Abstract

Significant corporate tax reform was agreed upon by more than 140 nations in 2021, with implementation set for 2023 and beyond. Many people throughout the globe are discussing the possible effects of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) planned adjustment to the global minimum tax (GMT) on their respective economies. The OECD has formulated a “two-pillar” scheme for international tax rules for 137 countries and regions within the overall framework. Pillar 2 is to set the tax rate at 15%, the world’s lowest corporate tax. The GMT is a reclassification of the taxing authority mechanism for the profits of multinational corporations, which has made significant adjustments to the global tax coordination and governance mechanism. People living in China and earning money from China must pay university fees, which are all of a nationality. Progressive rates ranging from 3 to 45% apply to the complete income. Therefore, taking the initiative in policy is crucial to address this challenge actively. This article makes an in-depth assessment and prediction of the impact of the GMT reform on China’s tax system and enterprises and proposes countermeasures. However, approximately 20% of the earnings can be exposed to the 15% tax rate that governments can apply. If the entire process is mixed in tandem, the tax rate equals 0.2%. Hence, an important amount of tax revenue can proceed down the drain. From the numerical outcomes, the minimum tax with jurisdictional blending was set at 12.5% under Pillar 2; the disparity between the sample’s top and lowest EATRs would decrease by 2.8% points.

1 Introduction

The global minimum tax (GMT) is a concept of “two pillars” published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in October 2019. The plan proposal aroused strong reactions from various countries. In December 2021, the European Commission will publish the Global Minimum Corporate Tax Implementation Guidelines to ensure the smooth implementation of the world minimum tax within the European Union. Currently, 138 countries support the GMT policy as part of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan. The World Minimum Tax Reform Package breaks traditional international tax rules and allows the country of residence to tax intangible income and low tax rates in the source country, sharing the negative income. This scheme protects the tax base and promotes international tax equity, but most of the additional tax revenue is lost. Most flows go to the countries where the TNCs are located rather than those that generate profits. According to The Economist, the G7 receives more than 60% of fiscal revenue from the minimum tax rate. Through the discussion of the world’s minimum tax reform and the erosion of China’s tax base, this article reveals the positive role of the minimum tax reform in solving the problem of tax base erosion in China and provides useful enlightenment for improving China’s tax system.

The world’s minimum tax focuses on large multinational corporations with high-profit margins. In the Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 schemes published by the OECD in 2009, the 100 largest multinational corporations in the world, or multinational corporations with a group of more than 750 million euros, are taxed. Apple and others are eye-catching. According to Beer et al., (2020) such multinational digital enterprises have taken advantage of the loopholes between tax havens and the tax systems of various countries through related-party transactions and transfer pricing of intangible assets and have adopted various models to achieve amazing tax haven effects. For example, from 2009 to 2011, Apple earned $38 billion in pre-tax profits worldwide. In 2017, Google’s annual revenue reached £7.6 billion, and it paid only £49 million in taxes that year, or 0.6%, when it paid only $21 million. Amazon’s annual revenue is £8.7 billion, with taxes of just £4.5 million and a tax burden of 0.1%. These figures show that multinational tech giants have achieved extremely low or even zero tax rates through complex tax planning and have made huge profits on a global scale.

International tax reform is at crossroads, and China, with its growing economy and big role in trade and investment, is at the crossroads. The OECD’s planned GMT has the potential to have far-reaching effects on economies throughout the globe by changing the way multinational corporations are taxed, and knowing how China’s tax policy, system, and possible reactions to the reform work in this context is crucial. All sorts of taxes, including value-added tax (VAT), corporate income tax, individual income tax, and municipal taxes are a part of China’s complex tax system. As time has progressed, China has implemented changes to update its tax system, increase compliance, and promote economic development. Moreover, the country’s tax policies have played a crucial role in encouraging economic growth, industrialization, and international investment attraction.

After collating the relevant data of the world’s top 500 companies and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange from Wang et al. (2023), it was found that 236 Chinese companies, such as Alibaba, Noah Fortune, and Midea Real Estate, have set up companies in tax havens. Its “tax haven” investment accounted for 24% of the total foreign investment, amounting to 620.606 billion U.S. dollars. Suppose the Pillar 2 package, which the United States strongly supports, is used as the world’s minimum tax threshold. In that case, it will involve 38 large Chinese enterprises in 13 industries, such as technology services, finance, and real estate. In addition, many multinational companies in China have consolidated revenues of more than 750 million euros, involving 17 categories, 29 subcategories, and 198 enterprises. Under the one-pillar levy scheme, 14 technology service companies such as Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu will be taxed, accounting for 34% of the total number of enterprises registered in “tax havens” in China. According to Cheng & Zhou (2022) examination, if the second pillar is applied, the subject of taxation will be expanded to 42 scientific and technological service industries, and the subject of taxation will be further expanded. Implementing the GMT scheme means that the tax rate will rise sharply from 0 to 15%, putting huge financial pressure on Chinese companies registered in tax havens, especially in the technology service industry. The biggest impact is that the existing tax avoidance channels will be blocked, and the innovation and development of the technology industry and enterprises will inevitably lag. On July 1, 2021, the OECD (2021) announced the establishment of a comprehensive framework consisting of 130 countries and territories to form “two pillars.” It aims to build a fairer and more sustainable tax system to promote the growth and prosperity of the world economy. Since then, G20 countries have expressed their support for the plan, saying it will be enacted in 2022 and implemented in 2023. So far, 136 countries and territories have supported the plan, but some have not yet joined.

The “two pillars” of the “Two Pillars” approach, the GMT, focus on base erosion and profit shifting. Tandon (2022) illustrated under the program, it was decided to set the effective tax rate (ETR) of large multinational groups at 15%, the lowest level in the world, to address national tax competition. Specifically, Pillar 2 consists of three rules: income inclusion, undertaxed payments, subject to tax.

Income Inclusion Rule (IIR) primarily aim to prevent benefits transfer to the country of residence. According to the provisions, if the ETR applicable to the income of the foreign branch of a resident enterprise or a managed foreign enterprise is lower than the minimum tax rate, the resident is required to pay back tax on the income regardless of whether it remits money domestically or accounts for the distribution of profits.

The Undertaxed Payment Rule (UTPR) is specific to the country of origin. Applicable to cross-border payments, the ETR is lower than the minimum tax rate, and the remitting country should treat the money from the cross-border payer as a pre-tax deduction, or remittance tax collection can be rejected. The UTPR is considered a supplement to the IIR, and only if the country of residence renounces the IIR, does the country of origin exercise the right to tax, which has a priority right of application to the IIR.

The “two pillars” of the world’s lowest corporate tax rate of 15% are Income Inclusion Rule (IIR), the Undertaxed Payments Rule (UTPR), and the Subject to Tax Rule (STTR). These rules are designed to prevent profit shifting and base erosion and to reduce the loss of tax rights and interests of countries. Income Inclusion Rule (IIR) are primarily aimed at the country of residence and stipulate that the ETR of multinational groups shall not be lower than the minimum tax rate. The Undertaxed Payments Rule (UTPR) is mainly for withholding tax countries, and when overseas-related payments occur, when the ETR applicable to the overseas relevant payer is lower than the minimum tax rate, you can refuse to collect the pre-tax deduction or withholding tax of the withholding tax country on the domestic payer.

Residents’ tax rates often decrease at the beginning of the year and rise towards the end as pay accumulates. The comprehensive income tax rate determines non-resident people’s pay based on their monthly pay. There are seven tiers of tax rates, with 45% being the highest and 3% being the lowest, based on the taxable income of an individual’s monthly pay. There will be a five-tiered progressive tax system in place for company income. Any company doing business in China must pay the country’s corporate income tax, which imposes a flat rate of 25%. Several deductions and incentives are implemented to help and encourage enterprises in certain areas, and foreign companies can take advantage of the advantages.

As a complement to the UTPR, it aims to protect the tax base of the source-collecting country with a low collection capacity. In cases where the nominal tax rate in a particular country of origin is lower than the minimum tax rate under the STTR rules, the tax at source or tax at source may be levied at the lowest rate. Now, the minimum tax rate for STTR rules is 9%.

2 Background of the Proposal of the Global Minimum Corporate Tax Scheme

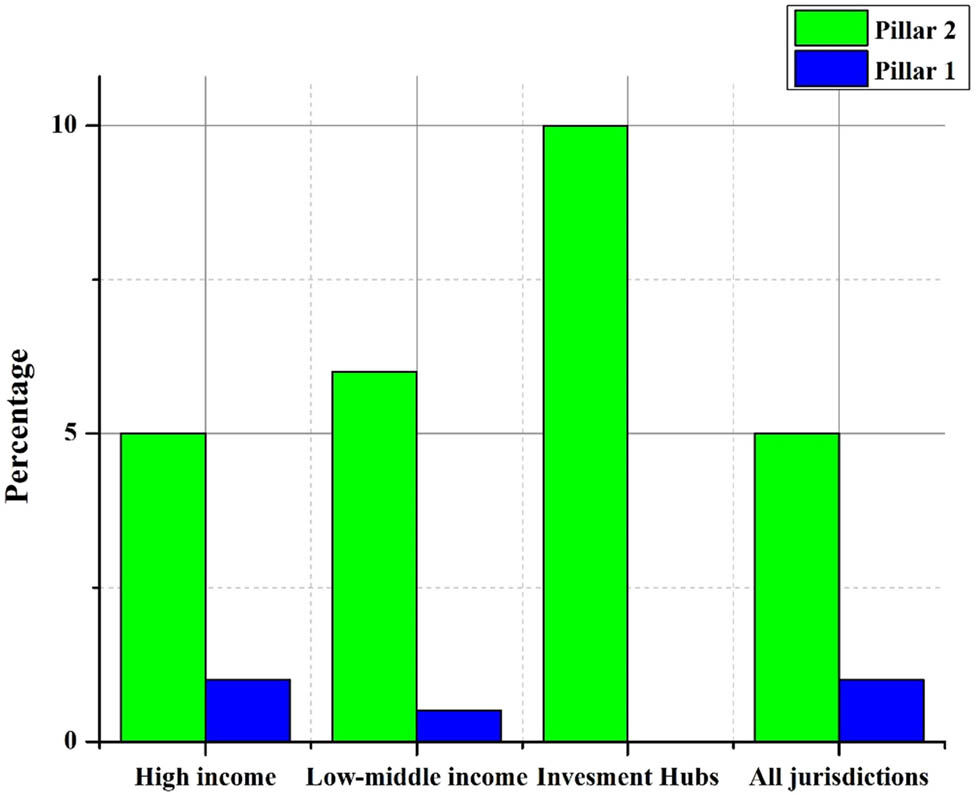

Figure 1 shows the differences and loopholes in the tax systems of different countries, which have led to different companies using the rules to plan for tax purposes; there are currently about 100 tax havens in the world, and the OECD was commissioned by the G20 to publish the BEPS action plan in 2013 and proposed “two pillars” in 2019. Pillar 2 proposes a global approach to preventing base erosion (GloBE). Therefore, the world minimum tax is not a new issue, but it has been included in the BEPS in response to the bottoming out of the tax competition.

Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 tax scheme.

Prettl & von Hagen (2023) introduced that the bottom-out competition in taxation is a concrete manifestation of the conflict of interests in the globalization of the world economy. To gain foreign investment, countries have lowered their corporate tax rates, and in a study of 223 jurisdictions, the global average corporate tax rate fell by 41%, from 40.11% in 1980 to 23.85% in 2020. The GDP-weighted average tax rate fell to 25.85% in 2020, a decrease of 44%. This bottom-buying competition continues, with countries announcing tax cuts, such as reducing France’s corporate tax rate to 25% by 2022. The result is a level playing field.

Harpaz (2021) explained globe refers to the background of the global intangible asset tax decline 2017. It is like the unilateral introduction of the GMT by the United States. Due to the long-standing problem of U.S. companies keeping their profits overseas, the TCJA introduced a new GILTI system. The rule sets a minimum % profit margin of 10% for U.S. companies operating and investing abroad, and taxes must be levied on the United States to prevent cross-border tax avoidance. This approach is adopted in the OECD proposal to address tax encroachment and profit transfers.

3 An Overview of Domestic and International Research on the World’s Minimum Tax

The minimum tax rate is not new and is practised in many countries. In the past, sales tax in Germany, excise tax on gasoline in the European Union, and personal income tax in the United States all had a minimum tax (AMT) system. The OECD’s minimum tax scheme is based on this idea. Regarding the method of minimum tax, it argues that international tax competition reduces the redistributive power of tax revenues of various countries and argues that a minimum tax should be accepted on a global scale. Johannesen (2022) believes these rules can help safeguard the tax interests of various countries, reduce corporate tax avoidance, help the organizational design of multinational companies, and introduce the details of the four rules. Stewart (2023) argues that this can crack down on tax avoidance and reduce the pressure of tax competition, which is an effective supplement to the BEPS program and draws on the rules of the United States. Dourado (2023) pointed out that this plan can only alleviate the tax challenges brought about by the digital economy but cannot fundamentally solve the problem, and the setting of tax rates should consider the global collection management and the actual situation of each country. Regarding the proposal of a minimum tax, Johannesen (2022) suggested that the tax situation of various countries should be coordinated, and the tax rate should be set to meet the needs of most countries, considering not only the corporate income tax rate but also the comprehensive tax burden. Becker and Englisch (2021) believe that it is necessary to adapt measures to local conditions, consider the tax collection capacity of various countries, do a good job in the application procedures and calculation of rules, and consider the impact on the world economy.

The losses suffered by China in the tax avoidance of international intangible assets should not be ignored. A study found that in 2017 alone, 17,999 patents were leaked from China, with a net outflow of 11,390 patents. Most of these patents went to regulated foreign companies in tax havens such as the Cayman Islands, Switzerland, and Hong Kong. The Cayman Islands had the largest outflow from China, with 1,872 outflowing from China alone in 2017. China’s current intangible asset transfers are mainly for tax avoidance, evading Chinese mainland tax jurisdiction through transfer pricing and other means. The world’s minimum tax reform package will bring more than $5 billion in tax revenue, so as one of the solutions to the legacy BEPS, Malaysia, is expected to eliminate the continuous erosion of the tax base.

In addition, the G7 has set a GMT rate of 15%, based on the ETR. However, the corporate tax rate in developing countries is generally higher than 15%, and due to the low level of development of the digital economy, the tax that can be levied in the country is very limited. As digital economy powerhouses, Aslam & Coelho (2021) determined introducing a GMT in the United States and Europe has expanded their international tax jurisdiction and greatly impacted the development of the digital economy in developing countries.

In October 2019, the OECD issued a policy statement on the “two pillars” and “Pillar 2”), which proposed a reform plan for the world’s minimum tax rate, which has aroused strong responses from various countries. In December 2021, the European Commission issued the “Implementation Guidance for the Global Minimum Corporate Tax” to align with implementing the world’s minimum tax. Now, 138 of the 142 BEPS member countries support the minimum tax.

EsmaeilDarjani et al. (2023) discussed that taxpayer judgements based on classical economic models inform the strongest tax policy (Zhang et al., 2023). Analyses reveal that traditional decision-making models, which are essentially economic and lack socio-psychological underpinnings, cannot quantify changes and stakeholders’ functions. In research, behavioural economics and anticipated desirability were compared to compute tax offences using mathematical modelling and scenario-creating tools. With mathematical modelling and a questionnaire to compute tax offences, the analysis research examined behavioural economics and anticipated desirability. The results support selecting the theory of perspective over the theory of anticipated utility, and adding tax ethics reduces the tax penalty in either theory.

Imeni et al. (2021) detailed that the enterprises listed in the Tehran Stock Exchange can possess their management abilities and earnings categorization shifting examined in the research (Imeni et al., 2021). The detrimental impact of earnings management on a company’s future performance may be reduced by competent management. In addition, the agency cost is favourably impacted by managerial skills because of the decrease in earnings management. This study’s findings suggest a favourable correlation between management skills and the capacity to adjust earnings classifications. The paper’s findings help bridge the gap between theory and practice by providing empirical evidence of the relationships between management skills, earnings categorization shifting, and agency cost in a developing nation like Iran.

Devereux et al. (2023) examined the GMT suggested under Pillar 2, which is the focus of the different research, providing empirical data with the programmed (Devereux et al., 2023). As the initial process determining how many nations and groups of nations can be considered a critical mass for the GMT’s effective implementation, if the threshold is reached, subsequent jurisdictions throughout the globe can be compelled to pursue a lawsuit. Then, the situation provides useful information for GMT revenue by assessing the generosity of substance-based income exclusion.

Sinha and Edalatpanah (2023) determined the empirical research employs a network DEA data technique to assess and clarify the fiscal performance of Indian governments (Sinha & Edalatpanah, 2023). Previous research has analysed fiscal and developmental success in India at the subnational level; however, the current report breaks unique ground by evaluating performance from the state level. Before assessing the states’ development expenditure and overall financial performance, people compare nations according to their tax collections. In their peers’ hands, efficiency and the percentage of outstanding liabilities negatively correlate. The outcomes indicate the need for fiscal restraint on the government’s responsibility if people want to prevent the debt crisis from occurring again.

Hebous and Keen (2023) introduced the Global tax arrangements, which are about to undergo a sea shift due to the impending adoption of an international agreement on a minimum effective corporation tax rate. Yet, there has been much debate about what that minimum should be. The legislative goal of a minimum tax is to alter the tax competition game, and this study delves into the strategic reactions to this innovation to evaluate its design and welfare effect. If we compare the coordinated equilibrium to the uncoordinated one, we can see that there is much room for Pareto-improving minima, meaning that both high and low-tax nations stand to gain.

Zhang et al. (2023) illustrated when people began to understand that business decisions have an impact (EsmaeilDarjani et al., 2023). Industries can demonstrate that they care about society by sharing more than just financial data and helping stakeholders make better decisions. A multivariate regression approach based on panel data analysis was used to test the study hypotheses. The results show that operational efficiency is a moderator function that is positively and significantly associated with corporate social responsibility for profit persistence, whereas financing cost is irrelevant. Developing nations are the primary focus of previous studies in the field. Examining sustainability from a global viewpoint is essential, and the research adds to the growing body of evidence supporting that claim.

Fu et al. (2022) developed a global digital tax and countermeasures for the Chinese digital tax. The expansion of the digital economy has raised new issues for international taxes. The implementation of digital tax-collecting policies is supported or opposed by various countries and key international organizations, depending on their stances. Reviewing the current state of digital tax collection supervision policies in key countries and international organizations, this article seeks to analyse the impact of digital tax on China’s digital economy and provide policy recommendations for the development of the tax.

Ma et al. (2023) suggested an analytical framework based on the New-Market Public Finance for Taxation Reform Scheme for the Digital Economy and China’s Response. The first is to shape an idea of a platform marketplace, to innovate the rationale of both the platform entities of the new digital financial system market and the significance of the tax nexus to such entities, and the marketplace mechanism of the brand new virtual economic system platform in addition to its traits of tax legal guidelines and guidelines; the second one is to shape a concept of comparable governments, to explore the rectification of the effective function of governments and the proof of the legitimacy of taxation rights, the recovery of the panorama of the comparability of cross-border transactions, and the calculation of comparable authorities tax bases; the 0.33 is to specify the idea of income control rights, one at a time to examine the tax gain video games between multinational corporations and governments inside the OECD reform plan and the competitions of business patterns between countries and the economic agencies within the virtual financial system.

Implementing the GMT reform plan will impact enterprises in China’s science and technology service industry. First, the GMT stipulates that multinational companies can only tax the profits of subsidiaries in various countries that exceed a certain amount, so the profits of Chinese enterprises abroad may also be taxed, which will affect their profitability in the world. Second, the GMT scheme may affect the overseas investment and M&A activities of Chinese enterprises, leading to tax avoidance by multinational companies. In addition, implementing the GMT scheme may affect the financing activities of Chinese enterprises, and enterprises should provide more information.

4 The Impact of the World Minimum Tax Reform on China’s Pros and Cons Analysis

4.1 Positive Impact

4.1.1 Enhance its Influence on International Tax Administration

Since the “Pillar 2” plan was proposed, resistance from many sides has always been encountered. Since 2019, the OECD has received much feedback from multinational corporations, industry groups, academia, civil society, research institutions, and individuals. For example, the first draft of the two pillars proposed by the OECD in 2019 received more than 500 comments. Among them, well-known Chinese enterprises, university scholars, social experts, and other forces actively participated in the event and offered good opinions and suggestions on behalf of China. In January 2022, Pascal, Director of the OECD Tax Policy Management Center, praised the important role played by China’s tax authorities and various forces in international tax administration in a video conference with Wang Jun, Director General of the State Administration of Taxation. It can be seen that China has become an important member of international tax governance, and its influence and voice in this field are increasing.

4.1.2 Effectively Solve the Problem of Erosion of China’s Tax Base

BEPS is a major problem in the international tax sector. As the world’s second-largest economy, China is also facing the problem of tax loss caused by the erosion of the tax base. The main reasons for the erosion of China’s tax base are as follows: (1) multinational enterprises take advantage of loopholes in international tax rules to avoid taxes, (2) the domestic tax system is imperfect and lacks effective anti-tax avoidance measures, and (3) the intensification of international tax competition has led to the implementation of low tax policies in some countries, thus attracting multinational enterprises to transfer profits to these countries. The reform of the world minimum tax positively solves the erosion problem of China’s tax base. Avi-Yonah & Kim (2022) discussed the implementation of the minimum tax system can restrict the tax avoidance behaviour of multinational enterprises and improve the transparency of their tax burden; the minimum tax reform can reduce international tax competition and help safeguard the country’s tax rights and interests; and the minimum tax reform can promote the fairness and rationality of China’s tax system and enhance China’s influence in the international tax arena.

4.2 Negative Impacts

4.2.1 Increased Tax Costs for International Investment Activities

International investment activities are an important channel for promoting the economic prosperity of countries under global economic integration. In the early days of reform and opening up, China introduced advanced production technology by absorbing foreign capital. Today, foreign investment has become an indispensable part of our economy. Enterprises go out to solve the surplus funds and idle capacity effectively. However, de Wilde (2021) argued implementing Pillar 2 will increase the tax burden on international investment activities and reduce the incentive for capital flows.

Figure 2 shows that fully implementing the GMT reform may greatly reduce China’s space and advantages in attracting overseas investment. Currently, China provides various preferential treatments, such as tax rate reductions and exemptions for multinational companies operating in China. The preferential policies have had an important impact on China’s attraction to foreign investment. However, implementing the Pillar 2 program has almost eliminated the charm of our country in terms of taxation. For example, high-tech enterprises enjoy a 15% discount. If the accounting profit is replaced with taxable profit, the ETR of the enterprise is expected to be less than 15%. This way, multinational enterprises (MNEs) are entitled to back taxes in their home countries. Even if the home country waives the exercise of IIR, China will implement the UTPR under the provisions of Pillar 2, which will also increase the tax burden of foreign-funded enterprises in China. Judging from China’s various preferential tax policies for foreign-funded enterprises, it is not uncommon for foreign investment to increase its tax burden in China.

Impact of tax on economic growth.

The STTR also increases the tax burden on foreign companies in China. Under the STTR, developing countries can levy a withholding tax of 7.5–9% on cross-border interest and royalties paid by multinational corporations. However, looking at China’s foreign tax treaties, it can be found that the withholding tax rate for many countries is lower than this range. In addition, foreign investors who invest in China’s encouraged projects can defer their tax obligations and not pay individual income tax. Therefore, some of China’s foreign-funded enterprises also have to bear the STTR tax obligations levied by China for their external payments, and the investment cost has risen further.

On the other hand, Chen (2024) concluded the entry of Chinese companies will also become sluggish. In recent years, China’s outbound investment momentum has increased significantly. According to the tax law, Chinese enterprises can use the set-off method to offset the overseas tax burden (except for the Hainan Free Trade Port). Chinese companies are liable for at least 25% of their global revenue. However, to encourage foreign investment, China has also signed preferential tax clauses with some countries, and with local preferential tax policies, it has significantly reduced the tax burden of foreign investment funds. For example, the tax holiday for funds invested by China in Vietnam’s coastal and port economic zones is 4 years and 5% for 9 years. Such funds are not subject to additional tax when remitted to the country. If the Pillar 2 scheme is fully implemented, the tax burden below 15% will be subject to retroactive taxation, and the tax cost will increase significantly. The willingness to invest abroad is expected to decline significantly.

4.2.2 Declining Autonomy of Economic Strategy

Riccardi (2021) suggested that the World Minimum Tax case will be presented as an international convention, with consideration given to future changes to domestic law. This means that in addition to the effectiveness of domestic tax laws, the infringement of tax sovereignty also weakens the implementation of China’s independent economic strategy. The most obvious example of this impact is the integration of China’s Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. For a long time, Hong Kong and Macau have been favoured by international funds for their territorial tax systems and low corporate income tax rates and have become important bases connecting Chinese mainland and foreign countries. Promoting the integration of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area is conducive to further strengthening the financial integration between the mainland, Hong Kong, and Macao and building a new pattern of opening up to the outside world. First, Hong Kong and Macao have long implemented a territorial tax system, which exempts foreign income obtained by local enterprises. Therefore, dividends derived from investment in the Mainland by Hong Kong and Macao, investment by overseas capital in the Mainland through Hong Kong and Macao, and income from overseas investment by Mainland capital through overseas investment in Hong Kong and Macao are not subject to Hong Kong tax liability. Second, Hong Kong and Macau have lower corporate income tax rates of 16.5 and 12%, respectively. Moreover, as both sides have signed bilateral agreements with the mainland, the increase in interest and royalty rates has been kept very low. It can be seen that the natural tax advantages of Hong Kong and Macao can effectively support the integration of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and are important policies for the joint development of the three places and the strengthening of domestic and foreign capital exchanges.

However, after implementing the Pillar 2 plan, the tax advantage will no longer exist. First, in Hong Kong and Macao, the preferential tax effect brought by the territorial tax system will be greatly reduced. The ETR must be calculated for the global income and the tax burden of the host country of Hong Kong and Macau enterprises. This figure is expected to be well below 15%. Therefore, the home country of the multinational corporation is entitled to levy a supplementary tax under the IIR. In addition, the STTR levies advance income tax on interest, royalties, and other payments at a rate of 7.5–9%, and the tax burden on the transfer of funds will also increase significantly. This will not only significantly weaken the confidence of the mainland in in-depth communication with Hong Kong and Macao and affect Hong Kong’s status as an international financial centre but also drag down the integration process of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, and drag down China’s regional construction and international investment, which will not be beneficial to itself.

Kurian (2022) introduced the economic strategy of the hinterland will also be affected. In recent years, China has explored reforming the international tax system in inland areas, and the construction of the Hainan Free Trade Port has been one of the pioneering reform pilots. One of the objectives of establishing the Hainan Free Trade Port is to promote the free flow of production factors such as capital and technology, and for the first time, enterprises in specific industries established in Hainan will be exempted from taxation. However, the capital exemption regime and Pillar 2 scheme are inherently contradictory. According to the equity participation exemption system of the Hainan Free Trade Port, when making direct investments in countries or regions with a statutory corporate income tax rate of not less than 5%, there is no need to bear separate tax liability on overseas income. Under the IIR, a subsidy tax is levied on businesses with an ETR of 15% or less. In other words, when Hainan enterprises invest in countries or regions with a statutory corporate income tax rate of more than 5%, the tax exemption provided by the equity participation exemption system will be fully or partially deducted by the IIR. This shows that China’s implementation of the tax exemption policy in Hainan cannot achieve the purpose of equity participation, tax incentives cannot be substantively implemented, and the international tax reform of the Hainan Free Trade Port will be seriously hindered.

5 Suggestions on China’s Response to the World’s Minimum Tax Reform

Tang (2024) concluded China has played an important role in discussing the two-pillar tax reform plan in the past. The legislative template for the two-pillar program has been developed, but countries are still consulting and discussing the key elements. In the future, China will continue to seize the opportunity of the reform of international tax governance, fully participate in discussions, express China’s views, enhance China’s influence in the field of international tax governance, and at the same time conform to the universal, reasonable, and multilateral interests, to contribute to the formulation of international tax plans in line with China’s development direction. This article proposes the following changes (Figure 3).

Pillar 2 tax form.

If the total ETR of all international earnings falls below the minimum tax threshold

To follow the preceding section’s formulation in equation (1), the weighted average tax rate, which takes into consideration shifting earnings and the effects of global blending, is now provided by

It should be noted that any deductions and allowances associated with an investment may only be provided in the jurisdiction where the investment occurs,

The cost of capital, assuming the existence of a minimal tax associated with global blending, is expressed as

Regarding Pillar 1,

If the ETR in a particular jurisdiction is lower than the minimum tax threshold,

The following is the topping-up of the average weighted low-tax rates

In the case of a minimal tax with jurisdictional blending, the average weighted tax rate that takes shifting profits into consideration is

Capital expenditures associated with Pillar 2 and the merging of jurisdictions are given a value of zero.

5.1 Provide More Flexible Policy Space

As the most daring reform plan in international tax administration in recent years, the two-pillar plan should consider each country’s national conditions and the interests of both developed and developing countries. The previous program was based on the position of developed countries. On July 5, 2021, the African Tax Administration Forum announced that it would continue to propose a higher minimum tax rate to the OECD with the African Union and hoped to reach an agreement on a comprehensive framework and a tax rate of at least 20%. As a solution to the remaining BEPS problem, the world minimum tax reform plan is based on the concept of a community with a shared future for humanity and considers developing countries’ interests. As stated by the African Forum on Tax Administration, the statutory corporate tax rate in African countries is between 25 and 35%, and setting the GMT rate at 15% is not only detrimental to the interests of countries with corporate tax as the main fiscal revenue but also leads to corporate surplus and promotes the transfer of profits to the Czech Republic. China’s statutory corporate income tax rate is 25%, and the world’s minimum tax rate of 15% is too low, which may inhibit the incentive for Chinese capital to transfer overseas. To promote the participation of countries (regions) and consider the needs of developing countries, Zhang & Song (2022) proposed to set a flexible range of 20% for the minimum tax rate from 15 to 15, which will be decided according to the specific situation of each country.

5.1.1 Replace the ETR with the Nominal Tax Rate

It would be more appropriate to continue with the nominal tax rate. In China’s tax avoidance law, the definition of tax avoidance is generally determined based on the nominal tax rate of the country or region where the investment is being made. From the current situation, the ETR seems to be more reflective of the actual tax burden of enterprises, but the adoption of the ETR will lead to the convergence of the two tax rates in the long run and will also have an impact on the fairness of accounting and the policy of taxation. Compared with the ETR, the use of a nominal tax rate can not only greatly reduce the collection cost of the tax authorities but also help the Chinese government to continue to introduce preferential tax policies for encouraged industries, guide the flow of foreign capital to industries that meet the needs of China’s development, and also help China’s economic development structure. China should propose that the nominal tax rate replace the real tax rate and include it in the world minimum tax rate reform. China significantly impacted neighbouring civilizations’ political structures, societal norms, and social roles. Most notably, the Chinese language and writing system, confucianism, and religion contributed substantially.

5.1.2 Expand the Scope of Substantive Exclusions

Eliminating double taxation and promoting international investment is the beginning of international tax rules. As a policy expected to become the latest international tax governance plan, the minimum tax regulation is a tax avoidance measure that should not increase enterprises’ tax burden and affect normal international investment activities. The latest plan restricts the actual operation of enterprises. In other words, only the impact of tangible assets and remuneration is considered, and other factors closely related to actual business activities, such as R&D expenses, are not considered. The exclusion rate of 5% is too low for the actual business activities of enterprises. China should continue to propose that the scope of the actual exclusion be expanded, so that the actual economic profits of transnational corporations can be reflected as much as possible. Multinational corporations often use tax planning tactics like BEPS to evade taxes by exploiting loopholes and inconsistencies in the tax code. Due to their disproportionate dependence on corporate income taxes, developing nations bear the brunt of BEPS.

5.1.3 Add an Exception to Exempt Capital Participation

Aslam & Coelho (2021) explained since the last century, the capital injection exemption system has been supported by several countries, such as the United States, the Netherlands, and Singapore. Chand et al. (2021) found that its mechanism design has effectively promoted the cross-border flow of capital, technology, and other production factors between countries and has played an important role in enhancing the open economy. On the other hand, countries have set strict restrictive standards for capital exemption systems, and multinational companies do not have to worry about tax avoidance due to capital exemptions. For China, implementing the shareholding exemption system in the Hainan Free Trade Port is undoubtedly a major tax reform, which is of great significance to promoting China’s overseas investment activities. To this end, China proposes to join forces with other countries to exclude the exemption from capital participation from the world’s minimum tax case.

5.2 Introduce Relevant Policies to Safeguard China’s Interests

Global minimalist tax is effective for the profit transfer of multinational companies for tax avoidance, but so far, its regulation is still very rigid and complex, and there is great uncertainty and irrationality. For example, the core rule IRR confers the main taxing power on the resident country, which seriously negatively impacts the rational behaviour of developing countries in introducing appropriate tax incentives to attract foreign investment. Although STTR and UTPR give market countries the right to tax, it is difficult to determine who is taxing and what country is taxing. At present, the mechanized and mandatory minimum tax regulations will cause problems in all aspects, so China must introduce corresponding policies to safeguard the reasonable interests of the country.

5.2.1 Take the Lead in Introducing the World’s Lowest Tax in China

The tax collection under the existing framework involves many countries. The complex regulations on the taxation entities and the attribution of tax rights make it very easy for the tax authorities of various countries to make mistakes and omissions in the case of insufficient coordination between them. There is a possibility that China’s tax interests will be infringed. To deal with this problem, the introduction of the world’s lowest tax rate in the country is an option. Countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia have published Pillar 2 cases to discuss domestic minimum taxation policies to protect the right to tax the Company’s interests. The Gilty tax system, introduced in 2017 by the United States, the main promoter of the Pillar 2 initiative, already imposes the world’s lowest tax on the profits of domestic companies. China can also learn from this practice and levy the world’s lowest tax before its own country, which can be adjusted according to its own needs within the framework of the GloBE system. Through the unilateral collection of the world’s minimum tax, China has taken the lead in independently completing the tax collection work, effectively protecting the right to tax the profits of domestic enterprises and safeguarding the interests of domestic taxation.

5.2.2 Clarify the Priority of STTR over UTPR

Although China is still providing reasonable tax incentives for cross-border investment in line with China’s national conditions, the promotion of IRR will enable these incentives to be objectively converted into tax revenues for Western capital-exporting countries. This violates the purpose of China’s policy and infringes on China’s tax rights and interests. In this regard, it is advisable to determine the priority of STTRs over UTPR. Although the UTPR also gives market countries the right to levy taxes, it ranks second only to the IRR, and the capital-exporting countries have every incentive to introduce IRRs to make up taxes. At this time, if China gives priority to the implementation of STTR, foreign-funded enterprises can get tax exemptions when paying interest, royalties, and other fees abroad, effectively avoiding the unfavourable situation of converting their tax incentives into tax revenues of other countries.

5.2.3 Establish an Exclusion Mechanism in Consultation with Other Countries

Currently, countries along the Belt and Road Initiative offer a variety of tax incentives for Chinese investment. These incentives have nothing to do with harmful tax competition and are a legitimate regime in the interests of both sides, but the two-pillar approach makes cooperation less effective. In this regard, exclusion mechanisms could be established in consultation with other countries. The possibility for low-income nations to lose money, challenges with establishing a globally acceptable minimum rate, difficulties in enforcing the rule owing to variations in legal systems, and a lack of national fiscal sovereignty are several issues that can be raised in favour. The objective of the second package is to combat harmful international tax competition and should not affect the reasonable tax policies agreed between the two countries. Based on this position, China will actively negotiate with relevant countries to reach a consensus on whether to levy retroactive taxes and advance taxes on international investment between them and, based on mutual commitments not to implement the Pillar 2 plan, a unified and continued deepening of cooperation can be reached. This would combat harmful BEPS issues without compromising beneficial international tax cooperation.

5.3 Prepare for the Implementation of the Two-Column Plan as Soon as Possible

With the publication of the legislative template, the form of implementing the Pillar 2 case through domestic law amendments and bilateral tax treaties has gradually become clear, as shown in Figure 4. How to better integrate the Pillar II program with national law is now a top concern for States. For China, the world minimum tax reform is an opportunity to sort out the relevant domestic tax regulations. China’s tax authorities should focus on successfully implementing the Pillar 2 plan and consider sorting out and updating the previous tax regulations to adapt to the requirements of the new economic situation as soon as possible. The ecology has suffered due to China’s fast urbanization and industrialization. Important problems affecting public health and the economy include soil deterioration, water contamination, and air pollution. Many industries’ faith in government has been eroded due to hazy regulations. Transnational industries face more uncertainty due to the government’s effort for self-sufficiency.

Effective average tax rates.

5.3.1 Establish a Capital-Related Tax System

Parada (2024) argued the solution to the tax problem of cross-border capital flows in China should not rely on implementing the GMT scheme. Taking this international tax governance reform as an opportunity, Li (2023) concluded that is important to fully understand the tax regulatory needs for cross-border investment in the current international tax environment and to improve the capital-related tax system. Currently, China does not have an overseas income tax deferral clause, but China’s capital export tax system also needs tax avoidance. The scale and coverage of China’s outward investment are growing rapidly, and the growth rate is still growing against the trend despite the decline in global outward direct investment and the growth rate is being dulled after 2016 due to the impact of investment and trade protection. At this stage, China’s total capital exports are declining yearly, and the growth rate of China’s foreign investment stock has slowed down and created a large gap between the United States and other Western capital-exporting countries. China’s economy also needs to be driven by capital exports. International tax competition will continue for a long time, and attention should be paid to improving the competitiveness of China’s international tax system in the process of China’s development as a capital-exporting country. The strategy entails constructing a collection of financial measurements by analysing a company’s financial statements and their associated statistics. Evaluation of performance, evaluation of financial instruments, and prediction are all areas that may benefit from quantitative analysis. Several main data measurement forms are included: regression analysis and linear development.

5.3.1.1 Relevance and Reliability and Availability of Tax Reform in China

Comprehensive reforms to the tax system began, and trials with various new levies have continued. Government revenue and the central government’s capacity to lead businesses and local governments without limiting initiative are two significant aspects of China’s tax reform that can be overlooked. After several reforms that have improved China’s economic and fiscal situation, the tax-sharing system structure between the central and provincial governments is still in place today. China’s massive tax reform aimed to create a tax structure that could accommodate the country’s emerging socialist market economy. Securing the revenue base and adapting to international standards are two main issues China’s tax system faces now.

5.3.2 Actively Adjust the Structure of Tax Incentives

Hanappi & Cabral (2022) pointed out that the existing GMT reform plan restricts each country’s tax preferential policies. The effectiveness of the traditional tax preferential policies is greatly weakened. Less than 15% of the actual tax burden will be recognized as tax avoidance, and the tax needs to be paid. In this case, Guo et al. (2022) suggested that China must actively adjust the structure of tax incentives to make them perfectly compatible with the two-pillar scheme. To achieve this goal, China must first sort out the cumbersome preferential policies and simplify the tax system. In China, only the Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation have issued preferential policies, which have accumulated too many interrelated policy provisions. The government should organize a reasonable organizational structure according to a certain logic and apply the new preferential tax policies at a standard not lower than the minimum tax rate so that enterprises can fully enjoy the reduction of the tax burden brought about by the policy. Second, China could consider transferring corporate income tax benefits to other tax categories. The 15% preferential tax rate enjoyed by high-tech enterprises is not only a symbol of support for advanced technology and industry, but also helps maintain China’s favorable position in global tax competition. Under this framework, by increasing VAT deductions for high-tech enterprises and other measures, the corporate tax burden can be further reduced and innovation and development can be promoted. At the same time, exploring preferential mechanisms for other taxes, such as tax reductions and exemptions for specific industries or fields, will help provide more precise tax support for domestic enterprises and enhance their international competitiveness. In addition, the government can support enterprises’ business activities and reduce the impact of tax incentives. For example, the government bears part of the R&D costs of high-tech enterprises, and the government guides them to expand sales when they engage in specific incentive industries. Finally, tax incentives can be considered for fiscal subsidies. The fiscal incentives in China include financial subsidies, financial interest discounts, and financial allocations. Among them, fiscal subsidies and fiscal allocations are tax-exempt income in tax treatment, and fiscal subsidies must also pay corporate income tax when they do not meet the conditions of the intended use, so fiscal subsidies are not affected by the Pillar 2 scheme. China’s tax authorities can learn from this practice by enriching the forms of fiscal subsidies, increasing the intensity of fiscal subsidies, moving the preferential tax policies greatly affected by the Pillar 2 plan to the preferential fiscal policies, and formulating specific industries to reduce the tax pressure.

6 Conclusion

To protect China’s tax rights and interests, the government will proactively work to establish international standards for digital taxes. The digital tax collecting system directly impacts the growth of the worldwide digital economy and tax equity, which are linked to national sovereignty and tax interests. Due to factors like the complexity of digital taxes, the legitimacy of tax interests, and the unequal development of digital economies around the globe, reaching an agreement on a worldwide digital tax system is challenging. International groups such as the G20, OECD, and the EU are moving quickly to build systems of digital tax rules worldwide. China has to improve its communication and collaboration with different international organizations, raise its profile in international tax affairs, and protect its tax rights and interests if it wants to encourage the growth of its digital economy while protecting its tax interests. Achieving sustainable development objectives is greatly influenced by tax policy. Tax policies and small and micro firms may be seen as important drivers of economic development, which is one of the goals of SDG. The long-term health of an economy is bolstered by tax laws that help successful companies recruit investment. Thus, it is essential to track the development of micro and small firms, especially after any national tax changes or reforms. Proposals for Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 would change the laws of international taxes, which would affect global investment by changing the incentives that governments and MNEs confront. The process is important to establish the immediate impact of the recommendations on investment costs using the strategy provided in the report. Results from the study of ETRs at the MNE group level indicate that Pillars 1 and 2 had a little impact on EATRs and EMTRs at the MNE group level. Pillar 1 and 2 are expected to have a minimal influence on the EATRs, with a worldwide GDP-weighted average shift of 0.4% points. Following these findings, the tax rate differentials would be reduced due to the recommendations, with the benefits of Pillar 2 complementing those of Pillar 1. From the numerical outcomes, the minimum tax with jurisdictional blending was set at 12.5% under Pillar 2; the disparity between the sample’s top and lowest EATRs would decrease by 2.8% points. Reducing the dispersion of ETRs across jurisdictions would make non-tax factors, such as workforce education, skill supply, accessibility of infrastructure, and strength of legal and regulatory systems, more relevant in deciding the size and location of investments and potentially reducing the transfer of profits motivations. Reduced tax rates increase the after-tax return for working, saving, and investing, increasing the economy’s size. Substitution effects cause people to strive harder, save more, and invest more after taxes. Due to the inherent complexity of the measures, persistent tax evaders can continue testing the limits, resulting in the reforms’ elimination of tax problems.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses heartfelt gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback and meticulous review of the manuscript. The support and mentorship from the School of Economics and Management at Ningxia University have been instrumental in the completion of this research. Special thanks are extended to the Longyan Municipal Tax Service in Fujian Province, China, for their guidance during the research, which was crucial in shaping the focus of this study on the global minimum tax rate. The author acknowledges the significant contributions of all parties involved.

-

Funding information: The author states no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results and manuscript preparation. YL: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, visualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, software, validation, supervision, writing – review and editing, and project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

References

Aslam, A., & Coelho, M. D. (2021). A Firm Lower Bound: Characteristics and Impact of Corporate Minimum Taxation [IMF Working Papers, No. 161]. Journal of International Money and Finance. doi: 10.5089/9781513561073.001.Search in Google Scholar

Avi-Yonah, R., & Kim, Y. R. (2022). Tax harmony: The promise and pitfalls of the global minimum tax. Mich. J. Int’l L., 43, 505.10.36642/mjil.43.3.taxSearch in Google Scholar

Becker, J., & Englisch, J. (2021). Implementing an international effective minimum tax in the EU. Available at SSRN 3892160.10.2139/ssrn.3892160Search in Google Scholar

Beer, S., De Mooij, R., & Liu, L. (2020). International corporate tax avoidance: A review of the channels, magnitudes, and blind spots. Journal of Economic Surveys, 34(3), 660–688.10.1111/joes.12305Search in Google Scholar

Chand, V., Turina, A., & Romanovska, K. (2021). Tax treaty obstacles in implementing the pillar two global minimum tax rules and a possible solution for eliminating the various challenges. Available at SSRN 3967198.10.2139/ssrn.3967198Search in Google Scholar

Chen, B. (2024). Global minimum tax reform: Substance, impact, and response strategies. Taxation and Economic Research, 2, 28–38. doi: 10.16340/j.cnki.ssjjyj.2024.02.00.Search in Google Scholar

Cheng, X., & Zhou, P. (2022, June). The impact and countermeasures of the “two pillar” scheme for mobile digital enterprise taxation. In International conference on human-computer interaction (pp. 149–157). Springer Nature Switzerland.10.1007/978-3-031-18158-0_10Search in Google Scholar

Devereux, M. P., Paraknewitz, J., & Simmler, M. (2023). Empirical evidence on the global minimum tax: What is a critical mass and how large is the substance‐based income exclusion? Fiscal Studies, 44(1), 9–21.10.1111/1475-5890.12317Search in Google Scholar

de Wilde, M. F. (2021). Is there a leak in the OECD’s global minimum tax proposals (GLOBE, pillar two)? Available at SSRN 3792531.10.2139/ssrn.3792531Search in Google Scholar

Dourado, A. P. (2023). Pillar two and the principles of ability-to-pay, legality, and symmetry. Intertax, 51(6/7), 448–450.10.54648/TAXI2023049Search in Google Scholar

EsmaeilDarjani, N., Assadzadeh, A., & BarghiOskoei, M. M. (2023). Investigating behavioral economics in tax evasion decision making phenomenon: A tax crime scenario approach. Journal of Decisions and Operations Research, 8(3), 654–670.Search in Google Scholar

Fu, S., Yuan, J., & Chen, Z. (2022). Research on the development of global digital tax and countermeasures of Chinese digital tax. In SHS web of conferences (Vol. 145, p. 01007). EDP Sciences.10.1051/shsconf/202214501007Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Y., Zou, T., & Shan, Z. (2022). Taxation strategies for the governance of digital business model—An example of China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1013228.10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1013228Search in Google Scholar

Hanappi, T., & Cabral, A. (2022). The impact of the international tax reforms under Pillar One and Pillar Two on MNE’s investment costs. International Tax and Public Finance, 29, 1–32. doi: 10.1007/s10797-022-09750-0.Search in Google Scholar

Harpaz, A. (2021). Taxation of the digital economy: Adapting a twentieth-century tax system to a twenty-first-century economy. Yale J. Int’l L., 46, 57.Search in Google Scholar

Hebous, S., & Keen, M. (2023). Pareto-improving minimum corporate taxation. Journal of Public Economics, 225, 104952.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104952Search in Google Scholar

Imeni, M., Fallah, M., & Edalatpanah, S. A. (2021). The effect of managerial ability on earnings classification shifting and agency cost of Iranian listed companies. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2021, 1–10.10.1155/2021/5565605Search in Google Scholar

Johannesen, N. (2022). The global minimum tax. Journal of Public Economics, 212, 104709.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2022.104709Search in Google Scholar

Kurian, A. (2022). The evolution of international tax regime and the OECD Two-Pillar solution: Analysis from a developing country perspective. Journal of Economic Issues, 1(1), 61–71.10.56388/ei220808Search in Google Scholar

Li, Z. (2023). The impact of pillar two rules on China’s tax incentive policies. North Carolina, America: Research Square.10.21203/rs.3.rs-2998454/v1Search in Google Scholar

Ma, H., Cao, M., & Bai, Y. (2023). The logic of the OECD international taxation reform scheme for digital economy and China’s response: An analytical framework based on the new-market public finance. Journal of Contemporary Finance and Economics, 2022(1), 29–39.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. (2021). Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation of the Economy – Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two): Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/782bac33-en.Search in Google Scholar

Parada, L. (2024). Global minimum taxation: A strategic approach for developing countries. Columbia Journal of Tax Law, 15(2), 202–207.10.52214/cjtl.v15i2.12714Search in Google Scholar

Prettl, A., & von Hagen, D. (2023). Multinational ownership patterns and anti-tax avoidance legislation. International Tax and Public Finance, 30(3), 565–634.10.1007/s10797-021-09719-5Search in Google Scholar

Riccardi, A. (2021). Implementing a (global?) minimum corporate income tax: An assessment of the so-called “Pillar Two” from the perspective of developing countries. Nordic Journal on Law and Society, 4(1), 1–38.10.36368/njolas.v4i01.188Search in Google Scholar

Sinha, R. P., & Edalatpanah, S. A. (2023). Efficiency and fiscal performance of Indian states: An empirical analysis using network DEA. Journal of Operational and Strategic Analytics, 1(1), 1–7.10.56578/josa010101Search in Google Scholar

Stewart, M. (2023). Tax states, jurisdiction and the multilateral reality. In International tax at the crossroads (pp. 115–140). Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781800889026.00011Search in Google Scholar

Tandon, S. (2022). The need for global minimum tax: Assessing pillar two reform. Intertax, 50(5), 396–413.10.54648/TAXI2022037Search in Google Scholar

Tang, S. (2024). Analysis of international disputes over digital services tax and exploration of China’s approach. Transactions on Economics, Business and Management Research, 4, 127–137.10.62051/saq4pd63Search in Google Scholar

Wang, L., Ma, P., Song, Y., & Zhang, M. (2023). How does environmental tax affect enterprises’ total factor productivity? Evidence from the reform of environmental fee-to-tax in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 413, 137441.10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137441Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Y., Imeni, M., & Edalatpanah, S. A. (2023). Environmental dimension of corporate social responsibility and earnings persistence: An exploration of the moderator roles of operating efficiency and financing cost. Sustainability, 15(20), 14814.10.3390/su152014814Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Y., & Song, Y. (2022). Tax rebates, technological innovation and sustainable development: Evidence from Chinese micro-level data. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 176, 121481.10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121481Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Political Turnover and Public Health Provision in Brazilian Municipalities

- Examining the Effects of Trade Liberalisation Using a Gravity Model Approach

- Operating Efficiency in the Capital-Intensive Semiconductor Industry: A Nonparametric Frontier Approach

- Does Health Insurance Boost Subjective Well-being? Examining the Link in China through a National Survey

- An Intelligent Approach for Predicting Stock Market Movements in Emerging Markets Using Optimized Technical Indicators and Neural Networks

- Analysis of the Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion in Promoting Inclusive Growth: Mechanism and Statistical Verification

- Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size under Turnover Tax: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on SMEs

- Re-investigating the Impact of Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development, Institutional Quality, and Globalization on Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries

- A Compliance Return Method to Evaluate Different Approaches to Implementing Regulations: The Example of Food Hygiene Standards

- Panel Technical Efficiency of Korean Companies in the Energy Sector based on Digital Capabilities

- Time-varying Investment Dynamics in the USA

- Preferences, Institutions, and Policy Makers: The Case of the New Institutionalization of Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance in Colombia

- The Impact of Geographic Factors on Credit Risk: A Study of Chinese Commercial Banks

- The Heterogeneous Effect and Transmission Paths of Air Pollution on Housing Prices: Evidence from 30 Large- and Medium-Sized Cities in China

- Analysis of Demographic Variables Affecting Digital Citizenship in Turkey

- Green Finance, Environmental Regulations, and Green Technologies in China: Implications for Achieving Green Economic Recovery

- Coupled and Coordinated Development of Economic Growth and Green Sustainability in a Manufacturing Enterprise under the Context of Dual Carbon Goals: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality

- Revealing the New Nexus in Urban Unemployment Dynamics: The Relationship between Institutional Variables and Long-Term Unemployment in Colombia

- The Roles of the Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate in the Current Account Balance

- Cleaner Production: Analysis of the Role and Path of Green Finance in Controlling Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

- The Research on the Impact of Regional Trade Network Relationships on Value Chain Resilience in China’s Service Industry

- Social Support and Suicidal Ideation among Children of Cross-Border Married Couples

- Asymmetrical Monetary Relations and Involuntary Unemployment in a General Equilibrium Model

- Job Crafting among Airport Security: The Role of Organizational Support, Work Engagement and Social Courage

- Does the Adjustment of Industrial Structure Restrain the Income Gap between Urban and Rural Areas

- Optimizing Emergency Logistics Centre Locations: A Multi-Objective Robust Model

- Geopolitical Risks and Stock Market Volatility in the SAARC Region

- Trade Globalization, Overseas Investment, and Tax Revenue Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Can Government Expenditure Improve the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service? – Take Wuhan as an Example

- Media Tone and Earnings Management before the Earnings Announcement: Evidence from China

- Review Articles

- Economic Growth in the Age of Ubiquitous Threats: How Global Risks are Reshaping Growth Theory

- Efficiency Measurement in Healthcare: The Foundations, Variables, and Models – A Narrative Literature Review

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm

- Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy

- Special Issue: Economic Implications of Management and Entrepreneurship - Part II

- Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study on Entrepreneurial Tendency of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA in the Context of the Interactive Model

- Bridging Brand Parity with Insights Regarding Consumer Behavior

- The Effect of Green Human Resources Management Practices on Corporate Sustainability from the Perspective of Employees

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation in Economics and Management Decision - Part II

- High-Quality Development of Sports Competition Performance Industry in Chengdu-Chongqing Region Based on Performance Evaluation Theory

- Analysis of Multi-Factor Dynamic Coupling and Government Intervention Level for Urbanization in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt

- The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Technological Innovation of Enterprises: Based on Empirical Evidences of the Implementation of Pollution Charges in China

- Environmental Social Responsibility, Local Environmental Protection Strategy, and Corporate Financial Performance – Empirical Evidence from Heavy Pollution Industry

- The Relationship Between Stock Performance and Money Supply Based on VAR Model in the Context of E-commerce

- A Novel Approach for the Assessment of Logistics Performance Index of EU Countries

- The Decision Behaviour Evaluation of Interrelationships among Personality, Transformational Leadership, Leadership Self-Efficacy, and Commitment for E-Commerce Administrative Managers

- Role of Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurship Across the Diverse Economic Stages: Insights from GEM and GLOBE Data

- Performance Evaluation of Economic Relocation Effect for Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations: Evidence from China

- Functional Analysis of English Carriers and Related Resources of Cultural Communication in Internet Media

- The Influences of Multi-Level Environmental Regulations on Firm Performance in China

- Exploring the Ethnic Cultural Integration Path of Immigrant Communities Based on Ethnic Inter-Embedding

- Analysis of a New Model of Economic Growth in Renewable Energy for Green Computing

- An Empirical Examination of Aging’s Ramifications on Large-scale Agriculture: China’s Perspective

- The Impact of Firm Digital Transformation on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: Evidence from China

- Accounting Comparability and Labor Productivity: Evidence from China’s A-Share Listed Firms

- An Empirical Study on the Impact of Tariff Reduction on China’s Textile Industry under the Background of RCEP

- Top Executives’ Overseas Background on Corporate Green Innovation Output: The Mediating Role of Risk Preference

- Neutrosophic Inventory Management: A Cost-Effective Approach

- Mechanism Analysis and Response of Digital Financial Inclusion to Labor Economy based on ANN and Contribution Analysis

- Asset Pricing and Portfolio Investment Management Using Machine Learning: Research Trend Analysis Using Scientometrics

- User-centric Smart City Services for People with Disabilities and the Elderly: A UN SDG Framework Approach

- Research on the Problems and Institutional Optimization Strategies of Rural Collective Economic Organization Governance

- The Impact of the Global Minimum Tax Reform on China and Its Countermeasures

- Sustainable Development of Low-Carbon Supply Chain Economy based on the Internet of Things and Environmental Responsibility

- Measurement of Higher Education Competitiveness Level and Regional Disparities in China from the Perspective of Sustainable Development

- Payment Clearing and Regional Economy Development Based on Panel Data of Sichuan Province

- Coordinated Regional Economic Development: A Study of the Relationship Between Regional Policies and Business Performance

- A Novel Perspective on Prioritizing Investment Projects under Future Uncertainty: Integrating Robustness Analysis with the Net Present Value Model

- Research on Measurement of Manufacturing Industry Chain Resilience Based on Index Contribution Model Driven by Digital Economy

- Special Issue: AEEFI 2023

- Portfolio Allocation, Risk Aversion, and Digital Literacy Among the European Elderly

- Exploring the Heterogeneous Impact of Trade Agreements on Trade: Depth Matters

- Import, Productivity, and Export Performances

- Government Expenditure, Education, and Productivity in the European Union: Effects on Economic Growth

- Replication Study

- Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: A Replication of Andersson (American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2019)

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Political Turnover and Public Health Provision in Brazilian Municipalities

- Examining the Effects of Trade Liberalisation Using a Gravity Model Approach

- Operating Efficiency in the Capital-Intensive Semiconductor Industry: A Nonparametric Frontier Approach

- Does Health Insurance Boost Subjective Well-being? Examining the Link in China through a National Survey

- An Intelligent Approach for Predicting Stock Market Movements in Emerging Markets Using Optimized Technical Indicators and Neural Networks

- Analysis of the Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion in Promoting Inclusive Growth: Mechanism and Statistical Verification

- Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size under Turnover Tax: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on SMEs

- Re-investigating the Impact of Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development, Institutional Quality, and Globalization on Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries

- A Compliance Return Method to Evaluate Different Approaches to Implementing Regulations: The Example of Food Hygiene Standards

- Panel Technical Efficiency of Korean Companies in the Energy Sector based on Digital Capabilities

- Time-varying Investment Dynamics in the USA

- Preferences, Institutions, and Policy Makers: The Case of the New Institutionalization of Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance in Colombia

- The Impact of Geographic Factors on Credit Risk: A Study of Chinese Commercial Banks

- The Heterogeneous Effect and Transmission Paths of Air Pollution on Housing Prices: Evidence from 30 Large- and Medium-Sized Cities in China

- Analysis of Demographic Variables Affecting Digital Citizenship in Turkey

- Green Finance, Environmental Regulations, and Green Technologies in China: Implications for Achieving Green Economic Recovery

- Coupled and Coordinated Development of Economic Growth and Green Sustainability in a Manufacturing Enterprise under the Context of Dual Carbon Goals: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality

- Revealing the New Nexus in Urban Unemployment Dynamics: The Relationship between Institutional Variables and Long-Term Unemployment in Colombia

- The Roles of the Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate in the Current Account Balance

- Cleaner Production: Analysis of the Role and Path of Green Finance in Controlling Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

- The Research on the Impact of Regional Trade Network Relationships on Value Chain Resilience in China’s Service Industry

- Social Support and Suicidal Ideation among Children of Cross-Border Married Couples

- Asymmetrical Monetary Relations and Involuntary Unemployment in a General Equilibrium Model

- Job Crafting among Airport Security: The Role of Organizational Support, Work Engagement and Social Courage

- Does the Adjustment of Industrial Structure Restrain the Income Gap between Urban and Rural Areas

- Optimizing Emergency Logistics Centre Locations: A Multi-Objective Robust Model

- Geopolitical Risks and Stock Market Volatility in the SAARC Region

- Trade Globalization, Overseas Investment, and Tax Revenue Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Can Government Expenditure Improve the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service? – Take Wuhan as an Example

- Media Tone and Earnings Management before the Earnings Announcement: Evidence from China

- Review Articles

- Economic Growth in the Age of Ubiquitous Threats: How Global Risks are Reshaping Growth Theory

- Efficiency Measurement in Healthcare: The Foundations, Variables, and Models – A Narrative Literature Review

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm

- Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy

- Special Issue: Economic Implications of Management and Entrepreneurship - Part II

- Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study on Entrepreneurial Tendency of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA in the Context of the Interactive Model

- Bridging Brand Parity with Insights Regarding Consumer Behavior

- The Effect of Green Human Resources Management Practices on Corporate Sustainability from the Perspective of Employees

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation in Economics and Management Decision - Part II

- High-Quality Development of Sports Competition Performance Industry in Chengdu-Chongqing Region Based on Performance Evaluation Theory

- Analysis of Multi-Factor Dynamic Coupling and Government Intervention Level for Urbanization in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt

- The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Technological Innovation of Enterprises: Based on Empirical Evidences of the Implementation of Pollution Charges in China

- Environmental Social Responsibility, Local Environmental Protection Strategy, and Corporate Financial Performance – Empirical Evidence from Heavy Pollution Industry

- The Relationship Between Stock Performance and Money Supply Based on VAR Model in the Context of E-commerce

- A Novel Approach for the Assessment of Logistics Performance Index of EU Countries

- The Decision Behaviour Evaluation of Interrelationships among Personality, Transformational Leadership, Leadership Self-Efficacy, and Commitment for E-Commerce Administrative Managers

- Role of Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurship Across the Diverse Economic Stages: Insights from GEM and GLOBE Data

- Performance Evaluation of Economic Relocation Effect for Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations: Evidence from China

- Functional Analysis of English Carriers and Related Resources of Cultural Communication in Internet Media

- The Influences of Multi-Level Environmental Regulations on Firm Performance in China

- Exploring the Ethnic Cultural Integration Path of Immigrant Communities Based on Ethnic Inter-Embedding

- Analysis of a New Model of Economic Growth in Renewable Energy for Green Computing

- An Empirical Examination of Aging’s Ramifications on Large-scale Agriculture: China’s Perspective

- The Impact of Firm Digital Transformation on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: Evidence from China

- Accounting Comparability and Labor Productivity: Evidence from China’s A-Share Listed Firms

- An Empirical Study on the Impact of Tariff Reduction on China’s Textile Industry under the Background of RCEP

- Top Executives’ Overseas Background on Corporate Green Innovation Output: The Mediating Role of Risk Preference

- Neutrosophic Inventory Management: A Cost-Effective Approach

- Mechanism Analysis and Response of Digital Financial Inclusion to Labor Economy based on ANN and Contribution Analysis