Abstract

The diverse cellular functions of nucleic acids are made possible by enzymes that catalyze cleavage of glycosidic (nucleobase–sugar) and phosphodiester bonds. Despite advancements in experimental biochemical methods, critical information about such enzyme-catalyzed reactions is difficult to obtain from traditional experiments. However, computational quantum mechanical (QM) methods can provide atomic level details of catalytic pathways that are complementary to experimental data. This perspective highlights various QM techniques used to advance our understanding of enzymes that process nucleic acids. First, select DNA glycosylases are discussed to showcase how QM calculations on nucleoside/tide and small molecule complexes uncover roles of active site interactions and the preferred order of reaction steps along DNA repair pathways. Furthermore, the ability of calculations on nucleic acid–enzyme complexes that combine QM methods with molecular mechanics (MM) force fields to challenge traditional views of enzyme function and lead to consensus for mechanistic pathways is illustrated. Subsequently, QM-based studies of select nucleases are discussed to highlight how this methodology can discern the various strategies enzymes use to cleave nucleic acid backbones. Overall, this contribution underscores the value in combining QM-based computational work with experimental studies to uncover enzyme-facilitated nucleic acid chemistry to be harnessed in future medicinal, biotechnological and materials applications.

Introduction

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) form the basis of life by storing, transmitting, and expressing genetic information. Nucleic acids are composed of chains of nucleotides, with each canonical nucleotide containing one of five nucleobases (adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T, DNA) or uracil (U, RNA)). DNA carries the instructions required for organisms to develop, function, and reproduce in specific sequences of nucleotides, which selectively base pair (A:T and G:C) to form the famous double helix. In contrast, single-stranded RNA is necessary for the translation of the genetic code from DNA into proteins. Specifically, DNA is initially transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA) with each three-nucleobase sequence in mRNA then being decoded using transfer RNA (tRNA), which inserts the correct amino acid into the growing polypeptide chain with the help of ribosomal RNA (rRNA). However, RNA has roles beyond translation, including generating mRNA precursors (small nuclear RNA or snRNA), aiding modification of rRNA (small nucleolar RNA or snoRNA), regulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level (microRNA or miRNA), and regulating chromatin remodeling (long non-coding RNA or lncRNA). Outside of biological systems, nucleic acids have many practical applications, including gene cloning, genetic engineering, sample amplification, biosensors, therapeutics, tissue engineering, and biomaterials.

To enable the diverse array of nucleic acid functions, many enzymes are present in cells to catalyze difficult nucleic acid chemistry. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 For example, although DNA is frequently damaged from exposure to varied sources ranging from UV rays in sunlight and pesticides to automobile exhaust and plastics, 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 enzymes repair 4 , 10 , 11 or bypass 12 , 13 the resulting DNA modifications for cell survival. Alternatively, enzymes introduce or remove DNA modifications as part of epigenetic regulation 14 , 15 or to generate modification cascades 16 , 17 that impart diverse RNA structures and functions. A fundamental understanding of these biomolecular machines can be harnessed for advancements in medicine and nanotechnology. 18 , 19 For example, comprehending the function of natural enzymes can inspire the engineering of new synthetic proteins to facilitate the production of novel nucleic acid-based biomaterials, 20 , 21 while understanding how DNA damage can evade repair or be bypassed can assist in developing cancer treatments with greater efficacy. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 However, detailed information about the chemistry facilitated by nucleic acid-targeting enzymes is required to further improve these technologies.

Despite advancements in experimental biochemical tools, critical information about molecular reactions (transition structures, barrier heights) remains difficult to obtain. Indeed, since enzyme-catalyzed reactions are very fast, key species along reaction pathways are short-lived and challenging to characterize through experimental techniques. As a result, most currently available mechanistic information for enzymes that process nucleic acids has been conjectured from static, non-functional structures generated using X-ray crystallography and cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) coupled with knowledge of the catalytic contributions of different active site residues from mutagenesis experiments. Providing a unique, yet complementary, approach to uncovering molecular reactivity, computer calculations can characterize high-energy intermediates along chemical pathways. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 In terms of enzyme structure, calculations have the unique advantage of being able to describe wild-type systems in the presence of native substrates without requiring the introduction of modifications to inhibit catalysis that may induce changes in the active site not present in the real system. 34 , 35 , 36 , 37

Many steps in biochemical processes require large-scale shifts in biomolecular structure and therefore can be investigated using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that rely on molecular mechanics (MM) force fields to describe biomolecular structural dynamics. 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 However, other aspects of enzyme function, including deciphering the preferred catalytic pathway, require an accurate description of the fine details of electronic configurations and therefore techniques grounded in quantum mechanics (QM) must be applied. 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 The broad importance of quantum calculations to the discipline of chemistry was recognized with the 1998 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to W. Kohn and J. Pople. Although an abundance of information can be obtained by applying quantum mechanical methods to models ranging from tens to hundreds of atoms (quantum mechanical cluster methods), 43 , 44 the elucidation of the catalytic mechanisms of action of enzymes through comparisons to experimental data requires more realistic representations of the entire nucleic acid–enzyme complex (thousands of atoms). 45 , 46 , 47 Such modeling has come to fruition with the development of multiscale QM/MM techniques, the importance of which was acknowledged with the award of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to M. Karplus, M. Levitt, and A. Warshel.

In celebration of the 2025 International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, which marks 100 years since the initial development of quantum mechanics and strives to emphasize the importance of quantum science to diverse fields, this perspective discusses the contributions of quantum chemical calculations to our current understanding of the function of enzymes that process nucleic acids. Specifically, while acknowledging the diversity in problems related to nucleic acid-targeting enzymes that have been addressed in the literature as well as the significant contributions of other computational methods (MD simulations), select examples will be discussed that highlight how techniques based on QM aid in the elucidation of the reaction mechanisms and discrete protein–nucleic acid interactions utilized by enzymes to break the strong bonds between nucleobases and sugars (glycosidic bonds) and within phosphodiester backbones (phosphodiester bonds, Fig. 1). The information afforded from QM calculations about nucleic acid-targeting enzymes is vital for improving our fundamental understanding of nature and advancing the development of therapeutics and innovative enzymes for use in medicine and biotechnology, among many other applications.

Glycosidic (highlighted in red) and phosphodiester (blue) bonds in DNA (R=H) or RNA (R=OH) nucleotides processed by many enzymes, as well as representative enzymes discussed in the present work.

Enzymatic glycosidic bond cleavage

The N-glycosidic bond that links a nitrogenous base to the sugar–phosphate backbone plays a role in the structure, stability, and flexibility of nucleic acids. Cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond is also important for many processes, including nucleobase salvage 48 and DNA repair. 4 , 49 However, the high stability of the nucleobase–sugar linkage necessitates catalytic cleavage. 50 In cells, glycosidic bond cleavage of damaged DNA is catalyzed by enzymes known as DNA glycosylases, 4 , 49 , 51 , 52 which are responsible for initiating the base excision repair (BER) process. 53 , 54 DNA glycosylases are of interest because changes in their expression levels in cells have been linked to many diseases, 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 including cancer, neurodegeneration, and metabolic dysfunctions, and some repair enzymes have been shown to drive proper epigenetic programming in early embryo development. 61 , 62 , 63 Additionally, understanding the reaction mechanisms and structurally characterizing transition states (TS) associated with DNA glycosylases can lead to the development of highly specific and potent small molecule inhibitors for use as therapeutics. 64 , 65 , 66 , 67

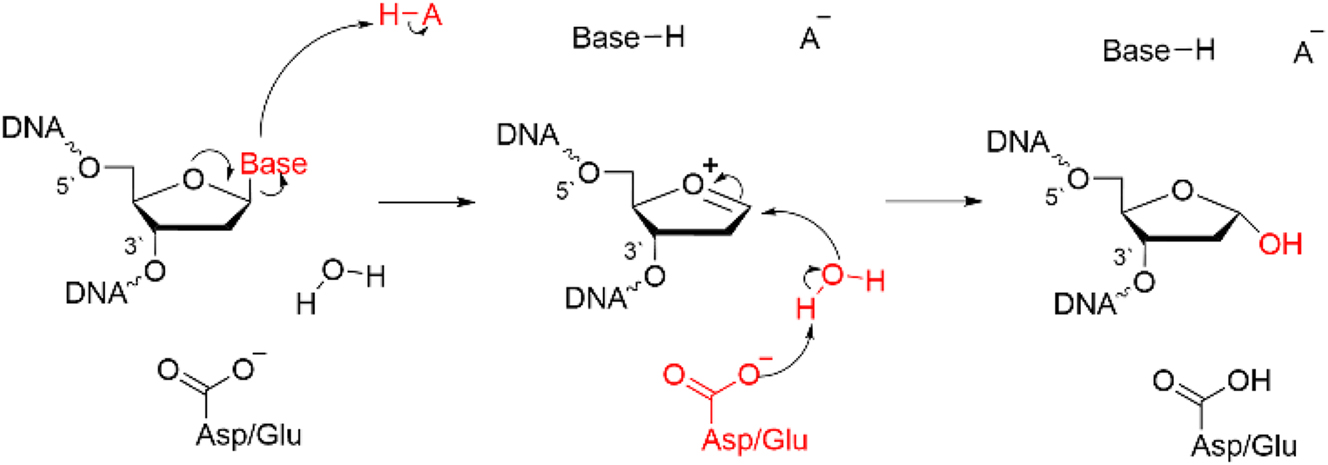

The general mechanism of action of many DNA glycosylases (Fig. 2) 4 , 49 , 51 , 52 , 68 involves using key active site amino acids to identify damaged nucleobases, which are activated for departure through protonation, strong hydrogen bonds, and/or stacking interactions. Nucleobase departure generates an oxocarbenium ion, which is simultaneously or subsequently attacked by a nucleophile to form a stable product. For monofunctional glycosylases, which solely cleave glycosidic bonds, the nucleophile is traditionally a water molecule that is activated by a conserved Asp/Glu in the active site. 51 , 52 , 68 For bifunctional glycosylases, a conserved Lys or Pro residue attacks the oxocarbenium ion to form a crosslink with the eventual cleavage of the phosphodiester bond in the 3′ and/or 5′ direction(s) further along in the repair process (discussed below). 51 , 52 , 68 Despite our broad understanding of these general steps, the atomic level details of the function of many glycosylases are not currently clear, and new enzymes and alternate functions for previously identified enzymes are being discovered. Although MD simulation-based methods have been employed to study many DNA glycosylases (see, for example, references [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80), the sections below focus on select examples studied by our research team and others that highlight the useful information obtained from techniques grounded in quantum science.

General mechanism of action of (monofunctional) DNA glycosylases.

Quantum chemical calculations highlight new roles for active site residues in nucleobase departure and nucleophile activation in the mechanism of action of uracil DNA glycosylase

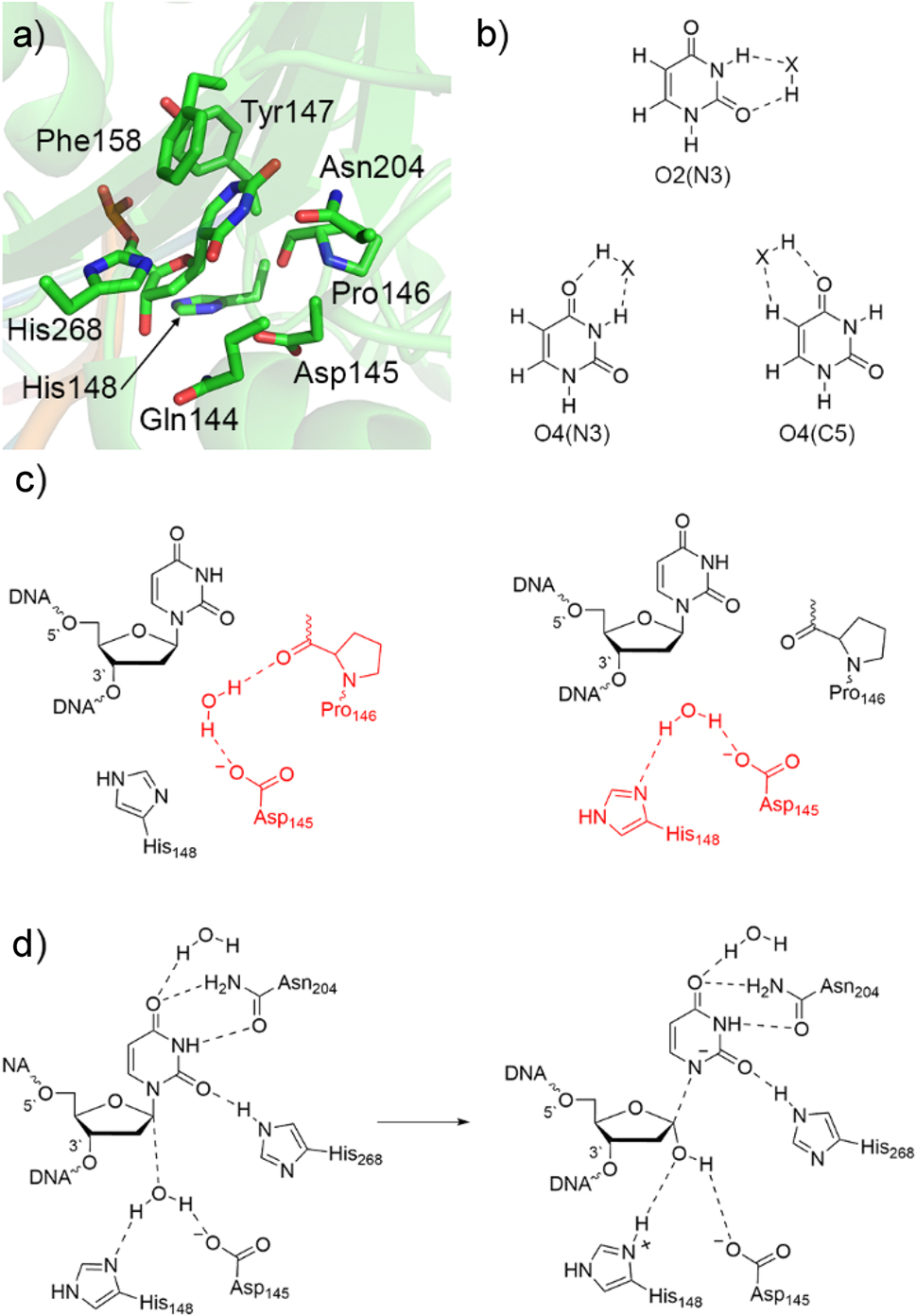

Uracil DNA glycosylases (UDG in Escherichia coli; hUNG2 in humans) form perhaps the most widely studied class of glycosylases. 81 In most cases, uracil erroneously arises in DNA following the hydrolytic deamination of cytosine, 82 which can lead to a CG to TA mutation upon multiple rounds of DNA replication. 81 An abundance of experimental data, 81 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 including high-resolution crystal structures (PDB ID: 1EMH; 87 Fig. 3a), have provided clues about the mechanism of action of uracil DNA glycosylases and identified important contacts between the damaged nucleotide and active site residues (including histidine, asparagine, and phenylalanine side chains). However, the magnitude of these interactions and the specifics of how active site residues stimulate hydrolysis remained unknown prior to computational work.

Characterization of the UDG catalytic mechanism. (a) Active site of uracil DNA glycosylase from a crystal structure of UDG bound to pseudouridine-containing DNA (PDB ID: 1EMH). (b) Hydrogen-bonding sites of U considered in QM studies (X = HF, H2O, NH3, CH4, or an amino acid side chain). (c) Active site configurations of the nucleophilic water (red) considered in QM/MM calculations. (d) Proposed UDG mechanism of action predicted by QM-based calculations.

Quantum chemical calculations have been used to understand how interactions with active site amino acids enhance the acidity of uracil, thereby generating an effective leaving group for the hydrolysis reaction. 88 , 89 Specifically, a series of small molecules (HX = hydrogen fluoride, water, ammonia, or methane) were positioned next to a variety of uracil hydrogen-bonding sites (O2(N3), O4(N3) and O4(C5), Fig. 3b). These hydrogen-bonding interactions were found to increase the gas-phase B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d) acidity of U by up to 50 kJ/mol, making uracil a higher quality leaving group. The largest effect was observed at the O2(N3) binding position, 88 which corresponds to the location of His268 in the UDG active site (Fig. 3a). 87 Nevertheless, hydrogen bonds at other U binding positions still have a significant effect and the simultaneous impact of two small molecules was found to be equal to the sum of the individual effects (additive), 88 , 89 emphasizing the importance of multiple nucleobase–enzyme interactions in stabilizing the departing base. Furthermore, despite stacking with the side chain functional groups of Phe, Tyr, Trp, or His decreasing the MP2/6-31G*(0.25) acidity of U by 10–20 kJ/mol, the effect of U hydrogen bonding with an aromatic amino acid is nearly equivalent to that observed for a small molecule (HX). 90 In fact, the most significant increase in U acidity (53.5 kJ/mol) was observed when hydrogen bonding with histidine, 90 at least partially explaining the role of His268 in the UDG active site (Fig. 3a). Although the magnitude of the effect of hydrogen bonding and stacking decreases when moving from a gas phase model to an enzymatic environment (PCM-B3LYP, ε = 4), 91 , 92 the impact of noncovalent interactions on U acidity remains significant. In fact, the computationally predicted effect of histidine hydrogen bonding at O2 on the acidity of U 90 closely aligns with the experimentally predicted catalytic effect of His268, 93 suggesting that the vast majority of the catalytic contribution of this active site amino acid arises due to stabilization of the uracil anion. These studies emphasize the usefulness of quantum chemical techniques coupled with small molecular models for understanding the roles of active site interactions in nucleobase activation along DNA repair pathways.

To complement QM insights regarding the acidity of uracil, the impact of small molecules on the deglycosylation reaction barrier was considered using nucleoside/tide models. 92 , 94 , 95 In the presence of a single water molecule, O2 of the departing U abstracts a proton from the nucleophile as water attacks the sugar, resulting in a high B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d) barrier (159.7 kJ/mol). 94 However, the reaction barrier steadily decreases with an increase in the basicity of the small molecule hydrogen bonding with the nucleophile, 94 emphasizing the importance of nucleophile (water) activation in glycosidic bond cleavage. Furthermore, the reaction barrier decreases by a similar magnitude of the nucleobase acidity increase upon hydrogen bonding small molecules to U, regardless of the implicit environment considered. 94 Interestingly, the M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p) stacking of benzene (representing the phenylalanine side chain) with the U nucleobase during nucleoside deglycosylation was found to be anticatalytic in environments that most closely resemble the UDG active site, 96 suggesting that the small observed catalytic impact of Phe158 87 likely arises from active site structural rearrangements due to sterics rather than intrinsically lowering the reaction barrier. Taken together, these quantum chemical calculations emphasize that simultaneous activation of both the nucleophile and the nucleobase is important for catalysis of the N-glycosidic bond cleavage in damaged nucleic acids.

Despite the useful information about deglycosylation reactions obtained from QM calculations on nucleotide models, the lack of an explicit active site environment limits the conclusions that are applicable to the real enzyme. Nevertheless, multiscale computational approaches have bridged the gap between these small model findings and experimental unknowns for the UDG mechanism of action. Although an early study mapped the UDG reaction pathway using a semi-empirical (AM1) method to describe a small (32 atom) QM region in QM/MM (AM1/CHARMM) simulations, 97 , 98 His148 was erroneously modeled as cationic, with later experimental data supporting a neutral protonation state. 99 Subsequently, ONIOM(MPWB1K/6-31G(d):PM3) calculations on a truncated model that includes all residues within 10 Å of the glycosidic bond of the substrate according to a crystal structure of hUNG2 (PDB ID: 1EMH) 87 were employed to map the reaction surface. 100 Due to the absence of hydrogen atoms in the experimental crystal structure, two possible orientations of the water nucleophile were considered (Fig. 3c). Although water hydrogen bonds to the proposed base (Asp145) in both active site architectures, the first model includes an additional water hydrogen bond to Pro146, while the second model replaces this with a water hydrogen bond to His148. Both resulting reaction surfaces correspond to a highly dissociative mechanism in agreement with experimental kinetic isotope effects (KIE). 86 In both predicted reactions, the glycosidic bond lengthens significantly in the first transition state, which is followed by electrophile (C1′) migration towards the water nucleophile coupled with barrierless addition of a hydroxy group to the anomeric carbon. A water proton is simultaneously transferred to Asp145 in the first model, while the proton was transferred to His148 in the second model which resulted in enhanced thermodynamic stability (Fig. 3d). These QM/MM calculations provided the first evidence that the energetically preferred pathway involves His148 activating the water nucleophile, shattering the long-held belief that an Asp or Glu was always the final proton acceptor. The calculations also revealed that His268, Asn204, and an active site water form strong hydrogen bonds to U throughout the reaction pathway, 100 supporting the results from QM models that several residues work together to stabilize the negative charge forming on the departing nucleobase. 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 94 This new computationally predicted mechanism is fully consistent with all experimental data available for UDG, 81 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 99 highlighting the importance of QM techniques in unveiling the intricate chemical details of DNA repair pathways.

Subsequent QM/MM (B3LYP-D3/6-31G(d,p):AMBER) calculations on a model containing 1498 atoms in the QM region verified that His148 is the preferred nucleophile activator. 101 Furthermore, the computationally predicted mechanism involving His148 activation of the water nucleophile was shown to rationalize Cd2+-inhibition of UDG using QM/MM (PM3/AMBER) MD and ONIOM(QM:MM) (LC-ωPBE:AMBER) calculations (6-311+G(d) for C, N, O, and H; def2-TZVPD for Cd(II)). 102 The most recent computational study of the UDG mechanism of action used QM/MM (B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p):AMBER) to emphasize the importance of an internal electric field in the active site for catalysis and supported His148 as the final proton acceptor. 103

The example of UDG underscores the value in small model QM calculations as well as in coupling quantum mechanical techniques with MM methods to elucidate the details of the catalytic activity of DNA glycosylases. Indeed, through a combination of different QM-based methodologies, the critical roles of active site residues in activating the nucleobase for departure and the water molecule for nucleophilic attack have come to light, leading to a consensus in the literature regarding the mechanistic pathway (Fig. 3d). As a result, the general mechanism of action of DNA glycosylases in terms of the conserved role of an active site Asp/Glu (Fig. 2) has been challenged, a conclusion that was only possible due to the development and application of techniques grounded in quantum science.

Quantum chemistry unveils a unique mechanism of action for adenine DNA glycosylase that further redefines the role of an active site aspartate

Adenine DNA glycosylase (MutY in bacteria; MUTYH in humans) functions as part of a series of enzymes that combat the major oxidation product of DNA, namely 8-oxoguanine (8oxoG). 104 Specifically, when G is damaged to 8oxoG, A is typically inserted opposite 8oxoG after one round of DNA replication, which leads to a G:C to T:A mutation following a subsequent replication step. If the damaged 8oxoG is removed from the intermediate 8oxoG:A pair, a T:A mutation will still be generated. 105 Therefore, it is the role of MutY to excise A that is mispaired opposite 8oxoG prior to other enzymes removing the damaged nucleotide and restoring the original DNA sequence. 106 , 107

Despite the accepted function of MutY, the catalytic mechanism for A excision has been the subject of debate in the experimental and computational literature. Understanding the mechanism of action is critical because mutations in MUTYH have been linked to a hereditary syndrome known as MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP). 108 , 109 , 110 Patients with MAP develop colon polyps, which are initially benign and relatively localized, but over time can become cancerous and spread throughout the body. 108 , 109 , 110 Some mutations associated with MAP occur close to the MUTYH active site, 111 suggesting that understanding the mechanism of action may aid in the prediction of the severity of the disease as well as the development of appropriate treatment strategies.

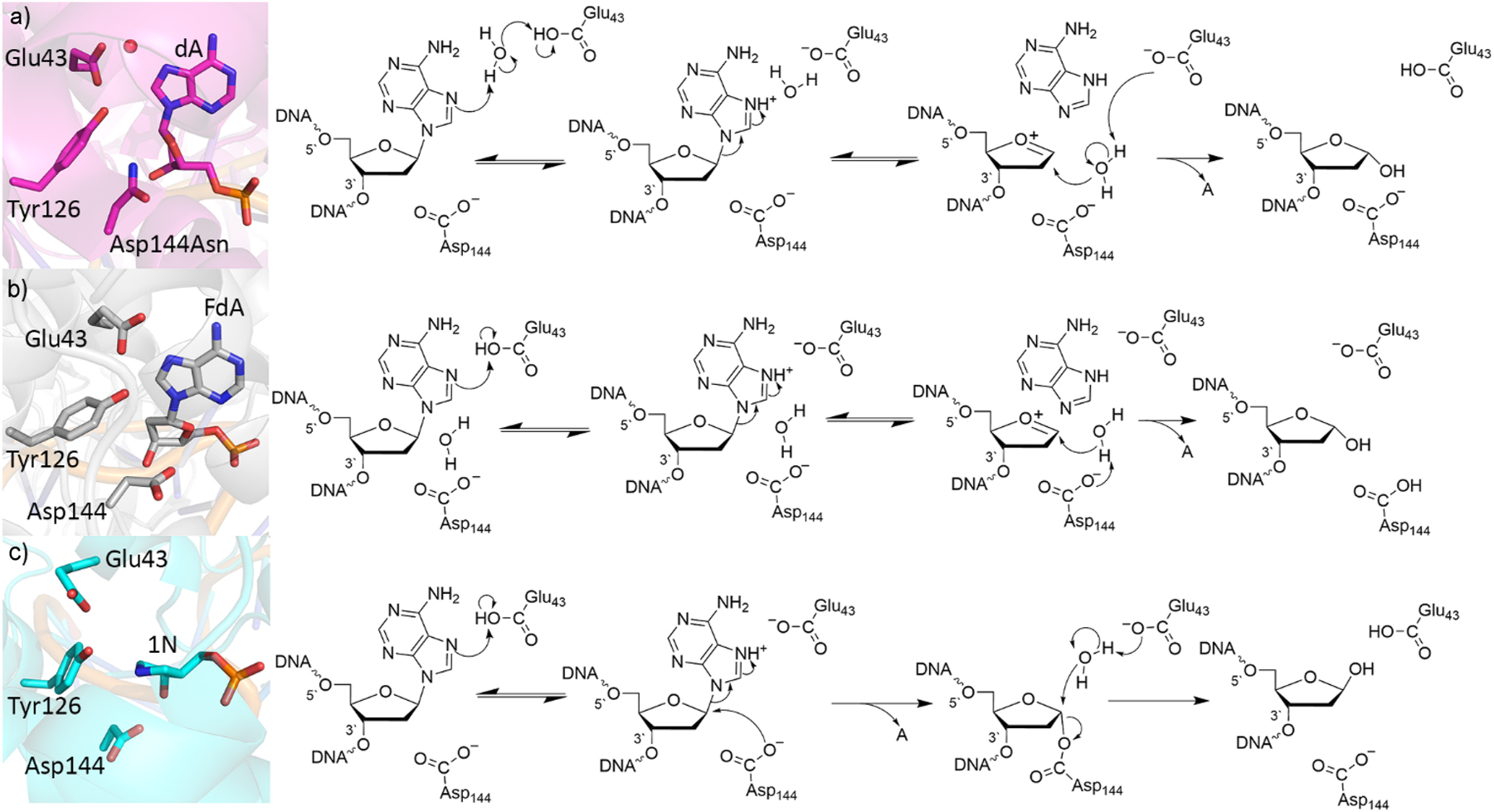

Some of the first clues about the MutY mechanism of action were obtained from a crystal structure of an Asp144Asn mutant (PDB ID: 1RRQ; Fig. 4a). 112 Based on the relative positioning of Glu43 and A in this crystal structure, it was proposed that a proton is transferred from Glu43 through water to protonate N7 of A, which promotes nucleobase departure and generates an oxacarbenium ion that is stabilized by Asp144 (Fig. 4a). In the next proposed reaction step, Glu43 activates a water nucleophile, which attacks C1′ to yield an abasic site product with inversion of stereochemistry. This mechanism was supported by KIE coupled with ab initio quantum chemical calculations (HF/6-31G(d)) on nucleoside models 113 as well as B3LYP/aug-cc-pVDZ//B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) calculations on a model that included the A nucleoside, glutamic acid, and two water molecules. 114 While QM/MM (B3LYP/AMBER) simulations under the Car-Parrinello MD scheme also highlighted the critical role of Glu43 in protonating N7 of A to initiate the reaction, the departed monoprotonated A was proposed to activate the water nucleophile for the second reaction step. 115 Nevertheless, although Asp144 plays the important role of stabilizing the reaction intermediate in this proposed mechanism, this differs from the more direct involvement of the conserved Asp/Glu in the active sites of other monofunctional glycosylases (Fig. 2). 4 , 49 , 51 , 52 Furthermore, mutational studies indicate a more involved role of Asp144 in the MutY mechanism of action. 116

Crystal structure (left) and corresponding proposed mechanism (right) of the (a) lesion recognition complex (LRC) containing the Asp144Asn mutant (PDB ID: 1RRQ), (b) fluorine recognition complex (FLRC) containing MutY bound to 2-β-fluoro-2-deoxyadenosine (PDB ID: 3G0Q), and (c) transition state analogue complex (TSAC) with MutY bound to a pyrrolidine transition state analogue (PDB ID: 6U7T).

Additional insight into the potential role of Asp144 was obtained from a subsequent crystal structure with a fluorinated A-containing substrate in the UDG active site (PDB ID: 3G0Q; 117 Fig. 4b). In this structure, Glu43 forms a direct hydrogen bond with N7 of A, suggesting that Glu43 may directly protonate A to activate the nucleobase for departure (Fig. 4b). In the second step, Asp144 (rather than Glu43) was proposed to activate a water nucleophile, which attacks the oxacarbenium ion to generate the final abasic site product. This mechanism was supported by QM/QM (ONIOM(M06-2X/6-31G(d):PM3)) calculations on a model built from this new crystal structure that included all residues within 10 Å of the substrate glycosidic bond, with the lower-level region held fixed to the crystallographic coordinates. 118 However, the calculations uncovered a significant decrease (by more than 1 Å) in the distance between D144 and the substrate throughout the reaction, 118 suggesting that Asp144 explicitly catalyzes deglycosylation by undergoing partial nucleophilic attack at the substrate. Furthermore, Tyr126 was proposed to play a significant catalytic role due to its close proximity to, and ability to hydrogen bond with, Glu43.

Following the above computational studies, a crystal structure of a transition state analogue was published, which showed a small distance between Asp144 and the modified substrate (PDB ID: 6U7T; 119 Fig. 4c). In fact, the distance between Asp144 and the substrate in the crystal structure of the transition state analogue (2.9 Å) 119 falls between that found in the previously reported QM/QM reactant (3.4 Å) and intermediate (2.4 Å) complexes. 118 Furthermore, new mutagenesis, kinetic, and NMR spectroscopic data were derived. 119 The mutagenic data strongly supported the QM/QM prediction that Tyr126 participates in catalysis. 118 , 119 However, the new experiments highlighted that the final abasic site product was generated with retention of stereochemistry, 119 which was a first in the DNA glycosylase literature and necessitated a revised catalytic mechanism.

Driven by the new experimental data, MD simulations coupled with QM/MM (ONIOM (M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,p):AMBER)//ONIOM(M06-2X/6-31G(d,p):AMBER)) calculations were performed on the entire DNA–MutY complex surrounded in water. 120 These calculations revealed that Asp144 can be appropriately posed to undergo nucleophilic attack at the substrate in the first reaction step, which can be facilitated by direct or water-mediated protonation of A at N7 by Glu43 (Fig. 4c). The average calculated barrier for this reaction step (41.3 ± 13.1 kJ/mol) is less than the experimental estimate for adenine release (∼80 kJ/mol) 121 and final product release (∼100 kJ/mol). 121 , 122 Formation of the DNA–protein crosslink is critical for active site alignment for the second reaction step, including permitting departure of the cleaved nucleobase and rearrangement of active site water. In the subsequent reaction step, Glu43 activates a water nucleophile, which displaces Asp144 to generate the final abasic site product, with a retention of stereochemistry at the sugar and an average calculated barrier of 106.5 ± 6.5 kJ/mol. Elegant QM/MM (B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p)/AMBER) calculations subsequently suggested that a strong internal electric field is responsible for permitting the double-displacement reaction mechanism. 123 This newly mapped catalytic pathway (Fig. 4c) agrees with the most accurate experimental evidence to date and challenges the standard monofunctional glycosylase mechanism (Fig. 2). Overall, the MutY example highlights the usefulness of quantum chemistry as well as how an interplay between experimental and computational studies is necessary to unveil the mechanistic details of DNA repair.

A direct hydrolysis mechanism for bifunctional 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase uncovered by quantum chemistry

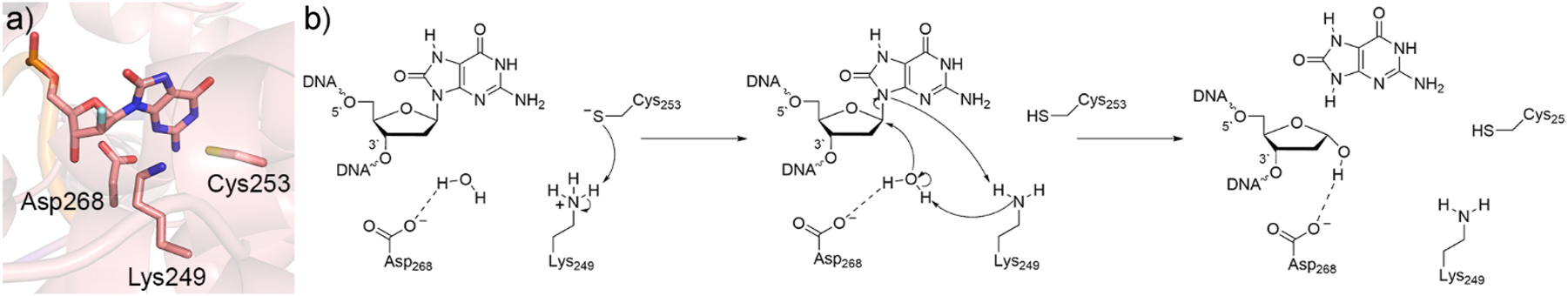

Following excision of adenine paired opposite 8oxoG by MUTYH, 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (hOgg1) initiates the removal of the damaged 8oxoG nucleobase in BER in humans. With its prominent role in protecting DNA, hOGG1 function has implications for human health specifically in regards to cancers, with certain hOGG1 polymorphisms being associated with gynecologic, 124 lung, 125 and rectal cancer. 126 Unlike the glycosylases discussed previously, hOgg1 is a bifunctional glycosylase and initiates the deglycosylation reaction via nucleophilic attack of an active site lysine on C1′, which is followed by the cleavage of the 3′-phosphate group with respect to the damaged nucleoside (β-elimination). However, the β-lyase activity is significantly slower than the glycosylase activity. 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 Indeed, apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease, which catalyzes β-elimination following glycosylase activity during BER, can dissociate hOGG1 prior to phosphodiester bond cleavage, 132 and can increase glycosylase activity and uncouple lyase activity, 133 resulting in hOGG1 behaving similarly to a monofunctional glycosylase. However, few atomic level details were available on this monofunctional mechanism for bifunctional hOGG1.

To fill this gap, QM calculations have investigated the monofunctional activity of hOGG1. Specifically, IEF-PCM-B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations revealed that an aspartate-activated water nucleophile lowers the deglycosylation barrier for the 8oxoG nucleotide by ∼20 kJ/mol compared to a lysine nucleophile in a protein environment (ε = 4), 134 indicating the hOGG1 monofunctional mechanism may proceed via direct hydrolysis of the glycosydic bond. However, a closer investigation of nucleobase displacement by lysine suggested that the most stable point on the SMD-M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,2p)//PCM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) Gibbs reaction surface corresponds to the DNA-protein crosslink formation following lysine attack prior to 3′-phosphodiester bond cleavage, 135 which could mean monofunctional hOGG1 activity still involves a lysine–DNA crosslink. To clarify the preferred mechanism, QM/QM (ONIOM(M06-2X/6-311+G-(2df,2p):PM6)) models of all residues within 10 Å of the substrate were generated based on a crystal structure of hOGG1 bound to a 2′-fluorinated substrate (PDB ID: 3KTU; 136 Fig. 5a). 137 These calculations confirmed that direct hydrolysis is more favorable. In the proposed mechanism, Cys253 deprotonates Lys249, which then activates the water nucleophile with Asp268 stabilizing the resulting oxacarbenium ion (Fig. 5b). The hOGG1 example again underscores the ability of quantum chemical approaches to compare and contrast diverse pathways and thereby identify unique preferred mechanisms that shed light on experimental observations.

Characterization of the hOGG1 catalytic mechanism. (a) Active site of hOGG1 from a crystal structure with a 2′-fluoro-dOG-containing DNA inhibitor (PDB ID: 3KTU). (b) Proposed monofunctional mechanism of action for hOGG1.

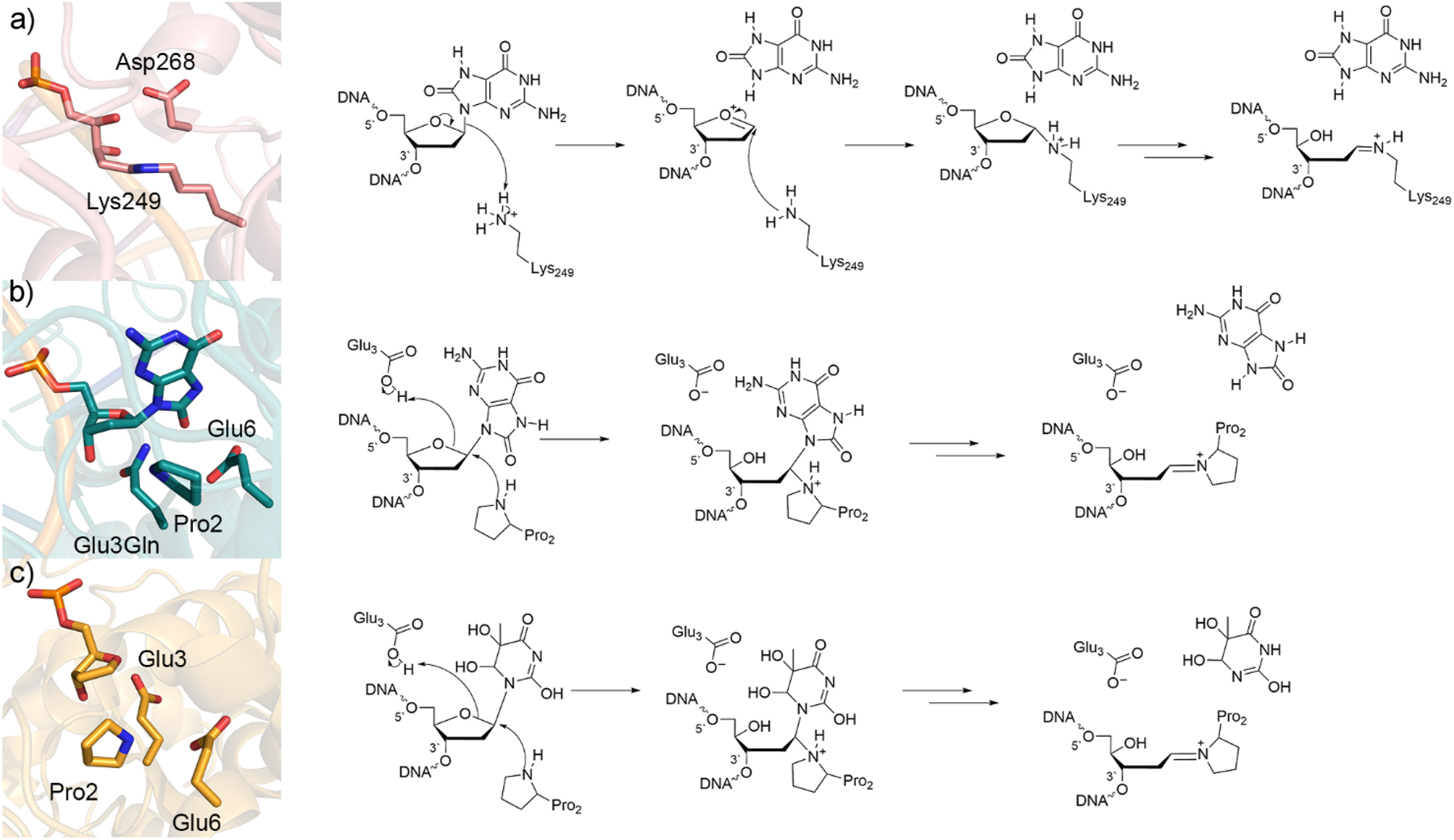

Quantum mechanical approaches help elucidate the mechanism for initiating bifunctional DNA glycosylase activity by an active site amine

While there is evidence that hOgg1 may exhibit monofunctional activity in certain conditions, 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 137 there is also strong evidence for the formation of a Schiff base intermediate through attack at the damaged nucleotide by an active site lysine (Lys249, Fig. 6a, PDB ID: 1HU0) 138 during bifunctional activity. Other bifunctional glycosylases are also known to form Schiff base intermediates, including formamidopyrimidine [fapy]-DNA glycosylase (FPG), which targets 8oxoG in bacteria using an active site proline (Pro2, Fig. 6b), and Nei-like 1 (NEIL1), which similarly uses proline (Pro2, Fig. 6c) to remove a wide variety of oxidized purines and pyrimidines, with thymine glycol (Tg) being the preferred substrate. Therefore, to examine the intrinsic deglycosylation ability of lysine and proline, SMD-M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,2p)//PCM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations were performed using models that included a 3′ and/or 5′ nucleotide and lysine/proline side chain. 135 , 139 These calculations predicted a large barrier (∼150 kJ/mol) for deglycosylation regardless of the amine nucleophile, underscoring the importance of additional active site residues in stabilizing the departing nucleobase and the need for larger models to accurately describe this process.

Crystal structure (left) and corresponding mechanism (right) of the (a) wild-type hOGG1 trapped Schiff’s base intermediate (PDB ID: 1HU0), (b) Glu3Gln mutant FPG bound to 8oxoG substrate (PDB ID: 1R2Y), and (c) wild-type Neil1 bound to tetrahydrofuran (PDB ID: 5ITT).

QM/MM studies have provided additional insight into deglycosylation facilitated by bifunctional DNA glycosylases. For hOgg1, additive QM/MM (B3LYP-D3/SVP:AMBER) calculations suggest Lys249 is neutral and attacks C1′ of the 8oxoG nucleotide, while neutral Asp268 donates a proton to O4′ of the sugar, with several proton transfers between Lys249 and the nucleobase required to complete the glycosidic bond cleavage step. 140 However, this enzymatic mechanism is unlikely in a cellular environment as lysine and aspartate would not simultaneously adopt neutral protonation states in such close proximity in the active site. Another study with more biologically relevant active site protonation states used QM/QM (ONIOM(CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p):PM6)) calculations to optimize 8oxoG in the hOgg1 active site, followed by CPCM-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) calculations of the reaction pathway. 141 This modeling led to the proposal that the lysine nucleophile protonates N9 of 8oxoG during attack at C1′ of the sugar (Fig. 6a). This general mechanism was supported by subsequent small DFT (B3LYP-D2/6-31G(d,p)), medium QM/MM (ONIOM(CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p):PM6)), and large-scale QM/MM (ONIOM(B3LYP/6-31G(d,p):OLPS)) calculations, 142 which further concluded that Lys249 is also involved in damaged base recognition. Finally, QM/MM (ONIOM(M06-2X/6-31G(d,p):OPLS)) calculations retains support for Lys249 protonation at N9 of 8oxoG while also illuminating the importance of Asp268 in this proposed delycoylsation mechanism, with several proton transfers between Lys249, Asp268, and the departed 8oxoG nucleobase being required between cleavage of the glycosidic bond and the formation of the Schiff’s base product (Fig. 6a). 143 Together these QM/MM calculations uncovered the details of hOGG1-facilitated deglycosylation of the major oxidative DNA damage product.

Elegant calculations have also been done to understand FPG and NEIL1 activity and thereby provide clues about catalysis through an active site proline that complement previous DFT investigations. For FPG, QM/MM (ONIOM(BP86/6-311G**:AM1)) calculations uncovered a deglycosylation mechanism in which Pro2 attacks C1′ and Arg223 protonates O6 of 8oxoG. 144 However, unlike the lysine based mechanism of hOGG1, subsequent QM/MM (ONIOM(B3LYP-D3/SVP:Amber)) calculations investigating the excision mechanism for anti and syn-Bound 8oxoG concluded that the preferred mechanism for FPG does not involve initial nucleobase protonation. 145 , 146 Instead, Glu3 protonates O4′ of the sugar, while proline attacks C1′ (Fig. 6b). For NEIL1, QM/MM (SCC-DFTB/AMBER) simulations considered different Tg tautomers and active site conformations based on experimental crystal structures. 147 , 148 The preferred catalytic pathway promotes tautomerization of the Tg substrate to optimize binding. Much like FPG, the predicted NEIL1 excision mechanism involves Glu3 protonating O4′ of the damaged nucleotide, while Pro2 attacks C1′ (Fig. 6c). In all cases, subsequent proton transfers between the nucleophile, a neighboring glutamate side chain, and/or the departed nucleobase facilitate the formation of the final Schiff base intermediate.

Together, these QM and QM/MM studies on hOgg1, FPG, and Neil1 underscore how quantum chemical calculations can further our understanding of enzyme-catalyzed nucleobase excision for diverse damaged DNA substrates (8oxoG, Tg) and nucleophiles (water, lysine, proline).

Enzymatic phosphodiester bond cleavage

Phosphodiester bonds in nucleic acids are highly resistant to degradation, having estimated half-lives of up to 30 million years under mild conditions. 149 , 150 Although this stability is critical for maintaining genome integrity, there are many essential biological processes that rely on cleavage of the P–O bond in the backbone of nucleic acids, including DNA repair and replication, 151 , 152 RNA processing, 153 , 154 , 155 viral defence, 156 , 157 and general cellular maintenance. 158 , 159 Nucleases are a broad class of enzymes that catalyze phosphodiester bond cleavage in DNA and RNA, providing 1017-fold rate enhancements over the uncatalyzed reactions. 149 , 150

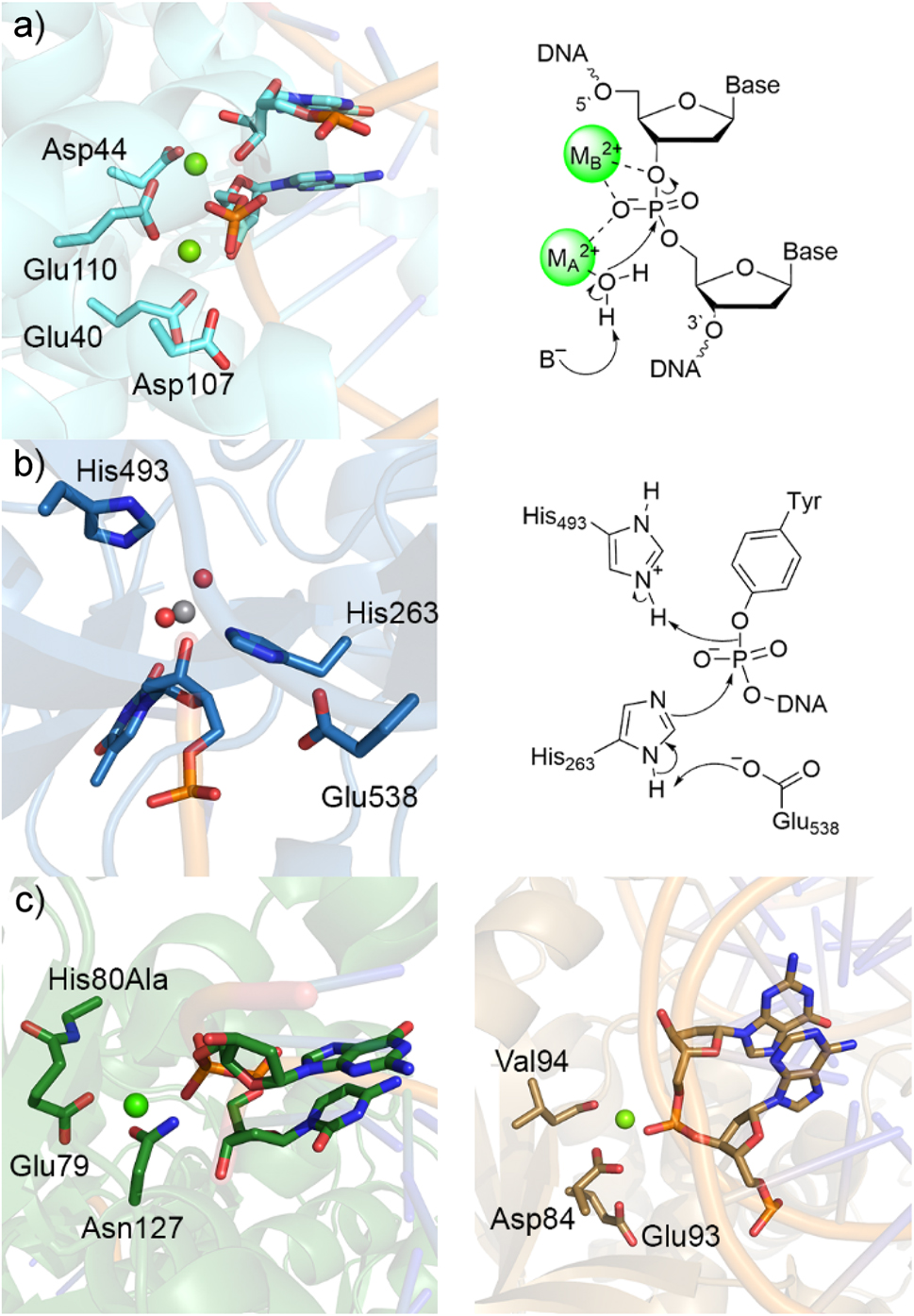

The most well-accepted mechanism for nuclease activity involves two metals (Fig. 7a). 160 , 161 , 162 Both metals coordinate to the nucleic acid to align the substrate and provide charge stabilization throughout the reaction. The nucleophile (water or hydroxide ion) is coordinated to the first metal (MA 2+), while the second metal (MB 2+) promotes leaving group departure through direct coordination to the substrate. Many experimental and computational works have been dedicated to understanding the function of two-metal mediated nucleases. 160 , 161 , 162 , 163 , 164 , 165 , 166 , 167 , 168 , 169 Importantly, QM-based techniques have provided critical clues about the chemistry facilitated by a variety of two-metal dependent nucleases, 164 , 169 , 170 , 171 , 172 , 173 , 174 , 175 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 , 182 , 183 , 184 highlighting that differences in the active site composition can lead to nuances in the chemistry in terms of the metal coordination and mechanism for substrate alignment and stabilization.

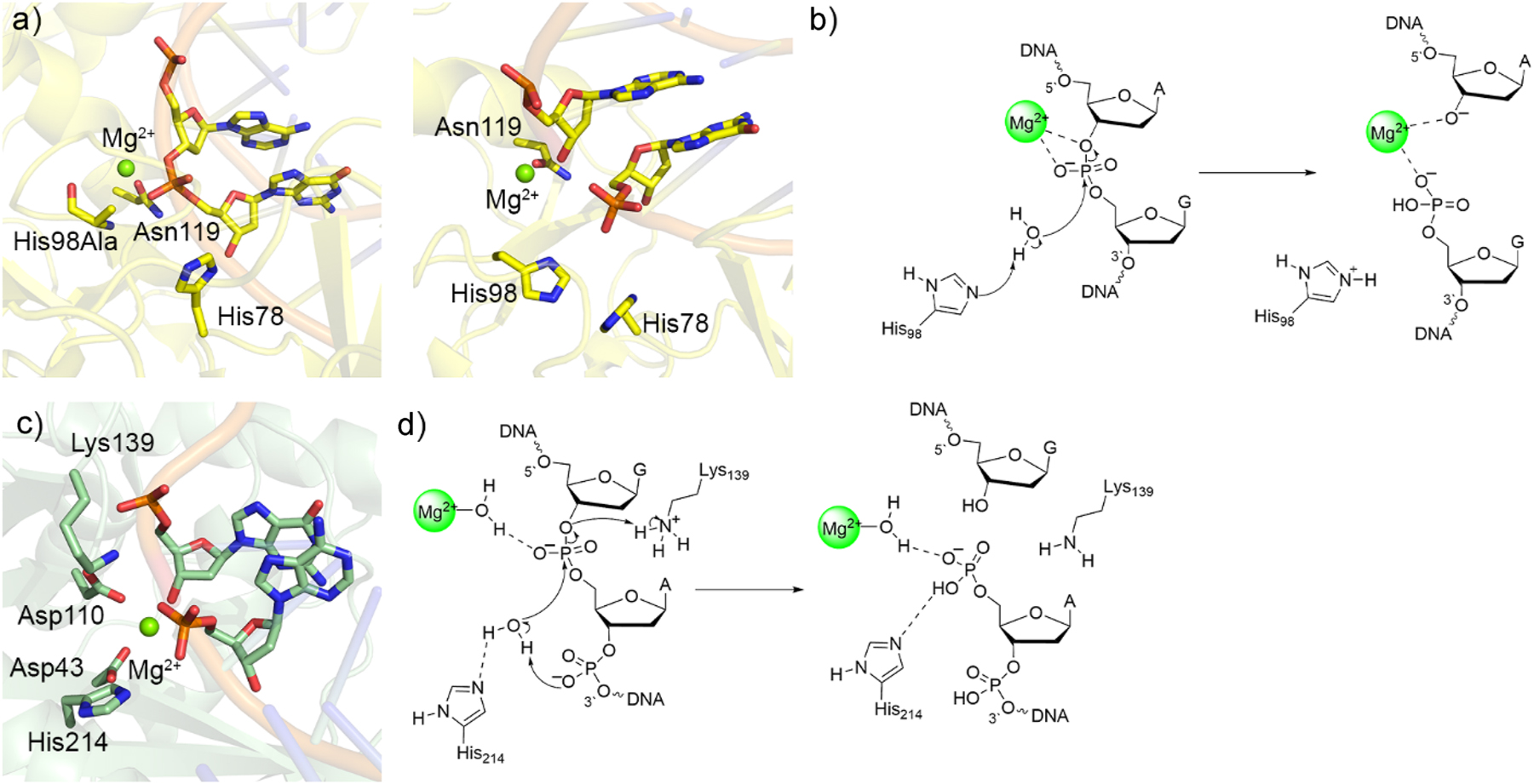

Structural characterization and the proposed catalytic mechanisms of representative one- or two-metal dependent or metal independent endonucleases. Crystal structure (left) and corresponding mechanism (right) of (a) two-metal-dependent RNase III bound to RNA substrate (PDB ID: 2NUG) and (b) Tdp1 bound to vanadate transition state mimic (PDB ID: 1RFF). (c) Crystal structures of one-metal-dependent Vvn His80Ala mutant (left, PDB ID: 1OUP) and BglII (right, PDB ID: 1D2I).

Despite the two-metal mediated mechanism being well established, other enzymes have been shown to catalyze P–O bond cleavage in nucleic acids without involving metals in the chemical step. Indeed, bifunctional glycosylases, such as hOgg1, FPG, and Neil1, cleave phosphodiester bonds in damaged DNA without the necessity of a metal ion (Fig. 6). Furthermore, following attack at the DNA backbone of an active site tyrosine in topoisomerase I (Topo I) as a step in untangling DNA in the nucleus, tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (Tdp1) catalyzes the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond between the tyrosine–nucleic acid crosslink using an active site histidine (Fig. 7b), 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 a proposal supported by QM-based calculations. 189 In addition to the 2-metal- and no-metal-mediated mechanisms, there is growing evidence that many nucleases only require a single metal for phosphodiester bond cleavage. Indeed, several nuclease crystal structures have emerged that reveal one metal near the substrate in the active site (Fig. 7c) 3 , 190 , 191 , 192 , 193 , 194 , 195 and kinetic data suggest that some nucleases only require a single metal for catalytic activity. 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 The discussion below uses examples from bifunctional glycosylases and single-metal dependent nucleases to highlight the diverse mechanistic pathways enzymes can use to cleave P–O bonds in nucleic acids that have been uncovered using quantum chemical techniques.

Quantum chemistry provides clues about the repair steps following deglycosylation by bifunctional glycosylases

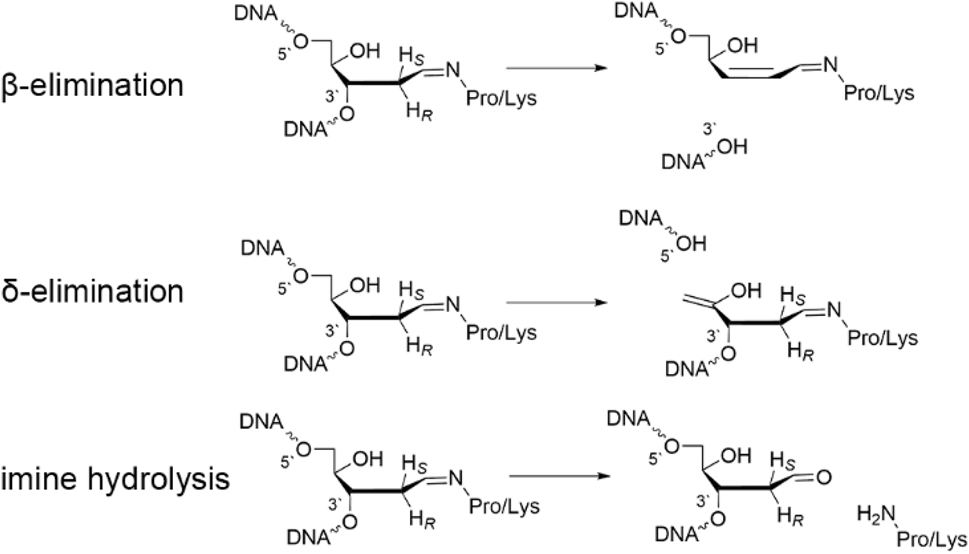

In addition to the potential monofunctional activity and deglycosylation through a lysine nucleophile discussed above (Figs. 5 and 6), hOGG1 is known to facilitate β-elimination. 138 Conversely, FPG 200 , 201 and NEIL1 202 , 203 exhibit both β- and δ-lyase activity using an active site proline (i.e., cleaves both the 3′ and 5′ phosphodiester bonds with respect to the damaged nucleoside). Although all QM/MM calculations on substrate-enzyme complexes to date have focused on the glycosidic bond cleavage step, 140 , 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 , 146 , 147 , 148 quantum chemistry has been coupled with nucleotide models to gain preliminary insight into the β- and δ-lyase activity of bifunctional glycosylases that utilize an active site lysine or proline to form an initial DNA–protein crosslink.

There are several factors that can be varied along the reaction pathway associated with lyase activity facilitated by bifunctional glycosylases (Fig. 8), including the conformation of the imine linkage (E/Z), the proton (pro–S/R) abstracted during elimination, and whether the ring-opening step is base catalyzed. SMD-M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,2p)//PCM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations on a system that included the damaged nucleoside 3′-monophosphate, and a model lysine or proline nucleophile were used to answer some of these key questions. 135 , 139 For bifunctional glycosylases that invoke a lysine nucleophile, deglycosylation was determined to most likely be followed by the formation of a ring-opened Schiff base intermediate via base-catalyzed transfer of the Nε pro–S rather than pro–R proton of the crosslink. 135 The ring-opened intermediate is highly flexible and can adopt many nearly isoenergetic conformations throughout the remainder of the mechanism, which suggests that the preferred lyase mechanism will be driven at least in part by the steric confines of the enzyme active site. Nevertheless, Nε pro–R proton abstraction reduces the barrier for the subsequent O3′-elimination. These key conclusions hold true for a proline nucleophile, 139 suggesting that the differential activity of enzymes such as hOGG1 that rely on lysine and those like FPG and NEIL1 that rely on proline primarily arise due to differences in active site compositions rather than their use of different nucleophiles.

Steps required for the lyase activity of bifunctional DNA glycosylases.

To compare β- and δ-lyase activity of bifunctional glycosylases that use an active site proline nucleophile, a subsequent study used SMD-M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,2p)//IEF-PCM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations and a ring-opened Schiff base model that includes both the 3′ and 5′-phosphate groups. 204 Regardless of P–O bond cleavage site, the calculations revealed that proton abstraction is required to initiate the reaction (from C2′ for β-elimination or C4′ for δ-elimination). Subsequently, phosphate elimination was found to be coupled with protonation, highlighting the necessity of the nuclease to stabilize the charge developing on the nucleic acid backbone. Interestingly, 5′-phosphate elimination was found to have a higher barrier than 3′-phosphate elimination, which may at least in part rationalize why some bifunctional glycosylases are restricted to β-lyase activity. 205 , 206 Overall, QM calculations coupled with small atomic models have provided critical insight into the dependence of bifunctional glycosylase and lyase activity on the amine nucleophile and can be used to direct future large-scale modeling of the P–O bond cleavage in DNA–protein complexes.

Quantum-based approaches support the feasibility of P–O bond cleavage by one-metal dependent nucleases

As mentioned above, there is growing evidence that nucleases can facilitate the phosphodiester bond cleavage in nucleic acids using a single metal, 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 typically magnesium. Nevertheless, conflicting information exists regarding the feasibility and mechanism for single-metal mediated nuclease activity. For example, kinetic data indicates that only one metal is necessary for the chemical step catalyzed by EcoRV, 207 while an X-ray crystal structure contains two metals in the EcoRV active site. 208 Quantum mechanical calculations have played a pivotal role in supporting the feasibility and mapping the mechanisms of single-metal dependent P–O bond cleavage.

An important nuclease in humans is AP endonuclease 1 (APE1), which continues the BER process following the function of a monofunctional glycosylase by cleaving the phosphodiester bond on the 5′ side of cytotoxic abasic sites. 209 , 210 Crystal structures containing a single metal in the APE1 active site are available for both reactant and product mimics (PDB IDs: 5DG0 195 and 4IEM; 211 Fig. 9a). However, metal coordination in the two structures differ, with the single metal being indirectly coordinated to the substrate through intervening water molecules in the reactant complex, 195 but direct metal coordination occurring in the cleaved product complex. 211 Therefore, QM cluster (IEF-PCM-M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,p)//M06-2X/6-31G(d,p)) calculations were performed using models of ∼150 atoms with different metal–substrate binding architectures (Fig. 9b), 212 , 213 , 214 with the model involving water-mediated (indirect) metal–substrate coordination resulting in the most energetically feasible barrier. The preferred metal binding configuration was then modelled in the DNA–APE1 complex and investigated with MD simulations followed by QM/MM(ONIOM(M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,p):AMBER14SB)//ONIOM(M06-2X/6-31G(d,p):AMBER14SB)) calculations. In the preferred mechanism (Fig. 9c), Asp210 activates a water nucleophile, which attacks the phosphorus to yield a phosphorane intermediate, which is stabilized through noncovalent interactions with His309. In the second reaction step, a metal activated water transfers a proton to the DNA backbone to cleave the P–O bond with a calculated rate-limiting barrier of ∼80 kJ/mol. This proposed mechanism is consistent with all experimental data, including the crystal structure of the reactant mimic (Fig. 9a), 195 experimental estimates for the Gibbs energy of activation (76.6 kJ/mol), 195 mutational data highlighting the important roles of Asp210 and His309 among other amino acids, 211 and the observed dependence of the reaction kinetics on the identity of the active site metal. 195 , 214 This study represented the first computational support for the feasibility of single-metal catalyzed phosphodiester bond cleavage.

Crystal Structures and computational models leading to the characterization of the APE1 mechanism of action. (a) Crystal structure of APE1 reactant complex with thiosubstituted substrate (left, PDB ID: 5DG0) and product complex (right, PDB ID: 4IEM). (b) QM cluster models of the APE1 reactant complex active site with direct (left) and indirect (right) metal–substrate coordination. (c) Proposed APE1 one-metal-mediated mechanism of action characterized with quantum mechanical techniques.

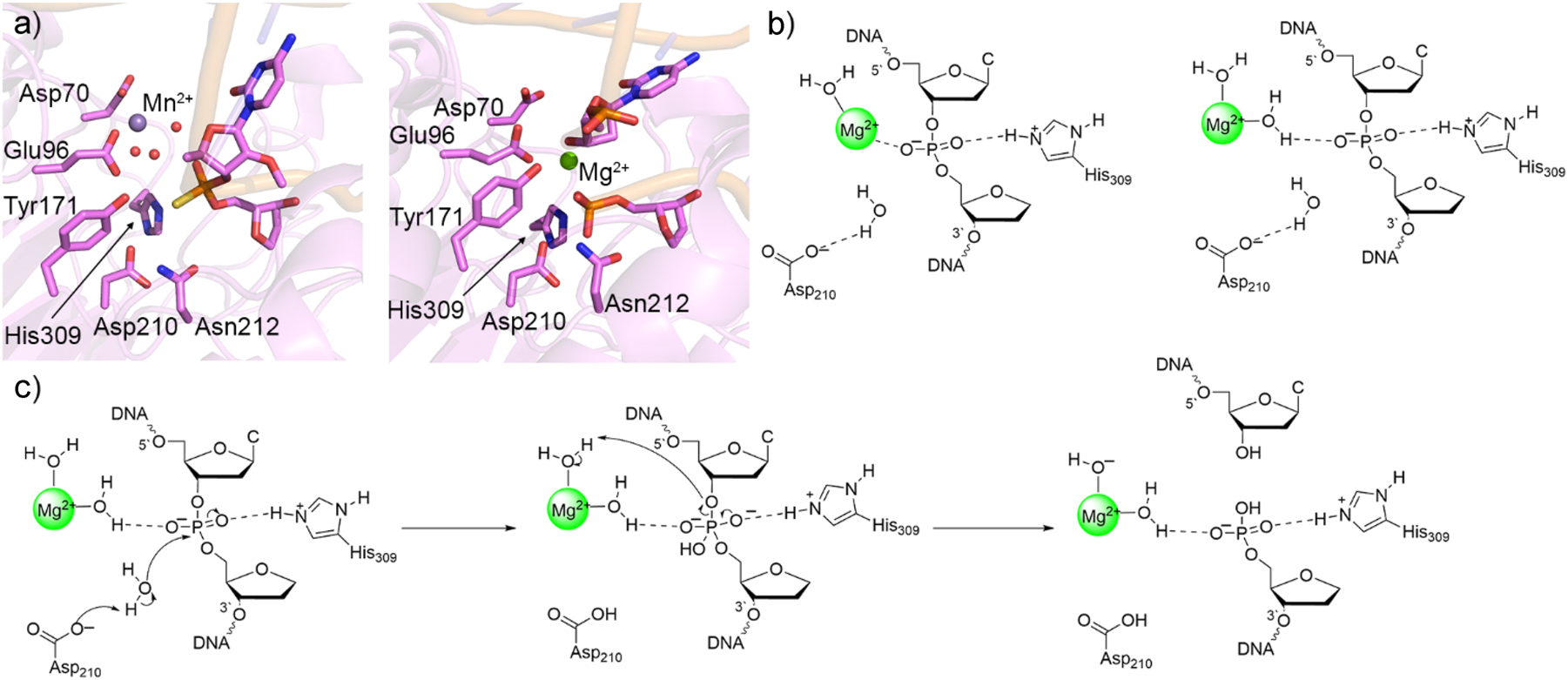

Following the computational work on APE1, several other single-metal dependent nucleases have been investigated using quantum chemical-based methodologies, which have further supported the feasibility of this chemistry along with the diversity in the mechanistic details. For example, unlike APE1, crystal structures of the reactant and product complexes for intron-encoded endonuclease (I-PpoI), a homing endonuclease, revealed direct metal–substrate coordination (PDB ID: 1CYQ 190 and 1A73; 215 Fig. 10a). The preferred reaction mechanism mapped using QM cluster (IEF-PCM-M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,p)//B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-31G(d,p)) and QM/MM (ONIOM(M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,p):AMBER)//ONIOM(B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-31G(d,p):AMBER)) involves water nucleophile activation by His98 and substrate stabilization by direct, bidentate magnesium coordination to DNA (Fig. 10b), 216 which is analogous to the elucidated role of MB 2+ in the two-metal mediated mechanism (Fig. 7a). 162 This contrasts the indirect metal–substrate coordination predicted for APE1 212 likely because of the stark absence of an active site amino acid that can provide additional substrate stabilization (i.e., a residue similar to His309 in APE1), which necessitates the metal to adopt this role. Adding further diversity to the catalytical mechanism of single-metal dependent nucleases, QM/MM (ONIOM(M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,p):AMBER)//ONIOM(B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-31G(d,p):AMBER)) calculations were used to map P–O bond cleavage by bacterial endonuclease V (EndoV) 217 for which only a crystal structure of the product complex exists (PDB ID: 2W35; 194 Fig. 10c). As seen for APE1, the calculations on EndoV suggest indirect metal coordination to the substrate is most favorable. 217 However, instead of the water nucleophile being activated by Asp as for APE1, 212 , 213 , 214 the proposed mechanism for EndoV involves water nucleophile activation by either His214 or the phosphate moiety of the substrate in the first reaction step. 217 Additionally, leaving group stabilization during P–O bond cleavage in the second EndoV reaction step is facilitated by Lys139 rather than a Mg2+ bound water, with the metal instead enhancing substrate positioning and stabilizing the charge build up on the phosphate (Fig. 10d). 217

Crystal structures and associated catalytic mechanisms of one-metal dependent I-PpoI and EndoV. (a) Crystal structures of His98Ala mutant I-PpoI reactant complex (right, PDB ID: 1CYQ) and wild-type I-PpoI product complex (left, PDB ID: 1A73). (b) Proposed I-PpoI mechanism of action. (c) Crystal structure of bacterial EndoV product complex (PDB ID: 2W35). (d) Proposed bacterial EndoV mechanism of action.

Together, the above examples highlight the unique chemistry facilitated by single-metal-dependent nucleases, with the composition of the active site finetuning mechanistic details. As an intriguing perspective on one versus two metal-dependent nucleases, MD simulations coupled with QM/MM (ONIOM(M06-2X/6-311+G(2df,p):AMBER)//ONIOM(B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-31G-(d,p):AMBER)) modeling on human EndoV highlighted the feasibility of both a single-metal mediated reaction with nucleophile activation by an active site aspartate (Asp240) and a two-metal mediated mechanism akin to those mapped for other nucleases. 179 The proposal that human EndoV may use either one or two metals for catalysis depending on the local metal cofactor concentration is supported by experimental evidence of both one and two-metal catalysis by PvuII endonuclease. 197 Thus, quantum chemical approaches have advanced our understanding of the metal dependence of many nucleases, with each enzyme possessing unique features that prevent a single mechanism from being universally applicable. As a result, more work remains to be done on this class of vital biomolecules.

Conclusions

The present perspective underscores the important role that quantum mechanics has played in the field of nucleic acid chemistry, specifically aiding the elucidation of key details in the mechanism of action of enzymes that process DNA and RNA. At the smallest scale, discussion of select enzymes highlights how QM-based methods are critical for advancing our understanding of noncovalent interactions between nucleic acid substrates, potential nucleophiles and active site residues that drive enzyme function, and reveal the relative order of key reaction steps. At the larger scale, combined QM/MM techniques applied to models of nucleic acid–enzyme complexes provide critical information about each step of the reaction mechanism in cellular environments with accuracy that allows for direct comparison and collaboration with experiment. Indeed, the examples discussed herein show that QM calculations can challenge traditional views of how members of certain families of enzymes catalyze nucleic acid bond cleavages, including active site residues performing nucleophile activation (His268 in UDG), 88 , 90 active site residues forming nucleic acid–protein crosslinks (Asp144 in MutY), 120 and hydrolysis by bifunctional glycosylases (hOgg1). 134 , 137 Furthermore, despite the well-accepted two-metal mediated phosphodiester bond cleavage pathway, QM methodologies have shown that a single metal 212 , 213 , 214 , 216 , 217 or an active site residue (no metals) 135 , 139 , 204 is sufficient to cleave nucleic acid backbones. While we acknowledge that QM-based studies have been done on other enzymes (for example, AAG, TDG, CRISPR-Cas9, phosphotriesterase, retroviral integrase, and ribonuclease H), 169 , 173 , 218 , 219 , 220 , 221 the examples covered in the present contribution underscore the impact of the initial development of quantum mechanics on advancing the field of enzyme-catalyzed nucleic acid chemistry. The insights obtained from such studies open the door for future research that can aid the design of new enzymes, therapeutics, and materials.

While the present perspective has focused on the conclusions gained from QM cluster and QM/MM methodologies for DNA–enzyme systems, it would be remiss to not mention other prominent computational methods that have been used to effectively study enzyme systems as well as up and coming techniques that show promise for future breakthroughs in the field. An example of one such technique is QM/MM metadynamics methods. While being more efficient than modeling an entire enzymatic system with QM methods, the quantum description of the high layer in QM/MM methodology prevents dynamic simulations from reaching the time scales required for biologically relevant processes to occur. Metadynamics simulations bypass this concern by applying a bias to the simulation that allows for sampling of high energy states at time scales reachable using QM/MM. This approach has been used extensively to study enzyme function, 222 , 223 , 224 including DNA–enzyme environments. 175 , 225 , 226 As another example, machine learning is primed to push our knowledge of enzyme–nucleic acid chemistry even further. 227 , 228 Indeed, machine learning potentials can be used to accelerate the discovery of minima 229 , 230 and transition state structures, 231 , 232 and can also be used in multiscale ML/MM for further increased computational efficiency. 233 , 234 Overall, computational enzymology has always been a fast evolving field and it is certain that new techniques will continue to be developed and applied to better our understanding of the complex interactions between nucleic acids and proteins.

Funding source: Canada Research Chairs

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021-00484

Funding source: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2016-04568

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate computational resources provided by the Digital Research Alliance of Canada (the Alliance) for studies performed in the Wetmore lab that were highlighted in the present review.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada [2016-04568], the Canada Research Chair Program [2018-400136 and 2021-00484], and the University of Lethbridge. DJN thanks NSERC (CGS-D), Alberta Innovates (AI), and the University of Lethbridge for student scholarships.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Cowan, J. A. Structural and Catalytic Chemistry of Magnesium-Dependent Enzymes. Biometals 2002, 15 (3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016022730880.10.1023/A:1016022730880Search in Google Scholar

2. Bush Natassja, G.; Evans-Roberts, K.; Maxwell, A. DNA Topoisomerases. EcoSal Plus 2015, 6 (2). https://doi.org/10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0010-2014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Yang, W. Nucleases: Diversity of Structure, Function and Mechanism. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2011, 44 (1), 1–93; https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033583510000181.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Jacobs, A. L.; Schär, P. DNA Glycosylases: In DNA Repair and beyond. Chromosoma 2012, 121 (1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00412-011-0347-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Tominaga, H.; Kodama, S.; Matsuda, N.; Suzuki, K.; Watanabe, M. Involvement of Reactive Oxygen Species (Ros) in the Induction of Genetic Instability by Radiation. J. Radiat. Res. 2004, 45 (2), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1269/jrr.45.181.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Prasad, S.; Gupta, S. C.; Tyagi, A. K. Reactive Oxygen Species (Ros) and Cancer: Role of Antioxidative Nutraceuticals. Cancer Lett. 2017, 387, 95–105; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.042.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Wang, L.; Wise, J. T. F.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, X. Progress and Prospects of Reactive Oxygen Species in Metal Carcinogenesis. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2016, 2 (4), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40495-016-0061-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Quezada-Maldonado, E. M.; Sánchez-Pérez, Y.; Chirino, Y. I.; García-Cuellar, C. M. Airborne Particulate Matter Induces Oxidative Damage, DNA Adduct Formation and Alterations in DNA Repair Pathways. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117313; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117313.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Rastogi, R. P.; Richa; Kumar, A.; Tyagi, M. B.; Sinha, R. P. Molecular Mechanisms of Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced DNA Damage and Repair. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010 (1), 592980; https://doi.org/10.4061/2010/592980.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Nouspikel, T. DNA Repair in Mammalian Cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66 (6), 994–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-8737-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Zharkov, D. O. Base Excision DNA Repair. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65 (10), 1544–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-008-7543-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Nohmi, T. Environmental Stress and Lesion-Bypass DNA Polymerases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 231–253; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142238.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Hübscher, U.; Maga, G. DNA Replication and Repair Bypass Machines. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011, 15 (5), 627–635; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.08.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Oliveira, P. H.; Fang, G. Conserved DNA Methyltransferases: A Window into Fundamental Mechanisms of Epigenetic Regulation in Bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29 (1), 28–40; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2020.04.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Rottach, A.; Leonhardt, H.; Spada, F. DNA Methylation-Mediated Epigenetic Control. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009, 108 (1), 43–51; https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.22253.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Sokołowski, M.; Klassen, R.; Bruch, A.; Schaffrath, R.; Glatt, S. Cooperativity between Different tRNA Modifications and their Modification Pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gene Regul. Mech. 2018, 1861 (4), 409–418; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2017.12.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Li, S.; Mason, C. E. The Pivotal Regulatory Landscape of RNA Modifications. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2014, 15, 127–150; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-090413-025405.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Jorgensen, W. L. Efficient Drug Lead Discovery and Optimization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42 (6), 724–733; https://doi.org/10.1021/ar800236t.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Sparvath, S. L.; Geary, C. W.; Andersen, E. S. Computer-Aided Design of RNA Origami Structures. 3D DNA Nanostructure: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, 2017; pp. 51–80.10.1007/978-1-4939-6454-3_5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Richter, F.; Baker, D. Chapter 6 – Computational Protein Design for Synthetic Biology. Synthetic Biology; Academic Press: Boston, 2013; pp 101–122.10.1016/B978-0-12-394430-6.00006-6Search in Google Scholar

21. Wang, F.; Li, P.; Chu, H. C.; Lo, P. K. Nucleic Acids and their Analogues for Biomedical Applications. Biosensors 2022, 12 (2), 93; https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12020093.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Duskova, K.; Lejault, P.; Benchimol, É.; Guillot, R.; Britton, S.; Granzhan, A.; Monchaud, D. DNA Junction Ligands Trigger DNA Damage and Are Synthetic Lethal with DNA Repair Inhibitors in Cancer Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (1), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b11150.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Fuso Nerini, I.; Roca, E.; Mannarino, L.; Grosso, F.; Frapolli, R.; D’Incalci, M. Is DNA Repair a Potential Target for Effective Therapies against Malignant Mesothelioma? Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 90, 102101; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102101.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Mechetin, G. V.; Endutkin, A. V.; Diatlova, E. A.; Zharkov, D. O. Inhibitors of DNA Glycosylases as Prospective Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (9), 3118; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093118.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Jiang, M.; Jia, K.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; He, Y.; Zhou, C. Alterations of DNA Damage Repair in Cancer: From Mechanisms to Applications. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8 (24), 1685; https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-2920.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Gad, H.; Koolmeister, T.; Jemth, A.-S.; Eshtad, S.; Jacques, S. A.; Ström, C. E.; Svensson, L. M.; Schultz, N.; Lundbäck, T.; Einarsdottir, B. O.; Saleh, A.; Göktürk, C.; Baranczewski, P.; Svensson, R.; Berntsson, R. P. A.; Gustafsson, R.; Strömberg, K.; Sanjiv, K.; Jacques-Cordonnier, M.-C.; Desroses, M.; Gustavsson, A.-L.; Olofsson, R.; Johansson, F.; Homan, E. J.; Loseva, O.; Bräutigam, L.; Johansson, L.; Höglund, A.; Hagenkort, A.; Pham, T.; Altun, M.; Gaugaz, F. Z.; Vikingsson, S.; Evers, B.; Henriksson, M.; Vallin, K. S. A.; Wallner, O. A.; Hammarström, L. G. J.; Wiita, E.; Almlöf, I.; Kalderén, C.; Axelsson, H.; Djureinovic, T.; Puigvert, J. C.; Häggblad, M.; Jeppsson, F.; Martens, U.; Lundin, C.; Lundgren, B.; Granelli, I.; Jensen, A. J.; Artursson, P.; Nilsson, J. A.; Stenmark, P.; Scobie, M.; Berglund, U. W.; Helleday, T. MTH1 Inhibition Eradicates Cancer by Preventing Sanitation of the dNTP Pool. Nature 2014, 508 (7495), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13181.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Huber, K. V. M.; Salah, E.; Radic, B.; Gridling, M.; Elkins, J. M.; Stukalov, A.; Jemth, A.-S.; Göktürk, C.; Sanjiv, K.; Strömberg, K.; Pham, T.; Berglund, U. W.; Colinge, J.; Bennett, K. L.; Loizou, J. I.; Helleday, T.; Knapp, S.; Superti-Furga, G. Stereospecific Targeting of MTH1 by (S)-Crizotinib as an Anticancer Strategy. Nature 2014, 508 (7495), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13194.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Helleday, T.; Petermann, E.; Lundin, C.; Hodgson, B.; Sharma, R. A. DNA Repair Pathways as Targets for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8 (3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2342.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Schrempf, A.; Slyskova, J.; Loizou, J. I. Targeting the DNA Repair Enzyme Polymerase Θ in Cancer Therapy. Trends Cancer 2021, 7 (2), 98–111; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2020.09.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Chin, Y. P.; See, N. W.; Jenkins, I. D.; Krenske, E. H. Computational Discoveries of Reaction Mechanisms: Recent Highlights and Emerging Challenges. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20 (10), 2028–2042. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1OB02139G.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Liang, J.; Zhen, P.; Gan, P.; Li, Y.; Tong, M.; Liu, W. DFT Calculation of Nonperiodic Small Molecular Systems to Predict the Reaction Mechanism of Advanced Oxidation Processes: Challenges and Perspectives. ACS ES&T Eng. 2024, 4 (1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestengg.3c00204.Search in Google Scholar

32. Schramm, V. L. Enzymatic Transition States, Transition-State Analogs, Dynamics, Thermodynamics, and Lifetimes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 703–732; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100742.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Schramm, V. L. Enzymatic Transition States and Drug Design. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118 (22), 11194–11258. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00369.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Ryde, U.; Dong, G.; Li, J.; Feldt, M.; Mata, R. A. Computational Studies of Molybdenum and Tungsten Enzymes. Molybdenum and Tungsten Enzymes: Spectroscopic and Theoretical Investigations; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, 2016.10.1039/9781782628842-00275Search in Google Scholar

35. Kaur, R.; Nikkel, D. J.; Wetmore, S. D. Computational Studies of DNA Repair: Insights into the Function of Monofunctional DNA Glycosylases in the Base Excision Repair Pathway. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2020, 10 (5), e1471. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1471.Search in Google Scholar

36. Dissanayake, U. C.; Roy, A.; Maghsoud, Y.; Polara, S.; Debnath, T.; Cisneros, G. A. Computational Studies on the Functional and Structural Impact of Pathogenic Mutations in Enzymes. Protein Sci. 2025, 34 (4), e70081; https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.70081.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Elsässer, B.; Goettig, P. Mechanisms of Proteolytic Enzymes and their Inhibition in QM/MM Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22 (6), 3232; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22063232.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Šponer, J.; Banáš, P.; Jurečka, P.; Zgarbová, M.; Kührová, P.; Havrila, M.; Krepl, M.; Stadlbauer, P.; Otyepka, M. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Nucleic Acids. From Tetranucleotides to the Ribosome. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5 (10), 1771–1782. https://doi.org/10.1021/jz500557y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. van der Kamp, M. W.; Daggett, V. Molecular Dynamics as an Approach to Study Prion Protein Misfolding and the Effect of Pathogenic Mutations. Prion Proteins; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 169–197.10.1007/128_2011_158Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Osuna, S.; Jiménez-Osés, G.; Noey, E. L.; Houk, K. N. Molecular Dynamics Explorations of Active Site Structure in Designed and Evolved Enzymes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48 (4), 1080–1089. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar500452q.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Fadda, E.; Woods, R. J. Molecular Simulations of Carbohydrates and Protein–Carbohydrate Interactions: Motivation, Issues and Prospects. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15 (15), 596–609; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2010.06.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Shaikh, S. A.; Li, J.; Enkavi, G.; Wen, P.-C.; Huang, Z.; Tajkhorshid, E. Visualizing Functional Motions of Membrane Transporters with Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biochemistry 2013, 52 (4), 569–587. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi301086x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Blomberg, M. R.; Borowski, T.; Himo, F.; Liao, R.-Z.; Siegbahn, P. E. Quantum Chemical Studies of Mechanisms for Metalloenzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (7), 3601–3658; https://doi.org/10.1021/cr400388t.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Himo, F. Recent Trends in Quantum Chemical Modeling of Enzymatic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (20), 6780–6786; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b02671.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Senn, H. M.; Thiel, W. QM/MM Studies of Enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007, 11 (2), 182–187; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.01.684.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Vennelakanti, V.; Nazemi, A.; Mehmood, R.; Steeves, A. H.; Kulik, H. J. Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger: Large-Scale QM and QM/MM for Predictive Modeling in Enzymes and Proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2022, 72, 9–17; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2021.07.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Sousa, S. F.; Ribeiro, A. J. M.; Neves, R. P. P.; Brás, N. F.; Cerqueira, N. M. F. S. A.; Fernandes, P. A.; Ramos, M. J. Application of Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics Methods in the Study of Enzymatic Reaction Mechanisms. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2017, 7 (2), e1281; https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1281.Search in Google Scholar

48. Singh, R. K.; Steyaert, J.; Versées, W. Structural and Biochemical Characterization of the Nucleoside Hydrolase from C. Elegans Reveals the Role of Two Active Site Cysteine Residues in Catalysis. Protein Sci. 2017, 26 (5), 985–996; https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3141.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Mullins, E. A.; Rodriguez, A. A.; Bradley, N. P.; Eichman, B. F. Emerging Roles of DNA Glycosylases and the Base Excision Repair Pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 44 (9), 765–781; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2019.04.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Stockbridge, R. B.; Schroeder, G. K.; Wolfenden, R. The Rate of Spontaneous Cleavage of the Glycosidic Bond of Adenosine. Bioorg. Chem. 2010, 38 (5), 224–228; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2010.05.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Dizdaroglu, M.; Coskun, E.; Jaruga, P. Repair of Oxidatively Induced DNA Damage by DNA Glycosylases: Mechanisms of Action, Substrate Specificities and Excision Kinetics. Mutat. Res., Rev. Mutat. Res. 2017, 771, 99–127; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrrev.2017.02.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Brooks, S. C.; Adhikary, S.; Rubinson, E. H.; Eichman, B. F. Recent Advances in the Structural Mechanisms of DNA Glycosylases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2013, 1834 (1), 247–271; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.10.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Krokan, H. E.; Bjoras, M. Base Excision Repair. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5 (4), a012583; https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a012583.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Wallace, S. S. Base Excision Repair: A Critical Player in Many Games. DNA Repair 2014, 19, 14–26; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.030.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Hwang, Y.; Kang, S.-J.; Kang, J.; Choi, J.; Kim, S.-J.; Jang, S. DNA Repair and Disease: Insights from the Human DNA Glycosylase NEIL Family. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57 (3), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-025-01417-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Piscone, A.; Gorini, F.; Ambrosio, S.; Noviello, A.; Scala, G.; Majello, B.; Amente, S. Targeting the 8-oxodG Base Excision Repair Pathway for Cancer Therapy. Cells 2025, 14 (2), 112; https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14020112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. McCullough, A. K.; Minko, I. G.; Luzadder, M. M.; Zuckerman, J. T.; Vartanian, V. L.; Jaruga, P.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lloyd, R. S. Role of NEIL1 in Genome Maintenance. DNA Repair 2025, 148, 103820; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2025.103820.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Vartanian, V.; Lowell, B.; Minko, I. G.; Wood, T. G.; Ceci, J. D.; George, S.; Ballinger, S. W.; Corless, C. L.; McCullough, A. K.; Lloyd, R. S. The Metabolic Syndrome Resulting from a Knockout of the NEIL1 DNA Glycosylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103 (6), 1864–1869; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507444103.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Scheffler, K.; Bjørås, K. Ø.; Bjørås, M. Diverse Functions of DNA Glycosylases Processing Oxidative Base Lesions in Brain. DNA Repair 2019, 81, 102665; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102665.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. D’Errico, M.; Parlanti, E.; Pascucci, B.; Fortini, P.; Baccarini, S.; Simonelli, V.; Dogliotti, E. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in DNA Glycosylases: From Function to Disease. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2017, 107, 278–291; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.12.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Wang, J.; Li, C.; Han, J.; Xue, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, R.; Radak, Z.; Nakabeppu, Y.; Boldogh, I.; Ba, X. Reassessing the Roles of Oxidative DNA Base Lesion 8-oxoGua and Repair Enzyme OGG1 in Tumorigenesis. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-024-01093-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62. Radak, Z.; Pan, L.; Zhou, L.; Mozaffaritabar, S.; Gu, Y.; Pinho, R. A.; Zheng, X.; Ba, X.; Boldogh, I. Epigenetic and “Redoxogenetic” Adaptation to Physical Exercise. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2024, 210, 65–74; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.11.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Park, K.; Lee, S.; Yoo, H.; Choi, Y. Demeter-Mediated DNA Demethylation in Gamete Companion Cells and the Endosperm, and its Possible Role in Embryo Development in Arabidopsis. J. Plant Biol. 2020, 63 (5), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12374-020-09258-2.Search in Google Scholar

64. Schramm, V. L. Transition States, Analogues, and Drug Development. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8 (1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1021/cb300631k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

65. Jarvis, L. M. Pushing Cancer over the Edge. Chem. Eng. News 2013, 13–18.10.1021/cen-09124-coverSearch in Google Scholar

66. Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Shi, X.; Guo, D.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, W.; Liang, L.; Peng, L.; Hu, J. Research Progress in Human AP Endonuclease 1: Structure, Catalytic Mechanism, and Inhibitors. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2022, 23 (2), 77–88; https://doi.org/10.2174/1389203723666220406132737.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Abramić, M.; Agić, D. Survey of Dipeptidyl Peptidase III Inhibitors: From Small Molecules of Microbial or Synthetic Origin to Aprotinin. Molecules 2022, 27 (9), 3006; https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27093006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

68. Berti, P. J.; McCann, J. A. B. Toward a Detailed Understanding of Base Excision Repair Enzymes: Transition State and Mechanistic Analyses of N-Glycoside Hydrolysis and N-Glycoside Transfer. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106 (2), 506–555; https://doi.org/10.1021/cr040461t.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

69. Wang, S.-D.; Zhang, R.-B.; Eriksson, L. A. Markov State Models Elucidate the Stability of DNA Influenced by the Chiral 5s-Tg Base. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50 (16), 9072–9082. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac691.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

70. Amara, P.; Serre, L.; Castaing, B.; Thomas, A. Insights into the DNA Repair Process by the Formamidopyrimidine-DNA Glycosylase Investigated by Molecular Dynamics. Protein Sci. 2004, 13 (8), 2009–2021; https://doi.org/10.1110/ps.04772404.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Luo, N.; Mehler, E.; Osman, R. Specificity and Catalysis of Uracil DNA Glycosylase. A Molecular Dynamics Study of Reactant and Product Complexes with DNA. Biochemistry 1999, 38 (29), 9209–9220. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi990262h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

72. Sowlati-Hashjin, S.; Wetmore, S. D. Structural Insight into the Discrimination between 8-Oxoguanine Glycosidic Conformers by DNA Repair Enzymes: A Molecular Dynamics Study of Human Oxoguanine Glycosylase 1 and Formamidopyrimidine-DNA Glycosylase. Biochemistry 2018, 57 (7), 1144–1154. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01292.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

73. Olufsen, M.; Smalås, A. O.; Moe, E.; Brandsdal, B. O. Increased Flexibility as a Strategy for Cold Adaptation: A Comparative Molecular Dynamics Study of Cold- and Warm-Active Uracil DNA Glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (18), 18042–18048. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M500948200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

74. Guliaev, A. B.; Hang, B.; Singer, B. Structural Insights by Molecular Dynamics Simulations into Differential Repair Efficiency for Ethano‐a versus Etheno‐a Adducts by the Human Alkylpurine‐DNA N ‐Glycosylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30 (17), 3778–3787. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkf494.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75. Jiang, T.; Monari, A.; Dumont, E.; Bignon, E. Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Clustered Lesion-Induced Impairment of 8-oxoG Recognition by the Human Glycosylase OGG1. Molecules 2021, 26 (21), 6465; https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26216465.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

76. Popov, A. V.; Endutkin, A. V.; Vorobjev, Y. N.; Zharkov, D. O. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Opposite-Base Preference and Interactions in the Active Site of Formamidopyrimidine-DNA Glycosylase. BMC Struct. Biol. 2017, 17 (1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12900-017-0075-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

77. Da, L.-T.; Yu, J. Base-Flipping Dynamics from an Intrahelical to an Extrahelical State Exerted by Thymine DNA Glycosylase during DNA Repair Process. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (11), 5410–5425. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky386.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

78. Peng, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; He, S.; Zhao, X. S.; Huang, X.; Chen, C. Target Search and Recognition Mechanisms of Glycosylase AlkD Revealed by Scanning Fret-Fcs and Markov State Models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117 (36), 21889–21895; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002971117.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

79. Bergonzo, C.; Campbell, A. J.; de los Santos, C.; Grollman, A. P.; Simmerling, C. Energetic Preference of 8-oxoG Eversion Pathways in a DNA Glycosylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (37), 14504–14506. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja205142d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

80. Paligaspe, P.; Samantha, W.; P.D. D.; Senthilnithy, R. Impact of Cd(II) on the Stability of Human Uracil DNA Glycosylase Enzyme; an Implication of Molecular Dynamics Trajectories on Stability Analysis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40 (24), 14027–14034; https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2021.1999329.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Schormann, N.; Ricciardi, R.; Chattopadhyay, D. Uracil-DNA Glycosylases—Structural and Functional Perspectives on an Essential Family of DNA Repair Enzymes. Protein Sci. 2014, 23 (12), 1667–1685; https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.2554.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

82. Frederico, L. A.; Kunkel, T. A.; Shaw, B. R. A Sensitive Genetic Assay for the Detection of Cytosine Deamination: Determination of Rate Constants and the Activation Energy. Biochemistry 1990, 29 (10), 2532–2537. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00462a015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

83. Jiang, Y. L.; Cao, C.; Stivers, J. T.; Song, F.; Ichikawa, Y. The Merits of Bipartite Transition-State Mimics for Inhibition of Uracil DNA Glycosylase. Bioorg. Chem. 2004, 32 (4), 244–262; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2004.03.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

84. Porecha, R. H.; Stivers, J. T. Uracil DNA Glycosylase Uses DNA Hopping and Short-Range Sliding to Trap Extrahelical Uracils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105 (31), 10791–10796; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801612105.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

85. Zharkov, D. O.; Mechetin, G. V.; Nevinsky, G. A. Uracil-DNA Glycosylase: Structural, Thermodynamic and Kinetic Aspects of Lesion Search and Recognition. Mutat. Res., Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2010, 685 (1), 11–20; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.10.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central