Abstract

Three new ethyltin complexes containing ferrocenecarboxylate, Et2Sn(OC(O)Fc)2 (1), [(Et2SnOC(O)Fc)2O]2 (2), and [EtSn(O)OC(O)Fc]6 (3) (Fc = C5H5FeC5H4), have been synthesized by the reaction of diethyltin dichloride with ferrocenecarboxylic acid in the presence of potassium hydroxide and characterized by means of elemental analysis, FT-IR, NMR spectroscopy, and X-ray single crystal diffraction. In solid state, 1 is a weak dimer possessing a cyclic Sn2O2 unit formed by the intermolecular Sn⋯O interaction, and the tin atom has a distorted pentagonal bipyramid geometry. Compound 2 is a four-tin nuclear diethyltin complex with a ladder framework, and each tin atom adopts a distorted trigonal bipyramidal configuration in which two oxygen atoms occupy the axial positions. Compound 3 is a hexa-tin nuclear monoethyltin complex having a drum-shaped structure, and each of the tin atoms possesses a distorted octahedral geometry. The ferrocene units are attached to the tin atoms through the monodentate or bidentate coordinated carboxylates.

1 Introduction

Organotins are a kind of widely used main group metal compound, which have more applications than the organic derivatives of any other metal (Davies et al., 2008). They have been used as stabilizers for polyvinyl chloride, ionophores in sensors, insecticides, fungicides, organic synthesis reagents, reaction catalysts, and so on (Davies et al., 2008). Recent studies have shown that organotin carboxylates exhibit high cytotoxic activity and good prospects in cancer therapy (Bantia et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2011). Ferrocene is an organic transition metal compound, and its derivatives have been used as catalysts for asymmetric reactions and functional materials including photosensitizer, nonlinear optical material, membrane electrode, and smoke agent, and exhibited a variety of biological properties (Braga and Silva, 2013; Cunningham et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020). To synthesize organotin carboxylates containing ferrocenyl group is a valuable choice for broadening the use of ferrocene derivatives and searching for highly efficient and low toxic organotin anticancer drugs. Some organotin carboxylates containing ferrocenyl were synthesized in succession and also showed good in vitro anticancer activity. Some examples are as follows: R3SnOC(O)Fc (R = Me, n-Bu, Ph, Cy), R2Sn(OC(O)Fc)2 (R = Me, n-Bu, Ph), [(n-Bu2SnOC(O)Fc)2O]2, and [RSn(O)OC(O)Fc]6 (R = n-Bu, PhCH2) (Chandrasekhar et al., 2000, 2005a; Chandrasekhar and Thirumoorthi, 2008; Dong et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2011). Up to now, the reaction of diethyltin dichloride with ferrocenecarboxylic acid (FcCOOH) has not been reported in the literature. In order to continue to expand the chemistry of the ferrocene–organotin compounds, we synthesized three ethyltin ferrocenecarboxylates, Et2Sn(OC(O)Fc)2 (1), [(Et2SnOC(O)Fc)2O]2 (2), and [EtSn(O)OC(O)Fc]6 (3), and determined their crystal structures (Scheme 1).

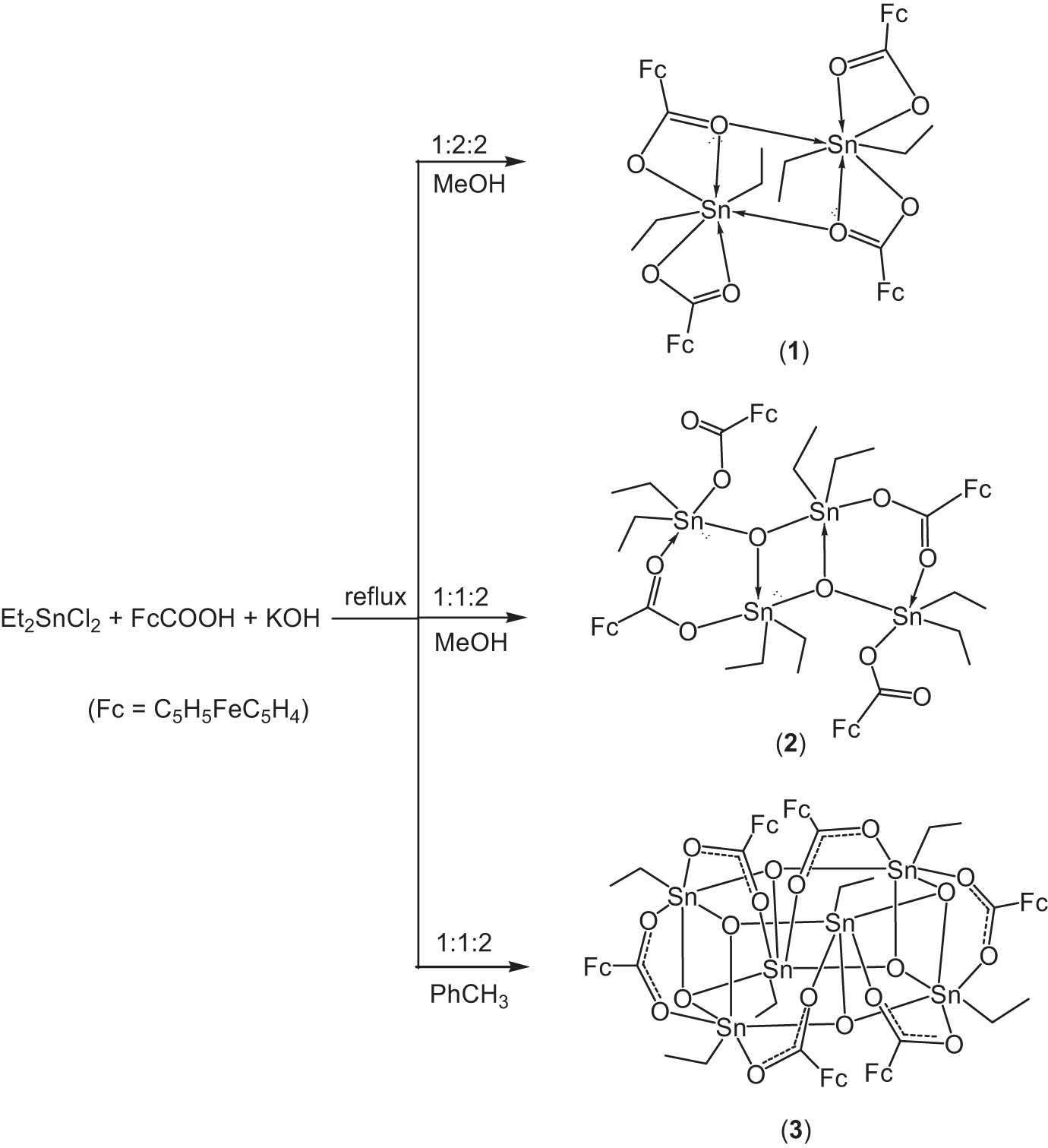

Synthesis of compounds 1–3.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Synthesis

In the presence of potassium hydroxide, diethyltin dichloride reacted with ferrocenecarboxylic acid (FcCOOH) to produce compounds 1–3 (Scheme 1). The nature of the product is related to the stoichiometry of the reaction as well as the reaction temperature (solvent reflux temperature). Under reflux conditions, diethyltin bis(ferrocenecarboxylate) (1) and bis[oxo-bis(diethyltin ferrocenecarboxylate)] (2) were formed in good yields (isolated yield >80%) in a methanolic solution, and hexakis(oxo-ethyltin ferrocenecarboxylate) (3) was isolated in a low yield (31%) in toluene. Compound 3 was formed by a Sn–C bond cleavage of diethyltin in the reaction process. A wide range of Sn–C bonds are cleaved by carboxylic acids leading to Sn–O bond formation (Chandrasekhar et al., 2005b). Although the Sn–C bond cleavage is a common reaction in phenyl-, benzyl-, allyl-, and methyl-tin compounds, very few examples of Sn–ethyl and Sn–butyl bonds cleavage are known. The cleavage of the alkyl-tin bond may involve an SE2 mechanism (Chandrasekhar et al., 2005b; Davies, 2004; Gopal et al., 2014; Shankar et al., 2010). Compounds 1–3 are orange red crystals and stable in air. 1 and 2 are soluble in benzene, methanol, chloroform, and acetone, while 3 is not (Chandrasekhar and Thirumoorthi, 2008; Mairychova et al., 2014).

2.2 Spectroscopic analysis

Ferrocenecarboxylic acid displays a broad band at 3,200–2,500 cm−1 and a strong band at 1,658 cm−1, which are assigned to the ν(OH) and ν as(COO) stretching vibrations, respectively. In 1–3, the absorption band at 3,200–2,500 cm−1 disappears, and the ν s(COO) and ν as(COO) bands shift considerably, indicating the formation of the ethyltin complexes by the carboxyl (COO) oxygen atom coordination to tin (Shang et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2011). The difference between the ν as(COO) and ν s(COO) of carboxylate moiety, Δν(COO), has been used to determine its bidentate or monodentate coordination mode (Chen et al., 2020; Deacon and Phillips, 1980; Shang et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2020). In 1–3, FcCOO is bidentate, which is evidenced by the small ∆ν(COO) value (179 cm−1 for 1, 160 cm−1 for 2, 192 cm−1 for 3). In 2, there is also a carboxyl group of monodentate coordination to tin because of a large ∆ν(COO) value of 285 cm−1 (Tian et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2010), which is in agreement with the below X-ray structure of 2.

The 1H NMR spectra of 1–3 exhibit the expected integration and multiplicities of the resonance absorption peaks. The chemical shifts of the protons of Cp-rings (C5H5 and C5H4) appear at ∼4.20, 4.40, and 4.80 ppm, respectively. The 13C chemical shift of carboxyl carbon in 1 and 2 is 182.1 and 177.6 ppm, respectively, and the resonance absorptions of carbon atoms of Cp-rings appear in the region of 69–75 ppm. In 2, the (CH3CH2)2Sn moiety displays two sets of 1H and 13C NMR signals (see Section 4), which is consistent with the NMR spectra of the other diorganooxotin carboxylates [(R2SnOOCR′)2O]2, such as [(n-Bu2SnOOCFc)2O]2 (Tao and Xiao, 1996) and [(Et2SnOOCC6H3N2S)2O]2 (Wang et al., 2010). The 119Sn chemical shifts primarily depend on the coordination number and the type of the donor atoms bonded to tin atom (Davies, 2004; Holecek et al., 1986). Compound 1 displays a single 119Sn resonance at −149.5 ppm, suggesting that the tin atom in 1 is five-coordinated in the CDCl3 solution (Holecek et al., 1986). In solution, there may be the following situations: one of the two carboxyl groups of the ligands is monodentate coordination, and the other is bidentate chelation coordination (Chandrasekhar and Thirumoorthi, 2007). In compound 2, a pair of 119Sn resonances is observed at −189.0 and −199.2 ppm due to the presence of endo- and exo-cyclic tin atoms. These values are comparable with those reported in other dimeric distannoxanes (Chandrasekhar et al., 2005a; Wang et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2011) and correspond to a five-coordinated or weakly six-coordinated tin atom (Holecek et al., 1986). Due to the poor solubility of 3, the 13C and 119Sn NMR cannot be obtained for identification.

2.3 Structure analysis

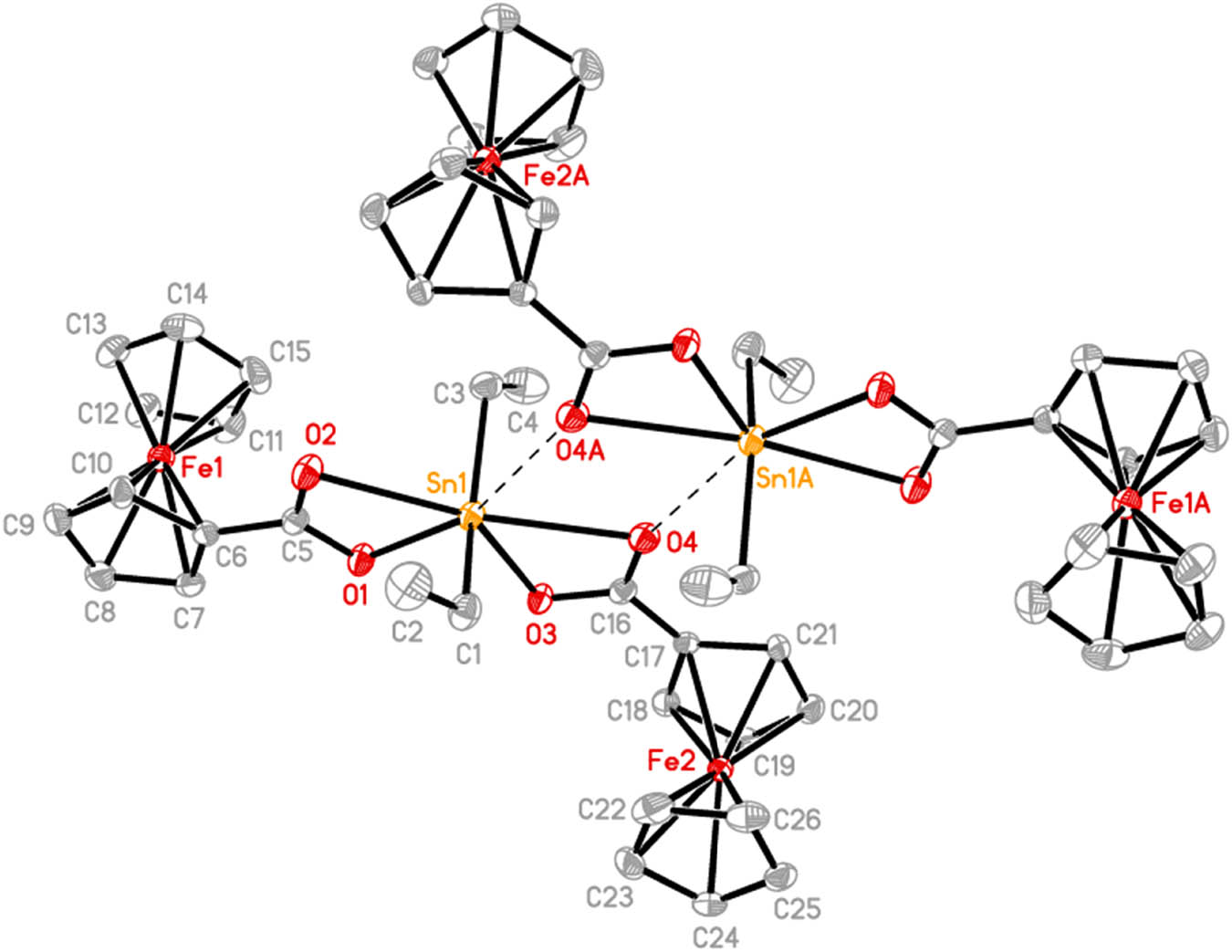

The molecular structures of 1–3 are presented in Figures 1–3, respectively. The selected bond lengths and bond angles are shown in Table 1. The structure of compound 1 is similar to that of the reported diorganotin dicarboxylates, such as n-Bu2Sn(OOCFc)2 (Chandrasekhar et al., 2005a), Me2Sn(OOCFc)2 (Chandrasekhar and Thirumoorthi, 2008), and Et2Sn(OOCCH2C6H4Cl-4)2 (Muhammad et al., 2014), and the central tin atom is also six-coordinated and adopts a skew-trapezoidal geometry. Two ferrocenecarboxylate ligands are chelated to a tin atom with anisobidentate coordination mode, which leads to two different Sn–O bonds (short Sn(1)–O(1) (2.114(3) Å) and Sn(1)–O(3) (2.115(2) Å), and long Sn(1)–O(2) (2.499(3) Å) and Sn(1)–O(4) (2.550(3) Å)). The O(2)–Sn(1)–O(4) (168.33(9)°) and C(1)–Sn(1)–C(3) (152.03(17)°) angles are larger than those found in its analogues n-Bu2Sn(OOCFc)2 (166.93(2)° and 145.0(3)°) (Chandrasekhar et al., 2005a) and Me2Sn(OOCFc)2 (165.6(1)° and 146.9(4)°) (Chandrasekhar and Thirumoorthi, 2008) due to the intermolecular Sn(1)⋯O(4)#1 (2.851(3) Å) interaction (symmetry code #1: 1/2 − x, 1/2 − y, 1 − z) between Sn(1) atom and the carbonyl O(4) atom of the neighboring ligand. This Sn⋯O separation (2.851(3) Å) is much shorter than the sum of the van der Waals radii of the two atoms (3.73 Å), but longer than the O→Sn coordination bond (∼2.50 Å) (Hu et al., 2003). If the intermolecular contact was considered, the coordination geometry of tin atom can be described as a distorted pentagonal bipyramid, and a centrosymmetric dimer with a four-membered Sn2O2 ring complex 1 was formed (Figure 1).

The molecular structure of 1. Ellipsoids are drawn at the 30% probability level. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Symmetry code A: 1/2 − x, 1/2 − y, 1 − z.

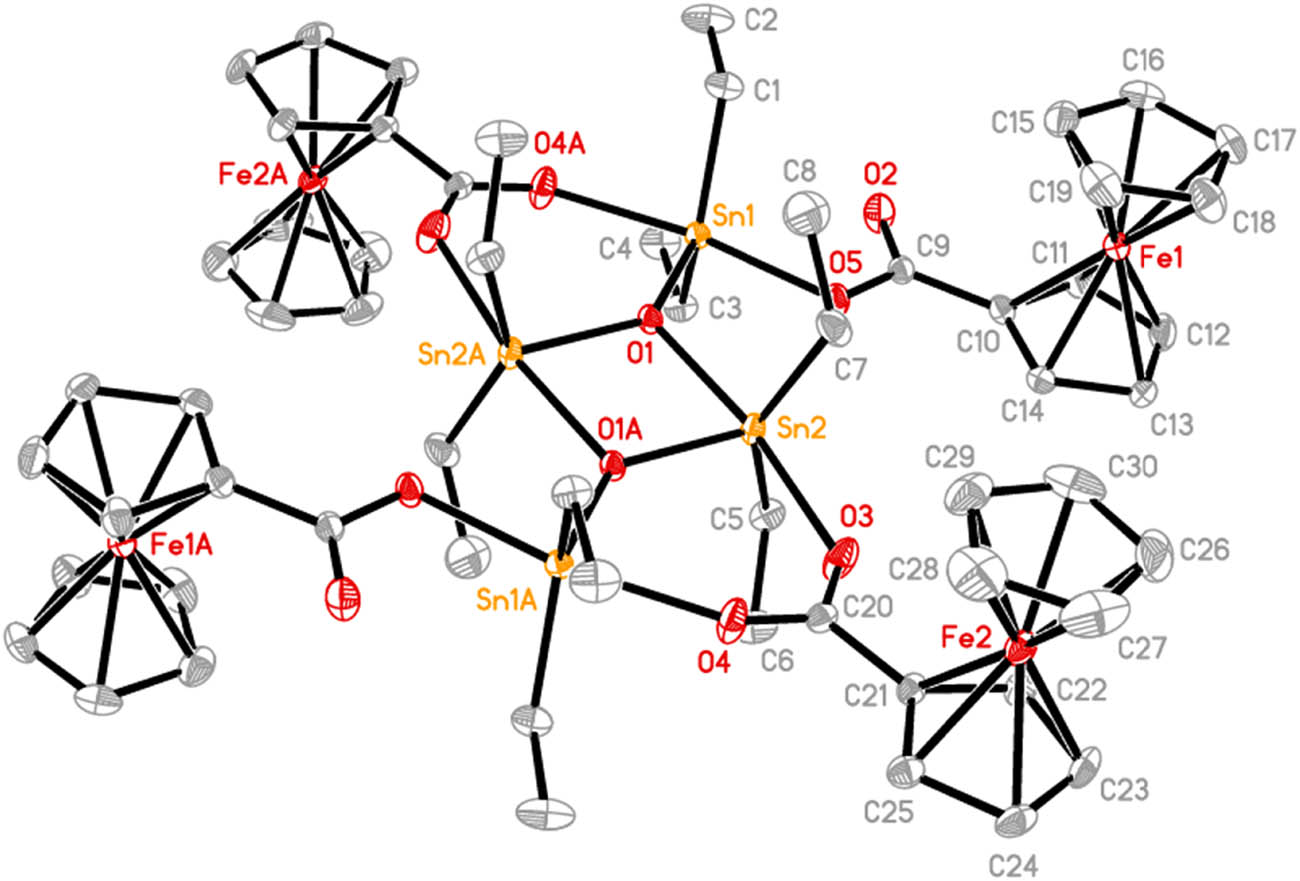

The molecular structure of 2. Ellipsoids are drawn at the 30% probability level. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Symmetry code A: 2 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z.

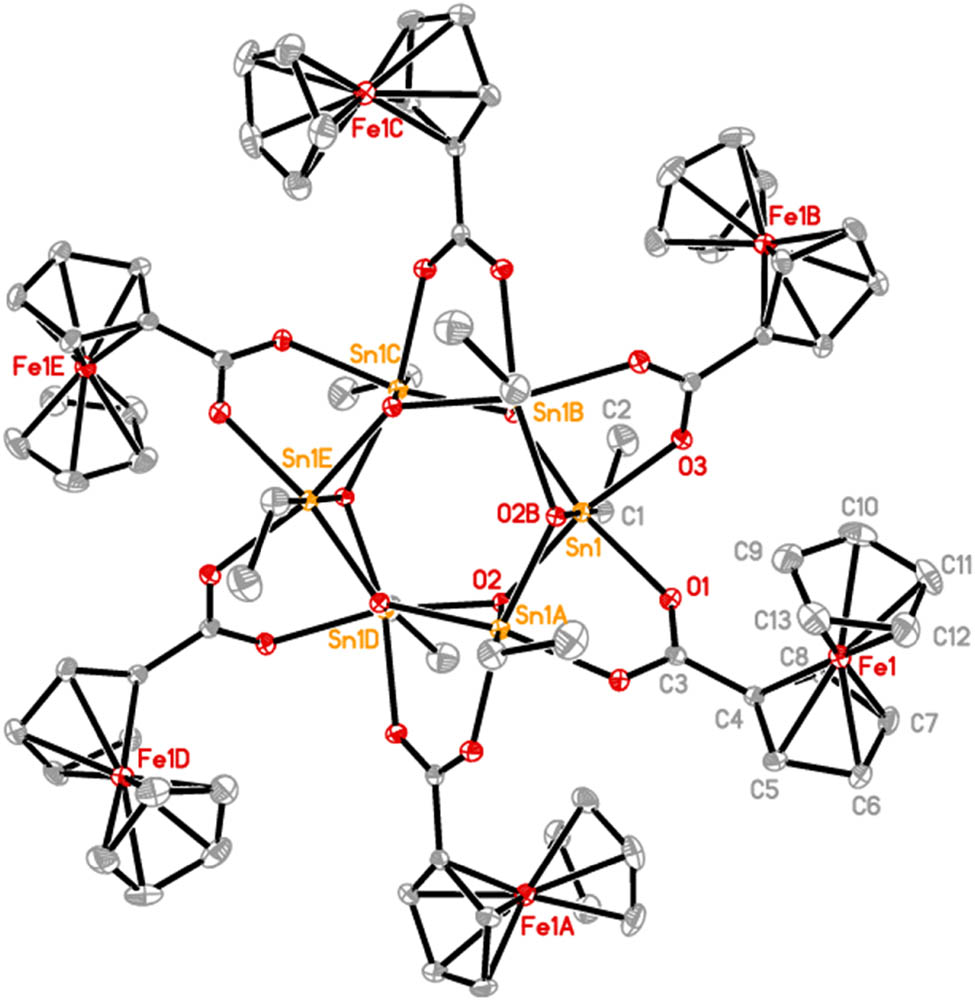

The molecular structure of 3. Ellipsoids are drawn at the 20% probability level. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Symmetry code A: −y, x − y, z; B: x − y, x, 2 − z.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 1–3

| 1 | |||

| Sn(1)–O(1) | 2.114(3) | Sn(1)–C(3) | 2.102(4) |

| Sn(1)–O(2) | 2.499(3) | C(5)–O(1) | 1.288(4) |

| Sn(1)–O(3) | 2.115(2) | C(5)–O(2) | 1.232(5) |

| Sn(1)–O(4) | 2.550(3) | C(16)–O(3) | 1.281(4) |

| Sn(1)–O(4)#1 | 2.851(3) | C(16)–O(4) | 1.240(4) |

| Sn(1)–C(1) | 2.114(4) | C(3)–Sn(1)–O(1) | 99.22(14) |

| C(3)–Sn(1)–C(1) | 152.03(17) | C(1)–Sn(1)–O(2) | 88.43(13) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–C(1) | 100.77(15) | O(3)–Sn(1)–O(2) | 137.14(9) |

| C(3)–Sn(1)–O(3) | 104.24(14) | C(3)–Sn(1)–O(4) | 90.18(14) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–O(3) | 81.39(10) | O(1)–Sn(1)–O(4) | 135.84(9) |

| C(1)–Sn(1)–O(3) | 97.96(14) | C(1)–Sn(1)–O(4) | 88.99(13) |

| C(3)–Sn(1)–O(2) | 86.78(14) | O(3)–Sn(1)–O(4) | 54.53(9) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–O(2) | 55.83(9) | O(2)–Sn(1)–O(4) | 168.33(9) |

| 2 | |||

| Sn(1)–O(1) | 2.020(2) | Sn(2)–O(1) | 2.157(3) |

| Sn(1)–O(5) | 2.164(3) | Sn(2)–O(3) | 2.238(3) |

| Sn(1)–O(4)#2 | 2.243(3) | Sn(2)–O(1)#2 | 2.033(2) |

| Sn(1)–C(1) | 2.115(4) | Sn(2)–C(5) | 2.107(4) |

| Sn(1)–C(3) | 2.115(4) | Sn(2)–C(7) | 2.125(5) |

| C(9)–O(2) | 1.219(5) | C(20)–O(3) | 1.243(5) |

| C(9)–O(5) | 1.292(5) | C(20)–O(4) | 1.247(5) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–C(3) | 112.30(14) | C(5)–Sn(2)–C(7) | 145.0(2) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–C(1) | 111.67(15) | C(5)–Sn(2)–O(1) | 95.98(15) |

| C(3)–Sn(1)–C(1) | 134.68(17) | C(7)–Sn(2)–O(1) | 98.51(15) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–O(5) | 79.86(10) | C(5)–Sn(2)–O(3) | 86.65(16) |

| C(3)–Sn(1)–O(5) | 98.85(15) | C(7)–Sn(2)–O(3) | 84.41(16) |

| C(1)–Sn(1)–O(5) | 99.01(16) | O(1)–Sn(2)–O(3) | 170.23(10) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–O(4)#2 | 89.05(11) | O(1)#2–Sn(2)–O(3) | 93.83(11) |

| C(3)–Sn(1)–O(4)#2 | 84.69(16) | O(1)#2–Sn(2)–O(1) | 76.40(10) |

| C(1)–Sn(1)–O(4)#2 | 85.62(17) | O(1)#2–Sn(2)–C(5) | 107.92(15) |

| O(5)–Sn(1)–O(4)#2 | 168.89(11) | O(1)#2–Sn(2)–C(7) | 106.42(17) |

| 3 | |||

| Sn(1)–C(1) | 2.122(7) | Sn(1)–O(2)#4 | 2.094(4) |

| Sn(1)–O(1) | 2.144(4) | Sn(1)–O(3) | 2.164(4) |

| Sn(1)–O(2) | 2.087(3) | C(3)–O(1) | 1.271(7) |

| Sn(1)–O(2)#3 | 2.079(3) | C(3)–O(3) | 1.261(7) |

| O(2)–Sn(1)–O(2)#3 | 103.78(19) | O(1)–Sn(1)–O(2)#4 | 88.71(16) |

| O(2)–Sn(1)–O(2)#4 | 77.60(16) | C(1)–Sn(1)–O(1) | 92.5(2) |

| O(2)#3–Sn(1)–O(2)#4 | 77.78(16) | O(2)#4–Sn(1)–O(3) | 86.33(15) |

| C(1)–Sn(1)–O(2) | 99.5(2) | O(2)–Sn(1)–O(3) | 160.17(16) |

| C(1)–Sn(1)–O(2)#3 | 101.7(2) | O(2)#4–Sn(1)–O(3) | 88.18(15) |

| C(1)–Sn(1)–O(2)#4 | 176.8(2) | C(1)–Sn(1)–O(3) | 94.9(2) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–O(2)#3 | 160.53(16) | O(1)–Sn(1)–O(3) | 79.22(16) |

| O(1)–Sn(1)–O(2) | 86.62(15) |

Symmetry code: #11/2 − x, 1/2 − y, 1 − z; #2 2 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z; #3 −y, x − y, z; #4 x − y, x, 2 − z.

Complex 2 exists as a centrosymmetric dimer (Figure 2) and possesses a ladder framework built up around the planar cyclic Sn2O2 unit (Sn(2)O(1)Sn(2)#2O(1)#2, #2: 2 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z) in which Sn(2)–O(1) and Sn(2)–O(1)#2 distances are 2.157(3) and 2.033(2) Å, respectively. On both sides of the central Sn2O2 ring, there are two six-membered rings formed by the bridging bidentate coordination of ferrocenecarboxylate (O(3)C(20)O(4)) to the endo- and exo-cyclic tin atoms (Sn(2) and Sn(1)). The Sn(2)–O(3) and Sn(1)#2–O(4) bond lengths are 2.238(3) and 2.243(3) Å, respectively. The other ferrocenecarboxylate (O(2)C(9)O(5)) acts as a monodentate ligand to coordinate to exocyclic Sn(1) atom with a Sn(1)–O(5) distance of 2.164(3) Å. Each of the tin atoms is five-coordinated and has a distorted trigonal bipyramidal configuration in which two oxygen atoms occupy the axial positions. The axial O(5)–Sn(1)–O(4)#2 and O(1)–Sn(2)–O(3) angles are 168.89(11)° and 170.23(10)°, respectively. Distortions from the ideal geometry are partly due to the intramolecular Sn⋯O interactions (Sn(1)⋯O(2) 2.785(3) Å and Sn(2)⋯O(5) 2.752(3) Å), which make the C(1)–Sn(1)–C(3) and C(5)–Sn(1)–C(7) angles on the equatorial plane expand to 134.68(17)° and (145.0(2))°, respectively, from the ideal value of 120°. The structural features of 2 are consistent with Type I among the structures of [(R2SnOOCR′)2O]2 summarized by Tiekink (1991). In the molecular structure of 2, the central Sn2O2 ring, carboxylates, and substituted cyclopentadiene rings are essentially in the same plane, and the maximum deviation (O(3)) from the mean plane is 0.248(3) Å. The ferrocenyls are located in the upper and lower sides of this plane, respectively.

Compound 3 crystallizes in a trigonal space group R3̄ and is a hexa-tin nuclear organotin complex possessing the drum-shaped structure. Although many of such drum compounds have been reported (Basu Baul et al., 2017; Chandrasekhar et al., 2007; Shang et al., 2011; Tiekink, 1991; Xiao et al., 2019), to our knowledge, 3 is the first example of structural determined hexameric ethyloxotin carboxylate [EtSn(O)OC(O)R]6. In the central stannoxane Sn6O6 core, two six-membered Sn3O3 drum faces display a chair-like conformation with the two different Sn–O bonds (Sn(1)–O(2) 2.087(3) Å and Sn(1)–O(2)#3 2.079(3) Å (#3: −y, x − y, z)), and six four-membered Sn2O2 rings in the sides of the drum present butterfly-like conformation with the three different Sn(1)–O(2), Sn(1)–O(2)#3, and Sn(1)–O(2)#4 (#4: x − y, x, 2 − z) (2.094(4) Å) bonds. Each O(2) atom as a tridentate ligand links three tin centers, and ferrocenecarboxylate bridges two tin centers by anisobidentate coordination mode with the Sn–O distances of 2.144(4) and 2.164(4) Å. Each tin atom is six-coordinated and adopts a distorted octahedral geometry. The three bond angles in the trans position of octahedron are C(1)–Sn(1)–O(2)#4 176.8(2)°, O(1)–Sn(1)–O(2)#3 160.53(16)°, and O(2)–Sn(1)–O(3) 160.17(16)°, respectively. These structural parameters in 3 are similar to those of [RSn(O)OCOFc]6 (R = n-Bu, PhCH2) reported by Chandrasekhar and coauthors (Chandrasekhar et al., 2000; Chandrasekhar and Thirumoorthi, 2008), indicating that R bound to tin has little effect on the drum structure.

3 Conclusions

Under different conditions, diethyltin dichloride reacts with ferrocenecarboxylic acid to produce compounds 1–3. In solid state, 1, 2, and 3 are weak dimers possessing a cyclic Sn2O2 unit, a four-tin nuclear diethyltin complex with a ladder framework, and a hexa-tin nuclear monoethyltin complex having a drum-shaped structure, respectively. The ferrocenyl moieties are appended to the tin atoms by the monodentate or bidentate coordinated carboxylate ligands.

Experimental

All chemical reagents and solvents were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagents Company (Shanghai, China) and used directly without further purification. The instruments used for the characterization of compounds are as follows: a Perkin Elmer 2400 Series II elemental analyzer (carbon and hydrogen analyses), a Nicolet 470 FT-IR spectrophotometer (IR spectra), and a Bruker Avance III HD500 NMR spectrometer (1H and 13C NMR spectra).

Synthesis of diethyltin bis(ferrocenecarboxylate) (1)

Ferrocenecarboxylic acid (0.460 g, 2 mmol), potassium hydroxide (0.112 g, 2 mmol), and methanol (25 mL) were added into a 50 mL round bottom flask and stirred for 10 min. Diethyltin dichloride (0.248 g, 1 mmol) was added, and then the reaction mixture was refluxed for 4 h. The orange red solution was cooled to room temperature and filtered. The solvent was removed from the filtrate by a rotary evaporator. The orange yellow solid obtained was recrystallized from the mixed solvents of n-hexane and trichloromethane (2:1, volume ratio). Yield 0.52 g (82%), m.p. 164.5–165.3°C. Anal. found: C, 49.08; H, 4.32. Calcd for C26H28Fe2O4Sn: C, 49.19; H, 4.45%. Selected IR (KBr) cm−1: 1,564 [ν as(COO)], 1,545, 1,470, 1,385 [ν s(COO)], 1,335, 1,181. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ): 4.89 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H, 2CH), 4.44 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H, 2CH), 4.25 (s, 5H, C5H5), 1.74 (q, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.44 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3, δ): 182.11 (COO), 71.61, 71.03, 70.70 (C5H4), 69.89 (C5H5), 17.86 (CH2), 9.18 (CH3). 119Sn NMR (CDCl3, δ): −149.5.

Synthesis of bis[oxo-bis(diethyltin ferrocenecarboxylate)] (2)

The preparation process of compound 2 is the same as that of compound 1. Ferrocenecarboxylic acid (0.230 g, 1 mmol), potassium hydroxide (0.112 g, 2 mmol), and diethyltin dichloride (0.248 g, 1 mmol) were used. The crude product was recrystallized from cyclohexane–benzene (2:1, volume ratio), and 0.36 g orange crystal was obtained in 87% yield. M.p. 183.0–184.0°C. Anal. found: C, 43.59; H, 4.58. Calcd for C60H76Fe4O10Sn4: C, 43.53; H, 4.63%. Selected IR (KBr) cm−1: 1,606 [ν as(COO)], 1,550 [ν as(COO)], 1,476, 1,390 [ν s(COO)], 1,321 [ν s(COO)], 1,172. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ): 4.76 (s, 2H, 2CH), 4.40 (s, 2H, 2CH), 4.25 (s, 5H, C5H5), 1.68 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.58 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.49 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.44 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3, δ): 177.60 (COO), 75.05, 70.73, 70.58 (C5H4), 69.54 (C5H5), 22.28, 20.86 (CH2), 10.27, 9.98 (CH3). 119Sn NMR (CDCl3, δ): −189.0, −199.2.

Synthesis of hexakis(oxo-ethyltin ferrocenecarboxylate) (3)

Ferrocenecarboxylic acid (0.230 g, 1 mmol), potassium hydroxide (0.112 g, 2 mmol), and diethyltin dichloride (0.248 g, 1 mmol) were mixed and ground in an agate mortar, then transferred to a 50 mL round bottom flask. After 20 mL of toluene was added, the mixture was refluxed under stirring for 3 h. The brown solution was filtered when hot, and the filtrate was left to slow evaporation at room temperature. Orange crystals were formed from the solution after 3 days. Yield 0.12 g (31%), m.p. >200°C. Anal. found: C, 39.66; H, 3.48. Calcd for C78H84Fe6O18Sn6: C, 39.75; H, 3.59%. Selected IR (KBr) cm−1: 1,574 [ν as(COO)], 1,542, 1,469, 1,382 [ν s(COO)], 1,329, 1,177. 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, δ): 4.71 (s, 2H, 2CH), 4.43 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H, 2CH), 4.25 (s, 5H, C5H5), 1.43 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.23 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3).

X-ray crystallography

The orange-red single crystals of 1 and 2 were obtained from cyclohexane–benzene (1:1, v/v), and compound 3 was obtained by slow evaporation of toluene solution, respectively. Diffraction data were collected at room temperature on a Bruker Smart Apex imaging-plate area detector fitted with graphite monochromatized Mo-Kα radiation (0.71073 Å). Structure solution and refinement were completed using SHELXS-97 (Sheldrick, 2008) and SHELXL-2018 (Sheldrick, 2015), respectively. The non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, and hydrogen atoms were placed at calculated positions. In 2, the ethyl group was disordered over two positions, and the site occupancy was refined to 0.736(16):0.264(16). Crystal data and refinement parameters are summarized in Table 2. Crystallographic data have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre with supplementary publication numbers CCDC 2094054–2094056.

Crystallographic and refinement data of 1–3

| Compound | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C26H28Fe2O4Sn | C60H76Fe4O10Sn4 | C78H84Fe6O18Sn6 |

| Formula weight | 634.87 | 1,655.36 | 2,356.69 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Triclinic | Trigonal |

| Space group | C2/c | P1̄ | R3̄ |

| a (Å) | 25.808(4) | 10.4492(14) | 24.3910(18) |

| b (Å) | 10.3801(17) | 11.5889(15) | 24.3910(18) |

| c (Å) | 20.476(3) | 13.7870(18) | 11.8608(18) |

| α (°) | 90 | 100.453(2) | 90 |

| β (°) | 117.389(2) | 102.373(1) | 90 |

| γ (°) | 90 | 103.892(2) | 120 |

| Volume (Å3) | 4,870.6(14) | 1,534.6(3) | 6,110.9(13) |

| Z | 8 | 1 | 3 |

| D c (g·cm−3) | 1.732 | 1.791 | 1.921 |

| μ (mm−1) | 2.223 | 2.572 | 2.903 |

| F(000) | 2,544 | 820 | 3,456 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.42 × 0.36 × 0.24 | 0.16 × 0.12 × 0.10 | 0.16 × 0.10 × 0.06 |

| θ range (°) | 1.8–26.0 | 1.6–26.0 | 2.0 to 25.5 |

| Tot. reflections | 18,379 | 11,980 | 12,667 |

| Uniq. reflections (R int) | 4,772 (0.047) | 5,940 (0.026) | 2,534 (0.063) |

| Reflections (I >2σ(I)) | 3,805 | 4,988 | 1,893 |

| GOF on F 2 | 1.015 | 1.017 | 1.015 |

| R indices [I >2σ(I)] | R = 0.037, wR = 0.079 | R = 0.035, R = 0.079 | R = 0.046, wR = 0.101 |

| R indices (all data) | R = 0.051, wR = 0.084 | R = 0.044, wR = 0.084 | R = 0.066, wR = 0.109 |

| Δρ min, Δρ max (e·Å−3) | −0.347, 0.704 | −0.487, 0.962 | −0.457, 1.427 |

-

Funding information: Authors state that no funding is involved.

-

Author contributions: Ruili Wang: experimental work, writing – original draft; Jing Zhang: experimental work; Laijin Tian: methodology, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Supplementary material: Supplementary material (ESI) is available for this publication.

-

Data availability statement: Crystallographic data (CCDC 2094054–2094056) of this article can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Bantia C.N., Hadjikakou S.K., Sismanoglu T., Hadjiliadis N., Anti-proliferative and antitumor activity of organotin(iv) compounds. An overview of the last decade and future perspectives. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2019, 194, 114–152.10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2019.02.003Search in Google Scholar

Basu Baul T.S., Dutta D., Duthie A., Silva M.G.D., Perceptive variation of carboxylate ligand and probing the influence of substitution pattern on the structure of mono- and di-butylstannoxane complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta, 2017, 455, 627–637.10.1016/j.ica.2016.05.008Search in Google Scholar

Braga S.S., Silva A.M.S., A new age for iron: antitumoral ferrocenes. Organometallics, 2013, 32, 5626–5639.10.1021/om400446ySearch in Google Scholar

Chandrasekhar V., Nagendran S., Bansal S., Kozee M.A., Powell D.R., An iron wheel on a tin drum: a novel assembly of a hexaferrocene unit on a tin-oxygen cluster. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed., 2000, 39, 1833–1835##2000.10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000515)39:10<1833::AID-ANIE1833>3.0.CO;2-3Search in Google Scholar

Chandrasekhar V., Gopal K., Nagendran S., Singh P., Steiner A., Zacchini S., et al., Organostannoxane-supported multiferrocenyl assemblies: synthesis, novel supramolecular structures, and electrochemistry. Chem. Eur. J., 2005a, 11, 5437–5448.10.1002/chem.200500316Search in Google Scholar

Chandrasekhar V., Gopal K., Sasikumar P., Thirumoorthi R., Organooxotin assemblies from Sn-C bond cleavage reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev., 2005b, 249, 1745–1765.10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.028Search in Google Scholar

Chandrasekhar V., Gopal K., Thilagar P., Nanodimensional organostannoxane molecular assemblies. Acc. Chem. Res., 2007, 40, 420–434.10.1021/ar600061fSearch in Google Scholar

Chandrasekhar V., Thirumoorthi R., 1,1′-Ferrocenedicarboxylate-bridged redox-active organotin and -tellurium-containing 16-membered macrocycles: synthesis, structure, and electrochemistry. Organometallics, 2007, 26, 5415–5422.10.1021/om700622rSearch in Google Scholar

Chandrasekhar V., Thirumoorthi R., Facile, ambient temperature, double Sn-C bond cleavage: synthesis, structure, and electrochemistry of organotin and organotellurium ferrocenecarboxylates. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem., 2008, 4578–4585.10.1002/ejic.200800574Search in Google Scholar

Chen L., Wang Z., Qiu T., Sun R., Zhao Z., Tian L., et al., Synthesis, structural characterization, and properties of triorganotin complexes of Schiff base derived from 3-aminobenzoic acid and salicylaldehyde or 2,4-pentanedione. Appl. Organomet. Chem., 2020, 34, e5790.10.1002/aoc.5790Search in Google Scholar

Cunningham L., Benson A., Guiry P.J., Recent developments in the synthesis and applications of chiral ferrocene ligands and organocatalysts in asymmetric catalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem., 2020, 18, 9329–9370.10.1039/D0OB01933JSearch in Google Scholar

Davies A.G. Organotin chemistry, 2nd ed. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004.10.1002/3527601899Search in Google Scholar

Davies A.G., Gielen M., Pannell K.H., Tiekink E.R.T. Tin chemistry: fundamentals, frontiers, and applications. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, U.K, 2008.10.1002/9780470758090Search in Google Scholar

Deacon G.B., Phillips R.J., Relationships between the carbon-oxygen stretching frequencies of carboxylato complexes and the type of carboxylate coordination. Coord. Chem. Rev., 1980, 33, 227–250.10.1016/S0010-8545(00)80455-5Search in Google Scholar

Dong Y., Yu Y., Tian L., Synthesis, structural characterization and anti-bacterial activity of triorganotin ferrocenecarboxylates. Main. Group. Met. Chem., 2014, 37, 91–95.10.1515/mgmc-2014-0027Search in Google Scholar

Gopal K., Kundu S., Metre R.K., Chandrasekhar V., Ambient temperature Sn-C bond cleavage reaction involving the Sn-n-butyl group. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 2014, 640, 1147–1151.10.1002/zaac.201300620Search in Google Scholar

Holecek J., Nadvornik M., Handlir K., 13C and 119Sn NMR spectra of dibutyltin(IV) compounds. J. Organomet. Chem., 1986, 315, 299–308.10.1016/0022-328X(86)80450-8Search in Google Scholar

Hu S., Zhou C., Cai Q., Average Van der Waals radii of atoms in crystals. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin., 2003, 19, 1073–1077.10.3866/PKU.WHXB20031118Search in Google Scholar

Mairychova B., Stepnicka P., Ruzicka A., Dostal L., Jambor R., Reactivity studies on an intramolecularly coordinated organotin(iv) carbonate. Organometallics, 2014, 33, 3021–3029.10.1021/om5002759Search in Google Scholar

Muhammad N., Rehman Z., Shujah S., Ali S., Shah A., Meetsma A., Synthesis and structural characterization of monomeric and polymeric supramolecular organotin 4-chlorophenylethanoates. J. Coord. Chem., 2014, 67, 1110–1120.10.1080/00958972.2014.898755Search in Google Scholar

Shang X., Meng X., Alegria E.C.B.A., Li Q., Silva M.F.C.G., Kuznetsov M.L., et al., Syntheses, molecular structures, electrochemical behavior, theoretical study, and antitumor activities of organotin complexes containing 1-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-cyclopentanecarboxylato ligands. Inorg. Chem., 2011, 50, 8158–8167.10.1021/ic200635gSearch in Google Scholar

Sheldrick G.M., A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., 2008, A64, 112–122.10.1107/S0108767307043930Search in Google Scholar

Sheldrick G.M., Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., 2015, C71, 3–8.10.1107/S2053229614024218Search in Google Scholar

Shankar R., Jain A., Kociok-Kohn G., Mahon M.F., Molloy K.C., Cleavage of Sn-C and S-C bonds on an organotin scaffold: synthesis and characterization of a novel organotin-sulfite cluster bearing methyltin- and dimethyltin fragments. Inorg. Chem., 2010, 49, 4708–4715.10.1021/ic100465uSearch in Google Scholar

Tao J., Xiao W., Structural chemistry of organotin ferrocenecarboxylic esters: synthesis and spectroscopic studies on dialkyltin esters of ferrocenecarboxylic acid FcCOOH and 1,1′-ferrocenedicarboxylic acid Fc(COOH)2. J. Organomet. Chem., 1996, 526, 21–24.10.1016/S0022-328X(96)06453-4Search in Google Scholar

Tian L., Wang R., Zhang J., Zhong F., Qiu Y., Synthesis and structural characterization of dialkyltin complexes of N-salicylidene-L-valine. Main. Group. Met. Chem., 2020, 43, 138–146.10.1515/mgmc-2020-0017Search in Google Scholar

Tiekink E.R.T., Structural chemistry of organotin carboxylates: a review of the crystallographic literature. Appl. Organometal Chem., 1991, 5, 1–23.10.1002/aoc.590050102Search in Google Scholar

Wang Z., Guo Y., Zhang J., Ma L., Song H., Fan Z., Synthesis and biological activity of organotin 4-methyl-1,2,3-thiadiazole-5-carboxylates and benzo[1,2,3]thiadiazolecarboxylates. J. Agric. Food Chem., 2010, 58, 2715–2719.10.1021/jf902168dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

Xiao J., Sun Z., Kong F., Gao F., Current scenario of ferrocene-containing hybrids for antimalarial activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem., 2020, 185, 111791.10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111791Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Xiao X., Li C., Lai H., He Y., Jiang T., Shi N., et al., Drumlike p-methylphenyltin carboxylates: the synthesis, characterization, antitumor activities and fluorescence. J. Mol. Struct., 2019, 1190, 116–124.10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.04.047Search in Google Scholar

Zhu C., Yang L., Li D., Zhang Q., Dou J., Wang D., Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure and antitumor activity of organotin compounds bearing ferrocenecarboxylic acid. Inorg. Chim. Acta, 2011, 375, 150–157.10.1016/j.ica.2011.04.049Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Ruili Wang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Embedded three spinel ferrite nanoparticles in PES-based nano filtration membranes with enhanced separation properties

- Research Articles

- Syntheses and crystal structures of ethyltin complexes with ferrocenecarboxylic acid

- Ultra-fast and effective ultrasonic synthesis of potassium borate: Santite

- Synthesis and structural characterization of new ladder-like organostannoxanes derived from carboxylic acid derivatives: [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2, [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2, and [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2

- HPA-ZSM-5 nanocomposite as high-performance catalyst for the synthesis of indenopyrazolones

- Conjugation of tetracycline and penicillin with Sb(v) and Ag(i) against breast cancer cells

- Simple preparation and investigation of magnetic nanocomposites: Electrodeposition of polymeric aniline-barium ferrite and aniline-strontium ferrite thin films

- Effect of substrate temperature on structural, optical, and photoelectrochemical properties of Tl2S thin films fabricated using AACVD technique

- Core–shell structured magnetic MCM-41-type mesoporous silica-supported Cu/Fe: A novel recyclable nanocatalyst for Ullmann-type homocoupling reactions

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel lead coordination polymer: [Pb(L)(1,3-bdc)]·2H2O

- Comparative toxic effect of bulk zinc oxide (ZnO) and ZnO nanoparticles on human red blood cells

- In silico ADMET, molecular docking study, and nano Sb2O3-catalyzed microwave-mediated synthesis of new α-aminophosphonates as potential anti-diabetic agents

- Synthesis, structure, and cytotoxicity of some triorganotin(iv) complexes of 3-aminobenzoic acid-based Schiff bases

- Rapid Communications

- Synthesis and crystal structure of one new cadmium coordination polymer constructed by phenanthroline derivate and 1,4-naphthalenedicarboxylic acid

- A new cadmium(ii) coordination polymer with 1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylate acid and phenanthroline derivate: Synthesis and crystal structure

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel lead dinuclear complex: [Pb(L)(I)(sba)0.5]2

- Special Issue: Theoretical and computational aspects of graph-theoretic methods in modern-day chemistry (Guest Editors: Muhammad Imran and Muhammad Javaid)

- Computation of edge- and vertex-degree-based topological indices for tetrahedral sheets of clay minerals

- Structures devised by the generalizations of two graph operations and their topological descriptors

- On topological indices of zinc-based metal organic frameworks

- On computation of the reduced reverse degree and neighbourhood degree sum-based topological indices for metal-organic frameworks

- An estimation of HOMO–LUMO gap for a class of molecular graphs

- On k-regular edge connectivity of chemical graphs

- On arithmetic–geometric eigenvalues of graphs

- Mostar index of graphs associated to groups

- On topological polynomials and indices for metal-organic and cuboctahedral bimetallic networks

- Finite vertex-based resolvability of supramolecular chain in dialkyltin

- Expressions for Mostar and weighted Mostar invariants in a chemical structure

Articles in the same Issue

- Embedded three spinel ferrite nanoparticles in PES-based nano filtration membranes with enhanced separation properties

- Research Articles

- Syntheses and crystal structures of ethyltin complexes with ferrocenecarboxylic acid

- Ultra-fast and effective ultrasonic synthesis of potassium borate: Santite

- Synthesis and structural characterization of new ladder-like organostannoxanes derived from carboxylic acid derivatives: [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2, [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2, and [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2

- HPA-ZSM-5 nanocomposite as high-performance catalyst for the synthesis of indenopyrazolones

- Conjugation of tetracycline and penicillin with Sb(v) and Ag(i) against breast cancer cells

- Simple preparation and investigation of magnetic nanocomposites: Electrodeposition of polymeric aniline-barium ferrite and aniline-strontium ferrite thin films

- Effect of substrate temperature on structural, optical, and photoelectrochemical properties of Tl2S thin films fabricated using AACVD technique

- Core–shell structured magnetic MCM-41-type mesoporous silica-supported Cu/Fe: A novel recyclable nanocatalyst for Ullmann-type homocoupling reactions

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel lead coordination polymer: [Pb(L)(1,3-bdc)]·2H2O

- Comparative toxic effect of bulk zinc oxide (ZnO) and ZnO nanoparticles on human red blood cells

- In silico ADMET, molecular docking study, and nano Sb2O3-catalyzed microwave-mediated synthesis of new α-aminophosphonates as potential anti-diabetic agents

- Synthesis, structure, and cytotoxicity of some triorganotin(iv) complexes of 3-aminobenzoic acid-based Schiff bases

- Rapid Communications

- Synthesis and crystal structure of one new cadmium coordination polymer constructed by phenanthroline derivate and 1,4-naphthalenedicarboxylic acid

- A new cadmium(ii) coordination polymer with 1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylate acid and phenanthroline derivate: Synthesis and crystal structure

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel lead dinuclear complex: [Pb(L)(I)(sba)0.5]2

- Special Issue: Theoretical and computational aspects of graph-theoretic methods in modern-day chemistry (Guest Editors: Muhammad Imran and Muhammad Javaid)

- Computation of edge- and vertex-degree-based topological indices for tetrahedral sheets of clay minerals

- Structures devised by the generalizations of two graph operations and their topological descriptors

- On topological indices of zinc-based metal organic frameworks

- On computation of the reduced reverse degree and neighbourhood degree sum-based topological indices for metal-organic frameworks

- An estimation of HOMO–LUMO gap for a class of molecular graphs

- On k-regular edge connectivity of chemical graphs

- On arithmetic–geometric eigenvalues of graphs

- Mostar index of graphs associated to groups

- On topological polynomials and indices for metal-organic and cuboctahedral bimetallic networks

- Finite vertex-based resolvability of supramolecular chain in dialkyltin

- Expressions for Mostar and weighted Mostar invariants in a chemical structure