Abstract

The role of pollen from wind-pollinated plants as a food source for pollinators is often overlooked. Bees were observed foraging pollen in lawns from centipedegrass (Eremochloa ophiuroides [Munro] Hack.; Poaceae). However, it remains unclear whether bees also forage on the flowers of dicotyledonous plants when centipedegrass lawns are in full bloom. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the foraging behavior of bees when both flowering centipedegrass and dicotyledonous plants are available simultaneously. In 2023, containers of flowering goldenrod (Solidago canadensis L.; Asteraceae), butterfly bush (Buddleja davidii Franch.; Scrophulariaceae), and lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.; Lamiaceae) were placed on flowering centipedegrass lawns that were producing pollen. Observations revealed that foraging bees visited only the centipedegrass spikes and did not visit the flowers of dicotyledonous plants. In 2024, containers of butterfly bush and coneflower (Echinacea purpurea [L.] Moench; Asteraceae) were positioned on centipedegrass 1–3 d after mowing. Twelve days post-mowing, foraging bees were collected from both centipedegrass spikes and dicotyledonous plant flowers. Results indicated that a significantly greater number of bees were collected from centipedegrass spikes compared to the flowers of dicotyledonous plants. The bee species collected from centipedegrass were Bombus impatiens Cresson (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Melissodes bimaculatus Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Apidae), and Lasioglossum spp., (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), whereas only Halictus ligatus Say (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) and Lasioglossum were found on dicotyledonous plants. This suggests that flowering centipedegrass is a valuable resource for foraging bees, even when the flowers of dicotyledonous plants are also accessible.

Resumen

El papel del polen de plantas anemófilas como fuente de alimento para los polinizadores suele pasar desapercibido. Se ha observado a las abejas recolectando polen de céspedes de grama ciempiés (Eremochloa ophiuroides [Munro] Hack.; Poaceae). Sin embargo, aún no se sabe con certeza si también recolectan polen de las flores de plantas dicotiledóneas cuando los céspedes de grama ciempiés están en plena floración. Por lo tanto, el objetivo de este estudio fue determinar el comportamiento de recolección de las abejas cuando ambas tanto la grama ciempiés como las plantas dicotiledóneas están disponibles simultáneamente. En 2023, se colocaron macetas con vara de oro de Canadá (Solidago canadensis L.; Asteraceae), arbusto de las mariposas (Buddleja davidii Franch; Scrophulariaceae) y lavanda (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.; Lamiaceae) en céspedes de grama ciempiés en floración que estaban produciendo polen. Las observaciones revelaron que las abejas recolectoras visitaban únicamente las espigas de la hierba ciempiés y no las flores de las plantas dicotiledóneas. En 2024, se colocaron macetas con arbusto de las mariposas y equinácea (Echinacea purpurea [L.] Moench; Asteraceae) sobre la hierba ciempiés entre 1 y 3 días después de la siega. Doce días después de la siega, se recolectaron abejas recolectoras tanto de las espigas de la grama ciempiés como de las flores de las plantas dicotiledóneas. Los resultados indicaron que se recolectó un número significativamente mayor de abejas de las espigas de la grama ciempiés en comparación con las flores de las plantas dicotiledóneas. Las especies de abejas recolectadas en el grama ciempiés fueron Bombus impatiens Cresson (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Melissodes bimaculatus Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Apidae) y Lasioglossum spp. (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), mientras que solo se encontraron Halictus ligatus Say (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) y Lasioglossum en plantas dicotiledóneas. Esto sugiere que el pasto ciempiés en flor es un recurso valioso para las abejas recolectoras, incluso cuando las flores de las plantas dicotiledóneas también son accesibles.

1 Introduction

As urban areas expand and encroach upon natural and rural landscapes, it becomes increasingly essential to identify and optimize existing green spaces to enhance the resources available for diverse pollinators. Habitat degradation resulting from urbanization, alongside intensified landscape management practices such as excessive pesticide use, the proliferation of impervious surfaces, and the consequent heat island effects, has led to a decline in bee populations worldwide, continuing to threaten plant biodiversity (Goulson et al. 2015; Potts et al. 2010). While pollinator conservation efforts have focused on dicotyledonous flowering plants, the importance of grasses, such as centipedegrass (Eremochloa ophiuroides [Munro] Hack.; Poaceae), is often overlooked as a valuable foraging resource for bees (Joseph et al. 2020; Saunders 2018). Understanding how bees utilize these unconventional floral resources is crucial for informing landscape management practices that support a diverse pollinator population (Baldock et al. 2015).

Centipedegrass is a common turfgrass species in the southeastern United States. It requires minimal maintenance and thrives in soils low in nitrogen and phosphorus, while also tolerating acidic soils with pH levels as low as 5.0. This resilience makes it a popular choice in many areas (Islam and Hirata 2005). Turfgrass is mowed frequently (1–4 times a month) from spring to fall to a low height of approximately 5 cm; the more frequent the mowing, the fewer flowers are available (Beard and Green 1994; Patton 2025). Recent studies have shown that Lasioglossum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), along with Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and bees from the genera Bombus (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Melissodes (Hymenoptera: Apidae), and Augochlorella (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), forage on centipedegrass pollen (Jones 2014; Joseph et al. 2020). To date, bees have been reported to forage on the pollen of four commonly grown turfgrasses in the U.S.: centipedegrass (Jones 2014; Joseph et al. 2020), bermudagrass (Bogdan 1962; Erickson and Atmowidjojo 1997; Oertel 1980), bahiagrass (Joseph and Hardin 2022), and red fescue (Festuca rubra L.; Poaceae) (Pojar 1974). Similarly, bumble bees, Bombus impatiens Cresson (Hymenoptera: Apidae), southern carpenter bees, Xylocopa micans Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Apidae), and A. mellifera also were found foraging on sorghum (Sorghum bicolor [L.] Moench; Poaceae) (Harris-Shultz et al. 2025), whereas Bombus pensylvanicus De Geer (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Lasioglossum sp., Melissodes bimaculatus Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Apidae), A. mellifera, and B. impatiens were observed foraging on pearl millet (Cenchrus americanus L., syn. Pennisetum glaucum (L.); Poaceae) (Harris-Shultz et al. 2024). Thus, centipedegrass has the potential to contribute to the ecology of pollinators if managed appropriately.

Dicotyledonous flowering plants are crucial, as they contribute to the protein and energy needs of bees in various ecosystems (Stephen et al. 2024; Vaudo et al. 2020). These plants are common and found in managed and non-managed landscapes in the southern United States. B. impatiens and A. mellifera exhibit floral fidelity, often favoring specific plant types while foraging (Williams et al. 2010). However, recent studies also indicate that Bombus spp. and A. mellifera forage on centipedegrass. This raises the question of whether bees will continue foraging on centipedegrass spikes or shift their focus to a more varied selection of dicotyledonous flowers when both centipedegrass and dicotyledonous flowering plant resources are available simultaneously. The objective of this study was to determine the foraging behavior of bees when presented with pollen resources from both dicotyledonous flowering plants and centipedegrass concurrently. Understanding this bee behavior is crucial in enhancing our knowledge of pollinator ecology within landscapes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

In 2023 and 2024, a study was conducted on centipedegrass lawns in central Georgia, USA, from July to September (Table 1). Four centipedegrass lawns were selected in total, with two lawns in residential and the other two lawns in non-residential (open-field) landscapes. Each site was approximately 10 km apart to minimize cross-visitation and ensure independent bee foraging activity, except for Sites 2 and 4, which were around 2 km apart. The floral density of centipedegrass and dicotyledonous flowers was not quantified. In all sites, centipedegrass inflorescence covered >95 % of the lawns and all the dicotyledonous plant containers were in bloom with multiple inflorescence or flowers when introduced to the lawn. Centipedegrass produces spikes from July to September in central Georgia. A 167.2 m2 area was designated at each lawn site for the study. Site 1 (residential) was managed by the homeowner, who manually irrigated it with a hose and neither fertilized nor treated it with pesticides. Site 2 (non-residential) was located on the University of Georgia Griffin Campus, maintained by facility management, and irrigated daily with a permanent sprinkler system. It was not treated with pesticides. Site 3 (residential) was irrigated with a hose and mowed by a landscaping company; however, no information was available regarding the use of pesticides or fertilizers. Site 4 (non-residential open field) was located on the University of Georgia Griffin Campus and was irrigated every 3 days in 2023; however, no irrigation occurred in 2024. It was fertilized before the study using 32–0–4 (N–P–K) (Scotts Turf Builder Lawn Food, Scotts Miracle-Gro Company, Marysville, Ohio) and treated with the herbicide Celsius™ WG (8.7 % thiencarbazone-methyl, 1.9 % iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium, 57.4 % dicamba; Bayer Environmental Science, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) in both years.

Details of centipedegrass lawns and dates of mowing, setup, and observation for trials in 2023 and 2024.

| Site | GPS coordinates | Trial | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| Observation started | Observation started | Mowing | Plants deployed | Observation started | Mowing | Plants deployed | Observation started | ||

| 1 | 33.267245°N, 84.292229°W | 26 Jul | 14 Aug | 1 Aug | 2 Aug | 12 Aug | 17 Aug | 19 Aug | 26 Aug |

| 2 | 33.197109°N, 84.220127°W | 25 Jul | 14 Aug | 2 Aug | 5 Aug | 12 Aug | 16 Aug | 19 Aug | 26 Aug |

| 3 | 33.187680°N, 84.271065°W | 25 Jul | 14 Aug | 1 Aug | 2 Aug | 12 Aug | 16 Aug | 19 Aug | 26 Aug |

| 4 | 33.263934°N, 84.282609°W | 25 Jul | 14 Aug | 1 Aug | 2 Aug | 12 Aug | 17 Aug | 19 Aug | 26 Aug |

-

Trials 1 and 2 were conducted in 2023, while Trials 3 and 4 took place in 2024. For Trials 1 and 2, dicotyledonous plants were placed on the lawn the same day as the observations, whereas for Trials 3 and 4, the dicotyledonous plants were placed on the lawn 1–3 days after mowing. In 2023, two pots each of butterfly bush, goldenrod, and lavender were used at each site, while in 2024, three pots each of butterfly bush and coneflower were used per site.

The weeds at all four sites were similar and included white clover (Trifolium repens L.; Fabaceae) and dandelions (Taraxacum officinale F.H. Wigg.; Asteraceae). These weeds naturally occurred in the study lawns. The same sites were used during both years. The cultivars of centipedegrass at these sites were unknown.

2.2 Dicotyledonous plants

For various experiments, ‘Fireworks’ goldenrod (Solidago rugosa Mill.; Asteraceae), butterfly bush (Buddleja davidii Franch.; Scrophulariaceae), ‘Royal Velvet English’ lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.; Lamiaceae), and ‘Cheyenne Spirit’ coneflower (Echinacea purpurea [L.] Moench; Asteraceae) were used. The dicotyledonous plants were chosen for their attractiveness to different bee species, their bloom periods that align with centipedegrass flowering, and for their representation of both native and non-native species (Abbate et al. 2024; Garbuzov and Ratnieks 2014; Mawdsley and Carter 2015). Goldenrod and coneflower are native to the United States, while butterfly bush and lavender are non-native (Abbate et al. 2024; Mawdsley and Carter 2015). These plants attract bees, including A. mellifera, Halictus spp. (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), Bombus griseocollis De Geer (Hymenoptera: Apidae), B. impatiens, and B. pensylvanicus (Abbate et al. 2024; Mawdsley and Carter 2015), and they are commonly found in ornamental landscapes throughout the southeastern United States.

The plants used for this study were sourced from local ornamental nurseries. After purchase, the ornamental plants were transported to the Griffin Campus, where they were kept in a shade house receiving 50 % light. Goldenrod and lavender were acquired in 2023 and maintained in the shade house for 6 months before being utilized in experiments. Meanwhile, ‘Cheyenne Spirit’ coneflower was purchased and kept for 3 months in 2024. The butterfly bush was initially purchased in 2023 and reused in 2024. The goldenrod featured bright yellow flowers, while both the butterfly bush and lavender exhibited velvet purple-colored blooms. The coneflowers displayed colors ranging from yellow to orange and red. All the plants were planted in 11.4 L black plastic containers filled with a potting mixture of peat moss, perlite, lime, and gypsum. The plant containers were irrigated daily and fertilized once with 24–8–16 (N–P–K) (Miracle-Gro All Purpose Plant Food, Scotts Miracle-Gro Company, Marysville, Ohio). The coneflower plants were supplemented with Peter’s Professional Peat-Lite Special fertilizer, which has a composition of 20–10–20 (N–P–K) (ICL Specialty Fertilizers, Dublin, Ohio).

2.3 Experiment 1

In 2023, dicotyledonous plant containers were moved to centipedegrass lawn sites on the day of the experiment. Each lawn site received six containers, with two each of goldenrod, butterfly bush, and lavender. Different sets of plants were assigned to each site to ensure the same set was not used at multiple locations. The plant containers were randomly placed at least 6.1 m apart at each site. When introduced, goldenrod, butterfly bush, and lavender had an average of 15, 10, and 12 flower heads per container, respectively. The experiment started 12 days after the lawns were mowed, when the centipedegrass lawns produced spikes and bees began active foraging. At this point, dicotyledonous plant containers were introduced to 167.2 m2 of centipedegrass lawns. Following a 15 min acclimation to allow bees time to recognize the new plants across the turfgrass, bees visiting the centipedegrass spikes and the introduced plant containers were observed for 30 min each. During each session, the lawn was carefully scanned for foraging bees on both the grass spikes and the flowers of the dicotyledonous plants. When bees were seen on either plant, they were collected. Bees were gathered each observation day between 8:00 am and 12:00 pm over a span of 7 days. Generally, bees did not forage on the grass spikes after noon, as spikes do not hold viable pollen after this time (S.V. Joseph, personal communication). All four sites were visited five times during this period, referred to as Trial 1. Plants were watered if needed using the water source at each lawn site during each visit. After 7 days in the field sites, the plant containers were then removed and returned to the greenhouse. This concluded Trial 1. Trial 2 was initiated 7 days post-bee observation period (as part of Trial 1), with lawns in all sites being mowed and all spikes being removed. Twelve days after mowing, the centipedegrass resumed production of spikes and pollen at all four sites. Then the same plant containers were reintroduced into the same lawn sites from the greenhouse. Starting 15 min later, foraging bees were collected daily from the grass spikes and flowers of dicotyledonous plants for the next 7 days, as described for Trial 1. In Trial 2, all four sites were visited six times over 7 days.

The container method was used to collect foraging bees. This approach aimed to minimize damage to the spikes, allowing the plant to be used again in future trials. When foraging bees stayed on a centipedegrass spikelet or a flower of a dicotyledonous plant for at least 3 s, they were captured using a 166.9 mL clear plastic container with a white lid. The container was placed over the bee, and the lid was gently set on top to trap it. The collected bees were transferred to the laboratory, where they were cleaned, washed, and dried before being pinned for identification. Bees were identified to the genus and species level using published keys (Ascher and Pickering 2015; Carril and Wilson 2021).

2.4 Experiment 2

In 2024, dicotyledonous plant containers were placed on the designated lawns after mowing the centipedegrass (within 1–3 days; Table 1), which did not have spikes. In contrast, for Experiment 1, plant containers were added to the centipedegrass lawns approximately 12 days after mowing on the same day observations began, when pollen was readily available to bees.

Six containers, three butterfly bushes, and three coneflowers were transferred to the centipedegrass lawns. Lavender and goldenrod plants were not included in the 2024 experiment. Each butterfly bush averaged eight purple flower heads, while the coneflowers averaged seven flower heads per container. The plants were randomly arranged on the centipedegrass lawns. The spacing between plant containers was consistent with that of Experiment 1, conducted in 2023. The centipedegrass produced spikes and released pollen approximately 10–12 days post-mowing. This lag time allowed the newly placed flowering dicotyledonous plants to integrate into the landscape before the experiment commenced. Once the centipedegrass spikes emerged (approximately 12 days after dicotyledonous plant placement), a 30 min observation was conducted for each floral resource type (the grass and the container plants); bees were collected, curated, and identified as outlined in Experiment 1. Observations were done daily for 12 days. Plants were watered as needed using the water source at each lawn site.

From the initial mowing and immediate placement of plant containers to the end of the observations (approximately 24 days) is referred to as Trial 3. Twelve days after the last observation of Trial 3, the plant containers were set aside on the edges of the lawns and the lawns at all four sites were mowed and all spikes were removed. The plant containers were reintroduced to their previous spots after mowing each lawn at all four sites. This marks the beginning of Trial 4. The observation protocol is the same as that described in Trial 3.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using R Studio software (RStudio, PBC, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). The bee data for each trial in Experiments 1 and 2 were subjected to paired t tests as the data involved paired observations from the same sites, comparing two plant types (flowering centipedegrass and dicotyledonous plants). The lawn sites were replications for each treatment. The statistical significances were determined at α = 0.05. Means and standard errors were calculated.

3 Results

The results indicate that four bee species foraged on pollen from centipedegrass. Of the four species, three were native to our study region (B. impatiens, M. bimaculatus, and Halictus ligatus Say [Hymenoptera: Halictidae]) and one was introduced (A. mellifera). Meanwhile, only two native bee taxa (Lasioglossum spp. and H. ligatus) also foraged on the container dicotyledonous plants. All bee taxa observed collecting pollen from centipedegrass were common, abundant, and widely distributed across the eastern United States (Carril and Wilson 2021).

3.1 Experiment 1

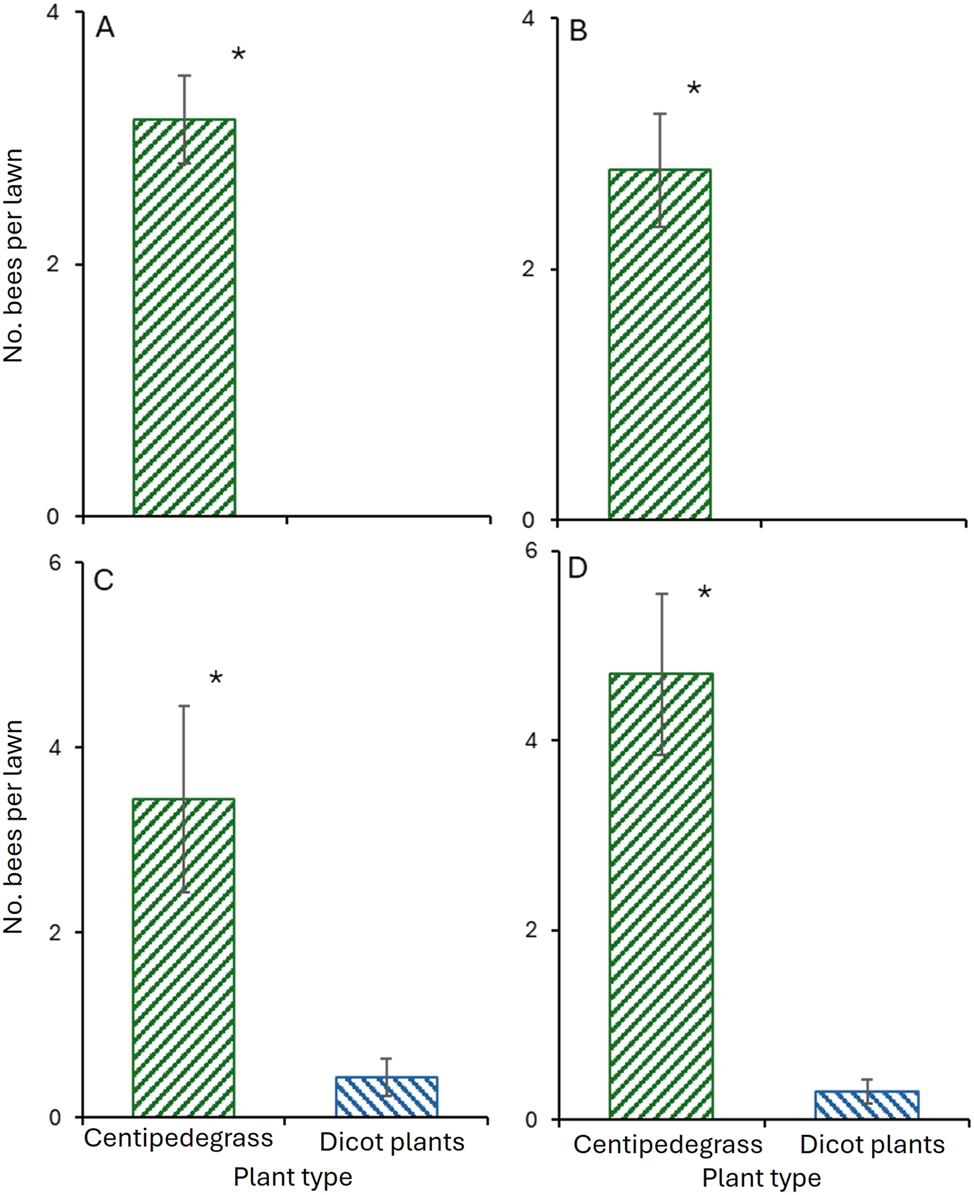

In 2023, a total of 130 bees were captured while foraging on centipedegrass spikes, including 75 B. impatiens, 28 Lasioglossum spp., 24 A. mellifera, and three M. bimaculatus (Table 2). No bees were recorded visiting goldenrod, butterfly bush, or lavender. Significantly more foraging bees were collected from centipedegrass spikes than from dicotyledonous plants in Trial 1 (t = 5.7; df = 19; p < 0.001; Figure 1A) and Trial 2 (t = 6.2; df = 23; p < 0.001; Figure 1B).

Details of bee species collected on flowering centipedegrass in 2023.

| Trial | Site | Bombus impatiens | Apis mellifera | Lasioglossum spp. | Melissodes bimaculatus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| 1 | 2 | 14 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 17 | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 2 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

-

No bees were collected from dicotyledonous flowering plants deployed in 2023. Dicotyledonous plants included were goldenrods, butterfly bushes, and lavenders.

Number of bees collected on flowering centipedegrass and dicotyledonous (dicot) plants (mean ± SE) in (A) Trial 1, (B) Trial 2 in 2023, and (C) Trial 3, and (D) Trial 4 in 2024. Asterisk (*) above the bars indicates a significant difference (paired t test, p < 0.05).

3.2 Experiment 2

In 2024, a total of 149 bees were captured on centipedegrass; 98 B. impatiens, 27 Lasioglossum spp., and 24 A. mellifera were observed foraging on centipedegrass lawns, whereas 13 bees, 10 H. ligatus, and three Lasioglossum spp. were recorded visiting butterfly bush and coneflower (Table 3). The number of bees collected from centipedegrass was significantly greater than that from flowers of dicotyledonous plants in Trial 3 (t = 2.9; df = 16.2; p < 0.001; Figure 1C) and Trial 4 (t = 5.1; df = 19.8; p < 0.001; Figure 1D).

Details of bee species collected on flowering centipedegrass and dicotyledonous (dicot) plants in 2024.

| Trial | Site | Bombus impatiens | Apis mellifera | Lasioglossum spp. | Halictus ligatus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centipedegrass | Dicota | Centipedegrass | Dicot | Centipedegrass | Dicot | Centipedegrass | Dicot | ||

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 21 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 4 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | 2 | 27 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

-

aDicotyledonous plants included were butterfly bushes and coneflowers.

4 Discussion

The results indicated that B. impatiens, A. mellifera, Lasioglossum spp., and M. bimaculatus foraged on centipedegrass pollen, while Lasioglossum spp. and H. ligatus foraged on dicotyledonous plants when both were flowering simultaneously. The foraging behaviors of bees on centipedegrass pollen, especially in B. impatiens, were unaffected by the presence of dicotyledonous flowering plants in the same lawn. The dicotyledonous flowering plants, goldenrod, butterfly bush, lavender, and coneflower featured more conspicuous and larger blooms than the spikes of centipedegrass; nonetheless, bees did not prefer to forage on them in our experiments. Additionally, between the short- and long-term periods of deployment of dicotyledonous plants (Experiment 1 versus 2) in a centipedegrass lawn when both dicotyledonous and centipedegrass plants were in bloom simultaneously, we consistently observed more bee foraging activity in centipedegrass spikes than in dicotyledonous flowers within the lawn. This finding clearly challenges the widespread belief that grass lawns provide limited floral resources for pollinators. Nevertheless, the maintenance of centipedegrass lawns should indeed be adjusted to encourage the production of spikes. Previous studies (Jones 2014; Joseph et al. 2020) and current research have consistently demonstrated that centipedegrass lawns begin to generate spikes and pollen 12 days after mowing at the end of summer in Georgia, USA. This timeframe may vary significantly across different locations and could change during other times of the year.

Experiments 1 (2023) and 2 (2024) were conducted with some key differences in the length of time the dicotyledonous plants were in the centipedegrass lawns. No bees were found foraging on dicotyledonous flowers in Experiment 1, but a few bees were foraging on dicotyledonous in Experiment 2. In Experiment 2, H. ligatus and Lasioglossum spp. bees were observed on dicotyledonous plants, but H. ligatus bees were only observed on dicotyledonous plants and not on centipedegrass spikes. H. ligatus are generalists (Brant and Dunlap 2024) that forage on dicotyledonous plants, such as plants in the Asteraceae family (Ginsberg 1984). Additionally, it is unclear whether the use of coneflower plants in Experiment 2 (as opposed to not being used in Experiment 1) attracted H. ligatus and Lasioglossum spp.

It remains uncertain how centipedegrass pollen offers sufficient rewards compared to the larger flowers of dicotyledonous resources in the landscape. However, centipedegrass can produce abundant floral resources when in bloom. This plentiful resource may require less energy for foraging bees to move from spike to spike and gather all the necessary pollen during a specific trip. Centipedegrass serves as a reliable and consistent pollen source for bees when available and in bloom, providing a strong incentive to forage on it instead of dicotyledonous flowers. More research is needed to clarify how the floral abundance hypothesis influences bee foraging behavior, particularly in bumblebees, in this area. Bees may exhibit floral fidelity, where bees consistently forage from a specific plant species on certain days (Williams et al. 2010), as observed in social bees such as B. impatiens and A. mellifera. These species were the dominant types collected from centipedegrass spikes in this study. Floral fidelity enhances foraging efficiency by allowing bees to specialize in handling specific floral morphologies (Garibaldi et al. 2013). Social bees, such as B. impatiens and A. mellifera also forage in cohorts with their nestmates (Grüter 2020; Grüter and Hayes 2022), whom they actively recruit to abundant food sources. Although centipedegrass spikes lack nectar, bees still collect pollen from them. Additionally, centipedegrass produces viable pollen in the morning, which dries out before noon (S.V. Joseph, personal communication). Bees might strategize their foraging trips, first foraging on centipedegrass while available and then switching to other floral resources once its pollen is no longer present. In this study, observations were made solely in the morning when centipedegrass pollen was accessible. Bees may have taken advantage of dicotyledonous floral resources during the afternoon or when the centipedegrass lawns were mowed.

The knowledge about the nutritional content and quality of centipedegrass is limited. It remains uncertain how much variability in nutrient content exists among the surveyed current dicotyledonous plant species and whether this variation impacts the foraging needs of bees, thereby influencing their behavior. Dicotyledonous pollen (e.g., from Fabaceae and Rosaceae) tends to be richer in protein and essential amino acids, while lipid content varies widely (Vaudo et al. 2020). Bees benefit from a mix of pollen types with varying levels of lipid and amino acid content (Chau and Rehan 2024). Thus, additional research is necessary to understand how the nutrient content of pollen relates to bee needs and informs foraging behaviors, facilitating refined conservation efforts to enhance ecosystem health.

Based on the results, lawn management practices for centipedegrass in urban and suburban environments should be modified to enhance pollen availability. In central Georgia, centipedegrass typically produces abundant pollen from July to September, and takes 12 days to begin reflowering after mowing. However, this is based on field observations rather than a study specifically designed to quantify the exact onset of pollen production. Pollen production lasts for 5–10 days. Once most flowers set seeds, bees stop foraging on the centipedegrass lawn. To ensure that bees have access to this pollen resource, the mowing interval should be adjusted to allow sufficient time for pollen to develop and become available for foraging. Centipedegrass usually produces new spikes within 12–14 days after mowing (Joseph et al. 2020). A delay in mowing frequency of 3–4 weeks might provide a window of opportunity for bees to forage on centipedegrass. Rain events, irrigation frequency, and the location of the lawn in the southeastern region could influence the specific timing of emergence and abundance of centipedegrass spikes. More educational events, demonstrations, and media involvement are needed to disseminate this new information, advocating for subtle changes to lawn care practices to convert centipedegrass lawns into more pollinator-friendly environments. Similarly, factors that influence property owners’ perceptions and willingness to modify mowing practices should be investigated. These adjustments to lawn care practices will address the criticism that turfgrasses are biological deserts (NSF Stories 2018).

Although turfgrass is often considered a biological desert, centipedegrass produces pollen in late summer, offering a valuable foraging resource for pollinators at a time when other sources, such as tree pollen (Schmidt 2016), are limited. This is especially important for bumblebee colonies, as they require large amounts of pollen resources during late summer to support the development of overwintering queens (Goulson et al. 2008). Maintaining diverse floral resources for bees is essential, although bees selectively forage based on the macronutrient composition of pollen, particularly protein-to-lipid ratios, which vary widely across plant species (Vaudo et al. 2024). Thus, further research is needed to understand how grass pollen contributes to the diet of bees and their foraging behavior in turfgrass-dominated areas of the southeastern USA.

In summary, our data indicated that various species of bees, primarily B. impatiens, Lasioglossum spp., M. bimaculatus and A. mellifera, foraged on centipedegrass pollen when dicotyledonous flowering plants were present in the landscape. This suggests that grass-dominated landscapes can provide ecological benefits for enhancing urban pollinator conservation. The current study was conducted only in central Georgia; therefore, future studies on a larger regional scale, incorporating other geographical locations and expanding to include other turfgrass species such as zoysiagrass, would be beneficial. Our study is one of the few that has documented bees use of turfgrass (Jones 2014; Joseph et al. 2020; Pojar 1974). The long-term ecological benefits of flowering grasses, such as centipedegrass, on bee health and ecosystem services to crops remain unclear in urban and suburban areas. Lawn care maintenance practices, including the amount, timing, and frequency of fertilizer and irrigation applications, strongly impact pollen abundance, highlighting the need for further research.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Hardin and A. Chapman for helping with the field experiments and homeowners for volunteering their yards for this research. We also thank C. Fair for helping with the statistical analysis of the data.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This research was supported by USDA ARS Tifton (Agreement 58-6048-0-013), the University of Georgia, the Hatch Project University of Georgia, and support from agrochemical companies.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

Abbate, A.P., Campbell, J.W., Grodsky, S.M., and Williams, G.R. (2024). Assessing the attractiveness of native wildflower species to bees (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) in the southeastern United States. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 5: e12363, https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.12363.Search in Google Scholar

Ascher, J.S., and Pickering, J. (2015). Discover Life bee species guide and world checklist (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila), Available at: https://www.discoverlife.org (Accessed 24 October 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Baldock, K.C.R., Goddard, M.A., Hicks, D.M., Kunin, W.E., Mitschunas, N., Osgathorpe, L.M., Potts, S.G., Robertson, K.M., Scott, A.V., Stone, G.N., et al.. (2015). Where is the UK’s pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower-visiting insects. Proc. Royal Soc. B.: Biol. Sci. 282: 20142849, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2849.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Beard, J.B., and Green, R.L. (1994). The role of turfgrasses in environmental protection and their benefits to humans. J. Environ. Qual. 23: 452–460, https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq1994.00472425002300030007x.Search in Google Scholar

Bogdan, A.V. (1962). Grass pollination by bees in Kenya. Proc. Linnean Soc. London 173: 57–61, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1962.tb01326.x.Search in Google Scholar

Brant, R.A., and Dunlap, A.S. (2024). From metropolis to wilderness: uncovering pollen collecting behavior in urban and wild sweat bees (Halictus ligatus). Urban Ecosyst. 27: 563–575, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-023-01466-1.Search in Google Scholar

Carril, O.M., and Wilson, J.S. (2021). The bees in your backyard: a guide to North America’s bees. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.Search in Google Scholar

Chau, K.D., and Rehan, S.M. (2024). Nutritional profiling of common eastern North American pollen species with implications for bee diet and pollinator health. Apidologie 55: 9, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-023-01054-4.Search in Google Scholar

Erickson, E.H., and Atmowidjojo, A.H. (1997). Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon) as a pollen resource for honey bee colonies in the Lower Colorado River agroecosystem. Apidologie 28: 57–62, https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:19970201.10.1051/apido:19970201Search in Google Scholar

Garbuzov, M., and Ratnieks, F.L.W. (2014). Quantifying variation among garden plants in attractiveness to bees and other flower-visiting insects. Funct. Ecol. 28: 364–374, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12178.Search in Google Scholar

Garibaldi, L.A., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Winfree, R., Aizen, M.A., Bommarco, R., Cunningham, S.A., Kremen, C., Carvalheiro, L.G., Harder, L.D., Afik, O., et al.. (2013). Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 339: 1608–1611, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ginsberg, H.S. (1984). Foraging behavior of the bees Halictus ligatus (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) and Ceratina calcarata (Hymenoptera: Anthophoridae): foraging speed on early-summer composite flowers. J. N.Y. Entomol. Soc. 92: 162–168.Search in Google Scholar

Goulson, D., Lye, G.C., and Darvill, B. (2008). Decline and conservation of bumble bees. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 53: 191–208, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093454.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Goulson, D., Nicholls, E., Botías, C., and Rotheray, E.L. (2015). Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347: 1255957, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255957.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Grüter, C. (2020). Recruitment and communication in foraging. In: Stingless bees. Fascinating life sciences. Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-030-60090-7Search in Google Scholar

Grüter, C., and Hayes, L. (2022). Sociality is a key driver of foraging ranges in bees. Curr. Biol. 32: 5390–5397, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.10.064.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Harris-Shultz, K., Armstrong, J., Sapkota, S., Knoll, J., and Clem, C.S. (2025). Insect pollinivores of Sorghum bicolor and plant traits that influence visitation. J. Entomol. Sci. 60: 305–321, https://doi.org/10.18474/jes24-57.Search in Google Scholar

Harris-Shultz, K.R., O’Hearn, J.S., Knoll, J., and Clem, C.S. (2024). Insects foraging on pearl millet, Cenchrus americanus, pollen. J. Entomol. Sci. 59: 506–514, https://doi.org/10.18474/jes23-91.Search in Google Scholar

Islam, M.A., and Hirata, M. (2005). Centipedegrass (Eremochloa ophiuroides (Munro) Hack.): growth behavior and multipurpose usages. Grassland Sci. 51: 183–190, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-697X.2005.00014.x.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, T.M. (2014). Why is the lawn buzzing? Evidence of pollinators foraging on centipedegrass inflorescences. Biodiv. Data J. 2: e1101, https://doi.org/10.3897/bdj.2.e1101.Search in Google Scholar

Joseph, S.V., and Hardin, C.B. (2022). Bees forage on bahiagrass spikes. Fla. Entomol. 105: 95–98, https://doi.org/10.1653/024.105.0115.Search in Google Scholar

Joseph, S.V., Harris-Shultz, K., and Jespersen, D. (2020). Evidence of pollinators foraging on centipedegrass inflorescences. Insects 11: 795, https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11110795.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mawdsley, J.R. and Carter, C.M. (2015). Urban populations of a declining bumble bee species, Bombus pensylvanicus (De Geer) (Hymenoptera: Apidae), in the District of Columbia, USA. Maryland Entomol. 6: 22–29.Search in Google Scholar

NSF (National Science Foundation) Stories. (2018). Are our lawns biological deserts? Available at: https://www.nsf.gov/news/are-our-lawns-biological-deserts (Accessed 24 October 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Oertel, E. (1980). Nectar and pollen plants. Beekeeping in the United States. In: United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture handbook, Vol. 335, pp. 16–23.Search in Google Scholar

Patton, A.J. (2025). Why mow?: A review of the resulting ecosystem services and disservices from mowing turfgrass. Crop Sci. 65: e21376, https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.21376.Search in Google Scholar

Pojar, J. (1974). Relation of the reproductive biology of plants to the structure and function of four plant communities, Dissertation thesis. University of British Columbia, Canada.Search in Google Scholar

Potts, S.G., Biesmeijer, J.C., Kremen, C., Neumann, P., Schweiger, O., and Kunin, W.E. (2010). Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts, and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25: 345–353, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Saunders, M.E. (2018). Insect pollinators collect pollen from wind-pollinated plants: implications for pollination ecology and sustainable agriculture. Insect Conserv. Divers. 11: 13–31, https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12243.Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt, C.W. (2016). Pollen overload: seasonal allergies in a changing climate. Environ. Health Perspect. 124: A70–A75, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.124-A70.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Stephen, K.W., Chau, K.D., and Rehan, S.M. (2024). Dietary foundations for pollinators: nutritional profiling of plants for bee health. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8: 1411410, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1411410.Search in Google Scholar

Vaudo, A.D., Dyer, L.A., and Leonard, A.S. (2024). Pollen nutrition structures bee and plant community interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121: e2317228120, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2317228120.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Vaudo, A.D., Tooker, J.F., Patch, H.M., Biddinger, D.J., Coccia, M., Crone, M.K., Fiely, M., Francis, J.S., Hines, H.M., Hodges, M., et al.. (2020). Pollen protein: lipid macronutrient ratios may guide broad patterns of bee species floral preferences. Insects 11: 132, https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11020132.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Williams, N.M., Crone, E.E., Roulston, R.L.T., Minckley, R.L., Packer, L., and Potts, S.G. (2010). Ecological and life-history traits predict bee species responses to environmental disturbances. Biol. Conserv. 143: 2280–2291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.03.024.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Florida Entomological Society

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Life history descriptions of two aquatic Florida moth species (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Higher Apoidea activity on centipedegrass lawns than on dicotyledonous plants

- Dynamics of citrus pest populations following a major freeze in northern Florida

- Control of Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae) by trapping with banana vinegar

- Establishment, distribution, and preliminary phenological trends of a new planthopper in the genus Patara (Hemiptera: Derbidae) in South Florida, United States of America

- Comparative evaluation of the infestation of five varieties of citrus by the larvae of Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae)

- Impact of land use on the density of Bulimulus bonariensis (Stylommatophora: Bulimulidae) and its parasitic mite, Austreynetes sp. (Trombidiformes: Ereynetidae)

- First record of native seed beetle Stator limbatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on invasive earleaf acacia in Florida

- Establishment and monitoring of a sentinel garden of Asian tree species in Florida to assess potential insect pest risks

- Parasitism of Halyomorpha halys and Nezara viridula (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) sentinel eggs in Central Florida

- Genetic differentiation of three populations of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in Mexico

- Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) associated with blueberry cultivation in Central Mexico

- First report of Phidotricha erigens (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Epipaschiinae) injuring mango inflorescences in Puerto Rico

- Seed predation of Sabal palmetto, Sabal mexicana and Sabal uresana (Arecaceae) by the bruchid Caryobruchus gleditsiae (Coleoptera: Bruchidae), with new host and distribution records

- Genetic variation of rice stink bugs, Oebalus spp. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) from Southeastern United States and Cuba

- Selecting Coriandrum sativum (Apiaceae) varieties to promote conservation biological control of crop pests in south Florida

- First record of Mymarommatidae (Hymenoptera) from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador

- First field validation of Ontsira mellipes (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) as a potential biological control agent for Anoplophora glabripennis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in South Carolina

- Field evaluation of α-copaene enriched natural oil lure for detection of male Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in area-wide monitoring programs: results from Tunisia, Costa Rica and Hawaii

- Abundance of Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagnall) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and other thrips in commercial snap bean fields in the Homestead Agricultural Area (HAA)

- Performance of Salvinia molesta (Salviniae: Salviniaceae) and its biological control agent Cyrtobagous salviniae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in freshwater and saline environments

- Natural arsenal of Magnolia sarcotesta: insecticidal activity against the leaf-cutting ant Atta mexicana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

- Ethanol concentration can influence the outcomes of insecticide evaluation of ambrosia beetle attacks using wood bolts

- Post-release support of host range predictions for two Lygodium microphyllum biological control agents

- Missing jewels: the decline of a wood-nesting forest bee, Augochlora pura (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), in northern Georgia

- Biological response of Rhopalosiphum padi and Sipha flava (Hemiptera: Aphididae) changes over generations

- Argopistes tsekooni (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a new natural enemy of Chinese privet in North America: identification, establishment, and host range

- A non-overwintering urban population of the African fig fly (Diptera: Drosophilidae) impacts the reproductive output of locally adapted fruit flies

- Fitness of Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) on four economically important host fruits from Fujian Province, China

- Carambola fruit fly in Brazil: new host and first record of associated parasitoids

- Establishment and range expansion of invasive Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Phycitinae) in Texas

- A micro-anatomical investigation of dark and light-adapted eyes of Chilades pandava (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)

- Scientific Notes

- Evaluation of food attractants based on fig fruit for field capture of the black fig fly, Silba adipata (Diptera: Lonchaeidae)

- Exploring the potential of Amblyseius largoensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a biological control agent against Aceria litchii (Acari: Eriophyidae) on lychee plants

- Early stragglers of periodical cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) found in Louisiana

- Attraction of released male Mediterranean fruit flies to trimedlure and an α-copaene-containing natural oil: effects of lure age and distance

- Co-infestation with Drosophila suzukii and Zaprionus indianus (Diptera: Drosophilidae): a threat for berry crops in Morelos, Mexico

- Observation of brood size and altricial development in Centruroides hentzi (Arachnida: Buthidae) in Florida, USA

- New quarantine cold treatment for medfly Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in pomegranates

- A new invasive pest in Mexico: the presence of Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in chili pepper fields

- Acceptance of fire ant baits by nontarget ants in Florida and California

- Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

- Note on the nesting biology of Epimelissodes aegis LaBerge (Hymenoptera: Apidae)

- Mass rearing protocol and density trials of Lilioceris egena (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a biological control agent of air potato

- Cardinal predation of the invasive Jorō spider Trichophila clavata (Araneae: Nephilidae) in Georgia

- Book Reviews

- Review: Harbach, R.E. 2024. The Composition and Nature of the Culicidae (Mosquitoes). Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International and the Royal Entomological Society, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781800627994

- Retraction

- Retraction of: Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Life history descriptions of two aquatic Florida moth species (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Higher Apoidea activity on centipedegrass lawns than on dicotyledonous plants

- Dynamics of citrus pest populations following a major freeze in northern Florida

- Control of Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae) by trapping with banana vinegar

- Establishment, distribution, and preliminary phenological trends of a new planthopper in the genus Patara (Hemiptera: Derbidae) in South Florida, United States of America

- Comparative evaluation of the infestation of five varieties of citrus by the larvae of Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae)

- Impact of land use on the density of Bulimulus bonariensis (Stylommatophora: Bulimulidae) and its parasitic mite, Austreynetes sp. (Trombidiformes: Ereynetidae)

- First record of native seed beetle Stator limbatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on invasive earleaf acacia in Florida

- Establishment and monitoring of a sentinel garden of Asian tree species in Florida to assess potential insect pest risks

- Parasitism of Halyomorpha halys and Nezara viridula (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) sentinel eggs in Central Florida

- Genetic differentiation of three populations of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in Mexico

- Tortricidae (Lepidoptera) associated with blueberry cultivation in Central Mexico

- First report of Phidotricha erigens (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Epipaschiinae) injuring mango inflorescences in Puerto Rico

- Seed predation of Sabal palmetto, Sabal mexicana and Sabal uresana (Arecaceae) by the bruchid Caryobruchus gleditsiae (Coleoptera: Bruchidae), with new host and distribution records

- Genetic variation of rice stink bugs, Oebalus spp. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) from Southeastern United States and Cuba

- Selecting Coriandrum sativum (Apiaceae) varieties to promote conservation biological control of crop pests in south Florida

- First record of Mymarommatidae (Hymenoptera) from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador

- First field validation of Ontsira mellipes (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) as a potential biological control agent for Anoplophora glabripennis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in South Carolina

- Field evaluation of α-copaene enriched natural oil lure for detection of male Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in area-wide monitoring programs: results from Tunisia, Costa Rica and Hawaii

- Abundance of Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagnall) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and other thrips in commercial snap bean fields in the Homestead Agricultural Area (HAA)

- Performance of Salvinia molesta (Salviniae: Salviniaceae) and its biological control agent Cyrtobagous salviniae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in freshwater and saline environments

- Natural arsenal of Magnolia sarcotesta: insecticidal activity against the leaf-cutting ant Atta mexicana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

- Ethanol concentration can influence the outcomes of insecticide evaluation of ambrosia beetle attacks using wood bolts

- Post-release support of host range predictions for two Lygodium microphyllum biological control agents

- Missing jewels: the decline of a wood-nesting forest bee, Augochlora pura (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), in northern Georgia

- Biological response of Rhopalosiphum padi and Sipha flava (Hemiptera: Aphididae) changes over generations

- Argopistes tsekooni (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a new natural enemy of Chinese privet in North America: identification, establishment, and host range

- A non-overwintering urban population of the African fig fly (Diptera: Drosophilidae) impacts the reproductive output of locally adapted fruit flies

- Fitness of Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) on four economically important host fruits from Fujian Province, China

- Carambola fruit fly in Brazil: new host and first record of associated parasitoids

- Establishment and range expansion of invasive Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Phycitinae) in Texas

- A micro-anatomical investigation of dark and light-adapted eyes of Chilades pandava (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)

- Scientific Notes

- Evaluation of food attractants based on fig fruit for field capture of the black fig fly, Silba adipata (Diptera: Lonchaeidae)

- Exploring the potential of Amblyseius largoensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a biological control agent against Aceria litchii (Acari: Eriophyidae) on lychee plants

- Early stragglers of periodical cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) found in Louisiana

- Attraction of released male Mediterranean fruit flies to trimedlure and an α-copaene-containing natural oil: effects of lure age and distance

- Co-infestation with Drosophila suzukii and Zaprionus indianus (Diptera: Drosophilidae): a threat for berry crops in Morelos, Mexico

- Observation of brood size and altricial development in Centruroides hentzi (Arachnida: Buthidae) in Florida, USA

- New quarantine cold treatment for medfly Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in pomegranates

- A new invasive pest in Mexico: the presence of Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in chili pepper fields

- Acceptance of fire ant baits by nontarget ants in Florida and California

- Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

- Note on the nesting biology of Epimelissodes aegis LaBerge (Hymenoptera: Apidae)

- Mass rearing protocol and density trials of Lilioceris egena (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a biological control agent of air potato

- Cardinal predation of the invasive Jorō spider Trichophila clavata (Araneae: Nephilidae) in Georgia

- Book Reviews

- Review: Harbach, R.E. 2024. The Composition and Nature of the Culicidae (Mosquitoes). Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International and the Royal Entomological Society, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781800627994

- Retraction

- Retraction of: Examining phenotypic variations in an introduced population of the invasive dung beetle Digitonthophagus gazella (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)