Abstract

This article addresses the history of European colonialism during the age of imperialism in the late 19th and early 20th century from a transimperial perspective. It starts with the assumption that colonial history is all too often written along national lines that offer a limited perspective on events and circumstances. By contrast, this study emphasizes instances of exchange and mutual aid between two colonial powers, Germany and Italy, which shared a degree of inexperience in the conquest of overseas territories. The two countries did not experience the start of the construction of their respective colonial empires exclusively as a moment of competition, but also of mutual support in the face of similar dangers and common uncertainties. Among the many areas of analysis, the article focuses on the mobility of soldiers and the awarding of decorations across colonial borders, the diplomatic and scientific visits between the two imperial contexts, and the network of scholarly exchanges on different aspects of colonial governance. Further avenues of research may concern other areas of exchange and aid, as well as other empires.

The age of European imperialism at the turn of the 19th and 20th century is famously recognised as the phase in which Europe reached the apex of its political supremacy over territories and individuals in other regions of the world. Colonialism was a form of global governance with enormous and lasting consequences, both direct and indirect, on the social life of the populations involved. In the history of late modern century colonialism, the Berlin conference, convened by Bismarck and held from November 1884 to February 1885 in the capital city of the recently unified German Reich, was and still represents a key moment. Few images are as revealing of an era and a political program as the one that depicts the participants of that conference, gathered in a sumptuous room dominated by a large map of Africa towards which the interest of all participants was evidently directed. The conference served, under the pretext of humanitarian intentions, to offer a negotiating table to European countries interested in conquering territories on the African continent. In fact, at the time, every country aspired to take as much of Africa and the resources it seemed to be generously offering. Certainly, national antagonisms played a fundamental role in this partitioning operation and are an indisputable element in deciphering it as an historical process. However, taking them as an analytical starting point has contributed to dividing colonial history along strictly national lines. For too long, and too often, the echo of a national interpretation has resounded in historical research on European colonialism.

Traditionally, colonial history has been written as a national history; sometimes it was seen as a history on the margins of the national narrative, but still not outside the framework of one’s own nation and the perspective of the colonizing states. In recent times, the historiographical framework has become more complicated. A significant change has come with the increased interest for a new history of empires and within it for a practice of comparing colonial empires.[1] Especially as a consequence of the boom of global history, observations and analyses of colonial policies are carried out beyond the national paradigm and placed in dialogue with regional studies. Inquire into the similarities and differences between colonial empires and their policies has received major attention and produced thought-provoking contributions.[2] At the same time, comparisons with non-European colonial empires are also proving useful in overcoming interpretative schemes linked to the principle of European exceptionalism.[3] More and more, European colonialism in its different national experiences and developments is consciously conceived as a shared European phenomenon in world history.

This article, however, transcending national interpretations and arguing against comparativist approaches, seeks to go beyond colonial comparison, and does so by adopting a transimperial perspective on European colonial history. The basic assumption is that comparative histories can easily run the risk of reinforcing strictly national interpretations of colonialisms. In fact, some comparative works are little more than the sum of two case studies.[4] On the contrary, paying more attention to cooperation and exchange, alongside competition and antagonism, can change our view of circumstances and issues that were not specific to a single colony or colonial power, but were common and shared, quite often at the center of exchange and reciprocal support. The following pages are devoted precisely to cases of movements of people and ideas, of mutual aid and gazes with regard to two selected colonial empires in the bigger frame of European colonialism. They thus adopt a transimperial lens and embrace an approach that has proven fruitful in the last years.[5] Recent research has shown how useful a transimperial approach to the global history of colonialism is, whether it is applied to histories of colonial science, structure and practices of rule, violence and battles, medicine and so on.[6] The use of the terms transimperial and transcolonial in the following pages is intended to indicate the two levels of analysis for a study of this kind, one related more to the metropolis, the other more concerned with colonial and local dynamics.

In order to systematically circumscribe the analysis of European colonialism and to provide it with a concrete empirical basis, this essay will focus on the way in which certain issues related to the defence of the colonies, the military apparatus and, in a general sense, colonial structures of rule were at the centre of exchanges between two European colonial experiences, that of the Kingdom of Italy and that of Imperial Germany. Germany and Italy were constituted as nation-states in the second half of the 19th century just a few years apart and after a process of national unification that allowed for instructive comparative analyses. At the same time, both countries, newly unified, embraced the ambitious project of conquering overseas territories and, on the strength of an increasingly strong nationalist movement, to create a colonial empire. This simultaneous national and colonial development makes the joint study of these two cases within the European context particularly interesting, all the more so since both countries were moving on a terrain that was still new to them and could count on a background of colonial experience that was certainly less rich than that of other European countries, such as France or Great Britain. The comparative and intertwined historiography on the Italian and German cases in European history has a long and prestigious tradition, which has also impacted the imperial and colonial history of the two countries.[7] For instance, Patrick Bernhard’s studies, which have highlighted in an original way the influences of Italian colonial models on Nazi Germany’s practices of territorial governance in Eastern Europe, have become a point of reference in the global history of fascism.[8] However, it would be wrong to think that such dynamics of influences and exchanges were exclusive to the fascist period and specific to a political framework marked by common membership of the Axis.[9] The present essay seeks to extend the timeframe of this kind of analysis to the so-called liberal colonialism; it looks at specific areas in which German and Italian colonialism can be read through a transimperial lens. In doing so, it aims to rethink the singularity of fascist collaboration within the Axis and to see European colonialism in its various phases as marked by movements along transimperial lines.

Soldiers and Volunteers on the Move

In the study of Italian colonialism, military history has long represented a fruitful field of research. Alongside the history of military events in the strict sense, however, an interesting strand of research has matured over time that has related the wars and battles that occurred in colonial territories to the consequences they had on local societies and economies. See, for example, the case of the indigenous soldiers in the service of the Italian colonial state, commonly called ascari. The important research of Uoldelul Chelati Dirar, Alessandro Volterra and Massimo Zaccaria has demonstrated not only the military contribution of the ascari in the various Italian military campaigns, but above all the impact that these experiences of military life had, in many respects, on the lives of these colonial subjects and their families.[10] Participating in a military campaign meant entering a different labour market, which was the military one, and taking on a different role in colonial society; from an intimate and personal point of view, it also meant being away from home and experiencing, in most cases, a cross-border mobility uncommon for a colonial subject of the time.[11] The mobility of troops within the empire, specifically between the Horn of Africa and North Africa, served to give substance to a new reading of Italian colonialism as a „connected system“.[12] This interpretation intends to emphasise the connections between the colonies and overcome an analysis of Italian colonialism that focuses too much on the socio-political developments of a single colonial context. For a better understanding of the complex historical phenomenon of Italian colonialism, it is therefore useful to bear in mind the high degree of inter-imperial connections with administrative and military careers, for example, that normally developed in various colonies.

A transimperial analytical perspective can also be added to the social and cultural study of military history. To what extent were military events a matter restricted to the decision-making domain of the individual colonial empire and how much were they also at the centre of a network of exchanges, aid and mutual suspicion? The stories presented below may provide some food for thought in this regard, such as those regarding the battle of Adua of 1st March 1896, during which the army of the Ethiopian Empire defeated the troops of the Kingdom of Italy consisting of Italian soldiers and local ascari, mainly from Italian Eritrea.[13] Beyond its military significance and political implications, this battle in particular had an important symbolic value: one of the European countries engaged in the conquest and colonization of Africa was defeated by an African country and experienced what many in Italy and Europe deemed an heavy humiliation. Italian colonial ambitions were temporarily curtailed because of the battle of Adua while the name of this old Ethiopian city was later repeatedly evoked and instrumentalized to legitimize Fascist Italy’s aggression against Ethiopia in 1935.

The battle of Adua came at the end of a military campaign in which the fortunes of the Italians and the Ethiopians alternated. These military events were closely followed by public opinion and, above all, by nationalist and colonialist circles in Italy and abroad. In fact, these years were marked by a significant emigration of thousands of Italians seeking their fortune beyond the Alps and overseas, creating large Italian communities throughout the world. It is therefore not surprising that in January 1896, when Italy was fully committed to an expansion project in northern Ethiopia, the Italian Charity Society, during a special meeting in Berlin, sent its greetings and best wishes to the „brothers, brave soldiers of Italy who fought and continue to fight heroically in Africa for the fatherland“.[14] In fact, Italian colonial expansion enjoyed widespread support among Italians abroad. While this may not be surprising, it is interesting to note that initiatives in support of the Italian military campaign also came from German citizens. On the eve of the battle of Adua, in fact, a group of German citizens in the city of Cologne, a kind of Italophile circle, decided to set up a local committee to promote donations for the Italian Red Cross in Africa.[15]

Moreover, German newspapers and magazines reported extensively on the military events involving Italian troops in the Horn of Africa, providing daily news from the field. In general, colonial military issues filled the newspapers of the time.[16] About a month later, a dispatch from the Italian embassy in Berlin, dated 17 March 1896, noted that a number of German soldiers, some of whom were in service while others were on leave, along with some ordinary men had expressed a desire to join the Italian army in Africa. Although the reasons for these expressions of voluntarism are not mentioned, it is possible to imagine that these would-be volunteers wanted to commit themselves to assisting a European country engaged, just like the German Empire at the time, in a similar colonizing project.[17] They were also members of a defensive alliance known as the Triple Alliance, along with Austria-Hungary. However, the Italian response was not favorable to the German offer. From the Ministry of War, it was emphasised that the first condition for enrolment in the Italian army was to have Italian citizenship; secondly, it was pointed out that the army was sufficiently capable of dealing with ongoing military operations.[18] With these arguments, the Italian authorities clearly declined the German citizens’ offer. The episode is intriguing because it sheds light on several aspects of military cooperation between colonial powers, both at the level of government and at the level of citizens. It is likely that the Germans who intended to volunteer for the Kingdom of Italy’s ‚African campaign‘ felt empathy for the humiliation suffered by Italy as a European power, knowing after all that a similar fate could also befall Germany and its colonies. Perhaps one can go so far as to speak of a form of racial solidarity between European countries in the face of the risks to which they were commonly exposed in pursuing a colonial project and confronting peoples deemed to lack civilization. At the same time, however, the episode also highlights a certain form of antagonism between the colonial powers. The letter from the Minister of War combined a polite refusal with a firm intention to defend the honor of Italy. The honor of the army was to be understood at this time as the honor of the nation, because the defeat at Adua had damaged both the image of the army and that of the nation as a whole. This was true for Italians in the motherland, but it was even more true for Italians abroad, given the stir that the battle of Adua had caused in world public opinion.

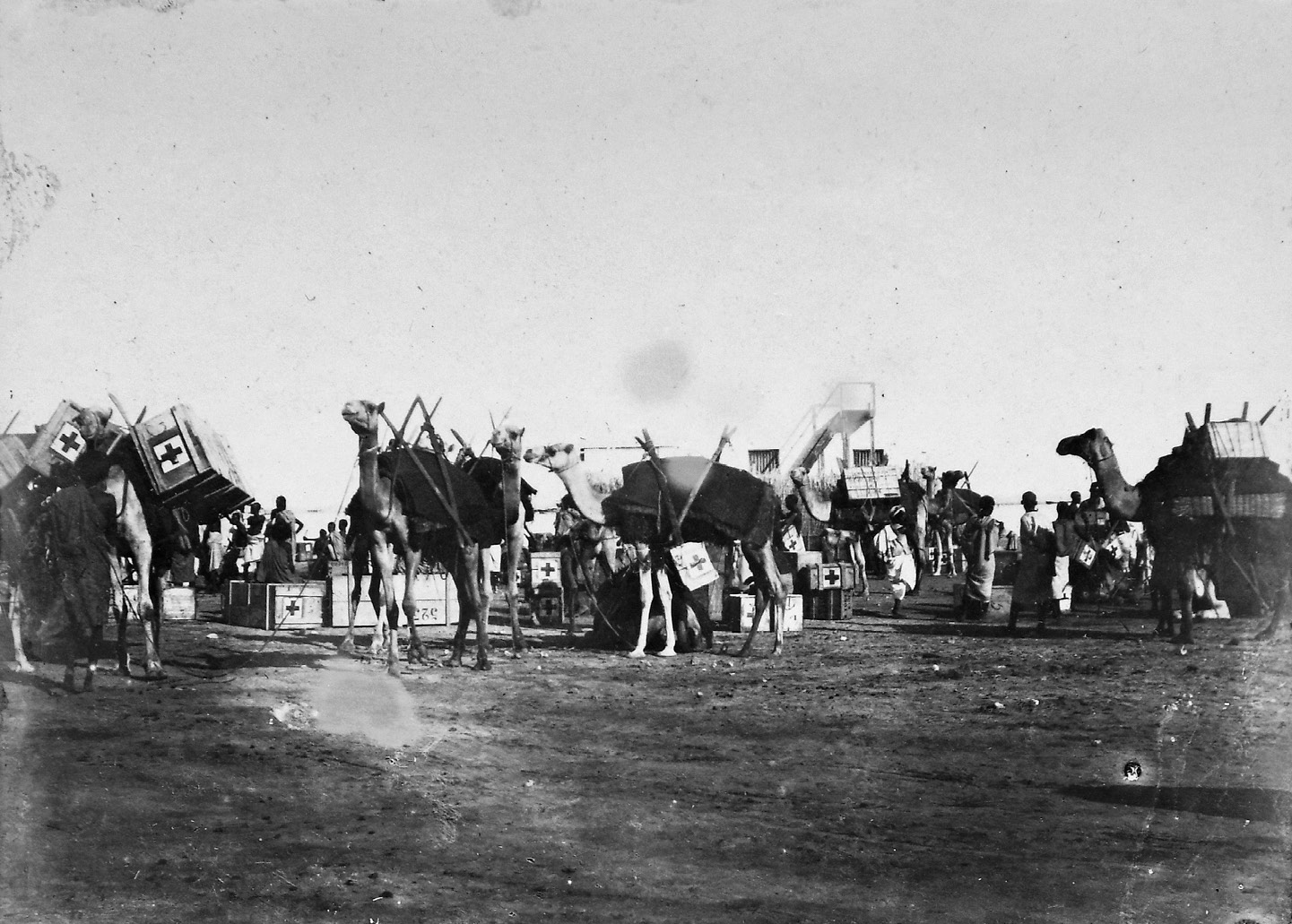

Red Cross Caravan (1896).

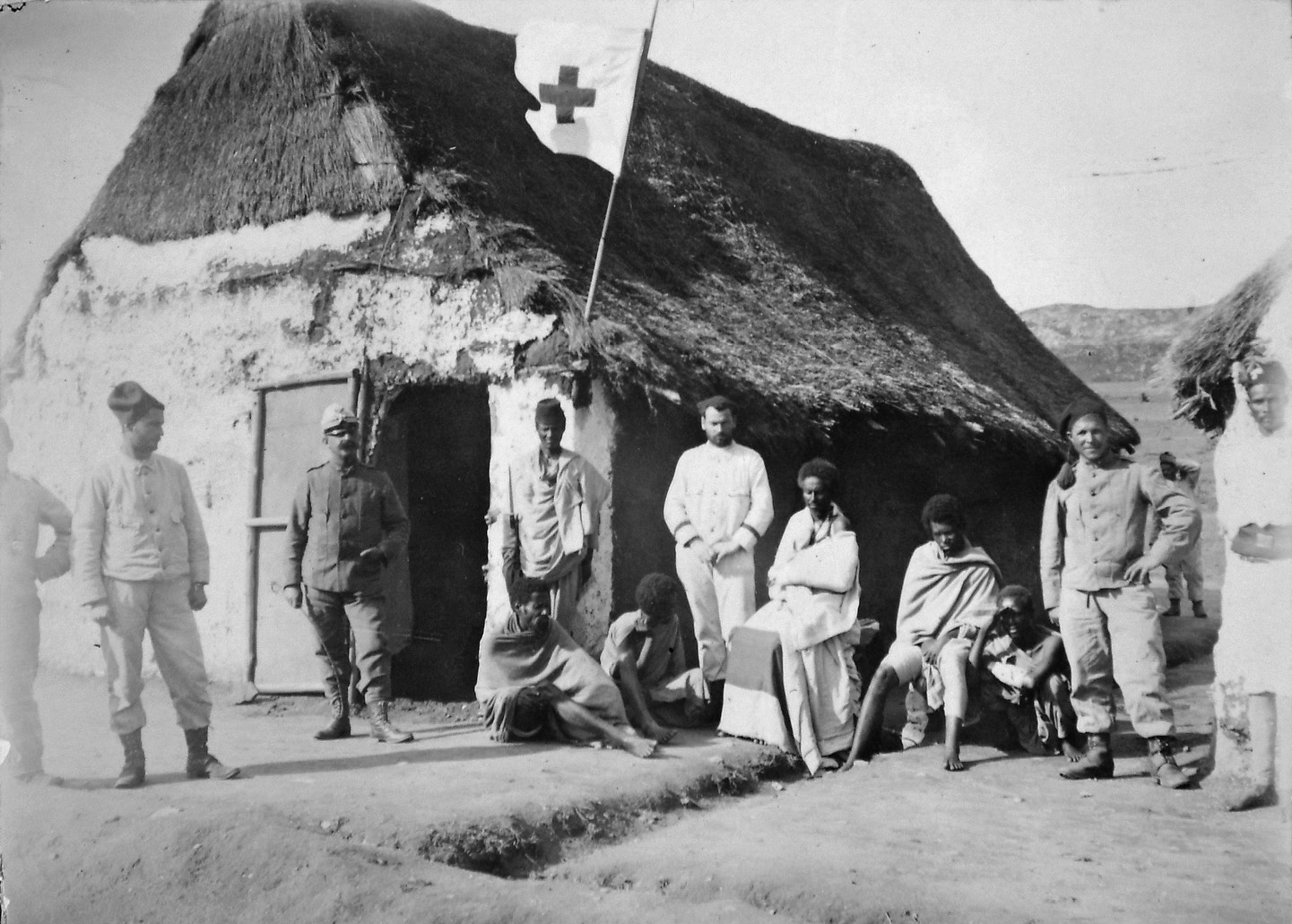

Wounded Italian Soldiers and Natives in Front of a Red Cross Hut (1896).

Transcolonial Aid and Transimperial Decorations

The anticolonial war that developed in southern German East Africa in 1905 and is known as the Maji Maji War is another episode in colonial military history that not only destabilized a colonial power but also had a global resonance and caused concern and a sense of powerlessness among the colonizers.[19] Colonial archives preserve abundant evidence of the circulation of information about this war and other anti-colonial uprisings. In general, for the colonial powers the fear of insurrections and uprisings against colonial rule was a common occurrence. The exchange of information and aid in this field therefore appeared particularly important.[20] This was certainly true for two imperial players both engaged in East Africa like Germany and Italy. For instance, the Italian embassy in Berlin did not fail to inform the Italian authorities of the ongoing uprising in the German East African colony which, according to a dispatch of August 1905, seemed all but quelled.[21] The same dispatch also referred to another uprising, this time in South West Africa, which the German government had downplayed and which was beginning to worry the German colonial authorities. However, this exchange of information was not limited to an intangible dimension but developed into various forms of mutual assistance and transcolonial cooperation, that a purely comparative analysis could not adequately highlight. The colonial government in German East Africa recruited soldiers from other colonies to provide quick relief in military operations. Soldiers also came from Italian Colony of Eritrea, which after all was not geographically very far from the German colony in Eastern Africa.[22] On 24 August 1905, Governor Ferdinando Martini (in office from 1897 to 1907) noted in his diary, published posthumously, the text of a communication he had received from Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni: the German government asked to enlist „for the German colony … two hundred Dankali (Afar people) for three years“ („per la colonia orientale tedesca … duecento Dancali per tre anni“). „I think it is very possible“ („Lo credo possibilissimo“) is how the governor of Eritrea closed the note in his diary.[23] Little is known about these ascari who went from the Italian Colony of Eritrea to German East Africa. One of them, Mohammed Hamedu, settled in the German colony and died of pneumonia in 1907 in Iringa: the colonial subject’s wife was planning to file for divorce because she had been abandoned by her husband and asked the administration in Eritrea to gather information about him. The diplomatic correspondence between the governors of Italian Eritrea and German East Africa refers to this exchange of information.[24] Historian M’hamed Oualdi masterfully showed the potential of a microhistory from below of a slave biography written in a transimperial perspective.[25] Similarly, a bottom-up study of the transimperial biographies of ascari engaged on various colonial fronts would add a new analytical dimension to the military and social history of European colonialism beyond national patterns.

However, trans-colonial support could also take other forms. Later, in view of the support provided in 1905, the German government awarded various decorations and honors to civil servants and military officers serving in Eritrea who had helped in the recruitment of colonial troops for German East Africa. Governor Martini himself, who greatly appreciated the outward manifestations and lavish rituals of colonial power, showed great appreciation for the gesture of the transalpine government.[26] The contemporary documentation of the colonial administration, now in the Historical Diplomatic Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation in Rome, preserves the document produced by the German embassy in Rome with a detailed list of the different types of decorations and their recipients[27] and, at the same time, the documents proving the receipt of the honors.

A careful study of decorations in the imperial sphere could provide insights into how transimperial solidarity and support operated. In the same correspondence mentioned above, Ferdinando Martini wrote about other similar decorations from the German government. These, bestowed upon both civil and military officials of the Colony of Eritrea, were an expression of gratitude on the German side towards the Italian colonial personnel who had assisted members of a German scientific-diplomatic mission in Ethiopia in 1906. Specifically, it was the mission led by Friedrich Rosen, an orientalist and diplomat (in 1921 for a few months also foreign minister), to whom Emperor Wilhelm II had entrusted the important task of strengthening friendship and trade relations between the German and the Ethiopian Empire.[28]

Not infrequently, diplomatic missions of this kind, in order not to arouse too much suspicion in international politics, combined their diplomatic activities with scientific fieldwork.[29] Felix Rosen, brother of Friedrich, a botanist from the University of Breslau/Wrocław, also took part in the aforementioned mission and later published a detailed account of his expedition to the Horn of Africa.[30] Of the mission and its members, but especially of its leader, Friedrich Rosen, Martini wrote in his diary that he seemed „some kind of very nice athlete. … keen observer, diligent and subtle reasoner. He is very flattered by the reception given to him and his companions by the Government of the Colony“ („una specie di atleta simpaticissimo. … osservatore acuto, diligente e ragionatore sottile. Si dimostra molto lusingato dell’accoglienza fatta dal Governo della Colonia a lui ed ai compagni suoi“).[31] While at the official lunch, attended by the colonial authorities, an exchange of courtesies took place between the governor of the colony and the head of the mission, the gratitude towards the Italian colony was also concretely manifested with a gift, consisting of some tents, in return for the helpfulness and kindness encountered.[32]

Addis Ababa. Arrival of the German Mission von Rosen (1906).

The history of decorations awarded to personnel serving in Eritrea by the German government, which could be described as a ‚minor diplomatic history‘ and could also be studied through the lens of the history of materiality, certainly demonstrates the existence of a network of relations and exchanges on several levels between the two colonial powers. These relations and exchanges could range from military assistance in times of crisis, as in the form of trans-colonial conscription, to logistical support to a scientific-diplomatic mission of another colonial power. The presented histories of military assistance and decorations also provide evidence that relations between colonial powers were not only marked by antagonism but also by mutual support and acknowledgment.

Visits and Travels across Colonial Borders

Mobility beyond the colonial borders and thus on a transimperial scale, however, did not only concern mobilisation for war and the sending of soldiers from one colony to another. The civil dimension, both within and outside colonial institutions, equally deserves to become the object of an entangled historical analysis of European colonialism. Traditionally, especially for the medieval and modern age, visits by sovereigns and court representatives have represented an important case for political, but also social and cultural history. In the meantime, the interest in meetings between sovereigns is also becoming increasingly important in contemporary history, and this also in a global perspective, as David Motadel’s recent study shows.[33] Visits by sovereigns and prominent politicians were accompanied by processions and parades, and became instruments and spectacles of power themselves. This was certainly also true in the colonial context. Michael Pesek in his analysis of colonial power in German East Africa as a sum of „Inseln von Herrschaft“ highlights the peregrinating nature of much of this power.[34] It is well known that Governor Ferdinand Martini also conducted long and thorough visits to the various regions of the Colony of Eritrea during his period of rule. In addition to this internal political dimension of colonial visits, the function of transcolonial visits, e. g. visits by administrators or diplomats between one colony and another of different empires, remains to be further studied. The following examples point to a new avenue of transimperial analysis.

In April 1897, Silvio Marvasi, the regent of the consulate in Zanzibar, departed the island in the Indian Ocean and made a brief visit to Dar es Salaam, the capital city of German East Africa, before reporting on it in a detailed account to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[35] The latter had returned a courtesy visit to the governor, Eduard von Liebert (in office from 1896 to 1901). Beyond the rituality of the prose, one can see a clear interest on the part of the author in reporting those details concerning the administration and state of the colony that might appear of interest to the Italian ministry, at that time still fully responsible for colonial affairs (the Ministry of Colonies was only founded in 1912, until then all matters concerning the colonies were the responsibility of the Central Directorate of Colonial Affairs of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs). While some of Marvasi’s impressions concerned the political situation and diplomatic relations – for example, he reported on the widespread anti-English sentiment on the German side – for the most part, the report described economic and social life in the colony. The city appeared particularly orderly and clean, which, especially in the indigenous part, amazed the visitor, who recognised in this a success of the colonial administration, which had apparently succeeded in forcing each person to clean the stretch of street in front of his or her house. He expressed admiration at the fact that the colonial staff had excellent knowledge of the Swahili language, the study of which was required at home for those wishing to pursue a colonial career. However, Marvasi’s report also touched on critical aspects: while the colony’s governor had complained about the high costs for the government to maintain a colony that was growing but still in need of substantial resources from the motherland, the German consul in Zanzibar had confessed to him much lower figures, perhaps in order not to admit that the colony was developing too slowly. Indeed, in all colonial empires, the performance of and expenditure on the colonies was a major topic of political and public debate. The report of the consul is a useful source and evidence of the exchange on topics about colonial administration and policy between two colonising countries in East Africa. The author himself wrote that he had also visited „to get an idea of that colony in order to report to Your Excellency“ („per avere un’idea di quella colonia per poterne rapportare all’E. V.“). Only a year or so later, the new Italian consul in Zanzibar, Giulio Pestalozza, drew up a detailed 18-page report on his recent visit to Dar es Salaam, in which he reported on topics ranging from crops to health facilities to railways and the colonial budget. The report, directed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was then forwarded by it to Governor Martini for information.[36]

The transcolonial visits also served to gather first-hand information about more or less large-scale infrastructure projects underway in the various colonial territories. At the beginning of 1911, the Italian consul in Zanzibar, Corsi visited the German East African colony. At the end of his visit, he sent the foreign minister a report on railway construction in the German colony, in particular the central railway to Tabora, which he had visited in its entirety. Because the subject was also of interest to the Italian colonies, he sent the same report to the governments of Eritrea and Somalia.[37] At the end of the visit, he proposed to have some national honours conferred on the senior officials of that colony who had been particularly courteous and helpful to the Italian diplomat. This gesture would not only have helped to consolidate relations between the two colonial powers, but would also, from a more utilitarian point of view, have benefited Italian emigrants in the German colony.[38]

However, the visits presented in the examples above were not the only instances of mobility of civilians between one colony and another of different empires. Other interesting examples of reciprocal views and evaluations come from travel accounts written by scholars, travellers and adventurers. Botanist Rosen’s account of his experience as a member of the above-mentioned scientific-diplomatic mission to Eritrea/Ethiopia was far from an isolated publication. It was common for scientists and explorers to describe their study trips, not limiting themselves to scientific matters but also adding personal impressions. The Horn of Africa saw many scholars and explorers treading its surfaces, coming from Germany or other German-speaking areas.[39] One case worth mentioning is that of the botanist and ethnologist Georg August Schweinfurth who studied and explored Northeast Africa and wrote extensively about the region, and who was at the same time also active in German colonial politics and a member of the Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft.[40] His visit to Italian Eritrea, in the years shortly after its foundation, was the subject of a short booklet in 1894 „Il mio recente viaggio col Dott. Max Schoeller nell’Eritrea italiana“, that had already been published in the „Bollettino della Società commerciale in Africa“.[41] However, other titles also refer to his frequentation of Eritrea in those years, some of them in Italian, proving the interest in Italy.[42]

Impressions of exotic journeys also emerged from the pens of travelers, missionaries, journalists – female voices are rare – who travelled beyond the borders of Europe for various reasons and then recounted their adventures. The comparative mode, implicit or explicit, is prominent in these writings because the trajectories of the journeys did not necessarily follow national directions. This kind of writing was also often disseminated through the colonial press, e. g. pamphlets, books and newspapers printed by associations and circles supporting colonialism: material that represents an invaluable source for a transimperial study of colonialisms. The colonial journals always reserved ample space, often fixed columns, for updates and in-depth studies on the colonies of the other powers. A systematic study of this production in the German-Italian sphere would be of great interest. Linked to this cultural production, the numerous colonial conferences and congresses are a further essential object of study for a trans-imperial analysis of colonialisms. The role played by international conferences on a wide variety of colonial topics must always be emphasised to demonstrate the strong degree of exchange that existed between scientists, politicians and lobbyists of various kinds on a transnational level.[43] Let us turn now to some examples of exchanges that touched on essential themes of administrative practice and colonial governance in the German-Italian transimperial space.

Colonial Rule and Transimperial Exchange

As well as people, ideas and models of government moved from one colony to another, from one empire to another. Taking a transimperial perspective can also be helpful for a better understanding of colonial governance. Colonial policy decisions and administrative practices on the ground had national orientations no less than they did in a transimperial setting. Recent historiography has shown that the production of colonial knowledge, and the circulation of information and knowledge between empires at multiple levels, is closely linked to the establishment and maintenance of asymmetrical power relations – and even to the perpetuation of this state of affairs even after the end of colonial rule.[44] This is less visible to the comparative gaze.

In general, colonial powers observed each other and carefully studied the colonial laws and policies adopted in other colonies.[45] From the time of the partition of Africa by Europe, translations of the legislative bodies of other countries began to be published in large numbers along with general works on the administrative structure of their colonial empires. There was a widespread transnational interest in colonial science. Official publications always reserved some space for an up-to-date analysis of the policies and laws of other colonies. „Crediamo utile pei lettori, che si interessano all’importante quistione dell’ordinamento politico-giudiziario indigeno, pubblicare, tradotto in italiano, l’atto del Cancelliere dell’Impero Germanico, relativo alle colonie dell’Africa Orientale, di Camerun e di Togo, trattandosi di uno degli ordinamenti più recenti e più lodati“ with these words, in July 1903, the „Bullettino Ufficiale della Colonia Eritrea“, the official organ of the colonial government in Eritrea, introduced the Italian translation of the German colonial code.[46] At the time, the Italian colony was on the verge of receiving a new legal system, in fact it could be said that a veritable legal laboratory was being set up for the colony: it is not surprising that there was this focus on German colonial legislation, but a transimperial analysis of this codification work remains to be written.[47]

Along with and related to criminal law and justice, the topic of the legal status of colonial inhabitants was one of the central topics of political and academic debate. While this was true of all colonial empires of the time, it must be emphasised that for Germany and Italy the debate on citizenship in the colonies was of particular importance. In fact, it took place in parallel with the formulation of the new citizenship law, which ended with the promulgation of the two new citizenship laws, in the Kingdom of Italy in 1912 and in the German Empire in 1913.[48] The application of racial parameters for the exclusion from metropolitan citizenship of those colonial subjects not considered ‚civilised‘ enough from a European point of view occurred at a time when the notion of formal state membership and organic nationhood were overlapping in both countries.[49] Within this legislative production on citizenship, which covered both metropolitan and colonial territories, it is possible to trace evidence of a lively exchange between Germany and Italy, which was part of a wider network of confrontations between the European colonial powers. As early as 1889, the Kingdom of Italy asked the German consulate (as well as the French, British and Spanish consulates) for information on the legal status of the indigenous population in its colonies.[50] As a new and inexperienced player in colonial affairs, the Kingdom of Italy probably felt it was particularly important to obtain information from other colonial powers.

In the Colony of Eritrea, the issue of citizenship was officially regulated for the first time in 1908.[51] The legal status of the inhabitants of the colony was the subject of Article 2 of the Judicial Ordinance. The history of this article, and thus of the definition of subjection as a legal status, began when the commission of jurists in charge wrote the Civil Code for the Colony of Eritrea, the product of the above-mentioned codification work. Despite the failure of the colonial codification project, mainly due to its over-ambition and impracticality, it should be seen as an important expression of colonial scholarship. It had a not insignificant influence, for example, in the field of jurisprudence (colonial judges were obliged to take the codes into account when judging cases and writing judgements); but it also attracted international interest. A message from the German Embassy in Rome reported precisely the news in the Official „Bulletin of the Colony of Eritrea“ that its Criminal Code could be purchased from the chancellery of the Court in Asmara. The same embassy then asked the Italian colonial authorities to send a copy of the code to Berlin, which was done, as confirmed by a diplomatic exchange of November 1908.[52]

In the opposite direction, the Italian authorities inquired about the regulation of citizenship in the German colonies. In 1912, the Italian Embassy in Berlin sent a detailed reply to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which had received a request from the Civil Affairs Office of the colonial government in Eritrea concerning the regulation of citizenship in the German Empire. The reply was accompanied by a copy of the „Reichs-Gesetzblatt“, the official gazette of the Reich, which published the text of the Schutzgebietsgesetz of 1900, the basic law of all German colonies.[53] Only a few years earlier, the same embassy in Berlin had replied to a similar request for information, but this time on the complex subject of ‚intertwined‘ citizenship relations between German East Africa and the Sultanate of Zanzibar, a British protectorate.[54]

Diplomatic exchanges of this kind can be found in all European colonial archives. Viewing them not just as serial bureaucratic practices, but as channels of communication and information between international actors, can help to better understand the deeply interconnected nature of European colonialism. In the cases of Germany and Italy, however, this kind of exchange could have played a more important role. The very lack of experience of the two countries, which entered the colonial arena with a certain delay compared to other European powers – a delay that is also seen as the reason for a particularly rich and significant production in the field of colonial legislation[55] – suggests that the colonial offices in Germany and Italy considered the parallel experiences of the two countries to be similar and worthy of a cross-examination.

Another example of diplomatic exchange of information is related to the marriage ban enacted in the German colonies at the beginning of the 20th century, a ban that generated a lively debate in the German Empire. In the beginning there was the decree of September 1905 prohibiting marital unions between ‚whites‘ and ‚natives‘ in German South West Africa, which was followed by a similar decree for German East Africa in 1906. In 1912, a marriage ban similar to those promulgated in African colonies was issued by the governor of Samoa, Erich Schultz-Ewerth (in office from 1912 to 1914) for the Pacific Ocean colony. The latter decree, however, had been ordered by the director of the Reichskolonialamt, the German Minister of Colonies, Wilhelm Solf, who had previously been governor of the colony Samoa. The question of marriage between German citizens and the inhabitants of the colonies, who were denied metropolitan citizenship, was central to the related question of the legal status of their offspring. The debate on the marriage ban, which involved a large part of public opinion and led to animated speeches in the Reichstag in the spring of 1912, was particularly heated: no other country at the time had seen such an obsessive debate on these issues. However, it aroused great interest in other European countries, which followed it closely. The Italian Ministry of Colonial Affairs requested a transcript of the parliamentary debate from the Italian embassy in Berlin, pointing out that the issue could also be of interest to the Italian colonies.[56] The regulation of family relations with regard to citizenship remained an open question even in the Italian colonies where concubinage was widespread and so-called meticci were a controversial political issue. As is well known, measures to prohibit intermarriage in the Italian colonial empire were not introduced until the 1930s, when, after the Fascist occupation of Ethiopia and the unification of the possessions in a single administrative unit in the Horn of Africa called Italian East Africa, the preservation of the racial prestige became the real ideological driving force behind Italian colonial legislation.[57] The extent to which forms of ideological continuity and transimperial exchange can be identified in this area is a question worthy of further study.

Conclusions

The examples presented above attempt to narrate a more connected and intertwined colonial history of Germany and Italy than hitherto imagined. Other examples could serve to examine other colonial empires in Africa and Asia, since similar mechanisms of entanglement were not exclusive to the German and Italian cases. The British, Japanese and Portuguese empires certainly faced similar dynamics. European colonialism was characterised by different and separate trajectories, with specific national and often deeply nationalistic traits. This essay has not sought to deny this evidence. However, it sought to broaden the interpretation of European colonialism by highlighting points of contact and exchanges between colonial powers on different levels. Soldiers and volunteers ready to intervene in another colony’s war fronts show that European colonialism was not just about competition. Decorations could be offered by one colonial power to another, as long as a civilizing political project was shared with regard to populations deemed inferior. To what extent diplomatic exchanges and administrative confrontations could really have influenced the policies adopted in individual colonies is a question that deserves more attention than can be reserved here. Certainly, however, they show that the subject of colony government was discussed in a much broader arena than the strictly national one. This is also demonstrated by the high international degree of exchanges and comparisons on the subject by jurists and politicians. New research on Italian and German colonialism could follow the indicated tracks and take others, possibly paying more attention to the local populations of the colonies and analysing their ability to counterbalance the actions of the colonial governments, to exploit the grey zones that could be created in the transcolonial space and to negotiate their agency at the transimperial level. All this can serve to offer a renewed understanding of European colonialism, and of Germany and Italy in it.

Sources of Figures

Fig. 1: Biblioteca nazionale centrale di Roma, Fototeca IsIAO. Album 302.

Fig. 2: Biblioteca nazionale centrale di Roma, Fototeca IsIAO. Album 26.

Figs. 3–4: Biblioteca nazionale centrale di Roma, Fototeca IsIAO. Raccolta Bertolani, 14/4.

The author would like to thank Christian Methfessel, Maria Framke, Ned Richardson-Little and Florian Wagner for their comments on an earlier version of this essay that appeared on the Transimperial History Network blog. He is grateful to Dónal Hassett for further comments. Work on the new version of the article was made possible by the ERC StG COLVET Ex-Soldiers of Empire: Colonial Veterancy in the Interwar World (Grant Agreement No. 101115749).

© 2025 bei den Autorinnen und den Autoren, publiziert von De Gruyter.

Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitung 4.0 International Lizenz.

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Jahresbericht des DHI Rom 2024

- Themenschwerpunkt L’Impero e le sue narrazioni nel pieno e tardo medioevo (XIII–XIV sec.), herausgegeben von Caterina Cappuccio

- L’Impero e le sue narrazioni nel pieno e tardo medioevo (XIII–XIV sec.)

- Electione de eo canonice celebrata

- Un Impero vacante? La signoria sovralocale di Oberto Pelavicino in Lombardia tra idealità imperiale e città (1249–1259)

- Un regno senza impero?

- Narrazione e percezione dell’impero nella cronachistica

- Artikel

- Building an Aristocratic Identity in Medieval Italy

- Memorie della Chiesa di Molfetta

- „Per fuoco e per estimo“

- Fonti e approcci sulla fiscalità pontificia per la Basilicata del XIV secolo

- La comunità tedesca a L’Aquila tra i secoli XV–XVI

- Whose Bishop/Who’s the Bishop?

- Si in evidentem: Pacht von Kirchengut über die Pönitentiarie

- Rhetorical vs. Historical Discourse?

- Ottavio Villani – ein Gegner der päpstlichen Politik im Dreißigjährigen Krieg

- Italian and German Colonialism beyond Comparison

- Geleitwort zum Beitrag „Gewaltlust“ von Habbo Knoch

- Gewaltlust

- Forum

- Der Gastronationalismus und Alberto Grandis Thesen – oder: Zur Prägekraft der italienischen Küche

- Tagungen des Instituts

- I monasteri di Subiaco e Farfa come crocevia monastico-culturale nei secoli XV e XVI

- Von den NS-Tätern sprechen, der Opfer gedenken. Perspektiven einer deutsch-italienischen Erinnerung zwischen Forschung und Vermittlung

- Circolo Medievistico Romano

- Circolo Medievistico Romano 2024

- Nachrufe

- Cosimo Damiano Fonseca (1932–2025)

- Dieter Girgensohn (1934–2025)

- Gerhard Müller 1929–2024

- Rezensionen

- Verzeichnis der Rezensionen

- Leitrezensionen

- Tra reti politiche e prassi documentarie

- Una rete di persone

- Ein weiteres langes „langes Jahrhundert“?

- Rezensionen

- Verzeichnis der Rezensent*innen

- Register der in den Rezensionen genannten Autor*innen

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Jahresbericht des DHI Rom 2024

- Themenschwerpunkt L’Impero e le sue narrazioni nel pieno e tardo medioevo (XIII–XIV sec.), herausgegeben von Caterina Cappuccio

- L’Impero e le sue narrazioni nel pieno e tardo medioevo (XIII–XIV sec.)

- Electione de eo canonice celebrata

- Un Impero vacante? La signoria sovralocale di Oberto Pelavicino in Lombardia tra idealità imperiale e città (1249–1259)

- Un regno senza impero?

- Narrazione e percezione dell’impero nella cronachistica

- Artikel

- Building an Aristocratic Identity in Medieval Italy

- Memorie della Chiesa di Molfetta

- „Per fuoco e per estimo“

- Fonti e approcci sulla fiscalità pontificia per la Basilicata del XIV secolo

- La comunità tedesca a L’Aquila tra i secoli XV–XVI

- Whose Bishop/Who’s the Bishop?

- Si in evidentem: Pacht von Kirchengut über die Pönitentiarie

- Rhetorical vs. Historical Discourse?

- Ottavio Villani – ein Gegner der päpstlichen Politik im Dreißigjährigen Krieg

- Italian and German Colonialism beyond Comparison

- Geleitwort zum Beitrag „Gewaltlust“ von Habbo Knoch

- Gewaltlust

- Forum

- Der Gastronationalismus und Alberto Grandis Thesen – oder: Zur Prägekraft der italienischen Küche

- Tagungen des Instituts

- I monasteri di Subiaco e Farfa come crocevia monastico-culturale nei secoli XV e XVI

- Von den NS-Tätern sprechen, der Opfer gedenken. Perspektiven einer deutsch-italienischen Erinnerung zwischen Forschung und Vermittlung

- Circolo Medievistico Romano

- Circolo Medievistico Romano 2024

- Nachrufe

- Cosimo Damiano Fonseca (1932–2025)

- Dieter Girgensohn (1934–2025)

- Gerhard Müller 1929–2024

- Rezensionen

- Verzeichnis der Rezensionen

- Leitrezensionen

- Tra reti politiche e prassi documentarie

- Una rete di persone

- Ein weiteres langes „langes Jahrhundert“?

- Rezensionen

- Verzeichnis der Rezensent*innen

- Register der in den Rezensionen genannten Autor*innen