Polycystic ovary syndrome and its management: In view of oxidative stress

-

Koushik Bhattacharya

, Rajen Dey

Abstract

In the past two decades, oxidative stress (OS) has drawn a lot of interest due to the revelation that individuals with many persistent disorders including diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), cardiovascular, and other disorders often have aberrant oxidation statuses. OS has a close interplay with PCOS features such as insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism, and chronic inflammation; there is a belief that OS might contribute to the development of PCOS. PCOS is currently recognized as not only one of the most prevalent endocrine disorders but also a significant contributor to female infertility, affecting a considerable proportion of women globally. Therefore, the understanding of the relationship between OS and PCOS is crucial to the development of therapeutic and preventive strategies for PCOS. Moreover, the mechanistic study of intracellular reactive oxygen species/ reactive nitrogen species formation and its possible interaction with women’s reproductive health is required, which includes complex enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems. Apart from that, our current review includes possible regulation of the pathogenesis of OS. A change in lifestyle, including physical activity, various supplements that boost antioxidant levels, particularly vitamins, and the usage of medicinal herbs, is thought to be the best way to combat this occurrence of OS and improve the pathophysiologic conditions associated with PCOS.

Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a common gynecological and endocrine disorder causing infertility. It involves recurrent anovulation and elevated androgen levels, with diagnostic criteria set by the Rotterdam Consensus Criteria in 2003 [1,2,3]. PCOS exhibits diverse clinical symptoms such as irregular menstrual cycles; amenorrhea; abnormal hormone levels; excess hair growth; and acne, obesity, and fertility issues. It is linked to hyperandrogenism (HA), chronic inflammation, oxidative stress (OS), and insulin resistance (IR), although precise mechanisms are not fully elucidated [2,3,4,5,6,7]. PCOS is recognized as a chronic systemic disorder, supported by studies revealing elevated OS markers such as malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) in individuals with PCOS. There is a strong association between PCOS and factors such as obesity, insulin resistance (IR), hyperandrogenism (HA), and chronic inflammation, all linked to increased OS levels. However, it remains uncertain whether PCOS directly causes abnormal OS levels or whether they result from related factors [4,8,9,10]. PCOS is linked to a heightened risk of malignant conditions, including endometrial, breast, and ovarian cancers [11,12]. The increased risk of endometrial cancer in PCOS is attributed to factors such as altered hormonal environment, IR, hyperinsulinemia, and obesity, as suggested by multiple studies [13,14,15]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) intrusion can cause DNA damage in various forms, including strand breaks, point mutations, and abnormal cross-linking [16]. Compromised DNA repair systems in the presence of OS may lead to mutations in tumor suppressor genes and proto-oncogenes, fostering uncontrolled cell proliferation [17,18]. Additionally, OS may downregulate tumor suppressor genes through DNA methylation, suggesting a substantial role in the increased incidence of gynecological malignancies, such as those observed in PCOS patients [19].

Definition, diagnostic criteria, and neuroendocrine basis of PCOS

In 2003, the Rotterdam criteria were collaboratively established by members of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology and the American Society fof Reproductive Medicine (ESHRE/ASRM) [3]. These criteria resulted in the creation of three distinct definitions of PCOS that remain widely utilized today. The Rotterdam criteria are widely acknowledged by scientific associations and health authorities as the primary classification system for PCOS [3,11,12]. Diagnosis according to these criteria requires the presence of at least two out of three clinical features: HA (clinical and/or biochemical), abnormal or irregular ovulation, and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) [3]. In 2006, the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AE-PCOS) introduced additional criteria, stating that HA must be a requirement for diagnosis. This criterion must be accompanied by indications of abnormal and/or irregular ovulation, such as ovulatory dysfunction and/or the presence of PCOM [13,14]. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development previously utilized criteria for PCOS diagnosis that excluded the assessment of ovarian morphology [14]. Instead, it focused on HA and abnormal or irregular ovulation [15]. Both the Rotterdam and AE-PCOS classifications, which include ovarian morphology assessment, are significant in PCOS research. Despite potential differences in the impact of various androgen excess forms, they all consider the presence of clinical and/or biochemical HA. Additionally, all three classifications require the exclusion of conditions with overlapping symptoms, such as non-classical congenital hyperplasia, hyperprolactinemia, abnormal thyroid function, hypercortisolism, and androgen-secreting tumors [13,15]. Ongoing debates surround the validity of diagnosing PCOS in women with PCOM and ovulatory dysfunction but without evident clinical or biochemical androgen excess, highlighting conflicting criteria [15]. Shifting focus from specific diagnostic criteria to evaluating susceptibility to health risks associated with various PCOS symptoms and phenotypes may aid in resolving these disagreements. The diverse pathogenesis and clinical severity of PCOS suggest that not all patients exhibit the full spectrum of symptoms or are exposed to the same adverse features [16]. PCOS entails clinical implications, with androgen excess potentially causing infertility and endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma. Persistent oligomenorrhea also poses a risk of endometrial issues. Isolated PCOM is linked to an increased risk of an exaggerated response to ovarian hormones during ovulation induction [17]. PCOS manifests in various clinical phenotypes, ranging from the most severe, classic phenotype characterized by both HA and oligo-ovulation, to the least severe non-hyperandrogenic phenotype involving oligo-ovulation and PCOM [18]. The second most severe phenotype is ovulatory PCOS, marked by HA and PCOM, but it does not meet the criteria for PCOS according to the AE-PCOS statement [13,14].

PCOS is a complex disorder associated with IR and metabolic dysfunction. The classic PCOS phenotype, as opposed to ovulatory PCOS or the non-hyperandrogenic phenotype, shows a stronger association with IR. While the classic PCOS group may have slightly lower levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) [20], they typically do not exhibit metabolic dysfunction. The etiology of PCOS is considered multifactorial, characterized by symptoms such as irregular ovulation, HA, and PCOM. Diagnosis is crucial, excluding other conditions such as hyperprolactinemia, Cushing syndrome, adrenal hyperplasia, and androgen-secreting tumors [3]. PCOS is defined by several clinical features, considering both menstrual irregularities (oligo/anovulation) and ovarian dysfunction (OD); clinically confirmed HA involves the presence of hirsutism, acne, and male pattern baldness; PCOM is identified through ultrasound examination, revealing multiple follicles and increased ovarian mass; biochemical anomalies include elevated free testosterone, increased anti-mullerian hormone levels, IR, and an elevated luteinizing hormone (LH): follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio. PCOS is also associated with conditions such as obesity, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular issues, infertility, childbirth difficulties, and enduring psychological distress such as anxiety and tension.

Besides national institutes of health (NIH), AE-PCOS, and NIH criteria, the International PCOS Network criteria represent a recent evidence-based approach for diagnosing and managing PCOS [21]. These criteria highlight the comprehensive assessment of reproductive, metabolic, cardiovascular, dermatologic, sleep, and psychological aspects. The emphasis is on developing a lifelong reproductive health strategy, addressing preconception risk factors, adopting a healthy lifestyle, preventing weight gain, and optimizing fertility. PCOS is associated with increased risks of metabolic factors, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), underscoring the importance of regular screening and appropriate management. During pregnancy, PCOS is recognized as a high-risk condition, requiring careful identification and monitoring. While there is an elevated risk of endometrial cancer in PCOS before menopause, the absolute risks remain relatively low. The prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms is higher in women with PCOS, necessitating screening and psychological evaluation when warranted. Recognizing psychological aspects, including eating disorders, and addressing their impact on body image and overall quality of life are crucial. Dissatisfaction with PCOS diagnosis and management highlights the need for increased awareness and education for both women and healthcare professionals. Effective care is promoted through shared decision-making, self-empowerment, and the development, funding, and evaluation of integrated care models [21]. Various diagnostic criteria listed in Table 1 have been suggested and utilized by healthcare professionals for PCOS diagnosis, and each of these criteria relies on several other influencing factors.

Different diagnostic criteria of PCOS and their comparisons

| NIH, 1990 [14] | ESHRE/ASRM [3] | AE-PCOS [13,14] | NIH, 2012 [22] | International PCOS Network criteria [21] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | HA, OA | HA, OD, PCOM | HA, OD, or PCOM | HA, OD, PCOM | Evidence based |

| Phenotypes | HA + OA |

|

|

|

Various diagnostic criteria listed in Table 1 have been suggested and utilized by healthcare professionals for PCOS diagnosis, and each of these criteria relies on several other influencing factors.

The hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis is a crucial component of the reproductive system, involving the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and gonads. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from hypothalamic neurons stimulates the release of gonadotropins (LH and FSH) from the pituitary, regulating gametogenesis and sex hormone production. Sex steroids, including estrogen, progestin, and androgens, maintain balance within the HPG axis and regulate secondary sexual traits. The HPG axis becomes active during puberty, triggered by factors such as leptin release from adipocytes, along with influences from social, environmental, and genetic factors [23,24,25]. Following puberty, GnRH continues to stimulate gonadotropic cells in the anterior pituitary, leading to the increased secretion of the gonadotropins FSH and LH. Regulatory signals influencing GnRH release include temperature, light, blood glucose levels, metabolic activity, and mental health considerations [26]. Both LH and FSH, produced by a single gonadotropin cell, are stored in different granules within the anterior pituitary, with LH release dependent on pulsatile GnRH secretion [26]. GnRH, the primary regulator of sexual development and pregnancy in mammals, has three main subtypes, with GnRH I and II being expressed in mammals. While GnRH II affects sexual behavior, GnRH I serves as a neuromodulator in addition to regulating gonadotropins. The hypothalamus, housing approximately 1,500 GnRH neurons, releases the pulse and surge of GnRH, with synchronized action representing the pulse mode of release [24]. LH pulses occur concurrently with GnRH pulses, typically with an hour’s interval between pulses in an individual. The synchronization among GnRH neurons is facilitated by the GnRH pulse generator [27], crucial for normal reproduction and gonadotropin function. The pattern of GnRH release, with quick pulses favoring LH elevation and slower pulses resulting in increased FSH release, plays a pivotal role. In the presence of LH, theca cells produce androstenedione, which can be converted into estrone or testosterone in granulose cells (GCs). Enzymes such as 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and aromatase further convert estrone and testosterone into estradiol and estriol. Alternatively, testosterone can be converted into 5-alpha-dihydrotestosterone (DHT). FSH impact on GCs regulates these conversion processes [28,29]. Estradiol, crucial for the follicular phase development, increases FSH receptor expression, enhances GC sensitivity to FSH, and acts as negative feedback on FSH release [29]. As estradiol levels rise, positive feedback on the hypothalamus triggers a significant GnRH increase, leading to LH release and ovulation [30]. In PCOS, IR-induced elevated insulin secretion may increase GnRH pulse frequency, altering the LH/FSH ratio, impacting theca and GCs, hindering follicular growth, and impeding ovulation [6].

What is OS?

Free radicals, characterized by their high reactivity and instability, strive to achieve stability by acquiring electrons from various molecules such as nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nearby substances. This process leads to cellular damage [31]. These radicals exist in two primary forms: ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). During normal metabolic pathways, free electrons are produced as by-products, leading to the generation of ROS when oxygen undergoes reduction [32]. The main source of mitochondrial ROS production occurs within complexes I and III of the electron transport chain (ETC). This process involves the conversion of ubiquinol to ubiquinone and then to ubiquinone [33]. While generating chemical energy and undergoing lipolysis, approximately 98% of the inhaled oxygen undergoes full reduction, while the remaining 2% is only partially reduced, resulting in the formation of three distinct types of ROS [33]. ROS primarily consists of three main types: superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. Superoxide is generated when there is electron leakage at the ETC. Although molecular oxygen is typically converted to water at complex IV, during ATP production, electrons may acquire an extra electron along the ETC [33]. Hydrogen peroxide, on the other hand, is produced either through superoxide dismutation or by oxidase enzymes. Among these ROS types, hydroxyl radicals are the most reactive due to their possession of three additional electrons. They have the potential to cause DNA strand breakage and damage by altering purines and pyrimidines. When there is an imbalance in the ratio of antioxidants to oxidants, it can lead to modifications in key transcription factors, ultimately impacting gene expression [31,32,34]. SOD 2, located within the mitochondria, plays a crucial role in converting the superoxide radical into hydrogen peroxide. Subsequently, GPx further transforms hydrogen peroxide into water [35]. To maintain redox equilibrium, antioxidants are indispensable. A decrease in the levels of antioxidants required to counteract the generation of ROS can lead to cellular damage [34,35].

Role of OS in PCOS

Due to the redox imbalance, OS has become a matter of concern over the past two decades. PCOS is one of the several pathological conditions that arises by the disparity between the production and elimination of ROS and RNS. Within the RNS group, nitric oxide (NO) and its by-products are included, while the ROS category comprises the superoxide radical, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radical. Some ROS can act as signaling molecules to cells. Due to their unstable and highly reactive nature, peroxides and free radicals have the potential to damage various cellular components, with DNA damage having particularly concerning long-term consequences [31,34,35]. OS is believed to be a potential triggering factor in the pathophysiology of PCOS. Numerous studies indicate that individuals with PCOS tend to exhibit higher OS levels compared to control groups. Nonetheless, outcomes frequently differ, primarily because of the use of diverse markers and disparities in how even the same marker is evaluated, which is contingent on the origin and research approach. Moreover, the relationship between OS and the development of PCOS is not always straightforward, as several clinical symptoms of PCOS, such as HA, obesity, and IR, may contribute to the emergence of both local and systemic OS. This, in turn, can potentially exacerbate these metabolic abnormalities [36]. Obese individuals exhibited notably elevated levels of several molecular markers including oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), and advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP), and MDA. In contrast, two indicators of antioxidant activity, SOD and GPx, were significantly lower in obese individuals [37]. However, it is important to note that obesity likely contributes to OS in PCOS [37]. Furthermore, non-obese women with PCOS displayed higher levels of OS markers than healthy controls, even when obese patients were excluded based on body mass index (BMI) [31]. IR is another significant factor that influences OS in women with PCOS. This is driven by the generation of ROS, which is triggered by hyperglycemia and elevated levels of free fatty acids. Conversely, OS may play a significant role in the development of IR, a phenomenon often referred to as OS-induced IR. Numerous studies have revealed that exposure to OS diminishes insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, and protein synthesis. However, the precise mechanism behind this effect is not yet fully understood [38]. Increased OS triggers the activation of various protein kinases, which, in turn, leads to serine or threonine phosphorylation instead of the typical tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate (IRS). As a result, the IRS’s capability to attach to the insulin receptor is reduced, and its effectiveness in triggering the downstream enzyme phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is inhibited. Moreover, an improper phosphorylation can lead to the degradation of IRS. OS can activate inflammatory signaling pathways such as IκB kinase (IKK)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase pathways, which can result in IR through post-insulin receptor dysfunction [35]. On the other hand, antioxidants are a class of compounds capable of mitigating the detrimental effects of free radicals. Antioxidants can be categorized into two groups: enzymatic (including SOD, catalase (CAT), GPx, glutathione reductase, and paraoxonase 1) and non-enzymatic (comprising glutathione (GSH), alpha-tocopherol, ascorbate, and beta-carotene). These antioxidants have been demonstrated to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of female infertility and the female reproductive system [39,40,41].

Various investigations into markers of OS in individuals diagnosed with PCOS have consistently displayed significant differences between PCOS patients and their control group counterparts. These findings provide valuable insights into the complex cross-talk between OS and PCOS, underscoring the significance of comprehending OS dynamics within the context of this condition. While several individual studies have reported substantial differences, it is worth noting that this specific meta-analysis did not identify disparities in NO levels, GPx activity, or total antioxidant capacity between PCOS patients and control women [4]. Nevertheless, previous research has, indeed, noted an increase in various antioxidative enzymes. For instance, a recent study observed a significant elevation in CAT and SOD activity, emphasizing the potential role of an internal stress-compensatory mechanism [42]. These variations in antioxidative enzyme activity further contribute to our understanding of the multifaceted relationship between OS and PCOS. Efforts have been made to explore the potential therapeutic benefits of antioxidants in addressing the pathophysiological aspects of PCOS. This approach stems from the significant imbalance observed in the redox balance of the individuals having PCOS, as highlighted by a substantial body of research. Furthermore, recent studies utilizing animal models of PCOS and IR have shown promising results when employing mitochondria-targeted antioxidants. These interventions have demonstrated the potential to ameliorate both PCOS and IR in the context of PCOS conditions [43,44].

Links between OS and various clinical features of PCOS

Inflammation

When the cellular immune system encounters endogenous or exogenous antigens, it triggers the production of ROS and RNS. This initiates signaling cascades that lead to the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [6,45]. In response to pathogens or other stimuli, the primary immune system reaction is inflammation, aimed at restoring cells to their normal state or replacing damaged tissue with scar tissue [46,47]. Activated innate immune system cells release cytokines and chemokines that promote the generation of ROS and RNS [48]. The innate immune system’s ability to eliminate pathogens relies on the production of ROS by macrophages, including superoxide, NO, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, peroxynitrite, and hypochlorous acid [49]. The inflammatory response continues until the pathogens are eliminated, and the tissue repair process is completed [6,43,44].

An ongoing and excessive production of ROS by inflammatory cells can lead to a sustained inflammatory response, potentially resulting in cell damage or hyperplasia. Within mitotic cells, ROS can interact with DNA, leading to point mutations, gene deletions, or gene rearrangements that may bring about permanent changes to the genome [50]. In response to the heightened generation of free radicals during inflammation, cellular antioxidant systems activate DNA repair genes [31]. However, chronic inflammation can deplete these cellular antioxidants, leading to a higher rate of ROS-induced DNA damage in such conditions. Chronic inflammation, by repeatedly inducing DNA damage and increasing the frequency of mutations, makes cells more susceptible to transformation [43,44]. Additionally, chronic inflammation stimulates the production of growth factors and other molecules that promote cell growth, further facilitating cellular malignancy and transformation [43,44]. These observations highlight the significant role of chronic inflammation as a key initiator in the development of cancer. Therefore, it is essential to discuss the role of inflammatory cytokines in the production of free radicals to gain a better understanding of the link between chronic inflammation and the presence of ROS in tissues. Cytokines act as the soluble mediators of intracellular communication, controlling processes such as hematopoiesis, inflammation, development, tissue repair, and immune responses, both specific and general [51]. When cytokines bind to their receptors, they initiate a chemical signaling language that conveys extracellular information into the cytoplasm and nucleus [51]. Typically, cytokine receptors are directly linked to ion channels or G proteins, and various signaling pathways, including nuclear factor B and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), are engaged to transmit this information [52]. Several cytokines are known to induce the production of ROS in nonphagocytic cells through interactions with their specific receptors. The well-known growth factor receptors such as the platelet-derived growth factor receptor, the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and the epidermal growth factor receptor have been implicated in ROS generation [53,54]. This process highlights the intricate role of cytokines in regulating ROS production and its broader impact on cellular signaling and function.

Studies have demonstrated that nonphagocytic cells are also capable of generating ROS when exposed to inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF)-α, and Interferon‐gamma (IFN-γ) [6,55,56]. The ROS generated as a result of cytokine induction can serve as a significant signal for various cellular processes, including proliferation and programmed cell death [6]. For instance, TNF-α enhances the production of ROS in neutrophils, while IL-1-β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ stimulate the expression of iNOS in inflammatory and epithelial cells, respectively [6,55,56,57]. Inflammatory macrophages upregulate cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), leading to the stimulation of IL-6 production through prostaglandin E2. This process can be effectively halted by anti-inflammatory medications [58]. Activated macrophages serve as the primary source of TNF secretion, a notable inflammatory cytokine that triggers ROS production in various cell types. Studies involving the knockout of TNF-α have demonstrated a substantial decrease in the development of skin tumors when exposed to 7,12-dimethylbenz(a) anthracene [59]. Monocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells are responsible for generating the inflammatory chemokine IL-8, which plays a pivotal role in tumor angiogenesis. Its influence on various cancer types, including colon, bladder, lung, and stomach cancers, has also been explored [60,61].

There is an ongoing debate regarding the potential involvement of inflammation in the underlying factors of various chronic diseases. However, it is well established that numerous inflammatory cytokines and chemokines play a significant role in female reproductive processes such as the release of ovum from the ovary, folliculogenesis, sperm–egg fusion, embryo attachment to the uterus, and gestational phase [62,63]. While the exact origin of PCOS remains unclear, a mounting body of evidence suggests that chronic, mild inflammation is a significant factor in this condition. Women suffering from PCOS are more prone to experience an ongoing proinflammatory condition, which is probably associated with IR, CVD, and various other clinical symptoms and outcomes linked to PCOS [64]. When examining the correlation between PCOS and chronic inflammation, it is crucial to take into account the impact of an elevated body mass index (BMI) on individuals exhibiting upregulated inflammatory markers. Additionally, it is worth noting that metabolic syndrome (MS) shares similarities with PCOS in terms of low-grade chronic inflammation [6]. The presence of a proinflammatory state could be a significant contributor to the pathophysiology of both conditions and may explain their frequent co-occurrence. Women with PCOS have a higher likelihood of having MS, and conversely, women with MS often exhibit endocrine and reproductive characteristics resembling those of PCOS. Adipose tissue of the viscera is a crucial factor in that connection. It is more widespread and biologically active in both conditions, leading to a cycle of elevated free fatty acids and the excessive release of various substances, including some with inflammatory properties [1,64]. Nonetheless, the observation that women with PCOS and a lower BMI display elevated inflammation levels compared to healthy individuals with a greater BMI, which implies that chronic low-grade inflammation is not exclusively linked to increased body weight [65]. The connection between chronic inflammation and elevated androgen levels in PCOS presents a similar level of uncertainty. It is unclear whether androgen excess associated with PCOS leads to a pro-inflammatory state or whether inflammatory molecules stimulate an increase in ovarian androgen production and the development of hyperandrogenemia. The influence of androgens on the expression of various proteins and enzymes leads to the hypertrophy of adipocytes. Furthermore, the HA associated with PCOS heightens the sensitivity of mononuclear cells to ingest glucose, promoting their activation. This discussion brings up another crucial concept in PCOS, i.e., inflammation triggered by dietary factors. Studies indicate that both glucose consumption in vivo and exposure to glucose in vitro elicit an inflammatory reaction by stimulating mononuclear cells to release IL-6 and TNF-α [66,67]. Moreover, research has demonstrated that women with PCOS exhibit higher levels of TNF and IL-6 in their follicular fluid (FF), along with macrophage infiltration in ovarian tissue. One could propose that the introduction of mononuclear cells into polycystic ovaries provokes a localized inflammatory reaction, triggering the activation of an ovarian steroidogenic enzyme (CYP17) that is responsible for androgen production. This validates a self-perpetuating cycle, demonstrating that inflammation could independently stimulate the release of androgens, and the surplus of androgens can, in turn, induce inflammation by increasing adipocyte hypertrophy and mononuclear cell responsiveness to ingested glucose [66,67]. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a commonly employed marker of inflammation, primarily produced by the liver as an acute-phase protein. Increasing evidence suggests that CRP has significant functions in defending the host against infections and inflammatory mechanisms. These roles include involvement in reactive NO production, phagocytic activity, apoptosis, activation of complement pathway, and the production of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF [6]. Kelly et al. conducted a study that marked a pivotal moment by revealing increased serum CRP levels in women with PCOS. They identified a significant contrast between the CRP levels of healthy women and PCOS patients who exhibited typical menstrual cycles and androgen levels. Furthermore, their pioneering work suggested that chronic low-grade inflammation might play a role in elevating the risk of CVD and type 2 diabetes in those women [68]. These findings opened the way for several subsequent studies. The presence of elevated serum CRP levels has become a common occurrence in women with PCOS, irrespective of obesity [65]. Numerous research studies have investigated the influence of diverse treatment methods on CRP levels. Importantly, metformin was demonstrated to notably lower CRP levels in a range of treatment regimens [69,70]. Furthermore, recent investigations have highlighted that statins or even increased physical activity alone can substantially decrease CRP levels in women affected by PCOS [71,72,73].

Women with PCOS showed significantly elevated serum levels of TNF and IL-6, even after adjusting for other conventional inflammatory markers. Additionally, ovarian tissue from individuals with PCOS had a greater presence of macrophages and lymphocytes compared to those without the condition. The secretion of TNF and IL-6 by lymphocytes and macrophages further stimulated the production of cytokines by other lymphocytes and macrophages [6,66,67]. TNF, in particular, seems to hold significance in various clinical manifestations of PCOS. It was observed that TNF-α-induced inflammatory responses and androgen excess in PCOS women are due to the upregulated Δ4 (progesterone) pathway and restricted Δ5 (dehydroepiandrosterone) testosterone biosynthesis pathway [74]. It is a widely recognized inflammatory factor, and substantial evidence suggests its pivotal involvement in the generation of androgens, IR, and obesity [74,75]. It is a multifunctional hormone-like polypeptide with various physiological functions, many of which are directly related to the ovaries, such as regulating ovarian function and having an impact on follicular proliferation, differentiation, and maturation, besides those on steroidogenic and apoptotic events [76,77,78]. In a 2016 meta-analysis involving 29 studies and a total of 1,960 women (including 1,046 with PCOS and 914 controls), significantly elevated levels of TNF were observed in women with PCOS compared to healthy controls [79]. The analysis also indicated a correlation between high serum TNF levels, IR, and androgen excess, while there was no association with BMI. In obese individuals, the primary source of the increased TNF in PCOS is thought to be adipose tissue, but it remains uncertain in lean women with this condition [80,81,82,83,84]. The significance of TNF in PCOS is highlighted not only by its elevated systemic levels but also by its presence in FF. Variations in FF TNF concentrations have been linked to oocyte quality in women undergoing in vitro fertilization, impacting fertilization rates, embryonic development, and pregnancy outcomes [76]. Furthermore, IL-18, a proinflammatory cytokine previously associated with PCOS, stimulates the TNF production, primarily by macrophages involved in cell-mediated immunity. Research findings indicate that TNF levels are elevated even in PCOS patients with a lean body mass and are associated with a heightened risk of IR and CVD [85,86].

TNF plays a role in stimulating the production of two other critical cytokines, IL-6 and IL-8. IL-8 primarily originates from macrophages and monocytes and serves as a key regulator of the immune response. While IL-6 has been extensively studied in the context of PCOS and is closely associated with IR and CVD, research into IL-8 in PCOS is comparatively limited. Reports suggest a strong correlation between elevated IL-6 levels and obesity. Interestingly, if IR and body mass were reduced in PCOS patients, IL-6 levels decreased. Certain studies have shown significantly elevated levels of IL-6 in the case of PCOS compared to controls. Additionally, a recent report revealed that augmented IL-6 levels were related to PCOS, and higher serum IL-6 concentration was associated with IR as well as androgen levels, but not with BMI [6]. In summary, IL-6 production appears to be linked to immune interactions among PCOS individuals with IR, and lipopolysaccharide-activated monocytes release significantly more IL-6 in the PCOS group [67].

IL-10 and the IL-1 family represent two critical sets of cytokines that have been extensively investigated in the context of PCOS. IL-10 is a noteworthy anti-inflammatory cytokine known for its role in controlling inflammation and immune responses [87]. In contrast, the IL-1 family comprises 11 cytokines primarily associated with innate immunity and proinflammatory responses. Within this family, IL-1 and IL-1, along with their endogenous receptor antagonist, are encoded by the closely related genes IL-1, IL-1, and IL-1RN, located within the IL-1 gene cluster on chromosome 2. While various studies have suggested the importance of IL-1 in ovarian inflammatory mechanisms, IL-1 has been the primary focus of previous PCOS research. It is likely to influence the prostaglandin production through its impact on COX-2 synthesis and promotes the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-12 [88]. Although there is very little information regarding the relationship between free fatty acids or arachidonic acid (AA) derivatives and PCOS, COX-mediated prostaglandins and AA metabolite levels are found to be higher in the ovarian tissues of PCOS women. It was also reported that elevated COX-2 level is associated with ovulation failure and infertility. Additionally, higher levels of 9-hydroxyoctadecadiene acid (HODE)/13-HODE were considered to be an important marker in PCOS patients. An increased expression of 15-LOX-1,2 ultimately leads to an increase in the production of AA and linoleic acid (LA) derivatives, such as hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids and HODE [89].

Obesity

Obesity can be classified as visceral (central) obesity and peripheral (lower body) obesity. Obesity is now a prevalent endocrine disorder globally. BMI serves as a reliable and practical tool for screening obesity, accurately assessing adiposity without the complexities of other approaches [90]. Anthropometric data, which include BMI, are trustworthy methods for assessing the physical condition of a population [90]. In recent years, waist circumference (WC), waist-to-height ratio, waist-to-hip ratio, and sometimes wrist circumference have become more reliable parameters for assessing obesity compared to BMI [1,91].

To evaluate a population’s nutritional status, both body composition and morphometric characteristics are considered. Typically, body composition is assessed to estimate the percentage of body fat. Abdominal fat deposition is considered the most atherogenic, diabetogenic, and hypertensiogenic fat deposition in the human body, despite the presence of fat in other areas [92]. Recent studies have employed these parameters to investigate central or abdominal obesity [1,91]. Women who are overweight face potential risks during pregnancy, reduced productivity, delayed recovery from illnesses, and increased susceptibility to infections, and interestingly, most of the PCOS individuals are usually affected by obesity [93]. Additionally, abdominal obesity is often assessed using the simple and reliable criteria of WC in clinical settings [1]. Globally, about 40 to 80% of PCOS women, regardless of racial or cultural differences, tend to exhibit abdominal obesity as a common feature of obesity [1,94]. Abdominal obesity is frequently considered a prevalent consequence of PCOS. While BMI is a common clinical measure for assessing obesity, up to 50% of PCOS individuals with a normal BMI may still have abdominal obesity [94]. Therefore, in evaluating the relationship between obesity and PCOS, both BMI and WC should be taken into account.

It is anticipated that OS levels are higher in obese individuals [6], and strong connections between OS markers and obesity parameters such as BMI and WC have been established [1]. When compared to those with normal weight, obese individuals exhibit significantly elevated quantitative measures of markers indicating biomolecule peroxidation, including AOPP, MDA, thiobarbituric reactive substances (TBARS), and ox-LDL. Conversely, the quantitative measures of markers can also reflect the presence of oxidative inhibitors, such as GPx. The obesity-related syndrome is a substantial pathophysiological event associated with numerous chronic diseases. Moreover, a significantly lower GSH concentration was related to obese individuals [95], with systemic OS levels remaining significantly higher in obese women, even in the absence of smoking, high blood glucose, high blood pressure, altered lipid profiles, liver and kidney dysfunction, and history of tumors. Obesity is linked to increased OS, and this holds for PCOS patients as well [96,97]. Therefore, PCOS itself is directly linked to elevated OS levels, in addition to abdominal obesity [6]. However, factors other than fat are believed to contribute to the heightened oxidative status observed in PCOS. BMI may exclude obese individuals; however, women with PCOS who are not obese still undergo more pronounced OS compared to women without PCOS. Even when excluding PCOS individuals with abdominal obesity, as opposed to peripheral obesity, this outcome remains consistent, indicating that while obesity is a significant contributing factor, it is not the sole cause of the elevated OS levels in PCOS.

Insulin resistance

IR is a physiological condition where cells do not respond properly to insulin, leading to impaired glucose uptake and utilization [98]. It is commonly assessed using the euglycemic clamp technique, although the homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) is widely used as a cost-effective alternative due to its strong correlation with the euglycemic clamp [1]. In PCOS, the primary underlying factor is believed to be IR, with IR rates in PCOS patients ranging from 50 to 70% [99]. Markers of IR in PCOS patients, such as homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), are significantly elevated compared to healthy individuals and are often strongly associated with markers of OS [100]. A recent investigation conducted over 125 PCOS patients (aged 18–40 years) revealed that HOMA-IR index was positively correlated with triglyceride (TG) levels, diastolic blood pressure, and free androgen index, and negatively linked with SHBG in obese PCOS women [101]. IR promotes OS because hyperglycemia and increased levels of free fatty acids lead to the production of ROS [19]. Several reducing metabolites, such as pyruvic acid and acetyl coenzyme A, reach the mitochondria for oxidation when cells take in extra glucose or free fatty acids. This increases ETC activity and single electron transfer, which, in turn, leads to the higher formation of ROS [102]. OS may arise if reducing enzymes such as CAT, peroxidase, and SOD are unable to eliminate excess ROS [31]. During IR, OS is exacerbated, as indicated by increased protein carbonyl, non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs), MDA, and decreased GSH, among other factors [31,103]. While IR is frequently associated with obesity and is found in roughly half of obese individuals, it is regarded as one of the principal mechanisms through which obesity contributes to OS [96]. Weight loss in individuals with a BMI of 25 or higher has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reducing fasting insulin (FINS) levels [104,105]. However, the link between OS and IR remains strong, regardless of weight [104]. OS is known to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of IR, even though the precise mechanism by which OS induces IR is not fully understood [106,107]. Studies have reported that OS inhibits insulin-induced metabolic pathways in cellular models such as L6 myotubes and 3T3-L1 adipocytes [108,109]. Exposure to H2O2 for 2 hours has been shown to suppress protein synthesis while stimulating glycogen synthesis and glucose uptake [110]. Oxygen radicals significantly influence glucose control [109]. For example, H2O2 can modulate the insulin signaling pathway and insulin release in glucose-activated cells [110]. For the development of IR, the IRS is typically the central component [111]. OS can lead to IRS serine/threonine phosphorylation, causing IRS to degrade and become an inhibitor of the INSR kinase [112]. OS may also activate insulin signaling pathways, primarily through the inflammatory signaling pathway via NF-κB and stress-activated protein kinases/jun amino-terminal kinases signaling, potentially resulting in IR due to post-insulin receptor dysfunction [109]. In PCOS, the alternative IR is believed to be driven by post-insulin receptor malfunction in insulin signaling [113]. Additionally, the production of sex hormones is enhanced when IR is used as an alternative to glycometabolism in PCOS [114]. PCOS women exhibit lower levels of IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation but significantly higher serine phosphorylation in IRS-1 in their adipocytes and serum [112]. Adipose tissue and granulosa cells have lower levels of IRS-1, while PCOS theca cells have higher levels. Adipocytes and serum from PCOS individuals may contain an increased quantity of active extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2, along with decreased levels of the insulin receptor, GLUT4, and PI3K [115,116]. OS and IR are intricately connected, with OS potentially being the main inducer of IR in PCOS through post-insulin receptor malfunction [113]. Studies on antioxidants such as vitamin E, alpha-lipoic acid (ALA), and N-acetylcysteine have shown a promise in improving insulin sensitivity, offering novel therapeutic strategies for IR [95,117,118]. Thus, IR is undoubtedly associated with PCOS; OS may function as a contributing factor; and regardless of BMI or IR, OS remains elevated in PCOS.

Hyperandrogenism

Hyperandrogenism is a defining characteristic of PCOS, and about 60–80% of women with this condition have elevated androgen levels [119]. It is believed to be the primary cause of PCOS, as animal models of PCOS can be created by administering excessive androgens [120]. The main driver of elevated androgen levels in PCOS is IR, which results from compensatory hyperinsulinemia [1,6,121]. Insulin has a direct stimulating effect on ovarian androgen secretion and can also enhance the action of LH on androgen production [6,122,123]. Additionally, insulin may reduce the production of SHBG and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein 1 from hepatocytes and intensify GnRH-induced LH pulses, making free IGF-1 more available and promoting androgen synthesis [124,125,126].

While both OS and inflammation contribute to androgen excess in PCOS, the precise interactions between these factors are not well understood due to limited research on the topic. Several studies have reported a positive correlation between androgen levels and markers of OS and inflammation in PCOS patients [6,19,127,128]. Antioxidative substances, such as statins, have been found to reduce the activity of ovarian steroidogenic enzymes in vitro, while OS was observed to increase their activity [129,130]. TNF-α has been shown to stimulate the growth of mesenchymal cells in the follicular membrane and androgen production in rodent models [131].

Both women and female animals with PCOS appear to be susceptible to OS, IR, and HA. Elevated levels of body weight, TG, NEFAs, FINS, fasting blood glucose (FBG), HOMA-IR, and revised OS markers like MDA, GSH, and SOD are common in PCOS models induced by excess androgens [19]. Testosterone administration has been linked to increased ROS levels in leukocytes, upregulation of the p47 (phox) gene, and higher plasma TBARS levels, all indicative of OS [132]. This inflammation caused by HA is mediated by NF-kB [6,10]. Testosterone administration has been associated with increased NF-kB expression and phosphorylation, and higher IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production by adipocytes, but these effects were mitigated by NF-kB inhibitors [133].

Interestingly, testosterone may also protect tissues or cells from oxidative damage and inflammation. In obese PCOS patients, BMI, FFA, IL-6 levels, and CRP levels increased, while androgen levels consistently decreased in response to a GnRH agonist [6]. Testosterone has been shown to accelerate hormone-sensitive lipase activity, promoting lipolysis and inhibiting adipose tissue formation. This suggests that testosterone may have an anti-inflammatory role by encouraging lipolysis, limiting adipose tissue growth, and reducing the synthesis of inflammatory mediators [134,135]. DHT may enhance the expression of forkhead box protein O1 and SOD 2, increasing cells’ resistance to OS [136]. These findings suggest that the effects of androgens can vary depending on the dosage and the cellular environment.

Possible management protocol

Treatment of PCOS should be suggested not just to reduce symptoms but also to stop the development of long-term consequences. The mainstay of therapy to lower androgen levels and manage symptoms is the combination of oral contraceptives and antiandrogens [137]. However, the treatment strategy should be customized based on the patient’s wish (or lack thereof) to become pregnant, the requirement for an aesthetic approach, and the presence of concurrent metabolic changes. The main objectives of PCOS therapy for women are to handle metabolic disorders, reduce risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus and CVDs, regulate hyperandrogenic symptoms, plan and achieve a safe pregnancy if chosen, and generally improve the quality of life.

Physical activity and diet plan

Exercise training plays a significant role in the management of PCOS, benefiting both healthcare practitioners and patients. Physical activity improves insulin sensitivity by enhancing glucose transport and metabolism, leading to better insulin sensitivity [138]. The intensity of exercise influences the degree of improvements in various physical parameters. Strenuous exercise, such as vigorous aerobic exercise for a minimum of 120 min per week and resistance training, is beneficial for addressing insulin sensitivity and androgen levels in women with PCOS [139]. Exercise often leads to increased oxygen consumption, which can produce excess ROS [140]. However, relaxation techniques based on yoga have been linked to reduced oxygen consumption and are effective in reducing OS parameters [141]. Yoga can help normalize endocrine parameters and improve fertility capacity, making it beneficial for reducing the risk of PCOS [142,143]. It is important to note that physical activity alone may not be sufficient to address this endocrine-related gynecological condition. Proper dietary modifications are also crucial. Lifestyle changes, such as reducing the calorie content of the diet, adopting a low-glycemic index (low-GI) diet with lower calories, and focusing on low-GI meals, can significantly impact PCOS management. Low-GI diets have been found to reduce FINS, cholesterol levels, TGs, WC, and total testosterone without affecting other parameters such as fasting glucose and weight [144,145]. Combining a low-GI diet with exercise and/or omega-3 supplementation further enhances its effects, promoting fat reduction, high-density lipoprotein synthesis, and other positive outcomes including increased SHBG availability in circulation [146]. Saturated fatty acid (SFA) consumption has been associated with the genesis of inflammatory conditions, making the removal of SFAs from the diet crucial for PCOS patients. ALA from sources such as flaxseed oil can have positive effects on PCOS, and soluble dietary fiber can impact the gut flora by promoting the production of short-chain fatty acids [147]. A low-GI diet affects hunger-regulating hormones, reducing ghrelin secretion, and increasing glucagon release [148,149]. High fructose consumption can exacerbate hormonal abnormalities in PCOS, making expert nutritional guidance essential for PCOS patients [150,151]. A ketogenic diet (KD), which restricts total carbohydrate intake in favor of plant-based fats, has shown a promise for managing PCOS. It can improve the menstrual cycle, blood glucose levels, body weight, and liver function, and treat fatty liver in obese women with PCOS [152]. KD also impacts various parameters related to PCOS, including insulin levels, hormonal profiles, and body composition [153]. In summary, adhering to a healthy diet and incorporating exercise can help regulate physiological homeostasis and achieve faster recovery in individuals with PCOS.

Use of antioxidants and other supplements

ALA stands out as a highly potent natural antioxidant, which is well acknowledged in research [154]. Its oxidized and reduced forms both demonstrate the capability to scavenge free radicals, an essential quality that makes LA a crucial cofactor in the pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme complex, categorizing it within the metabotropic antioxidant group [155,156]. Furthermore, LA plays a significant role in enhancing the functioning of the glucose transporter 4 (GLUT-4), resulting in a reduction in blood glucose levels [157]. The combined use of ALA and other therapies has proven effective in lowering circulating TG levels and altering the distribution of low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Additionally, the euglycemic–hyperinsulinemic clamp approach has unveiled a notable improvement in insulin sensitivity [158]. In the context of patients with PCOS, ALA supplementation has demonstrated its ability to substantially reduce hyperinsulinemia and the IR index. Moreover, it has been found to restore menstrual regularity, enhance ovarian function, and normalize ovarian volume in these individuals [159]. Moreover, ALA has shown a promise in reducing metabolic disturbances, particularly among individuals with diabetes, especially those with a family history, who may be at a higher risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic issues [158]. It is suggested that ALA could be a viable option for addressing PCOS and hyperinsulinemia in obese individuals who also suffer from liver conditions such as cirrhosis, hepatitis, and decompensated steatosis. ALA has demonstrated effectiveness in preventing issues such as atherosclerosis and chronic liver damage in PCOS patients, irrespective of their weight status [158,159]. Recent research has also explored the combined administration of LA and inositol for PCOS patients. It has also been observed that ALA could act as a potent antioxidant at a certain dose only but overuse may decrease the activity of thyroid hormones and create a homeostatic and hormonal imbalance in women [160]. This approach appears to have a synergistic effect on GLUT-4 and warrants further in-depth investigations [161]. Vitamin E, specifically gamma-tocopherol, is a fat-soluble vitamin known for its potent antioxidant properties. It can stimulate intracellular antioxidant enzymes that protect against lipid peroxidation, thereby aiding in the battle against free radicals [162]. Another powerful antioxidant, vitamin C, or L-ascorbic acid, is an essential nutrient for the human body and serves as a cofactor in crucial enzyme processes [163]. Its antioxidant effects are realized either through a direct response to aqueous peroxyl radicals or by gently elevating the levels of fat-soluble antioxidant vitamins [163]. In a study involving a mouse model of androgen-induced PCOS, it was observed that vitamin C led to an increase in antioxidant and metabolic enzyme levels while simultaneously reducing levels of MDA and cytokines [164]. Furthermore, in the same study, the supplementation of vitamin C was found to have a positive impact on ovarian morphology and the suppression of androgen receptor expression, likely due to its antioxidant properties [164]. Vitamin E supplementation was notably effective in enhancing blood flow to ovarian tissues and subsequently restoring folliculogenesis. This included improvements in follicular growth, selection, maturation, and enhanced ovulation among PCOS patients [165]. Interestingly, in certain instances, vitamin E outperformed some conventional PCOS medications such as clomiphene citrate and metformin, resulting in improved ovulatory rates, pregnancy rates, and better endometrial conditions. When combined, the use of vitamin E, ethinyl estradiol, cyproterone, and metformin demonstrated a more successful approach to promoting ovulation and increasing the likelihood of pregnancy compared to using these substances individually. Besides those, other antioxidant molecules also showed effective and/or beneficial roles in overcoming PCOS and its associated co-morbid conditions [166].

According to several studies, a significant portion of women with PCOS tend to consume an imbalanced diet that lacks essential nutrients such as fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, magnesium, zinc, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin B12, and vitamin D [146]. In contrast, their diet tends to contain excessive amounts of sucrose, salt, total fats, saturated fatty acids, and cholesterol [146]. When researchers explored whether these nutritional deficiencies could be addressed through a calorie-restricted diet with a lower GI, they found that it had a beneficial impact, particularly on hydrophilic vitamins [167]. Many of the B vitamins, when consumed in larger quantities through the diet, have drawn the attention of various studies about PCOS and its associated symptoms. This heightened interest is due to the emerging significance of homocysteine (Hcy) in PCOS, with a particular focus on vitamins B6, B12, and folic acid. Elevated total plasma Hcy levels in individuals with PCOS have been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular and reproductive issues. Hcy is an essential amino acid derived from dietary methionine [168]. Vitamins B6, B12, and folic acid all play crucial roles in regulating Hcy levels, and there is evidence suggesting a connection between elevated Hcy levels and IR in the pathophysiology of PCOS [168]. It is also observed that the women with PCOS use to show lower serum vitamin B12 concentrations were associated with IR, obesity, and elevated Hcy levels [168]. Additionally, folic acid supplementation has proven beneficial in reducing elevated blood Hcy levels, particularly in women without IR. Furthermore, it has been established that a deficiency in vitamin B3 increases the risk of impaired cardiovascular function [169] and the development of inflammation, contributing to the development of related diseases [170]. Metformin, a commonly used medicine, is used to manage PCOS in women and regulate blood glucose levels. However, long-term usage has also been associated with deficiencies in cobalamin (vitamin B12) and thiamine (vitamin B1) [171]. Thus, as a supplement, thiamine can be a valuable choice, as it enhances transketolase activity. This activity plays a role in preventing vascular damage, consequently reducing the risk of cardiovascular issues [172].

Moreover, coenzyme Q10 administration must be considered in addition to the latent advantages of vascular protection in PCOS. Treatment, using CoQ10, had a positive effect on indicators of inflammation and endothelial ailments in overweight and obese PCOS individuals [173]. Fasting blood glucose and HOMA-IR both were significantly impacted by CoQ10 alone or in conjunction with vitamin E [174]. CoQ10 supplementation also dramatically improves sex hormone levels, lipid and glucose metabolism, and inflammation. Resveratrol is thought to be a potent antioxidant with anti-inflammatory molecules [174]. It increases the activity of the cellular antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT, and GPx. Resveratrol administration in an animal model study results in dramatic reductions in several antral follicles, levels of plasma anti-mullerian hormone and IGF-1, and the activity of SOD dropped, besides enough quantitative elevation of GPx, suggesting that it may be a beneficial agent for PCOS because of its free radical scavenging characteristics [174]. In addition, individuals with PCOS had lower levels of testosterone and DHEA.

Vitamin D is crucial in PCOS as it enhances overall insulin action by promoting insulin synthesis and release from pancreatic beta cells, upregulating the expression of insulin receptors, and increasing insulin responsiveness for glucose transport into cells [174]. It also plays a role in regulating extracellular calcium and parathyroid hormone concentrations, indirectly influencing glucose metabolism and preventing the production of proinflammatory cytokines associated with IR [6]. PCOS women taking cholecalciferol (vitamin D) experienced improved glucose metabolism; reduced estradiol, TGs, and fasting glucose levels; and enhanced menstrual cycle regularity. Combined supplementation of magnesium, zinc, calcium, and vitamin D led to a significant reduction in hirsutism and total testosterone levels [175], while combined vitamin D and fish oil resulted in decreased inflammatory markers and improved mental health indicators, along with lower total testosterone levels [175]. Recent research works suggest that myoinositol is as effective as metformin in improving the clinical and metabolic profile of women with PCOS and diabetes-related metabolic abnormalities. Unlike metformin, myoinositol has no negative effects. Myoinositol enhances glycemia, improves insulin sensitivity, and regulates testosterone levels [175]. In PCOS, myoinositol is frequently epimerized into d-chiro-inositol (DCI) in the ovary, impacting FSH signaling and egg quality. Both myoinositol and berberine, which activates 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase such as metformin, have positive effects on metabolic parameters and hormonal regulation in PCOS [175]. Inositols, including myoinositol and DCI, have the potential to increase fertility and restore ovulation in women with PCOS. Berberine influences the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, improving ovulation rates, menstrual cycle control, and the likelihood of pregnancy [175]. Chromium, though a doubtful micronutrient, is suggested to enhance cellular glucose uptake in PCOS individuals and is associated with reductions in the expression of enzymes linked to dehydroepiandrosterone in adipose tissue. Overall, myoinositol, berberine, and chromium are considered safe and effective for the treatment of PCOS, with minor and temporary side effects reported for berberine [175]. Several scientific reports proposed potential benefits of zinc and selenium supplements for individuals with PCOS to address nutritional deficiencies. Zinc plays essential roles in lipid and glucose metabolism, fertility, and intracellular signaling, with lower serum zinc levels associated with impaired glucose tolerance, hyperinsulinemia, inflammation, and an unfavorable lipid profile [175]. Zinc can emulate insulin effects in adipose tissues, promoting processes such as lipogenesis and glucose transport. Selenium, another beneficial micronutrient, may reduce CRP levels through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Including omega-3 fatty acids in the diet is advisable for women with PCOS, as deficiencies in these nutrients can impact the immune system, insulin sensitivity, cellular differentiation, and ovulation [175]. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation may benefit women with PCOS experiencing hyperinsulinemia and folliculogenesis problems due to excessive OS [175]. Dietary supplementation should be individualized, requiring patient counseling for active participation and adherence to enhance overall metabolic balance. The initial step in PCOS treatment should focus on establishing a healthy lifestyle and adopting a well-balanced diet [175].

Melatonin acts as an antioxidant and free radical scavenger, exhibiting unique properties such as engaging in deluge reactions with ROS and being produced in mild OS conditions [174,176]. In PCOS animal models, melatonin therapy improved estrogen activity, reduced inflammatory markers, decreased body weight, BMI, intra-abdominal fat, insulin, and CRP levels, and showed a favorable lipid profile. In PCOS patients, melatonin treatment reduced hirsutism, total testosterone, high-sensitivity CRP, and MDA levels, while enhancing GSH levels and overall antioxidant capacity. Melatonin positively affected mental health metrics, insulin levels, HOMA-IR, cholesterol levels, and gene expression in women with PCOS [174]. Melatonin therapy increased the likelihood of pregnancy in PCOS patients undergoing intrauterine insemination [174,177]. In human ovarian granulosa cells from PCOS patients, melatonin increased the expression of CYP19A1 and lowered IL-18 levels, aiding in oocyte maturation. Steroidogenic effects of melatonin controls ovulation, reverses IR associated with MS in PCOS and dyslipidemia, and prevents hyperplastic alterations in the uterus; melatonin administration may thus be advantageous for women with PCOS [174,178]. Selenium supplementation decreased plasma MDA levels, clinical HA, serum hs-CRP levels, and serum DHEA levels in PCOS patients. Magnesium and zinc supplements combined had comparable results in PCOS women [174]. Chromium treatment improved glycemic control and OS in PCOS-afflicted infertile women [174]. Crocetin, with anticancer and hypolipidemic properties, may inhibit PCOS and its pathophysiologic abnormalities [179]. Sometimes it is also possible that hypervitaminosis or interrelationships of other vitamins may cause some deleterious effects. Hypervitaminosis of vitamin D is associated with glucose intolerance in PCOS patients [180]; besides that, it is well known to all that excessive use of vitamin C causes diarrhea, nausea, abdominal cramps, and gastrointestinal disturbances. On the other hand, excess metformin is also associated with lower some B-group vitamin [181], and Hcy can be decreased by the excess use of folic acid and B-group vitamin [182]. Excess vitamin B12 also common cause of diarrhea, blood clots, severe allergic reactions, which may be a boomerang condition, as the PCOS is very much prone to immune responses, CVD, and metabolic complications.

Spirulina (SP), a form of blue-green algae, is a potent inhibitor of lipid peroxidation and has free radical scavenging activity, which can be beneficial for the protection against OS, thus reducing the DNA damage [183,184]. Besides its various beneficial effects on male reproductive physiology [185,186] and its specific effects on female reproductive physiology [183,184], it is expected that this blue-green algae should have the protective role on PCOS and other co-morbid conditions of PCOS such as IR, diabetes mellitus, MS, HA, and cardiovascular risk. The compound from SP can also cure PCOS and lessen the potential negative effects of Met when used in combination treatment [187].

Use of medicinal plant

All genotypes of PCOS women can benefit from the use of medicinal herbs such as Aloe vera, cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum), green tea (Camellia sinensis), chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla), and white mulberry (Morus alba) [188], which can regulate lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Some of the herbs with beneficial effects on ovaries’ weight, insulin sensitivity, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory parameters include green tea. In ovarian tissue, green mint (Mentha spicata L.) exerts an antiandrogenic action and restores the follicular growth. In addition to its ability to imitate estrogen, licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra) appears to be beneficial in lowering excessive testosterone because it prevents androstenedione from being converted. However, this plant also causes hypertension, hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis [189]. Herbal medications may have an impact on the 5-alpha-reductase enzyme’s activity, blocking it and halting hair loss [190]. Alopecia can be prevented by Serenoa repens, Camellia sinensis, Rosmarinus officinalis, and Glycyrrhiza glabra [190]. The herb Vitex agnus-castus, which has been used in traditional medicine for generations [191], is effective in regulating the menstrual cycle. The flaxseed lignans, which have undergone the most research [192], are the well-studied dietary phytoestrogens. They may change the activity of the aromatase enzyme to modify the relative amounts of circulating sex hormones and their metabolites. Curcumin, a phytochemical component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), demonstrates a physiological activity and serves as an effective antioxidant-stress reducer in individuals with PCOS [193]. Nettle (Urtica dioica), a multifunctional plant, exhibits antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic, and anti-cancer activities [194]. The potential hepatoprotective properties of herbs and their extracts, including curcumin and nettle, should be considered in addressing severe PCOS, especially in the context of conditions associated with MS and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [194]. Various chemicals found in herbs contribute to their therapeutic benefits in PCOS. Sesquiterpenes and antioxidant-active components in artichoke (Cynara Cardunculus) extract, along with silymarin in milk thistle (Silybum marianum) and milk thistle extract (Silymarin), exhibit antioxidant properties [195,196]. Black cumin (Nigella sativa) is beneficial for obese PCOS patients [196]. The reduction of OS is considered a potential mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of herbs in PCOS. Cinnamon supplementation has been shown to significantly decrease MDA levels and enhance the total serum antioxidant capacity [197]. In granulosa cells of the ovaries, Cangfu Congxian decoction reduced the generation of oxygen radicals and OS [198]. Overall, soy supplements may reduce the levels of MDA and raise the levels of total GSH, both of which have the potential to affect OS [199]. Trigonella foenum-graecum L. may boost the fertility rates by enhancing ovarian function and menstrual cycle regularity [200]. Similar effects on fertility were also seen with Danzhi xiaoyao and Linum usitatissimum L. powder [201]. Herbal remedies not only correct reproductive disorders but also significantly influence hormonal conditions and menstrual cycles. Menstrual periods may be restored to normal with the use of Cinnamomum cassia supplements for at least 6 months. When compared to metformin, cinnamon had fewer negative effects and, as a bioactive drug, reduced levels of anti-mullerian hormone [202]. Additionally, the levels of LH were lowered by cinnamon in combination with Glycyrrhiza spp., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., and Hypericum perforatum L. However, it had no appreciable impact on the levels of testosterone or FSH [203]. The hormonal state and menstrual cycles appear to be affected by cinnamon in all of its forms (extract, powder, and supplement) [204]. Trigonella foenum-graecum L. exhibited positive effects on fertility and helped regulate the menstrual cycle [205]. It is also evident that Linum usitatissimum L. is effective in controlling menstrual periods without significantly altering hormone levels or producing hirsutism [206]. Contrarily, consuming marjoram tea enhanced the hormonal state [206]. It was discovered that Vitex agnus-castus had far fewer negative effects while offering equivalent benefits to oral contraceptives in the control of menstrual periods. The levels of prolactin or testosterone were unaffected by Vitex agnus-castus [206]. However, in PCOS patients with oligo-amenorrhea, Nigella sativa L. [206], Apium graveolens L. and Pimpinella anisum L. [206,207] controlled menstrual periods and reduced LH levels. Regarding the anti-androgenic properties of herbs and how they affect hirsutism, there are very few studies available. The degree of hirsutism and the amount of testosterone were found to be decreased by spearmint tea [206], Anethum graveolens L., Asparagus racemosus Willd. [206], and Matricaria chamomilla L. [206]. Although Camellia sinensis L. and Tian gui [206] were found to lower testosterone levels, there is little information on how they affect hirsutism. It appears that further research is required to fully understand any possible effects of herbs on hirsutism. Furthermore, several researchers have looked at the impact of soy with varying degrees of success. Besides those, a different study found that the use had a positive effect on improving hormonal balance [192]. With no discernible effect on fasting blood sugar (FBS), Cinnamon, Glycyrrhiza spp., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., and Hypericum perforatum L. decreased BMI and insulin levels [192,206]. Nigella sativa L. and Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume administrations were related to a significant decrease in FBS, insulin, and IR, as well as cholesterol, TGs, and LDL levels [192,206]. Additionally Lagerstroemia speciosa L. and Cinnamomum burmannii are also helpful in reducing the BMI of the patients [202]. The efficiency of various green tea species in treating PCOS patients’ metabolic dysfunction has received mixed reviews [208]. Juice from Camellia sinensis L. and Punica granatum L. was found to be effective in lowering blood glucose levels, IR, WC, and body weight [192,206]. However, neither the lipid profile nor the amount of blood insulin was impacted by Chinese green tea [206]. Additionally, Nigella sativa L. might after a specific duration lower insulin, IR indices, cholesterol, and TG levels [206]. It was revealed that the therapeutic benefits of Vitex agnus-castus [209] and berberine [210] on PCOS patients’ metabolic dysfunction were comparable to those of metformin. By reducing IR and TG levels in the blood, soy supplementation (isoflavone and phytoestrogen) was able to modulate metabolic dysfunction [206]. In addition to herbs, it has been demonstrated that eating foods such as red onions (Allium cepa L.) [206], flaxseed oil, walnuts, and almonds can help PCOS patients with their metabolic dysfunctions and lipid profiles [211]. Natural remedies are well renowned for having safer results but it was also reported that cinnamon can cause allergic reaction in patients when used for prolonged time [212]; similarly, excessive use of green tea may cause complications to central nervous system [213]. Therefore, we can conclude that the beneficial effects of those herbs or antioxidants are totally dose dependent. It could be recommended only after the dose- and time-dependent trial on the individuals having PCOS (Figure 1).

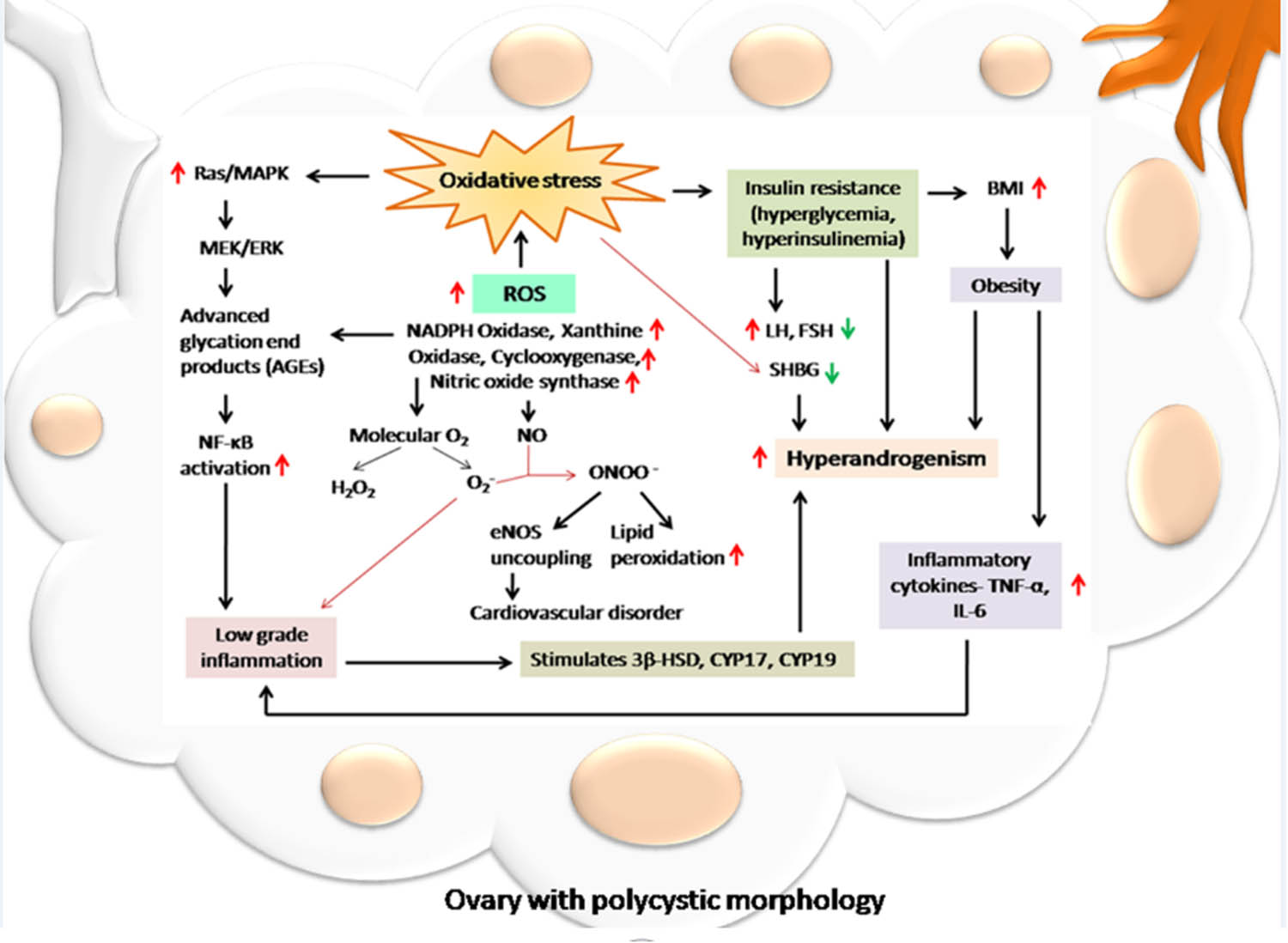

Role of free radical-induced OS in PCOS. Free radical-induced OS plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis and progression of PCOS. The imbalance between the oxidants and antioxidants occurs by an increased production of reactive free radicals such as ROS and/or RNS. The higher activities of NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, COX, and NO synthase may result in higher production of H2O2, superoxide anion, and NO. Moreover, the generation of peroxynitrite anion causes excessive lipid peroxidation, and uncoupling of endothelial NO synthase, which triggers cardiovascular disorders in PCOS patients. When focusing on the downstream signaling, OS in PCOS can upregulate the Ras/MAPK pathway and activate NF-κB. As a result, low-grade inflammation is observed and it increases the expressions of principal steroidogenic enzymes including 3β-HSD, CYP17, and CYP19. This might be responsible for HA. On the other hand, OS is also responsible for IR, which may contribute to the induction of obesity and cytokine-mediated inflammation in PCOS women. It also increases the LH-to-FSH ratio and reduces the level of SHBG, which ultimately leads to HA, one of the major signs of PCOS.

Conclusion

Among women of reproductive age, PCOS is the leading cause of infertility associated with anovulation. In both animal and human reproductive medicine, the link between OS and PCOS is a significant concern. This article has outlined the most significant roles played by OS in the pathophysiology of PCOS in this review, which also includes a summary of the most recent research on the topic. Obesity, IR, inflammation, and HA, all of which are frequent symptoms and probable causes of PCOS, are strongly correlated with OS. Additionally, too much androgen may cause OS, IR, and inflammation. Antioxidants can help PCOS patients with their OS and IR as well as their ovarian environment, androgen levels, and follicular maturation. Additionally, they can produce superior results when combined with other substances to combat the difficulties of PCOS. In PCOS patients, antioxidants can control lipid metabolism and vascular endothelial cell activity, which reduces obesity, lowers the incidence of chronic problems, and enhances the patient quality of life. Additionally, certain antioxidants, such as melatonin, might improve the quality of life of PCOS patients and their psychological well-being. More research in this area appears to be required because there is not enough information to pinpoint the best antioxidant management strategy for PCOS women. In the modern day, using supplements such as zinc, selenium, chromium, and vitamins, along with some medicinal herbs, may help with the different issues of PCOS and its co-morbid disorders in addition to the use of antioxidants, the benefits of exercise, and the practice of yoga.

-

Author contributions: Koushik Bhattacharya and Rajen Dey designed and planned the research work; Rajen Dey, Chaitali Bose, Nimisha Paul, and Asim Kumar Basak wrote the article. Mohuya Patra Purkait, Nandini Shukla, Gargi Ray Chaudhuri, Aniruddha Bhattacharya, Rajkumar Maiti, Prithviraj Karak, Krishnendu Adhikary, Debanjana Sen, and Alak Kumar Syamal made the revisions. Koushik Bhattacharya and Rajen Dey completed the last revision, corrections, and adjustments. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Bhattacharya K, Sengupta P, Dutta S, Chaudhuri P, Das Mukhopadhyay L, Syamal AK. Waist-to-height ratio and BMI as predictive markers for insulin resistance in women with PCOS in Kolkata, India. Endocrine. 2021;72(1):86–95.10.1007/s12020-020-02555-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Bhattacharya K, Saha I, Sen D, Bose C, Chaudhuri GR, Dutta S, et al. Role of anti-Mullerian hormone in polycystic ovary syndrome. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2022;27(1):32.10.1186/s43043-022-00123-5Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):19–25.10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Murri M, Luque-Ramírez M, Insenser M, Ojeda-Ojeda M, Escobar-Morreale HF. Circulating markers of oxidative stress and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(3):268–88.10.1093/humupd/dms059Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Zhang J, Fan P, Liu H, Bai H, Wang Y, Zhang F. Apolipoprotein A-I and B levels, dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome in south-west Chinese women with PCOS. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(8):2484–93.10.1093/humrep/des191Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Dey R, Bhattacharya K, Basak AK, Paul N, Bandyopadhyay R, Chaudhuri GR, et al. Inflammatory perspectives of polycystic ovary syndrome: Role of specific mediators and markers. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2023;28:33. 10.1186/s43043-023-00158-2 Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):347–63.10.1093/humupd/dmq001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Nasiri N, Moini A, Eftekhari-Yazdi P, Karimian L, Salman-Yazdi R, Zolfaghari Z, et al. Abdominal obesity can induce both systemic and follicular fluid oxidative stress independent from polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;184:112–6.10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.11.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Savic-Radojevic A, Bozic Antic I, Coric V, Bjekic-Macut J, Radic T, Zarkovic M, et al. Effect of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia on glutathione peroxidase activity in non-obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hormones (Athens). 2015;14(1):101–8.10.14310/horm.2002.1525Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] González F, Nair KS, Daniels JK, Basal E, Schimke JM. Hyperandrogenism sensitizes mononuclear cells to promote glucose-induced inflammation in lean reproductive-age women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302(3):E297–306.10.1152/ajpendo.00416.2011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, Hoeger KM, Murad MH, Pasquali R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):4565–92.10.1210/jc.2013-2350Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Li H, Zhang Y, Lu L, Yi W. Reporting quality of polycystic ovary syndrome practice guidelines based on the RIGHT checklist. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(42):e22624.10.1097/MD.0000000000022624Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, et al. The androgen excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: The complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(2):456–88.10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035Suche in Google Scholar PubMed