A new invasive pest in Mexico: the presence of Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in chili pepper fields

-

María A. Payán-Arzapalo

, Francisco Infante

, José A. Ortiz

Abstract

The southeast Asian thrips, Thrips parvispinus (Karny) (Thysanoptera Thripidae), one of the most invasive pests worldwide, is here recorded from Mexico for the first time damaging chilli pepper plants. Native to Asia, this species has spread throughout more than 30 countries across all continents (except South America). In the Americas, this thysanopteran had been accidentally introduced to the US, Canada and Puerto Rico, only. The discovery of this noxious organism in Mexico is unfortunate for national agriculture, as the insect feeds on around 45 species of plants, reducing agricultural yields and causing severe economic losses.

Resumen

El trips del sureste de Asia, Thrips parvispinus (Karny) (Thysanoptera Thripidae), una de las plagas más invasivas en el mundo, es reportado en México por primera vez, dañando plantas de chile. Originaria de Asia, esta especie se ha diseminado a más de 30 países en todos los continentes (excepto Sudamérica). En el Continente Americano, este tisanóptero había sido accidentalmente introducido a los Estados Unidos, Canadá y Puerto Rico, solamente. El descubrimiento de este organismo nocivo en México es una lamentable noticia para la agricultura nacional, debido a que el insecto se alimenta de aproximadamente 45 especies de plantas, reduciendo los rendimientos agrícolas y causando severas pérdidas económicas.

Invasion of exotic species is among the most important problems in ecosystems (Lake and Leishman 2004). At a global scale, biological invasions are multi-causal events that are mainly favored by anthropogenic activities, such as, international trade, mass transportation, tourism, and ecosystem overexploitation (Gulzar et al. 2024; Rodríguez-Labajos et al. 2009; Street et al. 2023). Since 1970, more than 37,000 exotic species have been introduced into regions and biomes worldwide (IPBES 2023). Although invasiveness can also be a natural process, the recent enhanced rate of invasions is clearly a human-driven phenomenon (Gurevitch and Padilla 2004). Alongside the adverse impact on the ecosystem function, exotic species that feed on cultivated plants have the potential to be more dangerous than in their original habitats, mainly due to the plentiful food and the absence of natural enemies, causing severe damage to crops (Mooney and Cleland 2001; Pimentel et al. 2000). Economic damages associated with invasive exotic species have been estimated at more than US$423 billion annually (IPBES 2023).

Insects are the most common and damaging group of terrestrial animal invaders (Gippet et al. 2019). Species in the order Thysanoptera have been considered successful invaders as they pass almost unnoticed due to their small size and cryptic habits (Morse and Hoddle 2006). Thrips are usually detected in agroecosystems after the damage to cultivated plants is evident, and by then, the species have already become established in the new environment. In the case of Mexico, several invasive phytophagous species of thrips have been accidentally introduced in recent times. Examples include the banana thrips Chaetanaphothrips signipennis (Bagnall), the western flower thrips Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande), the greenhouse thrips Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis (Bouché), the bean flower thrips Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagnall), the chili thrips Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood, the melon thrips Thrips palmi Karny, the gladiolus thrips Thrips simplex (Morison), and the onion thrips Thrips tabaci Lindeman (Cambero-Campos et al. 2022; Goldarazena et al. 2014; Ortiz et al. 2020). This paper aims to document the first occurrence of Thrips parvispinus (Karny) in Mexico and provide a general illustrated description that will help in its identification and monitoring.

Described from specimens collected in Thailand, T. parvispinus is believed to be native to South Asia (Ahmed et al. 2024). This is a pest thrips of quarantine importance that, in recent years, has spread throughout more than 30 countries across all continents (except South America) (Ahmed et al. 2024; EPPO 2024; Mound and Collins 2000). It is highly phytophagous, feeding on approximately 45 plant species, chili peppers being its main host. Due to the damage that T. parvispinus can cause to commercial crops and ornamental plants, it is considered a pest of great economic importance (Ahmed et al. 2024; Gleason et al. 2023). If T. parvispinus becomes established in Mexico, it will be an important limiting factor for the production of numerous crops.

While performing a routine entomological inspection in a commercial chili bell pepper field (Capsicum annum L.; Solanaceae), we noticed the presence of an unusual specimen of Thysanoptera. This led to additional samplings to identify the thrips species. Samples of thrips were obtained from a pepper field in November 2024 from an undisclosed location in the municipality of Navolato, Sinaloa, Mexico (24.7655556 °N, 107.7019444 °W; 10 m. a.s.l.). Thrips were collected at random from approximately one-hectare by zigzag sampling. Pepper leaves and flowers of approximately 50 plants were shaken against a plastic tray to detach insects. Using a camel-hair brush thrips were placed in vials with 70 % ethanol and taken to the laboratory. Once there, adult thrips were mounted on slides using Hoyer’s medium. A total of 34 specimens (29 females and five males) of the species T. parvispinus were recovered from samples, confirming its presence in Mexico for the first time. Five voucher specimens were deposited at the entomological collection of El Colegio de la Frontera Sur in Tapachula, Chiapas, where they are available upon request (Accession numbers ECO-TAP-E L21 to L25).

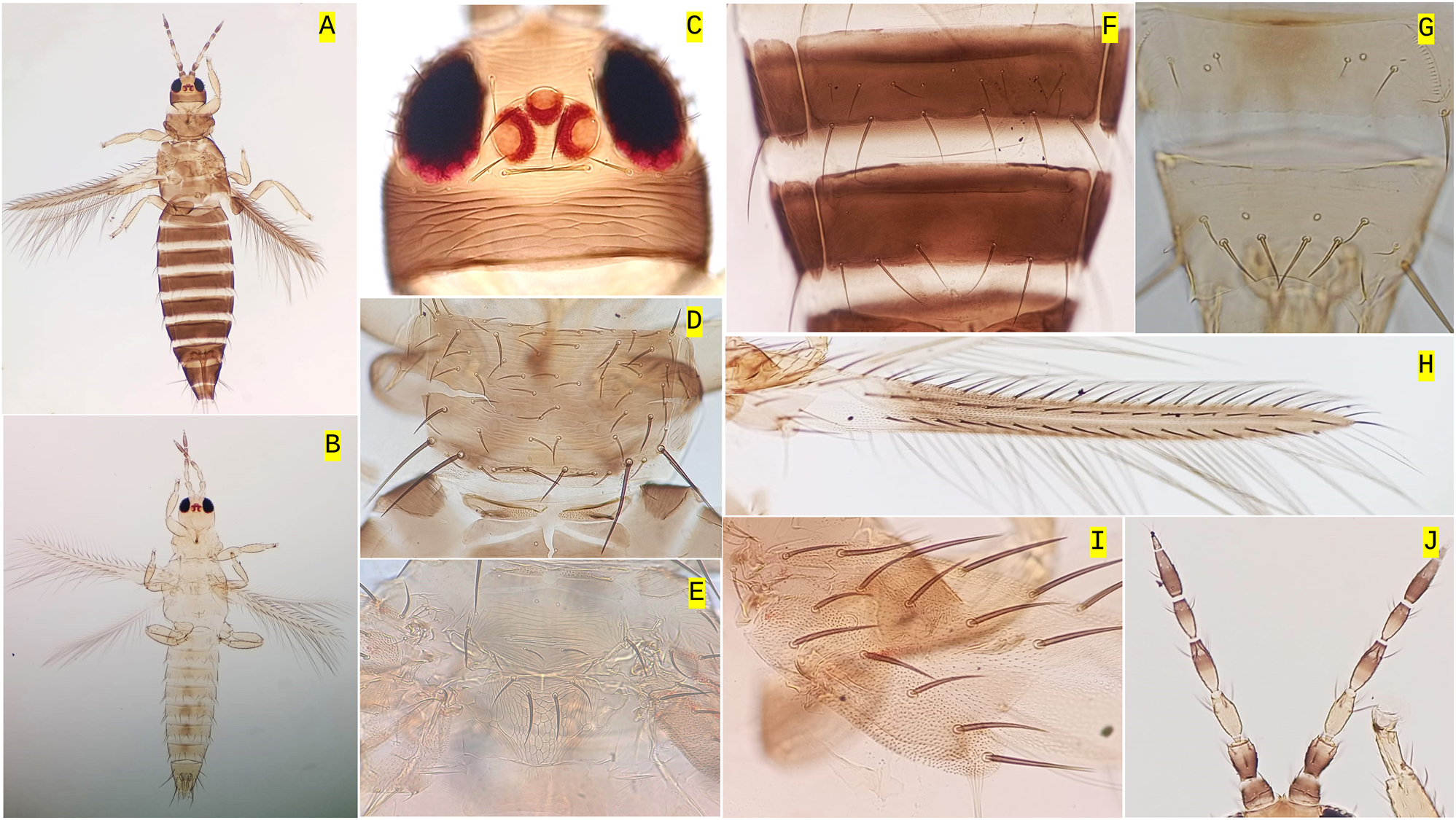

The female is dark brown with yellow legs and paler head in the midline (Figure 1). Head broader than long. Antennae seven segmented; segment III and the basal half of IV and V, pale. Ocellar setae pair III small and arising from the anterior margins of the triangle. Postocular setae I and III slightly longer than ocellar setae III; ocellar pair II minute. Fore wing brown with a pale base; first and second vein with continuous row of setae. Pronotum with two pairs of long posteroangular setae; posterior margin with three pairs of setae. Clavus with five marginal setae; terminal seta longer than sub-terminal seta. Metanotum with polygonal reticulate sculpturing; median setae long and near the anterior margin; campaniform sensilla absent. Tergite II with three lateral marginal setae; tergite VIII with posteromarginal comb absent or represented by few small microtrichia laterally. Sternites III to VI with about six to 12 discal setae in an irregular row; II and VII with no discal setae. The male is yellow and smaller than the female. Sternites III to VI have a small transverse pore plate, while discal setae arise laterally. Posterior margin of tergite VIII without comb (Mound and Collins 2000; Mound and Tree 2020).

Thrips parvispinus (Karny): (A) female and (B) male habitus; (C) head; (D) pronotum; (E) metanotum; (F) sternites VI and VII; (G) male tergites; (H) fore wing; (I) clavus; and (J) antennal segments.

Adults and larvae of T. parvispinus were observed feeding on leaves, flowers and small fruits of chili bell pepper (Figure 2). When feeding on fresh leaves, most individuals of T. parvispinus were on the abaxial leaf surface, producing leaf deformation. Because of the presence of thrips larvae, we infer that this thysanopteran was breeding on the pepper plants.

Chili pepper plants infested by Thrips parvispinus under field conditions: (A) leaves seriously damaged by thrips; (B) thrips adults inside a chili flower; (C) a damaged fruit with the typical thrips scarring; and (D) adults and larvae of T. parvispinus feeding on the abaxial leaf surface.

Our paper is the first record of T. parvispinus in Latin America and the fourth in the Americas, after the US (Ahmed et al. 2024), Canada (Gleason et al. 2023), and Puerto Rico (Martínez-Cález 2023). Based on the closeness between the US and Mexico, we believe that the invasion of T. parvispinus was probably caused by infested material from that country. The entrance into Mexico of this noxious thysanopteran occurred despite the rigid plant protection protocols of the Mexican government to restrain exotic pests. In general, the phytosanitary measures of Mexico seem to be effective in this matter as the number of exotic introductions (approximately 800 species in all taxa) are lower than in other countries (Espinosa-García and Villaseñor 2017), despite the geographic position of the country, the high volume of commercial trade, and human mobility to and from the US, the Caribbean, and Central American countries. Although the discovery of T. parvispinus in Mexico is unfortunate for national agriculture, the present paper will be valuable from a pest control perspective. Accurately identifying invasive organisms is the first step for appropriate diagnostic and pest management strategies. For instance, it is well known that different thrips species that cohabit in the same crop differ in their visual attraction to color sticky traps, and this could have important implications for trapping efficiency (Carrillo-Arámbula et al. 2022). Likewise, the susceptibility of thrips to insecticides is variable among species (Warpechowski et al. 2024). In this sense, only precise and specific information on T. parvispinus, will be helpful for decision-makers to select the best pest management choices.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Laurence Mound for giving valuable comments that helped to improve the manuscript. Hoger Weissenberger help to improve the quality of figures.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: F. Infante wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised and provided feedback. All authors have approved the submission and accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None to declare.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None to declare.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Ahmed, M.Z., Roberts, J.W., Soto-Adames, F.N., McKenzie, C.L., and Osborne, L.S. (2024). Global invasion of Thrips parvispinus (Karny) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) across three continents associated with its one haplotype. J. Appl. Entomol. 149: 237–247, https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.13376.Suche in Google Scholar

Cambero-Campos, O.J., Cambero-Monroy, A., Rodríguez-Arrieta, J.A., Robles-Bermúdez, A., Lemus-Soriano, B.A., Ríos-Velasco, C., Zamora-Landa, A.I., and Estrada-Virgen, M.O. (2022). New report of the exotic species Megalurothrips usitatus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) infesting three commercial legumes in Nayarit, Mexico. Fla. Entomol. 105: 316–318, https://doi.org/10.1653/024.105.0409.Suche in Google Scholar

Carrillo-Arámbula, L., Infante, F., Cavalleri, A., Gómez, J., Ortiz, J.A., Fanson, B.G., and Gonzalez, F.J. (2022). Colored sticky traps for monitoring phytophagous thrips (Thysanoptera) in mango agroecosystems, and their impact on beneficial insects. PLoS ONE 17: e0276865, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276865.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

EPPO [European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization] (2024). Global Database. Thrips parvispinus (THRIPV) Distribution 2024, https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/THRIPV/distribution (Accessed 04 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Espinosa-García, F.J. and Villaseñor, J.L. (2017). Biodiversity, distribution, ecology and management of non-native weeds in Mexico: a review. Rev. Mex. Biod. 88: 76–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2017.10.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Gippet, J.M.W., Liebhold, A.M., Fenn-Moltu, G., and Bertelsmeier, G. (2019). Human-mediated dispersal in insects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 35: 96–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2019.07.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Gleason, J.E., Maw, E., Summerfield, A., Jandricic, S.E., and Brunet, B.M.T. (2023). Firsts records of invasive agricultural pests Thrips parvispinus (Karny, 1922) and Thrips setosus Moulton, 1928 (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in Canada. J. Entomol. Soc. Ontario 154: 1–12, https://journal.lib.uoguelph.ca/index.php/eso/article/view/7528.Suche in Google Scholar

Goldarazena, A., Infante, F., and Ortiz, J.A. (2014). A preliminary assessment of thrips inhabiting a tropical montane cloud forest of Chiapas, Mexico. Fla. Entomol. 97: 590–596, https://doi.org/10.1653/024.097.0234.Suche in Google Scholar

Gulzar, R., Ahmad, R., Hassan, T., Rashid, I., and Khuroo, A.A. (2024). Environmental and anthropogenic drivers of invasive plant diversity and distribution in the Himalaya. Ecol. Inform. 81: 102586, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102586.Suche in Google Scholar

Gurevitch, J. and Padilla, D.K. (2004). Are invasive species a major cause of extinctions? Trends Ecol. Evol. 19: 470–474, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

IPBES [Intergovernmental Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services] (2023). Invasive alien species report, https://www.unep.org/resources/report/invasive-alien-species-report (Accessed 04 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Lake, J.C. and Leishman, M.R. (2004). Invasion success of exotic plants in natural ecosystems: the role of disturbance, plant attributes and freedom from herbivores. Biol. Conserv. 117: 215–226, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00294-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Martínez-Cález, E.L. (2023). Alerta de plaga, Thrips parvispinus (Karny). Servicio de Extensión Agrícola de Puerto Rico, Available at: https://www.uprm.edu/sea/wp-content/uploads/sites/351/2023/12/Alerta-Plaga-Thrips-parvispinus-v.final-2.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Mooney, H.A. and Cleland, E.E. (2001). The evolutionary impact of invasive species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98: 5446–5451, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.091093398.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Morse, J.G. and Hoddle, M.S. (2006). Invasion biology of thrips. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 51: 67–89, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151044.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Mound, L.A. and Collins, D.W. (2000). A South East Asian pest species newly recorded from Europe: Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), its confused identity and potential quarantine significance. J. Eur. Entomol. 97: 197–200, https://doi.org/10.14411/eje.2000.037.Suche in Google Scholar

Mound, L.A. and Tree, D.J. (2020). Thysanoptera Australiensis – Thrips of Australia. Lucidcentral.org. Identic Pty Ltd, Queensland, Australia, https://keys.lucidcentral.org/keys/v3/thrips_australia/keys/Thripinae_Australia/key/austhripinae/Media/Html/Entities/thrips_parvispinus.htm (Accessed 02 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Ortiz, J.A., Infante, F., Rodriguez, D., and Toledo-Hernández, R.A. (2020). Discovery of Scirtothrips dorsalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in blueberry fields of Michoacan, Mexico. Fla. Entomol. 103: 408–410, https://doi.org/10.1653/024.103.0316.Suche in Google Scholar

Pimentel, D., Lach, L., Zuniga, R., and Morrison, D. (2000). Environmental and economic costs of non-indigenous species in the United States. Bioscience 50: 53–65, https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0053:EAECON]2.3.CO;2.10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0053:EAECON]2.3.CO;2Suche in Google Scholar

Rodríguez-Labajos, B., Binimelis, R., and Monterroso, I. (2009). Multi-level driving forces of biological invasions. Ecol. Econ. 69: 63–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.08.022.Suche in Google Scholar

Street, S.E., Gutiérrez, J.S., Allen, W.L., and Capellini, I. (2023). Human activities favour prolific life histories in both traded and introduced vertebrates. Nat. Commun. 14: 262, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35765-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Warpechowski, L.F., Steinhaus, E.A., Moreira, R.P., Godoy, N.D., Preto, V.E., Braga, L.E., Wendt, A.F., Reis, A.C., Lima, E.F.B., Farias, J.R., et al.. (2024). Why does identification matter? Thrips species (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) found in soybean in southern Brazil show great geographical and interspecific variation in susceptibility to insecticides. Crop Prot. 178: 106592, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2024.106592.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Florida Entomological Society

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Life history descriptions of two aquatic Florida moth species (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Higher Apoidea activity on centipedegrass lawns than on dicotyledonous plants

- Dynamics of citrus pest populations following a major freeze in northern Florida

- Control of Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae) by trapping with banana vinegar

- Establishment, distribution, and preliminary phenological trends of a new planthopper in the genus Patara (Hemiptera: Derbidae) in South Florida, United States of America

- Comparative evaluation of the infestation of five varieties of citrus by the larvae of Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae)

- Impact of land use on the density of Bulimulus bonariensis (Stylommatophora: Bulimulidae) and its parasitic mite, Austreynetes sp. (Trombidiformes: Ereynetidae)

- First record of native seed beetle Stator limbatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on invasive earleaf acacia in Florida

- Establishment and monitoring of a sentinel garden of Asian tree species in Florida to assess potential insect pest risks

- Parasitism of Halyomorpha halys and Nezara viridula (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) sentinel eggs in Central Florida

- Genetic differentiation of three populations of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in Mexico

- Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) associated with blueberry cultivation in Central Mexico

- First report of Phidotricha erigens (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Epipaschiinae) injuring mango inflorescences in Puerto Rico

- Seed predation of Sabal palmetto, Sabal mexicana and Sabal uresana (Arecaceae) by the bruchid Caryobruchus gleditsiae (Coleoptera: Bruchidae), with new host and distribution records

- Genetic variation of rice stink bugs, Oebalus spp. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) from Southeastern United States and Cuba

- Selecting Coriandrum sativum (Apiaceae) varieties to promote conservation biological control of crop pests in south Florida

- First record of Mymarommatidae (Hymenoptera) from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador

- First field validation of Ontsira mellipes (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) as a potential biological control agent for Anoplophora glabripennis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in South Carolina

- Field evaluation of α-copaene enriched natural oil lure for detection of male Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in area-wide monitoring programs: results from Tunisia, Costa Rica and Hawaii

- Abundance of Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagnall) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and other thrips in commercial snap bean fields in the Homestead Agricultural Area (HAA)

- Performance of Salvinia molesta (Salviniae: Salviniaceae) and its biological control agent Cyrtobagous salviniae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in freshwater and saline environments

- Natural arsenal of Magnolia sarcotesta: insecticidal activity against the leaf-cutting ant Atta mexicana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

- Ethanol concentration can influence the outcomes of insecticide evaluation of ambrosia beetle attacks using wood bolts

- Post-release support of host range predictions for two Lygodium microphyllum biological control agents

- Missing jewels: the decline of a wood-nesting forest bee, Augochlora pura (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), in northern Georgia

- Biological response of Rhopalosiphum padi and Sipha flava (Hemiptera: Aphididae) changes over generations

- Argopistes tsekooni (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a new natural enemy of Chinese privet in North America: identification, establishment, and host range

- A non-overwintering urban population of the African fig fly (Diptera: Drosophilidae) impacts the reproductive output of locally adapted fruit flies

- Fitness of Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) on four economically important host fruits from Fujian Province, China

- Carambola fruit fly in Brazil: new host and first record of associated parasitoids

- Establishment and range expansion of invasive Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Phycitinae) in Texas

- A micro-anatomical investigation of dark and light-adapted eyes of Chilades pandava (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)

- Scientific Notes

- Evaluation of food attractants based on fig fruit for field capture of the black fig fly, Silba adipata (Diptera: Lonchaeidae)

- Exploring the potential of Amblyseius largoensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a biological control agent against Aceria litchii (Acari: Eriophyidae) on lychee plants

- Early stragglers of periodical cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) found in Louisiana

- Attraction of released male Mediterranean fruit flies to trimedlure and an α-copaene-containing natural oil: effects of lure age and distance

- Co-infestation with Drosophila suzukii and Zaprionus indianus (Diptera: Drosophilidae): a threat for berry crops in Morelos, Mexico

- Observation of brood size and altricial development in Centruroides hentzi (Arachnida: Buthidae) in Florida, USA

- New quarantine cold treatment for medfly Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in pomegranates

- A new invasive pest in Mexico: the presence of Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in chili pepper fields

- Acceptance of fire ant baits by nontarget ants in Florida and California

- Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

- Note on the nesting biology of Epimelissodes aegis LaBerge (Hymenoptera: Apidae)

- Mass rearing protocol and density trials of Lilioceris egena (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a biological control agent of air potato

- Cardinal predation of the invasive Jorō spider Trichophila clavata (Araneae: Nephilidae) in Georgia

- Book Reviews

- Review: Harbach, R.E. 2024. The Composition and Nature of the Culicidae (Mosquitoes). Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International and the Royal Entomological Society, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781800627994

- Retraction

- Retraction of: Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Life history descriptions of two aquatic Florida moth species (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Higher Apoidea activity on centipedegrass lawns than on dicotyledonous plants

- Dynamics of citrus pest populations following a major freeze in northern Florida

- Control of Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae) by trapping with banana vinegar

- Establishment, distribution, and preliminary phenological trends of a new planthopper in the genus Patara (Hemiptera: Derbidae) in South Florida, United States of America

- Comparative evaluation of the infestation of five varieties of citrus by the larvae of Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae)

- Impact of land use on the density of Bulimulus bonariensis (Stylommatophora: Bulimulidae) and its parasitic mite, Austreynetes sp. (Trombidiformes: Ereynetidae)

- First record of native seed beetle Stator limbatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on invasive earleaf acacia in Florida

- Establishment and monitoring of a sentinel garden of Asian tree species in Florida to assess potential insect pest risks

- Parasitism of Halyomorpha halys and Nezara viridula (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) sentinel eggs in Central Florida

- Genetic differentiation of three populations of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in Mexico

- Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) associated with blueberry cultivation in Central Mexico

- First report of Phidotricha erigens (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Epipaschiinae) injuring mango inflorescences in Puerto Rico

- Seed predation of Sabal palmetto, Sabal mexicana and Sabal uresana (Arecaceae) by the bruchid Caryobruchus gleditsiae (Coleoptera: Bruchidae), with new host and distribution records

- Genetic variation of rice stink bugs, Oebalus spp. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) from Southeastern United States and Cuba

- Selecting Coriandrum sativum (Apiaceae) varieties to promote conservation biological control of crop pests in south Florida

- First record of Mymarommatidae (Hymenoptera) from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador

- First field validation of Ontsira mellipes (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) as a potential biological control agent for Anoplophora glabripennis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in South Carolina

- Field evaluation of α-copaene enriched natural oil lure for detection of male Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in area-wide monitoring programs: results from Tunisia, Costa Rica and Hawaii

- Abundance of Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagnall) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and other thrips in commercial snap bean fields in the Homestead Agricultural Area (HAA)

- Performance of Salvinia molesta (Salviniae: Salviniaceae) and its biological control agent Cyrtobagous salviniae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in freshwater and saline environments

- Natural arsenal of Magnolia sarcotesta: insecticidal activity against the leaf-cutting ant Atta mexicana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

- Ethanol concentration can influence the outcomes of insecticide evaluation of ambrosia beetle attacks using wood bolts

- Post-release support of host range predictions for two Lygodium microphyllum biological control agents

- Missing jewels: the decline of a wood-nesting forest bee, Augochlora pura (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), in northern Georgia

- Biological response of Rhopalosiphum padi and Sipha flava (Hemiptera: Aphididae) changes over generations

- Argopistes tsekooni (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a new natural enemy of Chinese privet in North America: identification, establishment, and host range

- A non-overwintering urban population of the African fig fly (Diptera: Drosophilidae) impacts the reproductive output of locally adapted fruit flies

- Fitness of Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) on four economically important host fruits from Fujian Province, China

- Carambola fruit fly in Brazil: new host and first record of associated parasitoids

- Establishment and range expansion of invasive Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Phycitinae) in Texas

- A micro-anatomical investigation of dark and light-adapted eyes of Chilades pandava (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)

- Scientific Notes

- Evaluation of food attractants based on fig fruit for field capture of the black fig fly, Silba adipata (Diptera: Lonchaeidae)

- Exploring the potential of Amblyseius largoensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a biological control agent against Aceria litchii (Acari: Eriophyidae) on lychee plants

- Early stragglers of periodical cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) found in Louisiana

- Attraction of released male Mediterranean fruit flies to trimedlure and an α-copaene-containing natural oil: effects of lure age and distance

- Co-infestation with Drosophila suzukii and Zaprionus indianus (Diptera: Drosophilidae): a threat for berry crops in Morelos, Mexico

- Observation of brood size and altricial development in Centruroides hentzi (Arachnida: Buthidae) in Florida, USA

- New quarantine cold treatment for medfly Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in pomegranates

- A new invasive pest in Mexico: the presence of Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in chili pepper fields

- Acceptance of fire ant baits by nontarget ants in Florida and California

- Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

- Note on the nesting biology of Epimelissodes aegis LaBerge (Hymenoptera: Apidae)

- Mass rearing protocol and density trials of Lilioceris egena (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a biological control agent of air potato

- Cardinal predation of the invasive Jorō spider Trichophila clavata (Araneae: Nephilidae) in Georgia

- Book Reviews

- Review: Harbach, R.E. 2024. The Composition and Nature of the Culicidae (Mosquitoes). Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International and the Royal Entomological Society, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781800627994

- Retraction

- Retraction of: Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)