Abstract

Butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) include approximately 157,500 described species, the majority of which have terrestrial larvae. However, several lepidopteran lineages have successfully evolved strategies and adaptations to live under, or near, water. It is estimated that among the currently described Lepidoptera, only about 5 % of the species are truly aquatic. Aquatic and semi-aquatic moths display a large variation in life history, which can include stem boring, case making, and free-living on plants. Despite their unique adaptations, the life histories of many aquatic and semi-aquatic lepidopterans remain largely unknown. In the present study, we have documented the life history of two crambid moth species, the waterlily leafcutter moth (Elophila obliteralis Walker) and the salvinia stem-borer moth (Samea multiplicalis (Guenée)) from the southern United States, specifically reporting development times and describing in detail their behavioral adaptations through high quality images. We also characterize and image their silk, an important adaptation to living in an aquatic environment.

Resumen

Las mariposas y polillas (Lepidoptera) incluyen aproximadamente 157,500 especies descritas, la mayoría de las cuales tienen larvas terrestres. Sin embargo, varias líneas evolutivas de lepidópteros han desarrollado con exito estrategias y adaptaciones para vivir bajo el agua o en su cercania. Se estima que entre los lepidópteros descritos actualmente, solo alrededor del 5 % de las especies son verdaderamente acuáticas. Las polillas acuáticas y semiacuáticas presentan una gran variación en sus historias de vida, que pueden incluir el barrenar tallos, construir sacos y vivir libremente sobre las plantas. A pesar de sus adaptaciones únicas, la historia de vida de muchos lepidópteros acuáticos y semiacuáticos sigue siendo en gran parte desconocida. En este estudio, documentamos la historia de vida de dos especies de Crambidae, la Elophila obliteralis Walker y la Samea multiplicalis (Guenée) del sur de los Estados Unidos, informando específicamente sobre los tiempos de desarrollo y describiendo en detalle sus adaptaciones de comportamiento a través de imágenes de alta calidad. También caracterizamos y presentamos imágenes de su seda, una adaptación importante para vivir en un entorno acuático.

1 Introduction

Butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) include approximately 157,500 described species (Mitter et al. 2017), most of which have terrestrial larvae. They are well adapted to the terrestrial environment, with adaptations such as adult flight, pollination, and breathing air. However, several lepidopteran lineages have successfully evolved ecological strategies to live an aquatic or semi-aquatic life in their immature stages. It is estimated that approximately 5 % of the currently described Lepidoptera species are truly aquatic (Pabis 2018), having at least one life stage that occurs under water. An even greater number of species have a looser association with aquatic environments; for instance, they may feed on aquatic plants without being submerged themselves or live in flood zones. Lepidoptera families with underwater stages include, but are not limited to, Cosmopterigidae, Crambidae, Erebidae, Noctuidae and Pyralidae (Adis 1983; Solis 2019). Aquatic and semi-aquatic moths display a large variation in life history, including stem boring, case making, and free living on plants (Lange 1956; Solis 2019).

The majority of truly aquatic species are found in the Crambidae. The crambid subfamily Acentropinae includes 800 described species (Mitter et al. 2017), nearly all of which are aquatic as larvae (Pabis 2018; Solis 2019). Nevertheless, details on how they have adapted to the aquatic environment remain largely unknown. Some aquatic and semi-aquatic species also are found in other, largely terrestrial crambid subfamilies such as the Pyraustinae (Solis 2019). Two crambid species, the aquatic waterlily leafcutter (Elophila obliteralis Walker, Acentropinae) and the semi-aquatic salvinia stem borer (Samea multiplicalis (Guenée), Spilomelinae) co-occur commonly in ponds and other slow-moving natural water environments in the southeastern United States (e.g., Center et al. 2002a; Tewari and Johnson 2011). Even though both species have been studied as potential biological control agents for invasive aquatic plants, our understanding of their life history, particularly their silk use, in the context of their aquatic lifestyle is limited.

Elophila Hübner is a highly polyphagous genus and is one of the only genera of aquatic Pyraloidea found on all continents except Antarctica (Mey and Speidel 2008). E. obliteralis is native to North America with a broad distribution in the eastern and midwestern United States and Canada (Habeck et al. 2021). Over the last century, this species also has been introduced to Hawaii, the UK (Habeck et al. 2021) and South Africa (Agassiz 2012), while potential records from India need confirmation (Sarkar 2022; Sen et al. 2019). It exhibits a fully aquatic lifestyle as a caterpillar and has been reported to feed on more than 50 aquatic plant species (Table 1 and references therein). Eggs are deposited underwater on the abaxial side of the host plant leaf in small ribbons (Dyar 1906), and caterpillars are generally submerged within proximity of the water surface. Soon after hatching, caterpillars generate an enclosure by chewing off a leaf fragment from their host plant and attaching it to the abaxial side of a leaf. This enclosure is used as shelter during the early stages of their lives (Dyar 1906; Gill et al. 2008). As they grow, caterpillars eventually generate a free-floating case, often consisting of two equally sized oval host plant pieces (Dyar 1906), which has led some to nickname this species “the sandwich man” (Habeck et al. 2021). E. obliteralis has been used as a biological control agent for invasive aquatic plants (e.g., Habeck et al. 2021; Tomasko et al. 2022) and can occasionally cause significant damage to ornamental plants, such as water lilies (Habeck et al. 2021).

List of host plants of Samea multiplicalis and Elophila obliteralis, including relevant citations.

| Plant family | Host plant | Samea multiplicalis | Elophila obliteralis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Hygrophila sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Alismataceae | Echinodorus sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Alismataceae | Sagittaria sp. | Center et al. (2002b) | |

| Amaranthaceae | Amaranthus sp. | Center et al. (2002b) | |

| Aponogetonaceae | Aponogeton sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Araceae | Orontium sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Araceae | Pistia stratiotes | Knopf and Habeck (1976) | Dray et al. (1993) |

| Araceae | Spirodela sp. | Tipping et al. (2009) | |

| Araliaceae | Hydrocotyle sp. | Center et al. (2002b) | |

| Brassicaceae | Cardamine sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Brassicaceae | Nasturtium sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Cabombaceae | Brasenia schreberi | Herlong (1979) | |

| Commelinaceae | Commelina tuberosa | DeLoach et al. (1979) | |

| Cyperaceae | Eleocharis sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Haloragaceae | Myriophyllum sp. | Center et al. (2002b) | |

| Hydrocharitaceae | Elodea sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Hydrocharitaceae | Hydrilla sp. | Center et al. (2002b) | |

| Hydrocharitaceae | Limnobium sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Lamiaceae | Mentha × piperita | Les (2017) | |

| Lamiaceae | Mentha spicata | Les (2017) | |

| Lemnaceae | Lemna sp. | DeLoach et al. (1979) | Munroe (1972) |

| Linderniaceae | Lindernia sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Linderniaceae | Micranthemum sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Lythraceae | Rotala sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Marsileaceae | Marsilea sp. | Sen et al. (2019) | |

| Menyanthaceae | Nymphoides aquatica | Stoops et al. (1998) | |

| Menyanthaceae | Nymphoides peltata | Tomasko et al. (2022) | |

| Nelumbonaceae | Nelumbo lutea | Les (2017) | |

| Nymphaeaceae | Nuphar lutea | Harms and Grodowitz (2010) | |

| Nymphaeaceae | Nymphaea elegans | Les (2017) | |

| Nymphaeaceae | Nymphaea gigantea | Sands and Kassulke (1984) | |

| Nymphaeaceae | Nymphaea mexicana | Harms and Grodowitz (2010) | |

| Nymphaeaceae | Nymphaea odorata | Herlong (1979) | |

| Onagraceae | Ludwigia peploides | Sands and Kassulke (1984) | |

| Onagraceae | Ludwigia sp. | Center et al. (2002b) | |

| Plantaginaceae | Bacopa sp. | Center et al. (2002b) | |

| Plantaginaceae | Limnophila sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Poaceae | Luziola sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Polygonaceae | Persicaria glabra | Les (2017) | |

| Polygonaceae | Persicaria hydropiperoides | Heppner and Habeck (1976) | |

| Polygonaceae | Persicaria punctata | Heppner and Habeck (1976) | |

| Polygonaceae | Polygonum glabrum | Heppner and Habeck (1976) | |

| Polygonaceae | Polygonum lapathifolium | Sands and Kassulke (1984) | |

| Pontederiaceae | Eichhornia crassipes | Knopf and Habeck (1976) | |

| Pontederiaceae | Eichhornia sp. | Center et al. (2002b) | |

| Pontederiaceae | Heteranthera dubia | Harms et al. (2011) | |

| Pontederiaceae | Pontederia rotundifolia | DeLoach et al. (1979) | |

| Pontederiaceae | Pontederia sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Potamogetonaceae | Potamogeton natans | Munroe (1972) | |

| Potamogetonaceae | Potamogeton nodosus | Harms and Grodowitz (2010) | |

| Salicaceae | Salix sp. | Habeck et al. (2021) | |

| Salviniaceae | Azolla carolina | Center et al. (2002a) | |

| Salviniaceae | Azolla filiculoides | Hill (1998) | |

| Salviniaceae | Azolla pinnata | Knopf and Habeck (1976) | Hill (1998) |

| Salviniaceae | Salvinia molesta | Knopf and Habeck (1976) | |

| Salviniaceae | Salvinia minima | Center et al. (2002a) | Tipping et al. (2012) |

| Typhaceae | Sparganium americanum | Stoops et al. (1998) |

Samea multiplicalis is distributed from Brazil and Argentina to the southeastern United States (Center et al. 2002a; DeLoach et al. 1979) and was introduced in Australia as part of a biocontrol effort to control Salvinia molesta D.S. Mitchel (Salviniaceae) (Sands and Kassulke 1984). It belongs to a small clade of species that evolved a semi-aquatic lifestyle, while its sister clades within the subfamily Spilomelinae remain terrestrial (Mally et al. 2019; James E. Hayden, personal communication). Its natural history is better understood than that of E. obliteralis, at least in part due to its suggested use as a biological control agent for several introduced ornamental aquatic plants in the United States and abroad (Bennett 1975; DeLoach et al. 1979; Sands and Kassulke 1984; Tewari and Johnson 2011). Its full lifecycle takes 25–40 days (Bennett 1966; Knopf and Habeck 1976; Sands and Kassulke 1984; Taylor 1988). Females lay eggs singly on either side of the leaf but prefer ovipositing on the adaxial side (Bennett 1966; Knopf and Habeck 1976; Sands and Kassulke 1984). The primary larval host plant of S. multiplicalis is water lettuce, Pistia stratiotes L. (Araceae), which is widely distributed across the world’s tropics and subtropics, but it also feeds on other aquatic plants (Table 1 and references therein). Larvae are reported to construct a gallery or tunnel composed of silk between the hairs of the host plant at early life stages and a silk cocoon for pupation (Knopf and Habeck 1976; Sands and Kassulke 1984), but their silk use has not been described further.

In the present study, we provide an updated and detailed account of the life history of these two aquatic moths distributed throughout Florida. Specifically, we report their development times, describe their behavioral adaptations to the aquatic environment, and characterize their different life stages and silk uses through high quality images.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling

All sampling for this study took place in 2024. Water lettuce (P. stratiotes) was sourced from multiple natural sites within and around Gainesville, Florida: Boulware Springs Park (Figure 1A, 29.6208056 °N, 82.3070000 °W), Chapman’s Pond and Nature Trails (Figure 1B, 29.6206111 °N, 82.4170556 °W), and Lake Alice (Figure 1C, 29.6428333 °N, 82.3633611 °W); on Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services 08208 permit number 2024-024 and City of Gainesville Parks, Recreation & Cultural Affairs Special Use Authorization granted to B. Foquet. As per permit requirements, P. stratiotes were double-bagged and transported in a cooler to Florida Museum of Natural History’s McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity (MGCL), and all rearing took place in a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) approved quarantine facility.

Collection sites in Gainesville, Florida. (A) Boulware Springs Park. (B) Chapman’s Pond and Nature Trails. (C) Lake Alice.

Elophila obliteralis was collected at Chapman’s Pond and Nature Trails, either by light sheeting for adults using a LepiLED Maxi light (Brehm 2017) in front of a vertical white sheet or with an aquatic net for caterpillars. Samea multiplicalis was collected with an aquatic net from Boulware Springs Park and from Chapman’s Pond and Nature Trails.

2.2 Species identification

Species identifications of both adults and caterpillars were confirmed by Dr. James E. Hayden (personal communication), and voucher specimens from our rearing colony were deposited in the pinned collection at MGCL. Additionally, we confirmed the identification of our specimens by sequencing the 658 bp “Barcode” region of the CO1 gene. DNA was extracted from three adults each of S. multiplicalis and E. obliteralis with a QIAGEN DNeasy kit using the manufacturer’s suggested protocol. We subsequently performed a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using LEP1 primers (LEPF1-ATTCAACCAATCATAAAGATAT, LEPR1-TAAACTTCTGGATGTCCAAAAA) as follows: 1 min at 94 °C, followed by four cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 40 s at 45 °C, and 1 min at 68 °C, followed by 34 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 40 s at 51 °C, 1 min at 68 °C, ending with 5 min at 68 °C. We confirmed the presence of a PCR amplicon using gel electrophoresis. Amplicons were sequenced by Eurofins Genomics, and sequence identifications were confirmed by performing a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; Altschul et al. 1990) search to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nr database (Sayers et al. 2025). Percent identity of the S. multiplicalis and E. obliteralis samples relative to their species references were 99.23–100.00 % and 99.84–100.00 %, respectively. Sequences were submitted to NCBI (Genbank accession numbers: PV335558–PV335563).

2.3 Rearing

We reared E. obliteralis and S. multiplicalis on water lettuce in a temperature-controlled rearing room at 24 °C with lights programmed on a 12:12 h L:D cycle. All eggs and larvae were kept in plastic containers that were filled halfway with water and contained one or more host plants. The container lids had mesh holes for ventilation. When plants started to deteriorate or were mostly eaten, fresh P. stratiotes were placed in direct contact with old plants, allowing larvae to relocate before removal of the old plants the next day. Containers of both species were checked daily for pupae, which were moved to a shallow water dish inside a species-specific flight cage to eclose and reproduce. Adults were provided with a tube filled with Gatorade™ (fruit punch flavor) for food. An open cup of water containing one to three P. stratiotes plants was provided as an oviposition site.

2.3.1 Elophila obliteralis

Adult E. obliteralis were placed in a 5.08 cm × 5.08 cm × 7.62 cm mesh pop-up flight tent, containing a cup with water and a P. stratiotes plant so that moths could mate and lay eggs. The cage was checked daily and any P. stratiotes that contained a cluster of eggs was transferred to a 600 mL plastic cup, along with one to two P. stratiotes plants that were smaller than 5 cm across, with leaves angled 45° or less from the water surface. Second instar E. obliteralis were transferred together with the plant they were on to small aquarium tanks (0.5 L). Each plant containing E. obliteralis was centered between two fresh P. stratiotes to allow caterpillars to disperse. As caterpillars grew into third instars, four to five individuals were transferred together into a 3.8-L container as described above. Pupae were collected from the tank and placed in the bottom of the flight cage until emergence.

2.3.2 Samea multiplicalis

Adult S. multiplicalis were placed in a mesh pop-up flight tent as described above. When approximately 50 eggs were laid on the P. stratiotes plant, they were transferred together to a 3.8-L container containing several fresh plants of P. stratiotes. We kept approximately 50 S. multiplicalis individuals together in each tub until pupation. We selected P. stratiotes that were at least 5 cm in length, with leaves angled 45° or greater from the water surface. Because pupation often occurs between two leaves, these shelters and the pupae within were transferred together to the mesh pop-up flight tent before eclosion.

2.4 Study of life stages

Caterpillar behavior was observed daily. We recorded feeding and silk-spinning behavior, and photographed changes. We also documented the duration and unique features of the egg and each larval instar.

We photographed eggs and early instar caterpillars with a Canon EOS 5DSR, equipped with a KuangRen Macro Twin Lite KX-800 flash unit, an EF 200 mm lens with an additional attached infinity lens with 10× magnification, and StackShot macro rail package. The camera lens was manually focused, and the StackShot was set to 160 steps at a distance of 5 μm to capture a magnified shot of leaf characteristics and egg positioning. Egg images were rendered in Helicon Focus 8.2 (RRID:SCR_014462) to increase the depth of field. Later instars were imaged using a Canon EOS 5D Mark 4 with 2.8L Macro IS USM lens. All images were edited in Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop.

3 Results

We recorded each life stage of S. multiplicalis and E. obliteralis, from egg deposition into adulthood, and describe their life histories in detail below. Both species were found at all three field sites. However, S. multiplicalis was very abundant at Boulware Springs Park (Figure 1A), while E. obliteralis was more common at Chapman’s Pond and Nature Trails (Figure 1B). At Lake Alice, both species were only occasionally encountered. Even though not statistically tested, we observed that each species seemed to prefer water lettuce with a different structure. S. multiplicalis seemed to prefer large plants with upright leaves, avoiding smaller plants or plants with leaves flat on the water surface. In contrast, E. obliteralis seemed to preferentially deposit eggs on leaves flat on the water surface, and similarly this is the type of plants where most caterpillars were found. These findings were based on our observations, and further study would be necessary to measure preference for different structures. The total life span of S. multiplicalis was 32–38 days from egg to adult. E. obliteralis had a longer life cycle than S. multiplicalis, lasting 47–54 days, with each life stage taking more time than for S. multiplicalis.

3.1 Samea multiplicalis

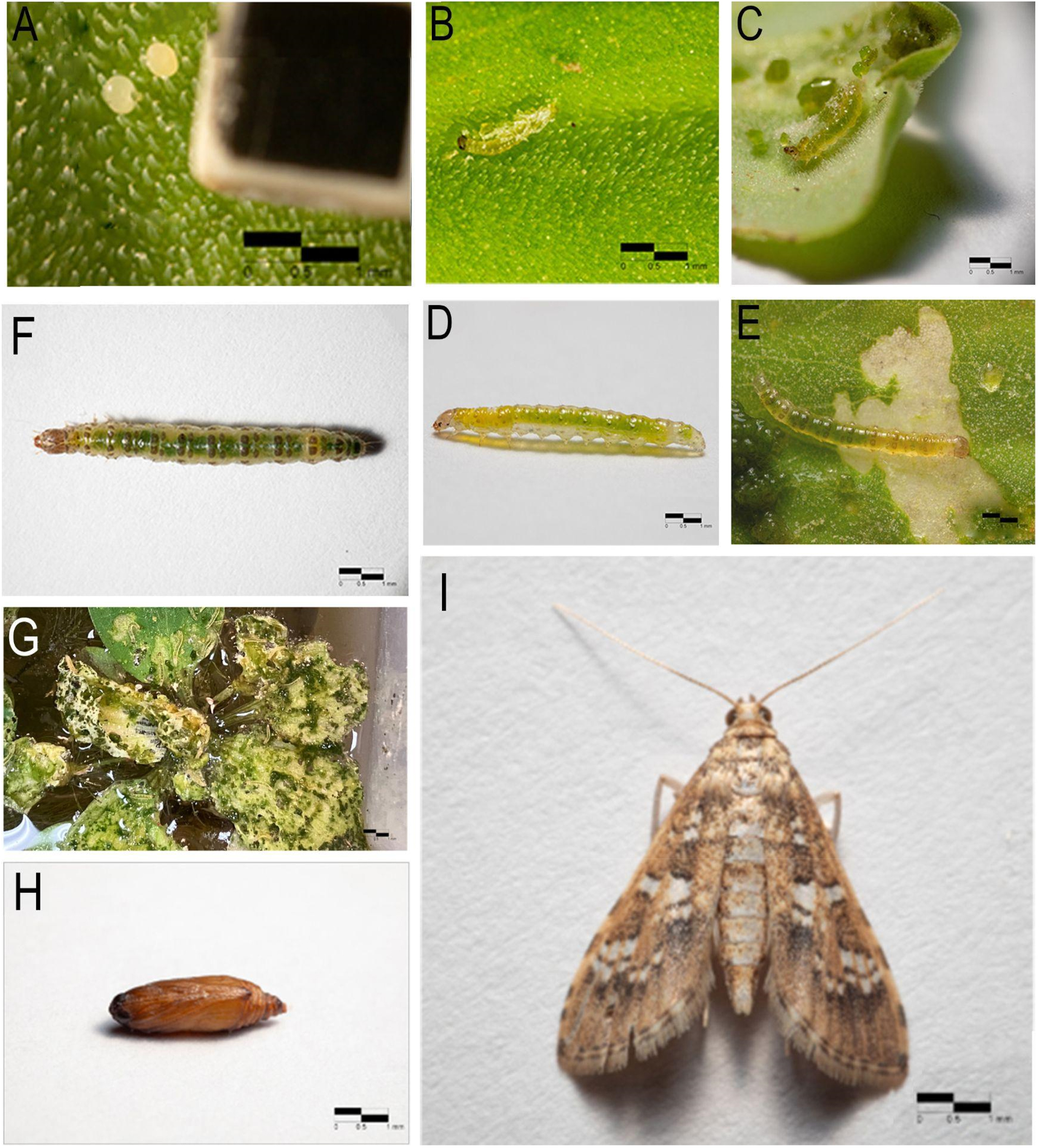

Eggs of S. multiplicalis (Figure 2A) were white and laid individually above the water surface, scattered between hairs on water lettuce. Eggs were generally laid on the adaxial surface of leaves, but were occasionally found on the abaxial side. Each egg was circular and protruded from the hairs with the bottom surface adhered to the leaf. After hatching, first instar caterpillars were 1 mm in size and translucent to cream in color. The first instar lasted 2–3 days and displayed a distinct silk spinning behavior of constructing a silk gallery that is only slightly wider than its own body width (Figure 2B). They fed under the silk by eating the epidermal layer of the plant and extended their gallery further as they grew and fed (Figure 2B). As a result, the gallery started out very narrow and gradually broadened as it expanded further on the leaf. The second instar measured approximately 3.8 mm in length and lasted 3–4 days (Figure 2C). The third instar lasted approximately 3–5 days, and larvae were approximately 6.25 mm in length (Figure 2D). During the second and third instar, setae and the sclerotization of spiracles became visible on the surface of the body. During the second and third instar, caterpillars extended their galleries to the abaxial side of the leaf. Second and third instar larvae typically did not leave their gallery; they fed, defecated, and molted within the confines of their silk cover.

Life history of Samea multiplicalis. (A) Eggs. (B–F) First-through fifth-instar larvae, in respective order. (G) Fourth-instar larval feeding pattern. (H) Pupa. (I) Adult moth.

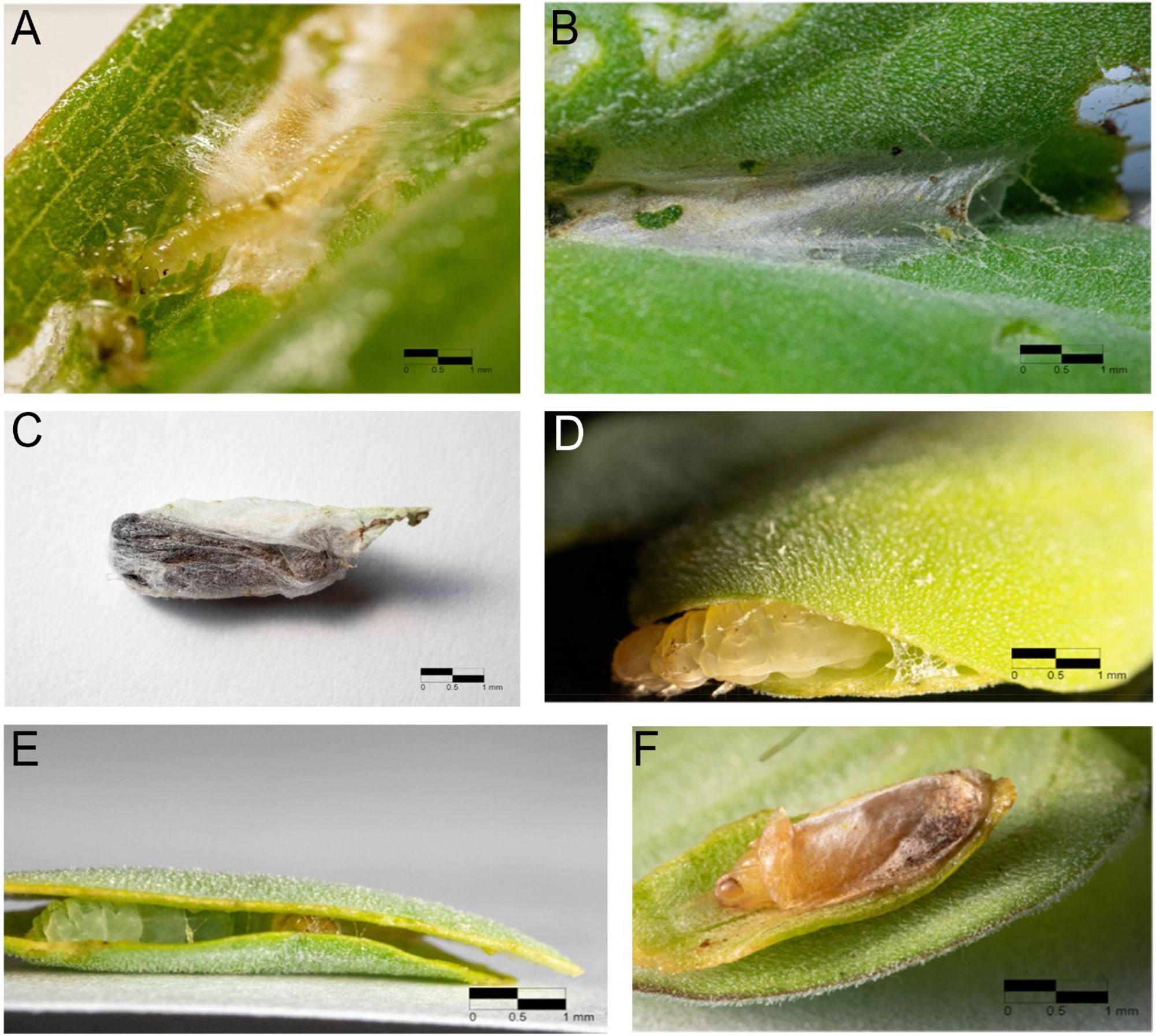

Third instar larvae began spinning a less dense web of silk, often near the base of the plant (Figure 3A). Larger third instar caterpillars generally fed on the upper surface of the plant, avoiding direct contact with the water surface. Fourth instars (Figure 2E) had a darker greenish-yellow body with a brown head capsule, providing effective camouflage on the leaf background. When at rest, caterpillars hid in their web among the base of leaves. Webs were often covered in frass. This instar lasted 4–5 days and measured approximately 9 mm. The fifth instar lasted 5–6 days, and was characterized by having a dark brown head capsule and spiracles, pronounced setae, and a long abdomen, with its total body length measuring up to 10 mm (Figure 2F). While larvae in the fourth and fifth instars primarily fed on the upper surface of P. stratiotes leaves, they occasionally swam between host plants to reach a new food source, especially when their previous host plant was fully consumed or when it was shared with conspecifics. Before pupation, larvae ate less and spent more time hidden at the base of the host plant leaves. Three to four days after turning into their final instar, feeding ceased and the larva entered the wandering stage, leaving their silk webs to find a suitable location for pupation.

Silk spinning behavior of Samea multiplicalis and Elophila obliteralis. (A) Third-instar S. multiplicalis before molting under its silk cover. (B) Cocoon of S. multiplicalis. (C) Inner silk layer of S. multiplicalis cocoon. (D–E) Silk spun to maintain a ‘sandwich’ of leaves in final instar E. obliteralis. (F) Silk cocoon cover inside leaf ‘sandwich’ of E. obliteralis.

Pupation took place in a cocoon between two leaves or on a leaf with a strong indentation, and caterpillars occasionally swam when searching for an optimal pupation site. The pupation site was typically close to the base of the plant but above the water surface. Occasionally, pupation took place near leaf apices or on the abaxial side of a leaf in close proximity to the water. Caterpillars produced a dense, narrow, cylindrical silk cocoon with loose silk strands on the exterior that adhered it to the leaf surface (Figure 3B). Within the cocoon, there is a thin lining of silk that surrounded the pupa (Figures 2I and 3C). Pupae measured approximately 8.5 mm in length. Pupal duration of S. multiplicalis was approximately 4–5 days. In captivity, adults fed and mated within a day after eclosion. Adult S. multiplicalis had a tan to light-brown color with dark-brown and white markings, and a wingspan of approximately 17 mm (Guenée 1854; Figure 2I). Females seemed to prefer P. stratiotes plants with upright leaves, at a 45° angle with the water surface, possibly because its structure provided ample surface for oviposition. Egg laying continued for several days.

3.2 Elophila obliteralis

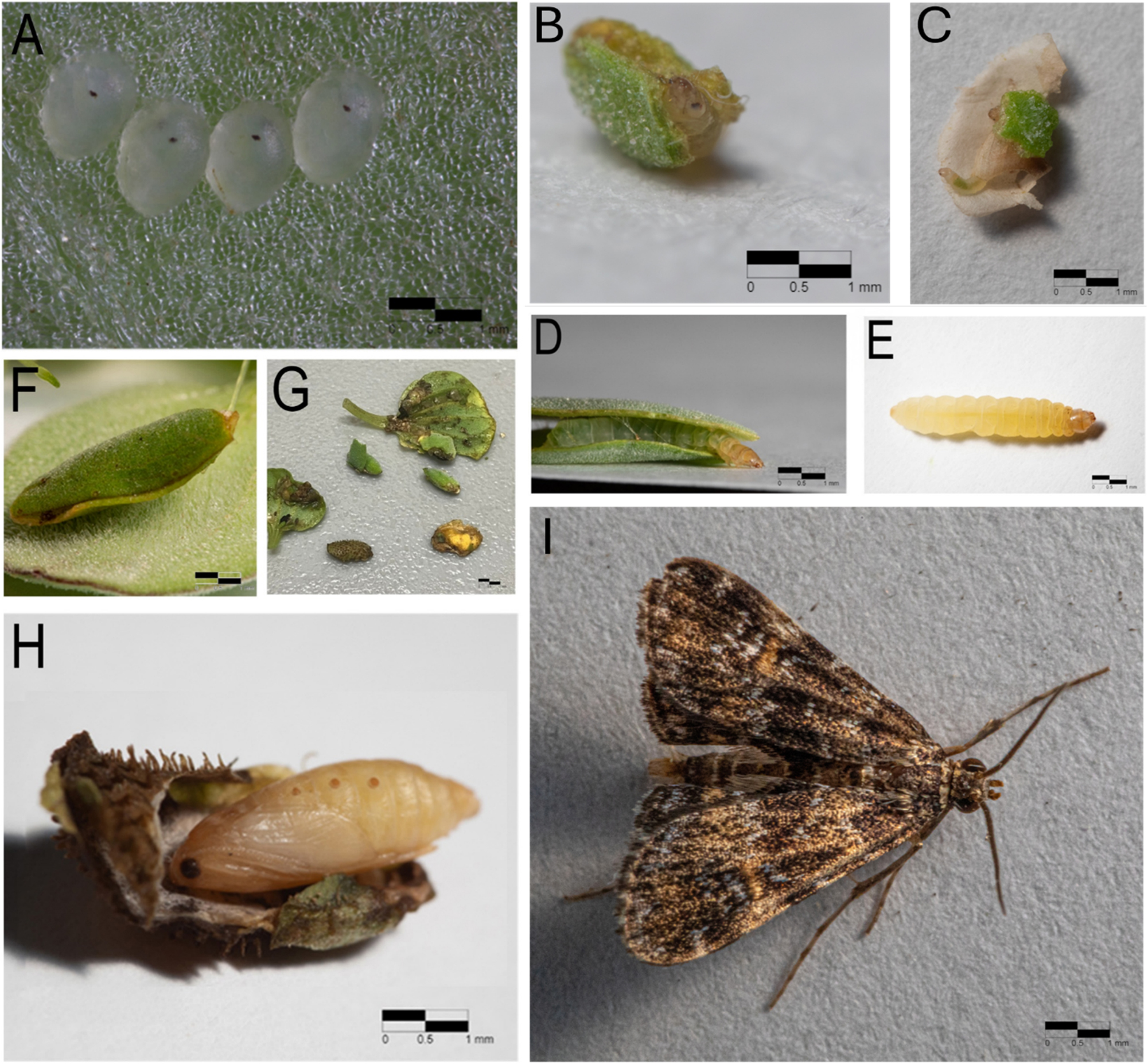

Eggs of E. obliteralis were laid underwater, near the P. stratiotes leaf margin in small clusters of four to seven. They were oval, translucent, and flattened, and the larvae hatched after 8–9 days (Figure 4A). After hatching, first instar caterpillars were up to 1 mm in length and translucent. Caterpillars wandered before starting to feed, often leaving the plant from which they originated. They chewed off small pieces of leaves from their host plant or obtained loose plant material from nearby plants such as Lemna sp. (Araceae). They created their case on the underside of their host plant leaf by cutting leaves around the margin of plants, avoiding the inner leaves of P. stratiotes (Figure 4B). At our primary field site for E. obliteralis, (Chapman’s Pond and Nature Trails, Figure 1B), cases were made of a large variety of plant materials, including other aquatic plants. The first instar, in our indoor captive rearing experiment, lasted 8–9 days. Second instar larvae are 1.5 mm in length and whitish green (Figure 4C). The second instar lasted 8–9 days. Before molting, the second instar wandered on the plant searching for a location to create a larger case. In these early instars, cases were not always made of a single piece of leaf but sometimes consisted of many smaller pieces that were woven together with silk.

Life history of Elophila obliteralis. (A) Eggs. (B–E) First-through fourth-instar larvae, in respective order. (F) Pupal casing. (G) Various casings of E. obliteralis. (H) Pupa. (I) Adult moth.

The third instar larva was approximately 3 mm in length and was whitish green with a tan head capsule (Figure 4D). Caterpillars in this instar often cut out two oval pieces of host plant leaf and created a larger case. This instar lasted 6–8 days. The fourth instar was yellowish white (Figure 4E), and characterized by having a fully formed case, consisting of two oval leaf pieces of P. stratiotes measuring about 1 cm in length and that was tightly bound, sandwiching the caterpillar inside (Figure 3D and E). These cases had a small opening on one end, which allowed the larva to stick its head out of the case to feed. When threatened, larvae retreated into their case. This instar lasted 6–7 days. The fifth instar was white and covered with papillae, but as the caterpillar grew, the anterior portion of the larva (from the fourth abdominal segment forward) turned increasingly yellowish brown. This instar typically lasted 8–9 days and grew to about 6 mm in length. The fifth instar larva did not always generate a new case and often remained in its fourth instar case until pupation (Figure 4F). Pupation took place inside of the case, underwater on the stem or upper root of their host plant. The pupa (Figure 4H) was bound in a dense oval silk casing adhered to the insides of both P. stratiotes leaves, and the entry was sealed with silk (Figure 3F). In the field, cases were found to occasionally be made of other plant materials, including small sticks and dead plant matter (Figure 4G). Elophila obliteralis remained a pupa for 5–6 days before emerging as an adult (Figure 4I). In captivity, adults fed and mated within a day after eclosion. Adult E. obliteralis had a dark brown to black coloration with light markings (Figure 4I). Females seemed to prefer plants with leaves lying on the water surface, allowing easy deposition of eggs under the water surface.

4 Discussion

We have provided a detailed description of the natural history of S. multiplicalis and E. obliteralis. The two species overlap largely in distribution and share many host plants (Table 1). We found them to coexist in all three field sites in Florida. At Boulware Springs Park (Figure 1A), where P. stratiotes was the dominant aquatic plant, S. multiplicalis was more abundant. In contrast, at Chapman's Ponds and Nature Trails (Figure 1B), which hosts a diverse aquatic plant community, E. obliteralis was the more abundant species. Although these two species were found at the same sites, their specialization on different plant parts appeared to facilitate coexistence with minimal competition. S. multiplicalis primarily fed on and inhabited plant parts above the water surface, while E. obliteralis was largely restricted to the submerged portions of the same plants. Interestingly, when the two species were reared together in captivity, S. multiplicalis consistently outcompeted E. obliteralis due to its higher growth rate and tendency to destroy or heavily damage its host plant. S. multiplicalis did more damage to P. stratiotes, both in our laboratory and in the field where large numbers of S. multiplicalis resulted in large numbers of P. stratiotes plants being consumed significantly, only to regenerate when caterpillar abundance was reduced.

Data generated here on the development of S. multiplicalis is largely congruent with prior studies. Earlier work reported five to seven instars for S. multiplicalis and we observed five instars in our laboratory colony. The fewer number of instars that we observed may be caused by high nitrogen levels of our host plants (Taylor 1988). In our colony, the total lifespan of S. multiplicalis was 32–38 days, which is within the range of what was reported earlier (Bennett 1966; Knopf and Habeck 1976; Sands and Kassulke 1984; Taylor 1988). The total duration of the larval stage was 18–25 days, which was slightly faster than the 21–35 days reported by Sands and Kassulke (1984) at 26 °C on S. molesta but slower than the 15 days reported at 28 °C on P. stratiotes (Knopf and Habeck 1976). Pupal development in our study seemed a bit faster than reported before: 4–5 days in our study, 5–8 days in earlier studies (Knopf and Habeck 1976; Sands and Kassulke 1984). As we kept our rearing room at a constant temperature of 24 °C, there is likely an interaction between temperature and host plant for this species. While some earlier studies suggested that S. multiplicalis has up to three generations and cannot be found in the adult stage during extreme cold and hot temperature periods (DeLoach et al. 1979; de Sousa Oliveira and de Souza 2023), we confirm other reports (e.g., Queensland, Australia; Taylor 1988) that caterpillars can be found year round when temperatures are within an acceptable range. We also frequently observed adults, pupae, and caterpillars (at various developmental stages) for both S. multiplicalis and E. obliteralis at all localities, indicating that both species likely have overlapping generations in central Florida.

Our study sets the stage for many future studies. For example, evolutionary pressures that led to multiple repeated origins of aquatic or semi-aquatic behavior in caterpillars are currently unclear (Pabis 2018). A transition to an aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyle may benefit the insect by allowing species access to additional resources, such as aquatic plants, where competition may be less intense than in terrestrial environments. Alternatively, a transition to living underwater may allow these insects to escape predators or parasitoids. We only observed one case of parasitism in our study; a caterpillar of E. obliteralis collected at Lake Alice was parasitized by Apsilops hirtifrons (Ashmead) (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) (Judd 1953), which was deposited in the Florida State Collection of Arthropods (FSCA) under the accession number FSCA 00118657. Nonetheless, there are many observations of predation and parasitism for the two species studied here, including social wasps (Vespidae; de Sousa Oliveira and de Souza 2023), parasitic flies (Tachinidae; Knopf and Habeck 1976) and parasitic wasps (Ichneumonidae and Braconidae; Fernandez-Triana et al. 2020; Judd 1953; Knopf and Habeck 1976; Newton and Sharkey 2000; Semple and Forno 1987; Sharkey et al. 2011). A future study comparing predation and parasitism levels between closely related aquatic and terrestrial groups would be beneficial, as no such study has been conducted.

Studies have shown that both terrestrial and aquatic insects use silk for a variety of purposes, including constructing shelters, building retreats, creating feeding structures, and facilitating mobility in their environment (Mackay and Wiggins 1979; Sutherland et al. 2010). Our study revealed that both species used silk intensively throughout their life, making them well adapted to the aquatic environment. Additionally, we observed caterpillars of different instars altering their silk use based on their behavior during each life stage. For instance, early instar S. multiplicalis caterpillars exclusively fed and defecated under their tunnel of dense silk threads. We hypothesize that this silk cover provides protection from predation, parasitism, desiccation, and protection from water during early life stages, when caterpillars are very vulnerable. During the second and third instar, caterpillars started spinning a loose web of silk fibers, offering less protection but covering larger areas. They started to utilize the natural structure of their host plant for shelter, reducing their dependence on silk for protection. The prepupal caterpillar span a robust silk cocoon, which featured anchor lines that secured the plant material and a tight, durable silk coating in which pupation took place. Similarly, E. obliteralis caterpillars created a small dome-like case that consisted of one or multiple small leaf fragments during the first instar that was attached to the host plant. Although this restricted them to a very limited feeding area, it provided enough food at that life stage. As caterpillars grew and consumed more food, they changed their case to a sandwich-like case that was carried wherever they go. Even though they pupated within this case, they generated an additional tight silk layer, similar to the inner layer of cocoon silk in S. multiplicalis. As such, E. obliteralis seems to be much more dependent on silk throughout its life, as its case does not only provide a barrier against predation, but can also serve as camouflage.

Funding source: University of Florida

Award Identifier / Grant number: Research Opportunity Seed Fund (award number AWD06

Funding source: National Science Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: EF-2217159

Award Identifier / Grant number: REPS supplement to EF-2217159

Funding source: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Award Identifier / Grant number: “Identification of insect eggs using artificial in

Acknowledgments

We thank Anastasia Baluk Garavaglia, Nolan Ferguson, Andrew Hong, Ava Johnson, Kadie Mariano, Skyla Sheehy and Olivia van der Vlugt (McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL) for help with moth rearing and collecting. Daniel J. Rhodes (Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL) helped with macrophotography of different life stages. James E. Hayden (Division of Plant Industry, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Gainesville, FL) confirmed the identification of caterpillars and adults of S. multiplicalis and E. obliteralis and provided guidance for permit applications. José I. Martinez (Division of Plant Industry, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Gainesville, FL) helped collect E. obliteralis and provided initial rearing support. The moth image in Figure 3I is attributed to Mike Chapman (https://www.flickr.com/photos/41515403@N05/54090655216/) and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial 2.0 Generic license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/). We thank the City of Gainesville Parks, Recreation & Cultural Affairs for providing a permit for the collection of S. multiplicalis, E. obliteralis, and P. stratiotes, and the Division of Plant Industry of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS-DPI) for providing a permit to move P. stratiotes.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. AYK, BF and GD conceptualized the paper. BF, GD and RJLC conducted the research. Visualization was executed by GD. AYK, BF, DP, GD, JB and RJLC wrote the original draft. AYK and BF supervised the study and acquired funding support. BF administered the project.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Research funding: The University of Florida Research Opportunity Seed Fund (award number AWD06265) to AYK supported part of this project. Funding was also provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF) grant EF-2217159 to AYK; GDP was supported by a REPS suppent to this award. Photography equipment used to image eggs and early instars was funded by a USDA-APHIS-AQI grant, titled “Identification of insect eggs using artificial intelligence (AI) image analysis” to AYK.

-

Data availability: CO1 sequences were submitted to the appropriate database (Genbank accession numbers: PV335558-PV335563).

References

Adis, J. (1983). Eco-entomological observations from the Amazon IV. Occurrence and feeding habits of the aquatic caterpillar Palustra laboulbeni Bar, 1873 (Arctiidae: Lepidoptera) in the vicinity of Manaus, Brazil. Acta Amazonica 13: 31–36, https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-43921983131031.Search in Google Scholar

Agassiz, D. (2012). The Acentropinae (Lepidoptera: Pyraloidea: Crambidae) of Africa. Zootaxa 3494: 1–73, https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3494.1.1.Search in Google Scholar

Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., and Lipman, D.J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403–410, https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999.Search in Google Scholar

Bennett, F.D. (1966). Investigations on the insects attacking the aquatic ferns, Salvinia spp. in Trinidad and northern South America. Proc. S. Weed Conf. 19: 497–504.Search in Google Scholar

Bennett, F.D. (1975). Insects and plant pathogens for the control of Salvinia and Pistia. In: Proceedings of symposium on water quality management through biological control. University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, pp. 28–35.Search in Google Scholar

Brehm, G. (2017). A new LED lamp for the collection of nocturnal Lepidoptera and a spectral comparison of light-trapping lamps. Nota Lepidopterol. 40: 87–108, https://doi.org/10.3897/nl.40.11887.Search in Google Scholar

Center, T.D., Dray, F.A.Jr, Jubinsky, G.P., and Grodowitz, M.J. (2002a). Waterlettuce moth, Samea multiplicalis (Guenée). In: Insects and other arthropods that feed on aquatic and wetland plants. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC, pp. 170–171, Technical Bulletin No. 1870.Search in Google Scholar

Center, T.D., Dray, F.A.Jr, Jubinsky, G.P., and Grodowitz, M.J. (2002b). Waterlily leafcutter, Synclita obliteralis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Nymphulinae: Nymphulini). In: Insects and other arthropods that feed on aquatic and wetland plants. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC, pp. 182–183, Technical Bulletin No. 1870.Search in Google Scholar

de Sousa Oliveira, G.C. and de Souza, M.M. (2023). New records of predation of Samea multiplicalis (Guenée, 1854) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) by social wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) on Salvinia auriculata (Aublet, 1775) (Salviniales: Salviniaceae) in Brazil. Rev. Chil. Entomol. 49: 527–531, https://doi.org/10.35249/rche.49.3.23.11.Search in Google Scholar

DeLoach, C.J., DeLoach, D.J., and Cordo, H.A. (1979). Observations on the biology of the moth, Samea multiplicalis, on waterlettuce in Argentina. J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 17: 42–44.Search in Google Scholar

Dray, F.A.Jr, Center, T.D., and Habeck, D.H. (1993). Phytophagous insects associated with Pistia stratiotes in Florida. Environ. Entomol. 22: 1146–1155, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/22.5.1146.Search in Google Scholar

Dyar, H.G. (1906). The North American Nymphulinæ and Scopariinæ. J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 14: 77–107.Search in Google Scholar

Fernandez-Triana, J., Kamino, T., Maeto, K., Yoshiyasu, Y., and Hirai, N. (2020). Microgaster godzilla (Hymenoptera, Braconidae, Microgastrinae), an unusual new species from Japan which dives underwater to parasitize its caterpillar host (Lepidoptera, Crambidae, Acentropinae). J. Hymenoptera Res. 79: 15–26, https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.79.56162.Search in Google Scholar

Gill, S., Reeser, R., and Raupp, M. (2008). Controlling two aquatic plant pests Nymphuliella daeckealis (Haimbach) and the waterlily leafcutter, Synclita obliteralis (Walker). The University of Maryland Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet 818, College Park, Maryland, United States.Search in Google Scholar

Guenée, A. (1854). Histoire naturelle des insectes. In: Spécies général des lépidoptères VIII. Deltoides et Pyralites. Roret, Paris, France.Search in Google Scholar

Habeck, D.H., Cuda, J.P., and Weeks, E.N.I. (2021). Waterlily leafcutter, Elophila obliteralis (Walker) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae: Acentropinae). Electronic Data Information Source, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, EENY 424, Available at: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN803 (Accessed 16 March 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Harms, N.E. and Grodowitz, M.J. (2010). Survey of insect herbivores associated with aquatic and wetland plants in the United States. ERDC/TN APCRP-BC-21. Aquatic Plant Control Research Program, Vicksburg, Mississippi, United States.Search in Google Scholar

Harms, N., Grodowitz, M., and Kennedy, J. (2011). Insect herbivores of water stargrass (Heteranthera dubia) in the US. J. Freshwater Ecol. 26: 185–194, https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.2011.554217.Search in Google Scholar

Heppner, J.B. and Habeck, D.H. (1976). Insects associated with Polygonum (Polygonaceae) in North Central Florida. I. Introduction and Lepidoptera. Fla. Entomol. 59: 231–239, https://doi.org/10.2307/3494258.Search in Google Scholar

Herlong, D.D. (1979). Aquatic Pyralidae (Lepidoptera: Nymphulinae) in South Carolina. Fla. Entomol. 62: 188–193, https://doi.org/10.2307/3494057.Search in Google Scholar

Hill, M.P. (1998). Herbivorous insect fauna associated with Azolla species (Pteridophyta: Azollaceae) in southern Africa. Afr. Entomol. 6: 270–272.Search in Google Scholar

Judd, W.W. (1953). A study of the population of insects emerging as adults from the Dundas Marsh, Hamilton, Ontario, during 1948. Am. Midl. Nat. 49: 801–824, https://doi.org/10.2307/2485209.Search in Google Scholar

Knopf, K.W. and Habeck, D.H. (1976). Life history and biology of Samea multiplicalis. Environ. Entomol. 5: 539–542, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/5.3.539.Search in Google Scholar

Lange, W.H. (1956). Aquatic Lepidoptera. In: Usinger, R.L. (Ed.), Aquatic insects of California, with keys to North America genera and California species. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, United States, pp. 271–288.10.1525/9780520320390-014Search in Google Scholar

Les, D.H. (2017). Aquatic dicotyledons of North America: ecology, life history, and systematics. Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, Florida, United States.10.1201/9781315118116Search in Google Scholar

Mackay, R.J. and Wiggins, G.B. (1979). Ecological diversity in Trichoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 24: 185–208, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.24.010179.001153.Search in Google Scholar

Mally, R., Hayden, J., Neinhuis, C., Jordal, B., and Nuss, M. (2019). The phylogenetic systematics of Spilomelinae and Pyraustinae (Lepidoptera: Pyraloidea: Crambidae) inferred from DNA and morphology. Arthropod Syst. Phylog. 77: 141–204.Search in Google Scholar

Mey, W. and Speidel, W. (2008). Global diversity of butterflies (Lepidoptera) in freshwater, In Balian EK, Martens CL, Segers H. [eds.], A global assessment of animal diversity in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595: 521–528, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9038-9.Search in Google Scholar

Mitter, C., Davis, D.R., and Cummings, M.P. (2017). Phylogeny and evolution of Lepidoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 62: 265–283, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035125.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Munroe, E. (1972). The moths of America North of Mexico: Pyraloidea: Pyralidae (Part) comprising subfamilies Scopariinae, Nymphulinae. EW Classey and the Wedge Entomological Research Foundations, London, UK.Search in Google Scholar

Newton, B.L. and Sharkey, M.J. (2000). A new species of Bassus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Agathidinae) parasitic on Samea multiplicalis, a natural control agent of waterlettuce. Fla. Entomol. 83: 284–289, https://doi.org/10.2307/3496347.Search in Google Scholar

Pabis, K. (2018). What is a moth doing under water? Ecology of aquatic and semi-aquatic Lepidoptera. Knowl. Manage. Aquat. Ecosyst. 419: 42, https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2018030.Search in Google Scholar

Sands, D.P.A. and Kassulke, R.C. (1984). Samea multiplicalis [Lep.: Pyralidae], for biological control of two water weeds, Salvinia molesta and Pistia stratiotes in Australia. Entomophaga 29: 267–273, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02372113.Search in Google Scholar

Sarkar, S. (2022). Waterlily leaf cutter moth, Elophila obliteralis (Walker) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae: Acentropinae): an economic threat to Indian aquatic gardens. NDC E-BIOS 2: 71–76.Search in Google Scholar

Sayers, E.W., Beck, J., Bolton, E.E., Brister, J.R., Chan, J., Comeau, D.C., Connor, R., Feldgarden, M., Fine, A.M., Funk, K, et al.. (2025). Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 53: D20–D29, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae979.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Semple, J.L. and Forno, I.W. (1987). Native parasitoids and pathogens attacking Samea multiplicalis Guenée (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in Queensland. Aust. J. Entomol. 26: 365–366, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-6055.1987.tb01986.x.Search in Google Scholar

Sen, K., Bera, S., Ghorai, N., and Mukhopadhyay, R. (2019). Interaction of a Lepidopteran Elophila obliteralis Walker with floating fern Azolla pinnata R. Br. in the paddy field of West Bengal, India. Indian Fern J. 36: 291–296.Search in Google Scholar

Sharkey, M., Parys, K., and Stoelb, S. (2011). A new genus of Agathidinae with the description of a new species parasitic on Samea multiplicalis (Guenée). J. Hymenoptera Res. 23: 43–53, https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.23.1100.Search in Google Scholar

Solis, M.A. (2019). Aquatic and semiaquatic Lepidoptera. In: Merritt, R.W., Cummins, K.W., and Berg, M.B. (Eds.), Introduction to aquatic insects of North America, 5th ed. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, Dubuque, Iowa, United States, pp. 765–789.Search in Google Scholar

Stoops, C.A., Adler, P.H., and McCreadie, J.W. (1998). Ecology of aquatic Lepidoptera (Crambidae: Nymphulinae) in South Carolina, USA. Hydrobiologia 379: 33–40.10.1023/A:1003269025247Search in Google Scholar

Sutherland, T.D., Young, J.H., Weisman, S., Hayashi, C.Y., and Merritt, D.J. (2010). Insect silk: one name, many materials. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 55: 171–188, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085401.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Taylor, M.F.J. (1988). Field measurement of the dependence of life history on plant nitrogen and temperature for a herbivorous moth. J. Anim. Ecol. 57: 873–891, https://doi.org/10.2307/5098.Search in Google Scholar

Tewari, S. and Johnson, S.J. (2011). Impact of two herbivores, Samea multiplicalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) and Cyrtobagous salviniae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), on Salvinia minima in south Louisiana. J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 49: 36–43.Search in Google Scholar

Tipping, P.W., Bauer, L., Martin, M.R., and Center, T.D. (2009). Competition between Salvinia minima and Spirodela polyrhiza mediated by nutrient levels and herbivory. Aquat. Bot. 90: 231–234, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2008.10.004.Search in Google Scholar

Tipping, P.W., Martin, M.R., Bauer, L., Pierce, R.M., and Center, T.D. (2012). Ecology of common salvinia, Salvinia minima Baker, in southern Florida. Aquat. Bot. 102: 23–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2012.04.005.Search in Google Scholar

Tomasko, R.E., Jennrich, S.J., Gorbach, K.R., and Warman, M.J. (2022). The potential of Elophila obliteralis larvae (waterlily leafcutter moth) as a biological control for the invasive aquatic plant Nymphoides peltata (yellow floating heart), Research Square (pre-print) https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1478601/v1 (Accessed 28 February 2025).Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Florida Entomological Society

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Life history descriptions of two aquatic Florida moth species (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Higher Apoidea activity on centipedegrass lawns than on dicotyledonous plants

- Dynamics of citrus pest populations following a major freeze in northern Florida

- Control of Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae) by trapping with banana vinegar

- Establishment, distribution, and preliminary phenological trends of a new planthopper in the genus Patara (Hemiptera: Derbidae) in South Florida, United States of America

- Comparative evaluation of the infestation of five varieties of citrus by the larvae of Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae)

- Impact of land use on the density of Bulimulus bonariensis (Stylommatophora: Bulimulidae) and its parasitic mite, Austreynetes sp. (Trombidiformes: Ereynetidae)

- First record of native seed beetle Stator limbatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on invasive earleaf acacia in Florida

- Establishment and monitoring of a sentinel garden of Asian tree species in Florida to assess potential insect pest risks

- Parasitism of Halyomorpha halys and Nezara viridula (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) sentinel eggs in Central Florida

- Genetic differentiation of three populations of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in Mexico

- Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) associated with blueberry cultivation in Central Mexico

- First report of Phidotricha erigens (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Epipaschiinae) injuring mango inflorescences in Puerto Rico

- Seed predation of Sabal palmetto, Sabal mexicana and Sabal uresana (Arecaceae) by the bruchid Caryobruchus gleditsiae (Coleoptera: Bruchidae), with new host and distribution records

- Genetic variation of rice stink bugs, Oebalus spp. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) from Southeastern United States and Cuba

- Selecting Coriandrum sativum (Apiaceae) varieties to promote conservation biological control of crop pests in south Florida

- First record of Mymarommatidae (Hymenoptera) from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador

- First field validation of Ontsira mellipes (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) as a potential biological control agent for Anoplophora glabripennis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in South Carolina

- Field evaluation of α-copaene enriched natural oil lure for detection of male Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in area-wide monitoring programs: results from Tunisia, Costa Rica and Hawaii

- Abundance of Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagnall) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and other thrips in commercial snap bean fields in the Homestead Agricultural Area (HAA)

- Performance of Salvinia molesta (Salviniae: Salviniaceae) and its biological control agent Cyrtobagous salviniae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in freshwater and saline environments

- Natural arsenal of Magnolia sarcotesta: insecticidal activity against the leaf-cutting ant Atta mexicana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

- Ethanol concentration can influence the outcomes of insecticide evaluation of ambrosia beetle attacks using wood bolts

- Post-release support of host range predictions for two Lygodium microphyllum biological control agents

- Missing jewels: the decline of a wood-nesting forest bee, Augochlora pura (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), in northern Georgia

- Biological response of Rhopalosiphum padi and Sipha flava (Hemiptera: Aphididae) changes over generations

- Argopistes tsekooni (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a new natural enemy of Chinese privet in North America: identification, establishment, and host range

- A non-overwintering urban population of the African fig fly (Diptera: Drosophilidae) impacts the reproductive output of locally adapted fruit flies

- Fitness of Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) on four economically important host fruits from Fujian Province, China

- Carambola fruit fly in Brazil: new host and first record of associated parasitoids

- Establishment and range expansion of invasive Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Phycitinae) in Texas

- A micro-anatomical investigation of dark and light-adapted eyes of Chilades pandava (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)

- Scientific Notes

- Evaluation of food attractants based on fig fruit for field capture of the black fig fly, Silba adipata (Diptera: Lonchaeidae)

- Exploring the potential of Amblyseius largoensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a biological control agent against Aceria litchii (Acari: Eriophyidae) on lychee plants

- Early stragglers of periodical cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) found in Louisiana

- Attraction of released male Mediterranean fruit flies to trimedlure and an α-copaene-containing natural oil: effects of lure age and distance

- Co-infestation with Drosophila suzukii and Zaprionus indianus (Diptera: Drosophilidae): a threat for berry crops in Morelos, Mexico

- Observation of brood size and altricial development in Centruroides hentzi (Arachnida: Buthidae) in Florida, USA

- New quarantine cold treatment for medfly Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in pomegranates

- A new invasive pest in Mexico: the presence of Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in chili pepper fields

- Acceptance of fire ant baits by nontarget ants in Florida and California

- Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

- Note on the nesting biology of Epimelissodes aegis LaBerge (Hymenoptera: Apidae)

- Mass rearing protocol and density trials of Lilioceris egena (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a biological control agent of air potato

- Cardinal predation of the invasive Jorō spider Trichophila clavata (Araneae: Nephilidae) in Georgia

- Book Reviews

- Review: Harbach, R.E. 2024. The Composition and Nature of the Culicidae (Mosquitoes). Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International and the Royal Entomological Society, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781800627994

- Retraction

- Retraction of: Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Life history descriptions of two aquatic Florida moth species (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Higher Apoidea activity on centipedegrass lawns than on dicotyledonous plants

- Dynamics of citrus pest populations following a major freeze in northern Florida

- Control of Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae) by trapping with banana vinegar

- Establishment, distribution, and preliminary phenological trends of a new planthopper in the genus Patara (Hemiptera: Derbidae) in South Florida, United States of America

- Comparative evaluation of the infestation of five varieties of citrus by the larvae of Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae)

- Impact of land use on the density of Bulimulus bonariensis (Stylommatophora: Bulimulidae) and its parasitic mite, Austreynetes sp. (Trombidiformes: Ereynetidae)

- First record of native seed beetle Stator limbatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on invasive earleaf acacia in Florida

- Establishment and monitoring of a sentinel garden of Asian tree species in Florida to assess potential insect pest risks

- Parasitism of Halyomorpha halys and Nezara viridula (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) sentinel eggs in Central Florida

- Genetic differentiation of three populations of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in Mexico

- Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) associated with blueberry cultivation in Central Mexico

- First report of Phidotricha erigens (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Epipaschiinae) injuring mango inflorescences in Puerto Rico

- Seed predation of Sabal palmetto, Sabal mexicana and Sabal uresana (Arecaceae) by the bruchid Caryobruchus gleditsiae (Coleoptera: Bruchidae), with new host and distribution records

- Genetic variation of rice stink bugs, Oebalus spp. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) from Southeastern United States and Cuba

- Selecting Coriandrum sativum (Apiaceae) varieties to promote conservation biological control of crop pests in south Florida

- First record of Mymarommatidae (Hymenoptera) from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador

- First field validation of Ontsira mellipes (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) as a potential biological control agent for Anoplophora glabripennis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in South Carolina

- Field evaluation of α-copaene enriched natural oil lure for detection of male Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in area-wide monitoring programs: results from Tunisia, Costa Rica and Hawaii

- Abundance of Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagnall) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and other thrips in commercial snap bean fields in the Homestead Agricultural Area (HAA)

- Performance of Salvinia molesta (Salviniae: Salviniaceae) and its biological control agent Cyrtobagous salviniae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in freshwater and saline environments

- Natural arsenal of Magnolia sarcotesta: insecticidal activity against the leaf-cutting ant Atta mexicana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

- Ethanol concentration can influence the outcomes of insecticide evaluation of ambrosia beetle attacks using wood bolts

- Post-release support of host range predictions for two Lygodium microphyllum biological control agents

- Missing jewels: the decline of a wood-nesting forest bee, Augochlora pura (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), in northern Georgia

- Biological response of Rhopalosiphum padi and Sipha flava (Hemiptera: Aphididae) changes over generations

- Argopistes tsekooni (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a new natural enemy of Chinese privet in North America: identification, establishment, and host range

- A non-overwintering urban population of the African fig fly (Diptera: Drosophilidae) impacts the reproductive output of locally adapted fruit flies

- Fitness of Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) on four economically important host fruits from Fujian Province, China

- Carambola fruit fly in Brazil: new host and first record of associated parasitoids

- Establishment and range expansion of invasive Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Phycitinae) in Texas

- A micro-anatomical investigation of dark and light-adapted eyes of Chilades pandava (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)

- Scientific Notes

- Evaluation of food attractants based on fig fruit for field capture of the black fig fly, Silba adipata (Diptera: Lonchaeidae)

- Exploring the potential of Amblyseius largoensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a biological control agent against Aceria litchii (Acari: Eriophyidae) on lychee plants

- Early stragglers of periodical cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) found in Louisiana

- Attraction of released male Mediterranean fruit flies to trimedlure and an α-copaene-containing natural oil: effects of lure age and distance

- Co-infestation with Drosophila suzukii and Zaprionus indianus (Diptera: Drosophilidae): a threat for berry crops in Morelos, Mexico

- Observation of brood size and altricial development in Centruroides hentzi (Arachnida: Buthidae) in Florida, USA

- New quarantine cold treatment for medfly Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in pomegranates

- A new invasive pest in Mexico: the presence of Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in chili pepper fields

- Acceptance of fire ant baits by nontarget ants in Florida and California

- Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

- Note on the nesting biology of Epimelissodes aegis LaBerge (Hymenoptera: Apidae)

- Mass rearing protocol and density trials of Lilioceris egena (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a biological control agent of air potato

- Cardinal predation of the invasive Jorō spider Trichophila clavata (Araneae: Nephilidae) in Georgia

- Book Reviews

- Review: Harbach, R.E. 2024. The Composition and Nature of the Culicidae (Mosquitoes). Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International and the Royal Entomological Society, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781800627994

- Retraction

- Retraction of: Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)