Abstract

The ammonia-hydrazine shutdown protection method is widely used in thermal power plants in China because of its good protective performance. However, the toxicity and safety of hydrazine have restricted its use in many power plants, and it is necessary to improve the shutdown protection techniques. In this paper, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and potentiodynamic polarization curves were used to study the effect of hydrazine in water solutions of different pH values, adjusted with ammonia on the corrosion behavior of carbon steel. It was found that in the water solution without hydrazine, the corrosion resistance of a carbon steel electrode increased with raising the pH. When the pH value of water increased to 10.5, the impedance value of the carbon steel increased significantly, the corrosion current density decreased from 26.06 μA·cm−2 at pH 10.0 to 2.36 μA·cm−2, and the steel surface was passivated. Hydrazine had different effects on the electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel in water solutions with various pH. When the pH of water was not higher than 10.0, hydrazine had a good corrosion inhibition effect on carbon steel. When the pH of water was not lower than 10.5, the addition of hydrazine inhibited the passivation of carbon steel and promoted the corrosion. The adsorption and substitutional oxidation of hydrazine in the anode region of carbon steel surface should be the reasons for the above phenomenon.

1 Introduction

Generally, the main material of thermal power plant boilers is carbon steel. Carbon steel has high thermal strength, toughness and structural stability, and still maintains good structural stability under the action of high temperature and high-pressure steam in the boiler. However, it is a material that is prone to corrosion. According to statistics, more than 1000 boilers are scrapped in China each year due to corrosion, and the annual loss of boiler metal corrosion has reached more than 300 million yuan (Fu et al. 2021). The corrosion of the boiler during the shutdown period is often more serious than that during operation. This is mainly due to the fact that air enters the inside of the boiler during the shutdown period, and this accelerates the corrosion of boiler steel under the action of internal water vapor, O2 and CO2 in the air, etc. The corrosion of the boiler during the shutdown period not only shortens the service life of the boiler, but also endangers the safe and economical operation of the boiler (Fu et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2017). Therefore, it is very important to protect the boiler against corrosion during the shutdown period. There are several main types of shutdown protection methods often used in power plants: the nitrogen filling method and steam pressure maintenance method to prevent air from entering the water vapor system, the drying method to reduce the internal humidity of the water vapor system, and the corrosion inhibitor method to form a protective film on the metal surface (Liu et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020; Xiong et al. 2020). Corrosion inhibitor protection is a commonly used method. It concludes a film-forming amine protection method, a gas phase corrosion inhibitor method, ammonia-hydrazine method, etc. Among them, the ammonia-hydrazine method is suitable for short-term or long-term shutdown protection of boilers when no overhaul is required. When using this method for protection, the pH value of water is adjusted to 10.0–10.5 with ammonia, and in addition, 200–300 mg/L hydrazine is added in addition (Standards China 2017). It is generally believed that hydrazine can be used as both an oxygen scavenger and an anode-type corrosion inhibitor to inhibit carbon steel corrosion during shutdown protection (Prifiharni et al. 2020). The ammonia-hydrazine protection method requires strict control of the pH value and the amount of hydrazine in the water. This method can protect the boiler well at room temperature. The disadvantage is that the hydrazine is highly toxic. When hydrazine is in contact with human skin, it has a strong corrosive effect on human skin and mucous membranes, and it can also cause serious damage to the liver. Also, it is as well as suspected to have carcinogenic effects. Once discharged, it will cause serious pollution to the water environment (Matsumura 2011; Vijay and Velmathi 2020; Yang et al. 2021). Therefore, improving the ammonia-hydrazine protection process so that it has a good protection effect on boiler steel, and no or less hydrazine is used in the protection process, is an urgent problem to be solved in the current power plant shutdown protection in China. In this paper, the corrosion behavior of carbon steel in water solutions with different pH values was studied, the effect of hydrazine on the corrosion process of carbon steel was discussed. Also, the feasibility of not using hydrazine in the ammonia-hydrazine method for shutdown protection was analysed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and test solutions

The experimental material is 20G carbon steel (type st45.8 in Germany and type SA 106B in USA), and its main chemical composition is shown in Table 1. The carbon steel was cut into test pieces with a size of 10 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm and copper wire was welded to the back of the piece. The surfaces were then encapsulated with epoxy resin, except for the work surface which had dimensions of 10 mm × 10 mm. Before the measurements, the electrode surfaces were abraded step by step with 200–2000 mesh metallographic sandpaper and then degreased with ethanol and rinsed with deionized water.

Composition of carbon steel used in the experiment (wt%).

| Element | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight percentage (%) | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.023 | 0.012 | Balance |

The experimental solutions were prepared by using deionized water with a pH of 6.89, a conductivity of 1.2 μS/cm, a dissolved oxygen concentration of approximately 0.50 mg/L, and a temperature of 25 °C. All chemicals used in the experiments were of analytical grade. The experimental water solution was put into a sealable flask, and after the electrode was immersed in the solution, it was sealed for 72 h. The electrochemical measurements and the corrosion morphology observation were carried out, respectively.

2.2 Electrochemical measurements

The electrochemical measurements were performed in a CHI604 electrochemical workstation. A three-electrode system was used with a platinum electrode and a saturated calomel electrode as counter and reference, respectively. The working electrode and the reference electrode were connected by a salt bridge. The potentiodynamic polarization curves were measured over the potential range of −0.3 to 1.0 V (vs SCE) at a scan rate of 1.0 mV/s. In order to eliminate the influence of solution resistance on corrosion current density, IR compensation was carried out when measuring polarization curves. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements were performed at open circuit potential with a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz and an amplitude of 10 mV. All experiments were repeated more than three times to ensure their reproducibility.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Corrosion resistance of carbon steel in water solutions of different pH

According to Pourbaix Diagrams of a Fe-H2O system, it can be seen that the corrosion of iron is greatly affected by the pH value of the water solution (Wang et al. 2016). In water solution with low pH, corrosion of iron occurs to produce soluble Fe2+ ions. As the pH of the water rises, the corrosion products gradually transform into iron oxides, and passivation occurs when dense oxides form on the iron surface. However, when the pH of the water solution is too high, iron is corroded to generate soluble HFeO2− ions.

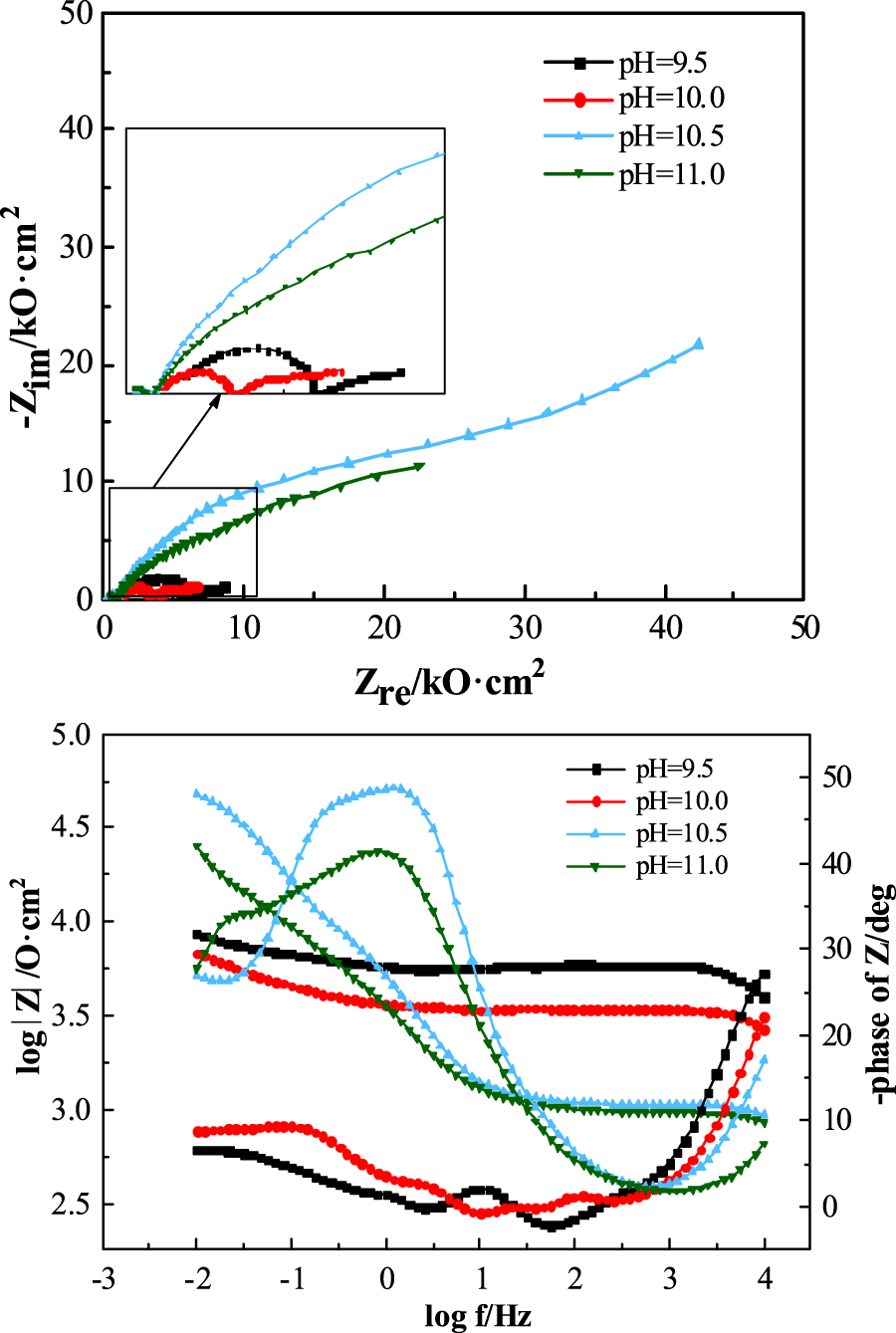

The corrosion resistance of metals in different corrosive media can be characterized by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The EIS of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions of different pH values adjusted with ammonia were measured, and the results are shown in Figure 1.

Nyquist and Bode plots of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions of different pH values.

It can be seen from Figure 1 that the impedance value of the carbon steel increased as the pH of the water rose, with a maximum at a pH of 10.5. When the pH of water is 9.5 and 10.0, due to the low conductivity of the water solution, a high frequency semicircle appeared in the Nuiquist plot. This was mainly caused by the resistance and capacitance of the contact area between the Lukin capillary end and the solution, and it is independent of the electrochemical processes (Feng et al. 1991). As the pH of water increased to 10.5 and 11.0, the high frequency semicircle almost disappeared; this may be related to the rapid increase in solution conductivity. The impedance value of carbon steel at pH 11.0 was lower than that in solution at pH 10.5, which may be due to the fact that the improvement of the conductivity of the solution accelerated the reaction process of the electrode.

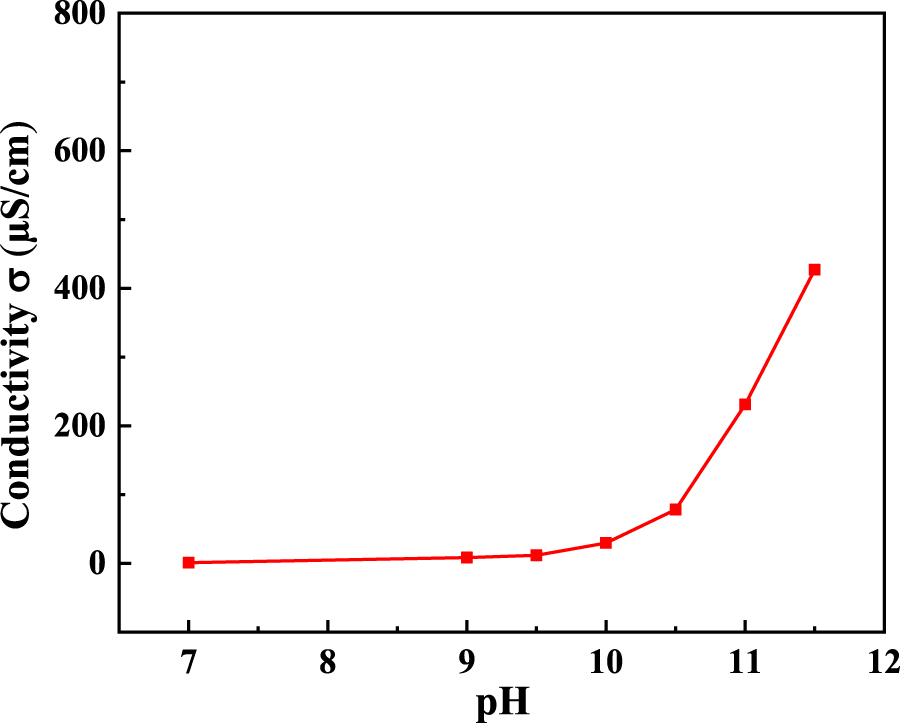

When using ammonia for pH control of deionised water, the conductivity of the water increased with the addition of ammonia. The conductivity of water as a function of pH was measured during ammonia addition, and the results are shown in Figure 2. It is shown that with the increase of the water pH (that is, an increase of ammonia addition), the conductivity increased slowly at first, and when the pH was adjusted to 10.5 and above, the conductivity increased rapidly. The increase in conductivity implies a decrease in the resistance of the water solution, which is beneficial to the progress of the electrode reaction.

Conductivity of water solutions as a function of pH values.

Due to the appearance of the high frequency pseudo-capacitance arc in the Nyquist plots of Figure 1, the EIS here was not fitted, and the impedance modulus value at 0.01 Hz |Z|0.01 was used directly to analyse the corrosion resistance of the electrodes (Sha et al. 2019). Table 2 shows the |Z|0.01 values of the carbon steel electrode in water solutions at different pH, showing that the |Z|0.01 values were smaller at pH 9.5 and 10.0, that is 8.55 and 6.77 kΩ·cm2, respectively. When the pH of the water solution increased to 10.5, the |Z|0.01 value of the carbon steel electrode increased significantly to 47.69 kΩ·cm2, which was about seven times higher than that at pH 10.0, indicating that passivation of the carbon steel surface might occur under this condition and the corrosion resistance was significantly enhanced. When the pH was further increased to 11.0, the |Z|0.01 value decreased to 25.48 kΩ·cm2, which should be related to the increased conductivity of the water solution.

|Z|0.01 values for carbon steel in water solutions of different pH values.

| pH | 9.5 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 11.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |Z|0.01 (kΩ·cm2) | 8.55 | 6.77 | 47.69 | 25.48 |

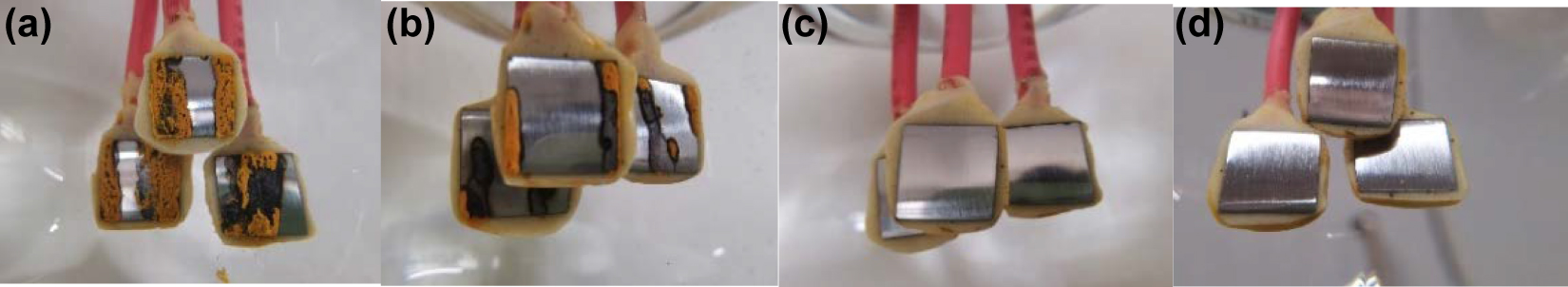

The surface morphology of the electrodes after the experiments is shown in Figure 3, which shows that in the water solutions with pH 9.5 and 10.0, loose and yellow corrosion products were formed on the surface of the electrode. In water solutions with pH 10.5 and 11.0, there was no obvious corrosion on the surface of the carbon steel electrodes. This should be attributed to the passivation of the carbon steel surface under these alkaline conditions, and the generated passivation film inhibited the corrosion of the carbon steel.

Surface morphologies of carbon steel electrodes after immersion in water solution with different pH values for 72 h. pH values: (a) 9.5, (b) 10.0, (c) 10.5, and (d) 11.0.

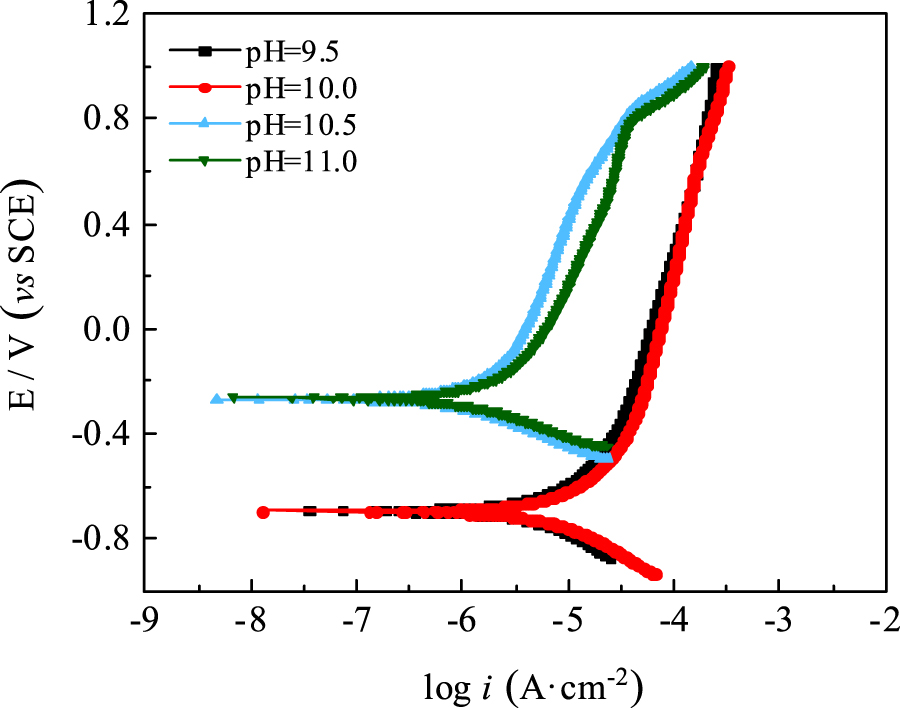

The polarization curves of the carbon steel electrodes were measured after immersion in water solutions of different pH values for 72 h. The results are shown in Figure 4. Table 2 shows the corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (icorr) of the carbon steel electrodes obtained from the polarization curves.

Polarisation curves of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions of different pH values.

The results in Figure 4 and Table 3 show that when the pH of the water solutions was 9.5 and 10.0, the Ecorr of the carbon steel electrodes was more negative, and the icorr was higher and did not change significantly with pH. When the pH of the water solutions rose to 10.5, the icorr decreased from 26.06 μA·cm−2 at pH 10.0 to 2.36 μA·cm−2, and the Ecorr shifted positively from −0.696 V to −0.271 V, indicating that the anodic dissolution process of carbon steel was effectively inhibited. The icorr increased slightly to 2.51 μA·cm−2 when the pH was adjusted to 11.0. A further increase in the pH resulted in a significant increase in the conductivity of the water solution. This reduced the solution resistance, thus leading to a decrease in the total resistance of the electrode reaction and an increase in the corrosion current density.

E corr and icorr of carbon steel in water solutions of different pH values.

| pH | 9.5 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 11.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E corr (V vs SCE) | −0.693 | −0.696 | −0.271 | −0.265 |

| E corr (V vs SHE) | −0.452 | −0.455 | −0.030 | −0.024 |

| i corr (μA·cm−2) | 24.04 | 26.06 | 2.36 | 2.51 |

The thermodynamic reasons for the occurrence of the above phenomenon can be analysed according to Pourbaix Diagrams (Revie 2011). It can be seen from Table 3 that, the pH value corresponding to the three-phase point of coexistence of Fe, Fe2+, and Fe3O4 for carbon steel in water should be greater than 10.0. Assuming that pH value is 10.3, the equilibrium potential corresponding to this three-phase point is −0.694 V (Calculated according to the equilibrium relationship between Fe3O4 and Fe in water). This potential is also the equilibrium potential for the Fe2+/Fe electrode reaction. Table 3 shows that when the pH of the water was 9.5 and 10.0, the corrosion potential of the carbon steel electrode was −0.452 V versus SHE and −0.455 V versus SHE, respectively. This was in the corrosion region of the Pourbaix Diagrams of Fe/H2O system, so the carbon steel was in a state of self-corrosion. When the pH of the water was 10.5 and 11.0, the corrosion potential of the carbon steel was −0.030 V versus SHE and −0.024 V versus SHE, respectively. Both of these values are much higher than the equilibrium potentials of Fe3O4/Fe and Fe2O3/Fe3O4 electrodes pairs in the Pourbaix Diagrams. So, the carbon steel was in the passivation region and a passivation film of Fe2O3 should be generated on the surface.

Thus, the electrode reactions on carbon steel surface in water solutions of different pH may be as follows:

Anodic reactions:

At pH 9.5 and 10.0 (corrosion occurs)

At pH 10.5 and 11.0 (passivation occurs)

Cathodic reaction:

3.2 Corrosion behavior of carbon steel in water solutions treated with ammonia-hydrazine

3.2.1 Analysis with electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

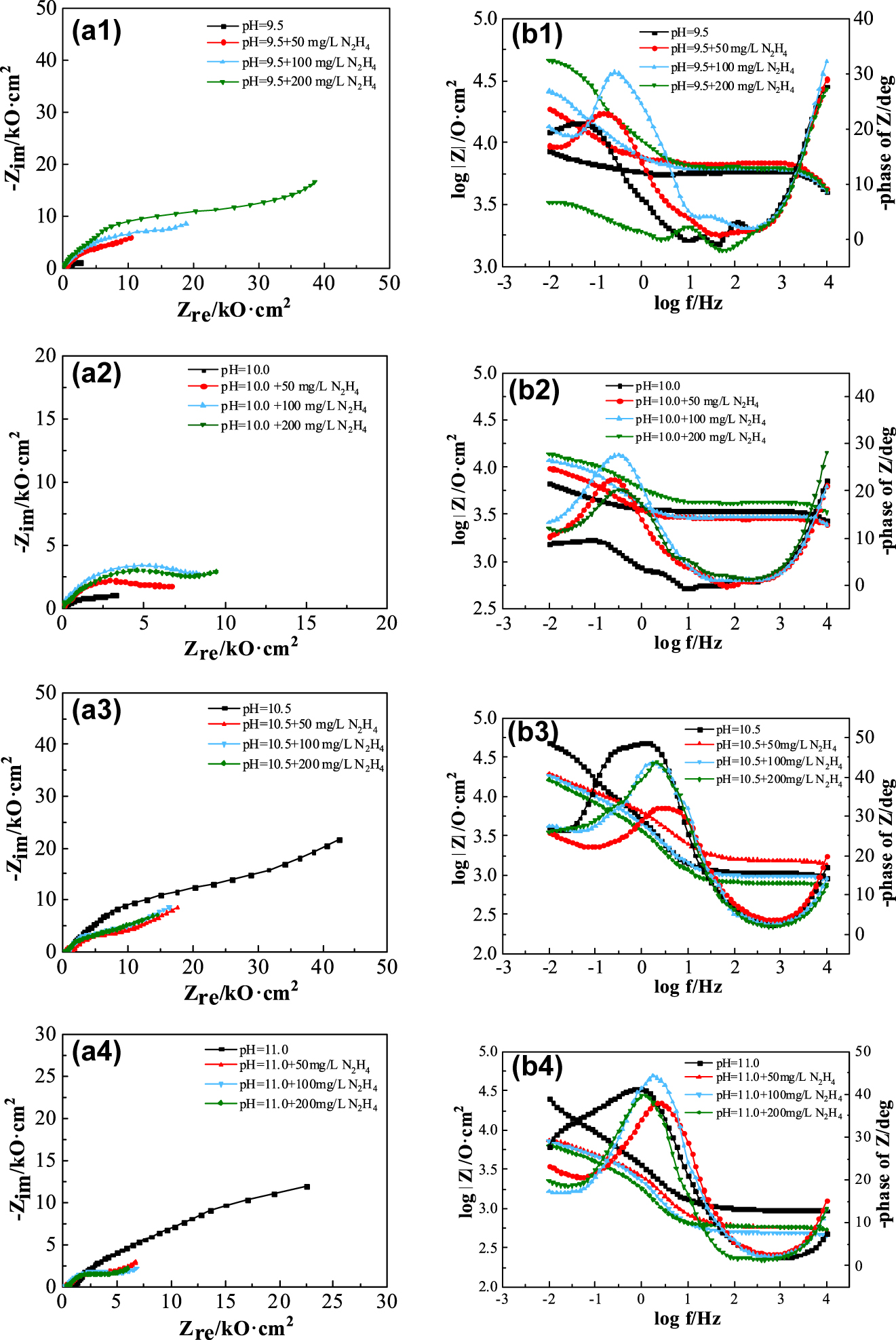

Figure 5 shows the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of carbon steel immersed in water solutions treated with ammonia-hydrazine at different pH values for 72 h, respectively. Table 4 shows the |Z|0.01 values of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions treated with ammonia-hydrazine at different pH.

EIS of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions treated with ammonia-hydrazine at different pH values.

|Z|0.01 values of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions treated with ammonia-hydrazine at different pH values (kΩ·cm2).

| N2H4 concentration (mg/L) | 0 | 50 | 100 | 200 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 9.5 | 8.55 | 18.75 | 25.90 | 46.11 |

| 10.0 | 6.77 | 9.76 | 11.73 | 13.95 | |

| 10.5 | 47.69 | 25.48 | 19.60 | 16.22 | |

| 11.0 | 25.43 | 12.05 | 7.29 | 6.37 | |

From Figure 5 and Table 4, it can be found that in the water solutions with pH 9.5 and 10.0, the addition of hydrazine increased the |Z|0.01 values of the carbon steel electrode, and would further increase with the hydrazine concentration. When 200 mg/L hydrazine was added to the water solutions at pH 9.5 and 10.0, the |Z|0.01 values of the carbon steel electrodes increased to 46.11 kΩ·cm2 (pH 9.5) and 25.90 kΩ·cm2 (pH 10.0), respectively. These values were 5.39 and 2.06 times greater than that in the water solution without hydrazine, and this result in a significant enhancement of the corrosion resistance of the carbon steel surface.

The addition of hydrazine significantly reduced the impedance of carbon steel electrodes in the water solutions at pH 10.5 and 11.0. At a hydrazine concentration of 200 mg/L, the |Z|0.01 values decreased to 16.22 kΩ·cm2 (pH 10.5) and 6.37 kΩ·cm2 (pH 11.0), which were 2.94 times and 3.99 times lower than those in solution without hydrazine. In the water solution with pH 11.0, the addition of hydrazine makes the decrease of the |Z|0.01 value more obvious than that in the solution with pH 10.5.

The above results display that hydrazine appears to have two completely different effects on the corrosion behavior of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions at different pH. Hydrazine exhibited corrosion inhibition in water solutions at pH 9.5 and 10.0, while it exhibited obvious corrosion promotion on carbon steel electrodes in water solutions at pH 10.5 and 11.0. The reasons for the above effects of hydrazine on the corrosion of carbon steel in solutions of different pH are analysed below in conjunction with the results of the polarization curve.

3.2.2 Analysis of polarization curves

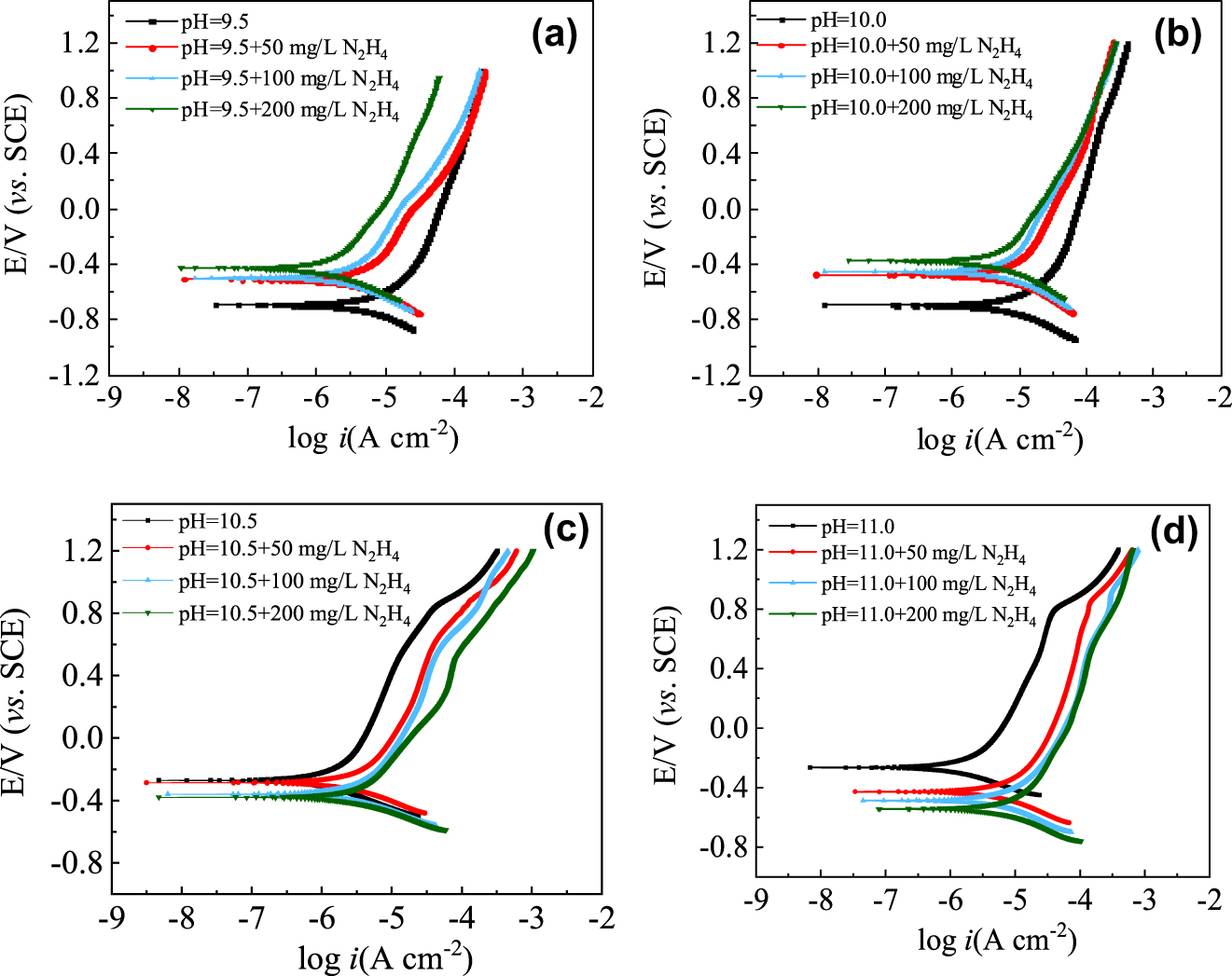

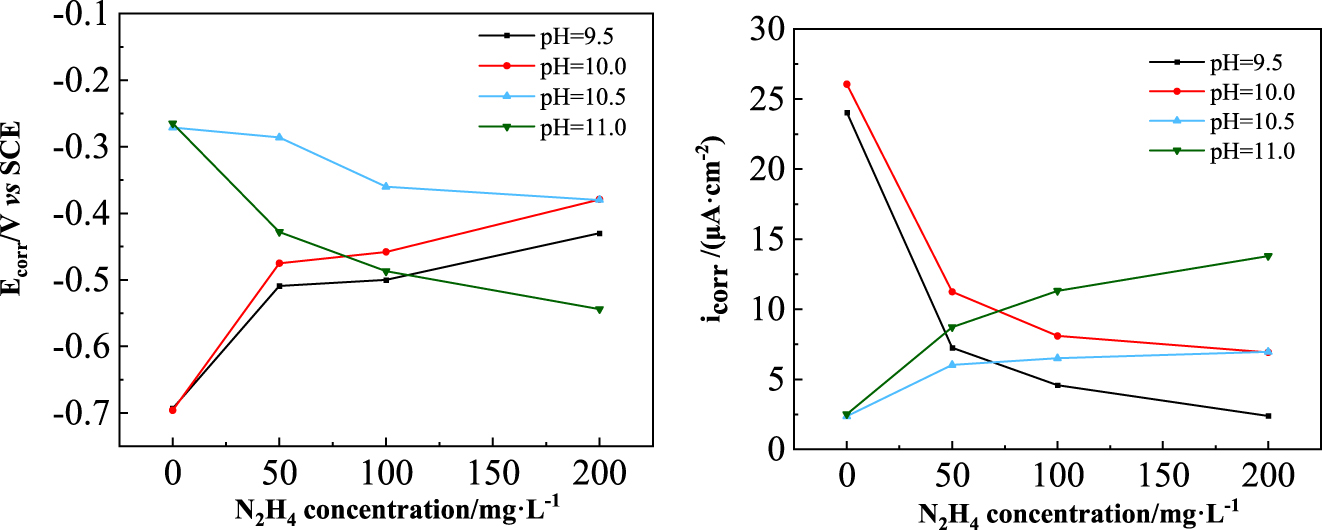

The potentiodynamic polarization curves of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions with different pH values and different concentrations of N2H4 were measured, and the results are shown in Figure 6. The change of corrosion potential and corrosion current density of carbon steel electrodes with hydrazine concentration are shown in Figure 7.

Polarization curves of carbon steel electrodes in water solutions with different pH values and different concentrations of hydrazine.

Change of corrosion potential and corrosion current density of carbon steel electrodes with hydrazine concentration.

Figures 6 and 7 show that in water solutions with pH 9.5 and 10.0, the Ecorr of the carbon steel moved positively and the icorr decreased with the addition of hydrazine, indicating that hydrazine mainly inhibited the anodic dissolution process of the carbon steel. Under the condition of constant pH, the higher the hydrazine concentration, the more positive the corrosion potential of carbon steel and the lower the corrosion current density, indicating a stronger anodic inhibition by hydrazine. Comparing the corrosion behavior of carbon steel in water solutions with pH 9.5 and 10.0, it was found that hydrazine inhibited the corrosion of carbon steel more strongly in water solutions at pH 9.5. The rise of pH leads to an increase of conductivity, which may weaken the corrosion inhibition of hydrazine.

In water solutions with pH 10.5 and 11.0, the Ecorr of the carbon steel moved negatively and the icorr increased with the addition of hydrazine, indicating that hydrazine promoted the anodic dissolution process of carbon steel at these pH values. When the pH of the water remained constant, the greater the hydrazine concentration, the more negative the corrosion potential of carbon steel and the higher the corrosion current density. Comparing the corrosion behavior of carbon steel in water solutions at pH 10.5 and 11.0, it was found that hydrazine had less promotion effect on the corrosion of carbon steel in water solution at pH 10.5.

Hydrazine is commonly used as an oxygen scavenger during boiler operation, and it is also commonly used as a corrosion inhibitor when the boiler is shutdown (such as used in the ammonia-hydrazine protection process). It is generally believed that the corrosion inhibition effects of hydrazine are mainly reflected in the following aspects:

Oxygen removal (Järvimäki et al. 2015; Karasawa et al. 2006; Kumar et al. 2016; Wada et al. 2007). Oxygen molecules are the most common depolarizers that promote metal corrosion. Hydrazine has strong reducibility and can react with oxygen molecules in water solution (Reaction (6)), thus decreasing the dissolved oxygen concentration in water and inhibiting the reduction reaction of oxygen, thereby reducing the corrosion rate of metals. However, it is believed that the reaction rate of hydrazine and oxygen is very slow at room temperature (Ershov and Mikhailova 1991; Falk 1998; Lowson 1977; Sunaryo 2016).

Passivation. Hydrazine can reduce the loose corrosion product Fe2O3 on carbon steel surface to a dense Fe3O4 oxide film (Reaction (7)), passivate the surface of carbon steel and reduce its corrosion rate (Jäppinen et al. 2021).

Adsorption. It is believed that hydrazine can be preferentially adsorbed on the anodic region of the carbon steel surface, thereby increasing the anodic dissolution resistance of carbon steel, making the corrosion potential shift positively and reduce the corrosion rate (Hassan et al. 1979; Takada et al. 2009).

Alternative anodic reaction. The hydrazine in water solution can act as a sacrificial anode to inhibit the anodic dissolution process of iron through the following reaction (Gouda and Sayed 1973; Gouda and Shater 1975).

The results in Figures 6 and 7 indicate that hydrazine played a completely different role in the corrosion of carbon steel in water solutions with different pH values. At lower pH (pH 9.5 and 10.0), hydrazine inhibited the corrosion of carbon steel, while at higher pH (pH 10.5 and 11.0), hydrazine promoted the corrosion of carbon steel. From the corrosion inhibition point of view, hydrazine reduced the corrosion current density of carbon steel while positively shifting its corrosion potential (corresponding to pH 9.5 and 10.0 in Figure 7). If the corrosion inhibition of hydrazine was due to the removal of dissolved oxygen, the reduction in dissolved oxygen concentration would lead to an increase in cathodic polarization of the corrosion system, resulting in a negative shift of the corrosion potential and a decrease in corrosion current density of the metal. Therefore, the corrosion inhibition of hydrazine here should not be caused by the oxygen removal effect of hydrazine. In addition, in the experiments of this paper, the carbon steel surface was sanded first and then exposed to the water solutions containing hydrazine, so the corrosion product Fe2O3 could not be formed on the carbon steel surface, and it was impossible for passivation reaction, Reaction (7), to occur.

Therefore, the corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions at pH 9.5 and 10.0 at room temperature should be due to its adsorption in the anodic region and its oxidation, Reaction (8) that occurs on the anode surface, which acts as a sacrificial anode for carbon steel to inhibit the anodic dissolution process of iron [Reaction (1)]. Figure 6a and b also show that the addition of hydrazine significantly reduced the anodic polarization current density of carbon steel electrodes, which may imply that the corrosion inhibition of hydrazine may be mainly due to its adsorption on the carbon steel surface. In contrast, in water solutions at pH 10.5 and 11.0, the results in Section 3.1 show that the carbon steel surface was passivated in hydrazine-free water solution. The results in Section 3.2 display that the passivation performance of the carbon steel decreased after the addition of hydrazine to the water. This should be because the adsorption of hydrazine hindered the adsorption of oxygen on the carbon steel surface, and the occurrence of Reaction (8) inhibited passivation Reaction (3), thus reducing the passivation performance of the carbon steel. That is, in water solutions with a higher pH, the presence of hydrazine may actually reduce the corrosion resistance of the carbon steel.

3.3 Corrosion morphology observation

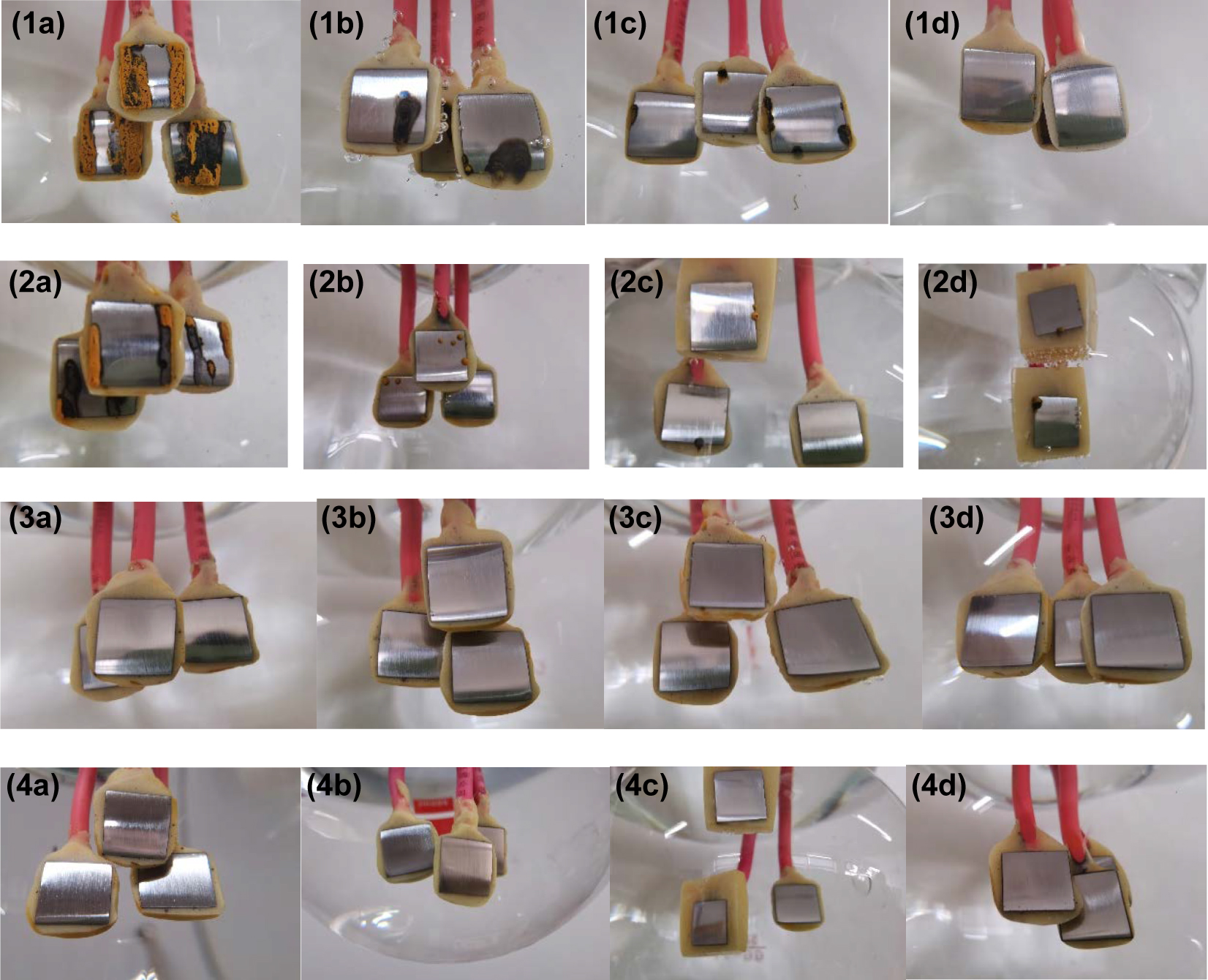

Figure 8 shows the corrosion morphologies of the carbon steel electrodes after immersion in water solutions with different pH values and different concentrations of hydrazine for 72 h.

Corrosion morphologies of the carbon steel electrodes after immersion in water solutions with different pH values and different concentrations of hydrazine for 72 h. pH values: (1) 9.5, (2) 10.0, (3) 10.5, and (4) 11.0. N2H4 concentration (mg/L): (a) 0, (b) 50, (c) 100, and (d) 200.

It can be observed that in water solutions at pH 9.5 and 10.0, the corrosion area on the carbon steel surface gradually reduced with the increase of hydrazine concentration. In the water solution with a hydrazine concentration of 200 mg/L, the carbon steel surface showed no obvious corrosion in the solution with pH 9.5, and it exhibited better corrosion resistance than that in solution with pH 10.0. When the pH was adjusted to 10.5 and 11.0, no obvious corrosion products were found on the surface as the carbon steel was in a passivated state in this pH range. However, according to the electrochemical results, the addition of hydrazine in the water solutions reduced the corrosion resistance of carbon steel, which may be related to the compactness and thickness of the passivation film formed in different solutions.

The above results exhibit that the carbon steel had the best corrosion resistance in the water solution containing 200 mg/L hydrazine at a pH of 9.5 and in a water solution without hydrazine at a pH of 10.5. The corrosion rates of carbon steel were similar in these two water solutions. These two conditions can be used as the best protection conditions for boiler shutdown protection by the ammonia-hydrazine method and the ammonia method, respectively. The above results also show that by adjusting the pH of the water solution to an appropriate range, carbon steel can also have a lower corrosion rate without using hydrazine.

4 Conclusions

The effect of hydrazine on the corrosion behavior of carbon steel was strongly related to the pH value of the water solution. In the water solution without hydrazine, when the pH was 9.5 and 10.0, the |Z|0.01 value of the carbon steel electrode was smaller and the corrosion current density was larger, the corrosion potential was more negative, and the metal surface appeared to have loose corrosion products. When the pH of the water rose from 10.0 to 10.5, the |Z|0.01 value of the carbon steel electrode increased by nearly 20 times and the corrosion current density also decreased significantly, while the corrosion potential shifted positively and the carbon steel electrode was passivated. After adding hydrazine to the water solutions with at pH 9.5 and 10.0, the |Z|0.01 value of the carbon steel electrode increased significantly with the increase of hydrazine concentration, the corrosion potential shifted positively, the corrosion current density decreased, and hydrazine exhibited better corrosion inhibition performance for carbon steel. It was possible that the adsorption of hydrazine on the anode surface and the oxidative substitution reaction of hydrazine inhibited the anodic dissolution process of carbon steel. The addition of hydrazine to the water solutions at pH 10.5 and 11.0 resulted in a significant decrease in the |Z|0.01 value for the carbon steel electrodes. This was accompanied by a negative shift in corrosion potential and an increase in corrosion current density, indicating that hydrazine inhibited the passivation of the carbon steel surface. This can be attributed to the adsorption of hydrazine on the anode surface and the oxidative substitution reaction of hydrazine which inhibits the passivation of the carbon steel surface. The carbon steel had the best corrosion resistance in a water solution containing 200 mg/L hydrazine at pH 9.5 and in a water solution without hydrazine at pH 10.5. By adjusting the pH value of the water solution to an appropriate range, the carbon steel can also have a lower corrosion rate without using hydrazine.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work was financially supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (grant no. 20ZR1421500) and Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (19DZ2271100).

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Ershov, B.G. and Mikhailova, T.L. (1991). A study by pulse radiolysis of the radiation-chemical transformation of aqueous solutions of hydrazine in the presence of oxygen. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. 40: 288–292, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00965417.Search in Google Scholar

Falk, I. (1998). Hydrazine and organic oxygen scavengers. Summary and evaluation of consequences. Technical Report SVF-642, Sammanstaellning och utvaerdering av konsekvenser vid anvaendning av hydrazin respektive organiska syrereduktionsmedel.Search in Google Scholar

Feng, Y., Zhou, G., and Cai, S. (1991). Explanation of high-frequency phase shift in ac impedance measurements for copper in low-conductivity media. Electrochim. Acta 36: 1093–1094, https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4686(91)85319-3.Search in Google Scholar

Fu, C., Li, Y., and Wang, Y.F. (2020). Microstructure and corrosion resistance of ERNiCrMo-13 and NiCrBSi coatings in simulated coal-fired boiler conditions: the effect of fly-ash composition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 399: 126134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.126134.Search in Google Scholar

Fu, C., Li, Y., and Wang, Y.F. (2021). Microstructure and corrosion resistance of NiCr-based coatings in simulated coal-fired boiler conditions. Oxid. Metals 95: 45–63, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11085-020-10016-5.Search in Google Scholar

Gouda, V.K. and Sayed, S.M. (1973). Corrosion inhibition of steel by hydrazine. Corrosion Sci. 13: 647–652, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-938x(73)80034-4.Search in Google Scholar

Gouda, V.K. and Shater, M.A. (1975). Corrosion inhibition of reinforcing steel by using hydrazine hydrate. Corrosion Sci. 15: 199–204, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-938x(75)80009-6.Search in Google Scholar

Hassan, S.M., Elawady, Y.A., Ahmed, A.I., and Baghlaf, A.O. (1979). Studies on the inhibition of aluminium dissolution by some hydrazine derivatives. Corrosion Sci. 19: 951–959, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-938x(79)80086-4.Search in Google Scholar

Jäppinen, E., Ikäläinen, T., Lindfors, F., Saario, T., Sipilä, K., Betova, I., and Bojinov, M. (2021). A comparative study of hydrazine alternatives in simulated steam generator conditions - oxygen reaction kinetics and interaction with carbon steel. Electrochim. Acta 369: 137697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2020.137697.Search in Google Scholar

Järvimäki, S., Saario, T., Sipilä, K., and Bojinov, M. (2015). Effect of hydrazine on general corrosion of carbon and low-alloyed steels in pressurized water reactor secondary side water. Nucl. Eng. Des. 295: 106–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2015.08.033.Search in Google Scholar

Karasawa, H., Ishida, K., Wada, Y., Endou, M., Nishino, Y., Aizawa, M., and Takiguchi, H. (2006). Hydrazine and hydrogen co-injection to mitigate stress corrosion cracking of structural materials in boiling water reactors. (III) Effects of adding hydrazine on Zircaloy2 corrosion. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 43: 1218–1223, https://doi.org/10.1080/18811248.2006.9711214.Search in Google Scholar

Kumar, P.S., Mohan, D., Chandran, S., Rajesh, P., Rangarajan, S., and Velmurugan, S. (2016). Evaluation of nitrogen containing reducing agents for the corrosion control of materials relevant to nuclear reactors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 187: 18–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2016.11.031.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, C., Lin, G., Sun, Y., Lu, J., Fang, J., Yu, C., and Sun, K. (2020). Effect of octadecylamine concentration on adsorption on carbon steel surface. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 52: 2394–2401, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2020.03.026.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Y., Fan, W., Zhang, X., and Wu, X. (2017). High-temperature corrosion properties of boiler steels under a simulated high-chlorine coal-firing atmosphere. Energy Fuels 31: 4391–4399, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b02755.Search in Google Scholar

Lowson, R.T. (1977). Electrochemical mechanism for the room temperature inhibition of corrosion of steel by hydrazine. British Corros 12: 175–179, https://doi.org/10.1179/bcj.1977.12.3.175.Search in Google Scholar

Matsumura, M. (2011). The possibility for formation of macro-cell corrosion in a liquid with low electrical conductivity. Mater. Corros. 62: 449–453, https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.200905573.Search in Google Scholar

Prifiharni, S., Royani, A., Triwardono, J., Priyotomo, G., and Sundjono (2020). Proceedings of the 3rd International Seminar on Metallurgy and Materials, April 22, 2020: corrosion rate of low carbon steel in simulated feed water for heat exchanger in ammonia plant. AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 2232. AIP Publishing, Tangerang Selatan, Indonesia, p. 20007.10.1063/5.0006768Search in Google Scholar

Revie, R.W. (2011). Uhlig’s corrosion handbook, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York.Search in Google Scholar

Sha, J.Y., Ge, H.H., Wan, C., Wang, L.T., Xie, S.Y., Meng, X.J., and Zhao, Y.Z. (2019). Corrosion inhibition behaviour of sodium dodecyl benzene sulphonate for brass in an Al2O3 nanofluid and simulated cooling water. Corros. Sci. 148: 123–133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.12.006.Search in Google Scholar

Standards China (2017). Guideline for lay-up of thermal power equipment in fossil plants (DL/T 956-2017). Technical Committee on Power Plant Chemistry of Standardization in Electric Power Industry, Beijing.Search in Google Scholar

Sunaryo, G.R. (2016). The effect of hydrazine addition on the formation of oxygen molecule by fast neutron radiolysis. KnE Energy 7: 155–162.10.18502/ken.v1i1.471Search in Google Scholar

Takada, S.T.M., Gotou, H., Mawatari, K., Ishihara, N., and Kai, R. (2009). Alternatives to hydrazine in water treatment at thermal power plants. Mitsubishi Heavy Indus. Tech. Rev. 46: 43.Search in Google Scholar

Vijay, N. and Velmathi, S. (2020). Near-infrared emitting probe for detection of nanomolar hydrazine in complete aqueous medium with realtime application in bioimaging and vapour phase hydrazine detection. ACS Sust. Chem. Eng. 8: 4457–4463, https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b07445.Search in Google Scholar

Wada, Y., Ishida, K., Tachibana, M., Aizawa, M., Fuse, M., Kadoi, E., and Takiguchi, H. (2007). Hydrazine and hydrogen co-injection to mitigate stress corrosion cracking of structural materials in boiling water reactors (IV) reaction mechanism and plant feasibility analysis. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 44: 607–622, https://doi.org/10.1080/18811248.2007.9711849.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, J., Wang, J., and Han, E.H. (2016). Influence of conductivity on corrosion behavior of 304 stainless steel in high temperature aqueous environment. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 32: 333–340, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2015.12.008.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Wang, M., and Tan, H. (2020). Formation of sulfide deposits and high-temperature corrosion behavior at fireside in a coal-fired boiler. Energy Fuels 34: 13849–13861, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02634.Search in Google Scholar

Xiong, X., Liu, X., Tan, H., and Deng, S. (2020). Investigation on high temperature corrosion of water-cooled wall tubes at a 300 MW boiler. J. Energy Inst. 93: 377–386, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joei.2019.02.003.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, X., Ding, Y., Li, Y., Yan, M., Cui, Y., and Sun, G. (2021). Dual-channel colorimetric fluorescent probe for determination of hydrazine and mercury ion. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 258: 119868, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2021.119868.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editor’s Note

- A demonstration of resilience

- Reviews

- Scanning electrochemical microscopy methods (SECM) and ion-selective microelectrodes for corrosion studies

- Corrosion inhibitors for AA6061 and AA6061-SiC composite in aggressive media: a review

- Original Articles

- Oxidation–reduction reactions and hydrogenation of steels of different structures in chloride-acetate solutions in the presence of iron sulfides

- The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: effect of immersion time and anti-corrosion activity of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution

- Corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions with different pH adjusted by ammonia

- Comparison of protective coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilanes and possibilities of spectroelectrochemical approaches for their investigation

- Corrosion behaviour OF HVOF deposited Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editor’s Note

- A demonstration of resilience

- Reviews

- Scanning electrochemical microscopy methods (SECM) and ion-selective microelectrodes for corrosion studies

- Corrosion inhibitors for AA6061 and AA6061-SiC composite in aggressive media: a review

- Original Articles

- Oxidation–reduction reactions and hydrogenation of steels of different structures in chloride-acetate solutions in the presence of iron sulfides

- The golden alloy Cu5Zn5Al1Sn: effect of immersion time and anti-corrosion activity of cysteine in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution

- Corrosion inhibition of hydrazine on carbon steel in water solutions with different pH adjusted by ammonia

- Comparison of protective coatings prepared from various trialkoxysilanes and possibilities of spectroelectrochemical approaches for their investigation

- Corrosion behaviour OF HVOF deposited Zn–Ni–Cu and Zn–Ni–Cu–TiB2 coatings on mild steel