Abstract

Science, technology, and innovation (STI) are fundamental elements for achieving development and sustainable growth. Developing STI is also currently the main challenge faced by countries, especially those with emerging economies, making it essential that these countries implement comprehensive policies to generate a knowledge-based society. Institutions and policy-makers are responsible for defining the rules by which a society is governed. In particular, it is widely held that institutions should place special emphasis on establishing property rights, legal systems, customs, and the political systems based on which central planners should govern. From this perspective, this study integrates qualitative and quantitative analysis through a preference model with three types of STI policy-makers and projections to better clarify the requirements for new STI institutions in Colombia. It does so by using the time series of STI spending generated by the Administrative Department of STI (Colciencias) from 1968 to 2018. The simulation results show that among the chosen agents, the STI policy preferences of the scientist-manager yield economic outcomes closest to the optimal level. In contrast, the yield of the politician’s preferences is suboptimal and even negative at certain points. These results have implications for public policy, as poor policy choices may lead to undesirable results in terms of STI policy application, implementation, and execution. These findings are important for strengthening STI policy. They also indicate the important role of the government in transforming Colombia from being a receiver of technology to being a generator of knowledge, technology, and innovation in line with the requirements of the country’s population and its natural resource endowments.

1 Introduction

Institutions are fundamental for establishing the rules of the game and the objectives to be achieved in regard to a country’s social, growth, and development needs. Institutions also define incentives for agents and interest groups, who adapt their behaviour accordingly and take into account existing and potential market failures. The advance of science, technology, and innovation (STI) requires the development of appropriate institutions that transform the individual or specific preferences of some interest groups into collective results that solve the problems of society. However, preferences for the means and strategies with which to carry out this function differ among policy-makers, scientists, decision-makers, investors, and citizens because the perceptions of and perspectives on STI vary between the generators and beneficiaries of knowledge.

According to one definition, an institution “specifies the players whose behaviour is bound by its rules; the actions the players must, may, must not, or may not take; the informational conditions under which they make choices; their timing; the impact of exogenous events; and the outcomes that are a consequence of these choices and events. The game form is transformed into a game when players are endowed with preferences over outcomes” (Shepsle, 2010). Regarding STI, it is important to determine adequate rules and requirements along the entire value chain to transform the dependence on other countries’ knowledge generation into inputs for a knowledge-based society. These elements are the key to new STI institutionalization, taking into account preferences, institutions, and policy-makers. This study aims to support the institutionalization of new STI policies and governance in Colombia initiated through the creation of the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MSTI).

Institutions are fundamental for the success of countries. Acemoglu and Robinson (2013) demonstrated that the arbitrary rules implemented by extractive institutions destroy a country both politically and economically. In contrast, inclusive institutions strengthen economic growth and development in the long run through the rule of law, which is based on legality, constitutionality, judicial independence, rights, and duties. The rule of law, in turn, stimulates economic processes, business, and investment by ensuring legal security and predictability, the autonomy and transparency of the legal system, and the protection and guarantee of property. These precepts are fundamental for good governance and must be considered in the formulation of new institutions for STI. In particular, transparency, independence, and rules that allow research and development (R&D) investments in the private sector should be promoted as key elements in creating new knowledge, technologies, and innovation offering an adequate rate of return and improvements in productivity and competitiveness (Brown & Martinsson, 2018; Impact Task Force, 2021; Kenny, 2020). In this study, we aim to address the challenges of developing appropriate institutions in the Colombian context.

The formulation of STI policy requires different instruments and tools, providing direct help to researchers and innovators and refining the enabling environment for scientific and innovation activities that generate different forms of technological, social, and institutional innovations. These innovations range from the incremental to the radical and from low-tech to high-tech, which implies stakeholders, networks, and the situations that allow learning, technology development, and adoption and diffusion (Chaminade & Padilla-Perez, 2014; Cunningham et al., 2013).

The government can support STI by managing and promoting economic growth and the modernization of the state to strengthen efficiency and effectiveness through decentralization. This strategy implies greater independence and transparency in public management to orient STI towards sustainable development and the creation and distribution of knowledge. That said, out of 38 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 15% do not have an MSTI, and among Latin American countries, 61% do not have an MSTI.

This study aims to highlight the main factors that can affect the new institutionalization of STI governance in Colombia by considering the preferences and role of policy-makers in operating the new MSTI. By adopting an empirical strategy that treats different agents as policy-makers and their preferences as a functional form, this study considers the appropriate policies for promoting STI in all economic sectors, increasing investment, and delivering results. This policy emphasis is justified because STI can increase production factors, improve efficiency by optimally allocating these production factors, and boost innovation rates, all of which are recognized as main forces in economic growth and development (Bekhet & Latif, 2017; Zaman & Goschin, 2010).

Thus, by studying the preferences of different stakeholders, this article aims to investigate new STI institutions in Colombia considering the importance of the adequate formulation and application of governance institutions to promote development and growth based on knowledge and technological change.

Institutions are the focus because understanding institutions implies understanding the complex causation and combinations of factors that make it possible to promote appropriate STI policy and instruments. This topic has received limited attention from previous studies, especially in developing countries. Additionally, this study focuses on transitions achieved through the creation of the MSTI, which is in line with the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2019). According to UNCTAD STI policy strategy, instruments, processes, and governance require policy harmonization and strategic coherence between STI and many related policy improvement issues.

However, policy experimentation with new types of STI policies is necessary to guarantee compliance with current policies to meet global challenges, where institutions play an important role in addressing effective STI processes (OECD, 2022b; UNCTAD, 2019). Hence, this study performs a series of simulations to determine the factors that could influence new STI institutionalization in the Colombian context.

The main contributions and scope of this research are as follows: i) This analysis contributes to both knowledge and the literature by focusing on institutions and the significance of governance institution quality in promoting STI. ii) It attempts to capture the STI policy preferences of different stakeholders who promote development and economic growth in Colombia.

This article starts with a brief theoretical overview of institutions and preferences related to STI from a review of the theoretical and empirical literature. It then presents the literature review and continues with the data and methods used in this study. Next, the main results are discussed. Finally, tentative conclusions are drawn.

2 Literature Review

This section provides a literature review of two approaches, theoretical and empirical, to determine the importance and relationships between institutions and policy-makers within the STI framework.

2.1 Theoretical Literature Review

Institutions play an important role in defining the rules of the game and limits to behaviour. In this way, they create certain incentives for or motivate actions by agents, who adapt or change their behaviour accordingly to fulfil objectives, achieve improvements in the system, and generate expected outcomes. These actions support STI production and the diffusion of new knowledge (OECD, 2023; Schot & Steinmueller, 2018; Shan, 2019).

Examining the interaction between institutional arrangements and the preferences of stakeholders can provide important insights, improving the understanding of the conditions under which new institutionalization and practices are incorporated (Garrett & Lange, 1995; Goyer, 2011). This, in turn, allows us to understand how new governance and institutional models such as MSTIs can guarantee adequate research management based on diverse preferences due to the presence of institutional constraints, especially constraints on STI resources (Jung et al., 2015).

Institutions are organs that pre-eminently perform a function in the public interest, such as educational, cultural, or charitable functions. They are most often applied to established social orders that represent recognized organizations in matters of social interaction and cooperation (Godwin et al., 2021; Kwemarira et al., 2020). Likewise, institutions set the rules of the game in a society. More formally, they represent the restrictions devised by humans that shape human interaction (Falkenhain, 2020; Thorhauge, 2013). Institutions are not static or simply a given set of rules. They are dynamic in the sense that they change and evolve into new organizational forms in pursuit of the public interest (North, 1990).

From the institutional perspective, the presence of incomplete information has important consequences for the potential to coordinate the different decisions that must be made by policy-makers (Chuang et al., 2012; De Geest & Kingsley, 2019). Those agents who at any given time are influenced by uncertainty, risk or a lack of incentives to efficiently allocate resources will tend to generate an economic environment characterized by a lack of cooperation or by inefficient coordination between the different decisions made by the representative agent (Van der Heijden, 2023; Wall, 2019). The institutional literature argues that the problem of incomplete information can be mitigated if the policy-maker has sufficient information and knows the rules established for the operation of new institutions (European Commission, 2017a,b; Nordström, 2022).

According to the institutional approach, information asymmetry plays a fundamental role in decision-making. The general results show that in the presence of information asymmetries in an exchange, one of the agents undertakes transactions given privileged information that the other agent does not know, which generates relevant distortions in decision-making (North, 1990).

In the formulation and application of effective policies and the development of efficient solutions, a set of intensive knowledge is required. Here, researchers, operators, stakeholders, politicians, and other technicians should participate in different stages of the policy cycle, and such participation guarantees pertinence and effective results (Bruce et al., 2004; Kanbur, 2002; Marra et al., 2018).

According to Jang (2000), the creation of MSTIs worldwide has been motivated by different factors. i) The first factor is the increase in global organizations interested in STI-based development, which has positively affected investments and the founding of enterprises through MSTIs. ii) The second is the positive experience of other countries with MSTIs, which has accelerated the establishment of such ministries worldwide. iii) The third is the greater likelihood that developed countries that have become knowledge societies will adopt MSTIs; iv) The fourth is the ability of countries with an interest in the defence industry and its development to use MSTIs to more effectively promote and mobilize STI resources and achieve greater competitiveness through the sales of arms and military technology. v) Finally, the fifth factor is the potential for MSTIs to generate positive effects on functional and resource mobilization and decrease institutional effects over time.

In the context of this new institutionalization of STI governance, the Colombian government, policy-makers and decision-makers should determine the most effective role for the country’s new MSTI and the investment requirements and effects that will make it possible to strengthen STI processes for the benefit of society and the development of the country.

Information institutions play an important role in the creation of new institutions such as MSTIs to determine priorities, make informed choices, and implement better policies for STI. Considering the value of data for STI ecosystems and the opportunities for creating private and public returns on investment based on knowledge and STI processes and the generation of quality information for these institutions can increase public service efficiency, foster transparency, and enhance citizens’ trust in the participation of new MSTIs (OECD, 2017, 2022a).

Moreover, successful scientific research, technology deployment, and innovation require information institutions that can fund and guide research by identifying priority problems, assembling research teams, and training future scientific leaders. No less important are efforts to integrate the country’s STI capacity with national programmes to promote economic development. Here, fostering collaboration between industry, academia, and government is fundamental for ensuring that university research results are disseminated to the public and applied by the public and private sectors to resolve problems and improve the welfare of the population (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2004; Open Access Government, 2023).

2.2 Empirical Literature Review

Different studies have demonstrated that institutions are fundamental for economic outcomes and development, particularly for improving investment, and they have suggested that institutions play a crucial role in the preferences and expectations of society (Acemoglu et al., 2005; Kanani & Larizza, 2021; Tharanga, 2019). In the case of STI, institutions make it possible to manage market failures and can help generate a knowledge-based society, which itself is a key element in promoting greater specialization in the productive sector and human capital (Lungu, 2019; Reif, 2011; UNIDO, 2021). In this process, the analysis of institutions and their relationships with different interest groups allows for the design of effective policies (De Smedt & Borch, 2022; OECD, 2021).

In this context, studies of the political economy of investment, especially in STI, suggest that institutional quality shapes economic preferences by altering expectations about costs, benefits, and risks (North et al., 2009). These factors are difficult to measure and manage because the generation of knowledge is characterized by uncertainty and intangible results.

STI can become a cornerstone of the economy, serving as an appropriate input for strengthening the quality of governance institutions in cases where the relationship between institutional quality and economic development and growth is very complex. Governance that fosters STI should facilitate economic activities and determine the behaviour of economic agents and stakeholders. It should also help optimize and improve both collective and individual economic decisions based on evidence and scientific and technological findings (Al Mamun et al., 2017; Demetriades, 2006).

From the perspective of institutions and STI, another important concept is knowledge-based economies, which are defined as “economies which are directly based on the production, distribution, and use of knowledge and information” (OECD, 1996, p. 7). This definition implies the importance of knowledge-intensive activities to promote growth and development. Institutions and STI are the driving force in this concept but require enormous amounts of capital and adequate policies that encourage the application of innovation and new technologies to promote stability and social prosperity (APEC Economic Committee, 2001; Council for Economic Planning and Development, 2000; Hsu et al., 2008).

STI policies and instruments must be comprehensive and be the result of a decision-making process in which all impacts underlying alternative solutions must be considered. The key stages of formulating policies that require scientific knowledge include design and preparation (policy proposals are formulated) and evaluation and revision (the potential impacts of different policy choices are evaluated). Moreover, multi-disciplinary cooperation and collaboration in knowledge production are fundamental for guaranteeing an effective transfer of data and information among people involved in the internal process of policy-making and the integral evaluation of the advantages or disadvantages of proposed policies (European Commission, 2015, 2017a,b; Pohl, 2008). Based on these issues, it is important for a new institutionalization to analyse the preferences and role of policy-makers to determine strategies that guarantee the pertinence of new STI institutions through the MSTI in Colombia.

Analysing institutions and preferences is key to preventing governance failure because such analysis allows us to predict the actions and processes related to the mechanisms that regulate the interactions among the different stakeholders involved as well as possible positive and negative outcomes. Adequate institutions and networks determine successful STI governance and policy and include the following (McKelvey et al., 2019): i) the relations among heterogeneous public and private stakeholders that are related to developing, disseminating, and utilizing new knowledge for science and progress technology; ii) the norms, incentives, and institutions that support the regulation and standardization of interactions among these individuals, organizations, and other stakeholders; iii) monitoring and following up on the STI system and stakeholders to assess the results, goal fulfillment, and contributions of stakeholders; and iv) the generation of public knowledge through collective action for STI, which is impacted by norms, incentives, and institutions through monitoring and evaluation activities. In this context, this study seeks to conduct simulations to determine for different policy-makers the trends in STI policy in Colombia. These trends can then be used as input for new institutionalization with the creation of the new MSTI.

According to Bernard (1968), every study on organizations must assume that they are formed by a group of individuals, each with a different scheme of preferences, motivations, and interests. Bernard (1968) tried to explain how these elements of behaviour can evolve within an organization until they reach a degree of cooperation in which each individual is able to contribute selflessly to the development of the organization since the individual changes his or her own value system to a relatively common system. To do so or to perform any study on organizational dynamics in general, a profile of the individuals who are policy-makers, managers, politicians, or decision-makers must first be provided.

3 Methods and Data

Regarding preferences and institutions, the most recent literature (Persson & Tabellini, 2000) includes, among the main stability factors, agents' level of knowledge of a particular issue and the good management and efficient allocation of scarce resources by policy-makers. The most general models represent preference functions considering the existence of two possible policy-makers in the context of resource management.

This study follows the indicators and variables proposed by the 2015 Frascati Manual developed by the OECD (2015) for investments in R&D that comprise creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge – including knowledge of humankind, culture, and society – and to devise new applications of available knowledge. Three types of activities are covered: basic research, applied research, and experimental development.

According to Ricyt (2018), the Latin American context uses variable investments in science, technology, and innovation activities (STIAs). Such activities include innovation activities, scientific and technological services, support for scientific and technological training, R&D and administration, and other support activities. These two variables make it possible to assess simulations based on the differences between R&D and other STI investments, taking into account the fact that OECD countries measure only R&D. Additionally, the variables can be used to analyse two scenarios.

For simplicity, it is assumed here that there are three types of STI policy-makers who manage and control two decision variables: STIAs and topics related to R&D. One of these representative agents is a business maximizer of resources, i.e., a businessperson-entrepreneur. Another is a politician, and the last is a scientist, i.e. an academic manager and expert on STI issues. The characteristic equation of the preferences of the businessperson-entrepreneur has the following structure:

Regarding institutions, the recent literature includes various stability factors in the management of policies related to spending on STIAs and resources allocated for R&D in countries. The management of decisions is formalized based on the preferences and inclinations of each representative agent given the decision variables. Equation (1) defines the parameters and standard weights to determine the weight of the variables in each of the possible decisions of the businessperson.

For the scientist-manager, the preference is as follows:

Here,

Equation (3) shows the importance that spending on R&D should have for the preferences of policy-makers

The model assumes that the control variables determined by STIAs and R&D are the main policy instruments for policy-makers in STI. It should also be assumed that in the short term, the policy-maker is elected, thereby representing different interests given the policy-maker’s preference function. In this way, the difference in the preferences of the two representative agents is specified by the functional forms set in equations (1) and (2) for the businessperson-entrepreneur and the scientist-manager, which allows us to establish the preferences that each representative agent has for STIAs or R&D.

Solving the main interactions determined by equations (1) and (3), the relevant equation is expressed as follows:

When solving, the relevant relationship is shown in equation (5):

Equation (5) tells us that the businessperson-entrepreneur is more interested in control over current and future STIAs. In this sense, the equation additionally warns that R&D may be given little consideration in governance by this policy-maker.

For the scientist-manager, solving the interactions given by equations (2) and (3), the following relationship is specified in equation (6):

The relevant relationship is shown in equation (7) as follows:

According to equation (7), which shows the different relationships for the scientist-manager, this representative agent is more concerned with the impact that the two variables, STIAs and R&D, may have on the economy as a whole, without loss of generality. This policy maker is interested in having an R&D rate that, to the greatest extent possible, does not deviate from its natural rate and that does not side-line the effects or implications of STIAs in regard to economic growth. The question is how to determine the optimal rates given the preferences of each policy-maker in terms of the contribution of each activity to growth.

The STIA rate for the businessperson-entrepreneur is determined based on equation (5) by solving with respect to the control variables. Carrying out the respective operations yields

When deriving with respect to

By carrying out the respective operations, the optimal STIA spending rate is obtained for the businessperson:

The STIA rate for the scientist-manager is obtained based on equation (7) operating with respect to the control variables.

When deriving with respect to

By operating and solving, the optimal STIA spending rate is determined for the scientist-manager:

Here,

Using the same assumptions for the preferences of each policy-maker, one can determine the main relationships and outcomes for the politician as a central planner.

This document uses the time series of STI spending generated by the Administrative Department of STI (Colciencias) from 1968 to 2018. We use data published by the National Planning Department, Cotte and Andrade, 2019, and the World Bank for Colombia to capture investments in STIAs and the R&D series. The variables used in the various techniques and the time periods were selected based on the availability and reliability of the available data. These data were the basis for making the projections and estimates for each scenario based on the preferences of policy-makers for a projected period of 19 years.

For the simulations and their respective projections, the time series are used to predict the behaviour and the main results. STIAs and R&D are taken as the main control variables, given that they are the main indicators that an MSTI would manage. The general structure in time series for predictions takes into account the following general structure (equation (10)):

The values of the past are taken into account to make the future predictions of each policy-maker based on the data of the previous institution that was in charge of managing the variables of STI, particularly those related to STIAs and experimental R&D.

The predictions of the following successive periods satisfy the following structure (equation (11)):

Therefore, the following is assumed (equation (12)):

Similarly, for the following successive periods (equation (13)),

4 Empirical Results and Discussion: Simulations for Policy Makers

To conduct the simulations, we follow the methods explained in the previous section based on equations (8) and (9). Additionally, the most recent and robust methodology developed by Cotte and Andrade (2019) is used. The different characteristics of the variables are analysed. Furthermore, the fluctuations in the time series are used as a study instrument, employing the trends, deviations, periodicity, duration, amplitude, variability, and general behaviour of the data reported by the Colombian Observatory of Science and Technology (2019).

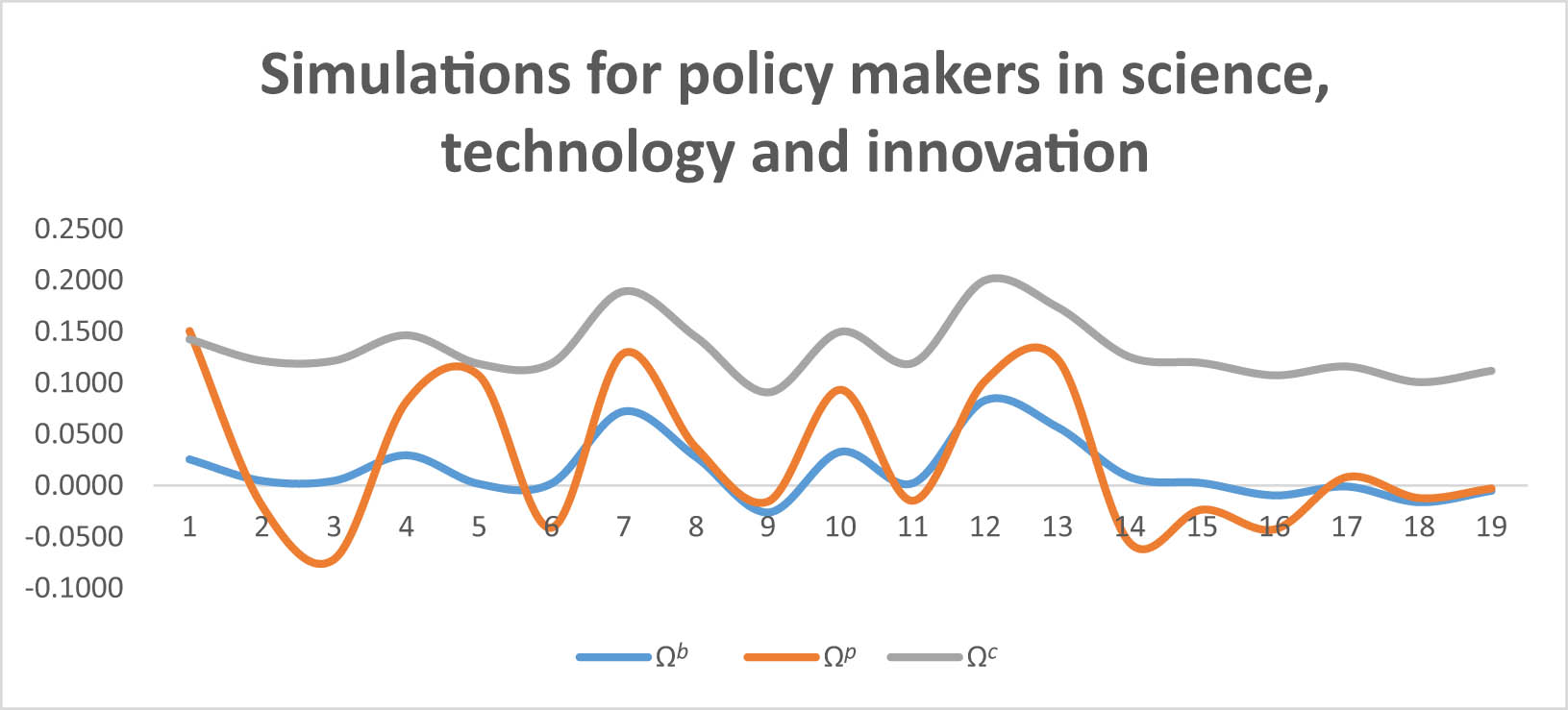

Table 1 shows the main estimates for each of the central planners and their contribution to the decision variable in the management of STI policy. According to the simulations, the results show great variability in terms of the possible behaviour of the main control variable in reaction to the policy.

Simulations for policy-makers

| Period | Ω b | Ω p | Ω c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0254 | 0.1505 | 0.1424 |

| 2 | 0.0045 | −0.0195 | 0.1215 |

| 3 | 0.0046 | −0.0718 | 0.1216 |

| 4 | 0.0294 | 0.0819 | 0.1464 |

| 5 | 0.0015 | 0.1071 | 0.1185 |

| 6 | 0.0018 | −0.0412 | 0.1188 |

| 7 | 0.0721 | 0.1288 | 0.1891 |

| 8 | 0.0278 | 0.0370 | 0.1448 |

| 9 | −0.0262 | −0.0155 | 0.0908 |

| 10 | 0.0328 | 0.0933 | 0.1498 |

| 11 | 0.0023 | −0.0149 | 0.1192 |

| 12 | 0.0830 | 0.1020 | 0.2000 |

| 13 | 0.0568 | 0.1232 | 0.1738 |

| 14 | 0.0082 | −0.0558 | 0.1252 |

| 15 | 0.0024 | −0.0236 | 0.1194 |

| 16 | −0.0097 | −0.0427 | 0.1073 |

| 17 | −0.0010 | 0.0081 | 0.1159 |

| 18 | −0.0162 | −0.0122 | 0.1008 |

| 19 | −0.0052 | −0.0029 | 0.1118 |

Ω b , the optimum rate for the businessperson-entrepreneur given her preferences; Ω p , the optimum rate for the politician given her preferences; Ω c , the optimum rate for the scientist-manager given her preferences.

Source: Cotte and Andrade (2019).

The simulations for the different policy-makers over 19 periods show that the variables STIAs and R&D, which are the variables to be managed by the businessperson, politician, and scientist-manager, lead to different results. Without loss of generality, the optimal results are obtained by the scientist-manager because she shows great interest in STIAs and the effective allocation of R&D resources. In contrast, the politicians and businessperson show negative results for some periods, generating losses and inefficiency in resource allocation. According to Brookes et al. (2017), the integration of science with the common good and society and the achievement of a more influential position for science require a scientific manager and leader to support change for the better worldwide.

Moreover, researchers with management and leadership skills aim to organize better projects. They also aim to more effectively complete the adequate transfer and application of project results and to establish appropriate strategies to promote new knowledge, technology, and innovation. Furthermore, they aim to foster innovation and collaboration among different stakeholders, such as those from the government, the productive sector, universities, society, and research centres. Finally, they aim to employ others from national and organizational contexts and motivate them to achieve project objectives (Jason & Macnaghten, 2011; Pozenel, 2018).

However, identifying a policy maker with a scientist-manager profile is not always possible because different power relations or political interests can influence the selection. Thus, it is important to establish the perspective and expected results of the new institutionalization and objectives of STI governance. This implies a good framework that includes (Pardo et al., 2019) adequate regulations and institutions, patterns of governance, interactions and patterns of negotiation between STI public institutions and stakeholders, new forms of self-governance (including new actors in helices four and five), independence, openness, and transparency through a participatory dialogue.

Figure 1 shows cyclical trends at the beginning of the analysis period. However, by the end, relative stability in the behaviour of the series emerges. These results indicate that based on the preferences of each policy-maker, stability should be considered within the optimal management of policies given the principles of independence and transparency and the effective allocation of resources for the entire system (ESCAP, 2018). Figure 1 shows the fluctuating trends for the variables of interest used for STIAs and R&D as one of the objectives of the preferences of each policy maker. Table 2 shows projections that, on average, yield the best result of 0.13 for the scientist-manager, with a minimum value of 0.09 and a maximum value of 0.2. For the businessperson‒entrepreneur, the results show an average of 0.01, with a minimum value of −0.02 and a maximum of 0.08. For the politician, the results show an average value of 0.02, with a minimum of −0.07 and a maximum of 0.15. The projections and their tendencies determine that the best results would be achieved by a policy-maker with an adequate technical profile and with the preferences of the scientist-manager.

Trends for policy-makers in STI. Source: Cotte and Andrade (2019).

Summary statistics

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ω b | 19 | 0.0154895 | 0.0291638 | −0.0262 | 0.0830 |

| Ω p | 19 | 0.0279895 | 0.0713368 | −0.0718 | 0.1505 |

| Ω c | 19 | 0.1324789 | 0.0291695 | 0.0908 | 0.2000 |

Source: Calculations by the authors.

Ω b , The optimum rate for the businessperson-entrepreneur given her preferences; Ω p , The optimum rate for the politician given her preferences; Ω c , The optimum rate for the scientist-manager given her preferences.

Notably, the coordination and consensus among the different agents participating in this system in all scenarios are the best outcomes. That is, policies coordinated in all sectors are perhaps the first-best alternative. Moreover, optimality, given the scarcity of resources overall, would yield an efficient allocation and the best effects in the medium and long terms, considering the new institutional framework and possible institutional arrangements that could reduce uncertainty and transaction costs. Indeed, in modern theories of economic growth, such factors mark the difference between high-, medium- and low-income countries.

These results indicate the importance of the evolution of STI policies similar to those of countries such as China, Japan, the Republic of Korea, and Singapore, which are characterized by Epstein et al. (2007) as follows. i) These policies facilitate technology transfer and diffusion and generate qualified human resources in science and technology. ii) The scope and objectives of STI policy have gradually been extended from the stimulation of industrial development and economic growth objectives to innovation and social and environmental objectives for inclusive and sustainable growth. iii) These countries have prioritized frontier technology development as a policy objective, generating specific instruments and mechanisms to promote advances in this regard in fields such as the environment, digital infrastructure, and R&D. iv) Finally, public sector innovation is viewed as a tool for improving public service delivery and supporting the development of technological and innovation capabilities and markets through the adoption and promotion of new technologies with applications for managing human resources or deploying new regulatory frameworks. These elements are key to designing appropriate STI governance to promote development, equality, and growth. In particular, in emerging countries, this requires building innovation capabilities in the construction of their own development pathways to address economic, environmental, and social aspects based on knowledge, new technologies, and innovation.

To determine the reliability of the estimated projections, consistency, and sufficiency analyses are performed for the series. Consistency is a measure of the extent to which membership strength in the causal configuration is consistently equal to or less than membership in the outcome (Knott, 2018). Coverage applies to the proportion of the sum of the membership scores in an outcome that a particular configuration explains. In other words, coverage explains how many cases are covered by a sufficient configuration for a given outcome.

According to Licht (2015), the only way to maintain innovation in the productive sector or large knowledge-intensive industries is to invest in R&D. Such investment constitutes a good plan that will help firms produce their own technologies and innovations, potentially guaranteeing them a place as pioneers in their sectors. It will also allow firms to access better prices and new markets, secure a competitive advantage, and promote the effectiveness of R&D investments. Higher R&D enables higher profits, growth, and market value per unit of R&D investment. Conversely, when fewer companies invest in productive R&D, there is lower or negative innovation, which could drive lower growth in a country or region.

Another important point is the importance of public investment in R&D, considering the following (Cotte & Jimenez, 2019): i) R&D expenditure is a significant driver of competitiveness and productivity, which generates economic growth. ii) Government support for R&D reduces the costs of research and thus stimulates corporate R&D spending. iii) The public sector can help compensate for corporate R&D investment below the socially optimal level because the results of research and innovation can be used and are available to all firms and society as a whole. iv) Finally, it should be ensured that public expenditure does not decrease private investment in R&D. These elements are very important for achieving an effective STI policy that promotes public and private investment in R&D and STIAs. Such investment is fundamental for promoting growth, competitiveness, and development in the whole economy and benefits the population.

According to these results, in the new institutionalization of STI governance in Colombia, it is important for the new MSTI to analyse different stakeholders (UNCTAD, 2019). These include the following: i) The first is the research system, which represents the ability to learn and apply the knowledge required to build a local knowledge base. ii) Second, intermediary organizations compensate for a basic systemic failure in the connection with generators and users. iii) Third, the education system improves the quality of the human capital available to firms, governments, and research institutions and can change the needs of industries, workers, and consumers. iv) Fourth, civil society and citizens are fundamental for focusing STI policy on meeting social challenges. v) Fifth, the government is key to establishing a consensus on STI policy priorities, directing public resources to important areas, removing obstacles, designing and enforcing regulations and standards, and attempting to improve framework conditions through public policies. vi) Finally, firms and entrepreneurs have the ability to learn, absorb, innovate, and commercialize new knowledge and technologies with an innovative effect.

Moreover, new STI governance must include the following issues (UNCTAD, 2019): The first is a strategic reflection on costs and benefits. The second is a policy orientation towards structured application in the ongoing and planned policy processes in Colombia. The third is transformative change based on evidence. The fourth is being systemic. The fifth is being participatory to engage key government and non-governmental stakeholders from the country to guarantee that the analysis and recommendations are relevant and actionable. The sixth is being context-sensitive to ensure that the advantages and limitations of the local context are sufficiently considered. The seventh is being evidence-based to ensure the use of good quantitative and qualitative data relevant to the country's context. viii. Finally, the eighth is capacity building for consolidating existing and building new capacities of STI stakeholders with key roles in the STI system. The simulations performed in this study demonstrate the importance of these issues for contributing knowledge to solve the main challenges of the country.

The findings of this study are important as input for the analysis and evaluation of STI policy in Colombia, as it is newly institutionalized under the MSTI. An appropriate policy will allow the country to move from being a consumer to being a generator of STIs that suits the local requirements and the local context to solve economic, social, and environmental problems based on knowledge as a driver of growth, sustainable development, and progress.

5 Conclusions

This study analysed the new institutionalization of STI in Colombia and the role of policy-makers’ preferences with the aim of clarifying the prospects for improving STI governance in the country. It used qualitative and quantitative methods and determined the main factors that will affect the new institutionalization of STI governance in Colombia in terms of the preferences and role of policy-makers operating the new MSTI.

The results indicate that the new institutionalization of STI governance implies guaranteeing transparency, independence, and rules that promote and strengthen R&D investments, especially in the private sector. This can achieve the generation of new knowledge, technologies, innovation, entrepreneurship, and improvements in productivity and competitiveness as key elements in promoting economic growth and development.

The results from the simulations showed wide variability in the potential behaviour of the main variables in terms of the policy. Furthermore, the trends are cyclical, indicating that the optimal management of policies must be based on independence, transparency, and effective resource allocation.

The main implications of this study are related to the importance of STI in transforming the economy by generating greater growth and development in a knowledge-based society. In contrast, the limitations of this study are the need to analyse other factors and aspects that can affect STI governance and to evaluate the decision-making process based on differences in the profile, interest, and knowledge of policy-makers.

Regarding scientific policy and its implementation, this study shows the importance of public policy-makers considering decision variables for the efficient allocation of scarce R&D resources together with general STIAs in the context of improvements in the welfare of the population. Moreover, STI policy needs to analyse regional societal challenges and adjust competitiveness and innovation systems based on interregional requirements and gaps to decrease disparities in the country.

Modern theories addressing the growth and development of countries hold that the variables differentiating high-income from low-income countries include the adequate use and allocation of resources to R&D, incentives for science, increases in technology usage and the encouragement of innovation. These variables are fundamental for creating the conditions necessary to stimulate the growth of countries.

This work also shows the implications of implementing social policies related to economic agents’ preferences in terms of benefits from advances in STI for countries’ productivity [26], living conditions and, thus, the competitiveness of each region. Structural reforms and their implementation are essential for achieving a society that advances with the new industrial revolution based on the knowledge-generating economy, where the new institutionalization of STI can include the political economy of new advances in STI to increase and manage the globalized nature of STI and to determine power relations with stakeholders. These elements require further research to improve STI governance and establish the policy impacts to achieve objectives and effectively promote STI among different stakeholders in Colombia.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors accepted the responsibility for the content of the manuscript and consented to its submission, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. CIPM wrote the article, designed and performed analysis. AC wrote the article, contributed in data analysis.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

Article note: As part of the open assessment, reviews and the original submission are available as supplementary files on our website.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, A. (2013). Why nations fail? The origins of power, prosperity and poverty (p. 529). London: Profile Books Ltd.10.1355/ae29-2jSearch in Google Scholar

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2005). Chapter 6 Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. In P. Aghion & S. N. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth (Vol. 1, Part A, pp. 385–472). doi: 10.1016/S1574-0684(05)01006-3.Search in Google Scholar

Al Mamun, M., Sohag, K., & Hassan, M. (2017). Governance, resources and growth. Economic Modelling, 63, 238–261.10.1016/j.econmod.2017.02.015Search in Google Scholar

APEC Economic Committee. (2001). Towards Knowledge-based Economies in APEC.Search in Google Scholar

Bekhet, H., & Latif, N. (2017). Highlighting innovation policies and sustainable growth in Malaysia. International Journal Innovation Management Technology, 8(3), 228–239.10.18178/ijimt.2017.8.3.734Search in Google Scholar

Bernard, C. (1968). The functions of the executive. Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Brookes, R., Wong, B., & Ho, S. (2017). Why scientists should have leadership skills. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/why-scientists-should-have-leadership-skills/.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, J., & Martinsson, G. (2018). Does transparency stifle or facilitate innovation?. Management Science, 65(4), 1600–1623. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2017.3002.Search in Google Scholar

Bruce, A., Lyall, C., Tait, J., & Williams, R. (2004). Interdisciplinary integration in Europe: The case of the fifth framework programme. Futures, 36, 457–470. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2003.10.003.Search in Google Scholar

Chaminade, C., & Padilla-Perez, R. (2014). The Challenge of alignment and barriers for the design and implementation of science, technology and innovation policies for innovation systems in developing countries. Papers in Innovation Studies, No. 2014/26, Centre for Innovation, Research and Competence in the Learning Economy (CIRCLE), Lund University, Lund.Search in Google Scholar

Chuang, S. C., Kao, D. T., Cheng, Y. H., & Chou, C. A. (2012). The effect of incomplete information on the compromise effect. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(2), 196–206. doi: 10.1017/S193029750000303X.Search in Google Scholar

Colombian Observatory of Science and Technology. (2019). Science and Technology indicators 2018. https://www.ocyt.org.co/proyectos-y-productos/informe-anual-de-indicadores-de-ciencia-y-tecnologia-2018/.Search in Google Scholar

Cotte, A., & Andrade, J. (2019). Expenditure in science, technology and innovation activities. In Pardo, C and Cotte, A, Science and Technology Indicators (pp 39–66). Bogotá, Colombia: Colombian Observatory of Science and Technology.Search in Google Scholar

Cotte, A., & Jimenez, C. (2019). Effects of expenditures in science, technology and R&D on technical change in countries in Latin America and the caribbean. In C. Pardo, A. Cotte, & M. Fletscher (Eds.), Analysis of Science, Technology, and Innovation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Council for Economic Planning and Development. (2000). Knowledge-based Economy Development Plan, Taipei, 2000.Search in Google Scholar

Cunningham, P., Edler, J., Flanagan, K., & Laredo, P. (2013). Innovation policy mix and instrument interaction: A review. Nesta Working Paper 13/20. November 2013.Search in Google Scholar

De Geest, L., & Kingsley, D. (2019). Endowment heterogeneity, incomplete information & institutional choice in public good experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 83, 101478. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2019.101478.Search in Google Scholar

De Smedt, P., & Borch, K. (2022) Participatory policy design in system innovation. Policy Design and Practice, 5(1), 51–65. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2021.1887592.Search in Google Scholar

Demetriades, S. (2006). Law, Finance, institutions and economic development. International Journal Finance and Economics, 11, 245–260.10.1002/ijfe.296Search in Google Scholar

Epstein, J., Duerr, D., Kenworthy, L., & Ragin, C. (2007). Comparative employment performance: A fuzzy-set analysis. In L. Kenworthy & A. Hicks (Eds.), Method and substance in macrocomparative analysis. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230594081_3Search in Google Scholar

ESCAP. (2018). Evolution of Science, Technology and Innovation Policies for Sustainable Development: The Experiences of China, Japan, the Republic of Korea and Singapore. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/UN_STI_Policy_Report_2018.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. (2015). Better Regulation ‘Toolbox (Brussels).Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. (2017a). Better Regulation Guidelines (Brussels).Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. (2017b). Quality of Public Administration. https://reform-support.ec.europa.eu/document/download/13564c17-4e1e-493d-a330-dec0f42feaa7_pt.Search in Google Scholar

Falkenhain, M. (2020). Weak institutions and the governance dilemma: Gaps as traps. Springer Nature.10.1007/978-3-030-39742-5Search in Google Scholar

Garrett, G., & Lange, P. (1995). Internationalization, institutions, and political change. International Organization, 49, 627–655.10.1017/S0020818300028460Search in Google Scholar

Godwin, K., Ntayi, J., & Munene, J. (2021) Accountability and public interest in government institutions. International Journal of Public Administration, 44(2), 155–166. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2019.1672187.Search in Google Scholar

Goyer, M. (2011). Contingent capital: Short-term investors and the evolution of corporate governance in France and Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199578085.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hsu, G., Lin, Y., & Wei, Z. (2008). Competition policy for technological innovation in an era of knowledge-based economy. Knowledge-Based Systems, 21, 826–832.10.1016/j.knosys.2008.03.043Search in Google Scholar

Impact Task Force. (2021). Financing a better world requires impact transparency, integrity and harmonisation. https://www.impact-taskforce.com/media/io5ntb41/workstream-a-report.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Jang, Y. (2000). The worldwide founding of ministries of science and technology, 1950–1999. Sociological Perspectives, 43(2), 247–270.10.2307/1389796Search in Google Scholar

Jason, C., & Macnaghten, P. (2011). The Future of Science Governance: A review of public concerns, governance and institutional response. The BIS/Sciencewise-ERC ‘Science, Trust and Public Engagement’ project.Search in Google Scholar

Jung, D., Aguilera, R., & Goyer, M. (2015). Institutions and preferences in settings of causal complexity: foreign institutional investors and corporate restructuring practices in France. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(16), 2062–2086.10.1080/09585192.2014.971843Search in Google Scholar

Kanani, A., & Larizza, M. (2021). Institutions matter for growth and prosperity, today more than ever. World Bank. https://blogs.worldbank.org/governance/institutions-matter-growth-and-prosperity-today-more-ever.Search in Google Scholar

Kanbur, R. (2002). Economics, social science and development. World Development, 30, 477, 30, 591–608.486.10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00117-6Search in Google Scholar

Kenny, C. (2020). Transparency at Development Finance Institutions: Moving to better practice. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/transparency-development-finance-institutions-moving-better-practice.Search in Google Scholar

Knott, A. (2018). There’s no good alternative to investing in R&D. harvard business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/04/theres-no-good-alternative-to-investing-in-rd.Search in Google Scholar

Kwemarira, G., Munene, K. J. C., & Ntayi, J. M. (2020). Public interest in government institutions. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3926-1.Search in Google Scholar

Licht, G. (2015). What are the benefits of government investment in research and development? – “R&D expenditures are important drivers of economic development” in emerging economies (pp. 143–155). London: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Lungu, V. (2019). Knowledge-based society – a condition to ensure sustainable development. Eastern European Journal of Regional Studies, 5, 96–111.Search in Google Scholar

Marra, A., Mazzocchitti, M., & Sarra, A. (2018). Knowledge sharing and scientific cooperation in the design of research-based policies: The case of the circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 194, 800–812.10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.164Search in Google Scholar

McKelvey, M., Zaring, O., & Szücs, S. (2019). Conceptualizing evolutionary governance routines: Governance at the interface of science and technology with knowledge-intensive innovative entrepreneurship. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 30, 591–608. doi: 10.1007/s00191-018-0602-4.Search in Google Scholar

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2004). Science and Technology in Armenia: Toward a Knowledge-Based Economy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/11107.Search in Google Scholar

Nordström, M. (2022). AI under great uncertainty: Implications and decision strategies for public policy. AI & Society, 37, 1703–1714. doi: 10.1007/s00146-021-01263-4.Search in Google Scholar

North, D. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511808678.Search in Google Scholar

North, D. C., Wallis, J. J., & Weingast, B. R. (2009). Violence and social orders: A conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511575839.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. (1996). The knowledge-based economy. Paris: OECD.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. (2015). Frascati Manual 2015: Guidelines for Collecting and Reporting Data on Research and Experimental Development, The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/9789264239012-en.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. (2017). The role of national statistical systems in the data revolution. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/dcr-2017-8-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/dcr-2017-8-en.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. (2021). Evidence-based policy making and stakeholder engagement. OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021. https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/chapter-two-evidence-based-policy-making-and-stakeholder-engagement.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. (2022a). Digital Transformation of National Statistical Offices. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/ee4b1b85-en.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. (2022b). Transformative Agenda for STI Policy. https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/stpolicy2025/.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. (2023). Competition and Innovation: A Theoretical Perspective, OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note. www.oecd.org/daf/competition/competition-and-innovation-a-theoretical-perspective-2023.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Open Access Government. (2023). Japan: Science and Technology Policy. https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/japan-science-and-technology-policy/169693/.Search in Google Scholar

Pardo, C., Cotte, A., & Ronderos, N. (2019). An analysis for new institutionality in science, technology and innovation in Colombia using a structural vector autoregression model. European Research Studies Journal, XXII(2), 218–228.10.35808/ersj/1434Search in Google Scholar

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2000). Political economics: Explaining economic policy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Pohl, C. (2008). From science to policy through transdisciplinary research. Environmental Science & Policy. 11, 46e53. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2007.06.001.Search in Google Scholar

Pozenel, M. (2018). The importance of leadership skills in the scientific workforce. https://www.cas.org/blog/importance-leadership-skills-scientific-workforce.Search in Google Scholar

Reif, R. (2011). The contributions of Institutions such as MIT to a knowledge-based economy. https://web.mit.edu/fnl/volume/234/reif.html.Search in Google Scholar

Ricyt. (2018). El estado de la ciencia. www.ricyt.org.Search in Google Scholar

Schot, J., & Steinmueller, W. (2018). Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy, 47(9), 1554–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011.Search in Google Scholar

Shan, Y. (2019). Incentives for research agents and performance-vested equity-based compensation. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 102, 44–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jedc.2019.02.007.Search in Google Scholar

Shepsle, K. A. (2010). The rules of the game: What rules? Which game?. In Prepared for the Conference on the Legacy and Work of Douglass C. North, St. Louis. November 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Tharanga, S. (2019). The relationship between institutions and economic development. MPRA Paper No. 97755. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/97755/1/MPRA_paper_97755.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Thorhauge, A. M. (2013). The rules of the game – The rules of the player. Games and Culture, 8(6), 371–391.10.1177/1555412013493497Search in Google Scholar

UNCTAD. (2019). A framework for science, technology and innovation policy reviews. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/dtlstict2019d4_en.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

UNIDO. (2021). The role of science, technology, and innovation policies in the industrialization of developing countries. https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/files/2022-03/STI_Policies.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Heijden, M. (2023). Problematizing partner selection: Collaborative choices and decision-making uncertainty. Public Policy and Administration, 38(4), 466–491. doi: 10.1177/09520767221088269.Search in Google Scholar

Wall, F. (2019). Emergence of coordination in growing decision-making organizations: The role of complexity, search strategy, and cost of effort. Complexity, 2019, Article ID 4398620, 26. doi: 10.1155/2019/4398620.Search in Google Scholar

Zaman, G., & Goschin, Z. (2010). Technical change as exogenous or endogenous factor in the production function models: Empirical evidence from Romania. Journal for Economic Forecasting, 2, 29–45.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Political Turnover and Public Health Provision in Brazilian Municipalities

- Examining the Effects of Trade Liberalisation Using a Gravity Model Approach

- Operating Efficiency in the Capital-Intensive Semiconductor Industry: A Nonparametric Frontier Approach

- Does Health Insurance Boost Subjective Well-being? Examining the Link in China through a National Survey

- An Intelligent Approach for Predicting Stock Market Movements in Emerging Markets Using Optimized Technical Indicators and Neural Networks

- Analysis of the Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion in Promoting Inclusive Growth: Mechanism and Statistical Verification

- Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size under Turnover Tax: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on SMEs

- Re-investigating the Impact of Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development, Institutional Quality, and Globalization on Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries

- A Compliance Return Method to Evaluate Different Approaches to Implementing Regulations: The Example of Food Hygiene Standards

- Panel Technical Efficiency of Korean Companies in the Energy Sector based on Digital Capabilities

- Time-varying Investment Dynamics in the USA

- Preferences, Institutions, and Policy Makers: The Case of the New Institutionalization of Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance in Colombia

- The Impact of Geographic Factors on Credit Risk: A Study of Chinese Commercial Banks

- The Heterogeneous Effect and Transmission Paths of Air Pollution on Housing Prices: Evidence from 30 Large- and Medium-Sized Cities in China

- Analysis of Demographic Variables Affecting Digital Citizenship in Turkey

- Green Finance, Environmental Regulations, and Green Technologies in China: Implications for Achieving Green Economic Recovery

- Coupled and Coordinated Development of Economic Growth and Green Sustainability in a Manufacturing Enterprise under the Context of Dual Carbon Goals: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality

- Revealing the New Nexus in Urban Unemployment Dynamics: The Relationship between Institutional Variables and Long-Term Unemployment in Colombia

- The Roles of the Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate in the Current Account Balance

- Cleaner Production: Analysis of the Role and Path of Green Finance in Controlling Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

- The Research on the Impact of Regional Trade Network Relationships on Value Chain Resilience in China’s Service Industry

- Social Support and Suicidal Ideation among Children of Cross-Border Married Couples

- Asymmetrical Monetary Relations and Involuntary Unemployment in a General Equilibrium Model

- Job Crafting among Airport Security: The Role of Organizational Support, Work Engagement and Social Courage

- Does the Adjustment of Industrial Structure Restrain the Income Gap between Urban and Rural Areas

- Optimizing Emergency Logistics Centre Locations: A Multi-Objective Robust Model

- Geopolitical Risks and Stock Market Volatility in the SAARC Region

- Trade Globalization, Overseas Investment, and Tax Revenue Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Can Government Expenditure Improve the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service? – Take Wuhan as an Example

- Media Tone and Earnings Management before the Earnings Announcement: Evidence from China

- Review Articles

- Economic Growth in the Age of Ubiquitous Threats: How Global Risks are Reshaping Growth Theory

- Efficiency Measurement in Healthcare: The Foundations, Variables, and Models – A Narrative Literature Review

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm

- Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy

- Special Issue: Economic Implications of Management and Entrepreneurship - Part II

- Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study on Entrepreneurial Tendency of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA in the Context of the Interactive Model

- Bridging Brand Parity with Insights Regarding Consumer Behavior

- The Effect of Green Human Resources Management Practices on Corporate Sustainability from the Perspective of Employees

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation in Economics and Management Decision - Part II

- High-Quality Development of Sports Competition Performance Industry in Chengdu-Chongqing Region Based on Performance Evaluation Theory

- Analysis of Multi-Factor Dynamic Coupling and Government Intervention Level for Urbanization in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt

- The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Technological Innovation of Enterprises: Based on Empirical Evidences of the Implementation of Pollution Charges in China

- Environmental Social Responsibility, Local Environmental Protection Strategy, and Corporate Financial Performance – Empirical Evidence from Heavy Pollution Industry

- The Relationship Between Stock Performance and Money Supply Based on VAR Model in the Context of E-commerce

- A Novel Approach for the Assessment of Logistics Performance Index of EU Countries

- The Decision Behaviour Evaluation of Interrelationships among Personality, Transformational Leadership, Leadership Self-Efficacy, and Commitment for E-Commerce Administrative Managers

- Role of Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurship Across the Diverse Economic Stages: Insights from GEM and GLOBE Data

- Performance Evaluation of Economic Relocation Effect for Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations: Evidence from China

- Functional Analysis of English Carriers and Related Resources of Cultural Communication in Internet Media

- The Influences of Multi-Level Environmental Regulations on Firm Performance in China

- Exploring the Ethnic Cultural Integration Path of Immigrant Communities Based on Ethnic Inter-Embedding

- Analysis of a New Model of Economic Growth in Renewable Energy for Green Computing

- An Empirical Examination of Aging’s Ramifications on Large-scale Agriculture: China’s Perspective

- The Impact of Firm Digital Transformation on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: Evidence from China

- Accounting Comparability and Labor Productivity: Evidence from China’s A-Share Listed Firms

- An Empirical Study on the Impact of Tariff Reduction on China’s Textile Industry under the Background of RCEP

- Top Executives’ Overseas Background on Corporate Green Innovation Output: The Mediating Role of Risk Preference

- Neutrosophic Inventory Management: A Cost-Effective Approach

- Mechanism Analysis and Response of Digital Financial Inclusion to Labor Economy based on ANN and Contribution Analysis

- Asset Pricing and Portfolio Investment Management Using Machine Learning: Research Trend Analysis Using Scientometrics

- User-centric Smart City Services for People with Disabilities and the Elderly: A UN SDG Framework Approach

- Research on the Problems and Institutional Optimization Strategies of Rural Collective Economic Organization Governance

- The Impact of the Global Minimum Tax Reform on China and Its Countermeasures

- Sustainable Development of Low-Carbon Supply Chain Economy based on the Internet of Things and Environmental Responsibility

- Measurement of Higher Education Competitiveness Level and Regional Disparities in China from the Perspective of Sustainable Development

- Payment Clearing and Regional Economy Development Based on Panel Data of Sichuan Province

- Coordinated Regional Economic Development: A Study of the Relationship Between Regional Policies and Business Performance

- A Novel Perspective on Prioritizing Investment Projects under Future Uncertainty: Integrating Robustness Analysis with the Net Present Value Model

- Research on Measurement of Manufacturing Industry Chain Resilience Based on Index Contribution Model Driven by Digital Economy

- Special Issue: AEEFI 2023

- Portfolio Allocation, Risk Aversion, and Digital Literacy Among the European Elderly

- Exploring the Heterogeneous Impact of Trade Agreements on Trade: Depth Matters

- Import, Productivity, and Export Performances

- Government Expenditure, Education, and Productivity in the European Union: Effects on Economic Growth

- Replication Study

- Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: A Replication of Andersson (American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2019)

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Political Turnover and Public Health Provision in Brazilian Municipalities

- Examining the Effects of Trade Liberalisation Using a Gravity Model Approach

- Operating Efficiency in the Capital-Intensive Semiconductor Industry: A Nonparametric Frontier Approach

- Does Health Insurance Boost Subjective Well-being? Examining the Link in China through a National Survey

- An Intelligent Approach for Predicting Stock Market Movements in Emerging Markets Using Optimized Technical Indicators and Neural Networks

- Analysis of the Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion in Promoting Inclusive Growth: Mechanism and Statistical Verification

- Effective Tax Rates and Firm Size under Turnover Tax: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on SMEs

- Re-investigating the Impact of Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development, Institutional Quality, and Globalization on Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries

- A Compliance Return Method to Evaluate Different Approaches to Implementing Regulations: The Example of Food Hygiene Standards

- Panel Technical Efficiency of Korean Companies in the Energy Sector based on Digital Capabilities

- Time-varying Investment Dynamics in the USA

- Preferences, Institutions, and Policy Makers: The Case of the New Institutionalization of Science, Technology, and Innovation Governance in Colombia

- The Impact of Geographic Factors on Credit Risk: A Study of Chinese Commercial Banks

- The Heterogeneous Effect and Transmission Paths of Air Pollution on Housing Prices: Evidence from 30 Large- and Medium-Sized Cities in China

- Analysis of Demographic Variables Affecting Digital Citizenship in Turkey

- Green Finance, Environmental Regulations, and Green Technologies in China: Implications for Achieving Green Economic Recovery

- Coupled and Coordinated Development of Economic Growth and Green Sustainability in a Manufacturing Enterprise under the Context of Dual Carbon Goals: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality

- Revealing the New Nexus in Urban Unemployment Dynamics: The Relationship between Institutional Variables and Long-Term Unemployment in Colombia

- The Roles of the Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate in the Current Account Balance

- Cleaner Production: Analysis of the Role and Path of Green Finance in Controlling Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution

- The Research on the Impact of Regional Trade Network Relationships on Value Chain Resilience in China’s Service Industry

- Social Support and Suicidal Ideation among Children of Cross-Border Married Couples

- Asymmetrical Monetary Relations and Involuntary Unemployment in a General Equilibrium Model

- Job Crafting among Airport Security: The Role of Organizational Support, Work Engagement and Social Courage

- Does the Adjustment of Industrial Structure Restrain the Income Gap between Urban and Rural Areas

- Optimizing Emergency Logistics Centre Locations: A Multi-Objective Robust Model

- Geopolitical Risks and Stock Market Volatility in the SAARC Region

- Trade Globalization, Overseas Investment, and Tax Revenue Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Can Government Expenditure Improve the Efficiency of Institutional Elderly-Care Service? – Take Wuhan as an Example

- Media Tone and Earnings Management before the Earnings Announcement: Evidence from China

- Review Articles

- Economic Growth in the Age of Ubiquitous Threats: How Global Risks are Reshaping Growth Theory

- Efficiency Measurement in Healthcare: The Foundations, Variables, and Models – A Narrative Literature Review

- Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm

- Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy

- Special Issue: Economic Implications of Management and Entrepreneurship - Part II

- Ethnic Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study on Entrepreneurial Tendency of Meskhetian Turks Living in the USA in the Context of the Interactive Model

- Bridging Brand Parity with Insights Regarding Consumer Behavior

- The Effect of Green Human Resources Management Practices on Corporate Sustainability from the Perspective of Employees

- Special Issue: Shapes of Performance Evaluation in Economics and Management Decision - Part II

- High-Quality Development of Sports Competition Performance Industry in Chengdu-Chongqing Region Based on Performance Evaluation Theory

- Analysis of Multi-Factor Dynamic Coupling and Government Intervention Level for Urbanization in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt

- The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Technological Innovation of Enterprises: Based on Empirical Evidences of the Implementation of Pollution Charges in China

- Environmental Social Responsibility, Local Environmental Protection Strategy, and Corporate Financial Performance – Empirical Evidence from Heavy Pollution Industry

- The Relationship Between Stock Performance and Money Supply Based on VAR Model in the Context of E-commerce

- A Novel Approach for the Assessment of Logistics Performance Index of EU Countries

- The Decision Behaviour Evaluation of Interrelationships among Personality, Transformational Leadership, Leadership Self-Efficacy, and Commitment for E-Commerce Administrative Managers

- Role of Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurship Across the Diverse Economic Stages: Insights from GEM and GLOBE Data

- Performance Evaluation of Economic Relocation Effect for Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations: Evidence from China

- Functional Analysis of English Carriers and Related Resources of Cultural Communication in Internet Media

- The Influences of Multi-Level Environmental Regulations on Firm Performance in China

- Exploring the Ethnic Cultural Integration Path of Immigrant Communities Based on Ethnic Inter-Embedding

- Analysis of a New Model of Economic Growth in Renewable Energy for Green Computing

- An Empirical Examination of Aging’s Ramifications on Large-scale Agriculture: China’s Perspective

- The Impact of Firm Digital Transformation on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: Evidence from China

- Accounting Comparability and Labor Productivity: Evidence from China’s A-Share Listed Firms

- An Empirical Study on the Impact of Tariff Reduction on China’s Textile Industry under the Background of RCEP

- Top Executives’ Overseas Background on Corporate Green Innovation Output: The Mediating Role of Risk Preference

- Neutrosophic Inventory Management: A Cost-Effective Approach

- Mechanism Analysis and Response of Digital Financial Inclusion to Labor Economy based on ANN and Contribution Analysis

- Asset Pricing and Portfolio Investment Management Using Machine Learning: Research Trend Analysis Using Scientometrics

- User-centric Smart City Services for People with Disabilities and the Elderly: A UN SDG Framework Approach

- Research on the Problems and Institutional Optimization Strategies of Rural Collective Economic Organization Governance

- The Impact of the Global Minimum Tax Reform on China and Its Countermeasures

- Sustainable Development of Low-Carbon Supply Chain Economy based on the Internet of Things and Environmental Responsibility

- Measurement of Higher Education Competitiveness Level and Regional Disparities in China from the Perspective of Sustainable Development

- Payment Clearing and Regional Economy Development Based on Panel Data of Sichuan Province

- Coordinated Regional Economic Development: A Study of the Relationship Between Regional Policies and Business Performance

- A Novel Perspective on Prioritizing Investment Projects under Future Uncertainty: Integrating Robustness Analysis with the Net Present Value Model

- Research on Measurement of Manufacturing Industry Chain Resilience Based on Index Contribution Model Driven by Digital Economy

- Special Issue: AEEFI 2023

- Portfolio Allocation, Risk Aversion, and Digital Literacy Among the European Elderly

- Exploring the Heterogeneous Impact of Trade Agreements on Trade: Depth Matters

- Import, Productivity, and Export Performances

- Government Expenditure, Education, and Productivity in the European Union: Effects on Economic Growth

- Replication Study

- Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: A Replication of Andersson (American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2019)