Abstract

Herein protective coatings against corrosion are compared with regard to their protective efficiency. The coatings had been prepared over the course of time from differently trialkoxysilyl-functionalized commercial or synthesized precursors but were tested using the same techniques and in similar conditions. The coatings are compared according to the existing data on contact angles for water, free surface energy, thickness and protective efficiency, expressed in term of corrosion current density. Moreover, the influence of differently functionalized trialkoxysilyl precursors on the crosslinking of coatings is regarded. It was also noted that too hydrophobic additives can introduce certain defects which can detrimentally influence the protective efficiency. Spectroelectrochemical approach can give important insights into the degradation of protective coatings under electrochemically induced loads. Ex situ infrared reflection-absorption (IR RA) spectroelectrochemical approach can identify hydration, breakage of some siloxane bands or changes in the C–H spectral region. Careful examination can confirm the interruption of some bands between alloy and coating that are responsible for its adhesion. Raman imaging is appropriate to follow the formation and growth of pits that form in the coatings.

1 Introduction

Literature offers numerous investigations of protective coatings for metals/alloys (Bouali et al. 2020; Eduok et al. 2017; Figueira et al. 2016; Wang and Bierwagen 2009) but rarely any straightforward comparison of their protective efficiency. The reason may lie in their different composition and thickness but also in various characterization techniques and conditions used for the evaluation of their longevity. However, the comparison of the coatings can be made by taking a group of materials (i.e., precursors) that were investigated in the similar conditions and on the same type of alloy. Such comparison may offer important clues on relations between structure of the precursors and the characteristic properties of the protective coatings.

An example could be sol-gel protective coatings produced from various trialkoxysilyl-based precursors (Figueira et al. 2016; Wang and Bierwagen 2009; Zadeh et al. 2016). Sol–gel coatings have often been used as primers, i.e., in a very thin layer form to improve the adhesion of the overlaying polymeric layers to metals/alloys. On the other side, sol–gel layers were also studied in a form of compact protective coatings (Figueira et al. 2016; Fir et al. 2007; Jerman et al. 2011; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Surca et al. 2017; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008; Wang and Bierwagen 2009). An important issue of the latter is how to ensure high rate of crosslinking to produce high-density coatings.

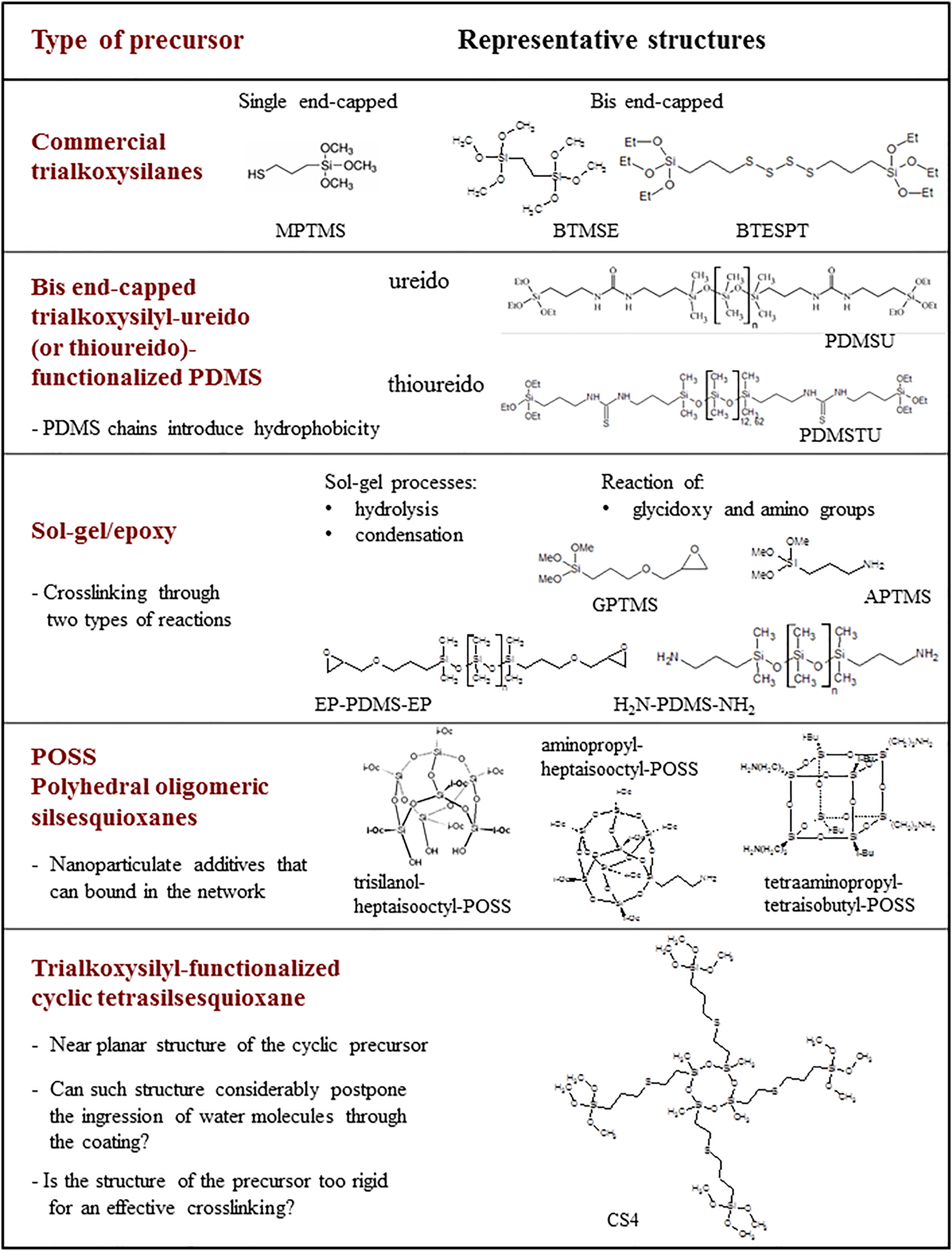

A large variability of trialkoxysilyl-functionalized precursors that are accessible commercially or synthesized in the laboratories led to coatings with a considerably wide range of efficiency. The examples of the relevant structures are shown in Figure 1. Since the protective efficiency and other properties arise from the structural characteristics of the coatings the questions – as described below – can be set.

The most obvious factor that influences the crosslinking in the coatings is the single or bis end-capped character of the trialkoxysilyl-based precursor molecule. The former precursors have a trialkoxysilyl group only on one side of the molecule while the bis end-capped precursors terminate on both sides with the reactive trialkoxysilyl groups.

The hydrophobic groups can be introduced into the trialkoxysilyl precursor structure with the aim to improve the impermeability of the coatings. An example is the polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chain that upon addition to various materials tends to increase the contact angles for water and lower their surface energy (Eduok et al. 2017). Hydrophobicity is an important factor of protective coatings since this property controls the access of water molecules to the alloy|coating interface.

The precursor can also combine two different reactive groups, for instance, trialkoxysilyl and epoxy groups. Such example is 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GPTMS), which has been very frequently studied in protective coatings against corrosion (Jerman et al. 2011; Rauter et al. 2013). In addition to sol-gel processes of trimethoxysilyl groups, epoxy groups contribute to crosslinking through reaction with amino groups of another precursor.

Protective efficiency has been in many examples improved by the addition of nanoparticles, for instance CeO2 (Cambon et al. 2012; Selegård et al. 2021). Question arises whether such nanoparticles have been leached out during the exposure of coatings to atmospheric conditions. The use of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) nanoparticles offers their bonding into the sol-gel network through their organic R groups in the so-called organic shell. Specifically, POSS could be described using a formulae (R–SiO3/2)n (n = 6, 8, 10 …; R – organic group), representing silica based core and organic shell. Such covalent bonding prevents leaching of POSS nanoparticles from the protective coatings.

The silsesquioxanes can also be prepared in a cyclic form. Their functionalization with the trialkoxysilyl groups enables the crosslinking sol-gel reactions to occur. The premise was that the planar structure of the cyclic silsesquioxane may considerably slow down the water ingression and its propagation towards the alloy|coating interface.

Schematic presentation of the trialkoxysilyl-functionalized precursors used for the preparation of sol–gel protective coatings on AA 2024. All abbreviations are described in Section 2.1.

The comparison of sol-gel coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilyl-based precursors (Fir et al. 2007; Jerman et al. 2011; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008) was made for coatings deposited on aluminum alloy AA 2024 substrate. This material is light, non-toxic, has high strength-to-weight ratio and is important in aircraft, automotive and other industries. Alkoxysilyl groups from the sol–gel coating can form firm Al-O-Si bonds (Fir et al. 2007; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008) with this alloy which improves the longevity of sol–gel protection.

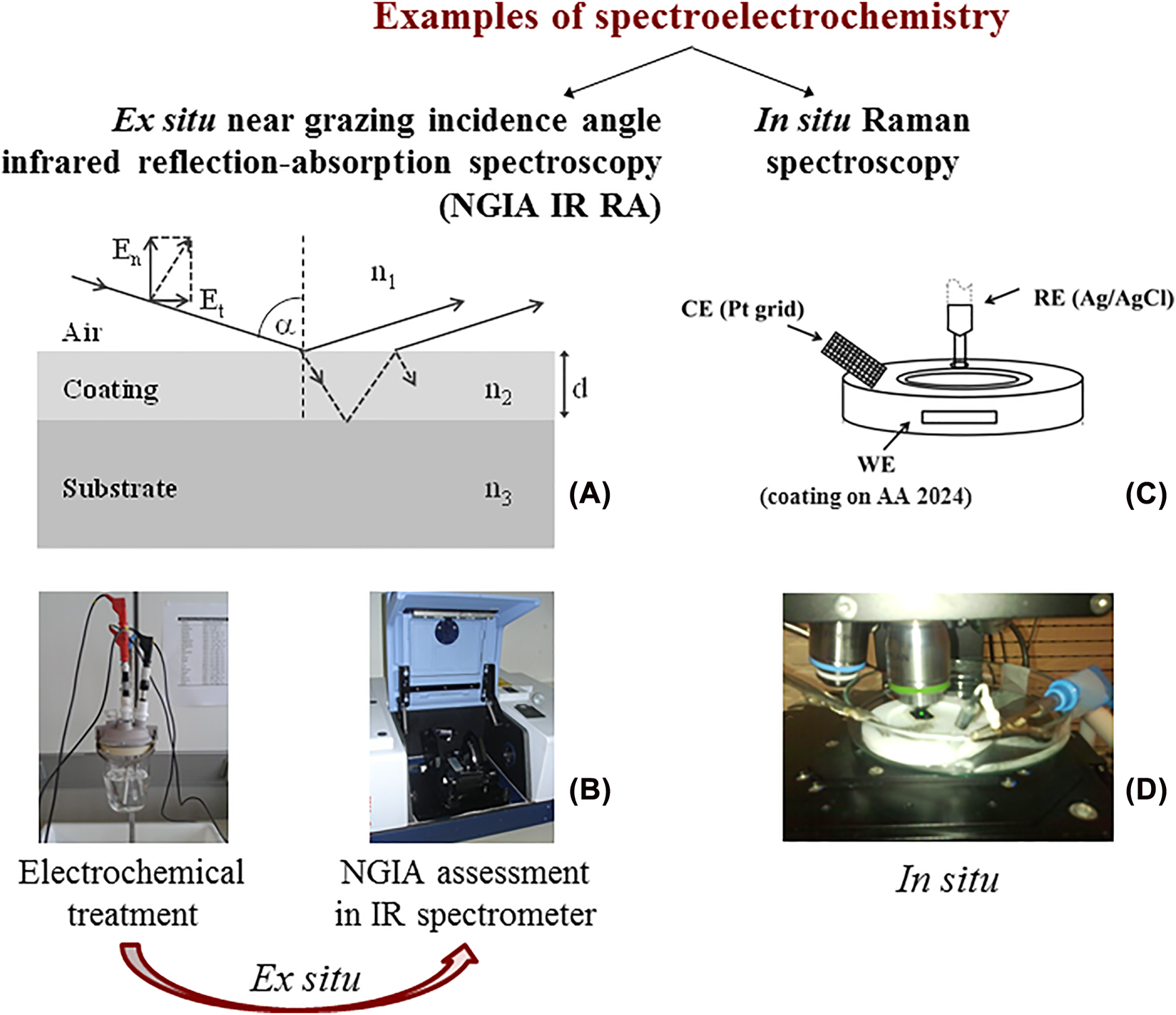

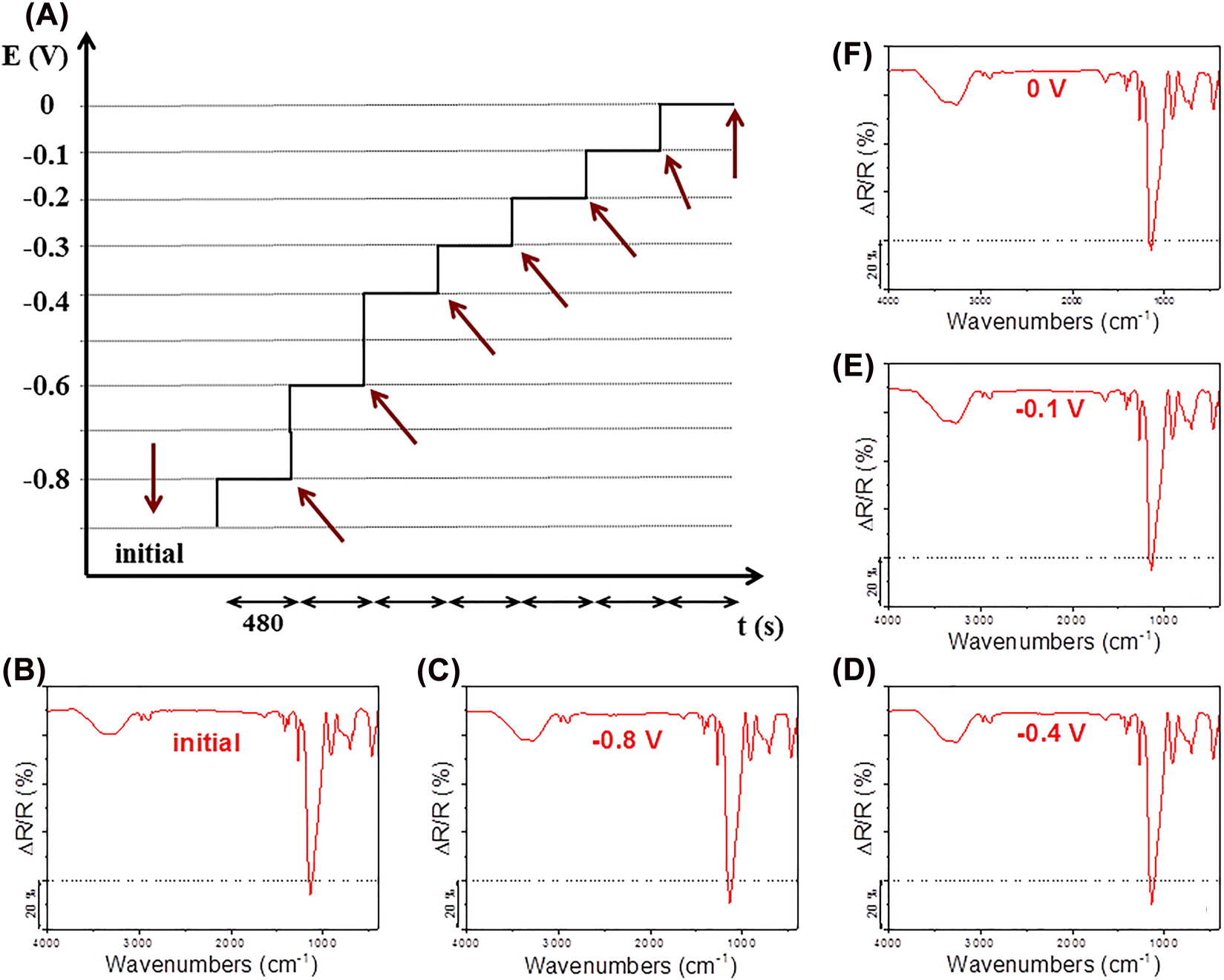

Another aspect that needs discussion is the spectroelectrochemical approach in investigation of protective coatings. Although many researchers do not know or use it, it can give important results. The spectroelectrochemical approach combines a spectroscopic technique with an electrochemical treatment (Figure 2). The measurement can occur simultaneously (in situ) or immediately after (ex situ) (Greef et al. 1990; Surca et al. 2018). Different spectroscopies can be combined, among them also infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy (Greef et al. 1990; Holze 2004; Iwasita and Nart 1997; Surca et al. 2018). While sole electrochemical experiment gives the sum of all the processes in the cell, the spectroelectrochemical approach can offer information on the surface properties of the electrodes (adsorption and orientation) or changes in vibrations of the functional groups.

Two examples of spectroelectrochemical measurement: ex situ NGIA IR RA, (A) principle of NGIA IR RA measurement, (B) ex situ experiment and in situ Raman, (C) scheme of in situ cell, (D) experiment.

In the studies of protective coatings, the spectroelectrochemical technique can be employed to detect the changes that occur in coatings during the electrochemically forced degradation through the gradual increase in anodic polarization (Fir et al. 2007; Jerman et al. 2011; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Surca et al. 2018; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008). Since protective coatings are usually thick (also up to some μm range) and effective it is not an easy task to achieve their degradation.

Ex situ near grazing incidence angle (NGIA) infrared reflection–absorption (IR RA) spectroscopy is an appropriate IR technique for detection of eventual degradation changes. However, it demands the preparation of somewhat thinner coatings, not above some hundreds of nm. The incidence beam is P-polarized and falls on alloy/coating tandem under the near grazing condition (Figure 2A). Consequently, the longitudinal optical (LO) modes appear in the IR RA spectra which are for inorganic materials usually shifted towards higher frequencies (i.e., wavenumbers) (Grosse 1990). For ex situ IR RA measurement, the coating is first charged for a certain time in the electrochemical cell with its potential gradually increasing (Figure 2B). After each charging the sample is transferred to the sample compartment of the IR spectrometer and the IR RA spectrum recorded. Comparison of the initial and the most polarized spectrum often gives information on hydration of the coating, breakage of some siloxane bonds or -Si-O-Al- bonds responsible for bonding of the sol–gel coating to the surface of the alloy (Fir et al. 2007; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008).

In situ Raman spectroelectrochemistry is also an important key to detection of changes in the protective coatings with the anodic polarization (Figure 2C, D). When Raman imaging is used it can give evidence on the formation of pits. While the main concerns of the ex situ measurements remain the eventual changes that can occur to the sample during its manipulation outside of the electrochemical cell, the construction of in situ cells can be demanding and intensity of the resulting signals low. Specifically, in situ cells should be adapted to the requirements of the spectroscopic technique, approach to the proper electrochemical geometry, concern the size of the sample and, if necessary, sealing (Greef et al. 1990; Holze 2004; Iwasita and Nart 1997; Surca et al. 2018).

Consequently, herein the protective coatings prepared from different trialkoxysilyl-functionalized precursors are compared. All concerned coatings were deposited on aluminum alloy AA 2024 substrate and investigated using equal techniques in similar measurement conditions. The coatings from nine works (Fir et al. 2007; Jerman et al. 2011; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Surca et al. 2017; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008) are compared according to their protective efficiency and hydrophobic properties with the aim to find eventual correlations with the structure of the trialkoxysilyl-precursor and coating. In addition, the possibilities of the ex situ IR RA and in situ Raman spectroelectrochemical measurements in the study of protective coatings are shown. By using them, the degradation processes that eventually can occur in the protective coatings with prolonged time of exposure can be mimicked.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of protective coatings

The preparation procedures were given in details in references (Fir et al. 2007; Jerman et al. 2011; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Surca et al. 2017; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008) describing the characteristics of these coatings. Herein, the precursors are described shortly with the aim to enable the comparison of these coatings. Specifically, sol–gel protective coatings (Figure 1, Supplementary Tables S1–S3) were prepared from trialkoxysilyl-based organic–inorganic hybrids that were either commercial or synthesized. Among commercial precursors were (3-mercaptopropyl)trimethoxylsilane (MPTMS), 1,2-bis(trimethoxysilyl)ethane (BTMSE), bis-([3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl]tetrasulphide) (BTESPT), 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GPTMS), (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APTMS) and aminopropyl terminated poly(dimethylsiloxane) (H2N-PDMS-NH2).

Other precursors were synthesized in the laboratory. The bis end-capped triylkoxysilyl-based PDMSU and PDMSTU (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1) were prepared by reacting aminopropyl-terminated poly(dimethylsiloxane) with either (3-isocyanatopropyl)triethoxysilane (Fir et al. 2007; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008) or (3-isothiocyanatopropyl)triethoxysilane (Surca et al. 2017). The details can be found in concerned publications.

The crosslinking in the epoxy-based coatings (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S2) occurred via two different types of reactions, i.e., the sol–gel processes and the reaction of epoxy and amino groups (Jerman et al. 2011; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014). Nanoparticulate structures of various POSS molecules were also introduced in these coatings. The trisilanol-heptaisooctyl-POSS and aminopropyl-heptaisooctyl-POSS were purchased from Hybrid plastics while tetraaminopropyl-tetraisobutyl-POSS was synthesized in an autoclave at 150 °C from isobutyltrimethoxysilane and APTMS in tetrahydrofuron (Jerman et al. 2011). A commercial 3-glycidoxypropyl terminated poly(dimethylsiloxane) (EP-PDMS-EP) precursor (Rodošek et al. 2014) was used to enable comparison with PDMS chains introduced in coatings via the terminal amino groups.

Protective coatings on the basis of trialkoxysilyl-functionalized cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane CS4 precursor (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S3) were deposited from three types of sols (Rodošek et al. 2017). The first sol was produced from only CS4 precursor (i), into the second sol a simple trialkoxysilane BTMSE was added (ii) while the other sols were composed of CS4, BTMSE and one of the five additives with a hydrophobic character. The additives were dimethyldiethoxysilane (DMDES), phenyltrimethoxysilane (PhTMS), isooctyl trimethoxysilane (IOTMS), hexadecyltrimethoxysilane (HDTMS) and 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyltriethoxysilane (PFOTES).

Coupons of aluminum alloy AA 2024 were before deposition of coatings polished using a 3M Perfect-IT III polish paste. Then, the coupons were subsequently sonificated in hexane, acetone, methanol and distilled water for 15 min.

2.2 Instrumental techniques

Potentiodynamic polarization technique is appropriate for quick determination of efficiency of protective coatings against corrosion. The technique is relative and should be performed in the same conditions if comparison of the examined coatings is intended. A reference electrode was Ag/AgCl/KClsat and a counter electrode Pt grid. The coating on AA 2024 aluminum alloy was mounted as a working electrode in a standard K0235 flat cell filled with 0.5 M NaClaq electrolyte. Prior the measurement the coatings were left 30 min at an open circuit potential. Then, polarization was performed using either a potentiostat-galvanostat Autolab PGSTAT 30 or PGSTST 302N (Fir et al. 2007; Jerman et al. 2011; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Surca et al. 2017; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008).

The thickness of the coatings was determined on a profilometer Taylor Hobson, Series II. Contact angles were measured using 20 µm drops on a manual goniometer (Krüss) (Fir et al. 2007; Jerman et al. 2011; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Surca et al. 2017; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008). Three liquids (water, diiodomethane and formamide) were applied with the aim to calculate surface free energy values of coatings according to Van Oss et al. (1998).

The near grazing incidence angle (NGIA) infrared reflection-absorption (IR RA) spectroelectrochemistry is a technique that is suitable for thin coatings with thickness of up to some hundreds of nm. In addition, coatings have to be deposited on the reflective substrates. The measurements need to be performed in a special commercial assessment for NGIA specular reflectance. During measurement the P-polarized beam falls to the coating under the near grazing incidence angle condition (we use 80°). Consequently, the bands that appear in the IR RA spectra correspond to the longitudinal optical (LO) modes. Such LO modes are usually shifted towards higher wavenumbers but may also have different shapes than the bands in the absorbance spectra of coatings. The principles of IR RA spectroscopy are more in detail described in Grosse (1990). For ex situ IR RA measurements (Fir et al. 2007; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Surca et al. 2017), the protective coating was first chronocoulometrically charged in a usual electrochemical cell at a chosen potential using potentiostat-galvanostat Autolab PGSTAT 30 or PGSTAT 302N. The electrolyte was 0.5 M NaClaq. After charging, the sample was rinsed with miliQ water, dried in a flux of nitrogen and transferred to the NGIA attachment in the Bruker IFS66/S IR spectrometer. Since the coating was on one side of the AA 2024 substrate only, its back side and edges were protected with paraffin. The procedure of electrochemical treatment and spectral measurement was then repeated at more and more positive potential.

In situ Raman spectroelectrochemical measurements of protective coatings were performed on the WITec alpha 300 confocal Raman spectrometer (Rodošek et al. 2014, 2017; Surca et al. 2017). A custom-made teflon cell was constructed and the coating on AA 2024 alloy mounted as a working electrode (WE). The edges and the rear side of the alloy were protected by paraffin. Pt grid was used as a counter electrode (CE) and Ag/AgCl/KClsat as a reference electrode (RE). Electrolyte was 0.5 M NaClaq. The single spectra were measured at the same site during chronocoulometric polarization towards higher positive potentials. Raman image of 3 × 5 μm2 was recorded with 90 points per line and 150 lines per image.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Comparison of sol-gel protective coatings

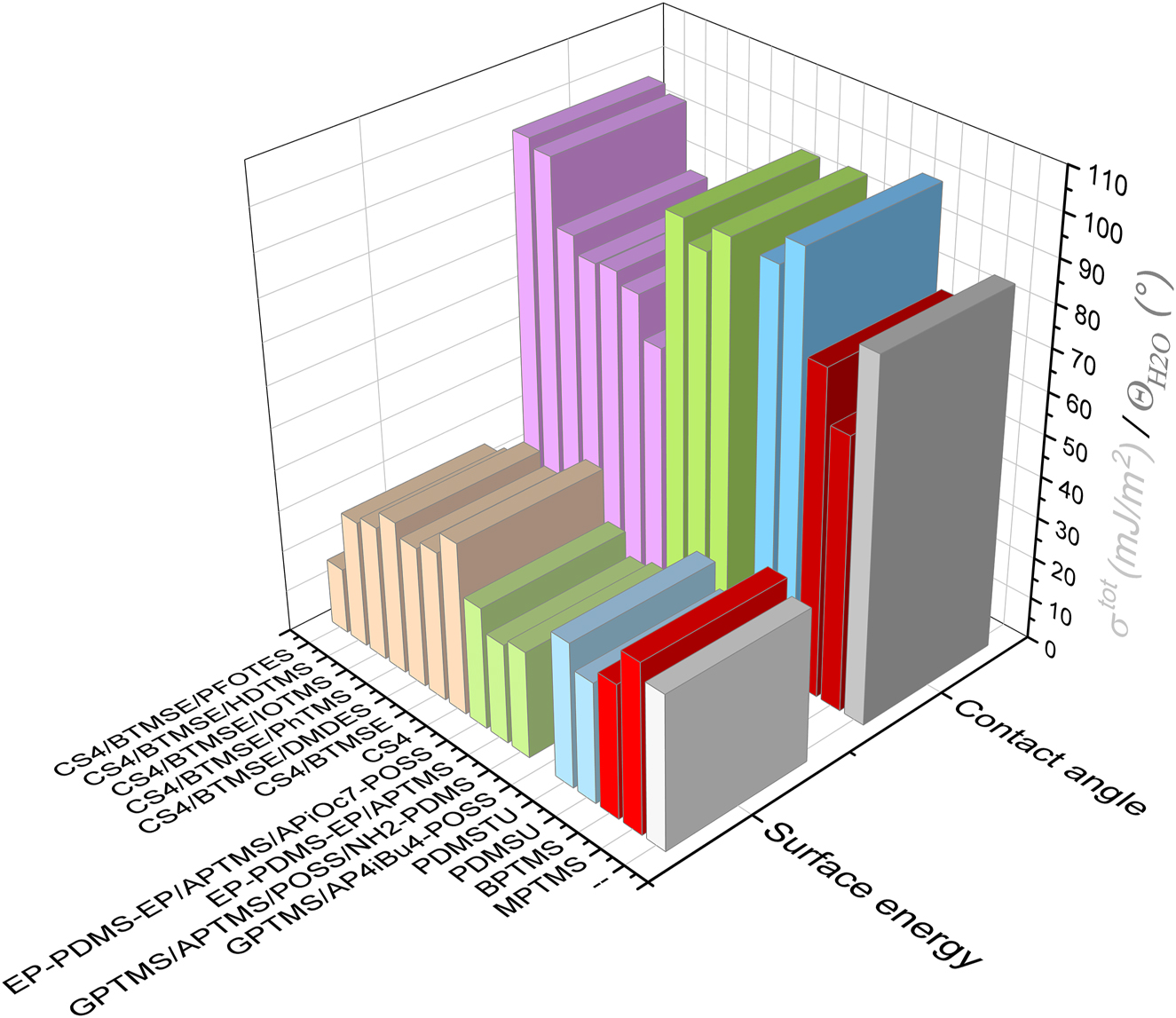

The comparison of contact angles for water and free surface energy values of concerned coatings (Figure 1, Supplementary Tables S1–S3) is shown in Figure 3. It shows that the highest contact angle of 101° is observed for the coating prepared from bis-trialkoxysilyl-ureido-functionalized-PDMS (PDMSU coating (Fir et al. 2007; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008). The counterpart coating PDMSTU with addition of bis end-capped BTESPT and trisilanol-heptaisooctyl-POSS (Surca et al. 2017) achieved contact angle of 94.7°. Moreover, contact angels above 90° were obtained for sol-gel/epoxy coatings that also contained PDMS chains (Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014). Among coatings that did not include PDMS chains, such high values were only obtained for cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane/BTMSE containing coatings with either hexadecyltrimethoxysilane (HDTMS; 94.7°) or 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyltriethoxysilane (PFOTES; 96.7°) additive (Rodošek et al. 2017). All other coatings were characterized by contact angles from 63 to 79° (Figure 3). The contact angle values above 90° are in line with the presence of precursor molecules with characteristic functional groups that decrease wettability. The examples are the well-known fluorine containing PFOTES, dimethylpolysiloxane backbone of PDMS chains and, long alkane chains in HDTMS or isooctyl groups in the organic shell of the POSS nanoparticles.

Contact angles for water and free surface energy values of various sol-gel films. Different shades represent materials’ groups.

Free surface energy values τtot show somewhat complementary response compared to the contact angle values. However, τtot does not reflect only the surface response to water molecules but also to organic liquids (diiodomethane, formamide) (Van Oss et al. 1998). For application as the protective coating against corrosion, lower values of τtot are desired. The incorporation of PFOTES into the cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane/BTMSE-based coating lead to the lowest free surface energy value τtot of 15.9 mJ/m2 (Rodošek et al. 2017). However, τtot of the other hydrophobic coatings (contact angle > 90°) was considerably higher. For example, already the counterpart coating based on cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane/BTMSE and HDTMS additive reached τtot of 30.7 mJ/m2, i.e., almost a double value compared to the above-mentioned coating with the PFOTES additive (Rodošek et al. 2017). The other hydrophobic coatings obtained τtot values of 29.0 mJ/m2 (PDMSU (Fir et al. 2007; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008)), 34.8 mJ/m2 (PDMSTU (Surca et al. 2017)) and, 22.6–30.4 mJ/m2 (sol-gel/epoxy (Jerman et al. 2011; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014)). The highest free surface energy value (40.8 mJ/m2) was measured for the coating prepared form the commercial trialkoxysilane MPTMS.

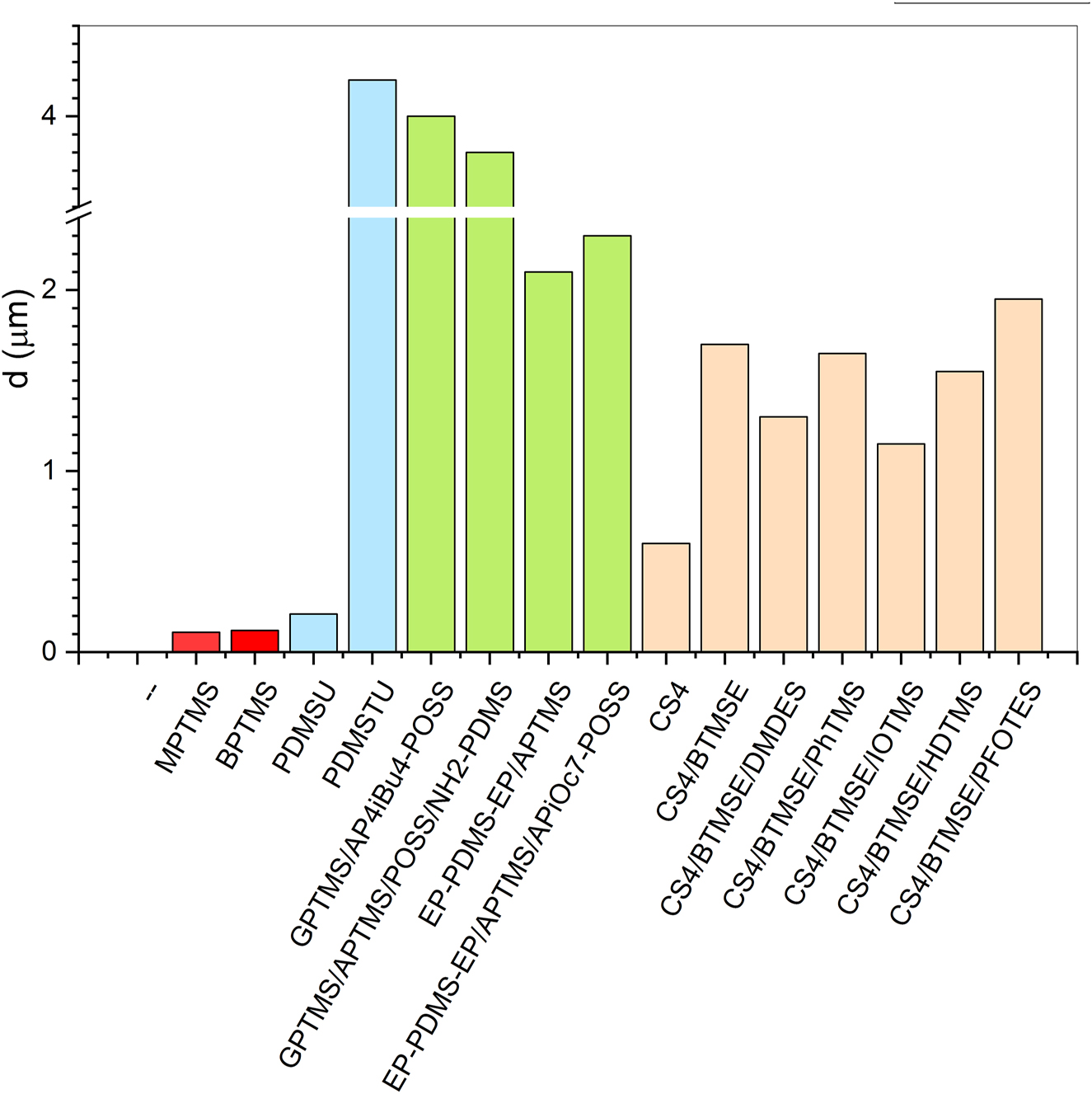

Low wettability and low free surface energy (Figure 3) contribute considerably to the performance of the protective coatings against corrosion. As these two parameters are more dependent on the close-to-surface distribution of molecules, structure and thickness of coatings are other relevant factors that influence the protective efficiency. The presentation of thickness in Figure 4 reveals that the lowest thickness was noted for the coatings prepared from simple commercial trialkoxysilanes (MPTMS, BPTMS), PDMS and cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane CS4. The counterpart of the PDMS coating, i.e., PDMSTU is the thickest (4.2 μm) but comprises also two other precursors (additional trialkoxysilyl-functionalized BTESPT and trisilanol-heptaisooctyl-POSS) (Supplementary Table S1). Somewhat less thick are coatings on the basis of GPTMS (3.8–4 μm). Coatings prepared from epoxy-terminated PDMS chains reach of about 2 μm while tetrasilsesquioxane/BTMSE-based coatings are 1–2 μm thick. It is obvious that the thinner coatings were made when only one trialkoxysilyl-based precursor molecule was applied. In case of multiple precursors (trialkoxysilyl-based, various POSS or hydrophobic additives) thicker protective coatings resulted (Supplementary Tables S1–S3). The single precursor-based coatings presumably ended in the more aligned structures while multiple precursors suggested an infiltration of a certain degree of disorder. Anyhow, when the interbonded precursor molecules form dense and compact coatings such structures can considerably influence the penetration of water and other species from the electrolyte towards the interface coating|alloy. The measure of the performance can be expressed as a protective efficiency.

Thickness of various sol–gel coatings.

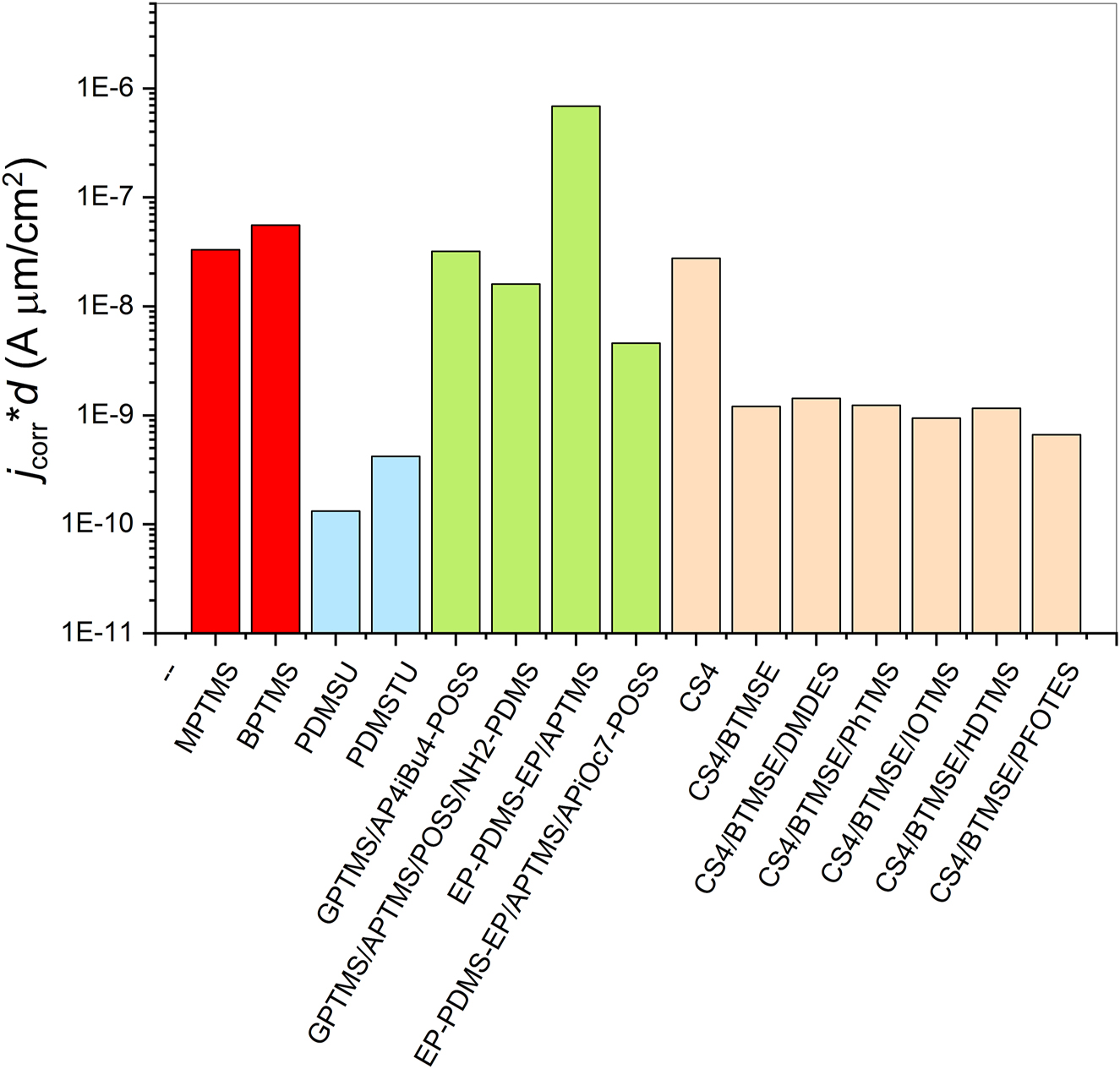

The values of protective efficiency of regarded sol-gel coatings are compared in Figure 5. As a measure of protective efficiency are taken the reported corrosion current densities jcorr obtained from potentiodynamic polarization curves in 0.5 M NaClaq electrolyte (Fir et al. 2007; Jerman et al. 2011; Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2016, 2017; Surca et al. 2017; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008). The thickness of the coatings is taken into account (Figure 4). It could be observed that the lowest jcorr values were achieved using PDMS-based precursors. Performance of PDMSU coatings (Fir et al. 2007; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008) exceeded that of PDMSTU coatings (Surca et al. 2017). The reason can lie in the tendency of the urethane –NH–CO– groups to hydrogen bonding which has been thoroughly investigated for various di-ureasil ormolytes (Nunes et al. 2004). The hydrogen bonding in the PDMSU coatings (Fir et al. 2007; Šurca Vuk et al. 2008) and the consequent alignment of the precursor molecules expressed also in much thinner coatings needed for a similar protective efficiency (Figure 5) compared to the PDMSTU coating (with thiourethane –NH–CS– bonding) (Surca et al. 2017). In the PDMSTU coatings the effect of the presence of sulphur was studied primarily. When an electron pair is available on sulphur atom it can coordinatively bound to copper, which is the main alloying element in AA 2024 alloy. At the same time, copper-containing sites are the most prone to corrosion and their protection can contribute to the overall protective efficiency of the coatings. Sulphur-containing compounds have therefore been tested in quite some protective coatings (Cabral et al. 2005; Zhu and van Ooij 2004). The thioether bonding, on the other hand, cannot lead to bonding to the alloy surface, but eventually only inhibit with regard to the Pearson’s theory of soft and hard acids.

Protective efficiency of various sol–gel coatings considering their thickness.

Very good protective efficiency (Figure 5) was noted also for coatings prepared on the basis of cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane and BTMSE (without or with trialkoxysilane additives). Their jcorr values are around 10−9 A/cm2. The coating prepared from only cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane is less protective, probably due to the steric hindrances for bonding among the alkoxy groups arising from its planar structure (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, when the trialkoxysilyl-ending chains of such large molecules bond, the coating is not dense but allows the propagation of water and other species from electrolyte. The addition of BTMSE immediately improves the coating’s flexibility and protective ability (Figure 5). Interestingly, addition of 2.5 wt% of five trialkoxysilanes with various functional groups did not significantly influence corrosion current density. However, these additives considerably influenced the pitting potential of the coatings (Rodošek et al. 2017). Specifically, the most hydrophobic additives of PFOTES and HDTMS postponed it to 0.66 and 1.03 V, respectively, while for other coatings it ranged from −0.53 to 0.32 V (Rodošek et al. 2017). Tetrasilsesquioxane-based coatings were also exposed to salt spray tests in which the coatings were in salty environment for days. Surprisingly, this kind of testing revealed that longevity of the coating with PFOTES does not reach that of the coating with HDTMS. AFM image (Rodošek et al. 2017) revealed small holes in the structure of the coating with PFOTES, which are responsible for lowering of the efficiency in the salt-spray chamber. This finding revealed that the addition of highly hydrophobic molecules could have an opposite effect. For example, although the presence of such molecules postpones the ingression of water considerably, it can – when water molecules reach the interface – withhold them below the coating. Especially the industrial partners warn us of introducing too hydrophobic molecules in the protective coatings since they are not so effective on the long run on terrain. Additionally, as mentioned above, the highly hydrophobic coatings can impose various defects (like small holes) in the structure of the coatings. If such irregularity can be avoided by careful preparation on the laboratory scale it can impose tremendous problems on the industrial scale.

Coatings prepared from trialkoxysilanes (MPTMS, BPTMS) (Mihelčič et al. 2017; Rodošek et al. 2016) and sol-gel/epoxy coatings (Jerman et al. 2011; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014) were mostly characterized by corrosion current density jcorr in the range of 10−8–10−7 A/cm2. The hydrophobic character of sol-gel/epoxy coatings was introduced either through PDMS chains or POSS precursors. The former were introduced either as aminopropyl- (Rauter et al. 2013) or 3-glycidoxypropyl- (Rodošek et al. 2014) terminated PDMS chains and the latter as tetraaminopropyl-tetraisobutyl-POSS (AP4iBu4-POSS) (Jerman et al. 2011) or aminopropyl-heptaisooctyl-POSS (APiOc7-POSS) (Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014). The jcorr showed similar values for sol-gel/epoxy coatings that contained POSS, but was higher (6.9 × 10−7 A/cm2 – meaning lower protection efficiency) for EP-PDMS-EP/APTMS coating (Rodošek et al. 2014). This was surprising since this coating also contained PDMS chains but obviously, with the addition of POSS, the protective efficiency increased significantly (jcorr decreased even to 8.7 × 10−10 A/cm2) (Rodošek et al. 2014). It should be stressed, however, that POSS molecules can bound via the amino groups into the structure of the coatings (to the terminal glycidoxy groups). It is interesting that despite the glycidoxy-based coatings were quite thick; this did not contribute significantly to their protective efficiency. This hints at the conclusion that crosslinking of coatings has larger influence on the protective efficiency with regard to its thickness.

3.2 Vibrational spectroelectrochemistry of protective coatings

Longevity of protective coatings is usually estimated through electrochemical techniques or exposure to salt spray. These methods are based on increased load, to which the coating is exposed and, estimation of the extent of its degradation. In salt spray test percentage of the corroded surface can be used for such estimation, while for potentiodynamic polarization technique the corrosion current density and break down potential can be applied. A more deep insight into corrosion processes can certainly be achieved using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), but the detailed mechanistic interpretation is often demanding.

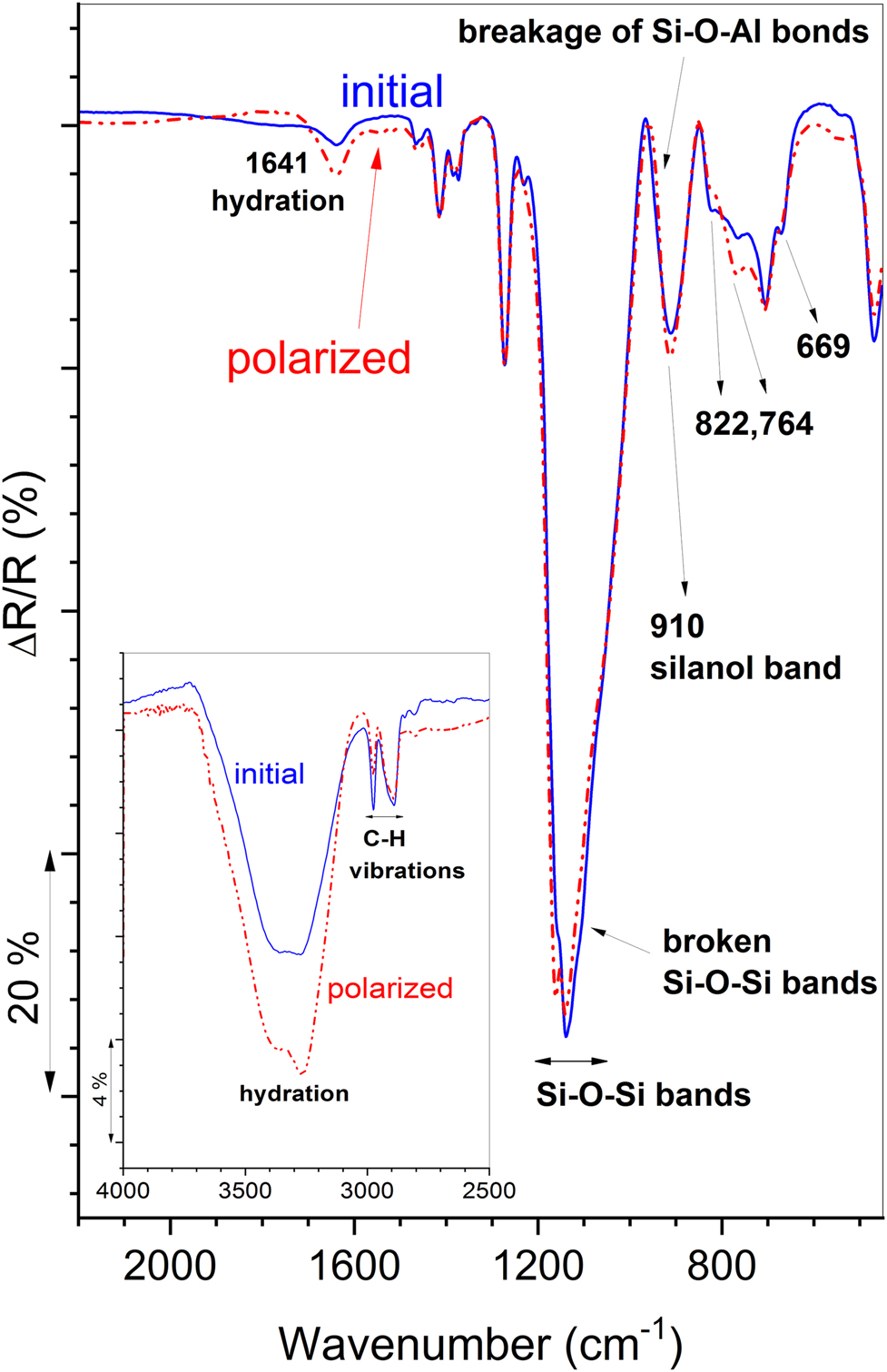

Another available technique, ex situ infrared reflection–absorption (IR RA) spectroelectrochemistry relies on the detection of degradation that is achieved through the electrochemically accelerated corrosion processes. Accordingly, the protective coating is exposed to chronocoulometric charging at certain potentials, expanding towards more and more positive values (Figure 6A). IR RA technique is adapted to thin coatings, consequently, for such measurements thinner protective coatings need to be prepared. Despite this fact, the protective coatings are so good that often only small changes in the ex situ IR RA spectra are detected. Specifically, at the first glance only the slow decrease in intensity of the bands is noted (Figure 6B–F). The reason for small changes is – in addition to good protective ability of coatings – the sampling region. Namely, corrosion processes are often localized, starting from pits, while IR radiation in IR RA experiment grazes the coating in a direction of line and consequently reflects the average situation. Since the coatings are stable and not prone to degradation the eventually formed pits not necessarily lay on the sampling line. Despite that interesting features can be recognized if the initial ex situ IR RA spectrum is compared with the most polarized one (Figure 7). An example is depicted for BTMSE coating (similar as in Rodošek et al. 2016) and the spectra were up-scaled regarding the 1273 cm−1 band. Assignment of the bands is shown in Table 1 and was made according to references (Durig et al. 2003; Li et al. 2006, 2009; Snyder and Strauss 1982).

Gradual overall intensity decrease. Ex situ IR RA spectra obtained at certain potentials reveal slow decrease in the band intensity. This occurred during the exposure of the coating to the gradual increase in the potential and to the manipulation with the sample outside of the electrochemical cell (Figure 6B–F). At a first glance, the pitting corrosion that occurred at −0.3 V has not influenced any band considerably.

Hydration. The set of ex situ IR RA spectra also revealed hydration of the coating with increase in the potential. Hydration becomes much more obvious when the initial and the most polarized spectra are scaled up with respect to the 1273 cm−1 band and compared (Figure 7). The intensity of the broad band around 3260 cm−1 and the bending mode at 1641 cm−1 increased during polarization. Similarly, an increase in intensity can be noted in the region of water rocking at 686 cm−1.

Si–O–Si breakage. In addition, the ex situ IR RA spectra often show the depletion from the low frequency side of the Si–O–Si band. In the case of BTMSE coating, the 1139 cm−1 band shifted to a higher frequency of 1142 cm−1, in this way forming such depletion due to the broken Si–O–Si bands.

Silanol band. Simultaneously, recognizable, but small increase in the intensity of the silanol (ν(Si–OH)) band at 910 cm−1 can be noted.

Spectral region 850–650 cm−1. The γ(CH2) bands of BTMSE coating at 822 and 764 cm−1 exchanged their intensities. Moreover, the intensity of the ν(SiO3) shoulder band diminished and the shoulder became less distinct. This also arises from the breakage of some Si–O–Si bonds.

Coating-alloy bonding. Breakage of some Si–O–Al bonds between coating and alloy substrate can be recognized through changes in the spectral region 1050–850 cm−1 (Beccaria and Chiaruttini 1999; Li et al. 2009; Zandi-Zand et al. 2005). In case of the BTMSE coating, this effect can be seen as a narrowing of the silanol 910 cm−1 band from the high-frequency side.

C–H vibrations. Changes can be noted in the stretching and bending C–H regions. For coatings that comprise alkane chains, additional stretching methylene modes appeared (Rodošek et al. 2014; Snyder and Strauss 1982). This effect can reflect the formation of conformationally more disordered methylene chains, but the changes in the chemical environment also contribute.

Schematic presentation of the chronocoulometric treatment during the ex situ IR RA spectroelectrochemical measurement. The spectra were measured after each chronocoulometric step (marked with arrows) but five of them are shown for comparison.

Ex situ IR RA spectra of the initial (solid line) and the most polarized (dotted line) spectra. The spectral region 4000–2500 cm−1 is shown in the inset.

Assignation of the bands (in cm−1) of BTMSE coatings in the IR RA spectra.

| IR RA (coating on Al; Li et al. 2009) | IR RA (coating on AA 2024; Rodošek et al. 2016) | Assignment | IR RA (coating on Al; Li et al. 2009) | IR RA (coating on AA 2024; Rodošek et al. 2016) | Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∼3369 m,b | ν(SiO–H), ν(OH)alc | 1073 w,sh | 1073 w,sh | ν(SiOSi) | |

| 2982 w | 2973 w | νa(CH3) | ν(SiOSi) | ||

| νs(Si–OCH3) | ν(SiOSi) | ||||

| 2932 vw | 2931 vw,sh | νa(CH2) | ν(CC), alc | ||

| 2914 w,sh | νs(CH3) | 931 m,b | ν(SiOAl) | ||

| 2894 w,b | 2891 w | νs(CH2) | 910 m | ν(Si–OH) | |

| 2848 vw | νs(Si–OCH3) | 822 w | γ(Si(CH2)) | ||

| 1641 w,b | δ(H2O) | 793 m,sh | γ(C(CH2)) | ||

| 1466 vw | δ(CH3) | 764 w | γ(CH2) | ||

| 1419 m | 1416 w | δ(CH2) | 705 w | ν(SiC) | |

| 1388 vw | δs(CH3) | 669 w,sh | ν(SiO3) | ||

| 1373 vw | ω(C(CH2)) | 548 vw | δs(SiOSi) | ||

| 1279 m | 1273 m | ω(Si(CH2)) | 483 m | δ(OSiO) | |

| 1230 vw | τ(CH2) | 467 m | δ(skeletal) | ||

| 1191 vs | 1162 s,sh | τ(CH2) | |||

| 1151 w | 1139 s | τ(CH2) |

s, strong; m, moderate; w, weak; v, very; sh, shoulder; ν, stretch; δ, deformation; ω, wag; τ, twist; γ, rock; alc, solvent vibration.

Similar changes in ex situ IR RA spectra were observed also for other sol–gel protective coatings (Fir et al. 2007; Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2017). However, it is not always easy to degrade the coatings and sometimes the changes are not visible in the ex situ spectra at all. Such case is also the coating on the basis of cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane, BTMSE and PFOTES (Rodošek et al. 2017).

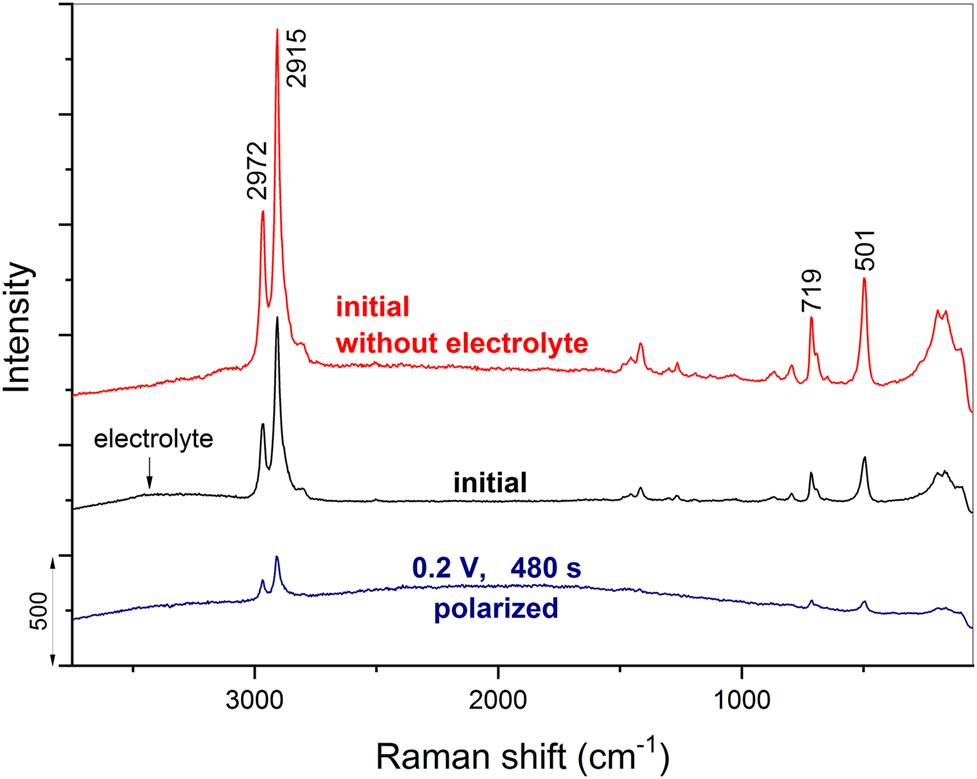

Raman spectroelectrochemistry demands thicker coatings to obtain signals. Consequently, coatings as used for other corrosion tests can be applied and – since they protect effective – it is extremely difficult to degrade them. Such coatings often remain unchanged at sites at which we start the single Raman spectra measurements, regardless whether the measurement is performed ex situ (Rauter et al. 2013) or in situ (Rodošek et al. 2014, 2017). This is why the bands in the Raman spectra often remain constant during chronocoulometric charging towards more positive potentials (Rauter et al. 2013; Rodošek et al. 2014, 2017). However, at certain sites on the coating the localized corrosion processes start slowly, but then the pits increase with increase in potential or prolongation of chronocoulometric treatment at certain potential (Rodošek et al. 2017). After reaching the final potential of polarization, we can find such damaged sites and record Raman spectra. The measurement of the single spectra close to pits reveals the decrease in the intensity of all Raman bands, as shown for polarized sol-gel/epoxy coating in Figure 8 (Rodošek et al. 2014). The initial Raman spectrum was first taken without and with electrolyte in the custom-made spectroelectrochemical cell and then after final polarization at 0.2 V for 480 s. Although some low-intensity bands can still be noted in this spectrum, all Raman bands disappear when the spectrum is recorded on the completely corroded areas (Rauter et al. 2013).

Raman spectra of the initial state of the sol–gel/epoxy coating without electrolyte and when positioned in the 0.5 M NaCl electrolyte in the custom-made in situ Raman spectroelectrochemical cell. The in situ spectrum recorded at the most polarized potential of 0.2 V (480 s) is shown as well.

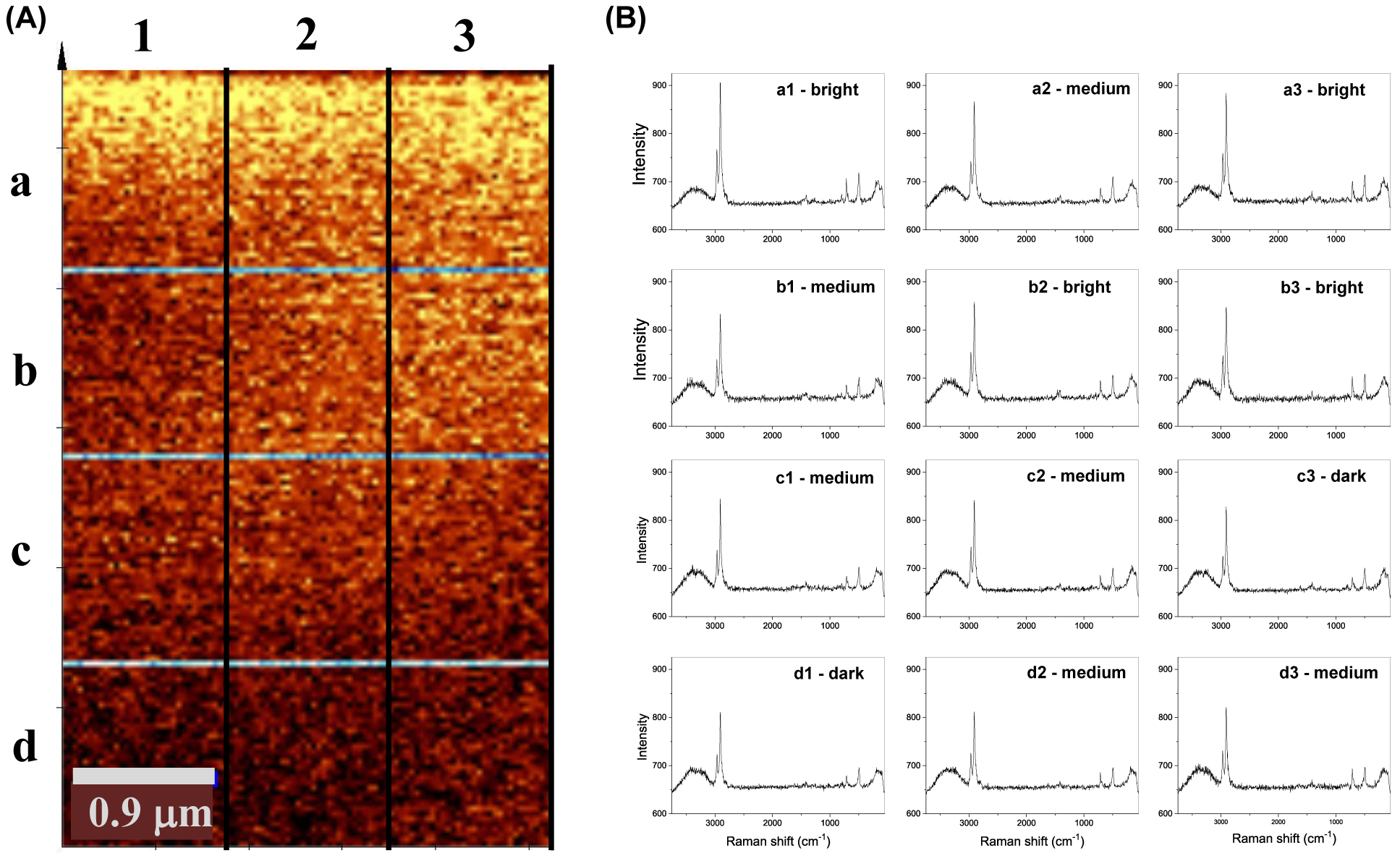

Raman imaging is another good analytical tool to get insight into the changes that occur in the coatings during corrosion processes. The image in Figure 9 was recorded after the polarization of sol-gel/epoxy coating to 0.2 V near the pit formation. Each color point in the image represents a Raman spectrum and some of them are shown for bright, medium or dark spots in different sections of the image (Figure 9). The color shades correlate with the intensity of the bands. Although the sol–gel/epoxy coating is still present at all sections of the image the intensity of the bands started to drop slowly in the sections closer to pit.

In situ Raman spectroelectrochemistry. (A) Raman image of the sol–gel/epoxy coating polarized at 0.2 V. (B) Raman spectra extracted from various sites (bright, medium, dark) in different sections of the image.

4 Conclusions

Two main aims were followed herein. Firstly, to compare the protective efficiency of sol-gel coatings made over the course of time from various trialkoxysilane precursors. Despite prepared in different studies they were tested in similar conditions. The second aim is to stress the benefits of the combined electrochemical and spectroscopic approaches.

The comparison of the trialkoxysilyl-based coatings revealed that the best protective efficiency was achieved for coatings prepared with predominantly PDMS chains. Especially effective is PDMSU coating in which the long building molecules align into quite regular structure. Such aligned molecules are not bonded only through the terminal trialkoxysilyl-functionalized groups but also via hydrogen bonds among urethane groups. These –NH–CO– urethane groups actually connect the central PDMS chain to the trialkoxysilyl terminal groups in the PDMSU molecule. The tight packaging of PDMSU molecules leads to compact and extremely protective coatings.

In addition, very good protective efficiency was noted for coatings based on cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane and BTMSE (Figure 5). BTMSE molecules are needed for excellent performance of these coatings since they positively influence the flexibility and – since they are small molecules – enable building into tight structure. Namely, coatings prepared from cyclic tetrasilsesquioxane only may show cracks in the structure due to rigidity of the bounded planar molecules. Moreover, since these molecules are large the structure of such coating to some extent remains permeable for water and other species that can cause corrosion.

Various types of spectroelectrochemistry can offer important insights into the changes that occur in materials during electrochemical treatment. Protective coatings against corrosion are a clear example. Specifically, vibrational spectroelectrochemistry is performed with the aim to degrade the coating at more and more positive potentials and spectroscopically detect the changes in the coating. Ex situ IR RA spectroscopy gives information on hydration of the coating, breakage of siloxane bonds and bonds between the coating and the aluminum alloy, as well the changes in the C–H spectral region. Besides, ex situ/in situ Raman spectroelectrochemistry can be used to follow the formation of pits during electrochemically forced degradation through Raman imaging.

Funding source: Javna Agencija za Raziskovalno Dejavnost RS

Award Identifier / Grant number: Programme P1-0030, Programme P2-0393, project L2-5484

Acknowledgements

Prof. Dr. Boris Orel is acknowledged as the initiator of the spectroelectrochemical measurements at National Institute of Chemistry in the early 1990s.

-

Author contributions: Angelja K. Surca collected the results and wrote the article. Mirjana Rodošek made experimental work.

-

Research funding: This study was financed by the Slovenian Research Agency (project L2-5484, programs P1-0030 and P2-0393).

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Beccaria, A.M. and Chiaruttini, L. (1999). The inhibitive action of metacryloxypropylmethoxysilane (MAOS) on aluminium corrosion in NaCl solutions. Corrosion Sci. 41: 885–899, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-938x(98)00161-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Bouali, A.C., Serdechnova, M., Blawert, C., Tedim, J., Ferreira, M.G.S., and Zheludkevich, M.L. (2020). Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) as functional materials for the corrosion protection of aluminum alloys: a review. Appl. Mater. Today 21: 100857, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmt.2020.100857.Suche in Google Scholar

Cabral, A., Duarte, R.G., Montemor, M.F., Zheludkevich, M.L., and Ferreira, M.G.S. (2005). Analytical characterization and corrosion behavior of bis-[triethoxysilylpropyl]tetrasulphide pre-treated AA2024-T3. Corrosion Sci. 47: 869–881, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2004.07.024.Suche in Google Scholar

Cambon, J.-B., Ansart, F., Bonino, J.-P., and Turq, V. (2012). Effect of cerium concentration on corrosion resistance and polymerization of hybrid sol-gel coating on martenisitic stainless steel. Prog. Org. Coating 75: 486–493, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2012.06.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Durig, J.R., Pan, C., and Guirgis, G.A. (2003). Spectra and structure of silicon containing compounds. XXXII.1 Raman and infrared spectra, conformational stability, vibrational assignment and ab initio calculations of n-propylsilane-d0 and Si-d3. Spectrochim. Acta A 59: 979–1002, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1386-1425(02)00263-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Eduok, U., Faye, O., and Szpunar, J. (2017). Recent developments and applications of protective silicone coatings: a review of PDMS functional materials. Prog. Org. Coating 111: 124–163, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2017.05.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Figueira, R.B., Fontinha, I.R., Silva, C.J.R., and Pereira, E.V. (2016). Hybrid sol-gel coatings: smart and green materials for corrosion mitigation. Coatings 6: 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings6010012.Suche in Google Scholar

Fir, M., Orel, B., Šurca Vuk, A., Vilčnik, A., Ješe, R., and Francetič, V. (2007). Corrosion studies and interfacial bonding of urea/poly(dimethylsiloxane) sol/gel hydrophobic coatings on AA 2024 aluminum alloy. Langmuir 23: 5505–5514, https://doi.org/10.1021/la062976g.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Greef, R., Peat, R., Peter, L., Pletcher, D., and Robinson, J. (1990). Instrumental methods in electrochemistry. Ellis Horwood Limited, New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Grosse, P. (1990). Conventional and unconventional infrared spectrometry and their quantitative interpretation. Vibr. Spectrosc. 1: 187–198, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0924-2031(90)80034-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Holze, R. (2004). Fundamentals and applications of near infrared spectroscopy in spectroelectrochemistry. J. Solid State Electrochem. 8: 982–997, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-004-0524-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Iwasita, T. and Nart, F.C. (1997). In situ infrared spectroscopy at electrochemical interfaces. Prog. Surf. Sci. 55: 271–340, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0079-6816(97)00032-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Jerman, I., Šurca Vuk, A., Koželj, M., Švegl, F., and Orel, B. (2011). Influence of amino functionalized POSS additive on the corrosion properties of (3-glycidoxypropyl)trimethoxysilane coatings on AA 2024 alloy. Prog. Org. Coating 72: 334–342, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2011.05.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Y.-S., Lu, W., Wang, Y., and Tran, T. (2009). Studies of (3-mercaptopropyl)trimethoxylsilane and bis(trimethoxysilyl)ethane sol-gel coating on copper and aluminum. Spectrochim. Acta A 73: 922–928, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2009.04.016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Li, Y.-S., Tran, T., Xu, Y., and Vecchio, N.E. (2006). Spectroscopic studies of trimethoxypropylsilane and bis(trimethoxysilyl)ethane sol-gel coatings on aluminum and copper. Spectrochim. Acta A 65: 779–786, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2005.12.040.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Mihelčič, M., Surca, A.K., and Gaberšček, M. (2017). Spectroscopical and electrochemical characterization of a (3-mercaptopropyl)trimethoxysilane-based protective coating on aluminium alloy 2024. Croat. Chem. Acta 90: 169–175.10.1016/j.molstruc.2004.06.007Suche in Google Scholar

Nunes, S.C., de Zea Bermudez, V., Ostrovskii, D., and Carlos, L.D. (2004). Ionic environment and hydrogen bonding in di-ureasil ormolytes doped with lithium triflate. J. Mol. Struct. 702: 39–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2004.06.007.Suche in Google Scholar

Rauter, A., Slemenik Perše, L., Orel, B., Bengű, B., Sunetci, O., and Šurca Vuk, A. (2013). Ex situ IR and Raman spectroscopy as a tool for studying the anticorrosion processes in (3-glycidoxypropyl)trimethoxysilane-based sol-gel coatings. J. Electroanal. Chem. 703: 97–107, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2013.05.015.Suche in Google Scholar

Rodošek, M., Koželj, M., Slemenik Perše, L., Cerc Korošec, R., Gaberšček, M., and Surca, A.K. (2017). Protective coatings for AA 2024 based on cyclotetrasiloxane and various alkoxysilanes. Corrosion Sci. 126: 55–68.10.1016/j.corsci.2015.10.008Suche in Google Scholar

Rodošek, M., Kreta, A., Gaberšček, M., and Šurca Vuk, A. (2016). Ex situ IR reflection–absorption and in situ AFM electrochemicalcharacterisation of the 1,2-bis(trimethoxysilyl)ethane-based protective coating on AA 2024 alloy. Corrosion Sci. 102: 186–199.10.1016/j.corsci.2014.04.019Suche in Google Scholar

Rodošek, M., Rauter, A., Slemenik Perše, L., Merl Kek, D., and Šurca Vuk, A. (2014). Vibrational and corrosion properties of oly(dimethylsiloxane)-based protective coatings for AA 2024 modified with nanosized polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane. Corrosion Sci. 85: 193–203.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2021.126958Suche in Google Scholar

Selegård, L., Poot, T., Eriksson, P., Palisaitis, J., Persson, P.O.Å., Hu, Z., and Uvdal, K. (2021). In-situ growth of cerium nanoparticles for chrome-free, corrosion resistant anodic coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 410: 126958.10.1021/j100223a018Suche in Google Scholar

Snyder, R.G. and Strauss, H.L. (1982). C–H stretching modes and the structure of n-alkyl chains. 1. Long, disordered chains. J. Phys. Chem. 86: 5145–5150, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100223a018.Suche in Google Scholar

Surca, A.K., Rauter, A., Rodošek, M., Slemenik Perše, L., Koželj, M., and Orel, B. (2017). Modified bis-(3-(3-(3-triethoxysilyl)propyl)thioureido)propyl terminated poly(dimethylsiloxane)/POSS protective coatings on AA 2024. Prog. Org. Coating 103: 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2016.11.023.Suche in Google Scholar

Surca, A., Rodolšek, M., Kreta, A., Mihelčič, M., and Gaberšček, M. (2018). In situ and ex situ electrochemical measurements: spectroelectrochemistry and atomic force microscopy. In: Delville, M. and Taubert, A. (Eds.). Hybrid organic-inorganic interfaces: towards advanced functional materials. Willey-VCH, pp. 793–838.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2008.04.018Suche in Google Scholar

Šurca Vuk, A., Fir, M., Ješe, R., Vilčnik, A., and Orel, B. (2008). Structural studies of sol-gel urea/polydimethylsiloxane barrier coatings and improvement of their corrosion inhibition by addition of various alkoxysilanes. Prog. Org. Coating 63: 123–132.10.1021/la00082a018Suche in Google Scholar

Van Oss, C.J., Good, R.J., and Chaudhury, M.K. (1998). Additive and nonadditive surface tension components and the interpretation of contact angles. Langmuir 4: 884–891.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2008.08.010Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, D. and Bierwagen, G.P. (2009). Sol-gel coatings on metals for corrosion protection. Prog. Org. Coating 64: 327–338, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2008.08.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Zadeh, M.A., van der Zwaag, S., and Garcia, S.J. (2016). Adhesion and long-term barrier restoration of intrinsic self-healing hybrid sol-gel coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8: 4126–4136.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2005.03.009Suche in Google Scholar

Zandi-Zand, R., Ershad-Langroudi, A., and Rahimi, A. (2005). Silica based organic-inorganic hybrid nanocomposite coatings for corrosion protection. Prog. Org. Coating 53: 286–291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2005.03.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhu, D. and van Ooij, W.J. (2004). Enhanced corrosion resistance of AA 2024-T3 and hot-dip galvanized steel using a mixture of bis-[ztriethoxysilylpropyl]tetrasulfide and bis-[trimethoxysilylpropyl]amine. Electrochim. Acta 49: 1113–1125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2003.10.023.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/corrrev-2022-0007).

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editor’s Note

- A demonstration of resilience

- Reviews

- Scanning electrochemical microscopy methods (SECM) and ion-selective microelectrodes for corrosion studies

- Corrosion inhibitors for AA6061 and AA6061-SiC composite in aggressive media: a review

- Original Articles

- Oxidation–reduction reactions and hydrogenation of steels of different structures in chloride-acetate solutions in the presence of iron sulfides

- The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: effect of immersion time and anti-corrosion activity of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution

- Corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions with different pH adjusted by ammonia

- Comparison of protective coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilanes and possibilities of spectroelectrochemical approaches for their investigation

- Corrosion behaviour OF HVOF deposited Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editor’s Note

- A demonstration of resilience

- Reviews

- Scanning electrochemical microscopy methods (SECM) and ion-selective microelectrodes for corrosion studies

- Corrosion inhibitors for AA6061 and AA6061-SiC composite in aggressive media: a review

- Original Articles

- Oxidation–reduction reactions and hydrogenation of steels of different structures in chloride-acetate solutions in the presence of iron sulfides

- The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: effect of immersion time and anti-corrosion activity of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution

- Corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions with different pH adjusted by ammonia

- Comparison of protective coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilanes and possibilities of spectroelectrochemical approaches for their investigation

- Corrosion behaviour OF HVOF deposited Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel