Abstract

Chemical investigation of an unknown marine sponge, which was collected in the Gulf of Aqaba (Jordan), afforded a new brominated alkaloid 3-amino-1-(2-amino-4-bromophenyl)propan-1-one (1), as well as 7-bromoquinolin-4(1H)-one (2) which had previously only been reported as a synthetic compound. In addition, caulerpin (6), previously only known to be produced by algae, was likewise isolated. Furthermore, three known alkaloids including (Z)-5-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)-hydantoin, (Z)-6-bromo-3′-deimino-2′,4′-bis(demethyl)-3′-oxoaplysinopsin, and 6-bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (3–5), were also obtained. All compounds were unambiguously elucidated based on extensive 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy, LCMS, as well as by comparison with the literature and tested for their cytotoxic activity toward the mouse lymphoma cell line L5178Y.

1 Introduction

The Gulf of Aqaba is one of the two northern branches of the Red Sea with a total length of 170 km, a width of 4–26 km, and a depth of up to 1830 m. It is located in a subtropical arid area between longitude 34°25′–35°00′E and latitude 28°00′–29°33′N [1]. The Jordanian coastline runs south for about 27 km from the most northern tip of the Gulf [2]. Waters of the Gulf of Aqaba are typically oligotrophic, with very low nutrient concentrations and a high biodiversity of the benthic community. The marine environment consists of a wealthy source of plants, animals, and microorganisms, which due to their adaptations to this unique habitat produce a wide variety of secondary metabolites, unlike those found in terrestrial species [3].

The majority of marine natural products currently used as drugs or in clinical trials are produced by invertebrates [4] such as sponges (Halaven®), tunicates (Yondelis®), mollusks (Adcetris®), and bryozoans (bryostatin 1) [5]. Ecologically, these bioactive metabolites are thought to protect sessile or soft bodied marine invertebrates from predators [6] or to fight off neighbors competing for space [7]. Sponges, members of the phylum Porifera, are the simplest and evolutionarily oldest living group of the Metazoa. Fossil records revealed that they first appeared during the Cambrian period, over 550 million years ago [8]. Sponges are important components of all modern coral reef communities. Their biomass and range of ecological tolerance frequently exceeds that of the coral reef building species. They have a considerable impact on the marine environment by effectively filtering large quantities of water, modifying the reef framework, and providing shelter for numerous species of fish and invertebrates [9–11]. Despite their simplicity, sponges are highly diverse and well-adapted organisms. They manage to adapt and survive longer than any other Metazoa [12]. Their successful evolution and wide distribution in modern reef habitats make them interesting for ecological and chemical studies alike.

Sponge-derived natural products, especially from the phylum Porifera, have been shown to be important sources of new lead structures for pharmaceutical products [5]. These natural products have a wide range of therapeutic properties, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, antihypertensive, anticoagulant, anticancer, antiinflammatory, wound healing and immune modulator, and other medicinal effects [13].

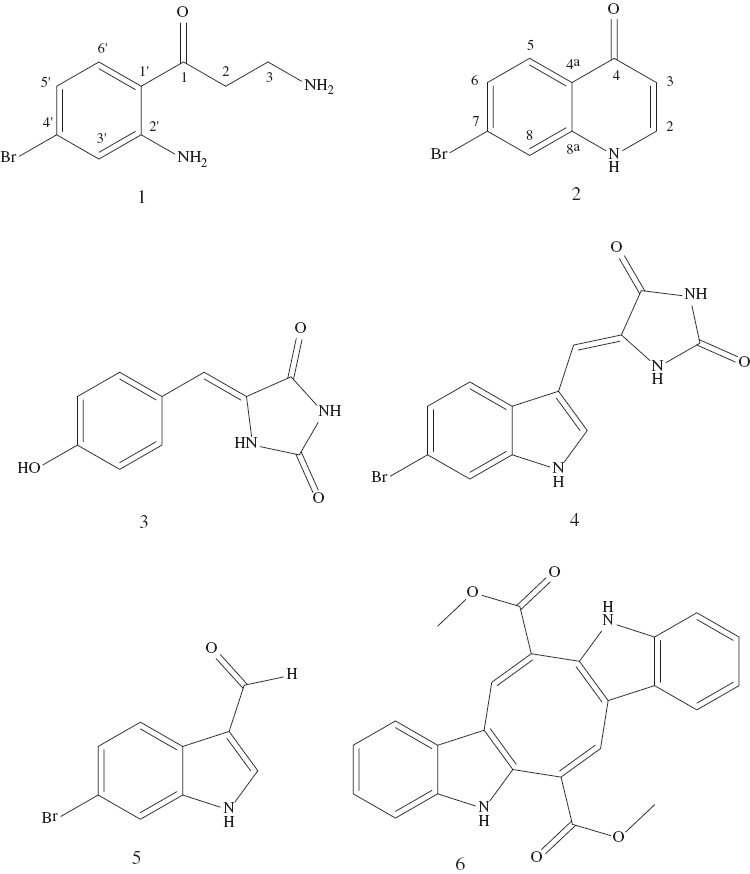

In this study, one new natural product, 3-amino-1-(2-amino-4-bromophenyl)propan-1-one (1), as well as 7-bromoquinolin-4(1H)-one (2), which was previously known only as a synthetic product, and caulerpin (6), which is described from sponge material here for the first time, together with three known compounds (3–5), are reported from an unknown sponge from the Gulf of Aqaba (Figure 1). The structural elucidation of the new natural products 1 and 2 is described.

Chemical structures of the isolated compounds 3-amino-1-(2-amino-4-bromophenyl)propan-1-one (1), 7-bromoquinolin-4(1H)-one (2), (Z)-5-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)-hydantoin (3), (Z)-6-bromo-3′-deimino-2′,4′-bis(demethyl)-3′-oxoaplysinopsin (4), 6-bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (5), and caulerpin (6).

2 Results and discussion

The sponge was chosen for analysis as it is taxonomically unknown and its extract inhibited growth (85% inhibition at a dose of 10 μg/mL) of the murine cancer cell line L5178Y. The methanol extract of the unknown sponge from the Jordanian coast of the Gulf of Aqaba was partitioned between ethyl acetate and water. The resulting ethyl acetate phase was fractionated by semipreparative reversed-phase HPLC to yield six compounds, 1–6.

Compound 1 was isolated as a yellowish amorphous solid. It showed UV absorbances at λmax (MeOH) 231.8, 268.4, and 361.2 nm. The HRESIMS showed an isotopic cluster of [M+H]+ ions in the ratio of 1:1 at m/z 243.0125 and 245.0105, indicating the molecular formula C9H12BrN2O with m/z 244.0153 [M+H]+.

The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 showed a doublet of doublets at δH 6.73 ppm (dd, J=1.9, 8.6 Hz) and two doublets at δH 7.63 ppm (d, J=8.6 Hz) and 6.99 ppm (d, J=1.9 Hz) assigned for H-5′, H-6′, and H-3′, respectively (ABX system). The signals of H-2 and H-3 were overlapping with the water signal. The 13C NMR and DEPT spectra revealed signals for two sp3 carbons (δC 36.7, 36.3 ppm) assigned for C-2 and C-3, respectively, and three sp2 carbon signals (δC 120.7, 119.3, 132.7 ppm) which were attributed to the aromatic carbons C-3′, C-5′, and C-6′ (Table 1).

1H and 13C NMR data and selected HMBC correlations of 1 in CD3OD (600 and 150 MHz); δ in ppm (J in Hz).

| 13C NMR | 1H NMR | HMBC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 CO | 199.7a | ||

| 2 CH2 | 36.7 | b | 1 |

| 3 CH2 | 36.3 | b | 1 |

| 1′ C | 116.6a | ||

| 2′ CNH2 | 154.0a | ||

| 3′ CH | 120.7 | 6.99,d (J=1.9) | 5′,4′,1′ |

| 4′ CBr | 130.8a | ||

| 5′ CH | 119.3 | 6.73,dd (J=1.9,8.6) | 1′,4′,3′ |

| 6′ CH | 132.7 | 7.63,d (J=8.6) | 1,5′,4′,2′,1′ |

aSignals deduced from HMBC. bOverlapped with the signal of water.

The deshielded signal of C-1 was observed at δC 199.7 ppm. The 1H1H COSY spectrum indicated a continuous spin system from H-3′ to H-6′. The structure of compound 1 was corroborated by analysis of the HMBC spectrum. H-2 and H-3 showed correlations to C-1, whereas H-6′ showed strong correlations with C-1 and C-4′, and a weaker correlation with C-5′ and C-1′. Furthermore, H-5′ showed correlations with C-3′ and C-1′. In addition, H-3′ showed strong correlations to C-5′ and C-1′ and a weaker correlation to C-4′, thus confirming the structure of 1. The assignment of the NH2 and Br substituents to C-2′and C-4′ was corroborated by the chemical shifts of the respective carbons at δC 154.0 ppm and δC 130.8 ppm (Table 1).

The remaining compounds (2–6) (Figure 1) were identified on the basis of their 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and mass spectrometric data and by comparison with published data as 7-bromoquinolin-4(1H)-one (2) (Table 2) [14], (Z)-5-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)-hydantoin (3) [15], (Z)-6-bromo-3′-deimino-2′,4′-bis(demethyl)-3′-oxoaplysinopsin (4) [16], 6-bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (5) [17], and caulerpin (6) [18]. Caulerpin (6) was isolated from a sponge for the first time in this study.

1H, 13C NMR data and selected HMBC correlations of 2 in CD3OD (600 and 150 MHz); δ in ppm (J in Hz).

| 13C NMRa | 1H NMR | HMBC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 CH | 123.5 | 7.99, d (J=7.3) | 4, 8a |

| 3 CH | 108.0 | 6.35, d (J=7.3) | 2, 4a, 8a |

| 4 CO | 177.9 | ||

| 5 CH | 124.6 | 8.15, d (J=8.7) | 8a |

| 6 CH | 133.2 | 7.55, dd (J=1.6, 8.7) | 4a, 8 |

| 7 CBr | 129.7 | ||

| 8 CH | 122.7 | 7.80, d (J=1.6) | 4a |

| 8a C | 140.0 | ||

| 4a C | 125.4 |

aSignals deduced from HMBC.

Comparison of the structures of compounds 1 and 2 indicates that these compounds are biogenetically closely related. Their skeleton may be derived from tryptophan via the kynurenine pathway, as 1 is a 4-bromo-derivative of the decarboxylated kynurenine and 2 a 7-bromo-derivative of kynurenic acid. Compound 1 furthermore shows resemblance with the 4-chloro-kynurenine residue of the recently isolated taromycin A from marine origin [19]. Interestingly, compounds 4–6 also appear to be derived from tryptophan, indicating the metabolism of this amino acid to be a prominent biogenetical pathway within this particular sponge.

All isolated compounds were tested for cytotoxic activity toward the lymphoma cell line LY1578 but proved to be inactive when tested at a concentration of 10 μg/mL each. Thus, the growth inhibition that was observed when testing the crude extract is probably due to other unkown compounds that were not isolated in this study.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 General

1H, 13C, and 2D NMR spectra were recorded in deuterated solvents on a Bruker Avance DRX-500 and a Bruker Avance III-600 NMR spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Karlsruhe, BW, Germany). LC-MS spectra were measured on an Agilent HP1100series (Agilent, Waldbronn, BW, Germany), and HR-MS experiments were carried out with a Bruker Daltonics maxis g4 TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, HB, Germany). HPLC analysis was performed with a Dionex UltiMate 3000 system coupled to a RS diode array detector (Thermo Fischer, Germering, BY, Germany). Detection was at λ 235, 254, 280, and 340 nm. The separation column (125×4 mm, Knauer, Berlin, BE, Germany) was prefilled with Eurosphere 100-5 C18. Semipreparative HPLC was performed on a HPLC system of Merck Hitachi (Pump L-7100 and UV detector L-7400 (Merck, Schwalbach, HE, Germany); column Eurosphere 100-10 C18, 300×8 mm, Knauer, Berlin, BE, Germany) with a flow rate of 5.0 mL/min. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel 60M (0.04–0.063 mm, Merck, Schwalbach, HE, Germany) or Sephadex LH-20 (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim am Albruch, BW, Germany) as stationary phases.

The chemicals used were of analytical grade (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim am Albruch, BW, Germany). The obtained spectroscopic data of the known compounds were concurrent with the reference data mentioned (supplementary data containing 1H and 13C NMR spectra, HPLC chromatograms, and UV spectra are available on request from the author for correspondence).

3.2 Sponge material

The sponge sample was collected at 20 m depth from the Jordanian coast of the Gulf of Aqaba by SCUBA diving, kept in an ice cooler until arrival at the Marine Science Station laboratory, and then immediately frozen at –80 °C. The sponge was transported under dry ice from Jordan to the Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany.

3.3 Extraction and isolation

The sponge (wet weight 300 g) was freeze-dried and cut into small pieces, followed by exhaustive extraction with methanol. The obtained crude extract amounted to 250 mg and was partitioned between ethyl acetate and water. The resulting ethyl acetate extraction was filtered and dried using a rotary evaporator. The dried extract was redissolved in methanol of analytical grade with the help of ultrasound and was then purified by semi-preparative reversed-phase HPLC. Applying a gradient elution from 5% MeOH/H2O*0.1%TFA to 100% MeOH and using a flow rate of 5 mL/min afforded 3-amino-1-(2-amino-4-bromophenyl)propan-1-one (1, 3.5 mg), 7-bromoquinolin-4(1H)-one (2, 1 mg), (Z)-5-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)-hydantoin (3, 1.8 mg), (Z)-6-bromo-3′-deimino-2′,4′-bis(demethyl)-3′-oxoaplysinopsin (4, 1.6 mg), 6-bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (5, 1.1 mg), and caulerpin (6, 1 mg), respectively.

3.3.1 3-Amino-1-(2-amino-4-bromophenyl)propan- 1-one (1)

Yellowish amorphous solid; UV (λmax, MeOH) (ε) 232, 268, 361 nm; 1H and 13C NMR data in methanol-d4, see Table 1; (+)-HRESIMS m/z 243/245, m/z 244.0153 [M+H]+ (calcd. for C9H12BrN2O, 243.0128).

All spectroscopic and spectrometric data are provided in the supporting information.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by a grant of the BMBF to P. P. is gratefully acknowledged. We wish to thank Dr. Daowan Lai from the Department of Plant Pathology of the College of Agronomy and Biotechnology, China Agricultural University, for his help in analysis of the NMR data. We further wish to thank the Marine Science Station, University of Jordan-Aqaba Branch-Jordan, for collecting the sponge samples, especially Prof. Dr. Tareq Al-Najjar and Khalid AlTrabeen.

References

1. Khalaf MA, Alawi M, Al-Zgool A, Al-Najjar T. Levels of trace metals in the bigeye houndshark Iago omanensis from the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea. Fresen Environ Bull 2013;22:3534–40.Search in Google Scholar

2. Hulings NC. A review of marine science research in the Gulf of Aqaba. Publication of the Marine Science Station Aqaba, Jordan. 1989;258:38–9. 6, 267.Search in Google Scholar

3. Costantino V, Fattorusso E, Menna M, Taglialatela-Scafati O. Chemical diversity of bioactive marine natural products: an illustrative case study. Curr Med Chem 2004;11:1671–92.10.2174/0929867043364973Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Eid ES, Abo Elmatty DM, Hanora A, Mesbah NM, Abou-El-Ela SH. Molecular and protein characterization of two species of the latrunculin-producing sponge Negombata from the Red Sea. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2011;56:911–5.10.1016/j.jpba.2011.07.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Gerwick WH. Lessons from the past and charting the future of marine natural products drug discovery and chemical biology. Chem Biol 2012;19:85–98.10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.12.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Proksch P, Edrada R, Ebel R. Drugs from the seas – current status and microbiological implications. Microbiol Biotechnol 2002;59:125–34.10.1007/s00253-002-1006-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Thakur NL, Müller WE. Marine medicinal foods: implication and application: animals and microbes. Curr Sci 2004;86:1506–12.Search in Google Scholar

8. Bergquist PR. Sponges. London: Hutchinson and Company, 1978:268.Search in Google Scholar

9. Reiswig HM. Particle feeding in natural populations of three marine demosponges. Biol Bull Mar Biol Lab Woods Hole 1971;141:568–91.10.2307/1540270Search in Google Scholar

10. Glynn PW. Aspects of the ecology of coral reef in the western Atlantic region. In: Jones OA, Endean R, editors. Biology and geology of coral reefs, vol. II: Biology 1. New York: Academic Press, 1973:271–324.10.1016/B978-0-12-395526-5.50017-1Search in Google Scholar

11. Rützler KS. Sponges in coral reefs. In: Stoddart DR, Johannes RE, editors. Coral reefs: research methods. Monographs in oceanographic methodology 5. Paris: UNESCO, 1978, 21:299–313.Search in Google Scholar

12. Hooper NA. Guide to sponge collection and identification. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. Biol Bull 1997;141: 568–91.Search in Google Scholar

13. Perdicaris S, Vlachogianni T, Valavanidis A. Bioactive natural substances from marine sponges: new developments and prospects for future pharmaceuticals. Nat Prod Chem Res 2013;1:3, 114.10.4172/2329-6836.1000114Search in Google Scholar

14. Al-Awadi NA, Abdelhamid IA, Al-Etaibi AM, Elnagdi HM. Gas-phase pyrolysis in organic synthesis: rapid green synthesis of 4-quinolinones. Synlett 2007;14:2205–8.10.1055/s-2007-985573Search in Google Scholar

15. Ha YM, Kim JA, Park YJ, Park D, Kim JM, et al. Analogs of 5-(substituted benzylidene)hydantoin as inhibitors of tyrosinase and melanin formation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1810:612–9.10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.03.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Guella G, Mancini I, Zibrowius H, Pietra F. Novel aplysinopsin-type scleractinian corals of the family Dendrophylliidae of the Mediterranean and the Philippines. Helv Chim Acta 1988;71:773–82.10.1002/hlca.19880710412Search in Google Scholar

17. Olguin-Uribe G, Abou-Mansour E, Boulander A, Debard H, Francisco C, Combaut G. 6-Bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde, from an Acinetobacter sp. bacterium associated with the Ascidian Stomozoa murrayi. J Chem Ecol 1997;23:2507–21.10.1023/B:JOEC.0000006663.28348.03Search in Google Scholar

18. Rocha FD, Soares AR, Houghton PJ, Pereira RC, Kaplan MA, Teixeira VL. Potential cytotoxic activity of some Brazilian seaweeds on human melanoma cells. Phytother Res 2007;21:170–5.10.1002/ptr.2038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Yamanaka K, Reynolds KA, Kersten RD, Ryan KS, Gonzalez DJ, Nizet V, et al. Direct cloning and refractoring of a silent lipopeptide biosynthetic gene cluster yields the antibiotic taromycin A. PNAS 2014;111:1957–62.10.1073/pnas.1319584111Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Essential oil composition, phenolic content, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of cultivated Satureja rechingeri Jamzad at different phenological stages

- Characterization of a mineral coating of the plant Dyerophytum indicum

- Semisynthesis and insecticidal activity of arylmethylamine derivatives of the neolignan honokiol against Mythimna separata Walker

- Dynamics of alkylresorcinols during rye caryopsis germination and early seedling growth

- New nitrogenous compounds from a Red Sea sponge from the Gulf of Aqaba

- Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of novel 5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-phenyl- 1H-benzimidazole derivatives

- Differential cytotoxic activity of the petroleum ether extract and its furanosesquiterpenoid constituents from Commiphora molmol resin

- A novel C25 sterol peroxide from the endophytic fungus Phoma sp. EA-122

- Bioactive compounds isolated from submerged fermentations of the Chilean fungus Stereum rameale

- Combined Autodock and comparative molecular field analysis study on predicting 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of flavonoids isolated from Spatholobus suberectus Dunn

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Essential oil composition, phenolic content, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of cultivated Satureja rechingeri Jamzad at different phenological stages

- Characterization of a mineral coating of the plant Dyerophytum indicum

- Semisynthesis and insecticidal activity of arylmethylamine derivatives of the neolignan honokiol against Mythimna separata Walker

- Dynamics of alkylresorcinols during rye caryopsis germination and early seedling growth

- New nitrogenous compounds from a Red Sea sponge from the Gulf of Aqaba

- Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of novel 5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-phenyl- 1H-benzimidazole derivatives

- Differential cytotoxic activity of the petroleum ether extract and its furanosesquiterpenoid constituents from Commiphora molmol resin

- A novel C25 sterol peroxide from the endophytic fungus Phoma sp. EA-122

- Bioactive compounds isolated from submerged fermentations of the Chilean fungus Stereum rameale

- Combined Autodock and comparative molecular field analysis study on predicting 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of flavonoids isolated from Spatholobus suberectus Dunn