Abstract

The mineral coating of Dyerophytum indicum Kuntze (Plumbaginaceae) was analyzed by isotope ratio mass spectrometry, X-ray diffraction, thermogravimetric and differential thermal analysis, and scanning electron microscopy/energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy methods. Its composition was found to be similar to those of the carbonate mixtures isolated from rotting cacti and speleothems. The coating consisted of three major phases (monohydrocalcite, nesquehonite, and calcite), a minor phase of hydromagnesite, and traces of silica and sylvite. This is the first time that the occurrence of monohydrocalcite, nesquehonite, and hydromagnesite in a living higher plant has been reported. A possible mechanism of the formation of the coating is also discussed.

1 Introduction

Dyerophytum indicum Kuntze (Arabic: ‘mellah’ or salty) belongs to the Plumbaginaceae family. It is an erect shrub up to 2 m tall, and is distributed throughout the Arabian Peninsula and Western India. In Oman, it is a common plant of wadis (desert and mountain erosion valleys of intermittent streams) at altitudes of up to 1800 m [1].

The leaves of D. indicum are covered with friable white mineral coating (Figure 1) which has been described in the literature as a mere salt, even usable for cooking (see e.g. [1]). However, based on our own experience in the field, the coating is tasteless, insoluble in water, and contains carbonates. The apparent discrepancy of the mineral composition with that reported in the literature led us to perform an initial chemical characterization of this coating.

D. indicum: Whole plant (top) and close-up of leaves (bottom), with visible whitish mineral coating (scales are approximate).

2 Materials and methods

The samples of mineral coating from the leaves of D. indicum were collected from two sites in the Sultanate of Oman: the water-bearing floor of Wadi Muaiden (N23° 0.0′; E57° 39.5′), and from a wadi near Muscat (N23° 27.7′; E58° 20.5′), in December 2010. Average daily temperatures at the time of collection ranged from +15 °C to +27 °C. The coating was separated from the leaf surface with a soft brush, and did not undergo any further treatment to avoid solid phase reactions. The analyses were performed within a week from the collection of samples.

Isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) analysis of 13C and 18O was done on a GVI Isoprime dual inlet stable isotope mass spectrometer (GV Instruments, Manchester, UK) interfaced with a Multiprep sample preparation system. Measurements were calibrated against Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) and Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) reference standards (IAEA, Vienna, Austria). Raw δ values for oxygen were further adjusted for carbonate acid fractionation factors and converted to the VPDB scale as described previously [2].

Powder X-ray analysis was performed on a PW1710 diffractometer (Philips Analytical, Almelo, The Netherlands); scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analyses were performed on a JED-2300 energy dispersive X-ray analyzer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Thermal analyses were done on an SDT 2960 thermogravimetric analyzer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA), under nitrogen gas and with a heating rate of 10 °C min–1.

3 Results

The phase composition of the D. indicum mineral coating was determined from two different samples by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The first XRD test (not shown) revealed six inorganic phases in the coating: calcite (CaCO3 trigonal), 45 wt.%; aragonite (CaCO3 orthorhombic), 2 wt.%; monohydrocalcite (CaCO3·H2O), 12 wt.%; dolomite [CaMg(CO3)2], 3 wt.%; nesquehonite (Mg(HCO3)(OH)·2H2O, according to [3]), 38 wt.%; and traces of silica.

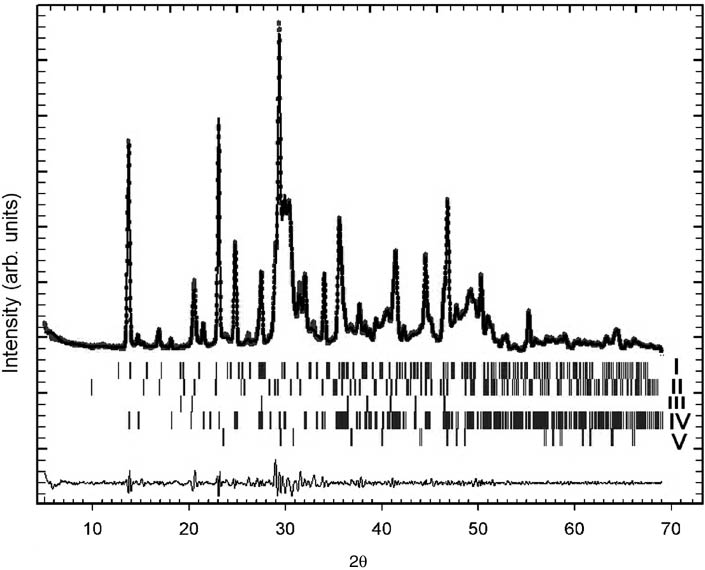

To rectify these results, we repeated the analysis with Rietveld refinement, as implemented in the FullProf program [4]. The best fit to the experimental data (Figure 2) was reached when the phases of monohydrocalcite, nesquehonite, and calcite were combined with lansfordite (MgCO3·5H2O) and hydromagnesite [Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·4H2O]. However, the inclusion of dolomite or aragonite did not improve the refinement, so the presence of these minerals in the coating remains to be confirmed.

Rietveld plot of D. indicum mineral coating.

The upper trace shows the observed data as dots overlaid with the calculated pattern (solid line). The lower trace is the difference plot between the observed and calculated pattern. The vertical markers show the positions calculated for Bragg reflections for the following phases: I, MgCO3·5H2O; II, CaCO3.H2O; III, Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2.4H2O; IV, Mg(HCO3)(OH)·2H2O; V, CaCO3 (calcite).

We performed IRMS analysis for 13C/12C and 18O/16O isotope ratios in the mineral phase collected from two plant specimens, and compared the results with those obtained for wadi water evaporite, surrounding mineral dust and calcareous rocks, as well as with literature data on atmospheric CO2 (Table 1). The concentration of either 13C or 18O in the coating was higher than in any possible environmental carbonate source, which suggested the involvement of the plant in the formation of the mineral.

Delta values (δ) for 13C and 18O ratios for two samples of D. indicum coating, wadi water evaporite, local mineral dust, and calcite rocks (VPDB scale).

| δ, Plant 1 | δ, Plant 2 | δ, Plant (average) | δ, Water evaporite | δ, Mineral dust | δ, Calcite rock | δ, CO2, atmospheric [2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C | 3.71 | 4.96 | 4.34 | −1.39 | 1.4 | 2.78 | −7.5 |

| 18O | 15.85 | 16.99 | 16.42 | −4.70 | −2.71 | −1.16 | 6.9 |

To estimate the lifetime of the mineral coating on a living plant, the following experiment was performed. Two neighboring D. indicum plants were selected. On both plants, the coating was carefully removed from a few leaves using water and brush. Simultaneously, on a few other leaves, the existing coating was marked with a food colorant. The site was then visited regularly, over the course of 10 days, to check the state of the leaves. By the end of the experiment, we observed neither the formation of new mineral nor the disappearance of the marked mineral. Therefore, the residence time of the mineral on the plant must be more than 10 days, and the week elapsing between sample collection and XRD analysis should have not influenced its composition significantly. It has been reported previously that the XRD analysis of lansfordite could be successfully completed only with a fresh sample of the mineral [5], as it readily dehydrates into an X-ray amorphous substance. Consequently, despite an improvement in XRD refinement upon the inclusion of lansfordite phase, a prolonged residence of the coating on the plant made the presence of this mineral unlikely.

The EDS analysis of the coating (Supplement A) confirmed the presence of the elements from the phases identified by XRD analysis, i.e., Ca, Mg, C, and O. In some cases, such as in plates e–h of Suppl. A, the spectrum also exhibited peaks of K together with Cl, indicating the presence of KCl, most likely in the form of sylvite mineral. The EDS image on plate g of Suppl. A showed silica traces, which were also detected in the initial XRD test. The samples of coating were not treated chemically before analysis, so the possibility of contamination could be excluded. There is at least one previous report on sylvite and silica as products of plant biomineralization in Tradescantia pallida [6].

Based on the critical analysis of XRD and EDS data, the composition of D. indicum mineral coating can be best described as having three major mineral phases: monohydrocalcite (∼13 wt.%), nesquehonite (∼38 wt.%), and calcite (∼45 wt.%); a minor hydromagnesite phase; and traces of silica and sylvite. The presence of lansfordite, aragonite and dolomite, though possible, requires additional experimental evidence.

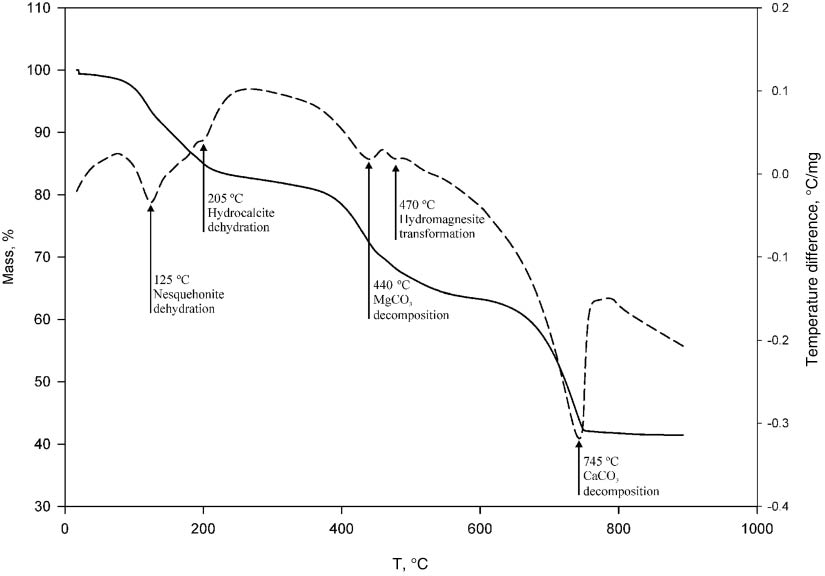

The plot of the TGA and DTA analyses (Figure 3) revealed three pronounced endotherms, which correspond to the dehydration of nesquehonite to magnesite (MgCO3) at 125 °C, followed by decomposition of the latter at 440 °C, and the decomposition of calcite at 745 °C [7]. The DTA curve does not contain the exotherm at 510 °C, which is typical for the decomposition of hydromagnesite [7]. The absence of this peak indicates that nesquehonite dehydrates directly to magnesite. A small endotherm at ca. 470 °C is close to the temperature of the decarbonization of hydromagnesite [8], and a similar endotherm at 205 °C fits best with the reported dehydration of monohydrocalcite at 171 °C–206 °C [9].

Thermogravimetric (TG, solid line) and differential thermal analysis (DTA, dashed line) curves of D. indicum mineral coating.

4 Discussion

A positive value of δ13C in biogenic carbonates has been reported previously, but only for a few species of benthic algae [2]. Moreover, the δ13C of the D. indicum mineral coating is unusually large by magnitude, and is comparable only to that of calcareous sediments associated with seagrasses [10]. In the latter case, 13C enrichment of the sediments had been attributed to repetitive cycles of dissolution and re-precipitation of carbonates from brine in isolated pores. A comparably large isotope fractionation has also been observed in a chemical system when calcite precipitated concurrently with monohydrocalcite [11]. The reported δ13C and δ18O values for monohydrocalcite and calcite in decaying saguaro [5] are much lower than in D. indicum coating.

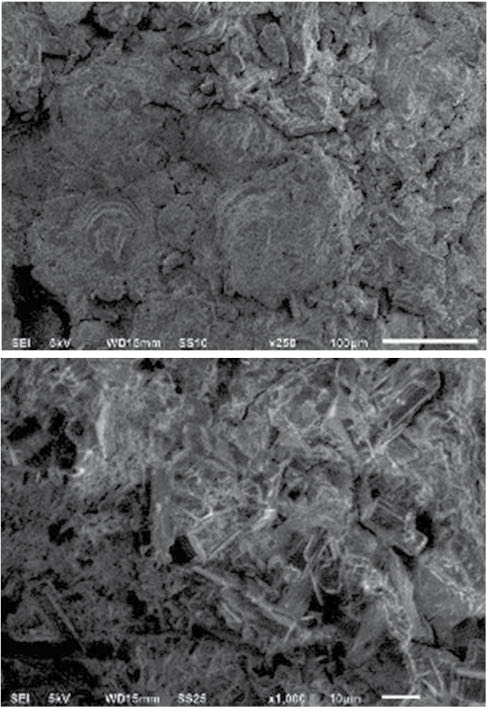

The composition of the D. indicum coating bears a number of typical features of biomineralization as well as some uncommon ones. Almost the same combination of minerals has been observed in speleothems, i.e., cave mineral deposits [12, 13]. The microscopic morphology of the coating is also somewhat similar to that of the described speleothem formations in that it consists of ‘knobs’ formed by microcrystalline concentrical layers of carbonates (Figure 4).

SEM of mineral coating of D. indicum: general morphology of calcareous ‘knobs’ (top), and nesquehonite prismatic crystals embedded in the mineral matrix (bottom).

The major component of the coating, calcite, is a frequent biogenic mineral in animals, but is seldom seen in plant tissues. The remarkable, albeit sparse, examples of higher plant calcification are cystoliths in the leaves of some plant families [14, 15], rhizoliths, i.e. formations of calcareous cementation on the surface of roots [16, 17]. There are also reports for Cactaceae as well as for some algae, fungi, and bryophytes [18, 19].

Aragonite is a metastable phase of calcium carbonate, but its transformation to calcite is negligibly slow and may take up to thousands of years [20] under normal conditions. Therefore, it cannot be considered as a transient mineral on a pathway leading to calcite, and if any aragonite had been formed by the plant, it should have remained as such in the coating. There are at least two chemical mechanisms facilitating aragonite crystallization from complex carbonate mixtures: either through partial monohydrocalcite dehydration in a wet atmosphere [21], or in the presence of elevated concentrations of Mg2+ [22]. The nesquehonite content of the coating indicates significant amounts of magnesium in the plant exudates; however, calcium carbonate is presumably present as calcite rather than aragonite. The absence of aragonite from the coating suggests that there are no conditions favoring its formation during plant mineralization.

The magnesium carbonates nesquehonite and lansfordite (MgCO3·5H2O) have previously been found in decomposing saguaro [5], but neither of them is formed in the living plant. In decaying saguaro, nesquehonite was the most abundant mineral. Similarly, in D. indicum, the nesquehonite content (38%) is high but not as high as that of calcite (45%). To our knowledge, there are no other published cases of magnesium carbonates formed by plants. These minerals form in the presence of hydrocarbonate anions and magnesium cations, producing primarily lansfordite at below +4 °C, or nesquehonite at higher temperatures [5, 23]. Hydromagnesite [Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·4H2O] can precipitate from solution at either high temperatures (above 52 °C) or at lower temperatures in the presence of bacteria [13, 24–27]. It is also a metastable phase, which can be transformed into more stable dolomite in the presence of Ca2+ [27]. The average daily temperatures at the time of the formation of the mineral samples studied in the present work (15 °C –27 °C) were far below 52 °C required for the purely chemical precipitation of hydromagnesite. This points to the involvement of the plant in this process. The absence of dolomite and aragonite from the samples, together with the major presence of nesquehonite and calcite, allows us to hypothesize that the plant exudate changes its composition periodically. It might contain high concentrations of either Ca2+ or Mg2+, but not both simultaneously. An indirect indicator of such periodical changes is the layered structure of the coating (Figure 4).

Another component of the coating, monohydrocalcite, is a common satellite mineral of nesquehonite [21]. This couple of minerals has also been found in rotten saguaro [5] and in limestone caves [13].

An uncommon feature of the coating is that it does not contain oxalates, the widespread products of plant biomineralization. Specifically, oxalate crystals are often observed in desert plants [5, 18, 28], and in association with calcite cystoliths [15]. A possible explanation could be that leaf surface-associated microorganisms participate in mineral formation. The oxalate anion could either be degraded by these microorganisms into the carbonate, or not formed at all. There are numerous reports on the complex production of dolomite, monohydrocalcite, calcite, and aragonite in the presence of microorganisms [26, 27, 29, 30]. Regarding this, in some of the SEM images (plates c, g in Suppl. A) we have observed filamentous fragments, similar to those of cyanobacteria or fungal hyphae, but their actual origin has not been determined.

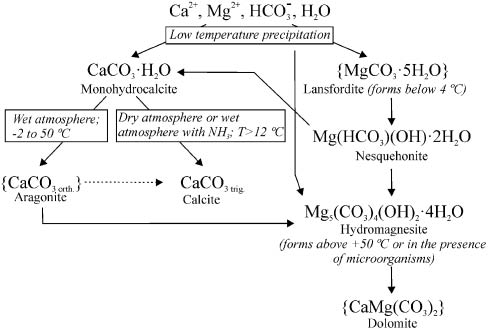

Based on our data and those that have been previously published, we suggest the following scheme for D. indicum biomineralization (Figure 5). First, the plant produces an exudate with elevated concentrations of calcium or magnesium, and hydrocarbonate. If the major cation is Ca2+, monohydrocalcite precipitates first, according to the mechanism suggested by Fischbeck and Müller [13], which leads to an increased Mg2+/Ca2+ ratio. This ratio facilitates the precipitation of nesquehonite (or lansfordite at low temperatures) and small amounts of aragonite; moreover, Marschner reports that contact with air is essential for monohydrocalcite formation [21]. When brine contained high concentrations of Mg2+, the major precipitate was nesquehonite, in the same proportion as in the D. indicum mineral coating, i.e., 38%. Monohydrocalcite then gradually dehydrates either to calcite or to aragonite [31]. Aragonite forms in wet atmosphere, at temperatures ranging from −2 °C to +50 °C. In dry atmosphere, or in wet atmosphere containing ammonia, the major product of dehydration is calcite [21]. Further maturation of the mineral mixture might involve such reactions as transformation of nesquehonite to hydromagnesite [24], dissolution of nesquehonite in the exudate and subsequent crystallization of monohydrocalcite and dolomite [25], and repetitive recrystallization of the participating mineral phases leading to heavy isotope enrichment [11].

Hypothetical scheme of the formation of the D. indicum mineral coating.

Curly brackets indicate questionable species, lacking experimental observation. Dashed arrow: aragonite-calcite phase transition, very slow at ambient conditions.

The total water content of the coating, according to the TGA analysis is 18%. This water could be important for the plant during drought periods. In addition, the coating can accumulate water both mechanically and chemically, absorbing the morning dew and forming crystallohydrates. In either case, the formation of a set of water bearing minerals could be advantageous for a desert plant like D. indicum.

Overall, the discovered case of plant biomineralization is highly unusual, both with respect to the mineral phase and isotopic compositions. The mineral mixture resembles mostly the product expected from a physical crystallization of a mixed cation carbonate solution. However, its isotopic content strictly calls for the participation of the host plant in the process.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Giles Edwards (University of Nizwa, Oman), Dr. Daniel Snow (University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA), and Dr. Hendrikus Reerink (Petroleum Development Oman) for their technical assistance.

References

1. Pickering H, Patzelt A. Field guide to the wild plants of Oman. Kew: Kew Pub, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

2. Sharp Z. Principles of stable isotope geochemistry, 1st ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

3. Hales M, Frost R, Martens W. Thermo-Raman spectroscopy of synthetic nesquehonite – implication for the geosequestration of greenhouse gases. J Raman Spectr 2008;39:1141–9.10.1002/jrs.1950Search in Google Scholar

4. Pecharsky VK, Zavalij PY. Fundamentals of powder diffraction and structural characterization of materials, 2nd ed. New York: Springer, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

5. Garvie L. Decay-induced biomineralization of the saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea). Am Mineral 2003;88:1879–88.10.2138/am-2003-11-1231Search in Google Scholar

6. Brizuela M, Montenegro T, Carjuzaa P, Maldonado S. Insolubilization of potassium chloride crystals in Tradescantia pallida. Protoplasma 2007;231:145–9.10.1007/s00709-007-0258-7Search in Google Scholar

7. Lanas J, Alvarez J. Dolomitic lime: thermal decomposition of nesquehonite. Thermochim Acta 2004;421:123–32.10.1016/j.tca.2004.04.007Search in Google Scholar

8. Hollingbery L, Hull T. The thermal decomposition of huntite and hydromagnesite – a review. Thermochim Acta 2010;509:1–11.10.1016/j.tca.2010.06.012Search in Google Scholar

9. Neumann M, Epple M. Monohydrocalcite and its relationship to hydrated amorphous calcium carbonate in biominerals. Eur J Inorg Chem 2007;2007:1953–7.10.1002/ejic.200601033Search in Google Scholar

10. Hu X, Burdige DJ. Enriched stable carbon isotopes in the pore waters of carbonate sediments dominated by seagrasses: evidence for coupled carbonate dissolution and reprecipitation. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2007;71:129–44.10.1016/j.gca.2006.08.043Search in Google Scholar

11. Jiménez-López C, Caballero E, Huertas FJ, Romanek CS. Chemical, mineralogical and isotope behavior, and phase transformation during the precipitation of calcium carbonate minerals from intermediate ionic solution at 25°C. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2001;65:3219–31.10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00672-XSearch in Google Scholar

12. Broughton P. Monohydrocalcite in speleothems: an alternative interpretation. Contr Mineral and Petrol 1972;36:171–4.10.1007/BF00371187Search in Google Scholar

13. Fischbeck R, Müller G. Monohydrocalcite, hydromagnesite, nesquehonite, dolomite, aragonite, and calcite in speleothems of the Fränkische Schweiz, Western Germany. Contr Mineral Petrol 1971;33:87–92.10.1007/BF00386107Search in Google Scholar

14. Gal A, Brumfeld V, Weiner S, Addadi L, Oron D. Certain biominerals in leaves function as light scatterers. Adv Materials 2012;24:77–83.10.1002/adma.201104548Search in Google Scholar

15. Setoguchi H, Okazaki M, Suga S. Origin, evolution, and modern aspects of biomineralization in plants and animals. In: Crick R, editors. New York: Springer, 1989:409–18.10.1007/978-1-4757-6114-6_32Search in Google Scholar

16. Klappa CF. Rhizoliths in terrestrial carbonates: classification, recognition, genesis and significance. Sedimentology 1980;27:613–29.10.1111/j.1365-3091.1980.tb01651.xSearch in Google Scholar

17. Mount JF, Cohen AS. Petrology and geochemistry of rhizoliths from Plio-Pleistocene fluvial and marginal lacustrine deposits, east Lake Turkana, Kenya. J Sed Res 1984;54:263–75.10.1306/212F83FA-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865DSearch in Google Scholar

18. Monje PV, Baran EJ. Complex biomineralization pattern in cactaceae. J Plant Physiol 2004;161:121–3.10.1078/0176-1617-01049Search in Google Scholar

19. Pentecost A. Calcification in plants. Int Rev Cytol 1980;62:1–27.10.1016/S0074-7696(08)61897-5Search in Google Scholar

20. Budd DA. Aragonite-to-calcite transformation during fresh-water diagenesis of carbonates: insights from pore-water chemistry. Geol Soc America Bull 1988;100:1260–70.10.1130/0016-7606(1988)100<1260:ATCTDF>2.3.CO;2Search in Google Scholar

21. Marschner H. Hydrocalcite (CaCO3·H2O) and nesquehonite (MgCO3·3H2O) in carbonate scales. Science 1969;165:1119–21.10.1126/science.165.3898.1119Search in Google Scholar

22. Munemoto T, Fukushi K. Transformation kinetics of monohydrocalcite to aragonite in aqueous solutions. J Min Petr Sci 2008;103:345–9.10.2465/jmps.080619Search in Google Scholar

23. Ming DW, Franklin WT. Synthesis and characterization of lansfordite and nesquehonite. Soil Sci Soc Am J 1985;49:1303–8.10.2136/sssaj1985.03615995004900050046xSearch in Google Scholar

24. Davies PJ, Bubela B. The transformation of nesquehonite into hydromagnesite. Chem Geol 1973;12:289–300.10.1016/0009-2541(73)90006-5Search in Google Scholar

25. Davies PJ, Bubela B, Ferguson J. Simulation of carbonate diagenetic processes: formation of dolomite, huntite and monohydrocalcite by the reactions between nesquehonite and brine. Chem Geol 1977;19:187–214.10.1016/0009-2541(77)90015-8Search in Google Scholar

26. Rivadeneyra M, Delgado R, Parraga B, Ramos-Cormenzana A, Delgado G. Precipitation of minerals by 22 species of moderately halophilic bacteria in artificial marine salts media: influence of salt concentration. Folia Microbiol 2006;51:445–53.10.1007/BF02931589Search in Google Scholar

27. Sanchez-Roman M, Romanek C, Fernandez-Remolar D, Sanchez-Navas A, McKenzie J, Pibernat R, et al. Aerobic biomineralization of Mg-rich carbonates: implications for natural environments. Chem Geol 2011;281:143–50.10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.11.020Search in Google Scholar

28. Franceschi V, Nakata P. Calcium oxalate in plants: formation and function. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2005;56:41–71.10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144106Search in Google Scholar

29. Roberts JA, Bennett PC, González LA, Macpherson GL, Milliken KL. Microbial precipitation of dolomite in methanogenic groundwater. Geology 2004;32:277–80.10.1130/G20246.2Search in Google Scholar

30. Warren JK. Sedimentology and mineralogy of dolomitic Coorong lakes, South Australia. J Sed Res 1990;60:843–58.10.1306/212F929B-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865DSearch in Google Scholar

31. Hull H, Turnbull A. A thermochemical study of monohydrocalcite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 1973;37:685–94.10.1016/0016-7037(73)90227-5Search in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Essential oil composition, phenolic content, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of cultivated Satureja rechingeri Jamzad at different phenological stages

- Characterization of a mineral coating of the plant Dyerophytum indicum

- Semisynthesis and insecticidal activity of arylmethylamine derivatives of the neolignan honokiol against Mythimna separata Walker

- Dynamics of alkylresorcinols during rye caryopsis germination and early seedling growth

- New nitrogenous compounds from a Red Sea sponge from the Gulf of Aqaba

- Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of novel 5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-phenyl- 1H-benzimidazole derivatives

- Differential cytotoxic activity of the petroleum ether extract and its furanosesquiterpenoid constituents from Commiphora molmol resin

- A novel C25 sterol peroxide from the endophytic fungus Phoma sp. EA-122

- Bioactive compounds isolated from submerged fermentations of the Chilean fungus Stereum rameale

- Combined Autodock and comparative molecular field analysis study on predicting 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of flavonoids isolated from Spatholobus suberectus Dunn

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Essential oil composition, phenolic content, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of cultivated Satureja rechingeri Jamzad at different phenological stages

- Characterization of a mineral coating of the plant Dyerophytum indicum

- Semisynthesis and insecticidal activity of arylmethylamine derivatives of the neolignan honokiol against Mythimna separata Walker

- Dynamics of alkylresorcinols during rye caryopsis germination and early seedling growth

- New nitrogenous compounds from a Red Sea sponge from the Gulf of Aqaba

- Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of novel 5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-phenyl- 1H-benzimidazole derivatives

- Differential cytotoxic activity of the petroleum ether extract and its furanosesquiterpenoid constituents from Commiphora molmol resin

- A novel C25 sterol peroxide from the endophytic fungus Phoma sp. EA-122

- Bioactive compounds isolated from submerged fermentations of the Chilean fungus Stereum rameale

- Combined Autodock and comparative molecular field analysis study on predicting 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of flavonoids isolated from Spatholobus suberectus Dunn