Abstract

Although vertically integrated agricultural industry organizations play a crucial role in bridging the gap between smallholders and large markets, the uneven distribution of benefits within such organizations remains a challenge. Drawing on decades of agricultural reform in China, a quasi-integrated organizational model has emerged that preserves farmers’ autonomy in production and management while achieving factor integration through contractual services, thereby enhancing production efficiency. This study uses household-level data (n = 1,876) collected between 2015 and 2022 from five major agricultural provinces – Jilin, Liaoning, Shandong, Henan, and Sichuan – to examine the heterogeneous effects of quasi-integrated organizations on farm efficiency through a Multinomial Choice Model. The findings indicate that participation in quasi-integrated organizations significantly improves production efficiency, particularly among cash-crop growers, farmers in eastern and central regions, and those without prior technical training. These results suggest that governments should adopt targeted and differentiated agricultural policies to promote scientific management and optimize labor allocation.

1 Introduction

The institutional evolution of China’s rural industrial economy began with the establishment of agricultural production cooperatives in the 1950s, with the collectivization of agricultural production materials in 1956 as an important institutional turning point. Its core goal is to improve the efficiency of factor allocation through the organization of agricultural production, and provide primitive accumulation for the national industrialization strategy (Zhou et al., 2021). However, the excessive emphasis on collective unified management during the planned economy period objectively suppressed the production enthusiasm of micro entities, resulting in a loss of agricultural production efficiency. The rural reforms initiated at the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee in 1978 introduced a dual management system based on the household contract responsibility system, combining centralized and decentralized governance. This institutional innovation preserved the collective planning function on the dimension of “integration,” enabling the system to leverage organizational advantages in disaster prevention and mitigation, rural community building (Gao et al., 2021), and the development of market-linkage mechanisms (Kong, 2020). On the dimension of “division,” by granting farmers operational autonomy, a production mechanism aligned with household-level productivity was established, thereby effectively stimulating the market responsiveness of micro entities (Xiao & Ma, 2020).

However, with the acceleration of agricultural modernization, the shortcomings of decentralized and fragmented production models have become increasingly apparent. Small-scale farmers generally demonstrate lower productivity than large-scale operators due to outdated production facilities, limited adoption of modern technologies, and asymmetric access to market information. Yet, under a fully integrated organizational form, smallholders’ autonomy in production and income distribution cannot be fully preserved. Therefore, in promoting the organic integration of smallholders into modern agriculture, the development of quasi-integrated organizations – characterized by “moderate closeness and flexible participation” – offers a more effective way to balance organizational efficiency with the protection of farmers’ rights and interests.

Currently, within the framework of the “Agricultural Power” strategy, further cultivation, innovation, and improvement of quasi-integrated agricultural organizations have become an essential pillar for advancing China’s model of agricultural modernization. On January 12, 2025, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the Comprehensive Rural Revitalization Plan (2024–2027), which explicitly called for deepening agricultural and rural reforms, developing new forms of rural collective economies, and encouraging smallholders to invest in emerging agricultural management entities through land-use rights and other mechanisms. According to statistics from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, by October 2024, China had more than 4 million family farms and 2.14 million legally registered farmer cooperatives. By bridging the gap between smallholders and large markets, quasi-integrated agricultural organizations have significantly enhanced economies of scale and strengthened the competitiveness of the agricultural sector. Against this backdrop, this study examines the mechanisms through which quasi-integrated agricultural organizations influence farmers’ production efficiency, analyzing the efficiency advantages of this “limited cooperation” model of agricultural production, thereby offering new perspectives on the innovative development of modern agricultural organizations.

2 Literature Review

Williamson’s (1997) transaction cost economics serves as the theoretical foundation for the concept of quasi-integration. He posited that the selection of governance structures (market, hierarchy, hybrid) hinges on three pivotal attributes of transactions: asset specificity, uncertainty, and frequency of transactions. In instances where transactions entail moderate to high levels of asset specificity and uncertainty, pure market governance (non-integration) becomes excessively costly due to the substantial risks associated with negotiation, supervision, and breach of contract (“hold-up”). While complete hierarchical governance (integration) can mitigate these risks, it gives rise to issues such as bureaucratic inertia, diminished incentives, and escalating administrative costs. Consequently, the Hybrid Mode – or quasi-integration – came into being, aiming to attain coordination and control capabilities superior to those of the market at a cost lower than that of integration. Ménard (2004) further systematized the theory of “Hybrid Organizations” as the third fundamental governance model that stands in opposition to the market and bureaucracy. He emphasized that quasi integration is an institutionalized cooperative arrangement established between independent entities through formal contracts, relationship norms, partial ownership (such as joint ventures), or specialized investments. Its core lies in managing complex transactions through coordination mechanisms rather than complete hierarchies or price signals. In Europe, the implementation form of agricultural quasi-integration organizations is the common agricultural policy to jointly address issues such as climate change and international market risks (Kyriakopoulos et al., 2023). In China, the implementation form of agricultural quasi-integration organizations is often cooperatives (Huang & Liang, 2007) and contract agriculture (Zhou & Cao, 2002). The comparison of the concepts of integration, quasi-integration, and non-integration is shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of different types of organizations

| Organizational type | Control power | Coordination level | Flexibility | Transaction cost | Risk sharing | Contract type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical integration | Strong | Strong | Weak | High bureaucratic costs | Internal digestion | Rigid |

| Spot market | Weak | Weak | Strong | High negotiation/default costs | One party bears the responsibility | Loose |

| Quasi-integration | Middle | Middle | Middle | Find the equilibrium point | Risk sharing | Relationship |

This article examines the long-term effects of rural industrial economic organizations on farmers’ production efficiency, as well as the mechanisms and pathways for developing and strengthening quasi-integrated agricultural organizations. Existing research has addressed this issue from two main perspectives. First, studies on the productivity effects of agricultural organizations suggest that they can enhance production efficiency by encouraging villagers to invest in shares or lease assets for joint production, thereby leveraging economies of scale in land and other production factors (Wang & Zhang, 2021). In addition, the provision of public goods by the government – such as terraced field construction and the development of digital infrastructure – can indirectly improve farmers’ production efficiency (Tesema, 2022). Second, research on the self-development of agricultural organizations generally distinguishes between exogenous and endogenous development models (Zhou et al., 2021). The exogenous model refers to situations where limited rural financial resources constrain initial investment, requiring higher-level government support to stimulate the growth of collective village economies (Wen et al., 2021), or where governments strengthen rural vocational education and training to enhance farmers’ professional skills, thereby improving efficiency and increasing incomes (Jian, 2025). Among external drivers, agricultural subsidies are particularly important: evidence from the Lingnan region of China shows that subsidies have facilitated the green transformation of citrus cultivation (Li et al., 2023). By contrast, the endogenous model relies on village collective assets. Here, organizations form alliances such as “village–village partnerships” or “village–enterprise collaborations” to promote the rational flow of resources, technologies, talent, and managerial experience, fostering complementary advantages and mutual benefits (Tu, 2021). Endogenous development may also draw on local social capital, mobilizing local human and economic resources to generate internal momentum for growth (Fu, 2023). Evidence from Nicaragua further illustrates this: coffee growers adopting a quasi-integrated agricultural model – featuring unified technical standards, certification, and collective sales – have significantly improved production techniques and product quality, gaining access to premium specialty coffee markets in Europe and North America (Bacon, 2005).

To sum up, although academia has studied the yield increase effect, realization form and development mode of agricultural industrial organizations, there are still the following shortcomings. Second, insufficient attention has been paid to the critical role of village committees in the organization of agricultural industries. In fact, as the main body of grass-roots governance, village committees not only directly participate in the management of collective economic organizations (the chairman is mostly the village party secretary/director) (Kong, 2020) but also play a pivotal role in coordinating the power relations among farmers, cooperatives, and enterprises (Xu & Cui, 2021), which is one of the indispensable multiple subjects in the development of organizations. Third, the existing literature mostly focuses on the overall analysis of traditional agricultural industrial organizations but fails to specifically examine the dominant form of agricultural quasi-integrated organizations. At the practical level in China, the quasi-integration model represented by “company + farmer” and “company + cooperative + farmer” is the mainstream (Liu & Gao, 2014).

Based on this foundation, this article examines the impact of quasi-integrated agricultural organizations on farmers’ production efficiency from three perspectives. First, drawing on first-hand survey data and employing a Multinomial Choice Model, it empirically reveals the differentiated effects of quasi-integrated organizations across three dimensions: crop type, regional variation, and skill level. Second, it explores the dual mechanisms through which quasi-integration continuously influences farmers’ production efficiency. Finally, it offers targeted policy recommendations, providing insights not only for addressing the problem of low productivity among smallholders in China but also for informing agricultural development in other developing countries.

The contributions of this article are as follows: first, by constructing a multidimensional analytical framework that examines the impact of quasi-integrated agricultural organizations on farmers’ production efficiency, the study breaks through traditional efficiency-oriented research paradigms and provides an operational theoretical tool for exploring the organizational pathways of smallholder production. Second, it innovatively reveals the dual mechanisms of the “labor-capital substitution effect” and the “labor allocation optimization effect,” which not only enhances the theoretical framework for connecting smallholders with modern agriculture but also offers insights for agricultural modernization in countries with severe land fragmentation. Finally, the differentiated policy recommendations derived from empirical research transcend the limitations of traditional universal agricultural support, providing a paradigm reference for precise policy implementation in the development of agricultural industries under resource constraints. These findings hold significant value for refining global agricultural transformation theories and guiding agricultural modernization practices in developing countries.

3 Methodology and Analysis

3.1 Theoretical Analysis

3.1.1 Effects of Quasi-Integrated Organizations on Adjusting Agricultural Labor Hours

Quasi-integrated organizations can enhance farmers’ productivity by influencing the allocation of their time devoted to agricultural labor.

First, such organizations possess market-oriented characteristics. In the process of marketization, they establish collective action mechanisms by pooling farmers’ resources (Zhao & Li, 2010), enabling otherwise decentralized producers to better capture market signals and optimize factor allocation (Wang & Kou, 2013). In addition, quasi-integrated organizations encourage farmers to proactively adjust both the intensity of labor input and production strategies, thereby achieving coordinated improvements in production efficiency and market responsiveness while simultaneously reducing market transaction costs.

Second, quasi-integrated organizations have the characteristics of branding. Quasi-integrated organizations can significantly enhance the added value of agricultural products through market channel expansion and brand building. Under the background of Internet + agriculture, the cooperative operation mode is more conducive to resource integration and labor input optimization than independent operation (Dong, 2023), and this organizational advantage forms a positive cycle with brand operation (Gao, 2008).

Third, quasi-integrated organizations are characterized by learning. Quasi-integrated organizations can organize farmers to learn professional skills through technology diffusion and management system embeddedness, thus improving production efficiency. In the transformation of agricultural modernization, scale expansion drives the development of new agricultural organizations, which forces farmers to pay more energy and time to strengthen their learning of agricultural professional skills and adapt to the new business model (Luo & Wang, 2019). In this learning and adaptation process, quasi-integrated organizations can reduce efficiency losses through standardized management (such as pesticide application norms) (Wang et al., 2017a), or improve the overall allocation efficiency through agricultural capital and technical factor input, so as to achieve a jump in production efficiency (Tu, 2022).

Finally, quasi-integrated organizations are also characterized by a strong emphasis on quality. Through branding mechanisms, these organizations drive the upgrading of production management via standardized quality systems, encouraging farmers to intensify labor input in order to safeguard collective reputation (Zhou, 2021). This quality-oriented extension of labor time generates significant productivity gains and has become a core driver of the sustained improvement in agricultural production efficiency (Xu & Li, 2022). When quality standards are aligned with branding strategies aimed at strengthening agriculture, they not only foster industrial clusters with distinctive product advantages (Jiang, 2022) but also create a virtuous cycle of quality premiums and labor efficiency improvements through the organized mobilization of local resources by village collectives.

3.1.2 The Role of Quasi-Integrated Organizations in Changing Labor Levels

Compared with decentralized operation, quasi-integrated organizations realize the large-scale integration of small farmers’ service needs through the joint operation of industrial players, which significantly improves their market bargaining power and reduces the cost of agricultural technology acquisition. This organizational mode not only optimizes the efficiency of labor resource allocation but also activates idle rural labor by expanding the scale of participation, thus forming a systematic improvement of agricultural production efficiency. This role is mainly reflected in the following aspects:

First, quasi-integrated organizations have technical characteristics. The improvement of agricultural mechanization has significantly reduced the dependence of agricultural production on physical strength and promoted the profound change of labor structure. With the transfer of young and middle-aged male labor to non-agricultural fields (Ji & Zhong, 2011), agricultural production gradually presents the characteristics of “aging” and “feminization,” and women, the elderly, and other physically vulnerable groups can participate in agricultural production more widely. This structural change promotes the transformation of the agricultural machinery service supply mode, and makes large- and medium-sized agricultural machinery holders or professional organizations become the main providers of mechanization services. At the same time, agricultural industrialization organizations have not only lowered the threshold for farmers to adopt technology through their mechanization advantages (Xie et al., 2018) but also significantly improved agricultural production efficiency through large-scale services, forming a virtuous cycle mechanism of mutual reinforcement between mechanization promotion and labor structure adjustment. For example, Brazil’s sugarcane processing order agriculture has promoted the substitution of mechanized harvesting for traditional manual burning harvesting. In this case, the sugarcane harvesting period was shortened from 90 to 45 days, and the daily labor time was reduced from 10 to 8 h (Schneider & Niederle, 2010). The spillover of agricultural technology innovation from developed economies is an important source of efficiency for quasi-integrated organizations, which is worth considering for developing countries (Aldieri et al., 2021). Of course, the opposite situation cannot be ignored; for example, the “farm to table” policy in Europe has actually reduced the application of modern biotechnology, affecting the overall welfare of production and consumers (Wesseler, 2022).

Second, quasi-integrated organizations are also characterized by informativeness. The development of information technology is reshaping the allocation of agricultural production factors and has substantially reduced the traditional dependence on young and prime-age male labor. With the widespread use of mobile internet and smart devices, farmers can readily access market information, technical knowledge, and managerial expertise, thereby directly enhancing agricultural productivity (Zhong & Liu, 2021). Empirical studies further demonstrate that agricultural organizations exert a significant positive effect on production efficiency, although different organizational models produce heterogeneous outcomes (Wan et al., 2010). Moreover, informatization and organizational innovation reinforce one another in a mutually promoting mechanism: on the one hand, organizational innovation within agricultural business entities and industrial upgrading fosters higher levels of informatization; on the other hand, informatization functions as a key enabler of agricultural modernization, accelerating its transformation and jointly shaping a co-evolutionary pathway toward improved efficiency.

Third, quasi-integrated organizations have the characteristics of promoting the transformation of family roles. At present, the gender division of labor in traditional agricultural production is undergoing a profound transformation. The innovation of social concepts and the evolution of family structure jointly promote women and the elderly to shift from auxiliary roles to production and management subjects. The development of agricultural organization provides an institutional carrier for this transformation: it strengthens the communication and coordination function through cooperative production (Du & Wang, 2023), which not only enables female labor to break through the traditional labor participation boundary and assume the organizational and management function but also creates a participation space for multiple groups including land-lost farmers through the integration mechanism of “big agriculture” (Sheng, 2024). It is worth noting that women are faced with dual challenges of role reconstruction in the process of organization: they need to achieve economic participation through re-employment, and they need to coordinate family responsibilities and social role conflicts (Wu, 2013), which requires industrial organizations and social support systems to form a synergistic mechanism. This inclusive evolution of labor force structure eventually becomes an important driving force to improve agricultural production efficiency by activating stock human resources and optimizing the allocation of production factors.

Fourth, quasi-integrated organizations are characterized by increased revenue channels. Against the background of the persistent income gap between urban and rural areas in China, the allocation of rural labor force shows obvious structural differentiation: young- and middle-aged males choose to move to cities for higher remuneration based on economic rationality, while women, the elderly, and minors become the main labor force left behind in agriculture due to family role constraints (Yuan, 2014). This spatial reallocation of the labor force actually constitutes a dynamic balance of the coordinated development of urban and rural areas. On the other hand, the innovative development of agricultural industrial organizations not only creates income increase channels for the left-behind groups but also activates the productivity of the stock labor force by reconstructing the rural social management mechanism.

3.2 Model Specification

The core concern of this article is the impact of quasi-integrated agricultural organizations on farmers’ production efficiency, with particular attention to changes in per-mu production costs after participation. Given the inherent limitations and data characteristics of the survey, this study employs a Multinomial Choice Model for empirical analysis. This model is well-suited to capturing differences across multiple levels, thereby providing a more accurate evaluation of how participation in quasi-integrated agricultural organizations affects farmers’ production efficiency. Based on this approach, the regression model is specified as follows:

In this formula, i denotes different farmers, “t” denotes the year of agricultural production, and “Y i ” refers to the agricultural production efficiency of each farmer. The binary variable “treated i ” in the model reflects the status of farmers’ participation in agricultural quasi-integrated organizations (participation = 1, non-participation or other forms = 0). In the model, “a 1” and “a i ” are coefficients to be estimated, which respectively represent the impact of participation in agricultural quasi-integrated organizations and other control variables on the production efficiency of farmers. “a 1” is the intercept term, and “e i ” represents the random disturbance term to capture other uncertain factors not included in the model.

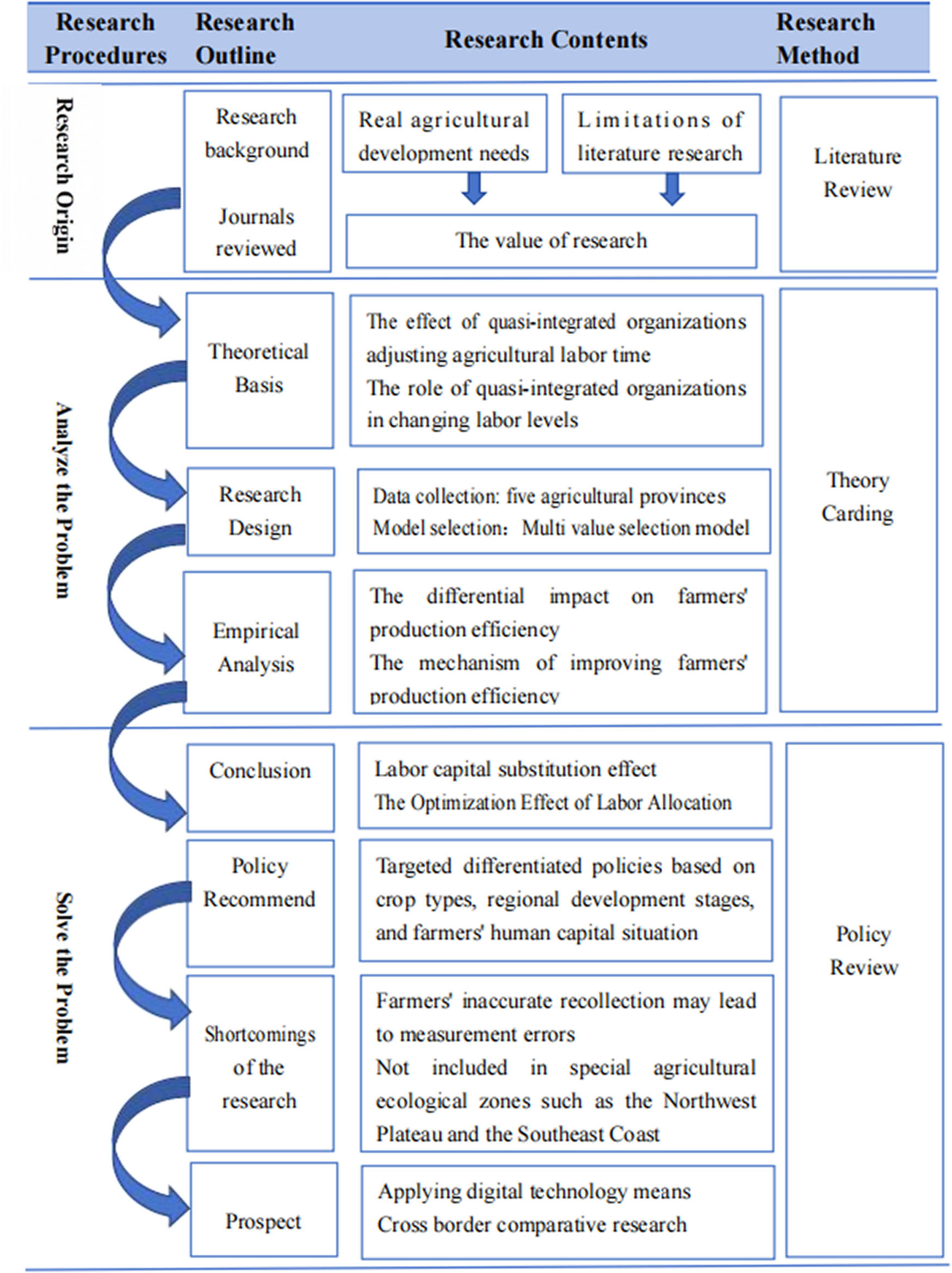

In addition, to control other influencing factors (Adamie et al., 2019), we introduce “x i ,” which represents the i control variable in the model, and these variables include household size, market conditions, and household characteristics. Specifically, as shown in Figure 1, this article conducts research according to this thinking framework.

Study framework.

3.3 Design of Variables

3.3.1 Explained Variable

To accurately measure the impact of agricultural quasi-integration organization on farmers’ production and avoid the questionnaire response bias, this article takes “farmers’ cost input per mu” (Y i ) as the core index to measure production efficiency. The construction of this index refers to the two-dimensional evaluation framework proposed by Wang et al. (2017b) strengthens the cost input dimension on the basis of the traditional agricultural output index, and more comprehensively reflects the improvement effect of the production process. Deng et al.’s (2020) empirical study on the concept of yield per mu further verified the advantage of this index in capturing the optimization effect of resource allocation. Considering the characteristics of farmers’ cost accounting pointed out by Mu et al. (2014) and Jiang et al. (2017), this article uses the gradient variable to measure the “change in cost input per mu”: if farmers’ cost input per mu decreases, it indicates that their production efficiency has improved. Otherwise, it shows that its production efficiency is reduced.

3.3.2 Explanatory Variable

In this study, binary dummy variables are employed as the core explanatory variables to capture farmers’ participation in quasi-integrated agricultural organizations. A value of 1 indicates that farmers have learned about and joined such organizations through channels such as government publicity, neighbor referrals, or agricultural technology exchanges organized by local communities. A value of 0 indicates that the farmer has not joined a quasi-integrated organization. By examining the significance of the coefficients on these dummy variables, the analysis more accurately reflects the actual impact of organizational participation on farmers’ production efficiency.

3.3.3 Control Variable

Based on the theoretical analysis and literature review of the impact of quasi-integrated agricultural organizations on the productivity of farmers, this article identifies the main influencing factors and the role of quasi-integrated agricultural organizations, especially their effects on the improvement of labor hours and labor level. To accurately capture these influencing factors and overcome the problems of omitted variables and selection bias, this study includes a series of control variables in the econometric model (Liang & Yao, 2024; Pham et al., 2021; Ping & Zhang, 2024; Wang & Zhao, 2023; Yuan & Nie, 2024). These variables include the age, gender, education level, risk preference, operation scale, mechanization degree, land property rights, government subsidies, and socialized services of the household head, so as to more comprehensively evaluate the role of other influencing factors and effectively reflect the net effect of production and operation organization on farmers’ income.

3.3.4 Mechanism Variable

This study identifies agricultural labor time and agricultural labor composition as the core mechanism variables. Agricultural labor time is measured as an ordinal variable, based on the survey item: “the proportion of household agricultural labor time in total labor time in recent years,” with responses ranging from lower to higher proportions. Agricultural labor composition is captured using categorical variables, based on the survey item: “the main labor force structure of agricultural operations.” Farmers’ participation in agricultural labor is classified into three categories: (i) family labor, (ii) young- and middle-aged men aged 18–60, and (iii) women, the elderly, and children. Both the quality of the labor force and the number of participants vary accordingly to the assigned values.

3.3.5 Instrumental Variable

To scientifically identify the causal relationship between agricultural quasi-integrated organizations and farmers’ production efficiency, this study uses the instrumental variable method to overcome endogeneity interference, and selects the instrumental variable of “whether to participate in contract agriculture” with national applicability for empirical analysis. Its operational definition is the binary state of farmers arranging production based on contracts signed between themselves or their organizations and purchasers. The scientific basis for selecting this instrumental variable is reflected in: firstly, based on the research evidence of Guo and Liao (2010) and Wang and Xia (2006), it is shown that different regional agricultural organizations (especially cross-regional quasi-integrated organizations) have a universal promoting effect on contract agriculture. Meanwhile, the latest research results of Wang et al. (2025b) on 1968 family farms across the country further confirm that contract models with higher levels of organization can systematically increase the participation rate in contract agriculture, which meets the strong correlation requirements between instrumental variables and core variables. Second, in terms of exogeneity, the participation decisions in contract farming are usually driven by contractual arrangements at the organizational level, and their performance impact is mainly achieved through service collaboration between organizations, rather than individual characteristics of farmers. Therefore, contract agriculture as an instrumental variable has exogenous advantages and is weakly associated with unobservable factors of individual farmers, such as risk preferences and management abilities. The above two aspects jointly demonstrate the theoretical rationality and empirical reliability of contract agriculture as an instrumental variable.

3.4 Data Sources

3.4.1 Areas Studied

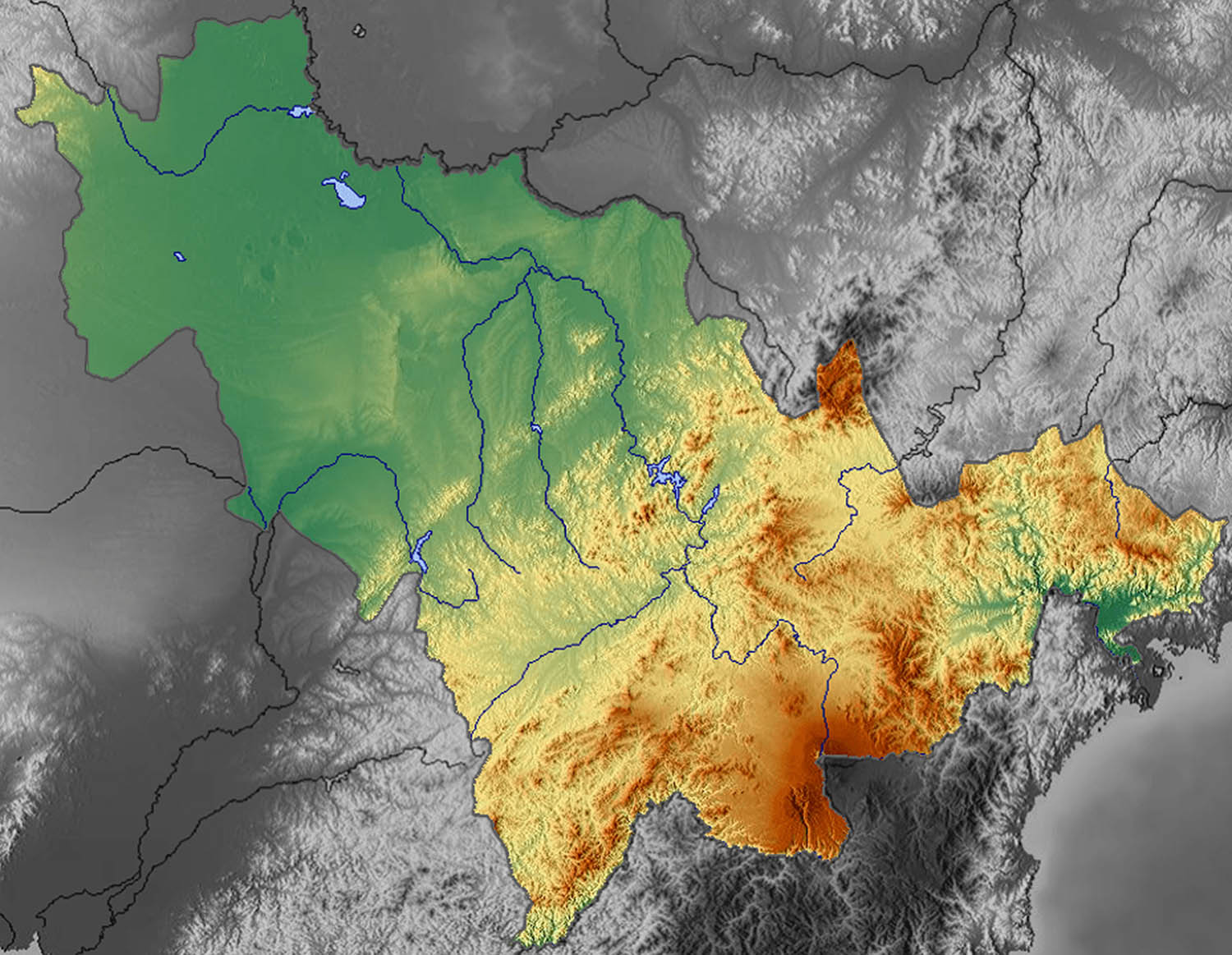

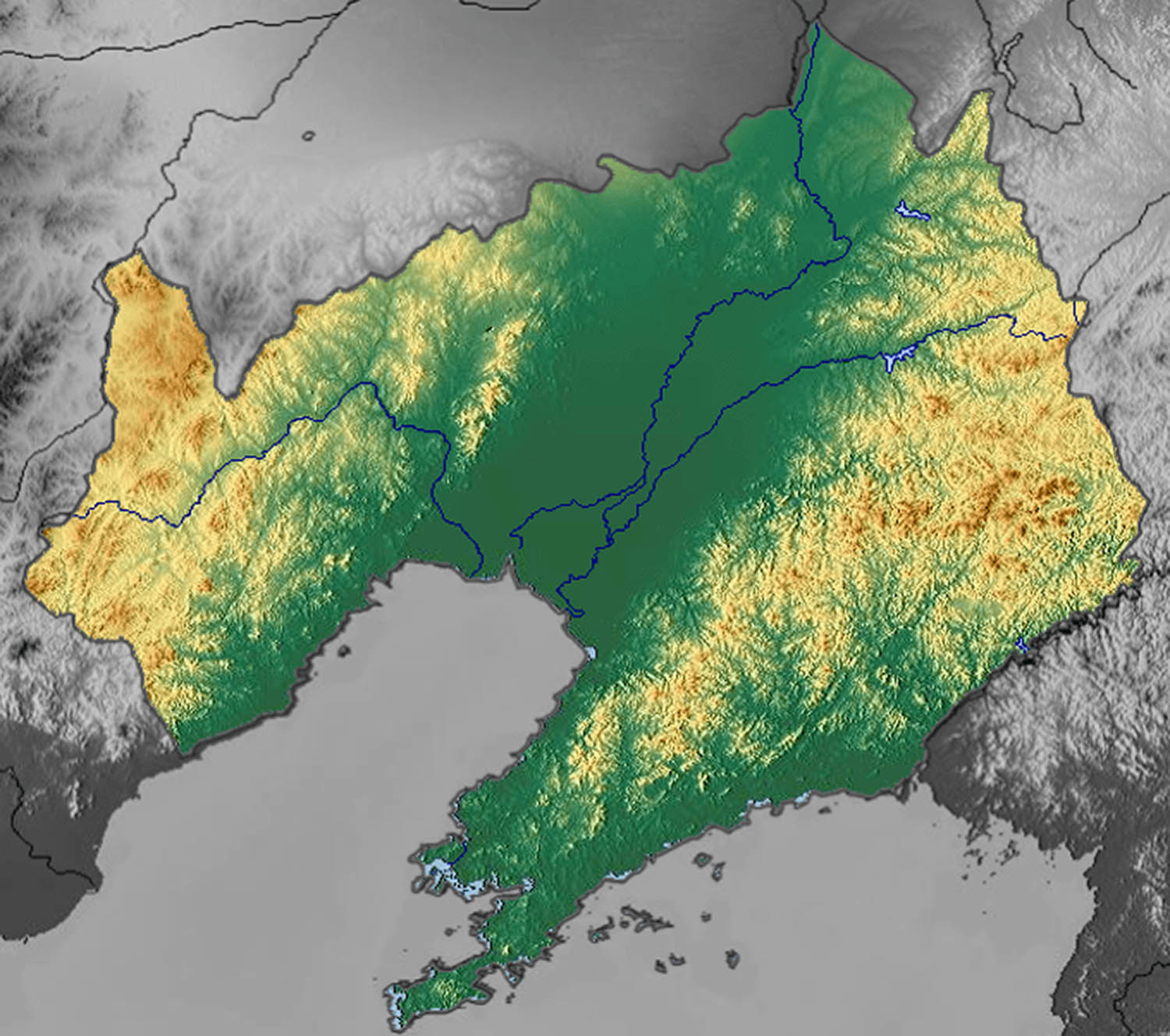

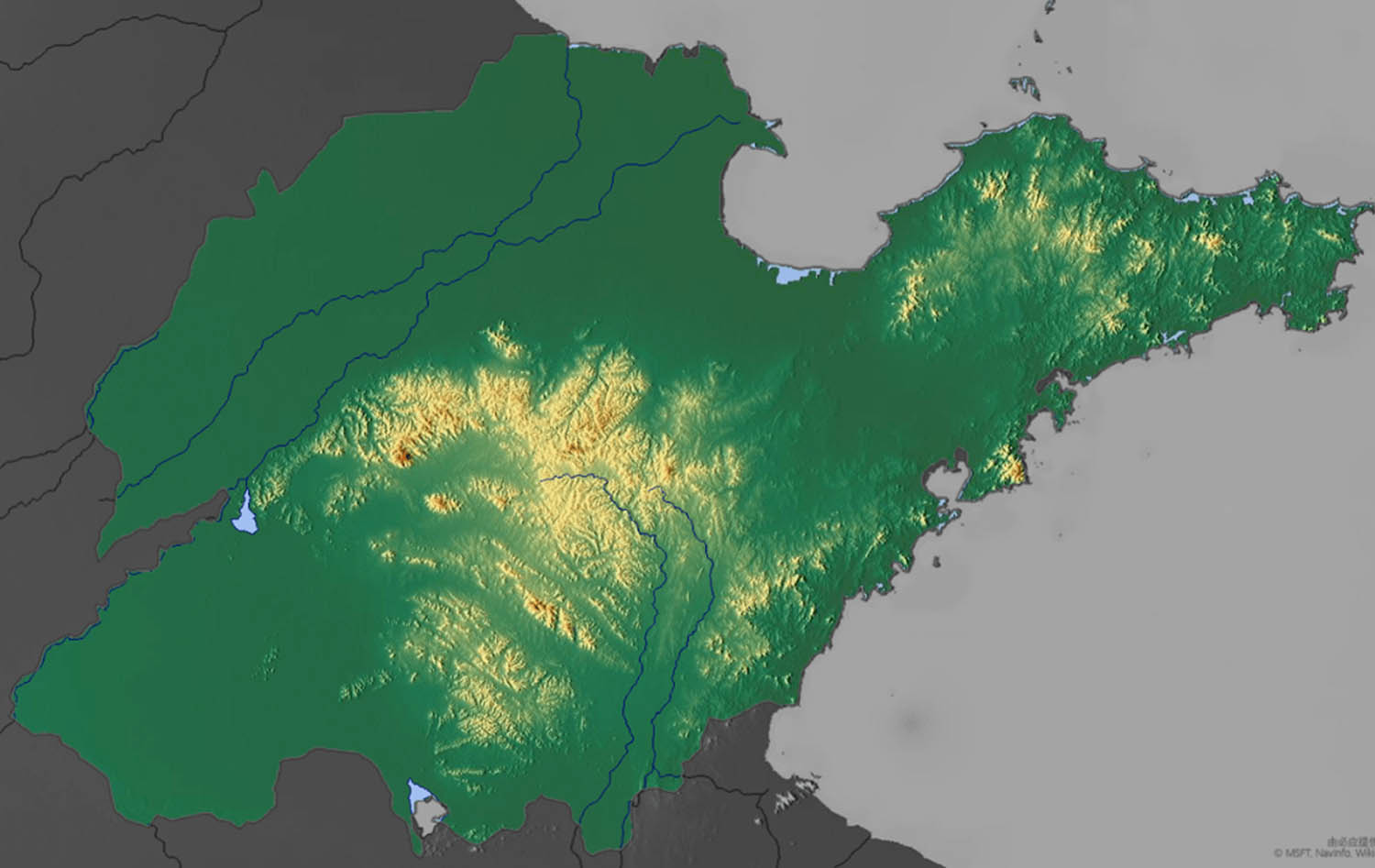

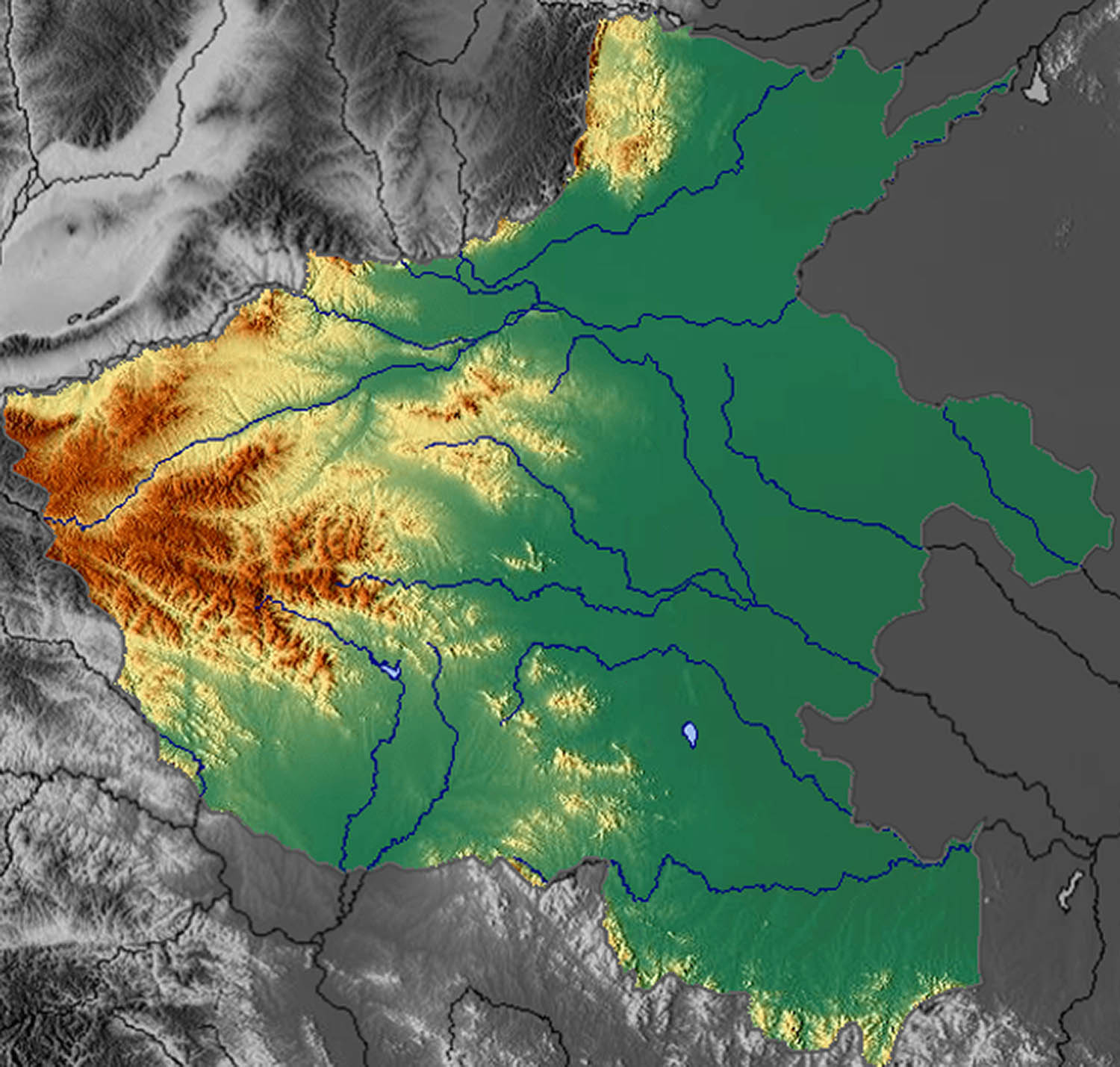

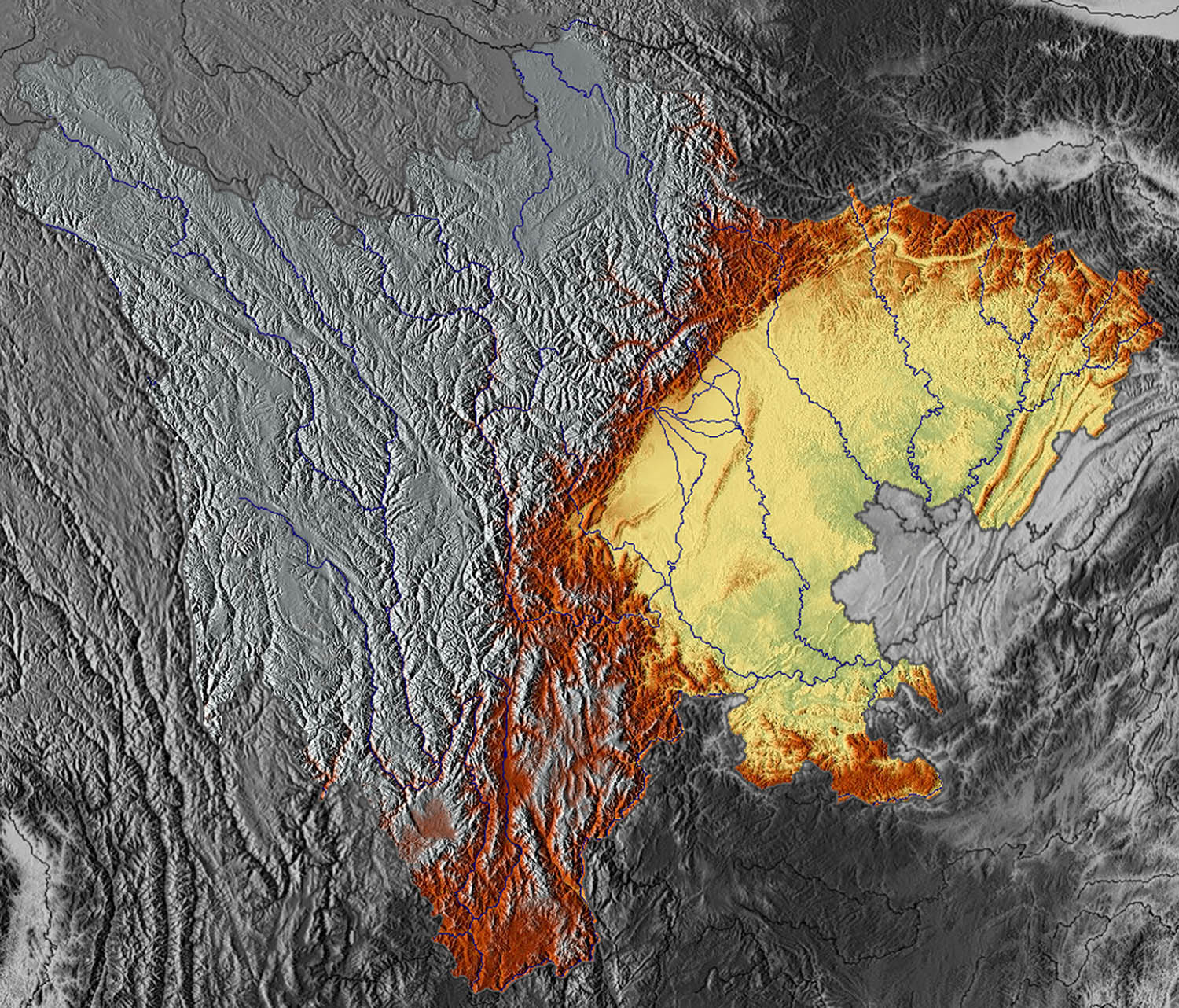

This study selected five provinces, Jilin, Liaoning, Shandong, Henan, and Sichuan, as the core sample, yielding 1,876 valid observations. These provinces span Northeast, North, East, Central, and Southwest China, providing broad geographic coverage. They were chosen not only because they are key regions supporting the national food security strategy but also because their geographic distribution and agricultural production characteristics together offer a representative profile of China’s agricultural diversity. The provinces exhibit both differences and commonalities in production models, allowing for a systematic reflection of the gradient characteristics of national agricultural development. Specifically (Figures 2–6), Jilin is located in the Songnen Plain, Liaoning in the Liaohe Plain, Shandong in the northwestern Shandong Plain, Henan in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, and Sichuan in the Chengdu Plain, a typical alluvial basin. All five regions feature extensive plains or basins, fertile soils (e.g., black soil and alluvial soil), abundant water resources, and favorable conditions for large-scale cultivation. At the same time, they differ in economic foundations, land areas, and climatic conditions (see Table 2 for details), which makes their production structures complementary. For instance, their main agricultural products vary: Henan is dominated by wheat; Jilin by corn and soybeans; Sichuan by rice and tea; Shandong by corn, vegetables, and fruits; and Liaoning by aquatic products, forest fruits, and corn.

Topographic map of Jilin province. Note: Figure is sourced from the website: https://www.sohu.com/a/605452478_121124217.

Topographic map of Liaoning province. Note: Figure is sourced from the website: https://www.sohu.com/a/605452478_121124217.

Topographic map of Shandong province. Note: Figure is sourced from the website: https://www.sohu.com/a/605452478_121124217.

Topographic map of Henan province. Note: Figure is sourced from the website: https://www.sohu.com/a/605452478_121124217.

Topographic map of Sichuan province. Note: Figure is sourced from the website: https://www.sohu.com/a/605452478_121124217.

Basic situation of five provinces in 2024

| Province | Land area (10,000 km²) | Population (10,000 people) | GDP (100 million yuan) | Value-added of three industries (100 million yuan) | Cultivated land area (10,000 ha) | Main crops | Annual precipitation (mm) | Annual temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jilin | 18.74 | 2317.31 | 14361.22 | Primary: 1,589.80; secondary: 4,577.64; tertiary: 8,193.79 | 703 | Rice, corn, soybean, wheat | 810.3 | 6.9 |

| Liaoning | 14.87 | 4,155 | 32612.7 | Primary: 2,565.7; secondary: 11,503.3; tertiary: 18,543.7 | 409.29 | Aquatic products, forest fruits, corn, rice, potatoes, peanuts, soybean | 883 | 10.3 |

| Shandong | 15.81 | 10080.17 | 98,566 | Primary: 6,616.9; secondary: 39,608.6; tertiary: 52,340.3 | 653.93 | Wheat, corn, peanuts, soybean, cotton, rice, Chinese vegetables, fruits | 859.4 | 15.1 |

| Henan | 16.7 | 9,785 | 63589.99 | Primary: 5,491.40; secondary: 24,346.17; tertiary: 33,752.42 | 752.9 | Wheat, corn, cotton, peanuts, sesame | 780.5 | 16.4 |

| Sichuan | 48.6 | 8,364 | 64697.0 | Primary: 5,619.9; secondary: 22,816.9; tertiary: 36,260.2 | 525.26 | Rice, wheat, citrus, rapeseed, tea | 1,000–1,200 | 17 |

3.4.2 Statistical Description of the Sample

In the five agricultural provinces mentioned above, this study examines farmers’ participation in agricultural quasi-integrated organizations and corresponding changes in production efficiency. Descriptive statistics for the main variables in the sample are presented Table 3.[2]

Descriptive statistics

| Variable type | Variable name | Variable description | Mean | Standard deviation | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Change in production efficiency | Change in per mu cost input of farmers: large increase = 5; increase = 4; constant = 3; decrease = 2; substantial decrease = 1 | 2.14 | 0.75 | 1,876 |

| Core explanatory variable | Quasi-integrated organization | Whether joined quasi-agricultural integration organizations: yes = 1; no = 0 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 1,876 |

| Mechanism variable | Agricultural labor time | Proportion of family labor time spent on agriculture in recent years: >90% = 5; 70–90% = 4; 50–70% = 3; 20–50% = 2; <20% = 1 | 3.19 | 1.20 | 1,876 |

| Agricultural labor level | Primary labor structure in agricultural operations: Full-family labor = 3; Young/middle-aged males (18–60) = 2; Women/elderly/children=1 | 2.27 | 0.77 | 1,876 | |

| Control variables | Household head’s age | Actual age of household head (years) | 42.94 | 9.02 | 1,876 |

| Household head’s gender | Gender of household head: male = 1; female = 0 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 1,876 | |

| Education level | Highest education level in household: bachelor+ = 4; high school/vocational = 3; junior high = 2; primary/below = 1 | 2.35 | 0.96 | 1,876 | |

| Risk preference | Farmers’ risk perception in operations: low risk = 3; moderate = 2; high risk = 1 | 2.15 | 0.60 | 1,876 | |

| Operation scale | Farm operation scale (mu): ≥50 = 5; 30–50 = 4; 20–30 = 3; 10–20 = 2; ≤10 = 1 | 1.75 | 1.18 | 1,876 | |

| Mechanization level | Agricultural mechanization level: fully mechanized = 3; partial = 2; manual = 1 | 2.19 | 0.68 | 1,876 | |

| Land property rights | Whether land ownership is confirmed: yes = 1; no = 0 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 1,876 | |

| Government subsidies | Whether received government subsidies: yes = 1; no = 0 | 0.86 | 0.34 | 1,876 | |

| Socialized services | Whether received agricultural socialized services: yes = 1; no = 0 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 1,876 |

Informed consent: This study was exempt from ethical approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee as it involved minimal risk and did not collect identifiable private information. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

4 Results

4.1 Baseline Regression Results

To accommodate the gradient nature of the dependent variable, this study employs both ordered Logit (oLogit) and ordered Probit (oProbit) regression methods for estimation and comparison. The former is suitable for data with uniformly distributed or limited categorical options in the dependent variable, while the latter better aligns with normally distributed variables. The regression results are presented in Table 2. In Models (1) and (3) (without control variables), the effect of organizational participation fails to pass the significance test. However, after incorporating control variables such as household characteristics, operational scale, mechanization level, land tenure rights, and policy support in Models (2) and (4), the organizational participation variable exhibits a statistically significant negative impact on per-mu production costs. This finding aligns with our theoretical hypothesis, suggesting that quasi-integrated agricultural organizations may reduce farmers’ over-reliance on single production factors (e.g., fertilizers or pesticides) through scale economies or technical assistance, thereby lowering per-mu input costs.

The regression results in Table 4 further identify several factors influencing farmers’ production efficiency, including the household head’s age, education level, risk preference, land tenure rights, government subsidies, and access to agricultural extension services. Key findings reveal that the household head’s age is significantly positively correlated with per-mu costs, indicating a pronounced path dependence among older farmers. This supports Schultz’s (1964) theory of traditional agricultural transformation, where “technological lock-in” explains older farmers’ tendency to continue using input-intensive practices (e.g., chemical fertilizers and pesticides) due to depreciation of human capital. Education level is positively associated with per-mu costs, suggesting that more educated farmers may be more likely to adopt technology- or capital-intensive inputs. Risk preference has a negative effect, implying that risk-averse farmers are less likely to engage in high-risk, high-input production behaviors. Land tenure rights are positively correlated with inputs, indicating that secure property rights encourage long-term investments. Agricultural extension services have a positive impact, as they help reduce uncertainty and increase profit expectations through the provision of market information and technical guidance, which in turn encourages higher input utilization. The statistically unstable effect of government subsidies highlights the complexity of policy interventions and their varied impact on production efficiency.

Baseline regression results

| Dependent variable: per-mu input (oLogit) | Dependent variable: per-mu input (oProbit) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Quasi-integrated organization | −0.136 (0.095) | −0.295*** (0.100) | −0.071 (0.053) | −0.168*** (0.057) |

| Household head’s age | 0.020*** (0.005) | 0.010*** (0.003) | ||

| Household head’s gender | −0.114 (0.094) | −0.080 (0.053) | ||

| Education level | 0.514*** (0.053) | 0.266*** (0.029) | ||

| Risk preference | −0.331*** (0.080) | −0.188*** (0.044) | ||

| Operation scale | −0.024 (0.040) | 0.017 (0.022) | ||

| Mechanization level | 0.057 (0.067) | 0.011 (0.038) | ||

| Land property rights | 0.604*** (0.107) | 0.305*** (0.060) | ||

| Government subsidies | 0.448*** (0.135) | −0.254*** (0.077) | ||

| Socialized services | 0.227** (0.109) | 0.183*** (0.061) | ||

| Observations | 1,876 | 1,876 | 1,876 | 1,876 |

| R 2 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.040 | 0.040 |

Standard errors in parentheses *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

4.2 Robustness Tests

4.2.1 Endogeneity Tests

Agricultural quasi-integrated organizations can improve the efficiency of factor allocation while maintaining the autonomy of farming households, thereby contributing to rural revitalization. However, the development of such organizations is inherently shaped by the regional agricultural production environment. Regions with higher productivity and better input-output ratios are more likely to foster a virtuous cycle of organizational development. This bidirectional relationship between efficiency improvement and organizational growth may introduce endogeneity issues in econometric models, potentially undermining the validity of the research findings.

To overcome the endogeneity problem of the model, this study used the instrumental variable method for correction, selecting “whether farmers participate in contract agriculture” as the instrumental variable (Liu et al., 2021). The so-called order agriculture refers to an agricultural production and sales model in which farmers organize and arrange the production of agricultural products based on orders signed between themselves or their rural organizations and buyers of agricultural products (Lai & He, 2003). On the one hand, Xu and Wang (2009) pointed out that the pressure of order fulfillment will encourage farmers to join production organizations to improve production efficiency. Gao (2013), Wang and Xia (2006) also confirmed that agricultural quasi-integrated organizations are highly favored by farmers participating in order agriculture. On the other hand, research has shown that the improvement of farmers’ production efficiency essentially stems from the support conditions such as the technology diffusion network constructed by contractual production organizations (Guo & Liao, 2010; Ye & Cai, 2019) and the reconstruction of supply chain production relationships (Feng et al., 2021; Lu & Ma, 2010; Wang et al., 2014), rather than individual participation behavior of farmers themselves. Although theoretically, signing agricultural orders may provide farmers with pre-arranged markets, technical guidance, and stable supply channels, thereby simplifying production processes, reducing waste, and improving production efficiency. However, the impact of contract farming on production efficiency in practice is uncertain. The risks of contract execution caused by legal regulatory deficiencies, the rigid dilemma of contracts caused by fluctuations in agricultural product and factor prices, and the decision distortion caused by information asymmetry between contracting parties may actually harm farmers’ production efficiency. Therefore, the characteristics of contract farming meet the exogeneity requirements of instrumental variables.

According to the two-stage regression analysis with instrumental variables, as shown in Table 5, contract agriculture as an instrumental variable demonstrated a strong correlation in the first stage (−0.300**). Additionally, the significance of the atanrho_12 parameter (oProbit −0.194*, oLogit −0.483**) confirmed the endogeneity of the model, supporting the use of the conditional mixed process (CMP) method for correction. The second-stage regression results from both models, presented in the table, indicate that the negative impact of agricultural quasi-integrated organizations on farmers’ per-mu production cost input is significant at the 1% level. This indicates that agricultural quasi-integrated organizations can significantly reduce farmers’ per mu production input through contractual management and large-scale production.

CMP estimation results of the impact of agricultural quasi-integrated organizations on farmers’ production efficiency

| Dependent: per-mu input (CMP-oProbit) | Dependent: per-mu input (CMP-oLogit) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variables | First stage | Second stage | First stage | Second stage |

| Quasi-integrated organization | −0.117*** (0.037) | −0.168*** (0.057) | ||

| Contract farming | −0.300*** (0.096) | −0.300*** (0.096) | ||

| atanhrho_12 | −0.194* (0.179) | −0.483** (0.252) | ||

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Regional dummies | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Observations | 1,876 | 1,876 | ||

Standard errors in parentheses *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

It is clear that, although there are minor differences in parameter estimates, both models are statistically significant. The oProbit and oLogit models jointly confirm that agricultural quasi-integrated organizations consistently have a negative effect on per-mu input costs. The CMP estimation further strengthens the robustness of this conclusion, as the coefficient signs and significance levels of the explanatory variables remain highly consistent across different model specifications. By using contract farming as an instrumental variable, this approach not only enhances the reliability of the baseline regression results but also effectively addresses endogeneity concerns. This provides compelling evidence that quasi-integration organizations enhance farmers’ production efficiency.

4.2.2 Alternative Estimation Methods

The development of agricultural quasi-integration organizations is embedded in the local rural socio-economic context, emerging as industrialized entities driven by external forces. The baseline regression results indicate that their impact on farmers’ production efficiency stems not only from institutional effects but also from multifaceted factors such as local demographic characteristics, government policies, and regional economic features. Particularly in regions with robust economic foundations and mature agricultural scale operations, the likelihood of developing effective quasi-integration organizations is higher. Consequently, the formation and establishment of these organizations exhibit inherent non-randomness (Zhang & Xi, 2018). To mitigate potential bias in regression results caused by sample self-selection, this study employs the propensity score matching (PSM) method to rigorously analyze the impact of agricultural quasi-integration organizations on farmers’ production efficiency.

The PSM results presented in Table 6 show that agricultural quasi-integrated organizations have a statistically significant negative effect on farmers’ per-mu input costs across all three matching methods (nearest neighbor, radius, and kernel), confirming the robustness of the baseline regression findings. The estimated effects (−0.130* to −0.168**) are consistent with the coefficient range (−0.117 to −0.168) obtained from the CMP model, forming a methodological triangulation. Together, both approaches substantiate that quasi-integration organizations reduce production costs through economies of scale and centralized management.

PSM test results

| Variable | Matching method | Treatment group | Control group | ATT | Std. err. | t value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| Per-mu input costs | Nearest neighbor | 2.122 | 2.252 | −0.130* | 0.056 | 2.33 |

| Radius | 2.122 | 2.184 | −0.062** | 0.026 | 2.36 | |

| Kernel | 2.11 | 2.290 | −0.168** | 0.045 | 3.72 |

Standard errors in parentheses *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

4.3 Heterogeneity Analysis

The implementation of agricultural quasi-integrated organizations shows considerable regional variation in production foundations, natural endowments, and socio-cultural traditions, which may result in differential impacts on farmers’ production efficiency. To address this, this study constructs a heterogeneity analysis framework based on three dimensions: crop type (economic crops and non-economic crops), geographical location (eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions), and human capital (whether or not receiving professional training). The statistical results are shown in Table 7.

Heterogeneity test results

| Heterogeneity regression results | Crop-type | Regions | Technical training | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variables | Dependent variable: Per-mu input (oLogit) | Dependent variable: per-mu input (oProbit) | Dependent variable: Per-mu input (oLogit) | Dependent variable: Per-mu input (oProbit) | Dependent variable: Per-mu input (oLogit) | Dependent variable: Per-mu input (oProbit) | ||||||||||

| Non-economic crops | Economic crops | Non-economic crops | Economic crops | Eastern region | Central region | Western region | Northeast region | Eastern region | Central region | Western region | Northeast region | No tech training | Tech training | No tech training | Tech training | |

| Quasi-integrated organization | −0.203** (0.114) | −0.656*** (0.221) | −0.118* (0.065) | −0.382*** (0.127) | −0.560** (0.198) | −0.523** (0.213) | −0.367 (0.261) | −0.026 (0.178) | −0.301*** (0.110) | −0.028** (0.118) | −0.207 (0.148) | −0.041 (0.103) | −0.698*** (0.155) | −0.091 (0.136) | −0.390*** (0.086) | −0.057 (0.078) |

| Household head’s age | 0.017*** (0.006) | 0.016 (0.013) | 0.009*** (0.003) | 0.007 (0.007) | 0.009 (0.012) | 0.008 (0.019) | −0.029 (0.025) | −0.122*** (0.044) | 0.005 (0.007) | 0.004 (0.010) | −0.017 (0.014) | −0.077*** (0.025) | 0.015* (0.008) | 0.019*** (0.007) | 0.007 (0.005) | 0.010** (0.004) |

| Household head’s gender | −0.147 (0.104) | −0.084 (0.222) | −0.096 (0.059) | −0.085 (0.127) | −0.085 (0.176) | −0.111 (0.188) | −0.287 (0.273) | 0.006 (0.170) | −0.066 (0.099) | −0.070 (0.105) | −0.179 (0.157) | 0.041 (0.097) | −0.175 (0.140) | −0.044 (0.130) | −0.094 (0.078) | −0.051 (0.074) |

| Education level | 0.560*** (0.060) | −0.076 (0.126) | 0.293*** (0.033) | −0.067 (0.071) | 0.413*** (0.099) | 0.660*** (0.112) | 0.286* (0.154) | 0.432*** (0.100) | 0.215*** (0.055) | 0.358*** (0.061) | 0.153* (0.088) | 0.223*** (0.057) | 0.292*** (0.083) | 0.535*** (0.073) | 0.147*** (0.046) | 0.276*** (0.041) |

| Risk preference | −0.369*** (0.092) | 0.087 (0.168) | −0.222*** (0.051) | 0.051 (0.095) | −0.191 (0.146) | 0.066 (0.164) | −0.134 (0.224) | −0.769*** (0.151) | −0.100 (0.080) | 0.051 (0.091) | −0.089 (0.124) | −0.454*** (0.083) | 0.248** (0.123) | −0.703*** (0.111) | 0.139** (0.068) | −0.414*** (0.061) |

| Operation scale | 0.020 (0.044) | −0.104 (0.100) | 0.003 (0.025) | −0.057 (0.055) | −0.096 (0.071) | 0.242*** (0.093) | −0.117 (0.093) | −0.106 (0.079) | 0.056 (0.039) | 0.150*** (0.051) | −0.075 (0.053) | −0.056 (0.045) | −0.212*** (0.072) | −0.006 (0.050) | −0.106*** (0.039) | −0.011 (0.028) |

| Mechanization level | 0.186** 0.078 | −0.051 (0.153) | 0.090** (0.045) | −0.076 (0.088) | −0.082 (0.122) | 0.277** (0.135) | −0.047 (0.181) | 0.257* (0.137) | −0.072 (0.070) | 0.138* (0.076) | −0.009 (0.104) | 0.127 (0.079) | −0.012 0.097 | 0.062 (0.096) | −0.026 (0.054) | 0.018 (0.056) |

| Land property rights | 0.678*** (0.120) | 0.133 (0.259) | 0.336*** (0.066) | 0.078 (0.147) | 0.550*** (0.214) | 0.175 (0.218) | 0.787** (0.323) | 0.474** (0.188) | 0.300*** (0.115) | 0.107 (0.122) | 0.427** (0.181) | 0.226** (0.108) | 0.039 (0.157) | 0.848*** (0.157) | 0.025 (0.087) | 0.418*** (0.087) |

| Government subsidies | −0.395** (0.156) | −0.468 (0.289) | −0.207** (0.089) | −0.242 (0.161) | −0.683** (0.270) | −0.568** (0.236) | −0.725* (0.438) | 0.032 (0.259) | −0.412*** (0.150) | −0.320** (0.133) | −0.359 (0.244) | 0.068 (0.150) | −0.558*** (0.169) | −0.260 (0.275) | −0.318*** (0.094) | −0.161 (0.154) |

| Socialized services | 0.131 (0.125) | 0.601** (0.239) | 0.147** (0.070) | 0.351*** (0.137) | 0.643*** (0.204) | 0.432* (0.253) | 0.443 (0.285) | 0.010 (0.194) | 0.400*** (0.115) | 0.251* (0.140) | 0.283* (0.163) | 0.038 (0.111) | 0.589** (0.288) | 0.193 (0.129) | 0.371** (0.164) | 0.149** (0.074) |

| Observations | 1,551 | 325 | 1,551 | 325 | 548 | 504 | 269 | 555 | 548 | 504 | 269 | 555 | 891 | 985 | 891 | 985 |

| R 2 | 0.055 | 0.027 | 0.049 | 0.028 | 0.044 | 0.068 | 0.035 | 0.075 | 0.044 | 0.067 | 0.035 | 0.069 | 0.042 | 0.077 | 0.041 | 0.070 |

Standard errors in parentheses *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

4.3.1 Crop-Type Heterogeneity

The choice of production organization is intrinsically linked to cultivation practices, which vary systematically between economic and non-economic crops (Gedara et al., 2012; Zhao & Zhao, 2020). Building on this literature, we examine how quasi-integration organizations differentially affect farmers’ production efficiency across these two crop categories. The empirical results indicate that quasi-integrated agricultural organizations have a significantly positive impact on the production efficiency of farmers across different crop types (Table 7), though with structural variations: the efficiency improvement is notably greater for cash crop growers than for non-cash crop growers. This heterogeneity primarily stems from three dimensions.

Crop attributes: At the crop attribute level, the high market value and significant market risk associated with economic crops make farmers more inclined to experiment with socialized services. For example, the coffee and spice planting industries in Nepal are in great need of large-scale and specialized support, such as wild plant community management, pollinator adaptation technology, and financial services to reduce losses and resolve market risks (Timberlake et al., 2024).

Production characteristics: Non-cash crops require long-term investments in irrigation infrastructure and soil improvement. Their extended growth cycles and low asset specificity make them more reliant on large-scale mechanized production and stable property rights. In contrast, cash crop cultivation depends more on advanced technology and precision management compared to the traditional experiential knowledge dominating non-cash crops, allowing quasi-integrated organizations to deliver more pronounced efficiency gains in standardized production and input intensification.

Market structure: Governments often prioritize food security-related crops (e.g., via subsidies for farmland conservation and agricultural machinery) to reduce production costs and stabilize cultivation areas. This can diminish the comparative advantage of quasi-integrated models for non-cash crops.

4.3.2 Regional Heterogeneity

China exhibits significant disparities in economic development levels and industrial foundations across regions. To precisely examine how these variations influence the sample, this study categorizes the sample into four regions – eastern, central, western, and northeastern China – following the geographic classification of the National Bureau of Statistics. Grouped regression analyses are conducted for farmers in each region to investigate the impact of quasi-integrated organizations on production efficiency under regional heterogeneity. According to the regression results in Table 7, there are significant regional differences in the impact of agricultural quasi-integrated organizations on the per mu cost input of farmers in different regions. Specifically, farmers in the eastern and central regions have significantly benefited from the improvement of production efficiency, while the impact in the western and northeastern regions is relatively limited. This phenomenon can be attributed to regional resource endowment and socio-economic conditions. First, in terms of government subsidies, the Agricultural Development Bank of China, as an important policy bank in China, issued various loans totaling 416.6 billion yuan in 2022, with a loan balance of 602.3 billion yuan, ranking first in the national agricultural development bank system.[3] The Agricultural Development Bank of China Henan Branch has cumulatively invested 27.7 billion yuan in grain, cotton, and oil loans, with a loan balance of 120.2 billion yuan, ranking second in the national system.[4] Compared to these two regions, the policy support for agricultural financial loans in the western and northeastern regions is slightly insufficient, resulting in delayed improvement of agricultural infrastructure and a lack of funding for agricultural enterprise development, which limits the organized development of agriculture in both regions. Second, in terms of geography and climate conditions, the Northeast region is significantly constrained by seasonal production due to the severe cold climate, while the Western region is affected by insufficient light and high temperatures and droughts, resulting in a higher incidence of wheat pests and diseases than the national average. This, to some extent, suppresses the output income expectations and production input enthusiasm of farmers in both regions. Finally, in terms of social services, central provinces such as Shandong and Henan rely on 270 national level agricultural industrialization key leading enterprises (151 enterprises in Shandong Province, ranking first in the country; 119 enterprises in Henan Province, ranking second in the country), such as Shouguang Vegetable Industry Group and a dense agricultural research network, to form a full industry chain collaborative system of “research institutions cold chain logistics market terminals,” significantly improving industrial efficiency. However, due to structural weaknesses such as insufficient technological adaptability and broken industrial chains in the western and northeastern regions, the number of deep processing enterprises is relatively small, and a large number of primary agricultural products have to be circulated across regions in the form of raw materials, seriously restricting the realization of economies of scale.

4.3.3 Heterogeneity in Technical Training

The impact of quasi-integrated organizations on production efficiency also varies based on whether farmers have received technical training. Farmers with technical training generally show a greater willingness to adopt new technologies and a stronger inclination toward production improvement. These traits enable them to better utilize the resources and services offered by quasi-integrated organizations, thereby enhancing production efficiency (Wang et al., 2025a). To further examine this heterogeneous effect, this study explores the specific influence of quasi-integrated organizations on production efficiency under varying conditions of technical training. The results presented in Table 9 indicate that farmers lacking technical training experienced a significant reduction in per-acre input costs upon joining quasi-integrated organizations. This effect was considerably weaker among farmers who had received technical training. This heterogeneity likely arises from the substitution effect of organized farming models on traditional factors of production. Farmers without technical training tend to demonstrate a greater willingness to adopt new technologies, anticipating that organizational models will compensate for their technical skills gap. Quasi-integrated organizations effectively lower farmers’ production input costs in non-technical areas through services such as centralized purchasing and standardized production practices. Conversely, trained farmers, already possessing technical expertise, are more likely to maintain their existing factor input structure. This disparity suggests that technically disadvantaged groups exhibit a greater demand for improvements in production efficiency within organized farming systems.

5 Discussion

5.1 Model Construction

Building on the findings from the baseline regression, agricultural quasi-integrated organizations have a significant positive impact on the production efficiency of Chinese farmers. To further explore the underlying mechanisms, this section expands on the previous analysis by focusing on labor time and labor force size, empirically examining how these organizations influence farmer productivity. Drawing on the methodologies of Wen and Ye (2014), Kumbhakar and Lovell (2000), and O’Donnell (2018), we develop mechanism verification models to test the pathways through which quasi-integrated organizations affect productivity.

Among them, “i” represents different farmers, and “t” represents the year of agricultural production; “x i ” represents the ith control variable, including farmer size, market conditions, farmer characteristics, etc. “Time” is used to measure the labor time of farmers, that is, the proportion of their household agricultural labor time to the total labor time; “Labor” is used to evaluate the level of labor input by farmers in agricultural production, using the main labor structure of agricultural operations as a proxy variable for this indicator. The binary variable “treated” reflects the status of farmers’ participation in agricultural quasi-integrated organizations (participation = 1, non-participation or other forms = 0). “β 1,” “β i ,” “γ 1,” and “γ i ” are coefficients to be estimated, representing the impact of participating agricultural quasi-integrated organizations and other control variables on farmers’ production efficiency in the two equations, respectively. “ε it ” and “e it ” are intercept terms, while “k” and “u” represent random perturbations.

5.2 Empirical Results

5.2.1 The Mediating Role of Labor Time

As shown in the regression analysis results of Table 8, the labor time of farmers exhibits a significant mediating effect on the relationship between agricultural quasi-integrated organizations and production efficiency. Model (1) presents the benchmark regression results on the improvement of farmers’ production efficiency by quasi-integrated organizations. Model (2) demonstrates that these organizations significantly increase farmers’ labor time input. Model (3) further shows that, even after controlling for labor time variables, quasi-integrated agricultural organizations continue to effectively reduce farmers’ per-mu input costs.

Mechanism test of labor time

| Explanatory variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per-mu input | Labor time | Per-mu input | |

| Quasi-integrated organization | −0.295*** (0.100) | 0.745*** (0.095) | −0.248** (0.101) |

| Labor time | 0.113*** (0.039) | ||

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control |

| Region fixed effects | Control | Control | Control |

| Observations | 1,876 | 1,876 | 1,876 |

| R 2 | 0.043 | 0.022 | 0.045 |

Standard errors in parentheses *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

This suggests that quasi-integrated agricultural organizations, through contract-based organizational management, guide farmers to substitute time investment for capital investment, thereby increasing production efficiency while reducing per-acre costs. For example, these organizations can standardize production processes, increasing labor inputs such as manual weeding and organic fertilization to partially replace the consumption of materials like herbicides and chemical fertilizers. They can also optimize production sequences, staggering planting times to reduce farmers’ idle time. Furthermore, through intensive production, they can more efficiently allocate labor time and resources, increasing output per unit of time. Thus, quasi-integrated agricultural organizations, by “increasing management density,” can create an efficiency improvement path of “labor substituting for capital,” ultimately achieving a “refined” transformation of factor allocation.

5.2.2 Mechanism of Labor Force Level Impact

The regression analysis results in Table 9 suggest that quasi-integrated agricultural organizations enhance production efficiency by improving labor force composition. Model (1) presents the baseline regression results, demonstrating the positive impact of these organizations on farmers’ production efficiency. Model (2) shows that, through technical support, training programs, and specialized services, quasi-integrated organizations facilitate optimized labor allocation, effectively “freeing up” labor. Model (3) further confirms a statistically significant negative correlation between improvements in labor force composition and increased production efficiency.

Mechanism test of labor force level

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variable | Per-mu input | Labor force level | Per-mu input |

| Quasi-integrated organization | −0.295*** (0.100) | −0.241** (0.099) | −0.280*** (0.100) |

| Labor time | −0.133** (0.059) | ||

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control |

| Region fixed effects | Control | Control | Control |

| Observations | 1,876 | 1,876 | 1,876 |

| R 2 | 0.043 | 0.018 | 0.044 |

Standard errors in parentheses *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

These findings suggest that, as farmers join quasi-integrated organizations, they are more likely to adopt more efficient agricultural machinery or intensive production methods under expert guidance, thereby reducing reliance on traditional manual labor. Additionally, quasi-integrated organizations enhance management practices through professional agricultural service teams, increasing output per unit area. Furthermore, task specialization and resource sharing within the organization’s collaborative network enable farmers to complete production tasks more efficiently, further boosting overall production efficiency. In sum, quasi-integrated agricultural organizations not only reshape rural labor allocation but also promote the modernization and intensification of agricultural production.

5.3 Testing the Mechanisms

This study employs the Sobel test to assess the validity of the proposed mediating variables. The Sobel test effectively identifies the mediating roles of labor time and labor force level in the relationship between quasi-integrated organizations and farmers’ production efficiency. The results are as follows: When labor time serves as the mediating variable, the total effect is −0.164 (direct effect = −0.248, indirect effect = 0.084), with Z = 2.427 and p = 0.015. When the labor force level acts as the mediating variable, the total effect is −0.248 (direct effect = −0.280, indirect effect = 0.032), with Z = 1.923 and p = 0.054. These findings indicate that the mediating effect of labor time is statistically significant at the 5% confidence level, explaining approximately 51.2% of the total effect. While the mediating effect of labor force level is significant at the 10% level, its explanatory power is comparatively weaker, accounting for only 12.9% of the total effect. These divergent mechanism test results suggest that, within the current context of agricultural production in China, quasi-integrated organizations may be more inclined to implement refined management practices that increase labor time to reduce per-mu input costs. However, constrained by the prevailing trend of rural out-migration, the mediating effect of labor force level is less pronounced, leaving quasi-integrated agricultural organizations to primarily enhance agricultural production efficiency through optimized labor resource allocation.

6 Conclusions, Policy Implications, and Future Works

6.1 Conclusions

This article has explored the factors influencing and mechanisms through which quasi-integrated agricultural organizations affect farmers’ production efficiency. The findings demonstrate that these organizations play a crucial role in facilitating the organic integration of smallholder farmers into modern agriculture, systematically enhancing their sustainable development capabilities through organizational advantages such as technology diffusion and resource integration. This provides strong theoretical support for developing countries aiming to improve their modern agricultural management systems.

On the one hand, this study reveals the differentiated impact of quasi-integrated agricultural organizations on farmers’ production efficiency. Specifically, regarding crop selection, the efficiency gains for farmers growing cash crops are significantly greater than those for farmers growing non-cash crops. Geographically, farmers in the eastern and central regions experience a substantial increase in production efficiency, while the impact on farmers in the western and northeastern regions is less pronounced. Furthermore, with regard to skill training, farmers who have not received technical training show a significant reduction in per-mu input costs after joining quasi-integrated organizations.

On the other hand, this study also elucidates the mechanisms through which quasi-integrated agricultural organizations enhance farmers’ production efficiency. Through scientific and meticulous management, these organizations achieve a “labor-capital” substitution effect via “intensive farming,” thereby reducing per-mu material input costs. Furthermore, by providing technical support, skills training, and promoting intensive production, quasi-integrated agricultural organizations optimize the allocation of rural labor, leading to improved farmer productivity.

6.2 Policy Implications

Building on the research findings, this study aims not only to enhance China’s agricultural competitiveness and contribute to the goal of becoming an “agricultural powerhouse,” but also to provide “Chinese wisdom” and “Chinese solutions” for countries in the global South to explore agricultural transformation models tailored to their national contexts.

First, for different crop types, priority should be given to promoting the quasi-integrated organizational model in economic crop production areas, to fully leverage the synergistic promotion effect of “high value-added crops and organized management.” Specifically, it is recommended that the government provide key support for projects that can significantly reduce the per mu cost of small farmers (such as unified procurement of agricultural materials, promotion of water-saving and fertilizer saving technologies, and sharing of agricultural machinery) or improve per mu output (such as promotion of high-quality seeds and application of precision agriculture technologies), and provide tax incentives for agricultural quasi-integrated organizations that can significantly increase farmers’ income for 3–5 years, so as to concentrate financial resources on areas with the greatest potential for efficiency improvement.

Secondly, implementing differentiated policies for regions at different stages of development can improve agricultural production efficiency while achieving income equity for farmers. For example, in regions with strong foundations, the government should focus on strengthening market regulations, optimizing land transfer systems, and improving socialized service networks. In less developed areas, efforts should be made to cultivate market entities, improve agricultural infrastructure, promote rural inclusive finance, and improve the production capacity of small farmers.

Finally, to achieve sustainable improvements in agricultural production efficiency, a multi-party linkage mechanism involving “scientific research institutions, industrial organizations, and small farmers” should be established. By collaborating with agricultural research institutions, equipping agricultural organizations with smart production technologies, offering modern agricultural training for farmers, accelerating human capital development, and transforming labor-intensive advantages into improved management efficiency, this approach can foster long-term progress.

6.3 Future Works

This article exhibits two primary limitations. Firstly, the data employed is sourced from questionnaire surveys administered to farmers. Given the absence of accounting practices among small-scale farmers, recall bias may introduce measurement errors in crucial variables, such as production costs and working hours. Secondly, the research sample is centered around five major agricultural provinces in China. While encompassing the primary types of agricultural regions, it excludes special agricultural ecological zones like the northwest plateau and the southeast coastal areas. The applicability of the findings to regions with complex terrains or urban agriculture remains to be validated.

Although this article has the aforementioned research limitations, previous studies have mostly been limited to individual agricultural organizations at the micro level, with a relatively narrow research perspective, making it difficult to comprehensively and systematically reveal the contribution of agricultural quasi-integrated organizations in the entire agricultural economic system. The theoretical models and statistical methods used in the analysis process of this article provide new ideas and perspectives for the study of the contribution of agricultural quasi-integrated organizations. Meanwhile, although the research sample did not cover all special agricultural ecological areas, the research results focusing on the five major agricultural provinces in China still reflect to some extent the overall development trend and common problems of Chinese agriculture. This has important reference and inspiration significance for most provinces, cities, and other developing countries in China to formulate agricultural policies, optimize resource allocation, and improve production efficiency.

In light of these research limitations, our future work will incorporate digital technologies, such as remote sensing for yield estimation and blockchain for traceability, to create an objective monitoring system for production efficiency, addressing the limitations of traditional survey data. Additionally, by adopting a cross-national comparative approach, we aim to explore the adaptive variations of quasi-integrated organizations across different land systems. Ultimately, our ultimate goal is to provide more comprehensive theoretical support for developing countries in constructing a modern agricultural organizational system that harmonizes efficiency and equity.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Conceptualization, D.S.; methodology, J.M.; data curation, H.W. and H.Z.; supervision, J.M.; investigation, H.Z.; writing – original draft, J.M. and H.W.; writing – review and editing, D.S. and H.Z.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

References

Adamie, B. A., Balezentis, T., & Asmild, M. (2019). Environmental production factors and efficiency of smallholder agricultural households: Using non-parametric conditional frontier methods. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 70(2), 471–487. doi: 10.1111/1477-9552.12308.Suche in Google Scholar

Aldieri, L., Brahmi, M., Chen, X. H., & Vinci, C. P. (2021). Knowledge spillovers and technical efficiency for cleaner production: An economic analysis from agriculture innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 320, 128830. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128830.Suche in Google Scholar

Bacon, C. (2005). Confronting the coffee crisis: Can fair trade, organic, and specialty coffees reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in northern Nicaragua?. World Development, 33(3), 497–511. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.10.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Deng, H., Zhao, X., & Li, H. (2020). How does optimized allocation of land resources affect economic efficiency? – Empirical evidence from Zhejiang Province’s “performance evaluation based on output per Mu” reform. China Land Science, 34(7), 32–42.Suche in Google Scholar

Dong, Y. (2023). A study on the effective connection paths of small farmers to the E-commerce Market under the digital economy - Based on an analysis of field research cases in Zhengzhou, Kaifeng, Xinyang and other Regions of Henan Province. Price Theory and Practice, 7, 103–106 + 210.Suche in Google Scholar

Du, B., & Wang, O. (2023). Female workers as “coordinators”: The new identity of female workers in the context of county-level urbanization - taking self-employed decoration workers in Z County, North China as an example. Women’s Studies Forum, 6, 61–74.Suche in Google Scholar

Feng, Y., Gao, L., Chen S., & Zhang Y. (2021). The impact of purchase price mechanism on the operation of order agriculture supply chains under different organizational models. Systems Engineering, 39(6), 81–89.Suche in Google Scholar

Fu, C. (2023). The contemporary significance and practical paths of new gentry participating in grassroots consultative democracy to promote common prosperity in Rural Areas. Observation and Thinking, 2, 102–109.Suche in Google Scholar

Gao, H. (2008). Risks and prevention countermeasures faced by Western characteristic agriculture. Social Scientists, 5, 110–112 + 121.Suche in Google Scholar

Gao, J. (2013). An analysis of agricultural quasi-integrated management organizations based on incomplete contract theory. Exploration of Economic Problems, 1, 123–127 + 174.Suche in Google Scholar

Gao, M., Wei, J., & Song, H. (2021). Strategic conception and policy optimization for innovative development of New Rural collective economy. Reform, 9, 121–133.10.4324/9781003185857-6Suche in Google Scholar

Gedara, K. M., Wilson, C., Pascoe, S., & Robinson, T. (2012). Factors affecting technical efficiency of rice farmers in village reservoir irrigation systems of Sri Lanka. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 63(3), 627–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-9552.2012.00343.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Guo, X., & Liao Z. (2010). The formation mechanism and institutional characteristics of company-led cooperatives – Taking Jinli Pig industry cooperative in Qionglai City, Sichuan Province as an example. Chinese Rural Economy, 5, 48–55 + 84.Suche in Google Scholar

Huang, Z., & Liang, Q. (2007). Collective action of small farmers in participating in the big market: An analysis of the case of Ruoheng Watermelon Cooperative in Zhejiang Province. Agricultural Economic Issues, 9, 66–71.Suche in Google Scholar

Ji, Y., & Zhong, F. (2011). Research on the decision-making of agricultural operators on the holding of agricultural machinery. Journal of Agrotechnical Economics, 5, 20–24.Suche in Google Scholar

Jian, S. (2025). Multidimensional poverty in rural china: Human capital vs social capital. Economics-The Open Access Open-Assessment E-Journal, 19(1), 20250140. doi: 10.1515/econ-2025-0140.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiang, C. (2022). Developing digital economy to lead and drive agricultural transformation and rural industrial integration. Macroeconomics, 8, 41–49.Suche in Google Scholar