Abstract

We report a local description of extended aromatic systems using Clar formalism embedded in Valence Bond-like calculations. We disclose a new implementation of our HuLiS (Hückel/Lewis) program that considers blocks of electrons in addition to bonds and lone pairs/radical centers. The method is based on the Hückel approximation for both the empirical hamiltonian and the atomic orbital orthogonality constraint.

Introduction

The aromaticity/anti-aromaticity concept is founded on the cases of the isolated rings conjugated carbon atoms, essentially benzene and cyclobutadiene. 1 According to Hückel’s rule, aromatic systems are cyclic, planar, π-conjugated structures with 4n + 2 π electrons, while antiaromatic systems have 4n π electrons. However, the situation becomes more nuanced when addressing excited states, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 or polycyclic systems, particularly when a mixture of ring sizes and/or when non-planar cases are considered. 6 Of course, variation on the atom type (using for instance boron and nitrogen atoms) can enrich the question. 7

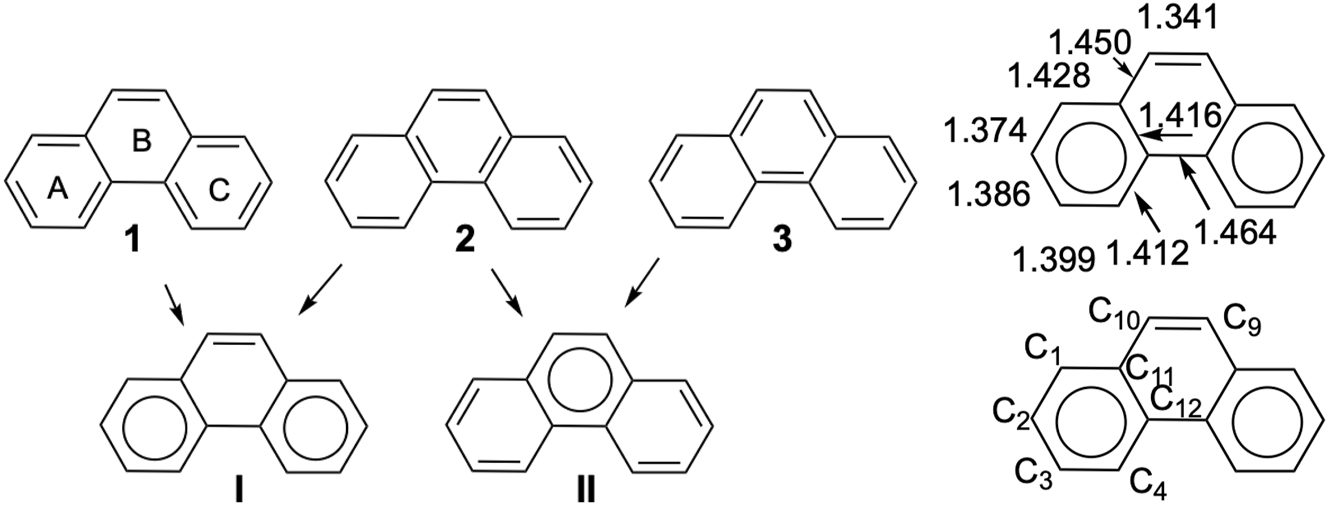

In this work, we focus on planar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in their ground states, composed of fused regular hexagonal carbon rings. 8 In the 1950s, Clar introduced a powerful and intuitive formalism to describe aromaticity in PAHs through the concept of local aromatic sextets, 9 which has since become a useful visual tool. 10 Clar’s formalism is best illustrated with phenanthrene, which topology allows five Kekulé structures. Three of them (1, 2, 3) are represented in Fig. 1. They can be combined to form Clar structures with one or two aromatic sextets. In this specific system, X-ray diffraction data 11 support the predominance of the structure with sextets on the terminal rings (structure I), consistent with Clar’s rule: the most representative structure maximizes the number of aromatic sextets.

Phenanthrene’s localized structures and X-ray parameters (in Å). 11

Beyond structural reasoning, aromaticity primarily reflects an energetic stabilization beyond conjugation. 12 , 13 Homodesmic and isodesmic reaction schemes have long been used to quantify resonance energies and isolate the aromatic contribution. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 The localized wavefunction methods have been used to describe aromatic systems to better understand their nature and evaluate the associated energies, for benzene essentially. 15 , 18 , 19 , 20 This idea of energetic stabilization is also central to methods derived from graph theoretical formalism, whereby tentative energetical descriptors like the topological resonance energy (TRE), 21 , 22 ring resonance energy (RRE) 23 and their generalization 24 have been proposed. Besides, graph theoretical methods can also provide useful qualitative and numerical criteria such as Ring Bond Order derived from simple counts of Kekulé structures involved in aromatic sextets. 25 , 26

Since the 1990s, new aromaticity descriptors have been introduced, including magnetic criteria such as NICS (Nucleus Independent Chemical Shifts), 27 , 28 ACID (Anisotropy of the Current Induced Density), 29 GIMIC (Gauge Including Magnetically Induced Current), 30 induced magnetic field (B ind ), 31 geometrical indices like HOMA (Harmonic Oscillator Model of Aromaticity), 32 or electronic as PDI (Para Delocalization Index). 33 They complement the (4n + 2) Hückel/Clar topological indicator. A system or a ring in a system is no longer “aromatic”, “nonaromatic”, or “antiaromatic”, but its aromaticity is evaluated locally. 34 In other words, aromaticity leaves the True/False boolean evaluation that was amenable with the 4n + 2 rule, to numerical indicators that can apply either to a specific ring or to the whole molecule. Finally, one can consider that the last breakthrough in this topic so far comes from maps in 2D or 3D, associated with the aromaticity/antiaromaticity of a molecule, which can even be distorted. 6 , 35 , 36 , 37

In this contribution, we are interested in the Clar description of the aromaticity from a wavefunction point of view. We adapted our Hückel-Lewis (HuLiS) code 38 , 39 , 40 to be able to consider aromatic sextets in an approximated wavefunction. With the Clar view of the aromaticity in HuLiS, we obtain the weights of the components in the Huckel Hamiltonian framework. This quest for the weights of localized structures is somehow as old as aromaticity: Pauling and Wheland back in 1933 already discussed the weights of Kekulé vs. Dewar structures in benzene. 12 Our scheme will be applied to standard Clar cases, and the results will be compared with ab initio calculations whenever feasible.

Computational details

Hückel-Lewis projection scheme (HLP)

The details about the HLP algorithms have been published elsewhere, 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 and the block definition does not change the general strategy. We shall only outline the algorithm that produces the Ψ HLP wavefunction in the HuLiS-Clar context. Ψ HLP corresponds to the wavefunction of the resonant hybrid, written as a linear combination of local structures (named |ψ i ⟩), that can include Clar sextets (see eq. 1). In the end, the coefficients can be used to calculate the Coulson-Chirgwin weights 42 for each |ψ i ⟩, labeled w i in (2).

The coefficients of the |Ψ HLP ⟩ expansion must be chosen in such a way that the HLP expansion resembles the reference state; here, it is the delocalized Hückel wavefunction: |Ψ HLP ⟩ ≃ |Ψ Deloc ⟩. This is defined in (the un-normalized) eq. 3, where c ϵ |ψ ϵ ⟩ is considered as the part that misses in |Ψ HLP ⟩. Moreover, we assume that this missing part is orthogonal to each localized structure of the |Ψ HLP ⟩ expansion. Hopefully, c ϵ is small, but not necessarily, due to the orthogonality assumption. Finally, projecting |Ψ Deloc ⟩ onto each Lewis structure |ψ i ⟩, and using (1) together with (3), we obtain a system of linear eq. 4 that requires only the computation of overlaps: those between localized structures ⟨ψ i |ψ j ⟩, and those with |Ψ Deloc ⟩. A trust factor, τ, is also obtained (5), the closer τ to 1, the better. The overlaps are easily computed in the Hückel framework, thanks to the AO’s orthogonality (see Appendix I and II). Moreover, there are no restrictions against the use of this scheme with ab initio multiconfigurational wavefunctions, and we did it a few years ago. 43 Other similar methods have been implemented for ab initio wavefunctions, with Hartree–Fock, 44 or MC-SCF delocalized wavefunctions. 45 , 46

The modifications made in the HuLiS program only concern the localization constraint which evolves from the strict Lewis description with bonds and lone pairs, to blocks of n electrons on m centres. Hence, we build wavefunctions from chemical drawings, much like the Block-Localized Wavefunction (BLW) approach, to provide a chemically intuitive representation of bonding. 47 As such, an aromatic sextet is described as a block of 6 electrons on 6 carbon atoms. The block definition encompasses the bond and lone pairs definition: bonds are blocks of 2 electrons on 2 centres, and lone pairs are blocks of 2 electrons on 1 centre. Our implementation allows singlet coupling between two odd electrons to build singlet biradicals. The current version does not handle properly degenerated states for the reference Hückel delocalized wavefunction.

Clar structures and computations

Valence Bond wavefunction can be defined strictly on atoms, with non-orthogonal atomic orbitals, 48 but there exists a number of approaches where the orbitals are allowed to delocalize on the neighbor atoms. 49 , 50

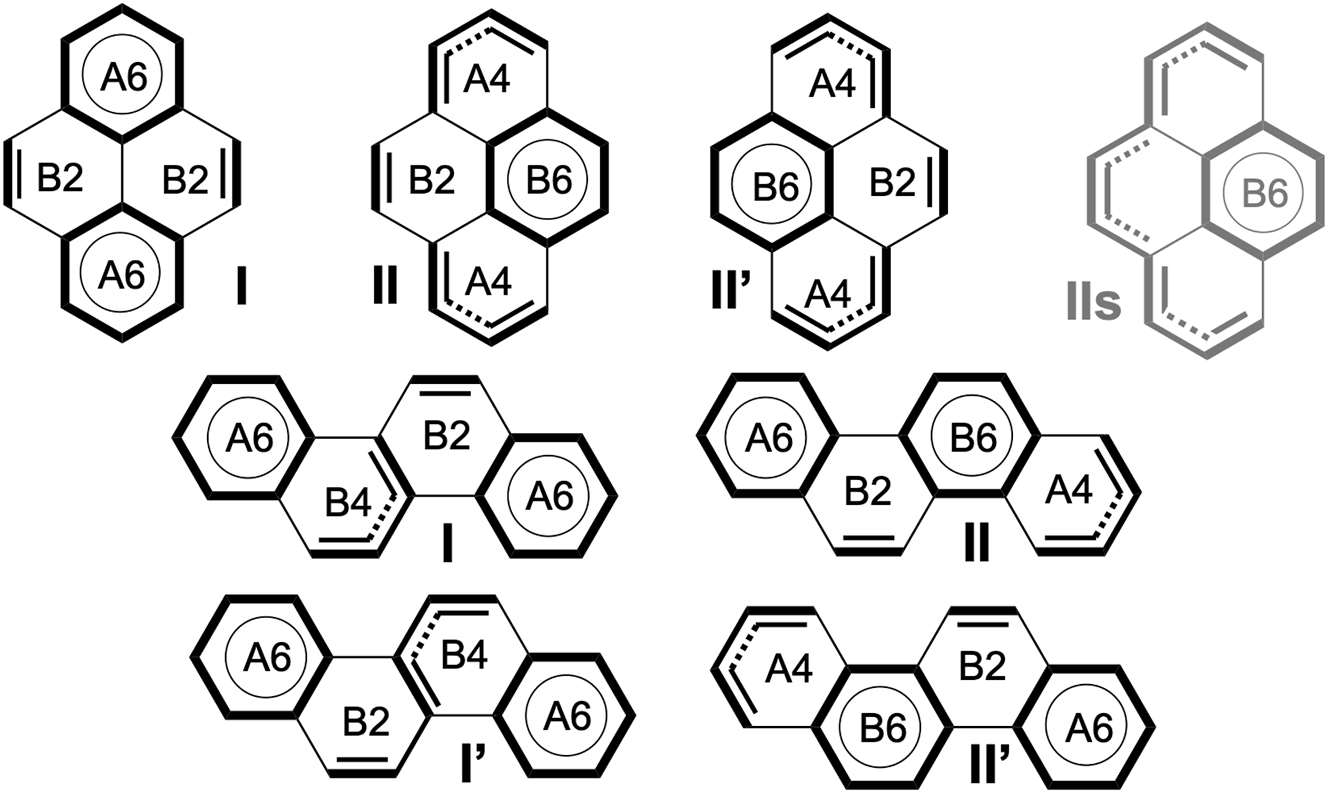

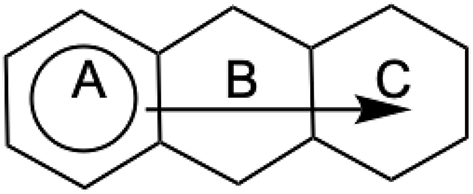

In this paper, we define Clar wavefunctions that adhere to Clar’s structural principles by explicitly localizing aromatic sextets, while assigning the remaining π electrons to short conjugated segments, preferably within the same ring. This electron partitioning is illustrated in Fig. 2, where bold bonds indicate localized units. Each cycle is annotated with the number of associated electrons, e.g., (A, B, C) → (A6, B2, C6). Conjugated fragments are in principle confined to their local atomic environments. In the anthracene example, the electrons of the B4 block are delocalized within ring B only, and are thus not conjugated with those of block C4.

Clar structures for 3 PAH. In the labels (e.g., A6), the letter indicates the ring, and the number indicates how many electrons are attributed to this ring. The coloured letters are the HuLiS logo.

All computations that rely on this Clar framework, have their orbitals optimized under localization constraints that reflect the targeted structures. A sextet is described by three bi-occupied orbitals restricted to the π system of six atoms. The same procedure applies to conjugated segments: for instance, two π orbitals optimized over four atoms describe a four-electron delocalized bond pattern, in the spirit of block-localized approaches. 47 Both ab-initio (VB-Clar) and empirical (HuLiS-Clar) calculations can be done. We obtain the weights of the structures and/or the energy associated to the resonance between structures. VB-Clar provides both indicators. Ultimately, these computations serve as valuable tools for exploring and giving meaning to the highly visual Clar description of PAHs.

Computational packages

HuLiS-Clar computations rely on the HLP algorithm described above. The java executable can be obtained freely from https://ctom-ism2.github.io/hulis/hulis_v3_4_0.jar. In order to compare the HuLiS-Clar description to ab initio computations, we used the XMVB program in its 3.2.1 version (released in 2023). 51 , 52 This gives us the freedom to follow the Clar localization in VB-Clar computations.

As suggested above, the VB-Clar computations simply follow the Clar sextext drawing, as we do with HuLiS-Clar. The only difference is that we have a geometry and a basis set. The geometry of each system was optimized at the B3LYP/6-311G(d) level with Gaussian 16. 53 , 54 Unless specified, the basis set for the VB-Clar computation is the 6-31G(d). 55

Results and discussion

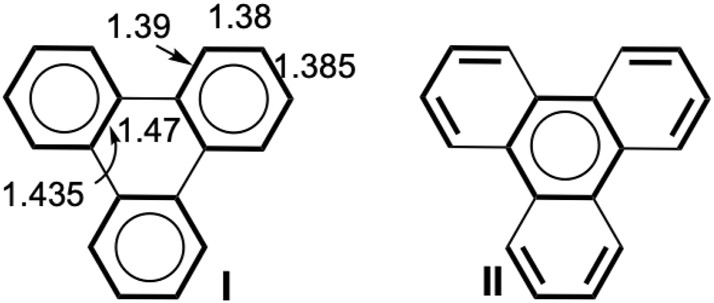

Clar’s rule: phenanthrene and triphenylene

As reminded above, the structure with a larger number of sextets is preferred. There are numerous examples in which the rule is validated when comparing local aromaticity indices such as structural (HOMA) or magnetic (NICS-like) to specific bond lengths and resonant schemes involving a few localized structures. 10 Phenanthrene (Fig. 1) is one of them, together with triphenylene. The X-ray parameters 56 of triphenylene are shown in Fig. 3, and they clearly indicate that structure I is more representative of the bond scheme than II, because the bonds of the inner ring are particularly elongated (1.47 and 1.435 Å), and are closer to single bonds than the other bonds at about 1.385 Å. We used the HuLiS-Clar computations to describe 5 exemplary PAH systems. The results are displayed in Table 1 together with our VB-Clar computations (for phenanthrene and triphenylene), and NICS and HOMA indicators from the litterature. 27 , 57

Triphenylene Clar structures and averaged bond lengths (Å) from X-ray diffraction. 56

HuLiS and VB-Clar results for the two structures calculations of phenanthrene and triphenylene, NICS(1) 27 and HOMA 57 values.

| HuLiS | VB | NICS(1) | HOMA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C i | w i (%) | C i | w i | A | B | A | B | ||

| Phenanthrene | I | 0.77 | 69 | 0.75 | 71 | −11.7 | −7.4 | 0.901 | 0.414 |

| II | 0.47 | 31 | 0.39 | 29 | |||||

| Triphenylene | I | 0.91 | 87 | 0.88 | 86 | −10.8 | −3.0 | 0.929 | 0.069 |

| II | 0.29 | 13 | 0.23 | 14 | |||||

| Pyrene | I | 0.60 | 50 | / | / | −14.5 | −5.6a | 0.952 | 0.475 |

| II II′ | 0.42 0.42 | 25 25 | / | / | |||||

| Chrysene | I I′ | 0.20 0.20 | 15 15 | / | / | −11.5 | −8.7a | 0.858 | 0.557 |

| II II′ | 0.49 0.49 | 35 35 | / | / | |||||

| Coronene | I I′ | 0.65 0.65 | 46 46 | / | / | −13.9 | −5.4b | 0.765 | 0.628 |

| II II′ | 0.16 0.16 | 4 4 | / | / | |||||

| Coronene super | I I′ | 0.46 0.46 | 23 23 | / | / | −13.9 | −5.4b | 0.765 | 0.628 |

| IIs | 0.71 | 54 | / | / | |||||

In the first two systems, we can compare HuLiS-Clar to the actual VB-Clar computations, and the agreement is particularly good. The weights for the structures I and II are similar, within 1 % (e.g., for phenathrene structure I is at 69 % with HuLiS-Clar and 71 % with VB-Clar (Table 1). Moreover, both localized computations have the largest weight on the structure that best fits with the NICS and HOMA indicators. In phenanthrene, for example, structure I is the main structure with aromatic sextets on the external rings (A and C, which are symmetric). The minor structure has the sextet on the inner ring. NICS(1) and HOMA indicators are larger for rings that are aromatic in the major structure, hence the agreement.

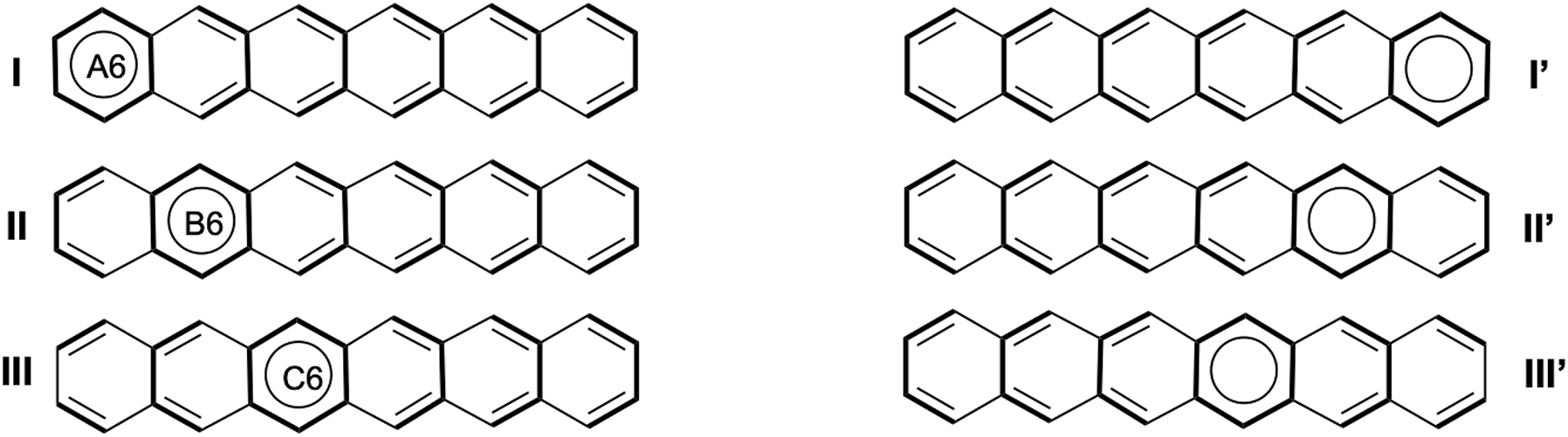

The next results concern pyrene with 3 resonance structures (Scheme 1). One structure has two sextets (I), and two structures with a single sextet (II and II′). The HuLiS-Clar computation favors significantly structure I with a weight 50 %, twice that of structure II or II′. However, it should be noted that in our definition of the structures II and II′, we restricted the conjugation of the non-aromatic electrons to their own cycle. As stated above, they are deconjugated. If II and II′ are replaced by IIs and its symmetric equivalent, we allow for a large delocalization of the non aromatic electrons, and the weights of those structures with a single sextet but a large delocalization increase to 35 % each while I’s weight is much reduced (30 %). The competition between conjugation and aromaticity is thus seen in this overlap-based method.

Clar structures for pyrene, and chrysene.

In chrysene, to avoid conjugation across the cycles, we duplicated structure I into I′, where the six non-aromatic electrons are delocalized as B4, B2 in I and B2, B4 in I′. In this case, all structures possess two sextets, making them equally probable according to Clar’s criterion. However, in the HuLiS-Clar computation, the weights are skewed in favor of structures II and II′. Although this result cannot be directly compared to NICS and HOMA indices for a strict validation of the HuLiS-Clar output, the values remain consistent: rings A and B are equally probable in structures II and II′, while structures I and I′ localize the sextets on the A rings. Even a small weight for I and I′, is consistent with the observation of stronger aromaticity indicators on A rings (NICS(1) = −11.5) compared to B rings (NICS(1) = −8.7).

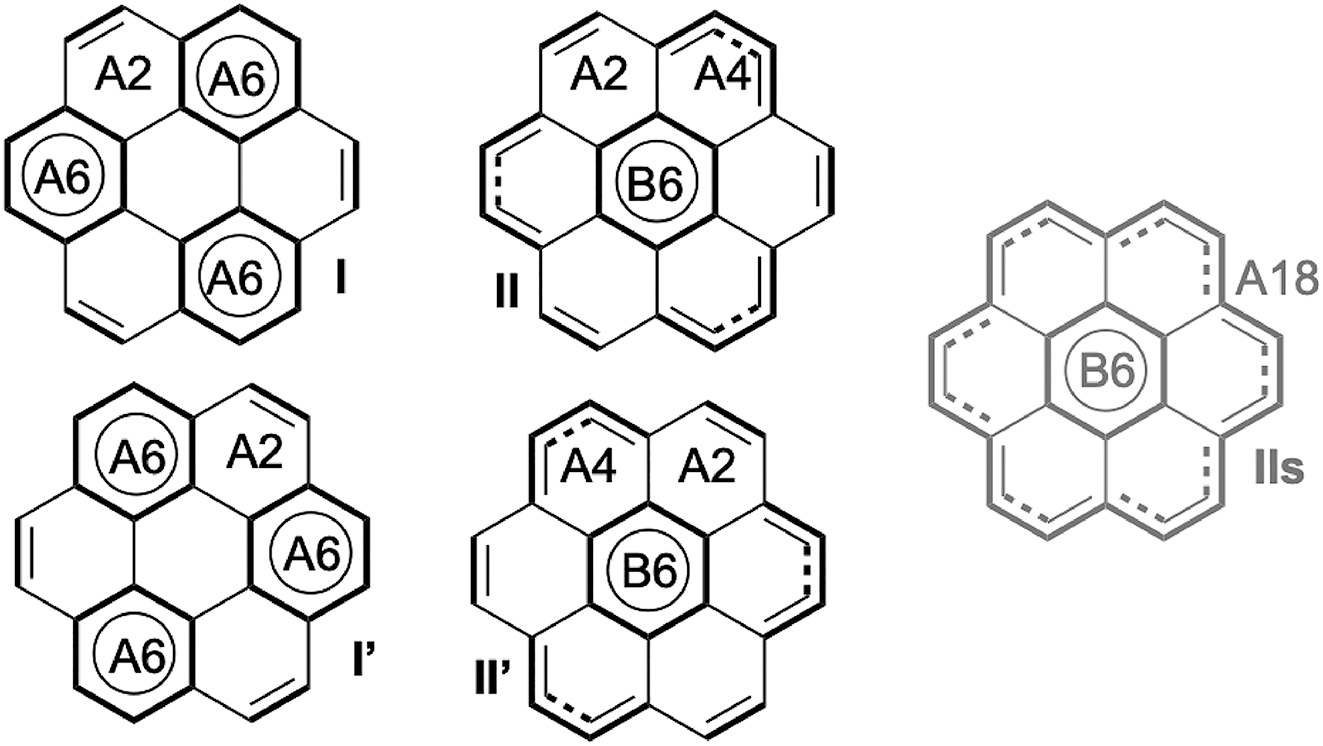

A similar result was obtained with the 4-structure calculation in coronene (Scheme 2). In this case, structures I and I′ contain three sextets, whereas II and II′ contain only one. Accordingly, HuLiS-Clar assigns a much larger weight (46 %) to I and I′ compared to II and II′ (4 %). The debate regarding the superaromaticity of coronene, initially proposed by Clar, is now settled: sextet aromaticity prevails over larger circuits whenever present. 9 , 59 Nevertheless, to test this in the HuLiS-Clar approach, II and II′ are replaced by a superaromatic structure IIs, in which the inner aromatic B ring is surrounded solely by the outer ring of edged bonds, involving 18 electrons (Scheme 2). Probably due to a large delocalization effect similar to what was observed in pyrene, HuLiS-Clar overestimates the weight of the superaromatic structure in this case, assigning it a value of 54 %, which is significantly higher than that of structures I and I′, both weighted at 23 %.

Clar structures for coronene. IIs represents a superaromatic structure, involving 18 electrons in the edge bonds.

This, along with the pyrene example, suggests that HuLiS-Clar should be applied to 6-membered ring cases only, and that inter-ring delocalization should be avoided.

Acenes: migrating sextet and biradical character

The Clar description in acenes makes use of migrating sextets as a way to represent delocalization (Scheme 3). In those systems the localized structures are in principle equiprobable, but the values of NICS(1) and HOMA show that the rings at the edge have a smaller aromaticity compared to the center. 60 NICS calculations have been deemed generally accurate in their analysis of aromaticity. However, some debates surged to propose new methods to explain the acenes properties. 61 , 62 We tested the HuLiS approach on long acenes to evaluate its behavior with respect to this trend. Moreover, long acenes are known to exhibit a biradical character, as evidenced notably by spin instabilities between RHF and UHF computations. 63 , 64 This aspect will also be addressed in the following, in the context of the HuLiS-Clar approach.

Anthracene’s migrating sextet. 60

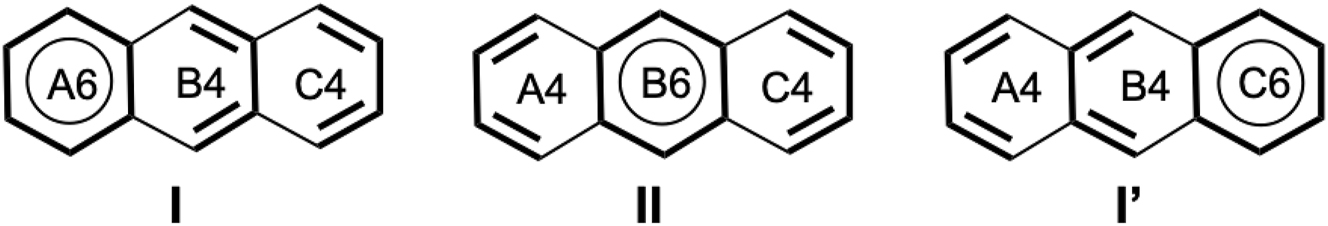

Variation of the weights along acenes

In the same spirit as what we have done in the previous paragraph, we define the three structures that describe the migrating sextet for anthracene, and submitted it to HuLiS-Clar. Scheme 4. Acenes formed of 4, 5, 6, and 7 cycles were also treated in the same way. For each acene, the structures can be grouped by symmetry; in anthracene, for instance, structures I and I′ are symmetrical and therefore have the same weight. In an n-acene composed of n hexagons, the Clar structures are labeled symmetrically: the first and last are denoted as I and I′, the second and second-to-last as II and II′, and so on (Scheme 5). The results are summarized in Table 2. It is shown that HuLiS systematically overestimates the weight of the structure with a sextet at the edge. Heptacene can be taken as an example: while the weights of structures II, III, and IV approximately follow the trends indicated by the indices of NICS(1) and HOMA, the weight of structure I and I′ is significantly overestimated: in heptacene w I = 18 and w IV = 13 while the NICS(1) on the first ring is almost twice smaller than that of the middle ring (−7.6 vs. −14.3). At the moment, we still do not fully understand why HuLiS-Clar systematically favors these edge structures.

Clar structures for anthracene.

Clar structures for hexacene.

HuLiS weights for the migrating sextet, with NICS(1) and HOMA values. 60

| HuLiS | NICS(1) | HOMA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracene | I I′ | 39 | −9.9 | 0.632 |

| II | 22 | −13.1 | 0.732 | |

| Tetracene | I I′ | 30 | −9.1 | 0.539 |

| II II′ | 20 | −13.1 | 0.632 | |

| Pentacene | I I′ | 24 | −8.5 | 0.453 |

| II II′ | 16 | −12.6 | 0.574 | |

| III | 19 | −13.9 | 0.608 | |

| Hexacene | I I′ | 20 | −7.9 | 0.460 |

| II II′ | 14 | −12.0 | 0.528 | |

| III III′ | 16 | −13.9 | 0.543 | |

| Heptacene | I I′ | 18 | −7.6 | 0.444 |

| II II′ | 12 | −11.5 | 0.505 | |

| III III′ | 14 | −13.6 | 0.517 | |

| IV | 13 | −14.3 | 0.513 | |

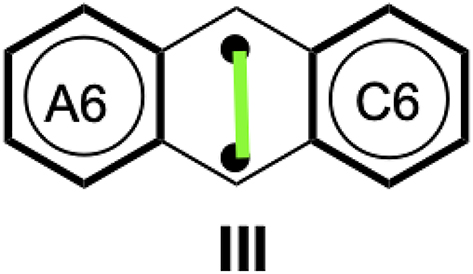

Biradical character

Additional questions arise even in these relatively simple acenes, where a degree of biradical character has been detected both experimentally and theoretically. 65 , 66 , 67 To address this degree of biradical character through local electronic structures, we added a structure to the calculation of the three-structure of anthracene, explicitly including a singlet coupling between two radicals (structure III in Scheme 6). This structure is important because for anthracene it is the only biradical that contains two sextets and, therefore, receives an a priori extra stabilization, despite a bond breaking. As a result, it should have the highest weight among the other biradical structures. In addition to the HuLiS-Clar calculations, we performed a VB-Clar calculation and projections following the HuLiS-Clar scheme, but using either a Hartree–Fock or a CAS(2,2) wavefunction. The results are presented in Table 3. For each approach, we provide a trust factor (except for VB-Clar, which is not a projected scheme), along with the coefficients and weights for each structures. The VB-Clar results will serve as our reference calculation. The coefficients and weights first show that this level is consistent with the NICS(1) evaluation of aromaticity: structures I and I′, which localize the aromatic sextet on the edge cycles, are less important than structure II. Second, even for such a small acene, the weight of the biradical structure is substantial (25 %).

Biradical structure of anthracene.

Weights of the Clar structures on the anthracene.

| HuLiS | VB | P-VB/HF | P-VB/CAS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C i | w i | C i | w i | C i | w i | C i | w i | |

| τ | 76 | / | 90 | 93 | ||||

| I I′ | 0.48 | 35 | 0.31 | 22 | 0.38 | 28 | 0.32 | 23 |

| II | 0.30 | 23 | 0.37 | 31 | 0.43 | 38 | 0.39 | 32 |

| III | −0.16 | 7 | −0.35 | 25 | −0.11 | 6 | −0.32 | 22 |

The HuLiS-Clar calculations suffer from the shortcomings already mentioned, with too large a weight for structures that localize the sextet on the edge cycles. The values differ slightly from those of Table 2 due to the inclusion of the biradical structure. As in the VB-Clar results, the coefficient of structure III is negative, which is qualitatively good but the values are significantly lower than in the reference VB-Clar results (7 % vs. 25 %).

To better understand the origin of the small importance of the biradical structure in HuLiS-Clar, we projected the components of the VB structures onto either the HF or the CAS(2,2) wavefunction. The corresponding columns in Table 3 show that the monodeterminantal HF wavefunction corresponds to a smaller weight for the biradical structure (6 %), while the multideterminantal CAS(2,2) wavefunction yields a weight approximately identical to that obtained from the calculation of VB-Clar (22 % vs. 25 %). The quality of the projection can be assessed from the trust factor, which is large in both cases (about 90 %), and slightly larger for the projection on CAS(2,2). These results indicate that, of the two major issues with the HuLiS-Clar approach, one (biradicals being underestimated) may be attributed to the monodeterminantal Hückel wavefunction, and the other seems inherent to the Hückel Hamiltonian (edge sextets are overestimated).

Conclusions

We have presented a local description of aromatic systems using the Clar formalism embedded in Valence Bond-like calculations. Our approach, implemented in the HuLiS program, considers blocks of electrons in addition to bonds and lone pairs/radical centers, providing a more nuanced understanding of aromaticity in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

The results demonstrate that the HuLiS-Clar method effectively reproduces Clar view of aromaticity, with the weights of localized structures in good agreement with ab initio computations. The method’s ability to handle aromatic sextets and delocalized electrons offers valuable insights into the electronic structure of PAHs.

However, the study also highlights some limitations, such as the overestimation of edge sextets in acenes and the underestimation of biradical character. These issues are attributed to the monodeterminantal nature of the Hückel wavefunction and the inherent limitations of the Hückel Hamiltonian. Future work could focus on refining the method to better account for these factors.

Overall, the HuLiS-Clar approach provides a powerful tool for exploring the aromaticity, bridging the gap between qualitative topological models and quantitative ab initio calculations.

Acknowledgments

Wei Wu is gratefully acknowledged for the XMVB programs. The authors acknowledge the French Research Ministry, Aix-Marseille Université (PhD grant for F.B.) for financial support.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: YC and NG made most of the implementation. FB made most of the calculations. DHR and SH built the project and wrote the paper.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: To improve language.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: French Research Ministry.

-

Data availability: Software availability: HuLiS is available on https://ctomism2.github.io/hulis/hulis_v3_4_0.jar.

Appendix I: Wavefunctions at the Hückel level

In the Hückel approach, the σ skelleton is disregarded, and we use the basis of the atomic p orbitals that make the π system (and π electrons, 1 per carbon atom for instance). Other atoms are of course available and the parameters are the usual Hückel parameters, 68 which can be modified in the interface. In the following, the p atomic orbitals are noted by their atom’s numbering {1, 2, 3}.

A specific localized structure |ψ

i

⟩ is represented as one (or two) Slater determinant(s) using π orbitals that are built on the relevant atoms. For a bond between atoms a and b, an orbital

Singlet coupled radicals are considered with two coupled determinants

Appendix II: Overlaps at the Hückel level

To show how the overlap between structures is computed in the Hückel framework, we take the example, of the two main resonant structures of the allyl cation,

This overlap should involve several permutations, but the result is obtained when the left-hand side determinant is considered as a spin-orbital product,

69

and the permutations that operate in the right-hand side determinant are restricted to those between electrons of the same spin. Each term is signed by

In our simple two-electron case with no pair of the same spin, there is no permutation and the expansion of the overlap is given by eq. 7. It is found that

For larger systems, for instance 4 electron systems, the permutations in the right-hand part writes as in eq. 8.

References

1. Merino, G.; Solà, M.; Fernández, I.; Foroutan-Nejad, C.; Lazzeretti, P.; Frenking, G.; Anderson, H. L.; Sundholm, D.; Cossío, F. P.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Wu, J.; Wu, J. I.; Restrepo, A. Aromaticity: Quo Vadis. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14 (21), 5569–5576. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2sc04998h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Baird, N. C. Quantum Organic Photochemistry. II. Resonance and Aromaticity in the Lowest 3ππ* State of Cyclic Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94 (14), 4941–4948. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00769a025.Search in Google Scholar

3. von Schleyer, P. R.; Jiao, H. What is Aromaticity? Pure Appl. Chem. 1996, 68 (2), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199668020209.Search in Google Scholar

4. Karadakov, P. B.; Al-Yassiri, M. A. H. Excited-State Aromaticity Reversals in Naphthalene and Anthracene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127 (14), 3148–3162. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.3c00485.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Rosenberg, M.; Dahlstrand, C.; Kilså, K.; Ottosson, H. Excited State Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity: Opportunities for Photophysical and Photochemical Rationalizations. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (10), 5379–5425. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300471v.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Artigas, A.; Hagebaum-Reignier, D.; Carissan, Y.; Coquerel, Y. Visualizing Electron Delocalization in Contorted Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12 (39), 13092–13100. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1sc03368a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. El Bakouri, O.; Szczepanik, D. W.; Jorner, K.; Ayub, R.; Bultinck, P.; Solà, M.; Ottosson, H. Three-Dimensional Fully π-Conjugated Macrocycles: When 3D-Aromatic and when 2D-Aromatic-in-3D? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144 (19), 8560–8575. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c13478.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Clar, E. Polycyclic Hydrocarbons; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1964.10.1007/978-3-662-01668-8Search in Google Scholar

9. Clar, E. The Aromatic Sextet. NATO ASI Series; Wiley: New York, 1972.Search in Google Scholar

10. Solà, M. Forty Years of Clar’s Aromatic π-Sextet Rule. Front. Chem. 2013, 1, 22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2013.00022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Kay, M. I.; Okaya, Y.; Cox, D. E. A Refinement of the Structure of the Room-Temperature Phase of Phenanthrene, C14H10, from X-ray and Neutron Diffraction Data. Acta Crystallogr. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 1971, 27 (1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1107/s0567740871001663.Search in Google Scholar

12. Pauling, L.; Sherman, J. The Nature of the Chemical Bond. VI. The Calculation from Thermochemical Data of the Energy of Resonance of Molecules Among Several Electronic Structures. J. Chem. Phys. 1933, 1 (8), 606–617. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1749335.Search in Google Scholar

13. Kistiakowsky, G. B.; Ruhoff, J. R.; Smith, H. A.; Vaughan, W. E. Heats of Organic Reactions. IV. Hydrogenation of Some Dienes and of Benzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1936, 58 (1), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01292a043.Search in Google Scholar

14. Ditchfield, R.; Hehre, W. J.; Pople, J. A.; Radom, L. Molecular Orbital Theory of Bond Separation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1970, 5 (1), 13–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(70)80116-6.Search in Google Scholar

15. Mo, Y.; Schleyer, P. V. An Energetic Measure of Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity Based on the Pauling-Wheland Resonance Energies. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12 (7), 2009–2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200500376.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Suresh, C. H.; Koga, N. An Isodesmic Reaction Based Approach to Aromaticity of a Large Spectrum of Molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 419 (4-6), 550–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2005.12.028.Search in Google Scholar

17. Cyrański, M. K. Energetic Aspects of Cyclic Pi-Electron Delocalization: Evaluation of the Methods of Estimating Aromatic Stabilization Energies. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105 (10), 3773–3811. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr0300845.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Norbeck, J. M.; Gallup, G. A. Valence-Bond Calculation of the Electronic Structure of Benzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96 (11), 3386–3393. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00818a008.Search in Google Scholar

19. Epiotis, N. D. Applications of Molecular Orbital-Valence Bond Theory in Chemistry. Pure Appl. Chem. 1983, 55 (2), 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac198855020229.Search in Google Scholar

20. Shaik, S.; Shurki, A.; Danovich, D.; Hiberty, P. C. A Different Story of Benzene. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 1997, 398-399, 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-1280(96)04934-2.Search in Google Scholar

21. Aihara, J. A New Definition of Dewar-Type Resonance Energies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98 (10), 2750–2758. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00426a013.Search in Google Scholar

22. Gutman, I.; Milun, M.; Trinajstic, N. Graph Theory and Molecular Orbitals. 19. Nonparametric Resonance Energies of Arbitrary Conjugated Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99 (6), 1692–1704. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00448a002.Search in Google Scholar

23. Randić, M. Aromaticity of Polycyclic Conjugated Hydrocarbons. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103 (9), 3449–3606. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9903656.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Chauvin, R.; Lepetit, C. The Fundamental Chemical Equation of Aromaticity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15 (11), 3855. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cp44075j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Randić, M. Benzenoid Rings Resonance Energies and Local Aromaticity of Benzenoid Hydrocarbons. J. Comput. Chem. 2019, 40 (5), 753–762. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.25760.Search in Google Scholar

26. Varet, A.; Prcovic, N.; Terrioux, C.; Hagebaum-Reignier, D.; Carissan, Y. BenzAI: A Program to Design Benzenoids with Defined Properties Using Constraint Programming. J. Chem. Inf. Mod. 2022, 62 (11), 2811–2820. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.2c00353.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Schleyer, P. V. R.; Maerker, C.; Dransfeld, A.; Jiao, H.; Van Eikema Hommes, N. J. R. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts: A Simple and Efficient Aromaticity Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118 (26), 6317–6318. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja960582d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Stanger, A. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts (NICS): Distance Dependence and Revised Criteria for Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71 (3), 883–893. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo051746o.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Geuenich, D.; Hess, K.; Köhler, F.; Herges, R. Anisotropy of the Induced Current Density (ACID), A General Method to Quantify and Visualize Electronic Delocalization. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105 (10), 3758–3772. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr0300901.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Fliegl, H.; Taubert, S.; Lehtonen, O.; Sundholm, D. The Gauge Including Magnetically Induced Current Method. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13 (46), 20500. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1cp21812c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Islas, R.; Heine, T.; Merino, G. The Induced Magnetic Field. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45 (2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar200117a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Krygowski, T. M. Crystallographic Studies of Inter- and Intramolecular Interactions Reflected in Aromatic Character of .pi.-Electron Systems. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1993, 33 (1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00011a011.Search in Google Scholar

33. Poater, J.; Fradera, X.; Duran, M.; Solà, M. The Delocalization Index as an Electronic Aromaticity Criterion: Application to a Series of Planar Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Chem. Eur. J. 2003, 9 (2), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200390041.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Portella, G.; Poater, J.; Solà, M. Assessment of Clar’s Aromatic π-Sextet Rule by Means of PDI, NICS and HOMA Indicators of Local Aromaticity. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18 (8), 785–791. https://doi.org/10.1002/poc.938.Search in Google Scholar

35. Karadakov, P. B.; Hearnshaw, P.; Horner, K. E. Magnetic Shielding, Aromaticity, Antiaromaticity, and Bonding in the Low-Lying Electronic States of Benzene and Cyclobutadiene. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81 (22), 11346–11352. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.6b02460.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Kleinpeter, E.; Koch, A. Identification and Quantification of Local Antiaromaticity in Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Based on the Magnetic Criterion. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22 (15), 3035–3044. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ob00114a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Lampkin, B. J.; Karadakov, P. B.; VanVeller, B. Detailed Visualization of Aromaticity Using Isotropic Magnetic Shielding. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (43), 19275–19281. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202008362.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Carissan, Y.; Hagebaum-Reignier, D.; Goudard, N.; Humbel, S. Hückel-Lewis Projection Method: A “Weights Watcher” for Mesomeric Structures. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112 (50), 13256–13262. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp803813e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Humbel, S. Getting the Weights of Lewis Structures Out of Hückel Theory: Hückel–Lewis Configuration Interaction (HL-CI). J. Chem. Educ. 2007, 84 (6), 1056. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed084p1056.Search in Google Scholar

40. Carissan, Y.; Hagebaum-Reignier, D.; Goudard, N.; Benzidi, H.; Humbel, S. Local Description with Lewis Structures at the Hückel Level. In Comprehensive Computational Chemistry; Yáñez, M.; Boyd, R. J., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2024, 1st ed.; pp. 605–616.10.1016/B978-0-12-821978-2.00036-2Search in Google Scholar

41. Carissan, Y.; Hagebaum-Reignier, D.; Goudard, N.; Humbel, S. Weight Watchers électronique : calculez votre poids de formes résonantes, ou les bienfaits du numérique, même approximatif. Act. Chim. 2016, 406, 36.Search in Google Scholar

42. Chirgwin, B. H.; Coulson, C. A. The Electronic Structure of Conjugated Systems. VI. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1950, 201 (1065), 196.10.1098/rspa.1950.0053Search in Google Scholar

43. Racine, J.; Hagebaum-Reignier, D.; Carissan, Y.; Humbel, S. Recasting Wave Functions into Valence Bond Structures: A Simple Projection Method to Describe Excited States. J. Comput. Chem. 2016, 37 (8), 771–779. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.24267.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Hiberty, P. C.; Leforestier, C. Expansion of Molecular Orbital Wave Functions into Valence Bond Wave Functions. A Simplified Procedure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100 (7), 2012–2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00475a007.Search in Google Scholar

45. Thorsteinsson, T.; Cooper, D. L.; Gerratt, J.; Karadakov, P. B.; Raimondi, M. Modern Valence Bond Representations of CASSCF Wavefunctions. Theor. Chim. Acta 1996, 93 (6), 343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002140050158.Search in Google Scholar

46. Hirao, K.; Nakano, H.; Nakayama, K.; Dupuis, M. A Complete Active Space Valence Bond (CASVB) Method. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105 (20), 9227–9239. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.472754.Search in Google Scholar

47. Mo, Y.; Song, L.; Lin, Y. Block-Localized Wavefunction (BLW) Method at the Density Functional Theory (DFT) Level. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111 (34), 8291–8301. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0724065.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Hiberty, P. C.; Humbel, S.; Byrman, C. P.; van Lenthe, J. H. Compact Valence Bond Functions with Breathing Orbitals: Application to the Bond Dissociation Energies of F2 and FH. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101 (7), 5969–5976. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.468459.Search in Google Scholar

49. Malrieu, J.-P.; Angeli, C.; Cimiraglia, R. On the Relative Merits of Non-Orthogonal and Orthogonal Valence Bond Methods Illustrated on the Hydrogen Molecule. J. Chem. Educ. 2008, 85 (1), 150. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed085p150.Search in Google Scholar

50. Da Silva, E. C.; Gerratt, J.; Cooper, D. L.; Raimondi, M. Study of the Electronic States of the Benzene Molecule Using Spin-Coupled Valence Bond Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101 (5), 3866–3887. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.467505.Search in Google Scholar

51. Song, L.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, W. XMVB: A Program for Ab Initio Nonorthogonal Valence Bond Computations. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26 (5), 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20187.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Chen, Z.; Ying, F.; Chen, X.; Song, J.; Su, P.; Song, L.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, W. XMVB 2.0: A New Version of Xiamen Valence Bond Program. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2015, 115 (11), 731–737. https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.24855.Search in Google Scholar

53. Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A. V.; Bloino, J.; Janesko, B. G.; Gomperts, R.; Mennucci, B.; Hratchian, H. P.; Ortiz, J. V.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Williams; Ding, F.; Lipparini, F.; Egidi, F.; Goings, J.; Peng, B.; Petrone, A.; Henderson, T.; Ranasinghe, D.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Gao, J.; Rega, N.; Zheng, G.; Liang, W.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Throssell, K.; MontgomeryJr.J. A.; Peralta, J. E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M. J.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E. N.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Keith, T. A.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A. P.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Adamo, C.; Cammi, R.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J. B.; Fox, D. J. Gaussian 16 Rev. A03, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

54. Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J. S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XX. A Basis Set for Correlated Wave Functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72 (1), 650–654. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.438955.Search in Google Scholar

55. Hehre, W. J.; Ditchfield, R.; Pople, J. A. Self – Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XII. Further Extensions of Gaussian – Type Basis Sets for Use in Molecular Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56 (5), 2257–2261. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1677527.Search in Google Scholar

56. Klug, A. The Crystal and Molecular Structure of Triphenylene, C18H12. Acta Crystallogr. 1950, 3 (3), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1107/s0365110x50000422.Search in Google Scholar

57. Howard, S.; Krygowski, T. Benzenoid Hydrocarbon Aromaticity in Terms of Charge Density Descriptors. Can. J. Chem. 1997, 75 (9), 1174–1181. https://doi.org/10.1139/v97-141.Search in Google Scholar

58. Ciesielski, A.; Cyrański, M. K.; Krygowski, T. M.; Fowler, P. W.; Lillington, M. Super-Delocalized Valence Isomer of Coronene. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71 (18), 6840–6845. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo060898w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Kumar, A.; Duran, M.; Solà, M. Is Coronene Better Described by Clar’s Aromatic π-Sextet Model or by the AdNDP Representation? J. Comput. Chem. 2017, 38 (18), 1606–1611. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.24801.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Schleyer, P. v. R.; Manoharan, M.; Jiao, H.; Stahl, F. The Acenes: Is There a Relationship Between Aromatic Stabilization and Reactivity? Org. Lett. 2001, 3 (23), 3643–3646. https://doi.org/10.1021/ol016553b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Fias, S.; Van Damme, S.; Bultinck, P. Multidimensionality of Delocalization Indices and Nucleus Independent Chemical Shifts in Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29 (3), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20794.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Leyva-Parra, L.; Pino-Rios, R.; Inostroza, D.; Solà, M.; Alonso, M.; Tiznado, W. Aromaticity and Magnetic Behavior in Benzenoids: Unraveling Ring Current Combinations. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30 (1), e202302415. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202302415.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Colvin, M. E.; Janssen, C. L.; Seidl, E. T.; Nielsen, I. M. B.; Melius, C. F. Energies, Resonance and UHF Instabilities in Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Linear Polyenes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 287 (5), 537–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2614(98)00228-0.Search in Google Scholar

64. Trinquier, G.; David, G.; Malrieu, J.-P. Qualitative Views on the Polyradical Character of Long Acenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122 (34), 6926–6933. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.8b03344.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

65. Andrzejak, M.; Petelenz, P. Vibronic Relaxation Energies of Acene-Related Molecules Upon Excitation or Ionization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20 (20), 14061–14071. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cp01562g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Szczepanik, D. W.; Solà, M.; Krygowski, T. M.; Szatylowicz, H.; Andrzejak, M.; Pawełek, B.; Dominikowska, J.; Kukułka, M.; Dyduch, K. Aromaticity of Acenes: The Model of Migrating π-Circuits. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20 (19), 13430–13436. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cp01108g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Portella, G.; Poater, J.; Bofill, J. M.; Alemany, P.; Solà, M. Local Aromaticity of [n]Acenes, [n]Phenacenes, and [n]Helicenes (n = 1−9). J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70 (7), 2509. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo0560254.Search in Google Scholar

68. Van-Catledge, F. A. A Pariser-Parr-Pople-Based Set of Hueckel Molecular Orbital Parameters. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45 (23), 4801–4802. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo01311a060.Search in Google Scholar

69. Shaik, S. S.; Hiberty, P. C. A Chemist’s Guide to Valence Bond Theory; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2007.10.1002/9780470192597Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2025-0495).

© 2025 IUPAC & De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Acid dissociation constants in selected dipolar non-hydrogen-bond-donor solvents (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Preface

- Introduction to the Special Issue of “The International Year of Quantum”

- Review Articles

- Quantum chemistry of molecules in solution. A brief historical perspective

- From Hückel to Clar: a block-localized description of aromatic systems

- Exploring potential energy surfaces

- Unlocking the chemistry facilitated by enzymes that process nucleic acids using quantum mechanical and combined quantum mechanics–molecular mechanics techniques

- Hypothetical heterocyclic carbenes

- Is relativistic quantum chemistry a good theory of everything?

- When theory came first: a review of theoretical chemical predictions ahead of experiments

- Research Articles

- Exploring reaction dynamics involving post-transition state bifurcations based on quantum mechanical ambimodal transition states

- Molecular aromaticity: a quantum phenomenon

- Using topology for understanding your computational results

- The role of ion-pair on the olefin polymerization reactivity of zirconium bis(phenoxy-imine) catalyst: quantum mechanical study and its beyond

- Theoretical insights on the structure and stability of the [C2, H3, P, O] isomeric family

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Acid dissociation constants in selected dipolar non-hydrogen-bond-donor solvents (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Preface

- Introduction to the Special Issue of “The International Year of Quantum”

- Review Articles

- Quantum chemistry of molecules in solution. A brief historical perspective

- From Hückel to Clar: a block-localized description of aromatic systems

- Exploring potential energy surfaces

- Unlocking the chemistry facilitated by enzymes that process nucleic acids using quantum mechanical and combined quantum mechanics–molecular mechanics techniques

- Hypothetical heterocyclic carbenes

- Is relativistic quantum chemistry a good theory of everything?

- When theory came first: a review of theoretical chemical predictions ahead of experiments

- Research Articles

- Exploring reaction dynamics involving post-transition state bifurcations based on quantum mechanical ambimodal transition states

- Molecular aromaticity: a quantum phenomenon

- Using topology for understanding your computational results

- The role of ion-pair on the olefin polymerization reactivity of zirconium bis(phenoxy-imine) catalyst: quantum mechanical study and its beyond

- Theoretical insights on the structure and stability of the [C2, H3, P, O] isomeric family