Abstract

This article is the first to study a bargaining model in a moral hazard framework where the principal is risk neutral and the agent is risk averse. We show that the power of incentives increases with the agent’s bargaining power if the contracts induce a high effort. However, under reasonable assumptions about the agent’s utility function, the contracts induce a high effort less often as the agent’s bargaining power increases. As for the social welfare, we are surprised to find that a utilitarian, who cares about the sum of the two parties’ certainty equivalents, is worse off as the agent’s bargaining power increases. These results are in sharp contrast to the literature, which features risk-neutral agents protected by limited liability.

Appendix

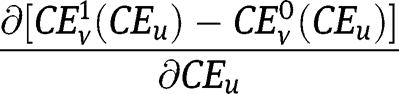

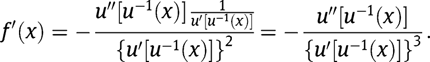

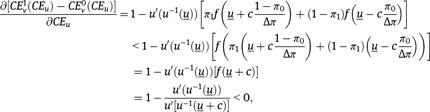

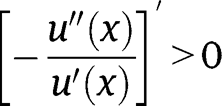

Proof of Corollary 2

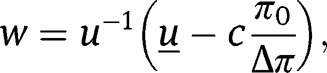

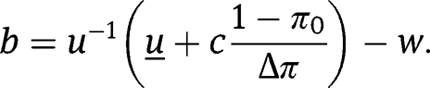

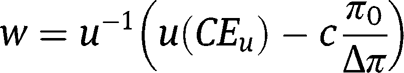

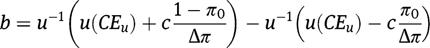

Denote  , which is increased as the agent’s bargaining power increases. Hence, we only need to show that both w and b increase with

, which is increased as the agent’s bargaining power increases. Hence, we only need to show that both w and b increase with  . From the Proposition 2, we have

. From the Proposition 2, we have

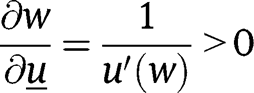

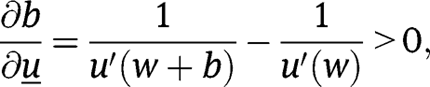

Therefore,

and

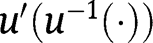

where the last inequality holds, because  is an increasing function.

is an increasing function.

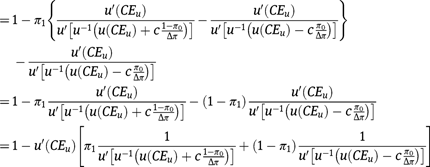

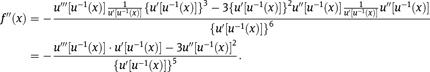

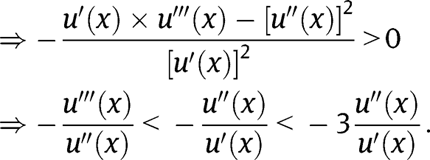

Proof of Lemma 3

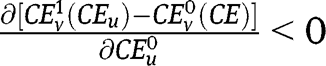

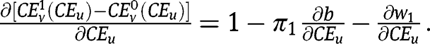

We want to show that  . From propositions 2 and 3, we know

. From propositions 2 and 3, we know  From the corollary’s proof, we know that

From the corollary’s proof, we know that

It follows that

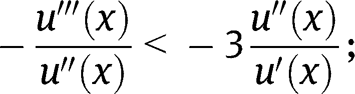

Denote  . We will show that

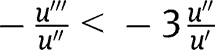

. We will show that  is strictly convex if

is strictly convex if  .

.

Therefore,

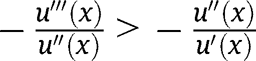

Denote  , it follows that

, it follows that

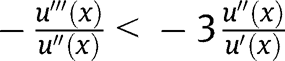

where the first inequality is due to the fact that  is strictly convex, and the second inequality is due to the fact that

is strictly convex, and the second inequality is due to the fact that  is a decreasing function.

is a decreasing function.

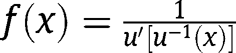

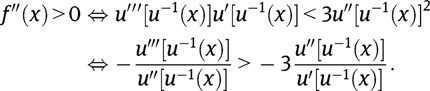

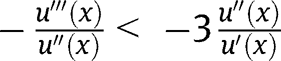

Proof of Corollary 5

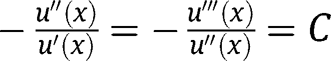

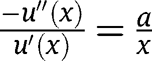

CARA implies that  , and therefore,

, and therefore,

IARA implies

DARA is equivalent to  , and, therefore, the condition

, and, therefore, the condition  may be violated. Consider a special class of DARA:

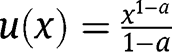

may be violated. Consider a special class of DARA:  , where

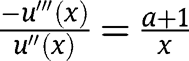

, where  . One can easily derive that

. One can easily derive that  and

and  . It follows immediately that

. It follows immediately that  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  .

.

References

Balkenborg, D. 2001. “How Liable Should a Lender Be? The Case of Judgment-Proof Firms and Environmental Risk: Comment.” American Economic Review91(3):731–8.10.1257/aer.91.3.731Suche in Google Scholar

Bental, B., and D.Demouguin. 2010. “Declining Labor Shares and Bargaining Power: An Institutional Explanation?”Journal of Macroeconomics32:443–56.10.1016/j.jmacro.2009.09.005Suche in Google Scholar

Conley, J. P., and S.Wilkie. 1996. “An Extension of the Nash Bargaining Solution to Nonconvex Problems.” Games and Economic Behavior13(1):26–38.10.1006/game.1996.0023Suche in Google Scholar

Demougin, D., and C.Helm. 2006. “Moral Hazard and Bargaining Power.” German Economic Review7(4):463–70.10.1111/j.1468-0475.2006.00130.xSuche in Google Scholar

Demougin, D., and C.Helm. 2011. “Job Matching When Employment Contracts Suffer From Moral Hazard.” European Economic Review55(7):964–79.10.1016/j.euroecorev.2011.04.002Suche in Google Scholar

Dittrich, M., and S.Städter. 2011. “Moral Hazard and Bargaining over Incentive Contracts,” Working paper.Suche in Google Scholar

Dubois, P., and T.Vukina. 2004. “Grower Risk Aversion and the Cost of Moral Hazard in Livestock Production Contracts.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics86(3):835–84.10.1111/j.0002-9092.2004.00634.xSuche in Google Scholar

Gabel, J., K.Dhont, H.Whitmore, and J.Pickreign. 2002. “Individual Insurance: How Much Financial Protection Does It Provide?”Health Affairs21:w172–81.10.1377/hlthaff.W2.172Suche in Google Scholar

Genicot, G., and D.Ray. 2006. “Bargaining Power and Enforcement in Credit Markets.” Journal of Development Economics79(2):398–412.10.1016/j.jdeveco.2006.01.006Suche in Google Scholar

Hueth, B., and E.Ligon. 1999. “Producer Price Risk and Quality Measurement.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics81:512–24.10.2307/1244011Suche in Google Scholar

Kihlstrom, R. E., and A. E.Roth. 1982. “Risk Aversion and the Negotiation of Insurance Contracts.” Journal of Risk and Insurance49(3):372–87.10.2307/252493Suche in Google Scholar

Kimball, M. S. 1990. “Precautionary Saving in the Small and in the Large.” Econometrica58:53–73.10.2307/2938334Suche in Google Scholar

Laffont, J.-J., and D.Martimort. 2001. The Theory of Incentives – The Principal Agent Model. Princeton, NJ and Oxford: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400829453Suche in Google Scholar

Nash, J. F.1950. “The Bargaining Problem.” Econometrica18:155–162.10.2307/1907266Suche in Google Scholar

Pauly, M. V., and A. M.Percy. 2000. “Cost and Performance: A Comparison of the Individual and Group Health Insurance Markets.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law25(1):9–26.10.1215/03616878-25-1-9Suche in Google Scholar

Pitchford, R. 1998. “Moral Hazard and Limited Liability: The Real Effects of Contract Bargaining.” Economics Letters61(2):251–9.10.1016/S0165-1765(98)00141-4Suche in Google Scholar

Rubinstein, A. 1982. “Perfect Equilibrium in a Bargaining Model.” Econometrica50(1):97–109.10.2307/1912531Suche in Google Scholar

Schlesinger, H. 1984. “2-Person Insurance Negotiation.” Insurance Mathematics and Economics3(3):147–9.10.1016/0167-6687(84)90055-6Suche in Google Scholar

Schmitz, P. 2005. “Workplace Surveillance, Privacy Protection and Efficiency Wages.” Labor Economics12(6):727–38.10.1016/j.labeco.2004.06.001Suche in Google Scholar

Shaked, A., and J.Sutton. 1984. “Involuntary Unemployment as a Perfect Equilibrium in a Bargaining Model.” Econometrica52(6):1351–64.10.2307/1913509Suche in Google Scholar

Starbird, S. A. 2005. Moral Hazard, Inspection Policy, and Food Safety. American Journal of Agricultural Economics87(1):15–27.10.1111/j.0002-9092.2005.00698.xSuche in Google Scholar

Thomasson, M. A. 2003. “The Importance of Group Coverage: How Tax Policy Shaped U.S. Health Insurance.” American Economic Review93(4):1373–84.10.1257/000282803769206359Suche in Google Scholar

Viaene, S., R.Veugelers, and G.Dedene. 2002. “Insurance Bargaining Under Risk Aversion.” Economic Modelling19(2):245–59.10.1016/S0264-9993(01)00062-1Suche in Google Scholar

Yao, Z. 2012. “Bargaining Over Incentive Contracts.” Journal of Mathematical Economics48(2):98–106.10.1016/j.jmateco.2012.01.003Suche in Google Scholar

Yogo, M. 2004. “Estimating the Elasticity of Intertemporal Substitution When Instruments Are Weak.” The Review of Economics and Statistics86(3):797–810.10.1162/0034653041811770Suche in Google Scholar

Yu, J.2008. “Bargaining Structures in French Dairy Sector and Impact of Policy Reforms,” Presented at 107th EAAE Seminar on Modeling of Agricultural and Rural Development Policies, Sevilla.Suche in Google Scholar

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71303245), MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (13YJC790077).

- 1

Limited liability means that the transfer from the principal to the agent must be non-negative.

- 2

With limited liability, the principal can only induce effort by rewarding the agent in the case of a good outcome; hence, the agent can get expected payoffs strictly higher than his reserve utility. The difference between the agent’s expected payoff and his reserve utility is called “limited liability rent” in the literature (see Chapter 4 of Laffont and Martimort (2001) for more detailed discussion).

- 3

For ease of exposition, we work in the space of the certainty equivalent rather than in the space of utility. The certainty equivalent of a random variable

for an agent with utility function u is defined as

for an agent with utility function u is defined as  .

. - 4

Conley and Wilkie (1996) have proved that the symmetric Nash extension is the only solution that satisfies Pareto optimality, symmetry, scale invariance, ethical monotonicity and continuity. They also show the uniqueness of the Nash extension. In this article, we use an asymmetric extension of their symmetric Nash extension.

- 5

That is, the agent gets a higher certainty equivalence from the bargaining.

- 6

It means that the range of the parameters of the contract inducing a high effort decreases as the agent’s bargaining power increases.

©2013 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin / Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Advances

- Dependence and Uniqueness in Bayesian Games

- Monopolistic Signal Provision†

- Multi-task Research and Research Joint Ventures

- Transparent Restrictions on Beliefs and Forward-Induction Reasoning in Games with Asymmetric Information

- A Simple Bargaining Procedure for the Myerson Value

- On the Difference between Social and Private Goods

- Optimal Use of Rewards as Commitment Device When Bidding Is Costly

- Labor Market and Search through Personal Contacts

- Contributions

- Learning, Words and Actions: Experimental Evidence on Coordination-Improving Information

- Are Trust and Reciprocity Related within Individuals?

- Optimal Contracting Model in a Social Environment and Trust-Related Psychological Costs

- Contract Bargaining with a Risk-Averse Agent

- Academia or the Private Sector? Sorting of Agents into Institutions and an Outside Sector

- Topics

- Poverty Orderings with Asymmetric Attributes

- Dictatorial Mechanisms in Constrained Combinatorial Auctions

- When Should a Monopolist Improve Quality in a Network Industry?

- On Partially Honest Nash Implementation in Private Good Economies with Restricted Domains: A Sufficient Condition

- Revenue Comparison in Asymmetric Auctions with Discrete Valuations

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Advances

- Dependence and Uniqueness in Bayesian Games

- Monopolistic Signal Provision†

- Multi-task Research and Research Joint Ventures

- Transparent Restrictions on Beliefs and Forward-Induction Reasoning in Games with Asymmetric Information

- A Simple Bargaining Procedure for the Myerson Value

- On the Difference between Social and Private Goods

- Optimal Use of Rewards as Commitment Device When Bidding Is Costly

- Labor Market and Search through Personal Contacts

- Contributions

- Learning, Words and Actions: Experimental Evidence on Coordination-Improving Information

- Are Trust and Reciprocity Related within Individuals?

- Optimal Contracting Model in a Social Environment and Trust-Related Psychological Costs

- Contract Bargaining with a Risk-Averse Agent

- Academia or the Private Sector? Sorting of Agents into Institutions and an Outside Sector

- Topics

- Poverty Orderings with Asymmetric Attributes

- Dictatorial Mechanisms in Constrained Combinatorial Auctions

- When Should a Monopolist Improve Quality in a Network Industry?

- On Partially Honest Nash Implementation in Private Good Economies with Restricted Domains: A Sufficient Condition

- Revenue Comparison in Asymmetric Auctions with Discrete Valuations