Abstract

The effect of cysteine on the corrosion characteristics of Cu5Zn5Al1Sn alloy in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution has been studied by electrochemical and surface characterization techniques in various immersion times. The results of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) revealed that the degradation of Cu5Zn5Al1Sn alloy occurred in 3.5 wt% NaCl and was aggravated with increasing immersion time. The results of inhibition efficiency calculated from EIS data showed that cysteine can act as an effective anti-corrosion substance, which was also proved by the less eroded morphology of the alloy surface observed on scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Furthermore, the elemental analysis of alloy surfaces was investigated by Raman, electron dispersion spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), which confirmed the presence of S and N species. An adequate adsorption isotherm and inhibition mechanism was also suggested based on EIS results.

1 Introduction

Copper-based alloys are significant construction materials for indoor and outdoor applications owing to their attractive visual appearance, admirable thermal and physical properties along with their characteristic corrosion resistance (Barouni et al. 2010; Finšgar 2013a; Ghelichkhah et al. 2015), and have been used to cover ship exteriors since 18th century; while polymers, composites and steels dominate the applications in marine environment owing to their low price, availability, and manufacturing simplicity. However, they suffer a short service life and require frequent maintenance because of the high rate of degradation and low biofouling resistance in seawater (Zhang et al. 2014). Copper-based alloys are considered a feasible alternative to structural materials in marine environments due to their low maintenance cost, extended service life, improved reliability, and high recyclability (Drach et al. 2013). However, copper and its alloys are susceptible to corrosion in high chloride concentrations, e.g., hydroxyl and hydrochloric acid media (Chauhan et al. 2019). Thus, it is important to understand their corrosion and mechanical behavior under the service conditions in the atmospheric and marine environment to effectively design the structures of copper-based alloys (Drach et al. 2013). Several methods have been explored to protect metal and metal alloys, such as cathodic protection (Deshpande et al. 2022), steel coating (Kamburova et al. 2021), and the use of corrosion inhibitors (Goyal et al. 2018). The use of corrosion inhibitors is the most suitable method due to its low cost, ease of operation, and effectiveness (Goyal et al. 2018). Corrosion inhibitors are chemicals that avert or slow metal deterioration, which can be used in the corrosion atmosphere in a proper concentration range and form (Jin et al. 2013). Organic corrosion inhibitors form thin films on the surface of metals by either chemical covalent bonding or physical adsorption, which isolates the corrosion media from the metal and inhibits further metal corrosion. Farahati et al. (2019) studied the synthesis and potential functions of certain thiazoles as corrosion inhibitors for copper in 1 M HCl using electrochemical, surface characterization techniques and theoretical basis. They found that thiazoles can act as promising corrosion inhibitors for copper in 1 M HCl solution owing to the formation of the adsorption film by metal cation and thiol and/or amino functional groups of the inhibitor.

Amino acids, such as cysteine, glycine, glutamic acid, and glutathione, L-methionine containing amino (–NH2) group, were shown to be good corrosion inhibitors for several metals (Khaled 2010; Zhang et al. 2011). Barouni et al. studied the inhibition effect of some amino acids for copper in nitric acid solution. From the studied amino acids, Cys showed a better performance over other tested amino acids in protecting copper surface (Barouni et al. 2008). The high inhibition efficiency of cysteine is attained by the presence of mercato (–SH) group which is a main active site to form inhibition film with copper corrosion products (Barouni et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2011).

This study is an extension of our previous work on Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn alloy (Shinato et al. 2019) and focuses on exploring the effect of immersion time on the corrosion mechanism by using potentiodynamic polarization, electrochemical impedance, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), electron dispersive spectroscopy, Raman, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy techniques. Results from each technique were discussed and then their combinations. Lastly, the protective effect of cysteine (Cys) on the corrosion of golden alloy in 3.5 wt% NaCl was discussed for different immersion times.

2 Materials and methods

A commercial golden alloy with a composition of (89, 5, 5, and 1 wt% of Cu, Zn, Al, and Sn, respectively) was obtained from Hamburg, Germany (Aurubis Ltd.). The samples were enfolded by epoxy resin, leaving a surface area of 1 × 1 cm. Prior to the test, specimens were abraded with silicon carbide sandpaper with a grit size of 800, 1000, 1200, 1500 and 2000 consecutively. A diamond paste with a size of 2.5, 1.5, and 0.5 µm was used to polish the grounded specimen step by step. Ethanol (analytical grade) was used to clean the specimen followed by air drying. Sodium chloride (NaCl) with a concentration of 3.5 wt% was prepared with deionized water and analytical grade NaCl. Cysteine from Suzhou, China (KC90277-100 gm, Suzhou tianke Co. Ltd.,) was used as the inhibitor and a stock solution of 10−2 M was prepared by mixing a suitable amount of cysteine in distilled water. Series solutions of 10−3–10−5 M cysteine concentrations were prepared with the stock solution by a dilution method. A three-electrode system electrochemical cell was adopted in a glass with a volume of 400 ml. A silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) reference electrode and a platinum sheet counter electrode were used throughout the electrochemical experimentation. All potential measurements in the manuscript are stated with respect to Ag/AgCl. Before the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) test, the alloy sample was immersed in the blank and inhibitor-containing solution for 10, 20, and 30 days, respectively. The frequency range for EIS experimentation was 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz, and the open circuit potential (OCP) was set at 5 mV. Zsimpwin software was used to simulate EIS data with an equivalent circuit for quantitative analysis.

The polished and cleaned alloy samples were immersed immediately in the blank and inhibitor-containing solutions for 10, 20 and 30 days at room temperature. At the end of each exposure time, the samples were taken out, washed with deionized water, dried, and used for SEM, Raman, and XPS tests. Surface morphologies of the alloy samples were observed by SEM (FEI Quanta 250). Raman tests were performed to investigate the lateral distribution of functional groups on the alloy surface using a WITec alpha300 system set up with a laser source of 532 nm in wavelength and Nikon NA0.9 NGC objective lenses.

3 Results

3.1 Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

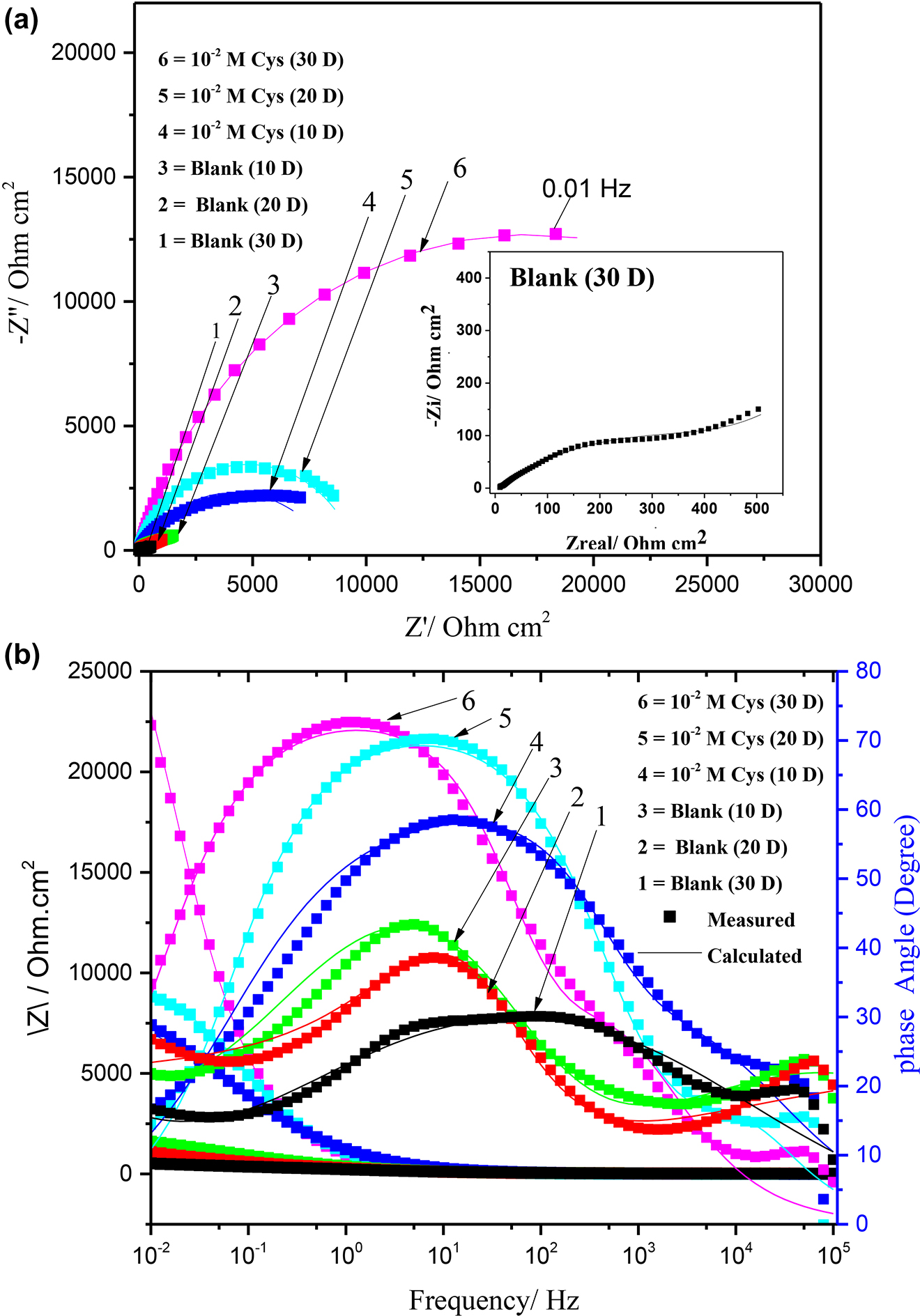

The Nyquist and Bode plots of the golden alloy without and with Cys (10−2 M) treatment of different immersion times in a corrosive media of 3.5 wt% NaCl solution is shown in Figure 1. The Nyquist for blank specimen encompasses a capacitive circle and straight line at an intermediate and low-frequency region, respectively (Figure 1a). A low-frequency straight line could be accredited to the incidence of Walberg impedance originating from the diffusion of ionized metal species from Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn surfaces to the solution (Quraishi 2013; Singh et al. 2019; Thanapackiam et al. 2016).

EIS plots for the Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn without and with cysteine treatment of different immersion times in 3.5 wt% NaCl: Nyquist (a) and Bode (b).

The low-frequency straight line section was not observed in the presence of Cys and the span of the capacitive loop increases with increasing treatment time, which may be ascribed to the protective action of Cys on the corrosion course (Dehghani et al. 2019; Ramezanzadeh et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2019). The imperfect semicircle in the Nyquist plot is associated with the heterogeneity of the alloy surface due to Cys molecules adsorption and surface impurities (Bahlakeh et al. 2019; Dehghani et al. 2019).

Simultaneously, an increase in diameter and shift to a lower frequency range in a phase maximum was observed for samples treated with Cys, which becomes more pronounced with longer immersion time due to the formation of a thicker inhibitor film (Figure 1b). These results confirm that prolonged treatment time with Cys improves its protection capability (Appa et al. 2013; Islam and Masatoshi 2019; Jiang et al. 2018). Compared with the sample with 10 days of treatment, the ones with a longer treatment time (30 days) show increased impedance modules at the low-frequency range of the bode plot (Figure 1b), indicating a better inhibition effect due to the enhanced surface coverage. Besides, it is found that the addition of Cys does not change the shape of the bode diagram, indicating that the corrosion was mainly determined by a charge-transfer process (Dehghani et al. 2019).

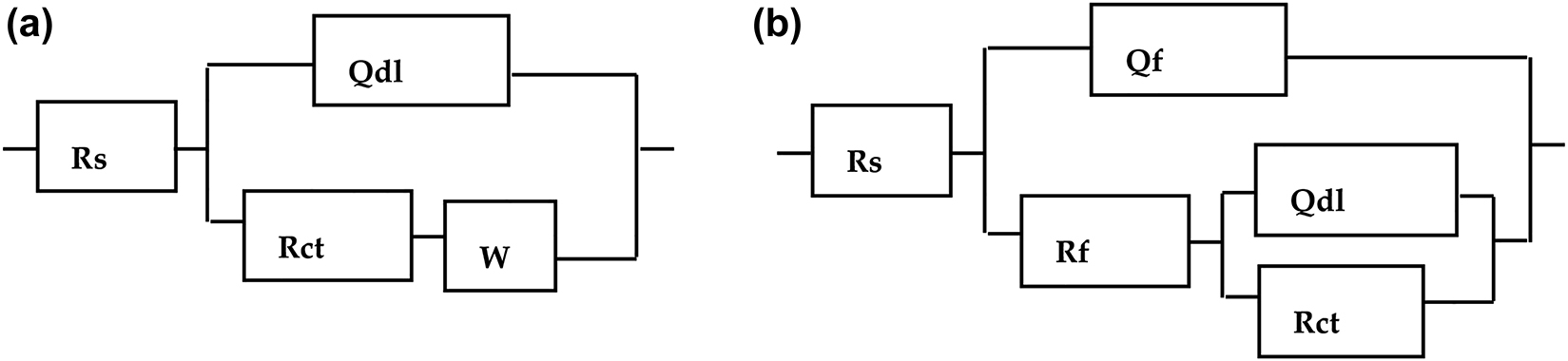

ZSimpWin 3.5 was used to fit EIS experimental results and a simulated circuit shown in Figure 2 was obtained for the blank and inhibited surfaces, respectively, which was previously used to investigate copper alloy corrosion in chloride environment (Dang et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2017). This circuit model was also applied to (Shinato et al. 2019) studying the corrosion behavior of golden alloys, indicating a consistent protection mechanism of Cys on the specified alloy with prolonged treatment time.

Electrical equivalence circuit for the golden alloy without (a) and with Cys inhibitor (b) in 3.5 wt% NaCl.

The resulting values of equivalent circuit parameters including solution resistance (Rs), charge transfer resistance (Rct), double layer capacitance (Qdl), Warburg constant (W) as well as inhibition efficiency derived from Equation (1) are listed in Table 1. The Warburg constant in the blank solution is introduced to explain the diffusion of dissolved oxygen and corrosion products to the alloy surface and bulk solution, respectively, which is consistent with the presence of a straight line at lower frequency area of the Nyquist plot (Quraishi 2013; Singh et al. 2019; Thanapackiam et al. 2016). The Warburg impedance is absent for samples treated with Cys inhibitor owing to the coverage of the alloy surface with inhibitor molecules (Xu et al. 2018). The Q value in the presence of the Cys with different treatment times is lower than those of the blank solution. The decrease in Q can be attributed to a decrease in the local dielectric constant or the increment of the double layer thickness. The enhanced Rct with the increased immersion time and improvement in the inhibition efficiency can be attributed to the wider surface coverage of the alloy surface by a layer of inhibitor film (Kumar et al. 2019).

where: µ, Rp and Rp (inh) are inhibition efficiency, polarization resistance of blank and polarization resistance of inhibited surfaces, respectively.

Impedance parameters for the golden alloy at different immersion times (10, 20, and 30 days) in blank 3.5 wt% NaCl solution and with cysteine inhibitor.

| Cys concentration (M) | Immersion time (day) | R s (Ωcm2) | Q f /mF cm−2 | R f (Ω cm2) | Q ct/mF cm−2 | R ct (kΩ cm2) | W/Ω−1 cm−2s1/2 | R p (kΩ cm2) | µ% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 10 | 7.119 | 1.43 | 0.5507 | 0.0260 | – | |||

| 20 | 25.19 | 0.84 | 0.612 | 0.0055 | – | ||||

| 30 | 3.004 | 0.414 | 1.742 | 0.0034 | – | ||||

| 10−2 | 10 | 5.07 | 0.019 | 282.20 | 0.236 | 8.416 | 79.30 | ||

| 20 | 4.71 | 0.018 | 3.99 | 0.188 | 9.517 | 93.56 | |||

| 30 | 10.37 | 1.250 | 34.84 | 0.110 | 34.40 | 98.39 |

The inhibition efficiency was calculated using Equation (1) to further describe the effect of immersion time on the inhibition role of Cys on a quantitative basis (Hosseini et al. 2017). Maximum inhibition efficiency of 98.39% with a longer immersion time (30 days) is obtained which indicates that the inhibition efficiency increases with the increasing immersion time.

3.2 SEM/EDS results

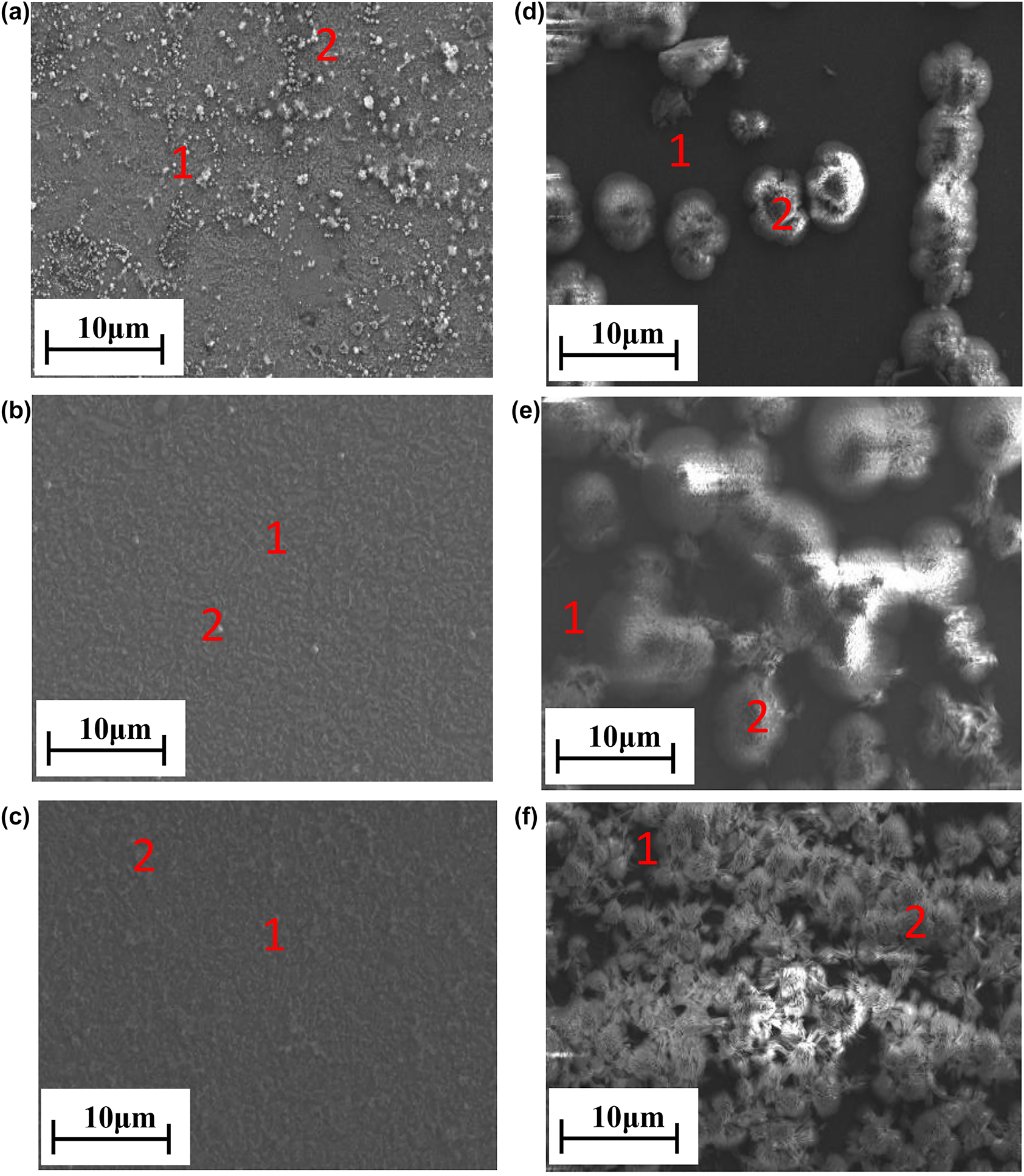

After examination of electrochemical characteristics of golden alloy specimen in 3.5 wt% NaCl through electrochemical techniques, surface characterizations were performed to offer further insights into the underlying mechanism. A Cys concentration with the highest efficiency was chosen. Besides, the effect of immersion time of up to 30 days was examined. The SEM images show distinct morphologies for samples with different treatment time (Figure 3). The corresponding EDS data confirms the elements present on the alloy’s surface (Table 2). Spherical adsorbates were observed for samples with 10 days of treatment (Figure 3a), which can be attributed to Cl− adsorption (Pareek et al. 2019; Vinothkumar and Mathur 2018), whereas this was replaced by Cys molecules in the presence of cysteine (Figure 3d). On the other hand, the spherical adsorbates (Cl−) were almost removed and the alloy surface was covered by metal oxide films, which was confirmed by the increase in oxygen content from EDS results (Figure 3b, Table 2).

SEM images of golden alloy in the blank (a–c) and 10−2 M cysteine inhibited (d–f) solution for 10, 20, and 30 days of immersion, respectively.

EDS atomic composition table corresponding with the points marked in Figure 2.

| Element | Composition (atomic %) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank (B) | 10−2M cysteine (C 2) | |||||||||||

| 10 days | 20 days | 30 days | 10 days | 20 days | 30 days | |||||||

| Point 1 | Point 2 | Point 1 | Point 2 | Point 1 | Point 2 | Point 1 | Point 2 | Point 1 | Point 2 | Point 1 | Point 2 | |

| C K | 9.08 | 18.58 | 4.32 | 31.81 | 27.74 | 24.66 | 16.48 | 49.2 | 13.83 | 48.69 | 46.96 | 44.49 |

| N K | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 18.71 | --- | 15.21 | 10.7 | 7.04 |

| O K | 57.69 | 62.49 | 42.99 | 14.01 | 59.47 | 36.17 | 55.22 | 16.42 | 69.47 | 15.58 | 11.38 | 11.28 |

| Al | 6.8 | 5.5 | 0.93 | 5.55 | 5.8 | 7.93 | 12.5 | 0.37 | 18.32 | -- | 4.44 | 0.03 |

| S K | −0.13 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 1.11 | 7.64 | 2.55 | 11.9 | 12.17 | 27.21 |

| Cl K | 1.01 | 1.7 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.62 | -- | 2.23 | 0.18 | 4.44 | 0.2 | 5.51 | -- |

| Cu L | 38.83 | 19.37 | 11.33 | 45.09 | 24.05 | 54.45 | 25.54 | 7.31 | 20.21 | 8.33 | 6.75 | 9.8 |

| Zn L | 6.71 | 5.75 | 20.36 | 6.71 | 9.03 | 8.57 | 1.88 | 0.14 | 1.96 | 0.11 | 0.34 | 0.2 |

| Sn L | 1.62 | 0.35 | 23.21 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.03 | 1.01 | −0.03 | 1.75 | -- |

In the presence of cysteine, the oxide films are replaced by metal/cysteine film as a result of the shielding effect of Cys. The coverage of Cys molecules increases with the increasing immersion time. Elemental analysis results of the EDS experiment (Table 2) show that S and N were found in the presence of cysteine and their amount on the alloy surface increases with immersion time. This confirms that cysteine-containing thin film is formed on the golden alloy surface, protecting it against deterioration mainly through the amino and mercaptan active sites (Loto et al. 2019; Salcı and Ramazan 2018).

3.3 Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)

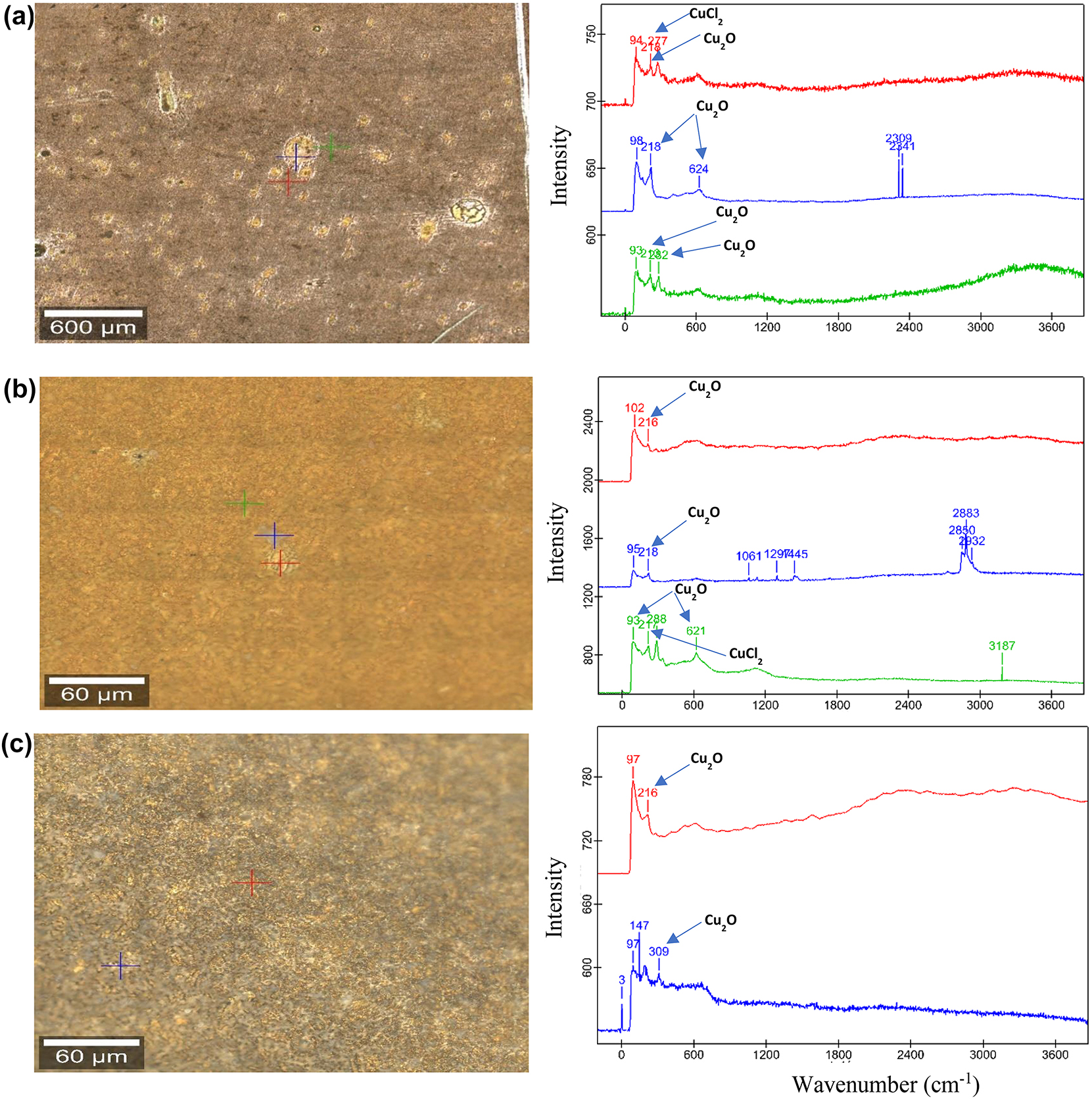

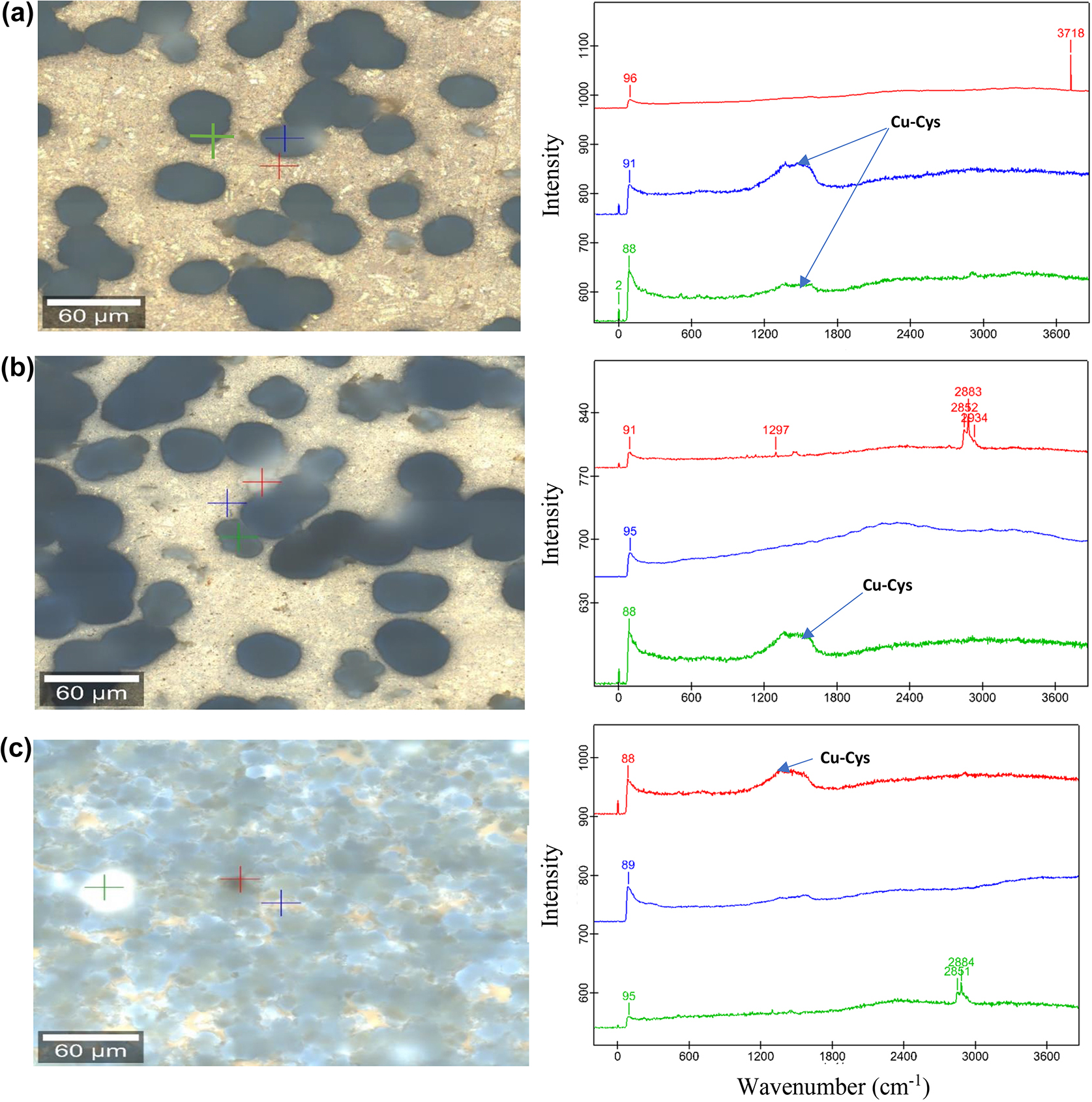

The presence and property of chemisorption of inhibitors into the alloy surface on sample surfaces after 10, 20, and 30 days of exposure to the 3.5 wt% NaCl solution without and with 10−2 M Cys was investigated by Raman.

The peaks at lower frequency regions were observed to account for the presence of metal oxide and chloride ion in the blank solution. Peaks at 218 (217, 216), 288 (287), 309, 621 (624) cm−1 in the blank solution can be assigned to the Cu2O, CuCl2, ZnO and CuO, respectively (Bernardi et al. 2009; Chen and Erbe 2018; Markin et al. 2018; Perales-Rondon et al. 2019) (Figure 4). On the other hand, the peaks in the lower frequency region were absent in the presence of Cys inhibitor. Instead, a broad band in the range of 1300–1600 cm−1 at the higher frequency region was observed (Figure 5), which can be assigned to the Cu–Cys stretching vibrations through amino and mercaptan groups (Chen and Erbe 2018; Khatibi et al. 2019). Better surface coverage of Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn alloys by the inhibitor film was observed in samples with 30 days of immersion, indicating that a longer treatment time with Cys provides a better inhibition effect.

Raman images of golden alloy in 3.5 wt% NaCl (a–c) 10, 20, and 30 days of immersion, respectively with their respective Raman spectral curves.

Raman images of golden alloy in 3.5 wt% NaCl with 10−2 M cysteine (a–c), 10, 20, and 30 immersion days, respectively with their corresponding Raman spectral curves.

3.4 XPS results

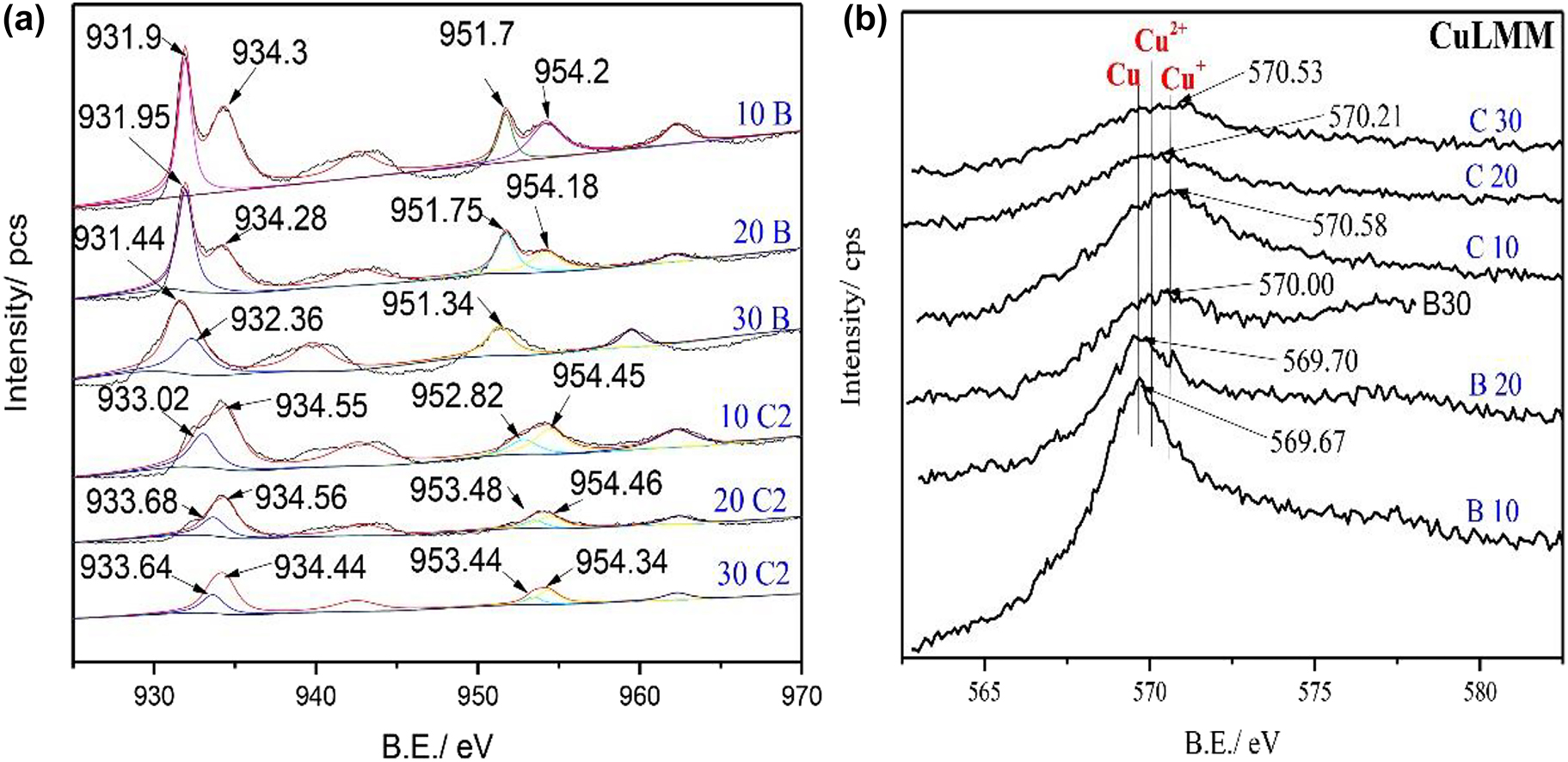

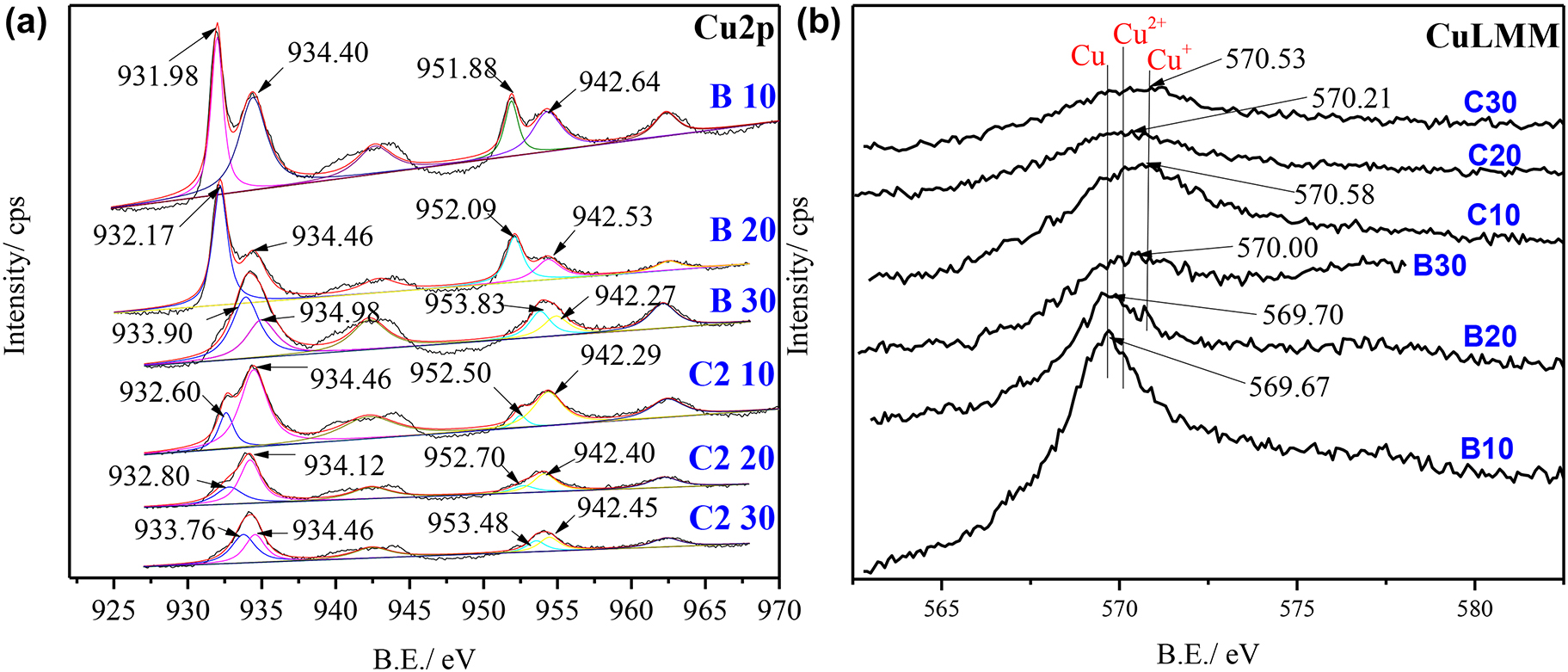

The XPS spectra for each constituent element were obtained for samples with relatively long immersion times in blank 3.5 wt% NaCl and in cysteine-containing solutions. Figure 6 shows the Cu2p and CuLMM spectra of golden alloys in a specified solution with different immersion times. Auger CuLMM is important to differentiate the peaks of Cu(0) and Cu(I) since their respective peaks in Cu2p spectra are quite similar. The CuLMM peak of Cu(I) has 2 eV upper binding energy (B.E.) value compared to that of Cu(0), suggesting that the CuLMM spectrum is essential to reveal the presence of different species of copper. Deconvoluted peaks of Cu2p 3/2 and Cu2p ½ were observed at their respective binding energies (Figure 6a).

XPS Cu2p (a) and Auger (b) spectra of golden alloy without and in the presence of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl at different immersion times (10, 20, and 30 days); B, blank; C2, 10−2 M cysteine.

The previous results of SEM/EDS and Raman results revealed that different reactions take place on the alloy surface in the presence and absence of Cys. As a result, the interpretation of the respective peaks is not the same even though there are similar peaks in all cases. The corrosion products in the blank solution are in a form of oxides in reaction with oxygen dissolved in the solution, while cysteine molecules have the chance to participate in the surface reactions of the treated samples. In the blank solution, the deconvoluted Cu2p peaks at 933.76, 932.80, and 932.60 eV for treatment times of 10, 20 and 30 days are allocated to Cu/Cu+ and Cu2+, respectively (Cano et al. 2019; Caprioli et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2019a,b; Shinato et al. 2020). A decrease in the binding energy with increasing immersion time indicates the presence of more Cu ion species, which may originate from the formation of more copper oxides on the alloy surface (Aissaoui et al. 2020; Finšgar and Kek Merl 2014). Besides the Cu2p results, the CuLMM spectrum found in the blank solution displays peaks at 569.67, 569.70, and 570.00 eV for samples of 10, 20, and 30 immersion days, respectively (Figure 6b). The two peaks at 569.67 and 569.70 eV can be assigned to metallic copper and the peak at 570.00 eV to cupric species. The appearance of other forms of Cu can be revealed by band broadening in addition to the specific assignments (Kazansky et al. 2014). Collectively, the XPS and Auger results of the blank solution confirmed the existence of Cu, Cu+, and Cu2+ molecules on the metal/solution interface, suggesting the formation of copper oxides on alloy surfaces (Han et al. 2020; Singh et al. 2020).

In the solution containing 10−2 M cysteine, the Cu2p peaks (933.90, 932.57, 932.98 eV) shift a little bit to the lower binding energy and the auger peaks shift to higher binding energies (570.57, 570.21, and 570.53 eV). This may be attributed to the presence of more ionic species (Cu+ and Cu2+) rather than metallic coppers. On the other hand, the peak intensity of peaks assigned to Cu2+ on Cu2p spectra becomes broader and the auger peak of samples with the immersion time of 30 days is closer to that of Cu2+ ion (Yang et al. 2019). Overall, the results of Cu2p and CuLMM spectra show the formation of Cu–Cysteine films consisting of Cu+ in the beginning and Cu2+ after a long treatment time with Cys, which is due to the oxidation of Cu+ ions through the immersion process (Krätschmer et al. 2002).

Two deconvoluted peaks were observed in the high resolution XPS Zn2p spectra (Figure 7a) obtained on the surface exposed to the blank 3.5 wt% solutions with different immersion times, which may be allocated to Zn2p 3/2 and Zn2p ½ (Koitaya et al. 2017; Morozov et al. 2015; Wagner et al. 1979; Wu et al. 2017). The Zn2p 3/2 peaks at 1021.43, 1021.62 and 1021.36 eV for immersion times of 10, 20 and 30 days, respectively, may be assigned to Zn2+, which could be associated with the corrosion products (Chen and Erbe 2018). The peak intensity of Zn2p spectra increases with the increasing immersion time, indicating the increase in dezincification rate with a higher corrosion rate (Ghiara et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019a,b). The absence of Zn2p peaks in samples with Cys treatment confirms that the alloy surface is completely sheltered by cysteine particles and Zn does not participate in film formation. The surface may be covered by a film formed by other alloying elements in golden alloys, possibly a copper–cysteine composite.

XPS spectra of golden alloy in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution and with 10−2 M cysteine at different immersion times (10, 20, and 30 days); Zn2p (a) and Sn3d (b).

The Sn3d shows three deconvoluted peaks for golden alloys in the 3.5 wt% solutions with different immersion times, whereas no peaks were observed for the cysteine-inhibited surface (Figure 7b). The two peaks at lower binding energies correspond to Sn5/2 and Sn3/2 (Lewera et al. 2011; Wagner et al. 1979; Zatsepin et al. 2016). The Sn5/2 peaks at 486.29, 486.21, and 486.12 eV for samples in the blank solution can be assigned to Sn2+/Sn4+ (Casella and Contursi 2006; Shinato et al. 2020; Virnovskaia et al. 2007). On the top of the main Sn3d peaks, satellite peaks were observed centered at 498.69, 498.74, and 498.67 eV for samples with immersion times of 10, 20, and 30 days, respectively. The satellite peak indicates the existence of more tin ions on the golden alloy surface (Serrano-Ruiz et al. 2006).

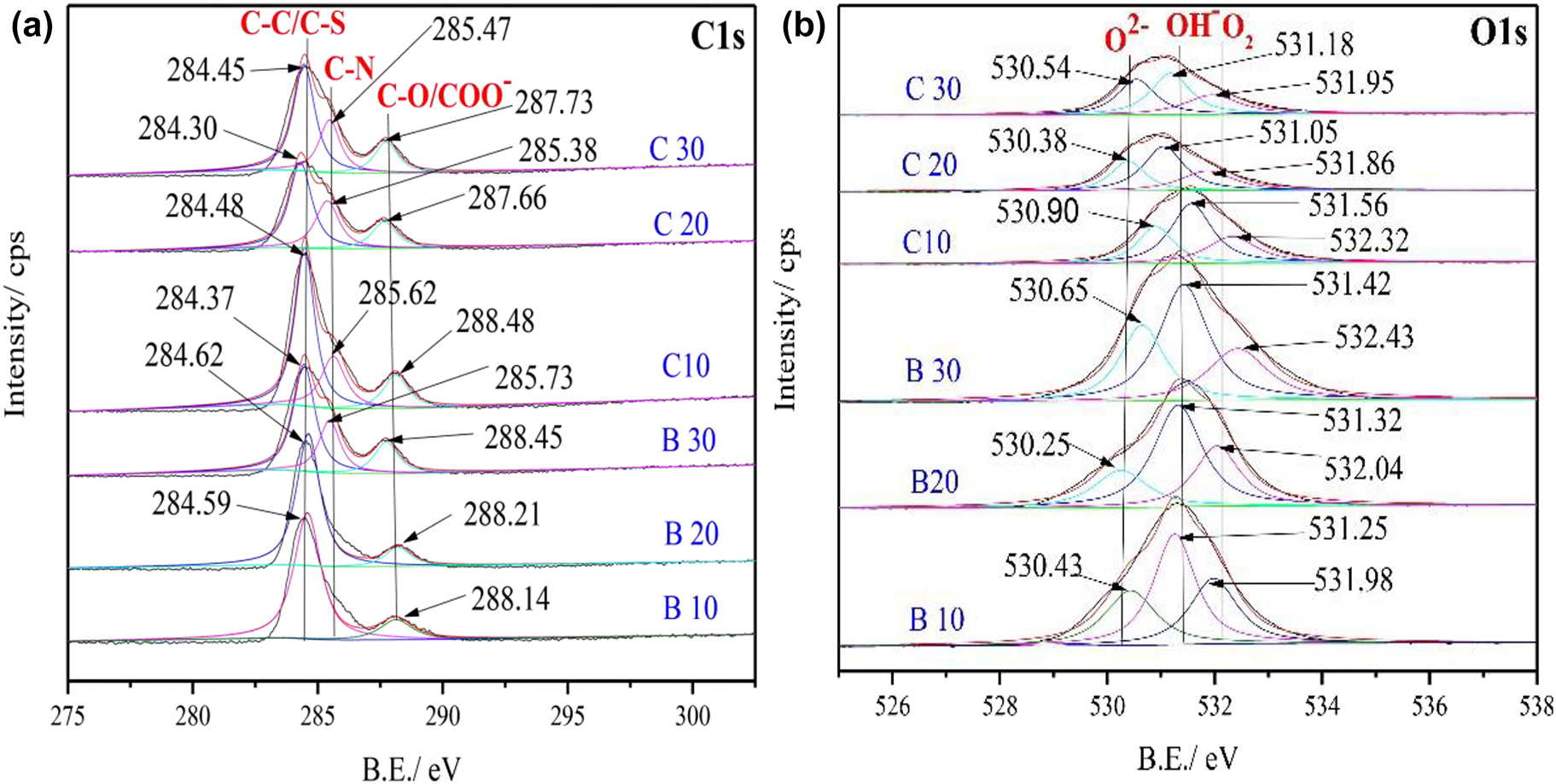

The deconvoluted C1s spectrum shown in Figure 8a for the golden alloy in the blank 3.5 wt% solution shows two peaks for short immersion periods (i.e., 10 and 20 days) and three peaks for longer immersion times (? days). The peaks correspond to different species of the C atom on the alloy surface. Spectral peaks at 284.59, 284.62, and 284.37 eV in a blank solution for immersion times of 10, 20, and 30 days can be allocated to the non-oxidized carbon-containing (C–C) configuration (Landoulsi et al. 2016; Lesiak et al. 2018; Sinha and Mukherjee 2018). Besides, the feature at B.E. value of 285.73 eV which only presents in samples with 30 days of immersion can be allotted to carbon–oxygen bond, i.e., a C–O group hydroxyl or ether, which may originate from the oxides formed by the dissolved oxygen in the solution (Sinha and Mukherjee 2018). On the other hand, Cls peaks at 288.14, 288.21, and 288.45 eV are associated with adventitious carbons mostly found on the metal surfaces and formed by adsorbed oxidized carbon from the atmosphere (Finšgar 2013b,c). The samples containing 10−2 M cysteine show three distinct peaks in the high-resolution C1s spectrum. Peaks at 284.48, 284.30, and 284.45 eV (10, 20, and 30 days of immersion) can be assigned to C–SH groups of the cysteine moiety (Wagner et al. 1979). Whereas, the three deconvoluted peaks at 285.62, 285.38, and 285.47 eV can be allotted to C–N (Landoulsi et al. 2016). In addition, the peaks at relatively higher B.E. of 288.48, 287.66, and 287.73 eV correspond to COO–, attributing to the formation of thin films between the alloy surface and the cysteine inhibitor through oxygen adsorption sites (Mel et al. 2011; Pramanik et al. 2019; Torrisi et al. 2020).

XPS C1s (a), O1s (b) of golden alloy surface in blank and cysteine containing 3.5 wt% NaCl solution at different immersion times (10, 20, and 30 days), respectively.

There are three peaks in a deconvoluted O1s spectrum of Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn alloys in the presence and absence of Cys with different immersion times in the 3.5 wt% NaCl solution (Figure 8b). In the blank solution, most of the oxygen compositions derive from the oxides by formation with the alloying metals (Qiang et al. 2018; Zatsepin et al. 2017). On the other hand, oxygen atoms on the protected surface can also be associated with the thin film formed by the given inhibitor since cysteine has an oxygen functional group. In the blank solution peaks located at 530.43 and 530.25 eV can be assigned to O2−, which is correlated to oxygen atoms bonded to the alloys, mainly copper-based oxides, since the main corrosion products on the outmost surface of the alloy is copper-based (Chang et al. 2018b; Qiang et al. 2018; Rao and Reddy 2017). The second peaks observed at 531.25, 531.32, and 531.42 eV are assigned to OH−, which can be associated with the formation of copper, tin, aluminum, and zinc hydroxides (Chang et al. 2018a).

The third peaks at 531.98, 532.04, and 532.43 eV can be allocated to atmospheric oxygen, which resulted from carbon contamination (Huang et al. 2017; Shinato et al. 2019). The three peaks around 530+, 531+, and 532+ in the presence of 10−2 M cysteine can be associated with C–O from carboxyl, C=O or –CON (Ravichandran et al. 2004). The inhibited alloy surface displays no peak related to the metal oxides which can be an indication of full coverage of the alloy by the inhibitor film (Shinato et al. 2020; Stańczyk et al. 1995).

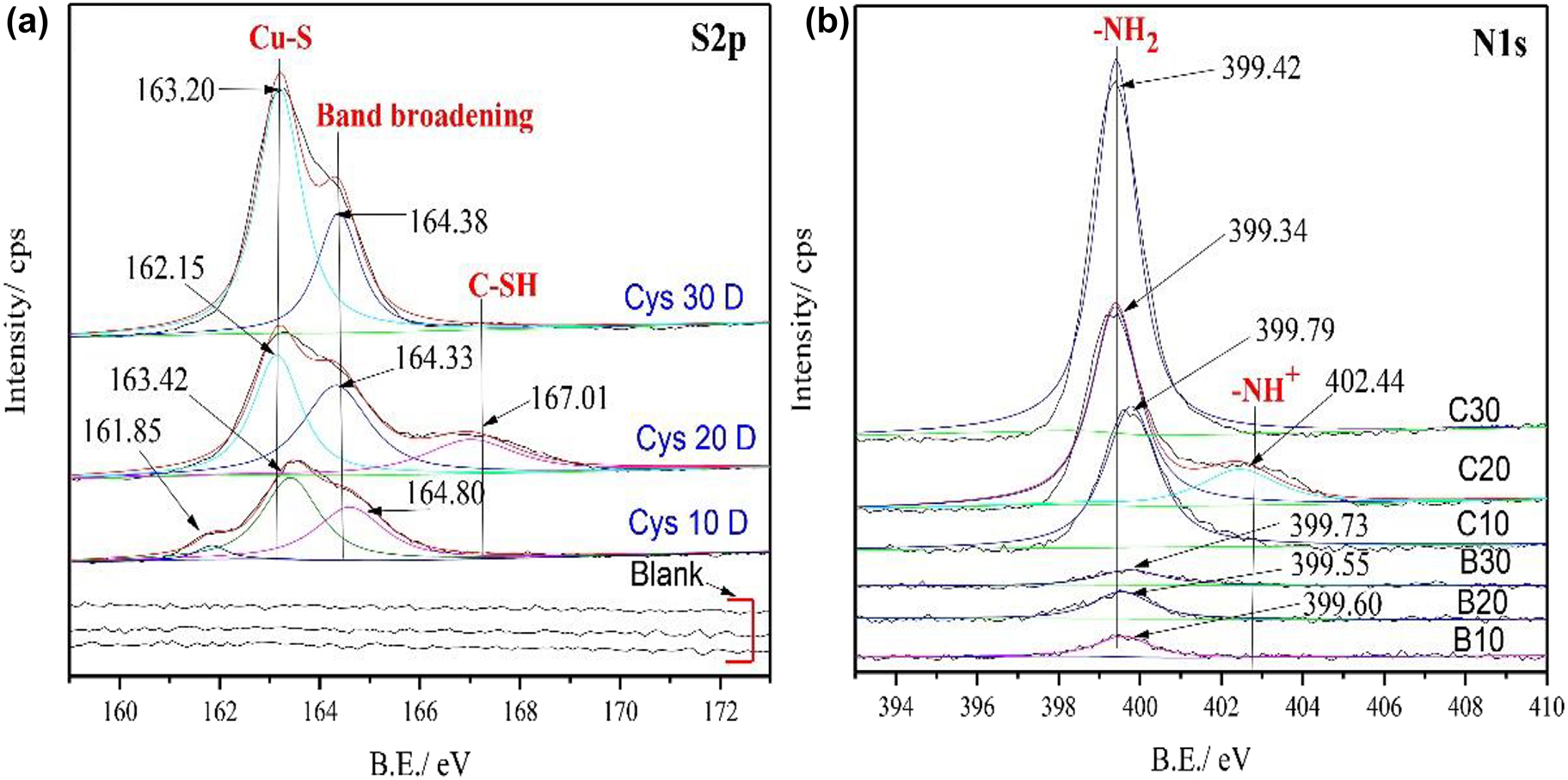

Figure 9a shows the deconvoluted S2p spectrum of Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn alloy in the 3.5 wt% NaCl with and without cysteine. No peak was observed in the S2p spectrum of the alloy in the blank 3.5 wt% NaCl due to the absence of sulfur-related molecules. Different features were observed in the presence of cysteine with different immersion times. After 10 days of immersion, three peaks (161.85, 163.42, and 164.60 eV) were observed, among which two (163.45 and 164.60 eV) correspond to one form of S with different conformations (S2p ½ and S 2p 3/2, respectively) and can be assigned to the metal–sulfur interaction (Wagner et al. 1979). The peak with a lower binding energy of 161.85 eV is due to band broadening (Milošev et al. 2015).

XPS S2p (a), N1s (b) spectra of golden alloy surface in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution without and with cysteine inhibitors in different immersion times (10, 20, and 30 days).

The alloy after immersion for 20 days in 10−2 M Cys also shows three peaks (162.12, 164.33, and 167.01 eV). The peaks with lower binding energies (162.12 and 164.33 eV) are assigned to the metal–sulfur interaction like samples after 10 days of immersion. The peak at 167.01 eV is associated with the –SH group of the cysteine molecule due to the formation of the adsorption film through the –NH2 functional group (Wagner et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2003). On the other hand, the sample with 30 days of immersion only shows two high-intensity peaks at 163.20 and 164.38 eV, which are assigned to the metal–sulfur interaction. The high peak intensity for samples after long term immersion indicates the presence of more cysteine molecules on the surface as well as a dense metal/inhibitor film (Ismail 2007).

The N1s spectra obtained on the surfaces of the blank and inhibited alloys show one peak except for samples with a treatment time of 20 days (two peaks, Figure 9b). This exception is due to the formation of thin films based on –NH functional groups as shown on the S2p XPS analysis since peaks above 400 eV in the N1s spectra are the typical characteristics of –NH group (Al-Wahaibi et al. 2019). The peaks at 399.60, 399.55, and 399.73 eV in the blank solution can be assigned to atmospheric nitrogen during sample preparation (Idczak et al. 2014). On the other hand, the peaks obtained in the inhibited alloy surfaces (399.79, 399.34, and 399.42 eV) may be associated with secondary nitrogen (–NH) credited to the existence of the organic moiety originating from cysteine inhibitors (Ravichandran et al. 2004). These results suggest that the adsorption sites of cysteine molecules on the alloy surface rely on both S and N groups. An increase in the peak intensity with increasing immersion time for the cysteine treated alloys further confirms the adsorption of an extra quantity of cysteine molecules on the golden alloy surfaces.

4 Discussion

Multiple analytical techniques were used to understand the effect of the immersion time of Cys on the corrosion of Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn alloys in the 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. The anti-corrosion effect of cysteine was examined during the immersion process. The combined results of EIS, Raman, SEM/EDS, and XPS tests show that the corrosion rate of golden alloy increases with increasing immersion time in the 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. It was found that the presence of cysteine reversed the situation by decreasing the corrosion rate with increasing immersion time.

EIS was used as an appropriate tool to determine the inhibition efficiency of cysteine with different immersion times (Touir et al. 2009). In the blank solution, EIS tests were carried out on samples with different immersion times (10, 20 and 30 days), showing one time constant in bode plots and a linear line at the low-frequency region in Nyquist plots. These results indicate that the three samples underwent similar reactions though experiencing different reaction rates (Hassan et al. 2007). The corrosion rate of golden alloys in the blank 3.5 wt% NaCl solution increases with increasing immersion time as illustrated by a decrease in the diameter of the Nyquist semi-circle with smaller Rp from the fitting results (Appa et al. 2013). On the other hand, the straight line at the low-frequency region of the Nyquist plot is absent in the presence of cysteine for all immersion times which results from the lowering of oxygen diffusion from the solution to the alloy surface with a decrease in the corrosion rate (Singh et al. 2020; Thanapackiam et al. 2016). The Rp value and the diameter of a semi-circle in the Nyquist plot also increase for inhibited surfaces due to the anti-corrosion effect of cysteine. The value of Rp for alloys immersed in cysteine for the 30 days is much higher than others, which can be accredited to the development of a compact shielding film composed of the constituent metals of alloys and cysteine molecules (Islam and Masatoshi 2019; Jiang et al. 2018).

Raman results showed that the alloy surfaces were immersed in the blank 3.5 wt% NaCl with different times exhibited peaks corresponding to metal oxides formed by the constituent metals and dissolved oxygen (Bernardi et al. 2009; Markin et al. 2018). These peaks disappeared in the presence of cysteine and were replaced by other broad peaks assigned to Cu–cysteine interactions (Chen and Erbe 2018; Khatibi et al. 2019). The result illustrates that the surface reaction is dominated by oxygen diffusion from the solution to the alloy surface in the blank solution and this diffusion reaction is retarded by the metal/inhibitor film in the presence of cysteine. In this regard, we infer that copper is the dominant alloying metal constituent that participates in the film formation. The absence of zinc and limited tin species in the XPS spectra from the inhibited samples supports this argument, which can be explained by “like dissolves like” Lewis acid/base theory. Soft acids preferentially interact with soft bases and vice versa (Talluri and Thomas 2017). The sulfur moiety of cysteine, as a soft Lewis base, is a predominantly active adsorptive site for film formations. Sulfur preferentially interacts with soft Lewis acid, resulting in the formation of a stable compact film on the alloy surface in cysteine containing environment with copper species in the cuprous form (Kong et al. 2017; Talluri and Thomas 2017).

Generally, immersion time has a strong effect on the corrosion of golden alloy and the presence of an inhibitor can protect it against corrosion for a prolonged period of immersion. Results obtained from all analytical techniques used in this study agree with each other and can help to understand the anti-corrosion mechanism of Cys on golden alloys.

5 Conclusions

In this study, the corrosion behavior of golden alloys was observed in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution in the absence and presence of cysteine. 3.5 wt% NaCl is corrosive for the alloy and the corrosion rate increases with the increasing immersion time. EIS experiments revealed that cysteine can be used as a corrosion inhibitor with a maximum corrosion efficiency of 98.95% after 30 days of immersion in cysteine (10−2 M). SEM/EDS results showed that S and N species can be detected on the alloy surface treated with cysteine and their contents increased with increasing immersion time, suggesting that Cys treatment with longer time can offer better protection. Raman and XPS tests were carried out to examine the surface compositions of Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn alloys in the corrosive media. The results revealed that copper was the main constituent that participated in the film formation. The film formed by copper and inhibitor molecules protects other constituent metals from ionization, thus resulting in less corrosion. Generally, cysteine is a good corrosion inhibitor for Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn alloys and its inhibitive effect is based on the formation of a protective thin film by reactions between the copper surface and the active adsorptive sites of cysteine molecules. S is the main adsorptive site for film formations with a small contribution from N and O active adsorption sites.

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 51802141

Award Identifier / Grant number: JCYJ20180302174243612

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This research was financially supported by the funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 51802141) and the Science and Technology Innovation Committee of Shenzhen Municipality (no. JCYJ20180302174243612).

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this article. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

Aissaoui, N., Liascukiene, I., Genet, M.J., Dupont-Gillain, C., El Kirat, K., Richard, C., and Landoulsi, J. (2020). Unravelling surface changes on Cu–Ni alloy upon immersion in aqueous media simulating catalytic activity of aerobic biofilms. Appl. Surf. Sci. 503: 144081, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144081.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Wahaibi, L.H., Sert, Y., Ucun, F., Al-Shaalan, N.H., Alsfouk, A.A., El-Emam, A., and Karakaya, M. (2019). Theoretical and experimental spectroscopic studies, XPS analysis, dimer interaction energies and molecular docking study of 5-(adamantan-1-Yl)-N- methyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-amine. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 135: 109091, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2019.109091.Suche in Google Scholar

Appa, V., Rao, B., and Chaitanya, K.K. (2013). Corrosion inhibition of Cu–Ni (90/10) alloy in seawater. Corrosion 2013: 1–22.10.1155/2013/703929Suche in Google Scholar

Bahlakeh, G., Ali, D., Bahram, R., and Mohammad, R. (2019). Highly effective mild steel corrosion inhibition in 1 M HCl solution by novel green aqueous mustard seed extract: experimental, electronic-scale DFT and atomic-scale MC/MD explorations. J. Mol. Liq. 293: 111559, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111559.Suche in Google Scholar

Barouni, K., Bazzi, L., Salghi, R., Mihit, M., Hammouti, B., Albourine, A., and Issami, E.S. (2008). Some amino acids as corrosion inhibitors for copper in nitric acid solution. Mater. Lett. 62: 3325–3327, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2008.02.068.Suche in Google Scholar

Barouni, K., Mihit, M., Bazzi, L., Salghi, R., Hammouti, B., and Albourine, A. (2010). The inhibited effect of cysteine towards the corrosion of copper in nitric acid solution. Open Corrosion J. 3: 59.Suche in Google Scholar

Bernardi, E., Chiavari, C., Lenza, B., Martini, C., Morselli, L., Ospitali, F., and Robbiola, L. (2009). The atmospheric corrosion of quaternary bronzes: the leaching action of acid rain. Corrosion Sci. 51: 159–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2008.10.008.Suche in Google Scholar

Cano, A., Shchukarev, A., and Reguera, E. (2019). Intercalation of pyrazine in layered copper nitroprusside: synthesis, crystal structure and XPS study. J. Solid State Chem. 273: 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2019.02.015.Suche in Google Scholar

Caprioli, F., Marrani, A.G., and Castro, V.D. (2014). Tuning the composition of aromatic binary self-assembled monolayers on copper: an XPS study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 303: 30–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.02.035.Suche in Google Scholar

Casella, I.G. and Contursi, M. (2006). An electrochemical and XPS study of the electrodeposited binary Pd – Sn catalyst: the electroreduction of nitrate ions in acid medium. J. Electroanal. Chem. 588: 147–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2005.12.015.Suche in Google Scholar

Chang, T., Herting, G., Jin, Y., Leygraf, C., and Wallinder, I.O. (2018a). The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: patina evolution in chloride-containing atmospheres. Corrosion Sci. 133: 190–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.01.027.Suche in Google Scholar

Chang, T., Wallinder, I.O., Jin, Y., and Leygraf, C. (2018b). The golden alloy Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn: a multi-analytical surface characterization. Corrosion Sci. 131: 94–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2017.11.014.Suche in Google Scholar

Chauhan, D.S., Madhan, K.A., and Quraishi, M.A. (2019). Hexamethylenediamine functionalized glucose as a new and environmentally benign corrosion inhibitor for copper. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 150: 99–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2019.07.020.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Y. and Erbe, A. (2018). The multiple roles of an organic corrosion inhibitor on copper investigated by a combination of electrochemistry-coupled optical in situ spectroscopies. Corrosion Sci. 145: 232–238, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.09.018.Suche in Google Scholar

Dang, N., Quoc, V., Nguyen, T., and Pham, V.H. (2016). Yttrium 3-(4-nitrophenyl)-2-propenoate used as inhibitor against copper alloy corrosion in 0.1 M NaCl solution. Eval. Progr. Plann. 112: 451–461.10.1016/j.corsci.2016.08.005Suche in Google Scholar

Dehghani, A., Ghasem, B., and Bahram, R. (2019). Detailed macro-/micro-scale exploration of the excellent active corrosion inhibition of a novel environmentally friendly green inhibitor for carbon steel in acidic environments. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 100: 239–261, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2019.04.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Deshpande, P., Aniket, K., Abhijit, B., Kalendova, A., and Kohl, M. (2022). Impressed current cathodic protection (ICCP) of mild steel in association with zinc based paint coating. Mater. Today Proc. 5: 1660–1665, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.09.145.Suche in Google Scholar

Drach, A., Tsukrova, I., DeCew, J., Aufrecht, J., Grohbauer, A., and Hofmann, U. (2013). Field studies of corrosion behaviour of copper alloys in natural seawater. Corrosion Sci. 76: 453–464, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2013.07.019.Suche in Google Scholar

Farahati, R., Ali, G., Morteza, M.S., and Jafar, R. (2019). Synthesis and potential applications of some thiazoles as corrosion inhibitor of copper in 1 M HCl: experimental and theoretical studies. Prog. Org. Coating 132: 417–428, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.04.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Finšgar, M. (2013a). 2-mercaptobenzimidazole as a copper corrosion inhibitor. Part I. Long-term immersion, 3D-profilometry, and electrochemistry. Corrosion Sci. 72: 82–89.10.1016/j.corsci.2013.03.011Suche in Google Scholar

Finšgar, M. (2013b). 2-mercaptobenzimidazole as a copper corrosion inhibitor. Part II. Surface analysis using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Corrosion Sci. 72: 90–98.10.1016/j.corsci.2013.03.010Suche in Google Scholar

Finšgar, M. (2013c). EQCM and XPS analysis of 1,2,4-triazole and 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole as copper corrosion inhibitors in chloride solution. Corrosion Sci. 77: 350–359.10.1016/j.corsci.2013.08.026Suche in Google Scholar

Finšgar, M. and Kek Merl, D. (2014). An electrochemical, long-term immersion, and XPS study of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole as a copper corrosion inhibitor in chloride solution. Corrosion Sci. 83: 164–175.10.1016/j.corsci.2014.02.016Suche in Google Scholar

Ghelichkhah, Z., Samin, S., Khalil, F., Sepideh, B., Sohrab, A., and Digby, D.M. (2015). L-cysteine/polydopamine nanoparticle-coatings for copper corrosion protection. Corrosion Sci. 91: 129–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2014.11.011.Suche in Google Scholar

Ghiara, G., Spotorno, R., Delsante, S., Tassistro, G., Piccardo, P., and Cristiani, P. (2019). Dezincification inhibition of a food processing brass OT60 in presence of pseudomonas fluorescens. Corrosion Sci. 157: 370–381, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2019.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Goyal, M., Sudershan, K., Indra, B., Chandrabhan, V., and Eno, E.E. (2018). Organic corrosion inhibitors for industrial cleaning of ferrous and non-ferrous metals in acidic solutions: a review. J. Mol. Liq. 256: 565–573, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.02.045.Suche in Google Scholar

Han, T., Guo, J., Zhao, Q., Wu, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2020). Enhanced corrosion inhibition of carbon steel by pyridyl gemini surfactants with different alkyl chains. Mater. Chem. Phys. 240: 122156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122156.Suche in Google Scholar

Hassan, H.H., Abdelghani, E., and Amin, M.A. (2007). Inhibition of mild steel corrosion in hydrochloric acid solution by triazole derivatives. Part I: polarization and EIS studies. Electrochim. Acta 52: 6359–6366, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2007.04.046.Suche in Google Scholar

Hosseini, M., Fotouhi, L., Ehsani, A., and Maryam, N. (2017). Enhancement of corrosion resistance of polypyrrole using metal oxide nanoparticles: potentiodynamic and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 505: 213–219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2017.05.097.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Huang, H., Wang, Z., Gong, Y., Gao, F., Luo, Z., Zhang, S., and Li, H. (2017). Water soluble corrosion inhibitors for copper in 3.5 wt% sodium chloride solution. Corrosion Sci. 123: 339–350.10.1016/j.corsci.2017.05.009Suche in Google Scholar

Idczak, K., Mazur, P., Zuber, S., Markowski, L., Ski, M., and Bili, S. (2014). Growth of thin zirconium and zirconium oxides films on the n-GaN (0001) surface studied by XPS and LEED. Appl. Surf. Sci. 304: 29–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.01.102.Suche in Google Scholar

Islam, S. and Masatoshi, S. (2019). Corrosion inhibition of mild steel by metal cations in high pH simulated fresh water at different temperatures. Corrosion Sci. 153: 100–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2019.03.040.Suche in Google Scholar

Ismail, K.M. (2007). Evaluation of cysteine as environmentally friendly corrosion inhibitor for copper in neutral and acidic chloride solutions. Electrochim. Acta 52: 7811–7819, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2007.02.053.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiang, L., Qiang, Y., Lei, Z., Wang, J., Qin, Z., and Xiang, B. (2018). Excellent corrosion inhibition performance of novel quinoline derivatives on mild steel in HCl media: experimental and computational investigations. J. Mol. Liq. 255: 53–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.133.Suche in Google Scholar

Jin, Y., Sui, Y., Wen, L., Ye, F., Sun, M., and Wang, Q. (2013). Competitive adsorption of PEG and SPS on copper surface in acidic electrolyte containing Cl. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160: 20–27, https://doi.org/10.1149/2.021302jes.Suche in Google Scholar

Kamburova, K., Boshkova, N., and Radeva, T. (2021). Composite coatings with polymeric modified zno nanoparticles and nanocontainers with inhibitor for corrosion protection of low carbon steel. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 609: 125741, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125741.Suche in Google Scholar

Kazansky, L.P., Pronin, Y.E., and Arkhipushkin, I.A. (2014). XPS study of adsorption of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole on a brass surface. Corrosion Sci. 89: 21–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2014.07.055.Suche in Google Scholar

Khaled, K.F. (2010). Corrosion control of copper in nitric acid solutions using some amino acids – a combined experimental and theoretical study. Corrosion Sci. 52: 3225–3234, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2010.05.039.Suche in Google Scholar

Khatibi, S., Ostadhassan, M., Hackley, P., Tuschel, D., Abarghani, A., and Bubach, B. (2019). Understanding organic matter heterogeneity and maturation rate by Raman spectroscopy. Int. J. Coal Geol. 206: 46–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2019.03.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Koitaya, T., Yuichiro, S., Yuki, Y., Kozo, M., and Shinya, Y. (2017). Electronic states and growth modes of Zn atoms deposited on Cu (111) studied by XPS, UPS and DFT. Surf. Sci. 663: 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2017.03.015.Suche in Google Scholar

Kong, D., Dong, C., Xiao, K., and Li, X. (2017). Effect of temperature on copper corrosion in high-level nuclear waste environment. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China 27: 1431–1438, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1003-6326(17)60165-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Krätschmer, A., Odnevall, W.I., and Leygraf, C. (2002). The evolution of outdoor copper patina. Corrosion Sci. 44: 425–450.10.1016/S0010-938X(01)00081-6Suche in Google Scholar

Kumar, D., Enom, E., Quraishi, M.A., and Chandrabhan, V. (2019). Electrochemical surface and density functional theory study of acetohydroxamic and benzohydroxamic acids as corrosion inhibitors for copper in 1 M HCl. Results Phys. 13: 102194.10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102194Suche in Google Scholar

Landoulsi, J., Genet, M.J., Fleith, S., Touré, Y., Liascukiene, I., Méthivier, C., and Rouxhet, P.G. (2016). Organic adlayer on inorganic materials: XPS analysis selectivity to cope with adventitious contamination. Appl. Surf. Sci. 383: 71–83, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.04.147.Suche in Google Scholar

Lesiak, B., Kövér, L., Tóth, J., Zemek, J., Jiricek, P., Kromka, A., and Rangam, N. (2018). Hybridisations in carbon nanomaterials – XPS and (X) AES study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 452: 223–231, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.04.269.Suche in Google Scholar

Lewera, A., Barczuk, P.J., Skorupska, K., Miecznikowski, K., Salamonczyk, M., and Kulesza, P.J. (2011). Influence of polyoxometallate on oxidation state of tin in Pt/Sn nanoparticles and its importance during electrocatalytic oxidation of ethanol – combined electrochemical and XPS study. J. Electroanal. Chem. 662: 93–99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2011.03.038.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, L., Li, W., Xiong, Z., Xia, D., Yang, C., Wang, W., and Sun, Y. (2019a). Synergistic effect of iron and copper oxides on the formation of persistent chlorinated aromatics in iron ore sintering based on in situ XPS analysis. J. Hazard Mater. 366: 202–209, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.11.105.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Liu, L., Meng, Y., Volinsky, A.A., Zhang, H., and Wang, L. (2019b). Inluences of albumin on in vitro corrosion of pure Zn in artificial plasma. Corrosion Sci. 153: 341–356, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2019.04.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Loto, C.A., Fayomi, O.S.I., Loto, R.T., and Popoola, A.P.I. (2019). Potentiodynamic polarization and gravimetric evaluation of corrosion of copper in 2M H2SO4 and its inhibition with ammonium dichromate. Procedia Manuf. 35: 413–418, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2019.05.061.Suche in Google Scholar

Markin, A.V., Markina, N.E., Popp, J., and Cialla-May, D. (2018). Copper nanostructures for chemical analysis using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Trends Anal. Chem. 108: 247–259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2018.09.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Mel, A.A.E., Angleraud, B., Gautron, E., Granier, A., and Tessier, P.Y. (2011). XPS study of the surface composition modification of Nc–Tic/c nanocomposite films under in situ argon ion bombardment. Thin Solid Films 519: 3982–3985, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2011.01.200.Suche in Google Scholar

Milošev, I., Kovačević, N., Kovač, J., and Kokalj, A. (2015). The roles of mercapto, benzene and methyl groups in the corrosion inhibition of imidazoles on copper. I: experimental characterization. Corrosion Sci. 98: 107–118.10.1016/j.corsci.2015.05.006Suche in Google Scholar

Morozov, I.G., Belousova, O.V., Ortega, D., Mafina, M., and Kuznetcov, M.V. (2015). Structural, optical, XPS and magnetic properties of Zn particles capped by ZnO nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 633: 237–245, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.01.285.Suche in Google Scholar

Pareek, S., Deepti, J., Shamima, H., Amrita, B., and Rahul, S. (2019). A new insight into corrosion inhibition mechanism of copper in aerated 3.5 wt% NaCl solution by eco-friendly imidazopyrimidine dye: experimental and theoretical approach. Chem. Eng. J. 358: 725–742.10.1016/j.cej.2018.08.079Suche in Google Scholar

Perales-Rondon, J.V., Sheila, H., Aranzazu, H., and Alvaro, C. (2019). Effect of chloride and pH on the electrochemical surface oxidation enhanced Raman scattering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 473: 366–372, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.12.148.Suche in Google Scholar

Pramanik, K., Priyabrata, S., and Dipankar, B. (2019). International journal of biological macromolecules 3 – mercapto – propanoic acid modified cellulose filter paper for quick removal of arsenate from drinking water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 122: 185–194, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.065.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Qiang, Y., Fu, S., Zhang, S., Chen, S., and Zou, X. (2018). Designing and fabricating of single and double alkyl-chain indazole derivatives self-assembled monolayer for corrosion inhibition of copper. Corrosion Sci. 140: 111–121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.06.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Quraishi, M.A. (2013). Electrochemical and theoretical investigation of triazole derivatives on corrosion inhibition behavior of copper in hydrochloric acid medium. Corrosion Sci. 70: 161–169.10.1016/j.corsci.2013.01.025Suche in Google Scholar

Ramezanzadeh, M., Ghasem, B., and Bahram, R. (2019). Study of the synergistic effect of mangifera indica leaves extract and zinc ions on the mild steel corrosion inhibition in simulated seawater: computational and electrochemical studies. J. Mol. Liq. 292: 111387, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111387.Suche in Google Scholar

Rao, B.V.A. and Reddy, N.M. (2017). Formation, characterization and corrosion protection efficiency of self-assembled 1-octadecyl-1H-imidazole films on copper for corrosion protection. Arab. J. Chem. 10(Suppl. 2): S3270–S3283, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.12.026.Suche in Google Scholar

Ravichandran, R., Nanjundan, S., and Rajendran, N. (2004). Effect of benzotriazole derivatives on the corrosion and dezincification of brass in neutral chloride solution. J. Appl. Electrochem. 34: 1171–1176, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10800-004-1702-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Salcı, A. and Ramazan, S. (2018). Fabrication of rhodanine self-assembled monolayer thin films on copper: solvent optimization and corrosion inhibition studies. Prog. Org. Coating 125: 516–524.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2018.09.020Suche in Google Scholar

Serrano-Ruiz, J.C., Huber, G.W., Sánchez-Castillo, M.A., Dumesic, J.A., and Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. (2006). Effect of Sn addition to Pt/CeO2–Al2O3 and Pt/Al2O3 catalysts: an XPS, 119Sn Mössbauer and microcalorimetry study. J. Catal. 241: 378–388, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2006.05.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Shinato, K.W., Huang, F., Xue, Y., Wen, L., and Jin, Y. (2019). The protection role of cysteine for Cu–5Zn–5Al–1Sn alloy corrosion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Appl. Sci. 9: 3896.10.3390/app9183896Suche in Google Scholar

Shinato, K.W., Huang, F., Xue, Y., Wen, L., Jin, Y., Mao, Y., and Luo, Y. (2020). Synergistic inhibitive effect of cysteine and iodide ions on corrosion behavior of copper in acidic sulfate solution. Rare Met. 40: 1317–1328, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-019-01366-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Singh, A., Ansarim, K.R., Dheeraj, S., Quraishi, M.A., Lgaz, H., and Ill-Min, C. (2020). Comprehensive investigation of steel corrosion inhibition at macro/micro level by ecofriendly green corrosion inhibitor in 15% HCl medium. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 560: 225–236, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2019.10.040.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Singh, D., Quraishi, M.A., Carrière, C., Seyeux, A., Marcus, P., and Singh, A. (2019). Electrochemical, ToF-SIMS and computational studies of 4-amino-5-methyl-4H-1, 2, 4-triazole-3-thiol as a novel corrosion inhibitor for copper in 3.5% NaCl. J. Mol. Liq. 289: 111113.10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111113Suche in Google Scholar

Sinha, S. and Mukherjee, M. (2018). A study of adventitious contamination layers on technically important substrates by photoemission and NEXAFS spectroscopies. Vaccum 148: 48–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2017.10.038.Suche in Google Scholar

Stańczyk, K., Dziembaj, R., Piwowarska, Z., and Witkowski, S. (1995). Transformation of nitrogen structures in carbonization of model compounds determined by XPS. Carbon 33: 1383–1392.10.1016/0008-6223(95)00084-QSuche in Google Scholar

Talluri, B. and Thomas, T. (2017). Indications of hard-soft-acid-base interactions governing formation of ultra-small (r < 3 nm) digestively ripened copper oxide quantum-dots. Chem. Phys. Lett. 685: 84–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2017.07.041.Suche in Google Scholar

Thanapackiam, P., Subramaniam, R., Subramanian, S.S., and Kumaravel, M. (2016). Electrochemical evaluation of inhibition efficiency of ciprofloxacin on the corrosion of copper in acid media. Mater. Chem. Phys. J. 174: 129–137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2016.02.059.Suche in Google Scholar

Torrisi, L., Silipigni, L., Cutroneo, M., and Torrisi, A. (2020). Graphene oxide as a radiation sensitive material for XPS dosimetry. Vacuum 173: 109175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2020.109175.Suche in Google Scholar

Touir, R., Dkhireche, N., Ebn, T.M., Lakhrissi, M., Lakhrissi, B., and Sfaira, M. (2009). Corrosion and scale processes and their inhibition in simulated cooling water systems by monosaccharides derivatives part I: EIS study. Desalination 249: 922–928, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2009.06.068.Suche in Google Scholar

Vinothkumar, K. and Mathur, G.S. (2018). Corrosion inhibition ability of electropolymerised composite film of 2-amino-5-mercapto-1,3,4-thiadiazole/TiO2 deposited over the copper electrode in neutral medium. Mater. Today Commun. 14: 27–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2017.12.007.Suche in Google Scholar

Virnovskaia, A., Jørgensen, S., Hafizovic, J., Prytz, Ø., Kleimenov, E., Hävecker, M., Bluhm, H., Knop-Gericke, A., Schlögl, R., and Olsbye, U. (2007). In situ XPS investigation of Pt(Sn)/Mg(Al)O catalysts during ethane dehydrogenation experiments. Surf. Sci. 601: 30–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2006.09.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Wagner, A.J., Wolfe, G.M., and Fairbrother, D.H. (2003). Reactivity of vapor-deposited metal atoms with nitrogen-containing polymers and organic surfaces studied by in situ XPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 219: 317–328, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-4332(03)00705-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Wagner, C.D., Riggs, W.M., Davis, L.E., and Moulder, J.F. (1979). XPS handbook (Perkin Elmer).Pdf. Muilenberg, Minnesota.Suche in Google Scholar

Wu, Z.-W., Tyan, S.-L., Chen, H.-H., Huang, J.-C.-A., Huang, Y.-C., Lee, C.-R., and Mo, T.-S. (2017). Temperature-dependent photoluminescence and XPS study of ZnO nanowires grown on flexible Zn foil via thermal oxidation. Superlattice. Microst. 107: 38–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spmi.2017.04.016.Suche in Google Scholar

Xu, Y., Zhang, S., Li, W., Guo, L., Xu, S., Feng, L., and Madkour, L.H. (2018). Experimental and theoretical investigations of some pyrazolo-pyrimidine derivatives as corrosion inhibitors on copper in sulfuric acid solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 459: 612–620, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.08.037.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, B., Wang, D., Wang, T., Zhang, H., Jia, F., and Song, S. (2019). Effect of Cu2+ and Fe3+ on the depression of molybdenite in flotation. Miner. Eng. 130: 101–109, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2018.10.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Yu, Y., Yang, D., Zhang, D., Wang, Y., and Gao, L. (2017). Anti-corrosion film formed on HAl77-2 copper alloy surface by aliphatic polyamine in 3 wt% NaCl solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 392: 768–776.10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.09.118Suche in Google Scholar

Yu, Z., Liu, Y., Liang, L., Shao, L., Li, X., Zeng, H., Feng, X., and Cao, K. (2019). Inhibition performance of a multi-sites adsorption type corrosion inhibitor on P110 steel in acidic medium. Chem. Phys. Lett. 735: 136773, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2019.136773.Suche in Google Scholar

Zatsepin, D.A., Boukhvalov, D.W., Gavrilov, N.V., Kurmaev, E.Z., and Zatsepin, A.F. (2017). XPS-and-DFT analyses of the Pb 4f—Zn 3s and Pb 5d—O 2s overlapped ambiguity contributions to the final electronic structure of bulk and thin-film Pb-modulated zincite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 405: 129–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.01.310.Suche in Google Scholar

Zatsepin, D.A., Zatsepin, A.F., Boukhvalov, D.W., Kurmaev, E.Z., and Gavrilov, N.V. (2016). Sn-loss effect in a Sn-implanted α-SiO2 host-matrix after thermal annealing: a combined XPS, PL, and DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 367: 320–326, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.01.126.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, D., Gao, L., and Zhou, G. (2003). Synergistic effect of 2-mercapto benzimidazole and KI on copper corrosion inhibition in aerated sulfuric acid solution. J. Appl. Electrochem. 33: 361–366, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024403314993.10.1023/A:1024403314993Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, D., Xie, B., Gao, L., Cai, Q., Joo, H.G., and Kang, Y.L. (2011). Intramolecular synergistic effect of glutamic acid, cysteine and glycine against copper corrosion in hydrochloric acid solution. Thin Solid Films 520: 356–361, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2011.07.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, X., Odnevall Wallinder, I., and Leygraf, C. (2014). Mechanistic studies of corrosion product flaking on copper and copper-based alloys in marine environments. Corrosion Sci. 85: 15–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2014.03.028.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editor’s Note

- A demonstration of resilience

- Reviews

- Scanning electrochemical microscopy methods (SECM) and ion-selective microelectrodes for corrosion studies

- Corrosion inhibitors for AA6061 and AA6061-SiC composite in aggressive media: a review

- Original Articles

- Oxidation–reduction reactions and hydrogenation of steels of different structures in chloride-acetate solutions in the presence of iron sulfides

- The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: effect of immersion time and anti-corrosion activity of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution

- Corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions with different pH adjusted by ammonia

- Comparison of protective coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilanes and possibilities of spectroelectrochemical approaches for their investigation

- Corrosion behaviour OF HVOF deposited Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editor’s Note

- A demonstration of resilience

- Reviews

- Scanning electrochemical microscopy methods (SECM) and ion-selective microelectrodes for corrosion studies

- Corrosion inhibitors for AA6061 and AA6061-SiC composite in aggressive media: a review

- Original Articles

- Oxidation–reduction reactions and hydrogenation of steels of different structures in chloride-acetate solutions in the presence of iron sulfides

- The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: effect of immersion time and anti-corrosion activity of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution

- Corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions with different pH adjusted by ammonia

- Comparison of protective coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilanes and possibilities of spectroelectrochemical approaches for their investigation

- Corrosion behaviour OF HVOF deposited Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel