Abstract

Objectives

Painful diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are common in the health care setting. Eliminating, or at least, minimizing the pain associated with various procedures should be a priority. Although there are many benefits of providing local/topical anesthesia prior to performing painful procedures, ranging from greater patient/family satisfaction to increased procedural success rates; local/topical anesthetics are frequently not used. Reasons include the need for a needlestick to administer local anesthetics such as lidocaine and the long onset for topical anesthetics. Vapocoolants eliminate the risks associated with needlesticks, avoids the tissue distortion with intradermal local anesthetics, eliminates needlestick pain, have a quick almost instantaneous onset, are easy to apply, require no skills or devices to apply, are convenient, and inexpensive. The aims of this study were to ascertain if peripheral intravenous (PIV) cannulation pain would be significantly decreased by using a vapocoolant (V) versus sterile water placebo (S) spray, as determined by a reduction of at least >1.8 points on numerical rating scale (NRS) after vapocoolant versus placebo spray, the side effects and incidence of side effects from a vapocoolant spray; and whether there were any long term visible skin abnormalities associated with the use of a vapocoolant spray.

Materials and methods

Prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of 300 adults (ages 18-80) requiring PIV placement in a hospital ED, randomized to S(N = 150)or V(N = 150) prior to PIV. Efficacy outcome was the difference in PIV pain: NRS from 0 (none) to worst (10). Safety outcomes included a skin checklist for local adverse effects (i.e., redness, blanching, edema, ecchymosis, itching, changes in skin pigmentation), vital sign (VS) changes, and before/after photographs of the PIV site.

Results

Patient demographics (age, gender, race), comorbidity, medications, and vital signs; and PIV procedure variables (e.g., IV needle size, location, number of IV attempts, type and experience of healthcare provider performing the IV) were not significantly different for the two groups. Median (interquartile range) PIV pain was 4 (2,7) (S) and 2 (0,4) (V) (P< 0.001). Skin checklist revealed minimal erythema: S 0% (N = 0/150), V: 2.7% (4/150), which resolved within 5min, and no blanching, skin pigmentation changes, itching, edema, or ecchymosis. Photographs at 5-10 min revealed no visible skin changes in any patient (N=300), vapocoolant (N = 150) or placebo groups (N = 150). Complaints (N = 26) were coolness/cold feeling S 8.7% (N = 13), V 7.3% (N = 11), coolness/numbness S 0% (N =0), V 0.7% (N =1), and burning S 0.7% (N =1), V 0 (0%). Patient acceptance of the vapocoolant spray was high: 82% (123/150) of the patients stated they would use the spray in the future, while only 40.7% (61/150) of the placebo group stated they would use the placebo spray in the future.

Conclusions and Implications

Vapocoolant spray significantly decreased peripheral intravenous cannulation pain in adults versus placebo spray and was well tolerated with minor adverse effects that resolved quickly. There were no significant differences in vital signs and no visible skin changes documented by photographs taken within 5-10 min postspray/PIV.

1 Introduction

Painful diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are frequently performed in the emergency department (ED) [1,2]. Suboptimal pain management or oligoanesthesia has been noted as “a problem for emergency medicine” [3]. Failure to adequately treat pain has significant short-term and long-term consequences [4,5]. This oligoanesthesia [6,7,8] extends to painful procedures [9,10,11]. Health care providers frequently fail to provide adequate anesthesia prior to painful procedures even when patients and families indicate that they would like to receive analgesia before painful procedures including needlestick procedures [1,9,10,11,12,13].

Benefits of adequate analgesia include increased patient/family satisfaction and increased procedural success [6,14,15,16]. Yet topical anesthesia prior to procedures is underused [10,11,14].

Topical skin refrigerants, or vapocoolants, have some advantages over other options for local anesthesia including eliminates the risk of needlestick injury, avoids tissue distortion, avoids the pain of intradermal anesthetics, rapid almost instantaneous onset (some topical analgesic creams take up to an hour to achieve clinically significant pain relief), easy to apply, no need for devices for administration (which have been associated with delayed local soreness and edema), less administration time, greater staff convenience, decreased ED length of stay, and is inexpensive [1,5,10,17,18,19,20,21].

This study sought to determine the efficacy and safety of a vapocoolant spray in adults undergoing peripheral intravenous cannulation (PIV). We hypothesized that pain of PIV would be at least 1.8 points lower after vapocoolant spray compared to placebo spray and that there would be no permanent visible changes associated with the use of a vapocoolant spray [22,23].

2 Materials and methods

Thus study, termed IMPACT PAIN II for “IMproved PAtient Comfort Trial: Pain Assessment in Intravenous CaNnulation” was an investigator-initiated study supported by a research grant from the Gebauer Company. The sponsor had no involvement in the study other than funding and supplying the spray cans used for the administration of the placebo spray and the vapocoolant spray.

2.1 Study design and setting

This was a prospective, double blind, randomized controlled efficacy and safety trial conducted at an urban, academic, tertiary care referral hospital conducted from August 2012 to December 2014. The study was approved by the institutional review board and all patients gave written informed consent.

2.2 Study population

Adults (ages 18-80 years) undergoing peripheral intravenous cannulation (PIV) in the ED were eligible for enrollment in the study. Inclusion criteria were: patient undergoing PIV, mentally competent patient able to understand the consent form, and clinically stable. Patients were excluded from the study if any of the following criteria were met: allergy to the spray components (e.g. 1,1,1,3,3-pentafluoropropane or 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane), critically ill or unstable, extremes of age (pediatric <18 years or elderly geriatric >80 years), pregnant, previous experience with any vapocoolant spray, PIV site located in area of compromised blood supply, PIV site located in area of insensitive skin, patient intolerant of cold or with hypersensitivity to cold, and patient unwilling to give consent. Examples of PIV sites located in areas of compromised blood supply would include patients with peripheral vascular disease, gangrene, Raynaud’s disease or Buerger’s disease. Examples of patients with insensate or abnormal sensation of the skin would include patients with a peripheral neuropathy. None of the patients recently received an analgesic (such as an opioid) prior to the venipuncture. Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects.

This was a convenience sample since patients were enrolled when the ED research staff was available, e.g. day and evening shifts on weekdays and weekends. The ED research staff members conducting the study were not involved in the care of the patient or in starting the PIV line. The primary researcher was not present and not involved in patient enrollment or data analysis. A research assistant approached the patient if the patient was in the appropriate age range (18-80 years) and if the patient was clinically stable (e.g. not in shock or respiratory distress or had no alteration of mental status), and obtained informed written consent.

The past medical history including comorbidities, current medications and characteristics of the PIV itself were listed in order to determine if the patient populations for the two groups were well matched at baseline since comorbidity and medication use, and the PIV itself could possibility affect the difficulty of the PIV procedure and the response to the pain of the PIV.

Patients were randomized to either sterile water placebo spray (Nature’s Tears ) or to vapocoolant spray (1,1,1,3,3-pentafluoropropane and 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane) (Gebauer’s Pain Ease® Medium Stream). The application of the spray in all patients was completed by one of two trained research assistants whose job was to enroll patients and to standardize administration of the topical spray. After prepping and cleansing the PIV site, the spray was applied in the same manner for all patients, both placebo and vapocoolant subjects, as recommended by the manufacturer. The specific technique of spray application for both the placebo spray and the vapocoolant spray was: hold the can 3-7 in from the PIV site, spray onto the PIV site steadily 4-10 s or until the skin begins turning white, whichever comes first (the anesthetic effect is complete at this time), then, immediately perform the IV needlestick for the IV line. There is about a one minute time frame to complete the PIV cannulation since the topical anesthetic lasts only about one minute.

The spray cans were not identified as to whether they were the placebo spray or the vapocoolant spray and thus, were blinded to both the subjects, the research assistants applying the spray and the health care providers performing the PIV. The actual PIV was done by the ED staff and not by the two research associates.

Randomization was accomplished utilizing a computer random number generator with block randomization using randomly varied block sizes of 20 or 30. The spray cans were supplied from outside the ED in varied block sizes such that the randomization was not done by or knowledgeable to the ED research staff performing the actual patient enrollment and data collection in order to maintain allocation concealment.

2.3 Data collection and processing

All data was collected by trained research associates who had no patient care duties. Their research duties included patient enrollment, data recording and application of the spray. They recorded on standardized case report forms: the demographics, PIV procedural data, vital signs (completed by ED nursing staff), clinical variables (from the electronic medical record), all side effects/complications, and pain scales (e.g. numeric rating scale [NRS]) as reported by the patients: NRS immediately post spray/pre PIV cannulation, and NRS for the pain of PIV cannulation. They completed the standardized checklist and took before and after photographs of the IV site to document any visible skin changes.

All data was entered into a REDCap database and then analyzed using R software (version 3.1.1) by a biostatistician. Continuous variables were summarized using means with variability assessed using standard deviations. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Tests for differences of continuous variables were done using Welch 2-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon’s rank-sum tests. Tests on categorical variables were done using either Pearson’s chi-squared tests with Yates continuity correction or Fisher’s exact test for count data. Significance was at P < 0.05 and the results of testing were given by P-values and/or confidence intervals.

2.4 Outcome measures

The primary efficacy outcome was the pain of PIV on a verbal NRS scale ranging from 0 (none) to 10 (worst). The primary safety measures were the documentation of any and all adverse effects/complications and vital signs. Secondary safety measures included a skin checklist for any changes (rated none, mild, moderate, severe) of the skin: redness, blanching or pallor, changes in skin pigmentation, itching, edema, or other (such as ecchymosis) done immediately post spay, NRS post spray/pre PIV, and photographs of the PIV site done pre and 5-10 min post application of the spray/post PIV for any visible skin changes.

According to previous studies, a change in NRS of 1.3 or greater is deemed clinically significant [22,23], while a previous pediatric IV study found a difference of 18 on a 0-100 mm VAS scale between placebo vs. vapocoolant spray [16]. Therefore, we decided to use a decrease of >1.8 on the NRS since this would include the meaningful difference. To detect a decrease of 1.8 on the NRS, a sample size of 277 was chosen, assuming a 2-tailed test, power of 80%, and type I error rate of 0.05. The sample size was increased to 300 (150 per group) to compensate for potential dropouts or protocol deviations.

3 Results

3.1 Study subjects

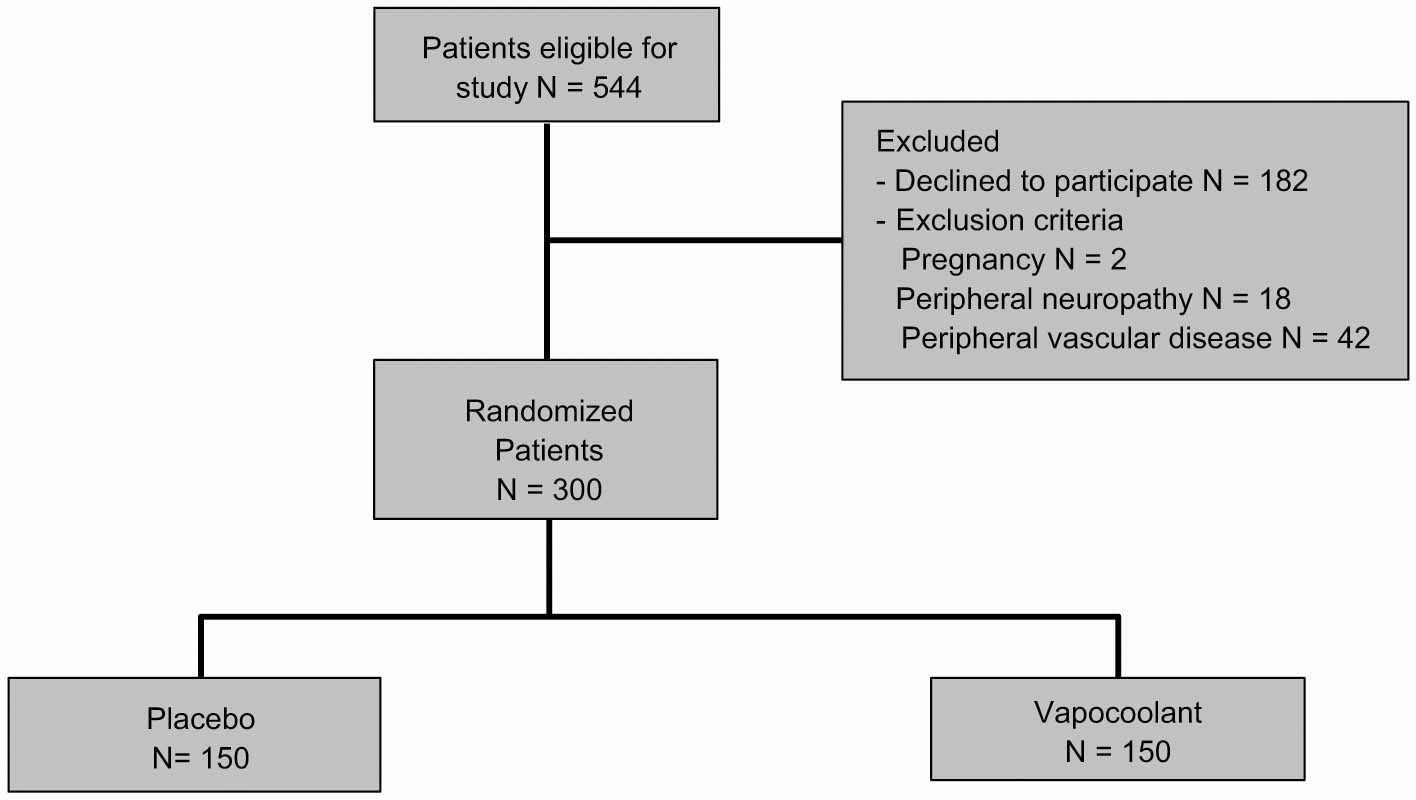

Of the 544 patients recruited to the study, 300 consented, were randomized and received their allocated treatment: 150 patients received sterile water spray (placebo arm) and 150 patients received vapocoolant spray (treatment arm) (Fig. 1). For all 300 study subjects, the mean age (±SD) was 42.8 (±16.6) years (range 18-80 years), with 120 males and 180 females: 150 African-Americans, 137 Caucasians, and 13 other. The patients in the two study arms had similar baseline characteristics with no significant differences in any of the demographic variables (age, gender, race); or clinical characteristics (comorbidities, or medications) (Table 1). The characteristics of the PIV itself were similar between the two groups with no significant differences in PIV location, PIV needle gauge, PIV success rate, number of PIV attempts, difficulty of PIV, or with the health care providers performing the PIV (years’ experience and role in ED) except for spray time: 7.5 (V) vs. 10 s (S). The procedure (e.g. PIV) was performed in <1 min in all patients (Table 2).

Participant flow diagram according to the consolidated standards of reporting trial guidelines.

Patient demographics, clinical variables, vital signs.

| Placebo saline spray (N = 150 patients) | Vapocoolant spray (N = 150 patients) | P-value | All patients (N =300 patients) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years): mean (±SD) | 42.7 (± 16.6) | 43.0 (± 16.6) | 0.91 | 42.8 (±16.6) |

| Gender: number of patients (%) | Male 64 (42.7%) | Male 56 (37.3%) | 0.41 | Male 120 (40%) |

| Female 86 (57.3%) | Female 94 (62.7%) | Female 180 (60%) | ||

| Race: number of patients (%) | African-American 73 | African-American | >0.99 | African-American |

| (48.7%) | 77 (51.3%) | 150 (50%) | ||

| Caucasian 68 (45.3%) | Caucasian 69 | Caucasian 137 | ||

| Other 9 (6%) | (46.0%) | (45.7%) | ||

| Other 4 (2.7%) | Other 13 (4.3%) | |||

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 65 (43.3%) | 65 (43.3%) | >0.99 | 130 (43.3%) |

| Diabetes | 35 (23.3%) | 34 (22.7%) | >0.99 | 69 (23%) |

| COPD | 11 (7.3%) | 11 (7.3%) | >0.99 | 22 (7.3%) |

| Cancer | 22 (14.7%) | 20 (13.3%) | 0.87 | 42 (14.3%) |

| Current chemotherapy | 4 (2.7%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0.68 | 6 (2%) |

| Past chemotherapy | 5 (3.33%) | 3 (2%) | 0.72 | 8 (2.7%) |

| Current radiation therapy | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0.67 | 2 (1%) |

| Past radiation therapy | 6 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 0.50 | 9 (3%) |

| Status post mastectomy | 1 (0.7%) | 4 (2.7%) | 0.37 | 5 (1.7%) |

| Obesity | 21 (14%) | 35 (23.3%) | 0.54 | 56 (18.7%) |

| Renal disease | 5 (3.3%) | 7 (4.7%) | 0.77 | 12 (4%) |

| Hemodialysis | 4 (2.7%) | 3 (2%) | >0.99 | 7 (2.3%) |

| Sickle cell disease | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | >0.99 | 3 (1%) |

| Grave’s disease | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | >0.99 | 1 (0.3%) |

| Gout | 6 (4%) | 8 (5.3%) | 0.78 | 14 (4.7%) |

| Osteoarthritis | 9 (6%) | 11 (7.3%) | 0.82 | 20 (6.7%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5 (3.3%) | 7 (4.7%) | 0.77 | 12 (4%) |

| Systemic lupus erythromatosis | 6 (4.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0.13 | 7 (2.3%) |

| Sarcoidosis | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | >0.99 | 1 (0.3%) |

| Scleroderma | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | >0.99 | 1 (0.3%) |

| Polymyositis | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | >0.99 | 1 (0.3%) |

| Spondyloarthropathy | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | >0.99 | 2 (0.7%) |

| Other rheumatologic disorders | 2 (1.3%) | 3 (2%) | >0.99 | 5 (1.7%) |

| GI disorders: Crohn’s | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | >0.99 | 2 (0.7%) |

| GI disorders: celiac disease | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | >0.99 | 1 (0.3%) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | >0.99 | 3 (1%) |

| History of blood clot in upper | 4 (2.7%) | 4 (2.7%) | >0.99 | 4 (2.7%) |

| extremity | ||||

| IV drug use | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.25 | 3 (1%) |

| Dehydration in last 72 h | 23 (15.3%) | 26 (17.3%) | 0.75 | 49 (16.3%) |

| Surgery in last 30 days | 9 (6%) | 13 (8.7%) | 0.51 | 22 (7.3%) |

| Medications | ||||

| Acetaminophen | 18 (12%) | 18 (12%) | >0.99 | 36 (12%) |

| Opioids (acetaminophen-oxycodone | 34 (22.7%) | 33 (22%) | >0.99 | 67 (22.3%) |

| or acetaminophen-hydrocodone) | ||||

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory | 25 (16.7%) | 28 (18.7%) | 0.76 | 53 (17.7%) |

| drugs (NSAIDS) | ||||

| Anticonvulsants | 17 (11.3%) | 12 (8%) | 0.43 | 29 (9.7%) |

| Antidepressants | 14 (9.3%) | 18 (12%) | 0.57 | 32 (10.7%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 13 (8.7%) | 10 (6.7%) | 0.66 | 23 (7.7%) |

| Corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone) | 9 (6%) | 9 (6%) | >0.99 | 9 (6%) |

| Vital signs | ||||

| Blood pressure: systolic (mm Hg), | 139.1 (±24.0) | 135.7 (±21.9) | 0.20 | 137.4 (±23.0) |

| mean (±SD) | ||||

| Blood pressure: diastolic (mm Hg), | 80.0 (±15.0) | 78.0 (±15.3) | 0.26 | 79.0 (±15.2) |

| mean (±SD) | ||||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 84.5 (±15.8) | 85.7 (±16.4) | 0.52 | 85.1 (±16.1) |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 18.0 (±1.9) | 18.3 (±2.6) | 0.29 | 18.2 (±2.3) |

Characteristics ofthe peripheral intravenous cannulation procedure.

| Placebo spray (N = 150 patients) | Vapocoolant spray (N = 150 patients) | P-value | All patients (N =300 patients) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needle size | 0.20 | |||

| 18 gauge | 39 (26%) | 35 (23.3%) | 74 (24.7%) | |

| 20 gauge | 100 (66.7%) | 103 (68.7%) | 203 (67.6%) | |

| 22 gauge | 11 (7.3%) | 12 (8%) | 23 (7.7%) | |

| Location of PIV | 0.16 | |||

| Hand | 5 (3.3%) | 8 (5.3%) | 13 (4.3%) | |

| Antecubital fossa | 88 (58.6%) | 94 (62.7%) | 182 (61%) | |

| Forearm | 50 (33.3%) | 44 (29.3%) | 94 (31.3%) | |

| Wrist | 7 (4.7%) | 4 (2.7%) | 11 (3.7%) | |

| Total number of PIV attempts | 0.58 | |||

| One | 114 (76%) | 124 (82.7%) | 238 (79.3%) | |

| Two | 27 (18%) | 17 (11.3%) | 44 (14.7%) | |

| Three | 5 (3.3%) | 7 (4.7%) | 12 (4%) | |

| Four | 4 (2.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | 5 (1.7%) | |

| Five | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Job description of healthcare provider starting the PIV | 0.97 | |||

| Paramedic | 91 (60.7%) | 89 (59.3%) | 179 (59.7%) | |

| Registered nurse | 58 (38.7%) | 60 (40%) | 117 (39%) | |

| Licensed practical nurse | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | |

| Number years experience of individual performing the PIV, mean ±SD [95% CI] | [95% CI] | 0.83 | [95% CI] | |

| 0-2 years | 13 (8.7%) | 11 (7.3%) | 24 (8%) | |

| 3-5 years | 34 (23.3%) | 38 (25.3%) | 72 (24%) | |

| 5-10 years | 47 (31.3%) | 51 (34%) | 99 (33%) | |

| 10+ years | 56 (37.3%) | 50 (33.3%) | 106 (35.3%) | |

| Patient question | ||||

| Would you use this spray for future IVs? | 61 (49.7%) | 123 (82%) | <0.001 | 184 (61.3%) |

| Spray time seconds median [P25, P75] | 10 [8,10] | 7.5 [6,10] | <0.001 | 10 [7,10] |

3.2 Results: efficacy

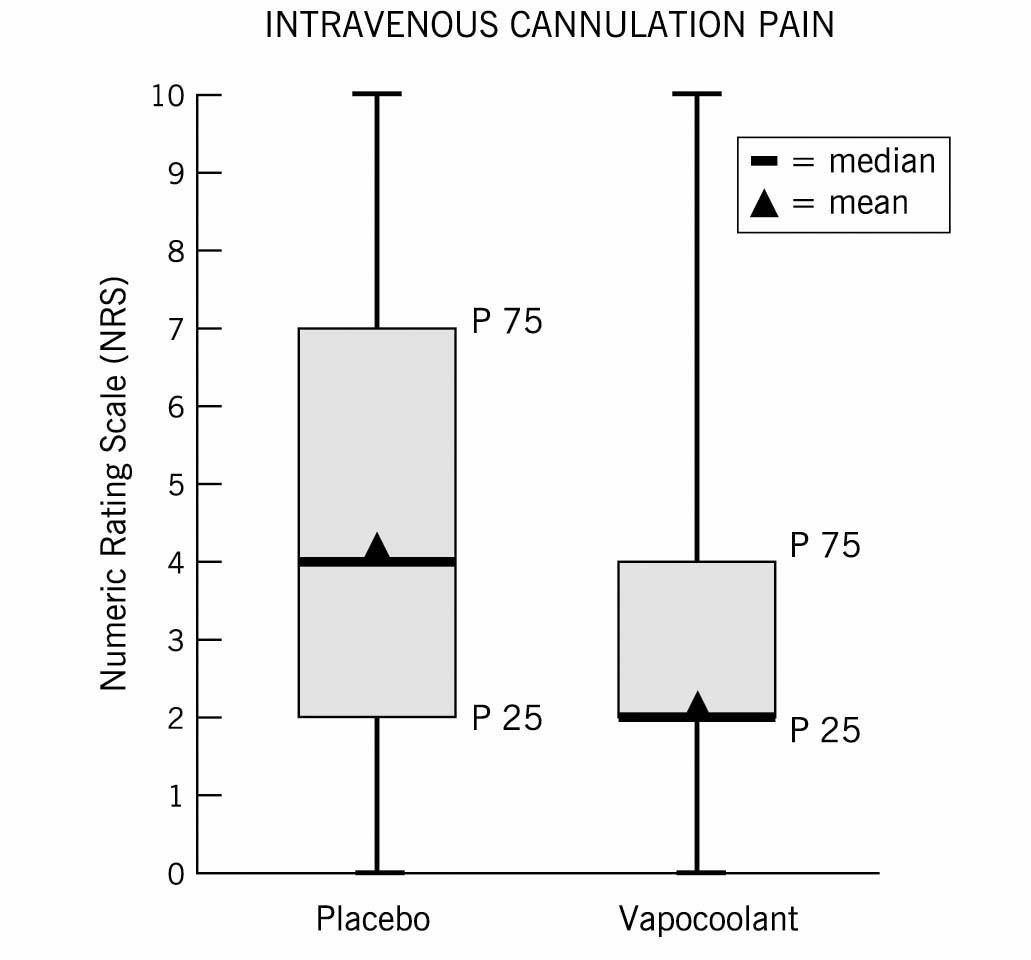

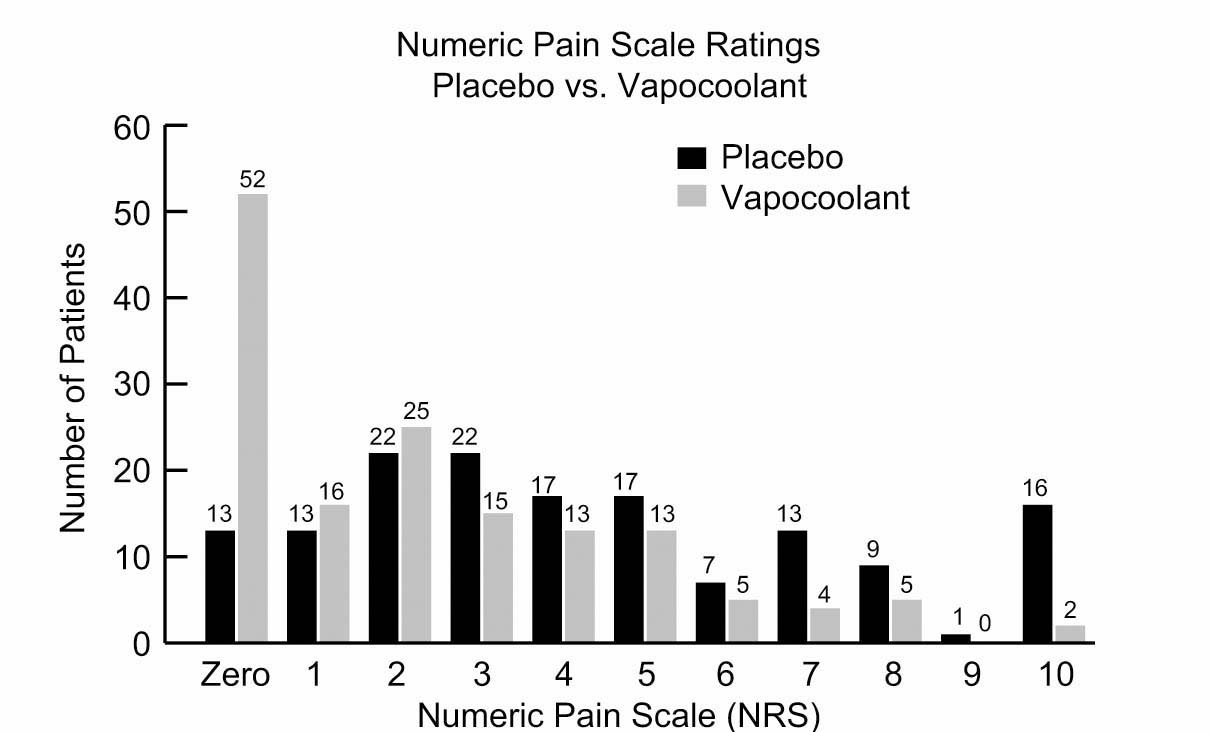

The median NRS interquartile range (IQR) for PIV cannulation pain was 4 (2-7) for the placebo spray group vs. 2 (0-4) for the vapocoolant spray group (P< 0.001) (Fig. 2). Over one-third (35% = 52/150) of the patients in the vapocoolant group reported no pain (NRS = 0) for their IV start compared with 8.7% (13/150) for the placebo group (P< 0.001) (Fig. 3).

The pain of peripheral intravenous cannulation (PIV) on numeric rating scale (NRS): box and whisker plots of NRS for the placebo spray and the vapocoolant spray. The median is the center line, the boxes are the 25th to 75th percentile and the triangle is the mean.

Frequencies of the numeric rating scale (NRS) for the placebo spray and the vapocoolant spray for all the points (0 to 10) on the NRS.

3.3 Results: safety

There were no significant differences in vital signs between the two groups (Table 1). There were 26 complaints (Table 3). In the placebo group, 13 (8.7%) complained of coolness/cold feeling, and 1 (0.7%) had burning at the site. In the vapocoolant group, 11 (7.3%) complained of coolness/cold feeling and 1 (0.7%) complained of coolness and numbness. There were no serious side effects/adverse events or complications and minor adverse effects, such as redness of the skin, resolved in <5 min.

Patient comments: side effects.

| Side effect | Placebo spray (N =150) | Vapocoolant spray (N = 150) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coolness/cold feeling | 13 (8.7%) | 11 (7.3%) | 0.63 |

| Coolness and numbness | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | >0.99 |

| Burning | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | >0.99 |

| No comment | 136 (90.7%) | 138 (92%) | >0.99 |

The skin checklist completed immediately post spray revealed minimal redness in 4 patients in the vapocoolant group (4/150 = 2.7%), which resolved within 5 min post spray application/post PIV and no redness in the saline placebo group. There was no blanching, skin pigmentation changes, itching, edema, bruising, or other visible skin changes reported for either group (Table 4).

Skin checklist: immediately postspray.

| Placebo spray (N = 150 patients) | Vapocoolant spray (N = 150 patients) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Redness | 0.13 | ||

| None | 150 | 146 (97.3%) | |

| Minimal | 0 | 4 (2.7%) | |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | |

| Blanching | |||

| None | 150 | 150 | >0.99 |

| Minimal | 0 | 0 | |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | |

| Changes in skin pigmentation | |||

| None | 150 | 150 | >0.99 |

| Mild | 0 | 0 | |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | |

| Itching | |||

| None | 150 | 150 | >0.99 |

| Mild | 0 | 0 | |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | |

| Edema | |||

| None | 150 | 150 | >0.99 |

| Mild | 0 | 0 | |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | >0.99 | ||

| None | 0 | 0 | |

| Mild | 0 | 0 | |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe | 0 | 0 |

Immediately post spray/pre PIV cannulation, the median NRS was the same for the placebo spray and for the vapocoolant spray at 0 and the IQR was between 0 and 0 for the placebo spray and 0 and 2 for the vapocoolant spray (P< 0.001). Patients were asked “Would you want to use this spray for future IVs?” Of the vapocoolant group, 82% (123/150) responded affirmatively versus 40.7% (61/150) of the placebo group (P< 0.001) (Table 2). Before-and-after photographs of the spray/PIV site revealed no visible skin changes in any of the patients no matter what the gender, ethnicity, or age and no matter whether they received the placebo or vapocoolant spray.

4 Discussion

Painful diagnostic and therapeutic medical procedures, especially needlestick procedures, are frequently performed in the ED [1,11,13,14]. Unfortunately, health care providers frequently fail to provide adequate analgesia prior to painful procedures, even when patients indicated that they would like to receive analgesia before painful procedures including needlestick procedures [6]. Vapocoolants, also known as topical skin refrigerants, have some advantages over other options for local anesthesia including avoids the risk of needlestick injury and the pain of the needlestick injection of intradermal local anesthetics, rapid almost instantaneous onset (some topical creams take up to an hour for effect), easy to apply (no need for devices for application) and is inexpensive. Recent evidence from both human and animal studies indicates that topical refrigerant sprays are safe, e.g. have no lasting skin abnormalities with proper application and no effect on the microcirculation [21,24].

This prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial demonstrated a significant decrease in the acute pain of PIV cannulation in adult ED patients after application of topical vapocoolant spray (1,1,1,3,3-pentafluoropropane and 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane) compared with placebo spray and safety with no visible skin abnormalities 5-10 min after spray application. Other studies have considered the issue of skin sterility with application of a vapocoolant spray and concluded there was no increased risk of infection when a topical vapocoolant spray was used [25,26]. The analgesic effect of vapocoolants is thought to be via rapid cooling [27] by decreasing “both initiation and conduction impulses in surrounding (peripheral) sensory nerve”, thereby interrupting the nocioceptive input into the spinal cord and raising the pain threshold [28]. In an animal study, cryotherapy or cold therapy increases the pain threshold and decreases the nerve conduction velocity [29]. Vapocoolant sprays are thought to produce “the sensation of cooling and analgesia through activation of transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels in cold-sensitive peripheral sensory neurons” [30].

This study is unique in several respects. This is the first large (N = 300) prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial in an ED patients, which looked at both safety and efficacy. By comparison, an earlier study that used health care provider volunteers, had a much smaller N (only 38 volunteers) and was in a non-acute care setting (healthy volunteers, not actual ED patients), used a different vapocoolant spray (e.g. ethyl chloride), and did not address the safety issue. However, they also found a decrease in pain of PIV cannulation with the use of a vapocoolant spray: verbal NRS (median, IQR) scores were placebo (sterile water spray) 4 (2-5) vs. ethyl chloride spray 2 (1-4) [31].

A study in a different age group, children (ages 6-12 years) in a Canadian pediatric ED also found a significant decrease in the pain of PIV cannulation with the use of the 1,1,1,3,3-pentafluoropropane and 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane spray compared to a placebo saline spray: (mean difference 19 mm, 95% confidence interval [CI] 6-32 mm, P<0.01) using a 100-mm color visual analogue scale. Moreover, the first attempt PIV cannulation success rate was significantly greater for the vapocoolant spray (85%) than placebo spray (62.5%) (mean difference 22.5%, 95% CI 3.2-39.9%, P = 0.03). The number needed to treat to prevent one cannulation failure was 5 [16].

Another smaller non-blinded Australian study using a different vapocoolant; COLD spray ; a mixture of propane, butane and pentane; in adult ED patients comparing subcutaneous lidocaine vs. COLD spray also found significantly greater PIV success rates for the COLD spray group (83.6%) vs. lidocaine group (67.3%) (P= 0.005) and a significantly decreased pain of PIV insertion (P < 0.001) with the COLD spray [19].

The pain of PIV cannulation in our trial is similar to that reported in other studies. The study from Scotland that compared 3 groups: no treatment, intradermal lidocaine and ethyl chloride for PIV cannulation on a 0-10 VAS scale in adult females undergoing outpatient gynecologic surgery found the pain of PIV insertion with no treatment was 3.8 ±2.1 (mean ±SD) vs. ethyl chloride group 1.8 ±1.5 (mean ±SD) (P < 0.001). Intradermal lidocaine also significantly decreased the pain of PIV insertion, but with significantly decreased vein visibility and decreased ease of cannulation compared to the no treatment or ethyl chloride groups (P < 0.001) [18]. Comparatively, the pain of PIV cannulation for our placebo group was 4.3 ± 3.0 (mean ± SD) and median (IQR) 4 (2, 7) versus the vapocoolant group 2.3 ±2.4 (mean ±SD) and median (IQR) 2 (0,4) (Fig. 2).

5 Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although we did include a wide age range of adults, ages 18-80 years, we did not evaluate children or “older” geriatric patients (>80 years), we evaluated only one needlestick procedure and we used one formulation of vapocoolant spray. This was done to standardize our methodology, but may limit our generalizability, although other studies suggest that our findings may be generalizable to other patient populations, other needlestick procedures, and other vapocoolant sprays [16,32,33,34,35].

Our study is consistent with the study in a pediatric ED that also found significantly decreased PIV cannulation pain and a higher PIV success rate in children with the use of a vapocoolant spray compared to a placebo spray [16]. Other research documented significantly decreased pain for various other needlestick procedures including immunizations in both children [32] and in adults [15,33] and as a pre-injection anesthetic [34,35]. These studies [15,16,32,33,34,35] used the same formulation, 1,1,3,3-pentafluoropropane and 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane, of vapocoolant spray that we used in our clinical trial. Studies using other vapocoolant sprays e.g. ethyl chloride, or a propane/butane/pentane blend, have also found that these formulations decrease needlestick pain in adults [18,19,36,37,38].

In these studies and our study, the proper application of the vapocoolant spray as described in the methodology was followed. The importance of appropriate spray application: adequate spray time, proper height or distance from the site, etc. cannot be overlooked [28]. A few studies that found conflicting results failed to adhere to the recommended technique of application [28,39,40,41,42] and this has been cited as a possible reason for lack of efficacy of the vapocoolant spray in these studies [16,19,21,37].

Vapocoolant sprays last a short time, so the health care provider performing the needlestick procedure should have all the supplies readily available. This may be difficult in a busy ED. If the health care practitioner has to leave the patient and go and retrieve needed supplies, this allows the efficacy of the vapocoolant spray to wane. However, this should not be an issue, since the vapocoolant spray may be reapplied as often as needed.

The spray containers were identical (indistinguishable) and thus, blinded. The spray cans were masked and were stored together at the same (e.g. room temperature). Moreover, unmasking of the spray cans was not done until the study was over (e.g. enrollment ended and all data collection was completed). Although we sought to maintain blinding through obscuring aerosol containers, keeping the containers at the same temperature, and directing treatment sprays away from patients’ and health care providers faces to avoid visual cues and olfactory detection, we cannot prove effective blinding.

There may be a difference in sensation on the skin between the vapocoolant spray and the placebo spray, which may lead to a bias. Patients could only be enrolled once in the study to avoid previous experience with this specific vapocoolant spray and because patients never had prior experience with a vapocoolant spray (or placebo spray) as a topical anesthetic in the past, he/she would be “naíve” and would not know what a vapocoolant spray (or placebo spray) would feel like, so it is unlikely that the patient responses would be biased. Since we did not want to influence the patient’s response, we did not give them any pre-information about the sprays except that one was a placebo spray and one was the treatment spray.

We did collect details regarding the patients and the health care providers performing the procedures in order to document that the placebo and vapocoolant groups were similar at baseline and that the actual procedure of PIV cannulation was not significantly different between the two groups.

In summary, this prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial suggests that a topical vapocoolant spray (1,1,1,3,3-pentafluoropropane and 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane) is not only effective in significantly relieving the pain of PIV cannulation in adults in the ED, but was also well tolerated with a majority of patients indicating they would use the vapocoolant spray in the future.

This vapocoolant spray appears to be safe with only a few minor adverse effects that resolved quickly (within 5-10 min), and had no lasting visible skin abnormalities. This is consistent with an animal study that found no microcirculatory effects (e.g., no significant changes in vessel diameter and inflammatory markers) [24].

6 Implications

The use of topical skin refrigerants or vapocoolants has numerous advantages: rapid onset, easy application, inexpensive, avoids needlestick injury, eliminates intradermal injection pain, increases procedural success rates, and improves patient satisfaction. Given the frequency of needlestick procedures in the health care setting, not just in the emergency department but throughout the hospital: on the inpatient floors and the operating room, in clinics and offices, and outpatient surgery centers: topical refrigerant sprays have wide applicability and likely, increased usage in the future.

Highlights

Vapocoolant spray significantly decreased the pain of intravenous cannulation.

There were no complications or adverse events.

Minor side effects that occurred in a few patients resolved quickly.

No visible skin abnormalities were present 5–10 min after spray application.

-

Ethical issues: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

The study protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01670487).

-

Conflict of interest: Thus study was an investigator-initiated study supported by a research grant from the Gebauer Company. The sponsor had no involvement in the study other than funding and supplying the spray cans used for the administration of the placebo spray and the vapocoolant spray.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Mr. Benjamin Nutter, the Section of Biostatistics, Quantitative Health Sciences for his statistical analysis of the data.

References

[1] Zempsky WT. Pharmacologic approaches for reducing venous access pain in children. Pediatrics 2008;122:S140–53.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska AL, Thode Jr HC. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:652–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, Crandall CS, Fosnocht DE, Homel P, Tanabe P, PEMI Study Group. Pain in the emergency department: results of the Pain and Emergency Medicine Initiative (PEMI) multicenterstudy. J Pain 2007;8:460–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) Position Statement.Pediatric procedural pain management. Emergency Nurses Association; 2010 [last accessed March 2017].Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Kennedy RM, Luhmann J, Zempsky WT. Clinical implications of unmanaged needle-insertion pain and distress in children. Pediatrics 2008;122:S130–3.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Fosnocht DE, Swanson ER, Bossart P. Patient expectations for pain medication delivery. AmJ Emerg Med 2001;19:399–402.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Reyes-Gibby CC, Todd KH. Oligo-evidence for oligoanesthesia: a non sequitur? Ann Emerg Med 2013;612:373–4.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Todd KH, Sloan E, Chen C, Eder S, Wamstad K. Survey of Pain etiology, management practices and patient satisfaction in two urban emergency departments. CJEM 2002;4:252–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Fein JA, Zempsky WT, Cravero JP, Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine and Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics.Relief of pain and anxiety in pediatric patients in emergency medical systems. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1391–405.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Young KD. Pediatric procedural pain. Ann Emerg Med 2005;45:160–71.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] MacLean S, Obispo J, Young KD. The gap between pediatric emergency department procedural pain management treatments available and actual practice. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007;23:87–93.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] American Academy Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, American Pain Society Task Force on Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. The assessment and management of acute pain in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics 2001;108:793–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Zempsky WT. Optimizing the management of peripheral venous access pain in children: evidence, impact, and implementation. Pediatrics 2008;122:S121–4.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Czarnecki ML, Turner HN, Collins PM, Doellman D, Wrona S, Reynolds J. Procedural pain management: a clinical statement with practice implications. Pain Manag Nurs 2011;12:95–111.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Taddio A, Lord A, Hogan ME, Kikutu A, Yiu A, Darra E, Bruinse B, Keogh T, Stephens D. A randomized controlled trial of analgesia during vaccination in adults. Vaccine 2010;28:5365–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Farion KJ, Splinter KL, Newhook K, Gaboury I, Splinter WM. The effect of vapocoolant spray on pain due to intravenous cannulation in children: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2008;179:31–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Mace SE. Topical anesthesia. In: Mace SE, Ducharme J, Murphy MF, editors. Pain management and sedation, New York, NY. 2006. p. 195-202 [Chapter 26].Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Armstrong P, Young C, McKeown D. Ethyl chloride and venipuncture pain: a comparison with intradermal lidocaine. Can J Anaesth 1990;37:656–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Page DF, Taylor DM. Vapocoolant spray vs. subcutaneous lidocaine injection for reducing the pain of intravenous cannulation: a randomized, controlled, clinical trial.BrJ Anaesth 2010;105:519–25.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Parent du Chatelet I, Lang J, Schlumberger M, Vidor E, Soula G, Genet A, Standaert SM, Saliou P. Clinical immunogenicity and tolerance studies of liquid vaccines delivered byjet-injectorand a new single-use cartridge (Imule): comparison with standard syringe injection. Vaccine 1997;15:449–58.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Mace SE. Prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray vs.placebo spray in adults. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:798–804.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Kelly AM. Does the clinically significant difference in visual analog scale pain scores vary with gender, age, or cause of pain? Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:1086–90.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Todd KH, Funk JP. The minimum clinically important difference in physicianassigned visual analog pain scores. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:142–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Galdyn I, Swanson E, Gordon C, Kwiecien G, Bena J, Siemionow M, Zins J. Microcirculatory effect of topical vapocoolants. Plast Surg 2015;23:71–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Evans JG, Taylor DM, Hurren F, Ward P, Yeoh M, Hoiwden BP. Effects of vapocoolant spray on skin sterility prior to intravenous cannulation. J Hosp Infect 2015;90:333–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Schleicher WF, Richards BG, Huetther F, Ozturk C, Zuccaro P, Zins JE. Skin sterility after application of a vapocoolant spray. Dermatol Surg 2014;40:1103–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Burke D, Mogyoros I, Vagg R, Kierman MC. Temperature dependence of excitability indices of human cutaneous afferents. Muscle Nerve 1999;22:51–60.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Griffith RJ, Jordan V, Herd D, Reed PW, Dalziel SR. Vapocoolants (cold spray) for pain treatment during intravenous cannulation (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016. ANCD009484.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Algafly AA, George KP. The effect of cryotherapy on nerve conduction velocity, pain threshold and pain tolerance. BrJ Sports Med 2007;41:365–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Malanga GA, Yan N, Stark J. Mechanisms and efficacy of heat and cold therapies for musculoskeletal injuries. Postgrad Med 2015;127:57–65.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Fossum K, Love SL, April MD. Topical ethyl chloride to reduce pain associated with venous catheterization: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:845–50.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Reis Cohen E, Holubkov R. Vapocoolant spray is equally effective as EMLA cream in reducing immunization pain in school-aged children. Pediatrics 1997;100 http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/100/6/e5.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Mawhorter S, Daugherty L, Ford A, Hughes R, Metzger D, Easley K. Topical vapocoolant quickly and effectively reduces vaccine-associated pain: results ofa randomized, single-blinded, placebo controlled study. J Travel Med 2004;11:267–72.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Weiss RA, Lavin PT. Reduction of pain and anxiety prior to botulinum toxin injections with a new topical anesthestic method. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;25:173–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Kosaraju A, Vanewallie KS. A comparison of a refrigerant and a topical anesthetic gel as preinjection anesthetics: a clinical evaluation. JSADA 2009;140:68–72.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Selby IR, Bowles BJ. Analgesia for venous cannulation: a comparison of EMLA (5 minute application), lignocaine, ethyl chloride and nothing. J R Soc Med 1995;88:264–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Hijazi R, Taylor D. Effect of topical alkane vapocoolant spray on pain with intravenous cannulation n patients in emergency departments: randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:b215, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b215.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Celik G, Ozbek O, Yilmaz M, Dunman I, Ozbek S, Apiliogullaris S. Vapocoolant spray vs lidocaine/prilocaine cream for reducing the pain of venipuncture in hemodialysis patients: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. Int J Med Sci 2011;8:623–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Ramsook C, Kozinetz CA, Moro-Sutherland D. Efficacy of ethyl vinyl chloride as a local anesthetic for venipuncture and catheter insertion in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2001;17:341–3.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Costello M, Ramundo M, Christopher N, Powell KR. Ethyl chloride vapocoolant spray fails to decrease pain associate with intravenous cannulation in children. Clin Pediatr(Phila) 2006;45:628–32.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Biro P, Meier T, Cummins AS. Comparison of topical anesthesia methods for venous cannulation in adults. EurJ Pain 1997;1:37–42.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Hogan ME, Smart S, Shah V, Taddio A. A systematic review of vapocoolants for reducing pain from venipuncture and venous cannulation in children and adults. J Emerg Med 2014;47:736–49.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2017 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia