Abstract

Interventional radiology is a rapidly growing discipline with an expanding variety of indications and techniques in pediatric and adult patients. Accordingly, the number of procedures during which monitoring either under sedation or under general anesthesia is needed is increasing. In order to ensure high-quality care as well as patient comfort and safety, implementation of anes-thesiology practice guidelines in line with institutional radiology practice guidelines is paramount [1]. However, practice guidelines are no substitute for lack of communi-cation between specialties.

Interdisciplinary indications within neurosciences call for efficient co-operation among radiology, neurology, neurosurgery, vascular surgery, anesthesiology and intensive care. Anesthesia team and intensive care personnel should be informed early and be involved in coordinated planning so that optimal results can be achieved under minimized risks and pre-arranged complication management.

1 Interventional neuroradiology

Interventional neuroradiology offers therapeutic and palliative care for a wide range of diseases of the central nervous system [2]. Optimal treatment results as reflected by low patient morbidity and mortality are bound to interdisciplinary cooperation between neurology, neu-rosurgery, neuroradiology, anesthesiology and intensive care [3]. A wide range of digital radiological image post-processing modalities can be applied within the frame of neurointerventions. The Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) facilitates direct access to the enormous amount of imaging data.

In most neurointerventions, access to the vascular system is gained via the groin. Following local or general anesthesia and a small incision of the skin, a catheter introducer with side port is inserted into the femoral artery using the Seldinger wire technique. Under contrast medium-enhanced angiographic guidance and with the help of a wire, a coaxial guiding catheter is advanced through the larger proximal vessels. For the intervention, microcatheter and microwire are advanced to the target vessel using the guiding catheter. After the procedure the system is removed, in some cases vascular closure systems are applied, and a compression bandage is applied to the insertion region for four to six hours.

2 Vascular occlusive interventions

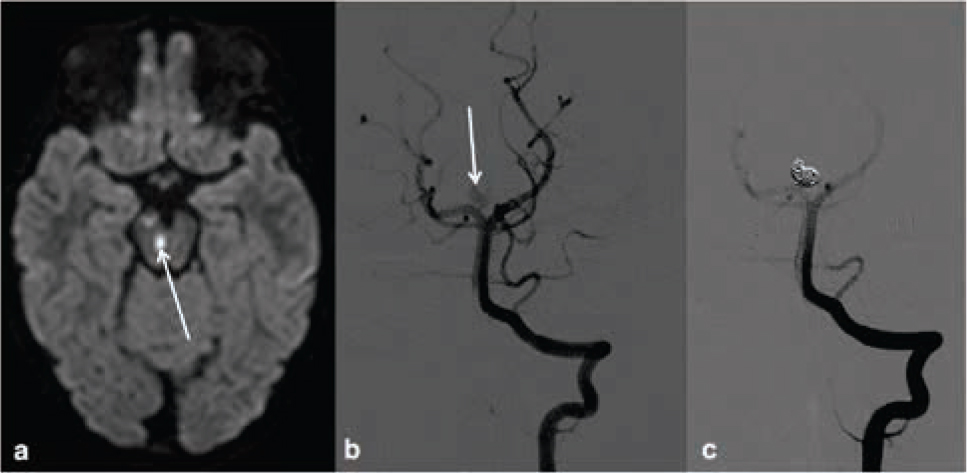

Vascular occlusive interventions provide minimally invasive treatment alternatives to conventional neurosurgical operations and are the only choice in cases that are surgically inaccessible. Cerebral aneurysm can be treated as scheduled intervention or, in case of emergency, by endovascular coiling with or without stents in order to induce thrombotic occlusion of the aneurysm. Outcome of patients treated with coiling is better than after surgical clipping (Figure 1), but early re-perfusion occurs more fre-quently [4]. Intravascular administration of glue (n-butyl cyanoacrylate), dehydrated alcohol or liquid embolics (Onyx®) into the arterial feeder vessels of arteriovenous malformations or fistulas causes vascular obliteration [5]. Combination with radiation and/or surgery is necessary in some cases. In the case of neoplasms, embolization of supply vessels with particles or coils prior to surgical removal or palliative treatment reduces bleeding complication.

Unusual case of a three year old girl with an incidentally found partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysm. The girl presented with oculomotoric palsies due to small brain stem and mesencephalic (arrow) infarctions found in diffusion weighted MRI (a). Digital subtraction angiography with injection of the left vertebral artery shows the aneurysm of the right proximal posterior cerebral artery (arrow) prior (b) and after (c) endovascular occlusion with platinum coils.

3 Vascular re-operating interventions

Vascular re-opening interventions provide minimally invasive treatment alternatives to operations in vascular surgery and cardiothoracic surgery.

In the case of arterial stenosis, balloon dilatation [6] and subsequent stenting may improve vascular perfu-sion [7]. In scheduled interventions, patients receive dual platelet aggregation inhibitors for five to seven days and heparin immediately before the intervention [8]. In acute stenting IIb/IIIa receptor blockers can be administered in addition to heparin and rapidly switched to platelet inhib-itors during the following days [9]. Thrombolytic drugs more efficiently dissolve thromboembolic clots when applied regionally by means of endovascular catheters [10, 11]. For acute stroke therapy, so-called stent retrievers were recently introduced to achieve retraction of intracranial thrombi with a high recanalization rate [12]. Fibrinolytic agents such as plasminogen activators can be additionally injected into the clot or the proximal vessel [13]. Concurrent antithrombosis with heparin and inhibi-tion of platelet aggregation to counteract re-thrombosis are recommended [14].

4 Thermoablation of Gasserian ganglion for trigeminal neuropathy

Patients suffering from neuropathic pain of the trigem-inal nerve resistant to drug therapy may be successfully treated by radiofrequency ablation of the Gasserian gan-glion [15]. The patient’s head is immobilized by a vacuum dental cast or a molded nosepiece. A native CT scan with skin fiducials is obtained. The pathway of the needle from the skin entrance point to the target in the trigeminal gan-glion is planned on the optical 3d navigation system. The electrocoagulation needle is advanced through an aiming device to the target. After confirmation of precise needle positioning by CT and electrophysiological testing electro-coagulation is performed at a temperature of 73 degrees of Celsius for 1 minute. Thermoablation provides a mini-mally invasive option with lower risks than does the neu-rosurgical approach using microvascular decompression.

5 Anaesthesia in neurointervention

Special considerations for radiological interventions comprise long-lasting procedures with patient immobility, induced hypertension or controlled hypotension, antico-agulation or reversal of anticoagulation and management of emergencies including raised intracranial pressure and bleeding complications. Furthermore, anesthesia teams have to be used to working in remote locations with jam-packed and minimally illuminated work environment (Figure 2) frequently exposed to radiation [2]. Whereas there is plenty of digital information available concerning the region of treatment, specific patient information regarding liver and kidney function, blood chemistry and clotting system, co-existing diseases and impairments, and current health status may be scarce. Furthermore, availability of matched blood products and need for post-operative care have to be cleared prior to the intervention. In the case of life-threatening conditions, the patient needs to be rapidly and safely transferred to operating theatres of either vascular surgery or neurosurgery with advanced facilities for emergency assistance.

The frequently observed jam-packed anesthesia working place in radiology department; patient monitored with NIRS.

6 Monitoring

Hemodynamic monitoring is necessary in all patients who receive an anesthetist’s attention. Minimal requirements are ECG, pulse oximetry (SpO2) and non-invasive blood pressure [16]. In ventilated patients, repeated blood gas exams (Hb, pH, PaCO 2, PaO2) are also needed. End-tidal capnometry (PetCO2) is especially important for adjustment of respirator parameters without impairing brain circulation. Central venous lines via the subclavian vein are preferred to access via the internal jugular veins. Injury of the carotid artery with the potential of impaired cerebral venous circulation is particularly detrimental in neurosurgical patients. Adjustment of certain blood pressure levels is best achieved by continuous measurements via the arterial line. Controlled hypotension can be desired during embolization or positioning of the vascular stent, whereas induced hypertension is frequently applied in case of stroke. Monitoring of arrhythmias, especially bradycardia, following dilatation in the carotid region is important. In patients with a history of congestive heart failure or a history of renal insufficiency measurements of central venous pressure may be necessary. Pulmonary arterial pressures can be estimated with Swan-Ganz catheters or by pulse-induced contour cardiac output (PiCCO) via the arterial catheter. Pressure transducers and ICP system are mounted on the radiology table to avoid repeated adjust-ment of the level [16]. Temperature monitoring and exter-nal warming e.g. by Bair HuggerTM is obligatory in children. Hourly assessment of urine output is needed, especially in long-lasting interventions.

Neurogenic stunned myocardium or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy refers to transient left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and is commonly observed patients with acute intracranial bleeding i.e. in poor grade SAH patients. Patients can present with cardiovascular instability, ECG abnormalities (ST-segment elevation) and cardiac enzyme elevation. Echocardiography commonly reveals regional, predominantly apical, or global left ventricular wall motion abnormality. This phenomenon is reversible and improvement of cardiac contractility in the acute phase is usually obtained with dobutamine.

Neuromonitoring of anaesthetized patients can be achieved by measuring intracranial pressure (ICP), by near infra-red spectroscopy (NIRS) or encephalographic methods. An intraventricular catheter with CSF drainage is the preferred method of ICP monitoring in cases with early hydrocephalus. Intraparenchymal sensors for ICP meas-urement are more easily placed bedside in the emergency situation, however excess cerebrospinal fluid cannot be removed. Currently no noninvasive device serves as reliable ICP monitor [17]. Changes in brain tissue oxygen satu-ration can be non-invasively and continuously estimated by NIRS to allow early detection of cerebral ischemia (Figure 2). Improvement of cerebral perfusion by adjusting respiratory and cardiac parameters can be verified [18]. Several methods based on the electroencephalogram such as bi-spectral index (BIS), Narcotrend and entropy permit the level of sedation and narcosis to be assessed in anesthetized patients and general anesthetic consumption and anesthetic recovery times to be reduced [19].

7 Sedoanalgesia (Conscious sedation)

In contrast to vascular or neurosurgical operations, patients can be safely monitored under conscious sedation during minimally invasive interventions.

In some procedures patient cooperation is advanta-geous, e.g. during thermoablation of the trigeminal nerve the conscious patient can respond to radiologists’ questions. Together with CT guidance, patient feedback helps to precisely position the probe. Furthermore, intra-arterial thrombectomy in sedoanalgesia is associated with improved outcome if treatment delay from induction of general anesthesia can be avoided and a stable hemod-ynamic status maintained [4, 16]. Although pain during insertion of the introducer may be tolerable for most patients, mild sedoanalgesia increases patient comfort, especially when repeated interventions are scheduled.

8 General anaesthesia

In children, non-responding patients and emergency patients neurointerventions are preferably performed in general anesthesia. This underlines the need for a ful-ly-equipped anesthesia working place with invasive mon-itoring facilities. Invasive pressure measurement (arterial pressure, pulmonary arterial pressure, central venous pressure) is particularly needed in hemodynamically and medically unstable patients and whenever frequent exam-inations of blood gases and clotting system are requested. Strict immobilization of the patient is best achieved by general anesthesia and muscle relaxation. In long-lasting interventions and whenever hyperosmotic contrast medium is administered urinary drainage by indwelling catheter is needed. The major disadvantage of general anesthesia in neurointervention is that the neurological status cannot be continuously monitored during the procedure. For this reason, patients are weaned early so that a neurological exam can be performed immediately after recovery from anesthesia [20, 21].

9 Complication management

Generally, complication rates are low [22] and infections are rarely observed [23]. Short-term follow-up results in young patients are convincing, but so far we lack time-dependent patient outcomes [24].

Abandonment of ionic contrast media reduced the incidence of severe allergic reactions to approximately 0.04% [25]. Whereas incompatibility of contrast medium due to drops in blood pressure immediately after admin-istration is not a rare event, minor allergic reactions e.g. rash were reported in approximately 3% of applications [25]. In the case of a known allergy preoperative combined treatment with prednisolone and H1 and H2 blockers does not guarantee event-free administration. Anesthesia mon-itoring is obligatory and the anesthesia team has to be prepared for treatment of severe anaphylactic shock and cardiorespiratory arrest.

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) following administration of contrast media leading to renal insufficiency was observed in 20% to 30% of patients with pre-existing impairment of renal function [26]. Kidney protection by forced hydration before and after contrast media exposure and administration of N-acetylcysteine or proanthocyanidin extract is still a matter of debate [27, 28, 29].

Thromboembolic complications following neurointerventions were observed in 4%-12% of patients. Perforation of aneurysms occurs in approximately 4% [30]. Acute intracranial bleeding may arise from inserted guide wires and microcatheters, and may follow balloon dilatation and positioning of stents. Bleeding can result in rapid increase in intracranial pressure. Adequate perfusion pressure of the brain tissue has to be maintained, with the mean arterial pressure exceeding the intracranial pressure by 60 mmHg until neurosurgical craniotomy can be performed. Close monitoring is essential, invasive arterial blood pressure must be adapted and heparin must be reversed using protamine sulfate. Elevated ICP can be treated by draining CSF through an intraventricular catheter, increased sedoanalgesia, by administering osmotherapy (mannitol, hypertonic saline) and mild to moderate hyperventilation (PCO2 30–35mmHg, preserved only for acute elevations of ICP). Hyperventilation is not recommended for prophylactic treatment of increased ICP because of the potential for worsening cerebral ischemia. A CPP of a least 50mmHg (CPP = MAP-ICP) should be maintained during neurointerventions. CPP estimation requires correct referencing for MAP at the level of the foramen of Monro to avoid CPP overestimation.

10 Radiation protection

Working in radiology results in a great deal of exposure to radiation. Radiation protection is paramount using full-body lead aprons, thyroid shields, eye protection and portable and static glass shields. As radiation rapidly declines with distance, anesthesia personnel should not hover over radiation sources [2, 21]. Radiation dosimeters that record the accumulated exposure to radiation are compulsory for each co-worker.

11 Standard operating procedures (SOPs)

Significant progress in the development of neurointerventional techniques has been achieved over the last twenty years, resulting in a variety of radiologic interventions for the treatment of cerebrovascular diseases [31]. Indications range from neoplasms to malformation and abnormalities of vessel walls to acute obstruction and rupture of vessels [13, 32, 33]. This partly explains the co-existence of numerous treatment modifications and recommendations at the same time and why practice guidelines differ from center to center. Quality requirements for anesthesia equipment and supplies match the requirements prevailing in neurosurgical theatres. Specific and general standards at our university department are expressed in preoperative (Table 1), intraoperative (Table 2) and postoperative SOPs (Table 3) that can be used as check cards.

Pre-operative SOP before neuro-intervention

| I. | Anesthesiology equipment and supply | |

| A | Check for completeness (daily prior to first administration) Connections to piped oxygen and air | |

| 1. | Connections to central electrical outlets | |

| 2. | Anesthesia machine, ventilator, ventilation tubes and bags | |

| 3. | Patient monitor, modules and leads | |

| 4. | Filled vapors | |

| 5. | Suction unit | |

| 6. | Motor syringes, blood warmer, cell saver | |

| 7. | Fully equipped anesthesia cart | |

| 8. | Emergency equipment | |

| 9. | Access to difficult airway cart | |

| 10. | Access to defibrillator | |

| B. | Check for functionality | |

| 1. | Leak test for ventilation unit | |

| 2. | Leak test for ventilation bag | |

| II. | Patient premedication and informed consent | |

| A. | Preoperative assessment: | |

| 1. | Category (elective, urgent, emergency, ICU) | |

| 2. | Chronic infections (e.g. HCV, HBV) | |

| 3. | Patient characteristics (age, co-morbidities, current medication, venous access, cardiac and respiratory status) | |

| 4. | Clinical evidence (recent chest x-ray, recent ECG, sonography) | |

| 5. | Allergies | |

| 6. | Laboratory findings (blood chemistry, coagulation, kidney and liver function) | |

| 7. | Availability of matched blood products | |

| 8. | Consultant opinion (pediatrician, intensivist, cardiologist) | |

| B. | Preoperative visit | |

| 1. | Case history and chief complaints | |

| 2. | Physical examination (airway inspection, auscultation of lung and heart, mobilization) | |

| 3. | Anesthesia information (method, risks, complication management) | |

| 4. | Documentation and informed consent | |

| C. | Premedication | |

| 1. | Preoperative fasting (6 hours in adults, 2 to 4 hrs in children) | |

| 2. | Chronic medication that should be discontinued: e.g. antithrombotics | |

| 3. | Oral sedation: | in adults: midazolam 3.75 to 7.5 mg |

| in children: midazolam syrup: 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg lidocaine/prilocaine ointment and occlusion bandage on site of venous access 30 minutes prior to anesthesia induction | ||

Intraoperative SOP during neurointervention

| I. | Observation |

| A. | Characteristics |

| Radiation protection (full-body lead aprons, thyroid shields, eye protection, lead shields) Keep dosimeter close to the body under apron No manipulation on the operating table during the procedure (avoid leaning or propping yourself on the table) | |

| B. | Patient positioning |

| 1. | Supine or prone position, arms parallel to the body |

| 2. | Padding with foam rubber or gel pads |

| 3. | Head positioning in head-contoured foam rubber frame |

| Additional fixation with self-adhesive bandage over forehead or gel pad fixation at the root of the nose | |

| C. | Monitoring |

| 1. | ECG and impedance-respiratory frequency |

| 2. | Non-invasive blood pressure |

| 3. | Pulse oximetry |

| 4. | CO2 measurement respiratory or transcutaneous |

| D. | Documentation |

| Electronic or manual recording of vital signs, readings and events | |

| II. | Sedoanalgesia (Conscious sedation) |

| Characteristics, patient positioning, monitoring and documentation, see: I. Observation | |

| A. | Preparation |

| 1. | Venous access preferably on left forearm or back of the hand |

| 2. | Infusion for keeping vein open or forced hydration ELO-MEL or lactated Ringer’s solution |

| 3. | Oxygen mask (remove metal bow!) or oxygen nasal probe Oxygen flow: 2–5 L/min |

| 4. | Capnometry: side-stream measurement |

| B. | Medication Sedation |

| Midazolam i.v., in 1 mg split doses Propofol 30 - 50 mg i.v. | |

| Analgesia | |

| Piritramide 6 - 9 mg i.v. S-ketamine 10 - 15 mg i.v. Remifentanil (2 mg/40ml) by motor syringe 0.1 - 0.25 g/kg/min CAVE: cumulative effects of midazolam and propofol | |

| III. | General aenesthesia |

| A. | Characteristics |

| 1. | Blood pressure must be maintained with a view to patient’s neurologic status. Ideally, systolic blood pressure (SBP) should not exceed 140 mmHg unless clinical evidence of vasospasm is observed. |

| 2. | Temporary arterial blood pressure measurement via the radiological access in the femoral artery is practicable but only as an exception. |

| 3. | In the case of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), administer mannitol and/or furosemide, consider short- lasting hyperventilation. |

| 4. | In the case of threatening herniation keep mean arterial pressure (MAP) approx. 60 mm Hg above ICP to allow adequate perfu sion of the brain. |

| Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) = MAP - ICP | |

| 5. | ICP monitoring via intraventricular catheter, open system for CSF drainage |

| 6. | Calibration of the drainage device 5 – 10 cm above foramen of Monro |

| 7. | Elevate blood pressure with ephedrine 5–10 mg bolus, or phenylephrine 0.1–0.2 mg bolus or (50/50) by motor syringe or noradrenalin (5/50) by motor syringe |

| 8. | Seizure prophylaxis is generally not recommended, calcium channel block, if indicated |

| 9. | Early provision of blood products and cell saver, if indicated |

| 10. | Repeated blood gas analysis |

| 11. | Confirm postoperative care at ICU (neurology, neurosurgery). |

| B. | Induction of general anesthesia |

| • | 1. Monitoring, see: I. Observation and neuromonitoring |

| • | 2. Fentanyl 0.02–0.05 mg/kg BW |

| • | 3. Propofol 2.5 mg/kg BW (in children up to 5 mg/kg BW) |

| • | 4. Muscle relaxation with rocuronium bromide 0.3–0.6 mg/kg BW |

| • | 5. Relaxometry: keep Train of Four (TOF) below 30%. Avoid coughing and spontaneous movements by patient. |

| • | 6. Endotracheal intubation |

| • | 7. Indwelling catheters: two large-bore peripheral intravenous lines central venous line in acute SAH and impaired cardiopulmonary state arterial line preferably left radial artery urine catheter and bag for hourly measurement |

| • | 8. Oropharyngeal temperature probe - lower esophagus |

| • | 9. Bair Hugger |

| C. | Maintenance of general anesthesia: |

| 1. | Balanced with sevoflurane or isoflurane in O2/air and opioids or TIVA: propofol and remifentanil administered by motor syringe |

| 2. | Pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV) |

| Keep CO2et between 30 and 35 mm Hg equivalent to PaCO2 of 35 – 40 mm Hg (normocapnia) | |

| 3. | Antacids: famotidin 20mg or pantoprazole 40mg |

| 4. | Volume replacement: cautious; crystalloid solution (ELO-MEL). |

| In SAH with vasospasm “triple H therapy” is recommended (hypervolemia, hypertension, hemodilution). | |

| D. | Weaning In elective cases and SAH (Hunt & Hess I) preferably in the operating theatre. If indicated, muscle relaxation to be reversed with: prostigmine/glycopyrronium 1–2/0.2–0.4 or sugammadex 200mg (coughing and choking by the patient must be avoided). In SAH (Hunt & Hess > II) weaning preferably at the ICU. Arrange early for patient to be transferred to the ICU in intensive care bed, with respirator, continuous monitoring, medication administered by motor syringe. |

Postoperative SOP after neurointervention

| I. | Intensive Care |

| 1. | Course of intervention handed over directly to the intensivist in general anesthesia by the neuroradiologist and anesthetist. |

| 2. | Transfer to ICU (neurology, neurosurgery) under continued monitoring |

| 3. | Antithrombotic therapy with abciximab, acetylsalicyclic acid and heparin is administered, if requested, by the radiologist e.g. heparin 10 000 IU/24 hrs by motor syringe after cerebral coiling. |

| 4. | Aim is early weaning from ventilation. |

| 5. | Early measures comprise neurological examination and laboratory exam of blood gas, electrolytes, clotting system, liver and kidney function. |

| 6. | Follow-up investigation is scheduled in cooperation with neuroradiologist and anesthetist. |

| II. | Intermediate Care For thermoablation of the trigeminal nerve in dissociative anesthesia with S-ketamine 0.25–0.4 mg/kgBW intermediate care in silent and shaded environment is sufficient. |

Contributors:

WL, MST, FJW searched for and selected references, created the structure of the review and prepared the first draft and subsequent versions. AG, RH, RB supplied the text for their subspecialities.

Conflict of interest statement

Authors state no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all nurses of the anesthesia and intensive care units, all radiology technicians involved in the treatment of our patients for their good multidisciplinary cooperation.

References

[1] Steele JR, Wallace MJ, Hovsepian DM, James BC, Kundu S, Miller DL, Rose SC, Sacks D, Shah SS, Cardella JF. Guidelines for Establishing a Quality Improvement Program in Interventional Radiology. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010; 21:617–62510.1016/j.jvir.2010.01.010Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Ard JL Jr., Huncke TK. A Trip to a Foreign Land: Interventional Neuroradiology. ASA Monitor 2013; 77(11):22–24Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Park HS, Kwon SC, Kim MH, Park ES, Sim HB, Lyo IU. Endovascular Coil Embolization of Distal Anterior Cerebral Artery Aneurysms: Angiographic and Clinical Follow-up Results. Neurointervention. 2013; 8(2):87–9110.5469/neuroint.2013.8.2.87Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005; 366(9488): 809–81710.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Kim ST, Jeong HW, Seo J. Onyx Embolization of Dural Arteriovenous Fistula, using Scepter C Balloon Catheter: a Case Report. Neurointervention. 2013; 8(2):110–11410.5469/neuroint.2013.8.2.110Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Alurkar A, Karanam LS, Oak S, Nayak S, Sorte S. Role of balloon-expandable stents in intracranial atherosclerotic disease in a series of 182 patients. Stroke. 2013; 44(7):2000–200310.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001446Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Alurkar A, Karanam LS, Nayak S, Oak S. Stent-assisted coiling in ruptured wide-necked aneurysms: A single-center analysis. Surg Neurol Int. 2012; 3:13110.4103/2152-7806.102946Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Van Den Berg JC. Strategies for optimizing the safety of carotid stenting in the hyperacute period after onset of symptoms. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2014; 55(2 Suppl 1):21–32Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Zahn R, Ischinger T, Hochadel M, Mark B, Zeymer U, Jung J, Schramm A, Hauptmann KE, Seggewiss H, icke I, Mudra H, Senges J; Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausärzte (ALKK). Clin Res Cardiol. 2007;96(10):730–73710.1007/s00392-007-0551-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] NINDS. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The national institute of neurological disorders and stroke rt-PA stroke study group. N Engl JMed. 1995; 333:1581–158710.1056/NEJM199512143332401Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Lin DDM, Gailloud P, Beauchamp NJ, Aldrich EM, Wityk RJ, Murphy KJ. Combined stent placement and thrombolysis in acute vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003; 24:1827–1833Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Novakovic RL, Toth G, Narayanan S, Zaidat OO. Neurology. Retrievable stents, “stentrievers,” for endovascular acute ischemic stroke therapy. 2012;79(13 Suppl 1):S148–15710.1212/WNL.0b013e3182697e9eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Sacks D, Black CM, Cognard C, Connors JJ, Frei D, Gupta R, Jovin TG, Kluck B, Meyers PM, Murphy KJ, Ramee S, Rüfenacht DA, Stallmeyer MJB, Vorwerk D. Multisociety Consensus Quality Improvement Guidelines for Intraarterial Catheter-directed Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke, from the American Society of Neuroradiology, Canadian Interventional Radiology Association, Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy, and Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2013; 24(2):151–16310.1002/ccd.24862Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Rapold HJ, Lu HR, Wu ZM, Nijs H, Collen D. Requirement of heparin for arterial and venous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator. Blood. 1991; 77(5):1020–102410.1182/blood.V77.5.1020.1020Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Bale RJ, Burtscher J, Eisner W, Obwegeser AA, Rieger M, Sweeney RA, Dessl A, Giacomuzzi SM, Twerdy K, Jaschke W. Computer- assisted neurosurgery by using a noninvasive vacuum- affixed dental cast that acts as a reference base: another step toward a unified approach in the treatment of brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 2000; 93(2):208- 21310.3171/jns.2000.93.2.0208Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Rosas AL: Anesthesia for Interventional Neuroradiology; Part I: Introduction, General Considerations, and Monitoring. The Internet Journal of Anesthesiology 1997; Vol 1 N 1: http://www. ispub.com/journals/IJA/Vol1N1/articles/neuroan1.htm10.5580/2659Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Helbok R, Olson DM, Le Roux PD, Vespa P.The Participants in the International Multidisciplinary Consensu Conference on Mulitmodality M: Intracranial Pressure and Cerebral Perfusion Pressure Monitoring in Non-TBI Patients: Special Consida-rations. Neurocritical Care 2014;Suppl2:S85–9410.1007/s12028-014-0040-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] J. M. Murkin JM, Arango M. Near-infrared spectroscopy as an index of brain and tissue oxygenation. Br. J. Anaesth. 2009; 103 (suppl 1): i3-i1310.1093/bja/aep299Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Shepherd J, Jones J, Frampton G, Bryant J, Baxter L, Cooper K. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of depth of anesthesia monitoring (E-Entropy, Bispectral Index and Narcotrend): a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2013; 17(34):1–26410.3310/phr01020Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] John N, Mitchell P, Dowling R, Yan B. Is general anesthesia preferable to conscious sedation in the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke with intra-arterial mechanical thrombectomy? A review of the literature. Neuroradiology. 2013; 55(1):93–10010.1007/s00234-012-1084-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Lee CZ, Young WL. Anesthesia for endovascular neurosurgery and interventional neuroradiology. Anesthesiol Clin. 2012; 30(2):127–14710.1016/j.anclin.2012.05.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Schulenburg E, Matta B. Anesthesia for interventional neuroradiology. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2011; 24(4):426–43210.1097/ACO.0b013e328347ca12Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Horowitz MB, Dutton K, Purdy PD. Assessment of Complication Types and Rates Related to Diagnostic Angiography and Interventional N euroradiologic Procedures. A Four Year Review (1993–1996). Interv Neuroradiol. 1998; 4(1):27–3710.1177/159101999800400103Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] 24 Kelkar PS, Fleming JB, Walters BC, Harrigan MR. Infection risk in neurointervention and cerebral angiography. Neurosurgery. 2013; 72(3):327–33110.1227/NEU.0b013e31827d0ff7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Park HS, Kwon SC, Shin SH, Park ES, Sim HB, Lyo IU. Clinical and radiologic results of endovascular coil embolization for cerebral aneurysm in young patients. Neurointervention. 2013; 8(2):73–7910.5469/neuroint.2013.8.2.73Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Katayama H, Yamaguchi K, Kozuka Tet al. Adverse reactions to ionic and nonionic contrast media. Radiology 1990; 175:270–27610.1148/radiology.175.3.2343107Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Davenport MS, Khalatbari SM, Cohan RH, Dillman JR, Myles JD, Ellis JH. Contrast material-induced nephrotoxicity and intravenous low-osmolality contrast material: Risk stratification by using estimated glomerular filtration rate. Radiology 2013; 268:719–72810.1148/radiol.13122276Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Sadat U. N-acetylcysteine in contrast-induced acute kidney injury: clinical use against principles of evidence-based clinical medicine! Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2014; 12(1):1–310.1586/14779072.2014.852066Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Mahmoodi K, Sohrabi B, Ilkhchooyi F, Malaki M, Khaniani ME, Hemmati M. The Efficacy of Hydration with Normal Saline Versus Hydration with Sodium Bicarbonate in the Prevention of Contrast-induced Nephropathy. Heart Views. 2014; 15(2):33–3610.4103/1995-705X.137489Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Ulusoy S, Ozkan G, Mungan S, Orem A, Yulug E, Alkanat M, Yucesan FB. GSPE is superior to NAC in the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy: might this superiority be related to caspase 1 and calpain 1? Life Sci. 2014; 103(2):101–11010.1016/j.lfs.2014.03.030Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Orrù E, Roccatagliata L, Cester G, Causin F, Castellan L. Complications of endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Eur J Radiol. 2013; 82(10):1653–165810.1016/j.ejrad.2012.12.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Jung C, Kwon BJ, Han MH. Evidence-Based Changes in Devices and Methods of Endovascular Recanalization Therapy. Neurointervention. 2012; 7(2): 68–7610.5469/neuroint.2012.7.2.68Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Lee BH. Guideline for intracranial stenting of symptomatic intracranial artery stenosis: preliminary report. Neurointervention. 2007; 2:30–35Suche in Google Scholar

© 2016 Wolfgang Lederer et al.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- The possible molecular regulation mechanism of CIK cells inhibiting the proliferation of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma NCL-H157 Cells

- Case Report

- Urethral stone of unexpected size: case report and short literature review

- Case Report

- Complete remission through icotinib treatment in Non-small cell lung cancer epidermal growth factor receptor mutation patient with brain metastasis: A case report

- Research Article

- FPL tendon thickness, tremor and hand functions in Parkinson’s disease

- Research Article

- Diagnostic value of circulating tumor cells in cerebrospinal fluid

- Research Article

- A meta-analysis of neuroprotective effect for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the treatment of glaucoma

- Research Article

- MiR-218 increases sensitivity to cisplatin in esophageal cancer cells via targeting survivin expression

- Research Article

- Association of HOTAIR expression with PI3K/Akt pathway activation in adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction

- Research Article

- The role of interleukin genes in the course of depression

- Case Report

- A rare case of primary pulmonary diffuse large B cell lymphoma with CD5 positive expression

- Research Article

- DWI and SPARCC scoring assess curative effect of early ankylosing spondylitis

- Research Article

- The diagnostic value of serum CEA, NSE and MMP-9 for on-small cell lung cancer

- Case Report

- Dysphonia – the single symptom of rifampicin resistant laryngeal tuberculosis

- Review Article

- Development of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors against EGFR T790M. Mutation in non small-cell lung carcinoma

- Research Article

- Negative regulation of CDC42 expression and cell cycle progression by miR-29a in breast cancer

- Research Article

- Expression analysis of the TGF-β/SMAD target genes in adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction

- Research Article

- Blood cells in thyroid cancer patients: a possible influence of apoptosis

- Research Article

- Detected EGFR mutation in cerebrospinal fluid of lung adenocarcinoma patients with meningeal metastasis

- Mini-review

- Pathogenesis-oriented approaches for the management of corticosteroid-resistant or relapsedprimary immune thrombocytopenia

- Research Article

- GSTP1 A>G polymorphism and chemosensitivity of osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis

- Research Article

- A meta-analysis of adiponectin gene rs22411766 T>G polymorphism and ischemic stroke susceptibility

- Research Article

- The diagnosis and pathological value of combined detection of HE4 and CA125 for patients with ovarian cancer

- Research Article

- SOX7 inhibits tumor progression of glioblastoma and is regulated by miRNA-24

- Research Article

- Sevoflurane affects evoked electromyography monitoring in cerebral palsy

- Case Report

- A case report of hereditary spherocytosis with concomitant chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Case Report

- A case of giant saphenous vein graft aneurysm followed serially after coronary artery bypass surgery

- Research Article

- LncRNA TUG1 is upregulated and promotes cell proliferation in osteosarcoma

- Review Article

- Meningioma recurrence

- Case Report

- Endobronchial amyloidosis mimicking bronchial asthma: a case report and review of the literature

- Case Report

- A confusing case report of pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis and literature review

- Research Article

- Effect of hesperetin on chaperone activity in selenite-induced cataract

- Research Article

- Clinical value of self-assessment risk of osteoporosis in Chinese

- Research Article

- Correlation analysis of VHL and Jade-1 gene expression in human renal cell carcinoma

- Research Article

- Is acute appendicitis still misdiagnosed?

- Retraction

- Retraction of: application of food-specific IgG antibody detection in allergy dermatosis

- Review Article

- Platelet Rich Plasma: a short overview of certain bioactive components

- Research Article

- Correlation between CTLA-4 gene rs221775A>G single nucleotide polymorphism and multiple sclerosis susceptibility. A meta-analysis

- Review Article

- Standards of anesthesiology practice during neuroradiological interventions

- Research Article

- Expression and clinical significance of LXRα and SREBP-1c in placentas of preeclampsia

- Letter to the Editor

- ARDS diagnosed by SpO2/FiO2 ratio compared with PaO2/FiO2 ratio: the role as a diagnostic tool for early enrolment into clinical trials

- Research Article

- Impact of sensory integration training on balance among stroke patients: sensory integration training on balance among stroke patients

- Review Article

- MicroRNAs as regulatory elements in psoriasis

- Review Article

- Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and postpandemic influenza in Lithuania

- Review Article

- Garengeot’s hernia: two case reports with CT diagnosis and literature review

- Research Article

- Concept of experimental preparation for treating dentin hypersensitivity

- Research Article

- Hydrogen water reduces NSE, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Research Article

- Xanthogranuloma of the sellar region diagnosed by frozen section

- Case Report

- Laparoscopic antegrade cholecystectomy: a standard procedure?

- Case Report

- Maxillary fibrous dysplasia associated with McCune-Albright syndrome. A case study

- Regular Article

- Sialoendoscopy, sialography, and ultrasound: a comparison of diagnostic methods

- Research Article

- Antibody Response to Live Attenuated Vaccines in Adults in Japan

- Conference article

- Excellence and safety in surgery require excellent and safe tutoring

- Conference article

- Suggestions on how to make suboptimal kidney transplantation an ethically viable option

- Regular Article

- Ectopic pregnancy treatment by combination therapy

- Conference article

- Use of a simplified consent form to facilitate patient understanding of informed consent for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Regular Article

- Cusum analysis for learning curve of videothoracoscopic lobectomy

- Regular Article

- A meta-analysis of association between glutathione S-transferase M1 gene polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease susceptibility

- Conference article

- Plastination: ethical and medico-legal considerations

- Regular Article

- Investigation and control of a suspected nosocomial outbreak of pan-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an intensive care unit

- Regular Article

- Multifactorial analysis of fatigue scale among nurses in Poland

- Regular Article

- Smoking cessation for free: outcomes of a study of three Romanian clinics

- Regular Article

- Clinical efficacy and safety of tripterygium glycosides in treatment of stage IV diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Prevention and treatment of peritoneal adhesions in patients affected by vascular diseases following surgery: a review of the literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Surgical treatment of recidivist lymphedema

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- CT and MR imaging of the thoracic aorta

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Role of FDG-PET scan in staging of pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Sternal reconstruction by extracellular matrix: a rare case of phaces syndrome

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Prenatal diagnosis, 3-D virtual rendering and lung sparing surgery by ligasure device in a baby with “CCAM and intralobar pulmonary sequestration”

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Serum levels of inhibin B in adolescents after varicocelelectomy: A long term follow up

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Our experience in the treatment of Malignant Fibrous Hystiocytoma of the larynx: clinical diagnosis, therapeutic approach and review of literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Delayed recurrent nerve paralysis following post-traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysm

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Integrated therapeutic approach to giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: report of a case and review of the literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Celiac axis compression syndrome: laparoscopic approach in a strange case of chronic abdominal pain in 71 years old man

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- A rare case of persistent hypoglossal artery associated with contralateral proximal subclavian stenosis

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Contralateral risk reducing mastectomy in Non-BRCA-Mutated patients

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Professional dental and oral surgery liability in Italy: a comparative analysis of the insurance products offered to health workers

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Informed consent in robotic surgery: quality of information and patient perception

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Malfunctions of robotic system in surgery: role and responsibility of surgeon in legal point of view

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Medicolegal implications of surgical errors and complications in neck surgery: A review based on the Italian current legislation

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Iatrogenic splenic injury: review of the literature and medico-legal issues

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Donation of the body for scientific purposes in Italy: ethical and medico-legal considerations

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Cosmetic surgery: medicolegal considerations

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Voluntary termination of pregnancy (medical or surgical abortion): forensic medicine issues

- Review Article

- Role of Laparoscopic Splenectomy in Elderly Immune Thrombocytopenia

- Review Article

- Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system

- Review Article

- Efficacy and safety of splenectomy in adult autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Research Article

- Relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and Ph nose and salivary: proposal of a simple method outpatient in patients adults

- Case Report

- Idiopathic pleural panniculitis with recurrent pleural effusion not associated with Weber-Christian disease

- Research Article

- Morbid Obesity: treatment with Bioenterics Intragastric Balloon (BIB), psychological and nursing care: our experience

- Research Article

- Learning curve for endorectal ultrasound in young and elderly: lights and shades

- Case Report

- Uncommon primary hydatid cyst occupying the adrenal gland space, treated with laparoscopic surgical approach in an old patient

- Research Article

- Distraction techniques for face and smile aesthetic preventing ageing decay

- Research Article

- Preoperative high-intensity training in frail old patients undergoing pulmonary resection for NSCLC

- Review Article

- Descending necrotizing mediastinitis in the elderly patients

- Research Article

- Prophylactic GSV surgery in elderly candidates for hip or knee arthroplasty

- Research Article

- Diagnostic yield and safety of C-TBNA in elderly patients with lung cancer

- Research Article

- The learning curve of laparoscopic holecystectomy in general surgery resident training: old age of the patient may be a risk factor?

- Research Article

- Self-gripping mesh versus fibrin glue fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a randomized prospective clinical trial in young and elderly patients

- Research Article

- Anal sphincter dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: an observation manometric study

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- The possible molecular regulation mechanism of CIK cells inhibiting the proliferation of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma NCL-H157 Cells

- Case Report

- Urethral stone of unexpected size: case report and short literature review

- Case Report

- Complete remission through icotinib treatment in Non-small cell lung cancer epidermal growth factor receptor mutation patient with brain metastasis: A case report

- Research Article

- FPL tendon thickness, tremor and hand functions in Parkinson’s disease

- Research Article

- Diagnostic value of circulating tumor cells in cerebrospinal fluid

- Research Article

- A meta-analysis of neuroprotective effect for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the treatment of glaucoma

- Research Article

- MiR-218 increases sensitivity to cisplatin in esophageal cancer cells via targeting survivin expression

- Research Article

- Association of HOTAIR expression with PI3K/Akt pathway activation in adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction

- Research Article

- The role of interleukin genes in the course of depression

- Case Report

- A rare case of primary pulmonary diffuse large B cell lymphoma with CD5 positive expression

- Research Article

- DWI and SPARCC scoring assess curative effect of early ankylosing spondylitis

- Research Article

- The diagnostic value of serum CEA, NSE and MMP-9 for on-small cell lung cancer

- Case Report

- Dysphonia – the single symptom of rifampicin resistant laryngeal tuberculosis

- Review Article

- Development of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors against EGFR T790M. Mutation in non small-cell lung carcinoma

- Research Article

- Negative regulation of CDC42 expression and cell cycle progression by miR-29a in breast cancer

- Research Article

- Expression analysis of the TGF-β/SMAD target genes in adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction

- Research Article

- Blood cells in thyroid cancer patients: a possible influence of apoptosis

- Research Article

- Detected EGFR mutation in cerebrospinal fluid of lung adenocarcinoma patients with meningeal metastasis

- Mini-review

- Pathogenesis-oriented approaches for the management of corticosteroid-resistant or relapsedprimary immune thrombocytopenia

- Research Article

- GSTP1 A>G polymorphism and chemosensitivity of osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis

- Research Article

- A meta-analysis of adiponectin gene rs22411766 T>G polymorphism and ischemic stroke susceptibility

- Research Article

- The diagnosis and pathological value of combined detection of HE4 and CA125 for patients with ovarian cancer

- Research Article

- SOX7 inhibits tumor progression of glioblastoma and is regulated by miRNA-24

- Research Article

- Sevoflurane affects evoked electromyography monitoring in cerebral palsy

- Case Report

- A case report of hereditary spherocytosis with concomitant chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Case Report

- A case of giant saphenous vein graft aneurysm followed serially after coronary artery bypass surgery

- Research Article

- LncRNA TUG1 is upregulated and promotes cell proliferation in osteosarcoma

- Review Article

- Meningioma recurrence

- Case Report

- Endobronchial amyloidosis mimicking bronchial asthma: a case report and review of the literature

- Case Report

- A confusing case report of pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis and literature review

- Research Article

- Effect of hesperetin on chaperone activity in selenite-induced cataract

- Research Article

- Clinical value of self-assessment risk of osteoporosis in Chinese

- Research Article

- Correlation analysis of VHL and Jade-1 gene expression in human renal cell carcinoma

- Research Article

- Is acute appendicitis still misdiagnosed?

- Retraction

- Retraction of: application of food-specific IgG antibody detection in allergy dermatosis

- Review Article

- Platelet Rich Plasma: a short overview of certain bioactive components

- Research Article

- Correlation between CTLA-4 gene rs221775A>G single nucleotide polymorphism and multiple sclerosis susceptibility. A meta-analysis

- Review Article

- Standards of anesthesiology practice during neuroradiological interventions

- Research Article

- Expression and clinical significance of LXRα and SREBP-1c in placentas of preeclampsia

- Letter to the Editor

- ARDS diagnosed by SpO2/FiO2 ratio compared with PaO2/FiO2 ratio: the role as a diagnostic tool for early enrolment into clinical trials

- Research Article

- Impact of sensory integration training on balance among stroke patients: sensory integration training on balance among stroke patients

- Review Article

- MicroRNAs as regulatory elements in psoriasis

- Review Article

- Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and postpandemic influenza in Lithuania

- Review Article

- Garengeot’s hernia: two case reports with CT diagnosis and literature review

- Research Article

- Concept of experimental preparation for treating dentin hypersensitivity

- Research Article

- Hydrogen water reduces NSE, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Research Article

- Xanthogranuloma of the sellar region diagnosed by frozen section

- Case Report

- Laparoscopic antegrade cholecystectomy: a standard procedure?

- Case Report

- Maxillary fibrous dysplasia associated with McCune-Albright syndrome. A case study

- Regular Article

- Sialoendoscopy, sialography, and ultrasound: a comparison of diagnostic methods

- Research Article

- Antibody Response to Live Attenuated Vaccines in Adults in Japan

- Conference article

- Excellence and safety in surgery require excellent and safe tutoring

- Conference article

- Suggestions on how to make suboptimal kidney transplantation an ethically viable option

- Regular Article

- Ectopic pregnancy treatment by combination therapy

- Conference article

- Use of a simplified consent form to facilitate patient understanding of informed consent for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Regular Article

- Cusum analysis for learning curve of videothoracoscopic lobectomy

- Regular Article

- A meta-analysis of association between glutathione S-transferase M1 gene polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease susceptibility

- Conference article

- Plastination: ethical and medico-legal considerations

- Regular Article

- Investigation and control of a suspected nosocomial outbreak of pan-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an intensive care unit

- Regular Article

- Multifactorial analysis of fatigue scale among nurses in Poland

- Regular Article

- Smoking cessation for free: outcomes of a study of three Romanian clinics

- Regular Article

- Clinical efficacy and safety of tripterygium glycosides in treatment of stage IV diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Prevention and treatment of peritoneal adhesions in patients affected by vascular diseases following surgery: a review of the literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Surgical treatment of recidivist lymphedema

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- CT and MR imaging of the thoracic aorta

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Role of FDG-PET scan in staging of pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Sternal reconstruction by extracellular matrix: a rare case of phaces syndrome

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Prenatal diagnosis, 3-D virtual rendering and lung sparing surgery by ligasure device in a baby with “CCAM and intralobar pulmonary sequestration”

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Serum levels of inhibin B in adolescents after varicocelelectomy: A long term follow up

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Our experience in the treatment of Malignant Fibrous Hystiocytoma of the larynx: clinical diagnosis, therapeutic approach and review of literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Delayed recurrent nerve paralysis following post-traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysm

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Integrated therapeutic approach to giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: report of a case and review of the literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Celiac axis compression syndrome: laparoscopic approach in a strange case of chronic abdominal pain in 71 years old man

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- A rare case of persistent hypoglossal artery associated with contralateral proximal subclavian stenosis

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Contralateral risk reducing mastectomy in Non-BRCA-Mutated patients

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Professional dental and oral surgery liability in Italy: a comparative analysis of the insurance products offered to health workers

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Informed consent in robotic surgery: quality of information and patient perception

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Malfunctions of robotic system in surgery: role and responsibility of surgeon in legal point of view

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Medicolegal implications of surgical errors and complications in neck surgery: A review based on the Italian current legislation

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Iatrogenic splenic injury: review of the literature and medico-legal issues

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Donation of the body for scientific purposes in Italy: ethical and medico-legal considerations

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Cosmetic surgery: medicolegal considerations

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Voluntary termination of pregnancy (medical or surgical abortion): forensic medicine issues

- Review Article

- Role of Laparoscopic Splenectomy in Elderly Immune Thrombocytopenia

- Review Article

- Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system

- Review Article

- Efficacy and safety of splenectomy in adult autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Research Article

- Relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and Ph nose and salivary: proposal of a simple method outpatient in patients adults

- Case Report

- Idiopathic pleural panniculitis with recurrent pleural effusion not associated with Weber-Christian disease

- Research Article

- Morbid Obesity: treatment with Bioenterics Intragastric Balloon (BIB), psychological and nursing care: our experience

- Research Article

- Learning curve for endorectal ultrasound in young and elderly: lights and shades

- Case Report

- Uncommon primary hydatid cyst occupying the adrenal gland space, treated with laparoscopic surgical approach in an old patient

- Research Article

- Distraction techniques for face and smile aesthetic preventing ageing decay

- Research Article

- Preoperative high-intensity training in frail old patients undergoing pulmonary resection for NSCLC

- Review Article

- Descending necrotizing mediastinitis in the elderly patients

- Research Article

- Prophylactic GSV surgery in elderly candidates for hip or knee arthroplasty

- Research Article

- Diagnostic yield and safety of C-TBNA in elderly patients with lung cancer

- Research Article

- The learning curve of laparoscopic holecystectomy in general surgery resident training: old age of the patient may be a risk factor?

- Research Article

- Self-gripping mesh versus fibrin glue fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a randomized prospective clinical trial in young and elderly patients

- Research Article

- Anal sphincter dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: an observation manometric study