Toxicity of bisphenol A and p-nitrophenol on tomato plants: Morpho-physiological, ionomic profile, and antioxidants/defense-related gene expression studies

-

Mahmoud S. Abdelmoneim

, Sherif F. Hammad

Abstract

Bisphenol A (BPA) and p-nitrophenol (PNP) are emerging contaminants of soils due to their wide presence in agricultural and industrial products. Thus, the present study aimed to integrate morpho-physiological, ionic homeostasis, and defense- and antioxidant-related genes in the response of tomato plants to BPA or PNP stress, an area of research that has been scarcely studied. In this work, increasing the levels of BPA and PNP in the soil intensified their drastic effects on the biomass and photosynthetic pigments of tomato plants. Moreover, BPA and PNP induced osmotic stress on tomato plants by reducing soluble sugars and soluble proteins relative to control. The soil contamination with BPA and PNP treatments caused a decline in the levels of macro- and micro-elements in the foliar tissues of tomatoes while simultaneously increasing the contents of non-essential micronutrients. The Fourier transform infrared analysis of the active components in tomato leaves revealed that BPA influenced the presence of certain functional groups, resulting in the absence of some functional groups, while on PNP treatment, there was a shift observed in certain functional groups compared to the control. At the molecular level, BPA and PNP induced an increase in the gene expression of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase, with the exception of POD gene expression under BPA stress. The expression of the thaumatin-like protein gene increased at the highest level of PNP and a moderate level of BPA without any significant effect of both pollutants on the expression of the tubulin (TUB) gene. The comprehensive analysis of biochemical responses in tomato plants subjected to BPA and PNP stress illustrates valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying tolerance to these pollutants.

Introduction

Recently, aromatic organic pollutants have gained significant importance due to their wide applications in various industrial sectors, such as metallurgy, plastics manufacturing, paper production, explosives development, coking processes, oil refining, textile manufacturing, synthetic ammonia production, resin synthesis, pesticide formulation, pharmaceutical production, and other related fields [1]. Aromatic organic pollutants may reach the environment through the effluents of industrial wastewater, resulting in detrimental effects on human health, plants, the diversity of the rhizosphere microbial community, and the natural environment due to their toxicity, persistence, and bioaccumulation characteristics [2]. Plasticizers, such as phthalate esters and bisphenol A (BPA), are persistent organic pollutants (POPs) that exhibit high stability [3]. BPA, chemically known as 2,2-bis (4-hydroxyphenyl) propane, is an anthropogenic environmental pollutant ubiquitously present in a diverse range of commercial products [4]. BPA-containing items have increased across Africa as the continent’s industrial processes and food packaging have expanded, leading to higher levels of bioaccumulation and human exposure [5] with endocrine-disrupting properties [6]. The worldwide production and utilization of BPA have exhibited a steady upward trend of 6.2 million tons (MT) in the year 2020, and it will further increase to approximately 7.1 MT by the year 2027 [7]. BPA reaches the soil environment through sewage, effluent, and the use of biosolids as soil amendments [8]. According to Yamamoto et al., the content of BPA in landfill leachate derived from hazardous waste in Japan has been detected to be 17.2 mg L−1 [9].

The low volatility of BPA causes its half-life in water and soil to be approximately 4.5 days, whereas in the air, it is less than 1 day [10]. Due to the short lifetime of BPA, it is not technically classified as a POP, but it is often added to other POPs, given its ubiquitous presence in the environment. The European Food Safety Authority’s specialists have determined the tolerable daily intake of BPA in humans to be 0.2 ng per kilogram of body biomass per day [11]. It has been reported that BPA can accumulate in the human body through the interconnected processes of the soil–plant–animal food chain [3]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to study the effects of BPA on plants, which are important members of the food chain. Plants serve as valuable indicators for assessing the ecological and environmental risks associated with BPA. Several studies on the toxic impact of BPA have indicated that the application of BPA at a concentration of >10 mg L−1 adversely affects the growth of plants in a dose-dependent manner. The toxic effects of BPA have been recorded on various root traits, including reduction in length, biomass, sparse lateral roots, the synthesis of gelatinous compounds, and blackened necrosis in local roots [12]. Also, BPA adversely impacts the biochemical processes in roots, including the uptake of nitrogen and other nutrients, hormonal homeostasis, the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and the antioxidant systems [13,14,15,16]. However, the impacts of BPA on biochemical, ionic, and gene expression levels have not been well studied.

Another organic pollutant, p-nitrophenol (PNP), is an exotic nitroaromatic molecule found ubiquitously in agricultural soils [17] and a hazardous environmental pollutant to soil microbiota [18]. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, PNP is a priority pollutant due to its mutagenesis potential, acute toxicity, and long-term consequences for humans and the environment [19]. Thus, PNPs are classified as persistent pollutants and pose a significant risk to human health due to their potential to cause cancer [20] because PNP acts as an endocrine disruptor [21]. The US Environmental Protection Agency classified PNP and its derivatives as priority pollutants in 1987, and they were ordered to limit their concentration in water to 10 μg/L [22,23]. However, PNP, at concentrations ranging from 0.8 to 30.5 µg g−1, has been detected in agricultural soils worldwide, but mainly in developing nations, owing to industrial discharges and pesticide degradation [24]. In addition, PNP has been documented as a chemical precursor for synthesizing of various drugs, dyes, herbicides, fungicides, and other products [25]. In this regard, PNP can leach into soil through the decomposition of methyl parathion, an organophosphorus pesticide widely used in agriculture [26]. Nitroaromatic chemicals eventually come into contact with plant root systems as a result of air deposition through precipitation and possible soil accumulation. Their accumulation in plant tissues such as roots, leaves, and stems has been demonstrated [27]. Sun et al. reported that nitrophenol at a low concentration (5 mg L−1) had no significant effect on the biomass or photosynthetic physiological response of Salix babylonica compared to the control plant; however, nitrophenol at higher concentrations caused toxicity by decreasing various important parameters, including biomass, actual photochemical efficiency (PSII), net photosynthetic rate, photochemical quenching coefficient, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, and chlorophyll content [28]. The recognized phytotoxicity of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene and its derivatives as nitroaromatic pollutants is already well established [29]; however, the toxicity of nitrophenols on plants is scarcely studied. Adamek et al. in a more recent study, documented the harmful effects of nitro-aromatic compounds (guaiacol and 4-nitroguaiacol) on sunflower and maize grown in a hydroponic system inside a controlled growth chamber [30]. Although nitrophenols have been widely recognized as harmful to different aquatic and terrestrial organisms, we could not find any literature assessing their tolerance limits for plants. Therefore, it is essential to uncover the toxicity of PNP on the leaf tissue of tomato plants, particularly focusing on gene expression and ionic homeostasis.

The tomato plant (Solanum lycopersicum L., Solanales: Solanaceae) is the primary vegetable crop cultivated in Egypt, encompassing around 3% of the country’s overall cultivated land [31]. Egypt is the fifth-largest tomato grower worldwide, following China, India, the United States, and Turkey [32]. Tomato plants, during their life cycle, are exposed to various common and emergent pollutants that could affect their whole life cycle, especially during transplanting to contaminated soil. Consequently, the objectives of this study were to (i) examine the impact of bisphenol and PNP on vegetative growth (biomass), osmoprotectants, and ionic homeostasis; (ii) study the bioactive characteristics of leaves under both pollutants by detecting the main functional groups in plants by Fourier transmission infrared spectroscopy (FTIR); and (iii) illustrate the expression of genes related to antioxidant defense and expression patterns of tubulin (TUB) and thaumatin-like proteins (TLPs) genes in tomatoes in the presence of PNP and BPA.

Material and methods

Soil contamination and pot preparations

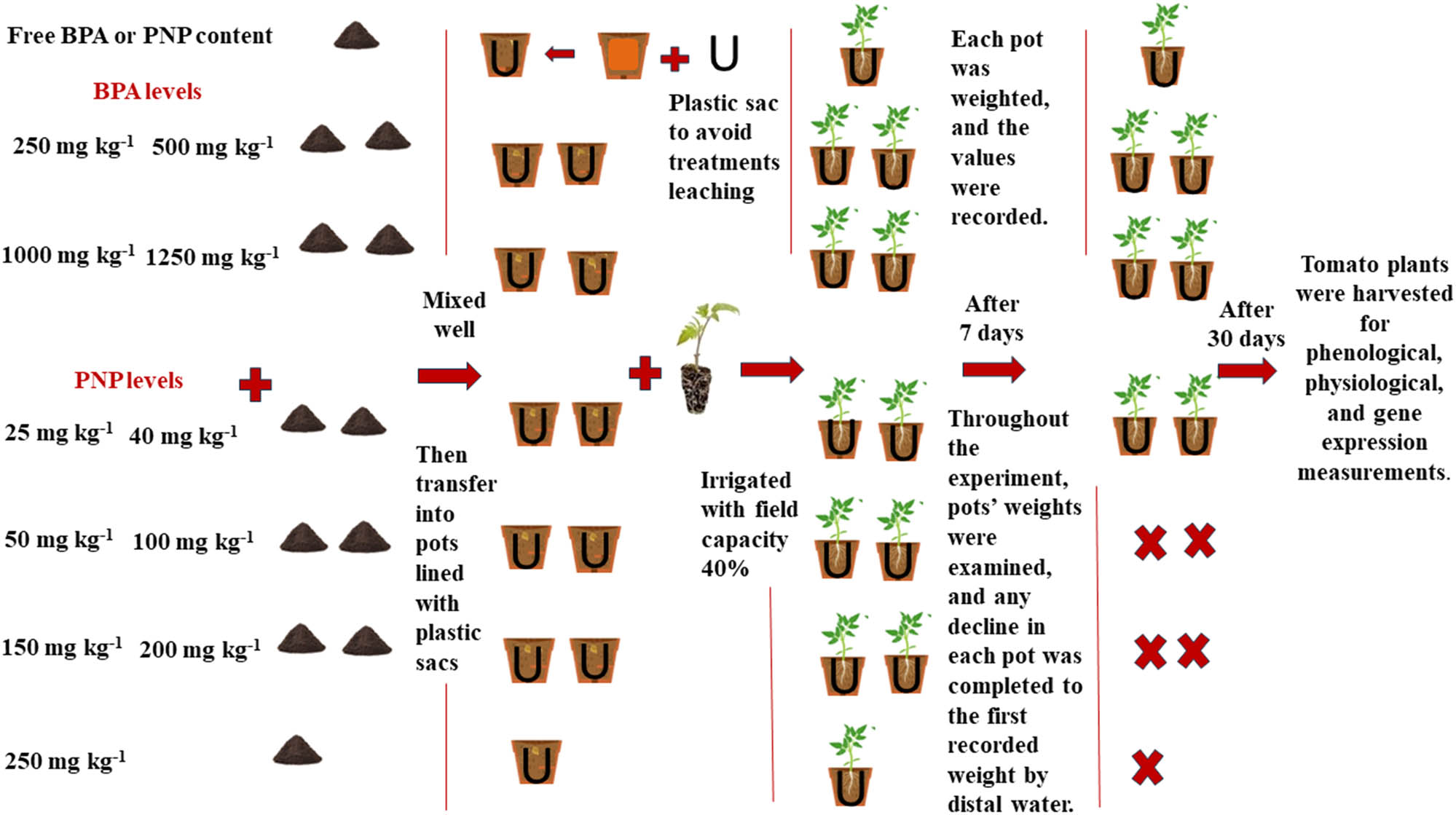

A pot experiment was conducted in 2022 at the City of Scientific Research and Technological Application (SRTA-City), located in New Borg El-Arab City, Alexandria, Egypt, under natural conditions of temperature, humidity, and light. The pots were lined with a plastic sac and filled with 1 kg of soil (physical and chemical characteristics of soils are described in Table 1). A week before tomato transplanting, the calculated amounts of BPA at 250, 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1, as well as seven levels of PNP at 25, 40, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 mg kg−1 were dissolved in acetone and then mixed thoroughly with soil particles to ensure their interaction with the soil particles and evaporation of acetone (Figure 1). The levels of BPA and PNP were selected based on previous studies [4,8,28,33].

The pH value, total soluble salts (TSS, %), organic matter content (OM, mg g−1 dry soil), the contents of Na, Ca, Mg, Cl,

| pH | TSS | OM | Na | K | Ca | Mg | Cl |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.12 ± 0.05 | 0.77 ± 0.16 | 7.83 ± 0.07 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 4.47 ± 0.10 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 2.24 ± 0.12 |

The value of each trait is the mean ± SE.

Schematic representation of soil preparation and experimental design.

Plant materials and experimental setup

The current study used tomato seeds (hybrid T-186) purchased from Technogreen Company for Agricultural Projects, Cairo, Egypt. The company imported the seeds from China. The seeds were germinated in Bitmos soil for 45 days (seedling stage). The uniform seedlings (45 days) were then transplanted into the previously prepared experimental pots (three seedlings/pots). The pots were kept in the greenhouse of New Borg El-Arab City under the natural conditions of light, temperature, and humidity (Table 2). Five pots were prepared per treatment. The soil water content was maintained around the field capacity throughout the experimental period. Tomato seedlings were kept under these conditions for 30 days before being harvested for phenological, physiological, and gene expression measurements (Figure 1).

Monthly change of temperature, humidity, and pressure in the greenhouse of New Borg El-Arab City, Alexandrina, Egypt, during April and May 2022

| Month | Temperature (°C) | Humidity (%) | Pressure (mbar) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April | High | 41 | 100 | 1,019 |

| Low | 11 | 6 | 999 | |

| Average | 19 | 64 | 1,013 | |

| May | High | 35 | 100 | 1,020 |

| Low | 13 | 21 | 1,003 | |

| Average | 21 | 68 | 1,014 |

Growth parameters

At harvest, roots and shoots were separated, rinsed with distilled water to remove any debris on the surface, and dried on absorbent paper. Fresh biomass of shoots and roots was immediately recorded using an electronic balance. The fresh samples were then placed in an aerated oven for 48 h at 70°C to determine their dry biomass.

Determination of photosynthetic pigments

The pigment fractions (chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), and total carotenoids (TC)) were estimated using the spectrophotometric method suggested by Lichtenthaler [34]. Briefly, fresh tomato leaves were suspended in test tubes with screw caps containing 10 ml of 60% ethanol and heated in a water bath at 70°C until decolonization. The absorbance was determined at 452, 644, and 663 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (EMC-NANO-UV, Germany). The content of photosynthetic pigments was determined according to the following equations:

Determination of osmolyte content

The fresh tomato leaves were ground using liquid nitrogen and then homogenized in a potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.8 for osmolyte estimation. Soluble carbohydrates (SC) were quantified using the anthrone sulphuric acid method [35,36]. Leaf extract (ml) was mixed with the anthrone reagent, boiled in a water bath for 7 min, and cooled, and the absorbance of the developed color was monitored at 620 nm. Soluble proteins (SP) were determined according to the method of Lowery et al. [37]. Lowery C was added to the leaf extract and left for 10 min; diluted Foiln reagent (1:2 v/v) was added and mixed well, and then the absorbance of the blue color was determined at 750 nm after 30 min. Free amino acids were analyzed by ninhydrin assay [38]. Stannus chloride reagent was added to the plant extract, which was boiled in a water bath for 20 min. The diluent reagent was then added and mixed well, and the absorbance of the developed purple color was recorded at 570 nm.

FTIR of leaf contents of tomatoes

Using a Nicolet iS10 (Thermo Scientific, USA) with a 1 cm−1 resolution and a range of 500–4,000 cm−1, the FTIR spectra of dry-grinded tomato leaves were recorded using the KBr–Wafer method [39].

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis of leaf contents of tomatoes

The oven-dried tomato leaves were finely ground using a pestle, followed by a protocol for analyzing the material powder with helium gas. The minerals such as Na, K, Ca, Mg, Zn, Cu, Ni, Fe, Mn, Al, Si, P, Ti, V, Cr, Co, Sc, and Zr were estimated using XRF (Rigaku NEX CG EDXRF, USA-Japan). The analysis was done using the energy-dispersive technique with a multi-element filter and using Rigaku MCA Standards to determine the content of atomic elements by mass percentage unit [40]. The mass percentage refers to the percent of each element of the estimated elements.

Relative gene expression of peroxidase (POD), polyphenol oxidase (PPO), thaumatin, and TUB using quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Extraction of RNA and synthesis of complementary DNA (Cdna) from tomato plants

The TRIzole LS Reagent reagent was utilized to extract total RNA from 100 mg of tomato leaves [41]. The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA were determined using the A260/A280 ratio and a Nanodrop (model 2000c; Thermo Scientific, USA). One microgram of DNase-I-treated RNA was used as a template for reverse transcription to produce 1 mg of cDNA from each sample. The primers of oligo (dT) and random hexamer types were used in the reaction method. Abdelkhalek et al. implemented the reaction conditions and components [42]. The final cDNA was stored at −20°C until it was used as a template in qRT-PCR.

Expression of tomato defense genes

qRT-PCR was used to measure the transcript levels of four tomato genes (POD, PPO, thumatin-like proteins, and TUB) and β-actin for all treatments. Table 3 displays the nucleotide sequences of the primers used. The expression levels of the PPO, POD, TUB, and TLP tomato genes were adjusted using the β-actin gene as a standard. The expression of β-actin was evaluated during all forms of treatment, and no significant changes were detected. Each biological treatment’s qPCR reactions were conducted separately using an SYBR Green Mix (Thermo Fisher, CA, USA) and a Rotor-Gene 6000 real-time thermocycler (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA). The methodology employed for the PCR conditions was conducted as described in a prior study [43]. Using the 2−∆∆CT method, the relative expression levels for each studied gene were estimated [44].

Nucleotide sequences of the primers used in this study

| Primer and gene name | Abbreviation | Direction | Nucleotide sequence 5′–3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| POD | POD | Forward | GCTTTGTCAGGGGTTGTG AT |

| Reverse | TGCATCTCTAGCAACCAA CG | ||

| PPO | PPO | Forward | CATGCTCTTGATGAGGC GTA |

| Reverse | CCATCTATGGAACGGGAAGA | ||

| TLPs | TLPs | Forward | CATGTCCTCCCACAGAGTAC |

| Reverse | ATATAATCCCATTTCGTGCTTATG | ||

| TUB | TUB | Forward | AGGATGCTACAGCCGATGAG |

| Reverse | GCCGAAGAACTGACGAGAATC | ||

| β-actin | β-actin | Forward | TGGCATACAAAGACAGGACAGCCT |

| Reverse | ACTCAATCCCAAGGCCAACAGAGA |

Statistical analyses

The pots were arranged in a completely random design on the ground of the green hose of the city of scientific research and technological applications under the natural conditions of New Borg El-Arab City, Alexandrina, Egypt. Using SPSS 21 software, all data were statistically analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. Tukey’s honest significant differences at a probability value (p ≤ 0.05) were applied to the obtained data, where three biological replicates were used per treatment, and the letter “a” refers to the lowest mean. A heatmap was plotted using the “pheatmap” function, and correlation analysis was carried out using Corrplot in R Project v.3.6.3.

Experimental results

The phyto-impact of PNP or BPA on the growth parameters of tomato plants

Various concentrations of BPA substantially impacted the fresh and dry biomass of shoots and roots. As illustrated in Table 4, BPA gradually decreased the shoot fresh biomass (SFB) by 14, 67, 73, 79, and 82%, as well as root fresh biomass (RFB) by 57, 70, 77, 78, and 85%, relative to control when applied at the levels of 250, 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1, respectively. Also, the dry biomasses of shoot and root were significantly reduced by BPA, with the percent reduction being 32, 41, 41, 67, and 56% for SDB, and 50, 49, 53, 53 for RDB, and 56% for RDW, at 250, 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1, respectively. On the other hand, PNP exhibited its lethal impact on tomato plants, causing wilting within 3 days of exposure to levels of 150, 200, and 250 mg kg−1, ultimately resulting in plant death. Thus, we have the results of two levels: 25 and 40 mg kg−1 of PNP. In this sense, Table 5 shows that the tomato fresh biomass significantly reduced by 22 and 38% for SFB and 28 and 35% for RFB at 25 and 40 mg PNP kg−1 soil, respectively, relative to control plants. The drastic impact of PNP was significantly exhibited on the dry biomass of tomato plants, where the percent reductions of SDB at 25 and 40 mg kg−1 were 44 and 62%, while those of RDB were 10 and 48%, respectively.

The fresh and dry biomasses of shoots and roots of tomato plants grown at different levels of BPA (0, 250, 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1)

| Bisphenol levels (mg kg−1) | Biomass | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFB | RFB | SDB | RDB | |

| 0 | 5.50c ± 0.17 | 3.00c ± 0.16 | 0.93b ± 0.15 | 0.30b ± 0.03 |

| 250 | 4.75b ± 0.32 | 1.30b ± 0.17 | 0.64ab ± 0.02 | 0.15a ± 0.03 |

| 500 | 1.81a ± 0.38 | 0.90a ± 0.03 | 0.55a ± 0.09 | 0.15a ± 0.01 |

| 750 | 1.47a ± 0.12 | 0.7a ± 0.06 | 0.55a ± 0.03 | 0.14a ± 0.01 |

| 1,000 | 1.13a ± 0.08 | 0.65a ± 0.09 | 0.41a ± 0.02 | 0.14a ± 0.01 |

| 1,250 | 0.97a ± 0.12 | 0.45a ± 0.03 | 0.31a ± 0.01 | 0.13a ± 0.01 |

| F value | 96.66** | 92.78** | 9.09** | 14.78** |

SFB = shoot fresh biomass; RFB = root fresh biomass; SDB = shoot dry biomass; RDB = root dry biomass. The value of each trait is the mean ± SE. Mean values with different letters are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Tukey’s test. * and ** significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 confidence levels.

The fresh and dry biomasses of shoots and roots of tomato plants grown at three levels of PNP (0, 25, and 40 mg kg−1)

| PNP levels mg kg−1 | Biomass | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFB | RFB | SDB | RDB | |

| 0 | 5.40b ± 0.11 | 4.00b ± 0.12 | 1.15c ± 0.01 | 0.50b ± 0.01 |

| 25 | 4.20a ± 0.06 | 2.90a ± 0.15 | 0.64b ± 0.03 | 0.46b ± 0.02 |

| 40 | 3.35a ± 0.32 | 2.60a ± 0.06 | 0.43a ± 0.03 | 0.26a ± 0.02 |

| F value | 27.09** | 40.75** | 232.25** | 49.60** |

SFB = shoot fresh biomass; RFB = root fresh biomass; SDB = shoot dry biomass; RDB = root fresh biomass. The value of each trait is the mean ± SE. Mean values with different letters are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Tukey’s test. * and ** significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 confidence levels.

The phyto-impact of PNP or BPA on photosynthetic pigments of tomato plants

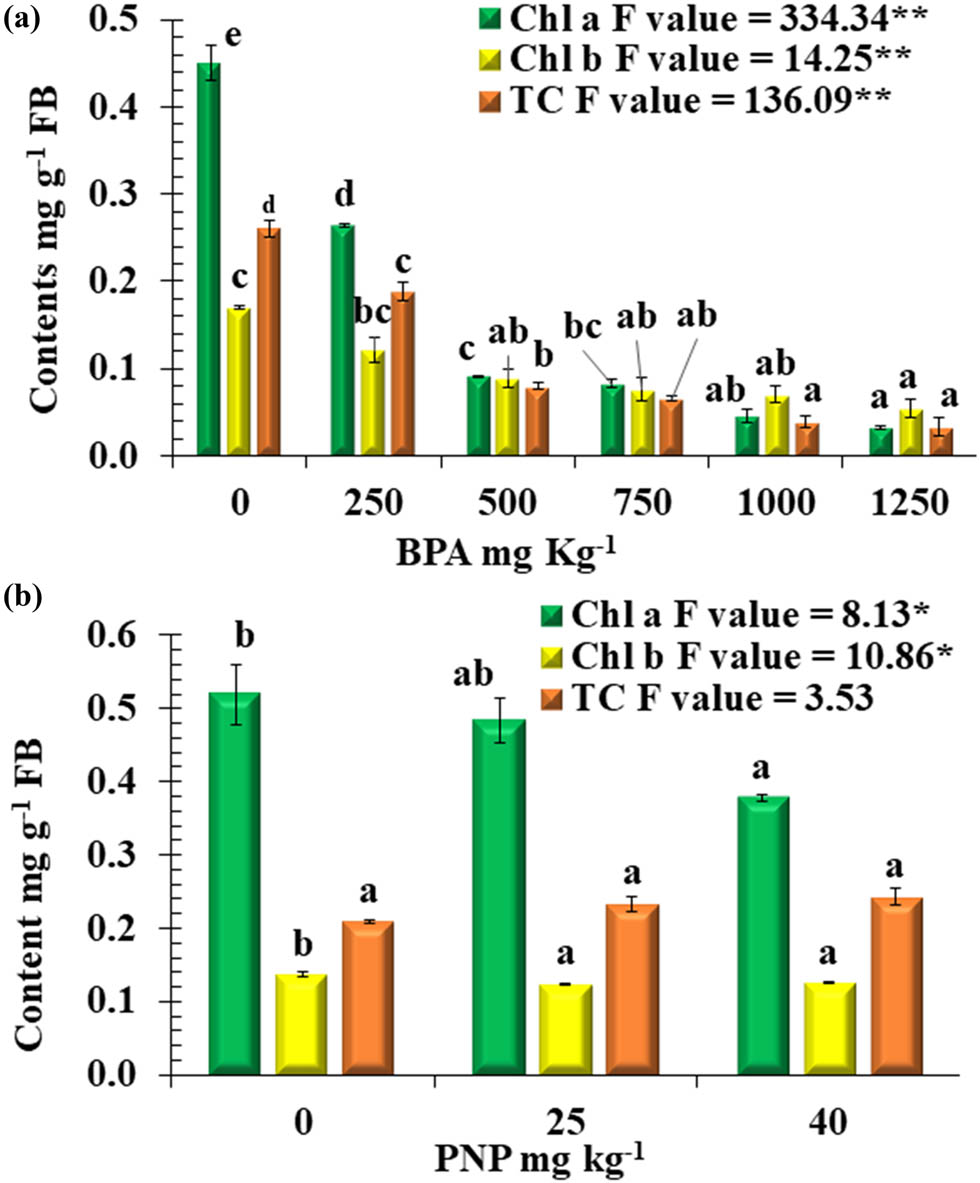

The photosynthetic pigments are highly affected by PNP or BPA. BPA was responsible for a significant drop in the values of chl a with decreased percentages of 41, 80, 82, 90, and 93% at 250, 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1, respectively, when compared to non-contaminated soil (Figure 2a). On the other hand, PNP also decreased chl a as the concentration of PNP increased, with decreases of 10 and 27% observed at 25 and 40 mg kg−1, respectively, in comparison to the non-contaminated soil (Figure 1b).

Photosynthetic pigments Chl a, Chl b, and TC mg g−1 FB (fresh biomass) of tomato plants at different levels of BPA (a) or PNP (b). Mean values with different letters are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Tukey’s test. * and ** = Significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 confidence level.

Furthermore, it was observed that elevated levels of PNP or BPA significantly reduced the content of Chl b in tomato plants. In comparison to the control, the Chl b content of tomato plants was dramatically decreased when exposed to 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1 BPA compared with the control, with a percent drop in reduction percentages of 48, 55, 59, and 68%, respectively, at 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1 BPA. On the other hand, the impact of PNP on the content of Chl b was limited, with a recording reduction percentage of 10% for both PNP levels, compared to the control (Figure 2a and b).

The effect of PNP or BPA on carotenoid content showed a contaminant-dependent and concentration-dependent response. For BPA, the degradation of carotenoids increased with higher levels of contamination. At BPA levels of 250, 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1, there was a percent reduction of 27, 69, 75, 85, and 87%, respectively, compared to the control. On the other hand, PNP resulted in a non-significant increase in the carotenoid content at 25 and 40 mg kg−1, with percent increases of 12% and 16%, respectively, compared to the control.

The phyto-impact of PNP or BPA on osmolytes of tomato plants

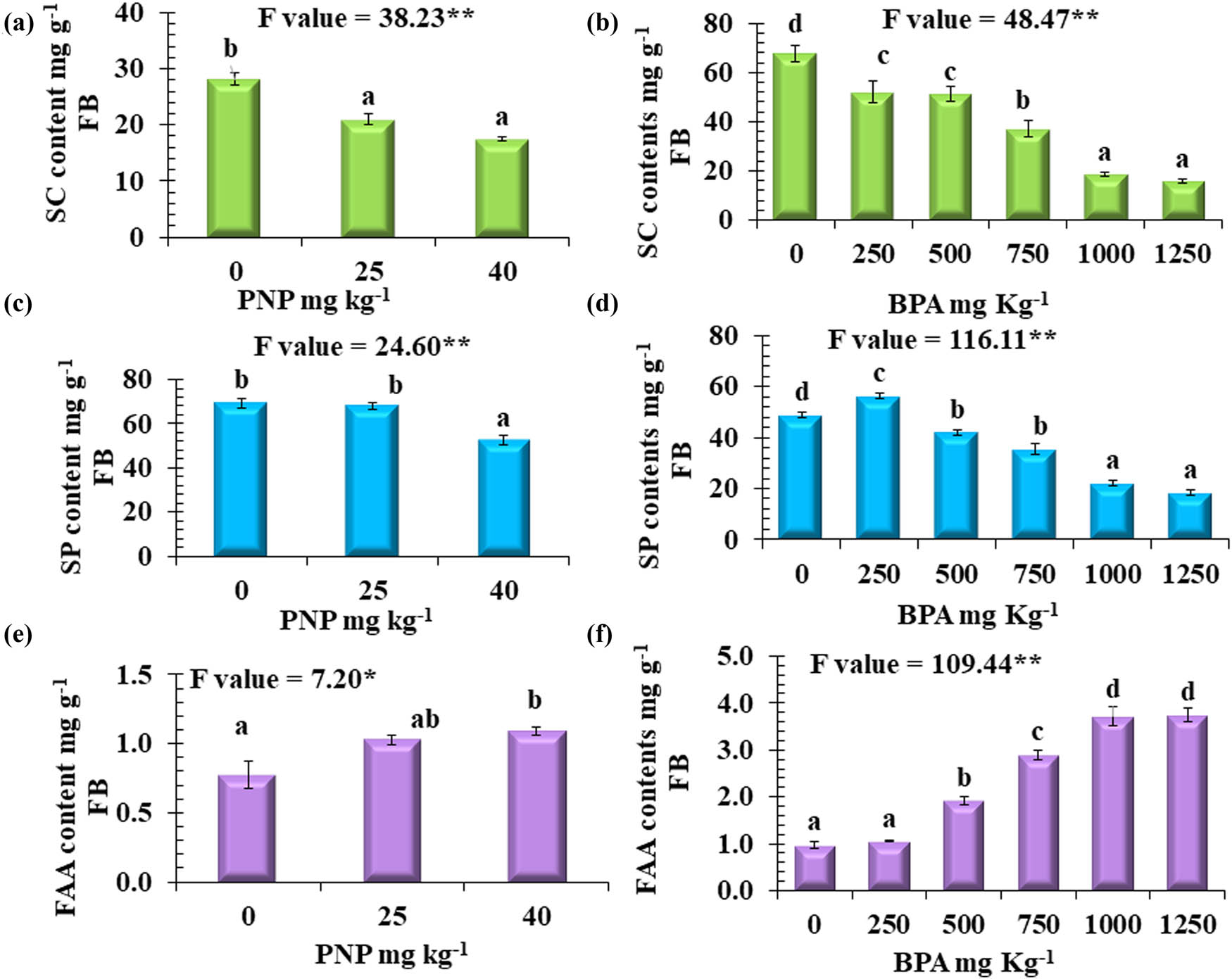

The exposure of tomato plants to PNP and BPA differentially affected the primary metabolites of leaf tissue. The statistical analysis revealed that SC was significantly in response to BPA stress. The magnitude of reduction increased as the concentration of BPA increased, with reduction percentages of 24, 45, 73, and 77% at the levels of 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1, respectively, in comparison to non-stressed plants (Figure 3b). While an increase in the SP content was observed with a percent of 15% at 250 mg kg−1,a gradual reduction of SP content was observed to be 14, 27, 55, and 63% at the levels of 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1, respectively, relative to the control plants (Figure 3d). Also, PNP contamination deregulated the contents of SC and SP in tomato leaves. In comparison to the control plants, the percent reductions of SC observed at 25 and 40 mg kg−1 were 25 and 34%, respectively, and those for SP were 10 and 22%, respectively (Figure 3a and c).

Content of (a) and (b): SC, (c) and (d): SP, (e) and (f): FAA mg g−1 FB (fresh biomass) at different levels of BPA or PNP. Values are means ± SE, n = 3. Mean values with different letters are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Tukey’s test. * and ** Significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 confidence levels.

In contrast, a reversible situation was recorded for free amino acids (FAA). For BPA, there was a highly significant accumulation, with percentage increases of 97, 197, 281, and 284% at 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1, respectively (Figure 3f), compared to non-contaminated soils. Similarly, PNP resulted in the accumulation of FAA, with percentage increases of 33 and 41% at 25 and 40 mg kg−1, respectively (Figure 3e), relative to the control.

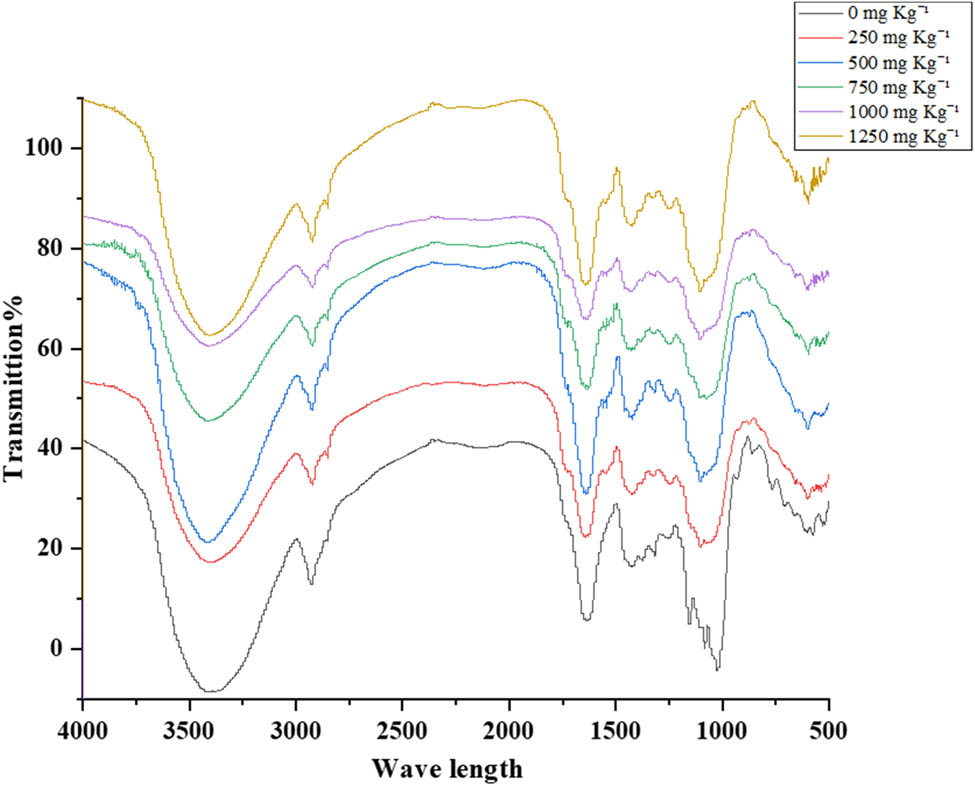

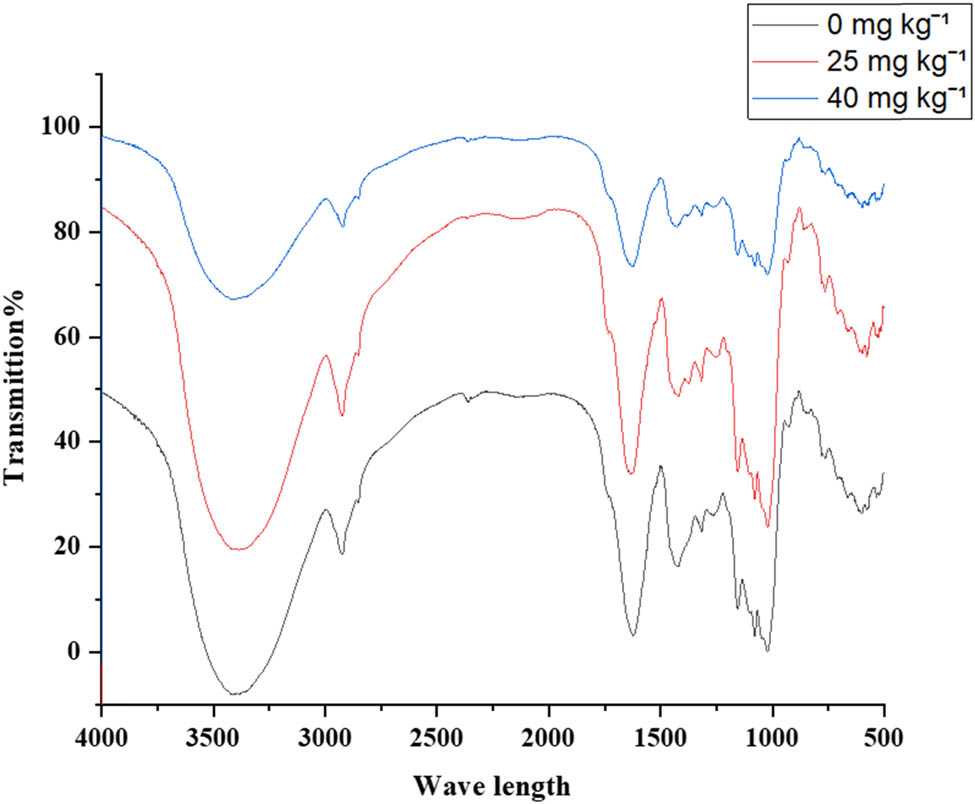

The phyto-impact of PNP or BPA on the active components of leaf tissue of tomato plants using FTIR

For detection, the main functional and characteristic groups of tomato leaves and their shift in response to PNP or BPA stresses were conducted using FTIR (Figures 4 and 5 and Tables S1 and S2). The FTIR spectra indicated the absence of peaks at 1,148, 1,022, 857, 772, and 715 cm−1 with bisphenol (mg kg−1) in comparison to the control. These wavelengths are attributed to the absence of tertiary alcohol, glucose residue disaccharide, 1,2,3-trisubstituted, 1,2-disubstituted, and benzene derivatives, respectively. These active components were recorded with PNP treatments at 1,148–1,163, 1,015–1,021, 860–864, 765–772, and 715–716, respectively, in comparison to the control plants.

FTIR spectra of tomato leaves at six levels of BPA: 0, 250, 500, 750, 1,000, and 1,250 mg kg−1.

FTIR spectra of tomato leaves at three levels of PNP: 0, 25, and 40 mg kg−1.

However, BPA and PNP have the same effect on the appearance of other active components in tomato leaves. For instance, the prominent peak attributed to the stretching vibrations of O–H and N–H functional groups was identified at wavelength 3,406 for the control. It was observed at 3,391–3,413 cm−1 for BPA and 3,384–3,413 cm−1 for PNP, which are commonly found in alcohols and aliphatic primary amines. The spectral peaks observed at wavenumbers of 2,916–2,930 cm−1 for BPA or PNP correspond to the stretching of C–H bonds, which is indicative of the presence of alkanes. The recorded peaks of C═C functional group were observed at 1,631–1,640 cm−1, indicating the presence of alkene compounds. The spectral peaks observed at 1,432–1,440 cm−1 were attributed to the O–H bending motion, which is characteristic of the carboxylic functional group. Spectral peaks corresponding to O–H bending were observed at 1,320–1,325 cm−1, indicative of phenolic compounds. The functional groups of C–O were identified in the wavenumber range of 1,248–1,262 cm−1, associated with alkyl aryl ether. The wavenumber range of 1,077–1,078 cm−1 was identified as the position of the C–O stretching functional group in the primary alcohol. Furthermore, the C–I stretching functional group, identified as a halo compound, was observed at a wavenumber of 594–602 cm−1. The spectral region of 523 cm−1 was determined to correspond to the C–Br stretching functional group in the halo compound.

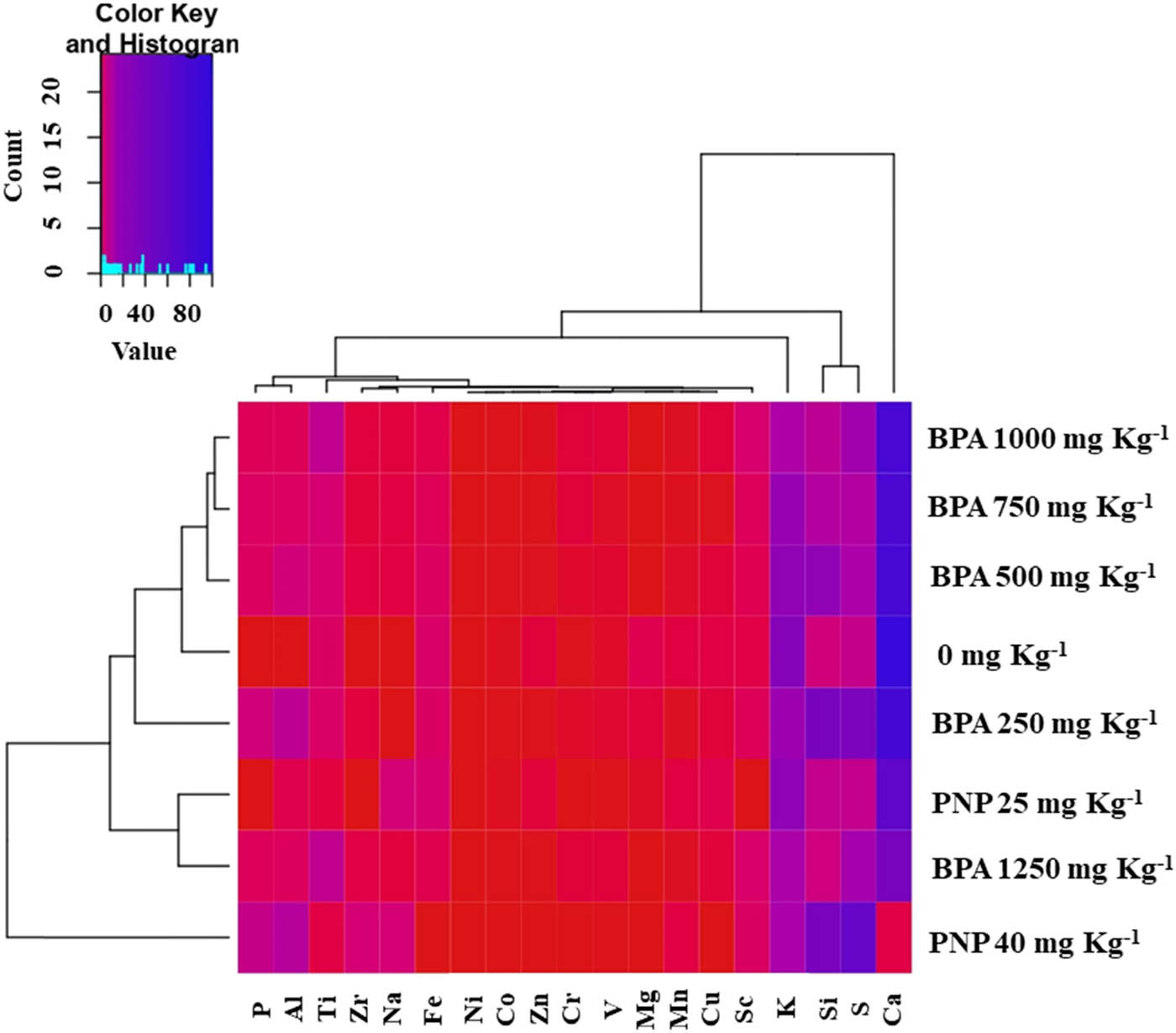

The phyto-impact of PNP or BPA on ionomic profile of tomato plants

The heatmap provides a visualization of the elemental composition of tomato leaves under various treatments (Figure 6). According to heatmap analysis, macronutrients such as Ca, Mg, K, and Zn decreased compared to the control at BPA and PNP levels. However, compared to BPA applications, Ca content was significantly affected under PNP stress.

Heatmap of elements including Mn, Na, Zr, Al, Si, P, S, Ni, Sc, Cr, Ti, V, Zn, Cu, Fe, Co, Ca, Mg, and K in tomato leaves at different levels (mg kg−1) of BPA or PNP. Mean values refer to colors from minimum displayed in red to maximum represented with blue.

In contrast, the foliar content of P increased proportionally as the levels of BPA or PNP increased in the soil. In comparison to the control, the S content of leaves was reduced under BPA toxicity, while the leaf content of S was increased in the presence of PNP compared to the control (0 mg kg−1). The essential micronutrients, such as Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, and Zn, decreased in response to BPA or PNP, whereas Si, Ti, V, Cr, Ni, Na, and Zr exhibited reversible situations.

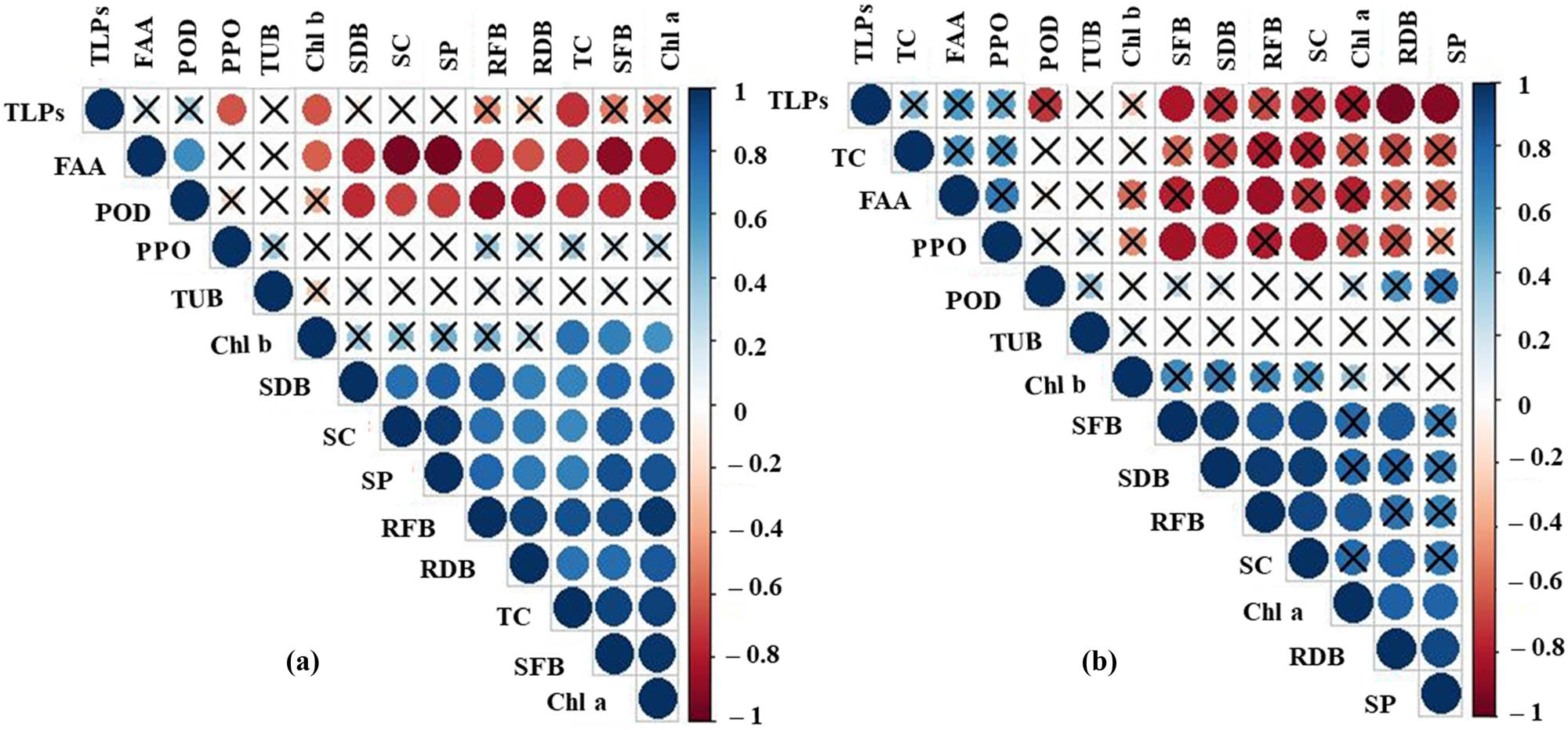

To examine the association between various estimated elements at varying concentrations of BPA or PNP, a Pearson correlation coefficient analysis was conducted (Figure S1a and b). We focused on the data related to the main elements associated with biochemical changes in our study. There was a notable positive correlation observed between Fe and Co (r = 0.92), K and Mg (r = 0.93), K and Mn (r = 0.96), Mg and Mn (r = 0.97), P and S (r = 0.94), P and Al (r = 0.94), P and Si (r = 0.96), S and Al (r = 0.97), S and Si (r = 0.96), and Al and Si (r = 0.98), in the presence of BPA. Nevertheless, a discernible negative correlation was recorded between essential elements and other trace metals, as shown in Figure S1a.

The correlation analysis of various elements at different PNP levels and control conditions revealed a positive association between K and Zn (r = 0.91), K and Ca (r = 0.95), K and Mg (r = 0.91), Fe and Cu (r = 0.99), and Fe and Co (r = 0.93). Also, a significant negative correlation was noticed with PNP treatments between Mg and Na (r = −1), Fe and Si (r = −0.95), Fe and Al (r = −0.93), Fe and S (r = −0.95), Fe and P (r = −0.95), Fe and Zr (r = −0.95), Cu and Sc (r = −0.98), Cu and S (r = −0.99), Cu and P (r = −0.98), Zn and Si (r = −0.98), Zn and Al (r = −0.96), Zn and S (r = −0.95), Zn and P (r = −0.95), Ca and Si (r = −0.93), Ca and Al (r = −0.93), Ca and S (r = −0.96), and Ca and P (r = −0.95) in Figure S1b.

The phyto-impact of PNP or BPA on the relative gene expression of tomato plants

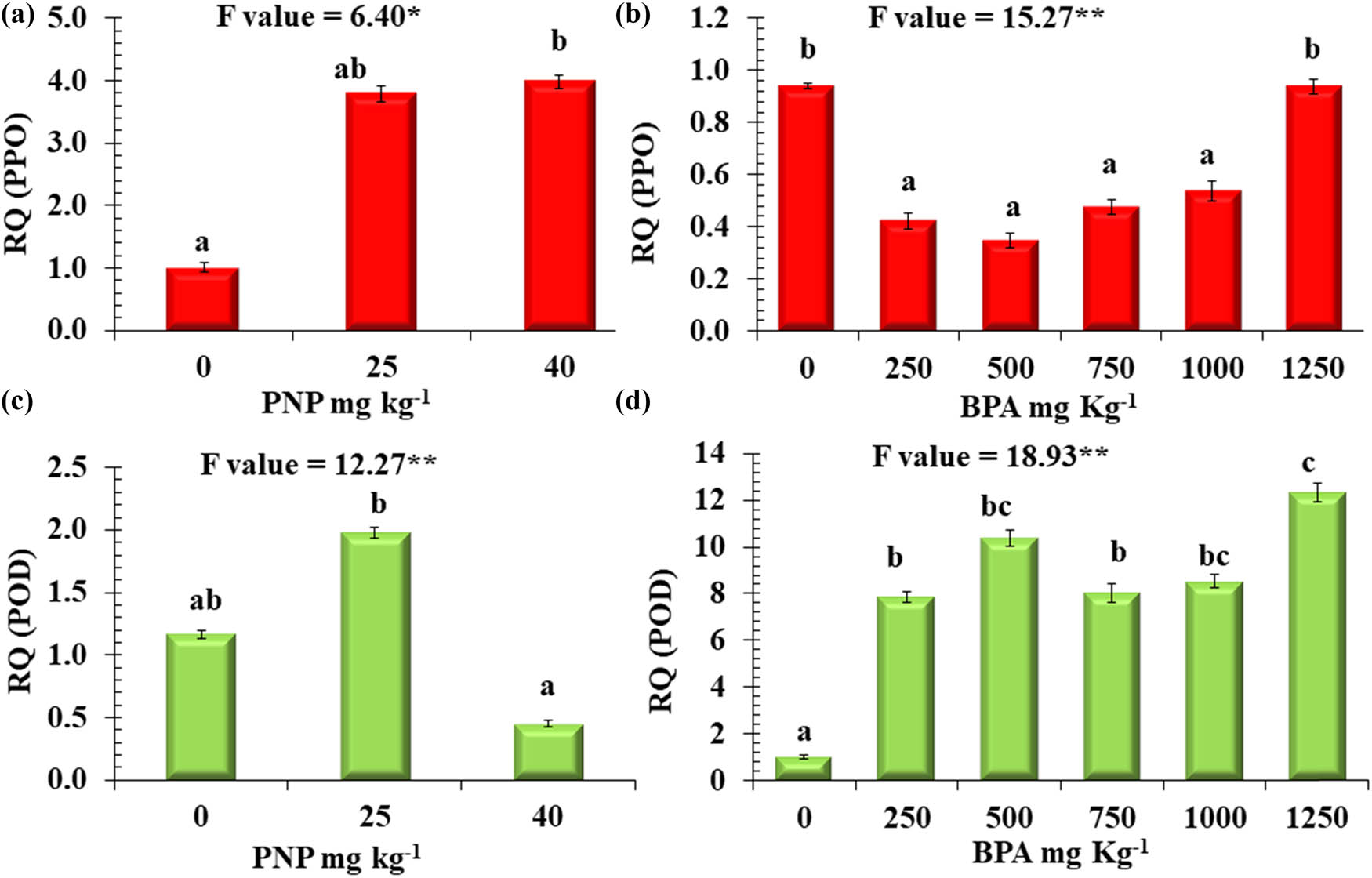

Figures 7 and 8 show a noteworthy variation in the proportional gene expression of PPO, POD, TUB, and TLPs in tomato plants when subjected to different levels of BPA and PNP. The data represented in Figure 7 revealed that the relative gene expression of PPO significantly decreased in response to BPA, except for a non-significant change recorded at a level of 1,250 mg kg−1. The results indicate a significant increase in the relative gene expression of PPO in the presence of PNP, with the highest expression being 4-fold at 40 mg kg−1 compared to the control. In Figure 7d, an increase in relative gene expression of POD was observed for BPA, with maximum expression at 1,250 mg kg−1, showing a 12.3-fold increase relative to the control. On the other hand, an increase in the relative gene expression of POD was observed in response to PNP at 25 mg kg−1, exhibiting a 2-fold increase relative to the control. In contrast, its expression decreased to 40 mg kg−1 compared to the control.

Relative quantitative expression analysis (RQ) of two genes. (a and b) PPO, (c and d) POD in tomato plants exposed to different levels of BPA or PNP. Mean values with different letters are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Tukey’s test. * and ** Significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 confidence levels.

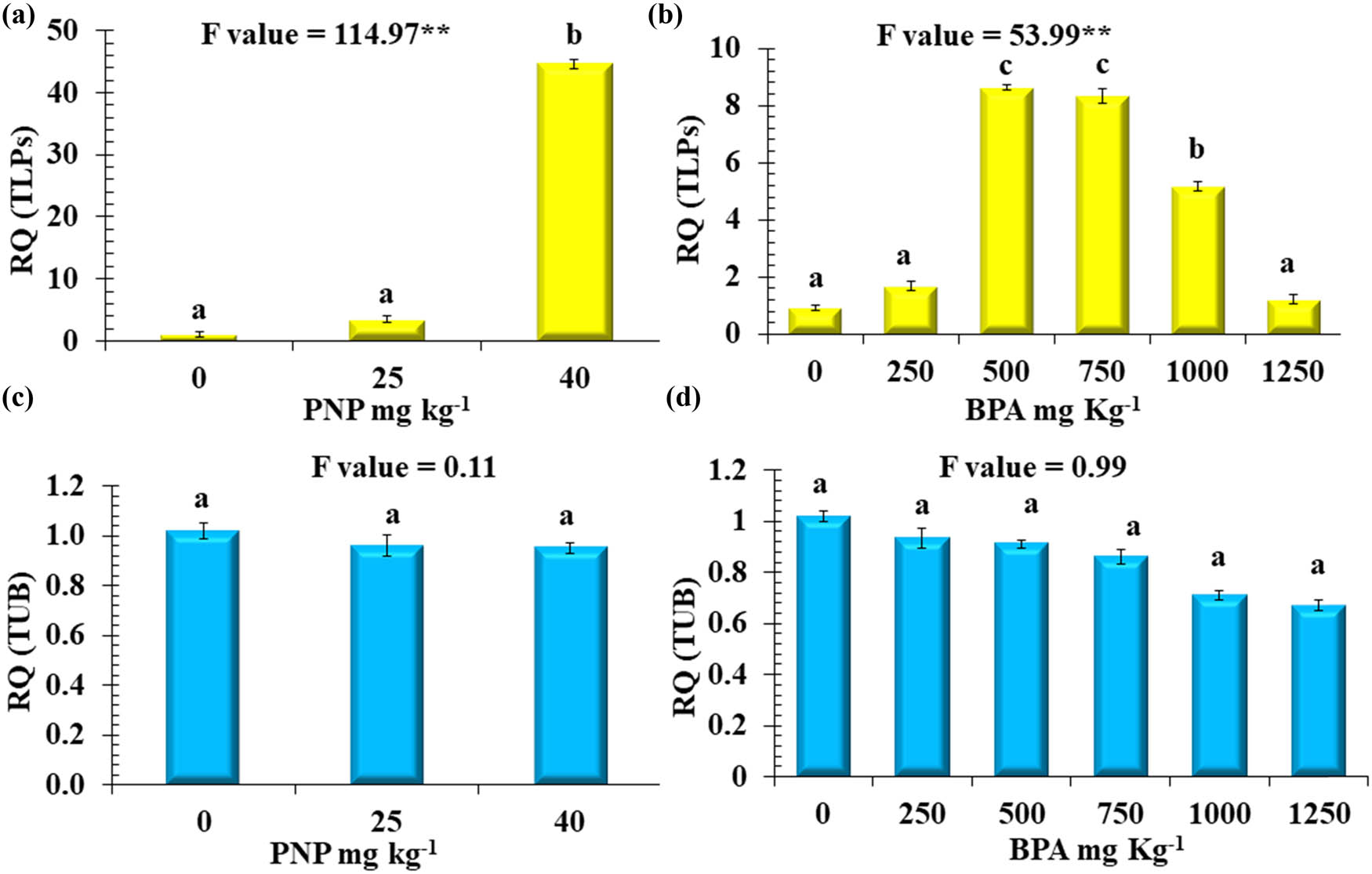

Relative quantitative expression analysis (RQ) of two genes. (a and b) TLPs and (c and d) TUB in tomato plants exposed to different levels of BPA or PNP. Mean values with different letters are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Tukey’s test. * and ** Significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 confidence levels.

The data presented in Figure 8b revealed that the relative expression of the TLP gene recorded was significantly increased in response to BPA at 500, 750, and 1,000 mg kg−1 with 8.6, 8.3, and 5.2-fold relative to the control, respectively. In comparison, 1,250 mg kg−1 of BPA had no significant change in TLP gene expression relative to the control. In response to PNP, the lowest level (25 mg kg−1) had a non-significant increase in the relative gene expression of TLPs, while there was a significant increase in the expression of the TLPs gene at concentrations of 40 mg kg−1, with a 45-fold increase relative to the control (Figure 8a). The relative expression of the TUB gene was reduced at various levels of BPA, but such a change was non-significant. Similarly, the gene expression of TUB was not affected by the presence of PNP in the contaminated soil (Figure 8c and d).

A Pearson correlation coefficient analysis was used to investigate the relationship between different morpho-biochemical traits and the relative gene expression of tomato plants at different concentrations of BPA or PNP (Figure 9a and b). For BPA, a significant positive correlation was observed between TC and SFW (r = 0.92), TC and Chl a (r = 0.94), TC and SFW (r = 0.92), TC and Chl a (r = 0.94), SC and SP (r = 0.96), RFW and RDW (r = 0.93), RFW and Chl a (r = 0.96), and SFW and Chl a (r = 0.97). However, a clear negative correlation trend was observed between FAA and SC (r = −0.94), FAA and SP (r = −0.95), and FAA and SFW (r = −0.89) (Figure 9a).

Pearson correlation plot among growth parameters, pigments, and osmolytes including SFB, RFB, SDB, RDB, Chl a, Chl b, TC, SC, SP, FAA as well as the relative expression of four genes PPO, POD, TLPs, and TUB in tomato leaves under different levels (mg kg−1) of (a) BPA, (b) PNP. The color bar on the right side represents the significant R values.

For PNP, a noteworthy positive correlation was observed between SFW and SDW (r = 0.96), SFW and SC (r = 0.91), SDW and RFW (r = 0.96), SDW and SC (r = 0.94), SDW and SFW (r = 0.96), RFW and SC (r = 0.91), and RDW and SP (r = 0.91). However, a noticeable negative correlation trend was observed under PNP stress between TLPs and RDW (r = −0.95) as well as between TLPs and SP (r = −0.92) (Figure 9b).

Discussion

The presence of BPA and PNP in water and soil impacts are emergent pollutants with lethal effects on plants and their development in the contaminated soils. The findings of the present experiment recorded a noteworthy suppression of the phenological characteristics, photosynthetic pigments, osmolytes, ionomic profile imbalance, and up- and down-regulation of the studied genes of tomato plants at different doses of BPA or PNP.

According to our study, the inhibitory effects on the biomass of shoots and roots become increasingly apparent at higher concentrations of BPA or PNP. Similarly, it was reported that exposure to elevated levels of BPA reduces the length of roots, decreases lateral roots, and darkens nearby roots, resulting in a decrease in the fresh and dry weights of soybean plants [12]. Also, it has been observed that exposure to BPA at concentrations of 10 mg L−1 and above can lead to a reduction in plant growth [4].

Photosynthetic pigments is crucial for photosynthesis and related metabolic products in plants under environmental stress. In this study, both Chl a and Chl b were adversely affected by BPA and PNP, but BPA at the higher levels had the highest effect. This reduction in chlorophyll reduced the carbon assimilation capacity of the leaves, resulting in a reduction in carbon assimilation. This inhibition of photosynthesis leads to a deficiency in the synthesis and accumulation of organic matter needed for better root growth and, ultimately, the overall growth of tomato plants under both pollutants. The positive correlation between Chl a and the biomass of shoots and roots recommended this interpretation. In addition, PNP- and BPA-stressed plants suffered from shortages in Ca, Mg, K, and Zn contents that negatively influenced chlorophyll biosynthesis. This observation was consistent with Liang et al., who stated that exposure to BPA resulted in a decrease in chlorophyll content due to a reduction in the expression of specific chloroplast proteins [45] or inhibition of mRNA associated with photosynthesis [46]. Jiao et al. reported that the high level of BPA reduced the net photosynthetic rate of soybeans by inhibiting stomatal and non-stomatal factors, such as apparent quantum efficiency, Rubisco activity, and carboxylation efficiency, in the leaves of soybean seedlings [47]. Sun et al. stated that PNP might cause a reduction in the chlorophyll precursor in the leaves of Salix babylonica, leading to the suppression of chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis [28]. Also, the study of Todirascu-Ciornea et al. illustrated that the presence of 2,4-dinitrophenol in soil reduced the chlorophyll content of Capsicum chinense [48].

Carotenoids are related to cell protection against stress-induced photo-oxidative damage, which can reduce the pressure of chlorophyll excitation, hence decreasing the light-harvesting capability. In the present study, PNP-stressed plants maintained carotenoids around the control levels, revealing a better defense against photodamage and oxidative stress. Unlikely, the decrease of carotenoids at high levels of BPA indicates impaired absorption and transfer of light energy and decreased dissipation of heat by the xanthophyll cycle. The shortage of dissipating heat can trigger excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species, hence affecting the antioxidant mechanisms of plants [49]. This is indicated by the positive correlation between carotenoids and Chl a under BPA stress.

Plants respond to abiotic stress by altering osmolyte synthesis. In this study, BPA or PNP inhibited the accumulation of SC and SP in tomato leaves. The reduction of sugars under BPA was concomitant with the absence of glucose residue in disaccharide bands recorded in the FTIR spectrum at a wavelength of 1,022 cm−1. In a related work, it was shown that the exposure of tobacco plants to BPA at 100 mg kg−1 in the soil resulted in a significant reduction in chlorophyll content and net photosynthetic rate; as a result, the content of soluble sugar contents declined [50]. Also, it was reported that the SP levels of Lemna minor exhibited an increase at low concentrations and a decrease at high concentrations of BPA [50]. In support of these findings, the Pearson correlation revealed a positive correlation between Chl a, Chl b, SP, SC, and biomass (SFB, RFB, SDB, and RDB) under BPA stress. In our investigation, it was indicated that the SP levels of Lemna minor exhibited an increase at low concentrations and a decrease at high concentrations in response to BPA [51]. A similar reduction of SP under PNP was reported by Subashchandrabose et al. and Megharaj et al. [33,52]. Wu et al. attributed the toxicity of nitrophenol on growth, relative water content, and photosynthesis rates in Arachis hypogaea to a reduction in carboxylation efficiency, hence affecting sugars and other related organic metabolites [53]. In addition, the observed reduction in chlorophyll biosynthesis in our research with BPA or PNP may lead to a decrease in sugar content, which could result in an insufficient supply for protein biosynthesis.

In contrast, the accumulation of amino acids was observed in our research in the presence of BPA or PNP. This result is consistent with Sarkar et al. who stated that after 9 days of exposure to 30 mg L−1 BPA, an increase in amino acid accumulation was detected in Azolla filiculoides compared to non-treated plants [54]. In this regard, Sun et al. illustrated that the use of BPA at concentrations of 17.2 and 50 mg L−1 retarded the activity of glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthetase cycles while promoting glutamate dehydrogenase pathways leading to the overproduction of amino acids [55]. On the other hand, the amount of FAA content enhanced by increasing the number of exposure days, up to 6 days, of Vigna radiata to PNP [56]. Thus, the potential accumulation of amino acids may occur at the expense of protein synthesis. The transition from protein biosynthesis to the accumulation of free amino acids is associated with an increased affinity for amino acid production, which in turn leads to a higher rate of protein degradation. This was also documented in the present study under BPA stress that there was a negative correlation between FAA as well as SC, SP, Chl a, Chl b, biomass (SFB, RFB, SDB, and RDB). An earlier study found a strong positive link between the fresh and dry biomass variables and the amounts of carotenoids, Chl a, SCs, and SPs [57]. However, under PNP stress, there was a negative correlation between FAA as well as RFB and RDB, revealing differential mechanisms induced by PNP or BPA on tomato plants. Previous research has observed that exposure to low-light conditions induces stress on Potamogeton crispus L., which leads to the accumulation of FAA and a reduction in the amount of SC and SP [58]. This observation may illustrate the negative correlation between FAA and SC or SP in tomato leaves under BPA and PNP treatments. Thus, both PNP or BPA induced osmotic stress on the leaves of tomato plants; hence, the water relation could be affected. In the same part, the leaves of tomato plants exposed to PNP or BPA toxicity reduced K content in their leaves, and hence stomatal function in plants, affecting the absorption of nutrients in plants (Figure 6).

The biochemical changes in the leaves of tomato plants exposed to different levels of BPA or PNP have been studied using FTIR spectroscopy by detecting the main functional groups under different treatments. In this study, FTIR analysis revealed that PNP affected the constituents of tomato leaves by shifting the absorption of many bands in comparison with free-PNP soil. However, the application of BPA in soils resulted in the absence of some functional groups compared to the control. The study by Arafa et al. revealed the presence of 31 volatile organic compounds, including terpinolene, phellandrene, p-menthane-1,2,3-triol, flavone, 3,4′,5,7-tetramethoxy, and quercetin 3′,4′,7-trimethyl ether, that have benzene derivatives analyzed by GC-MS in the five tomato genotypes [59]. Therefore, if these compounds are present in control-tomato plants, BPA stress may cause their degradation to be below the detection limit of FTIR under BPA. Furthermore, the absence of functional groups associated with the presence of benzene derivatives in the tissue of tomato plants under BPA treatment may also be related to the degradation and metabolism of BPA in stressed tomato leaves to other components [60]. In this regard, Kaźmierczak et al. reported that plants can absorb BPA from their roots and then metabolize it by hydroxylation and glucosylation, as well as redox processes. These processes result in the formation of BPA mono-O-β-d-gentiobioside and the trisaccharide BPA, monosaccharide-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1 → 4)-[β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1 → 6)] as well as β-d-glucopyranosides, mono- and di-O-β-d-glucopyranosides, and quinones [60]. In conformity, a recent study by Kim et al. reported the peak areas related to BPA in the root, stems, and leaves of BPA-stressed soybean plants at 3,400–3,000, 1,632, 1,470–440, 1,150–1,100, 805, and 723 cm [12]. Similarly, in the present study, PBA-stressed tomato leaves exhibit peaks, except at 1,150–1,100 and 805 cm, revealing degradation of BPA in our study. This may be correlated with differences in experimental conditions as well as the long period of exposure in the present study. However, PNP may not be metabolized in tomato leaves due to the detection of benzene derivates by FTIR analysis under PNP stress or because PNP has been accumulated in roots without its translocation to leaves. Thus, further studies should be extended to fruit production and detect the presence of PNP, BPA, or their degradation products using GC-MS in tomato leaves and fruits.

The ionomic profile analysis provided by the heatmap revealed that soil contaminated with BPA or PNP adversely affected plant growth via cation–anion imbalance. In this regard, Ca, Mg, and K are involved in osmoregulation and many enzyme activities, including protein synthesis, cell extension, photosynthesis, stomatal movement, and chlorophyll. As a result, the negative effects of BPA and PNP on these cations could directly retard the related physiological process [61]. In accordance with the data of the present study, Xiao et al. found that BPA (>3 mg L−1) reduced roots’ ability to absorb Mg, K, Mn, Zn, and Mo mineral elements because BPA affected the function of essential respiratory enzymes involved in root energy metabolism and even destroyed the cell’s structural integrity [16]. On the other hand, tomatoes accumulate phosphorous under BPA or PNP, which may be due to their role as a fundamental component of vital biomolecules that play a crucial role in energy metabolism, including ATP and NADPH, a key constituent of nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA, and phospholipids found in cellular membranes [62]. In addition, phosphorous is a crucial component involved in the light-dependent phase of photosynthesis [63]. In this study, tomatoes grown at different levels of BPA were characterized by stunted growth and chlorosis. This notification may be due to the decreasing S content in tomatoes’ leaves under BPA up to 1,250 mg kg−1 in comparison with plants under 0 mg kg−1. Our explanation was consistent with Schnug et al., who demonstrated that sulfur-lacking plants exhibit chlorosis, a condition characterized by the yellowing of the leaves that persists for a prolonged duration before progressing to necrosis [64].

The present investigation found that PBA or PNP-polluted soil negatively affects the content of micro-elements (Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, and Zn), which are required in small doses in plants, but also increases the accumulation of other nutrients/metals in the leaves of tomatoes (Si, Ti, V, Cr, Ni, Na, and Zr). For instance, a deficiency of zinc in a plant manifests as a decline in photosynthetic activity and a reduction in biomass production [65]. Also, deficiency of iron in response to these contaminants had negative impacts on BPA and PNP on plant chlorosis. In this regard, iron (Fe) is an essential element that is necessary for the synthesis of chlorophyll as well as the preservation of chloroplast structure and function [66]. Copper plays a crucial role as a component in plastocyanins and cytochrome oxidase. These proteins are essential components of both the photosynthetic and respiratory systems [67]. Manganese (Mn) plays a crucial role in photosynthesis, particularly in the functioning of the photosystem II–water oxidizing system, which exhibits a strict dependence on Mn [68]. The beneficial effect of Co is related to the growth and development of plant stems, its role as a cofactor in various enzymes and coenzymes, and its ability to delay leaf senescence [69]. Furthermore, another study emphasized that there is a positive and negative correlation between metals such as macro‐ and micro-nutrient homeostasis [70], which aligns with the findings of our investigation. A positive correlation was observed between Cu and Mg concentrations in the context of examining the interactions among nutrient concentrations in rice straw and grain [71]. This observation was explained by Cook et al. as a positive correlation between the leaf content of Cu and chlorophyll concentration [72]. Consequently, it can be inferred that a decrease in leaf Cu concentration in the presence of BPA or PNP leads to a decline in Mg content and photosynthesis, as Mg plays a significant role in chlorophyll synthesis. Therefore, BPA or PNP stress at toxic levels adversely affected the beneficial physiological role of Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, and Zn, as mentioned above, which was clearly observed by a decline in the tomato plant biomass.

The expression of the POD and PPO gene has a positive association with the tolerance to abiotic stress tolerance. The significant relationship between antioxidant activity and the development of stress tolerance exhibits changes in gene expression. In our research, we observed that bisphenol levels, except for 1,250 mg kg−1, significantly decreased the relative expression of PPO compared to the control. Due to its organic nature, BPA frequently undergoes alterations following absorption by plants. Previous research has indicated that crude enzymes, including PPO and potato crude enzyme preparations, can oxidize BPA, reducing or eliminating its estrogenic properties [73,74]. This mechanism could be the situation until a level of 1,000 mg kg−1 as a defense mechanism by plants to reduce BPA activity. It was reported that phenolic-related compounds, such as antioxidants/reducing agents, chelating agents, acidulants, and mixed-type inhibitors, such as ascorbic acid, chromogenic acid, malonic acids, and maclurin, impeded the activity of PPO [75–78]. Meanwhile, these compounds have similarities in their chemical formula to BPA and, hence, may have the same effect. On the other hand, the lowest dose of PNP triggered PPO gene expression. Similarly, the administration of dinitrophenol resulted in a significant up-regulation of VrPAL1 and VrPAL2 gene expression, as well as VrCHS, VrCAD, and VrC4M gene expression. These genes encode PAL and C4M, which are two crucial enzymes involved in phenylpropanoid metabolism, resulting in the production of phenolic compounds, hence improving the expression of PPO [56].

Plant PODs have been used as biochemical markers for various types of biotic and abiotic stresses due to their role in very important physiological processes, such as the control of growth by lignification, cross-linking of pectins, and antioxidant responses. The data from the present work revealed that the POD gene expression of tomatoes showed an increased proportion to the increase in bisphenol concentration up to 1,250 mg kg−1 as well as 25 mg kg−1 PNP. Concurrent with the results of the present study, it was found that POD activities observed in the leaves of maize plants that were exposed to BPA were significantly increased when compared to the control [79]. In the case of PNP, it was found that the POD activities of Vigna radiate’s leaf exposed to PNP at a concentration of 2 mM on days 4 and 6 were significantly elevated at 9.77% compared to the control [56]. Also, it was reported that PNP treatment resulted in a notable elevation in the POD activity of Capsicum sp. compared to the control, thereby reaffirming the potent toxicity of this agent [48]. These results were explained by Chen et al. who reported that the observed increase in POD activity is attributed to treatment with 2,4-dinitrophenol, which may stimulate the lignification, suberization, and auxin catabolism, as well as the germination and growth processes of wheat seedlings [56]. This finding supports the results of the present investigation. Furthermore, the POD enzyme is believed to play a role in the polymerization of aromatic monomers [80]. It could be a reason for the absence of 1,2,3-trisubstituted, 1,2-disubstituted, and benzene derivatives in tomato leaves treated with BPA. At the same time, the absorbance spectra of these components by FTIR were shifted on PNP treatment compared to the control group. In the present study, there is a positive correlation between FAA content and POD relative expression in stressed tomato plants. It was observed that the foliar application of amino acids resulted in a notable increase in the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as POD and PPO [81].

It is well known that TLPs are a class of plant proteins that are known to be involved in various stress responses, including biotic and abiotic stresses. These proteins have been implicated in plant defense mechanisms against pathogens and environmental stresses [82]. The current investigation involved the relative expression of TLPs in tomato plants subjected to abiotic stress such as BPA or PNP. This investigation highlights the significance of TLPs in tomato plants exposed to bisphenol at the specified concentrations, while no significant impact was observed at higher bisphenol concentrations. Recent research has indicated that TLPs play a role in plant reactions to non-living environmental factors. For instance, the heightened expression of GmTLP8 resulted in an increase in soybean resistance to drought and salt stress through the activation of stress-responsive genes situated downstream [83]. In another study, the results of the qRT-PCR analysis indicated that the expression patterns of the TLP genes were notably high in various wheat tissues and under high-temperature conditions. This experiment suggests that TLP genes may be involved in mediating wheat resistance [84]. TUB and TUB-like proteins form microtubules, which are essential components of the plant cell cytoskeleton [85]. The findings of this study demonstrate the inability of tomato plants to induce the relative expression of the TUB genes. Other studies showed that when guars (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L. Taubert) were stressed by drought, TUB gene expression remained steady [86]. The current study supports the previous research by finding no statistically significant changes in the gene expression of TUB under the stress conditions of BPA or PNP.

Conclusions

Both BPA and PNP compounds diminish plant growth by redirecting energy from growth to homeostasis and reducing the carbon and nitrogen metabolic products, and hence, tomato plants are subjected to osmotic stress. The harmful effects on photosynthetic efficiency and primary metabolites were observed starting at 40 and 500 mg kg−1 PNP and BPA, respectively. The imbalance of ionic homeostasis induced by PNP and BPA impacted cation–anion imbalance of various metabolic pathways, including various enzymatic activities, protein synthesis, photosynthesis, and chlorophyll, in addition to nutrient-deficiency symptoms such as chlorosis and causing growth retardation. Tomato plants exhibited changes in gene expression of antioxidants and TLPs; however, the TUB gene was not significantly affected in playing a role in the acclimation of tomatoes to these emergent contaminants. In future research, it is advisable to utilize a potent mitigating agent that may effectively modulate physiological and biochemical processes in response to BPA and PNP stresses. In future work, translocation of BPA or PNP and their degradation products should be investigated from soil–root–stem–leaves–fruits to assess how these contaminants reach humans from plants.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their profound appreciation to the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education for granting a scholarship opportunity at the Egypt–Japan University of Science and Technology.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Mahmoud S. Abdelmoneim: conceptualization, methodology, providing chemicals, practical work, statistical analysis, investigation, and writing; Elsayed E. Hafez: supervision, conceptualization, review and editing, methodology, providing reagents and devices; Mona F. A. Dawood: supervision, conceptualization, methodology, writing, review, and editing; Sherif F. Hammad: supervision, providing chemicals and devices, and review; Mohamed A. Ghazy: main supervisor, review, and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Mohammadi S, Kargari A, Sanaeepur H, Abbassian K, Najafi A, Mofarrah E. Phenol removal from industrial wastewaters: a short review. Desalin Water Treat. 2015;53:2215–34.10.1080/19443994.2014.883327Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Lü H, Tang G-X, Huang Y-H, Mo C-H, Zhao H-M, Xiang L, et al. Response and adaptation of rhizosphere microbiome to organic pollutants with enriching pollutant-degraders and genes for bioremediation: A critical review. Sci Total Environ. 2023;169425.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169425Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Al-Saleh I, Elkhatib R, Al-Rajoudi T, Al-Qudaihi G. Assessing the concentration of phthalate esters (PAEs) and bisphenol A (BPA) and the genotoxic potential of treated wastewater (final effluent) in Saudi Arabia. Sci Total Environ. 2017;578:440–51.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.207Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Xiao C, Wang L, Zhou Q, Huang X. Hazards of bisphenol A (BPA) exposure: A systematic review of plant toxicology studies. J Hazard Mater. 2020;384:121488.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121488Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Rotimi OA, Olawole TD, De Campos OC, Adelani IB, Rotimi SO. Bisphenol A in Africa: A review of environmental and biological levels. Sci Total Environ. 2021;764:142854.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142854Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Wang R, Ma X, Liu T, Li Y, Song L, Tjong SC, et al. Degradation aspects of endocrine disrupting chemicals: A review on photocatalytic processes and photocatalysts. Appl Catal A-Gen. 2020;597:117547.10.1016/j.apcata.2020.117547Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Abraham A, Chakraborty P. A review on sources and health impacts of bisphenol A. Rev Environ Health. 2020;35:201–10.10.1515/reveh-2019-0034Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Kim D, Kwak JI, An YJ. Effects of bisphenol A in soil on growth, photosynthesis activity, and genistein levels in crop plants (Vigna radiata). Chemosphere. 2018;209:875–82.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.146Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Yamamoto T, Yasuhara A, Shiraishi H, Nakasugi O. Bisphenol A in hazardous waste landfill leachates. Chemosphere. 2001;42:415–8.10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00079-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Vasiljevic T, Harner T. Bisphenol A and its analogues in outdoor and indoor air: Properties, sources and global levels. Sci Total Environ. 2021;789:148013.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Lambré C, Barat Baviera JM, Bolognesi C, Chesson A, et al. Re‐evaluation of the risks to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs. EFSA J. 2023;21:e06857. Efsa Panel on Food Contact Materials E, Processing A.10.2903/j.efsa.2023.6857Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Kim E, Song M, Ramu AG, Choi D. Analysis of impacts of exogenous pollutant bisphenol-A penetration on soybeans roots and their biological growth. RSC Adv. 2023;13:9781–7.10.1039/D2RA08090GSuche in Google Scholar

[13] Bourgeade P, Aleya E, Alaoui-Sosse L, Herlem G, Alaoui-Sosse B, Bourioug M. Growth, pigment changes, and photosystem II activity in the aquatic macrophyte Lemna minor exposed to bisphenol A. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:68671–8.10.1007/s11356-021-15422-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Ramu AG, Yang DJ, Al Olayan EM, AlAmri OD, Aloufi AS, Almushawwah JO, et al. Synthesis of hierarchically structured T-ZnO-rGO-PEI composite and their catalytic removal of colour and colourless phenolic compounds. Chemosphere. 2021;267:129245.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.129245Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Wang S, Wang L, Hua W, Zhou M, Wang Q, Zhou Q, et al. Effects of bisphenol A, an environmental endocrine disruptor, on the endogenous hormones of plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22:17653–62.10.1007/s11356-015-4972-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Xiao C, Wang L, Hu D, Zhou Q, Huang X. Effects of exogenous bisphenol A on the function of mitochondria in root cells of soybean (Glycine max L.) seedlings. Chemosphere. 2019;222:619–27.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.195Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Liu Y, Luan J, Zhang C, Ke X, Zhang H. The adsorption behavior of multiple contaminants like heavy metal ions and p-nitrophenol on organic-modified montmorillonite. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:10387–97.10.1007/s11356-019-04459-wSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Xu J, Wang B, Zhang W-h, Zhang F-J, Deng Y-d, Wang Y, et al. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol by engineered strain. AMB Express. 2021;11:1–8.10.1186/s13568-021-01284-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Yue W, Chen M, Cheng Z, Xie L, Li M. Bioaugmentation of strain Methylobacterium sp. C1 towards p-nitrophenol removal with broad spectrum coaggregating bacteria in sequencing batch biofilm reactors. J Hazard Mater. 2018;344:431–40.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.039Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Bilal M, Bagheri AR, Bhatt P, Chen S. Environmental occurrence, toxicity concerns, and remediation of recalcitrant nitroaromatic compounds. J Environ Manage. 2021;291:112685.10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112685Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Ren S, Li Y, Li C. Effects of p-nitrophenol exposure on the testicular development and semen quality of roosters. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2021;301:113656.10.1016/j.ygcen.2020.113656Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Region VUS. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC: 1986.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Uhlenbrook S, Connor R. The United Nations world water development report 2019: leaving no one behind.; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Kovacic P, Somanathan R. Nitroaromatic compounds: Environmental toxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, therapy and mechanism. J Appl Toxicol. 2014;34:810–24.10.1002/jat.2980Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Saber SEM, Jamil SNAM, Abdullah LC, Choong TSY, Ting TM. Insights into the p-nitrophenol adsorption by amidoxime-modified poly (acrylonitrile-co-acrylic acid): characterization, kinetics, isotherm, thermodynamic, regeneration and mechanism study. RSC Adv. 2021;11:8150–62.10.1039/D0RA10910JSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Urióstegui-Acosta M, Tello-Mora P, de Jesús Solís-Heredia M, Ortega-Olvera JM, Piña-Guzmán B, Martín-Tapia D, et al. Methyl parathion causes genetic damage in sperm and disrupts the permeability of the blood-testis barrier by an oxidant mechanism in mice. Toxicology. 2020;438:152463.10.1016/j.tox.2020.152463Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Scheidemann P, Klunk A, Sens C, Werner D. Species dependent uptake and tolerance of nitroaromatic compounds by higher plants. J Plant Physiol. 1998;152:242–7.10.1016/S0176-1617(98)80139-9Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Sun C, Li C, Mu W, Ma L, Xie H, Xu J. The photosynthetic physiological response and purification effect of Salix babylonica to 2, 4-dinitrophenol wastewater. Int J Phytorem. 2022;24:675–83.10.1080/15226514.2021.1962799Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Rocheleau S, Kuperman RG, Martel M, Paquet L, Bardai G, Wong S, et al. Phytotoxicity of nitroaromatic energetic compounds freshly amended or weathered and aged in sandy loam soil. Chemosphere. 2006;62:545–58.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.06.057Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Adamek M, Kavčič A, Debeljak M, Šala M, Grdadolnik J, Vogel-Mikuš K, et al. Toxicity of nitrophenolic pollutant 4-nitroguaiacol to terrestrial plants and comparison with its non-nitro analogue guaiacol (2-methoxyphenol). Sci Rep. 2024;14:2198.10.1038/s41598-024-52610-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Salama HS, Shehata IE-S, Ebada IM, Fouda M, Ismail IAE-K. Prediction of annual generations of the tomato leaf miner Tuta absoluta on tomato cultivations in Egypt. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2019;43:1–11.10.1186/s42269-019-0123-9Suche in Google Scholar

[32] FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United NationsDataset. Accessed 15 August 2017. 2012 Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Subashchandrabose SR, Megharaj M, Venkateswarlu K, Naidu R. p‐Nitrophenol toxicity to and its removal by three select soil isolates of microalgae: the role of antioxidants. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2012;31:1980–8.10.1002/etc.1931Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Lichtenthaler HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 148, USA: Academic Press; 1987.10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Fales F. The assimilation and degradation of carbohydrates by yeast cells. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:113–24.10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52433-4Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Schlegel HG. Die Verwertung organischer Säuren durch Chlorella im Licht. Planta. 1956;47:510–26.10.1007/BF01935418Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75.10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52451-6Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Lee YP, Takahashi T. An improved colorimetric determination of amino acids with the use of ninhydrin. Anal Biochem. 1966;14:71–7.10.1016/0003-2697(66)90057-1Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Hsu J-H, Lo S-L. Chemical and spectroscopic analysis of organic matter transformations during composting of pig manure. Environ Pollut. 1999;104:189–96.10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00193-6Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Guerra MBB, de Almeida E, Carvalho GGA, Souza PF, Nunes LC, Júnior DS, et al. Comparison of analytical performance of benchtop and handheld energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence systems for the direct analysis of plant materials. J Anal At Spectrom. 2014;29:1667–74.10.1039/C4JA00083HSuche in Google Scholar

[41] Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction: twenty-something years on. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:581–5.10.1038/nprot.2006.83Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Abdelkhalek A, Ismail IA, Dessoky ES, El-Hallous EI, Hafez E. A tomato kinesin-like protein is associated with Tobacco mosaic virus infection. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2019;33:1424–33.10.1080/13102818.2019.1673207Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Hafez EE, Abdelkhalek AA, El-Wahab ASE-DA, Galal FH. Altered gene expression: Induction/suppression in leek elicited by Iris Yellow Spot Virus infection (IYSV) Egyptian isolate. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2013;27:4061–8.10.5504/BBEQ.2013.0068Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8.10.1006/meth.2001.1262Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Liang J, Li Y, Xie P, Liu C, Yu L, Ma X. Dualistic effects of bisphenol A on growth, photosynthetic and oxidative stress of duckweed (Lemna minor). Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:87717–29.10.1007/s11356-022-21785-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Tian Y-S, Jin X-F, Fu X-Y, Zhao W, Han H-J, Zhu B, et al. Microarray analysis of differentially expressed gene responses to bisphenol A in Arabidopsis. J Toxicol Sci. 2014;39:671–9.10.2131/jts.39.671Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Jiao L, Wang L, Zhou Q, Huang X. Stomatal and non-stomatal factors regulated the photosynthesis of soybean seedlings in the present of exogenous bisphenol A. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2017;145:150–60.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.07.028Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Todirascu-Ciornea E, Dumitru G. Heavy metals and 2, 4-dinitrophenol impact on some physiological and biochemical parameters in capsicum species. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2019;62:e19180115.10.1590/1678-4324-2019180115Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Azeem M, Pirjan K, Qasim M, Mahmood A, Javed T, Muhammad H, et al. Salinity stress improves antioxidant potential by modulating physio-biochemical responses in Moringa oleifera Lam. Sci Rep. 2023;13:2895.10.1038/s41598-023-29954-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Fu W, Chen X, Zheng X, Liu A, Wang W, Ji J, et al. Phytoremediation potential, antioxidant response, photosynthetic behavior and rhizosphere bacterial community adaptation of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) in a bisphenol A-contaminated soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:84366–82.10.1007/s11356-022-21765-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Sun Y, Sun P, Wang C, Liao J, Ni J, Zhang T, et al. Growth, physiological function, and antioxidant defense system responses of Lemna minor L. to decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) induced phytotoxicity. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;139:113–20.10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.03.018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Megharaj M, Pearson HW, Venkateswarlu K. Effects of phenolic compounds on growth and metabolic activities of Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus bijugatus isolated from soil. Plant Soil. 1992;140:25–34.10.1007/BF00012803Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Wu Z-F, Sun X-W, Wang C-B, Zheng Y-P, Wan S-B, Liu J-H, et al. Effects of low light stress on rubisco activity and the ultrastructure of chloroplast in functional leaves of peanut. Chin J Plant Ecol. 2014;38:740.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Sarkar A, Gogoi N, Roy S. Bisphenol-A incite dose-dependent dissimilitude in the growth pattern, physiology, oxidative status, and metabolite profile of Azolla filiculoides. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:91325–44.10.1007/s11356-022-22107-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Sun H, Wang LH, Zhou Q, Huang XH. Effects of bisphenol A on ammonium assimilation in soybean roots. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2013;20:8484–90.10.1007/s11356-013-1771-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Chen L, Tan JTG, Zhao X, Yang D, Yang H. Energy regulated enzyme and non-enzyme-based antioxidant properties of harvested organic mung bean sprouts (Vigna radiata). LWT. 2019;107:228–35.10.1016/j.lwt.2019.03.023Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Abdel Latef AAH, Abu Alhmad MF, Kordrostami M, Abo–Baker A-BA-E, Zakir A. Inoculation with Azospirillum lipoferum or Azotobacter chroococcum reinforces maize growth by improving physiological activities under saline conditions. J Plant Growth Regul. 2020;39:1293–306.10.1007/s00344-020-10065-9Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Zhang M, Cao T, Ni L, Xie P, Li Z. Carbon, nitrogen and antioxidant enzyme responses of Potamogeton crispus to both low light and high nutrient stresses. Environ Exp Bot. 2010;68:44–50.10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.09.003Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Arafa RA, Kamel SM, Taher DI, Solberg SØ, Rakha MT. Leaf Extracts from Resistant Wild Tomato Can Be Used to Control Late Blight (Phytophthora infestans) in the Cultivated Tomato. Plants. 2022;11:1824.10.3390/plants11141824Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Kaźmierczak A, Kornaś A, Mościpan M, Łęcka J. Influence of bisphenol A on growth and metabolism of Vicia faba ssp. minor seedlings depending on lighting conditions. Sci Rep. 2022;12:20259.10.1038/s41598-022-24219-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[61] Hawkesford MJ, Çakmak İ, Coskun D, De Kok LJ, Lambers H, Schjoerring JK, et al. Functions of macronutrients. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Plants. USA: Academic press; 2023. p. 201–81.10.1016/B978-0-12-819773-8.00019-8Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Kamerlin SCL, Sharma PK, Prasad RB, Warshel A. Why nature really chose phosphate. Q Rev Biophys. 2013;46:1–132.10.1017/S0033583512000157Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Carstensen A, Herdean A, Schmidt SB, Sharma A, Spetea C, Pribil M, et al. The impacts of phosphorus deficiency on the photosynthetic electron transport chain. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:271–84.10.1104/pp.17.01624Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Schnug E, Haneklaus S. Sulphur deficiency symptoms in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.)-the aesthetics of starvation. Phyton-Horn. 2005;45:79.Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Zhao C, Chen X, Ouyang L, Wang J, Jin M. Robust moving-blocker scatter correction for cone-beam computed tomography using multiple-view information. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189620.10.1371/journal.pone.0189620Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[66] Rehman H-u, Aziz T, Farooq M, Wakeel A, Rengel Z. Zinc nutrition in rice production systems: a review. Plant Soil. 2012;361:203–26.10.1007/s11104-012-1346-9Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Yadav SK. Heavy metals toxicity in plants: an overview on the role of glutathione and phytochelatins in heavy metal stress tolerance of plants. South Afr J Bot. 2010;76:167–79.10.1016/j.sajb.2009.10.007Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Andresen E, Peiter E, Küpper H. Trace metal metabolism in plants. J Exp Bot. 2018;69:909–54.10.1093/jxb/erx465Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Taga ME, Walker GC. Sinorhizobium meliloti requires a cobalamin-dependent ribonucleotide reductase for symbiosis with its plant host. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2010;23:1643–54.10.1094/MPMI-07-10-0151Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Bournier M, Tissot N, Mari S, Boucherez J, Lacombe E, Briat J-F, et al. Arabidopsis ferritin 1 (AtFer1) gene regulation by the phosphate starvation response 1 (AtPHR1) transcription factor reveals a direct molecular link between iron and phosphate homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22670–80.10.1074/jbc.M113.482281Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[71] Johnson J-M, Sila A, Senthilkumar K, Shepherd KD, Saito K. Application of infrared spectroscopy for estimation of concentrations of macro-and micronutrients in rice in sub-Saharan Africa. Field Crops Res. 2021;270:108222.10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108222Suche in Google Scholar

[72] Cook CM, Kostidou A, Vardaka E, Lanaras T. Effects of copper on the growth, photosynthesis and nutrient concentrations of Phaseolus plants. Photosynthetica. 1998;34:179–93.10.1023/A:1006832321946Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Kang J-H, Katayama Y, Kondo F. Biodegradation or metabolism of bisphenol A: from microorganisms to mammals. Toxicology. 2006;217:81–90.10.1016/j.tox.2005.10.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[74] Matsushima K, Kaneda H, Harada K, Matsuura H, Hirata K. Immobilization of enzymatic extracts of Portulaca oleracea cv. roots for oxidizing aqueous bisphenol A. Biotechnol Lett. 2015;37:1037–42.10.1007/s10529-014-1761-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] McEvily AJ, Iyengar R, Otwell WS. Inhibition of enzymatic browning in foods and beverages. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1992;32:253–73.10.1080/10408399209527599Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Ding C-K, Chachin K, Ueda Y, Wang CY. Inhibition of loquat enzymatic browning by sulfhydryl compounds. Food Chem. 2002;76:213–8.10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00270-9Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Singh B, Suri K, Shevkani K, Kaur A, Kaur A, Singh N. Enzymatic browning of fruit and vegetables: A review. Enzymes in food technology: Improvements and innovations. Singapore: Springer; 2018.10.1007/978-981-13-1933-4_4Suche in Google Scholar

[78] Lee B, Moon KM, Lim JS, Park Y, Son S, Jeong HO, et al. 2-(3, 4-dihydroxybenzylidene) malononitrile as a novel anti-melanogenic compound. Oncotarget. 2017;8:91481.10.18632/oncotarget.20690Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[79] Wang Y, Zhang M, Zhao L, Zhang W, Zhao T, Chu J, et al. Effects of tetrabromobisphenol A on maize (Zea mays L.) physiological indexes, soil enzyme activity, and soil microbial biomass. Ecotoxicology. 2019;28:1–12.10.1007/s10646-018-1987-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] Todirascu-Ciornea E, Drochioiu G, Stefanescu R, Axinte EV, Dumitru G. Morphological and biochemical answer of the wheat seeds at treatment with 2, 4-dinitrophenol and potassium iodate. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2016;59:e16150580.10.1590/1678-4324-2016150580Suche in Google Scholar

[81] Ardebili ZO, Moghadam ARL, Ardebili NO, Pashaie AR. The induced physiological changes by foliar application of amino acids in Aloe vera L. plants. Plant Omics. 2012;5:279.Suche in Google Scholar

[82] Wang L, Liang J, Wang L. Genome-wide analysis of the Thaumatin-like gene family in Qingke (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum) uncovers candidates involved in plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:912296.10.3389/fpls.2022.912296Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[83] Xu H-R, Liu Y, Yu T-F, Hou Z-H, Zheng J-C, Chen J, et al. Comprehensive profiling of Tubby-Like Proteins in soybean and roles of the GmTLP8 gene in abiotic stress responses. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:844545.10.3389/fpls.2022.844545Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[84] Altaf A, Zada A, Hussain S, Gull S, Ding Y, Tao R, et al. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of Tubby gene family in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under biotic and abiotic stresses. Agronomy. 2022;12:1121.10.3390/agronomy12051121Suche in Google Scholar

[85] Chun HJ, Baek D, Jin BJ, Cho HM, Park MS, Lee SH, et al. Microtubule dynamics plays a vital role in plant adaptation and tolerance to salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5957.10.3390/ijms22115957Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[86] Jaiswal PS, Kaur N, Randhawa GS. Identification of reference genes for qRT‐PCR gene expression studies during seed development and under abiotic stresses in Cyamopsis tetragonoloba. Crop Sci. 2019;59:252–65.10.2135/cropsci2018.05.0313Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Antitumor activity of 5-hydroxy-3′,4′,6,7-tetramethoxyflavone in glioblastoma cell lines and its antagonism with radiotherapy

- Digital methylation-specific PCR: New applications for liquid biopsy

- Synergistic effects of essential oils and phenolic extracts on antimicrobial activities using blends of Artemisia campestris, Artemisia herba alba, and Citrus aurantium

- β-Amyloid peptide modulates peripheral immune responses and neuroinflammation in rats

- A novel approach for protein secondary structure prediction using encoder–decoder with attention mechanism model

- Diurnal and circadian regulation of opsin-like transcripts in the eyeless cnidarian Hydra

- Withaferin A alters the expression of microRNAs 146a-5p and 34a-5p and associated hub genes in MDA-MB-231 cells

- Toxicity of bisphenol A and p-nitrophenol on tomato plants: Morpho-physiological, ionomic profile, and antioxidants/defense-related gene expression studies

- Review Articles

- Polycystic ovary syndrome and its management: In view of oxidative stress

- Senescent adipocytes and type 2 diabetes – current knowledge and perspective concepts

- Seeing beyond the blot: A critical look at assumptions and raw data interpretation in Western blotting

- Biochemical dynamics during postharvest: Highlighting the interplay of stress during storage and maturation of fresh produce

- A comprehensive review of the interaction between COVID-19 spike proteins with mammalian small and major heat shock proteins

- Exploring cardiovascular implications in systemic lupus erythematosus: A holistic analysis of complications, diagnostic criteria, and therapeutic modalities, encompassing pharmacological and adjuvant approaches

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Antitumor activity of 5-hydroxy-3′,4′,6,7-tetramethoxyflavone in glioblastoma cell lines and its antagonism with radiotherapy

- Digital methylation-specific PCR: New applications for liquid biopsy

- Synergistic effects of essential oils and phenolic extracts on antimicrobial activities using blends of Artemisia campestris, Artemisia herba alba, and Citrus aurantium

- β-Amyloid peptide modulates peripheral immune responses and neuroinflammation in rats

- A novel approach for protein secondary structure prediction using encoder–decoder with attention mechanism model