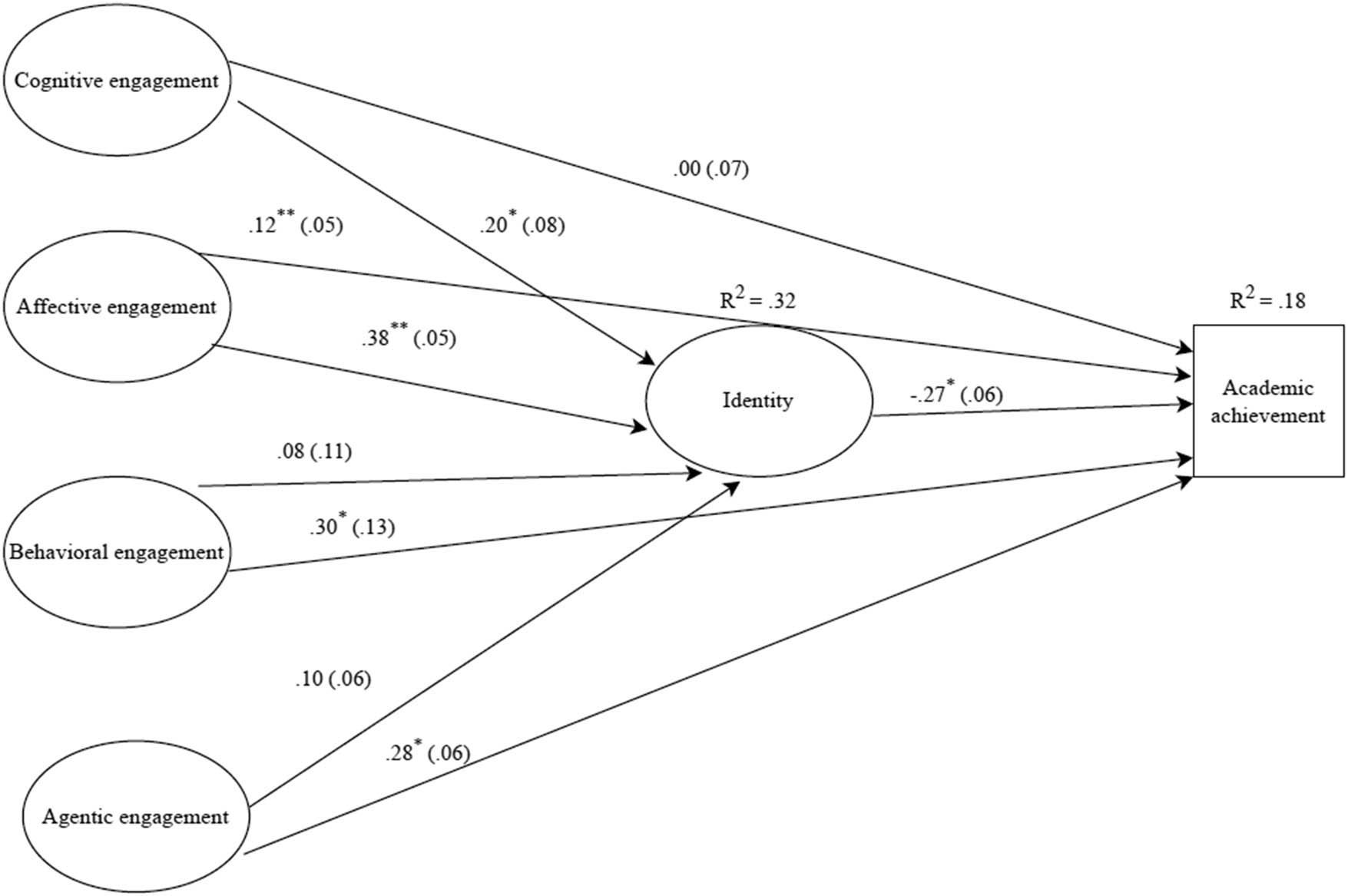

A second model was tested, with identity as a mediator (Figure 3). Only the cognitive and affective dimensions were positively related to identity, β = 0.20, p = 0.047 and β = 0.38, p = 0.006, respectively. Of these two dimensions, only the affective one was directly associated with academic achievement, β = 0.12, p = 0.008. Moreover, identity was negatively and significantly associated with academic achievement, β = −0.27, p = 0.013. Regarding the mediation analysis, Table 3 shows how the indirect effects were statistically significant for the cognitive dimension, β = −0.05, 95% CI −0.10; −0.01], p = 0.046, and for the affective dimension, β = −0.10, 95% CI [−0.15; −0.07], p = 0.006. Since the direct effect was non-significant for the cognitive dimension, identity is a full mediator of the relationship between this dimension and academic achievement; as for the affective dimension, identity partially mediates its relationship with academic achievement. Additionally, the agentic and behavioural dimensions showed direct positive and significant relations with academic achievement, β = 0.28, p = 0.032 and β = 0.30, p = 0.020, respectively. The same results were obtained when controlling for gender, age (early vs late adolescence), and school type (public vs private). This model also presented an acceptable model fit (χ 2 = 724.95, df = 236; χ 2/df = 3.07; CFI = 0.913; GFI = 0.917; RMSEA = 0.054, RMSEA 90% CI [0.050, 0.059]).

Results of the structural model for academic achievement with identity as mediator. Note. While not presented, the standardised covariances between engagement dimensions were included, varying between 0.03 and 0.67, all with p < 0.001, except for the covariance between agentic and behavioural engagement. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Thus, these findings support H4 only when considering industry and identity as mediators.

5 Discussion

The first question of the study focused on the correlations between the variables. The hypothesis valued the correlation between student engagement and achievement, between student engagement and psychosocial development and between psychosocial development and achievement.

5.1 Student Engagement and Achievement

Findings supported H1, showing that all dimensions of student engagement (cognitive, affective, behavioural, and agentic) were positively yet weakly correlated with academic achievement.

Results are consistent with empirical literature (Carvalho & Veiga, 2023; Wang, Degol, & Henry, 2019) and earlier studies using the four-dimensional model of student engagement (e.g. Mameli & Passini, 2017; Veiga, 2016). These findings justify student engagement’s relevance: a psychological process expressing how students interact with school and learning, which bridges students’ contextual factors (e.g. relation with teachers, parents, or peers) and personal factors (e.g. motivational beliefs) to outcomes such as learning and achievement (Lam et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2019). Similar results regarding the weak correlations were found in an international study with 12 countries, possibly pointing out how student engagement is just one of many variables that explain academic achievement (Lam et al., 2014).

The highest correlation was found for the agentic dimension, followed by the behavioural dimension. These findings are aligned with studies valuing the primacy of the agentic and behavioural dimensions regarding academic achievement (Reeve et al., 2020; Tomás et al., 2020). However, the cognitive and affective dimensions also present similar positive and significant correlations with achievement. Therefore, findings appear to corroborate the complementary nature of engagement dimensions towards school adjustment and general well-being (Finn & Zimmer, 2012; Lei et al., 2018), with affective and cognitive engagement playing a critical part (Storlie & Toomey, 2020). Earlier studies reinforced this idea by stressing how adolescent students who keep up with their tasks, comply, participate, and achieve but do not feel emotionally or cognitively engaged are, unnoticeably, at risk of mental health, ill-being, and burnout (Qahri-Saremi & Turel, 2016; Widlund et al., 2021).

5.2 Student Engagement and Psychosocial Development

Results supported H2 by presenting positive, weak-moderate correlations between all dimensions of student engagement and psychosocial development. The findings reinforced studies valuing the role of psychosocial development in school adjustment (Batra, 2013; Carvalho & Veiga, 2022; Cross & Cross, 2017).

Affective engagement’s correlation with total psychosocial development presented the highest magnitude, explained by the high correlation of affective engagement with trust and autonomy. Affective-trust correlation is consistent with the mutuality between trust – the cornerstone of vital personality, source of hope and optimism (Erikson & Erikson, 1998; Erikson, 1968/1994) – and the positive relations with the widening radius of significant persons and institutions (Erikson, 1968/1994) including relations in the school settings (Binning et al., 2019; Demirci, 2020). Affective-autonomy correlation is consistent with adolescents’ strive for autonomy (Hafen et al., 2012; Yeager et al., 2018), deeply related to will and purpose (Newman & Newman, 2015), which explains adolescent’s fierce concern with the level of relevance and autonomy existing in tasks and environments (Hafen et al., 2012; Yeager et al., 2018).

The cognitive and behavioural dimensions presented higher magnitude correlations with industry, which brings forward the beliefs in one’s abilities as a learner and a worker, or what one meaningfully can do (Erikson, 1968/1994; Newman & Newman, 2015). This correlation is consistent with studies that showed the relation between academic competence and intrinsic motivation (Yeager et al., 2018) or between academic self-concept and student engagement (Wang & Eccles, 2013).

The agentic dimension, valuing students’ proactive, constructive, and reciprocal contributions to their learning (Reeve et al., 2020), presented an expected higher correlation with initiative, which underlines students’ desire to explore the world purposefully and devise new ways to act upon it (Newman & Newman, 2015).

5.3 Psychosocial Development and Academic Achievement

Results partially supported H3, as all correlations between psychosocial development stages and academic achievement were significant, positive, and weak to moderate, except for identity, whose relation with academic achievement was not statistically significant. Findings are consistent with the claim of psychosocial development association with school adjustment (Batra, 2013; Carvalho & Veiga, 2022; Cross & Cross, 2017; Grbić & Maksić, 2022; Hamman & Hendricks, 2005), highlighting how students’ healthy development contributes to coping effectively with the academic and relational challenges of school and learning (Negru‐Subtirica, Damian, Pop, & Crocetti, 2023), which would translate into better academic achievement (Martínez et al., 2024).

Although literature stressed identity value for school adjustment (Beck & Wiium, 2019; Caraballo, 2019; Flum & Kaplan, 2012; Grbić & Maksić, 2022), in this study, the correlation with achievement was non-significant. An earlier study also found no relation between identity and academic expectations (Almroth et al., 2020). According to the authors, it is feasible that the identity resolution process, demanding adolescents’ reorganisation efforts with a certain degree of uncertainty, may develop as a different and independent process from academic achievement.

5.4 Mediating Role of Psychosocial Development

The second question of the study aimed to further knowledge on the engagement–achievement relationship, analysing the mediation role of psychosocial development stages. At this level, findings presented a mediation effect only for industry and identity, hence only partially confirming the hypothesis (H4). However, these two results are noteworthy. First, industry fully mediated the relationship between the cognitive, affective, and behavioural dimensions and academic achievement. Only the agentic dimension showed a direct positive and significant relation with academic achievement. Second, identity fully mediated the relationship between cognitive engagement and academic achievement and partially mediated the relation between affective engagement and academic achievement. Only the agentic and behavioural dimensions presented direct, positive, and significant relationships with academic achievement.

The mediating role of industry, fully explaining the relationship between the cognitive, affective, and behavioural dimensions and academic achievement, is consistent with studies empirically valuing self-efficacy (Olivier et al., 2019) or academic self-concept in explaining achievement (Bakadorova & Raufelder, 2019; Fernández-Lasarte et al., 2018; Gasparotto et al., 2018; Wang & Eccles, 2013). The present study shows that being engaged is not enough to achieve academically. Industry, the psychosocial stage related to students’ sense of competence, plays a critical role.

Industry is deeply related to school and its long-lasting effect on children’s and adolescents’ perceptions of their worth as learners and achievers, the value of learning, working, and contributing to society, and the best attitudes when facing new opportunities or challenges (Erikson & Erikson, 1998; Newman & Newman, 2015; Roeser, Peck, & Nasir, 2006). Industry effectively supports engagement translation into achievement. Therefore, it is possible that a lower sense of industry and competence, possibly emerging from the harsh schooling experiences of students from lower SES or immigrant families, may explain why students may be engaged yet not achieving (Shernoff, 2013). Furthering the idea, Erikson posits how inferiority, the counterpart of industry and competence, could lead to inertia, which “threatens to paralyse an individual’s productive life” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, pp. 76–77). Therefore, results underlined the need to care for each adolescent’s history as a student, supporting their passion for learning, optimistic regard towards their abilities, ability to cope with failure, and guidance to achieve academically and reach their goals (Newman & Newman, 2015).

Regarding identity, it fully mediated the effect of cognitive engagement on achievement and partially the effect of affective engagement on achievement. However, unlike industry, the mediation effect was negative. Developmental literature provides some explanation. Erikson introduced identity formation as adolescence’s main stage and task, which demands reviewing childhood identifications and experiences, integrating new changes, challenges, and perspectives, achieving a worldview with some level of sameness and continuity, developing a personal understanding and a way of envisaging the future to which one wants to commit (Erikson & Erikson, 1998; Erikson, 1968/1994; Hamman & Hendricks, 2005; Newman & Newman, 2015). It is quite a task! Plunging into identity formation, with a certain amount of uncertainty (Almroth et al., 2020) and the decrease in identity synthesis and increase in identity confusion throughout a considerable part of adolescence (Bogaerts et al., 2021), may require adolescent students’ cognitive and affective resources. Therefore, although behavioural and agentic engagement sustains achievement, in a sort of passive compliance to school precepts (Flum & Kaplan, 2012), identity formation disrupts the positive relation of cognitive and affective engagement with achievement.

Results are consistent with earlier studies showing how adolescents’ intrinsic motivation decreased when dealing with identity-related issues such as prioritising social goals, acquiring adolescent-specific social competence, or finding meaning and purpose (Yeager et al., 2018). These results matter greatly. First, they emphasise how adolescent students’ investment in identity exploration may, in many educational settings, be at odds with their learning tasks, schoolwork, and environments (Smith et al., 2020; Yeager et al., 2018). Second, they state that supporting students’ identity formation offers promising prospects regarding academic achievement (Flum & Kaplan, 2012; Hamman & Hendricks, 2005; Smith et al., 2020). Literature provides different directions for meaningful action regarding identity formation support: schoolwork rich in exploration opportunities and focusing on the whole person and not exclusively on academic achievement (Flum & Kaplan, 2012); meaningful activities whose purpose is to reach others and the world welfare (Yeager et al., 2018); adoption of the motto “restoring relationships to the heart of learning” (Roeser et al., 2006, p. 414); valuing positive and caring teacher-student and peers relationships; and fostering students belonging and participation (Flum & Kaplan, 2012).

Results from this study showed that it takes more than engagement to achieve. They showed that psychosocial development matters. It helps to deepen and explain the engagement–achievement relation, which, in our sample, is enhanced by industry and restrained by identity. These results highlight psychosocial development’s critical role in addressing the achievement gap (Dixson et al., 2017; Dixson, 2021). Regarding industry, students with a low sense of industry, possibly estranged from the school ways, may feel engaged but find it harder to achieve. Therefore, special attention is needed for students facing concurrent difficulties (Roeser et al., 2006), such as low SES families students (Dixson et al., 2017; Tomaszewski et al., 2020), minority or immigrant background groups students (Behr & Fugger, 2020; Debrosse et al., 2018; Schotte et al., 2018; Veiga et al., 2021), or students with learning specificities or high abilities (Carvalho & Veiga, 2022; Cross & Cross, 2017). Regarding identity, students who achieve, therefore signalling to the world that they are doing just fine but are affectively or cognitively disengaged, maybe invisibly at risk of mental health, ill-being, and burnout (Qahri-Saremi & Turel, 2016; Widlund et al., 2021). In this context, studies showed the effectiveness of identity interventions addressing the motivation and learning of all students (Flum & Kaplan, 2012).

5.5 Theoretical and Practical Implications

Theoretically, the study underscores the importance of psychosocial development in understanding how student engagement translates into academic success. It suggests that engagement alone does not fully explain achievement, pointing to the need for a comprehensive approach that includes developmental factors. For educational practice, the findings suggest designing interventions supporting engagement and psychosocial development. Schools should create environments that foster trust, autonomy, initiative, industry, and identity. Special attention should be given to at-risk students, and teacher training should include strategies to support psychosocial development.

5.6 Limitations and Future Research

There are significant limitations to consider. One is the specificity of the sample, with students from only three schools in the same city. More studies, with more random and representative samples, are needed to confirm and deepen results. Another limitation is the absence of contextual variables. Future research should address the role played by contextual variables, such as SES and family background (Chase et al., 2014; Lei et al., 2018; Manrique Millones et al., 2014). A third limitation is the measure used for psychosocial assessment, which, despite the psychometric quality, can be improved in search for a better match between theory and assessment (Carvalho & Veiga, 2022). Another important limitation is the study’s cross-sectional design, which does not allow conclusions about causal relations between the variables. New studies using a longitudinal design could present richer evidence on the relation between psychosocial development, engagement, and achievement (Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2013).

6 Conclusion

This study analysed the mediating role of adolescent students’ psychosocial development in the engagement–achievement relation. Besides deepening this relation and the role of the different dimensions of student engagement, the study provided evidence regarding the association of psychosocial development and school achievement and the mediating role of industry and identity. Two ideas echoed from these findings. The first is the value of Erikson’s theoretical stages for adolescent students’ engagement and achievement. It points out the need for a comprehensive and integrated theory of human development that may fruitfully guide educators’ awareness and action. Second, considering the time and experiences students live in school, there is a need to improve the match between adolescents’ psychosocial developmental needs and school settings, priorities, pedagogical options, relations, and opportunities. In summary, integrating psychosocial development into educational practices can enhance student engagement and achievement, providing a more supportive and effective learning environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Microsoft Portugal for the technical support in collecting the data, Laurent Mendy for the support during the collection process, Rita Fonseca for the support in revising the text, and Stone Soup Consulting for acknowledging the value of this research.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by National Funds through FCT-Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the scope of UIDEF – Unidade de Investigação e Desenvolvimento em Educação e Formação, UIDB/04107/2020, https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04107/2020. This work was also supported by the European Regional Development Fund the FEDER Program of Castilla-La Mancha for the period 2021–2027, 85% co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, action 01A/008, project 2022-GRIN-34452.

-

Author contributions: N.A.C. and F.H.V. collaborated in the planning, study design, and data collection, as well as the presentation of the initial text of the introduction and discussion. F.H.V., N.A.C., and C.M.V. contributed to the description, analysis, and interpretation of the results and the responses to the reviewers. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results, participated in the writing and revising of the final text, read and approved the final manuscript, and accepted responsibility for its content. All authors agree to the submission of the manuscript to the Open Education Studies.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval and consent: This study has the ethical approval from the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Education of the University of Lisbon. Active parental consent and student assent were acquired from all participants.

-

Data availability statement: The data used in this study are not publicly available due to institutional and national ethical specifications. Nevertheless, data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Short Version of the EPSI Scale

| Stages | Original items and their translation |

|---|---|

| Trust | I think the world and people in it are basically good |

| [Acredito que o mundo é bom] | |

| People are out to get me* | |

| [Sinto que as pessoas querem tramar-me] | |

| I trust people | |

| [Confio nas pessoas] | |

| Autonomy | I cannot make sense of my life* |

| [Duvido que consiga dar sentido à minha vida] | |

| I am ashamed of myself* [Sinto vergonha de mim*] | |

| I do not feel confident of my judgment* [Sinto-me inseguro(a) em relação às minhas opiniões*] | |

| Initiative | I like finding out about new things or places |

| [Gosto de descobrir coisas que desconhecia] | |

| I like new adventures | |

| [Gosto de aprender coisas novas] | |

| I am able to be first with new ideas | |

| [Sou capaz de ser o primeiro a apresentar ideias novas] | |

| Industry | l’m a hard worker |

| [Sou bastante trabalhador(a)] | |

| I do not enjoy working | |

| [Trabalhar é uma seca*] | |

| I’m trying hard to achieve my goals | |

| [Esforço-me muito para atingir os meus objetivos] | |

| Identity | I’ve got a clear idea of what I want to be |

| [Sei bem a pessoa que quero ser] | |

| I know what kind of person I am | |

| [Sei o tipo de pessoa que sou] | |

| The important things in life are clear to me | |

| [Sei o que é importante na vida] |

Notes: *Indicates reverse-coded items.

References

Almroth, M., László, K. D., Kosidou, K., & Galanti, M. R. (2020). Individual and familial factors predict formation and improvement of adolescents’ academic expectations: A longitudinal study in Sweden. PLOS ONE, 15(2), e0229505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229505.Search in Google Scholar

Arbuckle, J. L. (2020). IBM® SPSS® AmosTM 25 User’s Guide. Crawfordville, FL: IBM SPSS. https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB_27.0.0/pdf/amos/IBM_SPSS_Amos_User_Guide.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Bakadorova, O., & Raufelder, D. (2019). The relationship of school self-concept, goal orientations and achievement during adolescence. Self and Identity, 19(2), 235–249. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2019.1581082.Search in Google Scholar

Batra, S. (2013). The psychosocial development of children: Implications for education and society – Erik Erikson in context. Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10(2), 249–278. doi: 10.1177/0973184913485014.Search in Google Scholar

Beck, M., & Wiium, N. (2019). Promoting academic achievement within a positive youth development framework. Norsk Epidemiologi, 28(1–2), 79–87. doi: 10.5324/nje.v28i1-2.3054.Search in Google Scholar

Behr, A., & Fugger, G. (2020). PISA performance of natives and immigrants: Selection versus efficiency. Open Education Studies, 2(1), 9–36. doi: 10.1515/edu-2020-0108.Search in Google Scholar

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238.Search in Google Scholar

Binning, K. R., Cook, J. E., Purdie-Greenaway, V., Garcia, J., Chen, S., Apfel, N., … Cohen, G. L. (2019). Bolstering trust and reducing discipline incidents at a diverse middle school: How self-affirmation affects behavioral conduct during the transition to adolescence. Journal of School Psychology, 75, 74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.07.007.Search in Google Scholar

Bogaerts, A., Claes, L., Buelens, T., Verschueren, M., Palmeroni, N., Bastiaens, T., & Luyckx, K. (2021). Identity synthesis and confusion in early to late adolescents: Age trends, gender differences, and associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 87(1), 106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.01.006.Search in Google Scholar

Borman, G. D., Grigg, J., Rozek, C. S., Hanselman, P., & Dewey, N. A. (2018). Self-affirmation effects are produced by school context, student engagement with the intervention, and time: Lessons from a district-wide implementation. Psychological Science, 29(11), 1773–1784. doi: 10.1177/0956797618784016.Search in Google Scholar

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Testing Structural Equation Models, 21(2), 136–162.10.1177/0049124192021002005Search in Google Scholar

Cabral, J., & Matos, P. M. (2010). Preditores da adaptação à universidade: O papel da vinculação, desenvolvimento psicossocial e coping. Psychologica, 52(1), 55–77. doi: 10.14195/1647-8606_52-1_4.Search in Google Scholar

Cadime, I., Pinto, A. M., Lima, S., Rego, S., Pereira, J., & Ribeiro, I. (2016). Well-being and academic achievement in secondary school pupils: The unique effects of burnout and engagement. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.10.003.Search in Google Scholar

Caraballo, L. (2019). Being “Loud”: Identities-in-practice in a figured world of achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 56(4), 1281–1317. doi: 10.3102/0002831218816059.Search in Google Scholar

Carvalho, N. A., & Veiga, F. H. (2022). Psychosocial development research in adolescence: A scoping review. Trends in Psychology, 30, 640–669. doi: 10.1007/s43076-022-00143-0.Search in Google Scholar

Carvalho, N. A., & Veiga, F. H. (2023). Studies on student engagement in adolescence: A scoping review. Psicologia, 37(2), 62–79. doi: 10.17575/psicologia.1869.Search in Google Scholar

Chase, P. A., Hilliard, L. J., John Geldhof, G., Warren, D. J. A., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Academic achievement in the high school years: The changing role of school engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 884–896. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0085-4.Search in Google Scholar

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organisational Research Methods, 11(2), 296–325. doi: 10.1177/1094428107300343.Search in Google Scholar

Cross, T. L., & Cross, J. R. (2017). Maximising potential: A school-based conception of psychosocial development. High Ability Studies, 28(1), 43–58. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2017.1292896.Search in Google Scholar

Debrosse, R., Rossignac-Milon, M., Taylor, D. M., & Destin, M. (2018). Can identity conflicts impede the success of ethnic minority students? Consequences of discrepancies between ethnic and ideal selves. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(12), 1725–1738. doi: 10.1177/0146167218777997.Search in Google Scholar

Demirci, İ. (2020). School engagement and well-being in adolescents: Mediating roles of hope and social competence. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1573–1595. doi: 10.1007/s12187-020-09722-y.Search in Google Scholar

Dixson, D. D. (2021). Is grit worth the investment? How grit compares to other psychosocial factors in predicting achievement. Current Psychology, 40(7), 3166–3173. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00246-5.Search in Google Scholar

Dixson, D. D., Roberson, C. C. B., & Worrell, F. C. (2017). Psychosocial keys to African American achievement? Examining the relationship between achievement and psychosocial variables in high achieving African Americans. Journal of Advanced Academics, 28(2), 120–140. doi: 10.1177/1932202X17701734.Search in Google Scholar

Dunkel, C. S., & Harbke, C. (2017). A Review of measures of Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development: Evidence for a general factor. Journal of Adult Development, 24(1), 58–76. doi: 10.1007/s10804-016-9247-4.Search in Google Scholar

Erikson, E. H. (1994). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: Norton. (Trabalho original publicado 1968).Search in Google Scholar

Erikson, E. H., & Erikson, J. M. (1998). The life cycle completed (Extended version). New York: W.W. Norton.Search in Google Scholar

Estévez, I., Rodríguez-Llorente, C., Piñeiro, I., González-Suárez, R., & Valle, A. (2021). School engagement, academic achievement, and self-regulated learning. Sustainability, 13(6), 3011. doi: 10.3390/su13063011.Search in Google Scholar

Fairlamb, S. (2022). We need to talk about self-esteem: The effect of contingent self-worth on student achievement and well-being. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 8(1), 45–57. doi: 10.1037/stl0000205.Search in Google Scholar

Fernández-Lasarte, O., Goñi, E., Camino, I., & Zubeldia, M. (2018). Ajuste escolar y autoconcepto académico en la Educación Secundaria. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 37(1), 163–179. doi: 10.6018/rie.37.1.308651.Search in Google Scholar

Finn, J. D., & Zimmer, K. S. (2012). Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 97–131). Boston, MA: Springer US. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_5.Search in Google Scholar

Flum, H., & Kaplan, A. (2012). Identity formation in educational settings: A contextualised view of theory and research in practice. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37(3), 240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2012.01.003.Search in Google Scholar

Fung, F., Tan, C. Y., & Chen, G. (2018). Student engagement and mathematics achievement: Unraveling main and interactive effects. Psychology in the Schools, 55(7), 815–831. doi: 10.1002/pits.22139.Search in Google Scholar

García-Martínez, I., Augusto-Landa, J. M., Quijano-López, R., & León, S. P. (2022). Self-concept as a mediator of the relation between university students’ resilience and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 747168. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.747168.Search in Google Scholar

Gasparotto, G. D. S., Szeremeta, T. D. P., Vagetti, G. C., Stoltz, T., & Oliveira, V. D. (2018). O autoconceito de estudantes de ensino médio e sua relação com desempenho acadêmico: Uma revisão sistemática. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, 31(1), 21. doi: 10.21814/rpe.13013.Search in Google Scholar

Grbić, S., & Maksić, S. (2022). Adolescent identity at school: Student self-positioning in narratives concerning their everyday school experiences. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 35(1), 295–317. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2020.1816235.Search in Google Scholar

Hafen, C. A., Allen, J. P., Mikami, A. Y., Gregory, A., Hamre, B., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). The pivotal role of adolescent autonomy in secondary school classrooms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(3), 245–255. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9739-2.Search in Google Scholar

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, B. (Eds.). (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.Search in Google Scholar

Hamman, D., & Hendricks, C. B. (2005). The role of the generations in identity formation: Erikson speaks to teachers of adolescents. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 79(2), 72–75. doi: 10.3200/TCHS.79.2.72-76.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118.Search in Google Scholar

ITC. (2017). The ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests (2nd ed.). Hemel Hempstead: International Test Commission. www.InTestCom.org.Search in Google Scholar

Kleine, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lam, S., Jimerson, S., Wong, B. P. H., Kikas, E., Shin, H., Veiga, F. H., … Zollneritsch, J. (2014). Understanding and measuring student engagement in school: The results of an international study from 12 countries. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(2), 213–232. doi: 10.1037/spq0000057.Search in Google Scholar

Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Zhou, W. (2018). Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(3), 517–528. doi: 10.2224/sbp.7054.Search in Google Scholar

Lemos, M. S., Gonçalves, T., & Cadima, J. (2020). Examining differential trajectories of engagement over the transition to secondary school: The role of perceived control. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(4), 313–324. doi: 10.1177/0165025419881743.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Y. (2018). Teacher–student relationships, student engagement, and academic achievement for non-latino and latino youth. Adolescent Research Review, 3(4), 375–424. doi: 10.1007/s40894-017-0069-9.Search in Google Scholar

MacCallum, R. C. (1995). Model specification: Procedures, strategies, and related issues. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 16–36). London: SAGE Publications, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

MacCallum, R. C., & Austin, J. T. (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 201–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201.Search in Google Scholar

Mahama, I., Asamoah-Gyimah, K., & Dramanu, B. Y. (2024). Examining the interrelationships among curiosity, creativity, and academic motivation using students in high schools: A multivariate analysis approach. Open Education Studies, 6(1), 20240001. doi: 10.1515/edu-2024-0001.Search in Google Scholar

Mameli, C., & Passini, S. (2017). Measuring four-dimensional engagement in school: A validation of the student engagement scale and of the agentic engagement scale. TPM – Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 24, 527–541. doi: 10.4473/TPM24.4.4.Search in Google Scholar

Manrique Millones, D. L., Ghesquière, P., & Van Leeuwen, K. (2014). Relationship among parenting behavior, SES, academic achievement and psychosocial functioning in Peruvian children. Universitas Psychologica, 13(2), 639–650. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-2.rpba.Search in Google Scholar

Martínez, I., Oliveira, I. M., Murgui, S., & Veiga, F. H. (2024). Family and school influences on individuals’ early and later adjustment. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1437320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1437320.Search in Google Scholar

Marttinen, E., Dietrich, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2018). Intentional engagement in the transition to adulthood: An integrative perspective on identity, career, and goal developmental regulation. European Psychologist, 23(4), 311–323. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000337.Search in Google Scholar

Negru‐Subtirica, O., Damian, L. E., Pop, E. I., & Crocetti, E. (2023). The complex story of educational identity in adolescence: Longitudinal relations with academic achievement and perfectionism. Journal of Personality, 91(2), 299–313. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12720.Search in Google Scholar

Newman, B. M., & Newman, P. R. (2015). Development through life: A psychosocial approach (12th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.Search in Google Scholar

Olivier, E., Archambault, I., De Clercq, M., & Galand, B. (2019). Student self-efficacy, classroom engagement, and academic achievement: Comparing three theoretical frameworks. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(2), 326–340. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0952-0.Search in Google Scholar

Patton, G. C., Sawyer, S. M., Santelli, J. S., Ross, D. A., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B., … Viner, R. M. (2016). Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet, 387(10036), 2423–2478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1.Search in Google Scholar

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.Search in Google Scholar

Qahri-Saremi, H., & Turel, O. (2016). School engagement, information technology use, and educational development: An empirical investigation of adolescents. Computers & Education, 102, 65–78. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.07.004.Search in Google Scholar

Ramos-Díaz, E., Rodríguez-Fernández, A., & Revuelta, L. (2016). Validation of the Spanish version of the school engagement measure (SEM). The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 19, E86. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2016.94.Search in Google Scholar

Reeve, J., Cheon, S. H., & Jang, H. (2020). How and why students make academic progress: Reconceptualising the student engagement construct to increase its explanatory power. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 62, 101899. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101899.Search in Google Scholar

Roeser, R. W., Peck, S. C., & Nasir, N. S. (2006). Self and identity processes in school motivation, learning, and achievement. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 391–424). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

Rosenthal, D. A., Gurney, R. M., & Moore, S. M. (1981). From trust on intimacy: A new inventory for examining Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10(6), 525–537. doi: 10.1007/BF02087944.Search in Google Scholar

Salmela‐Aro, K., Tang, X., Symonds, J., & Upadyaya, K. (2021). Student engagement in adolescence: A scoping review of longitudinal studies 2010–2020. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(2), 256–272. doi: 10.1111/jora.12619.Search in Google Scholar

Salmela-Aro, K., Tang, X., & Upadyaya, K. (2022). Study demands-resources model of student engagement and burnout. In A. L. Reschly & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 77–93). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-031-07853-8_4 Search in Google Scholar

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research – Online, 8(2), 23–74.Search in Google Scholar

Schotte, K., Stanat, P., & Edele, A. (2018). Is integration always most adaptive? The role of cultural identity in academic achievement and in psychological adaptation of immigrant students in Germany. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(1), 16–37. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0737-x.Search in Google Scholar

Shernoff, D. J. (2013). Engagement as an individual trait and its relationship to achievement. In Optimal learning environments to promote student engagement (pp. 97–126). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7089-2.Search in Google Scholar

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, M. L., Mann, M. J., & Kristjansson, A. L. (2020). School climate, developmental support, and adolescent identity formation. Journal of Behavioral & Social Sciences, 7(3), 255–268.Search in Google Scholar

Storlie, C. A., & Toomey, R. B. (2020). Facets of career development in a new immigrant destination: Exploring the associations among school climate, belief in self, school engagement, and academic achievement. Journal of Career Development, 47(1), 44–58. doi: 10.1177/0894845319828541.Search in Google Scholar

Tao, Y., Meng, Y., Gao, Z., & Yang, X. (2022). Perceived teacher support, student engagement, and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology, 42(4), 401–420. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2022.2033168.Search in Google Scholar

Tomás, J. M., Gutiérrez, M., Georgieva, S., & Hernández, M. (2020). The effects of self‐efficacy, hope, and engagement on the academic achievement of secondary education in the Dominican Republic. Psychology in the Schools, 57(2), 191–203. doi: 10.1002/pits.22321.Search in Google Scholar

Tomaszewski, W., Xiang, N., & Western, M. (2020). Student engagement as a mediator of the effects of socio‐economic status on academic performance among secondary school students in Australia. British Educational Research Journal, 46(3), 610–630. doi: 10.1002/berj.3599.Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. (2016). Education 2030—Incheon declaration and framework for action for the implementation of sustainable development goal 4. Paris: Unesco Education Sector. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656.Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. (2019). Right to education handbook. Paris: Unesco Education Sector.Search in Google Scholar

Upadyaya, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Development of school engagement in association with academic success and well-being in varying social contexts: A review of empirical research. European Psychologist, 18(2), 136–147. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000143.Search in Google Scholar

Veiga, F. H. (2002). Psicologia da educação: Relatório da disciplina [Educational Psychology: Course Report] [Provas de Agregação em Educação, Departamento de educação da Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa]. https://repositorio.ul.pt/handle/10451/6238.Search in Google Scholar

Veiga, F. H. (2016). Assessing student engagement in school: Development and validation of a four-dimensional scale. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 217, 813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.02.153.Search in Google Scholar

Veiga, F. H., Festas, I., García, Ó. F., Oliveira, Í. M., Veiga, C. M., Martins, C., … Carvalho, N. A. (2021). Do students with immigrant and native parents perceive themselves as equally engaged in school during adolescence? Current Psychology, 42, 11902–11916. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02480-2.Search in Google Scholar

Veiga, F. H., García, F., Reeve, J., Wentzel, K., & Garcia, O. (2015). When adolescents with high self-concept lose their engagement in school. Revista de Psicodidactica, 20(2), 305–320. doi: 10.1387/RevPsicodidact.12671.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, M. T., Degol, J. L., & Henry, D. A. (2019). An integrative development-in-sociocultural-context model for children’s engagement in learning. American Psychologist, 74(9), 1086–1102. doi: 10.1037/amp0000522.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 28, 12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

Widlund, A., Tuominen, H., & Korhonen, J. (2021). Development of school engagement and burnout across lower and upper secondary education: Trajectory profiles and educational outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 66, 101997. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.101997.Search in Google Scholar

Yeager, D. S., Lee, H. Y., & Dahl, R. E. (2018). Competence and motivation during adolescence. In A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, & D. S. Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (2nd ed., pp. 431–448). New York: Guilford Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Disruptive Innovations in Education - Part II

- Formation of STEM Competencies of Future Teachers: Kazakhstani Experience

- Technology Experiences in Initial Teacher Education: A Systematic Review

- Ethnosocial-Based Differentiated Digital Learning Model to Enhance Nationalistic Insight

- Delimiting the Future in the Relationship Between AI and Photographic Pedagogy

- Research Articles

- Examining the Link: Resilience Interventions and Creativity Enhancement among Undergraduate Students

- The Use of Simulation in Self-Perception of Learning in Occupational Therapy Students

- Factors Influencing the Usage of Interactive Action Technologies in Mathematics Education: Insights from Hungarian Teachers’ ICT Usage Patterns

- Study on the Effect of Self-Monitoring Tasks on Improving Pronunciation of Foreign Learners of Korean in Blended Courses

- The Effect of the Flipped Classroom on Students’ Soft Skill Development: Quasi-Experimental Study

- The Impact of Perfectionism, Self-Efficacy, Academic Stress, and Workload on Academic Fatigue and Learning Achievement: Indonesian Perspectives

- Revealing the Power of Minds Online: Validating Instruments for Reflective Thinking, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Regulated Learning

- Culturing Participatory Culture to Promote Gen-Z EFL Learners’ Reading Proficiency: A New Horizon of TBRT with Web 2.0 Tools in Tertiary Level Education

- The Role of Meaningful Work, Work Engagement, and Strength Use in Enhancing Teachers’ Job Performance: A Case of Indonesian Teachers

- Goal Orientation and Interpersonal Relationships as Success Factors of Group Work

- A Study on the Cognition and Behaviour of Indonesian Academic Staff Towards the Concept of The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

- The Role of Language in Shaping Communication Culture Among Students: A Comparative Study of Kazakh and Kyrgyz University Students

- Lecturer Support, Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, and Statistics Anxiety in Undergraduate Students

- Parental Involvement as an Antidote to Student Dropout in Higher Education: Students’ Perceptions of Dropout Risk

- Enhancing Translation Skills among Moroccan Students at Cadi Ayyad University: Addressing Challenges Through Cooperative Work Procedures

- Socio-Professional Self-Determination of Students: Development of Innovative Approaches

- Exploring Poly-Universe in Teacher Education: Examples from STEAM Curricular Areas and Competences Developed

- Understanding the Factors Influencing the Number of Extracurricular Clubs in American High Schools

- Student Engagement and Academic Achievement in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Psychosocial Development

- The Effects of Parental Involvement toward Pancasila Realization on Students and the Use of School Effectiveness as Mediator

- A Group Counseling Program Based on Cognitive-Behavioral Theory: Enhancing Self-Efficacy and Reducing Pessimism in Academically Challenged High School Students

- A Significant Reducing Misconception on Newton’s Law Under Purposive Scaffolding and Problem-Based Misconception Supported Modeling Instruction

- Product Ideation in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Insights on Design Process Through Shape Coding Social Robots

- Navigating the Intersection of Teachers’ Beliefs, Challenges, and Pedagogical Practices in EMI Contexts in Thailand

- Business Incubation Platform to Increase Student Motivation in Creative Products and Entrepreneurship Courses in Vocational High Schools

- On the Use of Large Language Models for Improving Student and Staff Experience in Higher Education

- Coping Mechanisms Among High School Students With Divorced Parents and Their Impact on Learning Motivation

- Twenty-First Century Learning Technology Innovation: Teachers’ Perceptions of Gamification in Science Education in Elementary Schools

- Exploring Sociological Themes in Open Educational Resources: A Critical Pedagogy Perspective

- Teachers’ Emotions in Minority Primary Schools: The Role of Power and Status

- Investigating the Factors Influencing Teachers’ Intention to Use Chatbots in Primary Education in Greece

- Working Memory Dimensions and Their Interactions: A Structural Equation Analysis in Saudi Higher Education

- Review Articles

- Current Trends in Augmented Reality to Improve Senior High School Students’ Skills in Education 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review

- Exploring the Relationship Between Social–Emotional Learning and Cyberbullying: A Comprehensive Narrative Review

- Determining the Challenges and Future Opportunities in Vocational Education and Training in the UAE: A Systematic Literature Review

- Socially Interactive Approaches and Digital Technologies in Art Education: Developing Creative Thinking in Students During Art Classes

- Current Trends Virtual Reality to Enhance Skill Acquisition in Physical Education in Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century: A Systematic Review

- Case Study

- Contrasting Images of Private Universities

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Disruptive Innovations in Education - Part II

- Formation of STEM Competencies of Future Teachers: Kazakhstani Experience

- Technology Experiences in Initial Teacher Education: A Systematic Review

- Ethnosocial-Based Differentiated Digital Learning Model to Enhance Nationalistic Insight

- Delimiting the Future in the Relationship Between AI and Photographic Pedagogy

- Research Articles

- Examining the Link: Resilience Interventions and Creativity Enhancement among Undergraduate Students

- The Use of Simulation in Self-Perception of Learning in Occupational Therapy Students

- Factors Influencing the Usage of Interactive Action Technologies in Mathematics Education: Insights from Hungarian Teachers’ ICT Usage Patterns

- Study on the Effect of Self-Monitoring Tasks on Improving Pronunciation of Foreign Learners of Korean in Blended Courses

- The Effect of the Flipped Classroom on Students’ Soft Skill Development: Quasi-Experimental Study

- The Impact of Perfectionism, Self-Efficacy, Academic Stress, and Workload on Academic Fatigue and Learning Achievement: Indonesian Perspectives

- Revealing the Power of Minds Online: Validating Instruments for Reflective Thinking, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Regulated Learning

- Culturing Participatory Culture to Promote Gen-Z EFL Learners’ Reading Proficiency: A New Horizon of TBRT with Web 2.0 Tools in Tertiary Level Education

- The Role of Meaningful Work, Work Engagement, and Strength Use in Enhancing Teachers’ Job Performance: A Case of Indonesian Teachers

- Goal Orientation and Interpersonal Relationships as Success Factors of Group Work