Abstract

To celebrate the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ), we discuss how the concept of aromaticity emerges from the postulates of quantum mechanics. Based on this discussion, we analyze the case of cyclo [18]carbon, a molecule that was characterized for the first time in 2019 in a scanning tunneling microscope. From the very beginning, this molecule was classified as an aromatic molecule. In the present work, we challenge this classification and provide arguments to classify this molecule as a non-aromatic species.

Introduction

The United Nations has declared 2025 the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ). 1 In this paper, we contribute to the special issue of the Pure and Applied Chemistry journal that celebrates the IYQ. And we do so by discussing an important property in chemistry, which is aromaticity. In the realm of aromaticity, misunderstandings and disagreements over the definition of aromaticity and the aromatic nature of specific systems are frequent. 2 Despite the abundance of studies, reviews, and conferences published, there is still no universally accepted definition of aromaticity. In these cases, it is useful to resort to the simplest models in which aromaticity could play a role, and from them learn the foundations of the concept before starting to analyze more complex situations.

In a recent publication, Solà and Bickelhaupt 3 compared the solutions of the particle on a ring (POR) and the particle in a box (PIB) simple physical models to demonstrate that the phenomenon of aromaticity is deeply rooted in fundamental quantum mechanics. The particle in the cyclic POR model is more stable than that of the corresponding PIB model for a box and a ring of the same length. The main reasons for this are that the cyclic system has a much more stable lowest-energy eigenvalue and degenerate higher-energy eigenvalues that allow it to hold twice as many particles per “shell” before the subsequent higher-energy eigenfunctions are populated (see Fig. 1). Consequently, a zeroth-order approximation to the so-called aromatic stabilization energy (ASE) is recovered by the POR and PIB model systems. Not only that, but also with the molecular orbital distribution obtained with the POR model, closed-shell electronic structures are obtained with 2, 6, 10, 14… π-electrons, i.e., with 4 N + 2 π-electrons (N = 1, 2, 3…), resulting in the Hückel rule. 4 Moreover, a last shell half-filled with same-spin electrons is reached with 4 N π-electrons leading to aromaticity in the lowest triplet state, which is nothing but the Baird rule. 5 Therefore, the two most important rules of aromaticity 6 can already be derived from the POR model.

Energy levels for a particle in a 1-dimensional box and for a particle on a ring of the same length as the box.

The wavefunction for the POR is completely delocalized and the energy of the ground state is zero (particle at rest with zero kinetic energy), whereas that of the PIB is partially localized and the energy of the ground state is h2/8 mL2 (particle moving even at 0 K). The PIB is stabilized by just closing the two ends of a cage and generating a POR. A given particle delocalized in a closed circuit is more stable than the same particle in an open circuit. This has no classical explanation and can only be understood by applying the laws of quantum mechanics. Therefore, aromaticity is a quantum phenomenon. What we can learn from the comparison between the PIB and POR is that molecular aromaticity is reached when one has energetic stabilization due to electron delocalization in a closed circuit. This conclusion is already contained in what is likely the most widely accepted definition nowadays, which was provided in 2005 by Chen et al. 7 who defined aromaticity as “a manifestation of electron delocalization in closed circuits, either in two or in three dimensions. This results in energy lowering, often quite substantial, and a variety of unusual chemical and physical properties. These include a tendency toward bond length equalization, unusual reactivity, and characteristic spectroscopic features”.

According to our discussion in the preceding paragraphs, it makes sense to focus on the two primary characteristics of aromaticity – aromatic stabilization and electronic delocalization – while classifying the bond length equalization, ring currents (diatropic for aromatic species), and lack of reactivity as secondary features.

The energetic stability of the delocalized structure of cyclic π-conjugated molecules obtained just by being cyclic is one of the most significant features of the aromaticity phenomenon. The ASE is a well-established metric for determining whether cyclic conjugated compounds are aromatic or antiaromatic. 8 Theoretically or empirically, this amount can be obtained from suitable homodesmotic processes. Homodesmotic reactions are a particular case of isodesmic reactions (reactions with equal number of formal single and double bonds in products and reactants) in which there is a same number of bonds between given atoms in each hybridization state in products and reactants. Homodesmotic reactions minimize different sources of errors, like lack of compensation in strain, hyperconjugation, anomeric effects, etc. 9 The main problem in ASE calculations is the choice of appropriate reference molecules. If one can find a suitable reference, the ASE should be provided in aromaticity studies because it is one of the primary properties of (anti)aromatic compounds.

Cyclic delocalization of mobile electrons in closed circuits of two or three dimensions is the second of the key aspects that characterize aromatic compounds. There is no experimental attribute that permits direct measurement of electronic delocalization as it is not an observable and, consequently, there is not a single, generally accepted method to measure this property from a theoretical standpoint. Numerous methods have been devised to ground this idea in theoretically correct quantum mechanics, many of which are based on the electron-pair density. The most used methods to quantify electronic delocalization in aromatic compounds are: 10

The multicenter DI or multicenter electron sharing index (Mc-ESI), the so-called Iring, 11 between the M centers A 1 to A M of a given ring, which is a generalization of the delocalization index (DI) 12 providing a measure of the electron sharing between two atoms in the molecule. And the multicenter index (MCI), which was defined by Bultinck and coworkers 13 using the Iring expression but taking into account all possible permutations of the M atoms in the ring.

The electron localization function (ELF), which has been proved so far a valuable tool to determine the location of electrons pairs. 14 When the ELF value defining a reducible localization domain is increased, this latter is split for a given ELF value giving rise to two new domains sharing a (3,-1) critical point. The ELF value where a domain splits is called a bifurcation point. The ELF value at the bifurcation points can be used as an indirect measure of aromaticity. 15

The electron density of delocalized bonds (EDDB) method, which decomposes the one-electron density (ED) in several ‘layers’ representing different levels of electron delocalization. 16 These layers include the electron density of localized bonds (EDLB), which represents typical (2-center 2-electron) Lewis-like bonds; the density of electrons localized on atoms (EDLA), which represents inner shells, lone pairs, etc.; and EDDB, which represents electron density that cannot be assigned to atoms or bonds because of its (multicenter) delocalized nature.

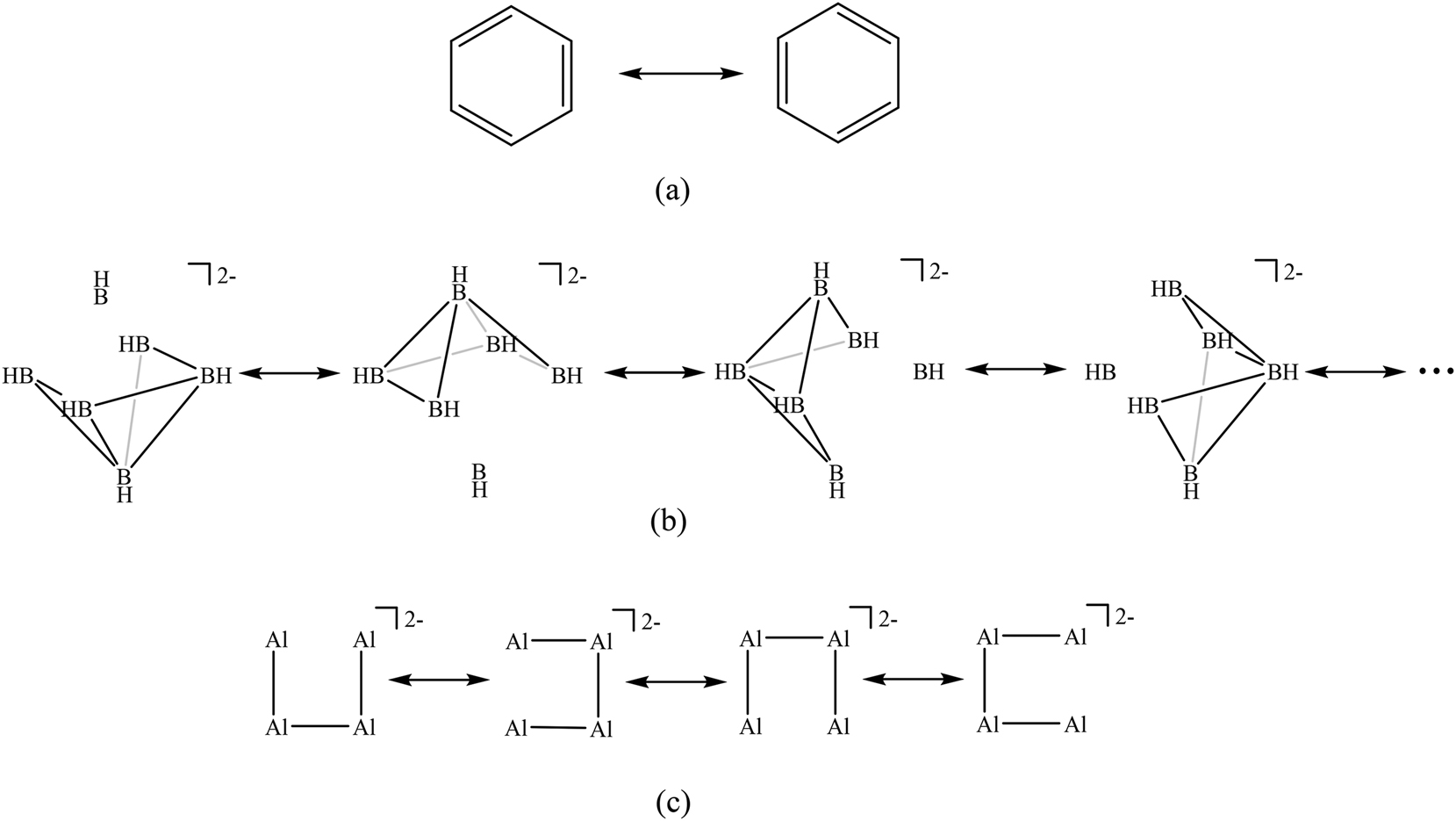

In the Valence Bond language, electron delocalization in closed 2D or 3D circuits, which is a condition for a system to be classified as aromatic, is present in systems that require the use of several resonance structures with similar or equal weights to represent their structure (Fig. 2). The most obvious example is benzene with the two resonance structures depicted in Fig. 2a that are needed to have a good description of the molecule. It is worth mentioning that there is no clear relation between the number of resonance structures and aromaticity. For instance, C60 has 12.500 covalent resonance structures 20 and it is not considered an aromatic molecule. The reason is that a single resonance structure in C60 (that with a radialene-type bonding pattern) describes reasonably well the molecule. Therefore, it is not only the number of resonance structures but also their weights, which should be similar in aromatic compounds.

Same weight resonance structures for (a)benzene with 6π-electrons, (b) B6H6 2− with 14 cage electrons (only 4 out of the 792 possible resonance structures are depicted), and (c) Al4 2− with 14 valence electrons (8 out of 14 valence electrons remain in the 2s orbitals of Al atoms).

C18 as an example

In 1989, cyclo[18]carbon (C18) was generated and detected for the first time with time-of-flight mass spectroscopy. 21 The C18 allotrope has only two-coordinated carbon atoms, as opposed to three-coordinated carbon atoms found in fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, and graphene. It has been consistently shown that C18 exists in the gas phase as a highly reactive species. 22 C18’s high reactivity made it impossible to determine its shape experimentally and prompted multiple quantum-mechanical calculations of its structure. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 Out-of-plane and in-plane π-molecular orbitals (MOs) characterize the two π-conjugated (πin and πout) systems of C18, which contribute differently to its stability. For C18, two symmetric geometries have been taken into consideration: a doubly cumulenic (D18h) and a D9h polyynic structure with alternating single and triple bonds or, preferably, alternating short and long bonds. 28 Kaiser et al. 29 in 2019 used high-resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM) to analyze C18 and their results supported the polyynic structure of C18 on the NaCl surface. From a theoretical point of view, most DFT calculations of C18 predict the D18h symmetry 23 whereas the Hartree–Fock (HF) and Coupled Cluster methods give the D9h structure, 24 , 25 the D18h structure being a transition state between two D9h species with a barrier of ca. 10 kcal/mol. 26 , 30 The coupled cluster method predicts a polyynic structure of C18 with bond lengths of 1.238 and 1.383 Å. 25 Increasing the amount of the exact HF exchange in a DFT functional stabilizes the correct polyynic structure comparing to the cumulenic one. 27

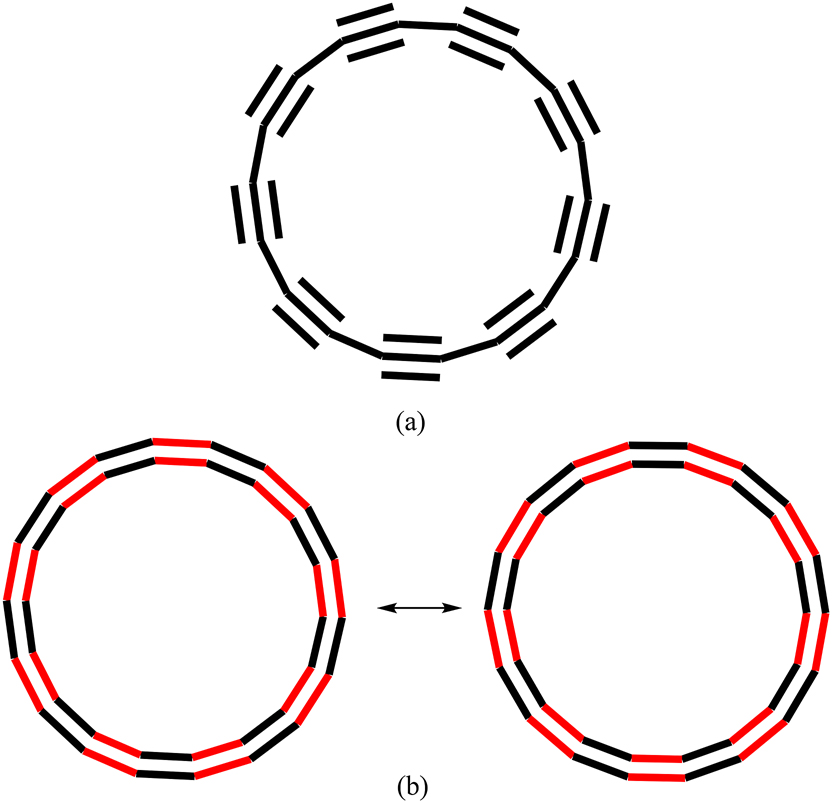

The aromaticity of C18 has been computationally analyzed in several works. 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 All these studies focused on the calculated magnetic measures of aromaticity such as the nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS) and ring currents with few exceptions. 28 , 32 Ring currents indicate that D9h polyynic and D18h cumulenic structures of C18 are both diatropic, and, consequently, aromatic. Indeed, the cumulenic and polyynic structures are classified as double aromatic with two orthogonal π-systems of 18 π-electrons each, although some authors point out that bond-length alternating polyynic structure is less aromatic than the non-alternating transition state structure. 30 For the D18h cumulenic structure of C18, there are two resonance structures of the same weight, which seems to support its aromatic character (Fig. 3b). However, for the D9h polyynic structure of C18, one does not need more than a single resonance structure to have a reasonable representation of the molecule (Fig. 3a). Therefore, the conclusion that the D9h polyynic structure of C18 is aromatic is surprising because the π-electrons are localized in the triple bonds and not delocalized through the whole ring. If there is no π-delocalization, there is no aromaticity.

Main resonance structures for (a) D9h polyynic and (b) D18h cumulenic structures (red πin and black πout) of C18.

As said before, ring currents should be considered a secondary characteristic of aromaticity. To make more reliable conclusions about the aromaticity of a given system, one should compute the ASE and/or analyze the electron delocalization. As in many other molecules, the calculation of the ASE in C18 is not easy because the lack of a clear system of reference (although calculation of extra cyclic resonance energy (ECREπ) shows residual stabilization in C18 33 ). However, the electron delocalization can be easily computed using the EDDB method (calculation of Iring or MCI is not affordable for rings of this size). A previous work 28 has analyzed the electron delocalization with the ELF and LOL functions, but still the conclusion mainly based on the ring current was that C18 is a doubly aromatic molecule.

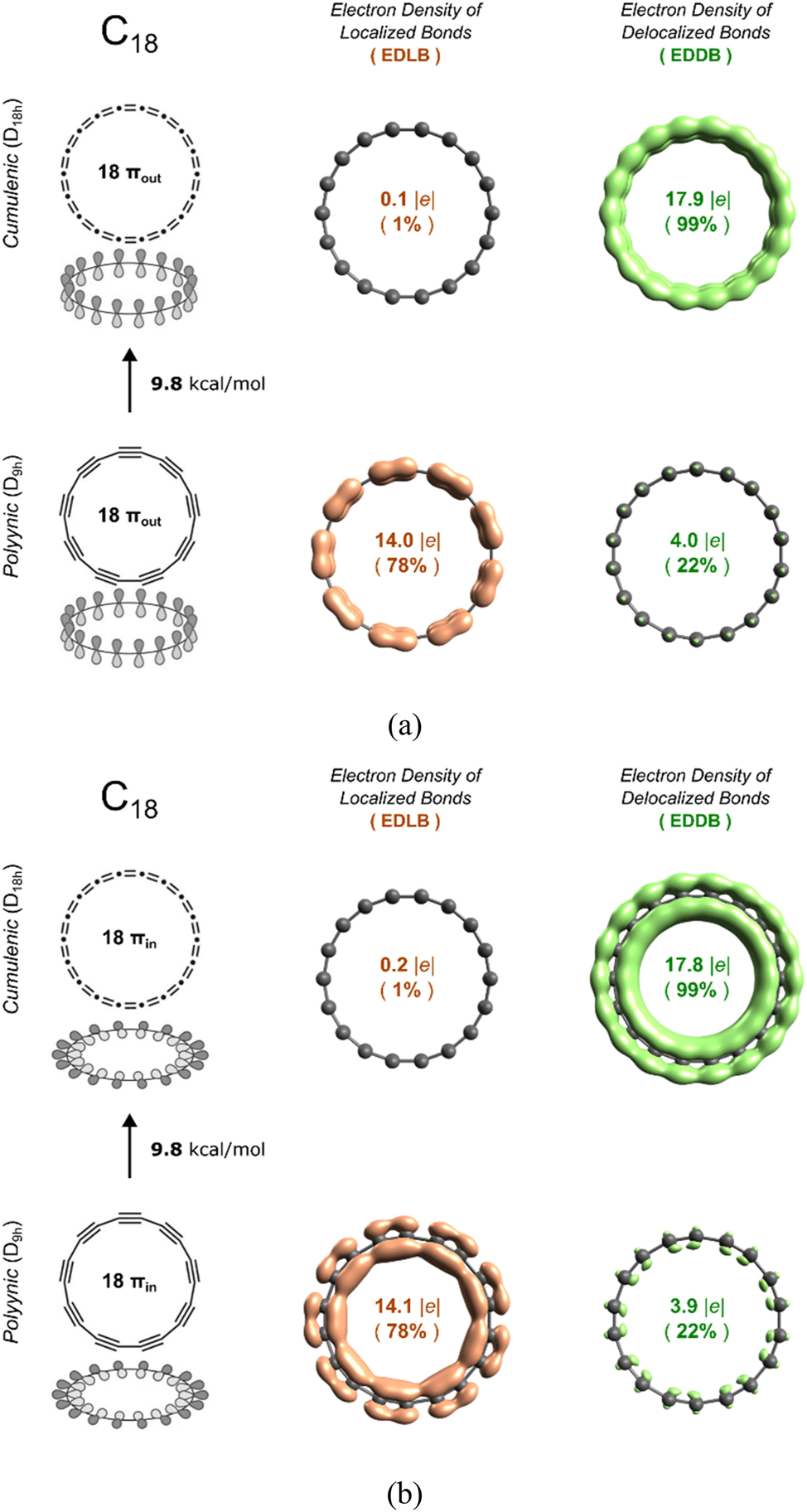

The EDDB results obtained with the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS//ωB97M-V/def2-QZVPP method are shown in Fig. 4. At this level of theory, the polyynic structure is more stable than the cumulenic one by 9.8 kcal/mol (T1diag < 0.014). The total π-electron population is separated into the π-electrons in localized bonds (EDLB) and the delocalized π-electrons (EDDB). Let us discuss first the D18h cumulenic structure. As can be seen in Fig. 4, both the πout and πin systems have ca. 18 delocalized electrons (99 % of the total population of electrons in the π-cloud is delocalized). Therefore, from an electronic viewpoint, the D18h cumulenic structure, i.e. the transition structure between two D9h polyynic structures, could to be considered aromatic. If we now move to the D9h polyynic structure, we find that about 14 electrons are localized in both the πout and πin systems, that is a 78 % of the π-electrons are localized in the short bonds of the D9h C18 species. Only 22 % of the electrons (about 4 e) are delocalized. Such a small percentage indicates prevalence of a single resonance form and hence lack of aromaticity. Admittedly, there is some conjugation effect, typical for acyclic systems (like for instance in 1,3-butadiyne), that makes the formal triple (single) bonds longer (shorter) than expected, but it is obviously not enough to claim aromaticity in the polyynic structure of C18.

EDLB and EDDB results for (a) the πout system of D18h cumulenic and D9h polyynic structures and (b) the πin system of D18h cumulenic and D9h polyynic structures.

Based on the mere fact that the delocalized cumulenic structure of C18 has significantly higher electronic energy than the localized polyynic one can conclude that electron delocalization in C18 is not associated with aromatic stabilization effect, and thus such species should be classified as non-aromatic. But which are the physical reasons for the higher stabilization of the localized polyynic structure of C18 as compared to the delocalized cumulenic structure? As shown in the POR model, under the periodic boundary conditions hypothetical non-interacting particles prefer the delocalized situation because of the reduction in their kinetic energy. In molecular rings, a uniform distribution of electrons in the π-cloud and the resulting kinetic energy decrease are associated with a much tighter electron binding effect due to increased Coulomb interactions between electrons and the cyclically arranged nuclei. This extra stabilization of cyclic over acyclic molecular topology is particularly important in small systems, where it determines the specific (delocalized) bonding pattern and lower reactivity. However, in larger molecular rings, the extra stability due to uniform distribution of charge and coherence of the wavefunction is counterbalanced by the extra cost of the exchange correlation between electrons of the same spin, which is distortive in nature. In other words, the more cyclically delocalized π-electrons in the ring, the higher the cost of the exchange-correlation at large distances, 34 and, at some point, breaking the symmetry and localizing π-bonds is the best way to minimize these destabilizing interactions (cf. the second-order Jahn–Teller effect in C18). 35 This effect is also present in annulenes, C n H n . 36 , 37 When n increases, the ASE decreases and starting from n ≈ 34, the ASE value is less than 1 kJ/mol, 37 not enough to consider these species aromatic. Then, it is not surprising that a species like C18 with 36 π-electrons prefers the localized to the delocalized structure. For this reason, C18 has to be classified as a non-aromatic molecule. This conclusion is in line with a recent study by Baranac-Stojanović 33 on cyclo [2n]carbons (n = 3 – 12), where the author concluded that starting from n = 8, the πin and πout systems are nearly localized and energetically almost unaffected by (anti)aromaticity.

Conclusions

As happens with many other important concepts in chemistry, aromaticity is not well defined. However, it is a phenomenon deeply rooted in fundamental quantum mechanics, as can be demonstrated by solving the Schrödinger equation for the particle in a box and particle on a ring models. In this contribution, we consider that aromatic compounds are those species that are stabilized because of their electronic delocalization in closed 2D or 3D circuits. If we take this definition as granted, then the C18 molecule has to be considered a non-aromatic molecule, in contradiction with a number of studies that consider this molecule aromatic based on magnetic criteria. Finally, it is worth noting that the conclusion whether C18 is aromatic or not depends on the definition of aromaticity. This is why, we consider it important to revise and update the current IUPAC definition of aromaticity. 38

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021SGR623

Award Identifier / Grant number: ICREA Academia prize 2024 to M.S.

Funding source: Infrastruktura PL-Grid

Award Identifier / Grant number: PLG/2024/017801

Funding source: Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades

Award Identifier / Grant number: PID2023-147424NB-I00

Funding source: Narodowe Centrum Nauki

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021/42/E/ST4/00332

Acknowledgments

M.S. thanks the financial support from the Agencia Española de Investigación (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) for project PID2023-147424NB-I00 and from the Generalitat de Catalunya for Project 2021SGR623 and ICREA Academia prize 2024 to M.S. D.W.S. acknowledges financial support from the National Science Centre, Poland (2021/42/E/ST4/00332) and Polish high-performance computing infrastructure PLGrid (HPC Center: ACK Cyfronet AGH) for providing computer facilities and support within computational grant no. PLG/2024/017801.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Agencia Española de Investigación (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) project PID2023- 147424NB-I00 Generalitat de Catalunya Project 2021SGR623 and ICREA Academia prize 2024 to M.S. National Science Centre, Poland Project 2021/42/E/ST4/00332 Polish high-performance computing infrastructure PLGrid Project PLG/2024/017801.

-

Data availability: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

1. International Year of Quantum Science and Technology. https://quantum2025.org/ (Accessed 2025-3-8).Search in Google Scholar

2. Balaban, A. T. Is Aromaticity Outmoded? Pure & Appl. Chem. 1980, 52, 1409–1429; https://doi.org/10.1351/pac198052061409.a. Binsch, G. Aromaticity – An exercise in chemical futility? Naturwissenschaften 1973, 60, 369–374; https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00602510.b. Krygowski, T. M.; Cyrański, M. K.; Czarnocki, Z.; Häfelinger, G.; Katritzky, A. R. Aromaticity: a Theoretical Concept of Immense Practical Importance. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 1783–1796; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4020(99)00979-5.c. Lloyd, D. What is aromaticity? J. Chem. Inf. Comp. Sci. 1996, 36, 442–447; https://doi.org/10.1021/ci950158g.d. Solà, M. Why Aromaticity Is a Suspicious Concept? Why? Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 22; https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2017.00022.e. Hoffmann, R. The Many Guises of Aromaticity. Am. Sci. 2015, 103, 18–22; https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.112.18.f. Frenking, G.; Krapp, A. Unicorns in the world of chemical bonding models. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 15–24; https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20543.Search in Google Scholar

3. Solà, M.; Bickelhaupt, F. M. Particle on a Ring Model for Teaching the Origin of the Aromatic Stabilization Energy and the Hückel and Baird Rules. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 3497–3501; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.2c00523.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Hückel, E. Quanstentheoretische Beiträge zum Benzolproblem II. Quantentheorie der induzierten Polaritäten. Z. Physik 1931, 72, 310–337; https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01341953.a. Hückel, E. Quantentheoretische Beiträge zum Problem der aromatischen und ungesättigten Verbindungen. III. Z. Physik 1932, 76, 628–648; https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01341936.b. Hückel, E. The theory of unsaturated and aromatic compounds. Z. Elektrochemie 1937, 43 (752-788), 827–849; https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19370431016.c. Doering, W. V. E.; Detert, F. L. Cycloheptatrienylium oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 876–877; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01146a537.Search in Google Scholar

5. Baird, N. C. Quantum organic photochemistry. II. Resonance and aromaticity in the lowest 3ππ* state of cyclic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 4941–4948; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00769a025.a. Ottosson, H. Organic photochemistry: Exciting excited-state aromaticity. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 969–971; https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1518.b. Karas, L. J.; Wu, J. I. Baird’s rules at the tipping point. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 723–725; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-022-00988-z.Search in Google Scholar

6. Solà, M. Aromaticity rules. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 585–590; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-022-00961-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Chen, Z.; Wannere, C. S.; Corminboeuf, C.; Puchta, R.; Schleyer, P. v. R. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts (NICS) as an Aromaticity Criterion. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842–3888; https://doi.org/10.1021/cr030088+.10.1021/cr030088+Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Solà, M.; Boldyrev, A. I.; Cyrański, M. K.; Krygowski, T. M.; Merino, G. Descriptors of Aromaticity: Energetic Criteria In Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity: Concepts and Applications; Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 2023; pp. 111–130.a. Cyrański, M. K. Energetic Aspects of Cyclic π-electron Delocalization: Evaluation of the Methods of Estimating Aromatic Stabilization Energies. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3773–3811; https://doi.org/10.1021/cr0300845.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Cyrański, M. K.; Schleyer, P. v. R.; Krygowski, T. M.; Jiao, H.; Hohlneicher, G. Facts and artifacts about aromatic stability estimation. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 1657–1665; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4020(03)00137-6.a. Cyrański, M. K.; Krygowski, T. M.; Katritzky, A. R.; Schleyer, P. v. R. To what extent can aromaticity be defined uniquely? J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 1333–1338; https://doi.org/10.1021/jo016255s.Search in Google Scholar

10. Solà, M.; Boldyrev, A. I.; Cyrański, M. K.; Krygowski, T. M.; Merino, G. Descriptors of Aromaticity: Electronic Criteria In Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity: Concepts and Applications; Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 2023; pp. 145–192.10.1002/9781119085928Search in Google Scholar

11. Giambiagi, M.; de Giambiagi, M. S.; Mundim, K. C. Definition of a multicenter bond index. Struct. Chem. 1990, 1, 423–427; https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00671228.Search in Google Scholar

12. Bader, R. F. W.; Streitwieser, A.; Neuhaus, A.; Laidig, K. E.; Speers, P. Electron delocalization and the Fermi hole. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4959–4965; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja953563x.a. Fradera, X.; Austen, M. A.; Bader, R. F. W. The Lewis model and beyond. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 304–314; https://doi.org/10.1021/jp983362q.b. Fradera, X.; Poater, J.; Simon, S.; Duran, M.; Solà, M. Electron-pairing analysis from localization and delocalization indices in the framework of the atoms-in-molecules theory. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2002, 108, 214–224; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-002-0375-5.Search in Google Scholar

13. Bultinck, P.; Ponec, R.; Van Damme, S. Multicenter bond indices as a new measure of aromaticity in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 706–718; https://doi.org/10.1002/poc.922.Search in Google Scholar

14. Savin, A.; Nesper, R.; Wengert, S.; Fassler, T. F. ELF: The electron localization function. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1809–1832; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199718081.a. Feixas, F.; Matito, E.; Duran, M.; Solà, M.; Silvi, B. Electron Localization Function at the Correlated Level: A Natural Orbital Formulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 2736–2742; https://doi.org/10.1021/ct1003548.b. Poater, J.; Duran, M.; Solà, M.; Silvi, B. Theoretical Evaluation of Electron Delocalization in Aromatic Molecules by Means of Atoms in Molecules (AIM) and Electron Localization Function (ELF) Topological Approaches. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3911–3947; https://doi.org/10.1021/cr030085x.Search in Google Scholar

15. Santos, J. C.; Andres, J.; Aizman, A.; Fuentealba, P. An Aromaticity Scale Based on the Topological Analysis of the Electron Localization Function Including σ and π contributions. J, Chem. Theor. Comput. 2005, 1, 83–86; https://doi.org/10.1021/ct0499276.a. Santos, J. C.; Tiznado, W.; Contreras, R.; Fuentealba, P. Sigma-pi separation of the electron localization function and aromaticity. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 1670–1673; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1635799.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Szczepanik, D. W. A new perspective on quantifying electron localization and delocalization in molecular systems. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2016, 1080, 33–37; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2016.02.003.a. Szczepanik, D. W.; Andrzejak, M.; Dominikowska, J.; Pawełek, B.; Krygowski, T. M.; Szatylowicz, H.; Solà, M. The electron density of delocalized bonds (EDDB) applied for quantifying aromaticity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 28970–28981; https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CP06114E.b. Szczepanik, D. W.; Andrzejak, M.; Dyduch, K.; Żak, E.; Makowski, M.; Mazur, G.; Mrozek, J. A uniform approach to the description of multicenter bonding. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20514–20523; https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CP02932A.Search in Google Scholar

17. Poater, J.; Fradera, X.; Duran, M.; Solà, M. The Delocalization Index as an Electronic Aromaticity Criterion. Application to a Series of Planar Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Chem. Eur. J. 2003, 9, 400–406; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200390041.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Matito, E.; Duran, M.; Solà, M. The aromatic fluctuation index (FLU): A new aromaticity index based on electron delocalization. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 014109; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1824895.a. Matito, E.; Duran, M.; Solà, M. Erratum: “The aromatic fluctuation index (FLU): A new aromaticity index based on electron delocalization”. [J. Chem Phys. 122, 014109 (2005)]. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2222352.b. Matito, E.; Salvador, P.; Duran, M.; Solà, M. Aromaticity Measures from Fuzzy-Atom Bond Orders. The Aromatic Fluctuation (FLU) and the para-Delocalization (PDI) Indexes. J. Phys. Chem. A2006, 110, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp057387i.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Matta, C. F.; Hernández-Trujillo, J. Bonding in Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Terms of the Electron Density and of Electron Delocalization. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 7496–7504; https://doi.org/10.1021/jp034952d.a. Matta, C. F.; Hernández-Trujillo, J. Erratum to ′′Bonding in Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Terms of the Electron Density and of Electron Delocalization. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 10798; https://doi.org/10.1021/jp055864r.Search in Google Scholar

20. Shanbogh, P. P.; Sundaram, N. G. Fullerenes revisited. Reson. 2015, 20, 123–135; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12045-015-0160-0.Search in Google Scholar

21. Diederich, F.; Rubin, Y.; Knobler, C. B.; Whetten, R. L.; Schriver, K. E.; Houk, K. N.; Li, Y. All-Carbon Molecules: Evidence for the Generation of Cyclo[18]carbon from a Stable Organic Precursor. Science 1989, 245, 1088–1090; https://doi.org/10.1126/science.245.4922.1088.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Diederich, F.; Rubin, Y. Synthetic Approaches toward Molecular and Polymeric Carbon Allotropes. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 1101–1123; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199211013.a. Diederich, F.; Kivala, M. All-carbon scaffolds by rational design. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 803–812; https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200902623.b. Anderson, H. L.; Patrick, C. W.; Scriven, L. M.; Woltering, S. L. A. Short History of Cyclocarbons. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 94, 798–811; https://doi.org/10.1246/bcsj.20200345.c. Pooja; Yadav, S.; Pawar, R. Chemistry of Cyclo[18]Carbon (C18): A Review. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202400055; https://doi.org/10.1002/tcr.202400055.Search in Google Scholar

23. Parasuk, V.; Almlof, J.; Feyereisen, M. W. The [18] all-carbon molecule: cumulene or polyacetylene? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1049–1050; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00003a052.a. Neiss, C.; Trushin, E.; Görling, A. The Nature of One-Dimensional Carbon: Polyynic versus Cumulenic. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 2497–2502; https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201402266.b. Hutter, J.; Luethi, H. P.; Diederich, F. Structures and vibrational frequencies of the carbon molecules C2-C18 calculated by density functional theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 750–756; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00081a041.Search in Google Scholar

24. Torelli, T.; Mitas, L. Electron Correlation in C4N+2 Carbon Rings: Aromatic versus Dimerized Structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 1702–1705; https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.1702.a. Plattner, D. A.; Houk, K. N. C18 Is a Polyyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 4405–4406; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00120a026.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Arulmozhiraja, S.; Ohno, T. CCSD calculations on C14, C18, and C22 carbon clusters. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 114301; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2838200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Baryshnikov, G. V.; Valiev, R. R.; Nasibullin, R. T.; Sundholm, D.; Kurten, T.; Ågren, H. Aromaticity of Even-Number Cyclo[n]carbons (n = 6–100). J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 10849–10855; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.0c09692.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Stasyuk, A. J.; Stasyuk, O. A.; Solà, M.; Voityuk, A. A. Cyclo[18]carbon: the smallest all-carbon electron acceptor. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 352–355; https://doi.org/10.1039/C9CC08399E.a. Stasyuk, A. J.; Stasyuk, O. A.; Solà, M.; Voityuk, A. A. Correction: Cyclo[18]carbon: the smallest all-carbon electron acceptor. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1302; https://doi.org/10.1039/D0CC90021D.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Liu, Z.; Lu, T.; Chen, Q. An sp-hybridized all-carboatomic ring, cyclo[18]carbon: Bonding character, electron delocalization, and aromaticity. Carbon 2020, 165, 468–475; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2020.04.099.Search in Google Scholar

29. Kaiser, K.; Scriven, L. M.; Schulz, F.; Gawel, P.; Gross, L.; Anderson, H. L. An sp-hybridized molecular carbon allotrope, cyclo[18]carbon. Science 2019, 365, 1299–1301; https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay1914.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Baryshnikov, G. V.; Valiev, R. R.; Kuklin, A. V.; Sundholm, D.; Ågren, H. Cyclo[18]carbon: Insight into Electronic Structure, Aromaticity, and Surface Coupling. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 6701–6705; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b02815.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Dai, C.; Chen, D.; Zhu, J. Achieving Adaptive Aromaticity in Cyclo[10]carbon by Screening Cyclo[n]carbon (n=8−24). Chem.–Asian J. 2020, 15, 2187–2191; https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.202000528.a. Charistos, N. D.; Muñoz-Castro, A. Induced magnetic field in sp-hybridized carbon rings: analysis of double aromaticity and antiaromaticity in cyclo[2N]carbon allotropes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 9240–9249; https://doi.org/10.1039/D0CP01252A.b. Fowler, P. W.; Mizoguchi, N.; Bean, D. E.; Havenith, R. W. A. Double Aromaticity and Ring Currents in All-Carbon Rings. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 6964–6972; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200900322.c. Pan, C.; Liu, Z. Intermolecular Interaction, Electronic Structure and Aromaticity of Possible Dimers of Cyclo[18]Carbon (C18). ChemPhysChem 2025, e202400912; https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.202400912.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Kozáková, S.; Alharzali, N.; Černušák, I. Cyclo[n]carbons and catenanes from different perspectives: disentangling the molecular thread. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 29386–29403; https://doi.org/10.1039/D3CP03887D.Search in Google Scholar

33. Baranac-Stojanović, M. (Anti)aromaticity of cyclo[2n]carbons (n = 3 – 12). Chem.–Asian J. 2025, e202500295; https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.202500295.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Szczepanik, D. W.; Solà, M.; Andrzejak, M.; Pawelek, B.; Dominikowska, J.; Kukułka, M.; Dyduch, K.; Krygowski, T. M.; Szatylowicz, H. The Role of the Long-Range Exchange Corrections in the Description of Electron Delocalization in Aromatic Species. J. Comput. Chem. 2017, 38, 1640–1654; https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.24805.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Pereira, Z. S.; da Silva, E. Z. Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking in Cyclo[18]Carbon. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 1152–1157; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.9b11822.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Jirásek, M.; Rickhaus, M.; Tejerina, L.; Anderson, H. L. Experimental and Theoretical Evidence for Aromatic Stabilization Energy in Large Macrocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2403–2412; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c12845.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Van Nyvel, L.; Alonso, M.; Solà, M. Effect of size, charge, and spin state on Hückel and Baird aromaticity in [N]annulenes. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 5613–5622; https://doi.org/10.1039/D4SC08225G.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. McNaught, A. D.; Wilkinson, A. The IUPAC compendium of chemical terminology; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, 1997. Online version (2019-) created by Chalk, S. J. https://doi.org/10.1351/goldbook.A00442/ (accessed 2025-3-8).Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 IUPAC & De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Acid dissociation constants in selected dipolar non-hydrogen-bond-donor solvents (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Preface

- Introduction to the Special Issue of “The International Year of Quantum”

- Review Articles

- Quantum chemistry of molecules in solution. A brief historical perspective

- From Hückel to Clar: a block-localized description of aromatic systems

- Exploring potential energy surfaces

- Unlocking the chemistry facilitated by enzymes that process nucleic acids using quantum mechanical and combined quantum mechanics–molecular mechanics techniques

- Hypothetical heterocyclic carbenes

- Is relativistic quantum chemistry a good theory of everything?

- When theory came first: a review of theoretical chemical predictions ahead of experiments

- Research Articles

- Exploring reaction dynamics involving post-transition state bifurcations based on quantum mechanical ambimodal transition states

- Molecular aromaticity: a quantum phenomenon

- Using topology for understanding your computational results

- The role of ion-pair on the olefin polymerization reactivity of zirconium bis(phenoxy-imine) catalyst: quantum mechanical study and its beyond

- Theoretical insights on the structure and stability of the [C2, H3, P, O] isomeric family

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Acid dissociation constants in selected dipolar non-hydrogen-bond-donor solvents (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Preface

- Introduction to the Special Issue of “The International Year of Quantum”

- Review Articles

- Quantum chemistry of molecules in solution. A brief historical perspective

- From Hückel to Clar: a block-localized description of aromatic systems

- Exploring potential energy surfaces

- Unlocking the chemistry facilitated by enzymes that process nucleic acids using quantum mechanical and combined quantum mechanics–molecular mechanics techniques

- Hypothetical heterocyclic carbenes

- Is relativistic quantum chemistry a good theory of everything?

- When theory came first: a review of theoretical chemical predictions ahead of experiments

- Research Articles

- Exploring reaction dynamics involving post-transition state bifurcations based on quantum mechanical ambimodal transition states

- Molecular aromaticity: a quantum phenomenon

- Using topology for understanding your computational results

- The role of ion-pair on the olefin polymerization reactivity of zirconium bis(phenoxy-imine) catalyst: quantum mechanical study and its beyond

- Theoretical insights on the structure and stability of the [C2, H3, P, O] isomeric family