Abstract

Bilingual education has become increasingly popular in China, with a subsequent growth in research, particularly research with a qualitative component that examines learners’ and teachers’ experiences and perspectives. These studies have mostly been conducted in individual classroom settings where contexts and learners differ, making findings less transferrable to other educational settings. To address this need, we conducted a qualitative synthesis of research that aims to provide a holistic and rich description of bilingual education in China. Our focus is on the implementation of bilingual education in different educational contexts, learners’ and teachers’ perceptions of bilingual education, and the research instruments used for the evaluation of bilingual education. Following a discipline-specific methodological framework for conducting qualitative research synthesis (Chong, Sin Wang & Luke Plonsky. 2021. A primer on qualitative research synthesis in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly 55(3). 1024–1034), we identified suitable studies using a pre-determined search string within various databases. Search results were screened based on a set of inclusion criteria and relevant information was extracted from the included studies using a piloted data extraction form. The extracted data were synthesised using grounded theory to identify new themes and sub-themes. Our findings point to the need for more fine-grained classifications of bilingual education models, despite the fact that Chinese learners generally show positive attitudes towards bilingual education. The study ends with an analysis of limitations, as well as recommendations for future research and practice.

1 Introduction

Bilingual education refers to the use of two languages as the media of instruction (García 2009). The reason bilingual education is prevalent nowadays is twofold: globalization creates needs for bilinguals who are proficient users of more than one language; bilingual education facilitates intercultural communication and widens the cognitive capacity of individuals (Jawad 2021). The rise of Chinese bilingual education stemmed from its open-door policy in 1978 (Gao and Wang 2017). At that time, English was taught as a subject, but learners were incapable of using the language in real-life contexts. Thus, there was growing dissatisfaction with the traditional methods of English language teaching in China, which predominantly used the first language (L1) of learners. Under the influence of bilingual education implementation in other countries, for example, immersion in Canada and dual-way bilingual education in the United States, China began to adopt and adapt various models of bilingual education. Simultaneously, the Ministry of Education (MOE) called for a reform in English language teaching in universities to improve the communication skills of university learners by promoting bilingual education in China (MOE 2005). In 2021, MOE amended the education law, which mentioned that schools and institutions in ethnic autonomous regions and ethnic minorities should use indigenous languages to implement bilingual education while the government would provide additional support for minority learners.

Although the implementation of bilingual education varies across China, research remains piecemeal, especially regarding learners’ and teachers’ experiences. Thus, there is a need for a qualitative synthesis of research findings that focuses on issues pertaining to implementation (how bilingual education is implemented by teachers and experienced by learners), perceptions (learners’ and teachers’ attitudes towards bilingual education), and evaluation (research tools used to evaluate the effectiveness of bilingual education) of bilingual education in China. These issues will be discussed in light of the synthesised findings.

2 Literature review

2.1 Defining ‘bilingual education’

García and Lin (2017) define bilingual education as the use of diverse languages to teach. Jawad (2021) put forward the Separate Underlying Proficiency and Common Underlying Proficiency models to refer to the interrelationship between the two languages used by bilinguals. The separate Underlying Proficiency model, which influenced the early development of bilingual education, posits that bilinguals’ proficiency and knowledge of the two languages are discrete entities, each with a limited capacity for storage, while the Common Underlying Proficiency model, representing a more dynamic view towards the confluence between the use of two languages by bilinguals, indicates that the two languages are inseparable from a cognitive perspective.

A few terms are usually confused with bilingual education, for example, trilingualism, multilingualism, monolingualism, and plurilingualism. Monolingualism refers to speaking only one language or having active knowledge of one language and passive knowledge of other languages (Ellis 2006). Multilingualism could be seen as an individual’s ability and language use in society (Edwards 2012). According to Cenoz (2013), multilingualism can include bilingualism and trilingualism. Piccardo (2018) mentioned multilingualism refers to the knowledge of multiple languages in society. Plurilingualism means that individuals could acquire languages simultaneously from exposure to multiple languages, and it is also sometimes defined as individual multilingualism (Cenoz 2013). Piccardo (2018) mentioned that plurilingualism is the interrelation between languages associated with dynamic language acquisition. In other words, a classroom with learners speaking different mother tongues is multilingual, while a class where teachers and learners adopt strategies that celebrate linguistic diversity to maximize communication is a plurilingual classroom (Piccardo 2018). Trilingualism is a branch and extension of bilingualism (Anastassiou et al. 2017), which refers to multilingual speakers gradually obtaining the ability to communicate in different languages. For example, people being exposed to three languages from birth and being able to use three languages in writing and orally can be called trilingual. Hoffmann (2001) mentioned that there is no clear distinction between bilingualism and multilingualism, and multilingualism can be seen as a variant of bilingualism. However, Aronin (2005) indicated that the notions of trilingualism and multilingualism are interchangeable. Dewaele (2015) indicated that people who learn a variety of languages may develop multicompetence. Specifically, grammatical and lexical competence of a learner may be influenced by multicompetence (Dewaele 2015). In terms of cultural awareness, bilinguals and multilingual are more receptive to cultural differences than monolinguals.

2.2 Bilingual education practices in the U.S., Canada, and China

Whilst bilingual education is adopted in different ways in many countries around the world, the U.S. and Canada are the pioneers in bilingual education and their models serve as the foundation for various forms of bilingual education in other countries. In Canada, immersion refers to the creation of a learning environment that is rich in the target language; however, the use of L1 is still acceptable in immersion. Ultimately, immersion does not expect learners to develop native-like competence in the target language (Beardsmore 1995). Dicks and Genesee (2017) discussed three forms of immersion in Canada: French immersion, heritage language programs, and indigenous language programs. French immersion is for both the majority of learners speaking English and learners with minority backgrounds (Dicks and Genesee 2017). French immersion is popular in Canada because French and English are the official languages of the country and they are protected in the education system since the adoption of the Multiculturalism Act of 1988 (Dicks and Genesee 2017).

Regarding bilingual education in the U.S., dual language immersion programs are usually adopted to provide equitable education for ethnic minorities (Bybee et al. 2014; Collier 1995). Osorio-O’Dea (2001) compared different bilingual education programs in the U.S. including English as a second language immersion, and transitional and two-way bilingual education. In terms of bilingual education in China, Lin (1997) and Geary and Pan (2003), investigated bilingual education policies and practices for Chinese ethnic minorities. Similarly, Gao and Wang (2017) discussed two types of bilingual education programs in China. They are the government-led bilingual education programs for ethnic minorities and the Chinese-English bilingual education programs (Gao and Ren 2019; Gao and Wang 2017). However, the studies above about bilingual education in China only mentioned little about the preferences for bilingual education models. Although the number of studies on bilingual education in China has been on the rise in recent years, most of them only focus on a specific region (e.g., Shanghai in Wei 2013). It remains unclear how bilingual education is implemented in different regions in China. Equally, a thorough understanding of how Chinese teachers and learners think about bilingual education remains to be unravelled. Thus, our review intends to address these gaps and shed light on the preferences for bilingual education models, and perceptions of teachers and learners towards bilingual education in China.

3 Methodology

We adopted a qualitative synthesis of research as the methodology of this review (Chong and Plonsky 2021; Chong and Reinders 2021; Chong et al. 2023 in this special issue). The rationale for its adoption is that the 16 included publications are small-scale studies, making findings in these studies less transferrable due to the limited number of interviews and the small sample size. Despite the insightfulness of the findings of these studies, their ability to shed new light on bilingual education within other contexts is limited. Additionally, qualitative synthesis of research is a systematic and rigorous methodology to provide a reliable representation of the state-of-the-art of a research topic using a systematic approach (Chong and Reinders 2021). The rationale for synthesising qualitative data is that it can provide a rich description of the current situation of bilingual education in China, as well as on the perceptions of different stakeholders, such as teachers and learners.

To assure quality in the process of synthesis, the first author kept a researcher logbook to record the disagreements and how we resolved them, which not only shows reflexivity but also acts as a mechanism to ensure the quality in each stage (see Supplementary Material online). Reflexivity is what we intended to highlight in the process, which is concerned with what we disagreed, why we disagreed, and how we resolved the disagreement. A reflexive approach, in our opinion, is a much richer and more informative approach than calculating inter-coder reliability.

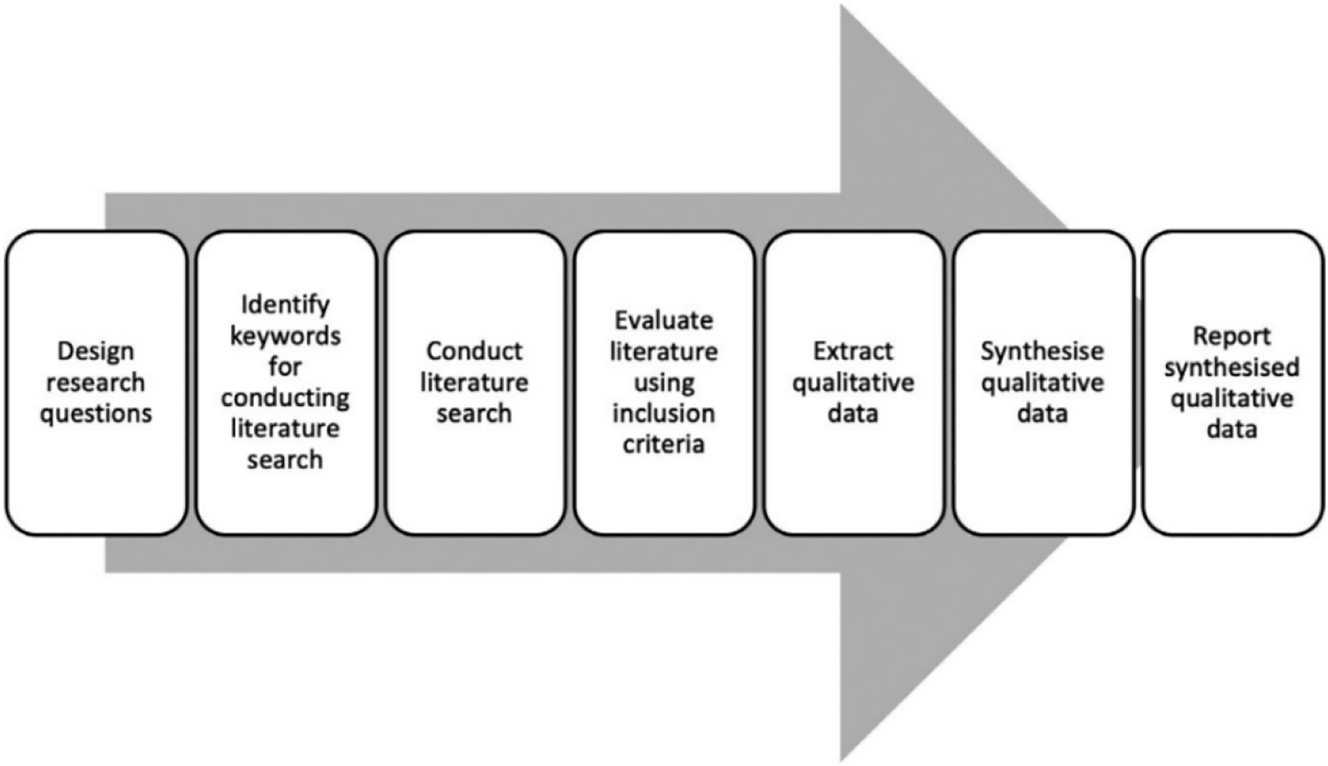

For the present study, we drew on a methodological framework for conducting qualitative research synthesis in TESOL (Chong and Plonsky 2021; see Figure 1). The rationale for employing this framework is that it comprises multiple methodological stages that can be used to guide the review process, contributing to transparency and systematicity, and in the future, replicability, of the process of identifying, extracting, and synthesising relevant qualitative data.

A methodological framework for conducting qualitative research synthesis in TESOL (Chong and Plonsky 2021, p. 1027).

3.1 Design research questions

To address the gaps in terms of ambiguity in how bilingual education is implemented and experienced in China, we developed the following research questions:

How is bilingual education implemented in China?

What do Chinese teachers and learners think about bilingual education?

How is bilingual education in China evaluated in research?

3.2 Keywords identified for conducting the literature search

Our focus is on “bilingual education”. As Chong and Plonsky (2021) mentioned, interchangeable words should be taken into consideration. Thus, “immersion”, “translanguaging” and “plurilingual*” were chosen as keywords. Based on these keywords, the following search string was developed and used to perform the search for this review:

(“bilingual education” OR “bilingual*” OR “translanguaging” OR “immersion” OR “plurilingual*”) AND (“China” OR “Chinese”)

3.3 Literature search conducted

We searched for studies in an exploratory way (Chong and Reinders 2020). The search was conducted in the following databases in March 2022: Web of Science, Scopus, and ERIC. The rationale for choosing these databases is twofold: (1) they can process the search strings verbatim; (2) Scopus and Web of Science allow for considerable length of the search queries to up to 1,000 terms (Gusenbauer and Haddaway 2020). Thus, ERIC, Scopus, and Web of Science are deemed appropriate databases to provide accurate and comprehensive search results.

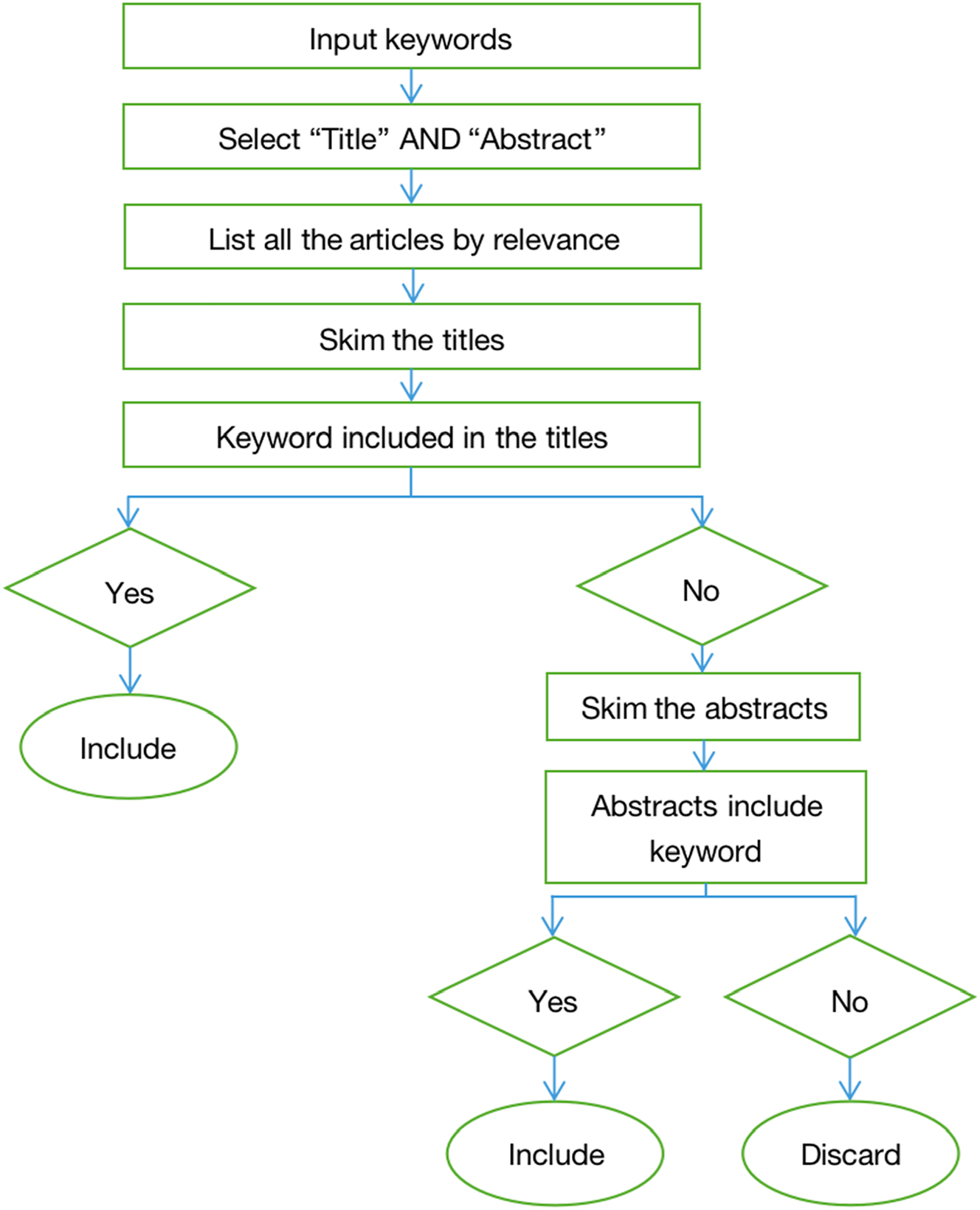

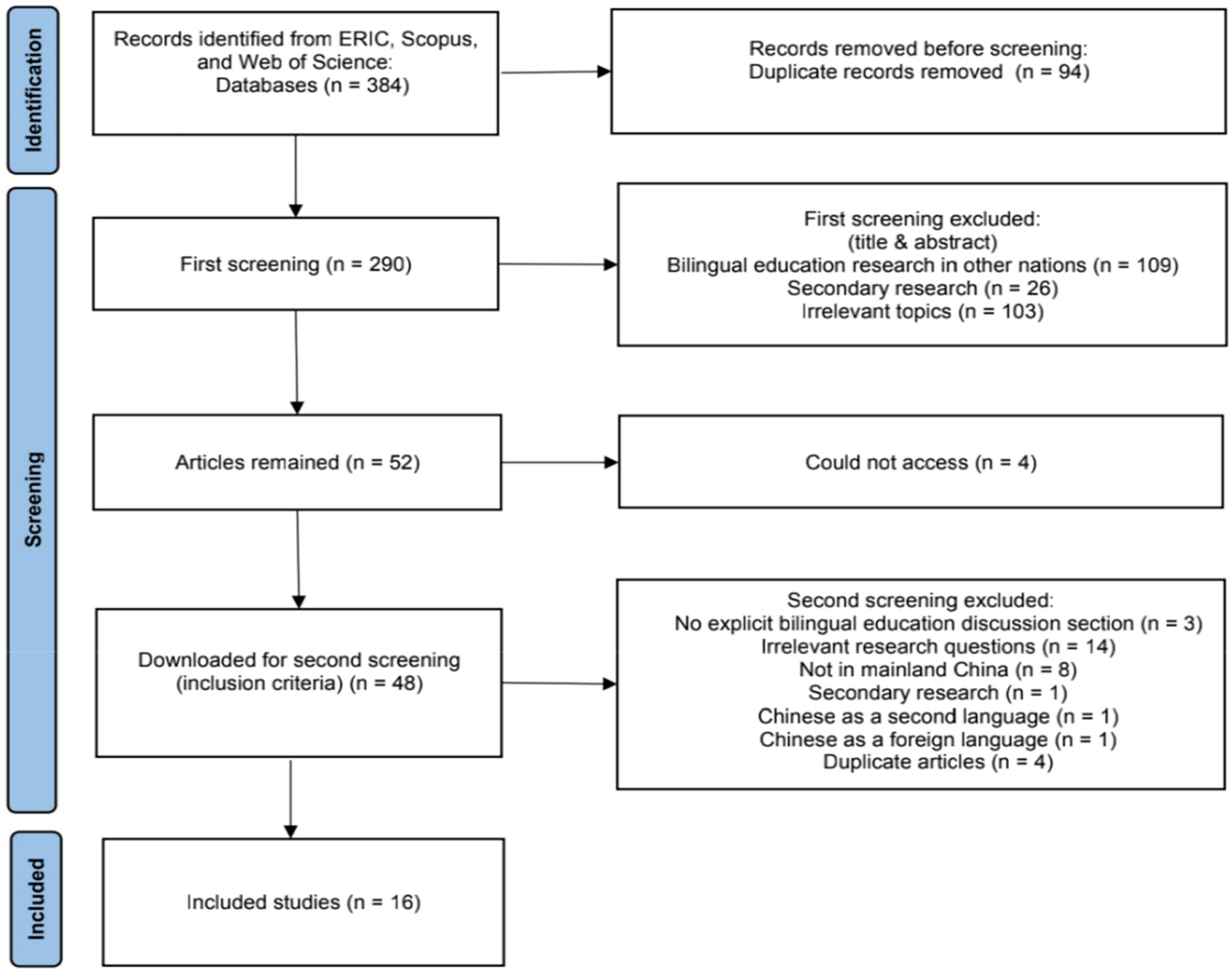

The first author initially filtered the studies following the steps listed in Chong and Reinders (2020; see Figure 2). We selected ‘Title’ and ‘Abstract’, listed all relevant articles, browsed through all titles and abstracts, and included all articles that matched the inclusion criteria. In total, 384 articles were included (see Figure 3). One hundred and nine articles with irrelevant contexts (research in a country other than China), 103 articles with irrelevant topics, 94 duplicate articles, and 26 secondary studies were excluded in the pre-screening and screening stages. After excluding these 332 articles, four of the remaining 52 articles were inaccessible, resulting in 48 articles.

Searching and first-screening articles (Chong and Reinders 2022, p. 6).

Flow chart of study selection (based on Page et al. 2021).

3.4 Evaluate literature using inclusion criteria

The second screening followed the inclusion criteria in Table 1. The search frame was between 2018 and 2022, which provides the latest primary research on bilingual education. Particularly, we focused on primary studies because we are interested in the implementation of bilingual education in China, not just the theories that underpin the concept of bilingual education. We only included publications written in English because we are affiliated with UK universities, and we can mainly access publications written in English. We acknowledge that there are some high-quality publications written in languages other than English that were excluded, which is one of the limitations of this review.

Inclusion criteria of the QRS.

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Time frame | Publications available between 2018 and 2022 |

| Location | Mainland China |

| Language | English |

| Type of publication | Primary studies |

| Participants of studies | English learners and teachers in mainland China |

| Conceptualization | There is a section explicitly discussing bilingual education (or its alternative terms). |

Following the search process (see Figure 3), We downloaded all 48 articles, of which we excluded three articles that do not contain an explicit section that discusses bilingual education, 14 articles with irrelevant research questions, eight studies in areas other than in mainland China, one secondary study, one study about Chinese as a second language and foreign language respectively, and four duplicate articles. Sixteen studies were included in this qualitative synthesis of research.

3.5 Data extraction and synthesis

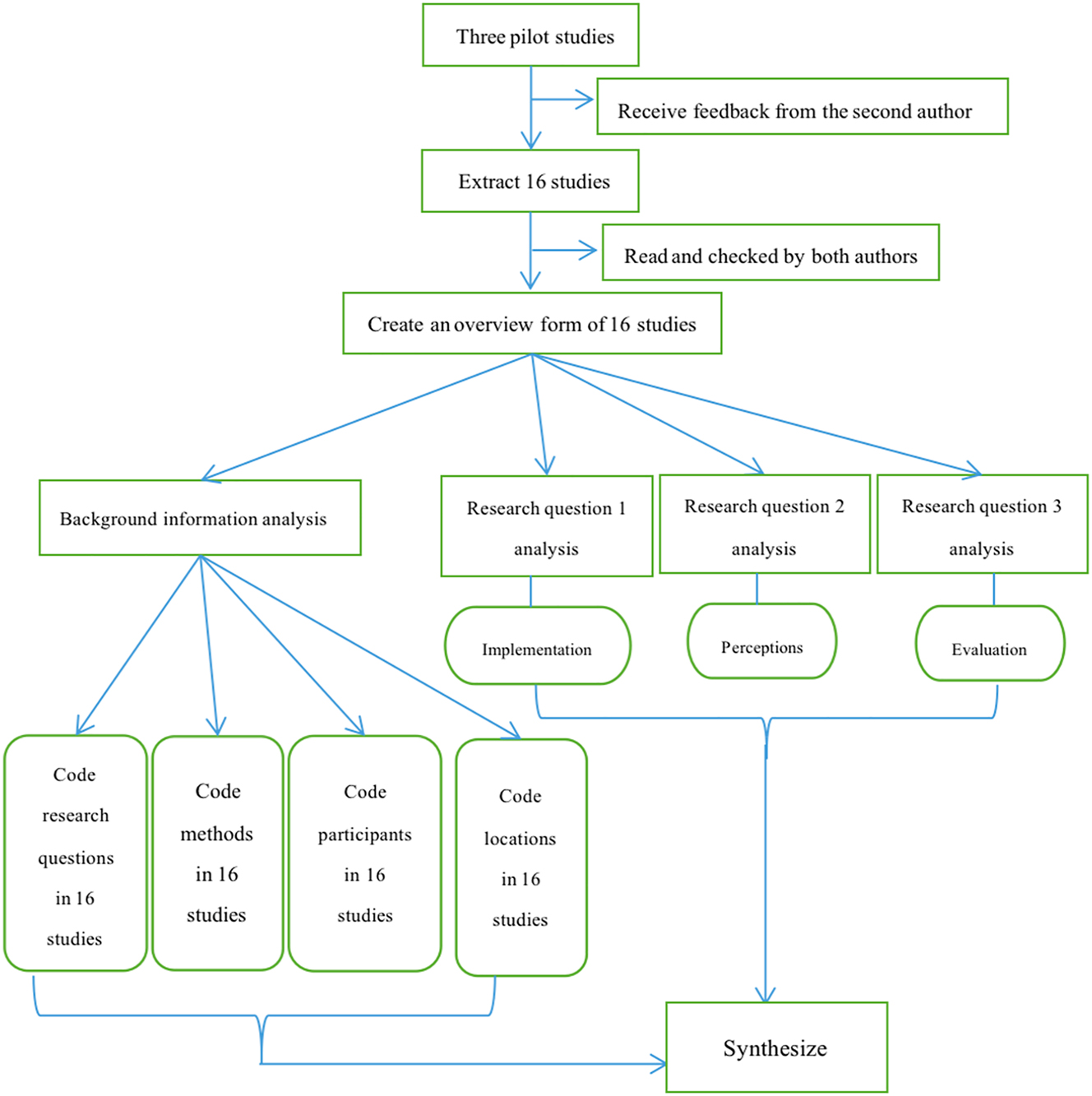

With the 16 included studies, information related to the research questions was extracted into a form adapted from Chong and Reinders’ (2022) (see Appendix I). The first author analysed and categorised the articles (see Figure 4). Twelve of the 16 articles were about Chinese-English bilingual education, and the remaining four were about bilingual education in minority languages (e.g., Mongolian) and Chinese. After co-developing the data extraction form with the second author, who is experienced in conducting research synthesis in language education, the first author extracted three studies using the extraction form and they were checked by the second author to ensure accurate data were extracted. After receiving feedback, the first author began to extract the remaining studies. The completed 16 data extraction forms were reviewed by both authors independently. Queries related to the extracted information were discussed and resolved during a series of bi-weekly face-to-face meetings that spanned across two months. After completing the 16 extraction forms, we produced an overview form summarising the 16 studies (see Appendix II), which consists of contexts, types of bilingual education (e.g., translanguaging, immersion), research methods, and findings to provide a holistic view of the included studies.

Analysis procedure of the 16 studies.

Based on the 16 extracted forms and the overview form, we synthesised the background information of 16 studies (e.g., research questions, methods, participants, locations) and the three research questions. The synthesis was conducted using grounded theory (Thornberg et al. 2014), as it is an inductive analytical approach, building data-driven conceptual understanding, which accords with the purpose of this study; that is, to identify bilingual education models and stakeholders’ perceptions towards bilingual education in China. We collated data from included studies to extraction forms with different focuses (research questions, research methods, participants, locations) and developed concepts and categories for each term in an inductive way. The study generated descriptive and conceptual categories through initial, focused, and axial coding (see Appendix III). In this study, the first author coded the 16 extraction forms line-by-line in the initial coding phase. Then, descriptive categories were developed to classify the extracted information in the focused coding phase. Finally, the related descriptive categories were combined into one conceptual category in the axial coding stage. The first author met with the second author bi-weekly to discuss every coding stage and at times they had discussions on the challenges the first author had. In the meetings, the second author also reviewed a sample of the coded data and offered feedback and suggestions when necessary. We have prepared a narrative summary of the meetings that we had concerning data extraction and synthesis, as well as photos of the notes that the second author took during the meeting (see Supplementary Material online).

4 Findings and discussion

4.1 Background information of the 16 studies

There are 41 research questions in the 16 studies, which are classified into two categories, internal and external focuses. Internal focus is endorsed by 27 research questions about teachers’ and learners’ perceptions, and bilingual practices. It consists of six conceptual categories. Of the six categories, there are 11 questions about perceptions and practices (e.g., Wang 2021). There are seven questions about the effectiveness of bilingual education for learners (e.g., Wang 2021), and four questions about the difference in learners’ performance under different bilingual practices (e.g., Yu et al. 2019). Three questions are about the adaptability of bilingual education in different contexts (e.g., Xiong and Feng 2018). Only one question is about the role of teachers in translanguaging (Troedson and Dashwood 2018) and teaching or learning strategies in bilingual education respectively (Zhou and Mann 2021).

On the other hand, the external focus of the research questions is about external environments or contexts (endorsed by 15 research questions), which consisted of five conceptual categories. Eight of the questions are about external factors that influence the implementation of bilingual education. For example, Yang (2018) referred to a question about the factors affecting the quality of bilingual teaching. There are three questions about reflections and recommendations for the implementation of bilingual education (e.g., Hiller 2021). It is closely followed by questions about the relationship between environment and achievement (endorsed by two research questions) (Wang and Lehtomäki 2022). Unique characteristics in the Chinese context (Xiong and Feng 2018) and the assessment of bilingual education (*Yang 2018) were the research questions in two studies. Coding of research questions of the 16 studies is shown in Appendix III.

In terms of research methods, nine studies adopted mixed methods by conducting questionnaires, class observations, surveys, tests, documents, field notes, interviews, and focus groups (e.g., Wang 2021). Four studies used qualitative research methods such as classroom observations, videotaping, field notes, documents, and interviews (e.g., Guo 2022), while only three studies used quantitative research methods, that is, questionnaires (e.g., Wang et al. 2018).

As for participants in the 16 studies, 11 studies had mature language learners from higher education institutions (e.g., Wang 2021) who are able to provide more in-depth and accurate reflection on their own learning experiences. These were followed by learners in primary schools (n = 3) (e.g., Rehamo and Harrell 2018)[1] and secondary schools (n = 3) (e.g., Xiong and Feng 2018).

As for location, seven studies were conducted in eastern China. Notably, the seven studies conducted in eastern areas of China were all about English-Chinese bilingual education. Seven studies were conducted in western China, four of which were about minority languages and Mandarin. Western areas are usually less economically developed areas in China and the introduction of Mandarin remains a challenge. It is worth noting that Zuo and Walsh (2021) conducted the study in two schools located in an eastern city and a southwestern city respectively. *Wang and Curdt-Christiansen (2019) noted that the study was conducted in the central region of China. The remaining two studies did not mention the location.

4.2 Findings and discussion based on the research questions

4.2.1 RQ1 – How is bilingual education implemented in China?

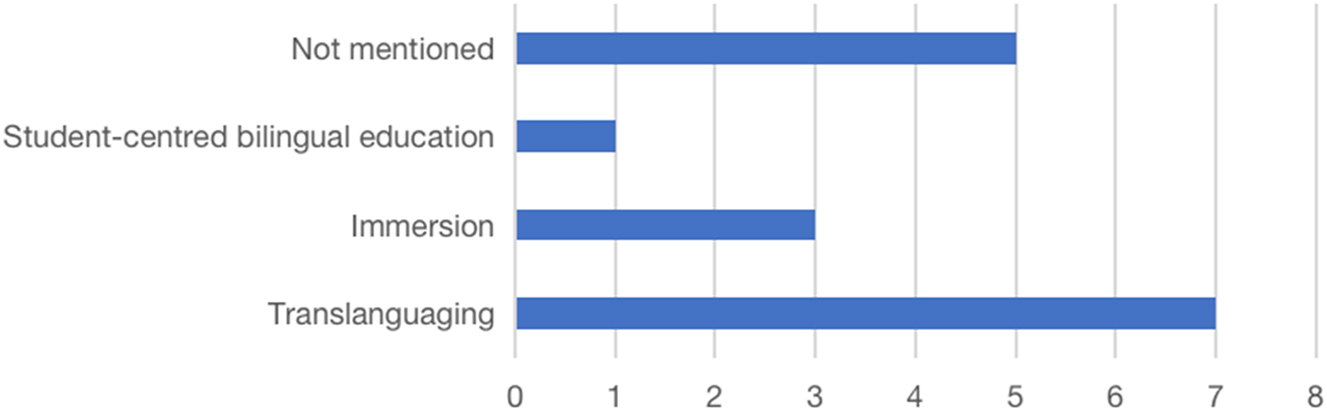

The included studies reported four conceptual categories (see Figure 5), including translanguaging (n = 7), immersion (n = 3), learner-centred bilingual education (n = 1), and five studies without specifying the type(s) of bilingual education. The coding scheme of the implementation of bilingual education is shown in Appendix IV.

Types of bilingual education in 16 studies.

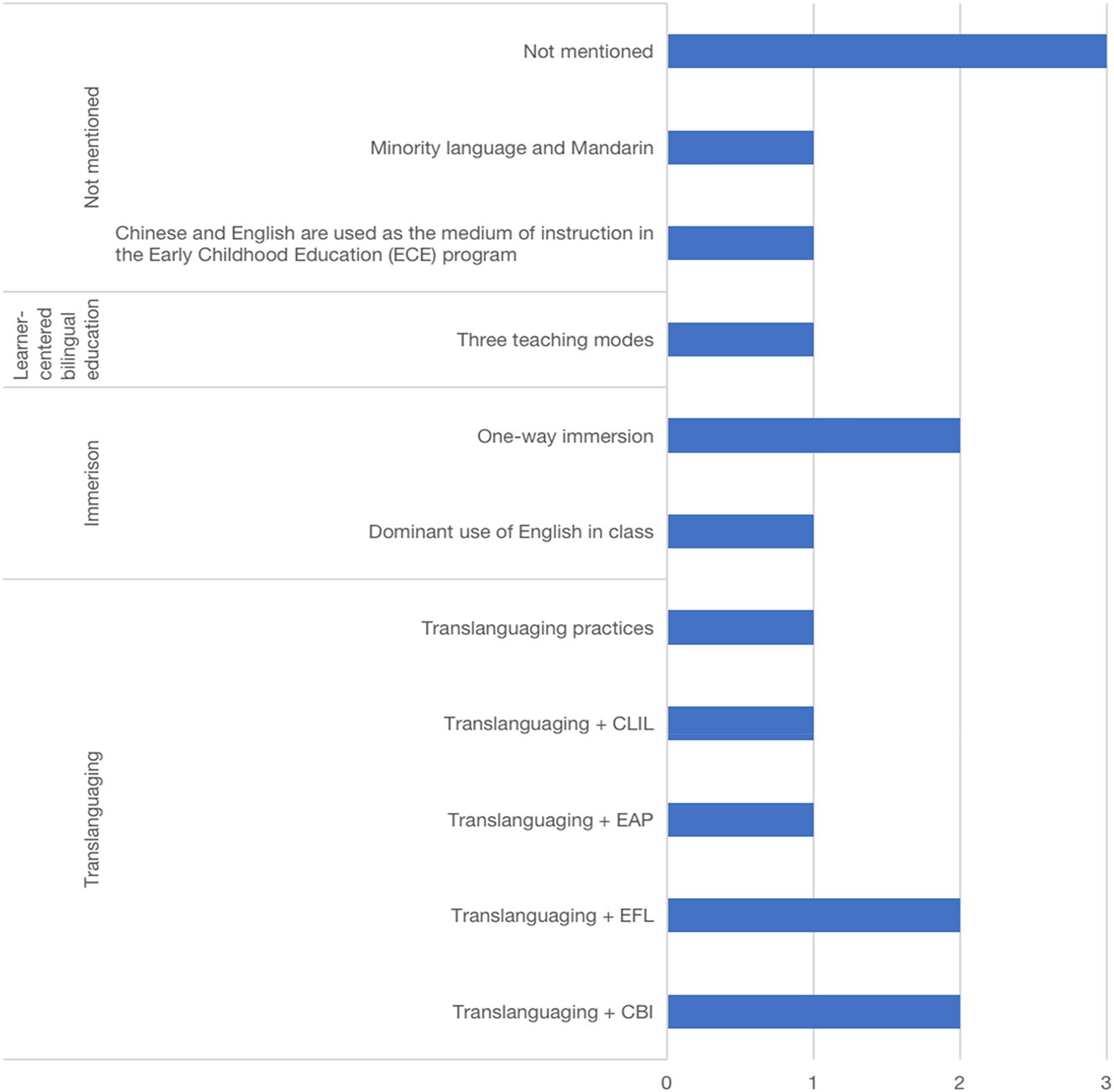

Among the seven studies about translanguaging (see Figure 6), two studies are about ‘translanguaging with content-based instruction (CBI)’ (Troedson and Dashwood 2018; Wang 2021), which emphasized the significance of understanding subject-specific content. CBI classes include the instruction of subject content and language-related activities, and teachers are required to teach both content knowledge and the second language (L2) (Wang 2021). Similarly, complex content-based concepts were explained using two languages in Troedson and Dashwood (2018). There are also two studies about ‘translanguaging in English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom’ (Guo 2022; Zuo and Walsh 2021). One study is about ‘translanguaging in English for academic purposes (EAP)’ (Hiller 2021), ‘translanguaging in content and language integrated learning (CLIL)’ (Zhou and Mann 2021), and ‘translanguaging practices’ (Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019) respectively. Specifically, EAP teachers designed writing tasks that employed translanguaging; for example, a short paper for discussing an important Chinese cultural notion (Hiller 2021). In CLIL classrooms, a theme-based reading course was conducted to develop learners’ language proficiency and content knowledge in Zhou and Mann (2021). In this study, translanguaging was implemented with three strategies: explanatory strategies, attention-raising strategies, and rapport-building strategies. Explanatory strategies refer to the textbook content explained in a combination of English and Chinese; attention-raising strategies refer to translanguaging being employed to raise learners’ attention to important teaching points; Rapport-building strategies are usually adopted on two occasions: teachers intend to keep the natural flow of interaction when learners are unable to understand concepts; teachers participate in learners’ group discussions when they overwhelmingly rely on their L1 (Zhou and Mann 2021).

Sub-types of bilingual education.

Similarly, four translanguaging practices were adopted by Wang and Curdt-Christiansen (2019): bilingual label quest, simultaneous code-mixing, cross-language recapping, and dual-language substantiation. Bilingual label quest refers to adopting the labels in another language to show the concepts in one language (Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019). Simultaneous code-mixing refers to the use of Chinese and English in meaning-making (Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019). Cross-language recapping refers to repeating the course content in another language, which has been taught in one language (Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019). The major difference between cross-language recapping and bilingual label quest lies in the fact that the latter only focuses on concepts. The fourth practice is dual-language substantiation, referring to the co-construction of knowledge based on two languages (Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019).

Among the three studies about immersion (Wang et al. 2018; Xiong and Feng 2018; Yao 2022; see Figure 6), one study is subsumed under ‘dominant use of English in class’, which means English is used as the medium of instruction while the use of Mandarin (L1) is allowed (Xiong and Feng 2018); the other two studies are coded as ‘one-way immersion’. In one-way immersion classes, L1 is forbidden in the class, and teachers are only allowed to speak in English (Fleckenstein et al. 2019; Yao 2022). Similarly, Chinese learners are also taught in English in Wang et al. (2018).

One study is grouped under ‘learner-centred bilingual education’ (Figure 6) (Yu et al. 2019). Yu et al. (2019) did not point out explicitly the type of bilingual education, but they introduced three teaching modes used in Mongolia for fluent bilinguals, limited bilinguals, and Mandarin monolinguals respectively. The reason these three teaching modes are labelled as ‘learner-centred bilingual education’ is that three teaching modes are implemented according to learners’ abilities and levels. Fluent bilinguals’ teaching mode refers to learners being taught in Mongolian and Chinese as a subject (Yu et al. 2019). On the contrary, limited bilinguals’ teaching mode means learners being taught in Chinese, while the heritage language, Mongolian, is the subject. The teaching mode used for Mandarin monolinguals refers to Chinese being used as the only language in class (Yu et al. 2019).

The above findings suggest that bilingual education is a rather loose pedagogical concept rather than specific approach(es) to language teaching. According to Wang (2010), the definition of bilingual education is loose because the understandings of what bilingual education constitutes range widely. It is demonstrated in the fact that five studies (31.25%) did not mention the types of bilingual education (see Figure 6) but used the overarching term ‘bilingual education’ in the studies (e.g., Yang 2018). Specifically, two of these studies (Li 2018; Wang and Lehtomäki 2022) described the pedagogical approach used to teach the target language without referring to a specific type of bilingual education, such as immersion. The other three did not mention how bilingual education was implemented in their studies at all (Rehamo and Harrell 2018; Wang et al. 2021; Yang 2018). Additionally, a more well-refined categorisation should be applied in bilingual education because there are five studies that do not specify type(s) of bilingual education. According to Azzam (2019), factors such as contexts and desired outcomes should be taken into consideration to define new types of bilingual education.

Bilingual education programs mentioned in the 16 studies were implemented for different durations (Appendix V) and using different materials (Appendix VI). Four studies mention the duration of the bilingual education program (e.g., Guo 2022), of which two studies implemented bilingual education for less than 50 h (i.e., 48 h in Guo 2022, and 38 h in Li 2018) and the other two studies implemented bilingual education for over 50 h (i.e., a two-year period in Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019, and 13 days in Rehamo and Harrell 2018). The other 12 studies did not specify the duration of the bilingual education program. Regarding materials, three studies introduce the materials used in the programs, including the textbook Gogo Loves English in Guo (2022), a Chinese textbook published in 2006 (Li 2018), and a textbook with philosophical and scientific knowledge in Rehamo and Harrell (2018). The other 13 studies did not mention any materials used (e.g., Wang 2021). From a practitioner’s perspective, teachers’ primary concern is the materials that can be used to teach bilingual classes and the duration of a bilingual program. However, such information is absent from the majority of the included studies. Similar to our earlier observation about types of bilingual education, researchers appear to adopt the term ‘bilingual education’ quite loosely without providing an operational definition that reflects how it is practised. Hew et al. (2019), while focusing on research on educational technology, indicated that research that is under-theorised may have limited relevance to scholarship and practice.

4.2.2 RQ2 – How do the Chinese teachers and learners think about bilingual education?

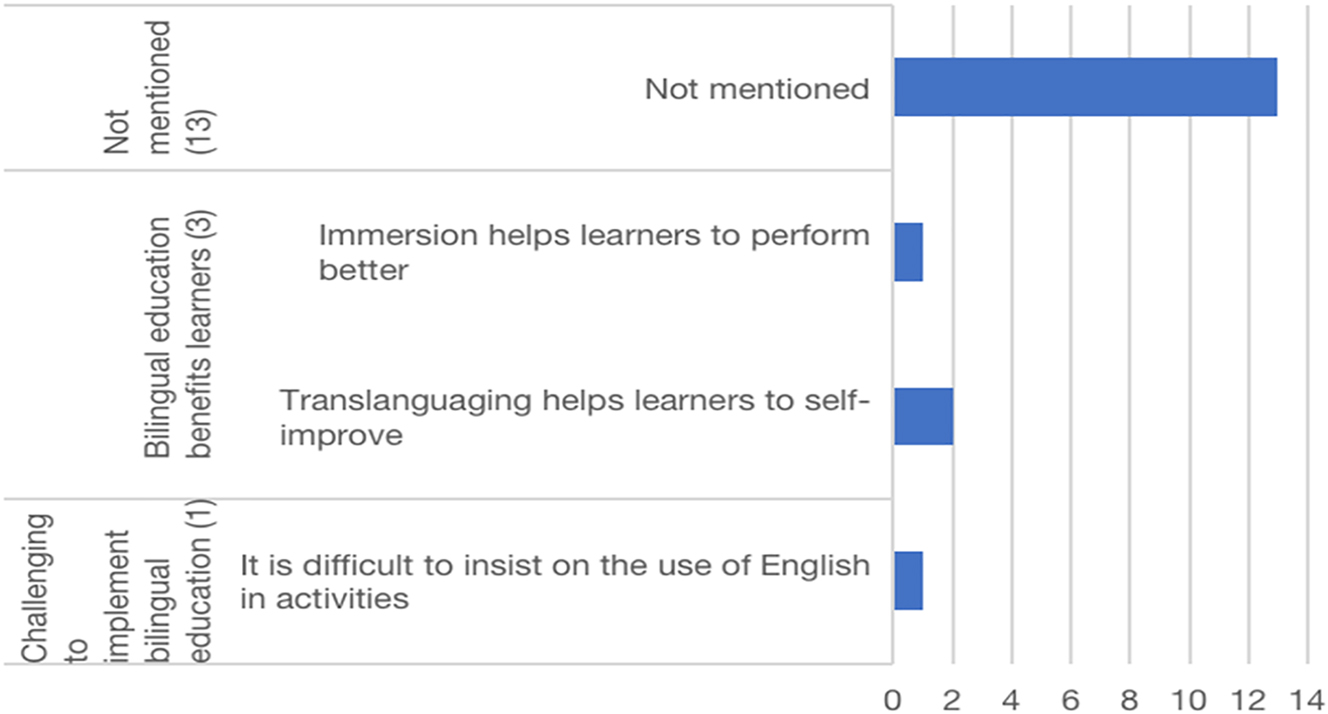

Three studies report teachers’ view that learners benefit from bilingual education (Guo 2022; Troedson and Dashwood 2018; Xiong and Feng 2018), and only one study reports that teachers think it is challenging to implement bilingual education (Wang 2021), while the remaining 12 studies do not discuss teachers’ perspectives at all (e.g., Li 2018; Yang 2018). Among the three studies coded as ‘bilingual education benefits learners’, two studies are about how translanguaging helps learners to self-improve (Guo 2022; Troedson and Dashwood 2018) and one study is about ways that immersion helps with learners’ performance (Xiong and Feng 2018). Specifically, in Troedson and Dashwood (2018) and Guo (2022), teachers indicate that translanguaging helps learners understand materials, develop critical thinking, and express themselves. Teachers in Wang (2021) find it difficult to insist on the use of English in group discussions or in-class activities among learners. Teachers mention that learners always revert from English to Chinese (Wang 2021). To sum up, teachers’ perceptions toward bilingual education are largely ignored and learners are the main stakeholders in the included studies. It is important to consider the views of other stakeholders in future research to develop a more holistic understanding of bilingual education and other educational issues (Bond et al. 2021). The coding scheme of teachers’ perceptions is presented in Appendix VII and the analysis of the teachers’ perceptions is shown in Figure 7.

Teachers’ perceptions towards bilingual education.

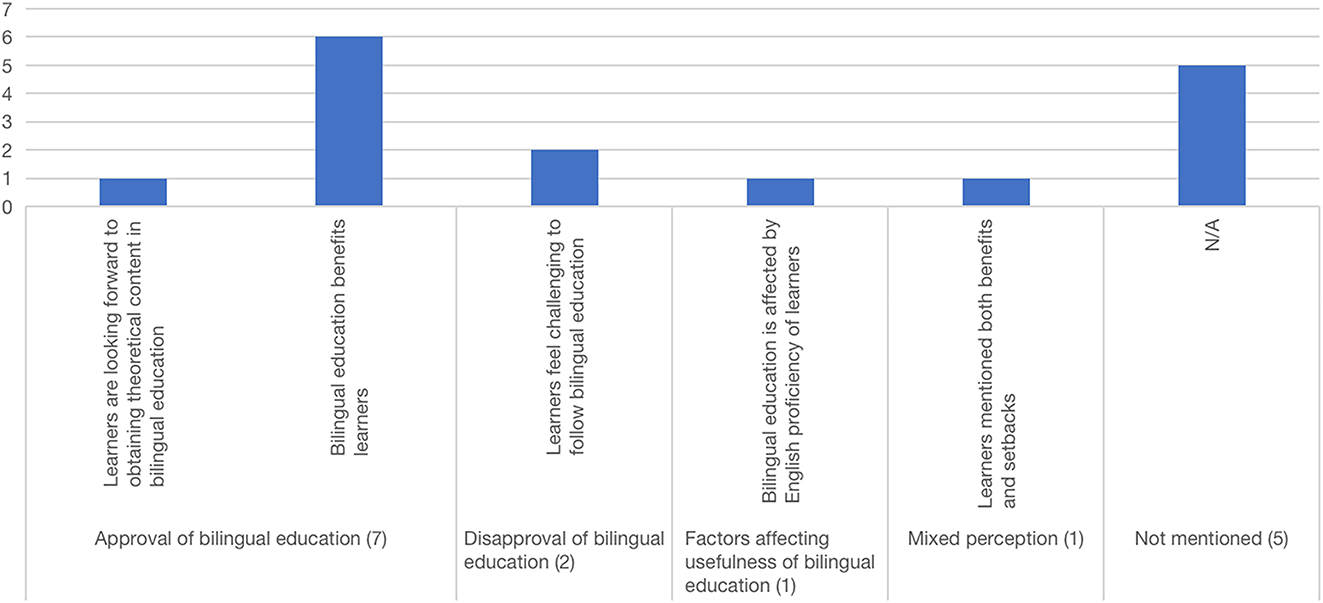

As for learners’ perceptions, seven studies mention ‘approval of bilingual education’ (e.g., Wang 2021), while two studies show ‘disapproval of bilingual education’ (Yang 2018; Yao 2022), and one study shows ‘the factor affecting usefulness of bilingual education’ (Wang et al. 2018) and ‘mixed perceptions’ (Zhou and Mann 2021) of learners respectively. The other five studies do not mention learners’ perceptions (e.g., Zuo and Walsh 2021). Bilingual education is conducive to learners in various ways. For example, learners benefit from better employment prospects, further study opportunities (Troedson and Dashwood 2018), and better comprehension of content being taught (Guo 2022). However, two studies show ‘disapproval of bilingual education’ (Yang 2018; Yao 2022). Specifically, about 33% of learners in Yang (2018) have difficulties comprehending content in two languages and following teaching schedules; most learners in Yao (2022) indicate that bilingual education is costly and detrimental to their confidence. Aside from this, learners in Yang (2018) express that poor practices of bilingual teaching make language learning stressful. *Wang et al. (2018) points out that the English proficiency of learners affects bilingual education. Additionally, Zhou and Mann (2021) present mixed perceptions toward bilingual education, in which 72% of learners believe bilingual education negatively affects their language choice. The other five studies did not mention how learners perceive bilingual education (e.g., Zuo and Walsh 2021). The coding scheme of learners’ perceptions is shown in Appendix VIII, and the analysis of learners’ perceptions is shown in Figure 8.

Learners’ perceptions towards bilingual education.

Focusing on learners’ perceptions, we investigated the benefits and challenges of bilingual education discussed in the 16 studies. Ten studies mentioned the benefits of bilingual education. Among the ten studies, five studies mentioned bilingual education is conducive to learners’ mastery of content and language (e.g., Wang 2021). Specifically, Wang (2021) mentioned that bilingual education can develop a deeper comprehension of the content without the pressure of using two languages simultaneously and facilitate learners’ acquisition of the target language. In a similar vein, learners in Troedson and Dashwood (2018) indicated that bilingual education can develop the target language. Wang and Curdt-Christiansen (2019) showed that bilingual education can facilitate disciplinary learning, and learners perform better than monolinguals (Xiong and Feng 2018). Additionally, learners’ self-improvement was mentioned by three studies (e.g., Troedson and Dashwood 2018), in particular, cognitive development and confidence. Provision of resources (n = 2) (Hiller 2021; Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019) includes communicative resources and linguistic resources. Bilingual education helps learners maintain interactions between minority culture and mainstream society (n = 2) (Wang and Lehtomäki 2022; Yu et al. 2019). Preserving heritage culture and language was mentioned by one study (Rehamo and Harrell 2018). The remaining six studies did not mention the benefits of bilingual education (e.g., Yang 2018). The coding scheme of the benefits of bilingual education is shown in Appendix IX.

Challenges of bilingual education were divided into two categories: challenges resulted from contextual factors and learner factors. Among the 16 included studies, contextual factors were mentioned by five studies (e.g., Wang 2021). First, the dominance of monolingual education and stereotypical view towards bilingual education hamper the implementation of bilingual education (n = 2) (Wang 2021; Yang 2018). The mismatch between bilingual education and societal needs (n = 3) (Wang et al. 2018; Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019; Yao 2022). The challenges of bilingual education are also caused by learner factors (n = 14). Firstly, learners’ needs in bilingual education are largely ignored (n = 3) (Guo 2022; Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019; Yang 2018). Then, bilingual education is expensive for learners from rural areas, which causes a financial burden on learners and their families (n = 2) (Wang et al. 2018; Yao 2022). Other factors include that learners lack a solid language foundation and knowledge (n = 2) (Rehamo and Harrell 2018; Wang et al. 2021), lack of confidence (n = 1) (Yao 2022), and lack of incentives (n = 1) (Rehamo and Harrell 2018). Additionally, the effectiveness of bilingual education is affected by teaching and learning factors, such as learners’ attitudes, teachers’ language proficiency level, assessment methods, and teaching methods (n = 2) (Li 2018; Yang 2018). Learners’ insufficient communication in activities among peers (n = 2) (Wang 2018; Wang and Curdt-Christiansen 2019), and insufficient teacher training (n = 1) (Rehamo and Harrell 2018) are the other two challenges. The other seven articles did not introduce challenges of bilingual education (e.g., Troedson and Dashwood 2018). The coding scheme of the challenges of bilingual education is shown in Appendix X.

4.2.3 RQ3 – How is bilingual education in China evaluated in research?

There are 11 studies coded under ‘perceptual’ (e.g., Wang 2021), which refers to the use of evaluation tools that focus on the perceptions of participants. Two studies evaluate learners’ ‘performance’ (in language tests) (Wang et al. 2021; Yu et al. 2019). The remaining three studies are about ‘perception and performance’ (Li 2018; Rehamo and Harrell 2018; Xiong and Feng 2018). A possible reason for researchers to adopt more perceptual evaluation tools is that improvement in performance, as reflected in the scores in language tests, would not be noticeable in the short run. In the two studies that specify the duration of bilingual education, the practice was implemented for less than 50 h (Guo 2022; Li 2018). This shows that bilingual education was implemented as a short-term practice rather than longitudinally. Another reason may be that 11 studies (68.75%) focus on university language learners (e.g., Wang 2021). Learners in higher education are more mature and can provide more accurate responses about their perceptions towards bilingual education. According to Bond et al. (2021), the reason perceptions of stakeholders are usually evaluated in lieu of actual learning behaviour or grade differences is because the former is easier to be carried out. The associated coding scheme can be found in Appendix XI.

Eight studies adopted questionnaires (e.g., Wang 2021), followed by seven studies using interviews (e.g., Yao 2022). Questionnaires and interviews are the two tools most frequently used, which results in 11 studies focusing on participants’ perceptions. Six studies adopted class observation (e.g., Guo 2022) and four studies adopted tests (e.g., Li 2018). Particularly, among the eight studies that use questionnaires, Wang (2021) adopted open questions about the intersection between CBI and translanguaging. Similarly, Yang (2018) also included an open question in the questionnaire about the opinions about bilingual teaching. Interviews were carried out in Yang (2018) about the different attitudes toward bilingual education among learners with varied English levels. As for tests, Li (2018) adopted Gates-MacGinitie Reading Comprehension Test and Gates-MacGinitie Vocabulary Test (pp. 902–903). They were used to measure learners’ reading comprehension and vocabulary knowledge by providing short passages with multiple-choice questions and asking learners to identify target words among items with similar meanings. The findings of most of the included studies suggest that bilingual education in China is largely effective. However, the research tools used to gauge its effectiveness focus on specific language skills (e.g., reading) rather than learners’ holistic linguistic competence. As Gibb (2015) mentioned, assessment of the four language skills (i.e., listening, reading, writing, speaking) is critiqued because it reduces language to an individualised task where communication is largely ignored, that is, ignoring the integration of social conditions involved in the use of skills. Thus, assessment of holistic linguistic competence (e.g., communicative competence) is viewed to be more contextualised than assessment of the four language skills in isolation. The coding scheme of evaluation mechanism is presented in Appendix XII.

5 Conclusion

The findings show that translanguaging and immersion are the two types of bilingual education most prevalently implemented in the 16 studies focused on bilingual education in China. Learners’ and teachers’ perceptions are the two stakeholders most frequently mentioned, in which the former is largely positive while the latter is less mentioned among the 16 studies. Additionally, most studies focus on evaluating the effectiveness of bilingual education in relation to stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences, for instance, through semi-structured interviews.

Based on the reported findings and discussion, we offer recommendations to researchers and practitioners. For researchers, a more refined categorization of bilingual education needs to be adopted in future studies. To ensure future research on bilingual education in China is ecologically valid, it is crucial to clarify and define the type of bilingual education being studied in future studies. Equally important, researchers should strive to document how bilingual education is implemented including its duration, materials used, and lesson activities. Secondly, in addition to learners’ perspectives, researchers could focus more on the perceptions of teachers and other stakeholders including parents in future studies. The current research base emphasizes learners’ perceptions, while neglecting those of teachers and other stakeholders. In addition to teachers, other stakeholders should also be taken into consideration, such as, principals, and policymakers (Bond et al. 2021). Other stakeholders’ opinions are vital to shedding a more comprehensive light on bilingual education. Third, longitudinal research and more diverse language proficiency tests can be adopted in future studies to evaluate the effectiveness of bilingual education. Most of the included studies are short-lived (Guo 2022; Li 2018), which may affect the evaluation of the effectiveness of bilingual education. Additionally, the evaluation mechanism in current bilingual education studies in China focuses more on learners’ performance in reading in lieu of other language skills. A more holistic assessment of learners’ linguistic competence in the target language needs to be included to fully gauge the usefulness of bilingual education.

For practitioners, our synthesised findings reveal that teachers need to receive adequate training to ensure effective implementation of bilingual education. The quality of bilingual education is determined by teachers’ understanding of bilingual education and their own experience as learners. Yang (2018) shows that learners are overburdened because the quality of bilingual education is unsatisfying, and Wang et al. (2018) indicated that the poor quality of bilingual education results from teachers’ limited language proficiency. Teacher training is conducive to teachers’ professional and language development, which are essential to improving the quality of bilingual education in China.

This research synthesis is not without limitations. The inclusion of only 16 studies may not fully capture the current situation of bilingual education in China. For example, the current study only focuses on primary studies about bilingual education rather than secondary studies, which may result in excluding other important work in this area of research. It also only includes studies indexed in three databases and, as the topic is on bilingual education in China, it is likely that some publications are published in Chinese, which is beyond the scope of this review. As a result, future studies could include more studies by setting a longer time frame and include publications in other languages.

Acknowledgement

This qualitative synthesis of research is based on the MSc TESOL dissertation written by QL. SWC was QL’s supervisor who oversaw the conception and implementation of the research process. Both QL and SWC were involved in the writing of this publication.

References

The references that are asterisked (*) are those that are included in this qualitative synthesis of research.Suche in Google Scholar

Anastassiou, Fotini, Georgia Andreou & Maria Liakou. 2017. Third language learning, trilingualism and multilingualism: A review. European Journal of English Language, Linguistic and Literature 4(1). 61–73.Suche in Google Scholar

Aronin, Larissa. 2005. Theoretical perspectives of trilingual education. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 171. 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2005.2005.171.7.Suche in Google Scholar

Azzam, Ziad. 2019. Dubai’s private K-12 education sector: In search of bilingual education. Journal of Research in International Education 18(3). 227–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240919892424.Suche in Google Scholar

Beardsmore, Hugo Baetens. 1995. European models of bilingual education: Practice, theory and development. In Policy and practice in bilingual education: A reader extending the foundations, 139–149. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.Suche in Google Scholar

Bond, Melissa, Svenja Bedenlier, Victoria I. Marín & Marion Händel. 2021. Emergency remote teaching in higher education: Mapping the first global online semester. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 18(1). 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00282-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Bybee, Eric Ruiz, Kathryn I. Henderson & Roel V. Hinojosa. 2014. An overview of US bilingual education: Historical roots, legal battles, and recent trends, 138–146. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2152/45900.Suche in Google Scholar

Cenoz, Jasone. 2013. Defining multilingualism. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33. 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026719051300007X.Suche in Google Scholar

Chong, Sin Wang. & H. Reinders. 2020. Technology-mediated task-based language teaching: A qualitative research synthesis. Language, Learning and Technology 24(3). 70–86.Suche in Google Scholar

Chong, S. W. & Hayo Reinders. 2021. A methodological review of qualitative research syntheses in CALL: The state-of-the-art. System 103. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102646.Suche in Google Scholar

Chong, Sin Wang & Hayo Reinders. 2022. Autonomy of English language learners: A scoping review of research and practice. Language Teaching Research. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221075812.Suche in Google Scholar

Chong, Sin Wang & Luke Plonsky. 2021. A primer on qualitative research synthesis in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly 55(3). 1024–1034. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3030.Suche in Google Scholar

Chong, Sin Wang & Luke Plonsky. 2023. A typology of secondary research in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/msjrh.Suche in Google Scholar

Collier, Virginia P. 1995. Acquiring a second language for school. Directions in Language and Education 1(4). 3–14.Suche in Google Scholar

Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2015. Bilingualism and multilingualism. In The international encyclopedia of language and social interaction, 1–11. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.10.1002/9781118611463.wbielsi108Suche in Google Scholar

Dicks, Joseph & Fred Genesee. 2017. Bilingual education in Canada. Bilingual and Multilingual Education 10. 453–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02324-3_32-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Edwards, John. 2012. Bilingualism and multilingualism: Some central concepts. In The handbook of bilingualism and multilingualism, 5–25. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.10.1002/9781118332382.ch1Suche in Google Scholar

Ellis, Elizabeth. 2006. Monolingualism: The unmarked case. Estudios de Sociolingüística 7(2). 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.v7i2.173.Suche in Google Scholar

Fleckenstein, Johanna, Sandra Kristina Gebauer & Jens Möller. 2019. Promoting mathematics achievement in one-way immersion: Performance development over four years of elementary school. Contemporary Educational Psychology 56. 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.01.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Gao, Xuesong & Wei Ren. 2019. Controversies of bilingual education in China. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22(3). 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1550049.Suche in Google Scholar

Gao, Xuesong & Wei Wang. 2017. Bilingual education in the People’s Republic of China. In Bilingual and multilingual education, 219–231. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-02258-1_16Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia. 2009. Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia & Angel Lin. 2017. Extending understandings of bilingual and multilingual education. In Bilingual and multilingual education, 1–20. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-02258-1_1Suche in Google Scholar

Geary, D. Morman & Yongrong Pan. 2003. A bilingual education pilot project among the Kam people in Guizhou Province, China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 24(4). 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630308666502.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibb, Tara. 2015. Regimes of language skill and competency assessment in an age of migration: The in/visibility of social relations and practices. Studies in Continuing Education 37(3). 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2015.1043986.Suche in Google Scholar

*Guo, Haojun. 2022. Chinese primary school students’ translanguaging in EFL classrooms: What is it and why is it needed? The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-022-00644-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Gusenbauer, Michael & Neal R. Haddaway. 2020. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Research Synthesis Methods 11(2). 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1378.Suche in Google Scholar

Hew, Khe Foon, Min Lan, Ying Tang, Chengyuan Jia & Chung Kwan Lo. 2019. Where is the “theory” within the field of educational technology research? British Journal of Educational Technology 50(3). 956–971. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12770.Suche in Google Scholar

*Hiller, Kristin E. 2021. Introducing translanguaging in an EAP course at a joint-venture university in China. RELC Journal 52(2). 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882211014997.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoffmann, Charlotte. 2001. Towards a description of trilingual competence. International Journal of Bilingualism 5(1). 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069010050010101.Suche in Google Scholar

Jawad, Najat A. Muttalib M. 2021. Bilingual education: Features & advantages. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 12(5). 735–740. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1205.12.Suche in Google Scholar

*Li, Miao. 2018. The effectiveness of a bilingual education program at a Chinese university: A case study of social science majors. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21(8). 897–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1231164.Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, Jing. 1997. Policies and practices of bilingual education for the minorities in China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 18(3). 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434639708666314.Suche in Google Scholar

Ministry of Education. 2005. Recommendations on strengthening college undergraduate programmes and enhancing the quality of instruction and Notice of Minister Zhou Ji’s Speech at the Second National Conference on Undergraduate Teaching in General Higher Education Institutions. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A08/s7056/200501/t20050107_80315.html (accessed 6 August 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Ministry of Education. 2021. Education law of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_zcfg/zcfg_jyfl/202107/t20210730_547843.html (accessed 7 August 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Osorio-O’Dea, Patricia. 2001. Bilingual education: An overview. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 1–18. Available at: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metacrs1882/.Suche in Google Scholar

Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow & David Moher. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 10(1). 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.Suche in Google Scholar

Piccardo, Enrica. 2018. Plurilingualism: Vision, conceptualization, and practices. Handbook of research and practice in heritage language education 207. 225. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44694-3_47.Suche in Google Scholar

*Rehamo, Aga & Stevan Harrell. 2018. Theory and practice of bilingual education in China: Lessons from Liangshan Yi autonomous prefecture. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23. 1254–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1441259.Suche in Google Scholar

Thornberg, Robert, Lisa, M. & KathyCharmaz. 2014. Grounded theory. In Handbook of research methods in early childhood education research methodologies, vol. 1, 405–439. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.https://www.infoagepub.com/products/Handbook-of-Research-Methods-in-Early-Childhood-Education-vol1.Suche in Google Scholar

*Troedson, David Andrew & Ann Dashwood. 2018. Bilingual use of translanguaging: Chinese student satisfaction in a transnational business degree in English. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives 17(4). 113–128.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Hao. 2010. Application of bilingual education in Chinese ESL families, 1–37. Available at: http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/43697.Suche in Google Scholar

*Wang, Jiajia, Jijia Zhang & Zhanling Cui. 2021. L2 verbal fluency and cognitive mechanism in bilinguals: Evidence from Tibetan–Chinese bilinguals. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 50(2). 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09730-7.Suche in Google Scholar

*Wang, Lijuan & Elina Lehtomäki. 2022. Bilingual education and beyond: How school settings shape the Chinese Yi minority’s socio-cultural attachments. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25(6). 2256–2268. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.1905602.Suche in Google Scholar

*Wang, Lisong, Yatong Li, Zhongmei Wang, Shiyu Shu, Yun Zhang & Yulian Wu. 2018. Improved English immersion teaching methods for the course of power electronics for energy storage system in China. IEEE Access 6. 50683–50692. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2869325.Suche in Google Scholar

*Wang, Ping. 2021. A case study of translanguaging phenomenon in CBI classes in a Chinese university context. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 31(1). 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12324.Suche in Google Scholar

*Wang, Weihong & Xiao Lan Curdt-Christiansen. 2019. Translanguaging in a Chinese–English bilingual education programme: A university-classroom ethnography. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22(3). 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1526254.Suche in Google Scholar

Wei, Rining. 2013. Chinese-English bilingual education in China: Model, momentum, and driving forces. Asian EFL Journal 15(4). 184–200.Suche in Google Scholar

*Xiong, Tao & Anwei Feng. 2018. Localizing immersion education: A case study of an international bilingual education program in south China. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23. 1125–1138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1435626.Suche in Google Scholar

*Yang, Yuqian. 2018. An investigation on the students’ opinions of bilingual teaching in universities of western China. Journal of Education and Training Studies 6(12). 1–12. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i12.3594.Suche in Google Scholar

*Yao, Chunlin. 2022. Is a one-way English immersion teaching approach equitable to those Chinese non-English major students from rural areas? Education and Urban Society 54(4). 470–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131245211027514.Suche in Google Scholar

*Yu, Hongyu, Nisha Yao, Jijia Zhang & Bing Gao. 2019. Time-course of attentional bias for culture-related cues in Mongolian-Chinese bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism 23(6). 1483–1501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006918808047.Suche in Google Scholar

*Zhou, Xiaozhou Emily & Steve Mann. 2021. Translanguaging in a Chinese university CLIL classroom: Teacher strategies and student attitudes. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 11(2). 265–289. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.2.5.Suche in Google Scholar

*Zuo, Miaomiao & Steve Walsh. 2021. Translation in EFL teacher talk in Chinese universities: A translanguaging perspective. Classroom Discourse. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2021.1960873.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0194).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue: Power, Linguistic Discrimination and Inequality in English Language Teaching and Learning (ELTL): Reflection and Reform for Applied Linguistics from the Global South; Guest Editors: Fan Gabriel Fang and Sender Dovchin

- Editorial

- Reflection and reform of applied linguistics from the Global South: power and inequality in English users from the Global South

- Research Articles

- Translingual English discrimination: loss of academic sense of belonging, the hiring order of things, and students from the Global South

- Applied linguistics from the Global South: way forward to linguistic equality and social justice

- English high-stakes testing and constructing the ‘international’ in Kazakhstan and Mongolia

- The mundanity of translanguaging and Aboriginal identity in Australia

- Multimodal or multilingual? Native English teachers’ engagement with translanguaging in Hong Kong TESOL classrooms

- Epistemic injustice and neoliberal imaginations in English as a medium of instruction (EMI) policy

- Commentary

- Transidiomatic favela: language resources and embodied resistance in Brazilian and South African peripheries

- Special Issue: Translanguaging Outside the Centre: Perspectives from Chinese Language Teaching; Guest Editor: Danping Wang

- Editorial

- Translanguaging outside the centre: perspectives from Chinese language teaching

- Research Articles

- Translanguaging as a decolonising approach: students’ perspectives towards integrating Indigenous epistemology in language teaching

- Translanguaging as sociolinguistic infrastructuring to foster epistemic justice in international Chinese-medium-instruction degree programs in China

- Translanguaging as a pedagogy: exploring the use of teachers’ and students’ bilingual repertoires in Chinese language education

- A think-aloud method of investigating translanguaging strategies in learning Chinese characters

- Translanguaging pedagogies in developing morphological awareness: the case of Japanese students learning Chinese in China

- Facilitating learners’ participation through classroom translanguaging: comparing a translanguaging classroom and a monolingual classroom in Chinese language teaching

- A multimodal analysis of the online translanguaging practices of international students studying Chinese in a Chinese university

- Special Issue: Research Synthesis in Language Learning and Teaching; Guest Editors: Sin Wang Chong, Melissa Bond and Hamish Chalmers

- Editorial

- Opening the methodological black box of research synthesis in language education: where are we now and where are we heading?

- Research Article

- A typology of secondary research in Applied Linguistics

- Review Articles

- A scientometric analysis of applied linguistics research (1970–2022): methodology and future directions

- A systematic review of meta-analyses in second language research: current practices, issues, and recommendations

- Research Article

- Topics, publication patterns, and reporting quality in systematic reviews in language education. Lessons from the international database of education systematic reviews (IDESR)

- Review Article

- Bilingual education in China: a qualitative synthesis of research on models and perceptions

- Regular Issue Articles

- An interactional approach to speech acts for applied linguistics

- “Church is like a mini Korea”: the potential of migrant religious organisations for promoting heritage language maintenance

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue: Power, Linguistic Discrimination and Inequality in English Language Teaching and Learning (ELTL): Reflection and Reform for Applied Linguistics from the Global South; Guest Editors: Fan Gabriel Fang and Sender Dovchin

- Editorial

- Reflection and reform of applied linguistics from the Global South: power and inequality in English users from the Global South

- Research Articles

- Translingual English discrimination: loss of academic sense of belonging, the hiring order of things, and students from the Global South

- Applied linguistics from the Global South: way forward to linguistic equality and social justice

- English high-stakes testing and constructing the ‘international’ in Kazakhstan and Mongolia

- The mundanity of translanguaging and Aboriginal identity in Australia

- Multimodal or multilingual? Native English teachers’ engagement with translanguaging in Hong Kong TESOL classrooms

- Epistemic injustice and neoliberal imaginations in English as a medium of instruction (EMI) policy

- Commentary

- Transidiomatic favela: language resources and embodied resistance in Brazilian and South African peripheries

- Special Issue: Translanguaging Outside the Centre: Perspectives from Chinese Language Teaching; Guest Editor: Danping Wang

- Editorial

- Translanguaging outside the centre: perspectives from Chinese language teaching

- Research Articles

- Translanguaging as a decolonising approach: students’ perspectives towards integrating Indigenous epistemology in language teaching

- Translanguaging as sociolinguistic infrastructuring to foster epistemic justice in international Chinese-medium-instruction degree programs in China

- Translanguaging as a pedagogy: exploring the use of teachers’ and students’ bilingual repertoires in Chinese language education

- A think-aloud method of investigating translanguaging strategies in learning Chinese characters

- Translanguaging pedagogies in developing morphological awareness: the case of Japanese students learning Chinese in China

- Facilitating learners’ participation through classroom translanguaging: comparing a translanguaging classroom and a monolingual classroom in Chinese language teaching

- A multimodal analysis of the online translanguaging practices of international students studying Chinese in a Chinese university

- Special Issue: Research Synthesis in Language Learning and Teaching; Guest Editors: Sin Wang Chong, Melissa Bond and Hamish Chalmers

- Editorial

- Opening the methodological black box of research synthesis in language education: where are we now and where are we heading?

- Research Article

- A typology of secondary research in Applied Linguistics

- Review Articles

- A scientometric analysis of applied linguistics research (1970–2022): methodology and future directions

- A systematic review of meta-analyses in second language research: current practices, issues, and recommendations

- Research Article

- Topics, publication patterns, and reporting quality in systematic reviews in language education. Lessons from the international database of education systematic reviews (IDESR)

- Review Article

- Bilingual education in China: a qualitative synthesis of research on models and perceptions

- Regular Issue Articles

- An interactional approach to speech acts for applied linguistics

- “Church is like a mini Korea”: the potential of migrant religious organisations for promoting heritage language maintenance