Abstract

Background and aims

Recent studies reveal high prevalence rates of patients receiving long-term opioids. However, well designed studies assessing effectiveness with longer than 3 months follow-up are sparse. The present study investigated the outcomes of long-term opioid therapy compared to nonopioid treatment in CNCP patients with respect to measures of pain, functional disability, psychological wellbeing, and quality of life (QoL).

Methods

Three hundred and thirty three consecutive patients at our pain clinic were included and divided into patients with continuous opioid treatment for at least 3 months (51%) and patients receiving nonopioid analgesics (49%). Further, outcome of different doses of opioid (<120 mg vs. >120 mg morphine equivalents) and differences between high and low potency opioids were examined.

Results

The opioid and nonopioid groups did not differ with regard to pain intensity or satisfaction with analgesic. Patients with continuous opioids treatment reported higher neuropathic like pain, longer duration of pain disorder, lower functional level, wellbeing, and physical QoL in comparison to patients receiving nonopioid analgesics. Higher opioid doses were associated with male gender, intake of high potency opioids and depression but there were no differences with regard to pain relief or improvement of functional level between high and low doses. Similarly, patients on high potency opioids reported more psychological impairment than patients on low potency opioids but no advantage with regard to pain relief. Overall, remaining level of pain, functional disability and poor QoL were quite high irrespective of the analgesic used or opioid dosing.

Conclusions

In the long-term no clear advantage of opioid vs. non-opioid analgesics could be revealed. In terms of remaining pain intensity, functional disability and quality of life, treatment with pain medication proved insufficient. Additionally, with higher doses of opioids the benefit to risk relationship becomes worse and patients on high potency opioids reported more psychological impairment than patients on low potency opioids but no advantage with regard to pain relief.

Implications

Our results raise questions about the long-term effectiveness of analgesic treatment regimens irrespective of analgesics type employed and call for more multidisciplinary treatment strategies.

1 Introduction

Since the assumption of opioids as a promising therapy for patients with chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) during the 1990s, the use of opioid analgesics in this setting is now well established in modern medicine [1,2]. Empirically robust data demonstrate significant pain reduction with opioids in the short term compared to placebo [3,4]. Accordingly, data from North-America and Europe show continued increases in prescription rates and higher numbers of daily doses per recipient over the last few decades [1,2]. Additionally, increasing prevalence rates of long-term use have been reported with 85-96% of the patients continuing intake for 5-10 years after their first prescription [5,6]. However, whether opioids are superior to nonopioids even in the short-term [7] and whether long-term treatment with opioids is effective is still under debate.

Evidence of effectiveness of opioid therapy for treatment periods >3 months is limited as most studies focus on initial therapy effects during the first 6 to 12 weeks of treatment as recently pointed out by Welsch et al. [7] in a systematic review with a metaanalysis. Furthermore, most studies refer to pain reduction as the main outcome measure, whereas improvement of quality of life (QoL), daily functioning and wellbeing as potentially equally important treatment gains appear to be widely neglected in both the short- and long-term evaluation. Recent systematic literature reviews focusing on outcomes of opioid therapy over at least 6 months show insufficient evidence based on randomised control studies (RCTs) [8]. There are only single studies like the RCT by Breivik et al. [9], but their conclusions of better outcome with opioids are limited to osteoarthritis patients and buprenorphine.Just as important, there is also a lack of long-term opioid studies that evaluated effects on pain, function, or QoL in comparison to other treatment strategies such as nonopioid therapy [10]. Additionally, concerns about adverse effects need to be taken into account. Controlled studies point to a higher risk of overdose [11], myocardial infarction [12], and fractures with opioid analgesics [13,14]. Use of opioids has also been linked to an increased risk of depression [15] and hyperalgesia [16,17] prompting an ongoing debate about cause and consequence. Finally, drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of opioid therapy in CNCP is further complicated by dose dependent effects. Higher doses of opioids (above 120 mg morphine equivalent) have been found to be associated with a less favourable balance of benefit to risk compared to lower doses [12]. However, even at doses within a more typical therapeutic range, differential effects have been reported. A lower risk of fractures [18] and better QoL [19] were observed under low-dose opioid therapy (doses up to 50 mg) in comparison to higher opioid doses of up to 120 mg.

The aim of this study was to examine any superiority of long-term opioid treatment compared to nonopioid treatment strategies. Considering chronic pain as a multi-dimensional phenomena, treatment outcome was measured in terms of pain intensity scores, psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and functioning, as well as patient satisfaction with their treatment as a variable potentially influencing medication adherence [20]. A secondary aim was to identify differential effects of opioid dosing and opioid potency on long-term outcome.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study design

The present observational study has a cross sectional design.Data collection took place at one assessment occasion and comprised collection of interview and questionnaire data from the patients. As supplement, information with regard to diagnosis was extracted from the medical record. Assignment of the patients into the study groups is based on retrospective information about the history of analgesia intake (i.e. ex-post-facto).

2.2 Participants

Due to a power analysis a total sample of 210 would be required to detect medium effect sizes with regard to group differences. Considering the necessity of excluding patients and single missing data a higher number of patients were assessed in order to finally reach an adequate sample size for analyses.

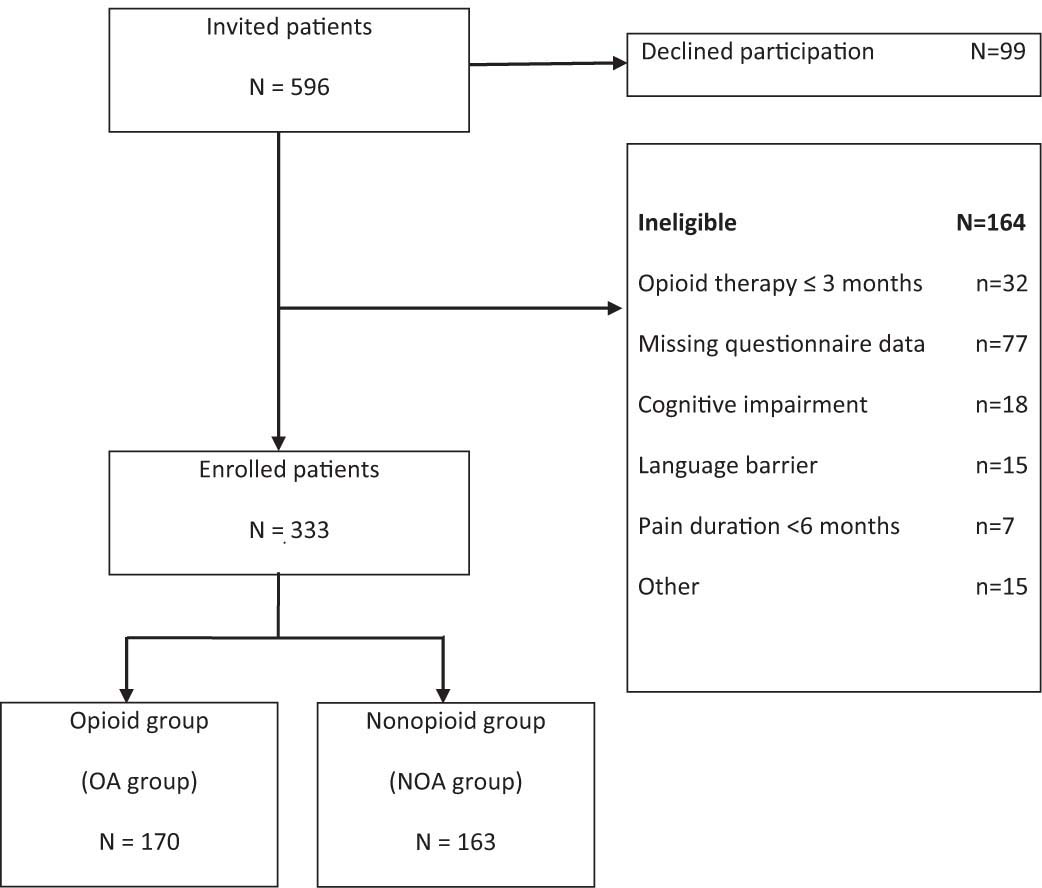

A total of 596 consecutive patients with chronic pain (>6 months) were enrolled from the pain management services at the Clinic for Pain Medicine of the Sankt Josef Krankenhaus, Wuppertal (Fig. 1). Inclusion criteria were: age above 18 years, fluency in German, and pain duration of at least 6 months. Participants with pain due to cancer, comorbid dementia, psychotic or bipolar disorder, and patients with a history of alcohol and/or opioid dependence were excluded.

Flow diagram for enrollment of potentially eligible participants.

A total of 99 patients (16.6%) refused to take part in the study. All other patients gave their informed consent. More than a quarter of the sample (N = 164; 27.5%) was excluded from further analysis due to reasons displayed in Fig. 1. The final study population included 333 patients which were assigned into two groups: The opioid analgesic group (OA group) comprises patients with continuous opioid intake during at least the previous 3 months. The nonopioid analgesic group (NOA group) include patients treated with different kinds of analgesics or coanalgesics but had not received opioids in the previous three months. Patients with opioid analgesics for less than three months were completely excluded from further analysis, as the study focused on long-term outcomes of opioids in comparison to treatment with nonopioids. Involvement in other kinds of treatment (e.g. physical therapy, TENS) did not lead to exclusion in any group.

With the given sample size of 333 patients, our study was adequately powered to detect medium and large effect sizes, but not smaller effects.

2.3 Procedure

Data collection took place during a scheduled medical consultation at the Clinic for Pain Medicine which serves as part of primary care for pain patients. No kind of remuneration was given. Patients who were willing to take part in the study were individually interviewed with regard to pain and medication related details and then asked to complete the German Pain Questionnaire (GPQ; German: Deutscher Schmerzfragebogen) [21], an instrument used in specialised pain medicine units in Germany. All patients at our Pain Clinic are routinely asked to fill in this comprehensive questionnaire booklet. Apart from diagnosis, medication related variables, satisfaction rating and QoL, all measures were extracted from the GPQ.

2.4 Questionnaires and measures

2.4.1 Pain and medication related details

Patients were asked to give details about duration of their pain and use of analgesic medication, name and dose of current and previously taken analgesics, adverse effects, and satisfaction with the current medication in a semi-structured interview. Diagnosis based on multi-professional judgements were extracted from the medical record and summarised according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10)[22] into groups with pain due to disorders of the musculoskeletal system, nervous system or mental/behavioural disorders. The remains were gathered into a group of pain associated with other disorders. Individual opioid dose per day was converted into oral morphine equianalgesic dose by referring to the publicly available reference chart from the Pain Clinic at the University of Göttingen [23]. The used conversion factors are displayed in Table 1. If more than one opioid analgesic was used by a patient at the same time, a sum score was calculated after converting oral morphine equianalgesic dose for each opioid separately. Additionally, analgesic intake was classified according to the WHO three-step pain relief ladder, thereby differentiating between low and high potency opioids (Table 1). Apart from tilidine and tramadol, tapentadol was classified as stage 2 or low potency opioid due to a lower potency in comparison to morphine and an ongoing discussion about WHO classification [24]. Generic names of stage 3 or high potency opioids prescribed to patients of our sample are listed in Table 1. In case of the use of more than one opioid at the time of data collection, the one with the highest opioid potency determined classification.

Prescribed opioids within the OAgroup, assigned WHO-stage and conversion factors used to calculate oral morphine equianalgesic dose.

| Generic name of analgesic | WHO stage | Conversion factor |

|---|---|---|

| Buprenorphine TDS (μg/h) | 3 | 0.57 |

| Fentanyl TTS (μg/h) | 3 | 0.4 |

| Hydromorphone | 3 | 0.13 |

| Morphine | 3 | 1 |

| Oxycodone with/without Naloxone | 3 | 0.65 |

| Tapendadol | 2 | 3.3 |

| Tilidine | 2 | 5 |

| Tramadol | 2 | 5 |

-

Oral morphine equianalgesics = individual dose/conversion factor

Satisfaction with the pain medication: Patients were asked to rate their satisfaction with pain medication on a numeric rating scale (NRS) ranging from 1 (very good) to 6 (totally insufficient). A rating with an even number was chosen for this self-designed scale in order to avoid indecisive answers. In cases of more than one analgesic medication, only the satisfaction with the leading medication currently taken was included in the statistical analysis. Leading medication was defined as the one with the highest WHO stage. In case of intake of more than one NOA the one rated by the patient as the major analgesic was taken into account. Different OA’s from the same stage were taken in 7 cases. In each case, one of the opioid’s served as a rescue analgesic. The regularly taken OA was defined as leading medication.

Pain severity and functioning: two pain severity measures of the GPQ were used in our study: (1) peak pain intensity during the last 4 weeks and (2) average pain intensity during the last 4 weeks. Patients are asked to indicate these pain intensities on separate NRS’s each ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). The modified Pain Disability Index (mPDI) is a shortened version of the Pain Disability Index [25] comprising 5 of the original 7 items. Patients are asked to indicate the degree to which pain interferes with functioning in five areas of daily life: family/home activities, recreation, social activity, occupation, and self-care (possible range: 0-50; higher is worse).

As a grading measure of pain severity and disability, the Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPG) [26] was used. This measure classifies patients based on intensity, persistence and disability/interference scores into 5 hierarchical grades: Grade zero (pain free), Grade I (low disability-low intensity), Grade II (low disability-high intensity), Grade III (high disability-moderately limiting), and Grade IV (high disability-severely limiting). Frequencies of grades in percent are given in the results.

Neuropathic pain: the neuropathic pain scale included in the GPQis based on the items of the painDETECT questionnaire [27]. For identification of neuropathic pain components patients are asked to indicate the intensity of 7 descriptors of neuropathic pain on a 6- point rating scale (0 = never occurring to 5 = very strong) with a total score range from 0 to 35; scores below 10 indicate nociceptive pain, those above 17 neuropathic like pain, and scores between 10 and 17 are classified as pain with doubtfully neuropathic component.

2.4.2 Psychological variables

QoL: The WHOQoL-BREF [28] is a 26 item questionnaire allowing an assessment of four dimensions of QoL, namely physical (7 items), psychological (6 items), social relationships (3 items), environmentally related (8 items) and a global rating of QoL (2 items). Possible range for all scales: 0-100; lower is worse.

As an additional measure of QoL the SF-12 Health Survey [29] was administered but excluded from data analysis due to too many missing data.

General wellbeing: the Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health (MQHH; original German version: Fragebogen zum Habituellen Wohlbefinden) by Herda et al. [30] is a seven item scale for the assessment of the trait dimension of well-being, which is thought to be a part of QoL (range 1-6; lower is worse).

Depression and anxiety: the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [31,32] is a 14 item tool designed for the detection of anxiety and depression in people with physical health problems (7 items relate to anxiety and 7 items relate to depression with a range of 0-21 for each subscale; higher is worse; cut-off >11).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Continuous data were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with group (OA vs. NOA) and opioid dose (<120 mg vs. >120 mg) as factors, respectively. Due to a significant age difference between the OA and NOA groups, additional analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) with age as control variable and group as between participant factor were carried out and are presented in the results section. Differences with regard to frequency and percentages of variables were tested by Chi2-tests. Furthermore, as complementary analyses differences between OA and NOA patients were retested with a subgroup of OA patients with continuous opioid intake >6 months, allowing to extend conclusions on longer durations of opioid intake. ANOVA’s with opioid potency (low versus high) as between subject factor within the OA group aims on providing information about differential outcomes depending on opioid potency.

For an exploratory analysis of relationships between the dimensions of chronic pain Pearson product-moment correlations were calculated. Associations were determined for the patients with chronic pain (OA and NOA groups combined) as well as within the OA group with all continuous measures. For reasons of clarity, report of correlational coefficients in the results section refers to significant associations between medical variables (i.e. pain and analgesic related measures), functional outcome, QoL, and the psychological wellbeing measures, respectively. Other coefficients of subordinated interest for the present study, e.g. intercorrelations between psychological measures were omitted.

In the case of any significant association for the combined group or the OA group, additional tests on significant differences between the correlational coefficients were implemented (Fisher Z-test for the difference of correlational coefficients).

3 Results

Fifty one percent of our study population (N=170) were assigned to the OA group. The list of prescribed opioids within the OAgroup comprised: buprenorphine (7.1%), fentanyl (10%), hydro-morphone (10%), morphine (6.5%), oxycodone (9.4%), oxycodone plus naloxone (10.6%), tapentadol (9.4%), tilidine (28.2%), and tramadol (8.8%). The remaining 163 (49%) patients were assigned to the NOA group, which were treated with different kinds of analgesics or coanalgesics, e.g. NSAIDS, anticonvulsants, antidepressants or muscle relaxants but not with opioids in the previous three months.

3.1 Differences between the OA and NOA group

Demographic, clinical and psychological characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 2. Both study groups are comparable with regard to sex and marital status. Around two third of the patients were female and nearly half of them were married. Mean age in the OA group was 65.9 years and significantly higher than that of the NOA group with 62.7 years. In line with older age, a higher proportion of OA than NOA patients were already retired (67% vs. 53.5%).

Mean (SD) of sociodemographic, clinical and psychological characteristics of the study population.

| Variables | Nonopioid group N = 163 | Opioid group N = 170 | Significant results[a] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.74 (15.34) | 65.86 (13.48) | F1,332 = 3.98, P = .05 |

| Sex (female) % | 76.2 | 73.5 | |

| Marital status: married % | 48.1 | 51.2 | |

| Employment % | |||

| Full or part time | 25.8 | 17.7 |

|

| Unemployed | 6.9 | 3.7 | |

| Retired/disabled | 53.5 | 67.0 | |

| Others | 13.8 | 11.6 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Duration of pain (months) | 94.14 (103.76) | 156.46 (141.13) | F 1,326 = 18.09, P=.000 |

| Pain intensity (0-10[b]) | |||

| Average | 6.86 (1.82) | 7.11 (1.74) | |

| Peak | 8.75 (1.24) | 8.72 (1.54) | |

| Months of analgesic intake | |||

| Overall | 62.45 (75.39) | 104.73 (111.39) | F1,302 = 13.2, P =.000 |

| Continuously NOA for | 35.53 (63.01) | 33.97 (55.86) | |

| Continuously OA for | - | 36.65 (38.41) | |

| ICD-diagnosis group % | |||

| M. musculoskeletal | 76.8 | 77.1 | |

| G. nervous system | 5.5 | 4.1 | |

| F. mental/behavioural | 8.5 | 11.2 | |

| others | 9.1 | 7.6 | |

| CPG % | |||

| Low disability | |||

| Low pain intensity | 2.3 | 2.3 | |

| High pain intensity | 5.8 | 2.3 | |

| High disability | |||

| Moderately limiting | 14.0 | 13.6 | |

| Severely limiting | 77.9 | 81.8 | |

| WHO stage of analgesics[c] % | |||

| None | 25.8 | 0.0 |

|

| Stage 1 | 74.2 | 0.0 | |

| Stage 2 | 0.0 | 45.3 | |

| Stage 3 | 0.0 | 54.7 | |

| Satisfaction with analgesic (1-6[b]) | 3.43 (1.28) | 3.26 (1.34) | |

| Opioid dose[d] (mg) | - | 80.84 (72.79) | |

| Neuropathic pain score (0-35[b]) | 12.57 (6.94) | 14.63 (7.39) | F 1,291 = 9.60, P = .002 |

| Psychological characteristics | |||

| HADS - depression (0-21[b]) | 9.07 (4.39) | 10.01 (4.26) | F 1,301 = 3.61, P = .06 |

| HADS - anxiety (0-21[b]) | 8.60 (4.39) | 9.06 (4.08) | |

| mPDI - functional disability (0-50[b]) | 33.45 (8.20) | 35.78 (7.60) | F 1,288 =5.78, P=.02 |

| MQHH - habitual wellbeing (0-6[b]) | 1.68 (1.26) | 1.37 (1.07) | F 1,285 = 4.54, P=.03 |

| WHOQOL-BREF (0-100[b]) | |||

| Physical | 41.59 (14.00) | 37.79 (14.73) | F 1,309 = 6.87, P = .01 |

| Psychological | 57.53 (17.42) | 54.54 (18.83) | F 1,312 = 2.99, P = .08 |

| Social relationships | 62.36 (19.98) | 62.16 (20.17) | |

| Environmentally related | 65.92 (13.57) | 64.07 (14.81) | |

| Global score | 37.90 (16.77) | 36.51 (17.51) | |

-

CPG = Chronic Pain Grade Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; mPDI = modified Pain Disability Index; MQHH = The Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health; NOA = nonopioid analgesics; OA = opioid analgesics; WHO = World Health Organisation; WHOQoL-Bref = World Health Organisation Quality of Life - Short Version

With regard to medical and pharmaceutical variables, the OA group reported statistically significantly longer duration of pain and longer time of analgesic intake (i.e. NOA and/or OA not necessarily on a continuous basis) than the NOA group. Time of any analgesic intake ranged from less than 1 month (due to a patient in the NOA group) up to 54 years. Both groups reported comparable duration of continuous NOA intake for approximately three years. Prescription time of opioids in the OA group varied between 3 months and 15 years with an average time of intake of about 3 years. Furthermore, pain intensity scores and CPG as a combined measure of pain intensity and disability yielded no significant group differences. In both groups, average pain intensity during the last four weeks was rated as 7/10, indicating a rather high degree of continuous pain throughout the last month. Approximately 80% of the patients felt highly disabled and severely limited due to their pain disorder as indicated by CPG stage.

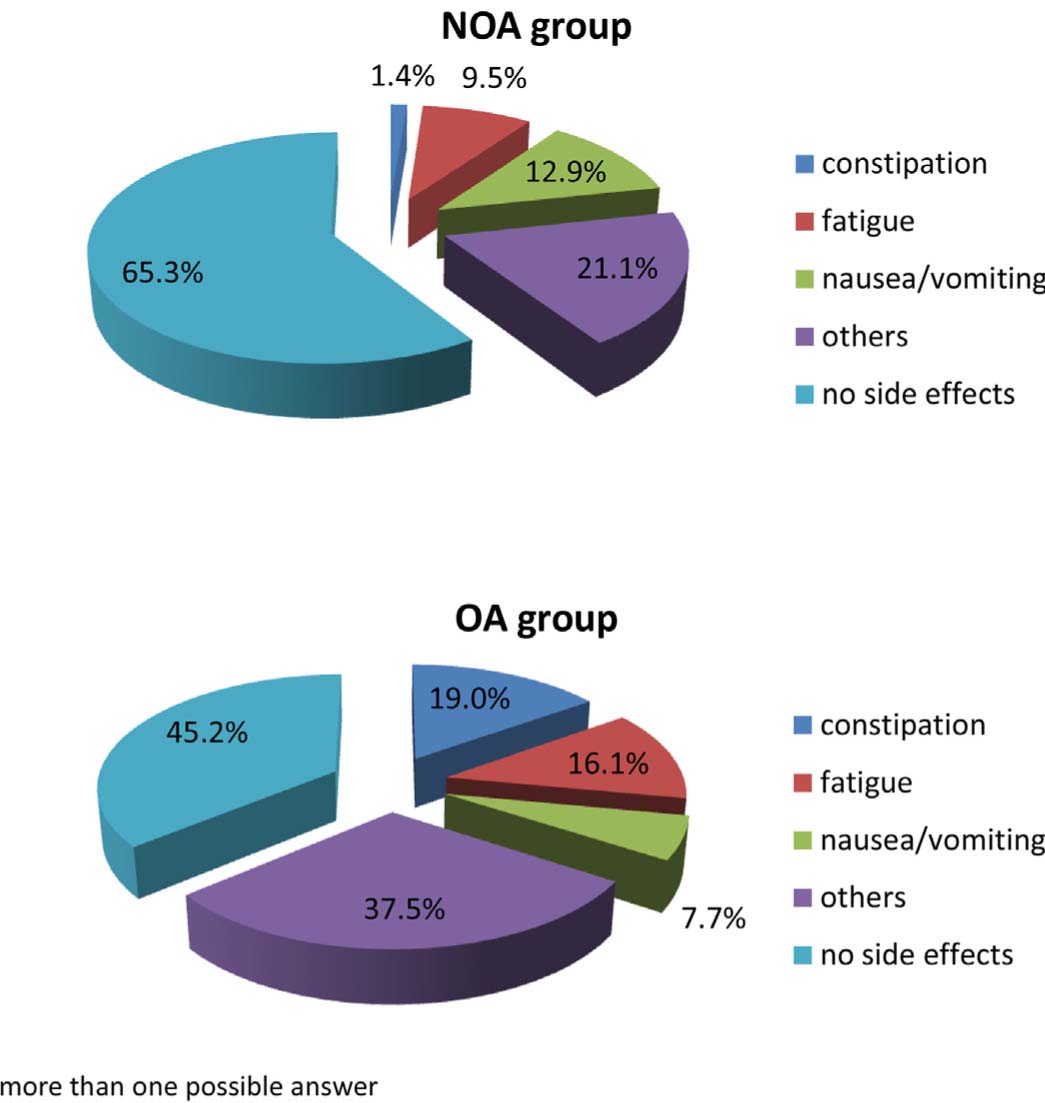

Analgesic prescription and intake was mainly due to disorders of the musculoskeletal system (77%) and other somatic disorders. Nevertheless, around 10% of patients with mental disorders (mainly somatoform spectrum disorders) were also treated with opioid or nonopioid analgesics. As expected, groups differed significantly in terms of WHO stage and nearly 55% of the OA group was treated with high potency opioids. However, satisfaction with the pain medication did not differ between the study groups. On the NRS ranging from 1 (very good) to 6 (totally insufficient) scores ranged in the middle of the scale, thereby indicating that treatment was more or less adequate. The proportion of patients with notable adverse effects and type of adverse effect varied significantly between groups (Fig. 2). A higher proportion (65%) of patients in the OA treatment group in contrast to NOA treatment (45%) reported adverse effects. Constipation and fatigue were most frequent in the OA group whereas nausea and vomiting occurred most with NOA treatment.

Proportion and type of adverse effects for the OA and NOA groups.

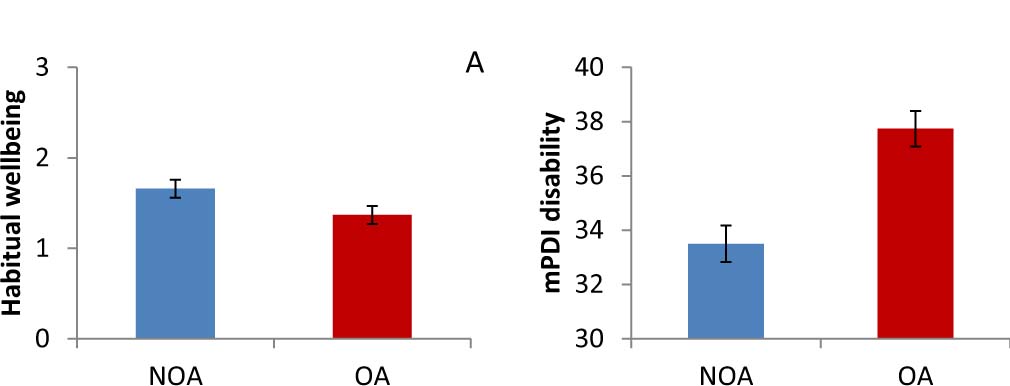

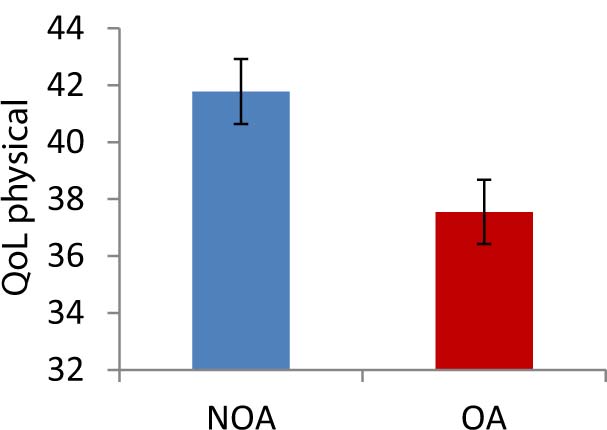

Analysis of psychological variables indicated a significantly greater impairment in the OA group compared to the NOA group with regard to habitual wellbeing, disability scores, and physical QoL (Figs. 3 and 4). Further results approaching significance (>.05 P<.10) are listed in the tables.

Age-adjusted mean scores of habitual wellbeing (A) and pain disability (B) in the NOA and the OA group. Error bars represent standard error.

Age-adjusted mean scores of physical QoL in the NOA and OA groups. Error bars represent standard error.

3.2 Differences between opioid doses above and below 120 mg

The daily opioid dose varied widely between 2 mg/day and 360 mg/day morphine equivalents. In accordance with contemporary guidelines for long-term opioid therapy [33] high dose was defined as >120 mg morphine equivalents per day. Patients in the OA group were split into two subgroups with doses either below 120 mg or in the high dose group >120 mg.

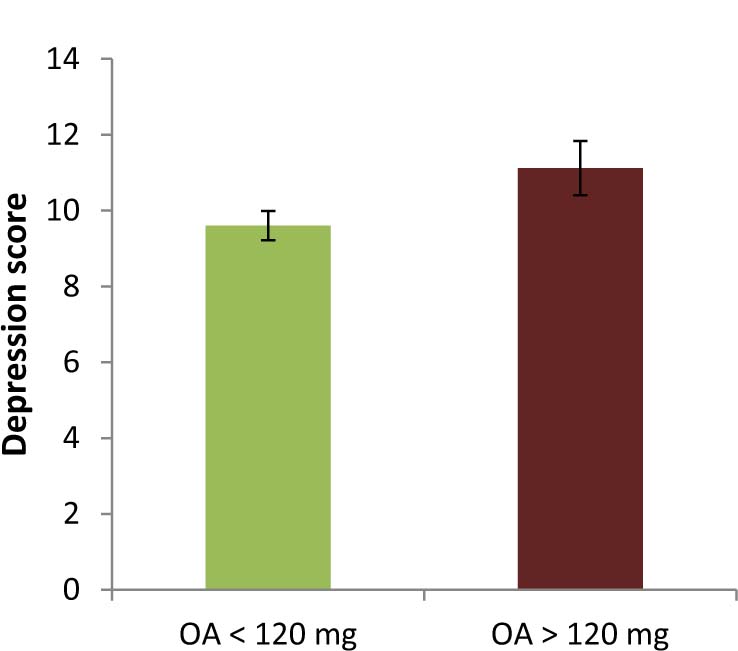

Around a quarter of the OA treated patients needed to be assigned to the high dose group (N = 45). Table 3 summarises characteristics of high dose users compared to patients consuming doses below 120 mg. There was a higher proportion of male and married patients in the group with OA doses above 120 mg, and high dose use was more frequent for patients with high potency (WHO stage 3) opioids. Further, patients with high dosages reported higher depression scores (Fig. 5) and longer duration of pain but no difference with regard to overall time of analgesic intake or pain intensity ratings.

Mean (SD) of sociodemographic, clinical and psychological characteristics of chronicpain patients with morphine dose <120 mg versus >120 mg.

| Variables | Opioid<120 mg N = 125 | Opioih>120 mg N = 45 | Significant results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.84 (13.16) | 65.93 (14.49) | |

| Sex (female)% | 77.6 | 62.2 |

|

| Marital status: married % | 45.2 | 69 |

|

| Employment % | |||

| Full or part time | 19.7 | 11.9 | |

| Unemployed | 3.3 | 4.8 | |

| Retired/disabled | 68.0 | 64.3 | |

| Others | 9.0 | 19.0 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Duration of pain (months) | 144.94 (128.07) | 189.18 (170.41) | F 1,168 = 3.25, P =.07 |

| Pain intensity (0-10[a]) | |||

| Average | 7.03 (1.78) | 7.33 (1.65) | |

| Peak | 8.70 (1.40) | 8.77 (1.87) | |

| Months of analgesic intake | |||

| Overall | 99.63 (109.73) | 120.18 (116.39) | |

| Continuously NOA for | 35.33 (56.82) | 29.87 (53.38) | |

| Continuously OA for | 33.97 (37.58) | 44.46 (40.17) | |

| ICD-diagnosis group % | |||

| M. musculoskeletal | 73.6 | 86.7 | |

| G. nervous system | 4.0 | 4.4 | |

| F. mental/behavioural | 12.0 | 8.9 | |

| others | 10.4 | 0.0 | |

| CPG % | |||

| Low disability | |||

| Low pain intensity | 1.6 | 3.7 | |

| High pain intensity | 3.3 | 0.0 | |

| High disability | |||

| Moderately limiting | 18.0 | 3.7 | |

| Severely limiting | 77.0 | 92.6 | |

| WHO stage of analgesics[b] % |

|

||

| Stage 2 | 58.4 | 8.9 | |

| Stage 3 | 41.6 | 91.1 | |

| Satisfaction with analgesic (1-6[a]) | 3.26 (1.35) | 3.32 (1.39) | |

| Opioid dose[c] (mg) | 47.05 (25.16) | 189.90 (67.78) | F 1,163 =388.26, P=.00 |

| Neuropathic pain score (0-35[a]) | 14.23 (7.31) | 15.68 (7.60) | |

| Psychological characteristics | |||

| HADS - depression (0-21[a]) | 9.60 (4.09) | 11.12 (4.57) | F 1,153 =3.90, P=.05 |

| HADS - anxiety (0-21[a]) | 8.85 (3.95) | 9.66 (4.43) | |

| mPDI - disability (0-50[a]) | 35.44 (7.47) | 36.70 (7.97) | |

| MQHH - habitual wellbeing (0-6[a]) | 1.38 (1.00) | 1.37 (1.07) | |

| WHOQOL-BREF (0-100[a]) | |||

| Physical | 38.56 (14.08) | 35.45 (16.54) | |

| Psychological | 55.22 (18.38) | 52.50 (20.23) | |

| Social relationships | 62.54 (19.89) | 60.99 (21.25) | |

| Environmentally related | 64.45 (14.71) | 62.90 (15.24) | |

| Global score | 37.60 (17.57) | 33.33 (17.17) | |

-

CPG = Chronic Pain Grade Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; mPDI = modified Pain Disability Index; MQHH = The Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health; NOA = nonopioid analgesics; OA=opioid analgesics; WHO=World Health Organisation; WHOQoL-Bref=World Health Organisation Quality of Life - Short Version

Mean depression scores for group with opioid dose <120 mg and >120 mg.Error bars represent standard error.

3.3 Complementary analysis

The majority of patients in the OA group (N = 137; 81%) were under opioid medication for more than 6 months. To exclude bias effects of shorter intake times on our results, analyses were repeated with the subgroup of patients with an opioid intake time ≥6 months. All significant group differences could be replicated under these conditions for comparison of OA and NOA patients as well as for the comparison of patients with opioid doses <120 mg (N = 100; 73%) versus >120 mg (N = 37; 27%). Only the marginally significant difference between the OA and NOA group with regard to psychological QoL disappeared. Detailed statistics are provided as appendix material (Tables A1 and A2).

3.4 Differences between low and high potency opioids

In order to analyze differential outcomes of high and low potency opioids on pain, QoL, functioning, and psychological wellbeing, additional ANOVA’s with opioid potency (low versus high) as between subject factor were carried out. Patients in both groups were comparable with regard to age and sex. There was no effect of opioid potency on peak and average pain intensity, respectively.

Slightly higher scores of neuropathic like pain were reported by patients with high opioid potency (mean (M) = 15.63; standard deviation (SD) = 8.23) in comparison to lower opioid potency (M = 13.45; SD = 6.12, F1,149 = 3.29, P = .07). Further, longer duration of opioid intake time in months (low opioid potency: M = 30.51; SD = 35.2; high opioid potency: M = 43.89; SD = 39.57; F1,158 =4.95, P = .03) and higher opioid doses (low opioid potency: M = 42.45; SD = 26.30; high opioid potency: M =113.53; SD = 82.77; SD = 26.3; F1,163 = 50.94, P = .000) were found in patients receiving high potency or stage 3 opioids.

With regard to psychological wellbeing and QoL, patients with high potency opioids showed greater impairment than patients with low potency opioids as indicated by higher depression scores (low opioid potency: M = 9.21; SD = 4.21; high opioid potency: M = 10.73; SD = 4.2; F1,153 = 5.04, P = .03); lower habitual wellbeing (low opioid potency: M = 1.62; SD = 1.08; high opioid potency: M = 1.15; SD = 1.02; F1,143 =7.12; P=.01) and lower psychological QoL (low opioid potency: M = 58.24; SD = 20.48; high opioid potency: M = 51.32; SD = 16.74; F1,158 = 5.49; P = .02). Apart from these findings, trends to higher anxiety scores (low opioid potency: M = 8.54; SD = 4.02; high opioid potency: M = 9.62; SD = 4.09; F1,153 = 3.17; P =.08) and greater disability ratings (low opioid potency: M = 8.54; SD = 4.02; high opioid potency: M = 9.62; SD = 4.09; F1,148 = 2.99, P=.09) with high potency opioids were revealed.

3.5 Relationships between variables

Correlation analysis in the combined group of patients with chronic pain (Table 4) revealed significantly positive associations of pain intensity (average and peak score) with subjectively experienced disability, neuropathic pain score, depression, and anxiety. Additionally, higher peak intensities of pain correlated significantly negative with three domains of QoL, namely physical, psychological and global QoL. With regard to average pain intensity only the negative relationship with physical QoL reached significance. Furthermore, a negative association could be revealed for age and peak pain intensity (r277 = –.16, P =.007) as well as for age and neuropathic pain score (r292 = –.27, P = .00).

Significant correlation coefficients within the group of chronic pain patients and patients with long-term opioid treatment (given in the last two rows and columns).

| Variable | Pain average | Pain maximum | Subscales of WHO-QoL-BREF | Neuropathic | Months OA[a] | Opioid dose[a],[b] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Physical | Psychological | Social | Environment | Global | |||||||

| Pain intensity | r | .55[**] | –.17[**] | –.11[#] | –.11[#] | ||||||

| average (0-10[c]) | N | 267 | 254 | 255 | 241 | ||||||

| Pain intensity | r | .55[**] | –.23[**] | –.16[**] | –.18[**] | ||||||

| maximum (0-10[c]) | N | 267 | 259 | 261 | 264 | ||||||

| Duration of pain | r | –.13[*] | –.12[*] | –.14[*] | .36[**] | .14[#] | |||||

| (months) | N | 312 | 293 | 311 | 155 | 159 | |||||

| Satisfaction with | r | –.10[#] | –.11[#] | ||||||||

| analgesic (1-6[c]) | N | 284 | 286 | ||||||||

| Neuropathic like | r | .30[**] | .32[**] | –.29[**] | –.24[**] | –.11[#] | –.19[**] | –.19[**] | |||

| pain (0-35[c]) | N | 256 | 261 | 274 | 276 | 260 | 275 | 281 | |||

| HADS - anxiety | r | .13[**] | .19[**] | –.26[**] | –.53[**] | –.25[**] | –.32[**] | –.31[**] | .29[**] | .14[#] | |

| (0-21[c]) | N | 267 | 272 | 287 | 289 | 272 | 288 | 293 | 290 | 145 | |

| HADS - depression | r | .20[**] | .19[**] | –.39[**] | –.62[**] | –.35[**] | –.37[**] | –.36[**] | .23[**] | .16[*] | |

| (0-21[c]) | N | 267 | 272 | 287 | 289 | 272 | 288 | 293 | 290 | 148 | |

| mPDI | r | .44[**] | .35[**] | –.42[**] | –.21[**] | –.15[*] | –.25[**] | –.32[**] | .31[**] | .15[#] | |

| (0-50[c]) | N | 253 | 259 | 273 | 275 | 261 | 275 | 279 | 273 | 143 | |

| MQHH | r | .29[**] | .29[**] | .24[**] | .27[**] | –.12[*] | |||||

| (0-6[c]) | N | 274 | 273 | 272 | 277 | 278 | |||||

| Months of intake OA[a] | r | –.15[#] | |||||||||

| N | 150 | ||||||||||

| Opioid dose[a],[b] | r | –.14[#] | |||||||||

| N | 153 | ||||||||||

-

HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; mPDI = modified Pain Disability Index; MQHH = The Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health; NOA = nonopioid analgesics; OA = opioid analgesics; WHOQoL-BREF=World Health Organisation Quality of Life - Short Version

Correlational analysis within the OA group (Table 4) revealed a significantly positive relationship between duration of pain with duration of opioid intake. Further, opioid dose yielded a significantly positive association with depression scores.

The psychological variables depression, anxiety, habitual wellbeing, and experienced disability were consistently related to QoL of the chronic pain patients. The relationships were in the expected direction, i.e. scores indicating greater disturbance were related to lower QoL scores. Other observed relationships included neuropathic like pain intensity which was significantly and negatively associated with QoL, i.e. higher neuropathic pain scores were related to lower physical, psychological, environmental, and global QoL. Additional information for marginally significant coefficients are displayed in Table 4.

Tests for significant differences between the correlation coefficients within the combined group of chronic pain patients versus the OA treatment group were positive in the case of the correlation of depression with global QoL. Thereby, a closer relationship was indicated within the OA group (r150 = –.50, P< .000) in contrast to the combined group of chronic pain patients.

4 Discussion

The present study is the first to evaluate intermediate and long-term benefits of opioids for chronic pain in comparison to nonopioid treatment strategies [10,34]. The results from this observational study reflect daily routine clinical care of CNCP patients. In addition, a comprehensive assessment of the long-term outcome of treatment was carried out to determine not just pain status but also QoL, daily functioning and psychological wellbeing.

Patients treated with opioid analgesics showed a higher burden in terms of pain chronicity as indicated by pain duration, longer history of analgesic intake, and higher scores on a neuropathic pain scale in comparison to patients who received nonopioid analgesics. These results point to prescription of opioids in accordance with current guidelines for opioid therapy in CNCP [33, [35,36], e.g. suggesting opioids in case of neuropathic pain. Further, use of opioid analgesics is advised when other strategies (e.g. nonopioid medications or physical therapy) fail to provide sufficient pain control, indicated in our sample by a long history of analgesic intake.

Assuming satisfaction ratings as reflection of drug efficacy, the patients of our sample seem to receive some pain relief. However, other factors are also likely to affect satisfaction with analgesics, e.g. incidence and intensity of adverse effects or positive reinforcing drug effects, and need to be considered. In line with this, there were relatively high pain scores for patients receiving opioid or non-opioid analgesics and there was a high degree of limitations in 80% of patients as indicated by CPG level despite use of medication. These observations raise questions about the long-term effectiveness of analgesic treatment regimens irrespective of analgesics type employed. More frequent reviews of the effectiveness of analgesic therapy in CNCP and appropriate treatment changes are advised, particularly as the patients have received analgesics for approximately 3 years. In keeping with earlier reports, QoL scores in our study population were markedly reduced and associated with pain characteristics, namely pain intensity and pain duration [6, [37,38]. Only for the dimension of physical QoL were lower scores evident in the OA group, but no differences between the OA and NOA treatment groups could be revealed with regard to other aspects of QoL. Recently, Mellbye et al. [39] suggested to explain poor QoL in terms of higher burden due to psychiatric and somatic comorbidities. In their study increased occurrence for as many as 18 somatic and 3 psychiatric disorders in CNCP patients with persistent opioid use were found in comparison on to an age- and gender-specific sample from the general population. Additionally, in our study side effects were more frequently reported by patients receiving opioids. Typical side effects are not only expected to manifest as constipation but also as persistent fatigue throughout prolonged therapy and not only in the treatment adjustment phase resulting in poorer physical QoL [40]. Although fatigue is well known in chronic pain conditions, explanation of higher fatigue due to opioids seems reasonable considering the likewise long pain duration in our NOA group.

It is also relevant to note in our chronic pain patients that ratings of functional disability and habitual wellbeing showed marked impairment. Significant differences were shown in favour of those patients taking nonopioid analgesics compared to those under opioid analgesics. However, these statistical significances are of minor clinical relevance especially considering the high level of disability and impairment of both groups. There may be a selection effect in the present study with more patients presenting with severe chronic pain that attend our specialised pain unit. Irrespective of this finding, it is alarming that 10% of patients with primary psychological somatoform pain disorder were treated with opioid analgesics. Similarly, Hauser et al. [41] stated an over treatment of patients with somatoform pain disorder with opioids (38%) based on an analysis of German health insurance data, despite recommended avoidance of opioids in these patients (e.g. [33]).

In line with recent research results [11, 42, 43,44], use of opioid analgesics at high doses was associated with male gender and mental health problems. Additionally, higher dosing was more often in patients on high potency opioids (WHO stage 3) and there was a trend to increasing doses with longer duration of pain. Higher doses with high potency opioids are not necessarily to be expected, as potency is taken into account by recommended dosing strategies. In line with this, the dosing of high potency opioids varied between 7 and 360 mg morphine equivalents in our sample.

We did not find an association between dosage and grade of satisfaction with medication. Assuming positive reinforcing effects of opioids as one factor with influence on dosage and satisfaction, this could have hinted at a problematic opioid use. Rather, the present findings seem to indicate, that dose titration does not necessarily goes along with greater satisfaction. Further, with regard to dosing strategies, our results do not support additional therapeutic benefits by prescribing higher doses of opioids. Improvement of pain, QoL or other indicators of psychological wellbeing and functioning were not achieved by increasing the opioid dose.

Meanwhile, depression seems to be associated with increasing opioid doses, as indicated by a significant positive correlation. The direction of this association is under discussion, with some evidence supporting mental health problems as an antecedent condition (e.g. [45,46]). This observation led Sullivan and Howe [2] to assume an adverse selection effect where patients with mental disorders are more likely to be prescribed high-risk opioid regimens. On the other hand, mental health problems were found to increase as a consequence of opioid intake. Using a retrospective cohort design, Scherreret al. [15] revealed an increasing risk of developing depression along with increasing duration of opioid prescription. Furthermore, the association between mental health problems and opioid intake was found to be explained by moderator variables. For example, in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, overuse of opioids was predicted by catastrophizing but not by depression [47]. In this regard, the association between psychopathological variables and neuropathic pain components are also of interest. Both were found to be interrelated in our study and additionally associated with opioid dose. Neuropathic like pain experience may be reinforced by increasing depression and anxiety with the consequence of a subjective need for higher opioid doses. Another possible pathway could be a higher degree of psychological strain caused by neuropathic like pain which is subjectively perceived as difficult to control. In both cases, rises in prescription dose are thus driven by intense suffering of the patient even though different treatment strategies would be appropriate depending on the assumed pathway. Apart from this, empirical evidence also points to a possible opioid-induced hyperalgesia [16, [48,49]. Increasing pain and the development of additional pain symptoms are a consequence of higher opioid doses and increased duration of opioid administration [17]. However, data of our study does not permit any conclusion about the direction of these associations and further prospective studies are needed to investigate various pathways and the role of mediators.

4.1 Limitations and strengths

The present study comes with some limitations, which are partly inherent to the design. First, in observational studies any interventions are determined by clinical practice and not by study protocol, thereby leaving uncertainty about alternative explanations for the study results. By means of ANCOVA some control can be exerted. Therefore, beside age, further ANCOVA’s were carried out with potentially relevant variables, e.g. neuropathic like pain or pain duration. As group differences remained almost invariant (i.e. no add or loss of significance) data report in the present paper was based on ANCOVA with age. Second, due to the cross-sectional design of our study temporal relationships between treatment and outcome are difficult to determine. Prevalence of outcome but not the association between exposure and developing an outcome are measured. In our study baseline data, e.g. with regard to pain intensity are not available and limits definitive conclusions based on the observations and the apparent effectiveness of the analgesic regimens on pain intensity, QoL, functioning or psychological wellbeing. However, observational studies give us the advantage to observe how treatment work under natural conditions, whereas in RCT’s many factors which are reflecting the actual situation of chronic pain patients are thought to confound the results and serve as exclusion criteria. A third critical issue refers to the use of multiple significance tests and the associated risk of elevated Type I error. However, Bonferroni-correction was not applied considering the stated problems of being overly conservative and inflating Type II error [50,51]. Finally, interpretation of our satisfaction rating needs to be cautious. We analyzed satisfaction rating with regard to the leading medication. However most of our patients used more than one analgesic or co-analgesic. Therefore, attribution of effect to a single medication could be challenging. Skipping patients with more than one analgesic would have resulted in a significant decrease of sample size and thwart our efforts to give a reflection of clinical routine care. Further, patients seemed to distinguish quite well between effects of their medications during the interview, probably as they usually received the prescriptions successive. However, a composite effect on the rating cannot be ruled out.

A major strength of the study is that it expands on previous findings by providing data on the outcome of long-term opioid therapy for over 6 months as well as in comparison to nonopioid therapy. By excluding patients with opioid intake for 3-6 months, it was possible to replicate the main pattern of significant clinical findings of the study within a subgroup analysis. Further, the concept of pain as a multi-dimensional phenomenon found consideration by the utilised measures. Additionally, the large sample size and a near equivalent number of subjects in our study groups allow quite precise estimates. Nevertheless, interpretation of our results needs to be cautious due to the contextual nature and observational design of the study. Cause-effect-statements are out of question and prospective as well as randomised controlled studies are desirable to further advance our knowledge in the field of long-term analgesic treatment.

5 Conclusions

Chronic pain itself constitutes a disease. It accompanies the patient for months or years and is often incurable. From a clinical perspective, despite long-term treatment the intensity of pain, level of impairment and poor QoL experienced by our patients evidence the inadequacy of opioids and nonopioids for the management of this condition. Nevertheless, while pain killers do not ‘kill’ chronic pain, they remain an important therapeutic option and are widely used for the treatment of pain. In the low to medium opioid dose range, the benefit to risk relationship is rather reasonable and their use seems to be justifiable [12, [18,19]. However, increasing the opioid dose to meet the patient requirements does not deliver benefits which meet his expectations. This strategy is not useful as a sole therapeutic approach and bears the risk of serious adverse events [34]. In particular, neuropathic like pain is a critical consideration whether high dose opioids are an appropriate treatment strategy in patients with chronic pain.

To try and to prevent pain becoming chronic, intervention which empowers patients to engage in active coping strategies should start from the very beginning. Treatment should be comprised of psychological elements and psychoeducation about bio-psycho-social aspects of pain. Adopting these measures might weaken the multiple consequences of chronic pain. Actually, before patients visit a special pain unit, they have usually undergone months or years of medication which primarily follows a biomedical model of pain. This is especially true of the population investigated in this study. Ideally, long-term treatment requires a meaningful therapy plan and a combination of different treatment modules with activating physical therapy and psychological pain management as essential ingredients.

6 Implications

Our results raise questions about the long-term effectiveness of analgesic treatment regimens irrespective of analgesics type employed and call for more multidisciplinary treatment strategies.

Highlights

Outcome data of long-term opioid therapy versus nonopioid treatment are provided.

No clear advantage of opioid vs. non-opioid analgesics could be revealed.

Treatment with pain medication proved insufficient.

Worse benefit to risk relationship with higher doses and potency of opioids.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.09.004.

-

Ethical issues: The study was approved by the institutional ethic committee of the University of Wuppertal.

-

Conflicts of interest: T.C. has received financial support and provided consultant services for the following: Astellas, Grünenthal, Pharmallergan. K.E. has no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding: This research was supported by funds from Mundipharma GmbH. The funders were not involved in the design and conduction of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Merle Claßen, Jana Garloff, Andrea Krüger, Madeleine Müller, Malte Nuyken and Ruth Schmitz for their help with the data collection and/or statistical analysis.

Appendix A

Mean (SD) of sociodemographic, clinical and psychological characteristics of the patients on nonopioids and patients with persistent opioid intake over at least 6 months.

| Variables | Nonopioid group N = 163 | Opioid group N = 137 | Significant results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.74 (15.34) | 65.82 (12.92) | F 1,299 = 3.54, P = .06 |

| Sex (female) % | 76.2 | 73 | |

| Marital status: married % | 48.1 | 53 | |

| Employment % | |||

| Full or part time | 25.8 | 15.2 |

|

| Unemployed | 6.9 | 3.8 | |

| Retired/disability | 53.5 | 68.9 | |

| Others | 13.8 | 12.1 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Duration of pain (month) | 94.14 (103.76) | 160.25 (138.08) | F 1,295 = 22.04, P=.000 |

| Pain intensity (0-10[a]) | |||

| Average | 6.86 (1.82) | 7.17 (1.76) | |

| Peak | 8.75 (1.24) | 8.66 (1.62) | |

| Months of analgesic intake | |||

| Overall | 62.45 (75.39) | 113.41 (110.31) | F 1,277 = 20.56, P=.000 |

| Continuously NOA since | 35.53 (63.01) | 32.57 (46.01) | |

| Continuously OA since | - | 43.22 (38.62) | |

| ICD-diagnosis group % | |||

| M. musculoskeletal | 76.8 | 79.6 | |

| G. nervous system | 5.5 | 3.6 | |

| F. mental/behavioural | 8.5 | 10.9 | |

| Others | 9.1 | 5.8 | |

| CPG % | |||

| Low disability | |||

| Low pain intensity | 2.3 | 3 | |

| High pain intensity | 5.8 | 1.5 | |

| High disability | |||

| Moderately limiting | 14.0 | 14.9 | |

| Severely limiting | 77.9 | 80.6 | |

| WHO stage of analgesics[b] % | |||

| None | 25.8 | 0.0 |

|

| Stage 1 | 74.2 | 0.0 | |

| Stufe 2 | 0.0 | 39.4 | |

| Stufe 3 | 0.0 | 60.6 | |

| Satisfaction with analgesic (1-6[a]) | 3.43 (1.28) | 3.27 (1.40) | |

| Opioid dose[c] (mg) | - | 84.96 (75.98) | |

| Neuropathic pain score (0-35[a]) | 12.57 (6.94) | 14.48 (7.36) | F 1,259 = 4.60, P = .03 |

| Psychological characteristics | |||

| HADS - depression (0-21[a]) | 9.07 (4.39) | 9.97 (4.27) | F 1,272 = 2.83, P=.08 |

| HADS - anxiety (0-21[a]) | 8.60 (4.39) | 8.97 (4.13) | |

| mPDI - functional disability (0-50[a]) | 33.45 (8.20) | 35.81 (7.54) | F 1,259 = 5.74, P=.02 |

| MQHH - habitual wellbeing (0-6[a]) | 1.68 (1.26) | 1.40 (1.07) | F 1,285 = 3.18, P=.07 |

| WHOQOL-BREF (0-100[a]): Physical | 41.59 (14.00) | 37.65 (15.14) | F 1,281 =4.97, P=.03 |

| Psychological | 57.53 (17.42) | 55.06 (19.03) | |

| Social relationships | 62.36 (19.98) | 62.36 (20.19) | |

| Environmentally related | 65.92 (13.57) | 64.39 (14.88) | |

| Global score | 37.90 (16.77) | 37.22 (17.77) | |

-

CPG = Chronic Pain Grade Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; mPDI = modified Pain Disability Index; MQHH = The Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health; NOA = nonopioid analgesics; OA=opioid analgesics; WHO=World Health Organisation; WHOQoL-Bref=World Health Organisation Quality of Life - Short Version

Mean (SD) of sociodemographic, clinical and psychological characteristics of chronic pain patients with persistent opioid intake over at least 6 month and with morphine dose <120 mg versus >120 mg.

| Variables | Opioid < 120 mg N = 100 | Opioid >120mg N = 37 | Significant results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.02 (12.97) | 65.30 (12.94) | |

| Sex (female) % | 78 | 59.5 |

|

| Marital status: married % | 46 | 73.5 |

|

| Employment % | |||

| Full or part time | 16.3 | 11.8 | |

| Unemployed | 3.1 | 5.9 | |

| Retired/disability | 70.4 | 64.7 | |

| Others | 10.2 | 17.6 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Duration of pain (month) | 147.54 (120.31) | 195.56 (175.66) | F 1,135=3.25, P=.07 |

| Pain intensity (0-10[a]) | |||

| Average | 7.14 (1.79) | 7.26 (1.73) | |

| Peak | 8.64 (1.42) | 8.71 (2.05) | |

| Months of analgesic intake | |||

| Overall | 107.65 (106.3) | 129.71 (121.14) | |

| Continuously NOA since | 32.64 (41.81) | 32.38 (57.04) | |

| Continuously OA since | 40.72 (38.11) | 50.17 (39.71) | |

| ICD-diagnosis group % | |||

| M. musculoskeletal | 76.0 | 89.2 | |

| G. nervous system | 4.0 | 2.7 | |

| F. mental/behavioural | 12.0 | 8.1 | |

| Others | 8.0 | 0.0 | |

| CPG % | |||

| Low disability | |||

| Low pain intensity | 2.2 | 4.8 | |

| High pain intensity | 2.2 | 0.0 | |

| High disability | |||

| Moderately limiting | 21.7 | 0.0 | |

| Severely limiting | 73.9 | 95.2 | |

| WHO stage of analgesics[b] % | |||

| Stufe 2 + Kombis | 52.0 | 5.4 |

|

| Stufe3 + Kombis | 48.0 | 94.6 | |

| Satisfaction with analgesic (1-6[a]) | 3.26 (1.38) | 3.30 (1.46) | |

| Opioid dose[c] (mg) | 48.09 (25.73) | 193.38 (71.07) | F 1,133=304.49, P=.000 |

| Neuropathic pain score (0-35[a]) | 14.23 (7.36) | 15.12 (7.45) | |

| Psychological characteristics | |||

| HADS-depression (0-21[a]) | 9.47 (4.11) | 11.33 (4.44) | F 1,122 = 4.77, P=.03 |

| HADS-anxiety (0-21[a]) | 8.78 (3.87) | 9.48 (4.79) | |

| mPDI - disability (0-50[a]) | 35.5 (7.46) | 36.66 (7.82) | |

| MQHH - habitual wellbeing (0-6[a]) | 1.35 (0.96) | 1.52 (1.32) | |

| WHOQOL-BREF (0-100[a]) | |||

| Physical | 38.38 (14.24) | 35.39 (17.73) | |

| Psychological | 56.09 (18.45) | 52.10 (20.69) | |

| Social relationships | 63.30 (20.23) | 59.34 (20.09) | |

| Environmentally related | 64.62 (15.03) | 63.68 (14.61) | |

| Global score | 38.50 (17.92) | 33.46 (17.06) | |

-

CPG = Chronic Pain Grade Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; mPDI = modified Pain Disability Index; MQHH = The Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health; NOA = nonopioid analgesics; OA=opioid analgesics; WHO=World Health Organisation; WHOQoL-Bref=World Health Organisation Quality of Life - Short Version

References

[1] Schubert I, Ihle P, Sabatowski R. Increase in opiate prescription in Germany between 2000 and 2010: a study based on insurance data. Dtsch Ärztebl Int 2013;110:45–51.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Sullivan MD, Howe CQ. Opioid therapy for chronic pain in the United States: promises and perils. Pain 2013;154 (Suppl.1):S94–100.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Furlan AD, Sandoval JA, Mailis-Gagnon A, Tunks E. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effects. CMAJ 2006;174:1589–94.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Bailey RW, Vowles KE. Chronic noncancer pain and opioids: risks, benefits, and the public health debate. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2015;46:340–7.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Maier C, Schaub C, Willweber-Strumpf A, Zenz M. [Long-term efficiency of opioid medication in patients with chronic non-cancer associated pain. Results of a 5 years survey after onset of medical treatment].Schmerz 2005;19:410–7.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Jensen MK, Thomsen AB, H0jsted J. 10-year follow-up of chronic non-malignant pain patients: opioid use, health related quality of life and health care utilization. Eur J Pain 2006;10:423–33.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Welsch P, Sommer C, Schiltenwolf M, Hauser W. Opioids in chronic noncancer pain-are opioids superior to nonopioid analgesics? A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, tolerability and safety in randomized head-to-head comparisons of opioids versus nonopioid analgesics of at least four week’s duration. Schmerz 2015;29:85–95.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kissin I. Long-term opioid treatment of chronic nonmalignant pain: unproven efficacy and neglected safety? J Pain Res 2013;6:513–29.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Breivik H, Ljosaa TM, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Persson J, Aro H, Villumsen J, Tvinnemose D. A 6-months, randomised, placebo-controlled evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of a low-dose 7-day buprenorphine transdermal patch in osteoarthritis patients naive to potent opioids. Scand J Pain 2010;1: 122-41.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Deyo RA. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Int Med 2015;162:276–86.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Sullivan MD, Weisner CM, Silverberg MJ, Campbell CI, Psaty BM, Korff M von. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:85–92.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Carman WJ, Su S, Cook SF, Wurzelmann JI, McAfee A. Coronary heart disease outcomes among chroni opioid and cyclooxygenase-2 users compared with a general population cohort. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:754–62.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Li L, Setoguchi S, Cabral H, Jick S. Opioid use for noncancer pain and risk of fracture in adults: a nested case-control study using the general practice research database. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:559–69.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Rolita L, Spegman A, Tang X, Cronstein BN. Greater number of narcotic analgesic prescriptions for osteoarthritis is associated with falls and fractures in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:335–40.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Scherrer JF, Svrakic DM, Freedland KE, Chrusciel T, Balasubramanian S, Bucholz KK, Lawler EV, Lustman PJ. Prescription opioid analgesics increase the risk of depression. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:491–9.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ballantyne J, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1943–53.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Lee M, Silverman S, Hansen H, Patel V, Manchikanti L. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician 2011;14:145–61.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Saunders KW, Dunn KM, Merrill JO, Sullivan M, Weisner C, Braden JB, Psaty BM, Korff M von. Relationship of opioid use and dosage levels to fractures in older chronic pain patients. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:310–5.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Dillie KS, Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT. Quality of life associated with daily opioid therapy in a primary care chronic pain sample. J Am Board Fam Med 2008;21:108–17.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Richardson JL, Marks G, Johnson CA, Graham JW, Chan KK, Selser JN, Kishbaugh C, Barranday Y, Levine AM. Path model of multidimensional compliance with cancer therapy. Health Psychol 1987;6:183–207.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaf eV, editor. [German Pain Questionnaire]. Integrative Managed Care GmbH; 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[22] World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Diseases, Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva WHO; 1992.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Schmerzklinik Universitàtsmedizin Gòttingen. [Table of opioid-conversion factors]. Available from http://www.ains.med.uni-goettingen.de/sites/default/files/Opioid-Umrechnungstabelle[accessed: 07.06.17].Search in Google Scholar

[24] Arzneimittelbrief. [Pain therapy with opioids]. AMB 2011; 45 (65).Search in Google Scholar

[25] Tait RC, Pollard CA, Margolis RB, Duckro PN, Krause SJ. The Pain Disability Index: psychometric and validity data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1987;68:438–41.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Korff M von, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain 1992;50:133–49.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tòlle TR. pain DETECT: anew screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1911–20.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Angermeyer MC, Kilian R, Matschinger H. [WHOQOL - 100 und WHOQOL - Bref.Manual for the German Version of WHO instruments for assessment of quality of life]. Gòttingen: Hogrefe Verlag; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. [SF-36.Short Form Health Survey.Manual]. Gòttingen: Hogrefe Verlag; 1998.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Herda C, Scharfenstein A, Basler HD. [The Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health]. In: Schriftenreihe des Zentrums für Methodenwissenschaften und Gesundheitsforschung. Arbeitspapier 98-1.1998.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Petermann F. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Deutsche Version (HADS-D). Z Psychiat Psychol Psychother 2011;59:251–3.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Hauser W, Bock F, Engeser P, Hege-Scheuing G, Huppe M, Lindena G, Maier C, Norda H, Radbruch L, Sabatowski R, Schafer M, Schiltenwolf M, Schuler M, Sorgatz H, Tòlle T, Willweber-Strumpf A, Petzke F. Recommendations of the updated LONTS guidelines. Long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain.Schmerz 2015;29:109–30.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. JAMA 2016;315:1624–45.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Adler JA, Ballantyne JC, Davies P, Donovan MI, Fishbain DA, Foley KM, Fudin J, Gilson AM, Kelter A, Mauskop A, onnor PG, Passik SD, Pasternak GW, Portenoy RK, Rich B. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer patients. J Pain 2009;10: 113-30.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Cheung CW, Qiu Q, Choi S, Moore B, Goucke R, Irwin M. Chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain: a review and comparison of treatment guidelines. Pain Physician 2014;17:401–14.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Fredheim OMS, Kaasa S, Fayers P, Saltnes T, Jordhoy M, Borchgrevink PC. Chronic non-malignant pain patients report as poor health-related quality of life as palliative cancer patients. Act Anaesth Scand 2008;52:143–8.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Bjornsdottir SV, Jonsson SH, Valdimarsdottir UA. Mental health indicators and quality of life among individuals with musculoskeletal chronic pain: a nationwide study in Iceland. Scand J Rheumatol 2014;43:419–23.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Mellbye A, Karlstad O, Skurtveit S, Borchgrevink PC, Fredheim OMS. Comorbidity in persistent opioid users with chronic non-malignant pain in Norway. EurJ Pain 2014;18:1083–93.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Christensen HN, Olsson U, From J, Breivik H. Opioid-induced constipation, use of laxatives, and health-related quality of life. Scand J Pain 2016;11: 104-10.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Hauser W, Marschall U, L’hoest H, Komossa K, Henningsen P. Administrative prevalence, treatment and costs of somatoform pain disorder. Analysis of data of the BARMER GEK for the years 2008-2010.Schmerz 2013;27:380–6.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Kobus AM, Smith DH, Morasco BJ, Johnson ES, Yang X, Petrik AF, Deyo RA. Correlates of higher-dose opioid medication use for low back pain in primary care. J Pain 2012;13:1131–8.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Merrill JO, Korff M von, Banta-Green CJ, Sullivan MD, Saunders KW, Campbell CI, Weisner C. Prescribed opioid difficulties, depression and opioid dose among chronic opioid therapy patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012;34:581–7.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Marschall U, L’hoest H, Radbruch L, Hauser W. Long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain in Germany. EurJ Pain 2016;20:767–76.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Braden JB, Sullivan MD, Ray GT, Saunders K, Merrill J, Silverberg MJ, Rutter CM, Weisner C, Banta-Green C, Campbell C, Korff M von. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain among persons with a history of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:564–70.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Grattan A, Sullivan MD, Saunders KW, Campbell CI, Korff MR von. Depression and prescription opioid misuse among chronic opioid therapy recipients with no history of substance abuse. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:304–11.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Martel MO, Wasan AD, Jamison RN, Edwards RR. Catastrophic thinking and increased risk for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132:335–41.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Brush DE. Complications of long-term opioi therapy fo management of chronic pain: the paradox of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. J Med Toxicol 2012;8:387–92.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Arout CA, Edens E, Petrakis IL, Sofuoglu M. Targeting opioid-induced hyperalgesia in clinical treatment: neurobiological considerations. CNS Drugs 2015;29:465–86.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ 1998;316:1236–8.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Nakagawa S. A farewell to Bonferroni: the problems of low statistical power and publication bias. Behav Ecol 2004;15:1044–5.Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research

- Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome

- Observational study

- Long-term treatment in chronic noncancer pain: Results of an observational study comparing opioid and nonopioid therapy

- Clinical pain research

- COMBAT study – Computer based assessment and treatment – A clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients

- Original experimental

- Quantitative sensory tests fairly reflect immediate effects of oxycodone in chronic low-back pain

- Editorial comment

- Spatial summation of pain and its meaning to patients

- Original experimental

- Effects of validating communication on recall during a pain-task in healthy participants

- Original experimental

- Comparison of spatial summation properties at different body sites

- Editorial comment

- Behavioural inhibition in the context of pain: Measurement and conceptual issues

- Clinical pain research

- A randomized study to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of the TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis

- Editorial comment

- Quantitative sensory tests (QST) are promising tests for clinical relevance of anti–nociceptive effects of new analgesic treatments

- Educational case report

- Pregabalin as adjunct in a multimodal pain therapy after traumatic foot amputation — A case report of a 4-year-old girl

- Editorial comment

- Severe side effects from intrathecal morphine for chronic pain after repeated failed spinal operations

- Editorial comment

- Opioids in chronic pain – Primum non nocere

- Editorial comment

- Finally a promising analgesic signal in a long-awaited new class of drugs: TRPV1 antagonist mavatrep in patients with osteoarthritis (OA)

- Observational study

- The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain

- Clinical pain research

- Opioid tapering in patients with prescription opioid use disorder: A retrospective study

- Editorial comment

- Sleep, widespread pain and restless legs — What is the connection?

- Editorial comment

- Broadening the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain?

- Observational study

- Identifying characteristics of the most severely impaired chronic pain patients treated at a specialized inpatient pain clinic

- Editorial comment

- The burden of central anticholinergic drugs increases pain and cognitive dysfunction. More knowledge about drug-interactions needed

- Editorial comment

- A case-history illustrates importance of knowledge of drug-interactions when pain-patients are prescribed non-pain drugs for co-morbidities

- Editorial comment

- Why can multimodal, multidisciplinary pain clinics not help all chronic pain patients?

- Topical review

- Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics – Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics

- Editorial comment

- A new treatable chronic pain diagnosis? Flank pain caused by entrapment of posterior cutaneous branch of intercostal nerves, lateral ACNES coined LACNES

- Clinical pain research

- PhKv a toxin isolated from the spider venom induces antinociception by inhibition of cholinesterase activating cholinergic system

- Clinical pain research

- Lateral Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (LACNES): A previously unrecognized cause of intractable flank pain

- Editorial comment

- Towards a structured examination of contextual flexibility in persistent pain

- Clinical pain research

- Context sensitive regulation of pain and emotion: Development and initial validation of a scale for context insensitive avoidance

- Editorial comment

- Is the search for a “pain personality” of added value to the Fear-Avoidance-Model (FAM) of chronic pain?

- Editorial comment

- Importance for patients of feeling accepted and understood by physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation

- Editorial comment

- A glimpse into a neglected population – Emerging adults

- Observational study

- Assessment and treatment at a pain clinic: A one-year follow-up of patients with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study: Investigation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperalgesic activity of L-4-chlorokynurenine in healthy volunteers

- Clinical pain research

- Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain: Experience of Niger

- Observational study

- The use of rapid onset fentanyl in children and young people for breakthrough cancer pain

- Original experimental

- Acid-induced experimental muscle pain and hyperalgesia with single and repeated infusion in human forearm

- Original experimental

- Swearing as a response to pain: A cross-cultural comparison of British and Japanese participants

- Clinical pain research

- The cognitive impact of chronic low back pain: Positive effect of multidisciplinary pain therapy

- Clinical pain research

- Central sensitization associated with low fetal hemoglobin levels in adults with sickle cell anemia

- Topical review

- Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain

- Original experimental

- What constitutes back pain flare? A cross sectional survey of individuals with low back pain

- Original experimental

- Coping with pain in intimate situations: Applying the avoidance-endurance model to women with vulvovaginal pain

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain?

- Original experimental

- The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury

- Educational case report

- Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series

- Original experimental

- Hyperbaric oxygenation alleviates chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced neuropathic pain and inhibits GABAergic neuron apoptosis in the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children

- Clinical pain research

- Hospitalization due to acute exacerbation of chronic pain: An intervention study in a university hospital

- Clinical pain research

- A novel miniature, wireless neurostimulator in the management of chronic craniofacial pain: Preliminary results from a prospective pilot study

- Clinical pain research

- Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending

- Original experimental

- Unpredictable pain timings lead to greater pain when people are highly intolerant of uncertainty

- Original experimental

- Initial validation of the exercise chronic pain acceptance questionnaire

- Clinical pain research

- Exploring patient experiences of a pain management centre: A qualitative study

- Clinical pain research

- Narratives of life with long-term low back pain: A follow up interview study

- Observational study

- Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption

- Clinical pain research

- Chronic pain disrupts ability to work by interfering with social function: A cross-sectional study

- Original experimental

- Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: A single center open label pilot study

- Observational study

- Impact of analgesics on executive function and memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Database

- Clinical pain research

- Visualization of painful inflammation in patients with pain after traumatic ankle sprain using [11C]-D-deprenyl PET/CT

- Original experimental

- Developing a model for measuring fear of pain in Norwegian samples: The Fear of Pain Questionnaire Norway

- Topical review

- Psychoneuroimmunological approach to gastrointestinal related pain

- Letter to the Editor

- Do we need an updated definition of pain?

- Narrative review

- Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?

- Book Review

- Physical Diagnosis of Pain

- Book Review

- Advances in Anesthesia

- Book Review

- Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques

- Book Review

- Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management

- Book Review

- Basics of Anesthesia

Articles in the same Issue

- Observational study

- Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females

- Clinical pain research

- Prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled trial comparing vapocoolant spray versus placebo spray in adults undergoing intravenous cannulation

- Clinical pain research

- The Functional Barometer — An analysis of a self-assessment questionnaire with ICF-coding regarding functional/activity limitations and quality of life due to pain — Differences in age gender and origin of pain

- Clinical pain research

- Clinical outcome following anterior arthrodesis in patients with presumed sacroiliac joint pain

- Observational study

- Chronic disruptive pain in emerging adults with and without chronic health conditions and the moderating role of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey in Canada

- Educational case report

- Management of patients with pain and severe side effects while on intrathecal morphine therapy: A case study

- Clinical pain research

- Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain

- Observational study

- Comparison of patients diagnosed with “complex pain” and “somatoform pain”

- Original experimental

- Patient perspectives on wait times and the impact on their life: A waiting room survey in a chronic pain clinic

- Topical review

- New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality

- Clinical pain research

- A multi-facet pain survey of psychosocial complaints among patients with long-standing non-malignant pain

- Clinical pain research