Abstract

Whether government expenditure in elderly-care institutions can improve the efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions is not only related to the realisation of “Care for the Elderly,” but also one of the concerns of policymakers and implementers. In order to explore the impact of government expenditure on the efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions, DEA-Tobit two-stage model is used with a sample of 50 elderly-care institutions in Wuhan. Firstly, the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is evaluated using the DEA method. Secondly, the Tobit regression model is employed to examine the effect of government expenditure on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. The research finds that government direct investment has no significant effect on the efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions, while fiscal subsidies can effectively improve it. Under the condition of controlling other variables, for every 10,000 yuan increase in fiscal subsidies, the value of comprehensive technical efficiency and pure technical efficiency of elderly-care institutions increase by 0.244 and 0.181, respectively. Therefore, to improve the efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions, fiscal subsidies should be chosen more often to purchase care in elderly-care institutions, and through it to guide the social forces to enter the field of nursing services.

1 Introduction

At the end of 2023, the national population aged 60 years or older will reach 297 million, accounting for 21.1% of the total; the population aged 65 years or older will reach 217 million, accounting for 15.4% of the total.[1] This means that China has entered a deeply aging society, which puts higher demands on the supply side of institutional elderly care services. At the end of 2023, there will be 41,000 elderly care institutions nationwide, with 8.201 million beds for elderly care services and only 27.6 beds for every 1,000 elderly people.[2] Institutionalised elderly services are characterised as quasi-public goods. The government is the public service arranger or provider and can arrange who produces public services, what services are produced, and how oversight of the services is achieved (Savas, 2002).[3] Since 2006, China has put forward the idea of actively supporting the development of the elderly services industry in a variety of ways, such as public–private construction, privately running under state ownership, government subsidies, and the purchase of services,[4] as well as guiding and supporting social forces in the development of various kinds of elderly service facilities.[5] Since then, the construction of elderly care facilities across China has been diversified into contracting, joint ventures, leasing, etc. In 2013, the State Council called for the launch of a pilot restructuring of publicly run elderly care facilities and government-invested elderly care beds have gradually been transformed into privately-run facilities.[6] The way and content of government purchasing in institutionalised elderly care services are further clarified in this document (Kang & Lv, 2016).[7] The Opinions on Promoting the Development of Elderly Services, issued by the General Office of the State Council in April 2019, proposes to give full play to the role of public elderly care institutions and public–private elderly care institutions in underwriting and guaranteeing elderly care, reduce the burden of elderly care taxes and fees, bring elderly care into the guiding catalog of services purchased by the government, and enhance the level of precision in government investment.[8] The Outline of the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for the National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China and the Vision for 2035, issued in March 2021, calls for the improvement of the elderly care system, the improvement of the management mechanism for public-private construction of private institutions, and the enhancement of policy support for private care institutions for the elderly.[9] In practice, governments at all levels have made substantial investments in government purchases of institutional care services. So, has government expenditure for the elderly (hereinafter referred to as government expenditure) achieved the policy objectives? Has government expenditure improved the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service? To what extent has it done so? What are the areas for improvement? These questions not only are related to the realisation that “old people are supported fully,” but are also important concerns for policymakers and implementers, and require urgent research by scholars.

In order to find out whether government expenditure in elderly-care institutions can improve the efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions and explore the impact of government expenditure on the efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions, DEA-Tobit two-stage model is used with a sample of 50 elderly-care institutions in Wuhan. Institutional elderly care services have a certain degree of public goods characteristics, which makes it difficult to apply the profit maximisation criterion for evaluation. Inputs and outputs of institutional aged-care services are diversified and their measurement involved are differentiated, which makes it difficult to make horizontal comparisons and assign weights. However, the DEA method can overcome these difficulties to measure the relative effectiveness of decision-making units with multiple inputs and outputs that are homogeneous and comparable, and it is well adapted to evaluate the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. Based on the efficiency values of the integrated technical efficiency, the pure technical efficiency and the scale efficiency obtained by the DEA method, the tobit regression model is applied to investigate the impact of government expenditure on the efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions which has been neglected in previous research. To fill this gap, we have taken government expenditure as an independent variable. Moreover, in order to observe whether different modes of spending have different effects on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service and the degree of their effects, we divide government expenditure into government direct investment and government subsidy according to its mode.

2 Literature Review

Currently, the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service has received little attention and lacks systematic and in-depth research. Despite the large amount of literature on institutionalised elderly care service in China, most of the research is on the demand for institutionalised elderly care services (He et al., 2008; Jiang & Si, 2006) and how to increase the supply of institutionalised elderly care services (Gui, 2001; Ioviţă, 2012; Liu & Xiao, 2012; Liu et al., 2008; Mu, 2012; Wang & Zhang, 2024; Zhang & Zhang, 2010). There are fewer researches on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, and there is an even greater lack of research to develop measurements or evaluation of the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service.

In the few literature on the evaluation of the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) is mostly used. Tran et al. (2019) used Meta-analysis to collate the literature on the evaluation of the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, and found that most of them had used the DEA model. Institutional elderly care services have a certain degree of public goods characteristics, which makes it difficult to apply the profit maximisation criterion for evaluation. Inputs and outputs of institutional aged-care services are diversified and difficult to express through explicit mathematical functions. The units of measurement of the various indicators involved are differentiated, making it difficult to make horizontal comparisons and assign weights. The evaluation of service efficiency is subjective and the required data collection is difficult. These factors evaluate the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service very difficult (Ren, 2016). However, the DEA technique is a strong and flexible method with the ability to handle multiple inputs and outputs simultaneously (Negahban et al., 2023; Rasinojehdehi & Najafi, 2024). Thus, it can overcome complications for the lack of a common measurement scale (Lee & Saen, 2012). It is widely used for assessing the efficiency of DMUs such as organizations, institutions, or companies (Roy et al., 2024), which makes it a useful technique in many fields, ranging from economics to healthcare, and even industrial engineering (Ekram Nosratian & Taghavi Fard, 2023; Roy et al.,2024). In the institutional elderly-care service field, Dulal (2017) used the Bootstrap-DEA method to analyse the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service of 338 institutions in California, USA and found that the staffing structure was not conducive to the improvement of technical efficiency. Zhou and Chai (2015) used the DEA method to research the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in Ningbo and found that the overall level of scale efficiency was high. Ma et al. (2017) and Gan et al. (2023) used the same method to research the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in China and found that the efficiency of services in the Eastern region was significantly higher than that in the Western region, but they did not further explore the factors influencing the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service on this basis.

A few scholars have explored the factors influencing the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service based on evaluating their efficiency, but have not focused on the variable of government expenditure. Sexton et al. (1989) used the DEA methodology to derive the values of efficiency of 52 elderly-care institutions in the state of Maine in the United States and researched the factors influencing the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service using a multiple regression model. Fizel and Nunnikhoven (1992), Ni Luasa et al. (2018) and Nyman, Bricker (1989) successively found that the nature of the elderly care organisation has a significant effect on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. Rosko et al. (1995) further found that the differences in the efficiency of elderly care institutions of different natures were due to the influence of managerial and environmental factors. Kooreman (1994) first chose the more fitting Tobit model as a tool for exploring the efficiency influencing factors. In China, Wu (2011) analysed the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service and its influencing factors in Jinan using the DEA method and Tobit model and found that the efficiency influencing factors were mainly the type of recreational implementation and the number of managers. Ren (2016) used the same method to research the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in Xiamen and found that factors such as the total value of fixed assets of the institutions and whether or not they were affiliated with hospitals negatively affected the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. Kang and Li (2023) and Yang and Chang (2019) explored the effects of factors such as social capital, professional and technical skilled personnel, and the number of beds on the efficiency of elderly care services in the case of Beijing. However, these researches do not consider the impact of government expenditure on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service when exploring the factors influencing the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service.

These researches provide some support for the evaluation of the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service and the exploration of its influencing factors, but due to the demographic, economic and geographic differences in each region, the indicators chosen are not the same, and the conclusions obtained are different. Moreover, these research studies omit the important variable of government expenditure when analysing the influencing factors of efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, which is inconsistent with the current situation of government fiscal support for the development of institutional elderly-care service at all levels in China. Given this, this article takes Wuhan as an example to evaluate the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in Wuhan using the DEA method, adopting the correlation analysis method to determine the independent variables and select the control variables. On this basis, the Tobit model is used to focus on whether government expenditure has an impact on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service and the degree of its impact, which provides a foundation for optimising the allocation of resources in elderly-care institutions and improving the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service.

The structure of the article is as follows. First, theoretical hypotheses are proposed based on public goods theory. Secondly, the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is evaluated using the DEA method based on the sample data of 50 elderly-care institutions in Wuhan. Then, the Tobit regression model is used to examine the effect of government expenditure on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service and the degree of its influence. Finally, corresponding conclusions and recommendations are put forward.

The innovations of this article are as follows: (1) DEA-Tobit analysis based on the micro-data obtained from the investigation of institutional elderly services in Wuhan. (2) It focuses on whether the variable of government expenditure, which has been neglected in previous research, can improve the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. (3) According to the mode of government expenditure, it is divided into government direct investment and government subsidy to observe whether different modes of spending have different effects on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service and the degree of their effects.

3 Theoretical Hypothesis

Musgrave (1939) and Samuelson (1954) argue that, given the non-exclusive and non-competitive nature of public goods, private provision entails an efficiency or welfare loss and therefore should be supplied by the government. The non-exclusive and non-competitive nature of institutional elderly-care service is incomplete, and it is a quasi-public good with characteristics of both private and public goods. Because institutional elderly-care service have benefit spill-overs, one part of the benefits it provides is enjoyed by its owner, is divisible, and its benefits can be priced, having the characteristics of private goods. However, the other part of the benefits is enjoyed by other people, which is indivisible and has the characteristics of public goods. For example, if the elderly residents enjoy institutional elderly-care service to improve the quality of life of the elderly, this part of the benefits is divisible, but the improvement of the quality can benefit the whole society, which reflects the characteristics of public goods.

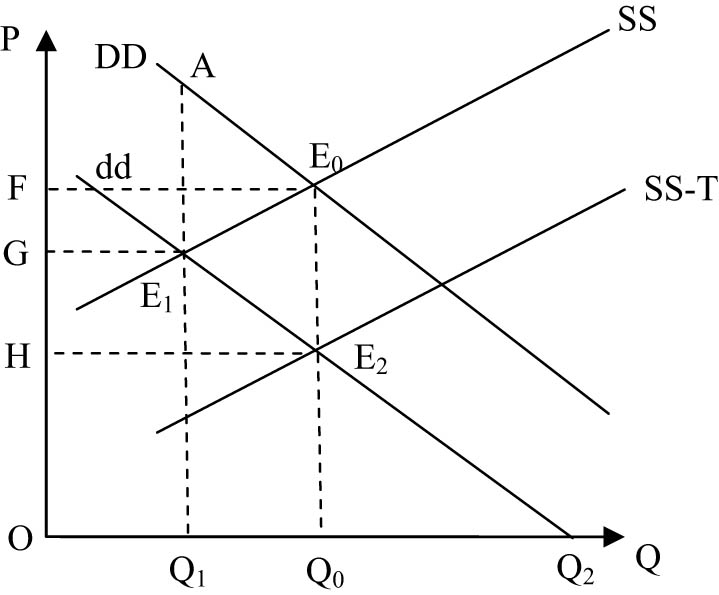

For the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service supply, as in Figure 1, dd is the marginal utility curve (demand curve) of the purchaser of institutional elderly-care service, DD is the marginal utility curve of society, and the vertical distance between them is expressed as the marginal external utility of institutional elderly-care service. The marginal cost curve is SS (supply curve), and the intersection of DD and SS, E 0, corresponds to Q 0, which is the level of output consistent with social efficiency and the Pareto optimum. At that level, the net utility of institutional elderly-care service to society is maximised. If institutional elderly-care service are provided exclusively by market-based private elderly-care institutions, this fully market-based mechanism will result in an efficiency loss due to the quasi-public good attributes of institutional elderly-care service. Under the conditions of the full market mechanism, the elderly residents will determine the amount[10] of service purchased based on the maximum level of benefits they can obtain, and the intersection of dd and SS, E 1, corresponds to Q 1, which is this portion of the purchased amount. It can be seen that although the individual purchaser’s benefit is maximised, in terms of society there is a loss in the level of welfare, with AE1 E 0 being the amount lost.

Efficiency of institutional elderly-care service provision.

Given the attributes of quasi-public goods of institutional elderly-care service, to avoid the loss of efficiency entirely under the market mechanism, the government should intervene and take the government purchase of institutional elderly-care service using direct investment and subsidy, to realise an effective combination of the government and the market. As in Figure 1, without government expenditure, to satisfy the demand of buyers of institutional elderly-care service, the product supply is Q 1, the cost is OG, and the value of the efficiency is Q 1/OG. As in Figure 1, without government expenditure, to satisfy the demand of buyers of institutional elderly-care service, the product supply is Q 1, the cost is OG, and the efficiency value is Q 1/OG. To satisfy the demand for social elderly-care service, the product supply is Q 0, the cost is OF, and the efficiency value is Q 0/OF. The government invests in and subsidises the provision of institutional elderly-care service, and the marginal cost curve falls to SS-T, the level Q 0 at which social benefits can be maximised. OF is the marginal cost of institutional elderly-care service, of which the government bears the FH portion and the institutions themselves bear the OH. In this way, the government’s purchase of institutional elderly-care service is an effective Pareto improvement, which is conducive to the maximisation of benefits (Zhang & Wang, 2012). At this point, the cost of elderly-care services provided by the institutions is reduced by GH from OG to OH, and the efficiency value is Q 0/(OG-GH) which is Q 0/OH. Because Q 0 > Q 1 and OH < OG, the efficiency value of the elderly institutions after the government investment, Q 0/OH, is greater than the efficiency value Q 1/OG before the investment. For the institutions providing institutional elderly-care service, the cost reduction is accompanied by an increase in the supply of the product, and therefore, the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service increases. However, in the case of institutional elderly-care service for society, is the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service improved after the equilibrium point changes from E 1 to E 0? That is, it is uncertain whether Q 0/OF is greater than Q 1/OG. This depends on the respective growth rates of demand and supply, or on the elasticity of demand and supply. The two main forms of government financial investment in institutional elderly-care care are direct government investment and fiscal subsidies. In order to examine whether government expenditure can improve the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service and the differences in the impact of the two different types of government direct investment and fiscal subsidies on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Government direct investments have a significant positive effect on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service (can improve the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service).

H2: Government fiscal subsidies have a significant positive effect on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service (can improve the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service).

4 Research Methodology and Data Sources

4.1 Research Methodology: DEA-Tobit Two-Stage Model

Based on Farrell’s idea of efficiency measurement and metric theory, American mathematicians Charnes et al. (1978) proposed the DEA method. DEA can measure the relative effectiveness of homogeneous and comparable multiple-input, multiple-output Decision Making Units (DMUs) (Li & Li, 2023). Decision-making units must be homogeneous meaning that they undertake similar tasks and objectives and that all decision units are under the same market conditions. More importantly, the performance indicators (both inputs and outputs) used for comparison under each decision unit can vary in intensity and scope, but the indicators must all be the same (Golany & Roll, 1989). Compared with methods such as stochastic frontier analysis, the DEA method has the following advantages: it does not require preset functions and artificial weights, and it can research multiple inputs and multiple outputs at the same time (Negahban et al., 2023). Given the characteristics of institutional elderly-care service, the DEA method is well adapted to evaluate the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. At the same time, it can avoid the problem of subjective assignment of weights, highlighting its objectivity, scientificity, and practicality.

There are two classical models for data envelopment analysis (DEA), CCR and BCC. The CCR model, created by Charnes et al. (1978), assumes the measurement of the combined technical efficiency of decision units under the condition of Constant Returns to Scale (CRS). Banker et al. (1984) proposed the BCC model, which relaxes the use of CCR, introduces the condition of Variable Returns to Scale (VRS), separates scale efficiency from DEA, and measures pure technical efficiency and scale efficiency.

The DEA method can measure the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, but it is difficult to find out its influencing factors. Therefore, other models need to be used for further research on this. Sexton et al. (1989) used a multiple regression model and Ozcan et al. (1998) used a logistic regression model. Based on the problem of restrictive distribution of DEA efficiency values (e.g., the upper limit of the efficiency value is 1), the use of regression models based on the OLS method would be biased. In order to solve this problem, Kooreman (1994) chose the more fitting dependent variable restricted Tobit model as a tool to explore the factors affecting efficiency. It is recognised and used by many scholars, and the method has been proven to be more applicable in practice. The model is as follows:

The Tobit regression model is applied to analyse the factors influencing the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. The integrated technical efficiency value, pure technical efficiency value and scale efficiency value obtained by the DEA method are used as the dependent variables respectively to examine the influence of the independent variable of government expenditure on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service.

4.2 Data Sources

The data in this article come from the survey data of institutional elderly-care service status in June 2019 by Hubei Provincial Association of Nursing Institutions. The content of the survey includes (1) basic information about the elderly-care institutions: the nature of the institution, the nature of the real estate, the area, the building area, the time of registration and the number of beds approved by the civil affairs department, etc.; (2) the service capacity: the neighbouring traffic conditions, the functional facilities of the institution, the elderly-care construction projects, the management system and standards, three major competitive advantages and the three most serious problems faced, etc.; (3) the basic information of the staff: job structure, academic structure, training, holding professional qualification certificates, etc.; (4) basic information on elderly residents: number of residents, self-care ability, etc.; (5) operation status: obtaining government subsidies and special projects, charging standards, service content, number of services, etc.; (6) Combination of medical care and nursing care. In 2019 when the survey was conducted, there were a total of 151 elderly-care institutions in Wuhan City. Among these, 2 institutions were closed, 3 were under renovation and out of operation temporarily, 2 did not start operation, 3 were in operation for less than 1 year, and 91 lacked complete data needed. After the 101 institutions that did not meet the research requirements were excluded because of the perfection and reliability of the survey data, the remaining 50 elderly-care institutions were analysed as decision-making units.

-

Consent: Authors participated in the survey as researchers at Hubei Provincial Association of Nursing Institutions, and obtained the consent from the association to use the survey data.

5 Evaluation of Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service

5.1 Selection of Indicators for Evaluating the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service

The selection of input and output indicators of the DEA method is crucial for evaluation (Ghaeminasab et al., 2023; Li et al., 2021), but the number of the input and output indicators should be strictly controlled (Ozcan et al., 1998). Six principles of purposefulness, independence, consistency, objectivity, relevance and diversity for selecting indicators and constructing an indicator system should be maintained when using the DEA method for efficiency measurement (Li & Li, 2023). Golany and Roll (1989) argue that decision making units must be homogeneous, meaning that they have similar tasks and objectives, and that all decision units are subject to the same market conditions. More importantly, the performance indicators (both inputs and outputs) used for comparison under each decision unit can vary in intensity and scope, but the indicators must be the same. The reason for caution in the selection of decision units and their indicators is the close relationship between the number of decision units and the validity of the methodology. On the one hand, the larger the sample size, the more likely it is that a higher level of the production frontier will be outlined, thus finding the DEA validity point more accurately. On the other hand, the increasing sample size will continuously reduce the degree of homogeneity of the decision units and thus affect the judgement of the DEA validity (Li & Li, 2023; Wanke et al., 2024). A general rule of thumb is that the number of DMUs ≥ 2 x the sum of the number of input-output indicators (Golany & Roll, 1989).

In terms of input indicators selection, early research on the efficiency of elderly services (Fizel & Nunnikhoven, 1992; Nyman & Bricker, 1989; Sexton et al., 1989) use the working hours of all types of staff, while later scholars (Björkgren et al., 2001; Kang & Li, 2023; Ren, 2016; Rosko et al., 1995; Shimshak et al., 2009; Yang & Chang, 2019) mostly use the number of staff in each category. In terms of the selection of output indicators, the literature is consistent, adopting the number of elderly people staying in each category as output indicators. The inputs and outputs used by former researchers in the DEA models are shown in Table 1.

The inputs and outputs used by former researchers in the DEA models

| Author (year of publication) | Inputs | Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Sexton et al. (1989) | Working hours of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, nursing aides, physical therapists, administrative staff | Days of inpatients with subsidy in hospital; Days of inpatients without subsidy in hospital |

| Nyman and Bricker (1989) | Average daily working hours of caregivers, social workers, physical therapists, and others | Number of fully cared patients, patients with assistance, patients with special needs, patients with personalized service, and home patients |

| Fizel and Nunnikhoven (1992) | Working hours of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, nursing aides | Days of fully cared patients in hospital; Days of patients with assistance in hospital |

| Rosko et al. (1995) | Number of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, nursing aides, physical therapists and others | Days of fully cared people in hospital; Days of people with assistance in hospital |

| Björkgren et al. (2001) | Number of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, nursing aides, and beds | Days of adjusted case mix in hospital |

| Shimshak et al. (2009) | Number of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, nursing aides, ancillary non-nursing professional staff, ancillary non-nursing non-professional staff and administrative staff | Total number of residents; Number of residents who are dependent on assistance with: bathing, dressing, transferring, toileting, and eating;Number of residents without a catheter, restraints or pressure sores |

| Ren (2016) | Number of administrative staff, doctors, caregivers, and others | Number of the self-care elderly, the semi-self-care elderly, the fully cared elderly |

| Yang and Chang (2019) | Number of institutions, beds, skilled workers; Number of volunteer service participants; volunteer service hours | Number of the elderly; Number of days people stay in the facility |

| Kang and Li (2023) | Number of staff; the number of beds; Capital investment | Number of people in the facility; Number of people receiving assistance and care; Business profit |

Based on previous scholars’ research, combined with the data we collected, this article extracts four items as input indicators, including the number of elderly care workers, the number of administrative managers, the number of cooks, and the number of other staff members (cleaners, security guards, etc.). On the one hand, the elderly-care care service industry is labour-intensive and capital is difficult to replace. On the other hand, compared with material costs, manpower costs are the main variable costs of elderly-care service institutions and are within the adjustable range of policymakers. Therefore, these four human cost inputs are chosen as input indicators. In addition, in contrast to previous research, this study uses the number of cooks, rather than the number of doctors, as one of the input indicators. Although the more doctors an institution has the more likely it is to be conducive to the integration of healthcare and the quality of institutional elderly-care service, cooks play a crucial role in the safety of diet, quality of life, and satisfaction with services. The survey finds that all elderly-care service institutions have cooks as a human cost input, while very few have doctors. Cooks are more essential than doctors relative to basic elderly-care services and are therefore more generalisable in measuring the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. The selection of output indicators is consistent with previous research, with the number of self-care elderly, the number of semi-care elderly, and the number of completely self-care elderly selected as output indicators. The total number of input and output indicators is 7, and the number of decision-making units is 50, which is in line with the rule of thumb that the number of decision-making units is greater than twice the number of indicators. The basic description of the inputs and outputs is shown in Table 2.

Basic description of inputs and outputs (n = 50)

| Indicator | Mean value | Standard deviation | Minimum value | Maximum value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Number of elderly care workers | 23.2 | 29.91 | 4 | 168 |

| Number of cooks | 3.22 | 4.22 | 1 | 24 | |

| Number of administrative managers | 4.02 | 4.38 | 1 | 23 | |

| Number of other staff members | 10.1 | 20.11 | 0 | 123 | |

| Output | Number of self-care elderly | 34.02 | 42.14 | 0 | 180 |

| Number of semi-care elderly | 41.08 | 53.60 | 0 | 234 | |

| Number of non-self-care elderly | 45.58 | 67.21 | 0 | 338 | |

5.2 Results of the Evaluation of Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service

Using the CCR model and BCC model of input perspective DEA, based on the sample of 50 selected elderly-care care service institutions, the integrated technical efficiency[11], pure technical efficiency, and scale efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in Wuhan are analysed.

As can be seen from Table 3, among the 50 decision-making units, 22 decision-making units have an integrated technical efficiency value of 1, which is regarded as DEA-effective, that is, the inputs and outputs of these 22 elderly care institutions have reached the relative optimum, accounting for 44% of the total number of selected samples. Among the 50 decision units, 12 of them are in weak DEA, that is, only one of the two values of technical efficiency and scale efficiency is 1, accounting for 24% of the total number of decision units. The remaining 16 decision units are non-DEA effective, accounting for 32%. As can be seen from Table 4, the mean value of the integrated technical efficiency of the 50 decision-making units is 0.829, with the lowest value being 0.146 (DMU49). Of the three efficiency values, the pure technical efficiency value is the highest, 0.928, and the pure technical efficiency value has the smallest variance from each other (standard deviation is 0.074).

DEA efficiency values of 50 elderly-care service institutions under CCR and BCC models

| Decision-making units (DMU) | Integrated technical efficiency (TE) | Pure technical efficiency (PTE) | Scale efficiency (SE) | Returns to scale (RTS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 0.654 | 0.783 | 0.834 | Drs |

| 02 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 03 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 04 | 0.518 | 0.694 | 0.745 | Irs |

| 05 | 0.503 | 1 | 0.503 | Irs |

| 06 | 0.510 | 0.667 | 0.765 | Irs |

| 07 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 08 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 09 | 0.574 | 0.877 | 0.654 | Irs |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 11 | 0.908 | 1 | 0.908 | Drs |

| 12 | 0.553 | 1 | 0.553 | Irs |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 15 | 0.935 | 1 | 0.935 | Drs |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 17 | 0.882 | 1 | 0.882 | Drs |

| 18 | 0.506 | 0.544 | 0.931 | Irs |

| 19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 20 | 0.535 | 0.682 | 0.785 | Irs |

| 21 | 0.927 | 1 | 0.927 | Irs |

| 22 | 0.970 | 0.972 | 0.998 | Irs |

| 23 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 26 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 27 | 0.881 | 0.939 | 0.938 | Drs |

| 28 | 0.715 | 0.825 | 0.866 | Drs |

| 29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 30 | 0.512 | 1 | 0.512 | Drs |

| 31 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 33 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 35 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 36 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 37 | 0.715 | 0.748 | 0.955 | Drs |

| 38 | 0.980 | 1 | 0.980 | Irs |

| 39 | 0.896 | 0.908 | 0.986 | Irs |

| 40 | 0.731 | 1 | 0.731 | Drs |

| 41 | 0.690 | 0.873 | 0.791 | Drs |

| 42 | 0.676 | 1 | 0.676 | Irs |

| 43 | 0.673 | 1 | 0.673 | Irs |

| 44 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 45 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — |

| 46 | 0.354 | 0.500 | 0.709 | Irs |

| 47 | 0.802 | 0.830 | 0.966 | Drs |

| 48 | 0.814 | 1 | 0.814 | Irs |

| 49 | 0.146 | 0.600 | 0.243 | Irs |

| 50 | 0.900 | 0.942 | 0.955 | Drs |

Note: “–” denotes constant returns to scale, Irs denotes increasing returns to scale, and Drs denotes decreasing returns to scale.

Basic description of the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service values in Wuhan (n = 50)

| Indicator | Mean value | Standard deviation | Minimum value | Maximum value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated technical efficiency (TE) | 0.829 | 0.203 | 0.150 | 1 |

| Pure technical efficiency (PTE) | 0.928 | 0.074 | 0.500 | 1 |

| Scale efficiency (SE) | 0.884 | 0.185 | 0.240 | 1 |

In terms of the returns to scale, there are 22 institutions with constant returns to scale, accounting for 44%. The scale efficiency of these institutions is optimal, with inputs and outputs increasing in the same proportion. 16 institutions, accounting for 32%, have increasing returns to scale. It means that the proportion of the increase in output is higher than the proportion of the increase in inputs in these institutions, and they can increase their current size. There are 12 institutions with diminishing returns to scale, accounting for 24%, indicating that the proportion of the increase in inputs is greater than the proportion of the increase in outputs and that inputs should be appropriately controlled.

6 Tobit Analysis of the Impact of Government Expenditure on the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service

The sample size selected in this article is small, and it is not suitable to include multiple variables in the regression model at the same time, therefore, the independent variables and control variables are first determined through the correlation analysis of each variable with the comprehensive technical efficiency. The determination of independent variables and control variables is based on the following three principles: (1) focusing on and selecting the factors influencing the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in existing research as control variables; (2) not including the input and output variables selected in the analysis of the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service; (3) the significance level of P < 0.10. Then, a Tobit regression model is fitted with the value of efficiency of institutional elderly-care service as the dependent variable, with the identified independent variables and selected control variables.

6.1 Dependent and Independent Variables

6.1.1 Dependent Variables

In order to examine the impact of government expenditure on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, this article fits three independent Tobit models with the integrated technical efficiency value (TE), pure technical efficiency value (PTE), and scale efficiency value (SE) of institutional elderly-care service in Wuhan as dependent variables, respectively.

6.1.2 Independent Variables

The government’s purchase of institutional elderly-care service is divided into public–private, public–private and public-subsidised methods, of which public–private and public-subsidised have become the mainstream models (Zhang & Wang, 2012). According to Hu (2013), the government’s purchase of institutional elderly-care service can be interpreted from both broad and narrow perspectives, with the broader meaning referring to the two forms of public–private and public-subsidised, and the narrower meaning referring to public–private only. The “government purchase of institutional elderly-care service” in this article is based on a broad perspective, which includes both public–private, private–private and public-subsidised (government subsidies to private-private institutions), as well as government subsidies to public-private institutions for elderly-care beds that are open to the community. In terms of the specific ways in which the government purchases institutional elderly-care service, in addition to providing financial support to elderly-care service institutions, the government’s provision of interest-free loans to elderly-care service institutions carrying out the construction of facilities and equipment, and the implementation of tax incentives are all positive initiatives of the government’s cooperative mechanism for the purchase of institutional elderly-care service (Kang & Lv, 2016). The main purchasing methods can be divided into three categories: direct government investment, fiscal subsidies (five guarantees subsidy, bed operation subsidy, construction subsidy, fire protection subsidy, upgrading subsidy, etc.), and tax and fee concessions. Given that data on tax and fee concessions are difficult to obtain, government expenditure for institutional elderly-care is mainly government direct investment and fiscal subsidies in this paper. Initially, the two are used as independent variables, and then the independent variables for fitting the Tobit model are determined based on the results of the correlation analysis.

Given that the value of integrated technical efficiency does not conform to a normal distribution, therefore, for the continuous variables of government direct investment and fiscal subsidies, the correlation analysis of the variables and integrated technical efficiency is unfolded by Spearman correlation, as shown in Table 6. The results show that fiscal subsidies are positively correlated with the integrated technical efficiency of elderly-care service institutions, and are significant at the test level of 0.01 (P = 0.006). Although government direct investment is positively related to the integrated technical efficiency of elderly-care service institutions, it is not statistically significant. This means that the theoretical hypothesis H1 is not valid. Therefore, the independent variable was determined to be fiscal subsidies.

6.2 Control Variables

In order to reduce the error caused by the model setting, this article introduces other factors affecting the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service as control variables. In the literature of previous research on variables affecting the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, scholars have different views. They believe that the variables include: the nature of the institution, the size of the institution, the management factors, the environmental factors, the fixed assets of the institution, the human resource factors, the quality of care, and the combination of health care and nursing care, etc., as shown in Table 5. Drawing on the results of previous research, 10 specific indicators in six areas are initially selected as control variables, including the nature of the institution, fixed assets and scale indicators (floor area, building area, number of approved beds), operation status indicators (years of operation, number of subsidised beds, occupancy rate, average fee rate), medical and nursing care combination indicators (own hospital), environmental indicators (location of the institution), and human resource development emphasis indicators (number of staff training sessions).

Variables affecting the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service

| Author (year of publication) | Variables affecting the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service |

|---|---|

| Sexton et al. (1989) | Poor management; sudden prolongation of management time; decline in quality of inputs; increase in quality of outputs; high employment rates; occupants constrained |

| Nyman and Bricker (1989) | Nature of institutional profitability |

| Fizel and Nunnikhoven (1992) | Nature of institutional profitability |

| Kooreman (1994) | Labour inputs |

| Rosko et al. (1995) | Management and environmental factors |

| Ozcan et al. (1998) | Ownership and size |

| Björkgren et al. (2001) | Size of institution; nurses with practical experience; efficient internal management; resource allocation |

| Shimshak et al. (2009) | Quality of care |

| Garavaglia et al. (2010) | Nature of the institution |

| Wu (2011) | Type of recreational facility; number of managers |

| Ren (2016) | Total value of fixed assets of the institution; quality factors such as whether it is affiliated with a hospital or not |

| Yang and Chang (2019) | Number of professional and technical skilled personnel; number of beds |

| Kang and Li (2023) | Nature of the elderly-care care institution |

Data source: Based on relevant literature.

Given that the integrated technical efficiency values do not conform to a normal distribution, the correlation between the variables and the integrated technical efficiency was analysed by Spearman’s correlation for continuous variables (Table 6). For binary variables, the rank sum test was used to determine the correlation between the control variables and the dependent variable integrated technical efficiency (Table 7).

Spearman’s correlation analysis of variables with integrated technical efficiency values

| Floor area | Building area | Years of operation | Approved beds | Institutional occupancy rate | Training sessions | Subsidised beds | Average fee rate | Government direct investment | Fiscal subsidies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | 0.220 | 0.126 | −0.020 | 0.242* | 0.329** | 0.084 | 0.125 | −0.318** | 0.140 | 0.385*** |

| P-value (bilateral) | 0.125 | 0.384 | 0.889 | 0.091 | 0.020 | 0.561 | 0.386 | 0.024 | 0.333 | 0.006 |

Note: * indicates P < 0.10; ** indicates P < 0.05; *** indicates P < 0.01.

Rank-sum test of the variables with the integrated technical efficiency values

| Variables | n | Rank mean | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whether it is in the central city | Yes (=1) | 45 | 24.72 | 0.237 |

| No (=0) | 5 | 32.50 | ||

| Whether it is privately-run | Yes (=1) | 36 | 28.06 | 0.038** |

| No (=0) | 14 | 18.93 | ||

| Whether it has a hospital | Yes (=1) | 10 | 23.95 | 0.694 |

| No (=0) | 40 | 25.89 | ||

Note: ** indicates P < 0.05.

As shown in Table 6, the results of Spearman’s correlation analysis indicate that the fixed assets and scale indicators (floor area, building area, number of approved beds) have a positive correlation with the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, however, only the relationship between the number of beds and the integrated technical efficiency is significant at the test level of 0.10. Among the indicators of the operation status (years of operation, number of subsidised beds, occupancy rate, and average fee rate), the average fee rate is significantly and negatively correlated with the integrated technical efficiency of the elderly-care service institutions (P = 0.024), the occupancy rate of elderly-care service institutions significantly and positively correlated with the integrated technical efficiency of the elderly-care service institutions (P = 0.020). The indicator of the degree of attention to human resources development (number of staff training sessions) is positively correlated with the integrated technical efficiency of elderly-care service institutions but is not statistically significant.

As shown in Table 7, the correlation analysis between the location environment of institutional elderly-care service (whether it is in the central city or not), the nature of elderly-care institutions (whether it is privately-run or not), the healthcare integration situation (whether it has a hospital or not) and the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is conducted by using the rank-sum test in the non-parametric test. The results show that the effects of location environment of whether the elderly-care service institutions are in the central city (P = 0.237) and healthcare integration situation (P = 0.694) on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service are not statistically significant. In contrast, there is a significant positive correlation between elderly-care service institutions according to their nature and the value of integrated service efficiency (P = 0.038), indicating that the different natures of elderly-care service institutions have a significant positive impact on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. Moreover, the rank-mean value of efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in the private sector (28.06) is 48.23% higher than the rank-mean value of efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in the public sector (18.93).

Through Spearman correlation analysis and rank sum test in non-parametric tests, three control variables are selected: the nature of the elderly-care service institution, the occupancy rate and the average fee rate at P < 0.05.

6.3 Results of Tobit Analysis

According to the results of the relevant analysis, Tobit regression analysis is conducted with fiscal subsidy (P < 0.05) as the independent variable, the nature of elderly-care service institutions, occupancy rate of elderly-care service institutions, and average fee rate at P < 0.05 as the control variables, and the integrated technical efficiency (TE) of elderly-care service institutions, the pure technical efficiency (PTE), and scale efficiency (SE) as the dependent variables. The form of the model is as follows:

Stata software was applied to fit three independent Tobit models with the integrated technical efficiency value, pure technical efficiency value and scale efficiency value of institutional elderly-care service as the dependent variables respectively, and the model results are shown in Table 8.

Tobit model estimation results of the effect of fiscal subsidies on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service

| Variables | Integrated technical efficiency (TE) | Pure technical efficiency (PTE) | Scale efficiency (SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | |

| Fiscal subsidies | 0.253*** | 0.029 | 0.187*** | 0.016 | 0.118 | 0.163 |

| Occupancy rate | 0.319*** | 0.004 | −0.019 | 0.787 | 0.378*** | 0.000 |

| Average fee rate | 0.000199 | 0.949 | 0.000580 | 0.779 | −0.000446 | 0.846 |

| Nature of institution | 0.150*** | 0.012 | 0.091*** | 0.021 | 0.099*** | 0.024 |

Note: *** indicates P < 0.01.

The results show that the effect of the independent variable fiscal subsidy on the scale efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is not statistically significant under the condition of controlling other variables. However, the effect on the integrated technical efficiency and pure technical efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is significant (P < 0.05), and the regression coefficients are 0.253 and 0.187 respectively, indicating that for every 10,000 yuan increase in the government fiscal subsidy, the value of integrated technical efficiency and pure technical efficiency of institutional elderly-care service will be increased by 0.253 and 0.187 respectively. This means that the theoretical hypothesis H2 is valid. In addition, the occupancy rate has a significant positive effect on the integrated technical efficiency and scale efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. The nature of elderly-care service institutions has a significant effect on the three kinds of efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, and the private category of elderly-care service institutions is higher than the public category by an average of 0.150, 0.091, and 0.021 in the integrated technical efficiency, pure technical efficiency, and scale efficiency.

Chen and Zhang (2017) argue that the fiscal subsidy methods of China’s institutional elderly-care service can be divided into two categories: the supplementary demand side (the elderly enjoying the services) and the subsidised side (the elderly-care service institutions). And how to choose the fiscal subsidy method scientifically has been a difficult problem plaguing policy practice. Different scholars have different views on this, and Ding (2012) argues that a combination of the supplementary demand side and the subsidised side is better suited. Zhang and Lin (2012), on the other hand, advocate a shift from “bricks subsidy” and “beds subsidy” to “heads subsidy.” Based on the perspective of the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, this article further explores the appropriateness of the different subsidy modes of “bricks subsidy,” “beds subsidy,” and “heads subsidy.” We further refine the fiscal subsidies into construction subsidy (for bricks), bed subsidy (for beds), five guarantees subsidy (for headcount) and other subsidies. Among them, the construction subsidy and bed subsidy are to supplement the supply side, while the five guarantees subsidy is to supplement the demand side. Three independent Tobit models are further fitted with the integrated technical efficiency, pure technical efficiency and scale efficiency of institutional elderly-care service as dependent variables, and the model results are shown in Table 9. The results show that: on the one hand, the model is robust, and the effects of control variables such as the nature of elderly-care service institutions, occupancy rate, and the average fee rate on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service are in line with Table 8. On the other hand, controlling for other variables, the effect of beds subsidy on the integrated technical efficiency, pure technical efficiency, and scale efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is significant (P < 0.05), with regression coefficients of 0.00270, 0.00184, and 0.00133, respectively. The effect of construction subsidy, five-guarantee subsidy, and other subsidies on the scale efficiency are not statistically significant.

Tobit model estimation results of the impact of “bricks subsidy,” “beds subsidy” or “heads subsidy” on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service

| Variables | Integrated technical efficiency (TE) | Pure technical efficiency (PTE) | Scale efficiency (SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | |

| Construction subsidy | 0.00259 | 0.123 | 0.000960 | 0.392 | 0.00182 | 0.141 |

| Bed subsidy | 0.00270*** | 0.004 | 0.00133*** | 0.030 | 0.00184*** | 0.007 |

| Five guarantees subsidy | −0.00554 | 0.591 | 0.000878 | 0.209 | −0.00118 | 0.123 |

| Other subsidies | 0.00254 | 0.484 | 0.00243 | 0.321 | 0.000377 | 0.887 |

| Occupancy rate | 0.291*** | 0.006 | −0.031 | 0.648 | 0.356*** | 0.000 |

| Average fee rate | 0.000364 | 0.900 | 0.000664 | 0.735 | −0.000306 | 0.886 |

| Nature of institution | 0.202*** | 0.001 | 0.139*** | 0.001 | 0.120*** | 0.008 |

Note: *** indicates P < 0.01.

7 Conclusions and Recommendations

7.1 Research Conclusions

The efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in Wuhan is analysed using the DEA method, and it is found that the integrated technical efficiency is at a high level, but there is a large difference between elderly-care service institutions; among the three efficiency values of institutional elderly-care service, the pure technical efficiency is the highest, and the differences among elderly-care service institutions are small. Correlation analysis shows that among government inputs, the effect of government direct investment on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is not statistically significant. The results of Tobit regression analysis show that under the condition of controlling other variables, fiscal subsidies can improve the integrated technical efficiency and pure technical efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, and for every 10,000 yuan increase in the input of fiscal subsidies by the government finance, the value of the integrated technical efficiency and the value of the pure technical efficiency of institutional elderly-care service will be increased by 0.253 and 0.187, respectively. Among the forms of fiscal subsidies, the effect of “beds subsidy” on the integrated technical efficiency, pure technical efficiency, and scale efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is statistically significant, while the effect of “bricks subsidy” and “heads subsidy” on the scale efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is not statistically significant. The efficiency of institutional elderly-care service is higher in the private sector than in the public sector, and fiscal expenditure on private institutions can better fulfil the role of improving the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service.

7.2 Policy Recommendations

7.2.1 Prefer Fiscal Subsidies Over Direct Government Investments

The main ways for the government to purchase institutional elderly-care service are direct investment and fiscal subsidies. The research shows that among the government inputs, there are differences in the effects of government direct investment and government fiscal subsidies on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. Government direct investment has no significant effect on the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service, while government fiscal subsidies have a significant positive effect on both integrated technical efficiency and pure technical efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. Therefore, when the government purchases institutional elderly-care service, it should make appropriate adjustments in the purchasing method: more use of fiscal subsidies and avoiding direct investment.

7.2.2 Focus on the Positive Role of “Beds Subsidy” in Improving the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service

The scientific choice of fiscal subsidies has been a difficult problem that has plagued policy practice. Different scholars have different views on this, and Ding (2012) argues that a combination of the supplementary demand side and the subsidised side is better suited. Zhang and Lin (2012), on the other hand, advocate a shift from “bricks subsidy” and “beds subsidy” to “heads subsidy.” At the same time, fiscal subsidies can be diversified. In addition to adopting special forms such as construction subsidies, upgrading subsidies, and bed operation subsidies, a shift can be made from “bricks subsidy” and “beds subsidy” to “heads subsidy” on the basis of the actual number of elderly people served.

7.2.3 Guide Social Forces into the Field of Elderly-Care Services through Fiscal Subsidies

Research has shown that the private sector is on average 0.150, 0.091, and 0.021 higher than the public sector in terms of integrated technical efficiency, pure technical efficiency and scale efficiency. The efficiency of institutional elderly-care service in the private sector is higher than that of the public sector, and the fiscal subsidies have guided the social forces to enter the field of elderly-care services, so that they can better play the role of improving the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. There is still a big gap between the existing elderly-care service beds in Wuhan and the lower limit of 50–70 elderly-care service beds for 1,000 elderly people in developed countries. In order to alleviate the contradiction between the supply and demand of institutional elderly-care service, the government should encourage different natures of elderly-care service institutions to enter the field of elderly-care services, strengthen the policy guidance, financial support, market cultivation and supervision and management, and fully mobilise all aspects of society to actively participate in the development of the career of elderly-care services. The government can also purchase institutional elderly-care service from private elderly-care service institutions in the same way that it purchases institutional elderly-care service for the “three have-nots” in urban areas and the “five guarantees” in rural areas that are covered by public elderly-care service institutions. For private elderly-care service institutions that provide the same service, the government can provide subsidies equal to those provided by public elderly-care service institutions.

It has to be acknowledged that the article has some limitations. Firstly, our literature review focused on articles in English and Chinese, overlooking the contributions of articles published in other languages. Secondly, this article focuses on whether the variable of government expenditure, which has been neglected in previous research, can improve the efficiency of institutional elderly-care service. We conducted our study taking Wuhan as an example with an effective sample of only 50 institutions, and the conclusions we reached and the suggestions we made may offer some inspiration for other regions, but it is difficult to determine whether they are actually applicable. Thus, future studies can apply the DEA-Tobit two-stage model to explore the impact of government expenditure on the efficiency of more institutions of the same kind and compare the results with the ones from the current study.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the National Social Science Fund of China for its support and to Hubei Provincial Association of Nursing Institutions for its help.

-

Funding information: This research received the specific grant. It was supported by the project of the National Social Science Fund of China “Research on the Coordination Mechanism of Atypical Labour Relations” (Project No. 2020XSH011).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. ZR, as the first author of this article, was responsible for the research design, data collection and analysis, and article writing. ZH, as the corresponding author, was responsible for supervising and guiding, reviewing, and revising the article.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

References

Banker, R. D., Charnes, A., & Cooper, W. W. (1984). Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Management Science, 30(9), 1078–1092.10.1287/mnsc.30.9.1078Search in Google Scholar

Björkgren, M. A., Häkkinen, U., & Linna, M. (2001). Measuring efficiency of long-term care units in Finland. Health Care Management Science, 4, 193–200.10.1023/A:1011444815466Search in Google Scholar

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), 429–444.10.1016/0377-2217(78)90138-8Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Z. Y., & Zhang, W. (2017). Measurement of fiscal subsidy methods and standards in the marketisation of elderly services in China. Seeker, 37(1), 144–148.Search in Google Scholar

Ding, X. N. (2012). Research on government compensation mechanism of privately-run non-profit senior care institutions – An analysis based on S citizen-run non-profit senior care institutions. Academic Journal of Zhongzhou, 34(6), 94–98.Search in Google Scholar

Dulal R. (2017). Technical efficiency of elderly-care institutions: Do five-star quality ratings matter?. Health Care Management Science, 21(3), 393–400.10.1007/s10729-017-9392-8Search in Google Scholar

Ekram Nosratian, N., & Taghavi Fard, M. T. (2023). A proposed model for the assessment of supply chain management using DEA and knowledge management. Computational Algorithms and Numerical Dimensions, 2(3), 136–147.Search in Google Scholar

Fizel L., & Nunnikhoven S. (1992). Technical efficiency of for-profit and non-profit elderly-care institutions. Managerial and Decision Economics, 13(5), 429–439.10.1002/mde.4090130507Search in Google Scholar

Garavaglia G., Lettieri E., & Agasisti T. (2010). Efficiency and quality of care in nursing homes: an Italian case study. Health Care Management Science, 23(5), 1.10.1007/s10729-010-9139-2Search in Google Scholar

Gan, X. C., Abduguli A., & Cai, Y. Y. (2023). Research on the operational efficiency of urban and rural elderly care institutions in china against the background of population aging–Analysis based on the three-stage SBM-DEA model. Price: Theory & Practice, 43(8), 132–136.Search in Google Scholar

Ghaeminasab, B., Rostamy-Malkhalifeh, M., Hosseinzadeh Lotfi, F., Behzadi, M. H., & Navidi, H. (2023). Equitable resource allocation combining coalitional game and data envelopment analysis. Journal of Applied Research on Industrial Engineering, 10(4), 541–552.Search in Google Scholar

Golany, B., & Roll, Y. (1989). An application procedure for DEA. Omega, 17(3), 237–250.10.1016/0305-0483(89)90029-7Search in Google Scholar

Gui, S. X. (2001). A rational adjustment to the functional structure of aged support agencies. Journal of East China Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences), 49(7), 97–101.Search in Google Scholar

He, W. J., Yang, C. Y., & Liu, X. T. (2008). Optimising the allocation and accelerating the development – Survey and analysis on the allocation status of institutional aged-care resources in Zhejiang Province. Contemporary Social Sciences Perspectives, 50(1), 29–33.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, W. (2013). Purchasing or subsidy: The practical meaning of government purchasing social services from NGOs. Journal of University of Science and Technology Beijing (Social Sciences Edition), 29(4), 91–94.Search in Google Scholar

Ioviţă, D. C. (2012). Ways of increasing degree of the quality of life in the institutions for elderly people. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 3999–4003.10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.186Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, Y. X., & Si, W. (2006). Analysis of the factors influencing on elder’s preferences for social care – empirical evidence from Zhejiang province. Population & Economics, 27(3), 8–12.Search in Google Scholar

Kang, R., & Li, M. (2023). Does the participation of the private sector improve the efficiency of elderly care institutions? A case study of Beijing. Social Policy Research, 8(2), 28–42.Search in Google Scholar

Kang, R., & Lv, X. J. (2016). Research on public-private construction of institutional elderly-care service under the perspective of government purchase services. Social Sciences in Guangxi, 32(2), 130–134.Search in Google Scholar

Kooreman, P. (1994). Nursing home care in The Netherlands: A nonparametric efficiency analysis. Journal of Health Economics, 13(3), 301–316.10.1016/0167-6296(94)90029-9Search in Google Scholar

Li, L, & Li, D. (2023) Efficiency evaluation of urban employee’s basic endowment insurance expenditure in China based on a three-stage DEA model. Plos One, 18(3), e0279226.10.1371/journal.pone.0279226Search in Google Scholar

Li, Z. G., Si, X., Ding, Z. Y., Li, X., Zheng, S., Wang, Y. X., Wei, H., Guo, Y., & Zhang, W. (2021). Measurement and evaluation of the operating efficiency of China’s basic pension insurance: Based on three-stage DEA model. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 14, 3333–3348.10.2147/RMHP.S320479Search in Google Scholar

Liu, B., & Xiao, R. K. (2012). Market or system:The case study of business situation and difficulties about socialized institutions for elderly. Population & Economics, 33(1), 22–29.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, L., Chen, G., & Zheng, X. Y. (2008). Strategies for the future development of socialised elderly care institutions in China. Chinese Journal of Gerontology, 28(2), 412–414.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, K. H., & Saen, R. F. (2012). Measuring corporate sustainability management: A data envelopment analysis approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(1), 219–226.10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.08.024Search in Google Scholar

Ma, Y. R., Yi, D., & Huang, Y. (2017). Research on the service efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions in China and its tempora-spatial evolution. China Soft Science, 32(12), 1–10.Search in Google Scholar

Mu, G. Z. (2012). Dilemmas and countermeasures for the development of institutionalised aged care in China. Journal of Central China Normal University:Humanities and Social Sciences, 58(2), 31–38.Search in Google Scholar

Musgrave, R. A. (1939). The voluntary exchange theory of public economy. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 53(2), 213–237.10.2307/1882886Search in Google Scholar

Negahban, L., Banimahd, B., Hosseini, S. H., & Shokri Cheshmeh Sabzi, A. (2023). Ranking of companies in generating operating cash flows based on data envelopment analysis. International Journal of Research in Industrial Engineering, 12(4), 364–374.Search in Google Scholar

Ni Luasa, S., Dineen, D., & Zieba, M. (2018). Technical and scale efficiency in public and private Irish nursing homes–a bootstrap DEA approach. Health Care Management Science, 21, 326–347.10.1007/s10729-016-9389-8Search in Google Scholar

Nyman, J. A., & Bricker, D. L. (1989). Profit incentives and technical efficiency in the production of nursing home care. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 71(4), 586–594.10.2307/1928100Search in Google Scholar

Ozcan, Y. A., Wogen, S. E., & Mau, L. W. (1998). Efficiency evaluation of skilled nursing facilities. Journal of Medical Systems, 22, 211–224.10.1023/A:1022657600192Search in Google Scholar

Rasinojehdehi, R., & Najafi, S. E. (2024). Advancing risk assessment in renewable power plant construction: An integrated DEA-SVM approach. Big Data and Computing Visions, 4(1), 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

Ren, J. (2016). Efficiency of care in elderly-care institutions: A Xiamen case study. Population & Economics, 37(2), 58–68.Search in Google Scholar

Rosko, M. D., Chilingerian, J. A., Zinn, J. S., & Aaronson, W. E. (1995). The effects of ownership, operating environment, and strategic choices on nursing home efficiency. Medical Care, 33(10), 1001–1021.10.1097/00005650-199510000-00003Search in Google Scholar

Roy, D., Cho, S., & Avdan, G. (2024). Data envelopment analysis (DEA) for improving ergonomics and workplace performance. Journal of Applied Research on Industrial Engineering, 11(1), 24–36.Search in Google Scholar

Savas E. S. (2002). Privatisation and corporate sector partnerships. Beijing: Renmin University of China Press.Search in Google Scholar

Samuelson, P. A. (1954). The pure theory of public expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 36(4), 387–389.10.2307/1925895Search in Google Scholar

Sexton, T. R., Leiken, A. M., Sleeper, S., & Coburn, A. F. (1989). The impact of prospective reimbursement on nursing home efficiency. Medical Care, 27(2), 154–163.10.1097/00005650-198902000-00006Search in Google Scholar

Shimshak, D. G., Lenard, M. L., & Klimberg, R. K. (2009). Incorporating quality into data envelopment analysis of nursing home performance: A case study. Omega, 37(3), 672–685.10.1016/j.omega.2008.05.004Search in Google Scholar

Tran, A., Nguyen, K. H., Gray, L., & Comans, T. (2019). A systematic literature review of efficiency measurement in elderly-care institutions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2186–2186.10.3390/ijerph16122186Search in Google Scholar

Wang, J., & Zhang, P. F. (2024). Study on service supply strateies of social work embedded in elderly care institutions:A case analysis based on a government procurement service. Population and Society, 40(2), 42–50.Search in Google Scholar

Wanke P., Antunes J., Tan Y., & Ahmad E. S. (2024). Performance evaluation and lockdown decisions of the UK healthcare system in dealing with COVID-19: A novel unbiased MCDM score decomposition into latent vagueness and randomness components. Decision making: Applications in Management and Engineering, 7(1), 473–493.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, M. (2011). Research on the development of nursing home care: Demand and supply (pp. 121–145). Economic Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, W. W., & Chang, C. (2019). Analysis of differences in efficiency and choice preferences of elderly care institutions. Statistics & Decision, 35(8), 64–67.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, N. Y., & Wang, C. Y. (2012). Policy analysis of China’s government purchase of institutional elderly-care service. Reform of Economic System, 30(2), 21–25.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, W., & Zhang, C. L. (2010). Current problems and countermeasures facing the socialisation of China’s elderly services–thinking based on local elderly service work. Modern Economic Research, 29(5), 39–42.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, X., & Lin, T. (2012). Grant subsidy according to “Bricks”, “Beds” or “Heads”: A case study of institute for the aged in X County of Zhejiang Province. Social Security Studies, 5(4), 39–48.Search in Google Scholar

Zhou, Y., & Chai, Z. J. (2015). The efficiency of elder-caring organizations in Ningbo. Journal of Ningbo University: Liberal Arts Edition, 37(5), 79–84.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Political Turnover and Public Health Provision in Brazilian Municipalities

- Examining the Effects of Trade Liberalisation Using a Gravity Model Approach

- Operating Efficiency in the Capital-Intensive Semiconductor Industry: A Nonparametric Frontier Approach

- Does Health Insurance Boost Subjective Well-being? Examining the Link in China through a National Survey

- An Intelligent Approach for Predicting Stock Market Movements in Emerging Markets Using Optimized Technical Indicators and Neural Networks

- Analysis of the Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion in Promoting Inclusive Growth: Mechanism and Statistical Verification

- Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size under Turnover Tax: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on SMEs

- Re-investigating the Impact of Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development, Institutional Quality, and Globalization on Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries

- A Compliance Return Method to Evaluate Different Approaches to Implementing Regulations: The Example of Food Hygiene Standards

- Panel Technical Efficiency of Korean Companies in the Energy Sector based on Digital Capabilities

- Time-varying Investment Dynamics in the USA

- Preferences, Institutions, and Policy Makers: The Case of the New Institutionalization of Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance in Colombia

- The Impact of Geographic Factors on Credit Risk: A Study of Chinese Commercial Banks

- The Heterogeneous Effect and Transmission Paths of Air Pollution on Housing Prices: Evidence from 30 Large- and Medium-Sized Cities in China

- Analysis of Demographic Variables Affecting Digital Citizenship in Turkey

- Green Finance, Environmental Regulations, and Green Technologies in China: Implications for Achieving Green Economic Recovery

- Coupled and Coordinated Development of Economic Growth and Green Sustainability in a Manufacturing Enterprise under the Context of Dual Carbon Goals: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality

- Revealing the New Nexus in Urban Unemployment Dynamics: The Relationship between Institutional Variables and Long-Term Unemployment in Colombia

- The Roles of the Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate in the Current Account Balance

- Cleaner Production: Analysis of the Role and Path of Green Finance in Controlling Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

- The Research on the Impact of Regional Trade Network Relationships on Value Chain Resilience in China’s Service Industry

- Social Support and Suicidal Ideation among Children of Cross-Border Married Couples

- Asymmetrical Monetary Relations and Involuntary Unemployment in a General Equilibrium Model

- Job Crafting among Airport Security: The Role of Organizational Support, Work Engagement and Social Courage

- Does the Adjustment of Industrial Structure Restrain the Income Gap between Urban and Rural Areas

- Optimizing Emergency Logistics Centre Locations: A Multi-Objective Robust Model

- Geopolitical Risks and Stock Market Volatility in the SAARC Region

- Trade Globalization, Overseas Investment, and Tax Revenue Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Can Government Expenditure Improve the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service? – Take Wuhan as an Example

- Media Tone and Earnings Management before the Earnings Announcement: Evidence from China

- Review Articles

- Economic Growth in the Age of Ubiquitous Threats: How Global Risks are Reshaping Growth Theory

- Efficiency Measurement in Healthcare: The Foundations, Variables, and Models – A Narrative Literature Review

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm

- Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy

- Special Issue: Economic Implications of Management and Entrepreneurship - Part II

- Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study on Entrepreneurial Tendency of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA in the Context of the Interactive Model

- Bridging Brand Parity with Insights Regarding Consumer Behavior

- The Effect of Green Human Resources Management Practices on Corporate Sustainability from the Perspective of Employees

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation in Economics and Management Decision - Part II

- High-Quality Development of Sports Competition Performance Industry in Chengdu-Chongqing Region Based on Performance Evaluation Theory

- Analysis of Multi-Factor Dynamic Coupling and Government Intervention Level for Urbanization in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt

- The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Technological Innovation of Enterprises: Based on Empirical Evidences of the Implementation of Pollution Charges in China

- Environmental Social Responsibility, Local Environmental Protection Strategy, and Corporate Financial Performance – Empirical Evidence from Heavy Pollution Industry

- The Relationship Between Stock Performance and Money Supply Based on VAR Model in the Context of E-commerce

- A Novel Approach for the Assessment of Logistics Performance Index of EU Countries

- The Decision Behaviour Evaluation of Interrelationships among Personality, Transformational Leadership, Leadership Self-Efficacy, and Commitment for E-Commerce Administrative Managers

- Role of Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurship Across the Diverse Economic Stages: Insights from GEM and GLOBE Data

- Performance Evaluation of Economic Relocation Effect for Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations: Evidence from China

- Functional Analysis of English Carriers and Related Resources of Cultural Communication in Internet Media

- The Influences of Multi-Level Environmental Regulations on Firm Performance in China

- Exploring the Ethnic Cultural Integration Path of Immigrant Communities Based on Ethnic Inter-Embedding

- Analysis of a New Model of Economic Growth in Renewable Energy for Green Computing

- An Empirical Examination of Aging’s Ramifications on Large-scale Agriculture: China’s Perspective

- The Impact of Firm Digital Transformation on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: Evidence from China

- Accounting Comparability and Labor Productivity: Evidence from China’s A-Share Listed Firms