Abstract

Background and aims

Pain is common in older adults but may be undertreated in part due to concerns about medication toxicity. Analgesics may affect cognition. In this retrospective cohort study, we used the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database to examine the interaction of cognitive status and medications, especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). We hypothesized NSAID use would be associated with cognition and that this could be mediated through changes in brain structure.

Methods

In this post hoc analysis of the ADNI database, subjects were selected by searching the “concurrent medications log” for analgesic medications. Subjects were included if the analgesic was listed on the medication log prior to enrollment in ADNI and throughout the study. Subjects taking analgesics, particularly NSAIDs, at each study visit were compared to control subjects taking no analgesics. Using descriptive statistics as well as univariate, multivariate and repeated measure ANOVA, we explored the relationship between NSAID use and scores for executive function and memory related cognitive activities. We further took advantage of the extensive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data available in ADNI to test whether cognitive change was associated with brain structure. The multitude of imaging variables was compressed into a small number of features (five eigenvectors (EV)) using principal component analysis.

Results

There were 87 NSAID users, 373 controls, and 71 taking other analgesics. NSAID use was associated with higher executive function scores for cognitively normal (NL) subjects as well as subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). NSAID use was also associated with higher memory scores, but for NL females only. We analysed MRI data using principal component analysis to generate a set of five EVs. Examining NL and MCI subjects, one EV had significantly larger values in subjects taking NSAIDs versus control. This EV was one of two EVs which significantly correlated with composite executive function and memory scores as well as cognitive diagnosis.

Conclusions

NSAID use was associated with higher executive function, and memory scores in certain subjects and larger cortical volumes in particular regions. Limitations of the study include secondary analysis of existing data and the possibility of confounding.

Implications

These results suggest it is important to consider the secondary effects of medications when choosing a treatment regimen. Further prospective studies are needed to examine the role of analgesics on cognition and whether NSAIDs act through cortical dimension changes and how they are related to gender and cognitive diagnosis.

1 Introduction

Pain is common in older adults. In studies of community-dwelling older adults aged 65 or greater in the United States, the prevalence of reported pain ranged from 52.9 to 78.3% [1,2]. In studies of community-dwelling older adults with dementia the prevalence of pain was 52.9-57.3% by self-report, greater with caregiver report [3,4].

Pain may be pharmacologically undertreated in older adults. In a study of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and greater, of those subjects who reported pain, 28% were not using pain medications [2]. In a study of older adults aged 70 or greater, only 29% of those reporting chronic pain were using analgesics daily [1]. Pain may be undertreated in older adults in part due to concerns about medication toxicity. In choosing therapy it is important to consider side effects and to weigh the risks and benefits of each class of drug. Age related changes occur that may affect the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses to medications. Comorbid conditions are common and can further affect the response to drugs [5]. Acetaminophen may be associated with hepatotoxicity. Older patients using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be at greater risk of gastrointestinal side effects [6]. NSAIDs also have renal and cardiovascular risks [7]. Opioids may be associated with increased risk of injuries such as falls and fractures in older adults [8]. Opioids also carry risks such as respiratory depression, constipation, and nausea.

Analgesics may also affect cognitive function. In some studies, opioid treatment in subjects with chronic pain had adverse effects on cognition [9,10]. In a longitudinal study, the use of opioids alone or in combination with benzodiazepines or other centrally acting medications at baseline predicted cognitive decline at follow-up in an elderly population [11]. In other studies, opioid treatment in subjects with chronic pain has been shown to have either no or positive effects on cognition, suggesting reductions in pain may have beneficial effects on pain-related cognitive impairment [12,13,14].

Interestingly, the role of NSAIDs in modulating the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been studied in recent years. Several epidemiological studies have shown the use of NSAIDs may decrease the risk of developing AD [15,16,17]. Some longitudinal studies have shown NSAID use is associated with less cognitive decline over time compared to no use [18,19]. Other studies have found no differences in the incidence of AD or alteration in cognitive trajectories with the use of NSAIDs compared to placebo [20,21]. One possibility likely involved in the apparent variation in outcome is the fact that AD is an illness that develops over many years. NSAIDs may only protect against cognitive decline with prolonged use at early stages prior to the development of symptoms [15,22,23].

We used the longitudinal Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database to examine the interaction of baseline cognitive status and analgesic use, focusing on NSAIDs, on cognitive function and structural brain changes. We hypothesized that NSAID use could be associated with cognition and brain structure. Since Alzheimer’s progression is associated with both decreased cognitive performance and altered brain structure, we hypothesized that NSAID use and brain structure could be associated with an altered risk of transitioning from milder to more severe AD.

2 Methods

2.1 ADNI database

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI database was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, positron emission tomography, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. [For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org.]

In the ADNI database, part I, there were 1435 research identification numbers for which n = 819 were populated by demographics including age, gender, body mass index, apolipoprotein E4 status, blood pressure and heart rate. Subjects, between 55 and 90 years of age, were followed for 2-3 years from enrollment; assessments, including neuropsychological tests and MRIs, were performed at six month intervals. All MRI images were archived by ADNI, and the study volumes were acquired with Freesurfer software and analysed with J-image by the ADNI Center at UCSF. The most recent data was downloaded on January 30, 2014 at which time all the currently active datasets were updated. The ADNI database has previously been used to study the effects of conditions such as sleep-disordered breathing or surgery on cognition and cortical anatomy [24,25].

2.2 Subject selection - drug groups

For all ADNI participants, prescription and over-the-counter medications taken in the previous three months were entered in the “Concurrent Medications Log” at the screening visit. The medication log was updated at each study visit at 6, 12, and 24 months. Subjects for our study were selected by searching the “Concurrent Medications Log” for analgesic medications (e.g., NSAID, acetaminophen, opioids, gabapentinoids, etc.) and indications (e.g., arthritis, joint pain, headaches, neuropathy, back pain, etc.). NSAIDs included the following: celecoxib, diclofenac, etodolac, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, salsalate, and trisalicylate. Note that subjects were excluded from ADNI if opioids were used regularly, defined as greater than two doses per week, within four weeks of screening. Subjects were also excluded from ADNI if certain antidepressants, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines were used within four weeks prior to screening.

To track the effects of analgesics over time, subjects were included if the particular analgesic medication was listed on the medication log prior to enrollment in ADNI and throughout the study at each study visit and the indication was a painful condition. Control subjects were not flagged for any key words. Subjects were excluded if analgesic medication use started or stopped after initial enrollment. Subjects were excluded if comment fields indicated any acute pain condition (e.g. surgery, postoperative, fracture, etc.).

We examined the effect of NSAIDs against two different comparators. In the primary grouping, we compared subjects taking NSAIDs to control subjects taking no analgesics. We also performed some secondary analysis comparing subjects taking NSAIDs with those taking other analgesics not from the NSAID group. There were 87 NSAID positive subjects, 373 controls and 71 taking other analgesics. The primary hypothesis is that NSAID users are different than controls.

2.3 Neuropsychological assessment and analysis

Cognitively normal (NL), MCI and AD were defined in ADNI as follows: Normal subjects have Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of 23-30 (mean 29.07 ±1.24, SD) and clinical dementia rating (CDR) of 0. MCI participants have reported a subjective memory concern either autonomously or via an informant or clinician and have objective memory loss measured by Wechsler Memory Scale Logical Memory II. MCI subjects have MMSE scores of 21-30 (mean 27.83 ± 1.92 SD) and CDR of 0.5. However, there are no significant levels of impairment in other cognitive domains, essentially preserved activities of daily living and no signs of dementia. AD participants have been evaluated and meet the NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD with MMSE of 7-26 (mean 20.31 +4.70).

All subjects underwent neuropsychological assessment at baseline, 6,12, and 24 months. A composite score for executive function, ADNI-EF, has been developed and validated by a group of ADNI investigators. Components of ADNI-EF are as follows: category fluency - animals and vegetables, measures of semantic memory; trail making test parts A and B, tests of visual/motor skills and cognitive flexibility; digit span backwards, a measure of working memory; Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised Digit Symbol, a measure of information processing speed; and Clock Drawing Test, a measure of memory and concentration [26]. Several of the ADNI authors reviewed the neuropsychological battery to identify items which could be considered indicators of EF. They refined item selection using an iterative process in which they constructed a model using confirmatory factor analysis, reviewed findings as a small group, and then constructed a revised model. Criteria for model fit were the confirmatory fit index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), where criteria for excellent fit included: CFI>0.95, TLI>0.95, and RMSEA<0.051. A composite score for memory, ADNI-MEM, has also been developed and validated in ADNI participants using data from the ADNI neuropsychological battery based on modern psychometric methods. The formation of ADNI-MEM included the Rey Auditory Verbal LearningTest, the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive, and the Logical Memory I data [27].

2.4 Anatomical changes

Brain cortical volumes, cortical thickness and cortical surface areas were examined for particular regions of interest (ROI) as reported in ADNI, so we could examine their dependence as a function of NSAID use. To amplify the signal from these many measurements of small ROIs (there were 327 total MRI derived variables) we devised a way to combine them. We used the 42 ROIs identified from this same ADNI database by Risacher, who selected them as the most effective at predicting the progression from MCI to AD [28,29]. We then compressed them into five eigenvectors (EVs) using principal component analysis (PCA). These EVs are linear combinations of the ROI’s. Each ROI has its own dynamic during ageing, dementia and treatment with NSAIDS. The EVs have the additional property of being orthogonal (or perpendicular) to each other, thus eliminating collinearity. The five EVs were picked from an SPSS derived Scree plot using a standard assumption that all examined EVs are greater than 1.0. SPSS calculates EV values for each subject.

2.5 Stability and transitions between cognitive diagnoses

Due to the scheduling of the cognitive tests at specific times post enrollment, these values were clustered. Since the cognitive diagnosis (NL, MCI, AD), updated at each visit, depended on the cognitive performance, the transitions between less severe and more severe diagnoses tended to also be clustered timewise. To analyse the stability of a subject, we examined whether the subject transitioned to a more severe diagnosis within a particular time frame. Due to the much greater number of MCI subjects than NL subjects, we took as our primary transition the progression from MCI to AD, and thus only analysed subjects who were MCI at baseline. Since the visits between baseline and 2 years were examined in the cognitive analysis, we made the stability transition boundary 2.25 years, fitting in with the second cluster. Thus stable subjects were those preserving their MCI diagnosis through the last determination between 1.25 and 2.25 years. Unstable subjects were defined as transitioning to AD by 2.25 years.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The primary analysis was to determine the impact on ADNI- EF and ADNI-MEM of NSAID use as a function of diagnosis (NL, MCI, AD), elapsed time in the study, age, and gender. Descriptive statistics and graphical analysis (bar graphs with 95% confidence intervals) were used to demonstrate changes in cognitive performance with time, progression of dementia (diagnosis), gender, cortical structure and drug group. Univariate analysis was used to describe the dependence of executive function or memory (at baseline) on the covariates age and cortical structure and the cofactors diagnosis, gender, and drug group. To examine the effect of time as a function of visit, we used repeated measures ANOVA (with visits at baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months). Since the data was not generated in an experimental protocol controlled to analyse the effects of NSAIDs, we used several different statistical methods as a form of check on our results: (1) we used univariate analysis to examine the dependence of EV#1 on the NSAID groups while controlling for diagnosis, gender and age; (2) we selected EV#1 as the most important amongst the set of EVs subjecting all 5 EVs to multivariate and graphical analysis (the EVs were the dependent variables, and both cognitive variables at baseline (ADNI-EF and ADNI-MEM) along with age and gender were the independent variables); (3) to confirm possible relationships between cognitive variables and EVs, we ran a correlation which included both cognitive variables taken at all 4 visits and all 5 EVs; we did not assume any particular distribution for the variables (Spearman’s Rho rank correlation used); (4) from a clinical point of view, the most important prediction would be of the 24 month cognitive variables, ADNI-EF and ADNI-MEM; we used linear regression analysis to see which of the independent variables, including cortical EV’s, age, gender, baseline cognitive performance and diagnosis were most useful in predicting the cognitive outcomes; (5) one might assume that if we could predict cognitive outcomes based on various parameters including NSAID use, there would be a relationship between progression of dementia as diagnostic stability, EV#1, and NSAID use. We used repeated measures to examine this at two different time points (baseline and 6 months). This analysis used only subjects who were MCI at baseline, since stability was assessed as propensity to progress from MCI to AD.

These various analyses were used as checks on each other so as to confirm the relationships between NSAID use, cognitive performance, cortical dimensions and diagnostic stability. Since there is redundancy in our analysis, we limit the graphs to the most important findings, and summarize only the most important aspects of other analysis. Data analysis was done with SPSS (Version 24, Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was defined as p values ≤ 0.05. F values were given for the primary statistical tests in each figure.

Potential uneven distributions can be examined using chi- square or Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel analysis and compensated for using diagnosis and/or gender as cofactors, or we can examine NL and MCI subjects separately.

Not all ADNI sites performed all the measurements. However, when a particular type of study was performed, all the specific measurements within it were generally acquired. In any case, we did not impute missing data, with the exception of those calculations resident in the SPSS programmes. SPSS in general uses listwise deletion and so no data imputation. We were able to deal with the missing data problem by using different types of analyses which then used different combinations of variables, reducing the exclusion of available data. One must always assume with a dementia cohort that there is a systematic error relating missing data to dementia severity, such that we also used at times the cohort including NL and MCI but excluding AD. Thus patients with dementia can forget appointments or not follow instructions.

3 Results

3.1 Demographics

The original ADNI study was designed to look at MCI and transitions to AD, so MCI is the most heavily populated of the diagnoses. There was no preferential recruitment by gender (male, n = 477; female, n = 342). The prevalences of diagnoses (NL, MCI and AD) were as follows: 229, 397, and 193, respectively. For the cohort comparing NSAID use to no analgesic use, there were 87 subjects that used NSAIDS for the duration of enrollment in ADNI. There were 373 control subjects that did not use any analgesics (Table 1). Additional demographic information is listed in Table 2.

Distribution of cognitive diagnoses and gender.

| Diagnosis | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| NL | MCI | AD | |||

| Male | 45 | 117 | 62 | 224 | |

| Control | Female | 36 | 57 | 56 | 149 |

| Total | 81 | 174 | 118 | 373 | |

| Male | 11 | 28 | 7 | 46 | |

| NSAID+ | Female | 12 | 21 | 6 | 41 |

| Total | 25 | 49 | 13 | 87 | |

Baseline patient demographics.

| Total | Control | NSAID+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Age (mean + SD) | 75.10 + 7.18 | 75.08+7.25 | 75.20+6.94 |

| % female | 41.3 | 39.9 | 47.1 |

| Cardiac disease (%) | 73.6 | 73.1 | 75.8 |

| Renal disease (%) | 45.9 | 42.3 | 60.9 |

| Respiratory disease (%) | 21.5 | 19.5 | 29.9 |

Fewer subject with AD diagnosis used NSAIDs than do subjects with NL and MCI diagnosis; this disparity is larger for females. Ignoring AD subjects so there remained a two factor drug group (NSAID use vs none) and two factor cognitive diagnosis, we obtained a random distribution of drug group over diagnosis (p = 0.521). Age was evenly distributed by gender (male, 75.87 years; female, 74.73 years; p = 0.063).

From the medical conditions examined, it appears that overall, the NSAID subjects were sicker, as much as the differences in renal and respiratory (but not cardiac) disease were significant

3.2 Neuropsychological tests

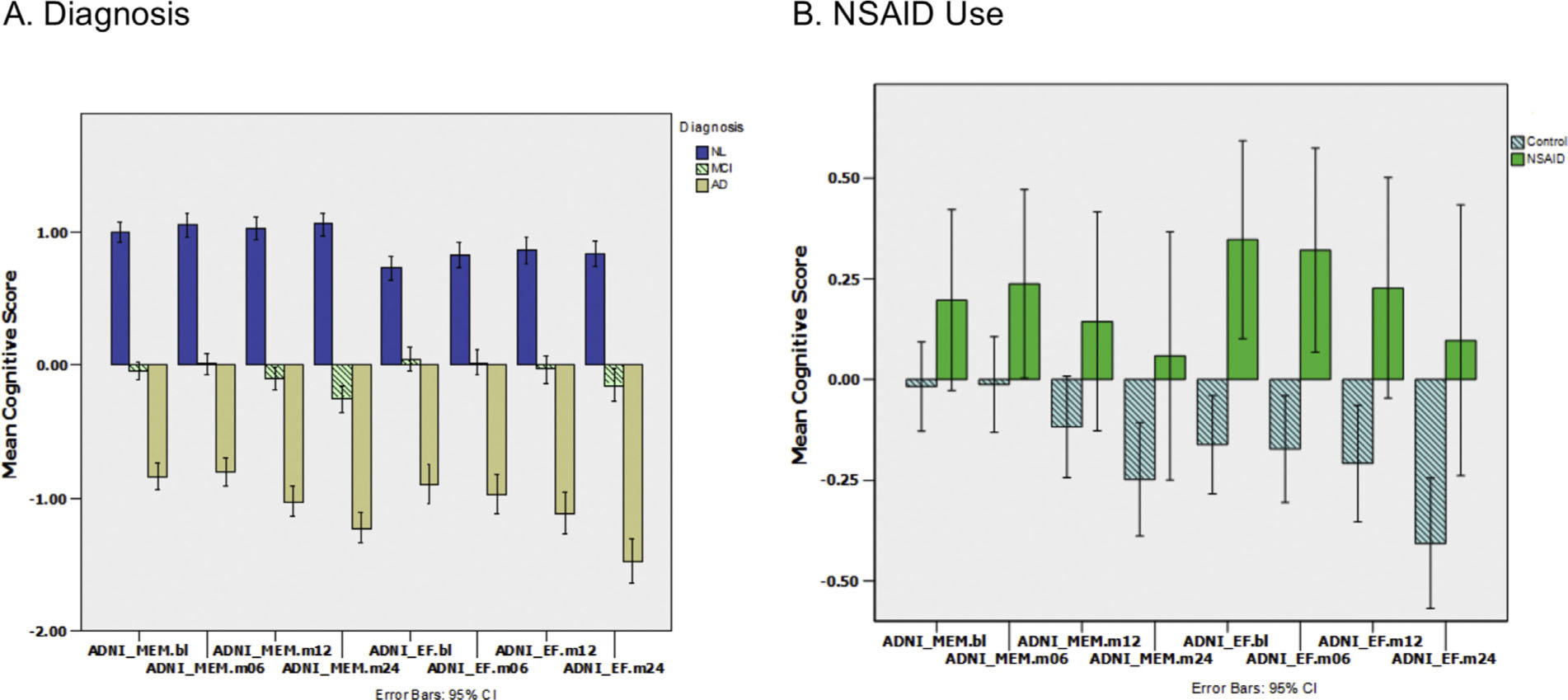

Composite scores over four visits (baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months) are displayed as a function of cognitive diagnosis (Fig. 1a). As expected, and based on 95% confidence intervals, NL subjects had higher ADNI-MEM scores at baseline than MCI subjects, and MCI subjects had higher scores than AD. Likewise ADNI-EF scores fell with increased cognitive impairment. This graph shows that cognitive scores are readily distinguished as a function of diagnosis (as confirmed by ANOVA in Figs. 2 and 3).

Memory and executive function scores stratified by diagnosis and NSAID Use. (A) ADNI-MEM for 4 visits (baseline, 6,12, 24 mos) on left followed by ADNI-EF on right for each cognitive diagnosis: NL, MCI, AD. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. There are significant differences between diagnoses in many cases. EF and MEM scores of AD patients decrease monotonically over time, with a slight decrease for MCI. NL subjects show slight improvement consistent with rehearsal effects. (B) MEM and EF for NSAID use. Subjects using NSAIDs show numerically larger mean values versus controls with no overlapping confidence intervals for the EF scores. MEM = memory; EF = executive function; NL = cognitively normal; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Executive function by visit, diagnosis and NSAID use. ADNI-EF over 4 visits for (A) NL, (B) MCI, and (C) AD subjects using repeated measures ANOVA and comparing NSAID use (dashed line) against control (no analgesics; solid line). EF was dependent on the following independent variables: age (p = 0.017; F = 15.9); diagnosis (p = 0.000; F = 66.3); and, NSAID use (p = 0.019; F = 15.4) for between subject comparisons. Gender was not significant (p = 0.498). NSAID positive subjects had highest EF. The best separation by NSAID use is for (A) NL subjects, which is on its own significant (p = 0.037) in a similar repeated measures ANOVA. Significant interactions included: age * visit (p = 0.011), diagnosis * visit (p <0.001), and gender* visit (p = 0.015). EF = executive function; NL = cognitively normal; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

ADNI-MEM over 4 visits for NL females by NSAID use. NSAID users were compared to controls on no analgesics. Only females are shown since gender was a significant variable (males had non-significant differences). NSAID use was significant only for the last 2 visits analysed together, but not as a 4 point repeated measures ANOVA. MEM = memory; NL = cognitively normal; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

We hypothesized that NSAID use would alter ADNI-EF and ADNI-MEM scores. Before correcting for the multiple cofactors and covariates (age, gender, diagnosis, visit) with ANOVA we examined whether NSAID use resulted in noticeable differences in cognitive test results using descriptive statistics as above in response to diagnosis. We compared subjects taking NSAIDs versus subjects on no analgesics (Fig. 1b). ADNI-EF at all 4 visits had higher means, with no overlap of 95% CI, for subjects taking NSAIDs than for those without. There is a similar trend for ADNI-MEM scores with the means always being larger for NSAID positive subjects but an equivocal distribution of confidence intervals. We then performed analyses adjusting for cofactors and covariates (see Sections 3.3 and 3.4).

3.3 Executive function factors

Examining all three drug groups (NSAID use vs other analgesic use vs no analgesic use) over all diagnoses, genders, and age, we rejected the null hypothesis that all groups had equal executive function scores (p = 0.035). For all NL and MCI subjects, those taking NSAIDs had higher scores for EF tests over time (baseline to 2 years), compared to analgesic free subjects serving as control (Fig. 2). Using this grouping as the cofactor against ADNI-EF, subjects on NSAIDs had significantly higher EF scores (p = 0.019; F = 15.4) compared to controls including cohorts of all three cognitive diagnoses in a repeated measures ANOVA with visit (baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months) serving as the repeated factor.

When comparing all subjects taking NSAIDs versus subjects using analgesics other than NSAIDs, there were no significant differences in EF scores (p = 0.622).

When examining NL subjects alone using repeated measures ANOVA, ADNI-EF scores were significantly higher for those using NSAIDs compared to those using other analgesics (p = 0.011) and those using no analgesics (p = 0.037). Both age (p = 0.663) and gender (p = 0.414) were non-significant. There were no significant differences for MCI and AD subjects examined alone.

3.4 Memory factors

Replacing ADNI-EF with ADNI-MEM in the analysis above, neither drug group was significant (NSAID vs other analgesics, p = 0.766; NSAID vs control (no analgesics), p = 0.383), nor was gender (p > 0.27). However cognitive diagnosis was significant (p < 0.001). We then focused on NL subjects, where gender is now significant for both drug groups (p = 0.022, p = 0.003, respectively). For NL subjects, examining by gender, females have more apparent response to NSAIDs in their MEM scores than males. However, even among NL females, drug group is still not significant for either drug group comparison (p = 0.093; p = 0.590, respectively). In Fig. 3, we plot the NL female subjects, comparing NSAIDS versus controls.

As seen in Fig. 3, there is a time dependent increase in the mean value of MEM associated with NSAID use. At the last two visits there are significant differences in MEM between NSAID users versus other analgesic users or versus controls (p = 0.003, p = 0.042, respectively) but not at initial time points. This suggests that for NL females, those using NSAIDs had higher MEM scores than those not taking NSAIDs at 12 and 24 months. Examining all three drug groups together, we were able to reject the null hypothesis that all groups had equal memory scores (p = 0.049; F = 4.43) in the restricted cohort (female NL) used for the analysis just above. Age was not significant in these analyses (p > 0.5).

Repeating the analysis with males only and for both genders together does not result in a significant effect for NSAID use.

3.5 Structural MRI

3.5.1 Compression to EV set with dependence on diagnosis and drug group

To examine the role of structure during cognitive change, we examined cortical measurements that have been previously identified as predicting AD progression, i.e. ROIs that experience grey matter atrophy (or fluid space expansion) during dementia. This group (n = 41) of ROI measurements from ADNI, already identified as predicting progression, were further compressed into fewer components, namely 5 EVs, using PCA [28,29].

For a descriptive examination of the effect of diagnosis on these EVs, see Fig. 4a. We plotted the five cortical EVs derived from baseline MRI data along the left horizontal axis and the EVs similarly derived from the 6 month MRI measurements on the right. In particular, two EVs, EV#1 and EV#3, were clearly responsive to changes in cognitive diagnoses, as indicated by the bar graphs and confidence intervals. Namely, the NLs had the largest positive values, the AD subjects the largest negative values, and the MCI values were near the axis origin.

As we hypothesized that NSAID use had a positive association with structure (i.e. reducing atrophy), NL and MCI subjects were then plotted as a function of NSAID use versus control (see Fig. 4b).

Display ofbaseline and 6 month eigenvectors. (A) Five EVs derived from multiple cortical ROIs using PCA. Each vector is split by diagnosis. (B) Each vector is split by the NSAID group. Note that EV#1 and #3 vary significantly by cognitive diagnosis. Right panel (B) shows that EV#1, readily split by diagnosis, is also significantly different between those using NSAIDs compared to control. EV = eigenvector; ROI = region of interest; PCA = principal component analysis; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. This most prominent vector (EV#1) represents many temporal lobe and other regions including: left (LF) and right (RT) precuneous cortical thickness (CT); LF & RT fusiformgyrusCT; LF&RT inferior (INF) parietal CT; LF&RTINFtemporalCT; LF&RT middletemporalCT; supramarginalgyrusCT; LF&RT superiortemporalCT.The second most prominent vector (EV#3) includes: LF & RT inferior lateral (lat) ventricle (vent), LF & RT lat vent, and CT of RT entorhinal cortex. EV#2 includes: LF & RT superior (sup) parietal CT, RT ventral dorsal column volume (vol), LF&RT cerebralgrey matter cortical volume (CV), LF&RT cerebral cortical white mattervol. EV#4 includes: LFaccumbens CV, RT ventral dorsal column vol, LF & RT amygdala vol, LF & RT hippocampal vol, RT entorhinal CT. EV #5 includes multiple components of cingulate gyrus: LF & RT rostral anterior, LF & RT caudal anterior, and LF posterior cingulate gyrus.

One of the two EVs responsive to diagnosis, EV#1, had a significant response to drug group, indicating that these subjects taking NSAIDs had larger EV#1 values than control subjects.

3.5.2 Univariate analysis of EV#1 as a surrogate for structure

More detailed analysis of Fig. 4b results supports these conclusions. Specifically in a univariate analysis with EV#1 at baseline as the dependent variable and diagnosis, drug group, age, and gender as the cofactors/covariables, diagnosis (p < 0.001; F = 18.5), age (p < 0.001; F = 15.1) and NSAID use (p = 0.006; F = 7.1) were significant, but gender was not (p = 0.208), indicating those with better cognitive diagnosis, younger age and NSAID use had larger EV#1 values (Fig. 5a). This particular EV, EV#1, represented many temporal lobe regions (bilateral inferior, superior and middle) as well as other regions including precuneous, fusiform gyrus, and supramarginal gyrus (see caption).

Effect of NSAID use on EV#1 as function of diagnosis and time. The left panel (A) shows plots by NSAID use and diagnoses with EV#1 values on the vertical axis. (B) This analysis was repeated at 6 months with the same basic result. We used repeated measures analysis with EV#1 being the dependent variable. Examining the data over two visits gave us similar results with combined significance overtime. Significance values are assessed in text. NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; EV = eigenvector; NL = cognitively normal; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

To test the effect of time, we repeated the same statistical analysis at 6 months rather than baseline. This required recalculating the linear components of EV#1. Diagnosis (p < 0.001) and NSAID use (p = 0.003) were again significant. Combining these two analyses at baseline and at 6 months in a repeated measures analysis with visit repeating, diagnosis (p < 0.001) and NSAID use (p = 0.002; F = 16.8) remained significant cofactors, but there was no significant change in EV#1 overtime (Factor(visit); p > 0.5). Thus EV#1 was dependent on NSAID use at both baseline and 6 months and using the pooled data but did not in itself show a significant change with time.

3.5.3 Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis was used to examine what variables (cofactors/covariates) might correlate with changes in specific cortical areas, i.e. specific EVs. In this analysis, the 5 EVs from the baseline EV basis set were the dependent variables against the following independent variables at baseline: ADNI-EF, ADNI-MEM, age, diagnosis, and gender. ADNI-EF, ADNI-MEM, age, and gender were all highly significant (p < 0.001) against the set of EVs as a group. This analysis also confirmed other findings in this study: ADNI-MEM was a significant factor in predicting EV#3 (p < 0.001; with no significance for other EVs); and gender was significant for EV#3 (p < 0.001), but not for EV#1 (p = 0.14; see Figs. 2 and 3).

3.5.4 Correlation between cognitive scores and EVs

Using rank dependent correlation (Spearman’s Rho), we examined ADNI-EF and ADNI-MEM against all 5 EVs. We found that EV#1, this same EV showing significant differences with NSAID use, had the best correlation with EF at all 4 visit times (corr coef> 0.296; p < 0.001), while EV#3 had the best correlation with ADNI-MEM (corr coef> 0.364; p < 0.001). This is shown graphically in Fig. 6 where we plot EF at 24 months versus EV#1 at 6 months.

Executive function versus eigenvector 1. ADNI-EF at 24 months correlated in a scatter plot with the 6 month values for EV#1. The dashed line is a linear fit (R2 = 0.264) while the solid lines show the width of the 95% confidence interval. EF = executive function; EV = eigenvector.

Based on these relationships, we tested whether cognitive results could be predicted with linear regression using baseline cognitive scores, anatomy and NSAID use. Certainly for EF, this is possible without additional restrictions. For example prediction of ADNI-EF at 24 months can be accomplished using baseline EF and MEM and EV#1 (p < 0.001), as well as s NSAID group (p = 0.032). Higher baseline EF and MEM scores as well as larger EV#1 values and the use of NSAIDs (compared to no use) were the best predictors of higher ADNI-EF at 24 months.

3.5.5 Do NSAID group, and risk of transition from MCI to AD (diagnostic stability) affect structural EV#1 values?

Since NSAID was associated with higher cognitive scores in some subjects and accompanied enhanced cortical volume, we hypothesized that NSAID use would decrease risk of transition to full Alzheimer’s, since this transition generally occurs as cognitive loss and cumulative atrophy approach a threshold. The transition from MCI to AD was better populated than NL to MCI, so that transition was examined. Only subjects who were MCI at baseline are included in this analysis. Stable subjects were those preserving an MCI diagnosis through the last determination between 1.25 and 2.25 years. Unstable subjects were any transitioning to AD by 2.25 years. EV#1 was examined first at baseline (Fig. 7) and tested against two cofactors: diagnostic stability and NSAID use.

Dependence of eigenvector #1 on diagnostic stability and NSAID use. Examination of the relationship between baseline EV#1 (y-axis) NSAID use (x-axis) and stability. The stability factor describes whether the subject transitioned to a more severe diagnosis (1 - stable, blue; 2 - unstable, transitioned from MCI to AD, green). Both cofactors, NSAID use and stability, are significant independent variables of dependent variable EV#1. Similar results are seen for 6 month EV#1 data. Since the MCI to AD transition is the best populated and thus the one we examined, all subjects represented in this figure were MCI at baseline. Significance levels are indicated in text. EV = eigenvector; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; MCI = miId cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

The choice of EV#1 was confirmed from a new multivariate analysis, first testing all 5 EVs against the NSAID and stability groups in this new population, where the multivariate tests gave significance for NSAID (p = 0.026) and stability groups (p = 0.005). Then, looking at individual EVs, we find the highest significance level for EV#1 versus both NSAID group and stability (p = 0.009, F = 7.1; p = 0.005, F = 8.1, respectively; Fig. 7). We then examined EV#1 at 6 months where it was again significant against NSAID group and stability (p = 0.001, p = 0.008, respectively). Combining the baseline and 6 month values for EV#1 in a repeat measures analysis against drug group and stability also showed significance (p = 0.003, p = 0.025, respectively; confirmed with multivariate analysis). In this analysis, age was significant (p < 0.001), but gender was not (p > 0.5). Although NSAID group and transition risk binaries were successful in estimating cortical dimensions, NSAID group was not successful in predicting the risk directly using logistic regression.

4 Discussion

In this study, we used the longitudinal ADNI database to examine the interaction of cognitive status and pain medication, specifically NSAIDs, on cognitive function and structural brain changes. We found that NSAID use was associated with higher ADNI-EF scores for NL and MCI subjects as well as higher ADNI-MEM scores for NL female subjects. There was also an association between NSAID use and larger cortical volumes for specific cortical regions, which we identified using PCA to form five groups of ROIs. These same subjects using NSAIDS and with increased cortical volume had a decreased risk of transitioning from MCI to AD.

The analysis primarily compared NSAID users with controls who putatively took neither NSAIDs nor other analgesics. We performed an additional analysis comparing those who took NSAIDS with those prescribed other analgesics. This latter group was smaller and consisted of several medication types so failure to reach significance cannot be relied on as rejecting the test. However, we were able to draw a few conclusions about the group taking other analgesics. There was no consistent response of EF over all diagnoses in this group compared to control as there was with the NSAID group. The repeat measure analysis in Fig. 2 was not significant for other analgesic users versus either NSAIDS or control groups. In terms of MEM where NSAID users had higher scores than analgesic free controls (female NL), the group using other analgesics had worse scores than controls such that the difference between NSAID users and other analgesic users was more significant than between NSAID users and analgesic free controls.

The effect of other analgesics had limited analysis due to exclusion criteria in the original ADNI protocol and to low numbers in this dataset. Further studies are needed to examine the role of analgesics such as opioids on cognition and the interplay that analgesics and inadequate versus adequate pain control play in cognition.

We found that NSAID use was associated with higher ADNI-EF scores, as well as larger cortical volume for many regions, especially those regions associated with cognitive diagnosis, as shown in this same study. NSAID users had significantly higher ADNI-EF scores at baseline and over time. NL NSAID users had significantly higher ADNI-MEM scores for particular combinations of visit number (later) and gender (female). The effects on ADNI-MEM are restricted to a smaller subset of subjects and a different subset of cortical regions.

Our findings are consistent with studies that have found NSAIDs have a protective effect against cognitive decline, showing more specifically that NSAID use may be more broadly associated with executive function than memory [15,16,17,18,19]. It is possible also that there is more of a gender effect with impact on memory or that memory is a more difficult function to quantify. Further prospective studies are needed to examine this gender effect on memory scores.

We have confirmed and reproduced data supporting well known relationships between cognitive diagnoses (NL, MCI, or AD) and memory or executive function. In a sample of elderly subjects from the ADNI database, we have also shown a dependence of memory and executive function on age and complex dependence on gender. Furthermore, we have found expected trends such that cognitive function slightly increases over time (2 years) in NL subjects, perhaps due to rehearsal effects; that it declines slowly over time in MCI subjects, most likely due to progression of illness; and, that it declines dramatically in severe dementia subjects (AD) as rate of cortical atrophy increases.

To explore the importance of anatomical change during NSAID use, we employed linear regression analysis to model the executive function and memory performance over 2 years. The 12 and 24 month cognitive performance was predictable from independent variables: baseline cognitive performance, drug group, and the two anatomical EVs, EV#1 and EV#3. These two EVs have been shown to relate to cognitive performance using both correlation and multivariate analysis. Since these EVs themselves vary with NSAID use, we hypothesize that NSAIDs may act on cognition by improving cortical structure - i.e. slowing atrophy. This is consistent with other studies showing NSAIDs may protect against age-related changes in grey matter volume [30,31]. (In a currently unpublished study using Random Forest machine learning techniques, this same eigenvector (#1) was repeatedly selected as a significant feature in predicting transition from MCI to AD - Kline, Shasha, Beltran.)

Based on the well-known occurrence of cortical atrophy during the progression through advanced Alzheimer’s, one might think that NSAIDs, by correlating with larger cortical volume, would lower the risk of transition from MCI to AD, or slow the occurrence of MCI in NL subjects. The final figure suggests that the most stable MCI patients are those that are noted to be NSAID users and have the largest values for EV #1.

Limitations of this study include secondary analysis of existing data and the possibility of confounding. In classifying subjects, it was not possible to ascertain whether subjects with NSAIDs listed on the medication list were using them chronically or occasionally, coinciding with each of the study visits. We classified subjects as NSAID users if NSAIDs were listed on the medication list at every visit and if the indication was a painful condition. Caution must be used when averaging cognitive performance over subjects with different drug exposure. We saw in this study that subjects with the most cognitive impairment had the least NSAID use; AD subjects have the least NSAID use (non-random by chi square analysis, p = 0.000) for the three cognitive diagnoses. This non-random distribution is avoided when only looking at NL and MCI (chi square, p = 0.571). There is potential bias due to the dependence of subject participation on diagnoses. Both dementias and pain symptoms affect participation as follows: demented subjects are more likely to forget an appointment or not process the nature of their obligation. Pain subjects may be incapacitated or not inclined to participate on a particular day due to their symptoms. They may also attempt to use study participation to acquire medications beyond the doses required by good practice.

5 Summary

The non-uniform impact of drugs on cognition, affecting patients differently as a function of diagnosis, gender and type of cognitive function (executive function versus memory) sheds some light on why it is difficult to test drug impact on cognition using a few simple cognitive tests or a random subject pool without careful attention to assessment of baseline diagnosis, age, and gender, as well as brain regions affected. Since there are numerous medications used to treat pain which may have differing impact on the brain, it may become increasingly important in the future to consider the secondary effects when choosing a regimen of pain treatment.

Highlights

Data from Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative was used to study NSAIDs.

NSAID users had higher executive function scores than controls.

NSAID use was associated with higher memory scores in cognitively normal females.

In specific cortical regions, NSAID users had larger cortical dimensions.

Executive function scores correlated with cortical dimensions.

Abbreviations

- ADNI

-

Alzheimer’s Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- NL

-

cognitively normal

- MCI

-

mild cognitive impairment

- ADNI-EF

-

composite score for executive function

- ADNI-MEM

-

composite score for memory

- EV

-

eigenvector

- CDR

-

clinical dementia rating

- CFI

-

confirmatory fit index

- TLI

-

Tucker Lewis Index

- RMSEA

-

root mean squared error of approximation

- PCA

-

principal component analysis.

-

Contributions: Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data, but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/howto_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

-

Funding: Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumos- ity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

-

Ethical issues: The collection of data by ADNI was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

The New York University Medical Center Institutional Review Board takes the position that anonymous data from another institution (as in this case) is “not human subjects research.”

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Thomas Blanck for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Anaesthesia Research Fund of the NYU Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Care, and Pain Medicine.

References

[1] Nawai A, Leveille SG, Shmerling RH, Leeuw G, van der Bean JF. Pain severity and pharmacologic pain management among community-living older adults: the MOBILIZE Boston study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2017:1-9, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40520-016-0700-9.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Sawyer P, Bodner EV, Ritchie CS, Allman RM. Pain and pain medication use in community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006;4:316–24, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Hunt LJ, Covinsky KE, Yaffe K, Stephens CE, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Pain in community-dwelling older adults with dementia: results from the national health and aging trends study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:1503–11, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13536.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Barry HE, Parsons C, Passmore AP, Hughes CM. Exploring the prevalence of and factors associated with pain: a cross-sectional study of community-dwelling people with dementia. Health Soc Care Commun 2016;24:270–82, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12204.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Fine PG. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older patients. Clin J Pain 2004;20:220–6.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Boers M, Tangelder MJD, van Ingen H, Fort JG, Goldstein JL. The rate of NSAID-induced endoscopic ulcers increases linearly but not exponentially with age: a pooled analysis of 12 randomised trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:417–8, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.2006.055012.Search in Google Scholar

[7] American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1331–46, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x.Search in Google Scholar

[8] O’Neil CK, Hanlon JT, Marcum ZA. Adverse effects of analgesics commonly used by older adults with osteoarthritis: focus on non-opioid and opioid analgesics. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2012;10:331–42, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016Zj.amjopharm.2012.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Sjøgren P, Christrup LL, Petersen MA, Højsted J. Neuropsychological assessment of chronic non-malignant pain patients treated in a multidisciplinary pain centre. EurJ Pain 2005;9:453, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.10.005.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kamboj SK, Tookman A, Jones L, Curran VH. The effects of immediate-release morphine on cognitive functioning in patients receiving chronic opioid therapy in palliative care. Pain 2005;117:388–95, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.022.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Puustinen J, Nurminen J, Löppönen M, Vahlberg T, Isoaho R, Räihä I, Kivela SL. Use of CNS medications and cognitive decline in the aged: a longitudinal population-based study. BMC Geriatr 2011;11:70, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-11-70.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Tassain V, Attal N, Fletcher D, Brasseur L, Degieux P, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D. Long term effects of oral sustained release morphine on neuropsychological performance in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Pain 2003;104:389–400, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00047-2.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Jamison RN, Schein JR, Vallow S, Ascher S, Vorsanger GJ, Katz NP. Neuropsychological effects of long-term opioid use in chronic pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 2003;26:913–21, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00310-5.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Kamboj SK, Conroy L, Tookman A, Carroll E, Jones L, Curran HV. Effects of immediate-release opioid on memory functioning: a randomized-controlled study in patients receiving sustained-release opioids. Eur J Pain 2014;18:1376–84, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2014.498.x.Search in Google Scholar

[15] in ‘t Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A, Launer LJ, van Duijn CM, Stijnen T, Breteler MM, Stricker BH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1515–21, http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa010178.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yip AG, Green RC, Huyck M, Cupples LA, Farrer LA, MIRAGE Study Group. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and Alzheimer’s disease risk: the MIRAGE Study. BMC Geriatr 2005;5:2, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-5-2.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Szekely CA, Breitner JCS, Fitzpatrick AL, Rea TD, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Zandi PP. NSAID use and dementia risk in the Cardiovascular Health Study: role of APOE and NSAID type. Neurology 2008;70:17–24, http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000284596.95156.48.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Hayden KM, Zandi PP, Khachaturian AS, Szekely CA, Fotuhi M, Norton MC, Tschanz JT, Pieper CF, Corcoran C, Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Cache County Investigators.Does NSAID use modify cognitive trajectories in the elderly? The Cache County Study. Neurology 2007;69:275–82, http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000265223.25679.2a.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Waldstein SR, Wendell CR, Seliger SL, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ, Zonderman AB. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, and cognitive function in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:38–43, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02618.x.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial Research Group. Results of a follow-up study to the randomized Alzheimer’s Disease Antiinflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT). Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:714–23, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/jjalz.2012.11.012.Search in Google Scholar

[21] ADAPT-FS Research Group.Follow-up evaluation of cognitive function in the randomized Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial and its follow-up study. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:216–25.e1, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/jjalz.2014.03.009.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Vlad SC, Miller DR, Kowall NW, Felson DT. Protective effects of NSAIDs on the development of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2008;70:1672–7, http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000311269.57716.63.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Heneka MT, Carson MJ, Khoury JE, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, Jacobs AH, Wyss-Coray T, Vitorica J, Ransohoff RM, Herrup K, Frautschy SA, Finsen B, Brown GC, Verkhratsky A, Yamanaka K, Koistinaho J, Latz E, Halle A, Petzold GC, Town T, Morgan D, Shinohara ML, Perry VH, Holmes C, Bazan NG, Brooks DJ, Hunot S, Joseph B, Deigendesch N, Garaschuk O, Boddeke E, Dinarello CA, Breitner JC, Cole GM, Golenbock DT, Kummer MP. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:388–405, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kline RP, Pirraglia E, Cheng H, Santi SD, Li Y, Haile M, de Leon MJ, Bekker A, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.Surgery and brain atrophy in cognitively normal elderly subjects and subjects diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. J Am Soc Anesthesiol 2012;116:603–12, http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318246ec0b.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Osorio RS, Gumb T, Pirraglia E, Varga AW, Lu S, Lim J, Wohlleber ME, Ducca EL, Koushyk V, Glodzik L, Mosconi L, Ayappa I, Rapoport DM, de Leon MJ, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.Sleep-disordered breathing advances cognitive decline in the elderly. Neurology 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001566.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Gibbons LE, Carle AC, Mackin RS, Harvey D, Mukherjee S, Insel P, Curtis SM, Mungas D, Crane OK, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. A composite score for executive functioning, validated in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) participants with baseline mild cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav 2012;6:517–27, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11682-012-9176-1.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Crane PK, Carle A, Gibbons LE, Insel P, Mackin RS, Gross A, Jones RN, Mukherjee S, Curtis SM, Harvey D, Weiner M, Mungas D, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.Development and assessment of a composite score for memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Brain Imaging Behav 2012;6:502–16, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11682-012-9186-z.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Risacher S, Saykin A, Wes J, Shen L, Firpi H, McDonald B. Baseline MRI predictors of conversion from MCI to probable AD in the ADNI cohort. Curr Alzheimer Res 2009;6:347–61, http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/156720509788929273.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Risacher SL, Shen L, West JD, Kim S, McDonald BC, Beckett LA, Harvey DJ, Jack Jr CR, Weiner MW, Saykin AJ, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Longitudinal MRI atrophy biomarkers: relationship to conversion in the ADNI cohort. Neurobiol Aging 2010;31:1401–18, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016Zj.neurobiolaging.2010.04.029.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Walther K, Bendlin BB, Glisky EL, Trouard TP, Lisse JR, Posever JO, Ryan L. Anti-inflammatory drugs reduce age-related decreases in brain volume in cognitively normal older adults. Neurobiol Aging 2011;32:497–505, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.03.006.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Bendlin BB, Newman LM, Ries ML, Puglielli L, Carlsson CM, Sager MA, Rowley HA, Gallagher CL, Willette AA, Alexander AL, Asthana S, Johnson SC. NSAIDs may protect against age-related brain atrophy. Front Aging Neurosci 2010:2, http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2010.00035.Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia

Articles in the same Issue

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia