Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

-

Deepika S. Darbari

Abstract

Pain is the hallmark of sickle cell anemia (SCA), presenting as recurrent acute events or chronic pain. Central sensitization, or enhanced excitability of the central nervous system, alters pain processing and contributes to the maintenance of chronic pain. Individuals with SCA demonstrate enhanced sensitivity to painful stimuli however central mechanisms of pain have not been fully explored. We hypothesized that adults with SCA would show evidence of central sensitization as observed in other diseases of chronic pain.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study of static and dynamic quantitative sensory tests in 30 adults with SCA and 30 matched controls.

Results

Static thermal testing using cold stimuli showed lower pain thresholds (p = 0.04) and tolerance (p = 0.04) in sickle cell subjects, but not for heat. However, SCA subjects reported higher pain ratings with random heat pulses (p < 0.0001) and change in scores with temporal summation at the heat pain threshold (p = 0.002). Similarly, with the use of pressure pain stimuli, sickle cell subjects reported higher pain ratings (p = 0.04), but not higher pressure pain tolerance/thresholds or allodynia to light tactile stimuli. Temporal summation pain score changes using 2 pinprick probes (256 and 512 mN) were significantly greater (p = 0.004 and p = 0.008) with sickle cell, and delayed recovery was associated with lower fetal hemoglobin (p = 0.002 and 0.003).

Conclusions

Exaggerated temporal summation responses provide evidence of central sensitization in SCA.

Implications

The association with fetal hemoglobin suggests this known SCA modifier may have a therapeutic role in modulating central sensitization.

1 Introduction

Pain is the most common manifestation of sickle cell disease (SCD). The onset of acute painful vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) coincide with a post-natal fetal hemoglobin decline, and frequency is impacted by age, sex, fetal hemoglobin and homozygous SCD [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Diary studies demonstrate children with SCD experience pain, however, frequency and opioid use increase in adolescence [2,6]. In an adult pain diary study (PiSCES), 55% of subjects reported pain on more than half of days and 29% had daily pain, where more frequent pain correlated with hospital utilization [3,8]. In older patients, acute SCD pain is often superimposed on chronic pain [9].

Occlusion of sickled erythrocytes during hypoxia within the microcirculation is believed to be the proximate cause of acute VOCs. However, it is not known if factors other than hypoxia influence chronic SCD pain [4]. Recurrent VOCs, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, genetic polymorphisms and central sensitization likely contribute to variation in SCD pain [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Murine SCD models and individuals with SCD show increased sensitivity to experimental pain similar to that described in other groups with chronic pain [12,16,17,18]. Recent murine and human studies have observed central sensitization in SCD [10,14,18,19,20,21,22]. Central sensitization is a process where repeated nociceptive signals from the periphery affect and alter pain processing in the central nervous system, leading to amplification of pain. Manifestations include hyperalgesia and allodynia, an increased area of hyperalgesia extending beyond the initial area of injury, and aftersensations following resolution of initial injury [23]. Many of these features are often observed by clinicians who treat SCD.

Quantitative sensory testing (QST) measures responses to experimental stimuli and the function of neural pain processing pathways [24]. Static end points include pain thresholds, pain tolerance, and pain ratings (e.g., 0-10) in response to a noxious stimulus. Temporal summation assesses excitatory elements of central nervous system pain processing [25].

QST has been used to characterize many chronically painful conditions, but its use in SCD has only recently developed. QST in SCD shows increased sensitivity to painful stimuli [12,18,19,20,21,26,27,28,29,30] which is heightened by age [18,27,30,31]. While SCD studies have demonstrated increased sensitivity by static QST methods, the magnitude of these differences were significantly smaller than in fibromyalgia [14,18,27,28,32]. Recent QST studies exploring central sensitization in SCD are promising [14], however its relationship with known disease modifiers has not been evaluated [4,13,14,19,20]. Indeed, recent resting state functional MRI showed a significant correlation between anti-nociceptive brain connectivity and fetal hemoglobin in low pain burden SCD patients [15].

In this study, we compared static and dynamic QST responses between adults with SCA and matched normal volunteers. We hypothesized that adults with homozygous SCD would show greater evidence of central sensitization owing to the high prevalence of chronic pain in older patients. We observed that central sensitization is a feature of sickle cell pain, and surprisingly that temporal summation was lessened in the setting of higher fetal hemoglobin, a determinant of disease severity [4].

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study population

Sickle cell anemia (homozygous SS or Sβ°) subjects who consented to the Bethesda Sickle Cell Cohort Study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00011648) during 2011 were approached sequentially for participation in a new protocol focused on pain. Other SS subjects expressing interest in the study were also enrolled, yielding a random cross sectional sample. Inclusion criteria were (1) sickle cell anemia (SCA), (2) African ancestry, and (3) residence within 50 miles of the National Institutes of Health so that participants could return for the pain testing as needed. Subjects were age and sex matched to healthy normal volunteers (NVs) identified by the NIH Clinical Center Recruitment Office (www.cc.nih.gov/recruit/volunteers.html). Inclusion criteria for NVs were (1) African ancestry and (2) absence of any disease associated with pain (e.g. fibromyalgia, chronic back pain, diabetes, etc.). NVs were excluded for any hemoglobinopathy including sickle trait or acute or chronic pain at initial evaluation. Subjects provided written informed consent to an IRB approved protocol (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01441141) and underwent further screening which included a medical history, physical exam (including a neurologic exam) and lab studies prior to being scheduled for QST. Recruitment and initial testing took place between November 2012 and August 2014 (Supplemental Fig. S1).

2.2 Quantitative sensory testing

QST was performed in steady state without acute painful events requiring physician treatment in the two weeks prior to testing. QST as described below was performed by 2 team members (CS and KV) to minimize investigator dependent variability. All verbal instructions to subjects were scripted. Testing for thermal thresholds, thermal temporal summation, algometry, and mechanical pinprick temporal summation were based upon a previously published QST protocol [33].Thirteen out of 30 sickle cell subjects were on maintenance daily opioids which were not stopped for the study as it was determined to be ethically and medically inappropriate to withhold analgesics. Daily opioids were prescribed by their primary hematologists for management of typical daily SCD pain without an acute painful event (i.e. pain not requiring medical attention). Pain scores obtained during QST used the 20 point Gracely Pain Scale (GPS); with one score for pain and another for unpleasantness [34]. The Gracely Pain Scale was designed to measure the intensity and unpleasantness of the individual’s pain sensation with the aid of verbal pain descriptors. The multiple verbal descriptors cover the entire pain range, minimizing floor and ceiling effects [35].

Scoring required that each subject reviewed the 13 verbal descriptors along a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 20. The location along with the VAS for a descriptor was used as the numerical score for that descriptor. The subject’s score was determined by the descriptor selected as best representing their perceived pain or unpleasantness. The VAS creates a ratio scale for the descriptors, where the minimum VAS score is 0. The psychometric properties of the scales, assessed using ratio-scaling techniques, indicate that scores assigned to the descriptors demonstrate good internal consistency, reliability and objectivity [36]. Records of all hospitalizations during the 12 months prior to study were reviewed to confirm patient reported outcomes.

Thermal QST defined static temperature responses and dynamic thermal testing included random order heat pulses and temporal summation [25]. Thermal stimulus experiments used a Medoc Sensory Analyzer (model TSA 2001-II; Medoc Ltd., Israel) with a 2.56 cm2 contact thermode. Static tests were administered at four sites on each forearm (nonhairy volar surface between the elbow and wrist of the distal forearm; approximately 4 cm between sites). At each forearm testing site, subjects indicated the thermal detection threshold (thermal stimuli first felt), the pain threshold (pain first felt from thermal stimuli), and pain tolerance (point at which unable to continue testing due to pain caused by heat and cold stimuli).

The dynamic thermal test was performed on the dominant volar forearm, slightly lateral to where static thermal tests were administered to avoid overlapping stimulation sites. The test first consisted of random order heat pulses and then individualized temperature heat pulses for temporal summation. The random thermal series included 14 pulses administered in random order between 32 and 44°C (in 2°C increments; each temperature tested twice). Individualized pulses included a series of 10 heat pulses with 5 s intervals between each pulse (the shortest interval allowed by the TSA 2001-II [33]). Four 10 pulse sequences were tested: one at the subject’s pain threshold, one 2 °C below the threshold, one 2 °C above the threshold, and then one at 45 °C. Pain scores were recorded between each pulse for each series of 10 pulses. Additional pain ratings were obtained 15 s after cessation of the stimulus to characterize aftersensations. Thermal temporal summation was defined by a Δ pain score = highest pain rating minus the first score [37].

Conditioned pain modulation (CPM) used the Medoc (thermode applied to nonhairy volar forearm) and either a room temperature water bath or a hot water bath (immersion of non-dominant hand) [25]. The hot water bath was a modification from use of ice water which is not a feasible inhibitory painful stimulus in sickle cell anemia. The thermode temperature was where subjects reported a pain magnitude rating score as close to 11 (verbal descriptor “moderate”) as possible. The thermode at this pain magnitude rating was the primary painful stimulus. The neutral water bath served as a habituation test. The hot water bath temperature was where subjects reported pain ratings of 12-14 (pain magnitude rating) after hand immersion (20 s). During CPM testing, the volar forearm thermode increased to the temperature for the pre-defined pain magnitude rating of 11 and returned to baseline. Subjects reported pain ratings every 8 s during heating and twice during recovery.

Pressure pain testing used 2 instruments (1) a hand-held algometer (FDN200, Wagner Instruments, Greenwich, CT) and (2) a custom hydraulic pressure device (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) on the dominant thumbnail [38]. Algometer pressure increased at 0.5 kg/s administered with a 0.785 cm2 algometer probe until the subject reached tolerance. Algometer pressure (kg) was recorded at pain threshold and tolerance. Handheld algometry pain threshold and tolerance were also performed at additional sites including at the dominant hand proximal forearm muscle extensors (probe applied between the olecranon process and the medial epicondoyle) and the trapezius muscle (5 cm lateral to each side of the spinous process of C8). Tests at each site were performed twice. The hydraulic pressure device measured pain tolerance using a blunt pressure stimulus delivered to the nail bed by a 1 cm2 hard-rubber probe, where the thumb of the dominant hand was inserted into a plastic housing connected to a hydraulic piston. Pressure was delivered by weights (kg) placed above the piston. The sequence and intensity of pressure delivery followed guidelines developed at University of Michigan.

Mechanical sensitivity was measured using electronic von Frey filaments (Model 2390 Series, IITC Life Science, Inc., Woodland Hills, CA) and weighted mechanical pinprick probes (Stoelting Inc., Wood Dale, IL) [33,37]. Von Frey filaments measured static tactile sensation detection thresholds (light touch). Filaments with uniform

0. 8 mm diameter probes were applied to the nonhairy portion of the upper volar forearm with sequentially increased filament size until the touch sensation was detected. This was then repeated in reverse, moving from larger to smaller filaments until touch was no longer detected. Filaments ranged from 0.1 to 70 g.

Mechanical pinprick pain scores were measured with 256 and 512 mN probes on the dorsum of the dominant hand index and middle digits between the first and second interphalangeal joints, respectively. During testing, the probe was pressed onto the finger once followed by Δ pain score and a 1 min break. Next, ten pinpricks were applied at the same site with 1 s between each stimulus. Pain ratings were taken immediately after the first stimulus, after the 10 stimuli sequence and after completion of testing (at 15 and 30 s). This sequence was repeated three times with a 1 min break between testing.

2.3 Statistical analysis

At the time of study design no effect size data for pain were available for power calculations for sickle cell anemia patients, so the chronic pain model of osteoarthritis was selected. The study was prospectively designed to recruit 30 subjects and 30 NVs (assuming 10% dropout) to yield 93% statistical power to detect the effect sizes observed for pressure pain threshold [39]. Analysis software included Instat (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA), Prism (Graph Pad Software), Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), and SVS (Golden Helix, Bozeman, MT). Continuous data for QST with multiple replicates were averaged for each subject, and means (with standard deviations) were then used for group comparisons. Comparisons of sickle cell and NV groups were made by Chi-square (categorical variables) or t-tests (alternatively, Welch’s t-test where these groups had unequal variances or Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data). ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) was used for analysis of the random order thermal temporal summation QST (Fig. 1C). Mechanical temporal summation was assessed using the change in pain score (Δ pain score) from the first to last stimulus, while the thermal Δ pain score was calculated as the difference between the first score and the highest score from the train of 10 pulses [37]. Spearman correlation was used to determine if 2 variables were associated in univariate analysis. Multivariable stepwise linear regressions using both backward and forward selection methods were used to determine if any of six variables that distinguished sickle cell anemia subjects from normal volunteers (Table 1; including sickle cell anemia status, hemoglobin, fetal hemoglobin, number of hospitalizations for pain treatment during the 12 months prior to enrollment, hydroxyurea dose (mg/kg/day) and opioid dose during the 24 h prior to testing (morphine equivalents, mg)) were associated with specific pain tests in a final regression model. Regression models limited to subjects with sickle cell only included significant variables from models that analyzed all subjects (n = 60). Final regressions were adjusted for gender and age, as these variables are known to modify pain and fetal hemoglobin [1,4]. P-values are uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

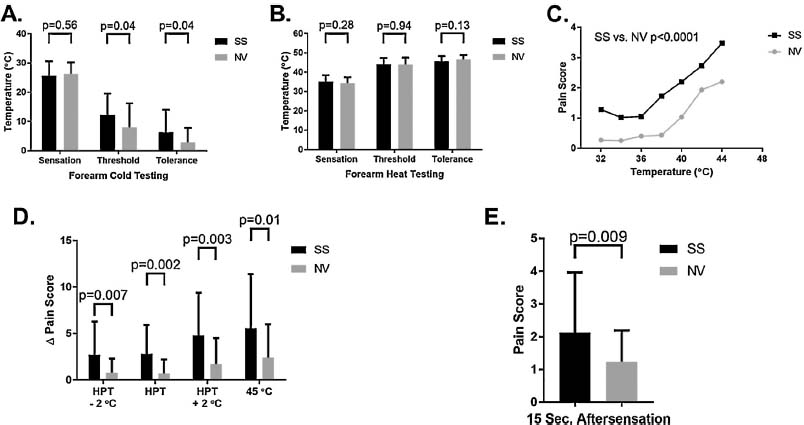

Static thermal pain threshold/tolerance testing and dynamic thermal temporal summation testing. (A) Cold testing was performed at sites of the volar forearm. Means with standard deviations are illustrated. (B) Heat testing was also performed on the forearm. Thermal detection threshold (sensation in the figure), pain threshold and pain tolerance means with standard deviation are illustrated. (C) Pain scores (0-20 scale) after each of 14 random order thermal pulses between 32 and 44 °C. Sickle cell status (p< 0.0001) and temperature (p< 0.0001) were associated with pain scores (ANCOVA). (D) Temporal summation thermal testing at individualized heat pain thresholds shows enhanced A pain scores in sickle cell anemia. Δ pain scores are reported as means with standard deviations. (E) Aftersensations suggested by pain scores 15s after thermal sequence pulses in panel D.

Population demographics of adults with sickle cell anemia and matched normal volunteers.

| Parameter | SS (n=30) Mean (SD) | Normal volunteer (n = 30) Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.3 (10.0) | 33.7 (10.0) | 0.81 |

| Male (n) | 15 (50%)[a] | 15 (50%) | 1.00[b] |

| WBC (K/μL) | 8.43 (2.72) | 5.34 (1.41) | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.1 (1.2) | 12.9 (1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Hb F (%) | 10.9 (7.9) | 0.0 (0.0) | - |

| Hb S (%) | 70.8 (21.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | - |

| Hb A (%) | 14.5 (24.9) | 97.1 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| Platelets (K/μL) | 328.2 (116.6) | 236.4 (50.9) | 0.0003 |

| Reticulocytes (%) | 12.1 (5.3) | 1.3 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| LDH (U/L) | 495.1 (205.6)[c] | 174.2 (37.8)[c] | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.58 (1.76) | 0.93 (0.17) | <0.0001 |

| Hospitalizations for pain[d] | 2.14 (1.77) | 0.0 (0.0) | - |

| Hydroxyurea (n) | 18 (60%)[a] | 0 (0%) | - |

| Hydroxyurea (mg/kg/day) | 18.6 (9.4)[e] | 0.0 (0.0) | - |

| Opioid dose prior to testing (morphine equivalents, mg) | 46.9 (88.8)[f] | 0.0 (0.0) | - |

| Pain score at evaluation[g] | 1.88 (2.58) | 0.07 (0.37) | 0.0006 |

3 Results

3.1 Subject demographics

Demographics for 30 SS subjects and 30 age and sex matched NVs are presented in Table 1. Mean age was 34.3 versus 33.7 years in sickle cell anemia and NVs, respectively. Sickle cell anemia subjects had a mean of 2.14 (range 0-5) hospitalizations for pain during the 12 months prior to enrollment and 60% reported hydroxyurea treatment. Thirteen subjects (43%) were on daily oral opioids at a mean dose of 46.9 mg morphine equivalents for treatment of routine daily sickle cell pain without an acute, severe painful event. Four out of the 13 subjects were on maintenance sustained release opioids. On the day of evaluation, sickle cell subjects had higher overall baseline self-reported pain scores (1.88 ± 2.58) compared to normal volunteers (0.07 ±0.37) using a 0-10 clinical scale despite the absence of acute crisis pain suggesting a high daily pain burden in adults with sickle cell anemia.

3.2 Thermal quantitative sensory testing including temporal summation

Pain threshold (12.2°C versus 8.0°C in NVs, p = 0.04) and pain tolerance (6.3 °C versus 2.8 °C in NVs, p = 0.04) temperatures using cold stimuli were significantly different in sickle cell anemia although there were no difference in cold detection (when the cold stimulus was first felt) (Fig. 1A). No differences were noted for threshold or tolerance to heat (Fig. 1B). Thresholds were not associated with age as observed in a prior pediatric study likely because all subjects in this study were adults (Spearman correlation, data not shown) [18].

Fourteen random thermal pulses between 32 and 44 °C elicited higher pain scores in sickle cell subjects (p< 0.0001) (Fig. 1C). In preparation for temporal summation testing at the heat pain threshold, we again determined heat pain thresholds. As in Fig. 1B, there was again no difference in heat pain thresholds between SS participants and NVs (44.1 °C versus 44.0 °C, respectively; p = 0.94). However, temporal summation Δ pain scores after a pulse of ten stimuli) at or near the pain threshold were significantly higher in the sickle cell group (p = 0.002) (Fig. 1D) as well as significantly higher aftersensation pain scores 15 s after stimulation had concluded (Fig. 1E).

CPM testing with thermal stimuli screened for differences in the prevalence of chronic pain (Supplemental Fig. S2). Pre-determined pain magnitude ratings defined by Δ pain score of a least 11 was achieved at a significantly lower temperature in the sickle cell group (mean 46.2 ± 2.3 °C) than in NVs (47.5 ±2.1 °C, p = 0.02) with the thermode on the volar forearm. The second noxious stimulus was hand immersion into a hot water bath. Again, sickle cell subjects reached this pre-determined pain magnitude rating at a lower temperature (46.1 ±1.6 °C in n = 29 versus 46.8 ±1.3 °C in n = 28 NVs; p = 0.05). However, there was no difference in pain scores between groups when using the Medoc pain magnitude rating temperature alone (p = 0.83) or in combination with either a neutral control (hand immersion in room temperature water bath; p = 0.88) or an inhibitory control (hand in hot water bath; p = 0.77) (Supplemental Fig. S1).

3.3 Static mechanical pressure pain

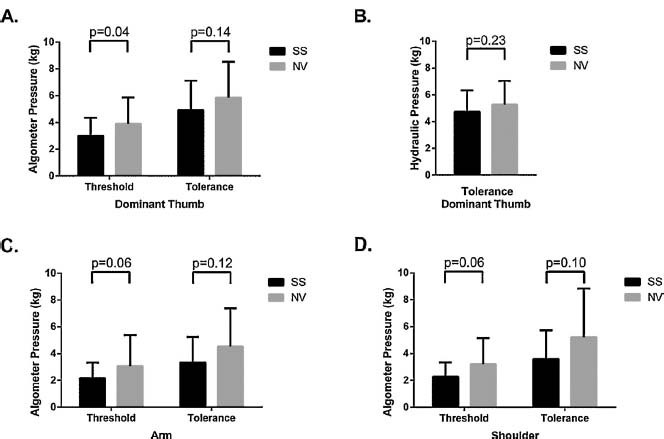

The algometer pressure pain threshold at the dominant thumb was significantly lower in sickle cell anemia (Fig. 2A; p = 0.04), while pain tolerance was not (Fig. 2A). Tolerance with the operator independent hydraulic pressure device was identical to algometer tolerance, indicating the reproducibility of this mode of testing (Fig. 2B). Pressure threshold testing on the forearm (p = 0.06) and shoulder (p = 0.06) approached statistical significance but tolerance was not different (Fig. 2C and D).

Static pressure pain testing. Pressure pain testing was conducted with the use of a handheld algometer (A) or a hydraulic pressure devise (B) on the dominant hand thumbnail. The pain threshold was where subjects first reported pain and the tolerance was the subject’s maximum tolerated pain. Results for pain tolerance were nearly identical for both the algometer and the hydraulic pressure testing system. Pressure testing for threshold and tolerance was also performed on the arm (C) and shoulder (D). SS patients reported higher pain scores than normal volunteers. All illustrations are for means with standard deviations.

3.4 Mechanical light touch, pin prick temporal summation, and fetal hemoglobin

Light touch testing (von Frey) did not show differences between groups (Supplemental Table S1). Mechanical pinprick testing using different weighted probes (256 and 512 mN) showed both sickle cell and NV subjects experienced temporal summation comparing pain scores for a single stimulus to the change in scores for a train of 10 pinpricks (Δ pain score) (Table 2). Single stimuli with the pinprick probes showed no significant difference in pain between sickle cell and NVs (p = 0.38 and p = 0.92, respectively). Furthermore, sickle cell subjects experienced significantly higher Δ pain scores after summation and aftersensation pain scores (Table 2). Using stepwise linear regression, Δ pain scores (temporal summation) were independently associated with sickle cell anemia as expected and inversely associated with HbF (Table 3). These regression models had adjusted r2 = 0.25 and 0.21, respectively. To determine if HbF played any role in pain sensitivity, we assessed this association limited only to the sickle cell cohort which showed fetal hemoglobin was negatively associated with pain (β = –0.338, p = 0.006 for 512 mN; β = –0.368, p = 0.005 for 256 mN). Because another report suggested that nociceptive processing in SCD is affected by opioid therapy [40], regressions restricted to sickle cell subjects not treated with opioids (n = 17) showed comparable results for association with HbF (256 Δ pain score β = –0.322, standard error = 0.171 with p = 0.08 and 512 Δ pain score for β = -0.365, standard error = 0.178 with p = 0.06), and suggest this association is independent of opioids.

Pinprick mechanical pain is enhanced in sickle cell anemia

| Pinprick probe | SS (n = 30) Mean pain score[a] (SD) | Normal volunteer (n = 30)Mean pain score (SD) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 256 mN probe | |||

| Single stimulus | 1.65 (1.98) | 2.06 (2.21) | 0.38 |

| Ten stimuli | 8.56 (5.40) | 5.83 (4.31) | 0.05 |

| 15 s post testing | 4.62 (5.03) | 1.20 (2.17) | 0.0002 |

| 30 s post testing | 3.68 (4.50) | 0.61 (1.42) | <0.0001 |

| Temporal summation (Δ pain score) | 6.91 (5.02)[b] | 3.77 (3.26)[c] | 0.004 |

| 512 mN probe | |||

| Single stimulus | 3.52 (2.55)[c] | 3.93 (3.72) | 0.92 |

| Ten stimuli | 11.73 (5.57)[c] | 9.36 (5.38) | 0.10 |

| 15 s post testing | 8.00 (6.41) | 3.67 (4.96) | 0.005 |

| 30 s post testing | 5.83 (6.40) | 2.70 (4.36) | 0.03 |

| Temporal summation (Δ pain score) | 8.53 (5.03)[c],[d] | 5.43 (3.41)[e] | 0.008 |

Low fetal hemoglobin is associated with mechanical temporal summation in adults with sickle cell anemia

| Independent variables[a] | β (standard error) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| 256 nM probe TS (Δ pain score) | ||

| Sickle cell status | 6.392 (1.427) | <0.0001 |

| HbF (%)[b] | –0.300 (0.904) | 0.002 |

| 512 nM probe TS (Δ pain score) | ||

| Sickle cell status | 6.673 (1.536) | <0.0001 |

| HbF (%)[c] | –0.318 (0.101) | 0.003 |

4 Discussion

In this study comparing adults with homozygous SCD (Hb SS or sickle cell anemia) to age and sex matched controls we show increased heat and cold pain sensitivity and pressure hyperalgesia compared to normal volunteers as previously reported [18,20,27,28]. We extended these observations by utilizing dynamic assessments of pain sensitivity, where we observed higher changes in pain scores and delayed recovery in response to thermal and mechanical temporal summation in sickle cell anemia. Slow recovery with prolonged aftersensations suggests excitatory changes within the central nervous system consistent with central sensitization [41]. More importantly, mechanical temporal summation was inversely associated with fetal hemoglobin, a known modifier of SCA pain and disease severity, but not with hospitalizations for acute pain or other hematologic variables (i.e. reticulocytes or total bilirubin) from these sickle cell subjects. This association suggests some elements of sickle cell pathophysiology may also impact the development of central sensitization in SCA.

The key finding in this study is that adults with SCA have enhanced mechanical temporal summation responses, which are associated with fetal hemoglobin levels independent of the effects of opioids in sickle cell. Tests of temporal summation are being considered as potential clinical assessment tools for characterizing central sensitization in other chronic pain conditions [41,42], although central sensitization is not uniformly observed in chronic pain [14,43]. Temporal summation is specific for increased responses by spinal dorsal horn or other central neurons to painful stimuli [41,44,45]. Ezenwa et al. showed that sixty percent of SCD adults had centralized pain using an algorithm assessing allodynia and hyperalgesia [20], while another SCD study showed a prevalence of 25% [14]. These results suggest that central sensitization may be a common element of pain in SCD. Direct findings documenting central sensitization are seen in nociceptive dorsal horn neurons in SCD mice [19]. Indirect findings in mice, in particular, partial reversal of mechanical pain with a local anesthetic (i.e. a peripheral channel antagonist) also suggest contribution from nonperipheral factors [12,21].

The association between mechanical temporal summation (Δ pain scores) and fetal hemoglobin (HbF) (Table 3) was not unexpected because HbF modulates both SCA pain and crisis frequency [4]. This finding is also consistent with the recent report of an association between antinociceptive brain connectivity, higher fetal hemoglobin and low pain crisis hospitalization burden in children with SCD [15]. If causative, fetal hemoglobin induction with hydroxyurea could also help reduce the prevalence of chronic pain attributable to central sensitization. Alternatively, it is possible that this association could be due to a high rate of hydroxyurea treatment in this cohort and not a direct effect of fetal hemoglobin. Otherwise, peripheral nociceptor inhibition or central neuroactive agents are experimental treatments for pain states characterized by central sensitization [41,46]. Interestingly, in our experiment the HbF effect was not observed with heat temporal summation. Pinprick is detected by myelinated AS peripheral nociceptors, while heat utilizes unmyelinated C fibers [24]. Faster AS fiber transmission to the spinal cord leads to more rapid excitatory input. In addition, the fixed 5 s heat pulse spacing interval may have contributed to the absence of disease severity associations, as summation pain is enhanced by shorter intervals [33,41]. Together, these factors could explain the inability to detect covariable effects. Nonetheless, the link between fetal hemoglobin and SCA central hyperalgesia needs to be confirmed in larger studies.

We did not observe differences for static heat pain thresholds or tactile allodynia in SCA. These results are in contrast with the heat pain hyperalgesia and light touch allodynia reported in SCD mice and heat pain hyperalgesia in children with SCD [12,18,21,30,31]. However, our results are similar to another QST study of adults with SCD, which likewise did not show increased heat pain thresholds [13]. We speculate that these inconsistent findings might be explained by different physiologic effects in children versus adults [13,18]. Our sites for heat pain testing were also different than those used in the pediatric study (forearm versus hand) and may reflect site specific sensitivity [18]. Furthermore, CPM failed to demonstrate heat pain inhibition in NVs, indicating that hot water hand immersion in place of ice water failed to produce a valid test [47]. The change was made because cold has the potential to induce an SCD painful crisis [1]. African Americans also experience greater pain sensitivity and reduced CPM than Europeans, suggesting that our small pilot study might have been underpowered [48]. Our CPM protocol will require further modification to produce a valid test [20]. Perhaps testing different sensory afferents together (e.g. heat/cold or heat/mechanical) will produce the expected inhibition as was observed in 2 other studies of adults with SCD [13,14]. Determining CPM responses is critical for further understanding descending modulation of pain transmission within the central nervous system in SCD [13,14,25,41].

Finally, our subjects were limited to homozygotes (SS or SCA), as other genotypes have differences in clinical manifestations, in particular, the frequency of painful events [4]. Previous SCD studies have not controlled for genotype effects on experimental or clinical pain [13,14,18,20,27,28]. Furthermore, we were likely only able to detect the HbF association because its expression is significantly higher in SCA compared to hemoglobin SC [34,36], another common genotype present in prior QST studies [13,14,18,20,27,28,49,50]. The association was similarly not detected in studies of the S-Berk mouse, which does not express HbF [19]. In addition, QST responses and the pain hospitalization rate were not correlated, consistent with prior observations [18]. Pain hospitalization rate is important because it is associated with mortality, although it underestimates daily pain [3,4]. Several recent studies of adults with SCD assessed pain using diaries, but did not quantify this specific measure of healthcare utilization due to pain [13,14]. Despite the lack of association with this measure of SCD severity, QST may still be a useful for clinical trials [4,51]. Pain diaries will also be necessary to further assess the relationship between pain and QST responses as has been documented elsewhere [14].

This study has several limitations. Age, sex, opioids and genotype modulate SCD pain [1,4]. We controlled for age and sex with matching, and controlled for genotype by only studying subjects homozygous for the sickle hemoglobin mutation. In addition, less than 50% of subjects reported taking opioids prior to QST. Opioid use in adults with SCD is complex because treatment could produce analgesia, tolerance or hyperalgesia [52]. Although neither the regression with all subjects, nor regression excluding those taking opioids led to different conclusions, it is not possible to preclude opioid induced responses, especially in patients experiencing high pain burden that necessitates daily therapy. Indeed, a study of 38 SCD patients with high or low central sensitization showed high group responses were associated with opioid therapy [40]. Therefore, larger studies designed to determine the effect of opioids in sickle cell are needed [53]. In addition, our power estimates were based on pressure pain thresholds in osteoarthritis due to the lack of published data in SCD during study design [54]. However, there is a need to better characterize effect sizes, variability due to different forms of SCD and statistical significance of pain measures in SCD in larger studies [53]. Finally, QST alone is unable to determine whether sickle cell hyperalgesia is of neuropathic or inflammatory origin [51].

5 Conclusions

We present temporal summation evidence for central sensitization as one mechanism underlying enhanced sickle cell sensitivity to pain [13,14,19,20], and identify an association between increased temporal summation pain and fetal hemoglobin levels.

6 Implications

The fetal hemoglobin association has not been previously been reported and it supports broad use of hydroxyurea. Therapeutic agents that modify pain transmission within the central nervous system should also be investigated as an alternative to opioid therapy.

Highlights

Adults with sickle cell anemia show evidence of central sensitization.

Central sensitization correlated with fetal hemoglobin levels.

Central sensitization could be modulated by fetal hemoglobin induction.

Abbreviations

- SCD

-

sickle cell disease

- SCA

-

sickle cell anemia

- VOC

-

vaso-occlusive crisis.

-

Ethical issues: Written informed consent was required of all enrolled subjects after protocol approval by the Institutional Review Board at the National Institutes of Health. The study was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT01441141).

-

Conflict of interest:The authors report no conflicts of interest.

-

Author contributions:Conceived and designed study: DSD, CS, GRW, IB, JGT. QST and research coordination: KV, CS, KC, AC. Statistical analysis: KV, MQ, MAW, JGT. Data interpretation: DSD, KV, CS, KC, MQ, AC, LD, ANS, JAH, MAW, GRW, IB, JGT. Logistical support and QST training: AC, LD, GRW, ANS, JAH, IB. Drafted manuscript: JGT with contributions from DSD and KV. All authors contributed to manuscript writing and editing.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Steve Harte of the Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center in the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Michigan for providing the hydraulic pressure device for use in this study. We also thank Stephanie Housel for expert protocol management. Finally, we thank the intramural program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) for the generous donation of space and nursing support in the Clinical Center Metabolic Unit to complete this study. This work was supported by the NHLBI Intramural Research program, National Institutes of Health (1 ZIAHL006160 05), an NHLBI, National Institutes of Health Award (P50HL118006) and Howard University College of Medicine. DSD was partially supported by a contract from the National Institutes of Health (1 ZIA HL006160 05).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.08.001.

References

[1] Ballas SK, Bauserman RL, McCarthy WF, Castro OL, Smith WR, Waclawiwa MA. Investigators of the multicenter study of hydroxyurea in sickle cell, utilization of analgesics in the multicenter study of hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia: effect ofsex, age, and geographical location. Am J Hematol 2010;85:613–6.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, O’Neal P. Characteristics of pain managed at home in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease by using diary self-reports. J Pain 2002;3:461–70.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, McClish DK, Roberts JD, Dahman B, Aisiku IP, Levenson JL, Roseff SD. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:94–101.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Platt OS, Thorington BD, Brambilla DJ, Milner PF, Rosse WF, Vichinsky E, Kinney TR. Pain in sickle cell disease.Rates and risk factors. N Engl J Med 1991;325:11-6.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Darbari DS, Onyekwere O, Nouraie M, Minniti CP, Luchtman-Jones L, Rana S, Sable C, Ensing G, Dham N, Campbell A, Arteta M, Gladwin MT, Castro O, Taylor JGT, Kato GJ, Gordeuk V. Markers of severe vaso-occlusive painful episode frequency in children and adolescents with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr 2012;160:286–90.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Shapiro BS, Dinges DF, Orne EC, Bauer N, Reilly LB, Whitehouse WG, Ohene-Frempong K, Orne MT. Home management of sickle cell-related pain in children and adolescents: natural history and impact on school attendance. Pain 1995;61:139–44.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zempsky WT, O’Hara EA, Santanelli JP, Palermo TM, New T, Smith-Whitley K, Casella JF. Validation of the sickle cell disease pain burden interview-youth. J Pain 2013;14:975–82.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ezenwa MO, Molokie RE, Wang ZJ, Yao Y, Suarez ML, Angulo V, Wilkie DJ. Outpatient pain predicts subsequent one-year acute health care utilization among adults with sickle cell disease. J Pain Symptom Manag 2014;48:65–74.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Dampier C, Palermo TM, Darbari DS, Hassell K, Smith W, Zempsky W. AAPT diagnostic criteria forchronic sickle cell disease pain. J Pain 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Darbari DS, Ballas SK, Clauw DJ. Thinking beyond sickling to better understand pain in sickle cell disease. EurJ Haematol 2014;93:89–95.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Belfer I, Youngblood V, Darbari DS, Wang Z, Diaw L, Freeman L, Desai K, Dizon M, Allen D, Cunnington C, Channon KM, Milton J, Hartley SW, Nolan V, Kato GJ, Steinberg MH, Goldman D, Taylor JGT. A GCHl haplotype confers sex-specific susceptibility to pain crises and altered endothelial function in adults with sickle cell anemia. AmJ Hematol 2014;89:187–93.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Kohli DR, Li Y, Khasabov SG, Gupta P, Kehl LJ, Ericson ME, Nguyen J, Gupta V, Hebbel RP, Simone DA, Gupta K. Pain-related behaviors and neurochemical alterations in mice expressing sickle hemoglobin: modulation by cannabinoids. Blood 2010;116:456–65.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Campbell CM, Carroll CP, Kiley K, Han D, HaywoodJr C, Lanzkron S, Swedberg L, Edwards RR, Page GG, Haythornthwaite JA. Quantitative sensory testing and pain-evoked cytokine reactivity:comparison of patients with sickle cell disease to healthy matched controls. Pain 2016;157:949–56.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Campbell CM, Moscou-Jackson G, Carroll CP, Kiley K, Haywood Jr C, Lanzkron S, Hand M, Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA. An evaluation of central sensitization in patients with sickle cell disease. J Pain 2016;17:617–27.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Darbari DS, Hampson JP, Ichesco E, Kadom N, Vezina G, Evangelou I, Clauw DJ, Taylor VI JG, Harris RE. Frequency of hospitalizations for pain and association with altered brain network connectivity in sickle cell disease. J Pain 2015;16:1077–86.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Tegeder I, Costigan M, Griffin RS, Abele A, Belfer I, Schmidt H, Ehnert C, Nejim J, Marian C, Scholz J, Wu T, Allchorne A, Diatchenko L, Binshtok AM, Goldman D, Adolph J, Sama S, Atlas SJ, Carlezon WA, Parsegian A, Lotsch J, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Geisslinge G, Max MB, Woolf CJ. GTP cyclohydrolase and tetrahydrobiopterin regulate pain sensitivity and persistence. Nat Med 2006;12:1269–77.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Lotsch J, Klepstad P, Doehring A, Dale O. A GTP cyclohydrolase l genetic variant delays cancerpain. Pain 2010;148:103–6.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Brandow AM, Stucky CL, Hillery CA, Hoffmann RG, Panepinto JA. Patients with sickle cell disease have increased sensitivity to cold and heat. Am J Hematol 2013;88:37–43.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Cataldo G, Rajput S, Gupta K, Simone DA. Sensitization of nociceptive spinal neurons contributes to pain in a transgenic model of sickle cell disease. Pain 2015;156:722–30.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Ezenwa MO, Molokie RE, Wang ZJ, Yao Y, Suarez ML, Pullum C, Schlaeger JM, Fillingim RB, Wilkie DJ. Safety and utility of quantitative sensory testing among adults with sickle cell disease: indicators of neuropathic pain? Pain Pract 2016;6:282–93.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Hillery CA, Kerstein PC, Vilceanu D, Barabas ME, Retherford D, Brandow AM, Wandersee NJ, Stucky CL. Transient receptor potential vanilloid l mediates pain in mice with severe sickle cell disease. Blood 2011;118:3376–83.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Vincent L, Vang D, Nguyen J, Gupta M, Luk K, Ericson ME, Simone DA, Gupta K. Mast cell activation contributes to sickle cell pathobiology and pain in mice. Blood 2013;122:1853–62.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications forthe diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011;152:S2-15.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Walk D, Sehgal N, Moeller-Bertram T, Edwards RR, Wasan A, Wallace M, Irving G, Argoff C, Backonja MM. Quantitative sensory testing and mapping: a review of nonautomated quantitative methods for examination of the patient with neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain 2009;25:632–40.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Yarnitsky D, Arendt-Nielsen L, Bouhassira D, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB, Granot M, Hansson P, Lautenbacher S, Marchand S, Wilder-Smith O. Recommendations on terminology and practice of psychophysical DNIC testing. Eur J Pain 2010;14:339.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Garrison SR, Kramer AA, Gerges NZ, Hillery CA, Stucky CL. Sickle cell mice exhibit mechanical allodynia and enhanced responsiveness in light touch cutaneous mechanoreceptors. Mol Pain 2012;8:62.Search in Google Scholar

[27] O’Leary JD, Crawford MW, Odame I, Shorten GD, McGrath PA. Thermal pain and sensory processing in children with sickle cell disease. Clin J Pain 2014;30:244–50.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Jacob E, Chan VW, Hodge C, Zeltzer L, Zurakowski D, Sethna NF. Sensory and thermal quantitative testing inchildrenwith sickle cell disease. J PediatrHematol Oncol 2015;37:185–9.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Kenyon N, Wang L, Spornick N, Khaibullina A, Almeida LE, Cheng Y, Wang J, Guptill V, Finkel JC, Quezado ZM. Sickle cell disease in mice is associated with sensitization of sensory nerve fibers. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2015;240:87–98.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Cain DM, Vang D, Simone DA, Hebbel RP, Gupta K. Mouse models for studying pain in sickle disease: effects of strain, age, and acuteness. Br J Haematol 2012;156:535–44.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zappia KJ, Garrison SR, Hillery CA, Stucky CL. Cold hypersensitivity increases with age in mice with sickle cell disease. Pain 2014;155:2476–85.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Hurtig IM, Raak RI, Kendall SA, Gerdle B, Wahren LK. Quantitative sensory testing in fibromyalgia patients and in healthy subjects: identification of subgroups. Clin J Pain 2001;17:316-22.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Schreiber KL, Martel MO, Shnol H, Shaffer JR, Greco C, Viray N, Taylor LN, McLaughlin M, Brufsky A, Ahrendt G, Bovbjerg D, Edwards RR, Belfer I. Persistent pain in postmastectomy patients: comparison of psychophysical, medical, surgical, and psychosocial characteristics between patients with and without pain. Pain 2013;154:660–8.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Gracely RH, McGrath F, Dubner R. Ratio scales of sensory and affective verbal paindescriptors. Pain 1978;5:5–18.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Gracely RH, Kwilosz DM. The Descriptor Differential Scale: applying psychophysical principles to clinical pain assessment. Pain 1988;35:279–88.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Gracely RH, Dubner R, McGrath PA. Fentanyl reduces the intensity of painful tooth pulp sensations: controlling for detection of active drugs. Anest Analg 1982;61:751-5.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Greenspan JD, Slade GD, Bair E, Dubner R, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Knott C, Diatchenko L, Liu Q, Maixner W. Pain sensitivity and autonomic factors associated with development of TMD: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain 2013;14.T63–74.el-6.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Jaeger B, Reeves JL. Quantification of changes in myofascial trigger point sensitivity with the pressure algometer following passive stretch. Pain 1986;27:203–10.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Kosek E, Ordeberg G. Abnormalities of somatosensory perception in patients with painful osteoarthritis normalize following successfultreatment. EurJ Pain 2000;4:229–38.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Carroll CP, Lanzkron S, Haywood Jr C, Kiley K, Pejsa M, Moscou-Jackson G, Haythornthwaite JA, Campbell CM. Chronic opioid therapy and central sensitization in sickle cell disease. AmJ Prev Med 2016;51:S69-77.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Arendt-Nielsen L. Central sensitization in humans: assessment and pharmacology. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2015;227:79–102.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Sato H, Saisu H, Muraoka W, Nakagawa T, Svensson P, Wajima K. Lackoftemporal summation but distinct aftersensations to thermal stimulation in patients with combined tension-type headache and myofascial temporomandibular disorder. J Orofac Pain 2012;26:288–95.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Schliessbach J, Siegenthaler A, Streitberger K, Eichenberger U, Nuesch E, Juni P, Arendt-Nielsen L, Curatolo M. The prevalence of widespread central hypersensitivity in chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain 2013;17:1502-10.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Li J, Simone DA, Larson AA. Windup leads to characteristics of central sensitization. Pain 1999;79:75–82.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Woolf CJ. Pain: moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:441–51.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Richards N, McMahon SB. Targeting novel peripheral mediators forthe treatment of chronic pain. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:46-51.Search in Google Scholar

[47] King CD, Wong F, Currie T, Mauderli AP, Fillingim RB, Riley3rd JL. Deficiency in endogenous modulation of prolonged heat pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and temporomandibular disorder. Pain 2009;143:172–8.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Campbell CM, France CR, Robinson ME, Logan HL, Geffken GR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in diffuse noxious inhibitory controls. J Pain 2008;9:759–66.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, Klug PP. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1639–44.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Nagel RL, Fabry ME, Steinberg MH. The paradox of hemoglobin SCdisease. Blood Rev 2003;17:167–78.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Cruccu G, Sommer C, Anand P, Attal N, Baron R, Garcia-Larrea L, Haanpaa M, Jensen TS, Serra J, Treede RD. EFNS guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment: revised 2009. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:1010-8.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology 2006;104:570–87.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Wang ZJ, Molokie RE, Wilkie DJ. Does cold hypersensitivity increase with age in sickle cell disease? Pain 2014;155:2439–40.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Kosek E, Ordeberg G. Lack of pressure pain modulation by heterotopic noxious conditioning stimulation in patients with painful osteoarthritis before, but not following, surgical pain relief. Pain 2000;88:69–78.Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia

Articles in the same Issue

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia