Synthesis and structural characterization of new ladder-like organostannoxanes derived from carboxylic acid derivatives: [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2, [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2, and [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2

-

Tidiane Diop

, Mouhamadou Birame Diop

Abstract

Three types of ladder-like organostannoxanes, [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2 (1), [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2 (2), and [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2 (3), have been synthesized and characterized using elemental analyses, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance (1H, 13C) experiments, and, for 1 and 2, single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. X-Ray diffraction discloses that complexes adopt tetranuclear tin(iv) ladder-like structures containing two (1) or four (2) deprotonated ligands. The essential difference between their molecular structures is that in 2 there are four carboxylate ligands, while in 1 and 3 there are two. The crystal structure of 1 reveals them to be a tetranuclear structure containing a three-rung-staircase Sn4O4 core. The Sn4O4 cluster consists of a ladder of four Sn2O2 units. For 2, the structure is a tetranuclear centrosymmetric dimer of an oxoditin unit having a central four-member ring. In this complex, the central Sn2O2 core is fused with two four-member and two six-member rings. In the structures, there are two types of tin ions arranged in distorted trigonal bipyramid geometry or octahedron geometry. A series of O–H⋯N, C–H⋯O, and C–H⋯π intermolecular hydrogen bonds in these complexes play an important function in the supramolecular, or two-dimensional network structures are formed by these interactions.

1 Introduction

During the past few decades, research on the synthesis and characterization of coordination polymers has intrigued scientists not only for their fascinating structures but also for their potential applications (Gielen et al., 2005; Kemmer et al., 2000; Willem et al., 1997). It has become apparent that coordination polymers may be prepared by the appropriate selection of metal and multifunctional ligands (Chandrasekhar et al., 2002, 2005; Diop et al., 2021). Among these materials, organotin(iv) carboxylate complexes have been actively investigated by a large number of researchers due to their significant reduction in tumor growth rates (Vieira et al., 2010), interesting topologies, and various structural types including monomers, dimers, tetramers, oligomeric ladders, and hexameric drums (Arjmand et al., 2014; Banti et al., 2019). The organostannoxanes have received special attentions, particularly in view of their immense structural diversity. Several products, such as ladders (Wen et al., 2018; García-Zarracino et al., 2009), cubes (Cavka et al., 2008), hexameric (Baul et al., 2017), and polymeric drums (Ma et al., 2003), have been isolated. Ladder-shaped tetranuclear organotin compounds (Wang et al., 2013) have also been isolated. Tetranuclear crystal structures [(n-Bu2Sn)4(O)2(OH)2(O3SC6H4-NH2-4)2] (Wen et al., 2018), [(Me2Sn)4(O)2(OH)2(O3SC6H4-NH2-4)2] (Wen et al., 2018), and [(n-Bu2Sn)4(μ 3-O)2(μ 2-OCH3)2(O2CC6H4-SO2NH2-4)2 (Wang et al., 2019) with the ladder as structural motif were previously described in the literature. Many butylstannoxanes were prepared using carboxylate ligands (Baul et al., 2017; Shankar and Dubey, 2020; Valcarcel et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2019). These molecular structures of compounds display hexameric Sn6O6 clusters with drum-like or tetrameric structures revealing Sn4O2 cores with ladder-type structural motifs. In our previous work, we reported a series of butylstannoxanes carboxylate complexes using carboxylic acid ligands such as pyridine-4-carboxylic acid, diphenylacetic acid, and 4-aminocarboxylic acid. The synthesis and structural characterization of three new organostannoxanes are reported as follows: [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2(μ 2 -OH)2 (1), [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2 (2), and [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2(μ 2 -OH)2 (3).

2 Results

2.1 Crystallographic data and experimental details

Crystal data, data collection, and structure refinement details for the complex are summarized in Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement of 1 and 2

| 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Formula | C44H82N2O8Sn4 | C88H116O10Sn4 |

| Moiety | C44H82N2O8Sn4 | C88H116O10Sn4 |

| T (K) | 175 | 175 |

| Spacegroup | P21 /n | P-1 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Triclinic |

| a (Å) | 13.0597(5) | 15.6908(7) |

| b (Å) | 12.2041(6) | 15.7536(8) |

| c (Å) | 17.0979(6) | 19.4517(8) |

| α (°) | 90 | 83.718(4) |

| β (°) | 96.017(4) | 75.218(4) |

| γ (°) | 90 | 64.601(5) |

| V (Å3) | 2710.09(19) | 4199.7(4) |

| Z | 2 | 2 |

| P (g cm−3) | 1.522 | 1.430 |

| M r (g mol−1) | 1241.96 | 1808.65 |

| µ (mm−1) | 1.867 | 1.231 |

| R int | 0.065 | 0.084 |

| θ max (°) | 29.091 | 29.464 |

| Resolution (Å) | 0.79 | 0.82 |

| N tot (measured) | 18,164 | 52,524 |

| N ref (unique) | 6,381 | 19,770 |

| N ref (I > 2σ (I)) | 4,462 | 10,858 |

| N ref (least-squares) | 4,462 | 10,858 |

| N par | 285 | 928 |

| <σ(I)/I> | 0.0807 | 0.1165 |

| R 1 (I > 2σ(I)) | 0.0901 | 0.0689 |

| wR2 (I>2σ(I)) | 0.0390 | 0.0887 |

| R 1 (all) | 0.1325 | 0.1292 |

| wR2 (all) | 0.0488 | 0.01682 |

| GOF | 1.4261 | 1.1410 |

| Δρ (e Å−3) | −1.56/3.26 | −1.70/3.72 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.12 × 0.15 × 0.20 | 0.22 × 0.25 × 0.30 |

3 Discussion

3.1 Reactions

The general chemical reactions in methanol are shown for complexes 1 and 3 Eq. (1) and for complex 2 Eq. (2):

After synthesis, the complexes are characterized by elemental analyses, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance (1H, 13C) experiments, and, for 1 and 2, single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

3.2 Spectroscopic studies

3.2.1 FT-IR spectra

The explicit feature in the FTIR spectra is the absence of a broadband in the region 3,400–2,800 cm−1, which appears in the free ligands for the COOH group, indicating the removal of COOH protons and the formation of Sn–O bonds through this site (Li et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012). The strong absorption appearing at 444 (1), 436 (2), and 433 (3) cm−1 is assigned to ν(Sn–O) (Xiao et al., 2013). The intense absorption maximum in the 623–630 cm−1 region is assigned to an Sn–O–Sn stretching vibration (Li et al., 2015). In the infrared spectra of this complex, the Δν(C(O)O) [ν(C(O)O)asym – ν(C(O)O)sym] values are 299 cm−1 for 1 and 273 cm−1 for 3, larger than 200 cm−1, which stands for the monodentate coordination mode of the carboxylate groups (Hanif et al., 2010), and this behavior is also consistent with the X-ray structure. The two Δν magnitudes (ν asymCOO – ν symCOO) 254 and 143 cm−1 for (2) show that two distinct coordination modes for carboxylate ligands are present in the structure (Eng et al., 2007). One carboxylate fragment is symmetrically bridged between two Sn ions, and another carboxylate acts as a bis-monodentate ligand for Sn atoms (Scheme 2). The presence of a νsSnBu2 band at 617 cm−1 (1), 615 cm−1 (2), and 613 cm−1 (3) indicates a nonlinear SnBu2 residue (Nakamoto, 1997; Beckman et al., 2004) (Schemes 1 and 2). The conclusions drawn from the IR data are very much consistent with those of the X-ray crystallography studies.

![Scheme 1

Structures of [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ

3

-O)2(μ

2

-OH)2 (1) or [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ

3

-O)2(μ

2

-OH)2 (3).](/document/doi/10.1515/mgmc-2022-0008/asset/graphic/j_mgmc-2022-0008_fig_005.jpg)

Structures of [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2(μ 2 -OH)2 (1) or [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2(μ 2 -OH)2 (3).

![Scheme 2

Structure of [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ

3

-O)2 (2).](/document/doi/10.1515/mgmc-2022-0008/asset/graphic/j_mgmc-2022-0008_fig_006.jpg)

Structure of [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2 (2).

3.2.2 NMR spectra

The 1H and 13C NMR data of the complexes are given in the experimental part, and the observed resonances have been assigned based on the chemical shift values. In the 1H NMR spectra, the expected signals in the 10–13 ppm region of the carboxylic acid hydrogens are not present in the complexes, indicating the replacement of the carboxylic acid protons with organotin(iv) moieties (Najafi et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2013). The order of the 1H chemical shifts of the CH n groups in the Sn–butyl substituents was found to be (α, β) > (γ, δ) for the Bu2Sn complexes (SnCH2(α)CH2(β)CH2(γ)CH3(δ)) (Pruchnik et al., 2013). Multiplet signals in the 1.50–1.86, 1.25–1.43, and 0.92–0.93 ppm ranges are attributed to (m, α-CH2, β-CH2), (m, γ-CH2), and (t, δ-CH3), respectively. The multiplet signals at 8.12–6.77 ppm are assigned to aromatic protons. In the 13C NMR spectra of all the complexes, peaks at 167.41 (1), 175.1 (2), and 179.34 (3) ppm attributed to COO− groups show a downfield shift of all the carbon resonances compared to the free carboxylates. These conclusions are consistent with those of the IR data and the X-ray crystal structures.

The structures for complexes 1, 2, and 3 are Sn4O4 tetramers with either monodentate or bridging carboxylate ligands (Schemes 1 and 2).

3.3 Crystal structure of complex 1

A perspective view of the molecular structure of complex 1 is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) are listed in Table 2. The structure consists of the hydroxide-bridged tetrameric organostannoxane ladder and two deprotonated pyridine-4-carboxylic ligands. The complex adopts tetranuclear tin(iv) ladder-like structure containing two deprotonated ligands linked by three alternate Sn2O2 four-membered rings. As is shown in 1, the molecular structure is a centrosymmetric ladder-like structure consisting of the Sn4(μ 3-O)2(μ 2-OH)2 group and two deprotonated ligands. As is the case for other usual tetrameric organostannoxanes (Li et al., 2015), the structure is based on a centrosymmetric Sn2O2 unit connected to a pair of exocyclic Sn atoms via bridging µ 3-O atoms. Triply bridged μ 3 -O atoms, which share their electrons with three tin(iv) centers, have distorted tetrahedral configurations. All the Sn atoms are five-coordinated, showing a trigonal bipyramid configuration in two different chemical environments: SnBu2O2(OH) and SnBu2O(OH)[C5H4N(p-CO2)]. For Sn(1) atom (exocyclic), the basal plane is defined by C(33), C(27), and O(2), and the axial sites occupied by the O(2i) and O(16) atoms, which form an angle of 147.95 (14)°, deviating from a linear arrangement. The carboxylate moiety COO– of the ligand is bonded as a monodentate mode with Sn(3)–O(18) (2.176 Å) way as depicted in Table 2. These bond lengths are in accordance with those of the reported di-n-butyltin(iv) carboxylates (Xiao et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2011).

![Figure 1

Tetranuclear structure of [C5H4N-(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ

3-O)2(μ

2-OH)2 (1).](/document/doi/10.1515/mgmc-2022-0008/asset/graphic/j_mgmc-2022-0008_fig_001.jpg)

Tetranuclear structure of [C5H4N-(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3-O)2(μ 2-OH)2 (1).

![Figure 2

Crystal structure in an infinite chain of [C5H4N-(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ

3-O)2(μ

2-OH)2 (1) with O–H⋯N intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Only Cipso of the n-butyl groups are shown for clarity.](/document/doi/10.1515/mgmc-2022-0008/asset/graphic/j_mgmc-2022-0008_fig_002.jpg)

Crystal structure in an infinite chain of [C5H4N-(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3-O)2(μ 2-OH)2 (1) with O–H⋯N intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Only Cipso of the n-butyl groups are shown for clarity.

Geometric parameters (Å and °) of complex 1

| Lengths (Å) | Angles (°) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sn1–O2i | 2.128 (3) | O2i–Sn1–O2 | 74.51 (17) | Sn1i–O2–Sn3 | 143.67 (18) |

| Sn1–O2 | 2.062 (4) | O2i–Sn1–Sn3 | 108.55 (10) | Sn1–O2–Sn3 | 110.83 (15) |

| Sn1–O16 | 2.139 (4) | O2i–Sn1–O16 | 147.95 (14) | O2–Sn3–C6 | 112.9 (2) |

| Sn1–C27 | 2.106 (7) | O2–Sn1–O16 | 73.44 (14) | O2–Sn3–C9 | 112.2 (3) |

| Sn1–C33 | 2.139 (7) | O2i–Sn1–C27 | 95.6 (2) | C6–Sn3–C9 | 134.7 (3) |

| O2–Sn3 | 2.005 (4) | O2–Sn1–C27 | 115.2 (3) | O2–Sn3–O16 | 73.80 (15) |

| Sn3–C6 | 2.087 (7) | O16–Sn1–C27 | 98.3 (3) | C6–Sn3–O16 | 91.8 (2) |

| Sn3–C9 | 2.166 (8) | O2i–Sn1–C33 | 99.2 (2) | C9–Sn3–O16 | 96.3 (3) |

| Sn3–O16 | 2.173 (4) | O2–Sn1–C33 | 115.8 (3) | O2–Sn3–O18 | 80.31 (14) |

| Sn3–O18 | 2.176 (4) | O16–Sn1–C33 | 94.2 (3) | C6–Sn3–O18 | 99.1 (2) |

| C27–Sn1–C33 | 129.0 (3) | C9–Sn3–O18 | 92.6 (2) | ||

| Sn1i–O2–Sn1 | 105.49 (17) | O16–Sn3–O18 | 154.09 (16) | ||

Symmetry code: (i) −x, −y, −z + 1.

Intermolecular O–H···N hydrogen bonds, involving the bridging hydroxy group and the N atom of the ligand, connect the discrete units into a two-dimensional (2D) network (Figure 2). For the O–H···N intermolecular interactions and C–H⋯O intramolecular interactions (Figure 3), the H(161)···N(24ii) and H(341)⋯O(18i) distances are 2.06(4) and 2.59 Å, respectively. The O(16)–H(161)···N(24ii) and C(34)–H(341)⋯O(18i) angles are 153(8) and 145° (Table 3). The hydrogen-bond geometry is close to the values reported for [(n-Bu2Sn)2(μ 3 -O)(µ-OH)L]2 (Li et al., 2015). The crystallographic study confirms the spectroscopic conclusions.

![Figure 3

Crystal structure in infinite chain of [C5H4N-(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ

3-O)2(μ

2-OH)2 (1) with intermolecular hydrogen bonds O–H···N (color code: blue) and intramolecular hydrogen bonds C–H⋯O (color code: greenish). Only Cipso of the n-butyl groups are shown for clarity.](/document/doi/10.1515/mgmc-2022-0008/asset/graphic/j_mgmc-2022-0008_fig_003.jpg)

Crystal structure in infinite chain of [C5H4N-(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3-O)2(μ 2-OH)2 (1) with intermolecular hydrogen bonds O–H···N (color code: blue) and intramolecular hydrogen bonds C–H⋯O (color code: greenish). Only Cipso of the n-butyl groups are shown for clarity.

Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å and °) of complex 1

| D–H···A | D–H | H···A | D···A | D–H···A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O16–H161···N24ii | 0.82 (2) | 2.06 (4) | 2.810 (14) | 153 (8) |

| C34–H341···O18i | 0.98 | 2.59 | 3.440 (14) | 145 |

Symmetry codes: (i) −x, −y, −z + 1; (ii) x + 1/2, −y − 1/2, z − 1/2.

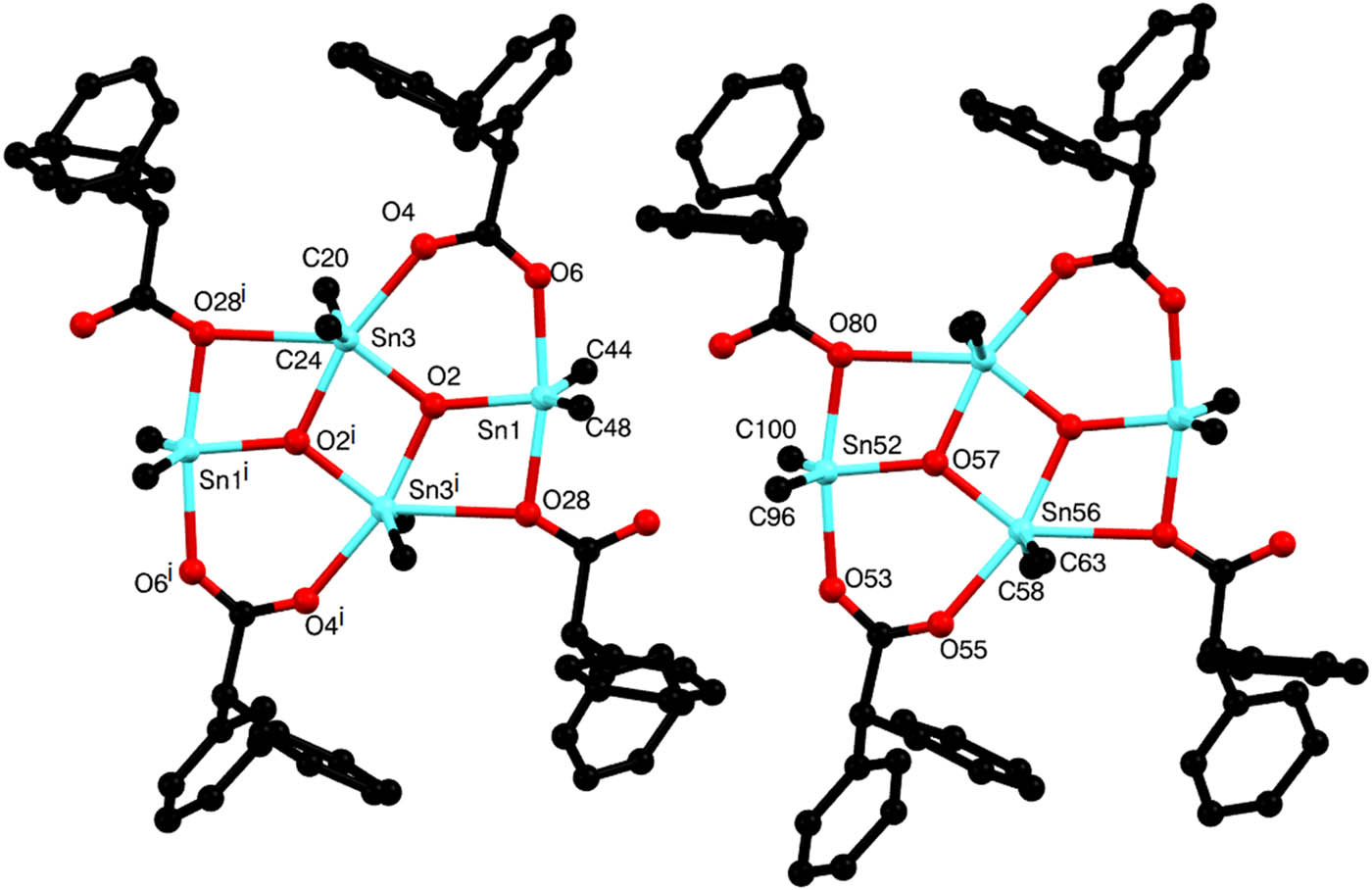

3.4 Crystal structure of complex 2

The asymmetric unit features linkage of neighboring monomers by hydrogen–bond interactions [C–H⋯O and C–H⋯π], giving rise to the formation of organotin(iv) aggregate (Figure 4). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) are listed in Table 4. The conformations of the two independent molecules are almost the same, except for small differences in angles and bond lengths. The crystal structure is very similar to that reported by Zhang et al. (2012). The structure is a tetranuclear centrosymmetric dimer of an oxoditin(iv) unit having a central four-member ring composed of Sn(3)–O(2)–Sn(3i)–O(2i). In this complex, the central Sn2O2 core is fused with two four-member and two six-member rings. The four-member rings, that is, [Sn2O2, i.e., O(28)–Sn(1)–O(2)–Sn(3 i) and O(28i)–Sn(1i)–O(2i)–Sn(3)], are due to the bridging of the monodentate ligand through O atoms, O(28)–Sn(1), and O(28I)–Sn(1i), respectively. Two six-member rings [Sn2O3C; i.e., Sn(1)–O(6)–C(5)–O(4)–Sn(3)–O(2), Sn(1i)–O(6i)–C(5i)–O(4i)–Sn(3i)–O(2i)] also overlap central Sn2O2. As is the case for other usual tetrameric organostannoxane (Li et al., 2015), the structure is based on a centrosymmetric Sn2O2 unit connected to a pair of exocyclic Sn atoms via bridging µ 3-O atoms. There are two distinct carboxylate ligands in the structure. The first carboxylate, defined by the O(4) and O(6) atoms, symmetrically bridges the exocyclic Sn(3) and endocyclic Sn(1) atoms. The second carboxylate is a bis-monodentate coordinating ligand to the exocyclic Sn(3) and endocyclic Sn() via µ-O(28) atom (Figure 4). The endocyclic Sn(3) exists in a distorted octahedron geometry with the four O atoms [O(4), O(6), O(2), and O(28i)] defining the basal plan. The axial position is occupied by C(20) and C(24) which form an angle C(20)–Sn(3)–C(24) of 143.7 (5) (Table 4). The exocyclic Sn(1) atoms are five coordinated and show distorted trigonal bipyramid geometry with the basal plan defined by the µ 3–O(2) atom, the C(48) and C(44) atoms. The axial angle of O(6)–Sn(1)–O(28i) is 169.9°(3).

The ladder structure of aggregate complex 2 (hydrogen atoms bonded to carbon atoms are omitted, and only the α-carbon of the butyl groups has been drawn for clarity).

Geometric parameters (Å and °) of complex 2

| Lengths (Å) | Angles (°) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sn1–O2 | 2.044 (8) | O2–Sn1–O6 | 91.7 (3) | O28i–Sn3–O4 | 127.7 (3) |

| Sn1–O6 | 2.276 (9) | O2–Sn1–O28 | 78.3 (3) | O2i–Sn3–C20 | 100.0 (4) |

| Sn1–O28 | 2.198 (8) | O6–Sn1–O28 | 169.9 (3) | O2–Sn3–C20 | 105.2 (4) |

| Sn1–C44 | 2.143 (12) | O2–Sn1–C44 | 112.0 (4) | O28i–Sn3–C20 | 79.4 (4) |

| Sn1–C48 | 2.128 (13) | O6–Sn1–C44 | 84.4 (4) | O2i–Sn3–C24 | 99.6 (4) |

| O2–Sn3i | 2.143 (7) | O28–Sn1–C44 | 98.2 (4) | O2–Sn3–C24 | 108.8 (4) |

| O2–Sn3 | 2.061 (8) | O2–Sn1–C48 | 108.4 (4) | O28i–Sn3–C24 | 80.8 (4) |

| Sn3–O28i | 2.669 (9) | O6–Sn1–C48 | 89.2 (4) | O4–Sn3–C20 | 85.3 (5) |

| Sn3–O4 | 2.262 (9) | O28–Sn1–C48 | 95.0 (4) | O4–Sn3–C24 | 83.2 (5) |

| Sn3–C20 | 2.137 (13) | C44–Sn1–C48 | 139.2 (5) | C20–Sn3–C24 | 143.7 (5) |

| Sn3–C24 | 2.117 (12) | Sn3i–O2–Sn1 | 119.4 (3) | Sn3–O4–C5 | 138.9 (8) |

| Sn52–O53 | 2.218 (8) | Sn3i–O2–Sn3 | 103.0 (3) | O2–Sn3–O4 | 88.6 (3) |

| Sn52–O57 | 2.047 (8) | Sn1–O2–Sn3 | 137.6 (4) | O2i–Sn3–O4 | 165.5 (3) |

| Sn52–O80 | 2.203 (7) | O2i–Sn3–Sn3i | 37.6 (2) | O2i–Sn3–O28i | 66.7 (3) |

| Sn52–C96 | 2.119 (14) | O2i–Sn3–O2 | 77.0 (3) | ||

| Sn52–C100 | 2.113 (14) | O2–Sn3–O28i | 143.6 (3) | ||

| O55–Sn56, | 2.298 (10) | ||||

| Sn56–O57ii | 2.126 (8) | ||||

Symmetry codes: (i) −x + 1, −y + 1, −z; (ii) −x + 1, −y + 2, −z + 1.

Intermolecular C–H⋯O and C–H⋯π hydrogen bonds are recognized in complex 2, which link the molecular structure into 2D network. For the C–H⋯O interactions, the distances [H⋯O, in the 2.35–2.60 Å ranges] and [H⋯π, in the 2.40–2.60 Å ranges] (Table 5) are all close to the values reported by Li et al. (2015).

Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å and °) of complex 2

| D–H···A | D–H | H···A | D···A | D–H···A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12–H121···C61ii | 0.93 | 2.40 | 3.11 (3) | 134 |

| C19–H191···O4 | 0.93 | 2.47 | 3.09 (3) | 124 |

| C37–H371···O30 | 0.93 | 2.44 | 3.05 (3) | 124 |

| C44–H442···O82iii | 0.97 | 2.60 | 3.37 (3) | 136 |

| C79–H791···O55 | 0.93 | 2.35 | 3.00 (3) | 127 |

| C89–H891···O82 | 0.93 | 2.43 | 3.05 (3) | 124 |

| C96–H962···O30iv | 0.97 | 2.56 | 3.26 (3) | 129 |

| C103–H1031···C62 | 1.05 | 2.60 | 3.54 (3) | 149 |

Symmetry codes: (ii) −x + 1, −y + 2, −z + 1; (iii) x, y − 1, z; (iv) x, y + 1, z.

4 Conclusion

Carboxylate clusters with a Sn4O4 ladder framework and a centrosymmetric Sn2O2 dimer as structural motifs have been successfully synthesized and characterized by elemental analyses, FTIR, NMR spectra, and X-ray single-crystal diffraction. These three ladder-shaped organostannoxane compounds reveal rich supramolecular structures as a result of intermolecular hydrogen bonds. In the crystalline state, the center Sn(iv) atoms of complexes 1 and 2 adopt five-, six-coordination mode, display trigonal bipyramid and octahedron geometry, and reveal rich supramolecular structures by intermolecular hydrogen–bonding interactions. The carboxylates are either bidentate bridging or monodentate.

Experimental

Synthesis of [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3-O)2(μ 2-OH)2 (1)

A methanolic solution containing 0.20 g (0.16 mmol) of pyridine-4-carboxylic acid, C5H4N-(p-CO2H), was added to a methanolic solution which contains 0.1 g (0.32 mmol) of di(n-butyl)dimethoxystannane, n-Bu2Sn(OCH3)2. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for more than 4 h. After the slow evaporation of the solvent, a white crystal was collected and characterized as [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2, yield: 60%; IR (ATR, cm−1): 1,643 ν(OCO)asym, 1,408 ν(OCO)sym, 299 ∆ν, 1,601/1,557 νC═ C/C═N, 709 νaSnC2, 625 νs(Sn–O–Sn), 617 νsSnC2, 444 νSn–O. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): SnCH2CH2CH2CH3, δ = 1.78–1.60 (m, CH2–CH2); 1.43–1.25 (m, CH2); 0.93 (t, CH3). Ligand, 7.5 (m, aromatic protons), 6.87 (m, aromatic protons). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): SnCH2CH2CH2CH3, 31.60[Sn–CH2], 28.00[CH2], 25.31[CH2], 15.23[CH3]. Carbons of the ligands, 167.41 (CO2); 130.6, 128.61, 127.83 (aromatic carbons). Anal. calc. for: C46H86N2O8Sn4 (1,241.91): C, 42.53%; H, 6.50%; N, 2.20%. Found: C 42.55%; H, 6.65%; N, 2.26%.

Synthesis of [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2 (2)

The preparation of [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3-O)2 is similar to that of complex 1 with diphenylacetic acid 0.20 g (0.11 mmol) as carboxylate ligand 1:1 molar ratio. The mixture was stirred for around 3 h at room temperature and upon slow solvent evaporation, white-colored, prismatic crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis have grown. Yield: 64%; IR (ATR, cm−1): 1,550 ν(OCO)asym, 1,386/1,497 ν(OCO)sym, 254/143 ∆ν, 1,571 νC═C, 709 νaSnC2, 623 νs(Sn–O–Sn), 615 νsSnC2, 436 νSn–O. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): SnCH2CH2CH2CH3, δ = 1.86 (m, CH2–CH2); 1.59 (m, CH2); 0.92 (t, CH3). Ligand, 7.8 (s, CH), 7.5 (m, aromatic protons), 6.60 (m, aromatic protons). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): SnCH2CH2CH2CH3, 28.7[Sn–CH2], 26.5[CH2], 27.7[CH2], 13.5[CH3]. Carbons of the ligands, 175.1 (CO2); 153.1 (CH); 128.64, 127.56, 127.17 (aromatic carbons). Anal. calc. for: C88H116O10Sn4 (1,808.7): C, 58.75%; H, 6.44%. Found: C, 58.44%; H, 6.44%.

Synthesis of [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2(μ 2 -OH)2 (3)

The preparation of [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ 3 -O)2(μ 2 -OH)2 (3) followed that of complex 1, with (p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2 0.21 g (0.16 mmol) used as carboxylic acid in 1:2 molar ratio. The mixture was stirred for around 3 h at room temperature, and upon slow solvent evaporation, a white powder resulted. Yield: 53%; IR (ATR, cm−1): 1,623 ν(OCO)asym, 1,350 ν(OCO)sym, 273 ∆ν, 1,588 νC═C/C═N, 630 νs(Sn–O–Sn), 701 νaSnC2, 613 νsSnC2, 433 νSn–O. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): SnCH2CH2CH2CH3, δ = 1.70–1.65 (m, CH2–CH2); 1.35–1.20 (m, CH2); 0.95 (t, CH3). Ligand, 7.5 (m, aromatic protons); 6.87 (m, aromatic protons). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): SnCH2CH2CH2CH3, 31.46[Sn–CH2], 29.32[CH2], 26.36[CH2], 14.10[CH3]. Carbons of the ligands, 179.34 (CO2); 128.64, 127.56, 127.17 (aromatic carbons). Anal. calc. for: C46H86N2O8Sn4 (1,270.02): C, 43.50%; H, 6.83%; N, 2.21%. Found: C, 42.75%; H, 6.53%; N, 2.40%.

Materials and methods

Synthesis and spectroscopic materials

Pyridine-4-carboxylic acid, p-aminobenzoic acid, diphenylacetic acid, n-Bu2Sn(OCH3)2, and solvents were obtained from Aldrich and were used without further purification. Elemental analysis (C, H, and N) was performed using a Perkin–Elmer model 2400 CHN elemental analyzer. IR spectra in the range 4,000–400 cm−1 were recorded using FT-IR spectrophotometer Nicolet 710 TF-IR operated by the OMNIC software. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solution on BRUKER DPX-300 and BRUKER AVANCE II 400 spectrometers with Topspin 2.1 as software. The spectra were acquired at room temperature (298 K). 13C NMR spectra are broadband-proton-decoupled. The chemical shifts were reported in ppm with respect to the references and were stated relative to external tetramethylsilane for 1H and 13C NMR.

X-Ray crystallography

The X-ray crystallographic data were collected using a Rigaku Oxford-Diffraction Gemini-S diffractometer. All data were collected with graphite monochromated Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at 175 K. CrysAlis PRO (released on August 13, 2014, CrysAlis171.NET) (compiled on August 13, 2014, 18:06:01); cell refinement: CrysAlis PRO, Agilent Technologies, Version 1.171.37.35 (released on August 13, 2014, CrysAlis171.NET) (compiled on August 13, 2014, 18:06:01); data reduction: CrysAlis PRO, Agilent Technologies, Version 1.171.37.35 (released on August 18, 2014, CrysAlis171.NET) (compiled on August 13, 2014, 18:06:01); program(s) used to solve structure: Superflip (Palatinus and Chapuis, 2007); program(s) used to refine structure: CRYSTALS (Betteridge et al., 2003); molecular graphics: CAMERON (Watkin et al., 1996). Programs used for the representation of the molecular and crystal structures were Olex2 (Dolomanov et al., 2009) and Mercury (Macrae et al., 2008).

Accession codes

CCDC 2053062 (1) and 2053063 (2) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this article. Copies can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK (fax: int. Code +44 1223 336 033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk or http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar (Senegal), the University of Montpellier, Montpellier (France), for equipment and financial support.

-

Funding information: Authors state that no funding is involved.

-

Author contributions: Tidiane Diop: methodology, writing – original draft, writing – original draft preparation; Mouhamadou Birame Diop: refinement of structures; Cheikh Abdoul Khadir Diop: conceptualization, writing – original draft; Aminata Diasse-Sarr: conceptualization project administration; Mamadou Sidibe: conceptualization, project administration; Florina Dumitru: writing – original draft, supervision, Arie van der Lee: writing – original draft, crystal analysis, supervision.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Arjmand F., Parveen S., Tabassum S., Pettinari C., Organotin antitumor compounds: their present status in drug development and future perspectives. Inorg. Chim. Acta, 2014, 423, 26–37.10.1016/j.ica.2014.07.066Search in Google Scholar

Banti C.N., Hadjikakou S.K., Sismanoglu T., Hadjiliadis N., Anti-proliferative and antitumor activity of organotin(iv) compounds. An overview of the last decade and future perspectives. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2019, 194, 114–152.10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2019.02.003Search in Google Scholar

Baul T.S.B., Dutta D., Duthie A., Guedes da Silva M.F.C., Perceptive variation of carboxylate ligand and probing the influence of substitution pattern on the structure of mono- and di-butylstannoxane complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta, 2017, 455, 627–637.10.1016/j.ica.2016.05.008Search in Google Scholar

Beckmann J., Dakternieks D., Duthie A., Kuan F.S., Tiekink E.R.T., Synthesis and structures of new oligomethylene-bridged double ladders. How far can layers be separated? N. J. Chem., 2004, 28, 1268–1276.10.1039/B316009BSearch in Google Scholar

Betteridge P.W., Carruthers J.R., Cooper I.R., Prout K., Watkin D.J., “CRYSTALS Version 12: software for guided crystal structure analysis. J. Appl. Cryst., 2003, 36, 1487.10.1107/S0021889803021800Search in Google Scholar

Cavka J.H., Jakobsen S., Olsbye U., Guillou N., Lamberti C., Bordiga S., et al. A New Zirconium inorganic building brick forming metal organic frameworks with exceptional stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2008, 130, 13850–13851.10.1021/ja8057953Search in Google Scholar

Chandrasekhar V., Gopal K., Sasikumar P., Thirumoorthi R., Organooxotin assemblies from SnC bond cleavage reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev., 2005, 249, 17–18, 1745–1765.10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.028Search in Google Scholar

Chandrasekhar V., Nagendran S., Baskar V., Organotin assemblies containing Sn–O bonds. Coord. Chem. Rev., 2002, 235, 1–52.10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00178-9Search in Google Scholar

Diop T., Ndioléne A., Diop M.B., Boye M.S., Lee A.V.D., Dumitru F., et al., Synthesis, spectral (FT-IR, 1H, 13C) studies, and crystal structure of [(2,6-CO2)2C5H3NSnBu2(H2O)]2·CHCl3. Z. Naturforsch., B: Chem. Sci., 2021, 76, 127–132.10.1515/znb-2020-0195Search in Google Scholar

Dolomanov O.V., Bourhis L.J., Gildea R.J., Howard J.A.K., Puschmann H., OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis Program. J. Appl. Cryst., 2009, 42, 339–341.10.1107/S0021889808042726Search in Google Scholar

Eng G., Song X., Zapata A., De Dios A.C., Casabianca L., Pike R.D., Synthesis, structural and larvicidal studies of some triorganotin 2-(p-chlorophenyl)-3-methylbutyrates. J. Organomet. Chem., 2007, 692, 1398–1404.10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.11.030Search in Google Scholar

García-Zarracino R., Höpfl H., Rodríguez M.G., Bis(tetraorganodistannoxanes) as secondary building block units (SBUs) for the generation of porous materials − A three-dimensional honeycomb architecture cntaining adamantane-type water clusters. Cryst. Growth & Des., 2009, 9, 1651–1654.10.1021/cg801313uSearch in Google Scholar

Gielen M., Biesemans M., Willem R., Organotin compounds: from kinetics to stereochemistry and antitumour activities. Appl. Organomet. Chem., 2005, 19, 440–450.10.1002/aoc.771Search in Google Scholar

Hanif M., Hussain M., Saqib A., Bhatti M.H., Ahmed M.S., Mirza B., et al., In vitro biological studies and structural elucidation of organotin(iv) derivatives of 6-nitropiperonylic acid: Crystal structure of {[(CH2O2C6H2(o-NO2)COO)SnBu2]2O}2. Polyhedron, 2010, 29, 613–619.10.1016/j.poly.2009.07.039Search in Google Scholar

Kemmer M., Dalil H., Biesemans M., Martins J.C., Mahieu B., Horn E., et al., Dibuthyltin perfluoroalkanecarboxylates: synthesis, NMR characterization and in vitro antitumour activity. J. Organomet. Chem., 2000, 608, 63–70.10.1016/S0022-328X(00)00367-3Search in Google Scholar

Li Q., Wang F., Zhang R., Cui J., Ma C., Syntheses and characterization of organostannoxanes derived from 2-chloroisonicotinic acid: Tetranuclear and hexanuclear. Polyhedron, 2015, 85, 361–368.10.1016/j.poly.2014.08.039Search in Google Scholar

Li W., Du D., Liu S., Zhu C., Sakho A.M., Zhu D., et al., Self-assembly of a novel 2D network polymer: Syntheses, characterization, crystal structure and properties of a four-tin-nuclear 36-membered diorganotin(iv) macrocyclic carboxylate. J. Organomet. Chem., 2010, 695, 2153–2159.10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.06.001Search in Google Scholar

Ma C., Jiang Q., Zhang R., Synthesis and structure of a novel trinuclear 18-membered macrocycle of diphenyltin complexes with 2-mercaptonicotinic acid. J. Organomet. Chem., 2003, 678, 148–155.10.1016/S0022-328X(03)00472-8Search in Google Scholar

Macrae C.F., Bruno I.J., Chisholm J.A., Edgington P.R., McCabe P., Pidcok E., et al., Mercury CSD 2.0 – new features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures J. Appl. Cryst., 2008, 41, 466–470.10.1107/S0021889807067908Search in Google Scholar

Nakamoto K., Infrared and Raman spectra of inorganic and coordination compounds, 5th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 997.Search in Google Scholar

Najafi E., Amini M.M., Khavasi H.R., Weng Ng.S., The effect of substituents of the 1,10-phenanthroline ligand on the nature of diorgnotin(iv) complexes formation. J. Organomet. Chem., 2014, 749, 370–378.10.1016/j.jorganchem.2013.10.032Search in Google Scholar

Ng W. S., Monoclinic modification of bis(l2-pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylato)- κ4 O2,N,O6:O6; κ4, O2:O2,N,O6 - bis[aquadibutyltin(iv). Acta Cryst., 2011, E67, m277.10.1107/S1600536811002935Search in Google Scholar

Palatinus L., Chapuis G. J., SUPERFLIP– a computer program for the solution of crystal structures by charge flipping in arbitrary dimensions, Appl. Cryst., 2007, 40, 786–790.10.1107/S0021889807029238Search in Google Scholar

Pruchnik H., Latocha M., Zielinska A., Ułaszewski S., Pruchnik F.P., Butyltin(iv) 5-sulfosalicylates: Structural characterization and their cytostatic activity. Polyhedron, 2013, 49, 223–233.10.1016/j.poly.2012.10.025Search in Google Scholar

Shankar R., Dubey A., Hydrothermal approach for reticular synthesis of coordination assemblies with dicarboxylatotetramethyldistannoxanes as the secondary building Units. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem., 2020, 2020, 3877–3883.10.1002/ejic.202000657Search in Google Scholar

Valcarcel J.A., Razo-Hernandez R.S., Valdez-Velazquez L.L., Garcia M.V., Organillo, A.A.R., Vazquez-Vuelvas O.F. et al., Antitumor structure–activity relationship in bis-stannoxane derivatives from pyridine dicarboxylic and benzoic acids. Inorg. Chim. Acta., 2012, 392, 229–235.10.1016/j.ica.2012.06.029Search in Google Scholar

Vieira F.T., de Lima G.M., Maia J.R. da S., Speziali N.L., Ardisson J.D., et al., Synthesis, characterization and biocidal activity of new organotin complexes of 2-(3-oxocyclohex-1-enyl)benzoic acid. Eur. J. Med. Chem., 2010, 45, 883–889.10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.11.026Search in Google Scholar

Wang Q.F., Ma C.L., He G.F., Li Z., Synthesis and characterization of new tin derivatives derived from 3,5,6-trichlorosalicylic acid: Cage, chain and ladder X-ray crystal structures. Polyhedron, 2013, 49, 177–182.10.1016/j.poly.2012.09.057Search in Google Scholar

Wang S., Li Q-L., Zhang R-F., Du J-Y., Li Y-X., Ma C-L., Novel organotin(iv) complexes derived from 4-carboxybenzenesulfonamide: Synthesis, structure and in vitro cytostatic activity evaluation. Polyhedron, 2019, 158, 15–24.10.1016/j.poly.2018.10.048Search in Google Scholar

Watkin D.J., Prout C.K., Pearce L.J., CAMERON, Chemical Crystallography Laboratory, Oxford, UK. 1996.Search in Google Scholar

Wen G-H., Zhang R-F., Li Q-L., Zhang S-L., Ru J., Du J-Y., et al., Synthesis, structure and in vitro cytostatic activity study of the novel organotin(iv) derivatives of p-aminobenzenesulfonic acid. J. Organomet. Chem., 2018, 861, 151–158.10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.02.033Search in Google Scholar

Willem R., Bouhdid A., Mahieu B., Ghys L., Biesemans M., Tiekink E.R.T., et al., Synthesis, characterization and in vitro antitumour activity of triphenyl- and n-butyltin benzoates, phenylacetates and cinnamates. J. Organomet. Chem., 1997, 531, 151–158.10.1016/S0022-328X(96)06686-7Search in Google Scholar

Xiao X., Shao K., Yan L., Mei Z., Zhu D., Xu L., A novel macrocyclic organotin carboxylate containing a nona-nuclear long ladder. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 15387–15390.10.1039/c3dt50531fSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

Zhang R., Zhang S., Ma C., Syntheses, characterization and crystal structures of 1D and 2D organotin polymers containing 3-methyladic acid ligand. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym., 2012, 22, 500–506.10.1007/s10904-011-9628-xSearch in Google Scholar

Zhu C., Yang L., Li D., Zhang Q., Dou J., Wang D., Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure and antitumor activity of organotin(iv) compounds bearing ferrocenecarboxylic acid. Inorg. Chim. Acta, 2011, 375, 150–157.10.1016/j.ica.2011.04.049Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Tidiane Diop et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Embedded three spinel ferrite nanoparticles in PES-based nano filtration membranes with enhanced separation properties

- Research Articles

- Syntheses and crystal structures of ethyltin complexes with ferrocenecarboxylic acid

- Ultra-fast and effective ultrasonic synthesis of potassium borate: Santite

- Synthesis and structural characterization of new ladder-like organostannoxanes derived from carboxylic acid derivatives: [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2, [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2, and [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2

- HPA-ZSM-5 nanocomposite as high-performance catalyst for the synthesis of indenopyrazolones

- Conjugation of tetracycline and penicillin with Sb(v) and Ag(i) against breast cancer cells

- Simple preparation and investigation of magnetic nanocomposites: Electrodeposition of polymeric aniline-barium ferrite and aniline-strontium ferrite thin films

- Effect of substrate temperature on structural, optical, and photoelectrochemical properties of Tl2S thin films fabricated using AACVD technique

- Core–shell structured magnetic MCM-41-type mesoporous silica-supported Cu/Fe: A novel recyclable nanocatalyst for Ullmann-type homocoupling reactions

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel lead coordination polymer: [Pb(L)(1,3-bdc)]·2H2O

- Comparative toxic effect of bulk zinc oxide (ZnO) and ZnO nanoparticles on human red blood cells

- In silico ADMET, molecular docking study, and nano Sb2O3-catalyzed microwave-mediated synthesis of new α-aminophosphonates as potential anti-diabetic agents

- Synthesis, structure, and cytotoxicity of some triorganotin(iv) complexes of 3-aminobenzoic acid-based Schiff bases

- Rapid Communications

- Synthesis and crystal structure of one new cadmium coordination polymer constructed by phenanthroline derivate and 1,4-naphthalenedicarboxylic acid

- A new cadmium(ii) coordination polymer with 1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylate acid and phenanthroline derivate: Synthesis and crystal structure

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel lead dinuclear complex: [Pb(L)(I)(sba)0.5]2

- Special Issue: Theoretical and computational aspects of graph-theoretic methods in modern-day chemistry (Guest Editors: Muhammad Imran and Muhammad Javaid)

- Computation of edge- and vertex-degree-based topological indices for tetrahedral sheets of clay minerals

- Structures devised by the generalizations of two graph operations and their topological descriptors

- On topological indices of zinc-based metal organic frameworks

- On computation of the reduced reverse degree and neighbourhood degree sum-based topological indices for metal-organic frameworks

- An estimation of HOMO–LUMO gap for a class of molecular graphs

- On k-regular edge connectivity of chemical graphs

- On arithmetic–geometric eigenvalues of graphs

- Mostar index of graphs associated to groups

- On topological polynomials and indices for metal-organic and cuboctahedral bimetallic networks

- Finite vertex-based resolvability of supramolecular chain in dialkyltin

- Expressions for Mostar and weighted Mostar invariants in a chemical structure

Articles in the same Issue

- Embedded three spinel ferrite nanoparticles in PES-based nano filtration membranes with enhanced separation properties

- Research Articles

- Syntheses and crystal structures of ethyltin complexes with ferrocenecarboxylic acid

- Ultra-fast and effective ultrasonic synthesis of potassium borate: Santite

- Synthesis and structural characterization of new ladder-like organostannoxanes derived from carboxylic acid derivatives: [C5H4N(p-CO2)]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2, [Ph2CHCO2]4[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2, and [(p-NH2)-C6H4-CO2]2[Bu2Sn]4(μ3-O)2(μ2-OH)2

- HPA-ZSM-5 nanocomposite as high-performance catalyst for the synthesis of indenopyrazolones

- Conjugation of tetracycline and penicillin with Sb(v) and Ag(i) against breast cancer cells

- Simple preparation and investigation of magnetic nanocomposites: Electrodeposition of polymeric aniline-barium ferrite and aniline-strontium ferrite thin films

- Effect of substrate temperature on structural, optical, and photoelectrochemical properties of Tl2S thin films fabricated using AACVD technique

- Core–shell structured magnetic MCM-41-type mesoporous silica-supported Cu/Fe: A novel recyclable nanocatalyst for Ullmann-type homocoupling reactions

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel lead coordination polymer: [Pb(L)(1,3-bdc)]·2H2O

- Comparative toxic effect of bulk zinc oxide (ZnO) and ZnO nanoparticles on human red blood cells

- In silico ADMET, molecular docking study, and nano Sb2O3-catalyzed microwave-mediated synthesis of new α-aminophosphonates as potential anti-diabetic agents

- Synthesis, structure, and cytotoxicity of some triorganotin(iv) complexes of 3-aminobenzoic acid-based Schiff bases

- Rapid Communications

- Synthesis and crystal structure of one new cadmium coordination polymer constructed by phenanthroline derivate and 1,4-naphthalenedicarboxylic acid

- A new cadmium(ii) coordination polymer with 1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylate acid and phenanthroline derivate: Synthesis and crystal structure

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel lead dinuclear complex: [Pb(L)(I)(sba)0.5]2

- Special Issue: Theoretical and computational aspects of graph-theoretic methods in modern-day chemistry (Guest Editors: Muhammad Imran and Muhammad Javaid)

- Computation of edge- and vertex-degree-based topological indices for tetrahedral sheets of clay minerals

- Structures devised by the generalizations of two graph operations and their topological descriptors

- On topological indices of zinc-based metal organic frameworks

- On computation of the reduced reverse degree and neighbourhood degree sum-based topological indices for metal-organic frameworks

- An estimation of HOMO–LUMO gap for a class of molecular graphs

- On k-regular edge connectivity of chemical graphs

- On arithmetic–geometric eigenvalues of graphs

- Mostar index of graphs associated to groups

- On topological polynomials and indices for metal-organic and cuboctahedral bimetallic networks

- Finite vertex-based resolvability of supramolecular chain in dialkyltin

- Expressions for Mostar and weighted Mostar invariants in a chemical structure