Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

-

Mikko Aarnio

, Lieuwe Appel

Graphical Abstract

Abstract

Background and aims

Positron emission tomography (PET) with the radioligand [11C]-D-deprenyl has shown increased signal at location of pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and chronic whiplash injury. The binding site of [11C]-D-deprenyl in peripheral tissues is suggested to be mitochondrial monoamine oxidase in cells engaged in post-traumatic inflammation and tissue repair processes. The association between [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake and the transition from acute to chronic pain remain unknown. Further imaging studies of musculoskeletal pain at the molecular level would benefit from establishing a clinical model in a common and well-defined injury in otherwise healthy and drug-naive subjects. The aim of this study was to investigate if [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake would be acutely elevated in unilateral ankle sprain and if tracer uptake would be reduced as a function of healing, and correlated with pain localizations and pain experience.

Methods

Eight otherwise healthy patients with unilateral ankle sprain were recruited at the emergency department. All underwent [11 C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT in the acute phase, at one month and 6-14 months after injury.

Results

Acute [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake at the injury site was a factor of 10.7 (range 2.9-37.3) higher than the intact ankle. During healing, [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake decreased, but did not normalize until after 11 months. Patients experiencing persistent pain had prolonged [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake in painful locations.

Conclusions and implications

The data provide further support that [11C]-D-deprenyl PET can visualize, quantify and follow processes in peripheral tissue that may relate to soft tissue injuries, inflammation and associated nociceptive signaling. Such an objective correlate would represent a progress in pain research, as well as in clinical pain diagnostics and management.

1 Introduction

Pain is a uniquely personal experience, and self-reports remain the gold standard of assessment. However, self-reports are affected by numerous factors [1]. Objective visualization and quantification of peripheral musculoskeletal injury that generates nociceptive input would represent a progress in pain research. The visualization of pain-associated processes in peripheral tissue would facilitate diagnosis, strengthen patients’ self-report and aid clinical decisions. Further quantification of nociception related processes in peripheral tissue would guide clinical assessment and treatment monitoring.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is increasingly used to diagnose, characterize and monitor disease activity in peripheral inflammatory disorders of both known and unknown origin [2,3]. Nociceptive pain is a cardinal feature of inflammation, and although tissue injury that induces inflammation plays a pivotal role in the generation of pain [4], few studies have localized and quantified the extent of peripheral injury and inflammation in pain patients with molecular imaging.

[11C]-D-deprenyl (D-[N-methyl-11C]N, N-methyl, propargy-lamphetamine) is the D-isomer of deprenyl, a well-characterized monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitor with anti-inflammatory and neuro-protective properties. Based on the available data D-deprenyl binds to MAO enzymes located in the outer mitochondrial membrane of cells engaged in processes involved in inflammation and repair [5]. Previous PET studies have shown high and irreversible [11C]-D-deprenyl ([11C]DDE) uptake in synovial inflammation of knees in rheumatoid arthritis patients [6] and in patients with chronic whiplash associated disorder [11C]DDE uptake was increased in the painful neck regions [7]. These studies strongly suggest an association of [11C]DDE uptake in soft tissue injury and inflammation with associated pain. However, it is not known if [11C]DDE PET can indicate acute tissue damage and pain, and if the healing process can be followed over time in the setting of acute injury. The purpose of this study was to verify and extend previous [11C]DDE-PET findings by investigating tracer retention in unilateral ankle sprain. Traumatic ankle sprain presents a suitable model with substantial pain in the acute phase and reasonably rapid resolution of pain within months. With isolated traumatic ankle sprain, the intact ankle can be used as a within-subject nonaffected control. The hypotheses were that [11C]DDE uptake would be acutely elevated localized to injured tissues, reduced as a function of healing, and correlated with subjective pain localizations and pain experience.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Patients and study design

Eight non-smoking patients with an acute isolated traumatic ankle sprain, diagnosed by an orthopedic surgeon, were recruited at the emergency department at Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden. No patient had a history of a somatic or psychiatric disease or drug abuse.

The study design consisted of three [11C]DDE PET/CT investigations on both ankles of each patient. The first imaging occasion (acute phase; ACP) was scheduled within 5 days after the injury. The first follow-up imaging occasion (FU1) was scheduled 6 ±1 weeks after the injury in order to monitor the subacute or repair phase of the tissue injury. The second follow-up (FU2) was scheduled 6 ± 1 months after the injury in order to monitor the remodeling phase of the tissue injury. During the course of the study it was noticed that complete healing and recovery of the injured peripheral tissue might take longer time than expected. Therefore, three of the patients had their FU2 imaging between 9 and 14 months after the injury. Before each PET/CT investigation, all patients refrained from analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs for 24 h, from alcohol and caffeine for 12 h, and from food for 3 h.

2.2 Pain assessment

Immediately before and after PET/CT investigations, patients rated their average resting pain levels in the feet on a visual analogue scale (VAS), ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain). The locations of maximal tenderness were palpated and marked on an anatomical picture of the foot. The patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the included patients.

| Case | Gender[a] | Age | Cause ofinjury | Day ofinvestigation[b] | VAS at rest[c] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| ACP | FU1 | FU2 | ACP | FU1 | FU2 | ||||

| 1 | M | 31 | Inversion in football | 4 | 37 | 194 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 21 | Inversion in stairs | 2 | 35 | 420 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | M | 28 | Inversion in floorball | 5 | 40 | 336 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 4 | M | 32 | Fall from ladders | 2 | 36 | 163 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | F | 20 | Inversion in football | 9 | 65 | 161 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 6 | F | 50 | Fall from chair | 2 | 37 | 210 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | M | 38 | Inversion after jump | 3 | 44 | 174 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | F | 58 | Inversion when walking | 2 | 37 | 262 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

2.3 PET/CT scanning

The radioligand [11C]DDE was produced at the chemistry section of the Uppsala PET center according to a standard manufacturing procedure with previously published methods [8,9]. All patients were investigated with a GE Discovery ST PET/CT scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The scanner provides 47 contiguous planes of data with a distance of 3.27 mm and 3.125 mm transaxial and axial resolution: this gives a total axial field of 15.7 cm. Patients were scanned in the supine position with the feet gently supported by a vacuum cushion to minimize foot and ankle movement. The PET/CT investigation was initiated with a short CT scan (140 kV; auto mA 10-80 mA) for attenuation correction of the PET emission data. Each patient received an intravenous bolus of approximately 5 MBq/kg [11C]DDE in an antecubital vein. Simultaneously, a dynamic emission scan (3D mode) was initiated with a predetermined set of measurements (frames of 4 × 30; 3 × 60; 2 × 300, and 3 × 600 s) for up to 45 min. PET data were reconstructed with the OSEM (Ordered Subset Expectation Maximization) algorithm with 2 iterations and 21 subsets and with a 2.57 mm wide post-processing filter. PET data were corrected for decay, photon attenuation, scatter, random coincidences and dead time.

2.4 Image analysis

The image analysis was performed with VOIager (version 2.0.5; GE Healthcare 2009). A summation image (25-45 min post tracer injection) was used for delineation of regions of interest (ROI). First, in each imaging occasion the lesions were identified visually from the area with elevated [11C]DDE uptake above the background signal. Second, an irregular ROI was delineated manually by drawing an isocontour that was defined as 50% of the maximum voxel signal intensity within the lesion. Isocontours were outlined in multiple adjacent axial slices showing tracer uptake within the target lesion resulting in a polygonal volume of interest (VOI) for each defined region. The superimposed CT image was used to delineate anatomically corresponding reference regions of the same size in the contralateral foot. For images from the other two occasions, the same regions as in the original lesion were defined from residual [11C]DDE uptake, and if there was no elevated [11C]DDE uptake, VOIs were delineated and positioned anatomically using the CT images. The defined regions of interest were checked, identified and named in consultation with an experienced PET radiologist. Because of the limits of spatial resolution in PET/CT, the defined anatomical locations were approximate, corresponding to the nearest identifiable region in superimposed CT image and may also have included surrounding tissue.

2.5 Data analysis

Time activity (TACT) data were generated for all scans from each patient: this represented the dynamic sequence of radioactivity levels for the VOI in each PET/CT scan from 0 to 45 min. The TACT data were standardized with respect to the administered dose of radioactivity and the patient’s body weight, resulting in a standardized uptake value (SUV).

For the generation of SUV-related parameters, the data from 25 to 45 min post tracer administration was used to limit the effects of blood flow. In the summation image the mean and maximum voxel value were derived for each VOI (SUVMEAN and SUVMAX, respectively). subsequently, SUVRATIO was computed for each VOI as the ratio of SUVMEAN between the injured foot and the non-injured foot.

2.6 Statistical analysis

SUVMEAN, SUVMAX and SUVRATIO were evaluated within and between scans for each patient. Differences in SUVMEAN, SUVMAX and SUVRATIO were evaluated with Wilcoxon’s matched pairs test. Correlations between SUVMEAN, SUVMAX and SUVRATIO and subjective pain ratings were assessed with Spearman’s Rank Order test. Unless otherwise stated, results are presented as median (range) values.

subjective pain rating and elevated uptakes were also dichotomized (to presence/non-presence) for both feet for all patients at all three investigations. The dichotomized data was analyzed using a mixed logistic regression model [10], using pain as the response variable and elevated uptake, patient ID and investigation number as explanatory variables.

3 Results

3.1 Clinical and radiographic results

The most common mechanism of injury was lateral ankle inversion sprain present in five out of eight patients. There were no injuries to the bone structure or dislocations observed on plain radiographs or from computed tomography in any of the patients. Pain at rest (VAS) decreased markedly from 2.5 (1-8) at ACP to 0 (0-3) at FU1 (p = 0.011). VAS ratings did not change significantly between FU1 and FU2 (p = 0.890). See also Table 1. At ACP, no patients could support themselves completely on the injured foot and they reported intense pain during weight bearing. At FU1 and FU2, all eight patients still experienced pain with extreme ankle joint movements or pain during heavy weight bearing on the injured foot, however, this pain was less intense than at ACP.

3.2 PET/CT results

At ACP an elevated regional [11C]DDE uptake was observed in the injured foot in all patients, with only a very low tracer uptake present in the non-injured foot. The regions of elevated tracer uptake corresponded with clinical findings and painful locations. A typical patient is presented in Fig. 1.

![Fig. 1

Patient case illustrating the acute phase. Regions of elevated [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake corresponded with clinical findings and painful locations.

A 31-year-old male (case 1) four days after an inversion injury in the right midfoot. (a) Fused [11C]DDE PET/CT images of the feet of (highest value in purple). The images illustrate the plantar region of uptake between cuneiform and 1st, 2nd and 3rd metatarsal bones. The crosshair points to elevated [11C]DDE uptake in the calcaneocuboid joint and regions between cuboideum and 5th metatarsal bone. (b) A photograph of the same right foot with the points of maximal tenderness (stars) corresponding to the regions of high [11C]DDE uptake. (c) An anatomical image of the right foot with the tender points and crosshair in corresponding locations. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)](/document/doi/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.10.008/asset/graphic/j_j.sjpain.2017.10.008_fig_002.jpg)

Patient case illustrating the acute phase. Regions of elevated [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake corresponded with clinical findings and painful locations.

A 31-year-old male (case 1) four days after an inversion injury in the right midfoot. (a) Fused [11C]DDE PET/CT images of the feet of (highest value in purple). The images illustrate the plantar region of uptake between cuneiform and 1st, 2nd and 3rd metatarsal bones. The crosshair points to elevated [11C]DDE uptake in the calcaneocuboid joint and regions between cuboideum and 5th metatarsal bone. (b) A photograph of the same right foot with the points of maximal tenderness (stars) corresponding to the regions of high [11C]DDE uptake. (c) An anatomical image of the right foot with the tender points and crosshair in corresponding locations. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

In five out of eight cases, the most common locations for increased signal intensity were the anterior talofibular ligament, the calcaneofibular ligament and parts of the deltoid ligament (Table 2).

Regions of the most elevated [11C]-D-deprenyl-uptake. Standardized uptake values (SUV) and the ratio between injured and non-injured foot are given for the acute phase and follow-up investigations.

| Case | Anatomical location[a] | SUVMAX[b] | SUVRATIO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| ACP | FU1 | FU2 | ACP | FU1 | FU2 | ||

| 1 | Calcaneocuboid joint R | 4.9 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 2.2 |

| Plantar tarsometatarsal ligaments/tarsometatarsal joint between cuboideum and 5th metatarsal R | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4,2 | 3.4 | 5.1 | |

| Plantar tarsometatarsal ligaments/tarsometatarsal joints between cuneiform and 1st, 2nd and 3rd metatarsal R | 3.0 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 5.5 | 2.2 | |

| 2 | Anterior talofibular ligament (FTA) and calcaneofibular ligament (FC) L | 2.4 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 6.6 | 4.3 | 1.4 |

| Talar neck and anterior tibiotalar part of deltoideus L | 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 6.6 | 4.8 | 1.0 | |

| Tibiocalcaneal part of deltoid ligament L | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 1.0 | |

| Dorsal calcaneocuboidal ligament/calcaneocuboid joint L | 3.0 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 8.8 | 4.3 | 1.3 | |

| 1st Cuneiform bone (medial. insertion of tendon tibialis anterior) L | 3.1 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 9.7 | 2.9 | 1.4 | |

| 3 | Anterior talofibular ligament (FTA) L | 2.7 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 6.0 | 2.4 | 1.3 |

| Medial aspects of talocrural joint L | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 7.7 | 5.3 | 0.7 | |

| Posterior talofibular ligament (FTP) L | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 4.6 | 2.5 | 0.7 | |

| 4 | Calcaneofibular ligament (FC) R | 5.1 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 15.2 | 8.0 | 3.3 |

| Space between the calcaneus and the Achilles tendon R | 5.2 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 17.3 | 7.4 | 2.4 | |

| Ventrally from medial malleolus and navicular bone/talonavicular ligament R | 3.7 | 4.9 | 3.6 | 10.6 | 7.8 | 6.3 | |

| 5 | Anterior talofibular ligament (FTA) L | 2.3 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 8.0 | 9.7 | 2.6 |

| Posterior tibiotalar part of deltoid ligament L | 2.4 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 14.8 | 6.4 | 7.8 | |

| Insertion of the calcaneofibular ligament (FC) L | 2.5 | 4.3 | 1.6 | 20.1 | 8.3 | 3.8 | |

| 6 | Interosseus talocalcaneal ligament/sinus tarsi L | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 38.4 | 27.1 | 1.1 |

| Sustentaculum tali L | 3.5 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 44.1 | 9.9 | 6.9 | |

| Anterior tibiotalar part of the deltoid ligament L | 2.9 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 29.0 | 4.6 | 1.1 | |

| Medial process ofcalcaneus L | 2.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 36.1 | 4.9 | 4.3 | |

| 7 | Anterior and posterior parts of the deltoid ligament L | 3.3 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 11.3 | 2.8 | 2.4 |

| Calcaneofibular ligament (FC) L | 3.3 | 4.4 | 0.4 | 11.5 | 8.4 | 1.2 | |

| Anterior talofibular ligament (FTA) S. interosseus talocalcaneal ligament (IOL) L | 3.2 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 8.7 | 4.6 | 1.8 | |

| Dorsal parts of navicularbone L | 2.2 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 12.4 | 6.9 | 2.6 | |

| Short plantar ligament | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 13.3 | 3.1 | 0.7 | |

| 8 | Medial malleolus surface of the talus R | 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 12.8 | 5.1 | 2.0 |

| Calcaneofibular ligament (FC) R | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 11.6 | 7.3 | 1.6 | |

| Interosseus talocalcaneal ligament (IOL) R | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 11.6 | 5.8 | 3.7 | |

| Anterior tibiofibular ligament (FTA) R | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 3.7 | |

| Talonavicular ligament R | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 3.0 | |

| Anterior tibiotalar part of the deltoid ligament R | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 4.8 | |

The SUVMEAN of the lesions was 1.9 (1.2–3.1) at ACP, 1.7 (0.4–3.0) at FU1, and 0.8 (0.2–1.8) at FU2. In the corresponding anatomical locations in the non-injured foot, the SUVMEAN was similar at each imaging occasion: 0.3 (0.1–1.1), 0.3 (0.1–0.6) and 0.3 (0.1–0.6) at ACP, FU1 and FU2, respectively.

The SUVMAX of the lesions was similar at ACP and FU1: 2.8 (1.8–5.1) at ACP and 2.8 (0.7–4.7) at FU1. However, the SUVMAX was substantially smaller 1.2 (0.4–3.2) at FU2. The decrease in SUVMAX between ACP and FU2 was 57% (p = 0.012). In the corresponding anatomical locations in the non-injured foot, SUVMAX was similar at each imaging occasion: 0.5 (0.1–1.2), 0.6 (0.1–1.0) and 0.6 (0.2–1.1) at ACP, FU1 and FU2, respectively.

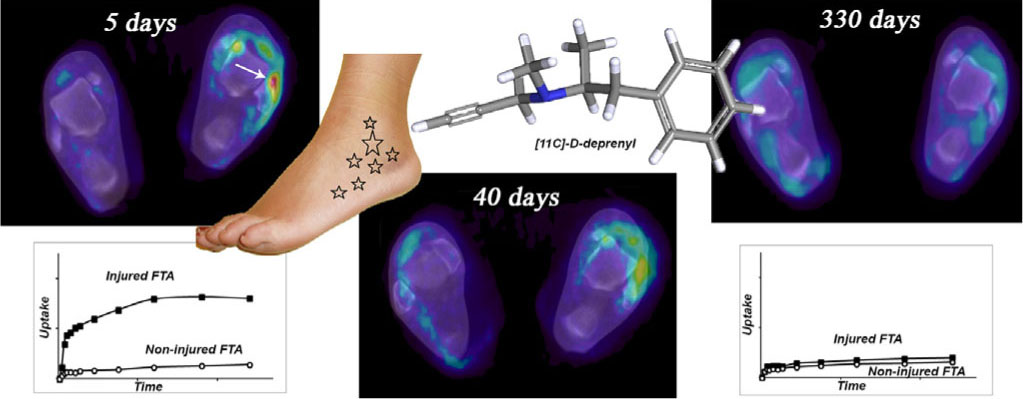

The SUVRATio showed that the regional [11C]DDE uptake in the injured locations was initially 10.7 (2.9–37.3) times higher than tracer uptake in the corresponding regions of the non-injured foot. The SUVRATIO reduced to 5.6 (2.5–8.3) at FU1 and 2.8 (0.7–3.8) at FU2. [11C]DDE uptake decreased by 48% (p = 0.017) between ACP and FU1, and by 50% (p = 0.012) between FU1 and FU2. The decrease between ACP and FU2 was 74% (p = 0.017). A typical patient illustrating these findings is presented in Fig. 2.

![Fig. 2

Patient case illustrating decreased [11C]DDE uptake between acute injury and follow-up.

A 20-year-old female (case 3) with a classic lateral inversion ankle sprain. The top row displays fused transaxial [11C]DDE PET/CT images of the feet. The color bar indicates SUV values from 0 (dark blue) to 2.5 (red). Location of left anterior fibulotalar ligament (FTA) is indicated by a white arrow. The bottom row displays respective time activity (TACT) curves (black rectangles represent injured FTA and white circles control region). The bar indicates SUVMEAN values from 0 (bottom) to 2.5 (top). The gray rectangle indicates the data (25–45 min post tracer administration) that was used for the generation of dependent variables (SUVMEAN, SUVMAX and SUVRATIO). The region of FTA initially showed visually significant [11C]DDE uptake that was undetectable 11 months after the injury indicating recovery of the tissue damage. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)](/document/doi/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.10.008/asset/graphic/j_j.sjpain.2017.10.008_fig_003.jpg)

Patient case illustrating decreased [11C]DDE uptake between acute injury and follow-up.

A 20-year-old female (case 3) with a classic lateral inversion ankle sprain. The top row displays fused transaxial [11C]DDE PET/CT images of the feet. The color bar indicates SUV values from 0 (dark blue) to 2.5 (red). Location of left anterior fibulotalar ligament (FTA) is indicated by a white arrow. The bottom row displays respective time activity (TACT) curves (black rectangles represent injured FTA and white circles control region). The bar indicates SUVMEAN values from 0 (bottom) to 2.5 (top). The gray rectangle indicates the data (25–45 min post tracer administration) that was used for the generation of dependent variables (SUVMEAN, SUVMAX and SUVRATIO). The region of FTA initially showed visually significant [11C]DDE uptake that was undetectable 11 months after the injury indicating recovery of the tissue damage. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

At later stages (FU1 and FU2), additional regions of elevated [11C]DDE uptake were observed in the injured foot and even in the non-injured foot. Two patients (cases 5 and 7) had elevated [11C]DDE uptake in the non-injured foot, that was also noted at ACP (Table 3).

New regions with elevated [11C]-D-deprenyl-uptake in the injured and the non-injured foot during the follow-up investigations.

| Case | Anatomical locationa | SUVMAXb | SUVRATIO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| ACP | FU1 | FU2 | ACP | FU1 | FU2 | ||

| 1 | Subtalar joint (posteriorpart) L | 1.1 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 2.4 |

| Origin of calcaneofibular ligament (FC) L | 1.0 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 1.9 | |

| Sustentaculum tali L. | 0.5 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.0 | |

| 4 | Calcaneus (posterior and lateral parts) L | 0.2 | 0.4 | 5.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3.1 |

| Talocrural joint/trochlear tali R | 2.2 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 7.0 | 17.0 | 4.3 | |

| 5 | Calcaneus (posterior and lateral parts) R | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 4.7 |

| Subtalar joint (middle and anterior articulation) and sinus tarsi R | 4.7 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 3.6 | |

| Dorsal calcaneocuboidal ligament/calcaneocuboid joint L | 0.6 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 6.8 | |

| Anterior part of ankle joint capsule L | 1.8 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 13.2 | |

| Posterior tibiotalarpart of the deltoid ligament L | 1.6 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 4.5 | |

| 6 | Ligament/joint between cuboideum and 5th metatarsal R | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 19.0 | 13.1 |

| Dorsal parts of the neck of talus L | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 3.3 | |

| Dorsal tarsometatarsal joint between ACP cuneiform and ACP metatarsal L | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 6.2 | |

| Sulcus calcanei L | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 5.4 | 1.2 | 4.0 | |

| Plantar calcaneonavicular ligament L | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 6.3 | 1.1 | 3.9 | |

| 7 | Origin of posterior tibiotalar part of deltoid ligament R | 2.0 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 7.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Flexor digitorum brevis muscle R | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 3.1 | |

| 8 | Sustentaculum tali L | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 6.5 |

Explanations as in Table 2

Anatomical locations in the non-injured foot are shown in bold

Anatomical locations presented in cursive were visually detected in the acute phase

The correlation between FU1 SUVRATIO and FU2 VAS pain score was r = 0.764 (p = 0.03). No other correlations between self reported pain intensity at rest (VAS) and SUV values were present at ACP, FU1 or FU2. However, dichotomized pain was significantly associated with dichotomized elevated uptake (p = 0.036). The estimated odds ratio for presence of pain for feet with elevated uptake compared to feet with no elevated uptake was OR = 5.06 (Table 4).

4 Discussion

Accumulation of [11C]DDE uptake in the injured tissue was evident in painful locations in all patients after injury, confirming the initial hypothesis. The relatively high regional [11C]DDE uptake, compared to surrounding structures, was localized in the regions of the ligaments and joints and was concurrent with the clinical examination and the mechanism of injury. The uptake of [11C]DDE tracked the normal recovery process of acute traumaticankle sprains. The tracer uptake was still elevated several months after initial injury, and patients with persistent pain had prolonged [11C]DDE uptake at the injury site.

4.1 Characteristics of [11C]DDE uptake

The ratio of uptake between the injured and the reference regions provided the best demonstration of high initial [11C]DDE uptake and a recovery-associated decrease. The SUVMAX value was less sensitive, but this value is less dependent on the placement and drawing of ROI and is not as reproducible as the SUVMEAN value [11,12]. Because kinetic modeling of tracer uptake has many unknowns, we opted to base all analyses on data obtained 25–45 min post tracer injection. Although SUV may be an oversimplification of physiological events, and as a quantitative index, is vulnerable to several sources of variability [13,14,15], SUV was used because of its simplicity, blood sampling is unnecessary, and because it is well suited for exploratory follow-up with a control region. During follow-up, the SUV values in the control regions were stable; indicating the reliability of SUVMEAN and SUVMAX was good.

The localization of the tracer uptake correlated with the expected anatomical localization in acute ankle sprains.The anterior talofibular ligament is commonly injured in a lateral ankle sprain due to its low load tolerance and anatomical position. The tracer uptake in the mid-foot ligaments was expected [16], although the high amount of uptake near the medial joint area or the deltoid ligament was a new finding.

The normal recovery process [17] was reflected by serial PET imaging. New regions of increased uptake that represented new tender points in the injured foot were evident over time. The time needed for completion of healing and recovery of ankle sprains varies and the incidence of residual complaints is high years after injury [16,17,18]. Increased [11C]DDE uptake was evident several months after initial injury. The new regions of increased tracer uptake in the injured foot in some cases might be the result of abnormal kinematics with ligament insufficiency and the first signs of degenerative and/or adaptive changes [19]. Ligament instability alters the contact mechanics in the joint and causes wear and increased shear loading along with inflammatory processes [20,21]. Some patients could have suffered slight re-injury as this is common after ankle sprains without recalling or reporting it. The same explanations could account for some regions with high initial tracer uptake and no decrease during follow-up. Increased loading and overuse of the non-injured foot, with increased stress to the joints and bone surfaces, might cause the observed elevation in tracer uptake on the non-injured side.

4.2 Pain and [11C]DDE uptake

Pain while weight bearing and pain during extreme movements of the ankle joint coexisted with increased [11C]DDE uptake. The odds of a patient having pain was more than 5 times higher given an elevated uptake compared to no elevated uptake. In line with Table 4, this means that 30% of all patients have pain in feet with no elevated uptake, 68% of all patients will have pain in feet with elevated uptake. Although SUVRATIO at first follow-up was positively correlated with pain at last follow-up, there were no other correlations between pain intensity (VAS-score) at rest and the SUV-related measures. There may be a relationship between [11C]DDE uptake and subsequent risk of persisting pain following trauma. This is reasonable if the initial [11C]DDE uptake is associated with severity of injury [22]. However, in a large seven-year follow-up of 648 patients with sprained ankles, there was no correlation between initial severity of the sprain and residual disability at follow-up [16]. The perception of pain is not a simple linear phenomenon, and nociceptive input can be modulated at several levels of the pain pathway, which would attenuate the direct influence of the primary processes at the injury site. subjective pain estimates were measured at rest without any provocation or loading of the ankle joint or attempt to measure mechanical ankle laxity or instability. It is difficult to standardize such a provocation, but more rigorous pain analysis and a measurement of disability are needed in future studies to address the link between peripheral pain induction on the molecular level and subjective pain experience.

4.3 The limitations of the study and [11C]DDE uptake mechanism

The limitations of this study are the small sample size and that the exact mechanism of the observed [11C]DDE uptake is not fully known. The small sample size gives us lesser statistical power to detect differences. However, we believe that the sample size is appropriate for PET pilot study to describe and assess feasibility of using [11C]DDE PET/CT in visualization of peripheral inflammation in musculoskeletal injury. D-deprenyl uptake appeared to take place mostly during the inflammatory phase of injury repair but was still noticeable in the proliferative and remodeling phases. Available data suggest that the major candidate for the binding site for D-deprenyl is mitochondrial MAO inside cells engaged in processes involved in inflammation and repair [5,23]. The role of MAO in inflammation is not fully studied. However, it has been shown that the MAO activity of human granulocytes and lymphocytes is predominantly of the B form [24] but in inflammation, MAO-A is one of the signature markers that is modified by interleukins and the expression of enzymes is strongly upregulated in activated monocytes and macrophages [25]. Deprenyl was originally synthesized as a “psychic energizer” through combining amphetamine and pargyline, a MAO inhibitor, in the same molecule. D-deprenyl is a more potent inhibitor of MAO-A but it is up to 25–500 times less potent as an MAO-B inhibitor than its mirror isomer L-deprenyl [26,27,28] and therefore D-deprenyl has been utilized as a MAO-B inactive control tracer for brain studies [8]. Trapping mechanisms, other than binding to a specific molecular structure, are possible at the site of injury or inflammation. As the [11C]DDE molecule is a weak lipophilic base, non-specific trapping mechanisms could include elevated blood flow, increased vascular permeability and enhanced transudation at the injury site. Full kinetic modeling of tracer uptake had been necessary to fully exclude blood flow components of tracer uptake. However, the exact mechanism of peripheral [11C]DDE trapping was not known, so we did not obtain arterial blood sampling for patient safety concerns. In the dynamic PET, the rapid increase in the first frames was followed by a slight washout or plateau being present in the last frames, suggesting a mechanism of irreversible or slowly reversible tracer trapping. The shape of time activity curves indicates that enhanced blood flow is unlikely sole mechanism of tracer uptake. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the exact uptake mechanism of D-deprenyl and to characterize what parts of the injury-inflammation cascade are visualized by [11C]DDE PET.

5 Conclusions

The present investigation demonstrates that molecular aspects of tissue lesions presenting with inflammation and pain may be visualized, quantified, and followed over time with PET/CT with [11C]DDE being a promising tracer. [11C]DDE may be valuable for identifying patients with problematic healing and prolonged inflammation and who are at high risk for developing persisting pain.

6 Implications

This relatively noninvasive technique represents an objective finding indicating processes in tissue injury from which nociceptive signals originate. Such an objective correlate would represent a progress in pain research, as well as in clinical pain diagnostics and management.

Highlights

An increased [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake is shown in painful locations after ankle sprain.

Patients experiencing persistent pain had prolonged peripheral D-deprenyl uptake.

The described method can visualize, quantify and follow pain generating processes.

Such an objective correlate may represent a progress in pain research and management.

-

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Uppsala University, Sweden, and by the Radiation Ethics and Safety Committee of Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

-

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the staff of the PET-center in Uppsala, Sweden, for tracer synthesis, scanning and assistance during data evaluation. Professor Anders Sundin is acknowledged for his help in the identification and naming of anatomical structures.

Abbrevianons

- PET

-

positron emission tomograpny

- PEI/CI

-

positron emission tomograpny/computea tomograpny

- MAO

-

monoamine oxidase; [11CjDDE, [11C]-D- deprenyl

- ACP

-

acute phase

- FU1

-

first follow-up

- FU2

-

second follow-up

- VAS

-

visual analogue scale

- SUV

-

standardized uptake value

- ROI

-

region ofinterest

- VOI

-

volume of interest

- TACT

-

time activity

- FTA

-

anterior fibulotalar ligament

References

[1] Gendreau M, Hufford M, Stone A. Measuring clinical pain in chronic widespread pain: selected methodological issues. Best Pract Res Cli Rheumatol 2003;17:575–92.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Basu S, Zhuang H, Torigian D, Rosenbaum J, Chen W, Alavi A. Functional imaging of inflammatory diseases using nuclear medicine techniques. Semin Nucl Med 2009;39:124–45.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gotthardt M, Bleeker-Rovers CP, Boerman OC, Oyen WJ. Imaging of inflammation by PET, conventional scintigraphy, and other imaging techniques. J Nucl Med 2010;51:1937–49.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ji RR, Chamessian A, Zhang YQ. Pain regulation by non-neuronal cells and inflammation. Science 2016;354:572–7.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lesniak A, Aarnio M, Jonsson A, Norberg T, Nyberg F, Gordh T. High-throughput screening and radioligand binding studies reveal monoamine oxidase-B as the primary binding target for D-deprenyl. Life Sci 2016;152:231–7.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Danfors T, Bergstrom M, Feltelius N, Ahlstrom H, Westerberg G, Langstrom B. Positron emission tomography with 11 C-D-deprenyl in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Evaluation of knee joint inflammation before and after intra-articular glucocorticoid treatment. Scand J Rheumatol 1997;26:43–8.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Linnman C, Appel L, Fredrikson M, Gordh T, Soderlund A, Langstrom B, Engler H. Elevated [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake in chronic Whiplash Associated Disorder suggests persistent musculoskeletal inflammation. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e19182.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Fowler JS, MacGregor RR, Wolf AP, Arnett CD, Dewey SL, Schlyer D, Christman D, Logan J, Smith M, Sachs H. Mapping human brain monoamine oxidase A and Bwith 11C-labeled suicide inactivators and PET. Science 1987;235:481–5.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Macgregor R, Fowler J, Wolf A, Halldin C, Langstrom B. Synthesis of suicide inhibitors of monoamine oxidase: carbon-11 labeled clorgyline, L-deprenyl and D-deprenyl. J Label Compd Radiopharm 1988;25:1–12.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Agresti A. Foundations of linear and generalized linear models. Wiley; 2015. p. 472.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Nahmias C, Wahl L. Reproducibility of standardized uptake value measurements determined by 18F-FDG PET in malignant tumors. J Nucl Med 2008;49:1804–8.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Krak N, Boellaard R, Hoekstra O, Twisk J, Hoekstra C, Lammertsma A. Effects of ROI definition and reconstruction method on quantitative outcome and applicability in a response monitoring trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005;32:294–301.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Hamberg L, Hunter G, Alpert N, Choi N, Babich J, Fischman A. The dose uptake ratio as an index of glucose metabolism: useful parameter or over simplification? J Nucl Med 1994;35:1308–12.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Keyes JJ. SUV: standard uptake or silly useless value? J Nucl Med 1995;36:1836–9.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Huang S. Anatomy of SUV. Standardized uptake value.Nucl Med Biol 2000;27:643–6.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Konradsen L, Bech L, Ehrenbjerg M, Nickelsen T. Seven years follow-up after ankle inversion trauma. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2002;12:129–35.Search in Google Scholar

[17] vanRijn RM, vanOs AG, Bernsen RM, Luijsterburg PA, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. What is the clinical course of acute ankle sprains? A systematic literature review. Am J Med 2008;121, 324-31.e6.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Hubbard T, Hicks-Little C. Ankle ligament healing after an acute ankle sprain: an evidence-based approach. JAthl Train 2008;43:523–9.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Hintermann B, Boss A, Schafer D. Arthroscopic findings in patients with chronic ankle instability. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:402–9.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Hirose K, Murakami G, Minowa T, Kura H, Yamashita T. Lateral ligament injury of the ankle and associated articular cartilage degeneration in the talocrural joint: anatomic study using elderly cadavers. J Orthop Sci 2004;9:37–43.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Fleming B, Hulstyn M, Oksendahl H, Fadale P. Ligament injury, reconstruction and osteoarthritis. CurrOpin Orthop 2005;16:354–62.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Clay FJ, Watson WL, Newstead SV, McClure RJ. A systematic review of early prognostic factors for persisting pain following acute orthopedic trauma. Pain Res Manag 2012;17:35–44.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Anna L, Mikko A, Shanti D, Thomas N, Fred N, Torsten G. Characterization of the binding site for D-deprenyl in synovial membranes from arthritic patients; 2017. Unpublished work.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Balsa MD, Gomez N, Unzeta M. Characterization of monoamine oxidase activity present in human granulocytes and lymphocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1989;992:140–4.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Cathcart MK, Bhattacharjee A. Monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A): a signature marker of alternatively activated monocytes/macrophages. Inflamm Cell Signal 2014;1.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Magyar K, Vizi E, Ecseri Z, Knoll J. Comparative pharmacological analysis of the optical isomers of phenyl-isopropyl-methyl-propinylamine (E-250). Acta Physiol Acad Sci Hung 1967;32:377–87.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Knoll J, Magyar K. Some puzzling pharmacological effects of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol 1972;5:393–408.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Robinson JB. Stereoselectivity and isoenzyme selectivity of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Enantiomers of amphetamine, N-methylamphetamine and deprenyl.Biochem Pharmacol 1985;34:4105–8.Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia

Articles in the same Issue

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia