Abstract

In this study, Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings were deposited using high-velocity oxy-fuel (HVOF) thermal spray technique on a mild steel substrate. Corrosion tests like neutral salt spray (NSS) following (ASTM B-117) standard and immersion cycle test following ASTM G-31, ASTM G1-03, standards were carried out for Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel along with uncoated mild steel acting as a control. Both Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel were corrosion resistant as compared to uncoated mild steel. Raman analysis following the immersion cycle test inferred that uncoated mild steel had all forms of rust. While Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel developed very little rust. The characterization helped to understand the changes in the surface before and after tests. It was observed that both Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel had little corrosion degradation of surface as compared to uncoated mild steel. Suggesting that both coatings performed significantly better compared to uncoated mild steel in corrosive environments. Polarization and EIS tests of both coated and uncoated mild steel in a 3.5% NaCl medium helped to understand the behaviour of coatings over a range of frequencies. Both coated samples had high polarization potential Ecorr values and lower polarization current Icorr values as compared to uncoated mild steel. Inferring better performance of coatings in corrosive environments as compared to uncoated mild steel.

1 Introduction

Corrosion is a perennial problem in the world’s economic growth. According to a study conducted by NACE International on corrosion prevention for the year 2013, the world economy suffered an estimated 2.5 Trillion ($) US Trillion Dollars about 3.4% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) due to corrosion. Hence sensing the economic impact of the problem, the 24th of April is observed as world corrosion awareness day every year. Huge economic impact and climate hazards pose an enormous as well as a meritorious challenge to the scientific communities working in metallurgical industries to develop suitable coatings, which will subsequently lead to the prevention of metal loss due to corrosion (Boudellioua et al. 2019). Mild steel finds extensive usage in automotive, building-construction, oil and natural gas industries due to its relatively good mechanical properties and lower cost (Ojo et al. 2019; Stephen et al. 2019). Mild steel is corroded significantly in HCl and NaCl medium leading to its failure eventually (Brykała et al. 2015; Tiwari et al. 2012). A total of 215 people lost their lives and 1500 were injured, 1600 buildings were damaged in a sewer pipe explosion in Guadalajara, Mexico, in April of 1992 attributed to the failure steel pipeline caused due to corrosion (Popoola et al. 2014). Corrosion leads to the failure of parts, structures, machines, and pipelines which eventually have to be replaced lowering the efficiency of the system along with the eco-diversity challenges (Popoola et al. 2014).

Fabrication of coatings having different material properties to improve the performance of the component is an age-old approach and for the last several decades, deposition of coatings on Mild steel substrates by thermal spray is an industrially accepted process. Amongst the several thermal spray techniques, the high-velocity oxy-fuel spray (HVOF) has been widely used for tribological and corrosion-resistant applications. It has been reported that the chemical/thermal degradation of the coating material and the substrates in the HVOF process is lesser due to lower particle–flame interaction time (Das et al. 2018). It has been found to provide better surface adhesion, higher oxidation resistance, lower porosity, lesser coating time compared to the thermal Arc Spray process (Espallargas et al. 2008; Souza and Neville 2005; Ura-Bińczyk et al. 2019; Uusitalo et al. 2002). The HVOF based thermal spray technique is easy to operate and has excellent cost benefits making it a good option for coating mild steel pipes and sheets having intricate shapes.

Transition metals have been surface coated on mild steel for a variety of engineering applications and have been found to prevent the corrosion-erosion synergistic effects.

Fe and Zn have a standard electrode potential of −0.414 V and −0.762 V, respectively. Zn will corrode first, acting as a sacrificial coating to Fe in corrosive environments (Bai et al. 2017). Zinc forms a compound in a corrosion medium that is relatively stable and reduces the further rate of corrosion. Pola et al. (2020) observed Zn coatings increase the corrosion resistance of mild steel because zinc forms relative stable compounds and thereby restricts the movement of Cl− ions across the interface. Hashmi (2014) and Sadananda et al. (2021), reported that zinc alloy coatings increase the corrosion resistance manyfold as compared to pure zinc coatings on carbon steels. Hence use of zinc alloy coatings is widely used in automotive, construction, oil and natural gas industries involving mild steel usage. Sadananda et al. (2021) have observed that Zn increases the fatigue life of steel. Zn–Ni and Zn–Cu coatings are widely used among various alloys of zinc coatings in industries suffering because of corrosion (Bai et al. 2017; Bakhsheshi-Rad et al. 2017; Conde et al. 2011; Hu et al. 2009; Huang et al. 2019b; Li et al. 2019b; Matin et al. 2015; Oulmas et al. 2019). Zhai et al. (2019) found that Ni improved the performance of Zn–Ni coatings in sulphur reducing bacteria (Escherichia coli medium) preventing severe corrosion of steels.

Ni and Cu have standard electrode potential of (−0.26 and +0.52 V, respectively) and have been reported to reduce the penetration of Cl− ions into the interface necessary for corrosion propagation.

Both Ni and Cu have been reported to increase the yield strength and ultimate strength of the substrate being coated besides improving the corrosion resistance. Matin et al. (2015) have reported that Ni+ ions effectively inhibit the penetration of Cl− ions hence reducing the rate of corrosion thereby saving the underlying substrate from corrosion attack.

Zaki et al. (2017) found that Cu–Ni alloys coatings performed well in 0.5 M HCl environments, and also the presence of copper in coatings helps prevent bio-fouling hence chances of microbial induced corrosion (MIC) are largely reduced. Ni coatings have been used in place of chromium for corrosion prevention and for improving the binding strength of various coatings with substate hence acting as a binder (Bai et al. 2017; Jena et al. 2020; Krishna et al. 2019; Kwon et al. 2016; Li et al. 2019a).

Kumar et al. (2019), investigated that TiB2 could be used for effective corrosion resistance. Ti is an excellent hard metal for coating in erosion and wear-related applications along with its borides like TiBN. TiB2 has been reported to show excellent corrosion resistance. However, TiB2 being very hard has been reported to exhibit delamination with the substrate in absence of a binder element hence the incorporation of a binder into the coating becomes indispensable (Boudellioua et al. 2019; May 2016; Mazumder 2020).

Considering the above-mentioned discussion and the effective usage of the elements against corrosion, it was decided to surface coat the mild steel using the HVOF process with Zn, Ni, Cu, TiB2, with two compositions (Zn – 85%, Ni – 5%, Cu – 10%) and (Zn – 80%, Ni – 5%, Cu – 5%, TiB2 – 10%), by weight respectively and investigate their performance in corrosive medium and compare to uncoated mild steel. Zn being the major component in the coating would act as a sacrificial anode and form corrosion products like ZnOH2, ZnCl2 would prevent the underlying surface from being corroded and reduce the rate of corrosion and movement of Cl−ions across the interface. Ni primarily would act as a binder and help in the adhesion of coating with the substrate surface. Cu incorporation would help to prevent bio-fouling hence reducing the chances of microbial induced corrosion (MIC). TiB2 incorporation would help in hardness improvement and corrosion resistance.

Since no data is available on the corrosion behaviour of HVOF sprayed Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel in corrosive environments. This inspired us to undertake this work and understand the effect of various alloying elements on corrosion behaviour.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Specimen cutting

Mild steel sheet used as substrate material was cut into small coupons using wire electrical discharge machining (EDM) having specimen sizes of (101.6 mm × 63.5 mm × 2 mm). Subsequently, the coupons were grit blasted to clean the substrates and increase effective surface area for improvement of surface adhesion. Before HVOF deposition, the substrates were cleaned ultrasonically in acetone at 30 °C for 15 min for removing impurities if any.

2.2 Preparation of composite coating powder

To prepare the composite coatings, pure copper, nickel, zinc and TiB2 powder with 99% purity were taken in the calculated amount and two formulations were made. In coating 1 formulation the composition of the coating was made as (Zn – 85%, Ni – 10%, Cu – 5%, by weight) and for coating 2 formulation, the composition was (Zn – 80%, Ni – 5%, Cu – 5%, TiB2 – 10%) by weight. The required amount of individual powder was weighed using an electronic balance (Sartorius make). Subsequently, the powders were mixed using a vibratory cup mill and stored in a sealed container to avoid any contamination or moisture ingress.

2.3 Coating procedure

HVOF (MEC, Jodhpur) The Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steels were fabricated using HVOF (HIPOJET, MEC, Jodhpur, India). Before thermal spraying, all the components of equipment that were related to powder flow were thoroughly cleaned. All the coatings were fabricated under identical temperatures and pressure with the same operating parameters. The mild steel specimens were fixed in the coupon holder. The powder was fed into the hopper after achieving the required flame and flow the feeder input started. Multi-pass coating was made to reduce porosity and get the uniform thickness of the coating. The process parameters are given in Table 1.

Process parameters of the HVOF coating procedure.

| S. no. | Process parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gas pressure (LPG) | 6 bar |

| 2 | Powder flow rate | 40 g/min |

| 3 | Oxygen pressure | 6 bar |

| 4 | Air compressor pressure | 6 bar |

| 5 | RPM of powder feed disc | 120 |

| 6 | Standoff distance | 130 mm |

| 7 | Temperature of LPG mixer tank | 80 °C |

| 8 | Fuel air ratio (LPG/oxygen) | 5:1 |

2.4 The thickness of coated samples

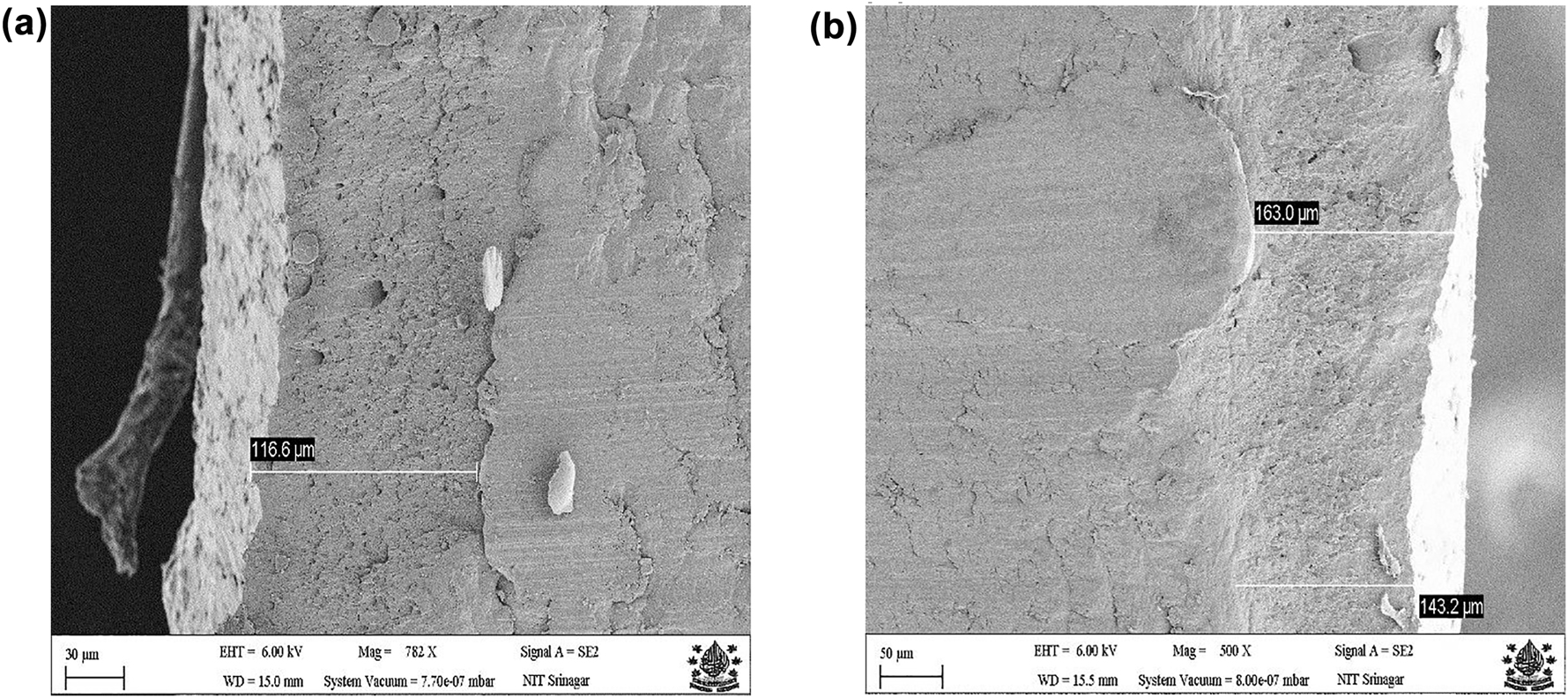

The thickness of each coated specimen was measured using a digital coating thickness gauge (Automation, Fischer, Germany) and the coating thickness of Zn–Ni–Cu coated coupons was 116.6 µm and for the Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coupons it was 143.2 µm. However, the variation in the coating is along the surface. The accuracy of the measurement was ±1 µm. The variation in coating thickness is due to the manual control of the spray gun movement. Figure 1a and b shows the cross-sectional field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) analysis of Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel respectively.

Cross-sectional FESEM image of (a) of of Zn–Ni–Cu; (b) Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel specimens.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of uncoated surface

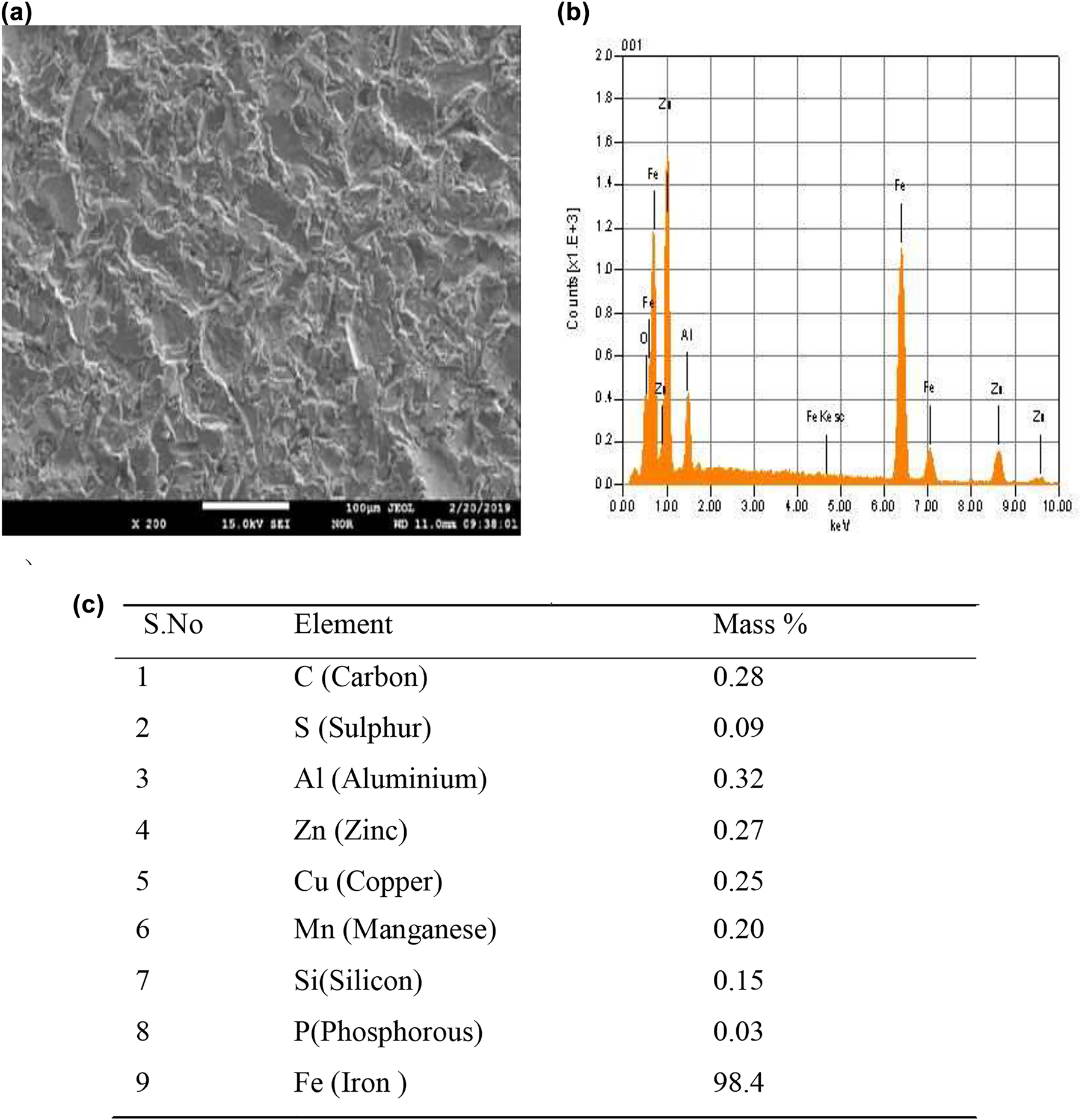

The uncoated coupon subjected to EPMA is attached with EDS (JEOL EDS System, Japan) and the results are shown in Figure 2.

Grit blasted uncoated mild steel surface (a) EPMA image, (b) Elemental micrograph, and (c) Mass % age of elements at X-200.

3.2 Characterization of coated samples

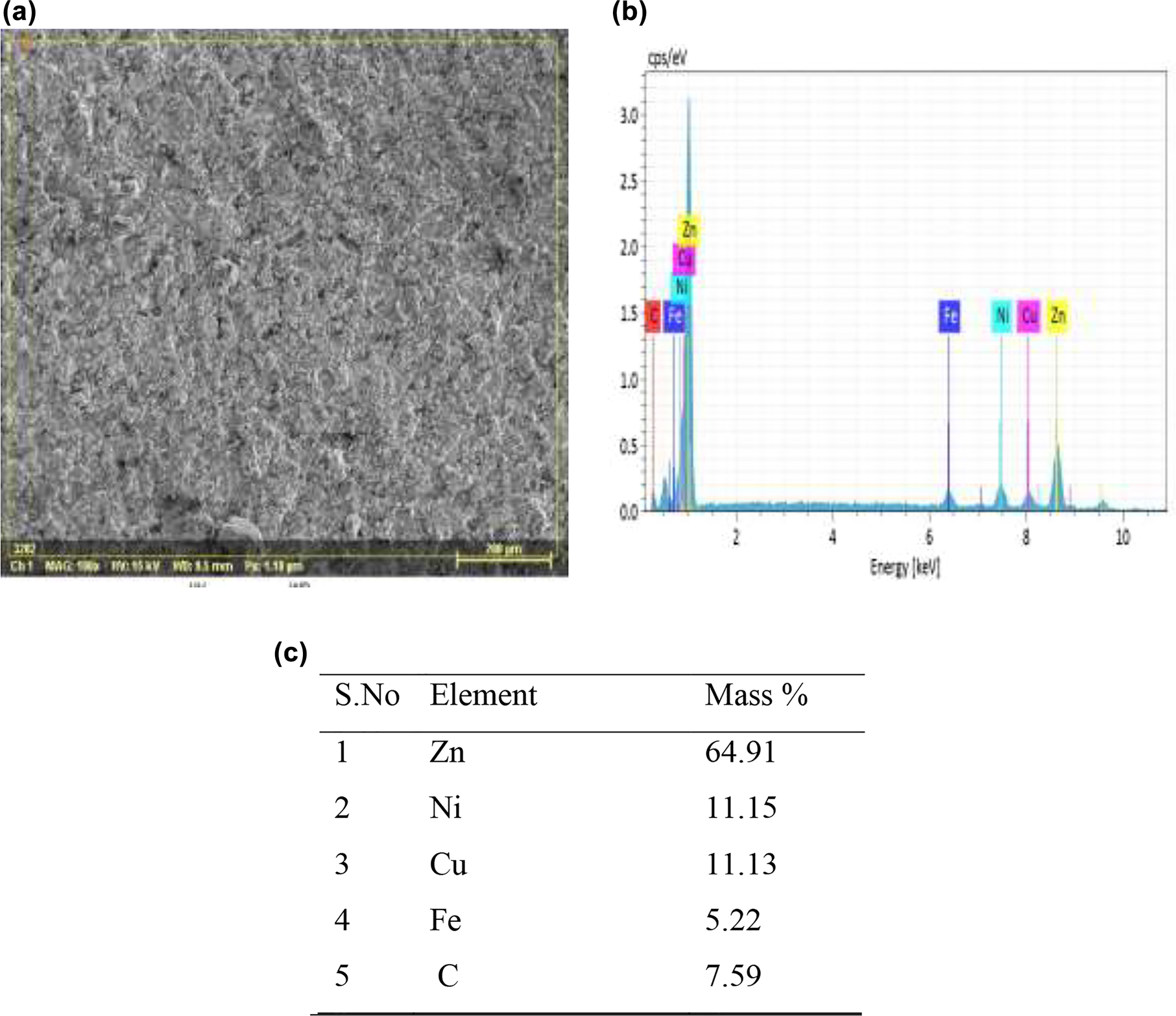

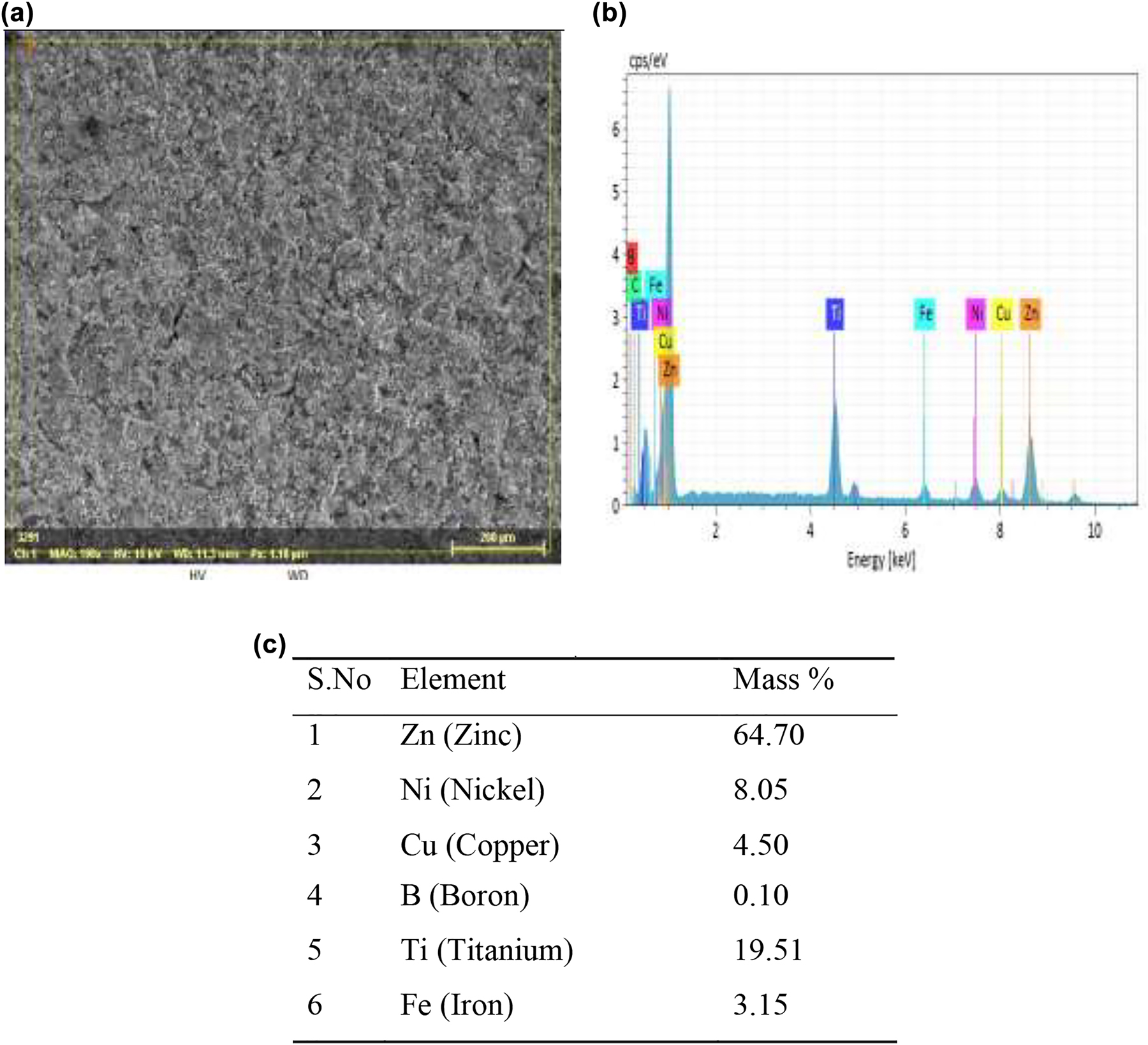

The surface morphologies of coated specimens were observed using scanning electron microscope (SEM; Hitachi S300) coupled with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS; EDAX, USA Apollo 40).

The SEM studies showed that the coatings were well developed and uneven due to manual application and showed little porosity. While EDS showed elemental analysis authenticating the presence of coated elements on the coated surface. SEM/EDS micrographs of both (Zn–Ni–Cu) and (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2) are given in Figures 3 and 4. EDAX analysis showed that no foreign contamination was present on the coated surface.

Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel surface (a) SEM image, (b) Elemental micrograph, and (c) Mass % age of elements at X-200.

Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel surface (a) SEM image, (b) Elemental micrograph, and (c) Mass % age of elements at X-200.

4 Corrosion tests

To determine the effectiveness of coatings, uncoated/coated samples were subjected to similar corrosion tests.

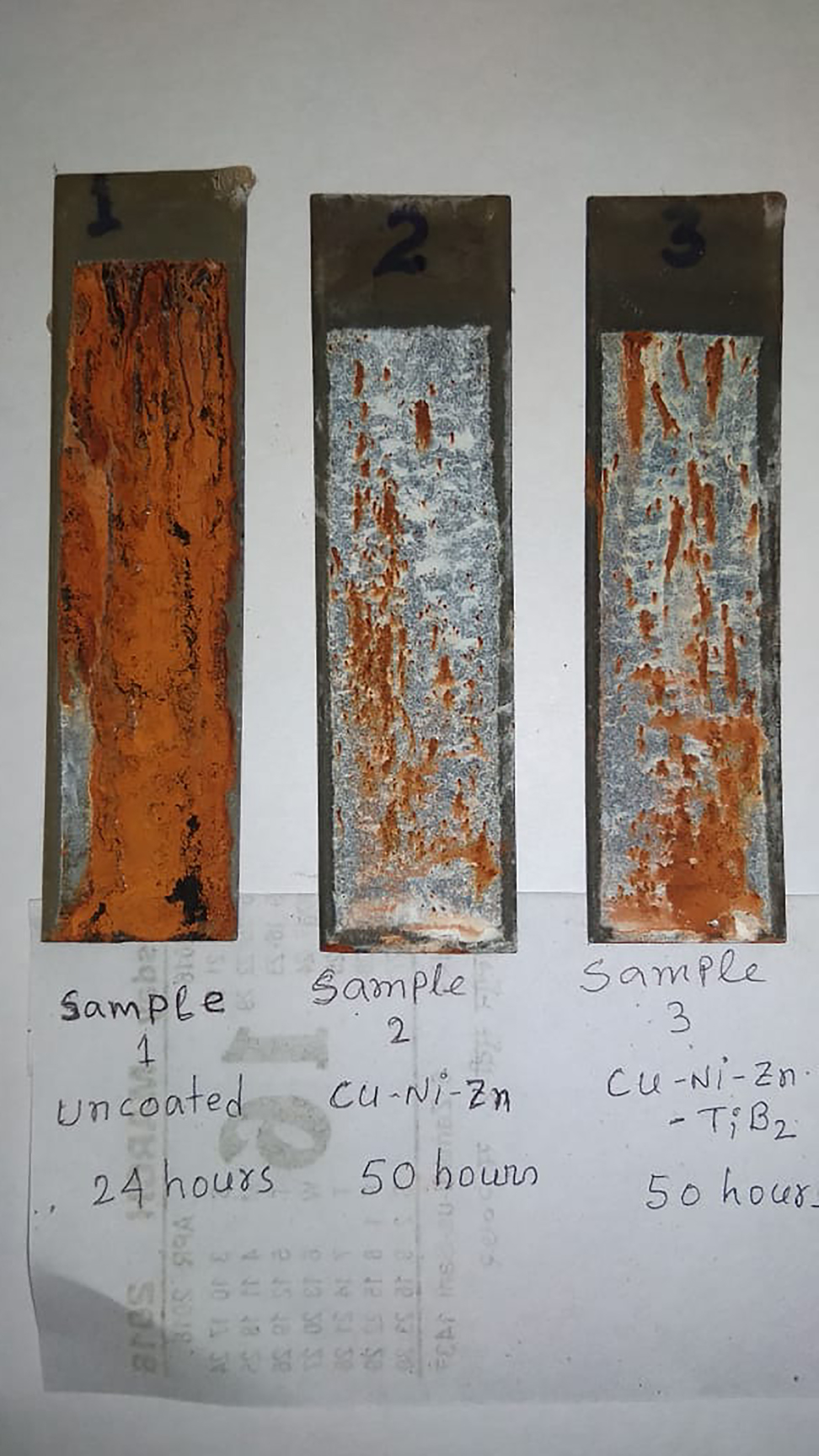

4.1 Neutral salt spray test

NSS was carried out on uncoated mild steel specimen 1 along with specimen 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel) and specimen 3 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel) all having sizes (101.6 mm × 63.5 mm × 2 mm) following ASTM – B117 procedure. The experiment was repeated two times to minimization of errors. The tests were conducted at 25 °C temperature throughout. After necessary edge protection by wax, the specimens were kept inside a salt spray chamber; saltwater in the form of gaseous vapour was generated with the help of compressed air and nozzles, which created a salt fog (5% NaCl) inside the chamber leading to the extremely corrosive environment for specimens. The results obtained were quite encouraging. Brown Rust developed in uncoated mild steel specimen 1 within 24 h while for specimen 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel) and specimen 3 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel), it developed at 50 h only at specific zones and did not cover the complete surface of specimens 2 and 3. Salt fog initiated a corrosion attack on the coated surface where pits/pores were present which may be attributed due to the porous nature of coatings formed by the HVOF process (Chen et al. 2014; Murmu et al. 2019; Shourgeshty et al. 2017; Ura-Bińczyk et al. 2019). The enhanced red/brown rust in specimen 3 (Cu–Ni–Zn–TiB2 on mild steel) at zone 2 can be attributed to the porous coating at zone 2. Figure 5 shows the result of the NSS conducted.

NSS of uncoated and coated specimens.

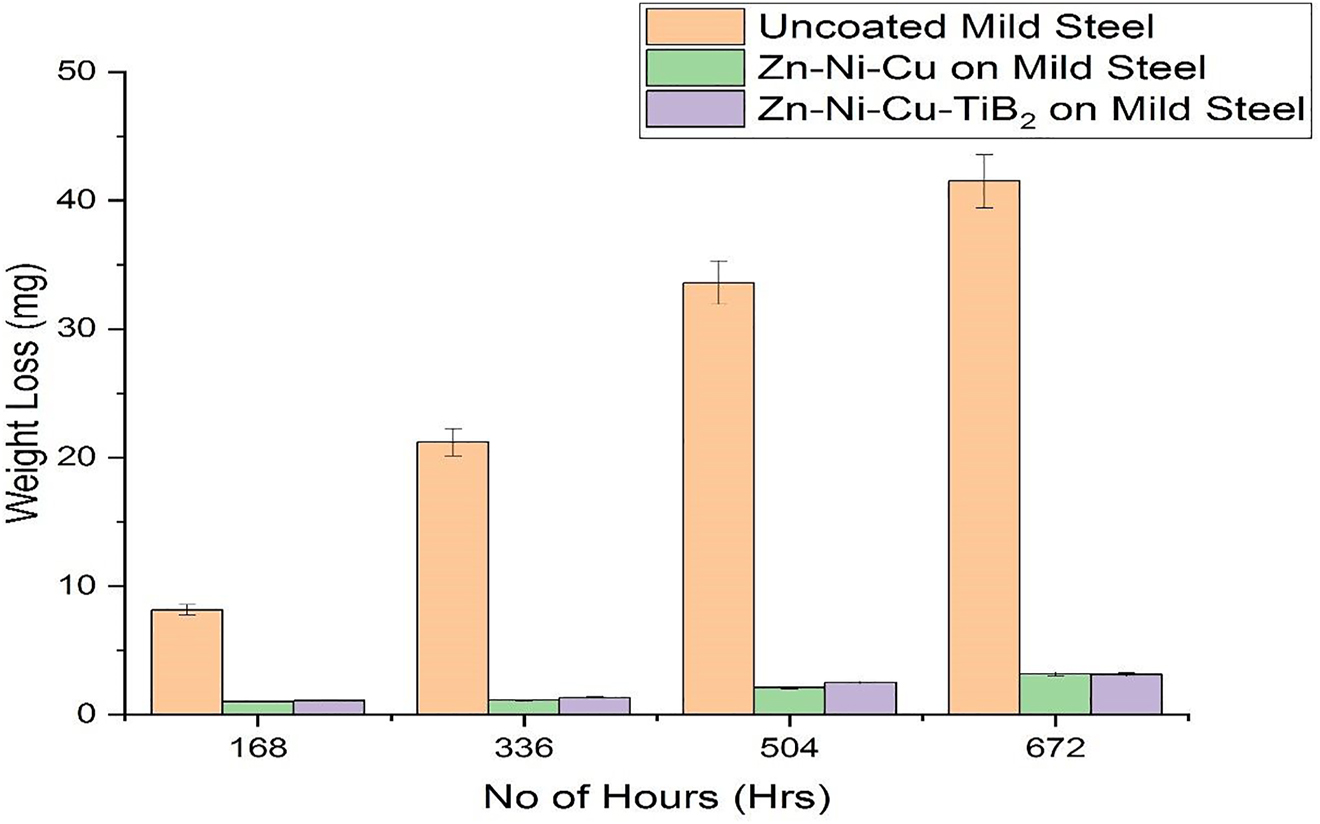

4.2 Weight loss experiment/immersion cycle test

It has been reported that 3.5% of NaCl is more corrosive to carbon steel than seawater. This is the reason why 3.5% NaCl is readily used in laboratories to check the effectiveness of anti-corrosive coatings (Meymian et al. 2020). The experiment was repeated two times for minimization of errors after necessary edge protection using wax on both specimen 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel) and specimen 3 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel) along with specimen 1 (uncoated mild steel). The size of all samples was kept constant having size (101.6 mm × 63.5 mm × 2 mm). The density for mild steel is (7.87 g/cm3), and the samples were weighed using an electronic weighing balance (SHIMADZU, LIBROR AEG-120). A 3.5% NaCl solution was prepared following the ASTM G-31 procedure. The tests were conducted at 25 °C throughout. Later on, specimens 1, 2, and 3 were dipped at the same time in beakers containing 3.5% NaCl solution for a period of 672 h (28 days). The specimens were removed following the ASTM G1-03 procedure (Chen et al. 2014; Kumar et al. 2019), after every (7 days, 196 h) cleaned with distilled water, dried, weighed and again put back. The salt solution changed every 7 days with pH measured with a pH meter (P-100 Cole Parmer) before and after replacement. And it was found that pH at the start was 6.8 and after 7 days it reduced to 6.4 this slight reduction is due to the reaction of Cl− with Zn, Cu, Ni and henceforth released from the coating into the solution. Similar findings of pH reduction were also reported (Fadl-Allah et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2020). All specimens showed mass loss but specimen 1 (uncoated mild steel) showed an appreciable amount of mass loss in 3.5% NaCl. Also, corrosion of mild steel in higher concentrations like 5% NaCl has been reported to show a lower mass loss for mild steel specimens possibly due to higher viscosity of solution leading to the formation of dimer hence the lower movement of Cl− ions (Espallargas et al. 2008; Fenker et al. 2014; Souza and Neville 2005; Ura-Bińczyk et al. 2019; Uusitalo et al. 2002; Zheng et al. 2020). This is the reason why a 3.5 % NaCl solution was used for the test. Specimen 1 showed white flakes (due to the formation of Lepidocrocite having a sandy like structure) (Matin et al. 2015), during the first 12 h of immersion. The uncoated MS specimen had black patches on the surface possibly due to the formation of an oxide layer after 36 h which later turned into red/dark brown patches (flakes and blisters, showing the presence of ferric hydroxide) after 7 days of immersion, Fe(OH)2 formed on the surface of metal does not protect the metal (Matin et al. 2015). It can be seen from graph no. 1 that the mass-loss rate increased after every 7 days because after removal the specimens were dried and this led to NaCl being left over at the surface which increased corrosion attack later. Complete rusting occurred with even the colour of salt solution turning into yellowish-brown indicating the presence of lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH). Goethite, (with small sediments of red oxide confirming the presence of lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH). Black rust particles indicate the presence of magnetite (Fe3O4) suspended in solution (Huang et al. 2019a; Surnam et al. 2016). For specimen 1 (uncoated mild steel) mass loss was recorded as 40.1 mg at the end of the experiment. While specimens 2 and 3 showed white flakes appearance after 10 days of immersion and little pores of red rust after 15 days of immersion. The mass loss of specimen 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel) recorded was 3.13 mg, while for specimen 3, (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel) was recorded as 3.15 mg at the end of the experiment. The average values of mass loss are expressed as the experiment was repeated. Similarly, from the above data corrosion rate of every specimen was calculated using the equation

where W = mass loss of specimen in mg; A = area of specimen (exposed area to corrosion solution) in inch2; T = time of exposure in h; ρ = density of material in g/cm3.

Using Eq. (1) corrosion rate calculated for specimen 1 is 0.411 mpy. For specimen 2 is 0.0321 mpy. Moreover, for specimen 3 as 0.0323 mpy coating efficiency for specimens 2 and 3 was calculated using the equation

Using Eq. (2) coating efficiency for specimen 2 is 92.19%. Moreover, for specimen 3 it is 92.14%. High coating efficiency is because of the dense nature of coating by the HVOF process, which limits corrosion attack hence the mass loss is significantly less in both coated specimens (Popoola et al. 2014). As the porosity of HVOF coatings is generally less than 1% (Fadl-Allah et al. 2016; Zaki et al. 2017), it can be the reason for lower mass loss and lower corrosion attack. While Zn acts as a sacrificial layer by forming insoluble Zn (OH)2. The minimum mass loss in both coatings may be because of Zn, which protects the MS substrate from Cl−attack by acting as cathodic protection (Meymian et al. 2020; Surnam et al. 2016). It proves that coating helps to reduce corrosion of substrate by acting as a barrier between the substrate and corrosive medium. All the components of coating Cu, Ni and TiB2 have excellent corrosion resistivity while even after getting consumed give rise to oxidative coating and barrier coating hence masking active sites of the substrate from Cl−ions, preventing it to attack the Fe hence saving substrate. Quantitative results of the immersion cycle test are given in Table 2. Graphical results of the immersion cycle test in 3.5% NaCl are shown in Figure 6.

Weight loss, corrosion rate and coating efficiency in 3.5% NaCl solution for 28 days (672 h).

| Specimen | Weight loss (mg) | Cr (mpy) | Coating efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncoated MS (specimen 1) | 40.1 | 0.411 | |

| Coated specimen (Cu–Ni–Zn on mild steel) specimen 2 | 3.13 | 0.0321 | 92.19 |

| Coated specimen (Cu–Ni–Zn–TiB2 on mild steel) specimen 3 | 3.15 | 0.0323 | 92.14 |

Weight loss graph of uncoated/coated specimens of mild steel.

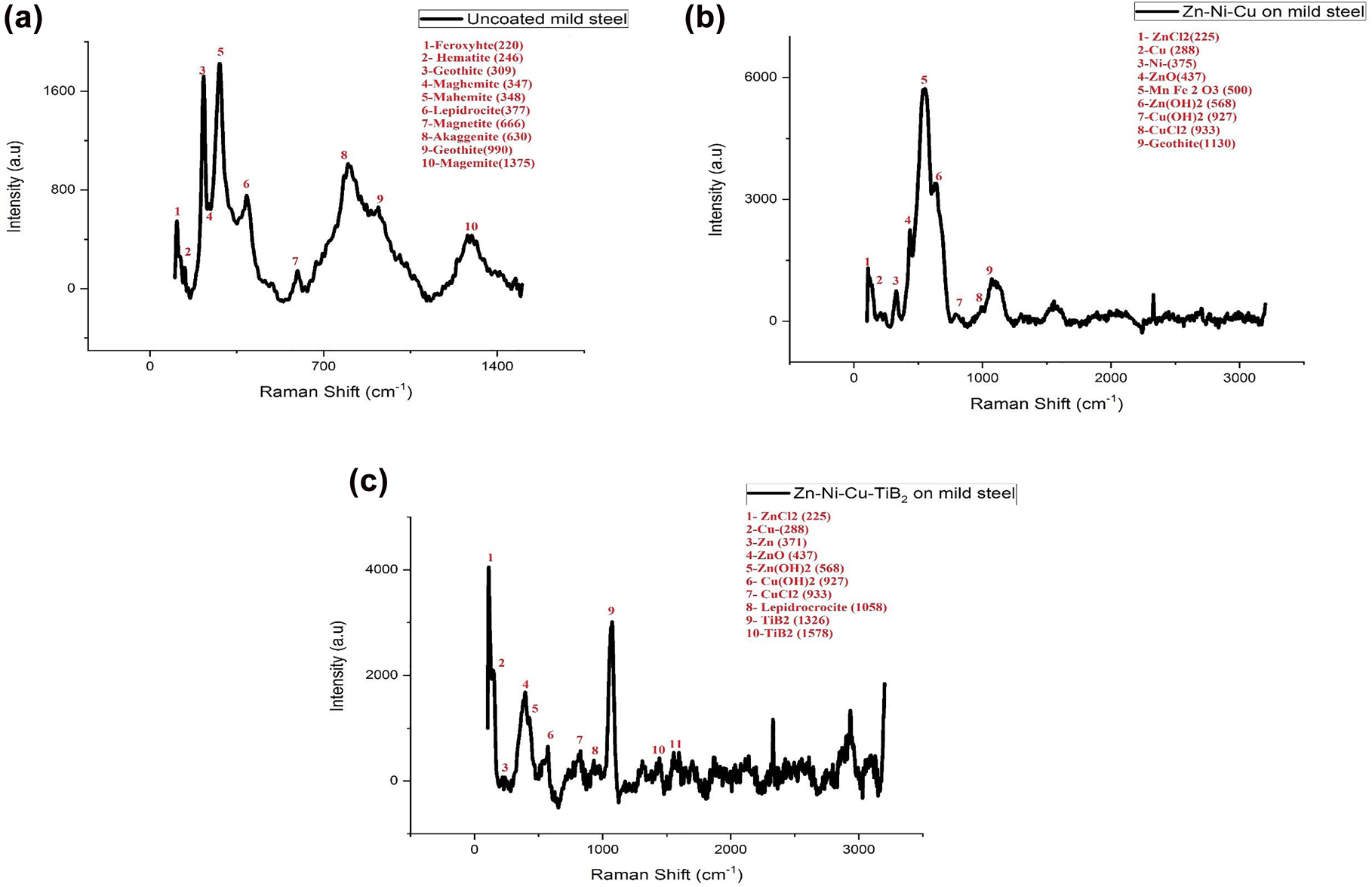

4.2.1 Raman spectrometry analysis after the immersion cycle test

Specimen 1 (uncoated mild steel), specimen 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu on M.S) and specimen 3 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on M.S) were taken out from 3.5% NaCl solution after 28 days (672) h, dried and later subjected to Raman spectrometry analysis using (Renishaw Invia Raman microscope) to get a better insight about the rust constituents and phases developed on the specimen surface. Raman spectroscopy has a low-frequency range hence beneficial to comprehending the typography of rust (Brykała et al. 2015; Meymian et al. 2020).

For specimen 1, high-intensity Raman bands are observed at 220, 309, 345, 347, 377, 730 and 990 cm−1 inferring the presence of various corrosion products such as feroxyhyte, goethite, maghemite, lepidocrocite, akaganite and goethite (Leckraj and Surnam 2017) are shown in Figure 6a. Chemical reactions responsible for the formation of various kinds of rust are as under.

Overall the reaction as

For coated specimen 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu on MS) the Raman peaks are observed at (437,500, 568) corresponding to ZnO, Mn-rich bixbyite ((MnFe)2 O3) (3), Zn(OH)2, respectively while moderate-intensity peaks at 225, 288, 342 corresponding to ZnCl2, Cu and Ni, respectively (Leckraj and Surnam 2017). As shown in Figure 7, high Raman peaks correspond to the products of zinc with water, clearly stating that Zn and Cu got readily consumed in solution and formed an oxide layer but prevented Cl− from entering inside the coating and reaching the substrate to start corrosion. Ni from the coating helps to stabilize Zn(OH)2 preventing it to transform ZnO which is highly unstable and highly electric conducting and prone to corrosion attack (Deepak et al. 2019). Meymian et al. (2020) have also found that the incorporation of Ni with Zn increases its corrosion resistance. As shown in Figure 7b. Chemical reactions for various kinds of rust products are given under

And coated specimen 3 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on MS) maximum intensity peaks at (225,288, 375, 1058) Corresponding to ZnCl2, Cu, Ni and lepidocrocite (ϒ – FeOOH), respectively. While moderate-intensity peaks were recorded at (437, 568, 1326, 1573) corresponding to ZnO, Zn(OH)2, TiB2 and TiB2, respectively (Deepak et al. 2019) shown in Figure 7c. Here only one corrosion rust peak of lepidocrocite is present possibly due to pitting corrosion. Chemical reactions for various kinds of rust products are as under

Raman spectroscopy analysis of (a) uncoated mild steel, (b) coating 1 (Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel), and (c) coating 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel) specimens.

It is clear from above that coating 1 (Zn–Ni–Cu) and coating 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2) effectively prevent corrosion of mild steel even after being immersed in 3.5% NaCl solution for 28 days (672 h), because the rust constituents and their peaks are lower compared to uncoated mild steel.

The mechanism of corrosion protection offered by coatings is of two types (1) sacrificial barrier protection and (2) barrier effect protection. The sacrificial barrier effect is provided by zinc and Cu which reacts with Cl− and OH – ions and forms products like Zn(OH)2 and ZnCl2, Cu(OH)2 as shown in Eqs (6) and (7) which inhibit the further propagation of Cl− and OH− ions into the interface thereby saving the substrate against corrosion attack in coating 1. In coating 2 in addition to protection provided by Zn, Cu, Ti also helps in corrosion protection by acting as sacrificial as well as barrier effect. Here it is to be noted that TiO2, act as a protective film and saves the underlying substrate from corrosion attack. As far barrier effect is concerned it is amply provided by Cu, Ni, TiB2 particles. which prevents of movement of Cl− and OH− ions into the interface.

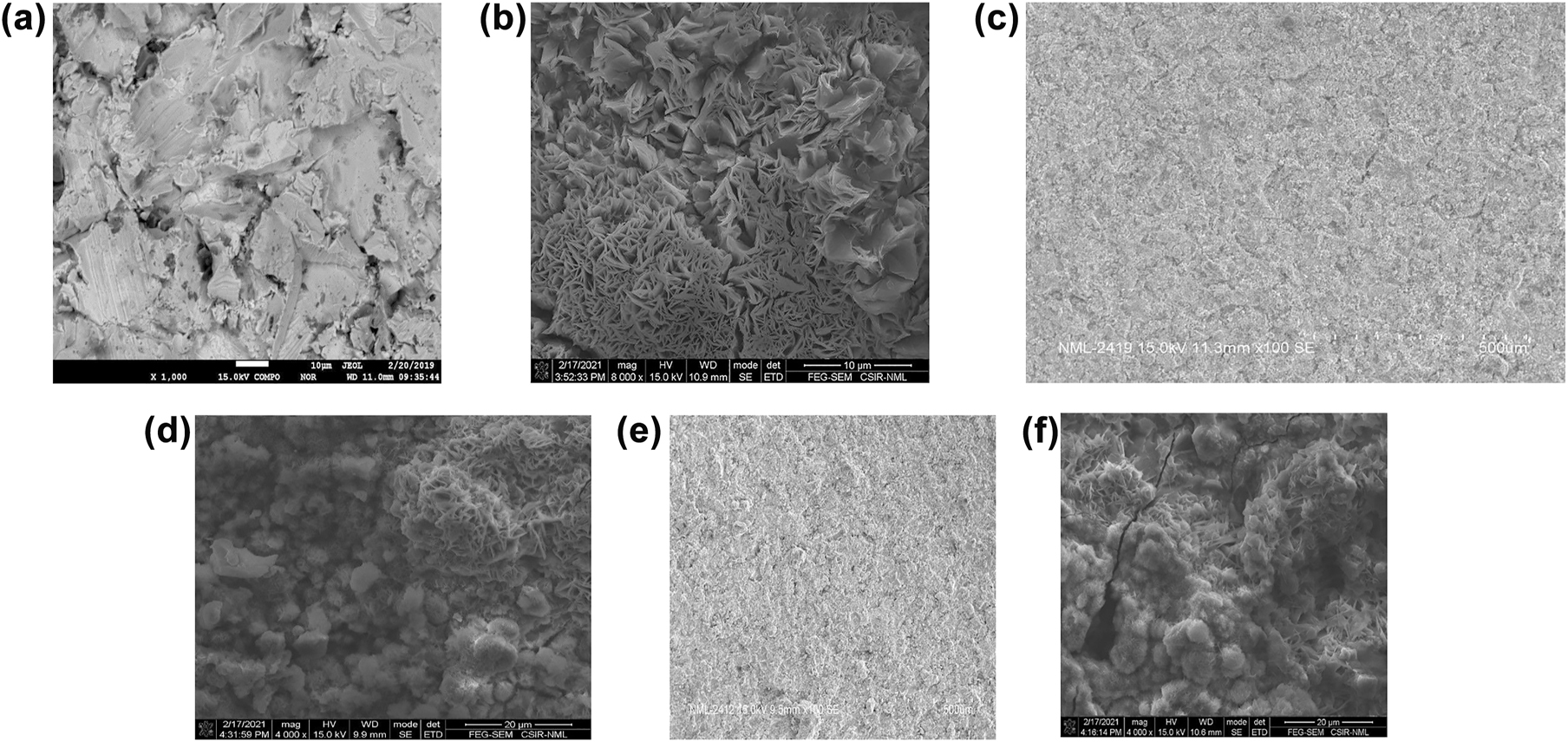

4.2.2 Surface analysis

To have a deeper surface analysis of corrosion mechanism on coatings, FEG-SEM (NOVA-NANO-SEM 430 coupled to EDAX-TSL) and FESEM (Gemini SEM 500) analysis was undertaken on samples before and after the immersion cycle test. The surface morphology of the uncoated mild steel sample showed a phenomenal change indicating the least effective its corrosion resistance is. On the other hand, Zn–Ni–Cu on MS and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on MS showed significant resistance to corrosion attack from Cl− ions of NaCl solution. Providing a masking effect on mild steel surface and significantly reducing the corrosion propagation. Some localized corrosion can be seen on coated surfaces mainly. Attributed due to the porous nature of the HVOF coating. Figure 8a and b and Figure 9a–f give a detailed analysis of surfaces post immersion cycle test.

FESEM analysis of uncoated mild steel (a) specimen showing corroded/uncorroded uncoated surface (b) high resolution image of corroded uncoated mild steel.

HR-SEM of (a) uncoated mild steel before immersion cycle test; (b) uncoated mild steel after immersion cycle; (c) Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel before immersion cycle test; (d) Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel after immersion cycle test; (e) Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel before immersion cycle test; (f) Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel after immersion cycle test.

5 Potentiodynamic polarization study

Potentiodynamic polarization was carried out on uncoated mild steel specimen 1 and coated specimens 2 and 3 (Zn–Ni–Cu & Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel) having an equal dimension of (101.6 mm × 63.5 mm × 2 mm) using (BioLogic SP-200) and analysed using EC-Lab (V10.40) using a conventional three-electrode setup. The reference electrode taken was platinum and the auxiliary electrode was graphite. The working area of the cell was 10 mm2. No aeration and striation were used and an experiment was conducted at NTP using 3.5%NaCl solution. Specimens 1, 2 and 3 were immersed in 3.5% NaCl solution 30 min before the EIS test start to stabilize the O.C.P (open circuit potential). The process parameters were set as shown below in Table 3.

Process parameters of the potentiodynamic polarization study.

| S. no. | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Frequency range | 1 kHz to 0.01 MHz |

| 2 | AC voltage | −5 to +5 mV |

| 3 | Halt time | 30 min |

| 4 | Potentiodynamic polarization | 0.167 m V/s |

| 5 | Temperatures of test | 25 °C |

| 6 | Dimension of specimens | 101.6 mm × 63.5 mm × 2 mm |

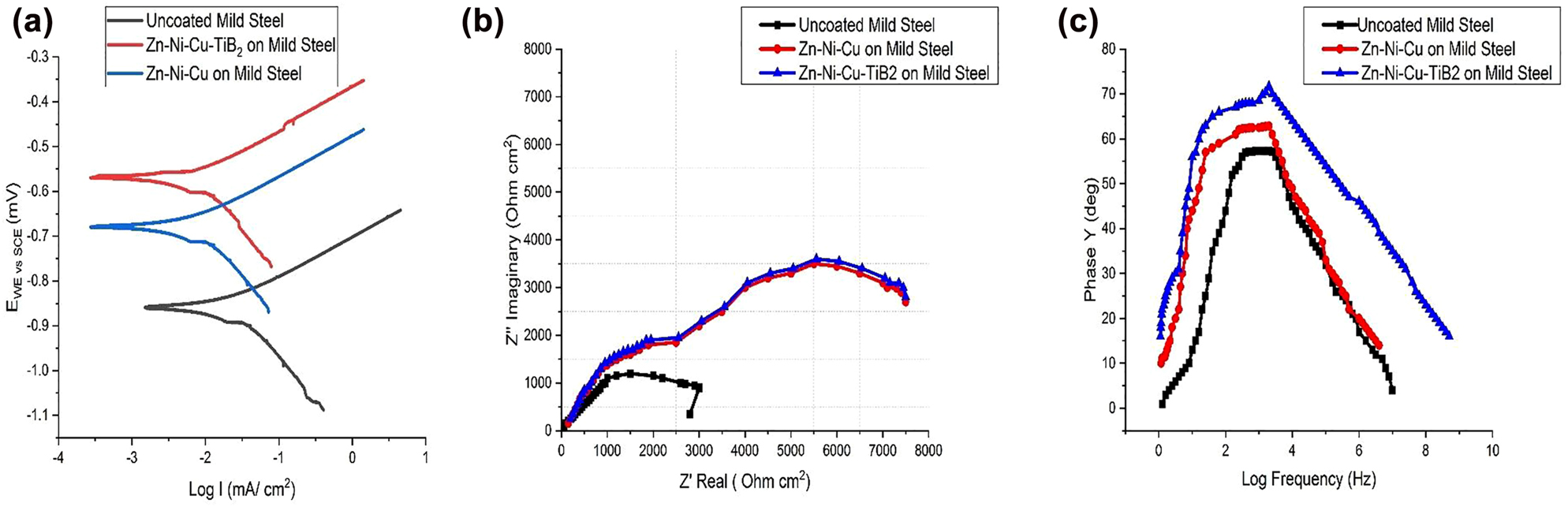

5.1 Tafel plots

Potentiodynamic behaviour of uncoated mild steel, coating 1 (Zn–Ni–Cu on MS) and coating 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on MS) was investigated for Ecorr and Icorr values by Tafel exploration technique and are shown in Table 4. It was observed that coating 1 and coating 2 showed higher Ecorr values compared to uncoated mild steel specimens. Icorr values of both coating 1 and coating 2 were less as compared to uncoated mild steel specimen inferring both coatings are acting as a barrier for Cl− ions transfer across the surface. Icorr values have been reported to have an inverse relationship with polarization resistance of coating inferring that for the coating to be corrosion resistant lesser Icorr values should be recorded (Deepak et al. 2019). The abrupt rise in the oxidation curve of coating 2 on MS is because of the presence of pores. The hydrated titanium oxide layer has been reported to act as a protected layer in neutral NaCl (Antunes et al. 2003). The Tafel curves are shown in Figure 10a. Our results are in agreement with the reports for Zn–Mg on mild steel by La et al. (2018) and Popczyk and Budniok (2010) for Zn–Ni coatings; Zhai et al. (2019) for multilayered Zn–Ni coatings; Bhat et al. (2020) for Zn–Ni–Co coatings; Sadananda et al. (2021) for Zn–Ni (Ni − 10%, Zn 90%) coatings.

Values of the Tafel, Nyquist, Bode plots.

| S. no. | Specimen | E corr (mV) | I corr (mA/cm2) | β A (mv/dec) | β C (mv/dec) | R ct (Ω cm2) | C dl (Fcm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uncoated mild steel | −0.85 | −1.03 | 185.55 | 364.5 | 1500 | 47.4 |

| 2 | Zn-Ni-Cu coated mild steel | −0.68 | −3.35 | 162.5 | 81.2 | 3455 | 44.02 |

| 3 | Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel | −0.58 | −3.34 | 159.8 | 79.0 | 3511 | 41.5 |

Potentiodynamic and EIS results of uncoated/coated surface (a) Tafel plot showing uncoated/coated specimens, (b) Nyquist plot showing uncoated /coated specimens, and (c) Bode plots of showing uncoated /coated specimens.

5.2 Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study

EIS of all specimens were carried out under similar conditions and each experiment was repeated three times to minimize errors. The temperature of the system was maintained at 25 °C throughout. The results obtained are given in Table 4. Nyquist plots were obtained to know the effect of polarization at higher frequencies on coatings and have a better insight into coatings. Nyquist curves for both coatings 1 and 2 showed a decline curve over the entire frequency response indicating higher corrosion resistance compared to uncoated MS. The semi-circular behaviour of coated samples at higher may be attributed to the porous nature of coatings. The Nyquist curves of uncoated MS, coating 1 and coating 2 are given in Figure 10b.

For understanding the behaviour of coatings at lower and medium frequencies bode, plots were obtained and are shown in Figure 10c. It can be seen that coated samples do not exhibit pure capacitive behaviour also tending to show that coatings have some porosity. The polarization resistance potential of uncoated mild steel is in agreement with Ikhmal et al. (2019). The corrosion current obtained with uncoated samples is in agreement with Joycee et al. (2021).

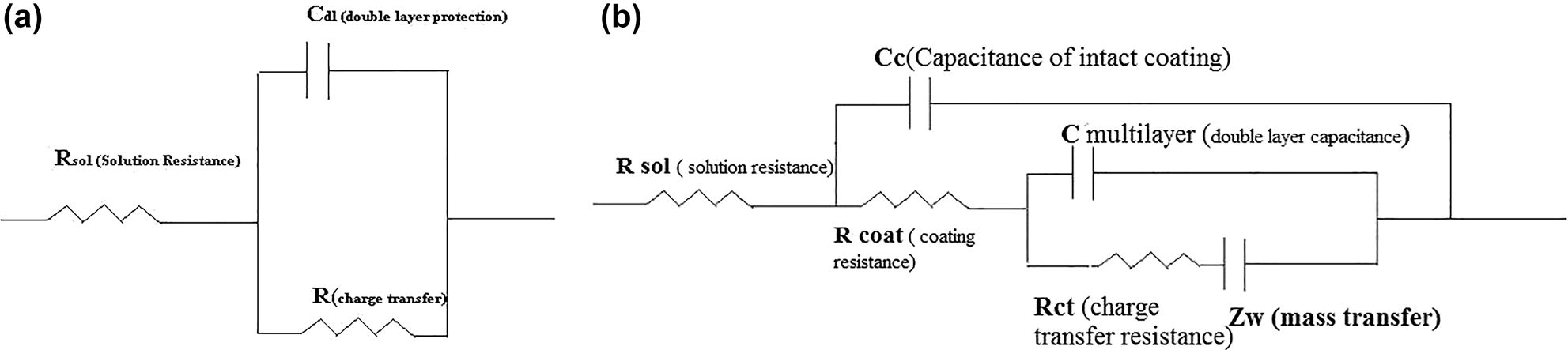

The EIS show that the corrosion attack on coatings 1 and 2 is due to the presence of pores and cracks which are reported readily in thermal spray coatings. The presence of pores in HVOF coatings may be due to uneven powder sizes, which result in small particles being melted completely while big size particles being incompletely or overheated resulting in insufficient fusion at the substrate interface leading to the formation of pores Jena et al. (2020). Randel’s equivalent circuit is shown in Figure 11a and b. where: βA = anodic slope; Rct = resistance offered by coating; βC = cathodic slope; Cdl = capacitance offered.

Equivalent circuit (EIS) for (a) uncoated mild steel in 3.5% NaCl solution and (b) Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 in 3.5% NaCl solution by delaminated coating.

6 Conclusions

In this study, (Zn–Ni–Cu) and (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2) coatings on mild steel substrate were adequately developed using HVOF spray technique likewise, the microstructural properties and corrosion properties were investigated. The results are concise as follows

Zn–Ni–Cu (85–10–5, % by weight, respectively) and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 (80–5–5–10, % by weight, respectively) were synthesized on mild steel substrate using HVOF.

Microstructural properties of the coated surface were analysed using SEM, and EDS which ascertained that coatings were fully developed with minimal porosity and no contamination.

Both Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel substrate showed excellent corrosion resistance as compared to uncoated mild steel specimen in salt spray test (5% NaCl). Uncoated mild steel developed corrosion within 24 h of the test. While both Zn–Ni–Cu coated mild steel and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel developed little corrosion at 50 H, showing clearly the corrosive resistance nature of the coatings.

An immersion cycle test in 3.5% NaCl solutions was performed for 28 days (672 h). In the immersion cycle, weight loss in uncoated mild steel was 40.1 mg. The weight loss for Zn–Ni–Cu coated mild steel was 3.15 mg and for Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel was 3.13 mg respectively. Hence weight percentage savings in Zn–Ni–Cu coated mild steel is 92.14% and for Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel is 92.19%.

Raman spectroscopy analysis followed the immersion cycle test. Specimen 1 (uncoated mild steel) developed all forms of rust (feroxyhyte, goethite, maghemite, lepidocrocite, akaganite and goethite) after 672 h. While specimen 2 (Zn–Ni–Cu on mild steel) showed the presence of ZnCl2, Zn (OH) 2 and α – FeOOH (Goethite) were the only form of rust present. Specimen 3 (Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 on mild steel) showed ZnCl2, Zn (OH)2, lepidocrocite (ϒ – FeOOH). Lepidocrocite is the only rust present after the immersion test. Hence proving coatings effectively prevented corrosion attack thereby saving substrate.

Tafel polarization and EIS analysis both showed higher corrosion resistance of coated surfaces compared to uncoated mild steel. Potential values of both Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coated mild steel are higher Ecorr = −0.68 m V, ICorr = −3.35 µA, and Ecorr = −0.58 m V, ICorr = −3.34 µA respectively, as compared to uncoated mild steel Ecorr = −0.85 m V. ICorr = −1.03 µA. Higher Ecorr values of coated samples indicate better corrosion resistance. Icorr values of both coated samples are significantly lesser than uncoated mild steel. Advocating that coated samples are better corrosion resistant in corrosive environments. The incorporation of TiB2 significantly improved the corrosion behaviour of the Zn–Ni–Cu coating suggesting a better barrier effect.

FEG–SEM and FESEM micrographs clearly show the coated surfaces are corrosion resistant compared to uncoated mild steel. The surface degradation in uncoated mild steel is high compared to coated mild steel.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr L. C. Pathak, CSIR National Metallurgical Laboratory, Jamshedpur for his kind help to carry out some of the work for this manuscript. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Director, CSIR-NML, for his kind permission to work at CSIR-NML, Jamshedpur.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Antunes, R.A., Costa, I., and Faria, D.L.A.D. (2003). Characterization of corrosion products formed on steels in the first months of atmospheric exposure. Mater. Res. 6: 403–408, https://doi.org/10.1590/s1516-14392003000300015.Search in Google Scholar

Bai, Y., Wang, Z.H., Li, X.B., Huang, G.S., Li, C.X., and Li, Y. (2017). Corrosion behavior of low pressure cold sprayed Zn–Ni composite coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 719: 194–202, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.05.134.Search in Google Scholar

Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R., Hamzah, E., Low, H.T., Kasiri-Asgarani, M., Farahany, S., Akbari, E., and Cho, M.H. (2017). Fabrication of biodegradable Zn–Al–Mg alloy: mechanical properties, corrosion behavior, cytotoxicity and antibacterial activities. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 73: 215–219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.138.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bhat, R.S., Manjunatha, K.B., Prasanna Shankara, R., Venkatakrishna, K., and Hegde, A.C. (2020). Electrochemical studies on the corrosion resistance of Zn–Ni–Co coating from acid chloride bath. Appl. Phys. A 126: 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-020-03958-9.Search in Google Scholar

Boudellioua, H., Hamlaoui, Y., Tifouti, L., and Pedraza, F. (2019). Effects of polyethylene glycol (PEG) on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel by cerium nitrate in chloride solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 473: 449–460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.12.164.Search in Google Scholar

Brykała, U., Diduszko, R., Jach, K., and Jagielski, J. (2015). Hot pressing of gadolinium zirconate pyrochlore. Ceram. Int. 41: 2015–2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.09.114.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, D., Yen, M., Lin, P., Groff, S., Lampo, R., McInerney, M., and Ryan, J. (2014). A corrosion sensor for monitoring the early-stage environmental corrosion of A36 carbon steel. Materials 7: 5746–5760, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7085746.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Conde, A., Arenas, M.A., and De Damborenea, J.J. (2011). Electrodeposition of Zn–Ni coatings as Cd replacement for corrosion protection of high strength steel. Corrosion Sci. 53: 1489–1497, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2011.01.021.Search in Google Scholar

Das, P., Paul, S., and Bandyopadhyay, P.P. (2018). HVOF sprayed diamond reinforced nano-structured bronze coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 746: 361–369, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.02.307.Search in Google Scholar

Deepak, J.R., Raja, V.B., and Kaliaraj, G.S. (2019). Mechanical and corrosion behavior of Cu, Cr, Ni and Zn electroplating on corten A588 steel for scope for betterment in ambient construction applications. Results Phys. 14: 102437, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102437.Search in Google Scholar

Espallargas, N., Berget, J., Guilemany, J.M., Benedetti, A.V., and Suegama, P.H. (2008). Cr3C2–NiCr and WC–Ni thermal spray coatings as alternatives to hard chromium for erosion–corrosion resistance. Surf. Coating. Technol. 202: 1405–1417, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2007.06.048.Search in Google Scholar

Fadl-Allah, S.A., Montaser, A.A., and El-Rab, S.M.G. (2016). Biocorrosion control of electroless Ni–Zn–P coating based on carbon steel by the pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 11: 5490–5506, https://doi.org/10.20964/2016.07.96.Search in Google Scholar

Fenker, M., Balzer, M., and Kappl, H. (2014). Corrosion protection with hard coatings on steel: past approaches and current research efforts. Surf. Coating. Technol. 257: 182–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.08.069.Search in Google Scholar

Hashmi, S. (2014). Comprehensive materials processing. Newnes.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, J., Chen, D., Wu, Y., Wang, M., Xia, C., and Wang, H. (2019a). Corrosion behavior of in-situ TiB2/7050Al composite in NaCl solution at different pH values. Mater. Res. Express 6: 056541, https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab055d.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Z.H., Zhou, Y.J., and Nguyen, T.T. (2019b). Study of nickel matrix composite coatings deposited from electroless plating bath loaded with TiB2, ZrB2 and TiC particles for improved wear and corrosion resistance. Surf. Coating. Technol. 364: 323–329, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.01.060.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, H., Li, N., Cheng, J., and Chen, L. (2009). Corrosion behavior of chromium-free dacromet coating in seawater. J. Alloys Compd. 472: 219–224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.04.029.Search in Google Scholar

Ikhmal, W.M.K.W.M., Maria, M.F.M., Rafizah, W.A.W., Norsani, W.N.W.M., and Sabri, M.G.M. (2019). Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in seawater through green approach using Leucaena leucocephala leaves extract. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 8: 628–643.10.17675/2305-6894-2019-8-3-12Search in Google Scholar

Jena, G., Anandkumar, B., Vanithakumari, S.C., George, R.P., Philip, J., and Amarendra, G. (2020). Graphene oxide–chitosan–silver composite coating on Cu–Ni alloy with enhanced anticorrosive and antibacterial properties suitable for marine applications. Prog. Org. Coating 139: 105444, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.105444.Search in Google Scholar

Joycee, S.C., Raja, A.S., Amalraj, A.S., and Rajendran, S. (2021). Inhibition of corrosion of mild steel pipeline carrying simulated oil well water by Allium sativum (garlic) extract. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 10: 943–960.10.17675/2305-6894-2021-10-3-8Search in Google Scholar

Krishna, L.R., Madhavi, Y., Babu, P.S., Rao, D.S., and Padmanabham, G. (2019). Strategies for corrosion protection of non-ferrous metals and alloys through surface engineering. Mater. Today Proc. 15: 145–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.05.037.Search in Google Scholar

Kumar, G.S., Kumar, P.S., Kavimani, V., Prakash, K.S., and Krishna, V.M. (2019). Effect of TiB2 on the corrosion resistance behaviour of in situ al composites. Int. J. Metalcast. 44, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40962-019-00330-3.Search in Google Scholar

Kwon, M., Jo, D.H., Cho, S.H., Kim, H.T., Park, J.T., and Park, J.M. (2016). Characterization of the influence of Ni content on the corrosion resistance of electrodeposited Zn–Ni alloy coatings. Surf. Coating. Technol. 288: 163–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.01.027.Search in Google Scholar

La, J., Song, M., Kim, H., Lee, S., and Jung, W. (2018). Effect of deposition temperature on microstructure, corrosion behavior and adhesion strength of Zn–Mg coatings on mild steel. J. Alloys Compd. 739: 1097–1103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.12.289.Search in Google Scholar

Leckraj, C. and Surnam, B.Y.R. (2017). Corrosion behaviour of mild steel in atmospheric exposure and immersion tests. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 6: 2.Search in Google Scholar

Li, B., Mei, T., Li, D., Du, S., and Zhang, W. (2019a). Structural and corrosion behavior of Ni–Cu and Ni–Cu/ZrO2 composite coating electrodeposited from sulphate-citrate bath at low Cu concentration with additives. J. Alloys Compd. 804: 192–201, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.06.381.Search in Google Scholar

Li, H., Yu, S., Hu, J., and Yin, X. (2019b). Modifier-free fabrication of durable superhydrophobic electrodeposited Cu–Zn coating on steel substrate with self-cleaning, anti-corrosion and anti-scaling properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 481: 872–882, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.03.123.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, F., Zhu, X., and Ji, S. (2020). Effects of Ni on the microstructure, hot tear and mechanical properties of Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys under as-cast condition. J. Alloys Compd. 821: 153458, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.153458.Search in Google Scholar

Matin, E., Attar, M.M., and Ramezanzadeh, B. (2015). Evaluation of the anticorrosion and adhesion properties of an epoxy/polyamide coating applied on the steel surface treated by an ambient temperature zinc phosphate coating containing Ni2+ cations. Corrosion 71: 4–13, https://doi.org/10.5006/1344.Search in Google Scholar

May, M. (2016). Corrosion behavior of mild steel immersed in different concentrations of NaCl solutions. J Sebha University-(Pure Appl Sci) 15: 1–12.Search in Google Scholar

Mazumder, M.A.J. (2020). Global impact of corrosion: occurrence, cost and mitigation. Glob. J. Eng. Sci. 5: 1–5.10.33552/GJES.2020.05.000618Search in Google Scholar

Meymian, M.R.Z., Ghaffarinejad, A., Fazli, R., and Mehr, A.K. (2020). Fabrication and characterization of bimetallic nickel-molybdenum nano-coatings for mild steel corrosion protection in 3.5% NaCl solution. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 593: 124617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.124617.Search in Google Scholar

Murmu, M., Saha, S.K., Murmu, N.C., and Banerjee, P. (2019). Amine cured double Schiff base epoxy as efficient anticorrosive coating materials for protection of mild steel in 3.5% NaCl medium. J. Mol. Liq. 278: 521–535, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.01.066.Search in Google Scholar

Ojo, S.I.F., Abimbola, A., and Idowu, P. (2019). Corrosion propagation challenges of mild steel in industrial operations and response to problem definition. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1378: 022006.10.1088/1742-6596/1378/2/022006Search in Google Scholar

Oulmas, C., Mameri, S., Boughrara, D., Kadri, A., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z., and Benfedda, B. (2019). Comparative study of Cu–Zn coatings electrodeposited from sulphate and chloride baths. Heliyon 5: 02058, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02058.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pola, A., Tocci, M., and Goodwin, F.E. (2020). Review of microstructures and properties of zinc alloys. Metals 10: 253, https://doi.org/10.3390/met10020253.Search in Google Scholar

Popoola, A.P.I., Olorunniwo, O.E., and Ige, O.O. (2014). Corrosion resistance through the application of anti-corrosion coatings. Developments in Corrosion Protection 13: 241–270.10.5772/57420Search in Google Scholar

Popczyk, M. and Budniok, A. (2010). Structure and corrosion resistance of Zn-Ni and Zn-Ni-W coatings. Mater. Sci. Forum 636: 1042–1046, https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/msf.636-637.1042.Search in Google Scholar

Sadananda, K., Yang, J.H., Iyyer, N., Phan, N., and Rahman, A. (2021). Sacrificial Zn–Ni coatings by electroplating and hydrogen embrittlement of high-strength steels. Corrosion Rev. 39: 487–517, https://doi.org/10.1515/corrrev-2021-0038.Search in Google Scholar

Shourgeshty, M., Aliofkhazraei, M., Karimzadeh, A., and Poursalehi, R. (2017). Corrosion and wear properties of Zn–Ni and Zn–Ni–Al2O3 multilayer electrodeposited coatings. Mater. Res. Express 4: 096406, https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/aa87d5.Search in Google Scholar

Stephen, J., Olakolegan, O., Adeyemi, G., and Adebayo, A. (2019). Corrosion behaviour of heat treated and nickel plated mild steel in citrus fruit: lime and lemon. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. Res. 8: 229–235.Search in Google Scholar

Souza, V.A.D. and Neville, A. (2005). Corrosion and synergy in a WCCoCr HVOF thermal spray coating—understanding their role in erosion–corrosion degradation. Wear 259: 171–180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2004.12.003.Search in Google Scholar

Surnam, B.Y.R., Chui, C.W., Xiao, H., and Liang, H. (2016). Investigating atmospheric corrosion behavior of carbon steel in coastal regions of Mauritius using Raman spectroscopy. Materia 21: 157–168, https://doi.org/10.1590/s1517-707620160001.0014.Search in Google Scholar

Tiwari, S.K., Tripathi, M., and Singh, R. (2012). Electrochemical behavior of zirconia based coatings on mild steel prepared by sol–gel method. Corrosion Sci. 63: 334–341, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2012.06.026.Search in Google Scholar

Ura-Bińczyk, E., Morończyk, B., Kuroda, S., Araki, H., Jaroszewicz, J., and Molak, R.M. (2019). Corrosion resistance of aluminum coatings deposited by warm spraying on AZ91E magnesium alloy. Corrosion 75: 668–679, https://doi.org/10.5006/3025.Search in Google Scholar

Uusitalo, M.A., Vuoristo, P.M.J., and Mäntylä, T.A. (2002). Elevated temperature erosion–corrosion of thermal sprayed coatings in chlorine containing environments. Wear 252: 586–594, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0043-1648(02)00014-5.Search in Google Scholar

Zaki, M.H.M., Mohd, Y., and Isa, N.N.C. (2017). Cu–Ni alloys coatings for corrosion protection on mild steel in 0.5 M NaCl solution. Sci. Lett. 11: 20–29.Search in Google Scholar

Zhai, X., Ren, Y., Wang, N., Guan, F., Agievich, M., Duan, J., and Hou, B. (2019). Microbial corrosion resistance and antibacterial property of electrodeposited Zn–Ni–chitosan coatings. Molecules 24: 1974, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24101974.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Zheng, Z., Guo, P., Li, J., Yang, T., Song, Z., Xu, C., and Zhou, M. (2020). Effect of cold rolling on microstructure and mechanical properties of a Cu–Zn–Sn–Ni–Co–Si alloy for interconnecting devices. J. Alloys Compd. 831: 154842, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154842.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editor’s Note

- A demonstration of resilience

- Reviews

- Scanning electrochemical microscopy methods (SECM) and ion-selective microelectrodes for corrosion studies

- Corrosion inhibitors for AA6061 and AA6061-SiC composite in aggressive media: a review

- Original Articles

- Oxidation–reduction reactions and hydrogenation of steels of different structures in chloride-acetate solutions in the presence of iron sulfides

- The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: effect of immersion time and anti-corrosion activity of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution

- Corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions with different pH adjusted by ammonia

- Comparison of protective coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilanes and possibilities of spectroelectrochemical approaches for their investigation

- Corrosion behaviour OF HVOF deposited Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editor’s Note

- A demonstration of resilience

- Reviews

- Scanning electrochemical microscopy methods (SECM) and ion-selective microelectrodes for corrosion studies

- Corrosion inhibitors for AA6061 and AA6061-SiC composite in aggressive media: a review

- Original Articles

- Oxidation–reduction reactions and hydrogenation of steels of different structures in chloride-acetate solutions in the presence of iron sulfides

- The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: effect of immersion time and anti-corrosion activity of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution

- Corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions with different pH adjusted by ammonia

- Comparison of protective coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilanes and possibilities of spectroelectrochemical approaches for their investigation

- Corrosion behaviour OF HVOF deposited Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel