Abstract

A multi-level perspective of how environmental regulations affect firm performance receives less attention. By document analysis and semi-structured interviews, this study examines the influences of environmental regulations from the central government, the local governments, and the corporate on firm performance with a case study based on a state-owned enterprise named SINOPEC Yangzi Petrochemical Company (SYPC) in China. The findings show that the regulations from different levels exert distinct but interconnected influences on performance of SYPC. The guiding concepts from the central government, the prescriptive standards from the local governments, and the performance management systems from the SINOPEC headquarters incentivize SYPC to innovate green technology. Technical upgrade, good relations with the government, and popularity in the public due to the implementation of regulations improve economic performance of SYPC, though which is not the priority of the company. SYPC actively implements environmental policies but also acts as a part of the strategy of SINOPEC circumventing regulations.

1 Introduction

The influence of environmental regulations on firm performance is an enduring hot topic. Theoretically, views from neo-classic environmental economics deem that regulations negatively affect firm productivity and competitiveness (Gray & Shadbegian, 2003; Sari & Tjen, 2017). But the more popular perspective is that regulations benefit firm performance. The widely-cited Porter hypothesis (PH) suggests that regulations motivate technological innovation that improves economic performance of corporates (Porter & Van der Linde, 1995). There are “weak,” “narrow,” and “strong” versions of the PH indicating that stringent policies such as prescriptive emission standards have different effects with flexible measures like economic instruments (Arimura et al., 2007; Jaffe & Palmer, 1997). Extensive empirical studies have tried to verify the three versions of the PH but come to mixed conclusions due to the heterogeneity of corporates and sectors (Lanoie et al., 2011; Testa et al., 2011; Wang & Shen, 2016).

As the world factory, environmental pollution is one of the most critical problems of China (Liu & Lin, 2019; Zhang, 2007). The total amount of CO2 emissions from China in 2020 was 10.67 billion metric tons, ranking first in the world. However, China has built one of the strictest environmental regulation systems in the world, urging corporates to renovate products and producing patterns with greener characteristics. The system has a multi-level structure in which the central and local governments and corporates all make regulations that affect innovation and performance of corporates. Nonetheless, there are few studies considering such effects from a multi-level perspective.

Environmental regulations play a vital role in shaping the business landscape, especially in a country like China with a significant industrial footprint. This study aims to explore the practical implications of environmental regulations on a leading petrochemical company’s economic performance in China, shedding light on the complex interplay between regulations and business outcomes. A case study focusing on a leading corporate in the petrochemical industry named SINOPEC Yangzi Petrochemical Company (SYPC) is used. SYPC is a holding subsidiary of the central state-owned company SINOPEC (China Petrochemical Corporation) that is among the top energy firms in the world. The contributions of this study are, first, bringing forward the underresearched multi-level perspective. Most studies examine the influences of different types of regulations on various corporates and sectors, while the institutional contexts these subjects are embedded in are largely ignored. Regulations from different policy makers usually have different focuses and affect each other. The case in this article reveals that the regulations from central and local governments and the SINOPEC headquarters have distinct but also interconnected effects on technological innovation and economic performance of SYPC. Second, this study contributes to the debate on how state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are affected by environmental regulations. The chemical industry in China is dominated by several giant central SOEs. The role of SOEs is complicated as they are entitled with more environmental responsibilities but also have easier access to government resources that help them adapt to or circumvent regulations (Shah et al., 2021; Shi & Xu, 2018). SYPC in this study actively implements environmental regulations by conducting a green mode of production, but it is also a part of the SINOEPC’s strategic circumvention of government policies. Third, this study enriches the understanding of the PH in the Chinese context. The three versions of the PH appear to evaluate the effects of stringent policies and flexible instruments separately. The “narrow” version suggests that flexible instruments better incentivize corporates to innovate than stringent policies because there is “more space” for the manager to identify feasible abatement opportunities (Arimura et al., 2007). This study supports the hypothesis as the performance management systems designed by the SINOPEC headquarters give extra incentives for innovation. But such systems are used to first guarantee the prescriptive standards in the multi-level regulations to be fulfilled and then encourage more innovation. The greater motivation from flexible instruments is built on the pressure under stringent policies, and thus, the effects of the two types of regulations are intertwined rather than independent.

This study relies on document analysis and semi-structured interviews with the staff in SYPC. Documents include government and company policy files about regulation measures from the central and local governments and SINOPEC headquarters, as well as reports from SYPC about environmental behaviours and economic performance. The study reveals that regulations at various levels uniquely impact SYPC’s performance yet are interlinked. Central government guidance, local government standards, and SINOPEC’s performance systems collectively encourage SYPC to innovate in green technology. SYPC’s focus on technical advancements, positive governmental relations, and public support due to regulatory compliance enhance its economic performance, although economic gains are not the primary focus for the company. Due to data availability, this study selects net profits as the indicator of economic performance. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with five managers in SYPC from September 2020 to August 2021. The rest of the study is as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature about the influences of environmental regulations on firm performance, emphasizes the multi-level structure of the regulation system, and highlights the context of China. Section 3 introduces SYPC and the analytical framework of the study. Section 4 examines how the environmental regulations at multiple levels affect SYPC. The summary, theoretical dialogues, and future research agenda conclude the study.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Environment Regulations and Firm Performance

The existing literature presents divergent views on how environmental regulations affect business performance. Factors influencing firm performance span various domains, including economic conditions, government policies, social impacts, technological advancements, and market dynamics. Research across multiple studies, such as those referenced, has highlighted the intricate interplay of these factors on firms. Economic stability or downturns directly affect consumer spending, impacting firms’ revenue streams, including the economic activities in the supply chain. Government policies wield substantial influence, from taxation structures to trade agreements, altering operational costs and market access. Social factors, including changing demographics or cultural shifts, mold consumer preferences and market demands, crucial to firms’ strategic planning (Ghaedamini Harouni et al., 2023; Ghanbari et al., 2022; Taşkan & Karatop, 2022).

However, amidst this multifaceted landscape, environmental regulations emerge as the foremost influential factor for firms. Environmental policies, often stringent and evolving, wield profound impacts across industries. Stringent regulations compel firms to innovate and adopt sustainable practices, impacting production processes, resource allocation, and compliance costs. Firms navigating these regulations face heightened pressures to reduce carbon footprints, adopt eco-friendly technologies, and ensure responsible resource usage. Such endeavors significantly affect operational expenses and supply chain dynamics, altering the competitive landscape.

Moreover, the significance of environmental regulations stems from their pervasive nature, transcending borders and industries. Global efforts toward environmental sustainability, exemplified by initiatives like the Paris Agreement, amplify the regulatory impact on firms worldwide. Compliance with these regulations is not merely a legal necessity; it is increasingly intertwined with brand image, consumer perceptions, and market competitiveness. Firms embracing sustainability tend to garner favor among environmentally conscious consumers and investors, thereby influencing market positioning and long-term viability.

Furthermore, environmental regulations catalyze innovation and drive technological advancements. Firms invest in research and development to create eco-friendly products and processes, fostering a culture of innovation that can yield competitive advantages beyond regulatory compliance. Collaboration and partnerships become instrumental in navigating these regulations, fostering industry-wide efforts toward sustainability.

In essence, while economic, governmental, social, and technological factors exert significant influence on firms, environmental regulations stand out as the most impactful. The gravity of these regulations transcends mere compliance; they redefine operational paradigms, shape market behaviours, and dictate firms’ long-term sustainability strategies. Embracing environmentally conscious practices is not just a legal obligation; it is a strategic imperative for firms seeking resilience, innovation, and enduring relevance in a rapidly evolving global landscape.

Traditional neo-classical environmental economics suggests that regulations tend to impose additional costs, such as emission taxes and investments in green technologies, which can negatively impact corporate profitability (Sari & Tjen, 2017; Yuan & Xiang, 2018). These costs can act as deterrents to investments in production and other activities, ultimately undermining business performance. On the contrary, proponents of the PH argue that regulations serve as drivers of positive change. By obliging corporations to innovate technologically and adapt their production methods, regulations can lead to increased efficiency and the development of new products, potentially offsetting compliance costs (Mohr, 2002; Mohr & Saha, 2008).

Different types of regulations play a crucial role in shaping the outcomes. The “weak” version of the PH suggests that stringent policies encourage specific types of innovation (Jaffe & Palmer, 1997). Stringency often manifests as specific indicators like direct emission standards imposed on corporations. The “narrow” version posits that flexible regulations, such as tradable emission permits, offer greater incentives for innovation by providing “room” for identifying feasible abatement opportunities (Arimura et al., 2007). Finally, the “strong” version contends that well-designed regulations, combining stringency and flexibility, can stimulate innovation that generates returns surpassing compliance costs, thereby enhancing corporate economic performance (Lanoie et al., 2011).

However, empirical research attempting to validate these hypotheses has yielded diverse findings. For instance, Testa, Iraldo, and Frey’s analysis of the building and construction sector in certain European Union (EU) regions suggests that well-structured direct regulations effectively promote innovation and economic performance, while economic instruments have a negative impact on business indicators (Testa et al., 2011). Lanoie et al.’s study across manufacturing industries in seven OECD countries provides support for the “weak” version, limited support for the “narrow” version, and does not endorse the “strong” version (Lanoie et al., 2011). Zhao et al.’s research on China’s major environmental regulations and their effects on energy firms’ stock prices reveals mixed outcomes, depending on the category of the regulation (Zhao et al., 2018).

2.2 The Influences of Environmental Regulations from a Multi-Level Perspective

Besides the types of regulations, the heterogeneity on firms, industries and institutions also alter the influences of regulations on corporates’ innovation and performance. Some studies emphasize the importance of both organizational and sectoral characteristics (DeCanio, 1998; DeCanio et al., 2000). Organizational structure, management practice, and personal values of the managers significantly affect the decision-making of a corporate under environmental regulations (Arimura et al., 2007). The same regulatory practice may exert distinct influences on different sectors due to the varied uses of raw materials and processes of production (Yuan et al., 2017). Wang and Shen find that environmental regulations in China positively affect clean production industries, but such effects are lagged on pollution-intensive industries (Wang & Shen, 2016). Rexhäuser and Rammer analyze how environmental regulations in Germany influence profitability of different corporates and conclude that only firms generating both regulation-driven and voluntary innovations on improving producing efficiency can promote their profitability (Rexhäuser & Rammer, 2014).

Compared with organizational and sectoral features, the institutional contexts in which the regulations and corporates are embedded receive less attention. Most of the existing studies categorize environmental regulations according to policy stringency. However, regulations can also be divided by the policy makers with different intentions. The central government needs to consider the regional disparity and comes up with universal guidance applied across the country. The local government considers more about the local specificities and designs local context-based policies to enrich and supplement the central guidance. The United Kingdom has been prioritizing carbon reduction in the last several years and formally committed to realize zero net carbon emission by 2050 in 2019. In this situation, the Mayor’s London Environment Strategy was published with six aspects that London needs to improve before 2050. For every aspect, there were detailed regulation measures and implementation plans. Gibbs and Jonas emphasize that, though environmental policy-making is rescaling from international and national levels to the local level of the state, the making of regulations and their influences should be considered across all government levels (Gibbs & Jonas, 2000).

In some cases, the organizational structure of corporate cannot be discussed separately from the institutional context when there is close connection between the government and corporates. SOEs are common in national strategic industries so that the government can better control the economy. In the OECD countries, SOEs take leading positions in the electricity and gas industries, while the transportation sector is closely monitored by environmental policy makers (Christiansen, 2011). In China, SOEs play an important role in almost all sectors, especially in the heavy industries (Fu et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2017). Compared with private companies, SOEs need to bear more environmental responsibilities and help the government with environmental objectives. Thus, the managers may make decisions that contribute to environmental protection instead of economic benefits (Shah et al., 2021). On the other hand, SOEs receive more preferential treatment from the government that make them adapt to the regulations more efficiently and achieve better performance (Shi & Xu, 2018).

The relations between environmental regulations and firm performance are complicated by types of regulations, sectoral, and organizational features and the multi-level interaction between government at different levels and corporates. Then a case study used by this article that focuses on a specific corporate with first-hand interviews provides opportunities to reveal accurate relations compared with constructing econometric models that may suffer from omitting variables, selection bias, multi-collinearity, and other technical issues. In China, more environmental regulations are stringent rather than flexible. The common situation is that the government publishes specific emission standards and punitive measures including fines, circulated notices of criticism, mandatory rectification, and business shutdown for the corporates that cannot meet the standards (He et al., 2020). In the study by Zhao et al. (2018), it was found that the 20 major environmental regulations consist of 16 legislative and administrative standards, only 2 market-based regulations and 2 environmental information disclosures. This article therefore focuses on the stringent government regulations represented by the prescriptive standards. The environmental regulations in China mainly target at pollution-intensive industries to promote the industrial restructuring and upgrade. This article selects SYPC, the leading SOE in the petroleum industry that actively implements environmental policies. The SINOPEC headquarters pays attention to both stringent policies and flexible instruments as it designs emission standards and performance management systems for subsidiaries. This study focuses on SYPC, a prominent player in the petrochemical industry in China. It examines how SYPC has managed to adapt to stringent environmental regulations while maintaining its economic performance. We recognize that regulations at multiple levels, from central to local governments, can pose challenges for businesses. SYPC’s experience serves as a case study to highlight practical strategies employed by companies to balance environmental responsibilities and economic interests.

2.3 The Context of China

China, as a global industrial powerhouse, faces unique challenges in environmental regulation. The government’s role in SOEs adds complexity to the business landscape. SOEs like SYPC play a crucial role in driving environmental objectives while navigating economic realities. Understanding the political structure and development of SOEs in China is important to analyse the multi-level interaction between government levels and corporates. China’s environmental regulations operate within a multi-level governance framework, where responsibilities are distributed among national, provincial, and local authorities. At the national level, central government bodies like the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) set overarching policies and standards. Provinces then adapt these guidelines to suit regional conditions, often with their own specific regulations. Local governments enforce these regulations and may have additional measures to address local environmental challenges. Meanwhile, to improve efficiency, local governments are entitled with decision-making on but also need to self-finance local economic, social, environmental and cultural affairs (Xu, 2011). To create more fiscal income and higher GDP, local governments may sometimes circumvent or ignore central policies such as acquiescence in the operation of corporates that create considerable economic benefits but emit excessive pollutants.[1] This tiered system allows for flexibility in implementation while ensuring alignment with national environmental objectives.

Central and local SOEs dominate the manufacturing sector in China (Wei et al., 2002). The central/local government holds full, majority of, or significant minority of the shares of SOEs mainly through the central-/local state-owned assets supervision and administration commission (SASAC). The board chairman, chief executives, and managers of SOEs are recommended or directly nominated by SASAC (Lin, 2017). Some large central SOEs usually set their headquarters in Beijing and distribute subsidiaries across the country. Some branch companies have an integrate production system and the decision-making of firm strategies, but they also answer to the headquarters by serving the development goals of group company and following the rules and regulations made by headquarters (Szamosszegi & Kyle, 2011). Although without local SASAC being the shareholder, branches of central SOEs also aim to build good relations with local authority in most cases for a better operating environment as local governments control natural resources in the locality and have profound influences on local markets.

There are extensive studies that examine the influences of environmental regulations on firm performance in China, with SOEs as a popular focus. SOEs are given stricter emission standards by the government because of their exemplar effects (Wang & Wheeler, 2005). They are also pioneers of implementing environmental regulations by using green technology (Cai et al., 2020; Wang & Shen, 2016) compared to firms of other ownerships. Such behaviours may undermine firm performance in particular situations but do not stop the enthusiasm of the managers since realizing government objectives benefit both their personal income and corporate development in the long term (Guo et al., 2017; Jian et al., 2020). Meanwhile, the preferential treatment, particularly the “soft budget control” which means that SOEs are backed by capital and credit of the government, makes these companies better adapt to regulations (Maurel & Pernet, 2021). However, there are also cases that SOEs ignore local environmental regulations. This happens when a branch of large central SOEs has higher administrative levels than the city or county and significantly contributes to local economy (Eaton & Kostka, 2017).

3 Introduction of SYPC and the Analytical Framework

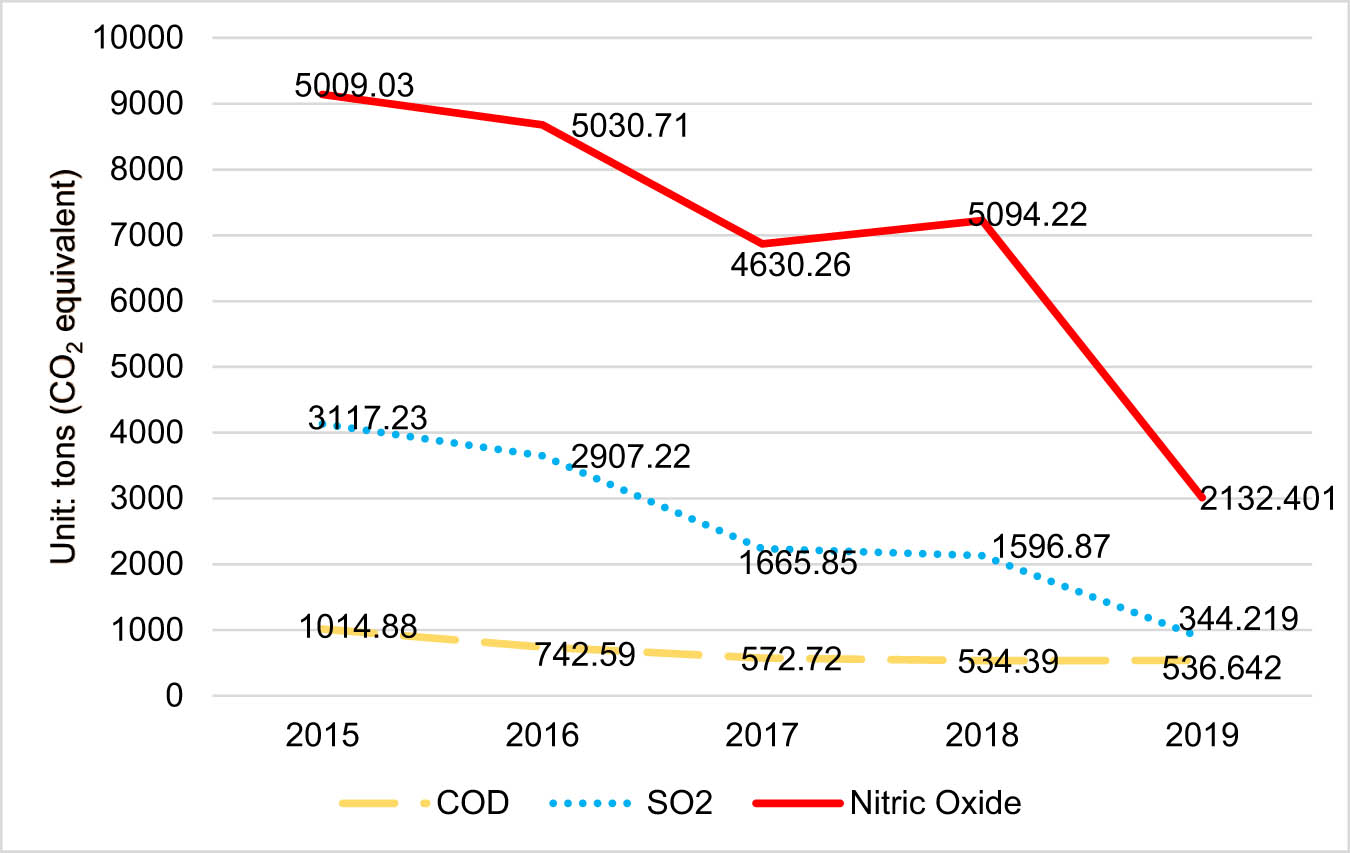

This article centres its attention on SYPC, an SOE based in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, and a subsidiary of SINOPEC, a major player in China’s chemical industry. SINOPEC holds a significant market share, standing at 19% in 2020, making it the industry leader. SYPC is a vital component of SINOPEC’s operations, specializing in the production of petroleum and petrochemical products, which constitute a substantial portion of the group’s profits. Since its establishment in 2006, SYPC has been committed to advancing environmentally sustainable production through technological innovation. In 2014, SYPC initiated the “clean water and clear sky (bi shui lan tian)” project, allocating a substantial budget of 130 million Yuan to promote eco-friendly production. This initiative was further expanded in 2017 with an additional 2.5 billion Yuan investment, aimed at fostering innovation before 2020. Under this project, SYPC ceased the production of conventional gasoline, a highly profitable but environmentally damaging product. Instead, the company successfully introduced more efficient and eco-friendly gasoline types, “SU Ⅴ” and “GUO Ⅵ,” subsequently endorsed by the central government. In addition, SYPC’s catalysts for volatile organic chemicals (VOCs) treatment gained recognition as world-class technology, eliminating the need for China to import similar technology. Through significant investments, SYPC achieved a remarkable reduction in emissions during the late 2010s (Figure 1).

The emission level of major pollutants of SYPC from 2015 to 2019. Source: Annual reports of SYPC, http://ypc.sinopec.com/ypc/csr/enviroment/product_info/.

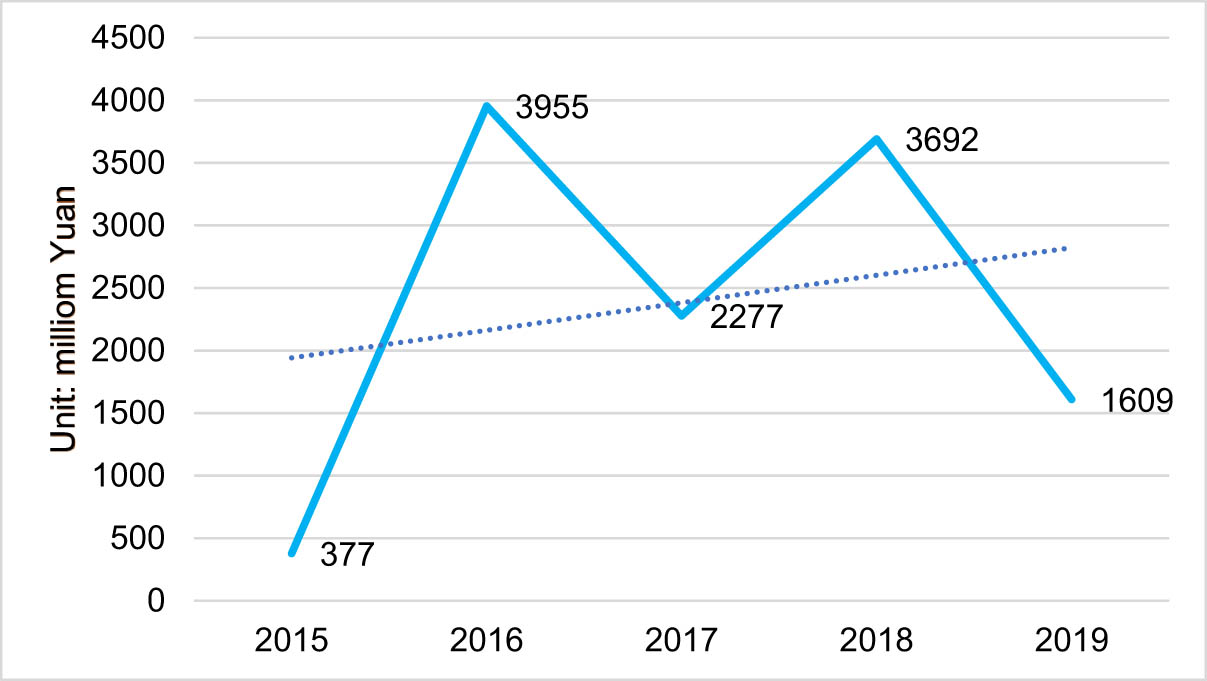

However, SYPC’s economic performance, primarily measured in terms of net profits, does not mirror its technological innovations. While financial data before 2015 remain undisclosed, an interviewee mentioned that SYPC faced consecutive losses during earlier years, only returning to profitability in 2015. In the subsequent 4 years, net profits exhibited fluctuations, consistently remaining below 10% of sales revenue (Figure 2). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that within the SINOPEC group, SYPC maintains a competitive position in terms of net profits.

The net profits of SYPC from 2015 to 2019. Source: Annual reports of SYPC, http://ypc.sinopec.com/ypc/csr/enviroment/product_info/.

SYPC presents a compelling case study for several reasons. First, it operates in the chemical industry, which is subject to stringent environmental regulations in China. Second, these regulations encourage technological innovation, but their influence on economic performance is nuanced. Some interviewees believe that implementing environmental policies can enhance a company’s performance. Finally, SYPC’s status as a subsidiary of a prominent central SOE means that its strategies are shaped by regulations at multiple levels, from both the central and local governments, as well as directives from the SINOPEC headquarters.

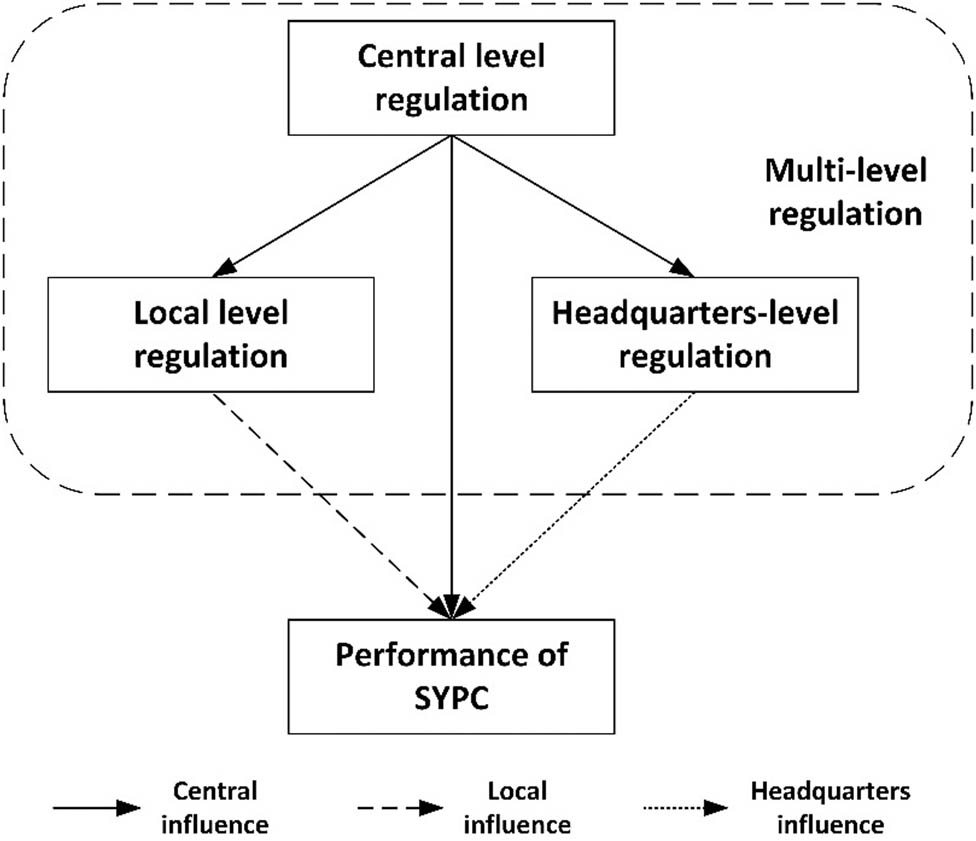

The environmental regulatory framework consists of measures at different levels (central, local, and corporate headquarters), each exerting varying degrees of influence on SYPC’s performance. The interconnectedness of these regulations creates a complex dynamic (Figure 3).

Multi-level environmental regulations and their influences on the performance of SYPC. Source: Compiled by the author.

4 The Influences of Multi-Level Environmental Regulations on Firm Performance

4.1 The Central Level: Guiding Concepts and Detailed Standards

The central government holds primary responsibility for making and enforcing environmental regulations, providing guiding concepts and detailed instructions outlined in the Five-Year Plans (FYPs). The FYPs published by the State Council set the course of national development for every 5 years. Since the 6th FYP in the late 1970s, every plan has mentioned and increasingly highlighted the importance of environmental protection (Kostka & Mol, 2013). In 2011, for the first time in the national congress, the 12th FYP formally proposed green development as a national priority and promoted a strategic transformation toward an eco-friendlier mode of the environmental management. The plan raised a target to reduce CO2 emission per unit GDP by 17% by the end of 2015 compared with that of 2010. To achieve the target, central departments represented by the MEE published dozens of policy documents with nearly 2000 specific standards on environmental activities for local governments and corporates, including pollutant discharge levels measured by individual factory, county, city, and province; monitoring range and frequencies of local governments on corporates; punishing measures for corporates violating regulations, etc.

For the regulations from the central government, one manager of SYPC confirmed their effects on promoting technological innovation.

In 2008, we innovated our technology to carry out the concept of ‘scientific outlook on development (ke xue fa zhan guan)’ and overfulfilled the annual target of the firm on saving water, gas and electricity. In 2012, the company strived to be the leader of ‘ecological civilization (sheng tai wen ming)’ and the builder of ‘Beautiful China (mei li zhong guo)’. A three-level resources recycling system was built to reuse tail gas and waste water. In 2018, we actively implemented the idea ‘lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets (lv shui qing shan jiu shi jin shan yin shan)’ and furthered the existing plans on emission reduction, waste treatment and upgrade on green production procedures.

The concepts mentioned by the manager were raised by the former president Hu Jintao and the current president Xi Jinping and were written in the FYPs in the 2000s and 2010s as guiding ideologies to emphasize environmental protection during promoting economic development. Notably, adherence to central instructions impacts promotions for local officials and central SOE managers, signifying their importance within the regulatory landscape. For the reason, he said:

We met all the standards in 10th, 11th and 12th FYPs. We surely abide by the standards of MEE, but we pay more attention to the regulations from Jiangsu and Nanjing governments and those made by the headquarters. They are at least of the same standard as the central ones. In more cases they are stricter.

Compared with the detailed criteria, guiding concepts of the central government better incentivize SYPC to innovate technology. Such concepts are neither stringent nor flexible instruments and are of Chinese characteristics. They set the direction and leave space for policy executors to come up with specific methods. Though being broad, sometimes obscure, and resulting in unsuccessful implementation, they are valued by the local governments and corporates, particularly SOEs (Kostka & Nahm, 2017). Following the central instructions are key to whether local officials can be promoted to a higher-level position, and whether central SOE managers can be promoted or earn extra income.[2]

4.2 The Local Level: Tailored Policies and Supervision

Local governments modify central regulatory measures or devise new measures to suit local contexts (Heberer & Senz, 2011). Jiangsu and Nanjing governments mainly use two methods to produce local environmental regulations: modifying central regulatory measures and coming up with new measures under central guidelines.

An example for the first method is the modification of the emission standards for the petrochemical industry published by MEE in 2015.[3] MEE designed two sets of maximum concentration levels for water pollutant emission (Table 1). Places with smaller environmental capacity, fragile ecological system and higher level of territory development should follow the stricter set of standards called the ‘special standards’. The decision about which places fell into this category was made by provincial governments after consulting MEE. Based on the MEE standards, Department of Ecology and Environment of Jiangsu (DEEJ) published emission standards for firms in the province (DEEJ, 2020). In the introduction page, the policy document stated that “The document aims to implement the central policies on environmental protection. The standards are made by modifying those in the MEE document with local situations.” MEE stipulated that the concentration levels of chemical oxygen demand (COD) could not exceed 60 mg/L in most cases. The “special standard” was 50 mg/L. The standard for corporates producing epichlorohydrin, naphthalene series compounds, epoxypropane, and six other chemical products was 100 mg/L. With these thresholds, Jiangsu first matched the name of chemicals to specific industries according to the existing industrial structure in the province. Then more thresholds within the range set by MEE were added for these industries to form more detailed and clearer instructions. These thresholds were made based on historic emission levels of the industries to make sure that the firms could adapt to the rules (Table 1). Apart from COD, similar revise was applied to other chemicals listed in the MEE documents.

Emission standards for COD of the MEE and DEEJ (mg/L)

| MEE | Jiangsu | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct emission | Special standard | Industries | Direct emission | Special standard | |||

| Emission standard of COD | 60 | 50 | Basic chemicals | Inorganic chemicals | Nitric acid, sodium carbonate, and vitriol | 60 | 50 |

| Rest | 50 | 40 | |||||

| Organic chemicals | 60 | 50 | |||||

| 100 for polyacrylonitrile, caprolactam, epichlorohydrin, Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), pure terephthalic acid (PTA), meta-cresol, epoxypropane, naphthalene series compounds and catalysts | Fertilizer | 70 | 50 | ||||

| Pesticides | 80 | 60 | |||||

| Paint, ink pigment, and other similar products | 70 | 50 | |||||

| Explosive, firer, fireworks | 80 | 60 | |||||

| Rest | 70 | 60 | |||||

Source: Government websites, complied by author.

An example for the second method is the “263” special project initiated by Jiangsu Government in 2017.[4] The targets of the project were reducing the consuming amount of coal and the production capacity of traditional petrochemical engineering (the “2”); managing water quality of Taihu Lake, household waste, watercourses, VOCs, pollution of the animal husbandry, and other environmental hazards (the “6”); and improving ecological protection, law enforcement, and supervision and economic regulations (the “3”). There were 11 subprojects for every aspect with specific quantitative targets. For instance, the whole province should reduce the amount of coal consumption by 32 million tons by 2020, replace the coal-firing boilers with the power less than 10-ton vapour per hour with clean energy alternatives by the end of 2017, and finish renovation of the 52 provincial industrial parks. The special project supplemented the central policies with practical actions as it seldom set new standards but explicitly pointed out what should be done to meet the given standards. The regulations from central government cannot provide such details in the policy execution due to the unfamiliarity with local situations. By modifying central standards and making practical implementation plans, the local governments can efficiently carry out environmental regulations.

Though the central government dispatches environmental inspection teams across the country, the frequency for every place is low because of the vast territory and the limited number of staff. Therefore, the other important part of local environmental regulations is supervision and punishment on corporates. Provincial and municipal governments have different focuses on how to supervise and punish. First, the provincial government issues specific supervising and punishing measures and organizes teams of experts and officials to inspect into firms regularly and occasionally. For supervision, the Jiangsu Government enacted a method on supervising pollutant discharge in 2019 (DEEJ, 2019). The method proposed three ways of firms monitoring emission by themselves, including commissioning agencies for manual monitor, manual self-monitor, and automatic self-monitor. Emission levels of SO2, particulate matter, and 11 other pollutants were used for evaluation. The results should be disclosed comprehensively and in time. For punishment, in 2008, the Jiangsu Government published the hardest punishing measures across the country on excessive emission with the maximum of 1 million Yuan fine, and the notice of criticism or warning circulated on government and social platforms and even the mandatory shutdown if the rectification did not meet the requirements.[5]

Second, the municipal government is the enforcer of supervision and punishment. The corporates need to report monthly self-monitoring data to the Department of Environmental Protection of Nanjing (DEPN). DEPN examines the data, reports to DEEJ (if necessary), and then issues fines, criticism, or warning accordingly. Moreover, central and provincial teams only go into corporates two to three times a year, but DEPN conducts much frequent field inspections. During the visit, the officials and technicists inspect the production process, interview with front-line workers, and hold meetings with firm leaders. The officials are here to emphasize the importance of complying with regulations, while the technicists conduct inspections by themselves to verify the self-monitoring data provided by the firm.

One manager explained the profound influences of local environmental regulations on technological innovation.

The stringent policies of Jiangsu and Nanjing force us to keep upgrading our production measures. For example, even though we have developed products with less emission, they still emit something. But the Jiangsu government requires that if the company starts new projects with emission, the existing projects must reduce emission in double amount. We have to keep investing to find ways of reducing more emission even though we have met all the standards of central and local policies. On the other hand, we need to be prepared for the visits from Nanjing, Jiangsu, and the central inspection teams. We must not make any mistakes because being in the notice of criticism and warning exerts very negative influences on our reputation. What we cannot afford is not the fines but the damage of our image, especially when we are the leader and a renowned SOE in the sector.

Compared with the prescriptive standards made by the central government, the ones of the local governments have more direct effects on promoting the innovation of SYPC. The stricter and detailed nature of local regulations significantly drives SYPC’s technological innovation compared to central policies.

4.3 The Headquarters Level: The Performance Management Systems

The SINOPEC headquarters resembles the local governments in making environmental regulations. Their system rapidly processes and tailors central policies to align with the company’s objectives, with indicators stricter than central policies but different from local regulations. The indicators are modified to fit into the development plans of the company. For SYPC, the headquarters-level indicators for production are stricter than those of central policies, but the strictness is different from that of the Jiangsu Government. The headquarters considers more from a sectoral perspective and requires the company to outperform domestic and international competitors. The Jiangsu Government cares more about how to restrict emission but also to maintain a high level of production to both protect environment and promote development. The headquarters also sends teams to SYPC for patrol inspections with the similar intentions of DEPN.

Except similarities, the unique characteristic of the headquarters-level regulations is the performance management systems. Two systems saliently affect behaviours of branch companies. One is named HSE (the initials of health, safety, and environment) enacted in 2001.[6] The ultimate goals of HSE were zero injury, zero accident, and zero pollution. HSE consisted of the safety performance index (SPI) and environmental performance index (EPI). EPI was based on different quantitative indicators such as the number of environmental emergencies and the amount of various pollutant emission. EPI and SPI of subsidiaries were calculated and evaluated by the headquarters. In 2018, HSE was upgraded into (the initials of health, safety of production, safety of public, and environment) in which the safety was refined into production safety and public safety. The other one is the green corporate action plan (GCAP) in 2018.[7] The plan proposed six aspects of building a green corporate including green development, green energy, green production, green services, green technology, and green culture. Every aspect was quantified with several indicators and the evaluating procedure was the same as that of HSE. The results of these systems directly link to honorary titles, bonus, fines, and criticism, affecting the strategic position of the branch in the group company.

Besides stringent measures, the headquarters intends to motivate subsidiaries by creating a competitive environment. But the performance management is increasingly associated with extra quantified targets set by SYPC itself and becomes stressful. As one manager suggested:

We are determined to implement the HSSE and GCAP as the headquarters asks. The company (SYPC) set the plan to build the green corporate in 2018 with a specific schedule. Every stage was with a clear deadline and related staff needed to sign the letter of responsibility (ze ren zhuang) under the accountability system. There are monthly assessments of how well the systems are carried out. All the personnel in the company are under a grading system on how much they contribute to the systems that connects to individual performance evaluation. In this situation, all the aspects of SYPC, surely including technological innovation, have been extensively improved.

Performance management belongs to the flexible instrument, and according to the narrow version of the PH, it better motivates corporates to innovate than stringent policies. For the question about whether the performance management systems give greater incentives to innovate, the same manager said:

These systems cannot be separated from the standards of the headquarters and the government. Accomplishing those standards is the basic requirement, but is already very challenging. The systems are more like a reminder of the standards. On the other hand, a competitive environment indeed encourages innovation. For example, many of our staff took part in the contests for product design and production techniques held by the headquarters and achieved amazing performances that benefit both themselves and SYPC.

What this manager said reveals that the effects of stringent and flexible instruments on innovation intertwine with each other instead of being separated. The performance management is first to guarantee that emission standards from the government and headquarters are fulfilled, and then to gain extra innovation. Though the flexible instruments lead to extra incentives for and performance of innovation, the “more space” for managers and other employees is built on the pressure under realizing prescriptive standards (Arimura et al., 2007).

4.4 The Influences of Regulations on SYPC Performance

The multi-level regulatory measures significantly foster SYPC’s technological innovation, aligning with the company’s emphasis on social responsibility over profitability. One manager gave his explanation:[8]

We are a renowned SOE. Earning profits is only a part of our goals. We have social responsibilities to create a better environment. We have made great achievement and won many national and local level honorary titles such as the ‘environmentally friendly corporate in China’. We also increase the investment in improving working conditions, salaries and welfare of our staff to promote their sense of happiness.

This manager seems to pay more attention to the social responsibility. Existing studies have suggested that for the managers of SOEs in China, the greater policy burden on them, the higher level of extra perks they can get (Jian et al., 2020). In contrast, they care less about the performance because they can use the policy burden as “an excuse” (Liao et al., 2009). These perspectives are to some extent reflected through what this manager said. SYPC has used money it earns to improve the environment and treatment of staff both emphasized by the government so that the net profits are limited. But implementing policy objectives for the environment indeed brings SYPC better performance according to another manager:

We have won many honorary titles that in fact benefit our performance. First, the government prioritizes corporates with more honorary titles and awards when it approves new projects. Second, a good reputation increases public recognition of the company important to our sale of products.

Based on the two managers in this subsection, implementing regulations promotes economic performance of SYPC but which cannot be reflected by the net profits because the company keeps investing in technology and welfare of the staff. Although this article does not have the access to the revenue of SYPC for verification, the view should be correct since the company maintains a mid-level of profitability whilst increasing other investments. The preferences by the government and the public are two ways of how following regulations helps with performance. It is important for corporates to gain the preference by the local government as it controls considerable natural, market, and political resources. For example, local governments profoundly influence local markets through SOEs in all industries (Broadman, 2001). For an industrial corporate, it is likely that its main business partners in the upstream and downstream industries are local SOEs. Financial institutions providing capital to the firm are primarily state-owned commercial banks. The company gains preferential treatment from the government for new projects and increased public recognition, both vital to its product sales. This alignment with regulations supports SYPC’s economic performance through government preference and public acceptance, emphasizing the company’s importance in the local market and its appeal to environmentally conscious consumers. Studies also suggest that a “green” reputation and acceptability by the public significantly affect economic performance of the corporate (Tang et al., 2012).

Table 2 shows the distinctive regulative levels for SYPC, their main characteristics, and important connected results.

Multi-Level environmental regulations on firm performance in China: SYPC

| Levels | Characteristics | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Central level | Guide lines | Overview of regulations and set limitations for other levels |

| Instructive | Force the Headquarter of SYPC to implement specified restrictions for regional subsidiary corporation | |

| Head-quarter level | Stringent | Raise the environmental awareness of employees’ |

| Promote technological innovation of SYPC | ||

| Local level | Even stricter and based on local situations | Promote technological transformations and innovation of subsidiary corporations of SYPC |

| With rewards and punishment | Enhance the pulse of productivity for good reputation |

5 Conclusion

This article investigates the influences of multi-level environmental regulations on firm performance in China with a case study focusing on SYPC, a leading SOE in the petrochemical industry. As shown in Table 2, the stringent regulations from the central and local governments and the SINOPEC headquarters promote technological innovation of SYPC, verifying the “weak” version of the PH. Measures from different levels take effects in distinct ways. The central regulations include guiding concepts and detailed standards. The former incentivizes SYPC to innovate, while the latter fosters the regulations of Jiangsu and Nanjing governments that modify the central indicators and come up with implementation plans based on local situations. These local standards and plans promote the innovation of SYPC not only because these standards are stricter than the central ones but also the plans assign more specific and concrete tasks for the company to finish. The other part of local regulations focuses on supervision and punishment which also motivate SYPC to keep innovating as it does not want the reputation to be damaged by being in the notice of warning or criticism. The headquarter-level regulations include similar measures of local governments such as strict standards, supervision and punishment, and flexible instruments represented by the performance management systems. The systems give extra incentives to SYPC to innovate after it meets all the standards. This result enriches the understanding of the “narrow” version of the PH that the greater incentives from flexible regulations may consist of the incentives from stringent policies and extra motivation from a competitive environment. The effects of flexible and stringent measures are not independent but intertwined. The multi-level regulations improve the economic performance of SYPC mainly by technological innovation, a good relationship with the local governments and popularity in the public, supporting the “strong” version of the PH.

The findings of this article contribute to debate on how SOEs are affected by environmental regulations. Existing studies tend to suggest that SOEs receive preferential treatment in different forms due to their relations with the government. They have easier access to capital and credit and have more ways of circumvent regulations. The case of SYPC provides new knowledge to these perspectives. The company actively implements environmental policies and fulfils their social responsibilities, but it is also a part of the strategy of SINOPEC circumventing regulations. SYPC stopped producing traditional gasoline to reduce the emission. The production was allocated by the headquarters to other small-scale subsidiaries such as the SINOPEC Jinling Petrochemical Company that locate in different provinces. SINOPEC does not choose to ignore local policies though SYPC is of the similar administrative level with Nanjing and makes substantial contribution to local economy (Eaton & Kostka, 2017). Given the vast territory and regional disparity of China, giant central SOEs with many subsidiaries can be compared to multi-national enterprises. Rugman and Verbeke suggest that multi-national enterprises may move the production abroad, increase exports to countries with less regulations, geographically concentrate to form an innovation cluster, or shift previous export patterns to FDI to secure a market under environmental regulations (Rugman & Verbeke, 1998).

The research, while offering illuminating insights into the interconnected influences of environmental regulations on firm performance, possesses certain limitations. Primarily centred on a single-case study of SYPC in China, the study’s findings might lack broad applicability across various industries or regions. In addition, the depth of analysis may overlook nuanced factors impacting performance, raising the need for a more comprehensive exploration. Future research endeavours could benefit from expanding beyond singular case studies to encompass multiple industries, fostering a deeper understanding of how environmental regulations shape diverse enterprises. Longitudinal studies tracking the long-term effects of compliance, consideration of socio-economic impacts, and an exploration of technology’s role in aiding firms to adapt within evolving regulatory landscapes could further enrich this field of study.

This study holds practical significance for both industry players and policymakers. The findings highlighted by the article in fact have implications for the studies on environmental policy making. For businesses, especially within energy or petrochemical sectors, it provides valuable guidance in aligning strategies with environmental standards and fostering innovation in green technology. Policymakers can leverage these insights to refine regulations, considering the varying influences of central-, local-, and corporate-level regulations on firm performance. Strategic decision-making for sustainable practices stands to benefit from a deeper understanding of compliance dynamics, derived from this study. Future research avenues could explore broader industry coverage beyond singular case studies, conduct longitudinal analyses to track regulatory impacts over time, delve into socio-economic implications, and investigate the integration of technology in adapting to evolving environmental regulatory frameworks.

Acknowledgement

Sincere thanks Dr. Li Zhenfa for assistance to meet and discuss preliminary thinking in the preparation of this manuscript.

-

Funding information: Author states no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection and compilation, interviewing, analysis, and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data used to support the findings of this study are all in the manuscript.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

References

Arimura, T., Hibiki, A., & Johnstone, N. (2007). An empirical study of environmental R&D: What encourages facilities to be environmentally innovative. In Nick Johnstone (Ed.), Environmental policy and corporate behaviour (pp. 142–173). Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781781953020.00009Search in Google Scholar

Broadman, H. G. (2001). The business(es) of the Chinese state. World Economy, 24(7), 849–875.10.1111/1467-9701.00386Search in Google Scholar

Cai, X., Zhu, B., Zhang, H., Li, L., & Xie, M. (2020). Can direct environmental regulation promote green technology innovation in heavily polluting industries? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Science of the Total Environment, 746, 140810.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140810Search in Google Scholar

Christiansen, H. (2011). The size and composition of the SOE sector in OECD countries. OECD Corporate Governance Working Papers (Vol. 5). Paris: OECD Corporate Affairs Division.Search in Google Scholar

DeCanio, S. J. (1998). The efficiency paradox: bureaucratic and organizational barriers to profitable energy-saving investments. Energy Policy, 26(5), 441–454.10.1016/S0301-4215(97)00152-3Search in Google Scholar

DeCanio, S. J., Dibble, C., & Amir-Atefi, K. (2000). The importance of organizational structure for the adoption of innovations. Management Science, 46(10), 1285–1299.10.1287/mnsc.46.10.1285.12270Search in Google Scholar

DEEJ (Department of Ecology and Environment of Jiangsu). (2019). Strengthening corporate own monitoring pollutant emission in Jiangsu. http://hbt.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2019/6/19/art_1628_8366274.html. Accessed 20 February 2022.Search in Google Scholar

DEEJ (Department of Ecology and Environment of Jiangsu). (2020). Emission standards of water pollutants from the chemical industry in Jiangsu. http://hbt.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2020/8/12/art_1586_9446397.html. Accessed 20 February 2022.Search in Google Scholar

Eaton, S., & Kostka, G. (2017). Central protectionism in China: The “central SOE problem” in environmental governance. The China Quarterly, 231, 685–704.10.1017/S0305741017000881Search in Google Scholar

Fu, S., Ma, Z., Ni, B., Peng, J., Zhang, L., & Fu, Q. (2021). Research on the spatial differences of pollution-intensive industry transfer under the environmental regulation in China. Ecological Indicators, 129, 107921.10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107921Search in Google Scholar

Ghaedamini Harouni, A., Babaeefarsani, M., Sadeghi De Cheshmeh, M., & Maleki Farsani, G. R. (2023). The impact of enterprise resource planning on operational performance through supply chain orientation using in Faradaneh company. Innovation Management and Operational Strategies, 4(3), 219–232. doi: 10.22105/imos.2021.291375.1122.Search in Google Scholar

Ghanbari, J., Abbasi, E., Didekhani, H., & Ashrafi, M. (2022). The impact of strategic cost management on the relationship between supply chain practices, top management support and financial performance improvement. Journal of Applied Research on Industrial Engineering, 9(1), 32–49. doi: 10.22105/jarie.2021.294904.1364.Search in Google Scholar

Gibbs, D., & Jonas, A. E. (2000). Governance and regulation in local environmental policy: The utility of a regime approach. Geoforum, 31(3), 299–313.10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00052-4Search in Google Scholar

Gray, W. B., & Shadbegian, R. J. (2003). Plant vintage, technology, and environmental regulation. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 46(3), 384–402.10.1016/S0095-0696(03)00031-7Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Y., Huy, Q. N., & Xiao, Z. (2017). How middle managers manage the political environment to achieve market goals: Insights from China’s state‐owned enterprises. Strategic Management Journal, 38(3), 676–696.10.1002/smj.2515Search in Google Scholar

He, G., Wang, S., & Zhang, B. (2020). Watering down environmental regulation in China. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(4), 2135–2185.10.1093/qje/qjaa024Search in Google Scholar

Heberer, T., & Senz, A. (2011). Streamlining local behaviour through communication, incentives and control: a case study of local environmental policies in China. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 40(3), 77–112.10.1177/186810261104000304Search in Google Scholar

Jaffe, A. B., & Palmer, K. (1997). Environmental regulation and innovation: a panel data study. Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(4), 610–619.10.1162/003465397557196Search in Google Scholar

Jian, J., Li, H., Meng, L., & Zhao, C. (2020). Do policy burdens induce excessive managerial perks? Evidence from China’s stated-owned enterprises. Economic Modelling, 90, 54–65.10.1016/j.econmod.2020.05.002Search in Google Scholar

Kostka, G., & Mol, A. P. (2013). Implementation and participation in China’s local environmental politics: Challenges and innovations. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 15(1), 3–16.10.1080/1523908X.2013.763629Search in Google Scholar

Kostka, G., & Nahm, J. (2017). Central–local relations: Recentralization and environmental governance in China. The China Quarterly, 231, 567–582.10.1017/S0305741017001011Search in Google Scholar

Lanoie, P., Laurent‐Lucchetti, J., Johnstone, N., & Ambec, S. (2011). Environmental policy, innovation and performance: New insights on the Porter hypothesis. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 20(3), 803–842.10.1111/j.1530-9134.2011.00301.xSearch in Google Scholar

Liao, G., Chen, X., Jing, X., & Sun, J. (2009). Policy burdens, firm performance, and management turnover. China Economic Review, 20(1), 15–28.10.1016/j.chieco.2008.11.005Search in Google Scholar

Lin, L. (2017). Reforming China’s state-owned enterprises: From structure to people. The China Quarterly, 229, 107–129.10.1017/S0305741016001569Search in Google Scholar

Liu, K., & Lin, B. (2019). Research on influencing factors of environmental pollution in China: A spatial econometric analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 206, 356–364.10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.194Search in Google Scholar

Maurel, M., & Pernet, T. (2021). New evidence on the soft budget constraint: Chinese environmental policy effectiveness in SOE-dominated cities. Public Choice, 187(1), 111–142.10.1007/s11127-020-00834-1Search in Google Scholar

Mohr, R. D. (2002). Technical change, external economies, and the Porter hypothesis. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 43(1), 158–168.10.1006/jeem.2000.1166Search in Google Scholar

Mohr, R. D., & Saha, S. (2008). Distribution of environmental costs and benefits, additional distortions, and the Porter hypothesis. Land Economics, 84(4), 689–700.10.3368/le.84.4.689Search in Google Scholar

Porter, M. E., & Van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 97–118.10.1257/jep.9.4.97Search in Google Scholar

Rexhäuser, S., & Rammer, C. (2014). Environmental innovations and firm profitability: Unmasking the Porter hypothesis. Environmental and Resource Economics, 57(1), 145–167.10.1007/s10640-013-9671-xSearch in Google Scholar

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. (1998). Corporate strategies and environmental regulations: An organizing framework. Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 363–375.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199804)19:4<363::AID-SMJ974>3.0.CO;2-HSearch in Google Scholar

Sari, D., & Tjen, C. (2017). Corporate social responsibility disclosure, environmental performance, and tax aggressiveness. International Research Journal of Business Studies, 9(2), 93–104.10.21632/irjbs.9.2.93-104Search in Google Scholar

Shah, S. G. M., Sarfraz, M., & Ivascu, L. (2021). Assessing the interrelationship corporate environmental responsibility, innovative strategies, cognitive and hierarchical CEO: A stakeholder theory perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), 457–473.10.1002/csr.2061Search in Google Scholar

Shi, X., & Xu, Z. (2018). Environmental regulation and firm exports: Evidence from the eleventh Five-Year Plan in China. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 89, 187–200.10.1016/j.jeem.2018.03.003Search in Google Scholar

Szamosszegi, A. Z., & Kyle, C. (2011). An analysis of state-owned enterprises and state capitalism in China. Washington, DC: US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.Search in Google Scholar

Tang, A. K., Lai, K. H., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2012). Environmental governance of enterprises and their economic upshot through corporate reputation and customer satisfaction. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21(6), 401–411.10.1002/bse.1733Search in Google Scholar

Taşkan, B., & Karatop, B. (2022). Development of the field of organizational performance during the industry 4.0 period. International Journal of Research in Industrial Engineering, 11(2), 134–154. doi: 10.22105/riej.2022.324520.1286.Search in Google Scholar

Testa, F., Iraldo, F., & Frey, M. (2011). The effect of environmental regulation on firms’ competitive performance: The case of the building & construction sector in some EU regions. Journal of Environmental Management, 92(9), 2136–2144.10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.03.039Search in Google Scholar

Wang, H., & Wheeler, D. (2005). Financial incentives and endogenous enforcement in China’s pollution levy system. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 49(1), 174–196.10.1016/j.jeem.2004.02.004Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Y., & Shen, N. (2016). Environmental regulation and environmental productivity: The case of China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 62, 758–766.10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.048Search in Google Scholar

Wei, Z., Varela, O., & Hassan, M. K. (2002). Ownership and performance in Chinese manufacturing industry. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 12(1), 61–78.10.1016/S1042-444X(01)00026-3Search in Google Scholar

Xu, C. (2011). The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(4), 1076–1151.10.1257/jel.49.4.1076Search in Google Scholar

Yuan, B., & Xiang, Q. (2018). Environmental regulation, industrial innovation and green development of Chinese manufacturing: Based on an extended CDM model. Journal of Cleaner Production, 176, 895–908.10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.034Search in Google Scholar

Yuan, B., Ren, S., & Chen, X. (2017). Can environmental regulation promote the coordinated development of economy and environment in China’s manufacturing industry? -A panel data analysis of 28 sub-sectors. Journal of Cleaner Production, 149, 11–24.10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.065Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Z. X. (2007). China is moving away the pattern of “develop first and then treat the pollution”. Energy Policy, 35(7), 3547–3549.10.1016/j.enpol.2007.02.002Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, X., Fan, Y., Fang, M., & Hua, Z. (2018). Do environmental regulations undermine energy firm performance? An empirical analysis from China’s stock market. Energy Research & Social Science, 40, 220–231.10.1016/j.erss.2018.02.014Search in Google Scholar

Zhou, Y., Zhu, S., & He, C. (2017). How do environmental regulations affect industrial dynamics? Evidence from China’s pollution-intensive industries. Habitat International, 60, 10–18.10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.12.002Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Political Turnover and Public Health Provision in Brazilian Municipalities

- Examining the Effects of Trade Liberalisation Using a Gravity Model Approach

- Operating Efficiency in the Capital-Intensive Semiconductor Industry: A Nonparametric Frontier Approach

- Does Health Insurance Boost Subjective Well-being? Examining the Link in China through a National Survey

- An Intelligent Approach for Predicting Stock Market Movements in Emerging Markets Using Optimized Technical Indicators and Neural Networks

- Analysis of the Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion in Promoting Inclusive Growth: Mechanism and Statistical Verification

- Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size under Turnover Tax: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on SMEs

- Re-investigating the Impact of Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development, Institutional Quality, and Globalization on Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries

- A Compliance Return Method to Evaluate Different Approaches to Implementing Regulations: The Example of Food Hygiene Standards

- Panel Technical Efficiency of Korean Companies in the Energy Sector based on Digital Capabilities

- Time-varying Investment Dynamics in the USA

- Preferences, Institutions, and Policy Makers: The Case of the New Institutionalization of Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance in Colombia

- The Impact of Geographic Factors on Credit Risk: A Study of Chinese Commercial Banks

- The Heterogeneous Effect and Transmission Paths of Air Pollution on Housing Prices: Evidence from 30 Large- and Medium-Sized Cities in China

- Analysis of Demographic Variables Affecting Digital Citizenship in Turkey

- Green Finance, Environmental Regulations, and Green Technologies in China: Implications for Achieving Green Economic Recovery

- Coupled and Coordinated Development of Economic Growth and Green Sustainability in a Manufacturing Enterprise under the Context of Dual Carbon Goals: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality

- Revealing the New Nexus in Urban Unemployment Dynamics: The Relationship between Institutional Variables and Long-Term Unemployment in Colombia

- The Roles of the Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate in the Current Account Balance

- Cleaner Production: Analysis of the Role and Path of Green Finance in Controlling Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

- The Research on the Impact of Regional Trade Network Relationships on Value Chain Resilience in China’s Service Industry

- Social Support and Suicidal Ideation among Children of Cross-Border Married Couples

- Asymmetrical Monetary Relations and Involuntary Unemployment in a General Equilibrium Model

- Job Crafting among Airport Security: The Role of Organizational Support, Work Engagement and Social Courage

- Does the Adjustment of Industrial Structure Restrain the Income Gap between Urban and Rural Areas

- Optimizing Emergency Logistics Centre Locations: A Multi-Objective Robust Model

- Geopolitical Risks and Stock Market Volatility in the SAARC Region

- Trade Globalization, Overseas Investment, and Tax Revenue Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Can Government Expenditure Improve the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service? – Take Wuhan as an Example

- Media Tone and Earnings Management before the Earnings Announcement: Evidence from China

- Review Articles

- Economic Growth in the Age of Ubiquitous Threats: How Global Risks are Reshaping Growth Theory

- Efficiency Measurement in Healthcare: The Foundations, Variables, and Models – A Narrative Literature Review

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm

- Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy

- Special Issue: Economic Implications of Management and Entrepreneurship - Part II

- Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study on Entrepreneurial Tendency of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA in the Context of the Interactive Model

- Bridging Brand Parity with Insights Regarding Consumer Behavior

- The Effect of Green Human Resources Management Practices on Corporate Sustainability from the Perspective of Employees

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation in Economics and Management Decision - Part II

- High-Quality Development of Sports Competition Performance Industry in Chengdu-Chongqing Region Based on Performance Evaluation Theory

- Analysis of Multi-Factor Dynamic Coupling and Government Intervention Level for Urbanization in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt

- The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Technological Innovation of Enterprises: Based on Empirical Evidences of the Implementation of Pollution Charges in China

- Environmental Social Responsibility, Local Environmental Protection Strategy, and Corporate Financial Performance – Empirical Evidence from Heavy Pollution Industry

- The Relationship Between Stock Performance and Money Supply Based on VAR Model in the Context of E-commerce

- A Novel Approach for the Assessment of Logistics Performance Index of EU Countries

- The Decision Behaviour Evaluation of Interrelationships among Personality, Transformational Leadership, Leadership Self-Efficacy, and Commitment for E-Commerce Administrative Managers

- Role of Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurship Across the Diverse Economic Stages: Insights from GEM and GLOBE Data

- Performance Evaluation of Economic Relocation Effect for Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations: Evidence from China

- Functional Analysis of English Carriers and Related Resources of Cultural Communication in Internet Media

- The Influences of Multi-Level Environmental Regulations on Firm Performance in China

- Exploring the Ethnic Cultural Integration Path of Immigrant Communities Based on Ethnic Inter-Embedding

- Analysis of a New Model of Economic Growth in Renewable Energy for Green Computing

- An Empirical Examination of Aging’s Ramifications on Large-scale Agriculture: China’s Perspective

- The Impact of Firm Digital Transformation on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: Evidence from China

- Accounting Comparability and Labor Productivity: Evidence from China’s A-Share Listed Firms

- An Empirical Study on the Impact of Tariff Reduction on China’s Textile Industry under the Background of RCEP

- Top Executives’ Overseas Background on Corporate Green Innovation Output: The Mediating Role of Risk Preference

- Neutrosophic Inventory Management: A Cost-Effective Approach

- Mechanism Analysis and Response of Digital Financial Inclusion to Labor Economy based on ANN and Contribution Analysis

- Asset Pricing and Portfolio Investment Management Using Machine Learning: Research Trend Analysis Using Scientometrics

- User-centric Smart City Services for People with Disabilities and the Elderly: A UN SDG Framework Approach

- Research on the Problems and Institutional Optimization Strategies of Rural Collective Economic Organization Governance

- The Impact of the Global Minimum Tax Reform on China and Its Countermeasures

- Sustainable Development of Low-Carbon Supply Chain Economy based on the Internet of Things and Environmental Responsibility

- Measurement of Higher Education Competitiveness Level and Regional Disparities in China from the Perspective of Sustainable Development

- Payment Clearing and Regional Economy Development Based on Panel Data of Sichuan Province

- Coordinated Regional Economic Development: A Study of the Relationship Between Regional Policies and Business Performance

- A Novel Perspective on Prioritizing Investment Projects under Future Uncertainty: Integrating Robustness Analysis with the Net Present Value Model

- Research on Measurement of Manufacturing Industry Chain Resilience Based on Index Contribution Model Driven by Digital Economy

- Special Issue: AEEFI 2023

- Portfolio Allocation, Risk Aversion, and Digital Literacy Among the European Elderly

- Exploring the Heterogeneous Impact of Trade Agreements on Trade: Depth Matters

- Import, Productivity, and Export Performances

- Government Expenditure, Education, and Productivity in the European Union: Effects on Economic Growth

- Replication Study

- Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: A Replication of Andersson (American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2019)

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Political Turnover and Public Health Provision in Brazilian Municipalities

- Examining the Effects of Trade Liberalisation Using a Gravity Model Approach

- Operating Efficiency in the Capital-Intensive Semiconductor Industry: A Nonparametric Frontier Approach

- Does Health Insurance Boost Subjective Well-being? Examining the Link in China through a National Survey

- An Intelligent Approach for Predicting Stock Market Movements in Emerging Markets Using Optimized Technical Indicators and Neural Networks

- Analysis of the Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion in Promoting Inclusive Growth: Mechanism and Statistical Verification

- Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size under Turnover Tax: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on SMEs

- Re-investigating the Impact of Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development, Institutional Quality, and Globalization on Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries

- A Compliance Return Method to Evaluate Different Approaches to Implementing Regulations: The Example of Food Hygiene Standards

- Panel Technical Efficiency of Korean Companies in the Energy Sector based on Digital Capabilities

- Time-varying Investment Dynamics in the USA

- Preferences, Institutions, and Policy Makers: The Case of the New Institutionalization of Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance in Colombia

- The Impact of Geographic Factors on Credit Risk: A Study of Chinese Commercial Banks

- The Heterogeneous Effect and Transmission Paths of Air Pollution on Housing Prices: Evidence from 30 Large- and Medium-Sized Cities in China

- Analysis of Demographic Variables Affecting Digital Citizenship in Turkey

- Green Finance, Environmental Regulations, and Green Technologies in China: Implications for Achieving Green Economic Recovery

- Coupled and Coordinated Development of Economic Growth and Green Sustainability in a Manufacturing Enterprise under the Context of Dual Carbon Goals: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality

- Revealing the New Nexus in Urban Unemployment Dynamics: The Relationship between Institutional Variables and Long-Term Unemployment in Colombia

- The Roles of the Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate in the Current Account Balance

- Cleaner Production: Analysis of the Role and Path of Green Finance in Controlling Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

- The Research on the Impact of Regional Trade Network Relationships on Value Chain Resilience in China’s Service Industry

- Social Support and Suicidal Ideation among Children of Cross-Border Married Couples

- Asymmetrical Monetary Relations and Involuntary Unemployment in a General Equilibrium Model

- Job Crafting among Airport Security: The Role of Organizational Support, Work Engagement and Social Courage

- Does the Adjustment of Industrial Structure Restrain the Income Gap between Urban and Rural Areas

- Optimizing Emergency Logistics Centre Locations: A Multi-Objective Robust Model

- Geopolitical Risks and Stock Market Volatility in the SAARC Region

- Trade Globalization, Overseas Investment, and Tax Revenue Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Can Government Expenditure Improve the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service? – Take Wuhan as an Example

- Media Tone and Earnings Management before the Earnings Announcement: Evidence from China

- Review Articles

- Economic Growth in the Age of Ubiquitous Threats: How Global Risks are Reshaping Growth Theory

- Efficiency Measurement in Healthcare: The Foundations, Variables, and Models – A Narrative Literature Review

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm

- Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy

- Special Issue: Economic Implications of Management and Entrepreneurship - Part II

- Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study on Entrepreneurial Tendency of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA in the Context of the Interactive Model

- Bridging Brand Parity with Insights Regarding Consumer Behavior

- The Effect of Green Human Resources Management Practices on Corporate Sustainability from the Perspective of Employees

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation in Economics and Management Decision - Part II

- High-Quality Development of Sports Competition Performance Industry in Chengdu-Chongqing Region Based on Performance Evaluation Theory

- Analysis of Multi-Factor Dynamic Coupling and Government Intervention Level for Urbanization in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt

- The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Technological Innovation of Enterprises: Based on Empirical Evidences of the Implementation of Pollution Charges in China

- Environmental Social Responsibility, Local Environmental Protection Strategy, and Corporate Financial Performance – Empirical Evidence from Heavy Pollution Industry

- The Relationship Between Stock Performance and Money Supply Based on VAR Model in the Context of E-commerce

- A Novel Approach for the Assessment of Logistics Performance Index of EU Countries

- The Decision Behaviour Evaluation of Interrelationships among Personality, Transformational Leadership, Leadership Self-Efficacy, and Commitment for E-Commerce Administrative Managers

- Role of Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurship Across the Diverse Economic Stages: Insights from GEM and GLOBE Data

- Performance Evaluation of Economic Relocation Effect for Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations: Evidence from China

- Functional Analysis of English Carriers and Related Resources of Cultural Communication in Internet Media

- The Influences of Multi-Level Environmental Regulations on Firm Performance in China

- Exploring the Ethnic Cultural Integration Path of Immigrant Communities Based on Ethnic Inter-Embedding

- Analysis of a New Model of Economic Growth in Renewable Energy for Green Computing

- An Empirical Examination of Aging’s Ramifications on Large-scale Agriculture: China’s Perspective

- The Impact of Firm Digital Transformation on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: Evidence from China

- Accounting Comparability and Labor Productivity: Evidence from China’s A-Share Listed Firms

- An Empirical Study on the Impact of Tariff Reduction on China’s Textile Industry under the Background of RCEP