Abstract

This article examines a text known as the ‘Admonitio synodalis’ as evidence for episcopal expectations of local priests in the tenth and eleventh centuries. The ‘Admonitio’ is generally considered a stable text that represented and fostered continuity within the Church, but this article highlights instead its early development. It begins by identifying a previously unedited version of the text found in some tenth-century manuscripts, arguing that this long recension is the closest to the original form. It then turns to how the text was adapted in the tenth century, notably by Bishop Rather of Verona. It finally examines the changes made to the text when it was incorporated into the liturgy of synodal ordines in the early eleventh century. A transcription of the tenth-century recension, based on a Brussels manuscript, is provided as an appendix.

[*]When thinking about the Carolingian political and religious order, historians have tended to focus their attention on emperors, bishops and counts [1]. However, recent work has shown how local priests in the countryside occupied a central role in the Carolingian ideological programme too [2]. These priests were targeted by a new genre of text, the so-called episcopal capitularies which flourished in the ninth century, and which set out for the first time a tailored framework of expectations for priests living in rural communities [3]. And they were materially supported by a new kind of revenue, an obligatory and – crucially – territorialised tithe [4]. But what happened to these local priests after the fragmentation of the Carolingian order that had defined, regulated and supported them? How did the position and role of local priests change in the long tenth century? This article addresses this question by examining episcopal expectations of local priests, as expressed through an important text known as the ‘Admonitio Synodalis’.

The ‘Admonitio’ is an address or homily, suitable for delivery at a diocesan synod when a bishop gathered the priests of his diocese [5]. Its author is unknown, though some manuscripts ( falsely ) attribute it to a Pope Leo [6]. Over its ninety or so clauses ( the precise number varies considerably from manuscript to manuscript, as we shall see ), it concisely outlines the parameters for how priests should behave and how they should interact with their parishioners ( parocchiani ). For Johannes Laudage, who in 1984 analysed its contents as part of his classic investigation of the Priesterbild or “image of the priest”, the ‘Admonitio’ was an attempt “to bring together the most important regulations about priestly life from a pastoral point of view.” [7] It covers where priests should live, at what time they should get up in the morning, which vestments they should wear when celebrating Mass and how they should preach, alongside prohibitions on drinking and accepting bribes, and much else besides.

None of these instructions was particularly novel or unusual. To the contrary, the ‘Admonitio’ reads like a précis of Carolingian episcopal capitularies such as those issued by Frankish bishops such as Theodulf of Orléans and Hincmar of Reims, and subsequently summarised by the monk Regino of Prüm, to regulate the lives of the rural clergy living in their dioceses. What was unusual about the ‘Admonitio’ was the scale of its transmission. Wilfried Hartmann has talked of a “hugely wide dissemination”, Rudolf Pokorny described it as “one of the most ‘successful’ works of early medieval church law”, and Joseph Avril emphasised its “extraordinary diffusion.” [8] At least 139 manuscript witnesses survive, from countries across Western Europe including England, Italy, Spain, France and Germany [9]. Most of these manuscripts date from the eleventh and twelfth centuries. But although the ‘Admonitio’ was less often copied from the thirteenth century onwards – though a Polish bishop transcribed it as late as 1521 – its influence lived on indirectly [10]. Parts of the text were frequently integrated into later medieval episcopal statutes. For instance, its clause requiring priests to know the prayers for the Mass was copied verbatim in the 1290s in Mende, in 1298 in Novara, in 1310 in Bologna, in 1338 in Pavia and in 1382 in Buda [11]. Even in the seventeenth century, it seemed current enough for Étienne Baluze to suggest tongue-in-cheek that it should be revived to educate the “most wretched priests” of his own day [12]. Though it was not included in the twelfth-century Roman pontifical, an edited version was incorporated into a revised Roman pontifical published in 1485, and remained in this tradition until 1962 [13].

This scale of dissemination and influence has meant that the ‘Admonitio’ has often been seen as a vehicle through which expectations around rural priests developed in early Middle Ages were transmitted to later periods. For the most part this has been framed as a history of continuity. Indeed, for Robert Amiet, who edited the text in 1964, the most remarkable thing about the ‘Admonitio Synodalis’ was its stability and longevity, which meant that priests in the twentieth century were still being exhorted through much the same text as they had been over a millennium earlier in the eighth century, when Amiet thought the ‘Admonitio’ had first been compiled. Through the ‘Admonitio’, Amiet wrote, “one sees appear the eternal face of the holy Church.” [14] Joseph Avril took a similar view, seeing the ‘Admonitio’ as representing a fundamental continuity into and through the tenth century: “[ … ] the impulse given by the Carolingian reformers was maintained as far as the clergy entrusted with churches were concerned.” [15]

In this article, however, I offer a different perspective. Rather than emphasising the stability and longevity of the ‘Admonitio Synodalis’, I seek to explore its dynamics and its evolution. By tracking the changes that were made to this text in the tenth and eleventh centuries, we can detect subtle shifts in emphasis in the standards by which local priests were measured between the Carolingians and the so-called Gregorian Reform. First of all, though, we need to consider Amiet’s edition in more detail, since, as will become clear, this edition has done a great deal to shape subsequent discussion of the text.

1. Amiet’s edition of the ‘Admonitio’

When Robert Amiet published his edition in 1964, he was confident it would never be superseded, declaring that “I dare to assert that new discoveries will not in any case change my conclusions.’’ [16] There is no doubt that his edition was a major work of scholarship. Yet it is now apparent how far it was shaped by two questionable assumptions. In the first place, as already noted, Amiet thought the ‘Admonitio’ had been compiled around the year 800 or so. That meant that obvious overlaps with the collection of canon law material compiled by Regino of Prüm, the ‘Libri duo de synodalibus causis et disciplinis ecclesiasticis’, had to reflect Regino’s borrowing from the text [17]. Secondly, Amiet thought that the earliest form of the ‘Admonitio’ was preserved in a set of liturgical books for bishops known as the ‘Pontifical Romano-Germanique’, or PRG. Amiet accepted the theory of Michel Andrieu in the 1930s that the PRG had been produced in Mainz around 950 [18]. For Amiet, this meant that the version of the ‘Admonitio’ in the PRG was “both the oldest and the shortest of all, and is thus the one closest to the original’’ [19], and so he built his edition around it.

These two assumptions determined how Amiet presented the text, in two connected ways. Firstly, they meant that Amiet did not prioritise the evidence of the earliest surviving manuscripts. He knew of no manuscript that was older than c. 950, when he thought the PRG was composed, so there was no reason to give the version of the ‘Admonitio’ in early surviving manuscripts special weight. Indeed, it is clear that Amiet did not attempt an exhaustive search for early manuscripts, as we shall see. Secondly, these assumptions justified his division of the ‘Admonitio’ into an original short form, as preserved in the PRG, and a separate appendix, which he thought was an entirely independent text added later in some manuscripts. The fact that both the ‘appendix’ and the ‘original’ were linked to Regino of Prüm’s canon law collection simply demonstrated in Amiet’s view that Regino had access to a later version of the ‘Admonitio’ that included its appendix [20].

Today, neither of these assumptions is generally accepted. To begin with, in 1985 Rudolf Pokorny showed in a brilliantly-argued article that the ‘Admonitio’ is related to an amended version of Regino of Prüm’s canon law collection, rather than to the collection’s earliest form [21]. At the heart of Pokorny’s demonstration was a single clause of the ‘Admonitio’ ( clause 62 in the edition of Amiet ), present in all versions of the text. This clause is based on questions 56–58 in Regino’s first ‘Inquisitio’ in his canon law collection. Of these questions, the format of 56 and 57 gives the impression that they are later insertions. These two questions are absent from two manuscripts of Regino’s work, Trier SB 927 and Luxembourg Bibliothèque Nationale 29, which Pokorny argued represents the original form of the so-called ‘genuine’ version. They are present in two other manuscripts of the ‘genuine’ version of Regino’s work ( Gotha, Forschungsbibliothek, Memb. II 131, fol. 4r and Arras, Mediathèque Municipale, MS 723 [ 675 ] at fol. 4v ), but are marked out graphically in the Arras manuscript through capitalisation with green highlighting. Pokorny deduced that these questions were later additions to Regino’s work. Their appearance in the ‘Admonitio’ clause 62 therefore proves that the ‘Admonitio’ relied on a revised version of Regino’s work, and thus must have been compiled after Regino finished the first version.

As for the PRG, Henry Parkes has convincingly argued that the PRG tradition, instead of dating to the mid tenth century as Michel Andrieu conjectured, is in reality an early eleventh-century compilation, probably linked to the court of Emperor Henry II in the 1010s [22]. That is when the PRG’s earliest manuscripts were produced, notably Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc.Lit.53, which is “the earliest securely datable witness to the PRG tradition” once “over-optimistic” early datings of other manuscripts are dismissed [23]. The version of the ‘Admonitio’ in the PRG therefore does not represent a version of the text from c. 950, but one from c. 1010.

The redating of the PRG tradition, and the re-evaluation of the relationship between Regino and the ‘Admonitio’, together have major implications for the value of Amiet’s edition, and for how we think about the ‘Admonitio Synodalis’ – and, by extension, for the normative framework for local priests in the post-Carolingian period [24]. To explore these, let us now turn to the earliest surviving manuscripts of the ‘Admonitio’.

2. The earliest manuscripts of the ‘Admonitio’

Amiet’s edition drew on three tenth-century manuscripts, all of which he rightly associated with Bishop Rather of Verona, whose adaptation of the ‘Admonitio’ will be discussed below [25]. However, there survive no fewer than six other manuscript witnesses to the ‘Admonitio’, dating to c. 1000 or earlier, which Amiet did not take into account [26]. Four of these manuscripts present a version of the text that has not been edited before [27]. Let us examine each of these four in turn.

To begin with, there is a version of the ‘Admonitio’ on fols. 1v–3v of a manuscript of the revised ( or ‘interpolated’ ) version of Regino’s ‘Libri duo’, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 694, which Hartmut Hoffman dated to c. 1000 and localised to Mainz [28]. The same hand in Hoffmann’s estimation also copied out a letter in the manuscript dating to 997, giving a terminus a quo. Around the same time, the ‘Admonitio’ was also included in Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, MS 1979, on fols. 160–162v. This manuscript is again late tenth-century ( or possibly early eleventh-century ) from eastern France or western Germany, and contains mostly legal materials linked to the exercise of episcopal duties. The ‘Admonitio’ was included in the manuscript’s original design, as part of a collection of material known as the ‘Collectio 234 capitulorum’ [29].

Two further manuscripts with the ‘Admonitio’ seem to be a little older. Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, A 46 inf. is a late ninth-century manuscript from Reims which mostly contains Carolingian capitularies, and which was taken to Italy at some point before the twelfth century [30]. The final quire of this manuscript ( fols. 152r–159v ) begins with some Roman law extracts in a ninth-century hand, which seem to have been part of the original manuscript since they are indexed at the beginning. Into the blank pages of this final quire was copied the ‘Admonitio’ on fols. 158v–159v ( at the end of the codex ), written in an unpractised hand which Bischoff estimated to be mid tenth-century ( figure 1 ) [31]. Unfortunately, the Milan manuscript only has an incomplete text, due to the loss of a final folio.

Finally, Brussels, Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België, MS 495–505 ( Gheyn 2494 ) is a copy of the Dionysio-Hadriana canon law collection, made in northern Francia in the late ninth century [32]. Subsequently extra quires were added to it, both at the front and the back. At the very front is what seems to be a bifolium quire ( fols. A–3v ), made up of an extract of the first twenty chapters of the second episcopal capitulary issued by Archbishop Hincmar of Reims in 852 ( though without attribution here ), followed immediately by the ‘Admonitio’ ( figure 2 ). The two texts are on the same theme, and were copied by the same hand. Pokorny, relying on Bischoff, thought the script of the Hincmar entry, and thus of the ‘Admonitio’, was from the first half of the tenth century, in “Belgian style” [33].

Milan, Bibliotheca Ambrosiana, A 46 inf., fol. 158v

Brussels, KBR, MS 495–505, fol. A

All four of these manuscripts present a version of the ‘Admonitio’ which includes what Amiet thought was its ‘appendix’ ( the Milanese manuscript has lost the end of the text, but enough survives to be certain of this point ). The Vienna manuscript, from c. 1000, separates out this part of the text from the rest by rubrication and a short concluding clause, but the three other manuscripts do not; in these the ‘Admonitio’ is simply presented as a single long text. All four manuscripts also contain two other clauses which Amiet thought were later additions to the text, Amiet’s clause 30b about not singing Mass alone and clause 66b about not travelling without a stole.

What is more, the text in these manuscripts also differs slightly from that edited by Amiet in two respects. In the first place, their version of the ‘appendix’ has some small variants unknown to Amiet [34]. Secondly, and more significantly, all four of these manuscripts also include at the end of the ‘Admonitio’ two clauses which until now have been attributed to Bishop Rather of Verona ( though the Milan manuscript regrettably breaks off half way through the first extra clause ):

De ordinandis pro certo scitote [ … ] – that no one will be promoted unless they have a basic level of education ( aliquantum eruditi ). The text can be linked, like the rest of the ‘appendix’, to Regino of Prüm’s canon law collection.

Videte si absque [ … ] – that without knowledge ( scientia ) of the issues discussed earlier, the cleric will not be able to bring his parishioners to salvation.

When in 1949 Fritz Weigle edited Rather’s ‘Synodica’, which quoted the ‘Admonitio’ extensively ( as discussed below ), he relied on previous editions of the ‘Admonitio’ to decide where this text ended, and where Rather’s own text began. No previous edition had included these clauses, so Weigle reasonably assumed they were written by Rather [35]. However, the presence of these clauses in the four tenth-century manuscripts just discussed suggests that Rather was quoting more than Weigle realised. The converse possibility that these manuscripts were all directly quoting Rather’s ‘Synodica’ can be quickly eliminated, since their version of the text cannot have been copied from his ( Rather’s version is discussed in more detail below ).

Of course, it could be that these manuscripts, though two of them are earlier than any others that survive and presumably quite close to the text’s date of origin, might nevertheless preserve a later version of the ‘Admonitio’. In other words, it is possible in principle that the short version of the ‘Admonitio’ present in later manuscripts is closer to the archetype – as the saying has it, recentiores non deteriores. Yet given the reliance of the so-called appendix on Regino of Prüm’s canon law collection, this would have required some tenth-century editor to have identified Regino as the sole source for the ‘Admonitio’, and to have gone back to Regino to create the appendix; and, in the case of the so-called addition of Amiet’s clause 66b, to have added this material in the right place in Regino’s sequence [36]. This is a far-fetched scenario. Much more likely is that the ‘Admonitio’ began as a long text which was subsequently shortened, and that the tenth-century manuscripts represent a version close to this original long-form text [37].

This has significant implications for the original text. In the first place, it is revealed to have been closer to Regino of Prüm’s collection of canon law than has been realised. True, not every aspect of Regino’s original compilation of questions to ask the local priest was taken forward. The ‘Admonitio’ dropped Regino’s requirements for the priest’s local endowment, for his possession of incense, for the priest’s physical integrity, and for his possession of Gregory the Great’s homilies. Conversely, it emphasised priestly vestments, treatment of excommunicates and the security of the holy chrism: all items present in Regino’s canon law collection, but not highlighted in his initial ‘inquisition’ [38]. Nevertheless, the ‘Admonitio’ preserves a reasonably broad summary of Regino’s themes, themselves based on Carolingian-period material.

However, the version of the text found in these early manuscripts also has significant implications for the use and adaption of the ‘Admonitio’, which we shall now go on to explore.

3. Rather of Verona’s use of the ‘Admonitio’

The earliest known adaption of the ‘Admonitio’ was by Rather of Lobbes, who served intermittently as bishop of Verona ( 931–934, 946–948 and again 961–968 ) [39]. In 966, Bishop Rather embedded a large section of the ‘Admonitio’ into his ‘Synodica’, a letter of admonishment to the clerics of Verona [40]. He wrote this letter in the wake of a rather stormy diocesan synod, where he had discovered to his dismay that most of the clerics of his diocese did not even know the Apostle’s Creed. So he circulated the ‘Synodica’ and asked them to copy it and to learn its instructions by heart, to which all the urban clergy and all the rural clerics ( but not the cathedral canons ) eventually agreed [41]. In his insertion of the ‘Admonitio’, we see the text working as a benchmark for priestly knowledge and competence, just as we may imagine it was originally intended to do.

The ‘Synodica’ begins and ends with Rather’s own material. At the beginning, he emphasises to his audience of Verona clerics the need to know three Creeds, the importance of Sundays, and the importance of sexual purity. He then copied a version of the ‘Admonitio’, stating that this is a quotation, and in the manuscripts capitalising the start of the citation. After the ‘Admonitio’, Rather continued the ‘Synodica’ to emphasise a number of further themes: the fair distribution of church revenues, times of fasting and abstinence, the reservation of public sins for episcopal judgement, some required characteristics for ordination, including that the priest should not stutter, and the insistence that saints’ days be celebrated through fasting rather than feasting. These instructions seem to be specific to Rather’s audience, and perhaps to Rather’s own personal priorities. In a way, we can see the entire ‘Synodica’ as an adaption of the ‘Admonitio Synodalis’, to which Rather added material which he considered was lacking but essential [42].

But the version of the ‘Admonitio’ copied in the ‘Synodica’ also has some significant variants compared to the tenth-century recension discussed in the previous section. For example, the ‘Admonitio’’s instruction ( Amiet clause 8 ) in the Vienna, Milan and Brussels manuscripts that the priest should have his cell next to the church, and not allow women in his house, perhaps implied that he could have both a cell and a house; in the ‘Synodica’, the ‘Admonitio’ text is adapted to make clear that the cell was also the priest’s residence. The three annual Masses which the ‘Admonitio’ instructed laymen to attend ( Amiet cl. 64: Christmas, Easter and Pentecost ) were changed to four by adding Maundy Thursday, which was somewhat unusual [43].

The ‘Synodica’’s version of the ‘Admonitio’ also misses out some material present in the earliest manuscripts, beyond the prefatory material:

Amiet Clause 19: This clause forbids the use of a glass or wooden chalice in the Mass, insisting on metal.

Amiet Clauses 28 and 29: These two clauses require the church to be roofed and fenced.

Amiet Clause 31: This clause requires priests to have a junior clerical assistant, who can assist with the Mass and other liturgical duties.

Amiet Clause 40 and Clause 41: These two clauses required the priest to preach on Sundays and feastdays, and to base his preaching on the Bible.

Amiet Clauses 53, 54 and 55: The first of these clauses forbade a priest to hold multiple churches unassisted; the second forbade churches to be divided up; and the third forbade giving Mass to parishioners from elsewhere unless they were travelling.

In principle, it cannot be ruled out that some of these differences existed already in Rather’s exemplar, in whatever copy of the ‘Admonitio’ he had at his disposal. For instance, a lost manuscript from Neresheim, which may have dated from the early eleventh century, similarly adds Maundy Thursday to the list of times when Mass should be taken [44]. Was this text dependant on Rather’s version, or was Rather copying from it or some related manuscript? Ultimately such questions are hard to resolve, given the wide diffusion of the ‘Admonitio’ and the practice of ‘lateral contamination’, that is of scribes borrowing readings from different traditions [45]. However, there is good reason to suppose that Rather had direct access to the long version, since his distinctive hand made some additions to the liturgical formula for excommunication on folio 204v of Brussels, KBR, MS 495–505 [46]. Whether the ‘Admonitio’ was already copied into this manuscript when Rather saw it is impossible to say for sure, but it is at least possible that Rather used the version of the ‘Admonitio’ in this manuscript, or a copy made of it, in drafting his ‘Synodica’.

In this light, Rather may have been adapting the ‘Admonitio’ to suit northern Italian circumstances, where he was serving as bishop. It is generally supposed that the organisation of rural pastoral care differed slightly from that north of the Alps in much of the Middle Ages [47]. There were fewer churches with full baptismal rights, which were known as pievi; they tended therefore to be better endowed, and often controlled various dependent chapels. Moreover, there were more junior clerics in Italy than in Francia [48]; as a result, most churches had groups of clergy serving them, with fewer isolated priests than in the north.

As it happens, we know a great deal about one of the fifty or so tenth-century pievi in Verona’s diocese, San Pietro of Tillida, whose priests Bishop Rather would have met during his incumbency in Verona. They would have been invited to attend Rather’s 966 diocesan synod, and Rather may have had them in mind when drafting his ‘Synodica’ [49]. San Pietro was located about 40 kilometres south-east of Verona. Its extensive holdings, revenues and indeed books are listed in a remarkable mid tenth-century inventory that survives on four sheets of parchment [50]. This inventory tells us that San Pietro had twelve vineyards, sixty fields and thirty meadows in direct use. It also owned lands in eleven settlements ( vici ), whose yields were carefully broken down, counting the chickens and the eggs as well as the cash owed, which amounted to an income of hundreds of solidi each year. In addition to these properties, the church benefited from a significant tithe income from twelve villages, totalling ‘in a medium year’ 750 modii of grain, 80 amphoras of wine, 350 lambs and piglets, and 300 measures of linen. San Pietro also owned two dependent chapels. Within the church itself were to be found a missal, two antiphonaries, a lectionary, and two collections of homilies, as well as three chalices and plenty of liturgical fabrics of silk and linen. San Pietro was, it is clear, a prospering local church.

These features may go some way to explain Rather’s adaption of the ‘Admonitio Synodalis’. The clauses about Sunday preaching were probably cut simply because Rather had addressed Sundays extensively in the first part of his letter, positioning them as miniature Easters. But the other changes seem more significant. To judge from San Pietro, the baptismal churches around Verona may well have been generally better equipped than many of those targeted in the ‘Admonitio’, so perhaps they all had expensive metal chalices; since they were better endowed, these churches may well also have been in better condition, hence no need to emphasise roof and fence repair; there was no need to insist on a clerical assistant if this was normal practice. The clause about holding multiple churches was not relevant in Verona; conversely, dividing up rural churches was very common in Italy, and perhaps not worth fighting over.

In short, it seems that Rather may have adapted the ‘Admonitio’ to fit the circumstances of his audience, in so doing illustrating the differences he recognised between local churches in northern Italy and the Lotharingia where he had trained. Rather is often considered as a man of letters rather than a practical administrator, but his adaption of the text shows that the two activities were not always opposed. Still, while the organisation of rural pastoral care differed in northern Italy compared to elsewhere, the differences were not so great as to make the ‘Admonitio’ entirely redundant.

Differences within Rather’s version of the ‘Admonitio’

It is possible to go a step further in examining Rather’s edits, by looking more closely at the surviving manuscripts. Amiet incorporated the version of the ‘Admonitio’ in Rather’s ‘Synodica’ in his edition, but on the basis of only two manuscripts, Laon, Médiathèque Municipale, MS 274 ( S1 in Amiet’s edition ) and Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 6340 ( S2 in Amiet’s edition ). Amiet seems not to have known about a third manuscript with the ‘Synodica’, Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, MS Phill. 1676 ( the so-called Egino Codex ). All three of these manuscripts are tenth-century in date, and all three seem to have been made in Verona; Rather himself wrote in the Berlin and Munich manuscripts [51]. The Berlin text is unfortunately fragmentary because the first folio is missing, and its text thus begins halfway through clause 23 ( and the first few folios are currently only available via a poor-quality black and white microfilm ); but there is good reason to suppose that Berlin was the oldest of the ‘Synodica’ manuscripts, as Benedetta Valtorta has already suggested, and where Rather began to work out his ideas [52].

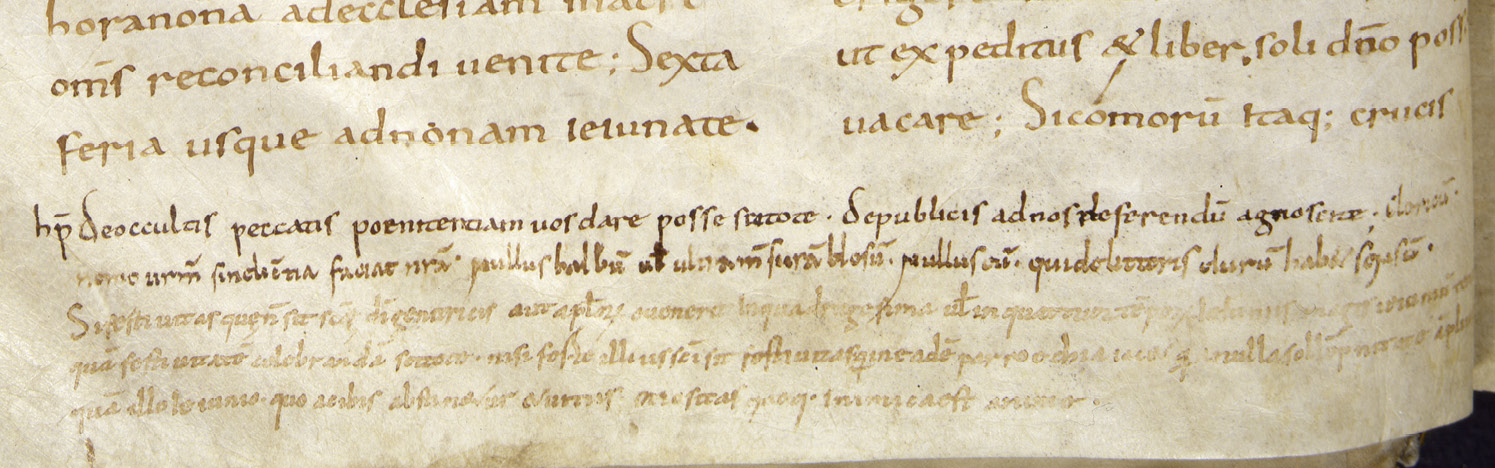

For instance, in a part of the ‘Synodica’ not borrowed from the ‘Admonitio’, Rather talks about the importance of Easter. In the margins of the Berlin manuscript, the scribe added a line about penitents ( De occultis peccatis ), and to this Rather of Verona, in his own hand, added another clause. In both the Laon and Munich manuscripts, this two-part marginal note is integrated into the main text. Subsequently, Rather decided to add another comment about feasting. This he added, again in his own hand, as a marginal note in Berlin immediately underneath the first annotation, though in a different ink ( figure 3 ). This note was added to the Munich manuscript in the margin; in the Laon manuscript, it is fully integrated into the main text. As Valtorta has argued, this suggests that the Berlin manuscript was Rather’s working copy, and the Munich manuscript was also kept to hand, while the Laon manuscript was copied from one or both [53].

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Handschriften und Historische Drucke, Ms. Phill. 1676, fol. 8v

This makes some differences in the ‘Admonitio’ text in these three ‘Synodica’ manuscripts worth studying. Not all these differences are necessarily significant. Apart from trivial orthographical differences ( e. g. pollice/police ), there are a couple of omissions. Laon MS 274 omits a clause about women not singing in the churchyard ( Amiet clause 70 ). Munich Clm 6340 omits a clause about not acquiring a church through secular power ( Amiet clause 50: present in Berlin and Laon; surprisingly Amiet indicated it was absent from the Rather tradition; evidently he relied on the Munich, not the Laon manuscript ). Munich also omits the clause about not going on a journey without the liturgical item known as a stole ( Amiet clause 66bis ). These omissions could have been accidental, perhaps eye-skip in a sequence of clauses with similar beginnings.

However, other differences are more likely to be deliberate revisions, reflecting changes in thinking, whether based on experience or, perhaps, access to other written sources. In the Munich manuscript, a clause about not singing Mass whilst wearing spurs and daggers, not present in the Brussels or related manuscripts, is added into the margin ( Amiet clause 31bis ) [54]: Nullus cum calcariis, quos sporones rustice dicimus, et cultellis extrinsecus dependentibus missam cantet, quia indecens et contra regulam ecclesiasticam est.

The Berlin manuscript’s incomplete state means we can say nothing about the presence or absence of this clause there. But in the Laon manuscript, it was copied in slightly abbreviated form in the main text, in a different place ( after Amiet’s clause 16 ) [55]: Nullus cum cultellis foris pendentibus, nullus cum calcaribus [ … ].

Rather also included new instructions on the gesture for blessing ( Amiet clause 31ter, ‘Calicem et oblatam [ … ]’ ), again missing from the Brussels and related manuscripts of the ‘Admonitio’ [56]. This forms a marginal addition in the Berlin manuscript, possibly in Rather’s own hand, but was included in the main text in Laon and Munich, which latter even includes a little illustration ( figure 4 ).

And Rather seems to have changed his mind about the nature of rural priests’ education. The Berlin copy of Rather’s ‘Synodica’ follows exactly the ‘Admonitio’’s clauses about possession of written copies of the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer, understanding them and preaching them to the people, and knowing the prayers and the canon of the Mass by heart ( Amiet clauses 85 and 87 ). But in the Laon and Munich manuscripts, some edits have been made [57]. Priests should have written copies of the Creed and Lord’s Prayer but only ‘if possible’; and if they do not understand them, they should at least keep and believe them [58]. And priests should understand the prayers and canon of the Mass; but if not, they should at least know them by heart [59]. The implication is that Rather had decided, perhaps based on his interactions with priests at places such as San Pietro of Tillida, to soften the expectations of priestly competence.

Munich, BSB, Clm 6340, fol. 36v ( CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 )

Finally, these two manuscripts also add a line about teaching to the De ordinandis clause of the ‘Admonitio’. In the Berlin manuscript, the text says that priests need to have spent time either in the city or in a monastery for their education; in the Laon and Munich manuscripts, there is the further possibility of education from “a learned man” ( one thinks here of Rather’s own famous erudition ) [60].

At one level these variations are just another indication of the basic instability of manuscript text. But this goes further than simply scribal error. Rather and his scribes treated the text with a degree of plasticity: for them the ‘Admonitio’ was still a working text, a resource, rather than a monument. It would be good to know which version of his text Rather circulated amongst the rural clergy of Verona, and how many copies he made, but there is sadly no way of finding out.

The ‘Admonitio’ in Bavaria

Rather was a well-travelled man. Born in Lotharingia and a bishop in northern Italy, we know he also spent time in Mainz and, it seems, Bavaria [61]. As it happens, Rather’s work was also known in Bavaria from an early date. Natalia Daniel suggests that Bishop Abraham of Freising ( d. 993/994 ) was interested in Rather’s writings and was responsible for acquiring Munich Clm 6340, one of the three tenth-century manuscripts of Rather’s ‘Synodica’ discussed above [62]. Bishop Abraham, who was a great book collector, seems to have had an interest in Ottonian literary scholars, since he also collected works by Liudprand of Cremona [63].

We can perhaps see Rather’s textual influence in Freising through the manuscript Munich Clm 6241, a canonical collection from late tenth-century Freising. This manuscript contains a copy of a Carolingian episcopal capitulary ( the ‘Capitula Frisingensia tertia’ ) [64]. It also contains various extracts from another Munich manuscript, Clm 6245, which have been rearranged. However, amongst this rearranged material are inserted some extra texts. As well as the famous ‘althochdeutsche Klerikereid’, an oath taken by clerics swearing allegiance to their bishop, we find there a version of the ‘Admonitio’, copied on folios 97–100. As was noted by Amiet and more recently by Günther Glauche, the version of the ‘Admonitio’ in this manuscript, Clm 6241, is closely linked to the version in Munich Clm 6340, which has Rather’s ‘Synodica’ [65]. Mirroring the ‘Synodica’, it omits the ‘Admonitio’’s otherwise standard opening ( Fratres [ … ] ), as well as all the other clauses that Rather omitted, and it includes the so-called ‘appendix’, as Rather did too.

It is intriguing, and a little puzzling, that the Freising scribe of Munich Clm 6241 was apparently able to extract the text so neatly from the rest of Rather’s ‘Synodica’. Perhaps the scribe was able to identify the ‘Admonitio’ as a quotation simply from the ‘Synodica’’s content. After all, Rather introduced the text with an “as is written elsewhere” and a capitalisation, and the Freising scribe seems to have taken the “et cetera” to mark the end of the text. But perhaps the information that the middle of the ‘Synodica’ formed a separate text was passed on orally; it is also possible that the abbreviated version of the ‘Admonitio’ created by Rather was in independent circulation.

In any case, the copying of the ‘Admonitio’ in Munich Clm 6241 shows that the text was deemed valuable in late tenth-century Bavaria. In their study of the Old High German clerical oath, Stefan Esders and Heike Johanna Mierau argued that this Munich manuscript was put together as an episcopal handbook [66]. If this is right, then an edited version of the ‘Admonitio’ was considered as useful for a bishop in Bavaria as it had been for a bishop in the Po valley.

4. The ‘Admonitio’ and the liturgical tradition

Around the year 1000, a new phrase of the ‘Admonitio’’s history began, as it was integrated into new liturgical ordines for diocesan synods [67]. The most commonly copied of these ordines was ‘Ordo 14’. According to this ordo, the diocesan synod stretched over four days. On the first day of the synod the diocese’s priests were welcomed into the cathedral, and were asked whether they had any quarrels amongst themselves. The second and third days were mostly taken up with prayers and liturgies. On the fourth and final day, the bishop himself finally appeared in full vestments, and addressed the priests in person. The ‘Admonitio’ was copied at this point as a model for the address.

It was the insertion of the ‘Admonitio’ in synodal ordines which led to its wide dissemination in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. These ordines were a standard component in pontificals, manuscripts designed for bishops’ use [68]. The ordines were also sometimes copied into legal manuscripts, especially those of the canon law collection of Bishop Burchard of Worms, as has long been noticed [69]. Indeed the ‘Admonitio’ can be found in a liturgical context in one of the very earliest Burchard manuscripts, Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Pal. lat. 585, produced in Worms before 1023. The text appears in a liturgy for a diocesan synod known as ‘Ordo 17’, included at the beginning of the manuscript ( fols. 6r–9v ) [70]. In some Burchard manuscripts, the ‘Admonitio’ is copied as a standalone text, but in these cases too the text seems to be based on the version in the ordines [71].

It is sometimes assumed that liturgical development tends towards textual elaboration and extension. But when the ‘Admonitio’ was included into the liturgical tradition, it did so in a significantly shorter version than that of the tenth-century manuscripts discussed above. Almost all the surviving ordines that include the ‘Admonitio’ feature this shortened version, which in particular omits a set of final clauses; it was this omission which led Amiet to classify these clauses as an appendix [72]. The ‘long’ version of the ‘Admonitio’ present in the earliest manuscripts, and adapted by Rather of Verona, was by contrast only seldom copied after the tenth century [73]. It is tempting to see two Mainz manuscripts, Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 694 and Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Cod. Guelf 83.21 Aug 2, as representing stages in the truncation. As we have seen, the Vienna manuscript includes the ‘Admonitio’’s ‘appendix’, but it marks it out as a separate part of the text through rubrication and the insertion of a concluding clause ( figure 5 ). The Wolfenbüttel manuscript was also copied in Mainz around the year 1000, and, like the Vienna manuscript, is another copy of the revised version of Regino’s canon law collection. The ‘Admonitio’ is copied on fols. 2r–2v ( unfortunately the first leaf is missing ) [74]. But in this manuscript, unlike the Vienna codex, the so-called appendix is omitted. Perhaps this manuscript, or one like it, was the source for the liturgist composing the ordo.

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 694, fol. 3r

What does this compression of the ‘Admonitio’ in the ordines tell us about expectations of local priests? At first sight, it might seem to show a deliberate lowering of standards, as well as cutting clauses about the priest’s personal legal position ( Amiet clauses 83 and 84 ), the excisions removed various requirements. Priests were no longer explicitly requested to have access to, and to understand, various basic texts ( the Creed, the prayers of the Mass, the psalms: Amiet clauses 85–90 ), nor to know various specific liturgies ( Amiet clauses 91–95 ), nor be able to carry out basic computus ( Amiet clause 96 ), nor to own a martyrology and a penitential ( Amiet clause 97 ).

However, we should be cautious before reading these changes as straightforwardly indicating a decline in the educational expectations of local priests. It might be better to think of them as reflecting the altered function of the diocesan synod. More research on the early history of diocesan synods is needed, but it is clear that the diocesan synodal ordines in which the ‘Admonitio’ features differ quite substantially from the earlier diocesan synodal ordines that had circulated in Carolingian Francia. These older diocesan ordines had placed significant emphasis on testing and examining priests [75]. The newer ordines, which appear in manuscripts from around the year 1000 onwards, were more closely modelled on the arrangements for provincial synods, where bishops came together [76]. In these new ordines, the focus was less on ‘quality control’, and more on fostering consensus and on general moral exhortation ( a shift which might also help explain why fewer episcopal statutes were issued in this period ). For instance, in ‘Ordo 14’, God was asked to inspire the priests to lead their flock to eternal life, a reminder was issued about not living with women, and clerics were invited to raise any disputes they might have [77]. There was no explicit reference to assessing or monitoring priests’ levels of knowledge. It was in this liturgical context that the ‘Admonitio’ text was shortened to focus on sacramental competence, which, as Laudage pointed out, it now represented as the “chief duty of the priest.” [78]

Given this changing context, we cannot necessarily conclude from the abbreviation of the ‘Admonitio’ that priests’ knowledge no longer mattered, nor that the priests themselves were less well-educated. After all, education was one of the stated purposes for which Bishop Burchard had compiled his ‘Decretum’ in the early eleventh century, the testing of priests’ knowledge could have been reserved for local visitation, and anyway ordines are not a complete guide to what happened during synods [79]. Perhaps more centralised structures for the provision of clerical education within the diocese, as opposed to the somewhat ad hoc Carolingian arrangements which often relied on local monasteries, ensured that a basic standard of priestly education could now be assumed, making checking less urgent [80]. Nevertheless, it remains striking that when the ‘Admonitio’ was condensed in the early eleventh century for use in the diocesan synod, what now mattered was the correct performance of the Mass and the guarding of the priest’s local reputation. Priests might have been encouraged to go further, but they were considered to be fulfilling their role adequately if they mastered these core competencies, and this marks a noticeable shift in emphasis from Carolingian priorities [81].

Absorption into diocesan ordines also conferred greater rigidity upon the text. This was of course not an absolute rule. An early pontifical in the PRG tradition, Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana, D 5, possibly based on a copy made on the occasion of Emperor Henry II’s visit to Monte Cassino in 1022, contains a version of the ‘Admonitio’ which has been carefully annotated and emended, probably still in the eleventh century, in a Beneventan hand [82]. Some of the edits in the Vallicelliana manuscript suggest that they were comparing the text with a version in another manuscript. For instance, when priests are enjoined to exhort married men “to abstain from their wives at certain times” ( fol. 64v, Amiet clause 65 ), the correcting scribe elaborated on when this was: at Christmas, Lent, all feast days, Ember Day fasts, and Sunday nights. This is similar to an elaboration found in some other manuscripts of the ‘Admonitio Synodalis’, so here ( and perhaps at a couple of other places ) the scribe may have had one of these manuscripts on their desk.

But at other points in the text, the correcting scribe seems to have made emendations off their own bat. They specified that the sick should be offered the rite of reconciliation when “in fear of death” ( fol. 64r, Amiet clause 32 ). They allowed priests to sell property if they consulted the bishop first ( fol. 64v, Amiet clause 68 ). They emphasised that the bishops had been chosen or elected ( electi ) ( fol. 63v, Amiet clause 3 ). They emphasised that the Mass or eucharist should be taken with “great” fear ( Amiet clause 12 ). They crossed out a passage saying that churches should not be divided between many people ( Amiet clause 54 ). When the ‘Admonitio’ noted that some “unfaithful people” might steal the chrism, they noted curtly: “women” ( fol. 64v, Amiet clause 80 ), though the original scribe had already laid the way for this by writing the feminine quasdam instead of the male/indeterminate quosdam, deliberately or not [83]. And the annotator also noted that it was permitted for priests to drink in taverns if they were travelling ( fol. 64r, Amiet clause 39 ), as indeed some traditional canons permitted.

Eye-catching though these edits in the Vallicelliana manuscript are, they are mostly clarifications, rather than Rather’s more deliberate emendations. And the Vallicelliana edits were relatively unusual compared with the broader liturgical transmission. Naturally there were textual variations within the liturgical tradition, as one would expect in a text extensively copied over several centuries. But most of those variations conscientiously noted in Amiet’s edition are relatively trivial, and could well have sprung from copying errors: for instance the difference between videte and videamus, or vasa sacra and sacra vasa. These are potentially valuable clues from the point of view of a critical edition, but they are less important from the point of reception history, since they make little difference to the meaning. The liturgical tradition had a monumental quality to it [84]. Once the ‘Admonitio’ was integrated into this tradition, it froze, and ceased to be a living text.

5. Conclusion

As noted earlier, Amiet suggested that in the ‘Admonitio’, “one sees appear the eternal face of the holy Church.” This article has argued that the apparently unchanging nature of the text highlighted by Amiet was in part an illusion produced by Amiet’s own assumptions. In reality the text was changed and adapted in ways that have much to tell us about how local priests were perceived. The history of the ‘Admonitio’ has not yet given up all its secrets, but some preliminary conclusions are nevertheless possible.

The very earliest manuscripts of the ‘Admonitio Synodalis’, which are all legal compilations of one kind or another, suggest the text was initially read within a legal-pastoral context, much like the closely associated collection of canonical traditions selected from the mass of Carolingian material by Regino of Prüm in the early tenth century. Indeed the ‘Admonitio’ could be read as a condensed version of Regino’s work, summarised into a form for exhortation. For the most part the ‘Admonitio’ simply changes Regino’s questions into commands; at other times, the ‘Admonitio’ echoes some of Regino’s proof texts. The author seems to have been intimately familiar with Regino’s work. No wonder that in 1914 Robert Lawson wondered whether the author might not have been Regino himself, a suggestion which might be worth revisiting in the light of the manuscripts discussed above [85].

As we have seen, the ‘Admonitio’ proved valuable for Bishop Rather of Verona in the later tenth century. However, the prominence of the ‘Admonitio’ is really owed to its inclusion around the year 1000 in new liturgical ordines, transmitted in pontificals and in the collection of Burchard of Worms, which led to it eclipsing other comparable synodal admonitions. As part of that process of inclusion, the original ‘Admonitio’ was heavily edited down, cutting back on questions of technical knowledge to focus on morality and sacramental capacity. Only from this point did the ‘Admonitio’ become a fossilised text, which was seldom further tampered with. It had become part of the liturgy, something to be prized as part of a church’s heritage. It was this version that Amiet canonised in his edition as ‘the’ ‘Admonitio’.

What does this development tell us about the wider questions around expectations of priests in the long tenth century and beyond? Firstly we can see that these expectations were indeed indebted to Carolingian precedents, filtered through Regino of Prüm, making the ‘Admonitio’ a compilation from a compilation, as Lawson put it [86]. These expectations remained a useful summary in the tenth century, as is shown by Rather of Verona’s decision in 966 to circulate the ‘Admonitio’ in revised written form around the clergy of his diocese, rural as well as urban. However, Rather did not shrink from editing ( and re-editing ) the text to meet his needs and priorities. The Carolingian legacy was still live, so to speak.

But from the eleventh century, the text was truncated, and its evolution stopped. This truncation reflects the integration of the ‘Admonitio’ into the liturgy for a diocesan synod whose focus seems to have changed. This may not tell us all that much about the actual level of local priests’ competence. But it does at least imply a change in episcopal priorities. Ninth-century bishops had cared a great deal about the wider expertise of their local priests, and used diocesan synods to evaluate it. But in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, what mattered at the increasingly standardised diocesan synod was the performance of episcopal authority and the establishment of consensus, as the basis for establishing a diocesan community. Now, it was moral comportment and the Mass that was uppermost when bishops harangued their assembled rural clergy. In this revised liturgical setting, the ‘Admonitio’ did preserve certain Carolingian traditions about the role of the rural priest, but in a compressed, and ossified, form.

Appendix 1: tenth-century manuscripts of the ‘Admonitio’

Brussels, KBR, MS 495–505, fols. 1v–3v

Berlin, SB, Phill. 1676 ( Rather’s ‘Synodica’ ), fols. 7r–8v

Laon, BM, MS 274 ( Rather’s ‘Synodica’ ), fols. 58v–64v

Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, A 46 inf., fols. 158v–159v

Munich, BSB, Clm 6340 ( Rather’s ‘Synodica’ ), fols. 32v–39v

Munich, BSB, Clm 6241 ( linked to Rather’s ‘Synodica’ ), fols. 96r–99r

Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac, MS 1979, fols. 160r–162v

Wolfenbüttel, HAB, Guelf 83.21 Aug 2, fols. 2r–2v

Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 694, fols. 1v–3v

Appendix 2: edition of the ‘Admonitio’ in Brussels KBR 495–505

In the light of the problems identified with Amiet’s edition, and the evidence of the tenth-century manuscripts presented above, a new critical edition of the ‘Admonitio’ is needed. To provide one exceeds the scope of this article. However, as a contribution towards such a critical edition, this appendix presents an edition of the ‘Admonitio’ text in the Brussels KBR 495–505 manuscript, which has never been edited before. Significant variations vis-à-vis the related manuscripts Vienna ÖNB cod. 694 ( V ), Milan Biblioteca Ambrosiana A 46 inf. ( M ), Troyes Médiathèque Jacques-Chirac MS 1979 ( T ) and Wolfenbüttel, HAB, Cod. Guelf. 83.21 Aug 2° ( W ) are indicated in the apparatus [87]. It may be noted that M and T, and V and W, share certain readings.

I have renumbered the clauses, while also providing Amiet’s original numeration in an extra column on the right since this is standard in the scholarship. In this column I have also provided an indication of the likely source for each clause in Regino’s ‘Libri Duo’, drawing on Lotter’s identifications; references to ‘Inq I’ are to the first set of Regino’s inquisition questions, ‘Inq II’ to the second, and references in Roman numerals alone are to Regino’s proof canons [88]. To aid the reader, I have expanded abbreviations ( including the e-caudata ), modernised punctuation, capitalised names, and normalised u/v spellings.

© 2023 bei den Autoren, publiziert von De Gruyter.

Dieses Werk ist lizensiert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung - Nicht-kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitung 4.0 International Lizenz.

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- The pauperes in the ‘Libri Historiarum’ of Gregory of Tours

- Neue Forschungen zu Glashandwerkern unter den Karolingern und ihren Nachfolgern ( 8. bis 10. Jahrhundert )

- Störende Statuen?

- Contesting Religious Truth

- Wirtschaftssanktionen im 13. Jahrhundert

- Wer die worheit gerne mynn / Und sich güter dinge versynn, / Der müsz der besten einre sin

- Petrus Berchorius bei den Dunkelmännern

- Einheit in der Vielfalt – Vielfalt in der Einheit? Unity in Diversity – Diversity in Unity? Rudolf Hercher(’)s Epistolographi Graeci

- Einheit in der Vielfalt – Vielfalt in der Einheit?

- Philostrats ,Briefe‘ – Einheit in der Vielfalt, Vielfalt in der Einheit?

- From Letter Collections to Letter Writing Manuals

- Phalaris & co.

- New and Old Letter Types in the Corpus of Julian the Apostate ( 361–363 )

- Zur Zusammenstellung der Handschriften der ‚Epistula ad Ammaeum II‘ des Dionysios von Halikarnass

- Dionysios von Antiocheia und das Schicksal einer spätantiken Briefsammlung

- Priests in a Post-Imperial World, c. 900–1050

- Introduction

- Local Priests and their Siblings c. 900–c. 1100

- Tithes in the Long 10th Century

- Bishops, Priests and Ecclesiastical Discipline in Tenth and Eleventh-Century Lotharingia

- The Earliest Form and Function of the ‘Admonitio synodalis’ *

- Orts-, Personen- und Sachregister

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- The pauperes in the ‘Libri Historiarum’ of Gregory of Tours

- Neue Forschungen zu Glashandwerkern unter den Karolingern und ihren Nachfolgern ( 8. bis 10. Jahrhundert )

- Störende Statuen?

- Contesting Religious Truth

- Wirtschaftssanktionen im 13. Jahrhundert

- Wer die worheit gerne mynn / Und sich güter dinge versynn, / Der müsz der besten einre sin

- Petrus Berchorius bei den Dunkelmännern

- Einheit in der Vielfalt – Vielfalt in der Einheit? Unity in Diversity – Diversity in Unity? Rudolf Hercher(’)s Epistolographi Graeci

- Einheit in der Vielfalt – Vielfalt in der Einheit?

- Philostrats ,Briefe‘ – Einheit in der Vielfalt, Vielfalt in der Einheit?

- From Letter Collections to Letter Writing Manuals

- Phalaris & co.

- New and Old Letter Types in the Corpus of Julian the Apostate ( 361–363 )

- Zur Zusammenstellung der Handschriften der ‚Epistula ad Ammaeum II‘ des Dionysios von Halikarnass

- Dionysios von Antiocheia und das Schicksal einer spätantiken Briefsammlung

- Priests in a Post-Imperial World, c. 900–1050

- Introduction

- Local Priests and their Siblings c. 900–c. 1100

- Tithes in the Long 10th Century

- Bishops, Priests and Ecclesiastical Discipline in Tenth and Eleventh-Century Lotharingia

- The Earliest Form and Function of the ‘Admonitio synodalis’ *

- Orts-, Personen- und Sachregister