Abstract

Due to the impact of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic isolation, the E-commerce market encountered great impact and changes. Faced with such a transformed situation, E-Commerce administrative managers usually have different individual personalities and transformational leadership to enhance leadership self-efficacy and organizational commitment. The purpose of this study is to investigate the interrelationships among the personality, transformational leadership, leadership self-efficacy, and commitment of E-Commerce administrative managers. The research population is randomly selected from E-Commerce administrative managers who are responsible for E-Commerce administrative affairs. Based on a sample of 408 participants, the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is applied to examine the construct validity. Then, the Structured Equation Modelling (SEM) method is used to estimate a series of interrelated dependent relationships and perform a comprehensive model. The research results show that a leader with Big Five personality traits has a positive influence on transformational leadership and leadership self-efficacy. An E-Commerce administrative manager with transformational leadership behaviours has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy. In addition, an E-Commerce administrative manager with leadership self-efficacy has a positive influence on commitment. The research results contribute to a better evaluation model of E-Commerce administrative manager’s leadership by applying their personalities and transformational leadership to enhance leadership self-efficacy and increase the level of organizational commitment.

1 Introduction

After the impact of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic in recent years, many industries have greatly suffered from the epidemic storm. On the contrary, the E-commerce market benefits significantly due to the impact of the epidemic isolation. What kind of personality and leadership should an E-commerce manager have to cope with the growth of the E-commerce market? E-Commerce administrative managers should have different individual personalities and transformational leadership to enhance leadership self-efficacy and achieve individual and organizational commitment. By adopting potential innovation personality and transformational leadership behaviours that seek to offer employee freedom on the job, a feeling of attachment to the organization, and a positive perception of leadership support, E-Commerce managers can potentially foster employee innovation and stimulate organizational performance that could enhance employee job autonomy and achieve leadership self-efficacy. Also, managers could stimulate organizational innovation and business success and then finally attain organizational commitment. The background of this study is to investigate the interrelationships among the personality, transformational leadership, leadership self-efficacy, and commitment of E-Commerce administrative managers.

E-commerce managers should have different individual personalities that reflect different personal values, which are based on achieving their goals. These different personality traits are the main determinants of a leader’s behaviour (Salmony & Kanbach, 2022). Some researchers have only focused on either leader’s appraisals and other researchers have concentrated in the military or educational realms. Personality is an individual-specific nature that indicates individual psychological maturity and development in the interactive process from individual and environmental influences (Messick, 2021). Many specific types of personalities were found in the dictionaries and research studies. In this study, Goldberg’s “Big Five” Personality Traits (Goldberg, 1990) are categorized as a Big Five Model (BFM), including (1) Extraversion, (2) Agreeableness, (3) Conscientiousness, (4) Emotional Stability, and (5) Openness.

In the post-pandemic era, E-commerce managers should possess the characteristics of transformational leadership to develop a variety of motivational strategies. Transformational leadership is assumed as the phenomenon that people are ready to work vigorously when they are motivated to carry out the expected destination under the appropriate situations (Hai et al., 2021). The concept of transformational leadership is based on the inspiration of the follower’s intrinsic motivation to carry out desired assignments by means of leader’s motivation and guidance (Purwanto, 2022). According to Bass and Avolio (Messick, 2021), transformational leadership is classified into the following four categories in this study: (1) idealized influence, (2) inspirational motivation, (3) intellectual stimulation, and (4) individualized consideration, which are generally abbreviated as the “Four I’s” by most researchers (Bass & Avolio, 1994).

In addition to transformational leadership, E-commerce managers also should promote individual leadership self-efficacy to enhance individual efficiency and accomplish organizational goals. Leadership self-efficacy is defined as a leader’s appropriate role and the confidence of self-schematic in a leader’s perceived capabilities to develop psychological motivations, abilities, and behaviours required to achieve effective performance within the domain of leadership (Zaman et al., 2022). Leadership self-efficacy decides what challenges leaders confront, how they face the challenges, and how they resolve the difficulties and obstacles (Brinkmann et al., 2021). Leadership self-efficacy not only affects an individual’s effort and persistence but also influences one’s leadership activities. Leadership self-efficacy may bring the leadership structure of the leader to the desired style of leadership, performance standard, and organizational expectation.

After promoting individual leadership self-efficacy, E-commerce managers could achieve their individual and organizational commitment. Commitment is described as the setting of an individual who is seeking a desired goal. According to Morrow and Wirth (1989, p. 41), commitment is defined as “the relative strength of identification with and involvement in one’s profession.” In this research, commitment is indicated as an affective attachment to the organizational goals (Klein et al., 2022).

The motivation of this study is to investigate the interrelationships among the personality, transformational leadership, leadership self-efficacy, and commitment of E-Commerce administrative managers. By applying the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and the Structured Equation Modelling (SEM) methods, this study verifies the following four results: (1) a manager with Big Five personality traits has a positive influence on transformational leadership. (2) An E-commerce administrative manager with the Big Five personality traits has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy. (3) A manager with transformational leadership has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy. (4) An E-Commerce administrative manager with leadership self-efficacy has a positive influence on commitment.

1.1 The Research Model

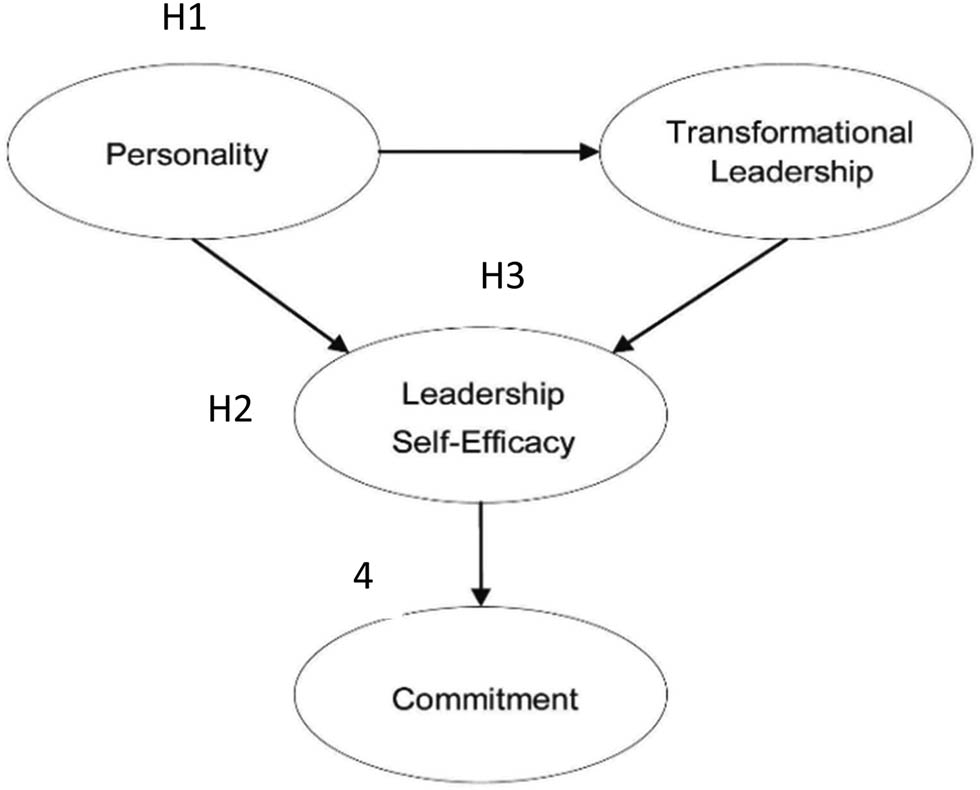

As shown in Figure 1, the research model describes the interrelationships among personality, transformational leadership, leadership self-efficacy, and commitment for E-Commerce administrative managers. In this study, mediation analysis is used to test the mediating effects among independent variables, dependent variables, and mediating variables in the following categories: (1) transformational leadership is employed as a mediator between personality and leadership self-efficacy. (2) Leadership self-efficacy is applied as a mediator between personality and commitment. (3) Leadership self-efficacy is applied as a mediator between transformational leadership and commitment. Based on the research model, four hypotheses are described as follows:

Research Model.

Hypothesis 1

A leader with Big Five personality traits has a positive influence on transformational leadership.

Hypothesis 2

A leader with the Big Five personality traits has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 3

A leader with transformational leadership behaviours has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 4

A leader with leadership self-efficacy has a positive influence on commitment.

Some limitations of the proposed model are as follows: First, the four main variables of the model are not applicable to all administrative managers and industries. Because the variable of the proposed model is designed for E-Commerce administrative managers, not applicable to managers in other industries. Second, due to the cultural difference, the four variables may lead to cognitive differences in beliefs, behaviours, languages, practices, and expressions in different countries. Third, Western and Eastern ideas of leadership were the balance between individualism and collectivism. Leaders in the East often placed a much heavier emphasis on the collective, articulating high levels of commitment to their leader and the organization. Moreover, limited by research groups and numbers, the study model couldn’t be applicable to all similar leadership research studies. Thus, the above limitations may restrict future research direction and findings.

1.2 The Originality of this Research

The research provides new evidence on the positive relationships among personality, transformational leadership, leadership self-efficacy, and organizational commitment for the E-Commerce administrative managers. This study verifies that personality and the transformational leadership of E-Commerce administrative managers play essential roles in enhancing leadership self-efficacy. This study also examines that leadership self-efficacy has a direct effect on organizational commitment. Those research results will contribute to evaluate the performance model of E-Commerce administrative managers by applying their personalities and transformational leadership to enhance leadership self-efficacy and increase the level of organizational commitment. This research could be a better reference for E-commerce corporations to construct the evaluation model of administrative managers’ performance and achieve organizational accomplishment by enhancing managerial leadership.

2 Literature Review

According to the above research model, the four key factors are discussed in the following categories: (1) personality, (2) transformational leadership, (3) leadership self-efficacy, and (4) commitment.

2.1 Personality

Each person has a different personality that is totally unique and cannot be duplicated by another person (Bakker et al., 2021). Ones et al. (2021, p. 390) defined personality as “a spectrum of individual attributes that consistently distinguish people from one another in terms of their basic tendencies to think, feel, and act in certain ways.” James and Mazerolle (2002, p. 1) Indicated personality as “dynamic mental structures and coordinated mental processes that determine individuals’ emotional and behavioural adjustments to their environment.” The vocabulary of personality was applied in the dictionaries as a natural language that “provides an extensive, yet finite, set of attributes that the people speaking that language have found important and useful in their daily interactions” (Goldberg, 1981, p. 3). Personality is considered as a disposition motive that predisposes individuals to behave in a particular way and accomplish specific goals (Anglim et al., 2020). An individual personality is cultivated from the cradle and shaped mostly by individual past experiences (Neneh, 2019). Personality is most affected by human instinct that indicates a personal psychological condition, such as individual personality, motive, competence, attitude, evaluation of a social phenomenon, and recognition of the universe and life. Personality refers to the reflection of individual characters when a person adapts to the changes in the surrounding environment (Smiderle et al., 2020). Pierce and Gardner (2002) indicated two determinants of personality that have been termed “nature” and “nurture.” Nature represents that personality is inherited at birth and shaped mainly by heredity. However, there are many arguments that suspect that personality is stable for a long period of time. Epstein (1979) proposed a strong demonstration that the stability of personality increases when behavioural measurements are averaged over continuing and racing events. Personality is concluded as “reasonably consistent over time” by Buss (1991). Ryan and Kristof-Brown (2003) proposed that personality is fairly stable in the adult phase and considered personality is partly influenced by genes. On the other hand, many researchers verified that an individual personality is partly influenced by one’s surrounding environment (Costantini et al., 2019). However, a large number of personality traits aren’t needed to understand the real role of personality in the domain of organizational behaviour.

2.1.1 Big Five Model

Thousands of research studies about personality traits have been studied for a long time. Those studies were not productive and difficult to validate what the personality traits should focus on. The original concept of Big Five personality could be traced to the research of psychologist Douglas who indicated the denominations of “Character and Personality” in the Journal of Personality (William, 1932). Allport and Olbert (1936) generalized the personality terms into four categories: (1) stabilized and consistent states; (2) temporary tendencies; (3) high evaluation of personal reputation; and (4) physical talents and capabilities. Hothersall et al. combined Allport and Olbert’s first and last categories into the term “traits” and distilled into 35 variables (Hothersall & Lovett, 2022). Fiske proposed five key factors by referring to Cattell’s 35 variables (Fiske, 1949). Tupes and Christal verified a framework of five-factor model by analysing other related research (Tupes & Christal, 1961). Norman categorized the five factors as (1) Extraversion; (2) Agreeableness; (3) Conscientiousness; (4) Emotional Stability; and (5) Culture (Norman, 1967). The name “Big Five” was stated because those five traits represented broad and abstract levels of personality (Goldberg, 1981). However, since the 1990s, the studies of personality traits have been accepted and all of those studies have been summed up into the theory of “Big Five.” McCrae and Costa indicated the last factor “Culture” as openness or openness to experience (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Goldberg (p. 1217) started to develop factor analytic research and proposed the “Big Five” Personality Model in order as follows: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Culture (Goldberg, 1990). Lussier categorized the “Big Five” factors as (1) Extraversion, (2) Agreeableness, (3) Adjustment, (4) Conscientiousness, and (5) Openness to Experience (Lussier, 2000). Pierce and Gardner indicated the “Big Five” Model (BFM) as (1) Extraversion, (2) Agreeableness, (3) Adjustment, (4) Conscientiousness, and (5) Inquisitiveness (Pierce & Gardner, 2002). Many research studies on personality were conducted and have been studied mainly in five dimensions that are mentioned as the Five-Factor Model (FFM), Big Five Model (BFM), or the Big Five Personality Traits (BFPT; Digman, 1996). Although many personality models were adopted to identify the domain of personality traits, the validity of most personality models to testify the personality traits was quite low (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Until the appearance of the Big Five Model, which provides five dimensions of personality traits, could formulate a reasonable framework of personality and test a meaningful relationship between personality and transformational leadership (Wiggins, 1996). As the most proper measurement instrument, the Big Five Model was supported for classifying the attributes of personality traits (Mount et al., 1998). Even though some personality psychologists suggested that the domains of personality were required to add more than five factors, the generality of the Big Five Model has been accepted by most personality researchers.

The adjectives describing the “Big Five” Personality Traits are briefly listed in Table 1.

Descriptions of the “Big Five” Personality Traits (Abujarad, 2010)

| Personality trait | Lower pole | Higher pole |

|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | Introverted, Silent, Pessimistic, Timid | Assertive, Enthusiastic, Optimistic, Gregarious |

| Agreeableness | Unkind, Selfish, Belligerent, Rude | Kind, Cooperative, Flexible, Polite |

| Conscientiousness | Negligent, Reckless, Forgetful, Inconsistent | Responsible, Dependable, Cautious, Efficient |

| Emotional Stability | Fear, Instable, Intrusive, Envious | Relaxed, Stable, Independent, Calm |

| Openness | Unintelligent, Stupid, Imperceptive, Shallow | Intelligent, Analytic, Perceptive, Imaginative |

To clarify the meaning of the five traits, this study focuses on Goldberg’s “Big Five” Personality Traits and categorizes the five personality factors as a Big Five Model (BFM), including (1) extraversion, (2) agreeableness, (3) conscientiousness, (4) emotional stability, and (5) openness (Goldberg, 1990). The Big Five Model has been gaining the most agreed frameworks for personality traits (Costa & McCrae, 1992a,b).

2.1.1.1 Extraversion

An individual with the personality of extraversion is prone to enjoy spending time on human interaction and participating in large social activities. An individual with the trait of extraversion is inclined to be gregarious, sociable, and energetic. According to the same perspective, individuals with the personality of extraversion are more likely to navigate social activities, pursue their hierarchical statuses, and accomplish their personal successes (Depue & Collins, 1999). Individuals with the personality of extraversion would like to engage in the activities of establishing relationships with others (Wilmot et al., 2019). Based on the Big Five Model proposed by Barrick and Mount, extraversion expresses the inclination to be “sociable, gregarious, assertive, talkative, and active” (Barrick & Mount, 1991, pp. 3–4). Extroverted people have the tendency of self-assertive and energetic. Those people are eager to search for positions of power, authority, and prestige where they like to dominate and guide others with self-confidence. In contrast, introverted people have the inclination to lose energy when being involved in crowded groups and therefore they would like to spend more time to leave themselves alone than extroverted people.

2.1.1.2 Agreeableness

The trait of agreeableness refers to the inclination to be amiable, empathic, lenient, honest, moral, and modest (Goldberg, 1990). To maintain a certain social position, an individual should not only recognize hierarchical positions but also engage in interactive alliances through the personality of agreeableness. Individuals with the personality of agreeableness are inclined to cope with interpersonal conflict and search for common understanding effectively through collaborative alliances (Vize et al., 2021). Based on the Big Five Model proposed by Barrick and Mount (1991), agreeableness expresses the inclination to be “courteous, flexible, trusting, good-natured, cooperative, forgiving, soft-hearted, and tolerant” (pp. 4–5). People with high degrees of agreeableness are easy to get along with others with natures of being courteous, forgiving, tolerant, compassionate, good-natured, and soft-hearted.

2.1.1.3 Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness refers to the characteristic of diligence and deliberation based on one’s self-discipline and conscience (Lawson & Kakkar, 2022). Atwater and Yammarino proposed that personality characteristic was used to assess an individual’s reputation that would influence the personal social position and acceptance (Atwater & Yammarino, 1993). An individual who has the trait of conscientiousness is usually reliable and deliberate in society. According to the Big Five Model proposed by Barrick and Mount (1991), conscientiousness expresses the inclination to be “dependability, careful, thorough, responsible, and organized” (p. 4). An individual who is reliable in an organization has more chance to get promoted, attain higher social status, and even become a leader. The trait of conscientiousness comprises both main characteristics, dependability representing being persistent, cautious, dependable, and responsible, and accomplishment reflecting individual capability to work laboriously and challenge the hardship (McCrae & Costa, 1987; Mount et al., 1998). An individual with higher levels of conscientiousness is inclined to be considerate before action and to be persistent in personal responsibility and obligation (Costa & McCrae, 1992a). The personality of conscientiousness regards the domain of work rather than the relationship with others.

2.1.1.4 Emotional Stability

Emotional stability refers to the trait of enduring inclination as an individual suffers a negative emotional status, such as anxiety, depression, and misery (Caliskan, 2019). The opposite of emotional stability, neuroticism, expresses the tendencies to be afraid, unsecured, unstable, gullible, stressed, impulsive, and intrusive (McCrae & Costa, 1987).

An individual with a high level of neuroticism is inclined to be anxious, stressed, and impulsive, and therefore, is hard to be perceived as a leader (Yang et al., 2020). On the basis of the Big Five Model proposed by Barrik and Mount (1991), neuroticism represents the inclination to be “anxious, depressed, angry, embarrassed, emotional, worried, and insecure” (pp. 3–4). Based on a meta-analysis, neuroticism has a negative influence on leadership emergence (Friedman, 2019). Social learning theory proposed by Bandura indicates that an individual with the trait of neuroticism has a lower confidence in his/her own ability, and therefore, is less likely to be recognized as a leader to conduct others (Bandura, 1986).

2.1.1.5 Openness

Openness is defined as the tendency of a liberal attitude that demonstrates the extent of an individual’s receptivity to new cultures, organizations, and environments (Gokhan & Mutlu, 2019). Openness is also called “openness to experience,” which is described as an individual initiative characteristic to accept new concepts or cultures with a positive motivation to change and an attitude towards learning new experiences (Li et al., 2021). The Big Five Model proposed by Barrick and Mount (1991) openly expresses the inclination of being “imaginative, cultured, curious, original, broad-minded, intelligent, and artistically sensitive” (pp. 4–5). An individual with the characteristic of openness is inclined to have less prejudiced views that are beneficial for one to assess and solve problems objectively. Accordingly, those who have a higher level of openness trait are prone to benefit from accepting change (Guo et al., 2021).

2.2 Transformational Leadership

The terminology of transformational leadership was first proposed by Downton as the assumption that a person inspires followers to achieve the desired goal with enthusiasm and innovation (Downton, 1973). Burns described transformational leadership as “occurs when one or more persons engage with others in such a way that leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality” (Burns, 1982, p. 20). Bass and Riggio’s defined transformational leadership as “inspires followers to commit to a shared vision and goals for an organization or unit, challenges them to be innovative problem solvers, and develops followers’ leadership capacity via coaching, mentoring, and provision of both challenge and support” (Bass & Riggio, 2006, p. 4). The objective of transformational leadership is to motivate the morality of followers and to enhance the maximum happiness of organizations by stimulating the followers’ vision and facilitating the process of change (Burns, 1978). Transformational leaders are like “architects” who recognize the requirement for change, create new ideas, and construct the expected visions (Paulsen et al., 2013). Tichy and Ulrich indicated that transformational leaders were capable of reconciling disputes in the process of change and encouraging followers to engage in their enthusiasm (Tichy & Ulrich, 1984). Transformational leaders have the capability to guide their followers in the following categories: (1) goal clarification, (2) risk-taking allowance, (3) error tolerance, and (4) creativity encouragement (Bennis, 1989). Transformational leaders devote strong emotions to their followers (Muliati et al., 2022); in contrast, followers are committed to achieve the assigned missions with the full trust of their leaders (Bennis & Nanus, 1985). In the process of refreshing followers’ vision, leaders are allowed to accept change, which is considered a catalyst to increase follower’s competitiveness and sustainability (Marshall, 2000). Transformational leaders have the responsibility to enhance followers’ ethical values by strengthening follower’s moral standards and driving them to achieve higher organizational goals (Bass & Jung, 2003). Transformational leadership strengthens the relationship between leader and follower by consolidating mutual trust and commitment (Jung & Avolio, 1999). Furthermore, leaders and followers are allied to be involved in a common desired goal by which transformational leaders are inclined to facilitate higher achievement than other leaders do (Avolio & Yammarino, 2002). The objectives of transformational leaders are associated with the concepts of social responsibility and public welfare instead of leaders’ self-interests (Görgens-Ekermans & Roux, 2021).

According to Bass and Avolio, this research classified transformational leadership into the following four categories: (1) idealized influence, (2) inspirational motivation, (3) intellectual stimulation, and (4) individualized consideration, which are generally abbreviated as the “Four I’s” by most researchers (Messick, 2021).

2.2.1 Idealized Influence

Idealized influence is described as transformational leaders being prone to be respected and trusted, and followers’ desirable behaviours are modulated in response to leaders’ guidance through emulation of their leaders (Bass, 1985). According to Bass’s research, idealized influence was defined as leaders who “behave in ways that result in their being role models for their followers” (Bass, 1996, p. 5). The idealized influence was described as leaders performing their valuable beliefs, thinking over their moral influence of decisions, and achieving the collective goals (Messick, 2021). Transformational leaders’ ethical standards of behaviours are recognized as role models of their followers (Mathende & Karim, 2022). Transformational leaders are trusted to interact with their followers by using their talents, persistence, and determination. Relatively, followers accept leaders and hope to emulate their leaders as role models. In the process of transformational leadership, leaders have to take a risk of handling the interactive issues with followers. The fundamental values of transformational leaders rely on principle-based management with the orientation of moral elevation rather than being despotic and bloody leaders (Burns, 1978). Idealized influence is value-based leadership by which leaders could enhance organizational ethical values and policies (Kariuki et al., 2022).

2.2.2 Inspirational Motivation

Inspirational motivation is indicated as followers are motivated to drive out any difficulties and achieve goals in their working environments based on the provision of guidance and inspiration (Bass, 1985). According to Bass, inspirational motivation is defined as transformational leaders who “behave in ways that motivate and inspire those around them by providing meaning and challenge to their followers’ work” (Bass, 1996, p. 9). Inspirational motivation is proposed as transformational leaders motivating their followers with optimistic descriptions of future visions, enthusiastic explanations about the desired accomplishments, and strong confidence about the achieved goals (Messick, 2021). By means of a leader’s enthusiasm, optimism, and motivation, transformational leaders actively communicate with their followers to construct a new future vision and higher expectations for the desired goals within the organization (Bass & Avolio, 1990). Through communication, followers are inspired to be involved in the transformational process and committed to achieve desired goals and new visions.

2.2.3 Intellectual Stimulation

Intellectual stimulation is described as transformational leaders stimulating their followers’ endeavours to be created through the efforts of assumptions challenge, situation restructuring, and problem solution in an innovative working environment (Bass, 1985). According to Bass, Intellectual stimulation is defined as transformational leaders who “show their intellectual capacity by stimulating their followers’ efforts to be innovative and creative by questioning assumptions, reframing problems, and approaching old situations in new ways” (Bass, 1996, p. 10). Followers are stimulated by leaders’ perspective encouragement to achieve mutually expected goals. Leaders with the style of intellectual stimulation are inclined to provide followers with new visions and ideas, which are accepted by followers to modify their original behaviours and ways of handling things (Bass & Avolio, 1990). In the context of intellectual stimulation, leaders are inclined to persuade followers to be consistent with their values. Genuine intellectual stimulation leads to the consistency between leaders’ values and followers’ benefit by substituting the argument for reasonable discourse (Khan et al., 2022). Conversely, leaders with fake intellectual stimulation are prone to be narrow-minded and cannot put up with odd ideas between leaders themselves and their followers (McCombs & Williams, 2021). Because followers are used to abide by the traditional and hierarchical ways, transformational leaders are expected to change followers’ original ideas by creating new ideas and providing problem solutions. Moreover, followers affected by a leader’s intellectual stimulation are aroused in the ways of problem awareness, thought initiation, belief recognition, and value judgment (Yammarino & Bass, 1990).

2.2.4 Individualized Consideration

Individualized consideration is indicated as transformational leaders pay attention to followers’ need and accompany their growth with leaders’ mentoring and tutoring. On the basis of individual consideration, leaders and followers interact by mutual implication of agreements and communications (Bass, 1985). Bass encouraged two-way communication where leaders listen to followers’ individual needs considerately (Bass, 1996). According to Bass, individual consideration is explained as transformational leaders who notice each follower’s demand for individual achievement by playing the role of mentor (Bass, 1996). Leaders with the tendency of individual consideration are more likely to meet followers’ needs by strengthening their interactions with their followers and developing a higher degree of followers’ potential (Alderfer, 1972). Leaders are inclined to understand followers’ desires and requirements by providing full learning support. Accordingly, followers are encouraged to enhance the higher degree of their capabilities and achieve organizational desired goals. The application of leaders’ individualized considerations contributes followers to achieving their higher level of potential capability (Yammarino & Bass, 1990). Based on coaching and mentoring, transformational leaders realize followers’ needs and provide continuing feedback and responses to carry out the assigned organizational missions (Bass & Avolio, 1990).

2.3 Leadership Self-Efficacy

Leadership self-efficacy is described as a leader’s belief by which a leader can display his/her own behaviours effectively for a certain required task (Gist, 1987). A leader with the concept of leadership self-efficacy is anticipated to obtain a higher level of task performance (Rabiul et al., 2022). Leadership self-efficacy is an essential factor in the arena of organizational behaviour (Jonsson et al., 2021). According to Bandura, leadership self-efficacy was proposed as “judgments of how well one can execute courses of action required to deal with prospective situations” (Bandura, 1982, p. 122). The definition of leadership self-efficacy was provided by Bandura (1986, p. 391) as “judgments of capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designed types of performance.” Later, Baudura expanded the definition of self-efficacy as “beliefs in their capabilities to mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources, and courses of action needed to exercise control over task demands” (Bandura, 1990, p. 316). Thus, leaders not only possess task-related skills but also have to build the self-assurance belief required to control surrounding events and accomplish expected goals. Gist and Mitchell proposed three traits of leadership self-efficacy: (1) representing the judgments of perceived abilities to perform particular tasks with three assessments of the following categories: assessment of task condition, assessment of experience attribution, and assessment of personal resources; (2) showing the tendencies of being dynamic and adjustable; (3) displaying the identity of mobilization (Gist & Mitchell, 1992). Gist suggested that self-efficacy included three components: (1) magnitude, (2) generality, and (3) strength (Gist, 1987). First, the magnitude is described as “the level of task difficulty that a person believes he or she can attain” (Gist, 1987, p. 472). Second, generality indicates the degree to whether judgments are generally applied in all ranges of activities (Bandura, 1997). Strength is defined as “the resoluteness of a person’s conviction that he or she can perform a behaviour in question” (Maddux, 1995, p. 9).

This study broadens the definition of leadership self-efficacy as a leader’s appropriate role and the confidence of self-schematic in a leader’s perceived capabilities to develop psychological motivations, abilities, and behaviours required to achieve effective performance within the domain of leadership (Bandura, 1997). Leadership self-efficacy may bring the leadership structure of the leader to the desired style of leadership, performance standard, and organizational expectation (Lin et al., 2022). Bandura examined that both self-reflection and self-evaluation contribute to a person’s degree of self-efficacy, which is an essential factor in developing one’s leadership self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997).

2.4 Commitment

Commitment is described as the setting of an individual who is seeking a desired goal (Mihalache & Mihalache, 2022). According to Morrow and Wirth (1989, p. 41), commitment is defined as “the relative strength of identification with and involvement in one’s profession.” Based on the specific goals, leaders would attach themselves to what they want to attain. Meyer and Herscovitch indicated commitments as the following three types: (1) being affective where an individual desires to attain goals; (2) being normative where an individual has the sense of obligation to motivate people; (3) being persistent where an individual has a continuation of consequences to do certain things (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). Thus, commitment has relatively long-lasting implications for goal-oriented attainment (Zhang et al., 2022).

2.5 Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

Many researchers attempted to recognize the correlation between personality and transformational leadership. Bass (p. 122) stated, “Personality disposition has been correlated with transformational leadership concurrently, retrospectively, and as forecasts of transformational leadership” (Bass, 1998). Judge and Bono examined that three factors of the Big Five personality traits were positively related to transformational leadership, including extraversion, agreeableness, and openness (Judge & Bono, 2000). Although the other two Big Five factors, emotional stability, and conscientiousness, didn’t have a significant correlation with transformational leadership, the overall results of Big Five personality traits could accurately predict the behaviours of transformational leadership (Judge & Bono, 2000). Organizations could benefit from choosing excellent transformational leaders based on the selection of the leader’s appropriate personality traits.

2.5.1 Big Five Personality Traits and Transformational Leadership

According to the Big Five Model (BFM), the relationships between Big Five personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness) and transformational leadership are discussed in the following sections.

2.5.1.1 Extraversion and Transformational Leadership

Extraversion trait reflects the strongest tendency of articulation that is the main component of transformational leadership. Based on the effective articulation of a leader’s insight, extrovert leaders could influence the views of their followers and conduct them to reach higher levels of organizational desired goals and group commitment. Through efficient inspirational motivation, another key factor of transformational leadership, extrovert leaders usually could express higher expectations and communicate with subordinates in an efficient way. In contrast, subordinates are more likely to internalize group expectations through a leader’s motivation, one main component of an extraversion trait (Li et al., 2022). As a subordinate’s value concept is identical to that of extravert leaders, they are looking forward to shift their viewpoint from self-centred interests to the collective interests of their organizations. Thus, leaders with a higher degree of extraversion trait are able to minimize subordinates’ resistance to change and achieve the desired goals for their organizations (Fazli-Salehi et al., 2022).

2.5.1.2 Agreeableness and Transformational Leadership

Leaders with a higher degree of agreeableness are easy to make friends and always have a crowd of friends by being warm and approachable. Contradictorily, leaders with the lower agreeableness trait are generally hard to establish close relationships with other leaders and subordinates by being unkind, cold, and distant. Ross and Offerman indicated that leaders with the inclination of agreeableness are more likely to be considerate and sympathetic to the requirements of their subordinates (Ross & Offerman, 1991). Leaders express their concerns for subordinates’ demands, representing the main factor of transformational leadership, consideration personality traits. On the contrary, subordinates reflect respectful attitudes to their leaders in response to their agreeable leaders’ approachable behaviours (Dhakal et al., 2022). The interactive behaviours between leaders and subordinates represent that the agreeableness trait is most closely correlated with charisma, the main component that has the strongest relationship with transformational leadership (Bellibaş et al., 2021). Black indicated that the personality of agreeableness was related to a leader’s interpersonal adjustment in social relations (Black, 1990). The higher the extent of agreeableness, the more likely leaders would have a greater adjustment by dealing with their social relationships effectively within an organization. Leaders with the personality of agreeableness are more likely inclined to have higher levels of leadership through collaborative relations (Suprapto et al., 2022).

2.5.1.3 Conscientiousness and Transformational Leadership

In fact, many entrepreneurs possess a higher degree of conscientiousness in the occupational place. Leaders with personality conscientiousness are more likely to gain their reputations in the workplace. Leaders with the characteristic of conscientiousness would be more likely to obtain a good reputation in a working environment. Thus, the higher the reputation they obtain, the more likely leaders would achieve greater adjustment effectively. Barrick and Mount (1991) proposed that the personality of conscientiousness was positively related to job performance through the traits of deliberation. Therefore, leaders with a higher extent of conscientiousness are expected to have higher job performance in a working environment.

2.5.1.4 Emotional Stability and Transformational Leadership

Leaders whose personalities are high in emotional stability are inclined to handle pressure and stress from other’s criticism. In contrast, leaders who are low in emotional stability tend to be depressed, anxious, and stressed. Leaders are usually accompanied by a high degree of stress as they are unable to deal with their personal problems in an unfamiliar working environment (Giannotti et al., 2022). Leaders’ incapability to handle the great stress of enterprise’s assignment might trigger problems from other’s criticism and pressure (Abdi et al., 2022). The trait of emotional stability is a crucial personality for leaders to modify their attitudes in an unfamiliar working environment effectively.

2.5.1.5 Openness and Transformational Leadership

Leaders with the dimension of openness generally have a broad extent of interest in accepting new ideas and tend to deliberate new thoughts from others. Leaders associated with openness trait usually incorporate new ideas and accept arguments from superiors or subordinates when their ideas differ from others. Furthermore, these leaders who have openness traits are more inclined to encourage their subordinates to challenge existing regulations and accept new handling models. Leaders with higher dimensions of openness are intellectually curious and usually search for new experiences with others through surrounding activities. The trait of openness is important for leaders to solve the problems of cultural adjustment through the processes of perceiving, participating, and implementing. In a complicated working environment, it is more difficult for leaders to assess problems accurately, given limited resources and unpredictable events. In such a complex environment, leaders should possess the trait of openness to handle ambiguous situations and solve the problems effectively. Ones et al. suggested that leaders with the characteristic of openness would be more likely to accept new enterprise cultures and values in new working environments (Ones et al., 2021). Therefore, Judge and Bono demonstrated that the trait of openness has a significantly positive correlation with transformational leadership (Judge & Bono, 2000). Therefore, the following hypotheses are described:

Hypothesis 1

A leader with Big Five personality traits has a positive influence on transformational leadership.

2.5.2 Big Five Personality Traits and Leadership Self-Efficiency

Wooten demonstrated that individual personality characteristics are significantly related to leadership self-efficacy in a task-related environment (Wooten, 1991). Because an individual past experience and the perceptions of others’ experiences may be influenced by personality traits, it is possible that personality will influence self-efficacy partly or mostly. A successful task-related performance depends upon an employee’s strong belief, which is an essential component of personality traits that would affect one’s self-efficacy. The relationships between Big Five personality and leadership self-efficacy are explored in the following sections.

2.5.2.1 Extraversion and Leadership Self-Efficacy

Extraversion is indicated as the tendency to be sociable, enthusiastic, and energetic. Individuals with the personality of extraversion are inclined to participate in social activities and communicate with others (Li et al., 2022). Individuals with the personality of extraversion are more likely to engage in the activities of establishing relationships with others who master the main resources within the group. Barrick and Mount (1991) proposed that the trait of extraversion is a valid predictor for effective management, which needs to interact with others and build close social relationships. Individuals with higher degrees of arousal are examined to have higher degrees of self-efficacy (Agbaria & Mokh, 2022). People with the trait of arousal are prone to have higher energy, which is strongly related to extraversion. Therefore, individuals with the trait of extraversion are expected to have higher degrees of self-efficacy through their abilities to perform the required tasks with social interaction and self-assertiveness.

2.5.2.2 Agreeableness and Leadership Self-Efficacy

The trait of agreeableness is described as the inclination to be cooperative, courteous, empathic, lenient, honest, moral, flexible, and modest. Stevens and Campion proposed 10 KSAs, called “Interpersonal Strategy” that effective leaders are based on interacting well with others through the use of an integrative negotiation strategy (Stevens & Campion, 1994). Wellins, Byham, and Wilson suggested that leaders with the trait of agreeableness are required to have the following tendencies: opinion request, assistance provision, suggestion acceptance, needs consideration, motivation stimulation, problem solution, comment consideration, and idea recognition (Wellins et al., 1991). Leaders with the trait of agreeableness are inclined not only to communicate with group members but to obtain trust and morale from their followers. Those leaders who obtain trust from their followers are inclined to achieve the desired goals through the cooperation between leaders and followers. It is predicted that individuals with higher levels of agreeableness are more likely to have higher levels of self-efficacy through the related above behaviours of agreeableness.

2.5.2.3 Conscientiousness and Leadership Self-Efficacy

Conscientiousness is described as the tendency to be dependable, responsible, cautious, and efficient. Effective leaders need to possess the desired ability to establish task regulation, face challenges, accept adjustments, and evaluate the employee’s performance (Stevens & Campion, 1994). Leaders with the trait of conscientiousness are required to have the following characteristics: achievement orientation, detailed consideration, action orientation, and perceived urgency, all of which are essential components of self-efficacy (Xu et al., 2021). The dimension of conscientiousness is the indicative index of responsible and efficient people who are required to possess these desirable traits and perform the desired tasks effectively. Conscientiousness is examined as a valid predictor of performance and the criterion of job-related management (Postigo et al., 2021). Barrick and Mount examined that autonomy is a moderator of the relationship between conscientiousness and job-related performance (Barrick & Mount, 1993). Individuals with higher levels of conscientiousness are inclined to have higher levels of autonomy, which allows people’s latitude to determine the desired behaviours. Leaders with higher levels of autonomy are inclined to develop their performances effectively and reach higher levels of self-efficacy. Based on past abundant experience, leaders with higher levels of conscientiousness are more likely to have higher levels of self-efficacy.

2.5.2.4 Emotional Stability and Leadership Self-Efficacy

Emotional stability is indicated as an individual emotional degree of anxiety, self-confidence, optimism, inspiration, and felicity. Catino proposed that the trait of emotional stability required by transformational leaders is related to the effectiveness of leadership (Catino, 1992). Pettersen suggested that the traits of emotional stability, maturity, and self-confidence are required by leaders to achieve the desired goals of project teams (Pettersen, 1991). Larson and LaFasto demonstrated that empowered leaders need to have the traits of maturity and self-confidence, and possess higher levels of tolerance under surrounding pressure (Larson & LaFasto, 1989). Moreover, the trait of emotional stability is an essential factor in maintaining steady under stress, handling negative responses, and resolving conflict (Utami et al., 2021). Gist and Mitchell suggested that individuals with a higher degree of emotional stability are more likely to have self-confidence in their abilities to perform the required tasks effectively (Gist & Mitchell, 1992). An individual with higher self-confidence may have higher self-efficacy in a variety of tasks. Thus, individuals with a higher level of emotional stability are more likely to have a higher degree of self-efficacy. According to social learning theory, neuroticism is negatively related to self-efficacy (Streit et al., 2022). Relatively, emotional stability has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy.

2.5.2.5 Openness and Leadership Self-Efficacy

Openness is also called “Openness to Experience” or “Intellect,” including the tendencies of being open-minded, imaginative, and insightful. Individuals with the trait of openness are required to have the capability to deal with ambiguity. In a new working environment, leaders with higher openness are required to have the inclination of being creative and open-minded to set desired goals, solve problems, and settle conflicts (Stevens & Campion, 1994). Catino proposed that the tendency of creativity is an essential factor of self-efficacy. Leaders are required to have the tendency to be open to change and being created to deal with ambiguity (Catino, 1992). Individuals with higher levels of openness are inclined to have higher levels of self-efficacy. Therefore, hypothesis 2 is formulated as below:

Hypothesis 2

A leader with the Big Five personality traits has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy.

2.5.3 Transformational Leadership and Leadership Self-Efficacy

Transformational leadership is referred to as “an absolute emotional and cognitive identification” (Bass, 1988, p. 50) and relies on leaders’ success to connect the conception of followers’ identity with the goals of their organizations (Kark & Shamir, 2002). Moran et al. described leadership self-efficacy as an individual’s capability to accomplish work-related tasks or achieve a desired goal of the organization. In the self-concept motivation theory of leadership, Shamir, House (Moran et al., 2021), and Purwanto et al. proposed that transformational leadership positively influenced leadership self-efficacy through emphasis on positive perception, expectation of higher performance, and confirmation of followers’ capabilities to achieve the desired goals of organizations (Purwanto et al., 2021). Mach indicated that transformational leaders construct their followers’ concepts of leadership self-efficacy by understanding followers’ visions and providing sufficient feedback for their followers (Mach et al., 2022). In such a transformational activity, transformational leaders are inclined to help followers believe that they can successfully overcome the oncoming challenges of transforming the self-concepts of leaders. In addition, transformational leaders can enhance their followers’ self-efficacy by presenting the following two main components of self-efficacy: role modelling and verbal persuasion (Bass, 1998). Transformational leaders can influence their followers’ behaviours to engage in work-related tasks successfully by providing adequate references and ideal points for their followers. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated as below:

Hypothesis 3

A leader with transformational leadership behaviours has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy.

2.5.4 Leadership Self-Efficacy and Commitment

Transformational leaders would enhance their leadership self-efficacy by finding a feasible solution for the problem. As leadership self-efficacy is established, followers will enhance their trust and commitment to the leaders and organizations. By motivating followers to maintain access to the organization and making individual sacrifices, leaders may enhance their followers’ commitment towards a group goal (Yukl, 1998). Transformational leaders identify the group vision and commit to collective interests, which may bring the desired commitment. Therefore, transformational leaders with a high degree of self-efficacy are motivated to have a higher level of commitment within an organization. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 4

A leader with leadership self-efficacy has a positive influence on commitment.

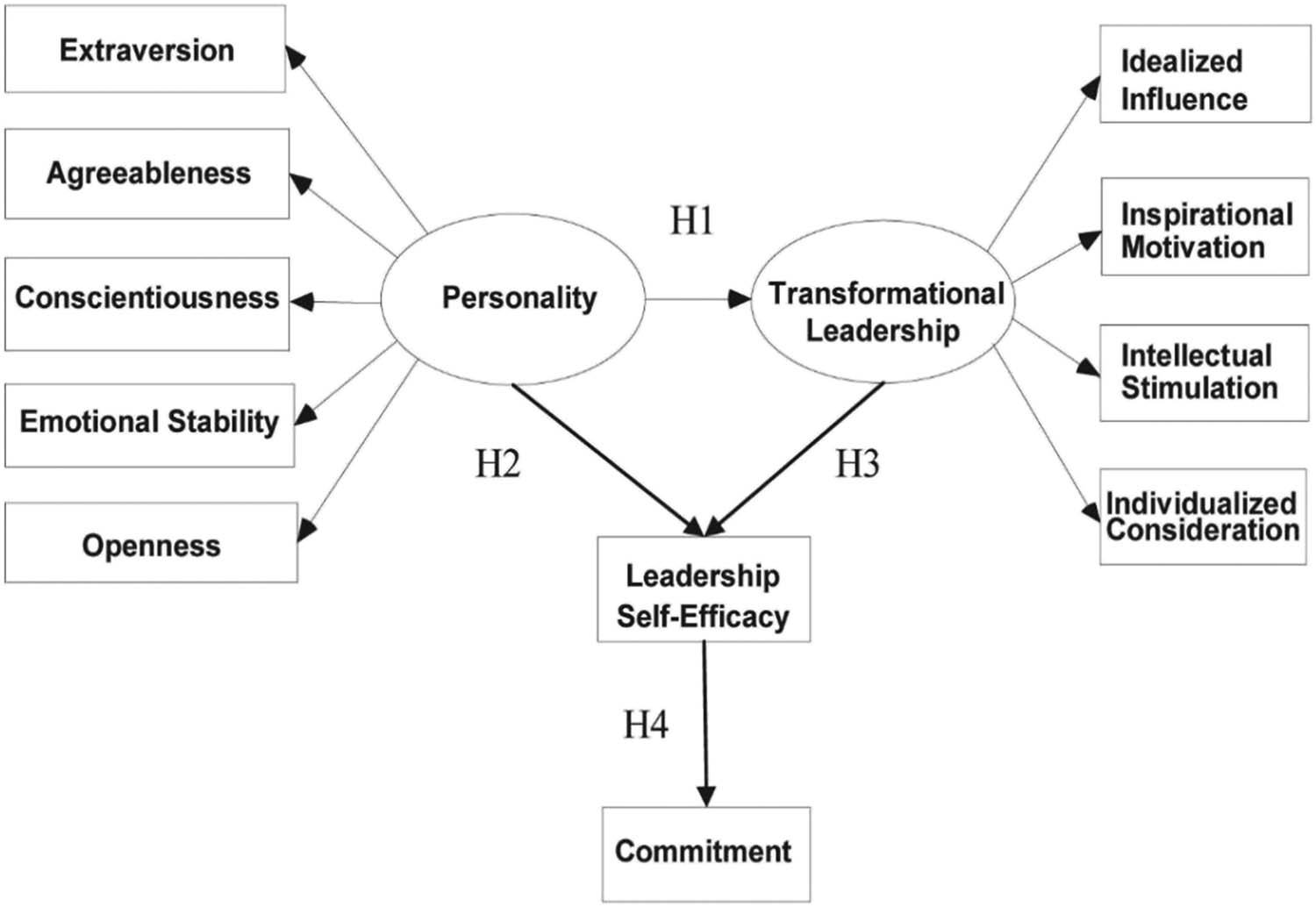

Based on the above hypotheses, the conceptual framework of this research is shown in Figure 2.

Conceptual framework.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research Design

Quantitative research design is applied in this study. The statistical software, Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) and Analysis of Moment Structure (AMOS) Graphics, version 28.0.1, is applied to examine the causalities among all research variables in this study. The Structured Equation Modelling (SEM) method, a multivariate technique, is used to estimate a series of interrelated dependent relationships simultaneously in this research. The Goodness-of-Fit (GOF) induces is employed to examine the overall fitness of the SEM model. In this study, the eight most frequently used GOF statistics induces are applied as the following items: (1) Normal Chi-Square Index (NCI) expressed as χ2/df, the ratio of χ2 to degrees-of-freedom. NCI provides information related to chi-square indices and their use in structural equation modelling; (2) Goodness-of-Fit index (GFI) is a measure of fit between the hypothesized model and the observed covariance matrix; (3) Normalized Fit Index (NFI) is a normalized measure, which means it removes the units of measurement, making it easier to compare the fit of different models across various datasets. Higher NFI values indicate a better fit, with values closer to 1 suggesting a more accurate representation of the observed data by the model; (4) Non-Normalized Fit Index (NNFI) is designed to evaluate how well a proposed model fits the observed data. Unlike some fit indices that are normalized and have values between 0 and 1, NNFI does not have this constraint. It provides a measure of fit that doesn’t rely on normal distribution assumptions, making it robust in various modelling situations; (5) Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is one of several fit indices that help researchers evaluate how well their proposed model fits the data; (6) Incremental Fit Index (IFI) is an adjustment of the Normed Fit Index (NFI) which is used to evaluate the extent to which the specified model improves the fit compared to a null model. A higher IFI value, typically above 0.90, indicates a better fit between the model and the data, suggesting that the model explains a significant portion of the variance in the observed variables; (7) Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) quantifies the discrepancy between the model’s predicted covariance matrix and the actual observed covariance matrix. A lower RMSEA value indicates a better fit, with values close to zero indicating an excellent fit; and (8) Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR) is an index of the overall badness-of-fit. It is the square root of the mean of the squared residuals.

Table 2 lists the recommended values of Goodness-of-Fit statistic measures.

Recommended Values of Goodness-of-Fit (GOF) Statistics Induces

| GOF induces | χ2 /df | GFI | NFI | NNFI | CFI | IFI | RMSEA | RMSR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Value | ≦3.0 | ≧0.9 | ≧0.9 | ≧0.9 | ≧0.9 | ≧0.9 | ≦0.05–0.08 | ≦0.05 |

3.2 Selection of Participants

The research population is randomly selected from E-Commerce administrative managers who are responsible for E-Commerce affairs in Taiwan. Paulsen et al. stated that transformational leaders are inclined to recognize the requirement for change and create new ideas. E-Commerce administrative managers are more likely to confront more complicated E-Commerce changes in the working environments, especially of the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic isolation (Paulsen et al., 2013). That is why the E-Commerce administrative managers have been chosen in this research. The samples of 408 participants were randomly selected from the following two resources: the member lists from Taiwan Internet and E-Commerce Association and the Chinese Non-Store Retailer Association because these resources are the main groups of E-Commerce affairs in Taiwan. The questionnaires are randomly sent to E-Commerce administrative managers by online transmission. All of the answers responded by participants are sent back to the database of my3q.com automatically.

3.3 Instrumentation

The questionnaire of this research includes the following four main categories: (1) Big Five Personality Traits, (2) Transformational Leadership, (3) Leadership Self-Efficacy, and (4) Commitment. First, the questionnaire on Big Five personality traits is measured by Goldberg’s NEO-PI-R Personality Inventory which is commonly applied as a measurement of personality traits. Each factor of personality trait is measured by 10 items, including (1) extraversion, (2) agreeableness, (3) conscientiousness, (4) emotional stability, and (5) openness (Goldberg, 1990). Second, the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) full-range model developed by Bass and Avolio et al. is applied to measure the components of transformational leadership (Avolio & Yammarino, 2002). The model of transformational leadership includes four subcomponent leadership styles, including (1) idealized influence, (2) inspirational motivation, (3) intellectual stimulation, and (4) individualized consideration. Third, the questionnaire on leadership self-efficacy is based on the Agentic Leadership Efficacy (ALE) scale, which was designed in accordance with Bandura’s scale development guide (Bandura, 2001). The Agentic Leadership Efficacy (ALE) scale is a construct and model in leadership research. ALE focuses on leader emergence, engagement, and performance. The ALE scale is designed to measure the self-perceived leadership efficacy of individuals. Finally, the questionnaire on commitment is based on the internalization dimension of commitment developed by O’Reilly and Chatman is a concept in organizational psychology. The model of organizational commitment, proposed in 1986, comprises three distinct dimensions that individuals can have towards their organizations: compliance, identification, and internalization. (O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). The five-point Likert scales are employed in each item of personality trait, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.4 Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is applied to examine the construct validity in this study. All factors are extracted by using principal components analysis with Varimax rotation, which is used to measure the following two main variables: personality and transformational leadership.

3.5 Reliability

Internal consistency is applied to examine the reliability of measurement instruments, including Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). According to Fornell and Larcker, adequate internal consistency indicates the fulfillment of the following terms: (1) Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients are greater than 0.7; (2) Composite Reliability coefficients are higher than 0.7; and (3) The AVE of all constructs are greater than 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

4 The Research Analysis

4.1 Measurement Model Evaluation

To ensure the validities of the items selected, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is conducted on the measures of Big Five personality, transformational leadership, and commitment. Six items are selected for each Big Five construct, four items for each transformational leadership construct, and six items for each commitment construct, because of restrictions on the response time set by the participative managers. Two criteria are used to conduct this selection: the highest factor loading in the earlier research and meaningfulness in this study.

The results of all CFAs of measurement models produced suitability Goodness-of-Fit (GOF) indices such as p-value (>0.05); CMIN/DF (<2); RMR (<0.05), RMSEA (<0.08), GFI (>0.9) (Table 3). The CFAs of the big five personality, transformational leadership, and commitment are shown in Table 3. All constructs in this study satisfied the required level.

Goodness of Fit (GOF) analysis-Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

| Constructs | p-Value | CMIN/DF | RMR | RMSEA | GFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | 0.086 | 1.099 | 0.030 | 0.023 | 0.995 |

| Transformational leadership | 0.063 | 1.226 | 0.045 | 0.035 | 0.925 |

| Commitment | 0.073 | 1.185 | 0.036 | 0.032 | 0.917 |

In addition, the factor loading, squared multiple correlation (SMC), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) are examined as evidence of reliability and convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In this study, factor loading for all constructs is all larger than 0.7, squared multiple correlation (SMC) is greater than 0.5, composite reliability (CR) is greater than 0.8, and variance extracted (AVE) is greater than 0.5, which presents a good reliability and convergent validity for constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Table 4).

The results of CFAs

| Construct | Items | Factor loading | Squared multiple correlation | Composite reliability | Variance extracted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big five personality | Extraversion | Ext1 | 0.965 | 0.931 | 0.9757 | 0.8435 |

| Ext2 | 0.898 | 0.806 | ||||

| Ext3 | 0.913 | 0.834 | ||||

| Ext4 | 0.97 | 0.941 | ||||

| Ext5 | 0.887 | 0.787 | ||||

| Ext6 | 0.873 | 0.762 | ||||

| Agreeableness | Agr1 | 0.669 | 0.448 | 0.9668 | 0.8311 | |

| Agr2 | 0.961 | 0.924 | ||||

| Agr3 | 0.974 | 0.949 | ||||

| Agr4 | 0.938 | 0.880 | ||||

| Agr5 | 0.963 | 0.927 | ||||

| Agr6 | 0.927 | 0.859 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | Con1 | 0.862 | 0.743 | 0.9645 | 0.8193 | |

| Con2 | 0.932 | 0.869 | ||||

| Con3 | 0.901 | 0.812 | ||||

| Con4 | 0.876 | 0.767 | ||||

| Con5 | 0.913 | 0.834 | ||||

| Con6 | 0.944 | 0.891 | ||||

| Emotional stability | Emo1 | 0.958 | 0.918 | 0.9772 | 0.8772 | |

| Emo2 | 0.895 | 0.801 | ||||

| Emo3 | 0.908 | 0.824 | ||||

| Emo4 | 0.959 | 0.920 | ||||

| Emo5 | 0.926 | 0.857 | ||||

| Emo6 | 0.971 | 0.943 | ||||

| Openness | Ope1 | 0.798 | 0.637 | 0.9295 | 0.6927 | |

| Ope2 | 0.926 | 0.857 | ||||

| Ope3 | 0.941 | 0.885 | ||||

| Ope4 | 0.755 | 0.570 | ||||

| Ope5 | 0.939 | 0.882 | ||||

| Ope6 | 0.57 | 0.325 | ||||

| Transformational leadership | Idealized influence | II1 | 0.968 | 0.937 | 0.9295 | 0.6927 |

| II2 | 0.87 | 0.757 | ||||

| II3 | 0.939 | 0.882 | ||||

| II4 | 0.956 | 0.914 | ||||

| Inspirational motivation | IM1 | 0.949 | 0.901 | 0.9645 | 0.8716 | |

| IM2 | 0.929 | 0.863 | ||||

| IM3 | 0.939 | 0.882 | ||||

| IM4 | 0.917 | 0.841 | ||||

| Intellectual stimulation | IS1 | 0.951 | 0.904 | 0.9641 | 0.8706 | |

| IS2 | 0.882 | 0.778 | ||||

| IS3 | 0.929 | 0.863 | ||||

| IS4 | 0.968 | 0.937 | ||||

| Individualized consideration | IC1 | 0.907 | 0.823 | 0.9019 | 0.6977 | |

| IC2 | 0.865 | 0.748 | ||||

| IC3 | 0.771 | 0.594 | ||||

| IC4 | 0.791 | 0.626 | ||||

| Commitment | Affective | Aff1 | 0.77 | 0.592 | 0.9123 | 0.635 |

| Aff2 | 0.78 | 0.608 | ||||

| Aff3 | 0.905 | 0.819 | ||||

| Aff4 | 0.767 | 0.588 | ||||

| Aff5 | 0.781 | 0.609 | ||||

| Aff6 | 0.769 | 0.591 | ||||

| Normative | Nor1 | 0.73 | 0.532 | 0.9023 | 0.6071 | |

| Nor2 | 0.754 | 0.568516 | ||||

| Nor3 | 0.787 | 0.619369 | ||||

| Nor4 | 0.821 | 0.674041 | ||||

| Nor5 | 0.72 | 0.5184 | ||||

| Nor6 | 0.854 | 0.729316 | ||||

| Continuation | Con1 | 0.726 | 0.527 | 0.9023 | 0.6071 | |

| Con2 | 0.75 | 0.562 | ||||

| Con3 | 0.852 | 0.725 | ||||

| Con4 | 0.741 | 0.549 | ||||

| Con5 | 0.751 | 0.564 |

Then, Cronbach’s alpha is calculated to analyse the internal consistency of each construct. The Cronbach’s alpha is greater than 0.7, which exceeds the recommended reliability. The components of all constructs are shown in Table 5. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha indicates the results of internal consistency of the construct and its reliability are excellent.

Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient reliability statistics

| Constructs | Component | Cronbach’s alpha | Number of items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | Extraversion | 0.969 | 6 |

| Agreeableness | 0.965 | 6 | |

| Conscientiousness | 0.964 | 6 | |

| Emotional stability | 0.977 | 6 | |

| Openness | 0.927 | 6 | |

| Transformational leadership | Idealized influence | 0.964 | 4 |

| Inspirational motivating | 0.965 | 4 | |

| Intellectual stimulation | 0.963 | 4 | |

| Individualized consideration | 0.901 | 4 | |

| Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy | 0.829 | 10 |

| commitment | Affective | 0.924 | 6 |

| Normative | 0.898 | 6 | |

| Continuation | 0.908 | 6 |

4.2 Structural Model Evaluation

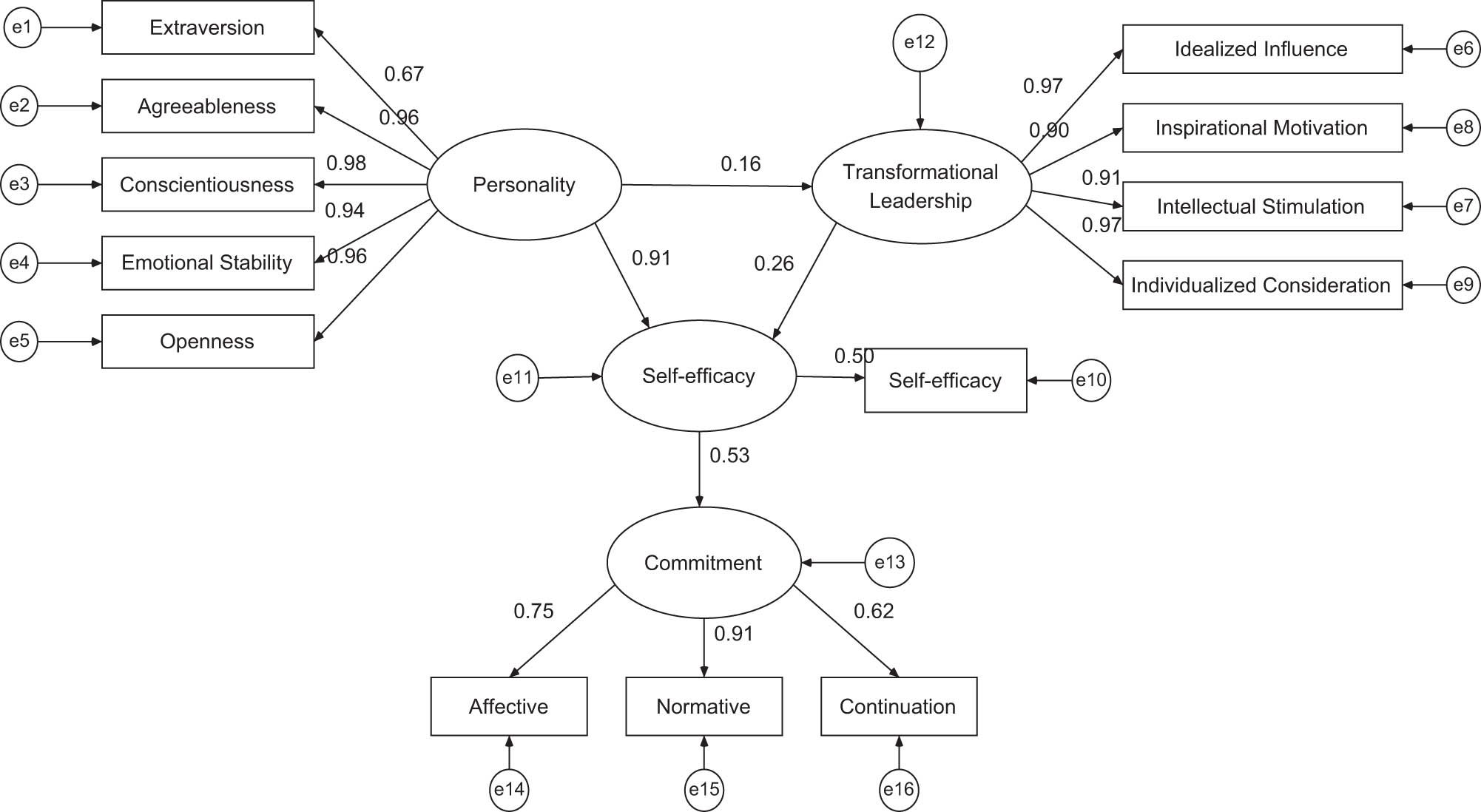

Test hypotheses are proceeded by estimating the conceptual model, with satisfied confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs; Figure 3). The structural model fit is great with χ2/df = 0.962 < 3.0, p-value = 0.561 > 0.05, RMR = 0.029 < 0.05, RMSEA = 0.00 < 0.08, CFI = 0.955 > 0.9, and AGFI = 0.932 > 0.9, indicating a good predictive validity. The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of a leader’s personality traits on transformational leadership (H1), the effects of a leader’s personality traits on leadership self-efficacy (H2), and the effect of transformational leadership on leadership self-efficacy (H3). Then, this study investigates the effect of leadership self-efficacy on commitment (H4). H1, H2, H3, and H4 are supported in this study with significant levels (p < 0.05). The results of the hypotheses are shown in Table 6. The study shows that H1 is significant (p = 0. 028 < 0.05). This means that personality traits significantly have a direct effect on transformational leadership behaviours. This is supported by previous research studies (Avolio et al., 1995; Hogan & Shelton, 1998; Judge & Bono, 2000; Ones et al., 2021). H2 is also significant (p = *** < 0.001). This indicates that personality traits significantly have a direct effect on leadership self-efficiency. This is supported by previous findings (Catino, 1992; Friedman & Rosenman, 1974; Hogan et al., 1994; Larson & LaFasto, 1989; Wellins et al., 1991). Then, H3 is significant (p = 0.008 < 0.05). This indicates that transformational leadership significantly has a direct effect on leadership self-efficacy. This is confirmed by past findings (Bandura, 1997; Kark & Shamir, 2002; Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1996). Therefore, H1, H2, and H3 are supported in this study. In addition, this research examines that personality traits have a direct effect on leadership self-efficacy and an indirect effect on leadership self-efficacy through transformational leadership. Moreover, H4 is significant (p = *** < 0.001). This means that leadership self-efficacy has a direct effect on commitment. This finding is supported by previous findings (Yukl, 1998).

Results of Conceptual Model. Notes: Model fit statistics: χ 2 = 58.67, df = 61, p-value = 0.561, RMR = 0.029, RMSEA = 0, CFI = 0.955, and AGFI = 0.932.

The results of hypotheses: standardized estimates

| Hypothesis | Paths | C.R. | p | Statue | Direct effect | Indirect effect | Total effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Personality traits → Transformational leadership | 2.202 | 0.028 | Sig. | 0.164 | 0 | 0.164 |

| H2 | Personality traits → Leadership self-efficacy | 7.127 | *** | Sig. | 0.909 | 0.043 | 0.951 |

| H3 | Transformational leadership → Leadership self-efficacy | 2.645 | 0.008 | Sig. | 0.260 | 0 | 0.260 |

| H4 | Leadership self-efficacy → Commitment | 5.283 | *** | Sig. | 0.526 | 0 | 0.526 |

Note: Significant at p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

5 Conclusion

This study verifies that personality and transformational leadership play essential roles in enhancing leadership self-efficacy. This study also examines that leadership self-efficacy has a direct effect on organizational commitment. The research provides new evidence on the interrelationships among personality, transformational leadership, leadership self-efficacy, and organizational commitment by applying the notions of Goldberg’ Big Five personality (Goldberg, 1990), Bass’s transformational leadership behaviours (Bass, 1996), Bandura’s self-efficacy (Bandura, 1982), and Meyer and Herscovitch’s commitment (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). Based on those results, this research indicates that a leader with personality traits has a positive influence on transformational leadership; a leader with personality traits has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy; a leader with transformational leadership behaviours has a positive influence on leadership self-efficacy. In addition, a leader with leadership self-efficacy has a positive influence on commitment. Overall, the results of this study are consistent with the previous studies (Abujarad, 2010; Bandura, 1997; Friedman & Rosenman, 1974; Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1996; Ones et al., 2005; Yukl, 1998). Additionally, this research developed an analytical model and tested four hypotheses that involve the interrelationships among personality, transformational leadership, leadership self-efficacy, and commitment (Kaiwen et al., 2022; Najafi et al., 2022). The practical application of this result could provide organizations with a better evaluation model of E-Commerce administrative manager’s leadership by applying their personalities and transformational leadership to enhance leadership self-efficacy and increase the level of organizational commitment (Doulotuzzaman et al., 2022). The academic contribution of this research result provided a better evaluation model of E-Commerce administrative manager’s transformational leadership by applying their personalities and transformational leadership to enhance leadership self-efficacy and increase the level of organizational commitment.

5.1 Research Implication

The implication of those results will be beneficial to leaders by applying their personalities and transformational leadership to enhance leadership self-efficacy and increase the level of organizational commitment (Reza et al., 2022). Organizations could construct the evaluation model of a leaders’ performance and achieve organizational accomplishment by enhancing transformational leadership and leadership self-efficacy (Osintsev & Khalilian, 2023).

5.2 Research Limitations

There are several potential limitations in this study. First, the model of the current study is not devised to include all possible variables. Second, organizational commitment is measured by managers’ perceptions in this study. Organizational commitment can be measured through other different views, for example, subordinates’ perceptions. Moreover, the findings of this study may not be able to be generalized to other countries because of the existence of diverse cultures in different countries. The research population is only randomly selected from E-Commerce administrative managers in Taiwan, which is the applicability of the Eastern model of leadership. If leaders face different environmental challenges in different cultures, they are also likely to need different ways of handling their relations with others. Advanced examination of the applicability of the leadership model is necessary between Eastern and Western cultures. Those limitations could result in constraints of implications.

5.3 Future Researches

The composite models of similar research studies need to be investigated by collecting data from different countries to intensify the width and depth of future research studies. Future scopes of similar models could be investigated from various industries to test the interrelationships among personality, transformational leadership, leadership self-efficacy, and commitment. Future research studies related to the gender of managerial leaders also could be examined to explore the similar composite models of this research between male and female leaders.

-

Funding information: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

-

Data availability statement: The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abdi, Z., Lega, F., Ebeid, N., & Ravaghi, H. (2022). Role of hospital leadership in combating the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Services Management Research, 35(1), 2–6.10.1177/09514848211035620Search in Google Scholar

Abujarad, I. Y. (2010). The impact of personality traits and leadership styles on leadership effectiveness of Malaysian managers. Academic Leadership, 8(2), 1–19.Search in Google Scholar

Agbaria, Q., & Mokh, A. A. (2022). Coping with stress during the coronavirus outbreak: The contribution of big five personality traits and social support. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(3), 1854–1872.10.1007/s11469-021-00486-2Search in Google Scholar

Alderfer, C. P. (1972). Existence, relatedness, and growth: Human needs in organizational settings. New York: Free Press.Search in Google Scholar

Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monograph, 47, 211–216.10.1037/h0093360Search in Google Scholar

Anglim, J., Horwood, S., Smillie, L. D., Marrero, R. J., & Wood, J. K. (2020). Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(4), 279.10.1037/bul0000226Search in Google Scholar

Atwater, L. E., & Yammarino, F. J. (1993). Personal attributes as predictors of superiors’ and subordinates’ perceptions of military academy leadership. Human Relations, 46(5), 645–668.10.1177/001872679304600504Search in Google Scholar

Avolio, B. J., & Yammarino, F. J. (2002). Transformational and charismatic leadership: The road ahead. Amsterdam: JAI.Search in Google Scholar

Avolio, B. J., Bass, B. M., & Jung, D. I. (1995). Multifactor leadership questionnaire technical report. Redwood City, CA: Mind Garden.Search in Google Scholar

Bakker, B. N., Lelkes, Y., & Malka, A. (2021). Reconsidering the link between self-reported personality traits and political preferences. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1482–1498.10.1017/S0003055421000605Search in Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1982).Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147.10.1037//0003-066X.37.2.122Search in Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundation of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.G.Search in Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1990). Some reflections on reflections. Psychological Inquiry, 1, 101–105.10.1207/s15327965pli0101_26Search in Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman.Search in Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (2001). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales (Revised). Frank Pajares, Emory University.Search in Google Scholar

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991).The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26.10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.xSearch in Google Scholar

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1993). Autonomy as a moderator of the relationships between the big five personality dimensions and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 111–118.10.1037//0021-9010.78.1.111Search in Google Scholar

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York, NY: Free Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bass, B. M. (1988). Evolving characteristics on charismatic leadership. In J. Conger & R. N. Kanungo (Eds.), Charismatic leadership: The elusive factor in organizational effectiveness (pp. 40–77). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Bass, B. M. (1996). New paradigm of leadership: An inquiry into transformational leadership (Report No: ADA306579). Alexandria, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences.10.21236/ADA306579Search in Google Scholar

Bass, B. M. (1998). Transformational leadership: Industry, military, and educational impact. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for individual, team, and organizational development. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 4, 231–272.Search in Google Scholar

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Bass, B. M., & Jung, D. (2003). Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 207–218.10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.207Search in Google Scholar

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. (2006). Transformational leadership. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.10.4324/9781410617095Search in Google Scholar

Bellibaş, M. Ş., Kılınç, A. Ç., & Polatcan, M. (2021). The moderation role of transformational leadership in the effect of instructional leadership on teacher professional learning and instructional practice: An integrated leadership perspective. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(5), 776–814.10.1177/0013161X211035079Search in Google Scholar

Bennis, W. (1989). Why leaders can’t lead. Training and Development Journal, 43(4), 35–40.Search in Google Scholar

Bennis, W., & Nanus, B. (1985). Leaders: The strategies of taking charge. New York: Harper and Row.Search in Google Scholar

Black, J. S. (1990). The relationship of personnel characteristics with the adjustment of Japanese expatriate managers. Management International Review, 30, 119–134.Search in Google Scholar