Abstract

The introduction of ionic liquids has emerged as an effective method to enhance the properties of polymer/filler composites, marking significant progress in creating advanced materials for specialized applications. It is crucial to understand and modify the chemical properties of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites to improve their performance in various domains. These properties significantly affect the composites’ appropriateness for specific uses. In this short review, various polymer matrices, fillers, and ionic liquids used in these composites are identified. Additionally, the influence of ionic liquids on the composites’ chemical properties, analyzed using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, is shortly covered. This review spans a decade of research, covering developments from 2013 to 2023 in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites. It contributes to a deeper understanding of FTIR absorption spectra of the composites. In summary, the increase in peak intensities in the FTIR spectra of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites correlates with enhanced general characteristics. Furthermore, wavenumber shifts toward higher values in these composites, relative to neat polymers, indicate improvements in specific properties. These enhancements are attributed to the intermolecular interactions among polymers, fillers, and ionic liquids.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites represent a cutting-edge class of materials that combine the unique properties of polymers, fillers, and ionic liquids, contributing to the development of composites with enhanced functionalities. Polymers provide the backbone for these composites, offering flexibility, rigidity, and durability, while fillers are incorporated to improve mechanical strength, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity. The introduction of ionic liquids can further improve conductivity and processability [1], making these composite materials highly versatile. Ionic liquids, with their exceptional ionic conductivity and thermal stability [2], are introduced to augment these properties, creating composites ideal for a wide range of applications, from high-performance electronics to advanced biomedical devices [3]. The synergy between the polymers, fillers, and ionic liquids in these composites results in materials that exhibit tailored physical and chemical properties. This customization allows for the development of innovative solutions to technical challenges, including the fabrication of lightweight, high-strength materials and conductive yet flexible components for next-generation devices. The design and optimization of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites hinge on understanding the interactions at the molecular level among the constituents, which dictate the composite’s final properties. As such, these materials stand at the forefront of materials science research, offering versatile platforms for the development of advanced technologies.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy plays a crucial role in the characterization of polymer composites, offering deep insights into their molecular structure and the interactions between their constituents [4]. This spectroscopic technique is highly valued for its ability to identify functional groups and assess the extent of chemical bonding or interaction within the composite matrix [5]. By analyzing the infrared absorption spectra, researchers can deduce the presence of specific chemical moieties and infer the compatibility. FTIR spectroscopy is particularly adept at revealing how the incorporation of various fillers or additives alters the chemical environment of the polymer, which in turn affects the material’s physical and mechanical properties [6]. This information is vital for tailoring the composition of polymer composites to achieve desired functionalities. Additionally, FTIR spectroscopy can track changes in the chemical structure of the polymer over time or under different environmental conditions, providing valuable data on the composite’s stability and durability [7]. Through the application of FTIR studies, scientists and engineers can refine the development of polymer composites, ensuring that the final products meet specific requirements for a wide range of industrial, technological, and medicinal applications. This makes FTIR spectroscopy an indispensable tool in the field of materials science, facilitating the advancement of polymer composite technology.

The FTIR spectroscopy study of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites is crucial, as it provides insightful information about the intermolecular interactions and compatibility between their components induced by filler incorporation and ionic liquid introduction [8]. The interplay between the components in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites is of great interest, as it directly influences the overall properties of the material [9], thus highlighting the importance of detailed FTIR studies in advancing the field. This review intends to emphasize the recent advancements in the field of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites, focusing on the comprehension gained from FTIR spectroscopic analyses and their implications for material properties. To date, limited literature has specifically reviewed polymer matrices, fillers, ionic liquids, and their FTIR analysis in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites. This short review intends to fill this gap by focusing on the influence of ionic liquids within polymer composites, particularly regarding their effects on FTIR spectroscopy results. By delving into the role of ionic liquids, this review seeks to offer a brief insight into the intermolecular interactions governing these composites. The exploration aims to enhance the understanding of how ionic liquids affect the composite structure and properties, as seen through FTIR studies, contributing to the broader knowledge base in materials science.

2 Polymer matrices of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

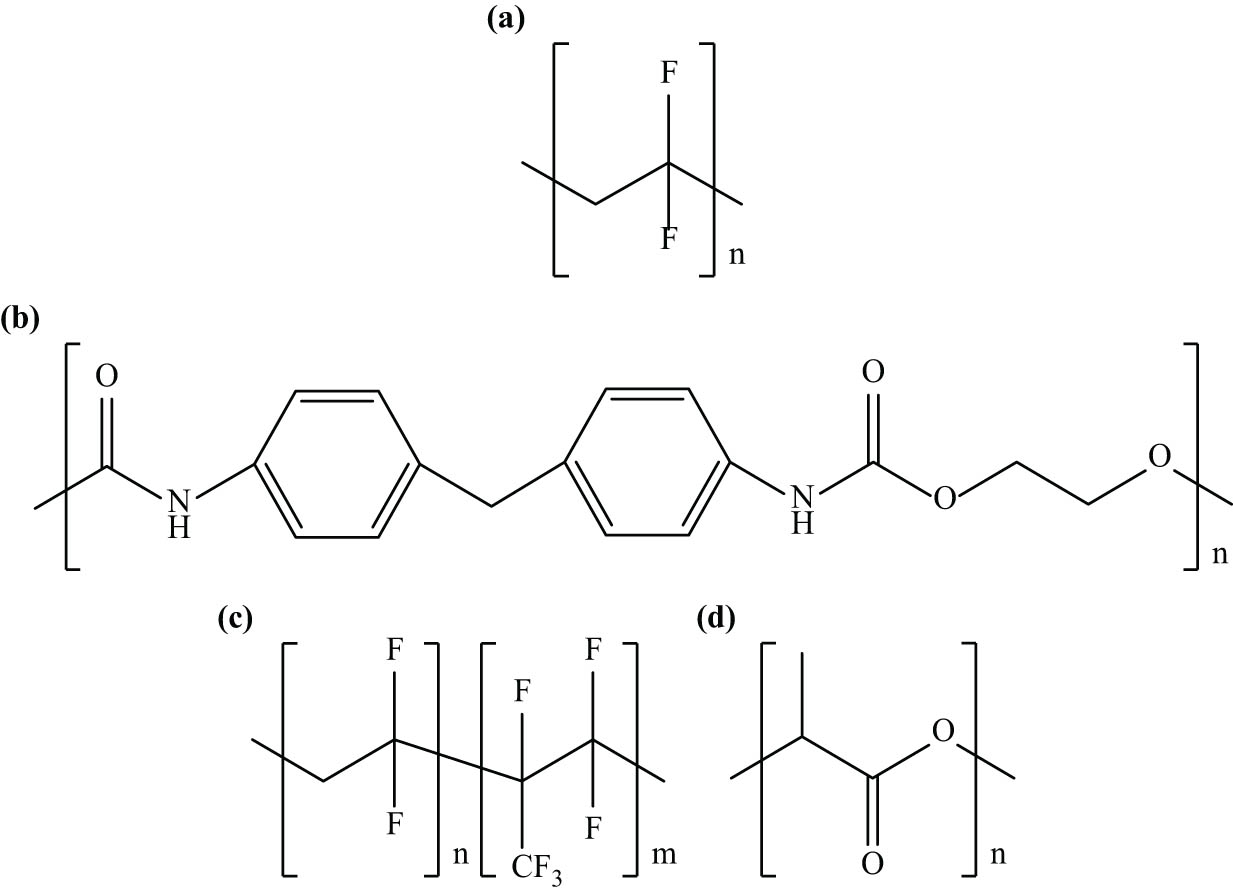

Table 1 shows examples of polymer matrices employed in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites. The polymer matrices listed were specifically chosen because they have been extensively studied in FTIR analyses of composites containing ionic liquids. It can be seen that thermoplastics are often preferred over other types of polymer matrices. This preference is attributed to their ease of processing and superior ability to combine with various fillers and ionic liquids. The versatility of thermoplastics enables the customization of composite properties to meet specific application needs, ranging from biomedical devices to automotive components. In addition, the table reveals that poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) stands out as the most frequently employed polymer matrix, underscoring its significant role in composite development. PVDF’s popularity can be attributed to its excellent piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties [20,31], making it a favored choice for advanced electronic and energy storage applications [21]. Other polymers, such as polyurethane (PU) and poly(vinylidene-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-HFP), are also employed, suggesting their valuable properties and changeability in enhancing composite performance. On the other hand, biodegradable polymers like poly(lactic acid) (PLA) reflect growing research interest in sustainable materials [32], indicating an effort to balance performance with environmental considerations. Figure 1 shows the chemical structures of PVDF, PU, PVDF-HFP, and PLA. The use of both thermosetting diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A and thermoplastic polyurethane indicates the importance of chemical resistance and mechanical flexibility in composite applications. Conductive polymers such as polyaniline are included due to their potential in electronic applications, while natural rubber latex and poly(methyl methacrylate) are noted for their elasticity and optical clarity. This variety of polymer matrices illustrates the wide-ranging potential for designing polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites with tailored properties for particular applications, from biodegradable materials to high-performance electronic components. Table 1 also shows the characteristic peaks of the polymer matrices employed in the polymer composites, which are discussed in Section 5.

Examples of polymer matrices employed in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

| Polymer matrix | Abbreviation | Type | Characteristic peak (cm−1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A | DGEBA | Thermoset | 914, 1,184 | [10] |

| Natural rubber latex | NRL | Elastomer | 1,221, 1,081 | [11] |

| Polyaniline | PANI | Thermoplastic | 1,570, 1,440–1,470 | [12] |

| Poly(lactic acid) | PLA | Thermoplastic | 1,749 | [13,14] |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | PMMA | Thermoplastic | 1,722, 1,147 | [15] |

| Polyurethane | PU | Thermoset | 1,700 | [5,16] |

| Poly(vinylidene fluoride) | PVDF | Thermoplastic | 870–873 | [3,9,17–27] |

| Poly(vinylidene-co-hexafluoropropylene) | PVDF-HFP | Thermoplastic | 1,064 | [28,29] |

| Thermoplastic polyurethane | TPU | Thermoplastic | 3,297 | [30] |

Chemical structures of (a) PVDF, (b) PU, (c) PVDF-HFP, and (d) PLA.

3 Fillers of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

Table 2 shows examples of fillers used in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites. The table categorizes the fillers into organic-, inorganic-, and carbon-based types, each enhancing the specific properties of the composites, such as the mechanical strength, thermal stability, electrical conductivity, and many more, depending on their unique characteristics and interactions with the polymer matrices and ionic liquids. Table 2 also indicates a significant emphasis on carbon-based nanomaterials, particularly multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), which are the most frequently used filler. This preference underscores the exceptional mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, and thermal stability MWCNTs offer [33], making them ideal for reinforcing polymers in high-performance applications. Graphene and its derivatives, including graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide, also feature prominently, highlighting their growing importance in enhancing composite properties such as electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and barrier properties [34]. The two-dimensional structures of these materials offer high aspect ratios, contributing to improved load transfer and dispersion within the polymer matrix [35]. Other notable fillers include sodium montmorillonite and modified montmorillonite, pointing toward an interest in nanoclays for improving mechanical and barrier properties while maintaining the composite’s lightweight nature. The incorporation of wood flour reflects an ongoing exploration into sustainable and biodegradable composite materials, catering to the demand for eco-friendly alternatives [36]. The wide array of fillers demonstrates a strategic approach to composite design, where the choice of filler is closely aligned with the desired composite properties, ranging from electrical and mechanical enhancements to sustainability.

Examples of fillers used in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

| Filler | Abbreviation | Type | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aramid pulp | AP | Organic | [16] |

| Carboxylated multiwalled carbon nanotubes | MWCNT-COOH | Carbon | [9,25] |

| Core-shell rubber particles | CSR | Organic | [10] |

| Graphene | Gra | Carbon | [17] |

| Graphene oxide | GO | Carbon | [3] |

| Mica clay | Mica | Inorganic | [29] |

| Multiwalled carbon nanotubes | MWCNTs | Carbon | [11–13,18,20,24,27,30] |

| Nano-silica | Nano-SiO2 | Inorganic | [5] |

| Octadecylamine-modified montmorillonite | OMMT | Inorganic | [28] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone grains | PVPg | Organic | [26] |

| Reduced graphene oxide | rGO | Carbon | [22] |

| Single-walled carbon nanotubes | SWCNTs | Carbon | [19] |

| Sodium montmorillonite | NaMMT | Inorganic | [21,23] |

| Titania | TiO₂ | Inorganic | [15] |

| Wood flour | WF | Organic | [14] |

4 Ionic liquids of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

Table 3 shows examples of ionic liquids applied in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites. Among ionic liquids, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ([Bmim][PF6]) stands out due to its frequent applications in polymer blends and polymer composites as a compatibilizing agent [37], coupling agent [38], synergistic agent [39], and filler modifier [40], indicating a strong preference for this ionic liquid. Its popularity highlights the importance of ionic liquids in enhancing interactions within the composites [5]. A variety of ionic liquids, including those with imidazolium and phosphonium cations, reflect a strategic exploration to optimize the thermal stability, mechanical strength, and electrical conductivity of the composites. The presence of various anions, such as chloride, bromide, hexafluorophosphate, bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, and tetrafluoroborate, further demonstrates how the selection of ionic liquids can be tailored to specific needs, impacting the polymer composite’s overall performance and functionality. Moreover, the introduction of ionic liquids with different functional groups suggests a targeted approach to enhance interactions at the polymer–filler interface, improving composite compatibility and performance [3]. Figure 2 shows the chemical structures of [Bmim][PF6], [Aemim][Br], and [Thtdp][TFSA]. Table 3 also shows the hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties of ionic liquids, which significantly influence the properties of polymer composites. For example, hydrophilic ionic liquids like [Aemim][Br] and [Bmim][Cl] enhance water absorption in the composites, making them suitable for applications that require moisture sensitivity. Conversely, hydrophobic ionic liquids such as [Bmim][PF6] and [Thtdp][TFSA] improve the water resistance and thermal stability of the composites, extending their use in environments exposed to extreme conditions. The breadth of ionic liquids listed in Table 3 signifies a keen interest in harnessing their unique properties to advance the field of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites, focusing on achieving desired material characteristics through careful selection and combination of these versatile components.

Examples of ionic liquids applied in polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

| Ionic liquid | Abbreviation | Type | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-methylimidazolium bromide | [Aemim][Br] | Hydrophilic | [3,25] |

| 1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate | [Beim][PF6] | Hydrophobic | [17] |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide | [Bmim][Br] | Hydrophilic | [22,28] |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride | [Bmim][Cl] | Hydrophilic | [23] |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate | [Bmim][PF6] | Hydrophobic | [5,9,19,20] |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate | [Bmim][BF4] | Hydrophilic | [12] |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | [Bmim][TFSI] | Hydrophobic | [11] |

| 1-Carboxymethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride | [Cmmim][Cl] | Hydrophilic | [16] |

| 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate | [Emim][BF4] | Hydrophilic | [26] |

| 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate | [Emim][Ts] | Hydrophilic | [29] |

| 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | [Emim][TFSI] | Hydrophobic | [27] |

| 1-Hexadecyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride | [Hdmim][Cl] | Hydrophilic | [21] |

| 1-Hexadecyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate | [Hdmim][PF6] | Hydrophobic | [24] |

| 1-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-3-methylimidazolium chloride | [Hemim][Cl] | Hydrophilic | [13] |

| 1-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate | [Hemim][H2PO4] | Hydrophilic | [13] |

| 1-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-3-methylimidazolium nitrate | [Hemim][NO3] | Hydrophilic | [13] |

| 1-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide | [Hemim][TFSI] | Hydrophobic | [13] |

| Tetrabutylphosphonium chloride | [Tbp][Cl] | Hydrophilic | [15] |

| Tributyl(ethyl)phosphonium diethyl phosphate | [Tbep][Dep] | Hydrophilic | [10] |

| Trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium bistriflamide | [Thtdp][TFSA] | Hydrophobic | [14,18] |

| 1-Vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide | [Veim][Br] | Hydrophilic | [30] |

| 1-Vinyl-3-hexylimidazolium bromide | [Vhim][Br] | Hydrophilic | [30] |

![Figure 2

Chemical structures of (a) [Bmim][PF6], (b) [Aemim][Br], and (c) [Thtdp][TFSA].](/document/doi/10.1515/revac-2025-0084/asset/graphic/j_revac-2025-0084_fig_002.jpg)

Chemical structures of (a) [Bmim][PF6], (b) [Aemim][Br], and (c) [Thtdp][TFSA].

5 FTIR spectroscopy study of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

The FTIR spectroscopy study of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites represents a pivotal exploration into the molecular architecture and interaction dynamics within these advanced materials. FTIR analysis provides a non-destructive [41], precise methodology for examining the chemical bonding and structural modifications induced by the integration of fillers and ionic liquids into polymer matrices [3]. This spectroscopic technique sheds light on the vibrational energy states of molecules, offering insights into the intermolecular interactions and compatibility between the composite components. Such interactions are critical for optimizing the material properties, including mechanical strength, thermal stability, physical characteristics, chemical resistance, and electrical conductivity. By the identification of characteristic absorption peaks [15,26] and investigation of peak intensity or wavenumber shifts [42], FTIR spectroscopy reveals how the introduction of ionic liquids influences the polymer’s chemical environment, potentially creating intermolecular interactions [43], enhancing the dispersion of fillers [10], and improving the composite’s overall performance. The study of these composites via FTIR spectroscopy thus provides a comprehensive understanding of the material’s molecular structure, enabling the tailored development of composites with specific functionalities for diverse technological and medical applications. This analytical approach underscores the importance of molecular-level insights in advancing the field of materials science, highlighting the role of FTIR spectroscopy in the development of innovative composite materials.

5.1 Peak intensity in FTIR spectra of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

Table 4 shows the investigation of peak intensity in FTIR spectra for polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites. Zhang et al. studied the characteristic peak intensities of the PVDF/Gra/[Beim][PF6] composites [17]. They found that the peak intensity of the polar β phase at 840 cm−1 in the composites is stronger than that in pure PVDF. This enhancement is due to the interaction between the −CF2 groups in PVDF and the imidazolium cation of [Beim][PF6], which increases the content of the β phase [17]. In addition, the introduction of ionic liquid enhances the dispersion of Gra in the PVDF matrix [17,44]. These enhancements imply improved dielectric and electrical properties in the composites.

Investigation of peak intensity in FTIR spectra for polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

| Polymer | Filler | Ionic liquid | Characteristic peak (cm−1) | Peak intensity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVDF | Gra | [Beim][PF6] | 840 | Strong | [17] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs | [Bmim][PF6] | 1,275 | Strong | [20] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs | [Thtdp][TFSA] | 840, 1275, 1232 | Strong | [18] |

| PVDF | NaMMT | [Hdmim][Cl] | 839, 1,231, 1,274 | Strong | [21] |

| PVDF | SWCNTs | [Bmim][PF6] | 1,274, 840, 1,230, 834 | Strong | [19] |

| PU | AP | [Cmmim][Cl] | 1,708, 1,219 | Strong | [16] |

Xing et al. studied the characteristic peak intensities of the PVDF/MWCNTs/[Bmim][PF6] composites [20]. They observed that the peak intensity at 1,275 cm−1 in the composites increased as the ratio of [Bmim][PF6] to MWCNTs increased. This increase is due to [Bmim][PF6] facilitating the formation of the β-crystal form [20]. The increase in peak intensity, indicative of enhanced β-crystal formation, suggests improved piezoelectric and pyroelectric properties.

dos Santos et al. studied the characteristic peak intensities of the PVDF/MWCNTs/[Thtdp][TFSA] composites [18]. They observed that the peaks at 840, 1,275, and 1,232 cm−1 in the composites increased in intensity. This increase is attributed to [Thtdp][TFSA] inducing the formation of the polar β- and γ-phase forms [18]. The observed increase in peak intensities, indicating the formation of polar β- and γ-phases, suggests enhanced microwave absorbing properties in the composites.

Song et al. studied the characteristic peak intensities of the PVDF/NaMMT/[Hdmim][Cl] composites [21]. They discovered that the peak intensities of the α-phase at 765, 796, 976, and 1,387 cm−1 in the composites disappeared, while the polar crystal absorption peaks at 839, 1,231, and 1,274 cm−1 strongly emerged. This transition is caused by the synergy between [Hdmim][Cl] and NaMMT, which induced the formation of 100% polar crystal structures in the composites [21]. The emergence of 100% polar crystal structures implies significantly enhanced electroactive, transparency, and dielectric properties.

Yang et al. studied the characteristic peak intensities of the PVDF/SWCNTs/[Bmim][PF6] composites [19]. They noticed that the peak intensities of the polar β-form at 1,274 and 840 cm−1 and the γ-form at 1,230 and 834 cm−1 in the composites became very strong. This change is induced by the coating layer of [Bmim][PF6] on the surface, which amplifies the role of SWCNTs in promoting the formation of polar PVDF crystals [19]. The significant enhancement in the peak intensities of the polar β- and γ-forms suggests a substantial improvement in the piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties of the composites.

Kerche et al. studied the characteristic peak intensities of the PU/AP/[Cmmim][Cl] composites [16]. They perceived that the peaks at 1,708 and 1,219 cm−1, corresponding to the C═O bond in carbonyl from urethane groups and C–N stretching from urea, respectively, in the composites, showed stronger intensity. This enhancement is ascribed to increased crosslink formation between PU and AP-[Cmmim][Cl] [16]. The observed increase in peak intensities, indicating enhanced crosslink formation, suggests improved mechanical properties and thermal stability in the composites.

5.2 Wavenumber shifts in the FTIR spectra of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

Table 5 shows the investigation of wavenumber shifts in the FTIR spectra of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites. Quitadamo et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PLA/WF/[Thtdp][TFSA] composites [14]. They observed that the peak wavenumber for C═O stretching in the composites shifted to a higher value (1,752 cm−1) compared to neat PLA (1,749 cm−1). This shift is attributed to the interactions between PLA and [Thtdp][TFSA] in the PLA/WF/[Thtdp][TFSA] composites [14]. The observed shift to a higher wavenumber suggests enhanced molecular interactions, potentially leading to improved thermal stability and elastic modulus of the composites.

Investigation of wavenumber shifts in the FTIR spectra of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

| Polymer | Filler | Ionic liquid | Characteristic peak (cm−1) | Wavenumber shift | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | WF | [Thtdp][TFSA] | 1,752 | High | [14] |

| PU | Nano-SiO2 | [Bmim][PF6] | 1,710 | High | [5] |

| PVDF | GO | [Aemim][Br] | 883 | High | [3] |

| PVDF | NaMMT | [Bmim][Cl] | 878 | High | [23] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs | [Emim][TFSI] | 875 | High | [27] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs | [Hdmim][PF6] | 1,072 | High | [24] |

| PVDF | MWCNT-COOH | [Aemim][Br] | 884 | High | [25] |

| PVDF | MWCNT-COOH | [Bmim][PF6] | 802, 875 | High | [9] |

| PVDF | rGO | [Bmim][Br] | 1,394 | High | [22] |

| PVDF-HFP | Mica | [Emim][Ts] | 1,073 | High | [29] |

| TPU | MWCNTs | [Vhim][Br] | 3,330 | High | [30] |

Członka et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PU/nano-SiO2/[Bmim][PF6] composites [5]. They discovered that the peak wavenumber for the carbonyl stretching vibration in the composites shifted to a higher value, from 1,700 to 1,710 cm−1. This shift is caused by the incorporation of SiO2-[Bmim][PF6], which disturbs the hydrogen bonding between NH and C═O in the PU matrix [5]. The shift to a higher wavenumber suggests improved interaction within the composites, enhancing their mechanical strength and lowering the thermal conductivity.

Maity et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PVDF/GO/[Aemim][Br] composites [3]. They noticed that the peak wavenumber for the bending vibration of the ‒CF‒CH‒CF‒ group in the composites, originally at 873 cm−1 shifted to a higher value of 883 cm−1 in neat PVDF. This shift is induced by the incorporation of GO-[Aemim][Br], which enhances the supramolecular interactions between the imidazolium cation of [Aemim][Br] and the >CF2 dipole in the PVDF matrix [3]. The observed shift, indicating enhanced supramolecular interactions, suggests improved electrical conductivity and dielectric permittivity in the composites.

Thomas et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PVDF/NaMMT/[Bmim][Cl] composites [23]. They perceived that the peak wavenumber for the CF2–CH2 bending vibration, originally at 871 cm−1 in pristine PVDF, shifted to 878 cm−1 in the composites. This shift is ascribed to β-phase formation, driven by the Coulombic interactions between the imidazolium cations at the modified MMT interface and the negatively polarized CF2 groups in PVDF [23]. The shift toward higher a wavenumber and subsequent β-phase formation indicate enhanced electrical and mechanical properties of the composites.

Sharma et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PVDF/MWCNTs/[Emim][TFSI] composites [27]. They found that the peak wavenumber at 872 cm−1, corresponding to the CH–CF–CH stretching in neat PVDF, shifted to a higher value of 875 cm−1 in the composites. This shift is likely due to the electrostatic interactions between the anion of [Emim][TFSI] and the PVDF, which facilitated the transformation from the α-phase to the γ phase in PVDF [27]. The shift and resulting γ-phase formation enhance the electrical conductivity and structural properties of the composites.

Bahader et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PVDF/MWCNTs/[Hdmim][PF6] composites [24]. They observed that the peak wavenumber for the >CF2 stretching vibration in the PVDF/MWCNTs composite at 1,065 cm−1 shifted to 1,072 cm−1 in the composites. This shift is attributed to [Hdmim][PF6], which acted as a linker and improved the compatibility between MWCNTs and PVDF [24]. The shift in a peak wavenumber indicates improved molecular alignment and interaction, leading to enhanced crystallization behavior and mechanical toughness of the composites.

Mandal and Nandi studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PVDF/MWCNT-COOH/[Aemim][Br] composites [25]. They discovered that the CF–CH–CF bending vibration peak wavenumber of PVDF at 876 cm−1 shifted to a higher wavenumber (884 cm−1) in the composites. This shift is caused by the incorporation of MWCNT-COOH-[Aemim][Br], which increased the dipole–dipole interactions between the imidazolium cations on the surface of MWCNT-COOH and the >CF2 dipoles along the molecular chain of PVDF [25]. The shift to a higher wavenumber and enhanced dipole–dipole interactions suggest improved mechanical properties and electrical conductivity for composites.

Ke et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PVDF/MWCNT-COOH/[Bmim][PF6] composites [9]. They noticed that the peak wavenumbers for the –CF2 stretching vibrations in pure PVDF and the PVDF/MWCNT-COOH composite appear at 796 and 870 cm−1, respectively. In contrast, in the composites containing [Bmim][PF6], these peaks shifted to higher wavenumbers of 802 and 875 cm−1, respectively. These shifts are induced by the interactions between the –CF2 groups and the imidazolium rings on the [Bmim][PF6]-connected MWCNT-COOH [9]. The observed shifts to higher wavenumbers indicate stronger intermolecular forces and improved structural alignment, enhancing the composite’s piezoresistive sensitivity and mechanical toughness.

Razzaq et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PVDF/rGO/[Bmim][Br] composites [22]. They perceived that the C–F peak wavenumber in the composites shifted from 1,167 cm−1 to 1,394 cm−1. This shift is ascribed to the incorporation of rGO-[Bmim][Br], which enhanced the stabilization of the polar β and γ phases [22]. The significant wavenumber shift and enhanced stabilization of the β and γ phases improve the composites’ permeation properties.

Pandey et al. studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the PVDF-HFP/mica/[Emim][Ts] composites [29]. They found that the peak wavenumber at 1,064 cm−1, which corresponds to the symmetrical stretching mode of –CF2, shifted to a higher value of 1,073 cm−1. This shift is due to the incorporation of Mica-[Emim][Ts] into the PVDF-HFP matrix, confirming the dissociation of [Emim][Ts] and their complexation with the PVDF-HFP network [29]. The shift to a higher wavenumber indicates enhanced polymer-filler interactions, leading to improved filtration performance, heat shrinkage, and mechanical resistance in the composites.

Xu and Zhang studied the characteristic peak wavenumbers of the TPU/MWCNTs/[Vhim][Br] composites [30]. They observed that the peak wavenumber for the stretching vibration of the hydrogen-bonded N–H groups in the composites shifted to a higher value (3,330 cm−1), compared to pure TPU (3,297 cm−1). This shift is attributed to the MWCNTs-[Vhim][Br] disrupting the N–H/C═O hydrogen bonding within the TPU matrix [30]. The wavenumber shift indicates enhanced mobility of the TPU molecular chains, which improves their dipolar polarizability under an electric field, thereby increasing the dielectric constant of the composites.

6 Discussion

In an examination of FTIR spectra analyses across various polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites, significant findings have been observed concerning peak intensity changes and their implications on composite properties. For example, in PVDF/Gra/[Beim][PF6] composites, a notable increase in the peak intensity of the polar β phase compared to pure PVDF suggests an enhanced β-phase content due to the interaction between the –CF2 groups of PVDF and the imidazolium cation of [Beim][PF6]. This interaction not only increases the β phase but also improves the dispersion of Gra in the PVDF matrix, suggesting a consequent enhancement in dielectric and electrical properties. Similarly, in PVDF/MWCNTs/[Bmim][PF6] composites, an increase in peak intensity correlates with an increased ratio of [Bmim][PF6] to MWCNTs. This trend is indicative of the ionic liquid’s role in promoting the β-crystal form, leading to enhanced piezoelectric and pyroelectric properties. Likewise, the use of [Thtdp][TFSA] in PVDF/MWCNT composites has been shown to induce the formation of polar β- and γ-phase forms, as evidenced by increased peak intensities, enhancing the microwave absorbing capabilities of the composites.

The impact of ionic liquids in facilitating structural transformations is further illustrated in PVDF/NaMMT/[Hdmim][Cl] composites, where the α-phase peaks disappear and polar crystal absorption peaks strongly emerge. The synergy between [Hdmim][Cl] and NaMMT triggers the formation of 100% polar crystal structures, significantly boosting the electroactive, transparency, and dielectric properties of the composites. Moreover, PVDF/SWCNTs/[Bmim][PF6] composites exhibit remarkably stronger peak intensities of polar β and γ forms. The [Bmim][PF6] layer enhances the role of SWCNTs in promoting the formation of polar PVDF crystals, substantially improving the piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties of the composites. Finally, PU/AP/[Cmmim][Cl] composites demonstrate stronger peak intensities related to the C═O bond in carbonyl from urethane groups and C–N stretching from urea, respectively. This observed enhancement, attributed to increased crosslink formation between PU and AP-[Cmmim][Cl], points to improved mechanical properties and thermal stability. Collectively, these studies emphasize the essential role of ionic liquids in tuning the structural and functional properties of the polymer composites by FTIR spectra analysis. The presence of ionic liquids not only enhances specific crystalline forms and phases but also extends the application potential of these materials across multiple high-performance domains.

The exploration of wavenumber shifts in the FTIR spectra across various polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites demonstrates a crucial connection between these shifts and the enhanced properties of the composites. These wavenumber shifts typically suggest stronger intermolecular interactions and structural alignment within the composites, leading to improved mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties. For instance, in PLA/WF/[Thtdp][TFSA] composites, the observed shift in the peak wavenumber for C═O stretching to a higher value indicates enhanced interactions between PLA and [Thtdp][TFSA], suggesting improvements in thermal stability and elastic modulus. Similarly, in PU/nano-SiO2/[Bmim][PF6] composites, the shift in the carbonyl stretching vibration is caused by the incorporation of SiO2-[Bmim][PF6], which disrupts the existing hydrogen bonding of the PU matrix, thereby enhancing mechanical strength and reducing thermal conductivity. Further analysis of the PVDF/GO/[Aemim][Br] composites shows that the incorporation of GO-[Aemim][Br] shifts to a higher wavenumber, improving supramolecular interactions and leading to increased electrical conductivity and dielectric permittivity. The PVDF/NaMMT/[Bmim][Cl] and PVDF/MWCNTs/[Emim][TFSI] composites also show similar trends where the shift toward higher wavenumbers corresponds with enhanced electrical conductivity and mechanical properties, attributed to improvements in molecular interactions facilitated by ionic liquids. This indicates that the ionic liquids not only aid in increasing electrical properties but also enhance the structural reinforcement of the composites.

Moreover, in composites like PVDF/MWCNTs/[Hdmim][PF6], the shift in the peak wavenumber suggests stronger interactions and molecular alignment, significantly improving mechanical toughness and crystallization behavior. The incorporation of MWCNT-COOH-[Aemim][Br] into the PVDF matrix shifts to a higher wavenumber, leading to an increase in dipole–dipole interactions, enhancing both mechanical properties and electrical conductivity. In the PVDF/MWCNT-COOH/[Bmim][PF6] composites, shifts to higher wavenumbers due to interactions between the –CF2 groups and imidazolium rings enhance piezoresistive sensitivity and mechanical toughness. Similarly, in PVDF/rGO/[Bmim][Br] composites, significant wavenumber shifts result in improved stabilization of the polar β and γ phases, enhancing the permeation properties of the composites. Finally, the shift toward higher wavenumbers observed in PVDF-HFP/mica/[Emim][Ts] and TPU/MWCNTs/[Vhim][Br] composites indicates enhanced polymer–filler interactions and molecular chains mobility, leading to improved properties such as filtration performance, heat and mechanical resistance, and dielectric constant. These observations collectively suggest that FTIR spectroscopy is an indispensable tool for understanding the intermolecular interactions within polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites and guiding the creation of novel materials. This understanding enables the strategic design of composites with desired functionalities, opening up new possibilities in materials science and applications.

7 Conclusions

In this review, examples of polymer matrices, fillers, and ionic liquids used in polymer composites are shortly ascertained. The chemical properties of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy are also covered in this short review. PVDF is the most frequently employed polymer matrix in developing these composites, which can be ascribed to its excellent piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties. MWCNTs are the most commonly used fillers due to their exceptional mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, and thermal stability. [Bmim][PF6] is the most applied ionic liquid because it enhances interactions within the composites. Numerous studies show that strong peak intensity in the FTIR spectra of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites indicates improved physical properties. Additionally, shifts to higher wavenumbers in these composites, compared to neat polymers, suggest enhancements in their properties. These improvements are attributed to the intermolecular interactions among the polymer matrices, fillers, and ionic liquids, regardless of the specific types used, as long as interactions exist between them. As advanced polymer composites develop, FTIR spectroscopy is expected to play an important role in further elucidating the complex interactions within these materials. Future research may focus on integrating computational methods with FTIR spectroscopy to analyze absorption spectra, enabling more precise predictions of composite performance. This advancement will facilitate the development of next-generation composites with customized properties for specialized applications.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the editors and reviewers for their valuable and supportive comments during the review process.

-

Funding information: This short review was supported by the Universiti Putra Malaysia under the Grant Putra IPM Scheme (project number: GP-IPM/2024/9789200).

-

Author contributions: Ahmad Adlie Shamsuri: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, and writing – original draft; Mohd Zuhri Mohamed Yusoff: resources, supervision, and validation; Siti Nurul Ain Md. Jamil: data curation and writing – review and editing; and Khalina Abdan: formal analysis and methodology.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

[1] Chen G, Chen N, Li L, Wang Q, Duan W. Ionic liquid modified poly(vinyl alcohol) with improved thermal processability and excellent electrical conductivity. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2018;57:5472–81.10.1021/acs.iecr.8b00157Search in Google Scholar

[2] Shamsuri AA, Md. Jamil SNA, Yusoff MZM, Abdan K. Methods and mechanical properties of polymer hybrid composites and hybrid polymer composites: Influence of ionic liquid addition. Appl Mech. 2024;5:1–19.10.3390/applmech5010001Search in Google Scholar

[3] Maity N, Mandal A, Nandi AK. Interface engineering of ionic liquid integrated graphene in poly(vinylidene fluoride) matrix yielding magnificent improvement in mechanical, electrical and dielectric properties. Polymer (Guildf). 2015;65:154–67.10.1016/j.polymer.2015.03.066Search in Google Scholar

[4] Shamsuri AA, Abdan K, Md. Jamil SNA. Utilization of ionic liquids as compatibilizing agents for polymer blends – preparations and properties. Polym Technol Mater. 2023;62:1008–18.10.1080/25740881.2023.2180390Search in Google Scholar

[5] Członka S, Strąkowska A, Strzelec K, Kairytė A, Vaitkus S. Composites of rigid polyurethane foams and silica powder filler enhanced with ionic liquid. Polym Test. 2019;75:12–25.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2019.01.021Search in Google Scholar

[6] Shamsuri AA, Abdan K, Md. Jamil SNA. Preparations and properties of ionic liquid-assisted electrospun biodegradable polymer fibers. Polymers (Basel). 2022;14:2308.10.3390/polym14122308Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Marzec A, Laskowska A, Boiteux G, Zaborski M, Gain O, Serghei A. Study on weather aging of nitrile rubber composites containing imidazolium ionic liquids. Macromol Symp. 2014;342:25–34.10.1002/masy.201300231Search in Google Scholar

[8] Shamsuri AA, Md. Jamil SNA, Abdan K. Coupling effect of ionic liquids on the mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties of polymer composites: A succinct review. Vietnam J Chem. 2024;62:227–39.10.1002/vjch.202300134Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ke K, Po P, Gao S, Voit B. An ionic liquid as interface linker for tuning piezoresistive sensitivity and toughness in poly(vinylidene fluoride)/carbon nanotube composites. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:5437–46.10.1021/acsami.6b13454Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Nguyen TKL, Soares BG, Duchet-Rumeau J, Livi S. Dual functions of ILs in the core-shell particle reinforced epoxy networks: Curing agent vs dispersion aids. Compos Sci Technol. 2017;140:30–8.10.1016/j.compscitech.2016.12.021Search in Google Scholar

[11] Krainoi A, Kummerloewe C, Nakaramontri Y, Wisunthorn S, Vennemann N, Pichaiyut S, et al. Influence of carbon nanotube and ionic liquid on properties of natural rubber nanocomposites. Express Polym Lett. 2019;13:327–48.10.3144/expresspolymlett.2019.28Search in Google Scholar

[12] Souto LFC, Soares BG. Polyaniline/carbon nanotube hybrids modified with ionic liquids as anticorrosive additive in epoxy coatings. Prog Org Coat. 2020;143:105598.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2020.105598Search in Google Scholar

[13] Fang D, Wen J, Yu H, Zhang J, You X, Liu N. Ionic liquid functionalized polylactides: the effect of anions on catalytic activity and carbon nanotube dispersion. Mater Adv. 2022;4:948–53.10.1039/D2MA01008ASearch in Google Scholar

[14] Quitadamo A, Massardier V, Valente M. Interactions between PLA, PE and wood flour: Effects of compatibilizing agents and ionic liquids. Holzforschung. 2018;72:691–700.10.1515/hf-2017-0149Search in Google Scholar

[15] Hara S, Ishizu M, Watanabe S, Kaneko T, Toyama T, Shimizu S, et al. Improvement of the transparency, mechanical, and shape memory properties of polymethylmethacrylate/titania hybrid films using tetrabutylphosphonium chloride. Polym Chem. 2019;10:4779–88.10.1039/C9PY00783KSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Kerche EF, da Silva VD, da Silveira Jankee G, Schrekker HS, de Avila Delucis R, Irulappasamy S, et al. Aramid pulp treated with imidazolium ionic liquids as a filler in rigid polyurethane bio-foams. J Appl Polym Sci. 2021;138:1–9.10.1002/app.50492Search in Google Scholar

[17] Zhang H, Chen Y, Xiao J, Song F, Wang C, Wang H. Fabrication of enhanced dielectric PVDF nanocomposite based on the conjugated synergistic effect of ionic liquid and graphene. Mater Today Proc. 2019;16:1512–7.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.05.333Search in Google Scholar

[18] dos Santos SCSM, Soares BG, Lopes Pereira EC, Indrusiak T, Silva AA. Impact of phosphonium-based ionic liquids-modified carbon nanotube on the microwave absorbing properties and crystallization behavior of poly(vinylidene fluoride) composites. Mater Chem Phys. 2022;280:125853.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2022.125853Search in Google Scholar

[19] Yang JH, Xiao YJ, Yang CJ, Li ST, Qi XD, Wang Y. Multifunctional poly(vinylidene fluoride) nanocomposites via incorporation of ionic liquid coated carbon nanotubes. Eur Polym J. 2018;98:375–83.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2017.11.037Search in Google Scholar

[20] Xing C, Zhao L, You J, Dong W, Cao X, Li Y. Impact of ionic liquid-modified multiwalled carbon nanotubes on the crystallization behavior of poly(vinylidene fluoride). J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:8312–20.10.1021/jp304166tSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Song S, Xia S, Liu Y, Lv X, Sun S. Effect of Na+ MMT-ionic liquid synergy on electroactive, mechanical, dielectric and energy storage properties of transparent PVDF-based nanocomposites. Chem Eng J. 2020;384:123365.10.1016/j.cej.2019.123365Search in Google Scholar

[22] Razzaq H, Siddique A, Farooq S, Razzaque S, Ahmad B, Tahir S, et al. Hybrid ionogel membrane of PVDF incorporating ionic liquid-reduced graphene oxide for the removal of heavy metal ions from synthetic water. Mater Sci Eng B. 2023;296:116680.10.1016/j.mseb.2023.116680Search in Google Scholar

[23] Thomas E, Parvathy C, Balachandran N, Bhuvaneswari S, Vijayalakshmi KP, George BK. PVDF-ionic liquid modified clay nanocomposites: Phase changes and shish-kebab structure. Polymer (Guildf). 2017;115:70–6.10.1016/j.polymer.2017.03.026Search in Google Scholar

[24] Bahader A, Haoguan G, Haogoa F, Ping W, Shaojun W. Preparation and characterization of poly(vinylidene fluoride) nanocomposites containing amphiphilic ionic liquid modified multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J Polym Res. 2016;23:184.10.1007/s10965-016-1078-2Search in Google Scholar

[25] Mandal A, Nandi AK. Ionic liquid integrated multiwalled carbon nanotube in a poly(vinylidene fluoride) matrix: Formation of a piezoelectric β-polymorph with significant reinforcement and conductivity improvement. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:747–60.10.1021/am302275bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Guo D, Han Y, Huang J, Meng E, Ma L, Zhang H, et al. Hydrophilic poly(vinylidene fluoride) film with enhanced inner channels for both water- and ionic liquid-driven ion-exchange polymer metal composite actuators. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:2386–97.10.1021/acsami.8b18098Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Sharma M, Sharma S, Abraham J, Thomas S, Madras G, Bose S. Flexible EMI shielding materials derived by melt blending PVDF and ionic liquid modified MWNTs. Mater Res Express. 2014;1:035003.10.1088/2053-1591/1/3/035003Search in Google Scholar

[28] Nath AK, Kumar A. Ionic transport properties of PVdF-HFP-MMT intercalated nanocomposite electrolytes based on ionic liquid, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide. Ionics (Kiel). 2013;19:1393–403.10.1007/s11581-013-0878-1Search in Google Scholar

[29] Pandey K, Dwivedi MM, Sanjay SS, Asthana N. Development of mica-based porous polymeric membrane and their application. Ionics (Kiel). 2017;23:113–20.10.1007/s11581-016-1808-9Search in Google Scholar

[30] Xu Q, Zhang W. Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes. E-Polymers. 2021;21:166–78.10.1515/epoly-2021-0018Search in Google Scholar

[31] Shamsuri AA, Yusoff MZM, Abdan K, Jamil SNAM. Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids. E-Polymers. 2023;23:20230060.10.1515/epoly-2023-0060Search in Google Scholar

[32] Shamsuri AA, Jamil SNAM, Abdan K. The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review. E-Polymers. 2022;22:809–20.10.1515/epoly-2022-0074Search in Google Scholar

[33] Subramaniam K, Das A, Heinrich G. Improved oxidation resistance of conducting polychloroprene composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2013;74:14–9.10.1016/j.compscitech.2012.10.002Search in Google Scholar

[34] Shamsuri AA, Yusoff MZM, Abdan K, Md. Jamil SNA. Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2024;63:20240070.10.1515/rams-2024-0070Search in Google Scholar

[35] Liu X, Hong X, Liang B, Long J. Preparation of mechanically stripped functionalized multilayer graphene and its effect on thermal conductivity of polyethylene composites. J Polym Res. 2022;29:1–13.10.1007/s10965-022-02997-5Search in Google Scholar

[36] Shamsuri AA, Abdan K, Md. Jamil SNA. Polybutylene succinate (PBS)/natural fiber green composites: melt blending processes and tensile properties. Phys Sci Rev. 2023;8:5121–33.10.1515/psr-2022-0072Search in Google Scholar

[37] Gouvêa RF, Andrade CT. Testing the effect of imidazolium ionic liquid and citrate derivative on the properties of graphene-based PHBV/EVA immiscible blend. Polym Test. 2020;89:106615.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106615Search in Google Scholar

[38] Wan M, Shen J, Sun C, Gao M, Yue L, Wang Y. Ionic liquid modified graphene oxide for enhanced flame retardancy and mechanical properties of epoxy resin. J Appl Polym Sci. 2021;138:50757.10.1002/app.50757Search in Google Scholar

[39] Gao M, Wang T, Chen X, Zhang X, Yi D, Qian L, et al. Preparation of ionic liquid multifunctional graphene oxide and its effect on decrease fire hazards of flexible polyurethane foam. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2022;147:7289–97.10.1007/s10973-021-11049-xSearch in Google Scholar

[40] Shamsuri AA, Jamil SNAM, Abdan K. Processes and properties of ionic liquid-modified nanofiller/polymer nanocomposites—A succinct review. Processes. 2021;9:480.10.3390/pr9030480Search in Google Scholar

[41] Rolere S, Liengprayoon S, Vaysse L, Sainte-Beuve J, Bonfils F. Investigating natural rubber composition with Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy: A rapid and non-destructive method to determine both protein and lipid contents simultaneously. Polym Test. 2015;43:83–93.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2015.02.011Search in Google Scholar

[42] Abraham J, Sidhardhan Sisanth K, Zachariah AK, Mariya HJ, George SC, Kalarikkal N, et al. Transport and solvent sensing characteristics of styrene butadiene rubber nanocomposites containing imidazolium ionic liquid modified carbon nanotubes. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137:1–10.10.1002/app.49429Search in Google Scholar

[43] Li Y-C, Lee S-Y, Wang H, Jin F-L, Park S-J. Enhanced electrical properties and impact strength of phenolic formaldehyde resin using silanized graphene and ionic liquid. ACS Omega. 2024;9:294–303.10.1021/acsomega.3c05198Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Shamsuri AA, Md. Jamil SNA, Yusoff MZM, Abdan K. Polymer composites containing ionic liquids: A study of electrical conductivity. Electron Mater. 2024;5:189–203.10.3390/electronicmat5040013Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Impressive stability-indicating RP-HPLC method for concurrent quantification of salbutamol, guaifenesin, and sodium benzoate in cough syrup: Application of six sigma and green metrics

- Bioanalytically validated potentiometric method for determination of bisphenol A: Application to baby bibs, pacifiers, and Teethers’ saliva samples

- Environmental impact of RP-HPLC strategy for detection of selected antibiotics residues in wastewater: Evaluating of quality tools

- Trace-level impurity quantification in lead-cooled fast reactors using ICP-MS: Methodology and challenges

- Picogram-level detection of three ACE inhibitors via LC–MS/MS: Comparing BMP and UOSA54 derivatization methods

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC method for concurrent estimation of a promising combination of methocarbamol and etoricoxib in rat plasma

- Development of a point-of-care testing sensor using polypyrrole/TiO2 molecular imprinting technology for cinchocaine determination

- Green and sustainable RP-UPLC and UV strategies for determination of metformin and dapagliflozin: Evaluation of environmental impact and whiteness

- Review Articles

- Determination of montelukast and non-sedating antihistamine combination in pharmaceutical dosage forms: A review

- Extraction approaches for the isolation of some POPs from lipid-based environmental and food matrices: A review

- A review of semiconductor photocatalyst characterization techniques

- Analytical determination techniques for lithium – A review

- Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy study of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Impressive stability-indicating RP-HPLC method for concurrent quantification of salbutamol, guaifenesin, and sodium benzoate in cough syrup: Application of six sigma and green metrics

- Bioanalytically validated potentiometric method for determination of bisphenol A: Application to baby bibs, pacifiers, and Teethers’ saliva samples

- Environmental impact of RP-HPLC strategy for detection of selected antibiotics residues in wastewater: Evaluating of quality tools

- Trace-level impurity quantification in lead-cooled fast reactors using ICP-MS: Methodology and challenges

- Picogram-level detection of three ACE inhibitors via LC–MS/MS: Comparing BMP and UOSA54 derivatization methods

- Eco-friendly RP-HPLC method for concurrent estimation of a promising combination of methocarbamol and etoricoxib in rat plasma

- Development of a point-of-care testing sensor using polypyrrole/TiO2 molecular imprinting technology for cinchocaine determination

- Green and sustainable RP-UPLC and UV strategies for determination of metformin and dapagliflozin: Evaluation of environmental impact and whiteness

- Review Articles

- Determination of montelukast and non-sedating antihistamine combination in pharmaceutical dosage forms: A review

- Extraction approaches for the isolation of some POPs from lipid-based environmental and food matrices: A review

- A review of semiconductor photocatalyst characterization techniques

- Analytical determination techniques for lithium – A review

- Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy study of polymer/filler/ionic liquid composites