Abstract

The concept of ecological unequal exchange (EUE) is the methodological basis for proving that the Global North is ecologically exploiting the Global South. Technological progress in the North leads to ever greater exploitation of nature in the South. Numerous mostly empirical studies now exist on this subject. It is striking that the theoretical basis of the EUE approach is often merely a reference to the analogy of the unequal exchange of labor values according to Emmanuel. According to Emmanuel, there is international exploitation of labor if the labor values of production are not exchanged 1:1 between countries or groups of countries. The same applies in the EUE to unequal ecological exchange. However, the focus here is not on the value of labor, but on the consumption of resources and nature (sinks, landfills, etc.). Proponents of this approach see the “ecological balance of payments” (Roepke) as an indicator of the existence and extent of ecological exploitation and unfair trade. This article shows that no reliable indicator of exploitation can be derived from the virtual or actual resource flows between the South and the North that underlie commodity flows. For this purpose, a generalized Ricardo model of foreign trade (the so-called Dornbusch-Fischer-Samuelson model) is employed, and it is first shown that there is no systematic relationship between physical resource flows and the welfare distribution of trade. The concept of a balanced net physical flow of resources between the North and the South is not only unsuitable for diagnosing whether exploitation is occurring but also leads to potentially misguided policies in the North–South relations, e.g., it increases the likelihood of international resource conflicts. This result is confirmed by another corollary, which shows that transfers from the North to the South do not necessarily lead to an improvement in the net material position of the South. Although the transfer is welfare enhancing, it is not reflected in the physical flows. We also find that the claim that inequality of ecological exchange increases with technological progress in the North depends on the direction of technological progress.

1 Introduction

Since the 1980s, images of large-scale deforestation in favor of environmentally harmful monocultures such as oil palms and soybeans have dominated our understanding of the causes and dynamics of environmental degradation in the countries of the Global South. This is often associated with the theory of unequal ecological exchange, which leads to the call to safeguard an equitable exchange of the direct and indirect consumption of nature (measured in virtual ecological footprints) in the North-South trade.

But does an unequal biophysical exchange of goods and services prove that the developed North is ecologically exploiting the developing South? Is the growing prosperity and technological progress in the North leading to an ever-increasing exploitation of nature in the South? In this paper, we find that there is no systematic relationship between physical resource flows and the distribution of trade gains and international welfare. Furthermore, we show that the concept of a balanced net physical flow of resources between North and South is not only inappropriate to diagnose whether exploitation is occurring but also leads to potentially misguided policies in North-South relations that, for example, could increase the likelihood of international resource conflicts. The structure of this article is as follows. In Section 2, we provide a basic overview of the theories of unequal exchange and ecological exploitation in the literature. In Section 3, we rigorously prove in a generalized Ricardo model of foreign trade that there is no systematic relationship between physical resource flows and the distribution of trade gains. We also refute the claim that inequality of ecological exchange generally increases with technological progress in the North. And we show that transfers from the North to the South do not necessarily lead to an improvement in the net material position of the South. Although transfers are widely viewed as a means of reducing global inequality (Atkinson, 1983), they are not reflected in the physical flows. We also find that the claim that inequality of ecological exchange increases with technological progress in the North depends on the direction of technological progress. Section 3.3 shows how the mismeasurement of EUE leads to misguided resource policies, including increasing the possibility of international resource conflicts.

2 Theories of Ecologically Unequal Exchange in Comparative Perspective

Historically, the theory of ecological unequal exchange (EUE) began with Stephen Bunker’s seminal work[1] “Underdeveloping the Amazon: Extraction, Unequal Exchange, and the Failure of the Modern State.” In his theoretically groundbreaking work, Bunker examines the dynamics of underdevelopment in the Brazilian Amazon as a result of environmentally destructive exploitation of natural resources fueled by international trade. At the time, the Global North consisted of industrialized countries, while the Global South consisted of developing countries with varying levels of income, from low-income to high-income countries. The world’s developed economies were sitting in the North (North America and Western Europe) while the developing nations broadly comprised Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia without Japan, the Republic of Corea and Israel, and Oceania without Australia and New Zealand, as in UNCTAD (1985). The People’s Republic of China, the Republic of Vietnam, and socialist countries of Eastern Europe were given special status of state planned, nonmarket economies somewhat aside from the North-South division.

Brazil, the country of his interest, was considered a high-income (but highly indebted) developing country as were the (major surplus) developing countries in the Asia and the Arab world such as Malaysia, Singapore, Saudi-Arabia and the U.A.E. India was considered a low-income developing country in 1985. The terms “Global North” and “Global South” were never used by Bunker in strictly geographical terms (i.e., geographical North or geographical South), but based on their defining characteristics with regard to development dynamics in the relationship between humans and nature. The countries of the Global North were defined to appropriate the natural capital, i.e., energy, raw materials, and natural sink capacities, that the countries of the Global South need for their own development. He speaks of “extraction modes” in demarcation and complement to the Marxist-defined “modes of production” (i.e., slave-owning society, feudalism and capitalism). His aim is to better understand and classify the historical processes of extreme peripherization and impoverishment of regions in the Brazilian Amazon through the extraction of raw materials and the deforestation of rainforests for a pasture farming geared towards short-term profits. In his words[2]: “If the necessary demand for capital and labor increases with increasing depletion of natural capital, the initial profits from extraction decrease rapidly and lead to the complete depletion of the capital, economic collapse and extreme dependence of the peripheral economies on the industrial heartlands of the Global North.” His detailed description of the mechanics of extreme peripherization and impoverishment of regions in the Brazilian Amazon are still outstanding as study of the “development of underdevelopment” (Frank, Singer-Prebisch thesis) paradigm of the world system theories of the 1970s and 1980s (following Wallerstein (1974)).

Ciccantell, a contemporate of Bunker, further developed the understanding of EUE with a strong emphasis on the role of natural capital. Ciccantell’s “raw materialism” focuses more strongly than Bunker on the dynamics of competition between industrialized nations for supremacy (hegemonies). By using the example of the coal industry, he shows how the supremacy in the global appropriation of coal, initially dominated by England alone since the eighteenth century, has been taken over since the 1950s, first by the United States and other Western European countries. In Ciccantell’s words[3]: “In all these countries, the international supremacy in coal (in conjunction with a steel and steel processing industry) has resulted in a broad and networked industrial development, while in the rest of the world it has led to a stronger peripheralization of the raw material producing countries.” His empirical evidence provided is only descriptive for coal (production, consumption per capita, and imports of hard coal in the twentieth century), but can be considered the door opener to the material analyses of supply chains that determine the current image of the EUE. Bunker and Ciccantell (2005) did not analyze the content of elements of natural capital in the exchange relations in their writings.

It was only Hornborg (2012) who started to analyze the “development of underdevelopment” empirically as an asymmetry in flows of energy and biophysical resources between the world’s core and periphery based on his theory of the “industrial metabolism.” According to this concept, the core centers of the world only function systemically with the appropriation of resources and the appropriation of peripheral sink capacities of the peripheries through an the ability of core industrialized nations to engage in trade or other forms of exchange with peripheral nations that are structurally “ecologically unequal.” This concept gained much attraction since with various biophysical metrics being applied to disclose the on-going EUE (Corsi et al., 2024).

The challenge of this growing literature comes with the finding of examples of EUE between trading partners that belong neither to the core nor to the periphery, for example Cambodia’s material exchange relationship with Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam (Frame, 2019). These countries occupy a special semi-peripheral status and are subject to a series of complex, contradictory dynamics that accelerate ecological degradation both within their countries and beyond their national borders. “Semi-peripheries” are already referred to by Wallerstein (1974) as “middle class countries of the capitalist world system” that are engaged in intense upward competition in a hierarchically structured capitalist world economy. In this view, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam are perceived as countries being forced to industrialize rapidly, leading to ecological depletion of their “hinterland,” but also of their own nature. They are still engaged in peripheral activities in relation to the core industrialized nations, while at the same time they are increasingly accessing land and resources in Cambodia for the extraction of primary raw materials, leading to massive environmental degradation there. This finding stands in contrast to the simple core-periphery mechanics of the original EUE theory. Frame’s finding therefore calls for greater theoretical clarity and increased empiricism with regard to the role and definition of semi-peripheral countries in the metabolic process of the world system.

A series of empirical findings backed this claim. For example, Sommer et al. (2019) present international data showing how the flow of mining exports from the periphery to the core regions affects deforestation in the periphery. However, by using an OLS regression for a sample of 61 low- and middle-income countries, they find no evidence for the expected positive relationship between mining exports and deforestation. They refine their analysis by examining how countries with a “triple alliance” of multinational capital, local capital and repressive governance (such as in Brazil during the time of its dictatorship) promote EUE in the mining sector by creating what they call a “good business climate” that includes, for example, exemptions from environmental laws or tax exemptions. Their quantitative data show that mining exports from peripheral countries only reduce forest loss in repressive countries, more so than in democratic countries. The theoretical implications for the EUE are: Intranational as well as international dynamics are responsible for environmental degradation. Focusing only on international material exchange relationships (ecological “terms of trade”) falls short and means that important influencing factors are not included in the EUE theory. This precisely represents the moment when theory starts to follow empiricism, rather than the other way around as it ideally should, merely to avoid scrutinizing established indicators, i.e., biophysical measurement. It is also the moment where it leads to politically incorrect conclusions as we argue here.

Wu (2019) adds the historical dimension to the neo-Marxist narrative of the EUE. In contrast to Bunker’s underdevelopment theories (see above), she argues that energy production and use has developed very differently in China than in Europe or the Amazon. The differences result from particular aspects of Chinese geography and ecology (e.g., low soil fertility and forest poverty in the coal regions) as well as China’s reaction to imperialism in the late nineteen century. The so-called resource curse did not befall China despite a great Western interest in its coal reserves in the nineteen century, well documented in the infamous maps by Richthofen (1903). The case of China discussed by Wu thus underscores the importance of history and contingency for understanding EUE relations already emphasized by Frame (2019) (see above).

In a consistent parallel development of international political theory, Ciplet and Roberts (2018) explain that the Global South is not simply “semi-peripheral” but deeply fragmented. They challenge the classic world systems perspective, or rather the dependency perspective, because it divides the world into a small group of rich countries and a large group of poor, peripheral and dependent countries. Ciplet and Roberts (2018) present rich insights into the series of Conferences of the Parties (COP) and how they are being affected by the fragmentation of the previously united representatives of the Global South. As they point out, this makes it more difficult to sustain the EUE discourse in political contexts.

The ambivalent empirical findings regarding the biophysical determination and measurement of the EUE, coupled with the conflicting political and historical evidence, raises significant doubts about the current methodology for measuring the EUE. These doubts cannot be addressed through further continuing differentiation (semiperiphery, multipolarity of the world order, and so forth) or by analyzing specific historical and political contextual factors.

This has led us to fundamentally reassess the concept of EUE by subjecting the translation of Marx’s labor theory of value into a theory of unequal exchange of resources to a more detailed theoretical analysis, taking into account game-theoretical theories of justice.

Marx coined the term exploitation in connection with the labor theory of value, which posits that exploitation occurs in the sphere of production, where workers receive wages lower than the value of their labor, creating the famous “surplus value” that according to Marxist’s theory becomes the “motor force” of profit-driven capitalistic development. Marx’s ideas was later extended to international trade by other Marxist thinkers like Arghiri Emmanuel, who measured unfair commodity exchange between nations based on the theory of labor value. “Unequal exchange” in Emmanuel’s theory implies that on the world market the poor, peripherical countries of the Global South are forced to sell their products with a relatively large quantum of labor embedded to obtain in exchange commodities embodying a much smaller quantum of labor from the rich countries of the world. As a result, “surplus labor” accumulates and drives the further development in the core countries of the Global North.[4] Dependency theory, as advocated by Frank (1967), described this process as a historical “development of underdevelopment” in countries of the Global South, with or without explicitly referencing Emmanuel’s labor theory of international relations.

This structuralist view of the asymmetry between the South and the North was already developed before the Marxist analysis by Prebisch and Singer. The latter introduced the distinction between the South and the North. The structural asymmetry is primarily caused by the different labor markets, in the South with its infinitely elastic labor supply at a subsistence wage, and the North with a labor market with an institutionally controlled labor supply. Depending on the elasticities of import demand in the South and the North, technological progress can lead to a deterioration in the terms of trade in the South and, thus, to an impoverishment of workers in the South (Prebisch-Singer thesis[5]).

The theory of exploitation based on the labor theory of value was only ever developed in the context of the capitalist economic system.[6] Roemer (1982), on the other hand, developed a general theory of exploitation that can be applied to different economic systems and that utilizes the game-theoretical concept of withdrawal from contracts. He develops and generalizes the concept of exploitation decisively further by not defining exploitation in terms of an exchange relationship of, say, embodied labor but in terms of a benchmark of a fair distribution of resources; in the context of Marx’s approach, the distribution of capital.[7] Roemer thus places the problem of exploitation in the more general context of a theory of justice.[8] One consequence of this approach is that questions of justice in international trade can also be analyzed in the context of neoclassical foreign trade models, for example, by examining the welfare effects of the trade from the perspective of the game theoretic core and cooperative bargaining theory (Section 3.4). This approach relies on the given feasibility of a better alternative to make individuals or members of a group better off by withdrawing from any present allocation system to a feasible hypothetical alternative. This can be applied to the class of workers in a country or to a country of the Global South in international negotiations. Roemer’ s theory encompasses both of those Marxists theories of unequal exchange.

The ecological perspective of unequal exchange gained by utilizing detailed regionalized input–output models and extensive data analyses. The theoretical basis of this approach, however, is often only a mere reference to the analogy of unequal exchange of labor values as developed by Emmanuel. Instead of labor values, the quantities of resources exchanged directly or indirectly in international trade are now measured and compared. The ecological perspective of unequal exchange has evolved through detailed regionalized input–output models and extensive data analysis. However, the theoretical basis of this approach is still often a mere reference to the analogy of unequal exchange of labor values developed by Emmanuel, i.e., “instead of labor values, the quantities of resources exchanged directly or indirectly in international trade are now measured and compared.”

But this means that the class reference of economic distribution is lost, as it is no longer possible to infer from the virtual and real resource flows how the functional distribution of income (wages, profits) develops within the countries involved in global trade. Emmanuel’s theory of unequal exchange referred less to unequal exchange between countries than between the working classes of the developed and underdeveloped countries. This no longer applies in the case of the EUE because here, the exchange ratio of resources between countries is analyzed without reference to the domestic income distribution of the countries. In this respect, the EUE’s reference to Emmanuel’s theory of unequal exchange is not at all clear-cut. Rather, the EUE theory is concerned with determining the fair consumption of resources between countries irrespective of class-related income distribution. In our opinion, however, the question of trade justice between countries cannot be answered with reference to the indicator of physical resource flows, but should refer to the justice of resource endowments, as we will show in Section 3.4 using game-theoretical approaches to justice. The exchange ratios emerging on the international market are not relevant here as we show in Section 3.1.

It is also important to note that we do not analyze the exploitation of nature per se (e.g., deforestation or overfishing) but the biophysically measured exploitation by means of unequal exchange in international relations. There are approaches that link the “overexploitation” of natural resources with the volume of international trade, e.g., Chichilnisky (1993) and Brander and Taylor (1997). These are constructed without reference to material flows. They are driven by a lack of property rights (“open access”) in the exploitation of these resources or weak judicial and labor market institutions[9] in a ruinous supplier competition of the countries of the Global South. This additional institutional deficiency is not taken into account in our article as we focus on the simple North–South relationships in the sense of EUE and world systems theories.

There is a close connection between the theories of ecological exploitation and the theories of virtual water trade. Virtual water is the water embodied in products, not in a biophysical sense, but in virtual sense. It refers to the water needed for the production of the products (Hoekstra and Hung, 2005). Virtual water content is nothing else as a life cycle accounting of water similar to energy balance approaches etc. The claim made by virtual water theory is that trade increases a globally uneven water distribution. High water scarcity, as for example in the Middle Eastern Countries, makes it attractive to import virtual water and thus make those countries become even more water dependent. “The mechanisms of international trade in staple foods continue to operate with proven effectiveness to ameliorate the uneven water endowments on the world’s regions,” states Allan (1998), a pioneer in virtual water trade research. At the same time, virtual water trade reduces the potential of water conflict. Virtual water trade prevents water scarcity becoming the cause of water wars, e.g., in the Middle East (Allan (2002) and (2003)). From this point of view, virtual water trade should even be encouraged in drafting water policy plans.

The ensuing discussion of whether the concept of virtual water can be used as a basis for trade policy measures to promote a fair distribution of the unfair distribution of resources (leveling water endowments between countries) requires caution, however. On the one hand, the empirical results are inconclusive. While Debaere (2014) finds a clear correlation between relative water availability and exports of water-intensive products in a multifactor model with water, capital and labor, Kumar and Singh (2005) arrives at negative results, which they attribute to the fact that the factor of land should be taken into account. This is because the achievable water supply depends on the cultivated agricultural area. Furthermore, there is a discussion about the relationship between the virtual water concept, its implication for the leveling effect, and the standard foreign trade theory (Heckscher-Ohlin model). A distinction must be made between countries’ relative and absolute water resource endowment. The desired leveling effect only occurs when the countries differ in their absolute water endowment Ansink (2010) and Reimer (2012). This discussion is of great importance for trade policy (Park and Ridley, 2025) because it is necessary to clarify whether a fair international trade order should be based on relative or absolute resource endowments.

The potential failure of policies based on the principle of a balanced net position becomes evident in the history of virtual water trade theory. As discussed in Chapter 2, during the 1980s, virtual water trade was regarded as a policy for improving global water use efficiency and preventing water conflicts (Allan, 2003). However, with the development of the water footprint as a metric, the focus shifted to ensuring measurable equality in direct and indirect resource use. This led to policy proposals requiring nations to equalize their water footprint through trade, and, if necessary, compensate other countries for excess water use under the concept of “water neutrality” (Hoekstra, 2008). The avoidance of international water conflicts, which was originally the aim of virtual water trade, has been sidelined, despite its clear role in enhancing global welfare from a joint ownership perspective.

3 Ecologically Unequal Exchange in an Extended Ricardian Trade Model

3.1 Equality of Resource Flows Versus Equality of Welfare

The relationship between biophysical flows and trade flows can be well developed within the extended Ricardo trade model[10] developed by Dornbusch et al. (1977).[11] We use this model not in terms of labor but in terms of natural resources as only fixed input. This allows us to focus solely on resources, as the focus of the EUE approach is set by the construction of aggregated metrics of natural resources. While this assumption of fixity would undoubtedly be problematic for a model focusing on the labor market it makes sense for many countries endowed with natural resources, especially those in the Global South with structurally lower exploration capacities.

The production of goods in both the South and the North is based on using only one input, namely, a resource or an aggregate of resources. There is a continuum of goods indexed

International production specialization depends on the prices of goods. Under the (usual) assumption of the basic Ricardian model, there is perfect competition, so the product supply prices follow from the following price equations.

where

From equation (3.2), it follows

where

From equation (3.3), we can find the borderline commodity

which divides the product space into goods

The demand for the commodities are derived from a Cobb-Douglas utility function for both, the South and the North, assuming identical preferences.[14] This task is simple also for the case of a continuous spectrum of goods.[15] The demand functions are as follows:

where

where

Income in the South and North is generated in the factor market. Therefore,

Define

and utilizing

Equation (3.10) shows the factoral terms of trade as function of the relative endowment of resources and as a function of the range of products the South is producing in trade equilibrium, i.e.,

The range of commodities

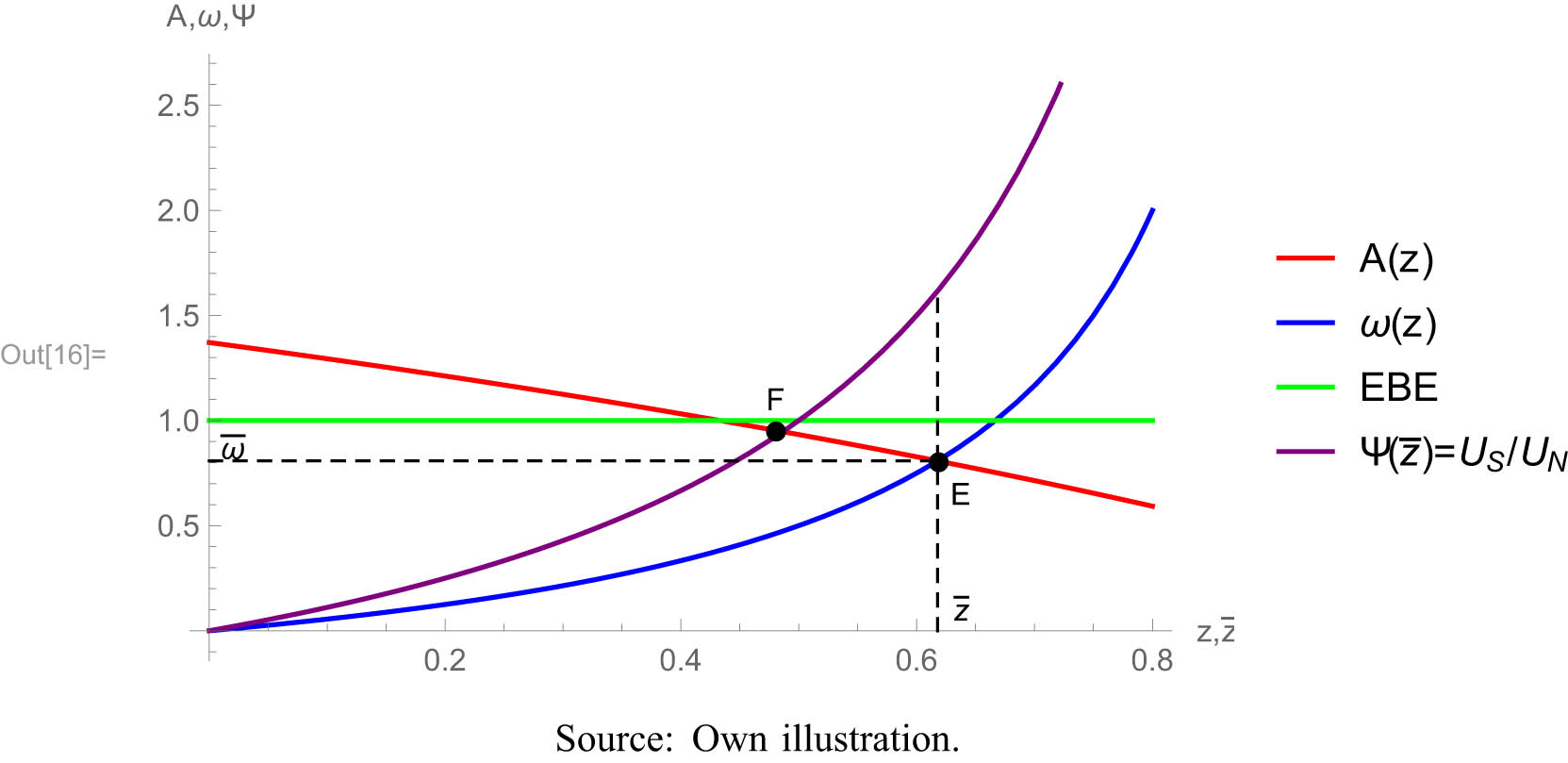

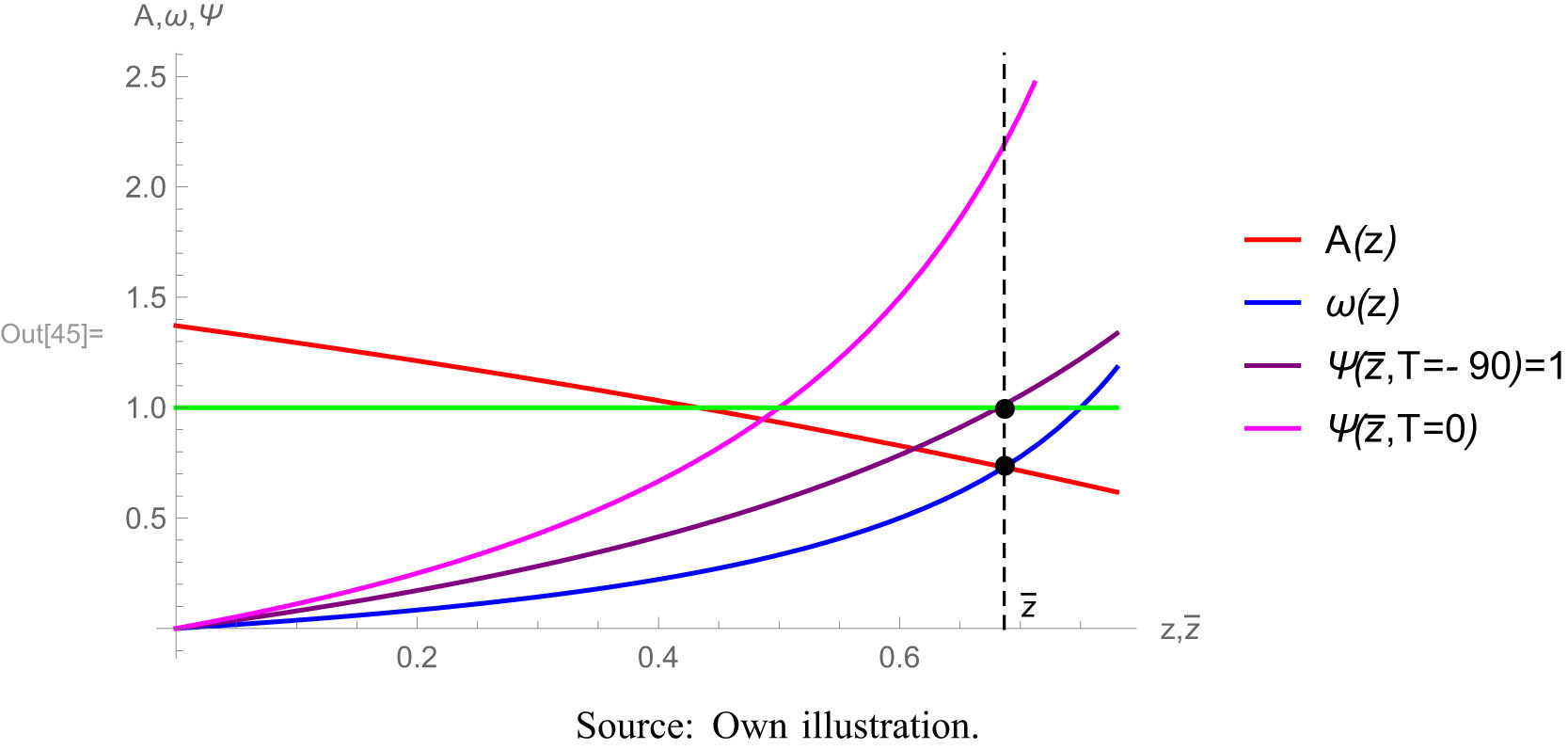

Figure 1 and the following figures are based on numerical parameter values[17] that have not been determined empirically but are chosen to reflect the results of the empirical literature about trade patterns and international production specialization. For example, Debaere (2014) shows that relatively water-rich countries export water-intensive products. The results of the EUE literature also show that resource-rich countries export resource-intensive goods so that they are net exporters of their resources (Dorninger and Hornborg, 2015). In addition, we have chosen the numerical values such that the trade equilibrium leads to ecologically unequal exchange between the South and the North since the factoral terms of trade are less than unity.

Factoral terms of trade and the production range of the South. Source: Own illustration.

Result 1

The net outflow of resources from the South to the North cannot be used as an indicator of the ecological exploitation of the South.

The result follows from the fact that trading in the Ricardo model is voluntary. Exploitation can only exist if trade is forced because the state of autarky would make the South better off. In our numerical example, on which the figure is based, gains of trade are realized for both, the South and the North, even though the factoral terms of trade are to the South’s disadvantage.[18] If

Result 2

The net outflow of resources from the South to the North cannot be taken as an indicator of unfair trade.

The fairness of the welfare distribution is shown in Figure 1 by the

Factoral terms of trade and welfare distribution. Source: Own illustration.

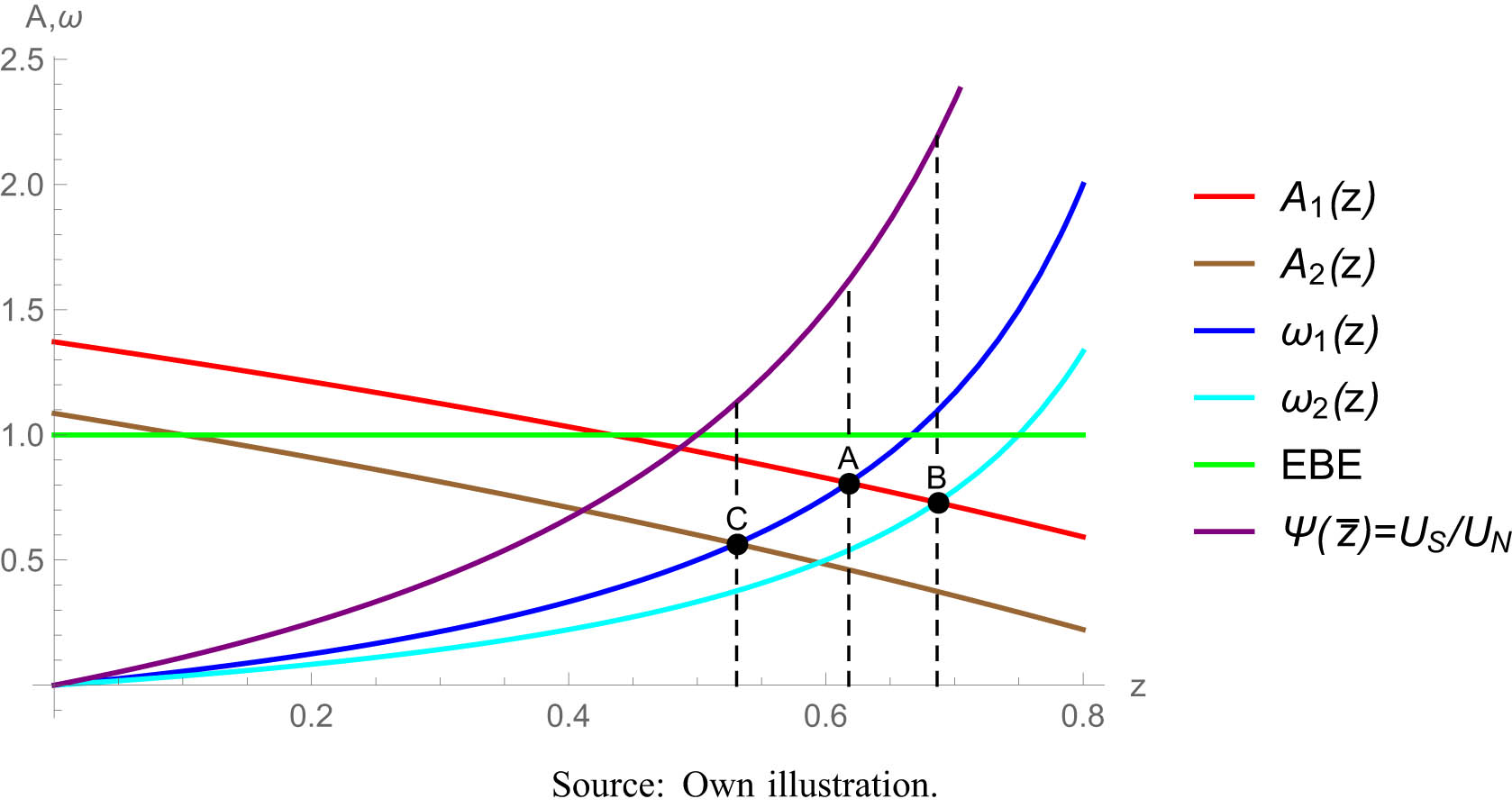

In the first case, the factor input of the South increases such that the trade equilibrium shifts from A to B implying that the factoral terms of trade have fallen to the disadvantage of the South. At the same time, however, the welfare distribution improves in favor of the South since

The two cases show that there is no clear monotonic relationship between biophysical flows and the distribution of trade gains between the two blocks of countries. Whether there is a positive or negative correlation between the welfare distribution and the factoral terms of trade depends on the exogenous determinants that influence the relative resource flows expressed by

3.2 Technological Gaps and Asymmetric Technological Progress

According to the EUE approach, asymmetric technological progress, i.e., the faster technological development of the North, leads to an increasing exploitation of resources in the South because technological progress displaces the production of the South into resource extraction (Althouse et al., 2023). This relationship is illustrated in Figure 2 for the scenario 2 (the shift in equilibrium from A to C). Although the welfare of both hemispheres increases in the course of technical progress in the North, the distribution changes to the disadvantage of the South. As the technological progress of the North increases, the

However, technical progress will relate more to those production processes that are used in both hemispheres, i.e., technical progress will be directed towards the respective domestic production. There is a similarity here with the concept of neutral technical progress in growth theory (Hicks neutrality). This approach has been criticized by Atkinson and Stiglitz (1969), who argue that technical progress depends on factor proportions.[22] Instead, they have developed the concept of “localized technical progress,” which in our context means that technical progress has only an impact on the actual production processes.

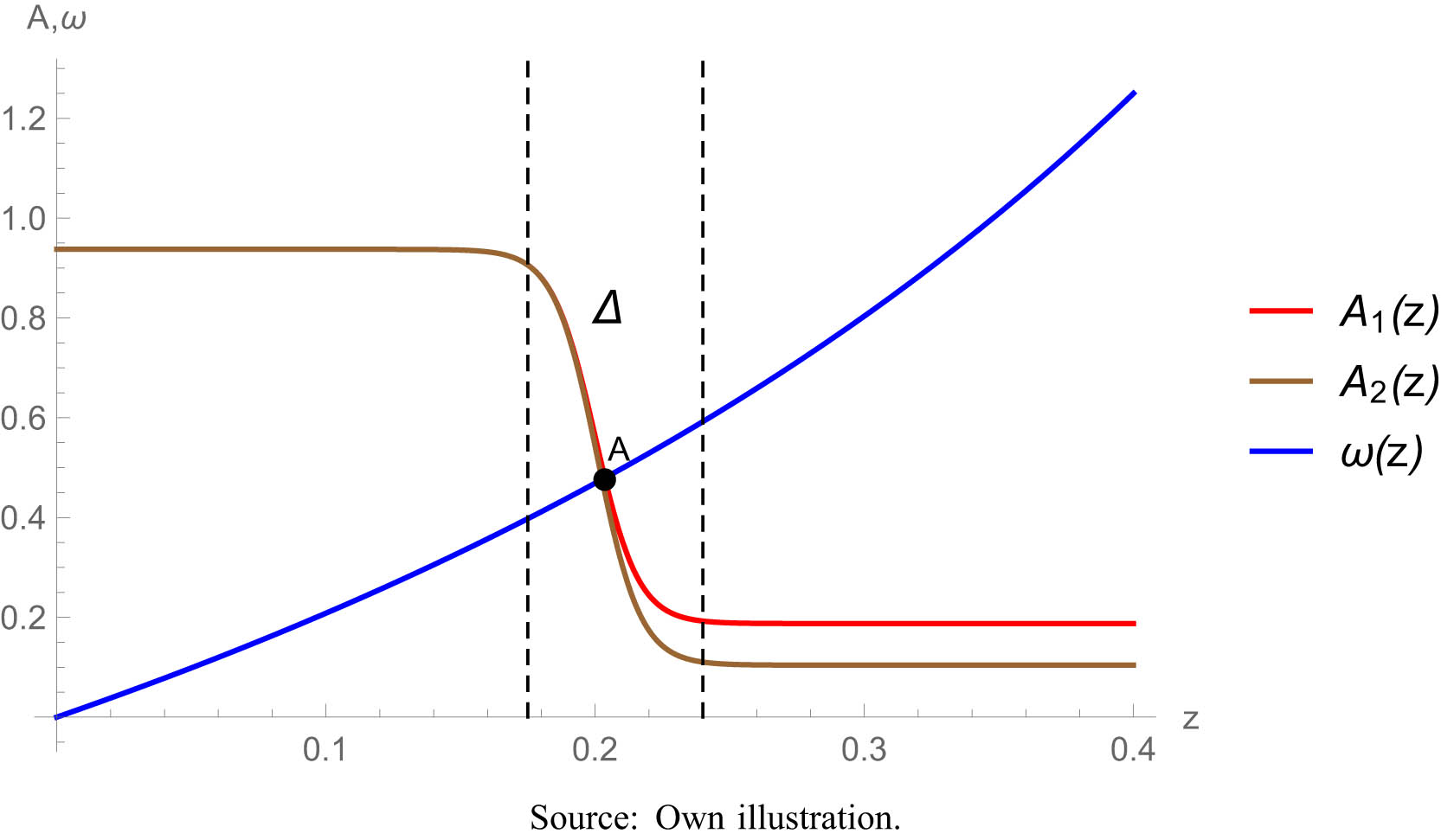

The localized technical concept can also explain why the North’s one-sided, continuous innovation process leads to a technological gap. The

Technological progress in the North. Source: Own illustration.

The curve drops steeply in the

Result 3

Technological progress in the North does not necessarily lead to a deterioration in the factoral terms of trade and the distribution of welfare between the South and the North. In addition, welfare has risen in both hemispheres.

Thus, technological progress in the North is not necessarily at the expense of the South as claimed in the EUE-literature. Although the terms of trade are falling to the disadvantage of the South, the distribution of welfare is not changing. Here, the technological divide even provides protection against a shift in value creation from the South to the North (

3.3 A neo-Ricardian reconstruction of EUE within the DFS model

In contrast to the standard two-factor neoclassical foreign trade models, which include the DFS model, in neo-Marxist theory, the distribution of income between labor and capital is not determined according to the scarcity and productivity of the two factors but is the result of political–economic power relations, which Emmanuel refers to as “extra-economic factors.”[24] The exchange relations of internationally traded goods between the periphery and the center (barter terms of trade) then follow from the predetermined wage-profit-rate ratio. The unequal exchange about the exchange of labor values is, therefore, the result of these power relations, which do not result from the relative factor endowments as derived, e.g., in the H-O-model. The neoclassical interpretation of the Ricardian one-factor model of international trade is also rejected. There, the international exchange relationships are determined by different production techniques and the relative factor endowments between the trading partners. Analytically, the neo-Marxist approach is expressed using the Marxian value and price determination scheme. However, by using the Marxian scheme leads to problems with consistent separation between labor values and market prices. In a later contribution[25] Emmanuel therefore also transferred his theory of unequal exchange into a neo-Ricardian framework.[26]

His basic conclusion is[27]

that the inequality of wages as such, all other things being equal, is alone the cause of the inequality of exchange.

where wage levels are not the result of supply and demand in a free labor market, but are formed in a political-economic process, i.e., are model-exogenous. If we transfer this labor value theory approach to the resource exchange relationship between the South and the North, we can represent this approach by the following modifications of the price equation (3.1) of the DFS model:

where the bars indicate that resource prices are fixed and

Since the rate of return is identical across the trading partners, it plays no role in determining the international distribution of production because the relative costs advantages are not affected by the uniform rate of return. To determine the trade equilibrium, we can, therefore, proceed directly to equation (3.4). If we also consider the demand side, assuming that resource owners and capital owners have the same consumption preferences, we arrive at equation (3.10), which together with equation (3.4) determines both

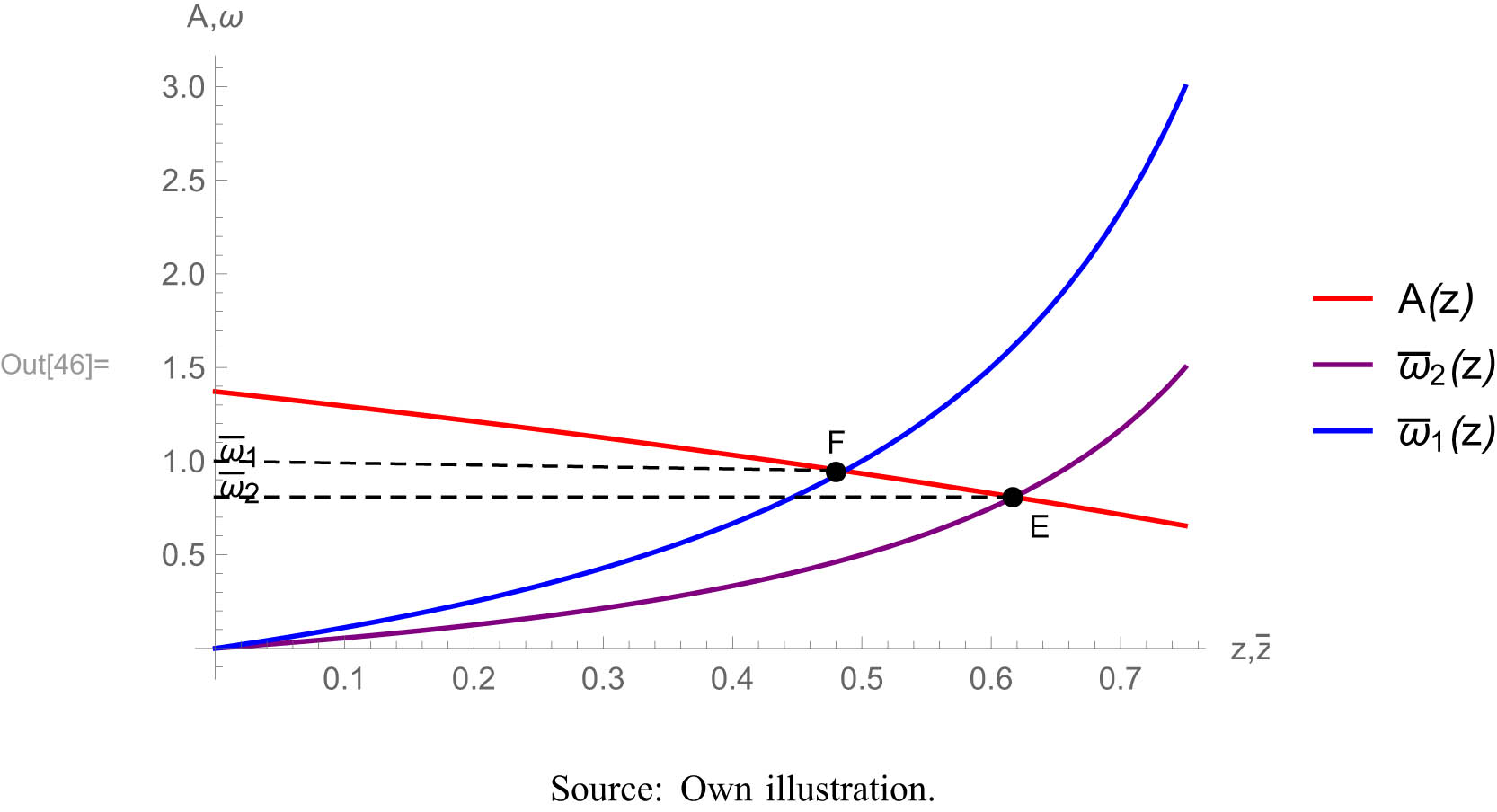

Fixed factoral terms of trade and resource use. Source: Own illustration.

At point F, there is a trade equilibrium with factoral terms of trade of

Result 4

The deterioration of the factoral terms of trade leads to a relatively greater utilization of the South’s resources. Therefore, the increased net outflow of resources from the South is accompanied by increased resource exploitation in the South. EUE to the disadvantage of the South and increased exploitation of South’s nature thus go hand in hand.

From the perspective of labor theory of value, this conclusion is understandable. The factoral terms of trade also reflect the relative income per worker (

Another criticism of the EUE approach is the unspoken implication that a deterioration in the factoral terms of trade results in the overexploitation of nature. The fact that an exogenous deterioration in the terms of trade leads to an increase in the use of resources does not mean that nature’s regenerative capacities have been exceeded. This question can only be answered if the institutional framework of resource use is clarified.[33] The assumption of exogenous resource prices is taken from the neo-Marxist model of labor exploitation. The workers receive their fixed subsistence wage. Lewis adopted this relationship for dual economies with an agricultural subsistence sector and an industrial sector. The fixed labor wage is the result of an oversupply of labor that is offered if the wage exceeds the subsistence income.[34] However, it is not clear whether these characteristics of the labor market in the South can simply be transferred to the resource market in the South. The neoclassical modeling approach with a fixed supply of resources at a flexible resource price approximates reality better because the extraction of natural resources is limited by capacities whose expansion requires investments. Thus, the supply of resources is presumably not completely elastic.

3.4 Fair Trade, Transfers, and EUE

Beyond the neo-Marxian literature, there is also an extensive literature on the relation between inequality and international trade.[35] In this section, we discuss some criteria of international distributive justice and their policy instruments for its implementation within the DFS model. We show that justice-oriented trade policy should not make its instruments dependent on biophysical flows.

In the Ricardian one-factor model, distribution problems can only relate to the endowment of factors and the ownership of technologies. When applying the model to natural factors, migration cannot be used as a means of distribution policy.[36] Thus, natural resources cannot be allocated directly to countries according to equity criteria. Their endowment is subject to geographical randomness, be it resources that are used as inputs or natural capacities for absorbing emissions and waste. However, resources can be redistributed virtually by assigning property rights[37] and the question remains as to the normative basis on which claims can be legitimized.[38] There are two opposing fundamental criteria: self-ownership and joint ownership. Applied to countries, the first principle considers a country to be the rightful owner of a natural resource because the population has legitimately appropriated it. This position implies that the appropriation is not to the detriment of others. The second principle considers the geographical distribution of natural resources across countries’ territories to be (morally) random or arbitrary.[39] This view concludes that all natural resources are owned jointly by all countries (joint ownership) and gives rise to a claim by resource-poor countries to the proceeds of trade based on the utilization of resources of resource-rich countries. The issue of fair trade, therefore, does not relate to the exchange ratio of goods or virtual resource content, as in the theory of ecologically unequal exchange, but to the fair distribution of resource ownership.[40] The principle of joint ownership can also be applied to the ownership of productivity-enhancing technologies of economies.[41] Exclusive ownership claims can be legitimized if production technologies have not come to their owners by chance but due to their efforts. This also applies if technological disadvantages do not result from the systematic prevention of development opportunities. If, on the other hand, technological differences are the result of historical randomness or power constellations, then technologies should also be jointly owned.

Before we analyze the welfare-theoretical implications of the distributive justice criteria within the framework of the DFS model, we examine the effect of distributive policy instruments. These transfers between the South and the North can take place in various ways: Technology transfers, direct investments (capital transfers), the assignment of property rights to natural resources, and transfers of purchasing power. Here, we do not pursue the first two transfers further because they would require a model of higher complexity. We only consider the allocation of property rights that lead to corresponding transfers of scarcity rents, i.e., purchasing power. The effects of transfers have been extensively analyzed in the literature and goes back to Keynes’ classic analysis.[42] In the simple, pure foreign trade models of Ricardian provenance and the multifactor models of Heckscher and Ohlin, transfers do not change the factoral terms of trade if the preferences of the trading countries are identical. This can be shown for the DFS-model (Section A.4) and is illustrated in Figure 5.

Effects of transfers from South to North. Source: Own illustration.

The figure contains the two functions

Result 5

With identical preferences, transfers do not change the factoral terms of trade, but they do change the welfare distribution. This means that a fair distribution policy is not reflected in the material flows between the South and the North.

Thus, constructing a fair trade system should not be based on the physical net position of international trade. Distribution policy should not be linked to physical flows because there is no monotonic relationship between welfare distribution and the net ecological position of trade relations.

It remains to determine the amount of transfers with the help of equity criteria. Here, we follow Roemer’s approach[44] and relate the question of justice to the distribution of natural resources and technological equipment. If the level of endowments is not the result of the deliberate efforts of the acting societies, i.e., if they are morally arbitrary, they should be collectively owned. Therefore, the trade equilibrium derived in Section 3.1 is unjust if

where

It follows from this approach that the transfer amount should be chosen so that the incomes of both countries are equal, i.e.,

For example, if we consider both the principle of joint ownership and that of sovereignty equally, we arrive at a transfer determination that takes into account the autarky starting point of both countries. The South and North remain in autarky if no agreement is reached on a possible transfer. The corresponding Nash bargaining approach is expressed as follows:

where

With different starting positions in autarky, this principle means that welfare in both blocs differs even after a transfer has been implemented.

The combined principle[47] of joint ownership and sovereignty (autarky as starting point and fallback position) legitimizes different starting positions as morally justified. As a rule, the transfer calculated from the equation does not equal zero. This means that pure trade equilibrium without an accompanying transfer is considered unfair from this normative perspective, although the approach is also committed to self-ownership of initial resource endowments. This is because the bargaining approach contains an element of equality. The distribution of trade benefits will not be left to the mechanics of supply and demand alone, but the welfare gains of the North and the South will be distributed equally. The positive welfare effect of trade resulting from specialization in comparative cost advantages is joint ownership. Finally, it should be emphasized once again, whichever principle is considered morally acceptable, cursive joint ownership or the mediated principle of cursive joint ownership, both relate the issue of fair trade to the distribution of natural resources and technologies and not to the exchange ratio of ecological values.

4 Conclusions and Policy Implications

This article has theoretically proven that there is no systematic relationship between physical resource flows and the distribution of trade gains or international welfare. The normative idea of a balanced net physical flow of resources between the North and South is not a suitable metric for assessing fairness in trade or detecting exploitation. In fact, relying on this measure could lead to misguided policies in the (North-South relations). As discussed in Section 3, the normative goal of balanced terms of trade in material terms does not promote, but can even contradict, two recognized strategies of international distributional policies in the (North-South relations): bridging the technological gap and facilitating transfers of purchasing power. Notably, transfers from the North to the South do not necessarily improve the South’s net material position, even though they enhance welfare. This occurs because such transfers are not directly reflected in physical resource flows. Furthermore, the assertion that inequality in ecological exchange increases with technological progress in the North depends on the direction of that progress. This fundamental questioning of international redistribution policies extends to all other forms of development cooperation unrelated to material flows, such as initiatives supporting human rights, good governance, and the rule of law.

The EUE theory’s institutional neglect aligns it closely with the well-known “naturalistic fallacy” (Moore, 1903). The EUE school defines fairness based solely on the equality of the factoral terms of trade. Anything that cannot be measured within this framework is neither categorized as just nor unjust. However, our findings indicate that the disparities in resource endowments shape the international distributional outcomes of trade. Greater theoretical clarity and empirical analysis of “extractive institutions” (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2019) and, in particular, governance structures in developing countries are necessary factors to explain natural resource dependency. In many cases, the structural dependencies and inequities in resource endowments become more apparent when trade is restricted or ceases altogether (Park and Ridley, 2025 p. 282/283). On the other hand, trade policies that incorporate environmental, social, and governance standards in both industrialized and developing countries can not only provide a clearer understanding of the international factors driving environmental degradation but also offer mechanisms for controlling them. We therefore argue for a critical reassessment of the biophysical indicators used by the EUE school. The factoral terms of trade are simply not a reliable measure of equity between countries (Results 1 and 2). To illustrate this, consider the following thought experiment: Imagine a world where the North and the South share strong joint ownership of resources, and where the factoral terms of trade are initially at point F in Figure 1. If, by an act of God, resource endowments were to shift in favor of the South (point E in Figure 1), the South’s welfare would increase significantly in both absolute and relative terms. However, under the EUE framework, this shift would paradoxically be classified as a negative development. Conversely, if resources were redistributed in favor of the North, this could increase the likelihood of ecological exploitation according to EUE measurements. This thought experiment demonstrates the methodological self-referentiality of the EUE framework – or, more bluntly, its tautological nature. The material flow analysis first identifies exploitation when the factoral terms of trade deviate from a 1:1 resource exchange. It then calculates the material net outflow and uses its negative value to confirm the predetermined conclusion of ecological exploitation. Instead of allowing measurement to follow theory, EUE allows theory to be dictated by measurement – leading to politically problematic conclusions, as we contend.

The potential failure of policies based on the principle of a balanced net position becomes evident in the history of virtual water trade theory. As discussed in Chapter 2, during the 1980s, virtual water trade was regarded as a policy for improving global water use efficiency and preventing water conflicts (Allan, 2003). However, with the development of the water footprint as a metric, the focus shifted to ensuring measurable equality in direct and indirect resource use. This led to policy proposals requiring nations to equalize their water footprint through trade, and, if necessary, compensate other countries for excess water use under the concept of “water neutrality” (Hoekstra and Hung, 2005). The avoidance of international water conflicts, which was originally the aim of virtual water trade, has been sidelined despite its clear role in enhancing global welfare from a joint ownership perspective.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the reviewer’s valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. GM: conception of the work; redesign of the DFS model for EUE purposes; formal analysis and interpretation; drafting of the work. RS: conception of the work; formal analysis and interpretation; substantive revision and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

Appendix

A.1 Derivation of the Demand Function

To derive the demand functions, we follow DFS and assume identical utility functions in both, North and South, specified by a Cobb-Douglas function:

where

To derive the demand functions

where

A.2 Factoral Terms of Trade and Biophysical Flows

The amount of resources embodied in the commodities transferred from the North to the South, i.e., the amount of resources (virtually) imported to the South, is

where

Dividing resources imported, i.e., equation (A4), by resources exported, i.e., equation (A3) , yields the factoral terms of trade:

where the last step follows from equation (3.10), i.e.,

A.3 Derivation of the Utility-Ratio Function

The derivation of the two ratios requires the calculation of the indirect utility functions by inserting the optimal consumption according to equation (3.5) into the utility function equation (A1). We first calculate the logarithm

and then carry out the transformation

In the trading equilibrium, the integral must be split into the two intervals

where

Similar, we can find for the North

If we subtract

and, utilizing equation (A1) and equation (3.10), thus

A.4 Effects of the Transfer on the

ω

- and

Ψ

-Function

To derive the effects of a transfer

Since we assumed identical preferences in the South and the North it is immediately clear that

To derive the effect of

where we have inserted

Subtracting equation (A13) from equation (A12) yields

Utilizing the definition of the factoral terms of trade in equilibrium

where

A.5 Derivation of the Equitable Transfer

We transform the maximization program (3.13) by taking the logarithm of the objective function. This leads to the program

where

where

where

The optimal

where

The first-order condition of equation (3.14) is

where

By inserting

References

Acemoglu, D. (2015). Localised and biased technologies: Atkinson and stiglitz’s new view, induced innovations, and directed technological change. The Economic Journal, 125(583), 443–463. 10.1111/ecoj.12227Suche in Google Scholar

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Rents and economic development: the perspective of why nations fail. Public Choice, 181, 13–28. 10.1007/s11127-019-00645-zSuche in Google Scholar

Allan, J. A. (1998). Virtual water: a strategic resource. Ground water, 36(4), 545–547. 10.1111/j.1745-6584.1998.tb02825.xSuche in Google Scholar

Allan, J. A. (2002). Hydro-peace in the middle east: why no water wars? a case study of the Jordan river basin. SAIS Review of International Affairs, 22, 255. 10.1353/sais.2002.0027Suche in Google Scholar

Allan, J. A. (2003). Virtual water-the water, food, and trade nexus. Useful concept or misleading metaphor? Water International, 28(1), 106–113. 10.1080/02508060.2003.9724812Suche in Google Scholar

Althouse, J., Cahen-Fourot, L., Carballa-Smichowski, B., Durand, C., & Knauss, S. (2023). Ecologically unequal exchange and uneven development patterns along global valu e chains. World Dev, 170, 106308. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106308Suche in Google Scholar

Ansink, E. (2010). Refuting two claims about virtual water trade. Ecological Economics, 69(10), 2027–2032. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.06.001Suche in Google Scholar

Atkinson, A. B. (1983). The economics of inequality. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Suche in Google Scholar

Atkinson, A. B., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1969). A new view of technological change. The Economic Journal, 79(315), 573–578. 10.2307/2230384Suche in Google Scholar

Bacha, E. L. (1978). An interpretation of unequal exchange from Prebisch-singer to Emmanuel. Journal of Development Economics, 5(4), 319–330. 10.1016/0304-3878(78)90015-9Suche in Google Scholar

Brander, J. A., & Taylor, M. S. (1997). International trade between consumer and conservationist countries. Resource and energy economics, 19(4), 267–297. 10.1016/S0928-7655(97)00013-4Suche in Google Scholar

Bunker, S. G. (1985). Underdeveloping the Amazon: Extraction, unequal exchange, and the failure of the modern state. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. Suche in Google Scholar

Bunker, S. G., & Ciccantell, P. S. (2005). Globalization and the Race for Resources. Baltimore: JHU Press. 10.56021/9780801882425Suche in Google Scholar

Chichilnisky, G. (1993). North-South trade and the dynamics of renewable resources. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 4(2), 219–248. 10.1016/0954-349X(93)90017-ESuche in Google Scholar

Cimoli, M. (1988). Technological gaps and institutional asymmetries in a North-South model with a continuum of goods. Metroeconomica, 39(3), 245–274. 10.1111/j.1467-999X.1988.tb00878.xSuche in Google Scholar

Ciplet, D., & Roberts, J. T. (2018). Splintering south: Ecologically unequal exchange theory in a fragmented global climate. in Ecologically Unequal Exchange: Environmental Injustice in Comparative and Historical Perspective (pp. 273–305). Cham: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-89740-0_11Suche in Google Scholar

Corsi, G., Guarino, R., Munnnoz-Ulecia, E., Sapio, A., & Franzese, P. P. (2024). Uneven development and core-periphery dynamics: A journey into the perspective of ecologically unequal exchange. Environmental Science & Policy, 157, 103778. 10.1016/j.envsci.2024.103778Suche in Google Scholar

Debaere, P. (2014). The global economics of water: is water a source of comparative advantage? American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(2), 32–48. 10.1257/app.6.2.32Suche in Google Scholar

Dell’Angelo, J., Rulli, M. C., & D’Odorico, P. (2018). The global water grabbing syndrome. Ecological Economics, 143, 276–285. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.06.033Suche in Google Scholar

Dornbusch, R., Fischer, S., & Samuelson, P. A. (1977). Comparative advantage, trade, and payments in a Ricardian model with a continuum of goods. The American Economic Review, 67(5), 823–839. Suche in Google Scholar

Dorninger, C., & Hornborg, A. (2015). Can EEMRIO analyses establish the occurrence of ecologically unequal exchange? Ecological Economics, 119, 414–418. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.08.009Suche in Google Scholar

Emmanuel, A. (1972). Unequal exchange: A study of the imperialism of trade. New York: Monthly Review Press. Suche in Google Scholar

Emmanuel, A. (1975). Unequal exchange revisited. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex. Suche in Google Scholar

Evans, D. (1984). A critical assessment of some neo-Marxian trade theories. The Journal of Development Studies, 20(2), 202–226. 10.1080/00220388408421896Suche in Google Scholar

Felbermayr, G., Jung, B., Kohler, W., & Harms, P. (2017). Ricardo-Gestern und heute. ifo Schnelldienst, 70(09), 3–18. Suche in Google Scholar

Findlay, R. (1982). International distributive justice: a trade theoretic approach. Journal of International Economics, 13(1–2), 1–14. 10.1016/0022-1996(82)90002-2Suche in Google Scholar

Findlay, R. (1991). Terms of trade. In The World of Economics (pp. 665–671), Springer. 10.1007/978-1-349-21315-3_92Suche in Google Scholar

Fischer, C. (2010). Does trade help or hinder the conservation of natural resources? Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 4(1), 103–121. 10.1093/reep/rep023Suche in Google Scholar

Fleurbaey, M. (2014). The facets of exploitation. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 26(4), 653–676. 10.1177/0951629813511552Suche in Google Scholar

Frame, M. (2019). The role of the semi-periphery in ecologically unequal exchange: A case study of land investments in Cambodia. Ecologically unequal exchange: Environmental injustice in comparative and historical perspective (pp. 75–106). Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-89740-0_4Suche in Google Scholar

Frank, A. G. (1967). Capitalism and underdevelopment in Latin America (Vol. 93). New York: NYU Press. Suche in Google Scholar

Gandolfo, G. (2013). International trade theory and policy. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. 10.1007/978-3-642-37314-5_1Suche in Google Scholar

Gollin, D. (2014). The lewis model: A 60-year retrospective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 71–88. 10.1257/jep.28.3.71Suche in Google Scholar

Hickel, J., Dorninger, C., Wieland, H., & Suwandi, I. (2022). Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global south through unequal exchange, 1990–2015. Global Environmental Change, 73, 102467. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102467Suche in Google Scholar

Hoekstra, A. Y., & Hung, P. Q. (2005). Globalisation of water resources: international virtual water flows in relation to crop trade. Global Environmental Change, 15(1), 45–56. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.06.004Suche in Google Scholar

Hoekstra, A. Y. (2008). Water neutral: reducing and of setting water footprints. Delft, The Netherlands: UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education.Suche in Google Scholar

Hornborg, A. (2012). Global ecology and unequal exchange: fetishism in a zero-sum world (vol. 13), London: Routledge. 10.4324/9780203806890Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, R. W. (1975). Presumption and the transfer problem. Journal of International Economics, 5(3), 263–274. 10.1016/0022-1996(75)90013-6Suche in Google Scholar

Kanbur, R. (2015). Globalization and inequality. In Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2, pp. 1845–1881), London: RELX Group (Elsevier Publ.).10.1016/B978-0-444-59429-7.00021-2Suche in Google Scholar

Kumar, M. D., & Singh, O. P. (2005). Virtual water in global food and water policy making: is there a need for rethinking? Water resources management, 19, 759–789. 10.1007/s11269-005-3278-0Suche in Google Scholar

Mainwaring, L. (1980). International trade and the transfer of labour value. The Journal of Development Studies, 10(3), 22–31. 10.1080/00220388008421778Suche in Google Scholar

Moore, G. E. (1903). Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Suche in Google Scholar

Morishima, M. (1974). Marx in the light of modern economic theory. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 42(4), 611–632. 10.2307/1913933Suche in Google Scholar

Ocampo, J. (1986). New developments in trade theory and ldcs. Journal of Development Economics, 22(1), 129–170. 10.1016/0304-3878(86)90054-4Suche in Google Scholar

Ospina-Holguín, J. H. (2017). The Cobb-Douglas function for a continuum model. Cuadernos de Economía, 36(70), 1–18. 10.15446/cuad.econ.v36n70.49052Suche in Google Scholar

Park, D., & Ridley, W. (2025). Thirsty for trade: How globalization shapes virtual water trade. Environmental and Resource Economics, 88(2), 279–338. 10.1007/s10640-024-00928-0Suche in Google Scholar

Reimer, J. J. (2012). On the economics of virtual water trade. Ecological Economics, 75, 135–139. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.01.011Suche in Google Scholar

Richthofen, F. v. (1903). Baronas Richthofen Letters 1870–1872, Shanghai: North China Herald Office. Suche in Google Scholar

Roemer, J. (1983). Unequal exchange, labor migration and international capital flows: A theoretical synthesis, marxism, central planning and the soviet economy: Economic essays in honor of Alexander Erlich (padma desai, ed.), Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. Suche in Google Scholar

Roemer, J. E. (1982). A general theory of exploitation and class. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 10.4159/harvard.9780674435865Suche in Google Scholar

Roemer, J. E. (1996). Theories of distributive justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Suche in Google Scholar

Sandel, M. J. (2007). Justice: A reader. USA: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oso/9780195335118.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Shapiro, J. S. (2023). Institutions, comparative advantage, and the environment. Technical report. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. 10.3386/w31768Suche in Google Scholar

Sommer, J. M., Shandra, J. M., & Coburn, C. (2019). Mining exports flows, repression, and forest loss: A cross-national test of ecologically unequal exchange. Ecologically unequal exchange: Environmental injustice in comparative and historical perspective (pp. 167–193). Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-89740-0_7Suche in Google Scholar

UNCTAD (1985). Trade and development report. Suche in Google Scholar

Wallerstein, I. (1974). 1974 the modern world system (440 p.), New York: Academic. Suche in Google Scholar

Wilson, C. A. (1980). On the general structure of ricardian models with a continuum of goods: applications to growth, tariff theory, and technical change. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 48(7), 1675–1702. 10.2307/1911928Suche in Google Scholar

Wu, S. X. (2019). History matters: contingency in the creation of ecologically unequal exchange. Ecologically unequal exchange: Environmental injustice in comparative and historical perspective (pp. 221–241). Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-89740-0_9Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Research on the Coupled Coordination of the Digital Economy and Environmental Quality

- Optimal Consumption and Portfolio Choices with Housing Dynamics

- Regional Space–time Differences and Dynamic Evolution Law of Real Estate Financial Risk in China

- Financial Inclusion, Financial Depth, and Macroeconomic Fluctuations

- Harnessing the Digital Economy for Sustainable Energy Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of China’s Yangtze River Delta

- Estimating the Size of Fiscal Multipliers in the WAEMU Area

- Impact of Green Credit on the Performance of Commercial Banks: Evidence from 42 Chinese Listed Banks

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics II: Core Themes of the Multilevel Paradigm

- Spillover Nexus among Green Cryptocurrency, Sectoral Renewable Energy Equity Stock and Agricultural Commodity: Implications for Portfolio Diversification

- Cultural Catalysts of FinTech: Baring Long-Term Orientation and Indulgent Cultures in OECD Countries

- Loan Loss Provisions and Bank Value in the United States: A Moderation Analysis of Economic Policy Uncertainty

- Collaboration Dynamics in Legislative Co-Sponsorship Networks: Evidence from Korea

- Does Fintech Improve the Risk-Taking Capacity of Commercial Banks? Empirical Evidence from China

- Multidimensional Poverty in Rural China: Human Capital vs Social Capital

- Property Registration and Economic Growth: Evidence from Colonial Korea

- More Philanthropy, More Consistency? Examining the Impact of Corporate Charitable Donations on ESG Rating Uncertainty

- Can Urban “Gold Signboards” Yield Carbon Reduction Dividends? A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the “National Civilized City” Selection

- How GVC Embeddedness Affects Firms’ Innovation Level: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies

- The Measurement and Decomposition Analysis of Inequality of Opportunity in China’s Educational Outcomes

- The Role of Technology Intensity in Shaping Skilled Labor Demand Through Imports: The Case of Türkiye

- Legacy of the Past: Evaluating the Long-Term Impact of Historical Trade Ports on Contemporary Industrial Agglomeration in China

- Unveiling Ecological Unequal Exchange: The Role of Biophysical Flows as an Indicator of Ecological Exploitation in the North-South Relations

- Exchange Rate Pass-Through to Domestic Prices: Evidence Analysis of a Periphery Country

- Private Debt, Public Debt, and Capital Misallocation

- Impact of External Shocks on Global Major Stock Market Interdependence: Insights from Vine-Copula Modeling

- Informal Finance and Enterprise Digital Transformation

- Wealth Effect of Asset Securitization in Real Estate and Infrastructure Sectors: Evidence from China

- Consumer Perception of Carbon Labels on Cross-Border E-Commerce Products and its Influencing Factors: An Empirical Study in Hangzhou

- How Agricultural Product Trade Affects Agricultural Carbon Emissions: Empirical Evidence Based on China Provincial Panel Data

- The Role of Export Credit Agencies in Trade Around the Global Financial Crisis: Evidence from G20 Countries

- How Foreign Direct Investments Affect Gender Inequality: Evidence From Lower-Middle-Income Countries

- Big Five Personality Traits, Poverty, and Environmental Shocks in Shaping Farmers’ Risk and Time Preferences: Experimental Evidence from Vietnam

- Academic Patents Assigned to University-Technology-Based Companies in China: Commercialisation Selection Strategies and Their Influencing Factors

- Review Article

- Bank Syndication – A Premise for Increasing Bank Performance or Diversifying Risks?

- Special Issue: The Economics of Green Innovation: Financing And Response To Climate Change

- A Bibliometric Analysis of Digital Financial Inclusion: Current Trends and Future Directions

- Targeted Poverty Alleviation and Enterprise Innovation: The Mediating Effect of Talent and Financing Constraints

- Does Corporate ESG Performance Enhance Sustained Green Innovation? Empirical Evidence from China

- Can Agriculture-Related Enterprises’ Green Technological Innovation Ride the “Digital Inclusive Finance” Wave?

- Special Issue: EMI 2025

- Digital Transformation of the Accounting Profession at the Intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Ethics

- The Role of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Shaping Business Innovation: Insights from End Users’ Perspectives and Practices

- The Mediating Role of Climate Change Mitigation Behaviors in the Effect of Environmental Values on Green Purchasing Behavior within the Framework of Sustainable Development

- The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship Between Paradoxical Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

- Special Issue: The Path to Sustainable And Acceptable Transportation

- Factors Influencing Environmentally Friendly Air Travel: A Systematic, Mixed-Method Review

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation - 2nd Edition

- Redefining Workplace Integration: Socio-Economic Synergies in Adaptive Career Ecosystems and Stress Resilience – Institutional Innovation for Empowering Newcomers Through Social Capital and Human-Centric Automation

- Knowledge Management in the Era of Platform Economies: Bibliometric Insights and Prospects Across Technological Paradigms

- The Impact of Quasi-Integrated Agricultural Organizations on Farmers’ Production Efficiency: Evidence from China

- The Impact and Mechanism of the Creation of China’s Ecological Civilization Building Demonstration Zones on Labor Employment

- From Social Media Influence to Economic Performance: The Capital Conversion Mechanism of Rural Internet Celebrities in China

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Research on the Coupled Coordination of the Digital Economy and Environmental Quality

- Optimal Consumption and Portfolio Choices with Housing Dynamics

- Regional Space–time Differences and Dynamic Evolution Law of Real Estate Financial Risk in China

- Financial Inclusion, Financial Depth, and Macroeconomic Fluctuations

- Harnessing the Digital Economy for Sustainable Energy Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of China’s Yangtze River Delta

- Estimating the Size of Fiscal Multipliers in the WAEMU Area

- Impact of Green Credit on the Performance of Commercial Banks: Evidence from 42 Chinese Listed Banks

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics II: Core Themes of the Multilevel Paradigm

- Spillover Nexus among Green Cryptocurrency, Sectoral Renewable Energy Equity Stock and Agricultural Commodity: Implications for Portfolio Diversification

- Cultural Catalysts of FinTech: Baring Long-Term Orientation and Indulgent Cultures in OECD Countries

- Loan Loss Provisions and Bank Value in the United States: A Moderation Analysis of Economic Policy Uncertainty

- Collaboration Dynamics in Legislative Co-Sponsorship Networks: Evidence from Korea

- Does Fintech Improve the Risk-Taking Capacity of Commercial Banks? Empirical Evidence from China

- Multidimensional Poverty in Rural China: Human Capital vs Social Capital

- Property Registration and Economic Growth: Evidence from Colonial Korea

- More Philanthropy, More Consistency? Examining the Impact of Corporate Charitable Donations on ESG Rating Uncertainty

- Can Urban “Gold Signboards” Yield Carbon Reduction Dividends? A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the “National Civilized City” Selection

- How GVC Embeddedness Affects Firms’ Innovation Level: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies

- The Measurement and Decomposition Analysis of Inequality of Opportunity in China’s Educational Outcomes

- The Role of Technology Intensity in Shaping Skilled Labor Demand Through Imports: The Case of Türkiye

- Legacy of the Past: Evaluating the Long-Term Impact of Historical Trade Ports on Contemporary Industrial Agglomeration in China

- Unveiling Ecological Unequal Exchange: The Role of Biophysical Flows as an Indicator of Ecological Exploitation in the North-South Relations

- Exchange Rate Pass-Through to Domestic Prices: Evidence Analysis of a Periphery Country

- Private Debt, Public Debt, and Capital Misallocation

- Impact of External Shocks on Global Major Stock Market Interdependence: Insights from Vine-Copula Modeling

- Informal Finance and Enterprise Digital Transformation

- Wealth Effect of Asset Securitization in Real Estate and Infrastructure Sectors: Evidence from China

- Consumer Perception of Carbon Labels on Cross-Border E-Commerce Products and its Influencing Factors: An Empirical Study in Hangzhou

- How Agricultural Product Trade Affects Agricultural Carbon Emissions: Empirical Evidence Based on China Provincial Panel Data

- The Role of Export Credit Agencies in Trade Around the Global Financial Crisis: Evidence from G20 Countries

- How Foreign Direct Investments Affect Gender Inequality: Evidence From Lower-Middle-Income Countries

- Big Five Personality Traits, Poverty, and Environmental Shocks in Shaping Farmers’ Risk and Time Preferences: Experimental Evidence from Vietnam

- Academic Patents Assigned to University-Technology-Based Companies in China: Commercialisation Selection Strategies and Their Influencing Factors

- Review Article

- Bank Syndication – A Premise for Increasing Bank Performance or Diversifying Risks?

- Special Issue: The Economics of Green Innovation: Financing And Response To Climate Change

- A Bibliometric Analysis of Digital Financial Inclusion: Current Trends and Future Directions

- Targeted Poverty Alleviation and Enterprise Innovation: The Mediating Effect of Talent and Financing Constraints

- Does Corporate ESG Performance Enhance Sustained Green Innovation? Empirical Evidence from China

- Can Agriculture-Related Enterprises’ Green Technological Innovation Ride the “Digital Inclusive Finance” Wave?

- Special Issue: EMI 2025

- Digital Transformation of the Accounting Profession at the Intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Ethics

- The Role of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Shaping Business Innovation: Insights from End Users’ Perspectives and Practices

- The Mediating Role of Climate Change Mitigation Behaviors in the Effect of Environmental Values on Green Purchasing Behavior within the Framework of Sustainable Development

- The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship Between Paradoxical Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

- Special Issue: The Path to Sustainable And Acceptable Transportation

- Factors Influencing Environmentally Friendly Air Travel: A Systematic, Mixed-Method Review

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation - 2nd Edition

- Redefining Workplace Integration: Socio-Economic Synergies in Adaptive Career Ecosystems and Stress Resilience – Institutional Innovation for Empowering Newcomers Through Social Capital and Human-Centric Automation

- Knowledge Management in the Era of Platform Economies: Bibliometric Insights and Prospects Across Technological Paradigms

- The Impact of Quasi-Integrated Agricultural Organizations on Farmers’ Production Efficiency: Evidence from China

- The Impact and Mechanism of the Creation of China’s Ecological Civilization Building Demonstration Zones on Labor Employment

- From Social Media Influence to Economic Performance: The Capital Conversion Mechanism of Rural Internet Celebrities in China