Abstract

Satureja rechingeri is a rare endemic and endangered species found in Iran. Its propagation, variations in essential oil and phenolic content, as well as antioxidant and antimicrobial activities at different phenological stages are reported in this study. The chemical composition of essential oils obtained by hydro-distillation from the aerial parts were determined by GC and GC-MS. A total of 47 compounds were identified in the essential oils of S. rechingeri at different phenological stages. The major components of all oils were carvacrol (83.6%–90.4%), p-cymene (0.8%–2.9%) and γ-terpinene (0.6%–2.4%). The total phenolic content and the antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts were determined with the Folin-Ciocalteau reagent and by the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, respectively. Total phenols varied from 35.5 to 37.5 mg gallic acid equivalents/g dry weight (dw), and IC50 values in the radical scavenging assay ranged from 46.2 to 50.2 mg/mL, while those in the FRAP assay were between 49.6 and 52.5 μM quercetin equivalents/g dw. By the disc diffusion method and by determination of the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC), the essentials oils of the various phenological stages were found to have high activities against four medically important pathogens.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the essential oils and various extracts of medicinal and aromatic plants have gained great interest among researchers as sources of various natural products [1]. In this regard, the antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of these plants’ secondary metabolites have formed the basis of many applications, including raw and processed preservation, pharmaceuticals, alternative medicine, and natural therapies [2, 3].

The genus Satureja (Lamiaceae) constitutes about 200 species of herbs and shrubs, often aromatic, which are widely distributed in Mediterranean areas, Asia, and boreal America [4]. This genus is represented in the flora of Iran by 16 species, of which ten are considered endemic (Satureja atropatana Bunge. Saturejabachtiarica Bunge, Saturejaedmondi Briquet, Saturejaintermedia C.A.Mey, Satureja isophylla Rech., Saturejakallarica Jamzad, Saturejakhuzistanica Jamzad, S. macrosiphonia Bornm., Saturejasahendica Bornm., and Saturejarechingeri Jamzad). Satureja rechingeri is a rare and endemic Satureja species from Iran. This plant is a perennial and bushy aromatic herb that grows 50 cm high with yellow colored flowers, dense white villous hairs, and a dense covering of punctuate glands on both leaf surfaces. These plants grow in the rock walls and stony hillsides of Ilam province located in West Iran. Flowering occurs in autumn at late September and October [5].

The Satureja species contain some secondary metabolites, such as volatile oils, phenolic compounds, tannins, sugars, and fatty acids [6]. The aerial parts of some Satureja plants have been widely used in foods and herbal tea, as flavor components, and in folk and traditional medicine to treat various ailments, such as cramps, muscle pains, nausea, indigestion, diarrhea, and infectious diseases [7–9]. A previous literature review on essential oil composition in Satureja species showed that these are rich in terpenoids, such as carvacrol, γ-terpinene, thymol, p-cymene, β-caryophyllene, linalool, and other terpenoids. However, the chemical composition and the amount of components vary among and within the Satureja essential oils [10].

Essential oil constituents and secondary metabolites in medicinal and aromatic plants are strongly influenced by their origin, environmental conditions, ontogenetic variation [11, 12], management practices (e.g., harvest time), and ecological and climatic conditions [13]. Therefore, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and other biological activities may vary, based on the variations in chemical compositions of essential oils and the extracts of medicinal plants [14–16].

Endemism and limitation of the natural habitats in Iran, use for medicinal purposes, and increasing collection all lead to the reduction of the S. rechingeri populations in their natural habitats in Iran. The current study focuses on the possibility of S. rechingeri propagation and an investigation into the essential oil composition, phenolic content, as well as the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of this plant at different phenological stages. As far as we know, this is the first report on these properties of S. rechingeri. The results of this study can provide useful information about the propagation of this medicinal plant, and determine the suitable harvest time for obtaining the maximal amount of essential oil and secondary metabolites.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material

The cuttings of S. rechingeri were collected from plants grown in the wild in their natural habitat in Ilam province (between Mehran and Dehloran) in West Iran. A voucher specimen was deposited at the herbarium of medicinal and aromatic plants of Islamic Azad University, Estahban branch. The basal 2 cm of the cuttings were dipped into rooting powder containing indole butyric acid (IBA) to stimulate rooting. After hormone treatment, the cuttings were placed in a rooting medium containing sterilized river sand and then sprayed with water mist under greenhouse conditions. After about 3 months, the rooted cuttings were transferred to the Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Experimental Garden (MAPEG) of the Estahban branch, Islamic Azad University in Fars province in southwest Iran. Six months after transfer of the cuttings to the garden, the aerial parts of S. rechingeri were harvested at different phenological stages [pre-flowering (July), full-flowering (October), and post-flowering in seed set (November)]. The harvested plants in the three different phenological stages were dried at room temperature (25 °C) for 2 weeks, after which they were ground and powdered for essential oil extraction and further manipulation.

2.2 Essential oil isolation procedure

The powders (100 g) obtained above were subjected to hydrodistillation for 3 h using a Clevenger-type apparatus according to the method recommended in the British Pharmacopoeia [17]. The oils were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, weighed, and stored in tightly closed dark vials at 4 °C prior to analysis and antimicrobial tests.

2.3 Gas chromatography (GC)

GC analysis was performed with an Agilent Technologies gas chromatograph (Series II, Model 6990; Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector and an HP capillary column (30 m×0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film thickness). The chromatographic conditions were as follows: the oven temperature increased from 60 °C to 240 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min; the injector and detector temperatures were 240 °C and 250 °C, respectively; and helium was used as the carrier gas at a linear velocity of 32 cm/s. The samples were injected using the split sampling technique by a ratio of 1:20. The percentage compositions were obtained from electronic integration of peak areas without the use of correction factors.

2.4 Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

The analyses of the volatile compounds were carried out on a Hewlett-Packard GC-MS system (GC 6990 Series II, MSD 7890A; Palo Alto, CA, USA) operating at 70 eV ionization energy, equipped with an HP-5 capillary column with phenyl methyl siloxane (30 m×0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film thickness) with helium as the carrier gas and a split ratio of 1:20. The retention indices for all the components were determined according to the Van Den Doll method using n-alkanes as standard [18]. The compounds were identified by comparison of their retention indices (RRI-HP-5) with those reported in the literature and by comparison of their mass spectra with those in the Wiley and Mass Finder 3 libraries or with published mass spectra [19].

2.5 Preparation of methanolic extract

Ground shade-dried plant material (7.5 g) was defatted with petroleum ether for 3 h and then extracted twice for 24 h with 200 mL of 90% (v/v) aqueous methanol at room temperature. After filtration through Whatman filter paper (Whatman, Little Chalfont, UK), supernatants were combined and the solvent was evaporated to a volume of about 1 mL using a rotary evaporator. The concentrated extracts were freeze-dried and weighed for yield determination. The samples were stored for further experiments.

2.6 Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content was determined with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent as described previously [20]. Briefly, 200 μL of plant extract dissolved in methanol (1 mg/mL) were mixed with 2.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (diluted 10 times in distilled water) in glass tubes in triplicate. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 5 min and vortex-mixed at least twice. Then, 2 mL of 7.5% (w/v) Na2CO3 solution were added, and the glass tubes were incubated in the dark for 90 min with continuous shaking. The absorbance of samples was measured at 765 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV/VIS double beam PC.UVD.2980; Labomed, Los Angeles, CA, USA). Distilled water was used as blank. Different concentrations of gallic acid in methanol were tested in parallel to obtain a standard curve. Total phenolic contents were determined as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry weight (mg GAE/g dw).

2.7 Free radical scavenging capacity

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity was determined by the method of Brand-Williams et al. [21]. Briefly, four different concentrations of the plant extract dissolved in methanol were incubated with a 100-μM solution of DPPH in methanol in a total volume of 4 mL. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was recorded at 517 nm. Methanol was used as blank, and all measurements were carried out in triplicate. Quercetin was used as reference compound. All solutions were prepared daily. The percent inhibition of DPPH free radical was calculated using the following formula:

where Ablank is the absorbance of the control reaction (DPPH alone), and Asample is the absorbance of DPPH solution in the presence of the plant extract. The IC50 values denote the concentration of the sample required to scavenge 50% of DPPH free radicals.

2.8 Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The FRAP assay was performed as described previously by Benzie and Strain [22] and Firuzi et al. [23]. Briefly, the fresh FRAP solution was prepared by mixing 10 mL of acetate buffer (300 mM, pH 3.6), 1 mL of ferric chloride hexahydrate (20 mM) dissolved in distilled water, and 1 mL of 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) (10 mM) dissolved in 40 mM HCl. Plant extract dissolved in methanol (40 μL) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL was mixed with 4 mL of the FRAP solution. Absorbance was determined at 595 nm after 6 min of incubation at room temperature. Quercetin was tested at the final concentration of 10 μM and used as the reference compound. FRAP values, expressed as μmol quercetin equivalents per gram dry weight of plant material (μmol QE/g dw), were calculated according to the following formula:

where ΔAS and ΔAQ are absorbance changes of the FRAP solution in the presence of the sample plant extract and quercetin, respectively, and Y is the extraction yield.

2.9 Microorganisms

Standard strains of Candida albicans (ATCC 10231), the Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 1435), and the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichiacoli (ATCC 25922) were all obtained from the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology.

2.10 Determination of antimicrobial activity by the disk diffusion method

In vitro antimicrobial activities of the essential oils of S. rechingeri were evaluated by the disk diffusion method, with determination of inhibition zones (IZ), using Mueller-Hinton agar for bacteria (MHA) and Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) for fungi [24]. Disks containing 10 μL of essential oil were used, and diameters of inhibition zones were measured in millimeters after 24 h and 48 h of incubation at 37 °C and 24 °C for bacteria and fungi, respectively. All studies were performed in triplicate. Blank disks containing 10 μL DMSO were used as negative controls. Oxacillin (1 μg/disk), tetracycline (30 μg/disk), amoxicillin (10 μg/disk), ketoconazole (20 μg/disk), and gentamicine (30 μg/disk) were used as positive reference standards to determine the sensitivity of the microorganisms. A broth micro-dilution method was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards [25]. A serial double dilution of the oil was prepared in a 96-well micro-titer plate over the range of 0.02–50.00 μL/mL. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of the essential oil at which the microorganism does not demonstrate visible growth. All determinations were performed in triplicate.

2.11 Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Analysis of variance (ANOVE) was performed using the SAS software (version 9.2 for Windows). Significant differences between means were determined by Duncan’s new multiple-range test. Differences between means were considered significant at the level of p<0.05. Correlation analyses of antioxidant activity vs. the total phenolic content were carried out using the Microsoft Office Excel program. The IC50 values of the antioxidant activities were calculated by the software Curve Expert (version 1.3 for Windows).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Essential oil yield and composition

The yield and chemical composition of the essential oil of S. rechingeri and the retention indices are presented in Table 1. The essential oil obtained by hydrodistillation of the aerial parts of S. rechingeri, at different phenological stages, was found to be a yellow liquid, with yields ranging from 3.84% to 4.65% (w/w), based on dry weight. The highest and lowest oil yields were obtained in the full-flowering and pre-flowering stages, respectively. The comparison between our result and essential oil yields in all Satureja species showed that S. rechingeri had the highest oil yield among all Satureja species grown wild or cultivated in the world [10]. A total of 47 compounds were identified in the essential oils of S. rechingeri at different phenological stages. Oxygenated monoterpenes represented the main portion of all samples (Table 1). The major components of all the oils were found to be carvacrol (83.58%–90.35%), p-cymene (0.78%–2.85%), and γ-terpinene (0.56%–2.43%). Sefidkon et al. [26] reported that carvacrol (84%–89.3%), γ-terpinene (2.2%–2.3%), p-cymene (0.6%–2.4%), and limonene (0.2%–2.6%) were the main components of S. rechingeri essential oil, which were obtained by different distillation methods at full flowering stage.

Essential oil compositions of S. rechingeri at different phenological stages.

| No | Compound | RIa | Pre-flowering, % | Full-flowering, % | Post-flowering, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-Thujene | 925 | 0.12±0.02 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.03±0.01 |

| 2 | α-Pinene | 932 | 0.07±0.01 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.03±0.01 |

| 3 | Camphene | 947 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.02±0.001 |

| 4 | Sabinene | 971 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.06±0.02 |

| 5 | β-Pinene | 975 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 |

| 6 | 3-Octanone | 984 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 |

| 7 | Myrcene | 989 | 0.15±0.04 | 0.25±0.06 | 0.28±0.05 |

| 8 | 3-Octanonol | 993 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.01±0.001 | 0.02±0.01 |

| 9 | n-Decane | 998 | 0.02±0.001 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 |

| 10 | α-Phellandrene | 1004 | 0.05±0.01 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.03±0.01 |

| 11 | δ-3-Carene | 1010 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.02±0.001 | 0.03±0.01 |

| 12 | α-Terpinene | 1015 | 0.44±0.11 | 0.21±0.07 | 0.36±0.09 |

| 13 | p-Cymene | 1023 | 2.85± 0.45 | 0.78±0.12 | 1.67±0.12 |

| 14 | Limonene | 1026 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 |

| 15 | β-Phellandrene | 1027 | 0.11±0.03 | 0.05±0.01 | 0.05±0.02 |

| 16 | 1,8-Cineole | 1029 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.27±0.06 |

| 17 | Benzene acetaldehyde | 1041 | 0.01±0.001 | 0.01±0.001 | 0.03±0.01 |

| 18 | (E)-β-Ocimene | 1045 | 0.01±0.001 | 0.01±0.001 | 0.02±0.01 |

| 19 | γ-Terpinene | 1056 | 2.43±0.35 | 0.56±0.11 | 0.88±0.13 |

| 20 | cis-Sabinene hydrate | 1065 | 0.22±0.09 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.18±0.04 |

| 21 | Terpinolene | 1087 | 0.17±0.05 | 0.07±0.02 | 0.14±0.03 |

| 22 | Linalool | 1099 | 1.44±0.23 | 1.07±0.14 | 1.28±0.25 |

| 23 | n-Nonanal | 1103 | 0.08±0.02 | 0.16±0.05 | 0.27±0.08 |

| 24 | Borneol | 1164 | 0.14±0.03 | 0.11±0.03 | 0.08±0.02 |

| 25 | Terpinene-4-ol | 1176 | 1.34±0.25 | 1.04±0.14 | 1.12±0.33 |

| 26 | α-Terpineol | 1188 | 0.15±0.03 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.04±0.01 |

| 27 | n-Dodecane | 1197 | 0.09±0.02 | 0.16±0.03 | 0.23±0.08 |

| 28 | Carvacrol methyl ether | 1242 | 0.17±0.03 | 0.27±0.06 | 0.32±0.08 |

| 29 | Thymol | 1292 | 1.12±0.21 | 0.15±0.04 | 0.18±0.04 |

| 30 | Carvacrol | 1305 | 83.58±2.25 | 90.35±3.43 | 88.25±2.43 |

| 31 | α-Terpinyl acetate | 1347 | 0.65±0.14 | 0.43±0.11 | 0.23±0.08 |

| 32 | Eugenol | 1360 | 0.23±0.08 | 0.18±0.06 | 0.14±0.03 |

| 33 | Carvacrol acetate | 1375 | 0.11±0.03 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.14±0.04 |

| 34 | n-Tetradecane | 1399 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.08±0.02 |

| 35 | (Z)-Caryophyllene | 1406 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.01±0.001 | 0.04±0.02 |

| 36 | (E)-Caryophyllene | 1420 | 0.88±0.12 | 1.64±0.26 | 1.18±0.24 |

| 37 | trans-α-Bergamotene | 1435 | 0.05±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.06±0.02 |

| 38 | α-Humulene | 1452 | 0.27±0.05 | 0.17±0.03 | 0.19±0.06 |

| 39 | (E)-β-Farnesene | 1456 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.01±0.001 | 0.02±0.001 |

| 40 | β-Bisabolene | 1509 | 1.23±0.18 | 0.85±0.12 | 0.75±0.14 |

| 41 | (E)-γ-Bisabolene | 1537 | 0.41±0.07 | 0.23±0.07 | 0.33±0.10 |

| 42 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1581 | 0.33±0.06 | 0.25±0.05 | 0.15±0.04 |

| 43 | n-Hexadecane | 1598 | 0.12±0.02 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.04±0.02 |

| 44 | α-Bisabolol | 1682 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.08±0.03 |

| 45 | n-Octadecane | 1798 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.05±0.02 |

| 46 | 6,10,14-Trimethyl-2-pentadecanone | 1841 | 0.23±0.04 | 0.11±0.02 | 0.12±0.03 |

| 47 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | 1963 | 0.18±0.03 | 0.24±0.04 | 0.18±0.04 |

| Oil yield (%w/w) | 3.84 | 4.65 | 4.12 | ||

| Total | 99.60 | 99.03 | 99.45 |

aRI, retention indices in elution order from an HP-5 column. Each value in the table was obtained by calculating the average of three experiments±standard deviation. Data are expressed as percentages of the total values.

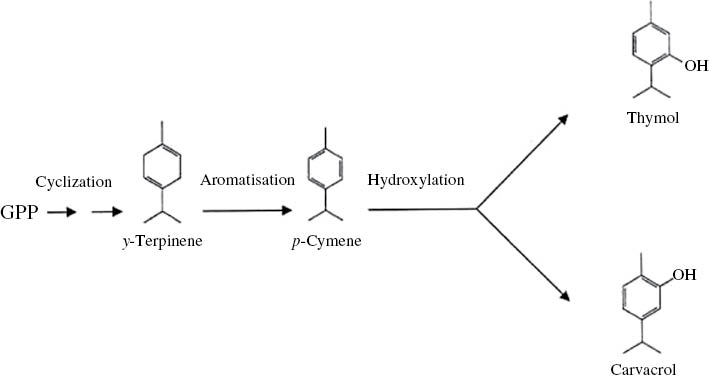

The highest carvacrol content (90.35%) was observed in the full-flowering stage and the lowest carvacrol content was observed in the pre-flowering stage (83.85%). At the full-flowering stage, the highest contents of phenolic compounds (carvacrol and thymol) and the lowest contents of their biosynthetic precursors (p-cymene and γ-terpinene) were observed, respectively, while the opposite was observed for the pre-flowering state (Table 2). The amounts of total carvacrol, thymol, and their precursors p-cymene and γ-terpinene, were the same and did not have significant differences at the three phenological stages (Table 2). Mikio and Taeko [27] and Yamaura et al. [28] proposed that the pathway of thymol and carvacrol biosynthesis includes γ-terpinene as the component involved in the aromatization process, resulting in the formation of p-cymene, the precursor of the oxygenated derivatives, thymol or carvacrol (Figure 1). It may be assumed that the sequence in this process is as follows: γ-terpinene, p-cymene, thymol or carvacrol. Our results are in agreement with those of Ozguven and Tansi [29] for Thymus vulgaris and Nejad Ebrahimi et al. [30] for Thymus carmanicus. These authors observed the maximum content of thymol, the major phenolic content, in the flowering stage, which then decreased in the post-flowering and seed set stages.

Thymol and carvacrol biosynthetic pathway according to Mikio and Taeko (1962). GPP: geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate.

Relative contents of phenolic terpenoids (carvacrol and thymol) and their precursors in the essential oils of S. rechingeri at different phenological stages.

| Harvesting times | Carvacrol, % | Thymol, % | p-Cymene, % | γ-Terpinene, % | Total, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- flowering | 83.58c | 1.12a | 2.58a | 2.43a | 89.71a |

| Full-flowering | 90.35a | 0.15b | 0.78c | 0.56c | 91.84a |

| Post-flowering | 88.25b | 0.18b | 1.67b | 0.88b | 90.98a |

aData are expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents per g dry weight (dw). bData are expressed as μg per milliliter. Lower IC50 values indicate the highest radical scavenging activity. Means with different letters were significantly different at the level of p<0.05. cData are expressed as (μmol quercetin equivalent/g dry weight) (DW). Each value in the table was obtained by calculating the average of three experiments. Values followed by the same letter in a vertical row under the same row, are not significantly different (p>0.05). Data are expressed as percentages of the total values.

3.2 Total phenolic content and antioxidant activity

The total phenolic content of the methanolic extracts of S. rechingeri harvested at different phenological stages was measured by the Folin-Ciocalteau reagent and expressed as GAE. According to Table 3, the total phenolic content increased slightly, but significantly, from the pre-flowering to the flowering stage, and then decreased slightly in the post-flowering stage, albeit not significantly. Thus, the total phenolic content is highest at the flowering and post-flowering stages.

Total phenolic content, radical scavenging activities, and FRAP values of methanolic extracts of S. rechingeri at different phenological stages.

| Harvesting time | Total phenolic contenta, mg GAE/g dw | Radical scavenging activity IC50b, μg/mL | FRAP valuec, μmol QE/g dw |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-flowering | 35.52±0.43b | 50.24±0.09d | 49.63±0.67b |

| Full-flowering | 37.48±0.58a | 46.22±0.23b | 52.45±0.58a |

| Post-flowering | 36.23±0.23a,b | 48.33±0.45c | 51.33±0.25a |

| Quercetin | ND | 36.54±0.45 | ND |

aData are expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents per g dry weight (dw). bData are expressed as μg per milliliter. Lower IC50 values indicate the highest radical scavenging activity. Means with different letters were significantly different at the level of p<0.05. cData are expressed as (μmol quercetin equivalent/g dry weight) (DW). Each value in the table was obtained by calculating the average of three experiments±standard deviation. Means with different letters were significantly different at the level of p<0.05. ND, not determined.

The antioxidant activities of the extracts of S. rechingeri were assessed by the DPPH free radical scavenging and FRAP methods. The DPPH assay determines the scavenging of stable radical species of DPPH by antioxidants [31], while the FRAP assay determines the capacity for reducing Fe(III) to Fe(II) [32]. As seen in Table 3, the extract from plants at the full-flowering stage was most effective in scavenging the DPPH radical, and it also had the highest FRAP value. Thus, the two assays complemented each other; furthermore, a correlation between the antioxidant activities and the total phenolic contents was revealed. These results suggest that the major part of the antioxidant activity in S. rechingeri results from the phenolic compounds. This is in line with the observation of other authors who found similar correlations between the total phenolic content and the antioxidant activity of various plants [12, 16, 33–36].

3.3 Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activities of S. rechingeri essential oils against three bacteria and one fungus were assessed by recording inhibition zones (IZ) and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC). Satureja rechingeri essential oils exhibited high antimicrobial activities against all four microorganisms tested, compared with the positive standard antibiotics (Table 4), the values of IZ and MIC being in the ranges of 61–71 mm and 0.19–0.39 mg/mL, respectively. No significant differences were observed between the antimicrobial activities of essential oils obtained at different phenological stages.

Antimicrobial activities of the essential oil of S. rechingeri under different phenological stages and standard antibiotics.

| Microorgaism | Harvesting times | Standard antibioticsc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-flowering | Full-flowering | Post-flowering | Oxa | Tet | Amox | Keto | Gen | ||||

| IZa | MICb | IZ | MIC | IZ | MIC | ||||||

| S. aureus | 62 | 0.39 | 68 | 0.19 | 64 | 0.39 | NA | 21 | 17 | NA | NA |

| S. epidermidis | 61 | 0.39 | 67 | 0.39 | 64 | 0.39 | 16 | 28 | 16 | 17 | NA |

| E. coli | 67 | 0.19 | 71 | 0.19 | 69 | 0.19 | NA | NA | 15 | NA | 24 |

| C. albicans | 66 | 0.19 | 71 | 0.19 | 68 | 0.19 | 21 | NA | NA | 23 | NA |

aDiameter of inhibition zones (mm) including diameter of sterile disk (6 mm). Essential oil was tested at 10 μL/disk for each tested microorganism. bMinimum inhibitory concentration, values as mg/mL. cOxa: oxacillin (1 μg/disk), Tet: tetracycline (30 μg/disk); Amox: amoxicillin (10 μg/disk); Keto: ketoconazol (20 μg/disk); Gen: gentamicine (30 μg/disk); (7–14), moderately active; (>14), highly active; NA, not active.

Recent studies on the essential oils of species of the Lamiaceae family have shown that most of these plants have a broad range of biological, notably antimicrobial, activities, which are generally related to the chemical composition of the oil [37]. Essential oils rich in phenolic compounds, such as carvacrol, have been widely reported to possess high levels of antimicrobial activity [38]. The antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of S. rechingeri can probably be attributed to high contents of their major components carvacrol, γ-terpinene, linalool, p-cymene, thymol, and others.

Several studies have focused on the antimicrobial activity of the essential oils and extracts of Satureja species, with the aim of identifying the responsible compounds [39, 40]. Carvacrol, which is the main component of S. rechingeri essential oil, is considered a biocide, producing bacterial membrane perturbations that lead to leakage of intracellular ATP and potassium ions and, ultimately, cell death [41, 42]. However, other components and the possible interaction between theses substances could also affect the antimicrobial activities. In fact, the antimicrobial activity of essential oils may well be the result of synergy, antagonism, or additive effects of their components, which possess various potencies of activity [43]. The antimicrobial properties of the essential oil of S. rechingeri indicate that the plant has potential for use in aromatherapy, pharmacy, and also in pathogenic systems to prevent the growth of microbes.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Estahban Branch of the Islamic Azad University Research and Technology Council for the financial support they provided for this work.

References

1. Evans WC. Trease and Evans’ pharmacognosy, 14th ed. London: Saunders, 1996:124–43.Search in Google Scholar

2. Reynolds JE. Martindale – the extra pharmacopeia, 31st ed. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1996.Search in Google Scholar

3. Lis-Balchin M. Deans SG. Bioactivity of selected plant essential oils against Listeria monocytogenes. J Appl Bacteriol 1997;82:759–62.10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00153.xSearch in Google Scholar

4. Cantino PD, Harley RM, Wagstaff SJ. Genera of labiatae: status and classification. In: Harley RM, Reynolds T, editors. Advances in labiatae science. Kew: Royal Botanical Gardens, 1992:511–22.Search in Google Scholar

5. Jamzad Z. Thymus and Satureja species of Iran. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization: Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands Publisher, 2010:171.Search in Google Scholar

6. Momeni DT, Shahrokhi N. Essential oil and their therapeutic actions (in Persian). Iran: Tehran University Publications, 1998.Search in Google Scholar

7. Gulluce M, Sokmen M, Daferera D, Agar G, Ozkan H, Kartal N, et al. In vitro antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities of the essential oil and methanol extracts of herbal parts and callus cultures of Satureja hortensis L. J Agri Food Chem 2003;51:3958–65.10.1021/jf0340308Search in Google Scholar

8. Madsen HL, Andersen L, Christiansen L, Brockhoff P, Bertelsen G. Antioxidative activity of summer savory (Satureja hortensis L.) and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) in minced, cooked pork meat. Food Res Technol 1996;203:333–8.10.1007/BF01231071Search in Google Scholar

9. Zargari A. In: Medicinal plants Vol. 4, Tehran: Tehran University Press, 1990:28–42.Search in Google Scholar

10. Niemeyer HM. Composition of essential oils from Satureja darwinii (Benth.) Briq. and S. multiflora (R. et P.) Briq. (Lamiaceae). Relationship between chemotype and oil yield in Satureja spp. J Essen Oil Res 2010;22:477–82.10.1080/10412905.2010.9700376Search in Google Scholar

11. Loziene K, Venskutonis PR. Influence of environmental and genetic factors on the stability of essential oil composition of Thymus pulegioides. Biochem Syst Ecol 2005;33:517–25.10.1016/j.bse.2004.10.004Search in Google Scholar

12. Alizadeh A. Essential oil constituents, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Salvia virgata Jacq. from Iran. J Essen Oil Bear Plants 2013;16:172–82.10.1080/0972060X.2013.793974Search in Google Scholar

13. Cabo J, Crespo ME, Jimenez J, Navarro C, Risco S. Seasonal variation of essential oil yield and composition of Thymus hyemalis. Planta Med 1982;53:380–2.10.1055/s-2006-962744Search in Google Scholar

14. Chorianopoulos N, Kalpoutzakis E, Aligiannis N, Mitaku S, Nychas GJ, Haroutounian S-A. Essential oils of Satureja, Origanum, and Thymus species: chemical composition and antibacterial activities against food borne pathogens. J Agri Food Chem 2004;52:8261–7.10.1021/jf049113iSearch in Google Scholar

15. Leung AY, Foster S. Encyclopedia of common natural ingredients used in foods, drugs, and cosmetics, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley, 1996:465–6.Search in Google Scholar

16. Alizadeh A, Alizadeh O, Amari G, Zare M. Essential oil composition, total phenolic content, antioxidant activity and antifungal properties of Iranian Thymus daenensis subsp. daenensis Celak. as influenced by ontogenetical variation. J Essen Oil Bear Plants 2013;16:59–70.10.1080/0972060X.2013.764190Search in Google Scholar

17. British pharmacopoeia. Vol. 2. British pharmacopoeia. London: HMSO, 1988:137–8.Search in Google Scholar

18. Van Den Dool H, Kratz PD. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas liquid partition chromatography. J Chromatography 1963;11:463.10.1016/S0021-9673(01)80947-XSearch in Google Scholar

19. Adams R. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/quadrupole mass spectroscopy. Carol Stream, USA: Allured Pub Corp, 1995:456.Search in Google Scholar

20. Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolic with phosphomolybdic- phosphotungestic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic 1965;16:144–58.10.5344/ajev.1965.16.3.144Search in Google Scholar

21. Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebenson Wiss Tech 1995;28:25–30.10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5Search in Google Scholar

22. Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Analytic Biochem 1996;239:70–6.10.1006/abio.1996.0292Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Firuzi O, Mladenka P, Riccieri V, Spadaro A, Petrucci R, Marrosu G, et al. Parameters of oxidative stress status in healthy subjects: their correlations and stability after sample collection. J Clinic Laborat Anal 2006;20:139–48.10.1002/jcla.20122Search in Google Scholar

24. Baron EJ, Finegold SM. Methods for testing antimicrobial effectiveness. In: Stephanie M, editor. Diagnostic microbiology. Baltimore: C.V. Mosby Co., 1990:171D194.Search in Google Scholar

25. NCCLS. NCCLS – National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. (2001), Performance standards for anti-microbial susceptibility testing: eleventh informational supplement. Document M100-S11. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standard, Wayne, PA, USA, 2001.Search in Google Scholar

26. Sefidkon F, Abbasi Kh, Jamzad Z, Ahmadi Sh. The effect of distillation methods and stage of plant growth on the essential oil content and composition of Satureja rechingeri Jamzad. Food Chem 2007;100:1054–8.10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.11.016Search in Google Scholar

27. Mikio Y, Taeko U. Biosynthesis of thymol. Chem Pharmaceu Bull 1962;10:71–2.Search in Google Scholar

28. Yamaura T, Tanaka S, Tabata M. Localization of the biosynthesis and accumulation of monoterpenoides in glandular trichomes of thyme. Planta Med 1992;58:153–8.10.1055/s-2006-961418Search in Google Scholar

29. Ozguven M, Tansi S. Drug yield and essential oil of Thymus vulgaris L. as influenced by ecological and ontogenetical variation. Tr J Agri Forest 1998;22:537–42.Search in Google Scholar

30. Nejad Ebrahimi S, Hadian J, Mirjalili MH, Sonboli A, Yousefzadi M. Essential oil composition and antibacterial activity of Thymus caramanicus at different phenological stages. Food Chem 2008;110:927–31.10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.083Search in Google Scholar

31. Othman A, Ismail A, Abdul Ghani N, Adenan I. Antioxidant capacity andphenolic content of cocoa beans. Food Chem 2007;100:1523–30.10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.12.021Search in Google Scholar

32. Firuzi O, Lacanna A, Petrucci R, Marrosu G, Saso L. Evaluation of the antioxidant activity of flavonoids by “ferric reducing antioxidant power” assay and cyclic voltammetry. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2005;1721:174–84.10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.11.001Search in Google Scholar

33. Alizadeh A, Khoshkhui M, Javidnia K, Firuzi OR, Tafazoli E, Khalighi A. Effects of fertilizer on yield, essential oil composition, total phenolic content and antioxidant activity in Satureja hortensis L. (Lamiaceae) cultivated in Iran. J Med Plan Res 2010;4:33–40.Search in Google Scholar

34. Alizadeh A, Khoshkhui M, Javidnia K, Firuzi OR, Jokar SM. Chemical composition of the essential oil, total phenolic content and antioxidant activity in Origanum majorana L. (Lamiaceae) cultivated in Iran. Adv Envir Bio 2011;5:2326–31.Search in Google Scholar

35. Javanmardi J, Stushnoff C, Locke E, Vivanco JM. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of Iranian Ocimum accessions. Food Chem 2003;83:547–50.10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00151-1Search in Google Scholar

36. Nencini C, Cavallo F, Capasso A, Franchi GG, Giorgio G, Micheli L. Evaluation of antioxidative properties of Allium species growing wild in Italy. Phytother Res 2007;21:874–8.10.1002/ptr.2168Search in Google Scholar

37. Baratta MT, Dorman HJ, Deans S, Figueiredo AC, Barroso JG, Ruberto G. Antibacterial and anti-oxidant properties of some commercial essential oils. Flav Frag J 1998;13: 235–44.10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(1998070)13:4<235::AID-FFJ733>3.0.CO;2-TSearch in Google Scholar

38. Baydar H, Sagdic O, Ozkan G, Karadogan T. Antimicrobial activity and composition of essential oils from Origanum, Thymbra and Satureja species with commercial importance in Turkey. Food Control 2004;15:169–72.10.1016/S0956-7135(03)00028-8Search in Google Scholar

39. Ciani M, Menghini L, Mariani F, Pagiotti R, Menghini A, Fatichenti F. Antimicrobial properties of essential oil of Satureja montana L. on pathogenic and spoilage yeasts. Biotech Lett 2000;22:1007–10.10.1023/A:1005649506369Search in Google Scholar

40. Azaz D, Demirci F, Satil F, Kurkcuoglue M, Baser KH. Antimicrobial activity of some Satureja essential oil. Z. Naturforsch C: Biosci 2002;5:817–21.10.1515/znc-2002-9-1011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Juven BJ, Kanner J, Schued F, Weisslowicz H. Factors that interact with the antibacterial action of thyme essential oil and its active constituents. J Appl Bacteriol 1994;76:626–31.10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb01661.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Ultee A, Kets EP, Smid EJ. Mechanisms of action of carvacrol on the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999;65:4606–10.10.1128/AEM.65.10.4606-4610.1999Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Didry N, Dubreuil L, Pinkas M. Antibacterial activity of thymol, carvacrol and cinnamaldehyde alone or in combination. Pharmazie 1993;48:301–4.Search in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Essential oil composition, phenolic content, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of cultivated Satureja rechingeri Jamzad at different phenological stages

- Characterization of a mineral coating of the plant Dyerophytum indicum

- Semisynthesis and insecticidal activity of arylmethylamine derivatives of the neolignan honokiol against Mythimna separata Walker

- Dynamics of alkylresorcinols during rye caryopsis germination and early seedling growth

- New nitrogenous compounds from a Red Sea sponge from the Gulf of Aqaba

- Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of novel 5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-phenyl- 1H-benzimidazole derivatives

- Differential cytotoxic activity of the petroleum ether extract and its furanosesquiterpenoid constituents from Commiphora molmol resin

- A novel C25 sterol peroxide from the endophytic fungus Phoma sp. EA-122

- Bioactive compounds isolated from submerged fermentations of the Chilean fungus Stereum rameale

- Combined Autodock and comparative molecular field analysis study on predicting 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of flavonoids isolated from Spatholobus suberectus Dunn

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Essential oil composition, phenolic content, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of cultivated Satureja rechingeri Jamzad at different phenological stages

- Characterization of a mineral coating of the plant Dyerophytum indicum

- Semisynthesis and insecticidal activity of arylmethylamine derivatives of the neolignan honokiol against Mythimna separata Walker

- Dynamics of alkylresorcinols during rye caryopsis germination and early seedling growth

- New nitrogenous compounds from a Red Sea sponge from the Gulf of Aqaba

- Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of novel 5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-phenyl- 1H-benzimidazole derivatives

- Differential cytotoxic activity of the petroleum ether extract and its furanosesquiterpenoid constituents from Commiphora molmol resin

- A novel C25 sterol peroxide from the endophytic fungus Phoma sp. EA-122

- Bioactive compounds isolated from submerged fermentations of the Chilean fungus Stereum rameale

- Combined Autodock and comparative molecular field analysis study on predicting 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of flavonoids isolated from Spatholobus suberectus Dunn