Abstract

The aim of this article will be to examine the operations of the Yugoslav Partisans and German armed forces in northern parts of Yugoslavia in late 1944 and early 1945. Since the summer of 1941, the communist-led guerrilla movement had conducted a massive guerrilla campaign against Axis forces, at the same time striving to build a regular army and thus gain recognition as a full-time member of the anti-Hitler coalition. The arrival of the Red Army and liberation of country’s eastern parts in September and October 1944 secured material foundations for a creation of a regular field force. Whether this nascent army would be capable of defeating its retreating, but still dangerous German foe remained to be seen.

Zusammenfassung

Der vorliegende Artikel analysiert die Operationen, die von Ende Oktober 1944 bis Mitte April 1945 in nördlichen Teilen des ehemaligen Jugoslawiens im Rahmen der »Syrmien-Front« stattgefunden haben. Seit dem Sommer 1941 führte die kommunistisch-dominierte Jugoslawische Volksbefreiungsbewegung einen massiven Guerilla-Krieg gegen die deutsche Wehrmacht. Parallel dazu strebte die Partisanen-Führung an, eine reguläre Armee zu bilden, um dadurch die politische Legitimation und den Status eines Vollmitglieds der Anti-Hitler Koalition zu gewinnen. Erst mit der Ankunft der Roten Armee im Frühherbst 1944 und darauffolgender Befreiung weiter Teile des Landes waren die materiellen Voraussetzungen für die beabsichtigte Transformation geschaffen. Die Frage blieb offen, ob die nun zahlenmäßig starke und großteils mit modernen sowjetischen Waffen ausgerüstete, aber unerfahrene jugoslawische Armee ihren angeschlagenen, aber noch gefährlichen Gegner in offener Schlacht besiegen konnte

The fierce fighting in the flat, open terrain of the province of Syrmia[1] counted among the bloodiest of the whole war and left a lasting controversy about whether the Yugoslav Partisans should have pursued an active campaign on the so-called »Syrmian Front« in the first place. In the socialist Yugoslavia prior to the late 1970s, descriptions of operations on the Syrmian Front could usually be found in either general war histories or in unit histories; relevant Partisan documents were published in several volumes of the massive »Zbornik dokumenata i podataka NOR-a« edition. The first (and the most important) dedicated monograph on the campaign, however, was published only in 1979. Generally speaking, Yugoslav works are a reliable source in terms of the purely operational aspects of the campaign (e.g. timeline, involved units, and troop movements). Their main flaws lie in inflated claims of enemy losses and a lack of a comprehensive, in-depth, and ideology-free analysis of one’s own failures. The fall of Socialism in the early 1990s did little to rectify these shortcomings. On the contrary, the »new age« was marked by a drop of academic interest in the military aspects of the Second World War in former Yugoslavia. Worse still, the social change did not bring the depoliticisation of historiography, but rather ushered in an era of a new ideology (nationalism) and revisionism that accompanied it. In present-day Serbia, the discourse about the Syrmian Front is largely dominated by mass media, which – together with some professional historians – are offering biased and simplistic answers to this complex topic, sometimes bordering on conspiracy theories.[2] The course of events in Syrmia is largely unknown outside the former Yugoslavia. Prior to the early 2000s, very few historians from the West researched the military side of the conflict, preferring to focus on the politics behind it instead. The events on the Syrmian Front are usually mentioned only in passing, or a couple of paragraphs at best, and mostly from German perspective. Language barrier and difficulties in obtaining original Yugoslav documents also contributed to the lack of interest for this topic abroad.

This article will seek to redress this imbalance by providing a short description of the operations in Syrmia, followed by an analysis of the performance of the Partisan forces involved. As we shall see, there were compelling military reasons in favor of an active campaign as dictated by the dynamic of the Eastern Front and geographical and logistical issues. There can be no doubt, however, that both inner political considerations (showdown with domestic enemies) and rising tensions with the Western Allies over the disputed Italian-Slovene border played a significant part in the Yugoslav strategic planning. Ideological rigidness and mere reasons of prestige were responsible for much of the bloodshed. The Yugoslav leadership often failed to take into account the tremendous difficulties besetting their forces which at that time were going through a unique process of transformation into a regular army. Untrained men, inexperienced officers, lack of engineering equipment and armored vehicles, and total dependence on foreign sources for war materials are some of the reasons behind the extraordinary length and cost of the campaign.

The road to Syrmia was a long and bloody one: few of the original 12 000 Communist Party (KPJ) members who had served as the core of the Partisan movement in the summer of 1941 were still alive three years later. Nevertheless, through active campaigning, skillful exploitation of flaws in the German occupation system (most notably their support for the genocidal Ustasha regime in Croatia) and events abroad (surrender of Italy), as well as through pragmatic domestic (e.g. promises of social and ethnic equality) and foreign policies (securing material support from the Western Allies), the Partisans had emerged as the strongest Yugoslav faction by the late 1944. One of the key ingredients of their success lay in the regularization of the movement’s military branch (»People’s Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia«, NOVJ) which strengthened their inner cohesion and enabled the Partisans to gain the upper hand in their war against domestic enemies, and to stand up to foreign regulars in case of need. According to one German estimate from late September 1944, the NOVJ had some 102 000 men serving in 43 divisions.[3]

The arrival of the Red Army to Eastern Serbia that same month represents one of the key events in the history of the Second World War in Yugoslavia. In little less than a month, units belonging to the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts (UFs), assisted by some 16 NOVJ divisions and one Bulgarian army, routed the German »Army Detachment Serbia« (AAS), cut their main line of communications to Greece in the Greater Morava Valley, and liberated the capital city of Belgrade. Josip Broz Tito, the head of the Communist-dominated National Committee, was now firmly in control of Yugoslavia’s heartland with its rich natural resources and large population. Thousands of recruits now swelled the Partisan ranks, thus doubling the size of their divisions practically overnight. This new army was largely equipped by the Soviet Union: during his talks with Tito in Moscow in late September, Stalin promised arms for twelve rifle and two air divisions, as well as the know-how to use them.[4] With the long-cherished dream of creating a modern field force nearly fulfilled, the Partisan Supreme Headquarters set its eyes on the still occupied western parts of the country.

At the end of the third week of October, the strategic situation in the South-East Europe was as follows: the 2nd UF, with its left wing in northern Yugoslavia, was preparing for an advance into Hungary. The 3rd UF, minus one corps still in the Morava Valley, was hurriedly redeploying the rest of its forces from Serbia proper to the area north of Belgrade. Once concentrated, the front would proceed west along the Danube, thus forming the extreme left flank of the Red Army’s entire front reaching all the way to the Baltic. As the 3rd UF advanced deeper into Hungary, its left wing would become increasingly exposed to German attacks coming from across the great river and its tributary, the Drava. In order to avoid any such possibility, Tito agreed to deploy the bulk of the NOVJ forces from Belgrade to Syrmia. Their mission would be to advance through the Danube-Sava interfluve, preferably keeping pace with the tempo of Soviet operations.[5]

However, the German Commander-in-Chief South East, Field-Marshal Maximilian von Weichs, could hardly contemplate an offensive across the Danube at the time – or anywhere else for that matter. The situation facing his two Army Groups (»Heeresgruppe«) E and F (HGE, HGF) was growing more critical by the day. The former was stretched between northern Greece and western Serbia, trying to force its way west through the Dinaric Alps and at the same time thwart Soviet, Yugoslav, and Bulgarian attempts to cut off its retreat. HGF, severely shaken by the losses recently incurred in Serbia, had two difficult tasks to perform. First, it had to keep the supply routes in Bosnia and Croatia free of guerrillas and secure the Drina Valley for the arrival of HGE. Second, it had to maintain a link to Army Group South in Hungary and provide flank protection to the southern anchor of the German Eastern Front.[6] In light of these circumstances, Syrmia was thus of great strategic importance, and the Germans were warily awaiting the next enemy move in this area. One day after the Yugoslav capital had been lost, the diarist of the HGF wrote:

»The question is what the enemy will do after the fall of Belgrade. Cutting off the Syrmian pocket would be unpleasant but there are no particular indications for this. Deeply echeloned defense here makes quick evacuation possible.«[7]

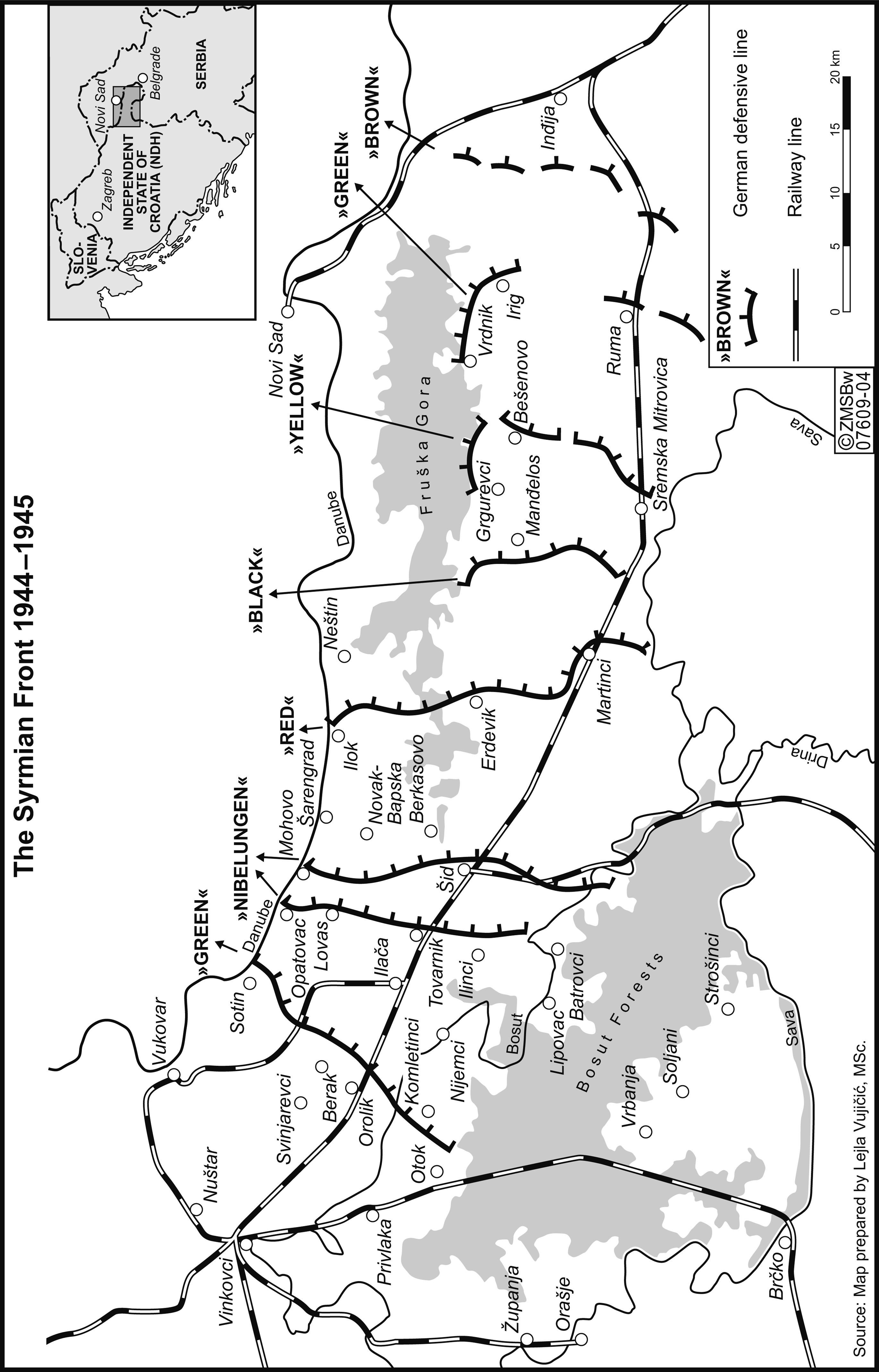

The »deeply echeloned defense« the document referred to consisted of altogether six defensive lines fortified to a varying degree that stretched across Syrmia at irregular intervals. Army Group F planned to withdraw from eastern Syrmia as slowly as possible in order to buy more time for the completion of the main fortified line centered on the town of Šid.[8] The second sentence reflected the fear that the enemy would strike westward towards the confluence of Drina and Sava, cross the former to the north and, possibly in combination with a similar move along the Danube, perform a deep double envelopment of the leftovers of the AAS which had managed to escape from Belgrade.

The Period of Partisan Initiative, October–December 1944

Ultimately, these apprehensions proved to be unfounded, as the Partisan leadership opted for a more modest approach: on 22 October 1944, the 12th (three divisions) and the 1st Proletarian Corps (PC) with one division, supported by five Soviet artillery regiments, began crossing the Sava at Belgrade and Obrenovac.[9] The main task of the group crossing at Obrenovac was to strike north and sever the road and railway communications between Ruma and Zemun and cut off the main enemy unit in the area, the »Division Böttcher«.[10] The Germans, however, would not oblige and retreated to the first and second defensive lines named »Brown« and »Green«. On 25 October 1944, the Soviet-Partisan forces attacked all along the front, with a main thrust aimed at the northern sector, where they hoped to outflank the lines with the help of local guerrilla units operating from the Fruška Mountain. Fearing encirclement, the Germans continued their fighting withdrawal before making a halt at Sremska Mitrovica on the 28th on Hitler’s express order. For the next several days, the Partisans looked for a weak spot in the German defenses, suffering an estimated 1200 casualties in the process. Although the »Yellow« line withstood all attacks up to this point, the mounting enemy pressure forced the HGF to issue another retreat order on the last day of October.[11] It was obvious, however, that the »Black« line, with its many deficiencies[12], could not be maintained for long and was ordered abandoned already five days later. In order to cover the evacuation and throw the Partisans off-balance, the Germans carried out a local counter-attack, codenamed »Draufgänger«. The operation was a success, and by 9 November, the Germans had taken up positions along the »Red« line, stretching from Sava to Danube.[13]

After almost three weeks of fighting, the two sides had fought each other to a standstill. In addition to heavy casualties and exhaustion, the tempo of NOVJ operations had been additionally slowed by continuous autumn rains which turned the terrain into a sea of mud. Although precise intelligence on enemy dispositions was sparse, one thing was clear: the Partisans were now facing a formidable defensive line consisting of trenches, prepared artillery and machine-gun emplacements, barbed-wire entanglements and elaborate mine fields. As any attack against these positions without adequate preparations seemed utterly futile, the Partisans went over to defense. The both sides used the respite to carry out reorganization and prepare for the next round of fighting.[14]

After the successful conclusion of the Batina-Apatin Operation on the Danube[15], the Allies felt it was time to renew their offensive in Syrmia. Tito and Marshal Fyodor I. Tolbukhin of the 3rd Ukrainian Front met in Belgrade from 17 to 20 November 1944 and agreed the arrival of the first sizeable Soviet contingent to the province. The main task of the reinforced 68th Rifle Corps (RC) was twofold: to seize the southern bank of the Danube and thereby open the great river for supply shipping and to act as a flank cover for the Soviet troops advancing through southern Hungary. The precise details of the corps’ employment were worked out with the HQ of the NOVJ’s 1st PC. According to the plan, the corps would punch a hole in the northern sector around Ilok while the Partisans would make a frontal attack along the remainder of the front. In order to facilitate the Soviet breakthrough, special details of Soviet and Yugoslav troops would cross the Danube behind German lines. The timetable was ambitious: the spearheads were supposed to reach the line Vukovar-Vrbanja on the second day of the offensive and from there continue the pursuit to the west.[16]

One Soviet and three Partisan divisions commenced their attack on the morning of 3 December 1944 after a strong artillery and air preparation. In spite of desperate German resistance, the »Red« line was pierced in the north and in the center after two days of heavy fighting. Having no more reserves left, Corps Group »Kübler« asked and got permission from HGF to withdraw to the west. This was hardly an ideal solution because the »Nibelungen« line was longer and less fortified than the previous one and was already outflanked by a Soviet-Partisan landing on the Danube. The NOVJ followed closely after the retreating Germans, capturing the important towns of Šid and Tovarnik. By 10 December, the Soviets stood before Sotin, and the Partisans had reached the critically important Brčko-Vinkovci railway line at Otok, which was being used for bringing Axis reinforcements from Bosnia.[17]

At this point, the offensive began to lose steam, but the Allies were not ready to give in yet: on 12 December 1944, the 1st PC issued an order for the continuation of operations on the 14th According to the plan, two Soviet and two Partisan divisions would attack on a ten kilometer wide front between Berak and Sotin towards Vukovar; the remaining Partisan units would launch diversionary attacks on their sectors.[18] This unimaginative plan, carried out largely by exhausted units against an alerted enemy failed to achieve anything but prolong the suffering in the front lines; all attacks were repulsed and the presence of fresh German reinforcements could already be felt. By 18 December 1944, after two weeks of bloody fighting, Partisan and Soviet forces on the Syrmian front had gone over to the defense.[19]

Not wanting to have a full (albeit exhausted) corps tied down in trench warfare on a front of secondary importance, the 3rd UF decided to withdraw all its units from Syrmia and replace them with the nominally strong 1st Bulgarian Army (six divisions with over 100 000 troops). Tito consequently ordered Dapčević on 17 December to make necessary amendments in his dispositions: Partisan units would forthwith be responsible for the section of the front south of the railway line Ruma-Vinkovci, the Bulgarians to the north of it.[20] These movements were supposed to be completed by the 22nd, in time to make yet another attempt against the »Green« line.[21] The new offensive lasted for six days and ended in a clear defeat: two Bulgarian divisions were stopped dead in their tracks in the north; by 27 December, the German 34th Army Corps[22] managed to relieve the garrison of Otok and push the Partisans back to their starting positions.[23] Heavy casualties and low morale of the troops compelled the HQ of the 1st Bulgarian Army (BA) to request the withdrawal from Syrmia and transfer to Hungary. As this coincided with Tito’s wish to have the 12th PC back to Yugoslavia as soon as possible, on 28 December Tolbukhin gave the green light for the relief of the corps by the 1st BA.[24] On the last day of 1944, the 1st PC issued its own set of orders for the takeover of the former Bulgarian sector. Under the new arrangements, the 1st and 5th NOVJD were deployed from Sotin to the Bosut River, with the 11th in reserve around Tovarnik; from Bosut all the way to the edge of the impenetrable forests south of Otok stood the now dangerously overstretched 21st NOVJD.[25]

The German counter-attack, January 1945

As the year 1944 drew to a close, the bulk of the HGE retreating from western Serbia and Montenegro had seemingly managed to overcome the Partisans, Bulgarians, and the Soviets, the rugged terrain and adverse weather, and was starting to arrive in the Drina Valley in force. Without stopping, units were speedily dispatched north in order to bolster the hard-pressed front in Syrmia and to build a new one along the Drava.[26] By the end of the month, three new divisions, the 11th Luftwaffe Field Division (LWFD), 297th Infantry Division (ID), and 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division »Prinz Eugen« (MD), were taking positions to the south of the Syrmian Front, with 41st Fortress Division (FD) concentrating further west around Brod. With these forces at hand, the German command could carry out the reorganization of fragmented units and, more importantly, contemplate a limited attack with the aim of neutralizing the Partisan threat to the railway line Brčko-Vinkovci.[27] On 3 January 1945, a German task force consisting of two reinforced regiments suddenly attacked the exposed 21st NOVJD and forced it into a headlong retreat to Bosut River.[28] Luckily for the Partisans, the ice was thick enough to support the weight of a man, and the division eventually managed to avoid a wholesale destruction. Faced with increasing resistance (elements of the 1st and 6th PD) and dwindling ammunition stocks, the HGE gave up some ground and ended the attack, content with inflicting considerable casualties in men and equipment on the enemy.[29]

The successful attack at Otok removed the immediate danger to the southern flank of the 34th AC, but the NOVJ was still in the possession of the »Nibelungen« line which had better defensive potential than the »Green«. HGE had therefore decided to conduct a much bigger operation, codenamed »Wintergewitter«, to recapture the former main line and deal a crippling blow to the Partisans. The plan envisaged the 7th SS MD and 117th JD achieving a breakthrough in the northern sector around Sotin and then racing to Tovarnik and Šid, thereby catching the bulk of the 1st NOVJ Army between themselves and the 41st FD attacking from the west.[30]

The operation began on 17 January 1945. Despite heavy resistance and the presence of Soviet ground attack aircraft,[31] German spearheads reached Tovarnik by the end of the day, forcing Dapčević to have his entire command fall back to the line Šarengrad-Nova Bapska-Berkasovo-Šid-Ilinci-Gradina.[32] The Germans continued their attack on the 18th along the whole front. By the end of the day the 117th JD had wrestled the control of Nova Bapska and Berkasovo from the 21st and 5th NOVJD. The focal point of fighting lay at the center, where the 1st PD obstinately defended the town of Šid until dusk when it was finally forced to withdraw. Although the 1st NOVJ Army managed to evade the encirclement, the 34th AC was satisfied with the results of the operation so far, as some of its units advanced further than originally planned. The corps therefore decided to conduct a gradual withdrawal as soon as the 41st FD had finished entrenching the new main defensive line running from Mohovo on the Danube across Lovas, Opatovac, Tovarnik, Ilinci to Batrovci on the Bosut River.[33] From 22 to 24 January, the Germans conducted a textbook example of fighting retreat, inflicting further heavy casualties on the pursuing Yugoslavs. On the 24th, the 1st Army cancelled its attack and ordered all units to dig in. The lines in Syrmia would remain static until April 1945.[34]

The Yugoslav Offensive in Syrmia, April 1945

Whereas February and March 1945 saw little activity on the Syrmian Front itself, the adjacent sectors on the Drava and Drina Rivers saw much fighting as the Germans tried to stabilize their flanks in a series of operations, with varying degrees of success.[35] Due to the rapidly worsening situation in Hungary, in late March Hitler grudgingly agreed to the gradual evacuation of the entire area south of the line Doboj-Brčko (84 km SSW Vinkovci) and the abandonment of the Syrmian Front in favor of a more compact position running roughly to the east of the line Brod-Donji Miholjac (ca. 60 km W Vinkovci).[36] The German command could only hope that these movements could be completed before the Yugoslavs started their spring offensive.

From 25 to 27 March 1945, Dapčević and his colleagues from the 2nd and 3rd Armies, Koča Popović and Kosta Nađ, attended a series of meetings with Tito in Belgrade in order to discuss the plan for the final offensive of the Yugoslav Army (official name since 1 March 1945) in Syrmia. Ultimately, it was decided to conduct the operation in three phases. The so-called »Bosnian Group« (two divisions and one tank battalion from the 1st Army and one division from the 2nd) would initially operate south of the Sava and clear the Sava-Drina triangle of enemy troops. This group would then capture the bridge at Brčko and strike north to Vinkovci. At the same time, two divisions and one cavalry brigade (»Bosut Group«), would advance between the rivers Spačva and Sava, and cut off the main enemy road communication linking Brčko and Vinkovci at Vrbanja. The main force, consisting of five divisions and two tank battalions of the 1st Army (»Northern Group«) would storm the northern end of the »Nibelungen« line with Vukovar and Vinkovci as their final objectives. The 3rd Army (three divisions) would cross the Drava at Valpovo and Osijek (50 and 30 km NW Vinkovci, respectively) and strike to Vinkovci or advance to Našice (60 km W Vinkovci), depending on the outcome of 1st Army’s attack. The task of the 2nd Army (four divisions) was to exert pressure on the Bosna River valley and protect the left flank of the 1st Army. The third phase of the operation was reserved for the destruction of all German units caught to the east of Vinkovci. The entire operation was to last no more than twelve days.[37]

The concentration of the »Bosnian Group« coincided with the withdrawal of the southern wing of the 34th AC to the so-called »Brčko Bridgehead«. Yugoslav divisions followed closely behind, facing tough resistance by the German 22nd ID and heterogeneous but numerically strong collection of collaborationist troops. By the evening of 7 April, Yugoslav forces had captured Brčko, but the Germans managed to escape across the river; worst of all, their engineers blew up the crucial Sava Bridge at the last moment.[38] This, in turn, meant that the river had to be forded, and the »Bosnian Group« at the time had no bridging equipment. It took two full days (10–12 April) to assemble all infantry units on the northern bank. They went into action unsupported, because it took two more days to get the artillery and tanks across.[39]

The »Bosut Group« started its operations on 3 April 1945. While one division was making diversionary attacks against the southern anchor of the main German defensive line around Batrovci and Lipovac, the remainder of the group crossed the swampy Bosut Forests and became embroiled in costly fighting for the villages astride the main railroad. As soon as the last elements of the 22nd ID passed to north and north-west, the German rear-guards disengaged and the Yugoslav units occupied Vrbanja without a fight on the 12th. The newly formed »Southern Group« of the 1st Army (5th, 6th, 11th and 17th Divisions) was badly behind schedule: the distance by air to the next objective, Otok, was approximately twenty kilometers, but the journey would take longer than usual because the units would have to traverse the Bosut Forests once more.[40]

The slow advance of the »Bosut« and »Bosnian« groups had repeatedly changed the timetable of the entire 1st Army until the date of »the big push« was finally set for 12 April 1945. As before, the main point of effort would be in the northern sector on the approximately six kilometers-wide stretch of land between Novak-Bapska and Šarengrad. The 1st PD and 21st NOVJD would attack there, each supported by one battalion of the 2nd TB; after achieving a breakthrough, these units would advance west to the line Vukovar-Svinjarevci. The 48th NOVJD had a twin-task of supporting the drive west and rolling up the rest of the German line from the north. Further south, the 42nd NOVJD would frontally attack Tovarnik, and the 22nd NOVJD would cross the Bosut and assail the southern-most end of the German front. Facing these Yugoslav units stood the heavily entrenched 41st ID reinforced with one fortress brigade, German-Arab and Northern Caucasus legionnaire battalions and some NDH units.[41]

At precisely 0445 hours, a barrage by some 150 guns heralded the beginning of a long-awaited offensive of the 1st Yugoslav Army on the Syrmian Front. The shells kept landing on the German forward positions for fifteen minutes, after which the fire was redirected to the second line. At 0500 hours, soldiers sprang from cover and raced towards the trenches held by three battalions of the 963rd Fortress Brigade which had replaced the 117th JD several days earlier. The attack must have appeared anticlimactic to the veterans of the earlier battles: stunned defenders offered little resistance, and in some places, the first German line was captured in less than ten minutes.[42] Yugoslav units continued their westward advance with the support of some forty T-34/85 medium tanks and covered by an air umbrella provided by the 11th and 42nd Air Divisions. Within four hours, advance guard reached one brigade of the 21st NOVJD which had crossed the Danube at Opatovac the previous night. At the same time, other spearheads cut the Tovarnik-Vukovar road and encircled the enemy strongpoint at Lovas. By the late afternoon, the 1st PD had broken the resistance of the 606th Security Regiment and NDH forces and captured Vukovar. The 21st NOVJD had likewise fulfilled its daily objectives and took Svinjarevci.[43]

The going in the south was much slower and a good deal bloodier. All attempts by the 42nd NOVJD to take heavily fortified Tovarnik failed, until the 48th NOVJD outflanked the town from the north using the breach created by the 1st and 21st Divisions. Finally, at about 1400 hours, the town was taken, and both Yugoslav divisions were now in a good position to strike west to Ilača and south to Ilinci, thereby rendering the position of the 41st ID untenable.[44] Help could not come too soon for the badly beleaguered 22nd NOVJD on the extreme left flank of the »Northern Group«. The initial advance across the Bosut and Spačva Rivers was halted by unexpectedly strong resistance and some Yugoslav units were nearly overrun by a series of German counter-attacks.[45] However, the rapidly worsening situation on the remainder of the front forced the 41st ID to call off further attacks and retire to the west.

In light of the deep Yugoslav penetration in the north and increasing pressure in the center around Tovarnik, at about one o’clock in the afternoon of 12 April 1945, HGE ordered the retreat to the line covering Županja, Vinkovci and Osijek.[46] There was no question of holding this position for any longer period, because the line had already been outflanked. At dawn, elements of all three divisions of the 3rd Army began crossing the Drava between Sveti Đurađ (67 km NW Vinkovci) and Osijek, with two additional landings to the east of the city and across the Danube at Dalj (25 km NE Vinkovci).[47] Whereas the smaller landings could, to a large degree, be neutralized, there was little the Axis[48] could do to prevent the main Yugoslav force from establishing bridgeheads on the southern bank. By the end of the day, the 16th and 36th NOVJD linked up at Valpovo, creating a bridgehead of approximately eight kilometers in width and depth. The 51st NOVJD faced much heavier resistance on the outskirts of the strategically important city of Osijek and its bridgehead was therefore only two kilometers deep. The Germans intended to keep the two Yugoslav groups separated by using the 11th LWFD and 1st Cossack Division in hope that this would win enough time for the 22nd and 41st ID to complete their withdrawal.[49]

On 13 April both Yugoslav armies continued their offensive on the entire front. In the course of the day, the 3rd Army managed to extend and link up its bridgeheads thereby creating a springboard for the attack on Osijek itself. The city was now endangered from the east as well by the 1st PD advancing from Vukovar (Osijek would fall one day later). The main task of the northern wing of the 1st Army was to capture Vinkovci. The garrison, which was made up primarily of NDH troops, could not withstand the combined pressure by two full Yugoslav divisions (21st and 48th) and the city was captured around 1800 hours. By then, however, the bag was largely empty: the sluggish advance of the 42nd and 22nd NOVJD from Bosut, and the equally slow march of the »Southern Group« to Vrbanja made it possible for the 34th AC to withdraw in relatively good order to the new main defensive line Sava-Đakovo-Našice-Donji Miholjac.[50]

With the taking of Vinkovci, the Syrmian Front ceased to exist. In operational terms, the 1st Yugoslav Army had won a bloody, but clear-cut victory: at the cost of some 606 killed, 2200 wounded, and four missing, as well as four destroyed and seven damaged tanks, it had successfully stormed the strongly fortified German line in Syrmia and advanced thirty to forty kilometers in two days, netting an estimated 2000 prisoners and large quantities of equipment.[51] In strategic terms, however, the offensive failed to deliver the desired results: the Germans managed to escape the trap, thus making any hopes for a quick advance to Zagreb and the country’s western borders illusory. In the several remaining weeks of the war, the HGE would continue its slow retreat to the Austrian border, at the same time thwarting all Yugoslav attempts to bring about a decisive battle of annihilation.[52]

The Performance of the Yugoslav Forces on the Syrmian Front

There is one question which should be answered before all else: why did the Yugoslav leadership keep the bulk of its forces in Syrmia and, all the difficulties notwithstanding, insist on achieving the breakthrough there regardless of the cost? First of all, the decision to deploy the NOVJ forces in Syrmia in late October 1944 was dictated in great part by the dynamic of the Eastern Front. The Soviets viewed their intervention in Yugoslavia as a side episode. They were eager to have their forces out of the country and deployed into southern Hungary as soon as possible. In these circumstances, the two NOVJ corps around Belgrade seemed ideally suited for advancing through Syrmia and providing protection to the southern flank of the 3rd UF. With little luck and some material aid, the hope was that the Partisans would be able to penetrate as far as Vukovar, thereby opening the Danube for Soviet river shipping. The Yugoslavs, for their part, had several good reasons to launch an active campaign in Syrmia. The Germans had to be pushed back from Belgrade as far as possible: there was a pervasive fear of a quick enemy dash to the capital which would inflict immeasurable political damage to the recently established Communist authorities there.[53] Furthermore, the axis from Belgrade across Syrmia and Slavonia to Zagreb seemed the most favorable in terms of geography (mostly flatlands and low hills) and communications (normal-gauge, largely double-tracked railway line) for any further westward advance.

If the first phase of the Syrmian campaign was determined largely by military considerations, it is difficult to say the same for the second. During the first months of 1945, the Germans were still offering stubborn resistance to Yugoslav operations in the interior of the country and along the Adriatic coast. At the same time, HGE was secretly sounding out the possibility of a gradual withdrawal from the country, promising all its heavy equipment in return. The Yugoslavs for their part kept demanding an immediate and unconditional surrender for two reasons: first, there was an overriding wish to not allow the Germans to escape unpunished for four years of an extraordinarily brutal occupation. Second, a surrender of an entire German army group would immeasurably raise the standing of the new Yugoslav government, both at home and abroad. Unsurprisingly, the talks failed to produce any results, but they had revealed that the HGE command was not unsympathetic to the idea of transforming itself into the nucleus of the future army of an independent Austria when the right time came.[54] The Yugoslavs feared that, if left unassailed, this powerful military formation would maintain its position in the country for as long as possible and then either surrender itself and the territory it controlled to the Western Allies, or simply become their auxiliary force.[55]

In addition to the German unwillingness to lay down their arms, Tito was extremely anxious about the speed of the Anglo-American advance in Italy in light of the crisis over the Julian March and the city of Trieste. The British and the Americans were resolved to have this region remain a part of Italy as per provisions of the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920. On the other hand, the new Yugoslav government owed much of its popularity to promises of annexation of these lands, where Croats and Slovenes constituted the majority of the population, and was naturally keen to fulfill them. Tensions were only exacerbated by the British intervention in Greece in October 1944 and their tentative plans for landings in Istria.[56] Second, Belgrade was apprehensive regarding the large concentration of collaborationist forces in the western Yugoslav provinces, which were still holding out exclusively due to the German presence in the country. These forces were heterogeneous in nature (as in the cases of the Croatian Ustashas, Serbian Chetniks and Zbor militiamen, and the Slovene Domobranci), but united in their fierce anti-communism. It was no secret that all of these groups were hoping to switch sides at the very moment of German surrender and present a ready-made bridgehead for the Western Allies in case their friction with the Yugoslavs erupted into a full-blown war.[57]

In late March 1945, Belgrade could do little to counter these potential threats. The only formation within striking distance from the border was the 4th Army with some 40–50 000 troops deployed in the northern Croatian littoral.[58] This army could not be expected to break the German defenses in the region, defeat the collaborationists and occupy the border in strength all by itself. Furthermore, its heavy weapons largely came from the Western Allies, who also provided the bulk of necessary supplies. Owing to tense relations with the latter, the army could have found itself virtually cut off at any given moment. Partisan units in Slovenia were still a relatively weak and lightly armed guerrilla force and did not present a serious deterrent to a possible intervention from abroad. The only way to nip the potential Vendée in the bud and add real weight to the Yugoslav claim to Julian March was to get the bulk of the army – still tied down in Syrmia – to the western borders as quickly as possible. This in turn could only be done by an immediate offensive against the German fortified line between the Danube and the Sava, despite the fact that the preparations were far from complete.

Defeating their hated, but respected foe in a set-piece battle became something of an obsession for the Yugoslavs, or at least for their political and military leadership. It was regarded as an ultimate test of maturity, proof that the army had mastered the art of regular warfare. Furthermore, a successful outcome of the operation would boost national pride by reinforcing the notion that the Yugoslav peoples had liberated themselves with little or no help from the outside. Tito was probably also thinking of the battle in terms of the party’s standing with the Soviet Union. Stalin chided him once for the poor performance of the NOVJ and compared it unfavorably to the Bulgarian army – something the Yugoslav Communists were very sensitive about, given their long-standing animosity towards the Bulgarians. The Cominform Crisis of 1948 was still in the distant future, and victory in Syrmia would show Moscow that it could count on the Yugoslav armed forces in the insecure post-war world.[59]

The campaign in Syrmia was undoubtedly the longest and bloodiest fought by the Yugoslav Partisans during the Second World War. It took almost six months and at least 13 000 killed[60] to cover the distance of some 140 kilometers between Belgrade and Vinkovci and open the road to Zagreb. The reason for such high cost in time and blood lay in the fact that the NOVJ was, for the first time, waging a fully regular campaign of the type their enemy excelled at. At least until April 1945, both the Soviets and the Germans had rightly questioned the ability of the Yugoslavs to hold a part of a front on their own, not to mention achieving any decisive success on the offensive. The NOVJ was still perceived as a force whose real strength lay in irregular tactics.[61] Unlike in the neighboring Slavonia and Eastern Bosnia, the NOVJ units in Syrmia had a very limited opportunity to employ guerrilla tactics: turning the northern flank of the German front by using the cover provided by the Fruška Mountain in October-November 1944 constitutes practically the only such example. After that, confines of the operational area (the stretch of land between Danube and Sava) and the peculiarities of the countryside (flat, open terrain) meant that the Yugoslavs had to face the enemy head-on. Under these conditions, the heterogeneous but expertly led collection of German battle groups, fighting behind a series of strong defensive positions, proved to be more than a match for unexperienced and under-equipped Partisan forces.[62] Even had the NOVJ had the chance to boost its capabilities by switching between regular and irregular tactics more often, it is highly unlikely that this approach would yield the kind of results the Partisans were after. Simply put, the war could not be won by ambushes and evasion maneuvers.

All said, it was little wonder that the NOVJ, consisting of untrained men led by officers with no knowledge of regular warfare, suffered such heavy casualties. In the beginning, the only tactic these troops could be reasonably expected to execute was a swift dash over no-man’s land in order to overwhelm defenders by sheer weight of numbers. Inexperienced as they were, soldiers huddled under fire which made them even better target for machineguns and mortars. Mines were an especially feared weapon, as no Partisan, whether a conscript or veteran, had seen it employed on such a scale before. Since specialized equipment was not available for the better part of the campaign, some units improvised by driving cattle herds before them, hoping that the unfortunate animals would clear a path through the minefields.[63] »Tank scare« was widespread, as most men faced armored vehicles in the open for the first time. The 1st PC relied mostly on the Soviet anti-tank detachments for protection until they were withdrawn in late December 1944. Yugoslav units which replaced them still had neither adequate training nor experience to effectively counter the mass employment of armor by the Germans in their January attacks.[64] Casualties could have been lower had the Yugoslavs at least had any helmets. It appears that no one had thought of this unglamorous, but important piece of equipment when requesting military aid from the Soviets, and consequently the men had to endure artillery barrages with nothing else but the standard-issue »titovka« (Yugoslav forage cap) to protect their heads. Yet the biggest problem of the NOVJ lay in the fact that it had taken a long time before it learned the importance of digging in. Like helmets, shovels were not provided to units in Belgrade, and one high-ranking officer later candidly admitted that »we were not particularly interested in them«.[65] Entrenching was widely considered unmanly and not becoming of a soldier: some Vojvodina Partisans could at first not understand why the soldiers of the supposedly »heroic« Red Army were so persistent in digging foxholes; on one occasion, a Partisan unit charged an enemy strongpoint in Syrmia because »the men could not bear to stay in water-filled trenches any longer«.[66] It took many casualties and prolonged propaganda campaign under the motto »more sweat – less blood« until both officers and men finally acknowledged the necessity of being properly entrenched. By April 1945, the 1st Army had dug an estimated 600 kilometers of trenches in its area of responsibility.[67]

Let us now examine the difficulties facing the NOVJ/Yugoslav Army in more detail. First of all, the NOVJ’s officer corps, while well-versed in guerrilla tactics, had only limited knowledge of regular operations. This becomes apparent if we look at the biographies of leading commanders on both sides of the Syrmian Front on the eve of the German counter-attack in early January 1945. The commander of the German 34th AC, as well as two out of his three divisional commanders were veterans of World War One; the third had been on active service since 1939 and rose through the ranks to become a general; all had at least one year of experience in leading formations of the size now entrusted to them. On the NOVJ side, the situation was entirely different: the 1st Army’s commander had held the rank of lieutenant in the Spanish Republican Army; out of his five divisional commanders, two were junior officers in the Yugoslav Royal Army, one was an NCO, and two were mere privates. None of these men, with the exception of Dapčević, had any experience in handling formations of more than 5000 men prior to November 1944.[68]

The problem of qualified command cadre was further exacerbated by extraordinarily high casualty rates among officers and NCOs. To give a few examples: the 38th NOVJD (the 2nd Army) had forty killed and over a hundred wounded officers and NCOs in January 1945 alone; the 8th Vojvodina Brigade (the 3rd Army) lost forty percent of its command cadre during the fighting on the Drava in mid-March of the same year; the 11th NOVJD (the 1st Army) lost two out of its four brigade commanders on 7 April 1945.[69] The Partisans took a pragmatic approach in the attempt to offset the losses. In addition to promoting the bravest and most able soldiers to command positions, the NOVJ frequently employed former royal officers in staff duties. Likewise, Yugoslav nationals who had learned military skills in German formations were a welcome asset and were, if proven loyal, often made NCOs.[70]

The propensity of the ranking personnel to lead their men into battle gun in hand, once viewed as an admirable virtue, was now under Soviet influence being branded by the pejorative term »Partizanština« (roughly »doing things the Partisan way«). Communist Party (KPJ) organizations within the army had the task of rooting out the old habits inherited from the days of guerrilla army, including informality, sloppy paperwork and unsoldierly conduct.[71] Soon, however, due to dogmatism and burning desire to mimic the Red Army in all things military, the suppression of »Partizanština« also began to target positive experiences learned during four years of insurgency, like self-initiative of field commanders and tactical flexibility. As a result, commanders on divisional and even brigade level preferred conducting all their business from the comparative safety of their far-off headquarters (»uštabljivanje«), at the same time insisting on immediate fulfillment of orders, regardless of conditions and consequences.[72] This approach had cost the NOVJ/Yugoslav Army dearly, as it usually resulted in poor coordination and rigid adherence to a pre-planned pattern of attacks which the Germans had little trouble in fending off.[73]

The story of the NOVJ’s intelligence effort on the Syrmian Front and adjoining sectors is one of unqualified failure. Lack of experienced cadre and irregular exchange of information between staffs and intelligence-gathering bodies meant that the NOVJ/Yugoslav Army was largely operating »in the dark« as far as enemy intentions and dispositions were concerned. For instance, the 1st PC had no data on the strength of the »Yellow« line which resulted in heavy casualties in fighting around Sremska Mitrovica in late October and early November 1944. On the eve of the December offensive, the Soviet 68th RC found out that the distance to enemy trenches was no less than five times greater than originally reported by the Partisans. The German attack at Otok on 3 January 1945, which achieved full surprise, failed to stir the 1st Army into paying more attention to enemy troop movements. Consequently, Tito went ahead with his visit to the front on 16 January totally oblivious to the looming danger which materialized itself only one day later in the form of the operation »Wintergewitter«. Only on 25 January 1945 did the Supreme HQ issue instructions on proper handling of intelligence tasks in conditions of regular warfare.[74]

The NOVJ/Yugoslav Army had one clear advantage over its German foe and that was numerical superiority. Serbia, with its large population, now became the main source of manpower: from early November 1944 to late January 1945, some 280 000 persons were conscripted into the army. As a result, the strength of an average Partisan division increased abruptly from approximately 3000 to 10 000 men. In words of Koča Popović, however, countless difficulties besetting the army in this period meant that the actual fighting strength corresponded to »less than ten percent« of its numerical strength.[75] Huge influx of new conscripts, vast majority of who were »untrained peasant youths and schoolboys«,[76] diluted the cohesion and fighting prowess of old Partisan units which also had to provide the command cadre for the newly raised formations.[77]

There was little time for training during the early phase of the campaign. The 1st PC attempted to rotate units as frequently as possible, but the pace of operations in Syrmia would allow them several weeks of rest at best. Only after comparative peace had set in in late January 1945 could the Yugoslavs devote more attention to this all-important issue. The first thing to do was to provide enlisted men with four-week basic training (invariably including »political lectures«) and organize short courses for NCOs and officers. Anticipating the upcoming offensive, by late March the curriculum was expanded to include storming of fortified lines, combined arms operations and tactics of pursuit. Not forgetting the German penchant for armor, soldiers were taught tank-fighting techniques in live exercises with captured enemy vehicles.[78] Due to the fact that the 1st Army’s area of responsibility was intersected by several rivers and the swampy terrain of the Bosut forest area, special emphasis was laid on the creation of an effective engineering arm: in addition to the already existing engineer battalions at divisional level, an independent engineer brigade was formed in early Mach 1945.[79] Apart from bridging and construction tasks, the sappers’ main effort was directed at mastering the intricacies of German minefields, an essential prerequisite for any offensive in Syrmia.

Soviet influence on the Yugoslav army’s organization and training deserves a special mention. As we have seen, Stalin was very forthcoming in complying with the Partisans’ request for material aid and technical assistance: they were considered politically reliable and, if properly equipped and trained, could prove militarily useful as well. The quantity and the quality of Soviet help compared favorably to that of the Western Allies, who were often accused of handing out obsolete weapons and supplies »by the spoonful« and conditioning them with demands of political concessions. Indeed, the Partisan leadership suspected that the British in fact did not wish to see the NOVJ transformed into a regular force, and were therefore delaying their deliveries of modern equipment and training of Yugoslav airmen. With an alternative source of assistance secured, Tito »took all of his money and placed the bet on his other ally«, at the same time hardening his stance towards the British.[80]

The Red Army was revered by the Partisans, not solely because of ideological ties or Pan-Slavism, but also because of its combat record and vast experience. The Yugoslavs were therefore happy to have Soviet personnel in their midst. In addition to the staff attached to the General Staff in Belgrade, each Yugoslav army HQ was provided with a liaison, and each division armed with USSR-made weapons with a small team of instructors (the same went for independent artillery and communications units). Their continuous presence with units in the field was especially important in light of the fact that the Yugoslav specialist schools had begun to open only in early 1945 and it took them months to turn out first graduates. The curriculum at these schools was based entirely on Russian literature, as well as experiences from the Eastern Front; at least 20 Soviet infantry officers were employed as teachers.[81] The process of sovietisation of the Yugoslav army reached its peak in the early spring, when divisions were reorganized along the Red Army pattern (sacrificing a fourth of their strength for increased firepower and mobility) and were even re-branded as »rifle«. The reorganization, however, could be only partially completed by the time for the April offensive.[82]

Soviet learnings were increasingly felt in disciplinary measures as well. Prior to late 1944, the Partisans were proud of their superior esprit-de-corps, which they thought had rested primarily on voluntary discipline and a highly developed sense of belonging to the only true »people’s army« in the country. If the KPJ army cells’ meetings (there was one in every company) or the highly developed propaganda failed to produce the desired effect on the morale and discipline, commanders would then resort to punishment. This very often included a brief court-martial followed by an execution, even for petty offences. The combination of simple, idealistic rules of conduct and a swift application of justice in cases of infringement appealed to the rank and file of relatively small Partisan units, most of whom were volunteers. The mass mobilization which followed the liberation of Serbia changed all this. Vast majority of new recruits knew little about the war or the Partisan ideals. Indeed, many of them had heard of Communists only through the Axis propaganda, and some had even served in various anti-communist formations. The increasing size of units, lack of experienced cadre, and the pace of operations in Syrmia led to the neglect of »party work,« widely believed to be the main instrument for maintaining inner cohesion and morale. Heavy casualties and miserable living conditions on the front, especially during the early phase of the campaign, resulted in breakdown of discipline; many cases of maltreatment of civilians in the province led one high-ranking political commissar to exclaim that the Partisans »had become a professional [i.e. mercenary] army«.[83] Worse still, the NOVJ’s combat potential was slowly eroding due to mass desertions, self-inflicted wounds and even outright mutinies.[84] Following the Soviet recipe, the penal companies were formed at brigade level in December 1944, followed by penal battalions at army level in March 1945. Like in the Red Army, these units were sent on the most dangerous missions and were nearly wiped out in the process.[85] The opposing side had no such problems and the fact, that the German soldiers feared Yugoslav captivity more than death, contributed substantially to the Wehrmacht’s undiminishing fighting spirit during the last months of the war.

All three Yugoslav armies were equipped with a mixture of Soviet, Allied, and captured Axis weapons, and this naturally caused logistical problems. The Soviet weaponry began arriving right after the liberation of Belgrade, but it took another six months to refit all units of the 1st Army. Due to poor organization, units repeatedly received new weapons only days before going into action. As a result, soldiers had no time to learn how to use them to their full potential.[86] As there was no domestic production, the NOVJ was almost totally dependent on its allies for ammunition shipments.[87] That this could pose a serious problem is evident from the following examples. At the beginning of November 1944, the 21st NOVJD had to store its seven British mortars (out of altogether twelve available) because it had not received any shells for them in two months. One battalion of the 3rd Vojvodina Brigade was ordered to partake in the landing at Opatovac in early December 1944 despite the fact that one hundred of its men had only ninety rounds each for their Italian rifles; when the ammunition ran out, the soldiers panicked and fled.[88] Shortages persisted until the end of the campaign: the brevity of the Yugoslav barrage on the morning of 12 April 1945 was caused less by design than by the fact that the 1st Army had a very limited stock of artillery ammunition.[89]

In the end, it turned out that the 1st Army needed respite more than anything else. During the quiet period on the Syrmian Front between late January and early April 1945, the units were brought up to strength, rested and trained in the use of their new equipment. Whereas it is true that the army enjoyed overwhelming superiority by the time the great offensive began (five Yugoslav to one-and-a-half German divisions), the breakthrough was not achieved by the sheer weight of numbers alone. Artillery preparation was short but effective, owing to detailed reconnaissance of enemy firing positions; Yugoslav air-crews had likewise given a good account of themselves by providing close air-support to ground troops; German minefields, which had thwarted so many attacks in the past, were largely rendered ineffective by tireless engineering efforts; sappers had also dug approach trenches to within 150–200 meters of the enemy lines in order to provide the advancing infantry with as much cover as possible.[90] Regardless of this obvious improvement, the ambitious intention to encircle the entire German 34th AC in Syrmia was clearly beyond the army’s capabilities at the time. The plan called for forcing of two major rivers and a swift strike into the enemy rear (partly through heavily forested terrain) despite the fact that one pincer arm (the 3rd Army) had no tanks, and the other (the 1st Army) had no adequate bridging equipment. Even more striking is the fact that the Yugoslavs went ahead with it although they had no mobile reserves standing ready to exploit gaps in the German defenses, as all three tank battalions and the single cavalry brigade were relegated to infantry-support role. Basically, the Yugoslav Army attempted to conduct a World War Two operation with the means and tactics of World War One.

© 2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Artikel

- »Si vis societatem para ad militiam.«

- Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern im Ersten Weltkrieg

- Ein »anderer« Oberbefehlshaber?

- Carnage in the Land of Three Rivers: The Syrmian Front 1944–1945

- Nachrichten aus der Forschung

- »Kiel und die Marine 1865–2015. 150 Jahre gemeinsame Geschichte.«

- »Besatzungskinder und Wehrmachtskinder – Auf der Suche nach Identität und Resilienz.«

- »Globaler Krieg. Visionen und ihre Umsetzung.«

- »Nachkrieg und Medizin in Deutschland im 20. Jahrhundert.«

- »Gewaltkulturen von den Kolonialkriegen bis zur Gegenwart.«

- »Der Krieg ist vorbei. Heimkehr – Trauma – Weiterleben.«

- »Geschichtsbewusstsein als soldatische Kernkompetenz. 60 Jahre Historische Bildung in der Bundeswehr.«

- Buchbesprechungen: Allgemeines

- Ulrich March, Grundzüge der Militärgeschichte. Krieg und politische Kultur, Aachen: Helios 2014, 141 S., EUR 16,50 [ISBN 978-3-86933-112-6]

- Die Dienstbibliothek des Brandenburg-Preußischen Hausarchivs. Katalog, bearb. von Herzeleide Henning, Berlin: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz 2015, XII, 806 S. (= Veröffentlichungen aus den Archiven Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Arbeitsberichte, 17), EUR 27,00 [ISBN 978-3-923579-24-2]

- Stadt und Krieg. Leipzig in militärischen Konflikten vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. Hrsg. von Ulrich von Hehl, Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverl. 2014, 531 S. (= Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte der Stadt Leipzig, 8), EUR 62,00 [ISBN 978-3-86583-902-2]

- Urte Evert, Die Eisenbraut. Symbolgeschichte der militärischen Waffe von 1700 bis 1945, Münster, New York: Waxmann 2015, 376 S. (= Beiträge zur Volkskultur in Nordwestdeutschland, 125), EUR 44,90 [ISBN 978-3-8309-3217-8]

- Marco Sigg, Der Unterführer als Feldherr im Taschenformat. Theorie und Praxis der Auftragstaktik im deutschen Heer 1869 bis 1945, Paderborn [u. a.]: Schöningh 2014, IX, 504 S. (= Zeitalter der Weltkriege, 12), EUR 46,90 [ISBN 978-3-506-78086-7]

- Stefan Troebst, Erinnerungskultur – Kulturgeschichte – Geschichtsregion. Ostmitteleuropa in Europa, Stuttgart: Steiner 2013, 440 S. (= Forschungen zur Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Mitteleuropa, 43), EUR 64,00 [ISBN 973-3-515-10384-8]

- Arnold Suppan, Hitler – Beneš – Tito. Konflikt, Krieg und Völkermord in Ostmittel- und Südosteuropa, 3 Bde, Wien: ÖAW 2014, XIV, 2048 S. (= Internationale Geschichte, 1), EUR 148,00 [ISBN 978-3-7001-7309-0]

- Gerd Krumeich, Deutschland, Frankreich und der Krieg. Historische Studien zu Politik, Militär und Kultur. Hrsg. von Susanne Brandt, Thomas Gerhards und Uta Hinz, Essen: Klartext 2015, VI, 484 S., EUR 24,95 [ISBN 978-3-8375-1040-9]

- Mythes et tabous des relations franco-allemandes au XXe siècle./Mythen und Tabus der deutsch-französischen Beziehungen im 20. Jahrhundert. Éd. par/hrsg. von Ulrich Pfeil, Bern [u. a.]: Lang 2012, X, 312 S. (= Convergences, 65), EUR 69,10 [ISBN 978-3-0343-0592-1]

- Buchbesprechungen: Altertum und Mittelalter

- Martin Hofbauer, Vom Krieger zum Ritter. Die Professionalisierung der bewaffneten Kämpfer im Mittelalter, Freiburg i.Br.: Rombach 2015, VI, 226 S. (= Einzelschriften zur Militärgeschichte, 48), EUR 24,80 [ISBN 978-3-7930-9770-9]

- The Medieval Way of War. Studies in Medieval Military History in Honor of Bernard S. Bachrach. Ed. by Gregory I. Halfond, Farnham [u. a.]: Ashgate 2015, XVI, 332 S., £ 75.00 [ISBN 978-1-4724-1958-3]

- Peter Blickle, Der Bauernjörg. Feldherr im Bauernkrieg. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg 1488–1531, München: Beck 2015, 586 S., EUR 34,95 [ISBN 978-3-406-67501-0]

- Buchbesprechungen: Frühe Neuzeit;

- Frieden übersetzen in der Vormoderne. Translationsleistungen in Diplomatie, Medien und Wissenschaft. Hrsg. von Heinz Duchhardt und Martin Espenhorst, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2012, 286 S. (= Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz. Beihefte, 92), EUR 54,99 [ISBN 978-3-525-10114-8]

- Axel Gotthard, Der liebe vnd werthe Fried. Kriegskonzepte und Neutralitätsvorstellungen in der Frühen Neuzeit, Köln [u. a.]: Böhlau 2013, 964 S. (= Forschungen zur kirchlichen Rechtsgeschichte und zum Kirchenrecht, 32), EUR 128,00 [ISBN 978-3-412-22142-3]

- Militär und Mehrsprachigkeit im neuzeitlichen Europa. Hrsg. von Helmut Glück und Mark Häberlein, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2014, 256 S. (= Fremdsprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 14), EUR 58,00 [ISBN 978-3-447-10299-5]

- Steffen Leins, Das Prager Münzkonsortium 1622/23. Ein Kapitalgeschäft im Dreißigjährigen Krieg am Rande der Katastrophe, Münster: Aschendorff 2012, 208 S., EUR 29,00 [ISBN 978-3-402-12951-7]

- Konrad Kramar und Georg Mayrhofer: Prinz Eugen. Heros und Neurose, St. Pölten [u. a.]: Residenz 2013, 253 S., EUR 21,90 [ISBN 978-3-7017-3289-0] Elisabeth Großegger: Mythos Prinz Eugen. Inszenierung und Gedächtnis, Wien [u. a.]: Böhlau 2014, 406 S., EUR 39,00 [ISBN 978-3-205-79501-8]

- Militär und Gesellschaft in Preußen. Quellen zur Militärsozialisation 1713–1806. Archivalien in Berlin, Dessau und Leipzig. Teil 1, Bd 1: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz (1. Hälfte), XXX, 533 S.; Teil 1, Bd 2: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz (2. Hälfte), V, 861 S.; Teil 2: Weitere Archive, Bibliotheken und Museen in Berlin, Dessau und Leipzig, V, 185 S.; Teil 3: Indices und Systematiken, IX, 412 S. Hrsg. von Jürgen Kloosterhuis [u. a.]; bearb. von Peter Bahl, Claudia Nowak und Ralf Pröve, Berlin: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz 2015 (= Veröffentlichungen aus den Archiven Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Arbeitsberichte 15, 1–4), EUR 85,00 [ISBN 978-3-923579-22-8]

- Buchbesprechungen: 1789–1870

- Napoleon on War. Ed. by Bruno Colson. Transl. by Gregory Elliott, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2015, VIII, 484 S., £ 27.99 [ISBN 978-0-19-968556-1]

- Revisiting Napoleon’s Continental System. Local, Regional and European Experiences. Ed. by Katherine B. Aaslestad and Johan Joor, Basingstoke [u. a.]: Palgrave Macmillan 2015, XIX, 290 S. (= War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850), £ 68.00 [ISBN 978-1-137-34556-1]

- Klaus-Jürgen Bremm, Die Schlacht. Waterloo 1815, Darmstadt: Theiss 2015, 256 S., EUR 24,95 [ISBN 978-3-8062-3041-3]

- Adam Zamoyski, 1815. Napoleons Sturz und der Wiener Kongress. Aus dem Engl. von Ruth Keen und Erhard Stölting, München: Beck 2014, 704 S., EUR 29,95 [ISBN 978-3-406-67123-4]

- Reinhard Stauber, Der Wiener Kongress, Wien [u. a.]: Böhlau 2014, 285 S., EUR 19,99 [ISBN 978-3-8252-4095-0]

- Brian E. Vick, The Congress of Vienna. Power and Politics after Napoleon, Cambridge, MA, London: Harvard University Press 2014, VIII, 436 S., $ 45,00 [ISBN 978-0-674-72971-1]

- Karl-Heinz Reger, »Dann sprang er über Bord«. Alltagspsychologie und psychische Erkrankung an Bord britischer Schiffe im 19. Jahrhundert, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2014, 525 S., EUR 59,99 [ISBN 978-3-525-30066-4]

- Buchbesprechungen: 1871–1918

- Max Lehmann, Bismarck. Eine Charakteristik. Hrsg. von Gertrud Lehmann. Mit Beitr. zur Neuausgabe von Gerd Fesser und Helmut Donat sowie mit einer Zeittafel und Bibliografie, Bremem: Donat 2015, 352 S. (= Schriftenreihe Geschichte & Frieden, 31), EUR 16,80 [ISBN 978-3-943425-47-5]

- Ernst Dietrich Baron von Mirbach, Prinz Heinrich von Preußen. Eine Biographie des Kaiserbruders, Köln [u. a.]: Böhlau 2013, 645 S., EUR 39,90 [ISBN 978-3-412-21081-6]

- Jürgen Angelow, Der Weg in die Urkatastrophe. Der Zerfall des alten Europa 1900–1914, Berlin: be.bra 2010, 208 S. (= Deutsche Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert, 2), EUR 19,90 [ISBN 978-3-89809-402-3]

- Jörg-Michael Hormann und Eberhard Kliem, Die Kaiserliche Marine im Ersten Weltkrieg. Von Wilhelmshaven nach Scapa Flow, München: Bucher 2014, 161 S., EUR 29,99 [ISBN 978-3-7658-2031-1]

- Jürgen Gottschlich, Beihilfe zum Völkermord. Deutschlands Rolle bei der Vernichtung der Armenier, Berlin: Links 2015, 343 S., EUR 19,90 [ISBN 978-3-86153-817-2]

- Sergej Nelipovič, Krovavyj oktjabr’ 1914 goda [Der blutige Oktober des Jahres 1914], Moskau: Minuvshee 2013, 803 S., RUB 600,00 [ISBN 978-5-902073-95-6]

- Pis’ma s vojny 1914–1917 [Briefe aus dem Krieg 1914–1917]. Hrsg. von A.B. Astašov und P.A. Simmons, Moskau: Novyj chronograf 2015, 795 S. (= Ot pervogo lica. Istorija Rossii v vospominanijach, dnevnikach, pis’mach [Aus erster Hand. Die Geschichte Russlands in Erinnerungen, Tagebüchern, Briefen]) [ISBN 978-5-94881-272-4]

- Sebastian Schaar, Wahrnehmungen des Weltkrieges. Selbstzeugnisse Königlich Sächsischer Offiziere 1914 bis 1918, Paderborn [u. a.]: Schöningh 2014, VII, 333 S. (= Zeitalter der Weltkriege, 11), EUR 39,90 [ISBN 978-3-506-77998-4]

- Buchbesprechungen: 1919–1945

- Brian E. Crim, Antisemitism in the German Military Community and the Jewish Response, 1914–1938, Boulder, CO [u. a.]: Lexington Books 2014, XXV, 203 S., $ 85.00 [ISBN 978-0-7391-8855-2]

- Benjamin Ziemann, Veteranen der Republik. Kriegserinnerungen und demokratische Politik 1918–1933. Aus dem Engl. von Christine Brocks, Bonn: Dietz 2014, 381 S., EUR 24,90 [ISBN 978-3-8012-4222-0]

- Loretana de Libero, Rache und Triumph. Krieg, Gefühle und Gedenken in der Moderne, München: Oldenbourg 2014, X, 447 S. (= Beiträge zur Militärgeschichte, 73), EUR 39,95 [ISBN 978-3-486-71348-0]

- Mass Killings and Violence in Spain, 1936–1952. Grappling with the Past. Ed. by Peter Anderson and Miguel Ángel del Arco Blanco, London, New York: Routledge 2015, VIII, 234 S., $ 140.00 [ISBN 978-0-415-85888-5]

- Wolfram Pyta, Hitler. Der Künstler als Politiker und Feldherr. Eine Herrschaftsanalyse, München: Siedler 2015, 846 S., EUR 39,99 [ISBN 978-3-8275-0058-8]

- Günter Nagel, Wissenschaft für den Krieg. Die geheimen Arbeiten der Abteilung Forschung des Heereswaffenamtes, Stuttgart: Steiner 2012, 708 S. (= Pallas Athene, Beiträge zur Universitäts- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte, 43), EUR 92,00 [ISBN 978-3-515-10173-8]

- Ralf Blank, Ruhrschlacht. Das Ruhrgebiet im Kriegsjahr 1943, Essen: Klartext 2013, 350 S., EUR 24,95 [ISBN 978-3-8375-0078-3]

- Martin Steinacher, Maurice Bavaud – verhinderter Hitler-Attentäter im Zeichen des katholischen Glaubens? Münster [u. a.]: LIT 2015, 129 S. (= Anpassung – Selbstbehauptung – Widerstand, 38), EUR 29,90 [ISBN 978-3-643-12932-1]

- Ilse-Margret Vogel, Über Mut im Untergrund. Eine Erzählung von Freundschaft, Anstand und Widerstand im Berlin der Jahre 1943–1945. Hrsg. von Jutta Hercher und Barbara Schieb, Berlin: Lukas 2014, 221 S. (= Schriften der Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand, Reihe B: Quellen und Zeugnisse, 5), EUR 19,80 [ISBN 978-3-86732-157-0]

- Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland 1933–1945, Bd 7: Sowjetunion mit annektierten Gebieten I. Besetzte sowjetische Gebiete unter deutscher Militärverwaltung, Baltikum und Transnistrien. Bearb. von Bert Hoppe und Hildrun Glass, München: Oldenbourg 2011, 891 S., EUR 59,80 [ISBN 978-3-486-58911-5]

- Jürg Schoch, »Mit Aug’ und Ohr für’s Vaterland!« Der Schweizer Aufklärungsdienst von Heer & Haus im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Zürich: NZZ libro 2015, 347 S., EUR 48,00 [ISBN 978-3-03823-901-7]

- Miriam Gebhardt, Als die Soldaten kamen. Die Vergewaltigung deutscher Frauen am Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs, 3. Aufl., München: DVA 2015, 351 S., EUR 21,99 [ISBN 978-3-421-04633-8]

- Florian Huber, Kind, versprich mir, dass du dich erschießt. Der Untergang der kleinen Leute 1945, Berlin: Berlin Verlag 2015, 303 S., EUR 22,99 [ISBN 978-3-8270-1247-0]

- Ian Buruma, ’45: Die Welt am Wendepunkt. Aus dem Engl. von Barbara Schaden, München: Hanser 2015, 412 S., EUR 26,00 [ISBN 978-3-446-24734-5]

- Buchbesprechungen: Nach 1945

- 1945 – Niederlage. Befreiung. Neuanfang. Zwölf Länder Europas nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Hrsg. vom Deutschen Historischen Museum, Darmstadt: Theiss 2015, 248 S., EUR 24,95 [ISBN 978-3-8062-3061-1] 1945 – Ikonen eines Jahres. 108 Photographien von 42 Photographen. Mit einem Einführungstext von Norbert Frei. Hrsg. von Lothar Schirmer, München: Schirmer/Mosel 2015, 216 S., EUR 29,80 [ISBN 978-3-8296-0715-5] 1945 – Niederlage und Neubeginn. Hrsg. von Ernst Piper, Köln: Lingen 2015, 272 S., EUR 24,95 [ISBN 978-3-945136-20-1]

- Norman Ächtler, Generation in Kesseln. Das Soldatische Opfernarrativ im westdeutschen Kriegsroman 1945–1960, Göttingen: Wallstein 2013, 456 S., EUR 29,90 [ISBN 978-3-8535-1277-7]

- Barbara Schmitter Heisler, From German Prisoner of War to American Citizen. A Social History with 35 Interviews, Jefferson, NC, London: McFarland 2013, VII, 203 S., $ 39.95 [ISBN 978-0-7864-7311-3]

- Stephan Geier, Schwellenmacht. Bonns heimliche Atomdiplomatie von Adenauer bis Schmidt, Paderborn [u. a.]: Schöningh 2013, 485 S., EUR 49,90 [ISBN 978-3-506-77791-1]

- Manfred Kanetzki, MiGs über Peenemünde: Die Geschichte der NVA-Fliegertruppenteile auf Usedom, 2. Aufl., Berlin: MediaScript 2014, 212 S., EUR 24,50 [ISBN 978-3-981-48221-8]

- Kristan Stoddart, The Sword and the Shield. Britain, America, NATO, and Nuclear Weapons, 1970–1976, Basingstoke [u. a.]: Palgrave Macmillan 2014, XX, 324 S., £ 60.00 [ISBN 978-0-230-30093-4]

- William Durie, The United States Garrison Berlin 1945–1994 »Mission Accomplished«, book 1, Berlin: photo-durie.com 2014, VI, 186 S., $ 26.50 [ISBN 978-1-63068-540-9]

- Maritime Sicherheit. Hrsg. von Sebastian Bruns, Kerstin Petretto und David Petrovic, Wiesbaden: Springer VS 2013, VI, 251 S. (= Globale Gesellschaft und internationale Beziehungen, EUR 39,99 [ISBN 978-3-531-18479-1]

- Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Artikel

- »Si vis societatem para ad militiam.«

- Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern im Ersten Weltkrieg

- Ein »anderer« Oberbefehlshaber?

- Carnage in the Land of Three Rivers: The Syrmian Front 1944–1945

- Nachrichten aus der Forschung

- »Kiel und die Marine 1865–2015. 150 Jahre gemeinsame Geschichte.«

- »Besatzungskinder und Wehrmachtskinder – Auf der Suche nach Identität und Resilienz.«

- »Globaler Krieg. Visionen und ihre Umsetzung.«

- »Nachkrieg und Medizin in Deutschland im 20. Jahrhundert.«

- »Gewaltkulturen von den Kolonialkriegen bis zur Gegenwart.«

- »Der Krieg ist vorbei. Heimkehr – Trauma – Weiterleben.«

- »Geschichtsbewusstsein als soldatische Kernkompetenz. 60 Jahre Historische Bildung in der Bundeswehr.«

- Buchbesprechungen: Allgemeines

- Ulrich March, Grundzüge der Militärgeschichte. Krieg und politische Kultur, Aachen: Helios 2014, 141 S., EUR 16,50 [ISBN 978-3-86933-112-6]

- Die Dienstbibliothek des Brandenburg-Preußischen Hausarchivs. Katalog, bearb. von Herzeleide Henning, Berlin: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz 2015, XII, 806 S. (= Veröffentlichungen aus den Archiven Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Arbeitsberichte, 17), EUR 27,00 [ISBN 978-3-923579-24-2]

- Stadt und Krieg. Leipzig in militärischen Konflikten vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. Hrsg. von Ulrich von Hehl, Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverl. 2014, 531 S. (= Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte der Stadt Leipzig, 8), EUR 62,00 [ISBN 978-3-86583-902-2]

- Urte Evert, Die Eisenbraut. Symbolgeschichte der militärischen Waffe von 1700 bis 1945, Münster, New York: Waxmann 2015, 376 S. (= Beiträge zur Volkskultur in Nordwestdeutschland, 125), EUR 44,90 [ISBN 978-3-8309-3217-8]

- Marco Sigg, Der Unterführer als Feldherr im Taschenformat. Theorie und Praxis der Auftragstaktik im deutschen Heer 1869 bis 1945, Paderborn [u. a.]: Schöningh 2014, IX, 504 S. (= Zeitalter der Weltkriege, 12), EUR 46,90 [ISBN 978-3-506-78086-7]

- Stefan Troebst, Erinnerungskultur – Kulturgeschichte – Geschichtsregion. Ostmitteleuropa in Europa, Stuttgart: Steiner 2013, 440 S. (= Forschungen zur Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Mitteleuropa, 43), EUR 64,00 [ISBN 973-3-515-10384-8]

- Arnold Suppan, Hitler – Beneš – Tito. Konflikt, Krieg und Völkermord in Ostmittel- und Südosteuropa, 3 Bde, Wien: ÖAW 2014, XIV, 2048 S. (= Internationale Geschichte, 1), EUR 148,00 [ISBN 978-3-7001-7309-0]

- Gerd Krumeich, Deutschland, Frankreich und der Krieg. Historische Studien zu Politik, Militär und Kultur. Hrsg. von Susanne Brandt, Thomas Gerhards und Uta Hinz, Essen: Klartext 2015, VI, 484 S., EUR 24,95 [ISBN 978-3-8375-1040-9]

- Mythes et tabous des relations franco-allemandes au XXe siècle./Mythen und Tabus der deutsch-französischen Beziehungen im 20. Jahrhundert. Éd. par/hrsg. von Ulrich Pfeil, Bern [u. a.]: Lang 2012, X, 312 S. (= Convergences, 65), EUR 69,10 [ISBN 978-3-0343-0592-1]

- Buchbesprechungen: Altertum und Mittelalter

- Martin Hofbauer, Vom Krieger zum Ritter. Die Professionalisierung der bewaffneten Kämpfer im Mittelalter, Freiburg i.Br.: Rombach 2015, VI, 226 S. (= Einzelschriften zur Militärgeschichte, 48), EUR 24,80 [ISBN 978-3-7930-9770-9]

- The Medieval Way of War. Studies in Medieval Military History in Honor of Bernard S. Bachrach. Ed. by Gregory I. Halfond, Farnham [u. a.]: Ashgate 2015, XVI, 332 S., £ 75.00 [ISBN 978-1-4724-1958-3]

- Peter Blickle, Der Bauernjörg. Feldherr im Bauernkrieg. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg 1488–1531, München: Beck 2015, 586 S., EUR 34,95 [ISBN 978-3-406-67501-0]

- Buchbesprechungen: Frühe Neuzeit;

- Frieden übersetzen in der Vormoderne. Translationsleistungen in Diplomatie, Medien und Wissenschaft. Hrsg. von Heinz Duchhardt und Martin Espenhorst, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2012, 286 S. (= Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz. Beihefte, 92), EUR 54,99 [ISBN 978-3-525-10114-8]

- Axel Gotthard, Der liebe vnd werthe Fried. Kriegskonzepte und Neutralitätsvorstellungen in der Frühen Neuzeit, Köln [u. a.]: Böhlau 2013, 964 S. (= Forschungen zur kirchlichen Rechtsgeschichte und zum Kirchenrecht, 32), EUR 128,00 [ISBN 978-3-412-22142-3]

- Militär und Mehrsprachigkeit im neuzeitlichen Europa. Hrsg. von Helmut Glück und Mark Häberlein, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2014, 256 S. (= Fremdsprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 14), EUR 58,00 [ISBN 978-3-447-10299-5]

- Steffen Leins, Das Prager Münzkonsortium 1622/23. Ein Kapitalgeschäft im Dreißigjährigen Krieg am Rande der Katastrophe, Münster: Aschendorff 2012, 208 S., EUR 29,00 [ISBN 978-3-402-12951-7]

- Konrad Kramar und Georg Mayrhofer: Prinz Eugen. Heros und Neurose, St. Pölten [u. a.]: Residenz 2013, 253 S., EUR 21,90 [ISBN 978-3-7017-3289-0] Elisabeth Großegger: Mythos Prinz Eugen. Inszenierung und Gedächtnis, Wien [u. a.]: Böhlau 2014, 406 S., EUR 39,00 [ISBN 978-3-205-79501-8]

- Militär und Gesellschaft in Preußen. Quellen zur Militärsozialisation 1713–1806. Archivalien in Berlin, Dessau und Leipzig. Teil 1, Bd 1: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz (1. Hälfte), XXX, 533 S.; Teil 1, Bd 2: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz (2. Hälfte), V, 861 S.; Teil 2: Weitere Archive, Bibliotheken und Museen in Berlin, Dessau und Leipzig, V, 185 S.; Teil 3: Indices und Systematiken, IX, 412 S. Hrsg. von Jürgen Kloosterhuis [u. a.]; bearb. von Peter Bahl, Claudia Nowak und Ralf Pröve, Berlin: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz 2015 (= Veröffentlichungen aus den Archiven Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Arbeitsberichte 15, 1–4), EUR 85,00 [ISBN 978-3-923579-22-8]

- Buchbesprechungen: 1789–1870

- Napoleon on War. Ed. by Bruno Colson. Transl. by Gregory Elliott, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2015, VIII, 484 S., £ 27.99 [ISBN 978-0-19-968556-1]

- Revisiting Napoleon’s Continental System. Local, Regional and European Experiences. Ed. by Katherine B. Aaslestad and Johan Joor, Basingstoke [u. a.]: Palgrave Macmillan 2015, XIX, 290 S. (= War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850), £ 68.00 [ISBN 978-1-137-34556-1]

- Klaus-Jürgen Bremm, Die Schlacht. Waterloo 1815, Darmstadt: Theiss 2015, 256 S., EUR 24,95 [ISBN 978-3-8062-3041-3]

- Adam Zamoyski, 1815. Napoleons Sturz und der Wiener Kongress. Aus dem Engl. von Ruth Keen und Erhard Stölting, München: Beck 2014, 704 S., EUR 29,95 [ISBN 978-3-406-67123-4]

- Reinhard Stauber, Der Wiener Kongress, Wien [u. a.]: Böhlau 2014, 285 S., EUR 19,99 [ISBN 978-3-8252-4095-0]

- Brian E. Vick, The Congress of Vienna. Power and Politics after Napoleon, Cambridge, MA, London: Harvard University Press 2014, VIII, 436 S., $ 45,00 [ISBN 978-0-674-72971-1]

- Karl-Heinz Reger, »Dann sprang er über Bord«. Alltagspsychologie und psychische Erkrankung an Bord britischer Schiffe im 19. Jahrhundert, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2014, 525 S., EUR 59,99 [ISBN 978-3-525-30066-4]

- Buchbesprechungen: 1871–1918

- Max Lehmann, Bismarck. Eine Charakteristik. Hrsg. von Gertrud Lehmann. Mit Beitr. zur Neuausgabe von Gerd Fesser und Helmut Donat sowie mit einer Zeittafel und Bibliografie, Bremem: Donat 2015, 352 S. (= Schriftenreihe Geschichte & Frieden, 31), EUR 16,80 [ISBN 978-3-943425-47-5]

- Ernst Dietrich Baron von Mirbach, Prinz Heinrich von Preußen. Eine Biographie des Kaiserbruders, Köln [u. a.]: Böhlau 2013, 645 S., EUR 39,90 [ISBN 978-3-412-21081-6]

- Jürgen Angelow, Der Weg in die Urkatastrophe. Der Zerfall des alten Europa 1900–1914, Berlin: be.bra 2010, 208 S. (= Deutsche Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert, 2), EUR 19,90 [ISBN 978-3-89809-402-3]

- Jörg-Michael Hormann und Eberhard Kliem, Die Kaiserliche Marine im Ersten Weltkrieg. Von Wilhelmshaven nach Scapa Flow, München: Bucher 2014, 161 S., EUR 29,99 [ISBN 978-3-7658-2031-1]

- Jürgen Gottschlich, Beihilfe zum Völkermord. Deutschlands Rolle bei der Vernichtung der Armenier, Berlin: Links 2015, 343 S., EUR 19,90 [ISBN 978-3-86153-817-2]

- Sergej Nelipovič, Krovavyj oktjabr’ 1914 goda [Der blutige Oktober des Jahres 1914], Moskau: Minuvshee 2013, 803 S., RUB 600,00 [ISBN 978-5-902073-95-6]

- Pis’ma s vojny 1914–1917 [Briefe aus dem Krieg 1914–1917]. Hrsg. von A.B. Astašov und P.A. Simmons, Moskau: Novyj chronograf 2015, 795 S. (= Ot pervogo lica. Istorija Rossii v vospominanijach, dnevnikach, pis’mach [Aus erster Hand. Die Geschichte Russlands in Erinnerungen, Tagebüchern, Briefen]) [ISBN 978-5-94881-272-4]