Antitumor activity of 5-hydroxy-3′,4′,6,7-tetramethoxyflavone in glioblastoma cell lines and its antagonism with radiotherapy

-

Panagiota Papapetrou

Abstract

5-Hydroxy-3′,4′,6,7-tetramethoxyflavone (TMF) is a plant-origin flavone known for its anti-cancer properties. In the present study, the cytotoxic effect of TMF was evaluated in the U87MG and T98G glioblastoma (GBM) cell lines. The effect of TMF on cell viability was assessed with trypan blue exclusion assay and crystal violet staining. In addition, flow cytometry was performed to examine its effect on the different phases of the cell cycle, and in vitro scratch wound assay assessed the migratory capacity of the treated cells. Furthermore, the effect of in vitro radiotherapy was also evaluated with a combination of TMF and radiation. In both cell lines, TMF treatment resulted in G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, reduced cell viability, and reduced cell migratory capacity. In contrast, there was an antagonistic property of TMF treatment with radiotherapy. These results demonstrated the antineoplastic effect of TMF in GBM cells in vitro, but the antagonistic effect with radiotherapy indicated that TMF should be further evaluated for its possible antitumor role post-radiotherapy.

Introduction

The most frequent primary malignant brain tumor in adults is glioblastoma (GBM) [1]. It is defined as grade 4 astrocytoma and consists of extremely unstable and invasive cells, which show resistance to most therapeutic approaches [2]. For this reason, it is largely considered an incurable disease with a median survival of only 15 months after diagnosis [1,3].

Considering the complex nature of GBM, combination therapy, including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, is usually recommended [4]. Surgical removal of the tumor is the primary treatment; however, due to its invasive nature, it is impossible to remove it entirely, resulting in relapse. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy act synergistically, killing residual cancer cells and thus improving patients’ life expectancy [5,6]. The most common chemotherapeutic drug used against GBM is temozolomide (TMZ). However, cancer cells often develop resistance, posing a serious challenge to successful treatment [7,8,9]. In addition, the naturally occurring blood–brain barrier (BBB) prevents successful drug delivery, allowing only very small and hydrophobic molecules to pass through. At the same time, a patients’ full recovery is hampered by the aggressive migration of cancer cells to nearby tissues [10].

In recent years, the role of natural compounds in cancer treatment has been highlighted through variant ongoing research [11,12]. Natural compounds have been isolated from several plants and have been tested as anticancer agents. One of them is curcumin, a polyphenol that has been isolated from turmeric, Curcuma longa, and acts mainly through inhibition of cellular cycle, oncogene silencing, and cancer cell apoptosis. Resveratrol is classified as a stilbenoid and is found in various plant species, such as mulberries, peanuts, and grapes. It prevents the growth of cancer cells and leads them to apoptosis. Corresponding action has been observed from lycopene too, a carotenoid found in tomatoes. Finally, camptothecin (isolated from Camptotheca acuminata) and taxol (isolated from Taxus brevifolia) cause cell cycle arrest [13,14,15].

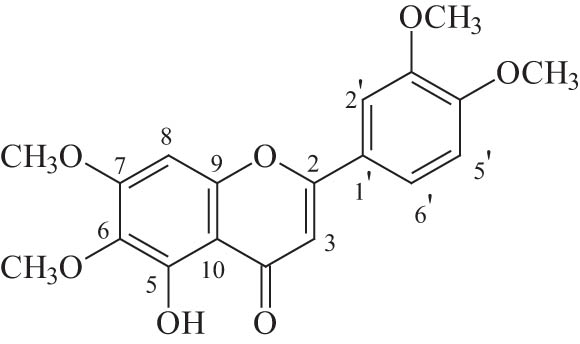

5-Hydroxy-3′,4′,6,7-tetramethoxyflavone (TMF) is a natural compound. It belongs to the group of flavonoids, more specifically in flavones, with a molecular weight of 358 kDa (Figure 1). Flavonoids are secondary metabolites that are widely found in plants, vegetables, and fruits. They protect plants from external dangers, and they have antioxidant activity. TMF has been isolated from extracts of Centaurea bruguieriana subsp. belangeriana of the Asteraceae family. C. bruguieriana subsp. belangeriana is an annual herb with purple spiky flowers and a white stem that reaches 15–50 cm tall and has several therapeutical properties [16,17,18]. The cytotoxicity of TMF has been studied in certain types of cancer, such as lung, prostate, colon, and leukemia [19]. A more prominent effect was observed in lung cancer, inhibiting the growth of cancer cells by 95%, for a concentration of 50 μM TMF. However, in prostate cancer cells, proliferation has been inhibited by only 20% at the same concentration of TMF [19]. No previous study has investigated the therapeutic potential of TMF in GBM.

Structure of TMF.

TMF and similar flavonoids are also extracted from other plants, most of them belonging to the genus Artemisia. Specifically, Artemisia haussknechtii, Artemisia argyi, Artemisia princeps, and Artemisia amygdalina Dence are some of the species that have been studied. Tanacetum chiliophyllum var. oligocephalum and Lippianodiflora are also important sources of such flavonoids [19,20,21,22,23,24].

The purpose of this study was to investigate, for the first time, the antitumor effects of TMF in GBM cell lines as a single pharmacological treatment and as a combination with radiotherapy. Our findings indicate a favorable in vitro effect of TMF against GBM cells but an antagonistic effect when it is combined with radiotherapy.

Materials and methods

Isolation and identification of TMF

TMF, a yellow powder in highly pure form (95% purity), was derived from the ethyl acetate extract of C. bruguieriana subsp. belangeriana (DC.) Bornm. (collected from the suburbs of Peshawar, Pakistan, and authenticated by Dr. Shahid Farooq, Plant Taxonomist of Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-PCSIR, Peshawar). A voucher specimen was deposited in the herbarium at the PCSIR Laboratories, Peshawar, under the code CA-001-04. The air-dried aerial parts of C. bruguieriana subsp. belangeriana (DC.) Bornm. (1.5 kg) were finely ground and extracted at room temperature with a mixture of cyclohexane:diethyl ether:methanol 1:1:1, which yielded 80.46 g of extract. The extract was redissolved with the same mixture and washed with brine. The aqueous fraction was extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc) (organic phase B, 25.81 g). Chromatographic methods such as CC (column chromatography), TLC (thin-layer chromatography), and VLC (vacuum-layer chromatography) were selected for the isolation of TMF from the extract. Organic phase B was fractioned by VLC (10.0 × 7.0 cm) on silica gel (Merck 60H, Art. 7736), with gradient elution with mixtures of solvents and yielded 11 fractions of 300 mL each (A–L). Fraction E (3.287 g), eluted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc) 100%, was subjected to VLC (10.0 × 7.0 cm) on silica gel (Merck 60H, Art. 7736), using dichloromethane (CH2Cl2)–methanol (MeOH) mixtures of increasing polarity as eluents to give 13 fractions of 300 mL each (EA-EN). Fraction EC (166.2 mg) eluted with CH2Cl2–MeOH (99:1) was refractionated (CC) on Sephadex LH-20 using MeOH as an eluent to give 11 fractions (ECA-ECL). Fraction ECG (32.5 mg) was subjected to preparative thin-layer chromatography (pTLC) on silica gel (Kieselgel F254, Merck, Art. 5715, Merck GLOBAL, Athens, Greece) with elution solvent CH2Cl2–MeOH 98:2 and yielded three bands (ECGα–ECGγ). Band ECGα (Rf = 0.29) was identified as the compound TMF (14.9 mg). Fraction ECK (41.3 mg) was subjected to preparative pTLC on silica gel (Kieselgel F254, Merck, Art. 5715, Merck GLOBAL, Athens, Greece) with elution solvent CH2Cl2–MeOH 98:2 and yielded two bands (ECK1–ECK2). Band ECK1 (Rf = 0.29) was identified as the compound TMF (34.3 mg). TLC was used to control the quality of the fractions. For the TLC, a silica gel (Kieselgel F254, Merck, Art. 5554, Merck GLOBAL, Athens, Greece) stationary phase on aluminum foil (20 cm × 20 cm, 0.1 mm) with a fluorescence marker and a cellulose (Merck, Art. 5552) stationary phase on aluminum foil (20 cm × 20 cm, 0.1 mm) was used. The development of the TLC plates was carried out using mixtures of solvents appropriate for each group of fractions. Finally, the TLC plates of silica gel were sprayed with vanillin–H2SO4 (1:1) [25], and the cellulose plates were sprayed with Naturstoffreagenz A [26]. The identification/verification of TMF was performed via 1D NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) studies (1H). The 1H-NMR was recorded in CD3OD and CDCl3 using an AGILENT DD2 500 (500.1 MHz for 1H-NMR) spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in δ (ppm) values relative to TMS (tetramethylsilane) (3.31 ppm for CD3OD and 7.24 ppm for CDCl3 for 1H-NMR). The data of isolated and identified TMF were compared with those of samples from our collection and by comparison with data reported in the literature (Table S1 and Figures S1 and S2) [27].

Cell lines

The GBM cell lines, U87MG and T98G, were derived from two patients with GBM. They were supplied by Dr W.K. Alfred Yung (Department of Neuro-Oncology, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA) and ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), respectively. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco BRL), was used to cultivate both cell lines. They were incubated in a humidified environment that was maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Natural compound treatment

TMF was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a stock concentration of 13, 15.6, and 16.5 mM and stored at −80°C. Before each experiment, stock aliquots were diluted to the desired final concentration. The final volume of each experiment included less than 1% DMSO. TMF was applied to malignant glioma cell cultures with or without radiation.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by Trypan Blue exclusion assay [28,29]. Approximately, 20,000 cells, from each cell line, were seeded in 12-well plates, and after 24 h, they were exposed to TMF-increasing concentrations. Specifically, the concentrations used were 25, 50, 75, 100, and 150 μM. The percentage of cell viability was determined after 72 h of incubation with the TMF using a phase-contrast microscope. Viability curves were then drawn, and the IC50 value was calculated for each cell line. Results were averaged by three independent experiments with duplicate runs of each sample.

Crystal violet assay

Using the crystal violet assay, cell proliferation was further evaluated after treatment with TMF [30]. Approximately, 100,000 cells were cultured in 6-well plates, incubated for 24 h, and then treated with TMF at concentrations of ½ IC50, IC50, and 2× IC50. After 72 h, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubated with the crystal violet solution 0.2% (0.2 g crystal violet powder, Merck, MA, USA) for 2–3 min, and then rinsed again with deionized water (ddH2O). After that, plates were left overnight to dry, and the next day, a phase–contrast microscope was used to take pictures of each well plate.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was used to study the effects of TMF on cell cycle, as a single treatment. It was performed after 24 and 72 h. Specifically, approximately 20,000 cells were cultured in 12-well plates, incubated for 24 h, and then treated with TMF at concentrations of ½ IC50, IC50, and 2× IC50. Cells were then treated with trypsin and washed with PBS before being incubated with propidium iodide (PI) working solution 50 µg/mL (20 mg/mL RNase A and 0.1% Triton X-100) for 20 min in the dark at 37°C. Using a flow cytometer (CYT; OMNI, Santa Marta De Tormes Salamanca, Spain), cells were analyzed and separated into the four phases G0/G1, S, G2/M, and sub-G0/G1. Each sample was repeated three times in two independent experiments, and results were obtained from the averages [31,32].

In vitro scratch wound assay

The anti-migratory properties of TMF were evaluated by wound healing assay [33]. Approximately, 10,000 cells were seeded in 6-well plates, an artificial vacuum was created, and then concentrations of TMF equal to IC50 and 2× IC50 were added. The injury caused to the cells was photographed using a phase contrast microscope at 5× magnification for four consecutive days, from t = 0 to t = 72 h. The migration distance at each of these time points was measured using the ImageJ program, while the migration width was given by the formula Widthmigration = Width0h − Width72h. Results were derived from the averages of three independent experiments.

Combination treatment with TMF and radiation

Each cell line (U87MG and T98G) was cultured in three separate 12-well plates and was treated with various combinations of TMF and radiation after 24 h. TMF was added in concentrations of 20, 40, 80, 100, and 140 μM for the U87MG cells and in concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 60 μM for the T98G cells. After 2 h, both cell lines were irradiated with two different radiation doses of 2 or 4 Gy, using a linac 6 MV accelerator (Varian MedicalSystems) as described previously in detail [28,34]. The third well plate was the control sample [34]. Cell viability was determined by the trypan blue exclusion assay after 72 h of incubation. The combination index approach of Chou and Talalay was used to assess the combinatorial effect of TMF and radiation [35]. The combination index (CI) was calculated by CompuSyn software (ComboSyn, Inc., New York, NY, USA) based on the multiple drug–effect equation and taking into account the dose–effect curves for TMF alone, radiotherapy alone, and their different combinations. The formula for measuring the Combination Index is the following: CI = (D 1/D X1) + (D 2/D X2), where D X1 and D X2 designate the doses of single treatments capable of producing a specific inhibitory effect on cell viability, where D 1 and D 2 refer to the doses of the same treatment agents that when combined can produce the same inhibitory effect as each monotherapy. The effect of the combo treatment was determined by the CI value (CI < 1 was considered a synergistic, CI = 1 additive, and CI > 1 as an antagonistic effect) [36].

Statistical analysis

All results were obtained as mean of three independent experiments ± standard deviation (SD), calculated by the statistical program MedCalc (trial version). The comparison between different experimental conditions was performed using two-way ANOVA with the post hoc Turkey test. At p-values <0.05, differences were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cytotoxicity of TMF in GBM cell lines

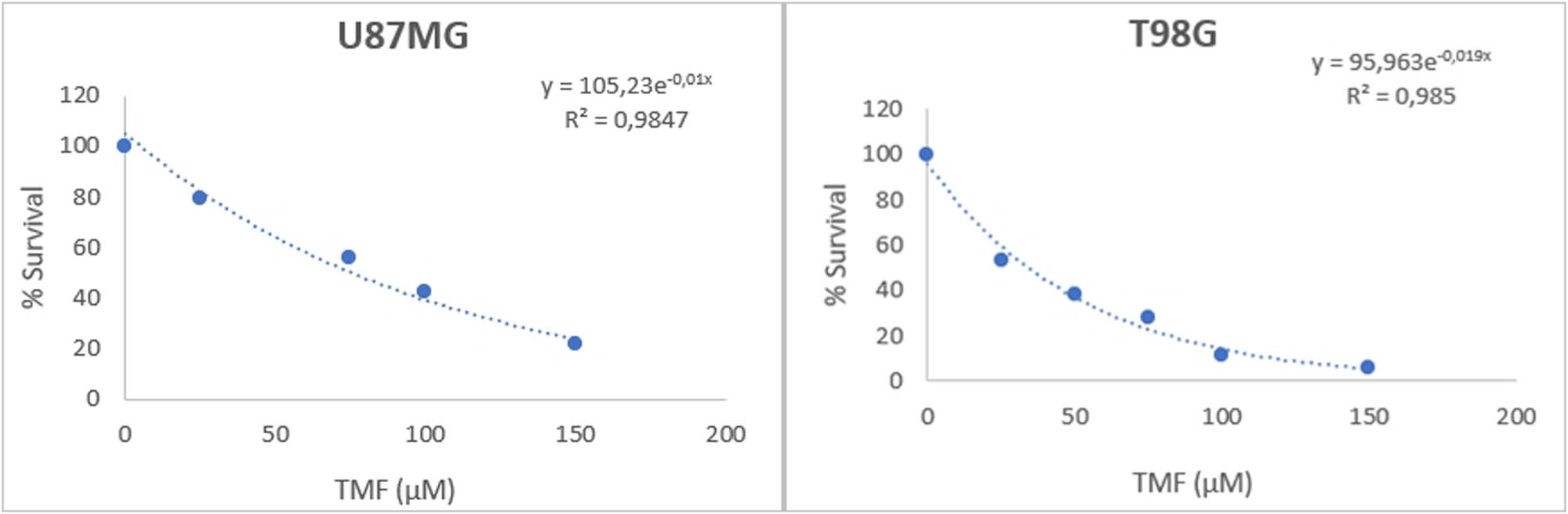

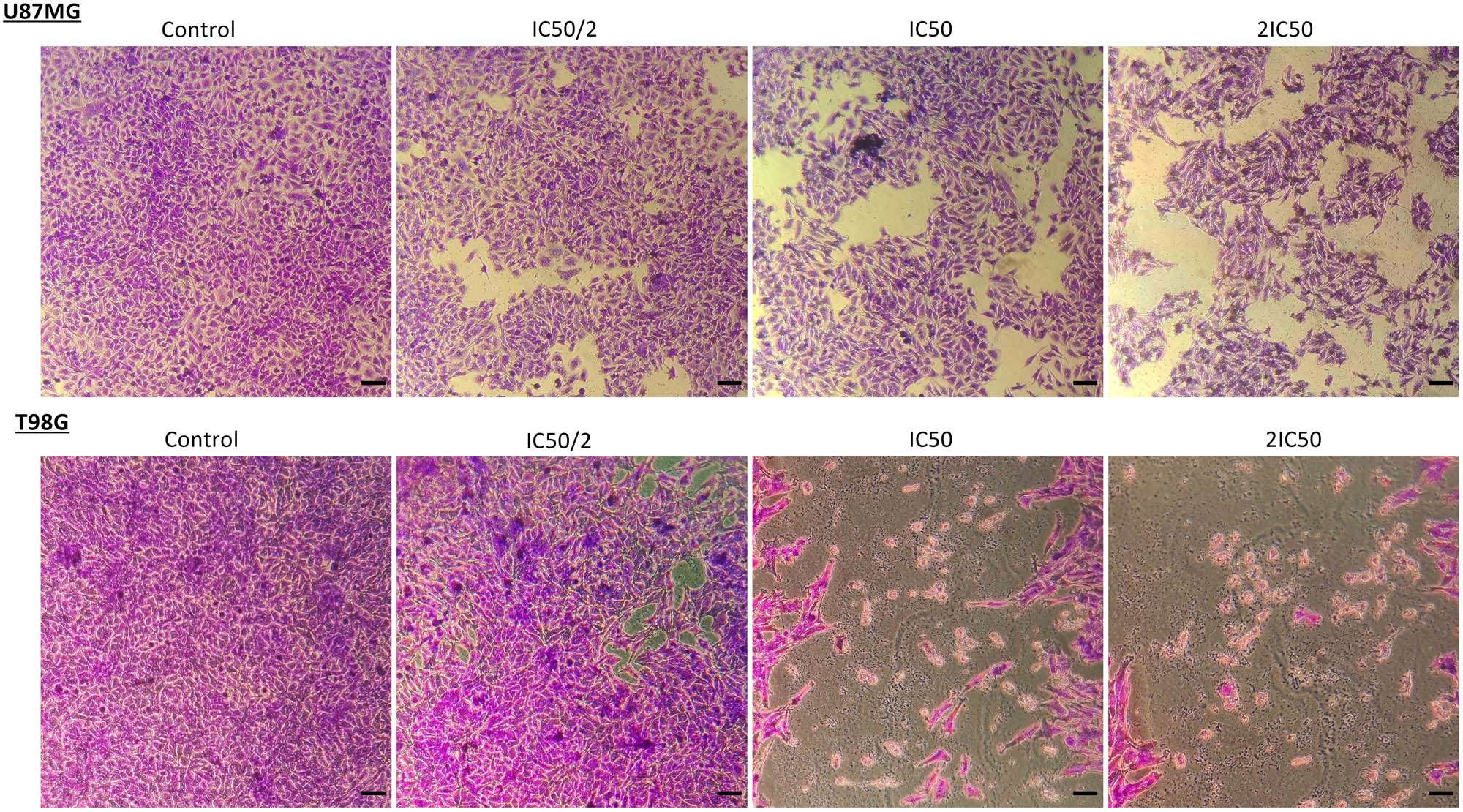

Both cell lines showed sensitivity to TMF. This outcome is shown in Figure 2. The number of surviving cells decreases exponentially, as the dose of TMF increases. The IC50 value of the TMF was 78 μM for U87MG cells and 30.5 for T98G cells after 72 h of treatment. Crystal violet staining confirmed this decrease in the cell number. Photographs were taken by using a phase-contrast microscope at 72 h post-treatment with TMF (Figure 3).

Viability of U87MG and T98G cancer cells following TMF treatment. The y-axis corresponds to the % viability of the cells, while the x-axis corresponds to the different concentrations of TMF in μM. Both curves were determined using the exponential analysis model of Microsoft 365 Excel.

Crystal violet staining (0.2% crystal violet) of U87MG and T98G cells after treatment with TMF in concentrations of IC50/2, IC50, and 2IC50. Cells that survived are represented in purple; images were taken using a phase-contrast microscope in 10× magnification. Scale bars = 100 μM.

TMF causes cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase.

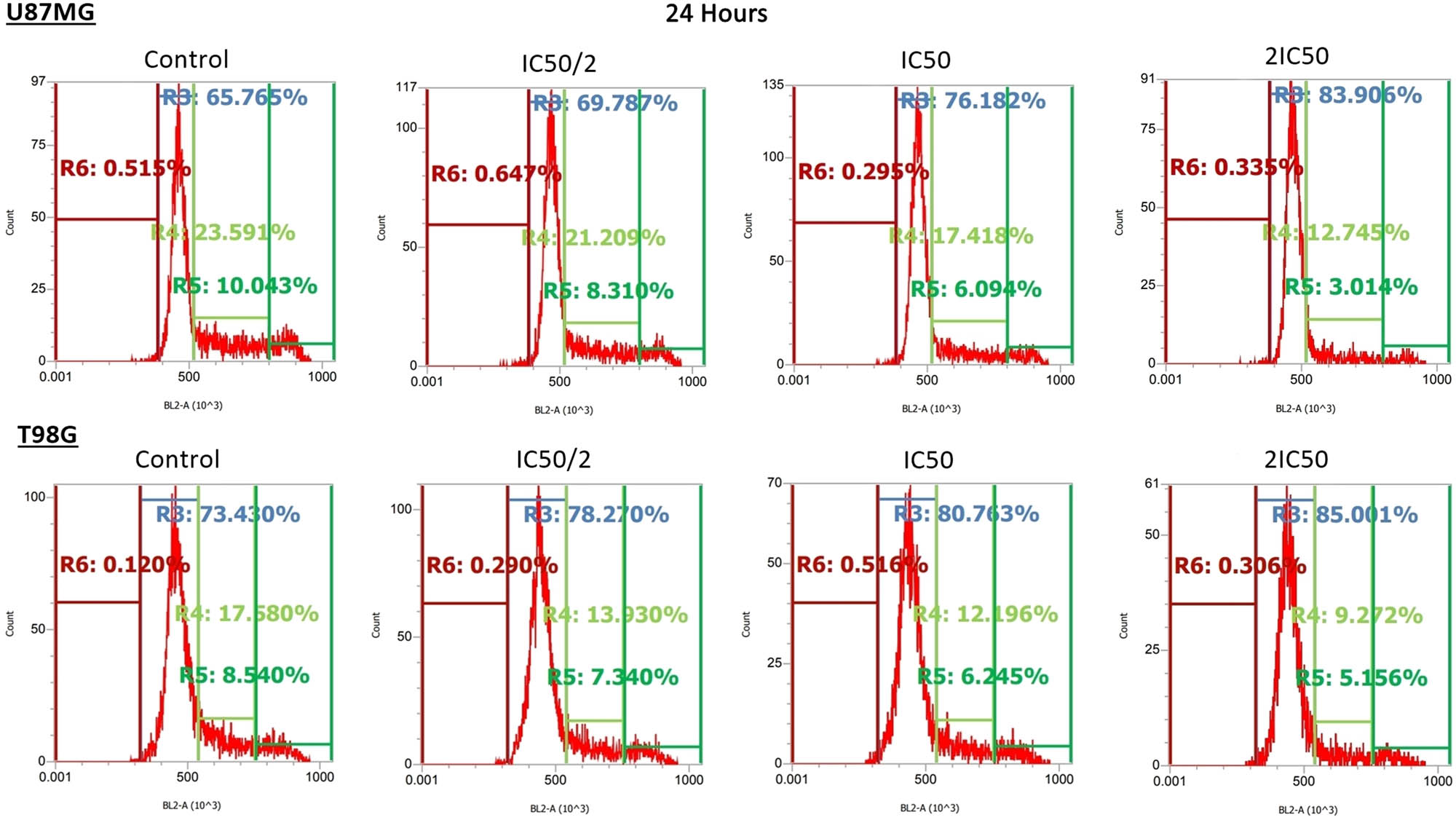

The mechanism of the TMF effect was evaluated by examining its impact on the cell cycle. Flow cytometry assessed the potential of a specific cell cycle phase disruption at 24 h, while the effect of TMF on cell death was examined at 72 h since the optimum time to assess cell death is after the compound has been administered for a few days. Cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase was observed in both cell lines (Figure 4, Tables 1 and 2).

Effect of TMF on the cell cycle of U87MG and T98G cells after 24 h of incubation. TMF was added in concentrations of IC50/2, IC50, and 2IC50 for each cell line. Each curve in the graphs corresponds to a stage of the cell cycle and is symbolized by the letter R. Specifically, the R3 region corresponds to the G0/G1 phase, R4 to S phase, R5 to G2/M phase, and R6 to sub-G0/G1. Also for each stage, the percentage of cells found in it is indicated. An increase in the percentage of cells in R3 and a decrease in the remaining phases was observed.

Cell cycle distribution in U87MG cells, after the effect of TMF in different concentrations, for t = 24 h

| Treatment | G0/G1 | S | G2/M | Sub-G0/G1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 65.93 ± 1.5 | 22.28 ± 1.2 | 10.86 ± 1.3 | 0.58 ± 0.3 |

| 39 μM | 68.84 ± 1.3 | 22.21 ± 1.4 | 8.33 ± 0.03 | 0.56 ± 0.1 |

| 78 μM | 75.24 ± 1.2* | 18.12 ± 1.6* | 6.21 ± 0.4* | 0.38 ± 0.1 |

| 156 μM | 82.37 ± 1.4* | 13.29 ± 0.7* | 3.98 ± 0.8* | 0.33 ± 0.05 |

-

Cells’ percentage at the G0/G1 phase was greater than that at the other phases; this indicated the cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase. An increase in this percentage was also observed at higher doses of TMF, going from 65.93 to 82.37%. No significant changes were noticed at the other phases.

-

*Statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

Cell cycle distribution in T98G cells, after the effect of TMF in different concentrations, for t = 24 h

| Treatment | G0/G1 | S | G2/M | Sub-G0/G1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 75.41 ± 2.7 | 16.52 ± 1.7 | 7.6 ± 1 | 0.16 ± 0.07 |

| 15.25 μM | 79.12 ± 0.8 | 13.07 ± 0.7* | 7.27 ± 0.6 | 0.30 ± 0.2 |

| 30.5 μM | 80.46 ± 1.4* | 12.34 ± 1.1* | 6.36 ± 0.6 | 0.52 ± 0.2* |

| 61 μM | 84.19 ± 0.9* | 9.93 ± 0.6* | 5.47 ± 0.4* | 0.23 ± 0.08 |

-

Cells’ percentage at the G0/G1 phase was greater than that at the other phases; this indicated the cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase. An increase in this percentage was also observed at higher doses of TMF, going from 75.41 to 84.19%. No significant changes were noticed at the other phases.

-

*Statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

Mean values from the independent experiments performed in each cell line are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, expressed as (%) percentage. In each case, the SD has been calculated, and statistically significant results (p < 0.05) have been marked with an asterisk.

Regarding TMF’s impact on cell death, after 72 h of incubation, no remarkable change in the percentage of U87MG cells in the sub-G0/G1 phase was observed. On the contrary, in T98G cells, there was a very slight rise (around 2%) from control to TMF concentration equal to 2× IC50 (Tables 3 and 4).

Cell cycle distribution in U87MG cells, after the effect of TMF in different concentrations, for t = 72 h

| Treatment | G0/G1 | S | G2/M | Sub-G0/G1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 80.48 ± 0.8 | 8.61 ± 2.1 | 10.46 ± 2 | 0.35 ± 0.2 |

| 39 μM | 85.27 ± 2.3* | 6.91 ± 2.2 | 7.58 ± 0.5* | 0.15 ± 0.05 |

| 78 μM | 85.82 ± 2.8* | 6.50 ± 1.8 | 7.35 ± 2.6 | 0.16 ± 0.06 |

| 156 μM | 89.30 ± 1.3* | 5.21 ± 1.9 | 5.24 ± 1* | 0.21 ± 0.05 |

-

Cells’ percentage was still higher at the G0/G1 phase, while at the sub-G0/G1 phase there was no significant change.

-

*Statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

Cell cycle distribution in T98G cells, after the effect of TMF in different concentrations, for t = 72 h

| Treatment | G0/G1 | S | G2/M | Sub-G0/G1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 90.41 ± 3.1 | 5.50 ± 1.3 | 3.02 ± 2 | 0.73 ± 0.3 |

| 15.25 μM | 84.22 ± 4* | 8.71 ± 1.3* | 5.97 ± 2.9 | 0.69 ± 0.3 |

| 30.5 μM | 86.38 ± 3.9 | 6.98 ± 1 | 4.67 ± 2.9 | 1.54 ± 0.6 |

| 61 μM | 86.10 ± 3.7 | 7.26 ± 1.1 | 3.32 ± 1.8 | 2.87 ± 1.1* |

-

Cells’ percentage was still higher at the G0/G1 phase.

-

*Statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

Mean values from the independent experiments performed for each cell line are summarized in Tables 3 and 4, expressed as (%) percentage. In each case, the SD has been calculated, and statistically significant results (p < 0.05) were marked with an asterisk.

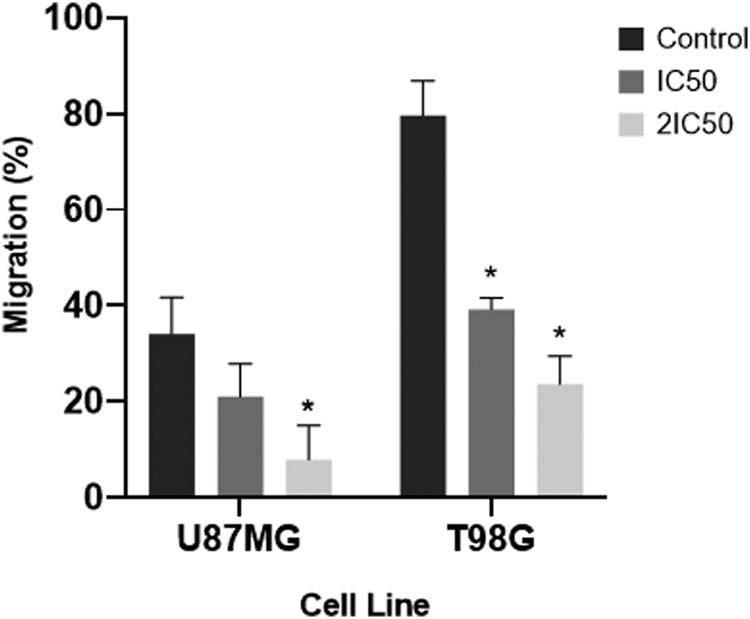

TMF acts as an anti-migratory agent

To investigate if TMF could affect the migration of U87MG and T98G cancer cells, a 72-h artificial wound-healing procedure was used. Control samples were compared with samples that had been treated with the TMF, and the percentages of migration were calculated for each cell line. For U87MG cells, the percentage of wound healing in the control group was 34.06%. This percentage decreased to 20.97% after treatment with 78 μM (IC50) TMF, and it decreased even further to 7.86% at a TMF concentration of 156 μM (2IC50). This reduction was even greater for T98G cells, as the wound healing rate was 79.6% in control, while at TMF concentrations of 30.5 μM (IC50) and 61 μM (2IC50), this percentage decreased to 39.2 and 23.6%, respectively. These percentages also appear in Figure 5.

Migration rates of U87MG and T98G cells after treatment with TMF. The x-axis represents the two cell lines, while the y-axis represents their migration rate in the different concentrations of the compound. Error bars indicate SDs in each case, and asterisks indicate statistically significant results p < 0.05.

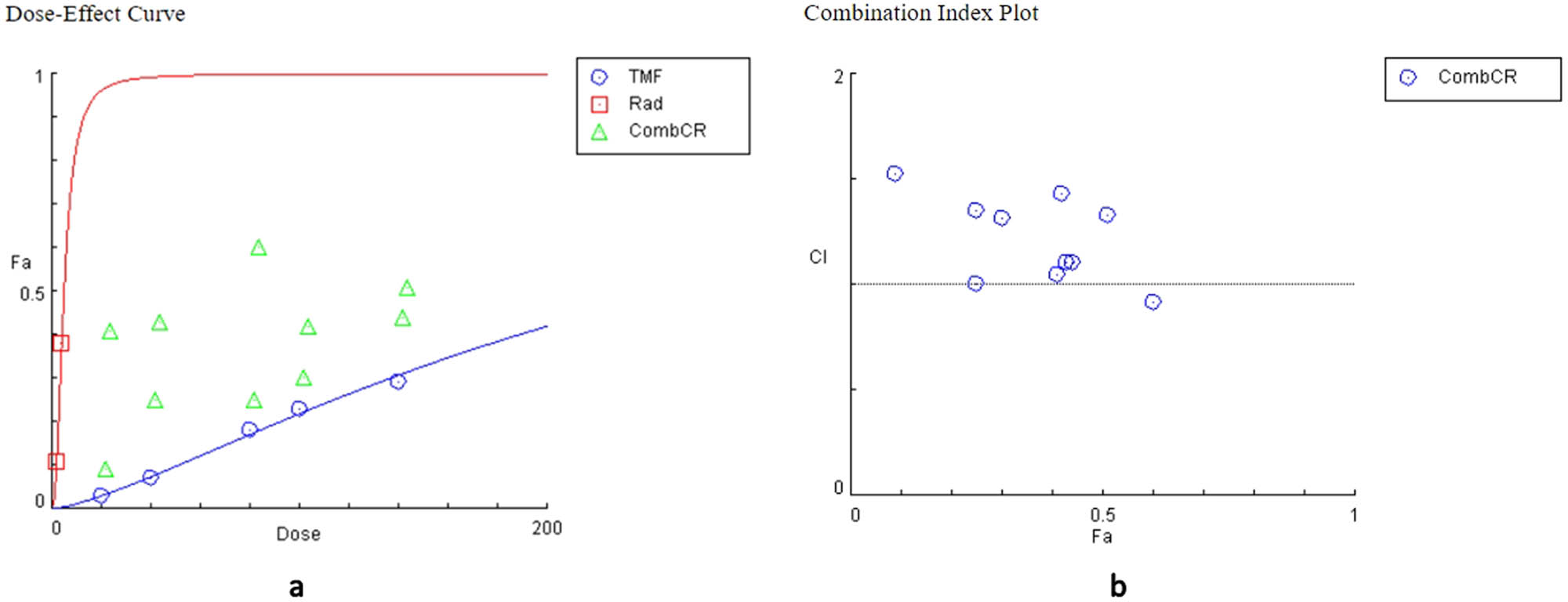

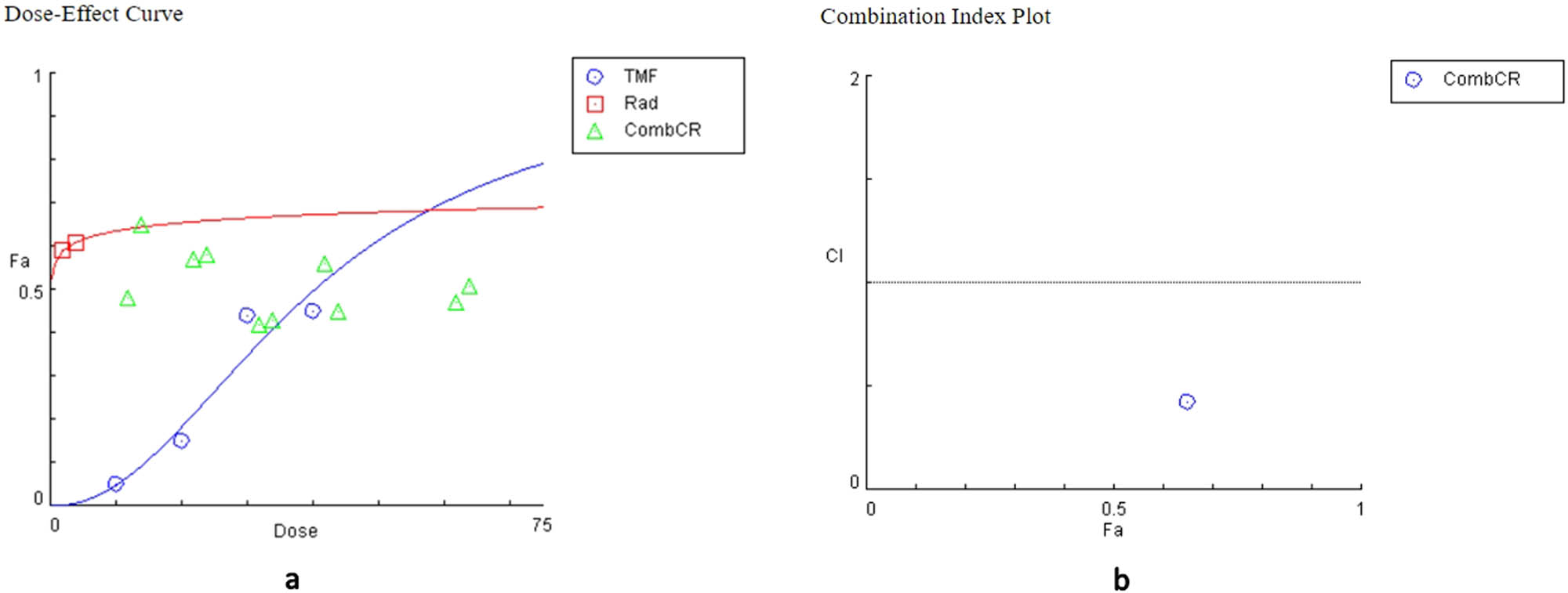

Combined action of TMF and radiation on GBM cells

Various combinations of TMF and radiation were used to assess whether or not these treatments may present a synergistic effect. Specifically, the TMF ranged in concentrations of 20–140 μM for U87MG and 10–60 μM for T98G cells. Radiation was given in doses of 2 or 4 Gy. CompuSyn software was used to calculate the CI index, which determined the relationship between the two treatments. Most combinations for both cell lines demonstrated an antagonistic association between TMF and radiation. Except for a single instance of synergy in both cell lines and two cases of additive effect. These results are summarized in Tables 5 and 6.

Evaluation of the combined effects of TMF and radiation in U87MG cells

| TMF (μM) | Radiation (Gy) | Effect | CI | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 2 | 0.09 | 1.52789 | Antagonism |

| 40 | 2 | 0.25 | 1.00253 | Additive effect |

| 80 | 2 | 0.25 | 1.35421 | Antagonism |

| 100 | 2 | 0.3 | 1.31571 | Antagonism |

| 140 | 2 | 0.44 | 1.10760 | Antagonism |

| 20 | 4 | 0.41 | 1.04998 | Additive effect |

| 40 | 4 | 0.43 | 1.10784 | Antagonism |

| 80 | 4 | 0.6 | 0.91360 | Synergism |

| 100 | 4 | 0.42 | 1.42961 | Antagonism |

| 140 | 4 | 0.51 | 1.33159 | Antagonism |

-

The effect denotes cellular death and ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no cellular death and 1 depicts complete cellular death. CI < 1 represents synergism, CI = 1 additivity, and CI > 1 represents an antagonistic behavior.

Evaluation of the combined effects of TMF and radiation in T98G cells

| TMF (μM) | Radiation (Gy) | Effect | CI | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2 | 0.48 | 40.4054 | Antagonism |

| 20 | 2 | 0.57 | 2.41548 | Antagonism |

| 30 | 2 | 0.42 | 303.103 | Antagonism |

| 40 | 2 | 0.56 | 3.66523 | Antagonism |

| 60 | 2 | 0.47 | 57.6171 | Antagonism |

| 10 | 4 | 0.65 | 0.42596 | Synergism |

| 20 | 4 | 0.58 | 3.24476 | Antagonism |

| 30 | 4 | 0.43 | 430.955 | Antagonism |

| 40 | 4 | 0.45 | 220.054 | Antagonism |

| 60 | 4 | 0.51 | 31.0509 | Antagonism |

-

The effect denotes cellular death and ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no cellular death and 1 depicts complete cellular death. CI < 1 represents synergism, CI = 1 additivity, and CI > 1 represents an antagonistic behavior.

The relationship of TMF and radiation was also represented graphically through the dose–effect curve and the combination index diagram, which were derived from the CompuSyn software (Figures 6 and 7).

Plots from the combination of TMF and radiation in U87MG cells. (a) Dose–effect curve: the action of the TMF is represented in blue, the action of radiation in red, and their combined action in green. (b) Combination index diagram: values below the horizontal line, which corresponds to value 1, indicate synergy, while the values above the horizontal line indicate antagonism.

Plots from the combination of TMF and radiation in T98G cells. (a) Dose–effect curve: the action of the TMF is represented in blue, the action of radiation in red, and their combined action in green. (b) Combination index diagram: values below the horizontal line, which corresponds to value 1, indicate synergy, while the values above the horizontal line indicate antagonism.

Discussion

In recent years, many beneficial effects have been discovered from natural compounds. Anticancer properties are one of the most important characteristics of several natural compounds. These effects have been attributed to a variety of mechanisms. Inhibition of cell proliferation, inhibition of migration, oncogene silencing, reactive oxygen species generation, apoptotic pathway activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction are only some of them [37,38]. Moreover, natural compounds, especially flavonoids, phenolic acids, and stilbenes, have displayed positive effects on neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. This effect might be possibly attributed to antioxidant activity and prevention of protein misfolding and chronic inflammation [39].

In the present study, the anticancer effect of a natural agent was tested in GBM, the most frequent malignant primary brain tumor in adults [40]. GBM is a difficult-to-treat tumor. So far, surgery is the main therapeutic approach, along with radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant chemotherapy [5]. TMZ is a widely used chemotherapeutic drug against GBM with a modest therapeutic effect. Tumor recurrence is almost universal within a few months post-surgery [8,9].

Herewith, we tested TMF, a flavone, for its possible anti-glioma effect. The anticancer properties of this compound and some of its isoforms have been evaluated in previous studies [19,20,21,23,24]. TMF can be isolated from various natural plants; in the present study, the plant C. bruguieriana subsp. belangeriana was the source of TMF.

The effect of TMF against GBM cells in vitro was significant. Specifically, it induced the death of GBM cells at low IC50 concentrations (78 μM for U87MG cells and 30.5 μM for T98G cells), indicating that a high dose of the drug is not necessary to provide the desired effect. Thus, if future studies demonstrate low toxicity in animal models, it may be considered for further evaluation and development as a possible antitumor agent against GBM. In flow cytometry experiments, cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase was seen after TMF administration. This might explain the reduced viability of cancer cells. TMF also prevented the migration of cells, especially in the T98G cell line, which also represents a desirable property for an anti-glioma agent.

The combination of TMF with radiation turned out to be antagonistic. In both tested cell lines, the CI index was greater than 1, in most combinations, which can be interpreted as antagonism. As shown above, TMF arrested the cell cycle in the G0/G1 phase, while radiation inhibited the cell cycle in the G2/M phase [41]. The two therapies affected the cells’ cycle in a distinguished different ways. These opposite approaches resulted in a situation where pharmacological treatment competed with radiation.

Using combination therapy could have beneficial, neutral, or harmful results [42]. There are several other potential mechanisms contributing to the antagonism of concomitant use of chemotherapy and radiation in GBM cells. Thus, due to the diversity of cancer cells, radiation can activate both pro-apoptotic and pro-survival signaling pathways [6]. In addition, previous studies have shown that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling can exert an antagonistic effect between chemotherapy and radiotherapy, when they are administered sequentially in GBM cells [6,43]. Increased EGFR signaling, caused by either radiation or chemotherapy, activates downstream pathways, such as rat sarcoma virus (RAS), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). These pathways finally lead to the expression of factors that can cause resistance to the other treatment approach [43]. Nuclear factor kB (NF-kB) has been found to be activated in some cases of combined therapy. It regulates cell apoptosis and protects the cancer cells from the negative effects of radiation [44]. Another potential mechanism of resistance in combination therapy is the regulation of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) gene family members [44]. Tο determine the exact cause of antagonism between TMF and radiation, further studies must be done, and it would be very helpful if they focus on the exact mechanism of both TMF and radiation in cells and molecular pathways. This would not only help to predict the therapeutic relationship between these two, but also to find ways that could prevent this.

Regarding the BBB, there is no published literature to support that TMF crosses BBB since the cytotoxic activity of TMF has only been studied in other non-brain types of cancer. However, its low molecular weight and hydrophobic nature are two very important and encouraging characteristics, which could potentially allow TMF to cross that barrier. Studies show that only highly hydrophobic molecules with upper molecular weight 500 kDa can pass through BBB [45].

In summary, this study is the first to indicate an encouraging anti-glioma effect of TMF. Our results show that this natural compound can inhibit cell proliferation, cause a G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, and reduce the cells’ migratory capacity. Also, the significant reduction of collected cells, in the T98G cell line, during flow cytometry indicates the possibility of necrosis at higher concentrations of the TMF. This could be concluded from the absence of a sub-G0/G1 population, as well as the lack of indication of autophagy. Due to the absence of previous studies on TMF as a GBM treatment, comparison and confirmation of the results were not possible. Although our current results are quite encouraging, more studies need to proceed in order to clarify the exact molecular pathways that are modified by the action of TMF. Finally, GBM growth mechanism is different in the human brain compared to GBM cell lines. This fact highlights the need for animal experiments before clinical trials.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Esemen Y, Awan M, Parwez R, Baig A, Rahman S, Masala I, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of glioblastoma in adults and future perspectives: A systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Feb;23(5):2607. 10.3390/ijms23052607. PMID: 35269752; PMCID: PMC8910150.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Levin VA, Maor MH, Thall PF, Yung WK, Bruner J, Sawaya R, et al. Phase II study of accelerated fractionation radiation therapy with carboplatin followed by vincristine chemotherapy for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995 Sep;33(2):357–64. 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00160-Z. PMID: 7673023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Thakur A, Faujdar C, Sharma R, Sharma S, Malik B, Nepali K, et al. Glioblastoma: Current status, emerging targets, and recent advances. J Med Chem. 2022 Jul;65(13):8596–685. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01946. Epub 2022 Jul 5. PMID: 35786935; PMCID: PMC9297300.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Groves MD, Maor MH, Meyers C, Kyritsis AP, Jaeckle KA, Yung WK, et al. A phase II trial of high-dose bromodeoxyuridine with accelerated fractionation radiotherapy followed by procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine for glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999 Aug;45(1):127–35. 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00122-4. PMID: 10477016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Hanif F, Muzaffar K, Perveen K, Malhi SM, Simjee SU. Glioblastoma multiforme: A review of its epidemiology and pathogenesis through clinical presentation and treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017 Jan;18(1):3–9. 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.1.3. PMID: 28239999; PMCID: PMC5563115.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Kargiotis O, Geka A, Rao JS, Kyritsis AP. Effects of irradiation on tumor cell survival, invasion and angiogenesis. J Neurooncol. 2010 Dec;100(3):323–38. 10.1007/s11060-010-0199-4. Epub 2010 May 7. PMID: 20449629.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Kyritsis AP, Levin VA. An algorithm for chemotherapy treatment of recurrent glioma patients after temozolomide failure in the general oncology setting. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011 May;67(5):971–83. 10.1007/s00280-011-1617-9. Epub 2011 Mar 27. PMID: 21442438.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Jiapaer S, Furuta T, Tanaka S, Kitabayashi T, Nakada M. Potential strategies overcoming the temozolomide resistance for glioblastoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2018 Oct;58(10):405–21. 10.2176/nmc.ra.2018-0141. Epub 2018 Sep 21 PMID: 30249919; PMCID: PMC6186761.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Tomar MS, Kumar A, Srivastava C, Shrivastava A. Elucidating the mechanisms of Temozolomide resistance in gliomas and the strategies to overcome the resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021 Dec;1876(2):188616. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188616. Epub 2021 Aug 20. PMID: 34419533.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Kondraganti S, Mohanam S, Chintala SK, Kin Y, Jasti SL, Nirmala C, et al. Selective suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in human glioblastoma cells by antisense gene transfer impairs glioblastoma cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2000 Dec;60(24):6851–5. PMID: 11156378.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Kyritsis AP, Bondy ML, Levin VA. Modulation of glioma risk and progression by dietary nutrients and antiinflammatory agents. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(2):174–84. 10.1080/01635581.2011.523807. PMID: 21302177; PMCID: PMC3047463.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Zoi V, Galani V, Vartholomatos E, Zacharopoulou N, Tsoumeleka E, Gkizas G, et al. Curcumin and radiotherapy exert synergistic anti-glioma effect in vitro. Biomedicines. 2021 Oct;9(11):1562. PMID: 34829791; PMCID: PMC8615260.10.3390/biomedicines9111562Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Zoi V, Galani V, Lianos GD, Voulgaris S, Kyritsis AP, Alexiou GA. The role of curcumin in cancer treatment. Biomedicines. 2021 Aug;9(9):1086. 10.3390/biomedicines9091086. PMID: 34572272; PMCID: PMC8464730.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Sarkar FH, Li Y, Wang Z, Kong D. Cellular signaling perturbation by natural products. Cell Signal. 2009 Nov;21(11):1541–7. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.03.009. Epub 2009 Mar 16. PMID: 19298854; PMCID: PMC2756420.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Huang M, Lu JJ, Ding J. Natural products in cancer therapy: Past, present and future. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2021 Feb;11(1):5–13. 10.1007/s13659-020-00293-7. Epub 2021 Jan 3 PMID: 33389713; PMCID: PMC7933288.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Panche AN, Diwan AD, Chandra SR. Flavonoids: An overview. J Nutr Sci. 2016 Dec;5:e47. 10.1017/jns.2016.41. PMID: 28620474; PMCID: PMC5465813.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Khanavi M, Rajabi A, Behzad M, Hadjiakhoondi A, Vatandoost H, Abaee MR. Larvicidal activity of Centaurea bruguierana ssp. belangerana against Anopheles stephensi Larvae. Iran J Pharm Res. 2011 Fall;10(4):829–33. PMID: 24250419; PMCID: PMC3813082.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Noman OM, Herqash RN, Shahat AA, Ahamad SR, Mechchate H, Almoqbil AN, et al. A phytochemical analysis, microbial evaluation and molecular interaction of major compounds of Centaurea bruguieriana using HPLC- spectrophotometric analysis and molecular docking. Appl Sci. 2022 Mar;12(7):3227. 10.3390/app12073227.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Lone SH, Bhat KA, Naseer S, Rather RA, Khuroo MA, Tasduq SA. Isolation, cytotoxicity evaluation and HPLC-quantification of the chemical constituents from Artemisia amygdalina Decne. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013 Dec;940:135–41. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.09.027. Epub 2013 Sep 27 PMID: 24148842.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Nasseri S, Delnavazi MR, Shirazi FH, Mojab F. Cytotoxic activity and phytochemical analysis of Artemisia haussknechtii Boiss. Iran J Pharm Res. 2022 Apr;21(1):e126917. 10.5812/ijpr-126917. PMID: 36060921; PMCID: PMC9420210.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Seo JM, Kang HM, Son KH, Kim JH, Lee CW, Kim HM, et al. Antitumor activity of flavones isolated from Artemisia argyi. Planta Med. 2003 Mar;69(3):218–22. 10.1055/s-2003-38486. PMID: 12677524.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Liu R, Choi HS, Ko YC, Yun BS, Lee DS. 5-Desmethylsinensetin isolated from Artemisia princeps suppresses the stemness of breast cancer cells via Stat3/IL-6 and Stat3/YAP1 signaling. Life Sci. 2021 Sep;280:119729. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119729. Epub 2021 Jun 16. PMID: 34146553.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Polatoğlu K, Karakoç OC, Demirci F, Gökçe A, Gören N. Chemistry and biological activities of Tanacetum chiliophyllum var. oligocephalum extracts. J AOAC Int. 2013 Nov–Dec;96(6):1222–7. 10.5740/jaoacint.sgepolatoglu. PMID: 24645497.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Sudha A, Srinivasan P, Kanimozhi V, Palanivel K, Kadalmani B. Antiproliferative and apoptosis-induction studies of 5-hydroxy 3’,4’,7-trimethoxyflavone in human breast cancer cells MCF-7: an in vitro and in silico approach. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2018 Jun;38(3):179–90. 10.1080/10799893.2018.1468780. Epub 2018 May 8. PMID: 29734849.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Stahl E. Thin-layer chromatography. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1969.10.1007/978-3-642-88488-7Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Neu R. Chelate von DiarylborsaurenmitaliphatischenOxyalkylaminenalsReagenzien fur den Nachweis von Oxyphenyl-benzo-γ-pyronen. Die Naturwissenchaften. 1957;44:181–3.10.1007/BF00599857Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Hou YZ, Chen KK, Deng XL, Fu ZL, Chen DF, Wang Q. Anti-complementary constituents of Anchusa italica. Nat Prod Res. 2017;31(21):2572–4.10.1080/14786419.2017.1320789Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Alexiou GA, Tsamis KI, Vartholomatos E, Peponi E, Tzima E, Tasiou I, et al. Combination treatment of TRAIL, DFMO and radiation for malignant glioma cells. J Neurooncol. 2015 Jun;123(2):217–24. 10.1007/s11060-015-1799-9. Epub 2015 May 3. PMID: 25935110.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Strober W. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2015 Nov;111:A3.B.1–3. 10.1002/0471142735.ima03bs111. PMID: 26529666; PMCID: PMC6716531.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Leverkus M. Crystal violet assay for determining viability of cultured cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2016 Apr;2016(4):pdb.prot087379. 10.1101/pdb.prot087379. PMID: 27037069.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Chondrogiannis G, Kastamoulas M, Kanavaros P, Vartholomatos G, Bai M, Baltogiannis D, et al. Cytokine effects on cell viability and death of prostate carcinoma cells. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:536049. 10.1155/2014/536049. Epub 2014 May 29. PMID: 24982891; PMCID: PMC4058150.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] McKinnon KM. Flow cytometry: An overview. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2018 Feb;120:5.1.1–11. 10.1002/cpim.40 PMID: 29512141; PMCID: PMC5939936.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: A convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(2):329–33. 10.1038/nprot.2007.30 PMID: 17406593.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Alexiou GA, Vartholomatos E, Tsamis KI, Peponi E, Markopoulos G, Papathanasopoulou VA, et al. Combination treatment for glioblastoma with temozolomide, DFMO and radiation. J Buon. 2019 Jan–Feb;24(1):397–404. PMID: 30941997.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70:440–6. PMID: 20068163.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Ashton JC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method--letter. Cancer Res. 2015 Jun;75(11):2400. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3763 PMID: 25977339.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Asma ST, Acaroz U, Imre K, Morar A, Shah SRA, Hussain SZ, et al. Natural products/bioactive compounds as a source of anticancer drugs. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Dec;14(24):6203. 10.3390/cancers14246203 PMID: 36551687; PMCID: PMC9777303.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Hashem S, Ali TA, Akhtar S, Nisar S, Sageena G, Ali S, et al. Targeting cancer signaling pathways by natural products: Exploring promising anti-cancer agents. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Jun;150:113054. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113054. Epub 2022 Apr 30. PMID: 35658225.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Sharifi-Rad M, Lankatillake C, Dias DA, Docea AO, Mahomoodally MF, Lobine D, et al. Impact of natural compounds on neurodegenerative disorders: From preclinical to pharmacotherapeutics. J Clin Med. 2020 Apr;9(4):1061. 10.3390/jcm9041061 PMID: 32276438; PMCID: PMC7231062.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Kaba SE, Kyritsis AP. Recognition and management of gliomas. Drugs. 1997 Feb;53(2):235–44. 10.2165/00003495-199753020-00004 PMID: 9028743.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Pawlik TM, Keyomarsi K. Role of cell cycle in mediating sensitivity to radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004 Jul;59(4):928–42. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.03.005 PMID: 15234026.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Sauter ER. Cancer prevention and treatment using combination therapy with natural compounds. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020 Mar;13(3):265–85. 10.1080/17512433.2020.1738218. Epub 2020 Apr 3. PMID: 32154753.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Chakravarti A, Chakladar A, Delaney MA, Latham DE, Loeffler JS. The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway mediates resistance to sequential administration of radiation and chemotherapy in primary human glioblastoma cells in a RAS-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2002 Aug;62(15):4307–15. PMID: 12154034.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Yount GL, Haas-Kogan DA, Levine KS, Aldape KD, Israel MA. Ionizing radiation inhibits chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in cultured glioma cells: implications for combined modality therapy. Cancer Res. 1998 Sep;58(17):3819–25. PMID: 9731490.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Parodi A, Rudzińska M, Deviatkin AA, Soond SM, Baldin AV, Zamyatnin AA Jr. Established and emerging strategies for drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier in brain cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2019 May;11(5):245. 10.3390/pharmaceutics11050245. PMID: 31137689; PMCID: PMC6572140.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Antitumor activity of 5-hydroxy-3′,4′,6,7-tetramethoxyflavone in glioblastoma cell lines and its antagonism with radiotherapy

- Digital methylation-specific PCR: New applications for liquid biopsy

- Synergistic effects of essential oils and phenolic extracts on antimicrobial activities using blends of Artemisia campestris, Artemisia herba alba, and Citrus aurantium

- β-Amyloid peptide modulates peripheral immune responses and neuroinflammation in rats

- A novel approach for protein secondary structure prediction using encoder–decoder with attention mechanism model

- Diurnal and circadian regulation of opsin-like transcripts in the eyeless cnidarian Hydra

- Withaferin A alters the expression of microRNAs 146a-5p and 34a-5p and associated hub genes in MDA-MB-231 cells

- Toxicity of bisphenol A and p-nitrophenol on tomato plants: Morpho-physiological, ionomic profile, and antioxidants/defense-related gene expression studies

- Review Articles

- Polycystic ovary syndrome and its management: In view of oxidative stress

- Senescent adipocytes and type 2 diabetes – current knowledge and perspective concepts

- Seeing beyond the blot: A critical look at assumptions and raw data interpretation in Western blotting

- Biochemical dynamics during postharvest: Highlighting the interplay of stress during storage and maturation of fresh produce

- A comprehensive review of the interaction between COVID-19 spike proteins with mammalian small and major heat shock proteins

- Exploring cardiovascular implications in systemic lupus erythematosus: A holistic analysis of complications, diagnostic criteria, and therapeutic modalities, encompassing pharmacological and adjuvant approaches

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Antitumor activity of 5-hydroxy-3′,4′,6,7-tetramethoxyflavone in glioblastoma cell lines and its antagonism with radiotherapy

- Digital methylation-specific PCR: New applications for liquid biopsy

- Synergistic effects of essential oils and phenolic extracts on antimicrobial activities using blends of Artemisia campestris, Artemisia herba alba, and Citrus aurantium

- β-Amyloid peptide modulates peripheral immune responses and neuroinflammation in rats

- A novel approach for protein secondary structure prediction using encoder–decoder with attention mechanism model

- Diurnal and circadian regulation of opsin-like transcripts in the eyeless cnidarian Hydra

- Withaferin A alters the expression of microRNAs 146a-5p and 34a-5p and associated hub genes in MDA-MB-231 cells

- Toxicity of bisphenol A and p-nitrophenol on tomato plants: Morpho-physiological, ionomic profile, and antioxidants/defense-related gene expression studies

- Review Articles

- Polycystic ovary syndrome and its management: In view of oxidative stress

- Senescent adipocytes and type 2 diabetes – current knowledge and perspective concepts

- Seeing beyond the blot: A critical look at assumptions and raw data interpretation in Western blotting

- Biochemical dynamics during postharvest: Highlighting the interplay of stress during storage and maturation of fresh produce

- A comprehensive review of the interaction between COVID-19 spike proteins with mammalian small and major heat shock proteins

- Exploring cardiovascular implications in systemic lupus erythematosus: A holistic analysis of complications, diagnostic criteria, and therapeutic modalities, encompassing pharmacological and adjuvant approaches