Abstract

The management of older patients with chronic primary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is still very challenging because of the fragility of older patients who frequently have severe comorbidities and/or disabilities. Corticosteroid-based first-line therapies fail in most of the cases and patients require a second-line treatment, choosing between rituximab, thrombopoietin-receptor agonists and splenectomy. The choice of the best treatment in elderly patients is a compromise between effectiveness and safety and laparoscopic splenectomy may be a good option with a complete remission rate of 67% at 60 months. But relapse and complication rates remain higher than in younger splenectomized ITP patients because elderly patients undergo splenectomy with unfavorable conditions (age >60 year-old, presence of comorbidities, or multiple previous treatments) which negatively influence the outcome, regardless the hematological response. For these reasons, a good management of concomitant diseases and the option to not use the splenectomy as the last possible treatment could improve the outcome of old splenectomized patients.

1 Introduction

Primary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an acquired hematologic disorder characterized by isolated peripheral thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100 x 109/L) in the absence of any other underlying disease [1-5]. Mostly, ITP is caused by the production of autoantibodies against platelet surface markers, leading to the increase of phagocytosis by the reticuloendothelial system, mainly present in the red pulp of the spleen [4,6]. The incidence of ITP is around 4 per 100,000 people per year [7] with a peak of 9 per 100,000 yearly in people over 60 years old. The yearly risk of fatal bleeding increases with age at a rate of 13% per annum for patients over 60 years old [3,7-8]. For these reasons, the correct diagnosis and the choice of the best treatment are important for a good management of these patients. Though the criteria are simple, the diagnosis of ITP is still very challenging, especially in older patients, because of the absence of specific recommendations and the priority to exclude other diseases which can mimic ITP in the elderly, such as myelodysplastic syndromes or drug-induced ITP (Table 1) [3].

| Platelet count < 100 × 109/L Presence of circulating antiplatelet antibodies Plasma TPO level normal or minimally elevated |

Bleeding symptoms:

|

Absence of:

|

Exclusion of underlying diseases:

|

Abbreviations. TPO: thrombopoietin; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; CMV: cytomegalovirus; VZV: varicella-zoster virus.

In absence of bleeding symptoms and a platelet count > 50 x 109/L, observation alone can be preferred, while a treatment is required when platelets are less than 30 x 109/L. ITP patients with platelet count from 30 to 50 x 109/L are considered for treatment in the following circumstances: 1) if older than 65 year-old, 2) in the presence of bleeding symptoms or history of bleeding, 3) presence of severe comorbidities such as hypertension which may cause intracranial hemorrhage, 4) poor health-related quality of life, 5) concomitant anticoagulation therapy with antiplatelet agents, or 6) if the patient requires a surgical procedure [1,3-5,7,9-12]. In all of these cases, a short-course of corticosteroids is recommended with a response rate of 70-80% [3-4,7]. The most used drug is prednisone at 1-2 mg/Kg/day for 4 weeks, but side effects such as gastritis, hyperglycemia, psychosis, hypertension and infections are commonly reported and underestimated [3-5,9,13-15]. To minimize the corticosteroid-related complications, dexamethasone at 40 mg/day for 4 days has been used with a response rate of 50% [3,5,16-17]. In cases of very low platelet count and severe bleeding, the administration of intravenous immunoglobulin can be added at lower doses (0.4 – 0.5 g/Kg for 4-5 days) with pre- and post-infusion hydration to reduce the risk of thrombosis, pulmonary edema and acute renal failure [3,12,18-22].

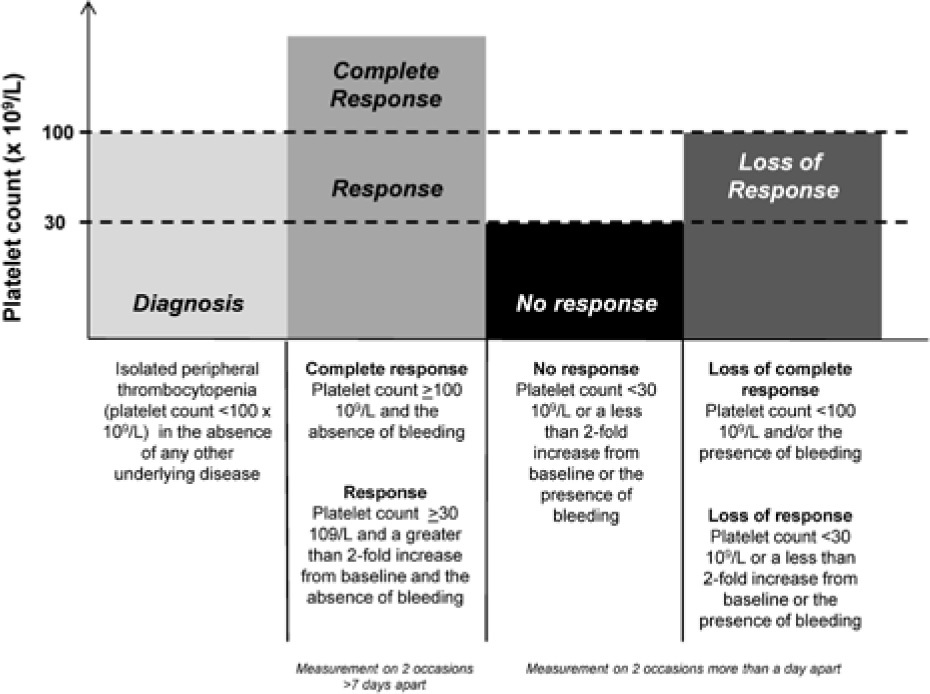

After treatment, patients could achieve a complete response (CR) or response (R), according to the criteria proposed by the International Working Group and the 2011 American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines, or they could experience no response (NR), or a loss of CR or R when corticosteroids are tapered or stopped (Figure 1) [5]. In these cases, a second-line therapy, such as splenectomy, rituximab and thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs), may be considered to maintain a safe level of platelet count and a low risk of bleeding [4-5,23-26]. Several studies have also shown the efficacy of danazol as a good alternative in older women with a response rate of 57-67% [3,27-28].

2011 ASH criteria for ITP treatment response.

In this review, we focused on the role of splenectomy as second-line therapy in ITP patients and, in particular, on the effectiveness of laparoscopic splenectomy in the management of chronic ITP in older subjects.

2 Literature analysis

2.1 Search strategy and inclusion and exclusion criteria

Relevant literature was searched in PubMed database, from 1946 to July 2016. The key words for searches were “Splenectomy” and “Primary immune thrombocytopenia”. Limiting factors were “elderly” or “adult”, and “English language”. Two investigators independently scanned, reviewed and chose from reference list all the potentially eligible abstracts and full text of articles for the review. Next, the eligible articles were reviewed independently for inclusion into the final analysis. Studies were included when they met the following criteria: (1) the date of publication was not earlier than 2000; (2) the article reported data collected since 1980.

From selected articles, data was collected into a standardized form for basic characteristics including publication year, source and time of cohort enrollment, study design, age, sex, number of enrolled patients divided by age and type of surgery, first-line therapies, time to splenectomy, platelet count before splenectomy, and vaccinations (Table 2 and 3). For the outcome the following parameters were considered: overall response rate (ORR, defined as CR+R) and relapse, the number of postoperative days, early and late complications, surgery-related mortality, red blood cell (RBC) transfusions and follow-up time.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

| Author and year | Study design | Multicenter (number of centers) | Source | Number of splenectomies (Male/Female) | Patient age (years, range) | Date of cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonzales-Porras J.R. et al., 2013 [30] | Retrospective | Yes (12) | Spain | 57 (27/30) | >65 | 1982 – 2011 |

| Park Y.H. et al., 2016 [29] | Retrospective | Yes (5) | Korea | 52 (11/41) | 66, 60-77 | 1998 – 2013 |

Preoperative characteristics

| Gonzales-Porras et al. | Park et al. | |

|---|---|---|

| Median time to splenectomy | 13 months (3-54.5) | 58 months (0-146) |

| Number of prior treatments | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-≥) |

| Operative technique | ||

| Open | 31 (54%) | 5 (9.6%) |

| Laparoscopy | 26 (46%) | 47 (90.4%) |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 43 (16-82) | 60 (2-347) |

| Vaccinations | ||

| Pneumococcus | 52 (91%) | 46 (88.5%) |

| Platelet transfusion | n.r. | 9.5 |

2.2 Statistical Analysis

All data was collected from a computerized database and chart review and was analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 6.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

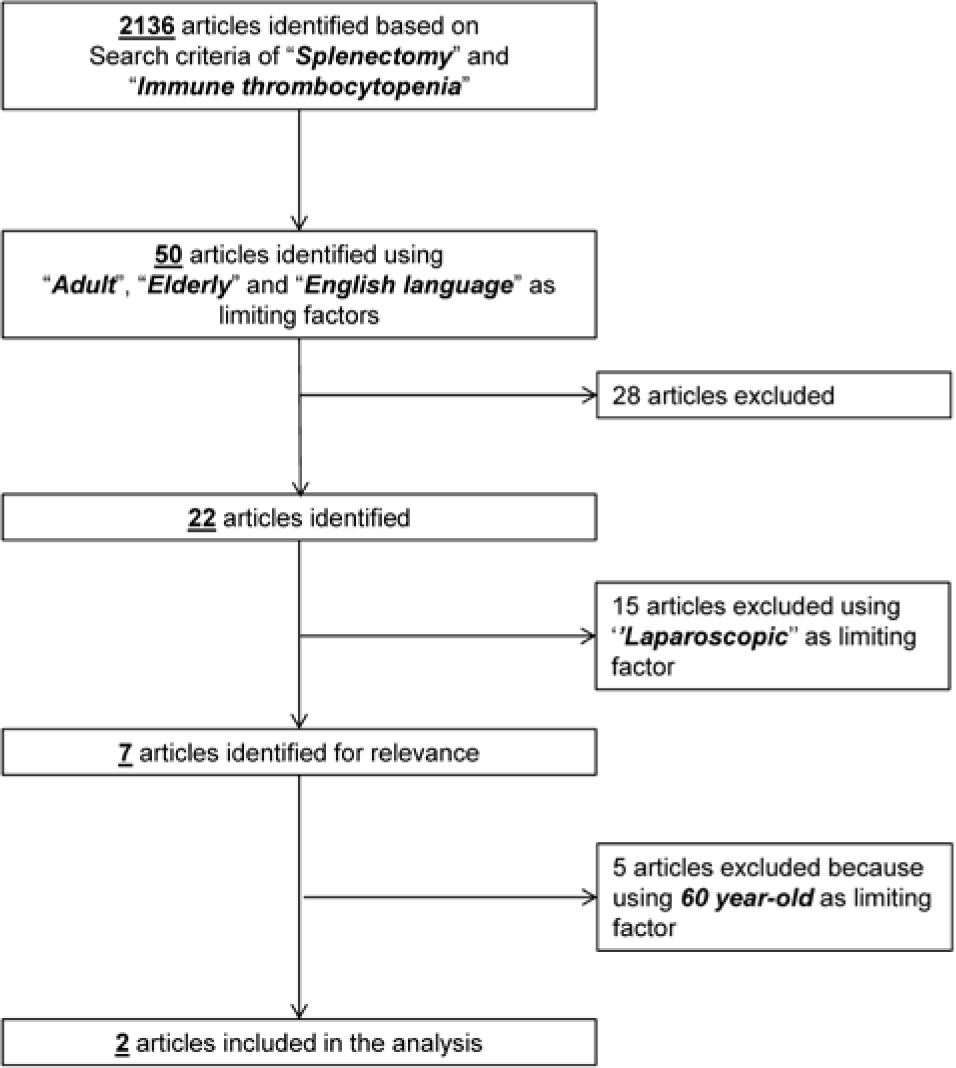

A total of 2136 articles were screened and 50 of these were identified as eligible for review. We excluded 28 articles because they did not meet the selection criteria. Of the remaining 22 articles, 7 were chosen for relevance and for the use of “Laparoscopic” as limiting factor. Five articles were excluded because the median age of the cohort was less than 60 year-old or the results were not divided according to the age. Figure 2 shows the flow diagram for the selection process. A total of 2 articles were finally included in the analysis [29-30].

Flow diagram of search strategy

3.2 Pre-operative characteristics

From 1982 to 2013, a total of 109 splenectomies in older ITP patients (male/female, 38/71; age > 60 year-old) were described in selected retrospective studies (Table 2), performed with open technique in 33% of cases (n=36) and laparoscopic procedure in 67% of subjects (n=73) (Table 3). The comorbidities were described differently in each study: as median Charlson index of 4.1 as in Gonzales-Porras et al. or as 84.6% of patients with underlying diseases (mostly cardiovascular diseases or diabetes) as in Park et al. Patients underwent splenectomy after a median time from diagnosis of 35.5 months (varying from 0 to 146 months) and a median number of prior treatments of 2 (range, 1 to more than 3). Pneumococcal vaccination was performed in 89.9% of patients (n=98) at least two weeks before surgery. The median preoperative platelet count was 51.5 x 109/L (range, 2 – 347 x109/L).

3.3 Surgical procedure

Laparoscopic splenectomy could be performed using a lateral or anterior approach, preferred for very large spleens. The operation starts with safe laparoscopic abdominal access using open or closed technique with a Verres needle (contraindicated in patients with massive splenomegaly and severe thrombocytopenia). Once the peritoneal cavity is accessed, 4-5 trocars are positioned: the first (5 or 12 mm port) in the midclavicular line at 2-6 cm below the costal margin; the second medial trocar in the midline subxiphoid region in the left subcostal position; the third in the anterior axillary line in the left subcostal region; the fourth laterally off the tip of the 11th rib. The port with the best angle for hilar ligation could be used as a 12 mm port for the endoscopic stapler and for the extraction of the spleen. Preliminary to the procedure, accessory spleens have to be looked for in the hilum, omentum, mesocolon or mesentery. Dissection starts from the inferior pole of the spleen with the section of the splenocolic, splenorenal and gastrosplenic ligaments. After this, the splenic hilum is accessible and the splenic artery can be controlled, proximal to the splenic hilum (1-2 cm), along the superior border of the pancreas; otherwise the splenophrenic ligament can be divided superiorly. Then the hilum is carefully dissected from the tail of pancreas and splenopancreatic ligament. Now, the splenic vasculature can be ligated and divided and the spleen can be grasped from the splenocolic ligament left on the inferior border and flipped with the hilum facing up. The spleen is ready to be placed in a retrievable sac and morcellated, unless the spleen must be removed intact for pathologic analysis. During the morcellation phase, it is important to not break the bag and spill the splenic tissue into the peritoneal cavity. When the morcellation cannot be performed, the spleen could be removed through a Pfannenstiel suprapubic access. After removal, hemostasis must be evaluated; suction drains are placed, the abdomen is reinsufflated and the skin incisions are closed [31-38].

3.4 Outcome and complication rate

Splenectomized patients experienced a median postoperative stay of 8 days (range, 4–52 days). The median follow-up was 60 months (range, 0–146 months). Using the 2011 ASH criteria for ITP treatment response, 73 patients (67%) achieved a complete response (CR) after splenectomy and 14 subjects (13%) a response (R), for an overall response rate (ORR) of 80%. Nineteen percent of patients (n=21) did not respond to treatment, and 39% (n=43) relapsed after surgery (Table 4).

Response after splenectomy

| Gonzales-Porras et al. | Park et al. | |

|---|---|---|

| Postoperative days | 8 (6-14) | 9.5 (4-52) |

| CR (%) | 41 (71.9) | 32 (61.5) |

| R (%) | 4 (7) | 10 (19.2) |

| ORR (%) | 45 (78.9) | 42 (80.7) |

| NR (%) | 12 (7.5) | 9 (17.3) |

| Relapse (%) | 24 (42.9) | 19 (45.2) |

| Follow-up (months) | 62 (27-113) | 58 (0-146) |

| PFS (months) | >42 | 3 |

Abbreviations. CR: complete response; R: response; ORR: overall response rate; NR: no response; PFS: progression-free survival.

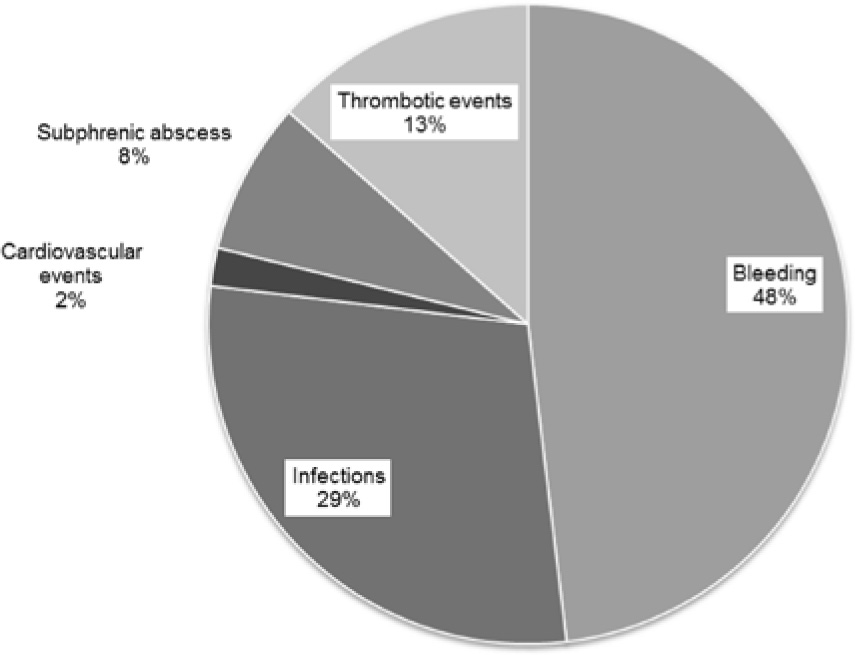

Operative mortality was assessed at 2% (n=2), but one death was related to an intracranial hemorrhage 5 days post-splenectomy. The complication rate was 48% (n=52) and early or late bleeding was the most frequent complication (48% of all postoperative events, n=25). Other frequent complications were infections (29%, n=15), late thrombotic events (13%, n=7), and subphrenic abscess (8%, n=4). Cardiovascular events were reported at very low frequency (2%, n=1 as paroxysmal atrial fibrillation).

Red blood cell transfusions were performed in a median of 16 splenectomized patients (0-16) (Table 5 and Figure 3).

Complication rate in elderly splenectomized ITP patients.

Postoperative complications

| Gonzales-Porras et al. | Park et al. | |

|---|---|---|

| Any complications | 31 | 21 |

| Bleeding | 16 | 9 |

| Infections | 11 | 4 |

| Cardiovascular events | 0 | 1 |

| Subphrenic abscess | 3 | 1 |

| Thrombotic events | 1 | 6 |

| RBC transfusion | 16 | 0 (0-10) |

| Operative mortality | 1 | 1 |

Abbreviations. RBC: red blood cells.

4 Discussion

Diagnosis and management of ITP are still very challenging in older patients because of the lack of guidelines [3,39-41]. Treatment is required for patients older than 65 years with a platelet count less than 50 x 109/L, and/ or when bleeding symptoms, severe comorbidities, severe disabilities or anticoagulation therapy are reported [3]. First-line therapies include short-course corticosteroids with or without low-dose intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg), but are not effective for a sustained response, since most patients relapse after tapering off or stopping therapy [4-5,23-26,39-41]. For this reason, adult, especially elderly, ITP patients develop chronic ITP with a very-high yearly risk of fatal bleeding [3,7-8]. International guidelines equally suggest the use of splenectomy, rituximab and TPO-RAs as second-line therapy, with the option to switch from one to another in case the previous treatment should fail [4-5,23-26,39-45].

Given the increasingly frequent use of less invasive techniques, such as the fine-needle aspiration biopsy, splenectomy is less and less used in malignant hematological disorders for diagnostic purposes [46-51], but is still used for palliation or to facilitate drug therapy [43-45]. Conversely, splenectomy so far is a key treatment option in hematological benign disorders such as ITP, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, hereditary spherocytosis and some types of hemoglobinopathies and thalassemia [45]. Among the benign hematological disorders, one of the most frequent indications for splenectomy is definitely ITP [42,45]. In children, the 2011 ASH guidelines recommend delaying splenectomy until the chronic phase (>12 months), unless severe disease is unresponsive to other treatments or causes a poor quality of life [4,5]. Together with the higher postoperative complication rate and mortality of major surgery in adults due to comorbidities, splenectomy is usually the third choice in elderly patients and is delayed for longer than the recommended 12 months (median, 35.5 months), as we highlighted in the two selected studies [29,30].

Several reviews reported a complete remission rate (CRr) after splenectomy of 66% at 28 months (range, 1 – 153 months) in children and adults, or of 64% at 7.25 years (range, 5 – 12.75 years) only in adults, or of 72% at 5 years only in patients who received laparoscopic splenectomy. Two limitations of this data set are the definition of “adult” which contains a wide range of patients up to 18 years old and the combination of data from children and adults [42]. The two studies included in our series focused on small cohorts of patients older than 60 years but CRr and ORR were similar to the general splenectomized population (67% at 60 months and 80% vs 88% of all splenectomies, respectively). Gonzales-Porras et al. and Park et al. described a relapse rate in elderly patients of 39%, 2.5-fold higher than the general splenectomized population (15%; range, 0 – 51%) [29,30]. Therefore, these findings suggest that splenectomies in elderly patients could not be used a “definitive” treatment as it is in younger patients [42]. On the other hand, the authors suggested that the higher relapse rate is negatively influenced by the older age (>65 year-old) and lack of response to prior treatments [29,30]. Indeed, several studies showed that an age of < 50 years old and the response to previous therapies are favorable predictive factors for hematological remission after splenectomy [6,42]. Gonzales-Porras et al. confirmed these reports because the highest relapse rate was found in older patients who received several treatments before splenectomy. The 30-day mortality in laparoscopic and open splenectomy was assessed at 0.2% and 1% respectively in the general ITP population, similar to the rate observed in our series of older patients (1%), and is not related to the type of surgery [42].

Due to their comorbidities, mostly diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, older patients more frequently experience postoperative complications, which may negatively affect the outcome regardless of the underlying disease [3,52-54]. The complication rate in all splenectomies was assessed at 9.6% for laparoscopy and 12.9% for laparotomy, 10- and 4-fold lower respectively than the reported older cohorts [42]. Early and late bleedings are the most frequent complications in younger, adult and older patients, and the risk was not related to the use of anti-aggregation agents [3,42]. Interestingly, in older ITP patients, the infection rate was 13.8%, higher than the 3-10% of all splenectomies, even if 89.9% of patients received at least pneumococcal immunization prior to surgery [3,55]. These findings support the hypothesis that splenectomy deregulates the immune system which becomes less efficient at removing encapsulated bacteria or other pathogenic particles in peripheral blood, increasing the frequency of recurrent bacterial and viral infections and the risk of overwhelming sepsis [54]. This susceptibility may be highlighted in elderly patients because of their comorbidities and older age, explaining the higher infection rate reported in this population after splenectomy. Thromboembolic events represent the most frequent late complications: up to 70% of splenectomized patients experienced a portal vein thrombosis of unknown clinical significance, because in most cases therapy was not necessary [2,56]. Major events were documented in 10% of all cases, as well as in elderly cases (6%) [42].

As favorable predictive factors for response to splenectomy, several studies suggest the use of preoperative platelet count, though Gonzales-Porras et al. did not report a significant correlation between higher preoperative platelet count and complete remission after splenectomy [6,29-30]; instead a higher postoperative platelet count may better predict the hematological response after surgery [29].

5 Conclusion

The management of older patients with chronic ITP is still challenging because of the presence of severe comorbidities and/or disabilities that influence the choice of the best treatment, which becomes a compromise between effectiveness and safety. As second-line therapy, laparoscopic or open splenectomy could be chosen as “curative” strategy in younger patients and women who contemplate pregnancy with higher complete response rates and low complication frequencies. Older patients undergoing splenectomy already have unfavorable conditions (age >60 year-old, presence of comorbidities, or multiple previous treatments) which negatively influence the outcome, increasing the relapse and complication rates. For these reasons, a good management of concomitant diseases and the option not to use splenectomy as the last possible chance could improve the outcome of older splenectomized patients who, nevertheless, show a response rate similar to general ITP population after surgery. However, these results require further validation in prospective or randomized larger studies.

Conflict of interest statement: Authors state no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

[1] Rodeghiero F., Stasi R., Gernsheimer T., Michel M., Provan D., Arnold D.M., et al., Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group, Blood., 2009, 113, 2386-239310.1182/blood-2008-07-162503Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Ghanima W., Godeau B., Cines D.B., Bussel J.B., How I treat immune thrombocytopenia: the choice between splenectomy or a medical therapy as a second-line treatment, Blood., 2012, 120, 960-96910.1182/blood-2011-12-309153Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Mahévas M., Michel M., Godeau B., How we manage immune thrombocytopenia in the elderly, Br J Haematol., 2016, 173, 844-85610.1111/bjh.14067Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Neunert C.E., Current management of immune thrombocytopenia, Hematology Am Soc of Hematol Educ Program., 2013, 276-28210.1182/asheducation-2013.1.276Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Neunert C., Lim W., Crowther M., Cohen A., Solberg L., Crowther M.A., The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia, Blood., 2011, 117, 4190-4207.10.1182/blood-2010-08-302984Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Duperier T., Brody F., Felsher J., Walsh R.M., Rosen M., Ponsky J., Predictive factors for successful laparoscopic splenectomy in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura, Arch Surg., 2004, 139, 61-6610.1001/archsurg.139.1.61Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Provan D., Stasi R., Newland A.C., Blanchette V.S., Bolton-Maggs P., Bussel J.B., et al., International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia, Blood., 2010, 115, 168-18610.1182/blood-2009-06-225565Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Moulis G., Palmaro A., Montastruc J.L., Godeau B., Lapeyre-Mestre M., Sailler L., Epidemiology of incident immune thrombocytopenia: a nationwide population-based study in France, Blood., 2014, 124: 3308-331510.1182/blood-2014-05-578336Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Cortelazzo S., Finazzi G., Buelli M., Molteni A., Viero P., Barbui T., High risk of severe bleeding in aged patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, Blood., 1991, 77, 31-3310.1182/blood.V77.1.31.31Search in Google Scholar

[10] Portielje J.E., Westendorp R.G., Kluin-Nelemans H.C., Brand A., Morbidity and mortality in adults with idiopathic thrombocy-topenic purpura, Blood., 2001, 97, 2549-255410.1182/blood.V97.9.2549Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bourgeois E., Caulier M.T., Delarozee C., Brouillard M, Bauters F., Fenaux P., Long-term follow-up of chronic autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura refractory to splenectomy: a prospective analysis, Br J Haematol., 2003, 120, 1079-108810.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04211.xSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Michel M., Rauzy O.B., Thoraval F.R., Languille L., Khellaf M., Bierling P., et al., Characteristics and outcome of immune thrombocytopenia in elderly: results from a single center case-controlled study, Am J Hematol., 2011, 86, 980-98410.1002/ajh.22170Search in Google Scholar

[13] Gentile M., Zirlik K., Ciolli S., Mauro F.R., Di Renzo N., Mastrullo L., et al., Combination of bendamustine and rituximab as front-line therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: multicenter, retrospective clinical practice experience with 279 cases outside of controlled clinical trials, Eur J Cancer., 2016, 60, 154-16510.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.069Search in Google Scholar

[14] Daou S., Federici L., Zimmer J., Maloisel F., Serraj K., Andrès E., Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in elderly patients: a study of 47 cases from a single reference center, Eur J Intern Med., 2008, 19, 447-45110.1016/j.ejim.2007.07.006Search in Google Scholar

[15] Tamez-Pérez H.E., Quintánilla-Flores D.L., Rodríguez-Gutierrez R., González-González J.G., Tamez-Peña A.L., Steroid hyperglycemia: Prevalence, early detection and therapeutic recommendations: A narrative review, World J Diabetes., 2015, 6, 1073-108110.4239/wjd.v6.i8.1073Search in Google Scholar

[16] Cheng Y., Wong R.S., Soo Y.O., Chui C.H., Lau F.Y., Chan N.P., et al., Initial treatment of immune thrombocytopenic purpura with high-dose dexamethasone, N Engl J Med., 2003, 349, 831-83610.1056/NEJMoa030254Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mazzucconi M.G., Fazi P., Bernasconi S., De Rossi G., Leone G., Gugliotta L., et al., Therapy with high-dose dexamethasone (HD-DXM) in previously untreated patients affected by idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a GIMEMA experience, Blood., 2007, 109, 1401-140710.1182/blood-2005-12-015222Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ahsan N., Intravenous immunoglobulin induced-nephropathy: a complication of IVIG therapy, J Nephrol., 1998, 11, 157-161Search in Google Scholar

[19] Carbone J., Adverse reactions and pathogen safety of intravenous immunoglobulin, Curr Drug Saf., 2007, 2, 9-1810.2174/157488607779315480Search in Google Scholar

[20] Khellaf M., Michel M., Schaeffer A., Bierling P., Godeau B., Assessment of a therapeutic strategy for adults with severe autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura based on a bleeding score rather than platelet count, Haematologica., 2005, 90, 829-832Search in Google Scholar

[21] Godeau B., Chevret S., Varet B., Lefrère F., Zini J.M., Bassompierre F., et al., Intravenous immunoglobulin or high-dose methylprednisolone, with or without oral prednisone, for adults with untreated severe autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura: a randomised, multicentre trial, Lancet., 2002, 359, 23-2910.1016/S0140-6736(02)07275-6Search in Google Scholar

[22] Fiorelli A., Petrillo M., Vicidomini G., Di Crescenzo V.G., Frongillo E., De Felice A., et al., Quantitative assessment of emphysematous parenchyma using multidetector-row computed tomography in patients scheduled for endobronchial treatment with one-way valves, Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg., 2014, 19, 246-25510.1093/icvts/ivu107Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Mahevas M., Gerfaud-Valentin M., Moulis G., Terriou L., Audia S., Guenin S., et al., A Multicenter, Case-Control Study Evaluating the Characteristics and Outcome of ITP Patients Refractory to, Rituximab, Splenectomy and Both TPO Receptor Agonists, Blood., 2015, 12610.1182/blood.V126.23.3460.3460Search in Google Scholar

[24] Khellaf M., Michel M., Quittet P., Viallard J.F., Alexis M., Roudot-Thoraval F., et al., Romiplostim safety and efficacy for immune thrombocytopenia in clinical practice: 2-year results of 72 adults in a romiplostim compassionate-use program, Blood., 2011, 118, 4338-434510.1182/blood-2011-03-340166Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Godeau B., Porcher R., Fain O., Lefrère F., Fenaux P., Cheze S., et al., Rituximab efficacy and safety in adult splenectomy candidates with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura: results of a prospective multicenter phase 2 study, Blood., 2008, 112, 999-100410.1182/blood-2008-01-131029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Ghanima W., Bussel J.B., Thrombopoietic agents in immune thrombocytopenia, Semin Hematol., 2010, 47, 258-26510.1053/j.seminhematol.2010.03.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Ahn Y.S., Efficacy of danazol in hematologic disorders, Acta Haematol., 1990, 84, 122-12910.1159/000205048Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Maloisel F., Andrès E., Zimmer J., Noel E., Zamfir A., Koumarianou A., et al., Danazol therapy in patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: long-term results, Am J Med., 2004, 116, 590-59410.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Park Y.H., Yi H.G., Kim C.S., Hong J., Park J., Lee J.H., et al., Clinical Outcome and Predictive Factors in the Response to Splenectomy in Elderly Patients with Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia: A Multicenter Retrospective Study, Acta Haematol., 2016, 135, 162-17110.1159/000442703Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Gonzalez-Porras J.R., Escalante F., Pardal E., Sierra M., Garcia-Frade L.J., Redondo S., et al., Safety and efficacy of splenectomy in over 65-yrs-old patients with immune thrombocytopenia, Eur J Haematol., 2013, 91, 236-24110.1111/ejh.12146Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Habermalz B., Sauerland S., Decker G., Delaitre B., Gigot J.F., Leandros E., et al., Laparoscopic splenectomy: the clinical practice guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES), Surg Endosc., 2008, 22, 821-84810.1007/s00464-007-9735-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Somasundaram S.K., Massey L., Gooch D., Reed J., Menzies D., Laparoscopic splenectomy is emerging ‘gold standard’ treatment even for massive spleens, Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl., 2015, 1-410.1308/003588414X14055925TestSearch in Google Scholar

[33] Uranues S., Alimoglu O., Laparoscopic surgery of the spleen, Surg Clin North Am., 2005, 85, 75-9010.1016/j.suc.2004.09.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Park A.E., Birgisson G., Mastrangelo M.J., Marcaccio M.J., Witzke D.B., Laparoscopic splenectomy: outcomes and lessons learned from over 200 cases, Surgery., 2000, 128, 660-66710.1067/msy.2000.109065Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Pace D.E., Chiasson P.M., Schlachta C.M., Mamazza J., Poulin E. C., Laparoscopic splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), Surg Endosc., 2003, 17, 95-9810.1007/s00464-002-8805-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Wang K.X., Hu S.Y., Zhang G.Y., Chen B., Zhang H.F., Hand-assisted laparoscopic splenectomy for splenomegaly: a comparative study with conventional laparoscopic splenectomy, Chin Med J. (Engl), 2007, 120, 41-4510.1097/00029330-200701010-00008Search in Google Scholar

[37] Barbaros U., Aksakal N., Tukenmez M., Agcaoglu O., Bostan M.S., Kilic B., et al., Comparison of single port and three port laparoscopic splenectomy in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura: Clinical comparative study, J Minim Access Surg., 2015, 11, 172-17610.4103/0972-9941.159853Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Santini M., Fiorelli A., Messina G., Laperuta P., Mazzella A., Accardo M., Use of the LigaSure device and the Stapler for closure of the small bowel: a comparative ex vivo study, Surg Today., 2013, 43, 787-79310.1007/s00595-012-0336-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Mahèvas M., Gerfaud-Valentin M., Moulis G., Terriou L., Audia S., Guenin S., et al., Characteristics, outcome and response to therapy of multirefractory chronic immune thrombocytopenia, Blood., 201610.1182/blood-2016-03-704734Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Michel M., Suzan F., Adoue D., Bordessoule D., Marolleau J.P., Viallard J.F., et al., Management of immune thrombocytopenia in adults: a population-based analysis of the French hospital discharge database from 2009 to 2012, Br J Haematol., 2015, 170, 218-22210.1111/bjh.13415Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Kojouri K., George J.N., Recent advances in the treatment of chronic refractory immune thrombocytopenic purpura, Int J Hematol., 2005, 81, 119-12510.1532/IJH97.04173Search in Google Scholar

[42] Kojouri K., Vesely S.K., Terrell D.R., George J.N., Splenectomy for adult patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review to assess long-term platelet count responses, prediction of response, and surgical complications, Blood., 2004, 104, 2623-263410.1182/blood-2004-03-1168Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Heniford B.T., Matthews B.D., Answini G.A., Walsh R.M., Laparoscopic splenectomy for malignant diseases, Semin Laparosc Surg., 2000, 7, 93-10010.1007/978-1-4757-3444-7_12Search in Google Scholar

[44] Walsh R.M., Brody F., Brown N., Laparoscopic splenectomy for lymphoproliferative disease, Surg Endosc., 2004, 18, 272-27510.1007/s00464-003-8916-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Silecchia G., Boru C.E., Fantini A., Raparelli L., Greco F., Rizzello M., et al., Laparoscopic splenectomy in the management of benign and malignant hematologic diseases, JSLS. 2006, 10, 199-205Search in Google Scholar

[46] Cozzolino I., Varone V., Picardi M., Baldi C., Memoli D., Ciancia G., et al., CD10, BCL6, and MUM1 expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma on FNA samples, Cancer Cytopathol., 2016, 124, 135-14310.1002/cncy.21626Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Cozzolino I., Vigliar E., Todaro P., Peluso A.L., Picardi M., Sosa Fernandez L.V., et al., Fine needle aspiration cytology of lymphoproliferative lesions of the oral cavity, Cytopathology., 2014, 25, 241-24910.1111/cyt.12132Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Vigliar E., Cozzolino I., Picardi M., Peluso A.L., Fernandez L.V., Vetrani A., et al., Lymph node fine needle cytology in the staging and follow-up of cutaneous lymphomas, BMC Cancer., 2014, 14, 810.1186/1471-2407-14-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] [49] Zeppa P., Sosa Fernandez L.V., Cozzolino I., Ronga V., Genesio R., Salatiello M., et al., Immunoglobulin heavy-chain fluorescence in situ hybridization-chromogenic in situ hybridization DNA probe split signal in the clonality assessment of lymphoproliferative processes on cytological samples, Cancer Cytopathol., 2012, 120, 390-400.10.1002/cncy.21203Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Peluso A.L., Cascone A.M., Lucchese L., Cozzolino I., Ieni A., Mignogna C., et al., Use of FTA cards for the storage of breast carcinoma nucleic acid on fine-needle aspiration samples, Cancer Cytopathol., 2015, 123, 582-59210.1002/cncy.21577Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Zeppa P., Barra E., Napolitano V., Cozzolino I., Troncone G., Picardi M., et al., Impact of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in lymph nodal and mediastinal lesions: a multicenter experience, Diagn Cytopathol., 2011, 39, 723-72910.1002/dc.21450Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Di Crescenzo V., Laperuta P., Napolitano F., Carlomagno C., Danzi M., Amato B., et al., Unusual case of exacerbation of sub-acute descending necrotizing mediastinitis, BMC Surg., 2013, 13 Suppl 2, S3110.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S31Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Di Crescenzo V., Laperuta P., Napolitano F., Carlomagno C., Garzi A., Vitale M., Pulmonary sequestration presented as massive left hemothorax and associated with primary lung sarcoma, BMC Surg., 2013, 13 Suppl 2, S3410.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S34Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Di Crescenzo V., Vitale M., Valvano L., Napolitano F., Vatrella A., Zeppa P., et al., Surgical management of cervico-mediastinal goiters: Our experience and review of the literature, Int J Surg., 2016, 28 Suppl 1, S47-5310.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.048Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Serio B., Pezzullo L., Giudice V., Fontana R., Annunziata S., Ferrara I., et al., OPSI threat in hematological patients, Transl Med UniSa., 2013, 6, 2-10Search in Google Scholar

[56] Romano F., Caprotti R., Conti M., Piacentini M.G., Uggeri F., Motta V., et al., Thrombosis of the splenoportal axis after splenectomy, Langenbecks. Arch Surg., 2006, 391, 483-48810.1007/s00423-006-0075-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2016 Valentina Giudice et al.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- The possible molecular regulation mechanism of CIK cells inhibiting the proliferation of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma NCL-H157 Cells

- Case Report

- Urethral stone of unexpected size: case report and short literature review

- Case Report

- Complete remission through icotinib treatment in Non-small cell lung cancer epidermal growth factor receptor mutation patient with brain metastasis: A case report

- Research Article

- FPL tendon thickness, tremor and hand functions in Parkinson’s disease

- Research Article

- Diagnostic value of circulating tumor cells in cerebrospinal fluid

- Research Article

- A meta-analysis of neuroprotective effect for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the treatment of glaucoma

- Research Article

- MiR-218 increases sensitivity to cisplatin in esophageal cancer cells via targeting survivin expression

- Research Article

- Association of HOTAIR expression with PI3K/Akt pathway activation in adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction

- Research Article

- The role of interleukin genes in the course of depression

- Case Report

- A rare case of primary pulmonary diffuse large B cell lymphoma with CD5 positive expression

- Research Article

- DWI and SPARCC scoring assess curative effect of early ankylosing spondylitis

- Research Article

- The diagnostic value of serum CEA, NSE and MMP-9 for on-small cell lung cancer

- Case Report

- Dysphonia – the single symptom of rifampicin resistant laryngeal tuberculosis

- Review Article

- Development of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors against EGFR T790M. Mutation in non small-cell lung carcinoma

- Research Article

- Negative regulation of CDC42 expression and cell cycle progression by miR-29a in breast cancer

- Research Article

- Expression analysis of the TGF-β/SMAD target genes in adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction

- Research Article

- Blood cells in thyroid cancer patients: a possible influence of apoptosis

- Research Article

- Detected EGFR mutation in cerebrospinal fluid of lung adenocarcinoma patients with meningeal metastasis

- Mini-review

- Pathogenesis-oriented approaches for the management of corticosteroid-resistant or relapsedprimary immune thrombocytopenia

- Research Article

- GSTP1 A>G polymorphism and chemosensitivity of osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis

- Research Article

- A meta-analysis of adiponectin gene rs22411766 T>G polymorphism and ischemic stroke susceptibility

- Research Article

- The diagnosis and pathological value of combined detection of HE4 and CA125 for patients with ovarian cancer

- Research Article

- SOX7 inhibits tumor progression of glioblastoma and is regulated by miRNA-24

- Research Article

- Sevoflurane affects evoked electromyography monitoring in cerebral palsy

- Case Report

- A case report of hereditary spherocytosis with concomitant chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Case Report

- A case of giant saphenous vein graft aneurysm followed serially after coronary artery bypass surgery

- Research Article

- LncRNA TUG1 is upregulated and promotes cell proliferation in osteosarcoma

- Review Article

- Meningioma recurrence

- Case Report

- Endobronchial amyloidosis mimicking bronchial asthma: a case report and review of the literature

- Case Report

- A confusing case report of pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis and literature review

- Research Article

- Effect of hesperetin on chaperone activity in selenite-induced cataract

- Research Article

- Clinical value of self-assessment risk of osteoporosis in Chinese

- Research Article

- Correlation analysis of VHL and Jade-1 gene expression in human renal cell carcinoma

- Research Article

- Is acute appendicitis still misdiagnosed?

- Retraction

- Retraction of: application of food-specific IgG antibody detection in allergy dermatosis

- Review Article

- Platelet Rich Plasma: a short overview of certain bioactive components

- Research Article

- Correlation between CTLA-4 gene rs221775A>G single nucleotide polymorphism and multiple sclerosis susceptibility. A meta-analysis

- Review Article

- Standards of anesthesiology practice during neuroradiological interventions

- Research Article

- Expression and clinical significance of LXRα and SREBP-1c in placentas of preeclampsia

- Letter to the Editor

- ARDS diagnosed by SpO2/FiO2 ratio compared with PaO2/FiO2 ratio: the role as a diagnostic tool for early enrolment into clinical trials

- Research Article

- Impact of sensory integration training on balance among stroke patients: sensory integration training on balance among stroke patients

- Review Article

- MicroRNAs as regulatory elements in psoriasis

- Review Article

- Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and postpandemic influenza in Lithuania

- Review Article

- Garengeot’s hernia: two case reports with CT diagnosis and literature review

- Research Article

- Concept of experimental preparation for treating dentin hypersensitivity

- Research Article

- Hydrogen water reduces NSE, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Research Article

- Xanthogranuloma of the sellar region diagnosed by frozen section

- Case Report

- Laparoscopic antegrade cholecystectomy: a standard procedure?

- Case Report

- Maxillary fibrous dysplasia associated with McCune-Albright syndrome. A case study

- Regular Article

- Sialoendoscopy, sialography, and ultrasound: a comparison of diagnostic methods

- Research Article

- Antibody Response to Live Attenuated Vaccines in Adults in Japan

- Conference article

- Excellence and safety in surgery require excellent and safe tutoring

- Conference article

- Suggestions on how to make suboptimal kidney transplantation an ethically viable option

- Regular Article

- Ectopic pregnancy treatment by combination therapy

- Conference article

- Use of a simplified consent form to facilitate patient understanding of informed consent for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Regular Article

- Cusum analysis for learning curve of videothoracoscopic lobectomy

- Regular Article

- A meta-analysis of association between glutathione S-transferase M1 gene polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease susceptibility

- Conference article

- Plastination: ethical and medico-legal considerations

- Regular Article

- Investigation and control of a suspected nosocomial outbreak of pan-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an intensive care unit

- Regular Article

- Multifactorial analysis of fatigue scale among nurses in Poland

- Regular Article

- Smoking cessation for free: outcomes of a study of three Romanian clinics

- Regular Article

- Clinical efficacy and safety of tripterygium glycosides in treatment of stage IV diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Prevention and treatment of peritoneal adhesions in patients affected by vascular diseases following surgery: a review of the literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Surgical treatment of recidivist lymphedema

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- CT and MR imaging of the thoracic aorta

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Role of FDG-PET scan in staging of pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Sternal reconstruction by extracellular matrix: a rare case of phaces syndrome

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Prenatal diagnosis, 3-D virtual rendering and lung sparing surgery by ligasure device in a baby with “CCAM and intralobar pulmonary sequestration”

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Serum levels of inhibin B in adolescents after varicocelelectomy: A long term follow up

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Our experience in the treatment of Malignant Fibrous Hystiocytoma of the larynx: clinical diagnosis, therapeutic approach and review of literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Delayed recurrent nerve paralysis following post-traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysm

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Integrated therapeutic approach to giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: report of a case and review of the literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Celiac axis compression syndrome: laparoscopic approach in a strange case of chronic abdominal pain in 71 years old man

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- A rare case of persistent hypoglossal artery associated with contralateral proximal subclavian stenosis

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Contralateral risk reducing mastectomy in Non-BRCA-Mutated patients

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Professional dental and oral surgery liability in Italy: a comparative analysis of the insurance products offered to health workers

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Informed consent in robotic surgery: quality of information and patient perception

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Malfunctions of robotic system in surgery: role and responsibility of surgeon in legal point of view

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Medicolegal implications of surgical errors and complications in neck surgery: A review based on the Italian current legislation

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Iatrogenic splenic injury: review of the literature and medico-legal issues

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Donation of the body for scientific purposes in Italy: ethical and medico-legal considerations

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Cosmetic surgery: medicolegal considerations

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Voluntary termination of pregnancy (medical or surgical abortion): forensic medicine issues

- Review Article

- Role of Laparoscopic Splenectomy in Elderly Immune Thrombocytopenia

- Review Article

- Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system

- Review Article

- Efficacy and safety of splenectomy in adult autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Research Article

- Relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and Ph nose and salivary: proposal of a simple method outpatient in patients adults

- Case Report

- Idiopathic pleural panniculitis with recurrent pleural effusion not associated with Weber-Christian disease

- Research Article

- Morbid Obesity: treatment with Bioenterics Intragastric Balloon (BIB), psychological and nursing care: our experience

- Research Article

- Learning curve for endorectal ultrasound in young and elderly: lights and shades

- Case Report

- Uncommon primary hydatid cyst occupying the adrenal gland space, treated with laparoscopic surgical approach in an old patient

- Research Article

- Distraction techniques for face and smile aesthetic preventing ageing decay

- Research Article

- Preoperative high-intensity training in frail old patients undergoing pulmonary resection for NSCLC

- Review Article

- Descending necrotizing mediastinitis in the elderly patients

- Research Article

- Prophylactic GSV surgery in elderly candidates for hip or knee arthroplasty

- Research Article

- Diagnostic yield and safety of C-TBNA in elderly patients with lung cancer

- Research Article

- The learning curve of laparoscopic holecystectomy in general surgery resident training: old age of the patient may be a risk factor?

- Research Article

- Self-gripping mesh versus fibrin glue fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a randomized prospective clinical trial in young and elderly patients

- Research Article

- Anal sphincter dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: an observation manometric study

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- The possible molecular regulation mechanism of CIK cells inhibiting the proliferation of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma NCL-H157 Cells

- Case Report

- Urethral stone of unexpected size: case report and short literature review

- Case Report

- Complete remission through icotinib treatment in Non-small cell lung cancer epidermal growth factor receptor mutation patient with brain metastasis: A case report

- Research Article

- FPL tendon thickness, tremor and hand functions in Parkinson’s disease

- Research Article

- Diagnostic value of circulating tumor cells in cerebrospinal fluid

- Research Article

- A meta-analysis of neuroprotective effect for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the treatment of glaucoma

- Research Article

- MiR-218 increases sensitivity to cisplatin in esophageal cancer cells via targeting survivin expression

- Research Article

- Association of HOTAIR expression with PI3K/Akt pathway activation in adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction

- Research Article

- The role of interleukin genes in the course of depression

- Case Report

- A rare case of primary pulmonary diffuse large B cell lymphoma with CD5 positive expression

- Research Article

- DWI and SPARCC scoring assess curative effect of early ankylosing spondylitis

- Research Article

- The diagnostic value of serum CEA, NSE and MMP-9 for on-small cell lung cancer

- Case Report

- Dysphonia – the single symptom of rifampicin resistant laryngeal tuberculosis

- Review Article

- Development of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors against EGFR T790M. Mutation in non small-cell lung carcinoma

- Research Article

- Negative regulation of CDC42 expression and cell cycle progression by miR-29a in breast cancer

- Research Article

- Expression analysis of the TGF-β/SMAD target genes in adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction

- Research Article

- Blood cells in thyroid cancer patients: a possible influence of apoptosis

- Research Article

- Detected EGFR mutation in cerebrospinal fluid of lung adenocarcinoma patients with meningeal metastasis

- Mini-review

- Pathogenesis-oriented approaches for the management of corticosteroid-resistant or relapsedprimary immune thrombocytopenia

- Research Article

- GSTP1 A>G polymorphism and chemosensitivity of osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis

- Research Article

- A meta-analysis of adiponectin gene rs22411766 T>G polymorphism and ischemic stroke susceptibility

- Research Article

- The diagnosis and pathological value of combined detection of HE4 and CA125 for patients with ovarian cancer

- Research Article

- SOX7 inhibits tumor progression of glioblastoma and is regulated by miRNA-24

- Research Article

- Sevoflurane affects evoked electromyography monitoring in cerebral palsy

- Case Report

- A case report of hereditary spherocytosis with concomitant chronic myelocytic leukemia

- Case Report

- A case of giant saphenous vein graft aneurysm followed serially after coronary artery bypass surgery

- Research Article

- LncRNA TUG1 is upregulated and promotes cell proliferation in osteosarcoma

- Review Article

- Meningioma recurrence

- Case Report

- Endobronchial amyloidosis mimicking bronchial asthma: a case report and review of the literature

- Case Report

- A confusing case report of pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis and literature review

- Research Article

- Effect of hesperetin on chaperone activity in selenite-induced cataract

- Research Article

- Clinical value of self-assessment risk of osteoporosis in Chinese

- Research Article

- Correlation analysis of VHL and Jade-1 gene expression in human renal cell carcinoma

- Research Article

- Is acute appendicitis still misdiagnosed?

- Retraction

- Retraction of: application of food-specific IgG antibody detection in allergy dermatosis

- Review Article

- Platelet Rich Plasma: a short overview of certain bioactive components

- Research Article

- Correlation between CTLA-4 gene rs221775A>G single nucleotide polymorphism and multiple sclerosis susceptibility. A meta-analysis

- Review Article

- Standards of anesthesiology practice during neuroradiological interventions

- Research Article

- Expression and clinical significance of LXRα and SREBP-1c in placentas of preeclampsia

- Letter to the Editor

- ARDS diagnosed by SpO2/FiO2 ratio compared with PaO2/FiO2 ratio: the role as a diagnostic tool for early enrolment into clinical trials

- Research Article

- Impact of sensory integration training on balance among stroke patients: sensory integration training on balance among stroke patients

- Review Article

- MicroRNAs as regulatory elements in psoriasis

- Review Article

- Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and postpandemic influenza in Lithuania

- Review Article

- Garengeot’s hernia: two case reports with CT diagnosis and literature review

- Research Article

- Concept of experimental preparation for treating dentin hypersensitivity

- Research Article

- Hydrogen water reduces NSE, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Research Article

- Xanthogranuloma of the sellar region diagnosed by frozen section

- Case Report

- Laparoscopic antegrade cholecystectomy: a standard procedure?

- Case Report

- Maxillary fibrous dysplasia associated with McCune-Albright syndrome. A case study

- Regular Article

- Sialoendoscopy, sialography, and ultrasound: a comparison of diagnostic methods

- Research Article

- Antibody Response to Live Attenuated Vaccines in Adults in Japan

- Conference article

- Excellence and safety in surgery require excellent and safe tutoring

- Conference article

- Suggestions on how to make suboptimal kidney transplantation an ethically viable option

- Regular Article

- Ectopic pregnancy treatment by combination therapy

- Conference article

- Use of a simplified consent form to facilitate patient understanding of informed consent for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Regular Article

- Cusum analysis for learning curve of videothoracoscopic lobectomy

- Regular Article

- A meta-analysis of association between glutathione S-transferase M1 gene polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease susceptibility

- Conference article

- Plastination: ethical and medico-legal considerations

- Regular Article

- Investigation and control of a suspected nosocomial outbreak of pan-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an intensive care unit

- Regular Article

- Multifactorial analysis of fatigue scale among nurses in Poland

- Regular Article

- Smoking cessation for free: outcomes of a study of three Romanian clinics

- Regular Article

- Clinical efficacy and safety of tripterygium glycosides in treatment of stage IV diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Prevention and treatment of peritoneal adhesions in patients affected by vascular diseases following surgery: a review of the literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Surgical treatment of recidivist lymphedema

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- CT and MR imaging of the thoracic aorta

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Role of FDG-PET scan in staging of pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Sternal reconstruction by extracellular matrix: a rare case of phaces syndrome

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Prenatal diagnosis, 3-D virtual rendering and lung sparing surgery by ligasure device in a baby with “CCAM and intralobar pulmonary sequestration”

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Serum levels of inhibin B in adolescents after varicocelelectomy: A long term follow up

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Our experience in the treatment of Malignant Fibrous Hystiocytoma of the larynx: clinical diagnosis, therapeutic approach and review of literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Delayed recurrent nerve paralysis following post-traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysm

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Integrated therapeutic approach to giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: report of a case and review of the literature

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- Celiac axis compression syndrome: laparoscopic approach in a strange case of chronic abdominal pain in 71 years old man

- Special Issue on Italian Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies

- A rare case of persistent hypoglossal artery associated with contralateral proximal subclavian stenosis

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Contralateral risk reducing mastectomy in Non-BRCA-Mutated patients

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Professional dental and oral surgery liability in Italy: a comparative analysis of the insurance products offered to health workers

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Informed consent in robotic surgery: quality of information and patient perception

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Malfunctions of robotic system in surgery: role and responsibility of surgeon in legal point of view

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Medicolegal implications of surgical errors and complications in neck surgery: A review based on the Italian current legislation

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Iatrogenic splenic injury: review of the literature and medico-legal issues

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Donation of the body for scientific purposes in Italy: ethical and medico-legal considerations

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Cosmetic surgery: medicolegal considerations

- Focus on Medico-Legal and Ethical Topics in Surgery in Italy

- Voluntary termination of pregnancy (medical or surgical abortion): forensic medicine issues

- Review Article

- Role of Laparoscopic Splenectomy in Elderly Immune Thrombocytopenia

- Review Article

- Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system

- Review Article

- Efficacy and safety of splenectomy in adult autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Research Article

- Relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and Ph nose and salivary: proposal of a simple method outpatient in patients adults

- Case Report

- Idiopathic pleural panniculitis with recurrent pleural effusion not associated with Weber-Christian disease

- Research Article

- Morbid Obesity: treatment with Bioenterics Intragastric Balloon (BIB), psychological and nursing care: our experience

- Research Article

- Learning curve for endorectal ultrasound in young and elderly: lights and shades

- Case Report

- Uncommon primary hydatid cyst occupying the adrenal gland space, treated with laparoscopic surgical approach in an old patient

- Research Article

- Distraction techniques for face and smile aesthetic preventing ageing decay

- Research Article

- Preoperative high-intensity training in frail old patients undergoing pulmonary resection for NSCLC

- Review Article

- Descending necrotizing mediastinitis in the elderly patients

- Research Article

- Prophylactic GSV surgery in elderly candidates for hip or knee arthroplasty

- Research Article

- Diagnostic yield and safety of C-TBNA in elderly patients with lung cancer

- Research Article

- The learning curve of laparoscopic holecystectomy in general surgery resident training: old age of the patient may be a risk factor?

- Research Article

- Self-gripping mesh versus fibrin glue fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a randomized prospective clinical trial in young and elderly patients

- Research Article

- Anal sphincter dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: an observation manometric study