Abstract

In this paper, the research progress of zirconium (Zr) alloys is critically reviewed from the aspects of application, development status, and degradation mechanism in a nuclear environment. The review focused on the application of Zr alloys in the nuclear industry, which are widely used due to their low thermal neutron absorption, good corrosion resistance, and excellent mechanical properties. However, with the increasing requirements in the chemical and medical fields, the application of Zr alloys in these non-nuclear fields is growing due to their excellent properties like good corrosion resistance and low thermal expansion coefficient, as summarized in this review. Additionally, the degradation mechanisms of Zr alloy exposed to a corrosive environment, i.e., corrosion and hydrogen uptake, and the role of alloying selection in minimizing these two phenomena is considered in this review, based on pretransition kinetics and the loss of oxide protectiveness at transition. This is corroborated by the discussion on alloying elements with beneficial and detrimental effects on the corrosion performance of Zr alloys, as well as elements with contradicting effects on Zr alloys corrosion performance owing to the discrepancies in literature. Overall, this review can be leveraged in future alloy design to further improve Zr alloys corrosion resistance in nuclear applications, thus ultimately improving their integrity.

1 Introduction

Zirconium (Zr) element was first discovered in zirconite by M. H. Kloprothe in 1789 (Northwood 1985; Zhang et al. 2022a,b). Although it was discovered in 1789, it was not isolated until 1824 by J. J. Berzelius, who reduced potassium fluorozirconate with potassium metal to produce an impure powder (Northwood 1985). Going forward, in 1925, de Boer and Van Arkel developed the iodide process for refining Zr and produced a high purity crystal bar Zr (Northwood 1985). This was the first Zr material with good ductility. Thereafter, W. J. Kroll developed a method for mass production of ductile Zr by the reduction of ZrCl4 with magnesium metal in 1944 (Zhang et al. 2022a,b), which led to the development of Zr metal for large-scale applications. Based on the excellent properties of Zr, such as high melting point, high specific strength, good corrosion resistance, and low thermal expansion coefficient, its alloys have found numerous applications.

In this review, we discuss the major applications of Zr alloy, with special emphasis on nuclear application, and the development trend/history of nuclear grade Zr alloys from the first two alloying systems developed to the most recently developed alloys, as well as the reasons for the constant improvement. Subsequently, the degradation mechanism of Zr alloys exposed to nuclear environment was explicitly elucidated, with the aim of not only understanding the effect of the harsh nuclear environment on the applied Zr alloys but also to facilitate the development of better performing materials with the increasing in-service desired qualities. The degradation mechanism was discussed on two fronts: corrosion and hydrogen uptake. Likewise, the role of alloying selection in minimizing both degradation mechanisms is considered on the basis of two main features: the pretransition kinetics and the loss of oxide protectiveness at transition. This is corroborated by the discussion on alloying elements with beneficial and detrimental effects on the corrosion performance of nuclear grade Zr alloys, as well as the element with a contradicting effect on Zr alloys corrosion performance owing to the discrepancies between published results. Finally, areas requiring further investigations and some unresolved scientific issues were identified and highlighted in order to gain a clearer understanding of some phenomena associated with the degradation mechanism and development of better-performing nuclear grade Zr alloys.

2 Applications of Zr alloys

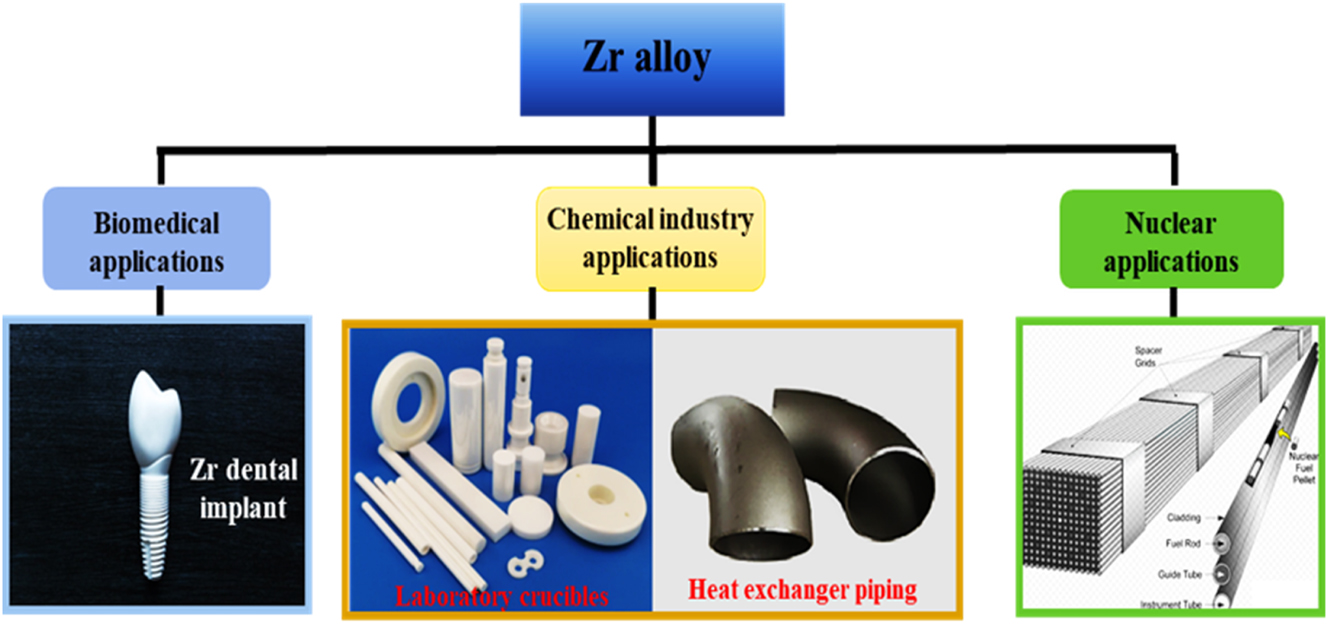

In this study, three important areas were highlighted where Zr alloys have found applicability, with special emphasis on nuclear applications, as presented in Figure 1. Further discussions on these areas are presented in subsequent subsections.

A schematic of Zr alloy and ceramic material designs and industrial applications.

2.1 Biomedical application

Biomedical alloys used as bioimplant materials are widely used in the treatment/replacement of human parts such as teeth, bones, and joints. Biomedical alloys are more demanding due to their unique characteristics, needing good biocompatibility, good mechanical properties, and excellent corrosion resistance (Khan et al. 1999; Kobayashi et al. 1995; Long and Rack 1998; Wang 1996; Yu et al. 2016). Fortunately, Zr alloy and a few other alloys possess most of these characteristics. Among the known biomedical alloys, Zr alloys are valued as an outstanding choice not only because of the combination of the required properties listed but also because of its low magnetization rate (Hume-Rothery et al. 1969; Kalavathi and Bhuyan 2019; Ren et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2022a,b). Studies (Suyalatu et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2022a,b) have demonstrated unequivocally that Zr alloy, as a biomedical material, has no adverse effects on humans. Figure 1 presents an image of a typical Zr alloy used as dental implants.

The origin of the applicability of Zr alloys as biomedical materials can be traced back to the 1990s, when Smith and Nephew Richards developed the Zr–Ti–Nb alloy (Long and Rack 1998; Wang 1996; Zhang et al. 2022a,b). The material has the advantages of low elastic modulus and good biocompatibility. However, further investigations revealed that Zr–Ti–Nb alloy had a low strength (Jin et al. 2016; Niimomi et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017). Subsequently, researchers conducted further investigations and discovered that alloying the originally developed Zr–Ti–Nb alloy with Fe can enhance the superelastic strain or shape memory strain of the alloy (Yu et al. 2016). Thus, alloying with Fe was recommended. With the rapid development of technology, the development of biomedical Zr alloys have greatly improved, and as such, several alloys like Zr–Mo type β-Zr alloys, Zr–Nb alloys, Zr–Mo–Ti alloys have been developed and applied.

2.2 Chemical industry application

With the development of the chemical industry, Zr alloys are increasingly used in many chemical plant components that are exposed to highly corrosive and aggressive environments. This is due to the excellent corrosion resistance of Zr alloys to most mineral acids, organic acids, and alkalis. The high corrosion resistance of Zr in most media is attributed to the formation of a thin self-regenerating oxide film on its surface upon exposure to a corrosive environment (Jin et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2022a,b). Table 1 lists the corrosion resistance potential of Zr alloys in various chemical media, which is extrapolated from previous studies (Jin et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2016; Northwood 1985; Schemel 1977; Zhang et al. 2022a,b). As can be seen from Table 1, Zr is resistant to most of the aforementioned environments; however, the case is different for environments containing any of the following; fluoride ions, bromide ion, aqua regia, concentrated sulfuric acid, ferric chloride, and cupric chloride, where it is observed that Zr alloy loses its excellent corrosion resistance.

Corrosion resistance of Zr in different environments (data extracted from Northwood 1985 and Schemel 1977).

| Electrolyte | Temperature (°C) | Concentration (wt%) | Corrosion rate (MPY) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic acid | Boiling | 5, 25, 50, 75, 99.5 | <1 |

| Acetic acid vapor | Boiling | 33 | <5 |

| Acetaldehyde | Boiling | 100 | <2 |

| Acetic-glacial acid | Boiling | 99.7 | <5 |

| Aluminum chloride (aerated) | 60 | 5, 10 | <2 |

| Aluminum sulfate | 100 | 60 | <2 |

| Ammonia | 38 | Plus water | <2 |

| Ammonium chloride | 100 | 1, 40 | <5 |

| Ammonium sulfate | 100 | 5, 10 | <5 |

| Aniline hydrochloride | 100 | 5, 20 | <5 |

| Aqua regia | 77 | 3:1 | >50 |

| Barium chloride | 100 | 5, 20 | <5 |

| Barium chloride | Boiling | 25 | 5 to 50 |

| Bromine | Room | Water | >50 |

| Chlorine (water saturated) | Room | – | >50 |

| Chlorine gas (>0.13 % H2O) | 93 | 100 | >50 |

| Cupric chloride | Boiling | 20, 40, 50 | >50 |

| Ferric chloride | Room | 5, 10, 20, 30 | >50 |

| Hydrobromic acid | Room | 40 | >50 |

| Hydrofluoric acid | Room | 48 | >50 |

| Sulfuric acid (air) | Room | 15 | <20 |

Over the years, a number of corrosion-resistant Zr alloys have been developed and used in various applications in the chemical industry, as shown in Table 2. From Table 2, it is seen that Zr701 is used as laboratory crucibles (shown in Figure 1), while Zr702 – Zr705 are used in applications like chemical plant heat exchangers, chemical equipment pipings, and so on (shown in Figure 1). Furthermore, Table 2 shows that the strength of the alloy increases as other alloying elements in the Zr alloy increase. However, this has a diminishing effect on the excellent fabricability of Zr alloys, as seen in the characteristic’s column in Table 2.

Several developed commercial Zr alloys for chemical application and their characteristics.

| Zr alloy designate (ASTM) | Alloying elements (wt%) | Physical properties | Characteristics | Application | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength (20 °C) | Yield strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) | Modulus of elasticity (GPa) | |||||

| 701 | Zr + Hf 99.5 (min); Hf < 4.5; Fe + Cr 0.10; H 0.005; N 0.05; C 0.03 | 380 | 205 | 28 | 99 | Excellent fabricability | Laboratory crucibles | Northwood (1985) |

| 702 | Zr + Hf 99.2 (min); Hf < 4.5; Fe + Cr 0.20; O 0.16; H 0.005; N 0.05; C 0.03. | 450 | 310 | 25 | 99 | Good fabricability, excellent corrosion resistance | Chemical equipment heat exchangers | Chang (2003) |

| 704 | Zr + Hf 97.5 (min); Hf < 4.5; Sn 1.00–2.00; Fe + Cr 0.20–0.40; O 0.18; H 0.005; N 0.025; C 0.03. | 485 | 380 | 20 | 100 | Fair fabricability, good corrosion resistance | Chemical equipment heat exchangers | Lemaignan and Motta (1994) |

| 705 | Zr + Hf 95.5 (min); Hf < 4.5; Nb 2.00–3.00; Fe + Cr 0.20; O 0.18; H 0.005; N 0.025; C 0.05. | 585 | 450 | 20 | 97 | Fair fabricability, good corrosion resistance | Chemical equipment piping and heat exchangers | Warlimont and Martienssen (2018) |

2.3 Nuclear application

Zirconium alloy is a viable material choice for nuclear reactor components owing to its low neutron absorption, thermal stability, and excellent corrosion resistance. Specifically, Zr alloys are used in making fuel cladding tubes of a nuclear reactor, as well as rod guide tubes, pressure tubes, etc. (Zhang et al. 2022a,b), as depicted in Figure 1. Fuel cladding is a material component used to encapsulate nuclear fuel pellets in pressurized and boiling water reactors. They provide a barrier against the release of fission products into the primary circuit.

Only a few Zr alloys are of commercial importance. At present, commonly used Zr alloys are Zircaloy-2, Zircaloy-4, Zr-2.5Nb, and recently developed advanced Zr alloys (Northwood 1985). In the 1950s, the development of Zr alloys for nuclear fuel cladding originated in the USA under the US Nuclear Navy program (Lustman 1979; Rickover et al. 1975a,b). Over time, as research progressed, it was found that, contrary to other alloys, the corrosion performance of Zr alloy used for nuclear fuel cladding decreased as the purity of the alloy increased (Motta et al. 2015). Further investigations (Kautz et al. 2023; Motta et al. 2015) revealed that almost any alloying element addition (typically < 0.5 %) is adequately enough to cause a noticeable change in the corrosion behavior of the Zr alloy. The realization of this sensitivity of Zr alloys corrosion behavior to the addition of other alloying elements caused a systematic search for alloying element(s) that can improve both corrosion resistance and mechanical properties while maintaining their low neutron absorption ability. This has led to two progressive directions in the development of nuclear grade Zr alloys: one is the Zr–Sn alloy-based system developed in the United States, and the Zr–Nb alloy-based system developed in Russia and Canada (Hillner 1977; Ibrahim and Cheadle 1985; Rickover et al. 1975a,b).

In recent years, to ensure the enhancement of nuclear reactor safety and reliability, economic efficiency of nuclear energy, and extend the useful life of nuclear materials, the nuclear industry has put forward more stringent requirements for Zr alloys in terms of corrosion resistance and irradiation resistance, as well as high temperature mechanical properties. Consequently, several new alloys have been successfully researched and developed in various countries for nuclear applications, as discussed in the next section.

3 Nuclear grade Zr alloy development history

Arguably, it can be said that most of the designed and developed Zr alloys are applied in the nuclear industry. To date, nuclear grade Zr alloy development efforts have focused on developing materials with better irradiation creep resistance, improved corrosion resistance, reduced hydrogen pickup potential, and reduced amount of irradiation growth. In addition, the development direction of nuclear grade Zr alloy is targeted at developing alloys with increased strength to enable the development of structural components with reduced wall thickness. This is advantageous in decreasing the number of neutrons absorbed by materials in the core of the reactors.

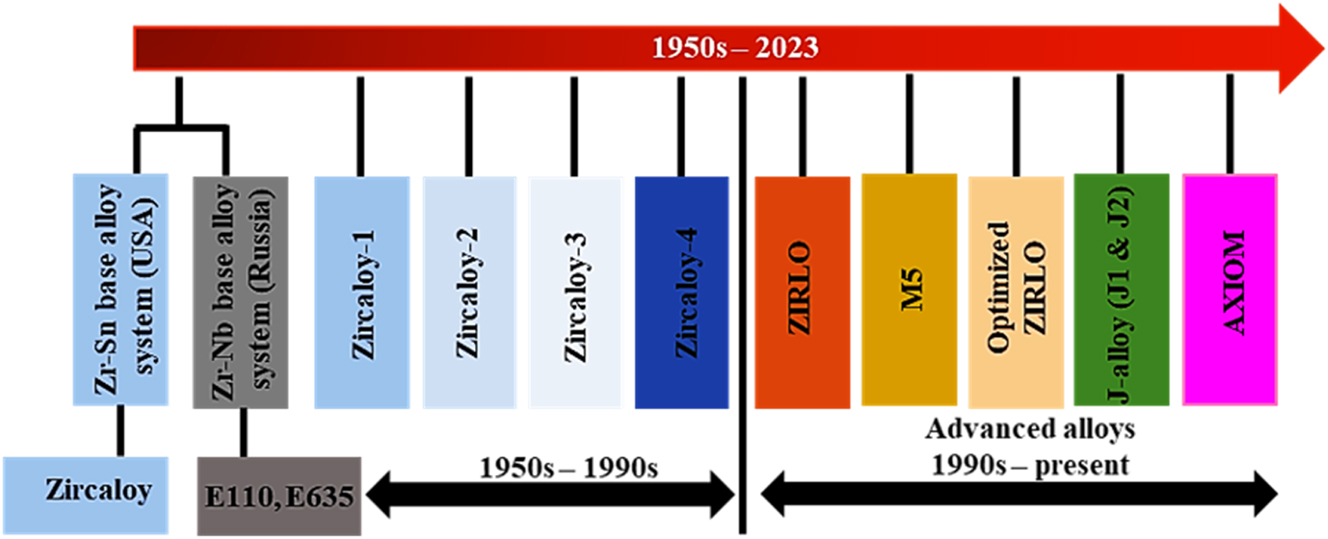

As mentioned earlier, two major alloying systems, Zr–Nb based system and Zr–Sn based system, were considered from the onset of nuclear grade Zr alloy development. Regarding systems based on Zr–Nb, development began with the development of alloy E110, which is used in VVERs (i.e., the Russian replica of the western pressurized water reactors (PWRs)). The further development of the E110 alloy gave rise to the alloy E635, which is comprised of Nb and Sn. The Sn addition was noticed to reduce the creep rate, thus lowering the Nb requirement. For Zr–Sn based system, Zircaloy-1 was the first alloy to be developed, with a nominal composition of Zr-2.5 % Sn (Kautz et al. 2023; Rickover et al. 1975a,b). This alloy functioned reasonably well but was improved upon by the serendipitous discovery of the positive effect of minor element addition in the Zircaloy-1. Thereafter, Zircaloy-1 gave way for Zircaloy-2, which consisted of Zr-1.5 % Sn, 0.10 % Cr, 0.06 % Ni, 0.14 % Fe (Kautz et al. 2023; Rickover et al. 1975a,b). The Sn content of Zircaloy-2 was reduced to 1.5 % from Zircaloy-1, and in some cases lower than 1.5 %, even with the observed advantage of Sn in lowering the creep growth rate of the alloy. This is because it was noticed that increasing the Sn content in Zr alloy beyond 1.5 % increases its corrosion rate (Motta et al. 2015). Further advancement in the Zr–Sn based alloy led to the replacement of Zircaloy-2 with Zircaloy-4. This occurred after it was noticed that the Ni addition in Zircaloy-2 was related to high hydrogen pickup and the failure of Zircaloy-3 owing to metallurgical processing problems (Kass 1964; Lustman 1979). In Zircaloy-4, an increased content of Fe in the alloy substituted for Ni. Historically, these alloys were mainly used between the 1950s and 1990s, as shown in Figure 2. While Zircaloy-4 was used in the PWRs, Zircaloy-2 was used in boiling water reactors (BWR) (Whitmarsh 1962).

Development series of Zr alloys with time.

Entering the early 1990s, a major chunk of research was focused on improving or replacing Zircaloy-4 owing to the higher operating temperature of PWRs, as compared to that of BWRs. The departure from Zircaloy-4 started in 1987 by the initiation of an assembly with ZIRLO fuel cladding material (Sabol et al. 1994, 2005). This progress in the development of zirconium alloy was aimed at meeting the higher demands of the nuclear industry at that time (namely higher fuel duty) and recently, higher coolant temperatures to improve efficiency, extended cycle length, and tolerate more aggressive chemistry. ZIRLO showed improved corrosion resistance than Zircaloy-4, as seen in Leech and Yueh (2001) and Motta et al. (2015).

Concurrently, the alloy development effort of M5 occurred in the early 1990s. The M5 alloy is a completely recrystallized ternary alloy of Zr–Nb–O with controlled contents of minor alloying elements like Cr, Fe, and S (Mardon et al. 2010, 1997; Motta et al. 2015). A comparison study of the oxidation behavior of M5 claddings and Zircaloy-4 claddings in the reactor environment was carried out by Mardon et al. (2010), and they reported that the differentiating characteristics of M5 is the absence of enhanced corrosion at burnups above 30 GW-day per metric ton of uranium (GWD/MTU). Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, M5 and ZIRLO became the dominant alloys for replacing Zircaloy-4 in PWRs globally.

Following the introduction of M5, optimized ZIRLO was proposed and produced. This alloy was designed to maintain the beneficial properties of ZIRLO, while improving corrosion resistance. The concept of the optimized ZIRLO alloy stems from the recognition of the beneficial effect of reduced Sn content on corrosion (Mitchell et al. 2010; Pan et al. 2013). Based on this finding, optimized ZIRLO was developed to contain 0.67 % Sn in its alloy. To ascertain the superior performance of the optimized ZIRLO, a study was conducted comparing the optimized ZIRLO and ZIRLO alloys as fuel rods (Motta et al. 2015; Romero et al. 2014). From the study, it was observed that the oxide thickness of the optimized ZIRLO was ⁓40 % less than that of ZIRLO (Motta et al. 2015; Romero et al. 2014). In addition, from the study, it is observed that compared to ZIRLO cladding, optimized ZIRLO cladding demonstrated lower oxide thickness, and corrosion enhancement or breakaway corrosion was delayed up to 45 GWD/MTU, which is higher than that of the conventional ZIRLO alloy.

After the success of optimized ZIRLO, other development programs discovered new Zr alloys with improvement in corrosion performance under irradiation to high burnups. One family of alloys is the J-alloys, which are J1 and J2. These alloys have attained rod average burnups of ⁓68 GWD/MTU following three cycles of irradiation, which gives a comparison of the burnup efficiency of the J-alloys as compared to Zircaloy-4 (Motta et al. 2015; Yoshino et al. 2014). The J-alloys contain a higher Nb level than M5 and E110.

Another advanced Zr alloy developed recently are the AXIOM alloys, which achieved a burnup greater than 70 GMD/MTU (Mitchell et al. 2010; Motta et al. 2015; Pan et al. 2010, 2013). Table 3 contains different developed AXIOM alloys. From Table 3, it is seen that three out of the five developed alloys are composed of low levels of Sn, with the Nb content of the alloys is between 0.3 and 1 %. The improvement in corrosion performance of the AXIOM alloys as a function of burnup were clearly demonstrated in a study conducted by Pan et al. (2010), which showed a comparison plot of oxide thickness vs. burnups of AXIOM alloys and ZIRLO.

Chemical composition of different grades of AXIOM Zr alloy.

| Alloy | Sn (wt%) | Nb (wt%) | Fe (wt%) | Cr (wt%) | Cu (wt%) | V (wt%) | Ni (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AXIOM X1 | 0.3 | 0.7–1 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.2 | ||

| AXIOM X2 | 1 | 0.06 | |||||

| AXIOM X4 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.08 | |||

| AXIOM X5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.05 | ||

| AXIOM X5A | 0.45 | 0.3 | 0.35 | 0.25 |

Since the introduction of advanced alloys in the 1990s (as shown in Figure 2), significant in-reactor corrosion performance has been achieved in terms of behavior of the alloys. Compared to Zircaloy-4, the advanced alloys not only exhibit a lower oxide thickness but are also suitable for higher demands of current reactor environments such as increasing coolant temperature and increasing cycle time. To date, one of the challenges in new alloy development for nuclear grade Zr has been to determine the out-of-pile characterization that could provide sufficient confidence to invest resources toward commercializing and obtaining experience for licensing of the new/advanced alloy for reactor usage. This concern has led to several projects that could correlate the autoclave performance of Zr alloys and in-reactor performance (Sabol et al. 1994). In a study carried out by Sabol et al. (1994), it was observed that the initial transition in corrosion kinetics in autoclave corrosion test of advanced alloys took a longer time, indicating a decrease in post-transition corrosion rate. This characteristic is also reflected in the corrosion experience of the advanced alloys in the reactor environment, which exhibited lower corrosion. Although autoclave testing in 360 °C primary water can demonstrate periodic growth of the oxide, it does not exhibit the enhanced corrosion observed by Zircaloy-4 in-reactor exposure at burnups above 30 GWD/MTU. There are numerous proposed explanations for enhanced in-reactor corrosion, including radiation enhancement from neutron or gamma flux, change in microstructure such as dissolution of secondary phase precipitates (SPPs), influence from the formation of a hydride rim, and water chemistry (Motta et al. 2015). However, so far, it is unclear how these proposed explanations lead to changes in the oxidation mechanism, which in turn leads to the enhancement of corrosion noticed during increased burnups. The understanding of the mechanisms of this salient oxidation behavior is a key area of recent research.

In the wake of reactor accidents, it is becoming increasingly essential to understand the mechanism of Zr alloy degradation in the harsh environment of a nuclear reactor, either during normal operations or accident scenarios. As a result, studies have been carried out and are still being conducted worldwide toward this goal. The next section summarizes the understanding of the degradation mechanisms of Zr alloy gathered from previous works.

4 Degradation mechanism of nuclear grade Zr alloy

As mentioned earlier, dynamic material effects and the extreme environment in the primary circuit of a NPP makes it difficult to predict or monitor Zr cladding condition in the core. This inevitably poses significant obstacles to achieving a comprehensive and unified understanding of the degradation mechanism of cladding (Cox 2005; Yan et al. 2015). Notwithstanding, several studies have identified two main degradation mechanisms of nuclear grade Zr alloys in use, namely corrosion and hydrogen uptake. Both mechanisms will be discussed in detail in this section.

4.1 Corrosion degradation mechanism

4.1.1 Corrosion basis

Typically, oxidation of Zr alloys exposed to aqueous medium initially occurs through the following reaction (Equation (1)) at the metal/oxide interface and grows inward by oxygen diffusion through oxide grain boundaries or the bulk of oxide grains (Annand et al. 2015; Couet et al. 2015a; Hudson et al. 2009; Ni et al. 2011b).

As seen in Equation (1), the product of Zr metal reaction with water obtainable in the primary circuit of NPPs are zirconia (ZrO2) and hydrogen, some of which gets picked up by the metal (Kautz et al. 2023; Motta et al. 2015). Zr oxidation is driven by the high free energy of the Zr oxide formation reaction, which is about 965 kJ/mol at 360 °C (Arima et al. 1998; Fuketa et al. 1996). Due to the oxidative thermodynamics of the Zr alloy and the environment in which the material is exposed under operating condition, electrochemical potentials are established at the oxide layer (i.e., oxide/water and oxide/metal) interface, which drives the transport of atomic species across the oxide film. In this process, the reactions at the oxide/water and oxide/metal interfaces are influenced by the transport of electrons, vacancies, and H+ and O2− species.

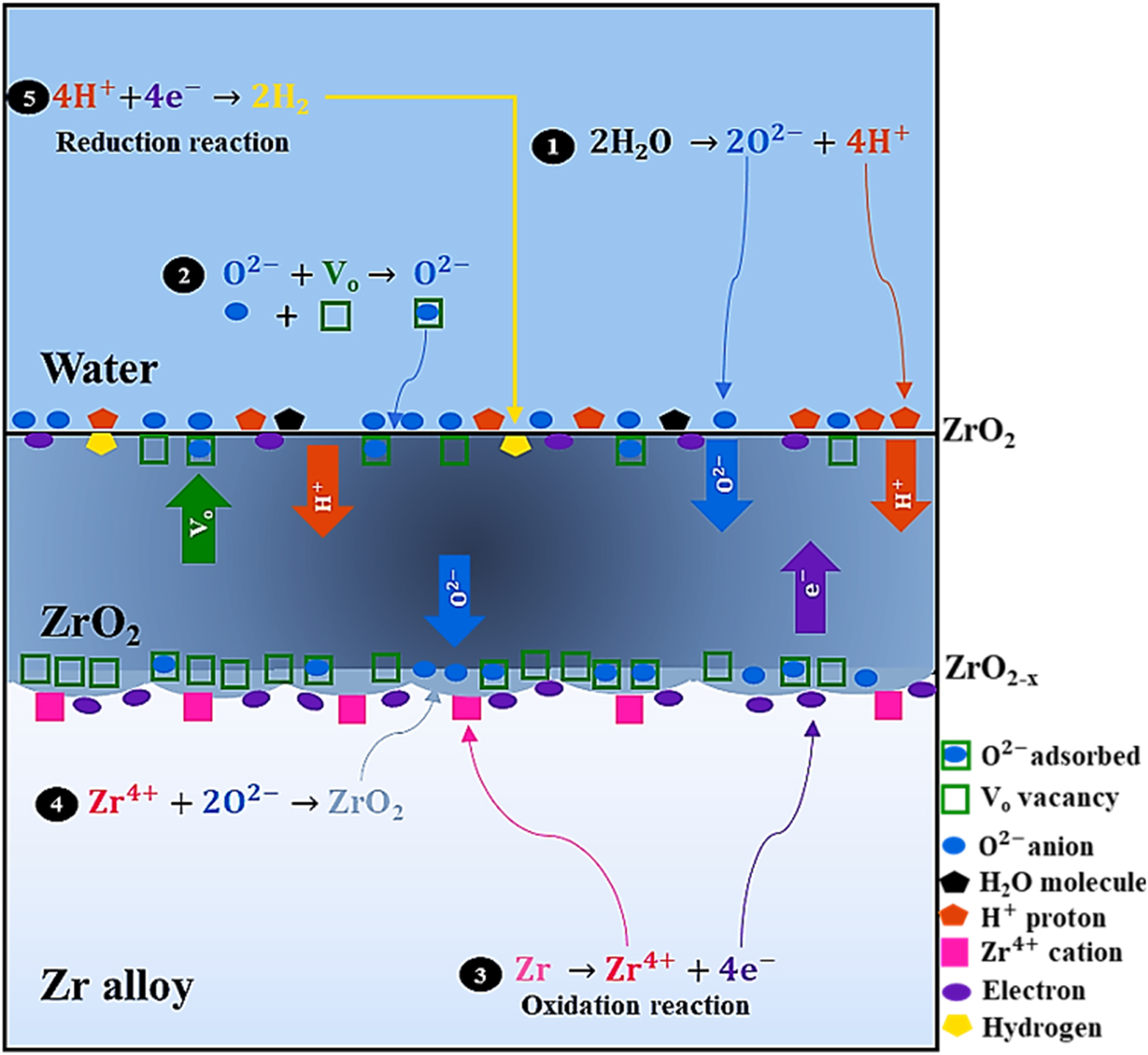

Overall, the oxidation process of Zr alloys involves several chemical reactions that are divided into several steps, which are represented and described with the equations and schematics in Figure 8, respectively. First, dissociation of water molecule occurs to form H+ and O2− ions, and O2− is adsorbed onto the oxide film surface at any oxygen vacancy site, as shown in reaction 1 and 2 in Figure 3. Thereafter, the O2− diffuses through the oxide via solid-state diffusion (Cox 1968; Ma et al. 2008) either along high diffusivity paths, such as oxide grain boundaries, or through the oxide bulk. This occurs due to the defect concentration gradient (Kautz et al. 2023; Ma et al. 2008) and electric potential across the oxide (Couet et al. 2015a; Fromhold 1978, 1979; Ma et al. 2008). Upon reaching the oxide/metal interface, O2− reacts with Zr cations (formed by the oxidation reaction 3 in Figure 3) to form new oxides, as shown in reaction 4 in Figure 3. This reaction generates oxygen vacancies and releases electrons, which then migrates through the oxide to the oxide/water interface via a hopping mechanism to reduce the hydrogen ions at the cathodic side (Ramasubramanian 1975), as represented in reaction 5 in Figure 3. However, not all H+ is reduced, and some are reported to diffuse through the oxide toward the base metal, where H+ can either be in solid solution or precipitate as hydride (Kofstad 1972). This phenomenon is known as hydrogen pickup. It is important to emphasize that it is still unknown whether the location of the cathodic site is at the oxide/water interface or within the oxide, and as such, further research on this finding is encouraged.

A schematic of the chemical processes involved in Zr alloy oxidation.

The corrosion of Zr alloy, as described in Equation (1), is known to be one of the limiting factors for the operation of nuclear fuel of high burnups and more extreme conditions, as well as the campaign for the prolongation of fuel usage in the nuclear industry (Buscail et al. 2018; Matsukawa et al. 2017; Okonkwo et al. 2019, 2021a,b,c). In order to maintain the integrity of the Zr alloy material components, a deeper understanding of the corrosion mechanism of Zr alloy is needed.

4.1.2 Corrosion kinetics model

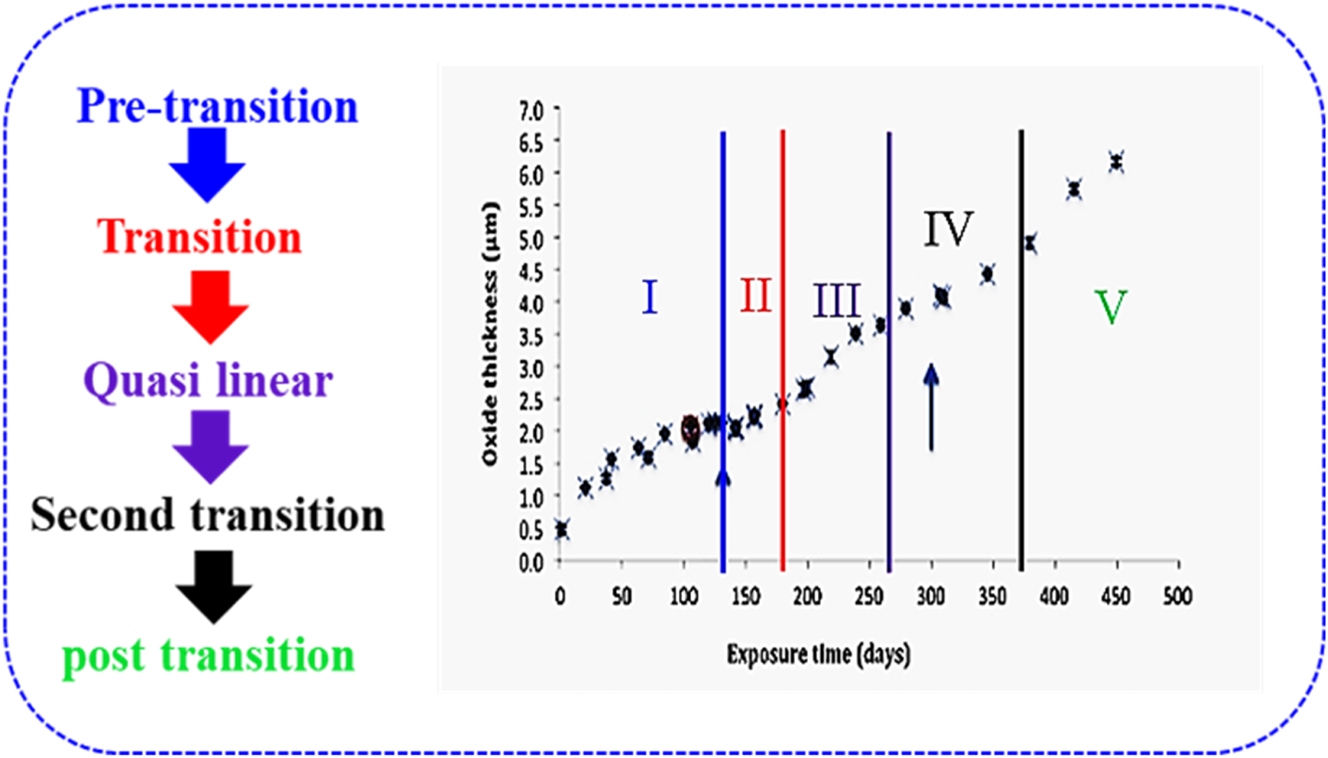

According to literature (Garner et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2018a,b; Yilmazbayhan et al. 2004; Zumpicchiat et al. 2015), the long-term corrosion model of Zr alloys can be categorized into five vital stages, which are as follows:

Initial stage: In this stage, the corrosion kinetics related to the oxide thickness follows a time-dependent parabolic pattern (Couet et al. 2015b; Garner et al. 2015; Ni et al. 2011a). As depicted in Figure 4, the initial stage is within the first 130 days for Zircaloy-4 exposed to simulated PWR environment at 350 °C, and it is also known as the pretransition stage. Subsequently, when the oxide film thickness of the Zr alloy reaches a value of 2–3 µm, transition of corrosion process occurs, indicating the entrance of the second stage (the time and oxide thickness that transition occurs at is dependent on the particular Zr and exposure conditions – primarily temperature).

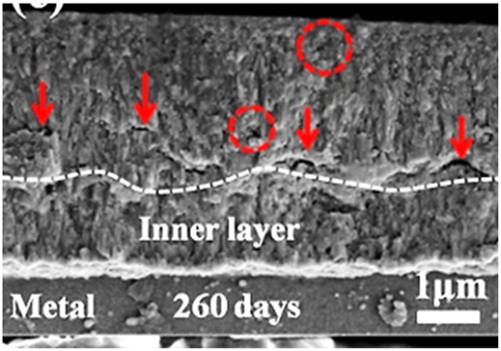

Transition stage: The transition stage is characterized by an abrupt acceleration of the corrosion rate (as shown by the arrow at 130 days in Figure 4) and the formation of a lateral crack band near the interface, as indicated with arrows in Figure 5 (Liao et al. 2018a,b; Shi et al. 2020; Yilmazbayhan et al. 2004).

Quasi linear stage: After the first transition point, corrosion undergoes a periodic stage with periodic weight gain profile and periodic transitions. This stage is referred to as the quasi-linear stage and can also be regarded as the transitory stage (Liao et al. 2018a,b; Yilmazbayhan et al. 2004). This stage is the period between 150 and 260 days in Figure 4. However, it is important to note that this stage is depended on temperature, irradiation condition, and alloy under exposure, as observed in Garner et al. (2015).

Second transition stage: After some periodic transitions, the fourth stage, namely the second transition, will occur (Liao et al. 2018a,b; Zumpicchiat et al. 2015). The second transition, as characterized by the break-away of the protective oxide film, will lead to an intense increase in corrosion kinetics/oxide film growth. In Figure 4, this stage is indicated with the second arrow at 300 days of exposure. As described in Ensor et al. (2019b), this fourth stage is generally induced by irradiation. In such cases, it is important to point out that the time for this stage depends particularly on temperature and flux level.

Linear corrosion stage: This is the final stage of the Zr alloys corrosion process. At this stage, the corrosion kinetics experiences a linear increase over time, as indicated from 350 days and above in Figure 4. Some authors say that the linear increase in corrosion rate at this stage is possibly due to the formation of a hydride rim in the outermost matrix of the Zr material (Garde 1991; Zumpicchiat et al. 2015). Under irradiation, this stage has substantially higher corrosion rates as compared to out of reactor as described in Kammenzind et al. (2018) study.

Corrosion curve for Zircaloy-4 exposed to simulated PWR condition extrapolated from previous study (Garner et al. 2015). Adapted from an open access publication.

Fracture surface morphologies of the oxide films formed on Zr–Mo alloys exposed to simulated PWR primary water environment for 260 days, adapted from (Shi et al. 2020).

Although, these five stages exist in most Zr alloys, especially in the traditional Zircaloys, several studies have pointed out that the corrosion of advanced Zr alloys (claddings) like M5 and others listed in Figure 2 do not exhibit the second transition stage, even at relatively higher burnups (Liao et al. 2018a,b; Northwood 1985). Therefore, among the five stages, the behavior of the specific Zr alloy in the transition stage determines its corrosion resistance. At this stage, the transition time is one of the factors controlling corrosion resistance, and a longer transition time results in obvious benefit. While it is well known that the transition stage of Zr alloys is crucial, the corrosion transition mechanism of Zr alloys remain controversial. So far, two leading hypotheses have been proposed as possible transition mechanisms (Liao et al. 2018a,b; Northwood 1985). One is stress accumulation, while the other is the tetragonal (t)-phase to monoclinic (m)-phase transformation in ZrO2 oxide film formed on the oxidized Zr alloy. Although, these two mechanisms have been proposed, the relationship between them and how they develop with time remains unresolved so far.

4.1.3 Oxide structure and oxide/metal interface structure

4.1.3.1 Zr oxide film structure

The oxide film formed on most nuclear grade Zr alloys on exposure to a corrosive aqueous medium is protective and grows evenly on its surface, unlike the oxide formed on a pure Zr metal (Motta et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2017). The protective nature of the Zr film occurs as a result of the homogenous covering of the base metal by the oxide film, where further corrosion of the alloy must occur by O2− diffusion through the oxide film toward the oxide/metal interface. With the continuation of O2− diffusion through the oxide film, cavities, porosity, and microcracks develops, leading to macroscale cracking over time (Kautz et al. 2023).

Literature have shown that the microstructure and texture of Zr oxide film varies with alloy chemistry and corrosion environment. As a consequence, comprehensive studies have been carried out on the morphology and structure of the oxide films of various Zr alloys, which have yielded great insights into the growth mechanism of Zr alloys oxide layers when exposed to a corrosive environment (Motta et al. 2015; Yilmazbayhan et al. 2004). Also, from previous studies (Motta et al. 2015; Yilmazbayhan et al. 2004), it has been emphasized that the oxide structure and texture of Zr alloys are important for understanding the source of stress in the oxide and the relationship between stress and kinetic transitions observed during long-term corrosion. From microstructural observations, it is evident that the oxidation of Zr alloy begins with the formation of randomly oriented small equiaxed oxide grains on the alloy (Gabory and Motta 2013). These equiaxed grains consist of a mixture of t-ZrO2 and m-ZrO2 crystal structures, typically in the diameter range of 10–50 nm, dependent on temperature. As the grain grows, usually with the threshold grain size of ⁓30–40 nm in diameter, the equiaxed grains transform into properly oriented columnar grains that grow in length to ⁓200 nm, perpendicular to the oxide/metal interface. This transformation process minimizes stress accumulation in the oxide. The threshold grain size diameter mentioned above (⁓30–40 nm) is the diameter at which the stable m-ZrO2 phase becomes favored over continued growth of t-ZrO2 phase. However, it is important to emphasize that the transformation of grains is temperature condition dependent.

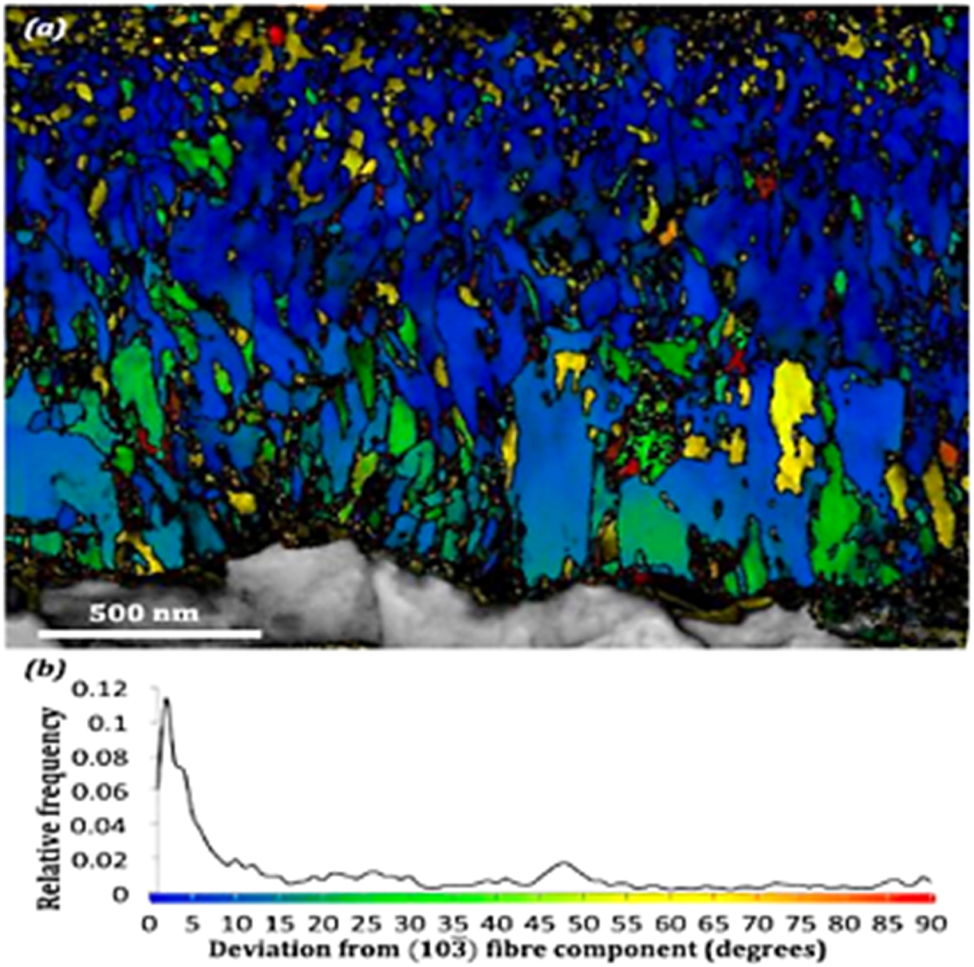

Retrospectively, several studies have shown that the anisotropic columnar growth results in a fiber texture, as shown in Figure 6 (Li et al. 2004). However, some discrepancies exist, which has been attributed to different possible orientations of monoclinic grains. Recently, the utilization of high-resolution grain mapping techniques, such as TEM crystal orientation mapping, has provided deeper insights into the oxide characterization of Zr alloys compared to the traditional use of XRD and Raman mapping (Garner et al. 2014a; Kim et al. 2015). As shown in Figure 6, the TEM mapping of grain-to-grain orientation of the Zr alloy showed a highly textured grain, which varied in grain morphology (Garner et al. 2014b). In addition, it is seen from Figure 6 that the oxide consists of both t-ZrO2 and m-ZrO2 grains; however, the t-ZrO2 phase fraction is observed to decrease moving away from the oxide/metal interface toward the outer oxide. Another important observation from Figure 6 is that, new tetragonal grains can form where columnar grains terminate, which may result in cluster of tetragonal grains at oxide regions away from the oxide/metal interface (Garner et al. 2014a; Motta et al. 2005).

Orientation mapping of Zr oxide formed on Zircaloy-4 exposed to simulated PWR conditions at 350 °C for 106 days determined via automated crystal orientation mapping in TEM. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article adapted from (Garner et al. 2014b).

In regards to the origin of stress in the oxide film, it has been reported that as the oxide grows, stress accumulates in the oxide layer due to the imperfect accommodation of the volume expansion associated with oxidation (Polatidis et al. 2013). In-plane stresses on the order of 1–3 GPa have been measured in growing ZrO2 oxide film at various stages of film growth (Polatidis et al. 2013). The increase in stress in the oxide film often leads to the formation of lateral cracks, and in turn, causes an interlinkage of the porosity from the oxide/metal to the oxide/water interface. This phenomenon provides an easy access to the water, which invariably increases the corrosion rate. When this occurs, the abrupt nature of the transition is then related to the sudden oxide breakup after the stress reaches a critical value (Motta et al. 2005). As mentioned earlier, this is thought to be one of the mechanisms associated with oxide transition. Based on this mechanism, it can be inferred that different stress accumulation rates will lead to different transition times between Zr alloys as the oxide grows. The idea is that different alloys would cause the volume expansion to be accommodated slightly differently, resulting in different levels of stress accumulation such that the oxide transition occurs at different times. Although various measurements of stress in growing oxides have been made (Bechade et al. 2002; Goudeau et al. 2006; Polatidis et al. 2013), the question of how different Zr alloys causes a differentiated accommodation of strain that results in different stress accumulation and different transition times has yet to be elucidated. Alternative, but related hypotheses to this mechanism have also been proposed. This originates from observations that suggest that lateral cracking occurs following transition of the Zr alloy (Gass et al. 2018). It may be that porosity percolation leads to water obtaining access to the oxide/metal interface (Zhang et al. 2024; Zhang et al. 2022a,b; Zhao et al. 2024). More research into these mechanisms is needed.

4.1.3.2 Zr oxide/metal interface structure

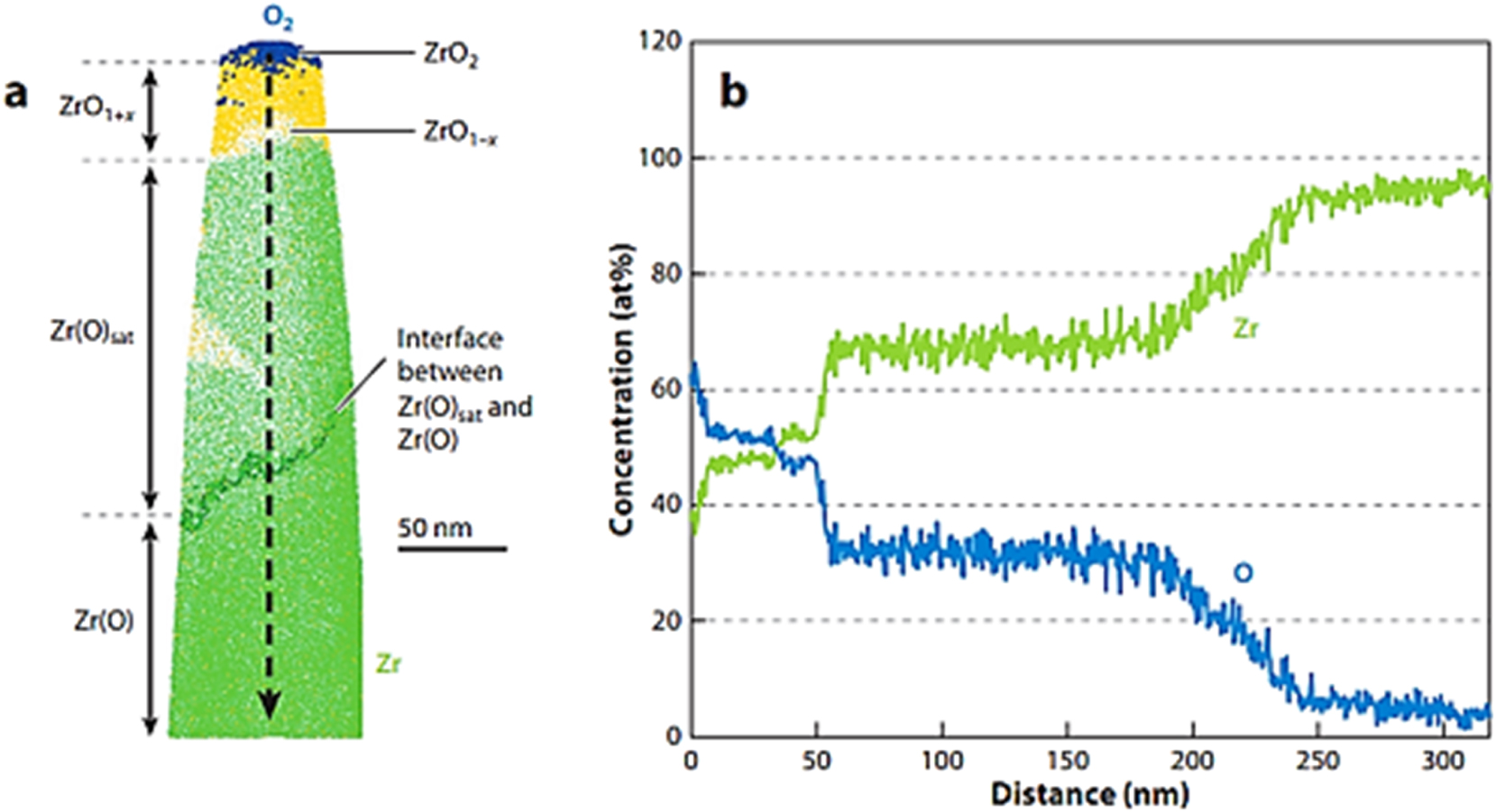

According to the ZrO phase diagram, there is an equilibrium between Zr and ZrO2 at the oxide/metal interface, with approximately 28 at.% O in solid solution (Abriata et al. 1986). However, in reality, this equilibrium is never established, as the oxide/metal interface constantly moves into the metal during oxidation, thus consuming nearby metal. Notwithstanding, the metal region near the oxide/metal interface is clearly different from the rest of the metal, with several metastable phases reported (Yilmazbayhan et al. 2004). In a study conducted by Dong et al. (2013), atomic probe analysis was used to show the sequence of phases formed at the oxide/metal interface of a Zr alloy, and the result is depicted in Figure 7. From Figure 7, the cross-sectional study of the oxide film can be seen as geological strata, in which different structures are formed and deposited at different times. Thus, by backtracking from the oxide/metal interface and understanding the corrosion kinetics, it is possible to determine when the transition occurred and relate the corrosion kinetics and the occurrence of the transition to oxide features.

Zircaloy-4 oxide region: (a) 10 nm slice from an APT reconstruction showing the presence of different oxide phases; (b) concentration profile taken along the arrow indicated in (a). Adapted from (Dong et al. 2013).

Recently, the study of the oxide layer of Zr alloy at different oxidation stages by combining advanced techniques like TEM and atom probe has found that three different phases can be seen at the oxide/metal interface during the pretransition period (Dong et al. 2013; Gabory et al. 2015; Ni et al. 2011a; Peng et al. 2007): First, is the small intermediate layer identified as cubic ZrO phase; second, is the blocky grains found at some places along the interface, with diffraction patterns indexed as Zr3O; and third, is an oxygen-saturated suboxide layer in the metal. The width of these interfacial regions decreases remarkably at transition, likely because the high corrosion rate at transition do not give them enough time to form. Although a great deal of knowledge has been gained about the structure of these oxide layers, the core question of how alloying elements contribute to oxide growth stabilization remains unclear. According to literature (Cox 2005; Cox and Pemsler 1968), the alloying elements are clearly associated with different pretransition oxidation kinetics; thus, an understanding on the effect of alloying elements will be necessary.

4.1.4 Tetragonal to monoclinic phase transformation in ZrO2

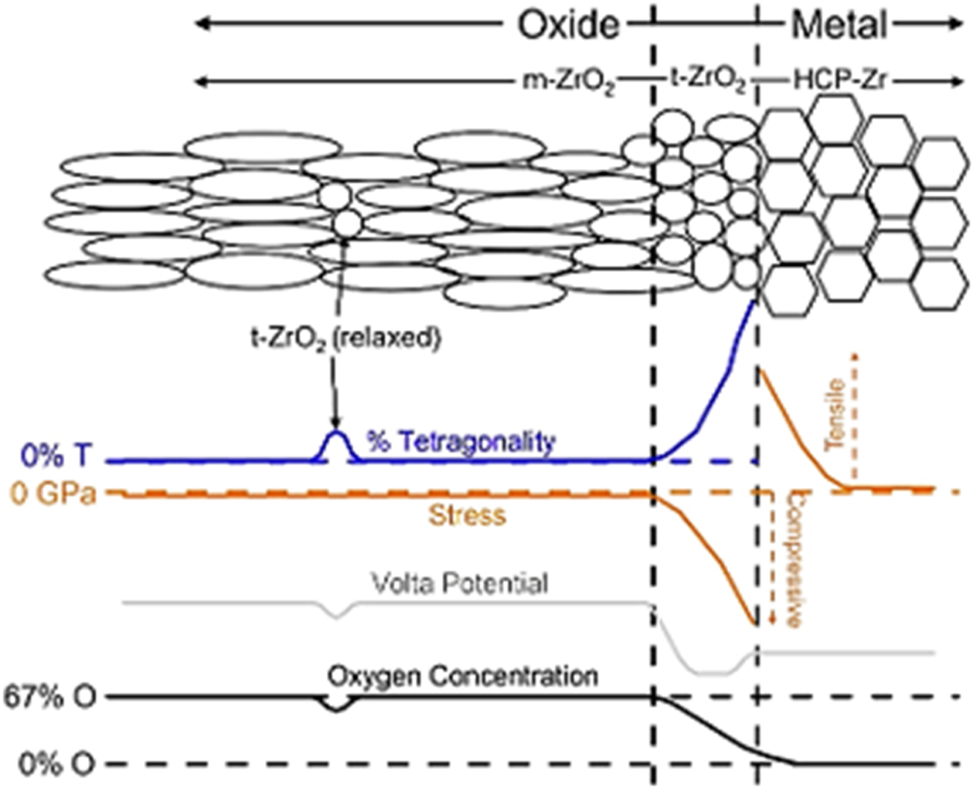

In addition to the evolution of oxide composition, structural changes also occur during the corrosion of Zr alloys, most notably the transformation from metastable t-ZrO2 m- to the stable m-ZrO2, (Ensor et al. 2019a; Hillner 1977; Motta et al. 2005; Muthu et al. 2023; Okonkwo et al. 2023, 2024; Yilmazbayhan et al. 2004). The metastable t-ZrO2 phase fraction in oxides of different Zr alloys has been found to vary with alloy chemistry and has been reported in several references to exist at the interface, with a small amount embedded in the film, as shown in the schematics in Figure 8 (Efaw et al. 2020).

Schematic summarizing the different parameters for each zirconia and zirconium phase. Adapted from (Efaw et al. 2020).

Interestingly, a review of previous studies has raised an argument on the effect of t-ZrO2 content on Zr alloy corrosion behavior. In this argument, some authors believe and have associated the protective oxide of ZrO2 as the t-phase. While some other authors have associated the t-ZrO2 to m-ZrO2 transformation as one of the mechanisms or causes of transition (Bouvier et al. 2002; Efaw et al. 2020), so a higher t-ZrO2 phase will lead to more phase transformation, which is detrimental. However, it is vital to emphasize that more t-ZrO2 phase forms when the metal interface experiences increased stress (Ensor et al. 2019a). In a study carried out by Efaw et al. (2020), they noted that the transformation of the t-ZrO2 to m-ZrO2 introduces strain in the oxide due to the different volumes of the t-ZrO2 versus m-ZrO2 unit cell, which leads to volumetric expansion. Furthermore, Liao et al. (2018a,b) reported that because the t-phase is accompanied with high stress due to the fact that it is stabilized by high stress (as shown in Figure 8), its transformation will release stress, which will lead to stress relaxation and subsequent cracking, thus accelerating corrosion. Despite thorough studies on the t-ZrO2 to m-ZrO2 phase transformation, the role of alloying elements on t-ZrO2 fraction and stress requires further study to better understand the corrosion mechanism and the cause of oxide kinetic transition of Zr alloys.

4.2 Hydrogen uptake degradation mechanism

4.2.1 Hydrogen uptake and transport

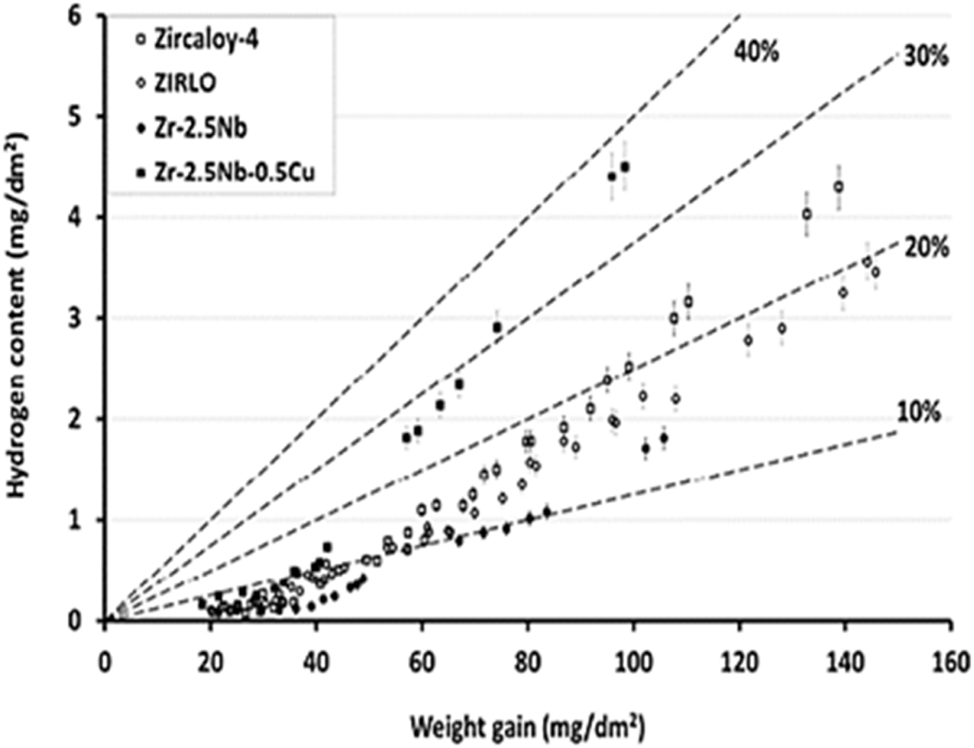

According to Motta et al. (2005, 2015) and Kautz et al. (2023), the hydrogen source of most concern is the hydrogen entering the Zr cladding during corrosion, as shown in Equation (1). Although other sources of hydrogen exist (e.g., hydrogen-water chemistry), mainly hydrogen generated by the corrosion reaction is susceptible to entering the Zr cladding (Motta et al. 2015). Thus, the total hydrogen uptake fraction (

Using Equation (2) above, it has been previously reported that the

Hydrogen content vs. corrosion weight gain during autoclave testing of various alloys in pure water at 360 °C. Adapted from (Couet et al. 2014).

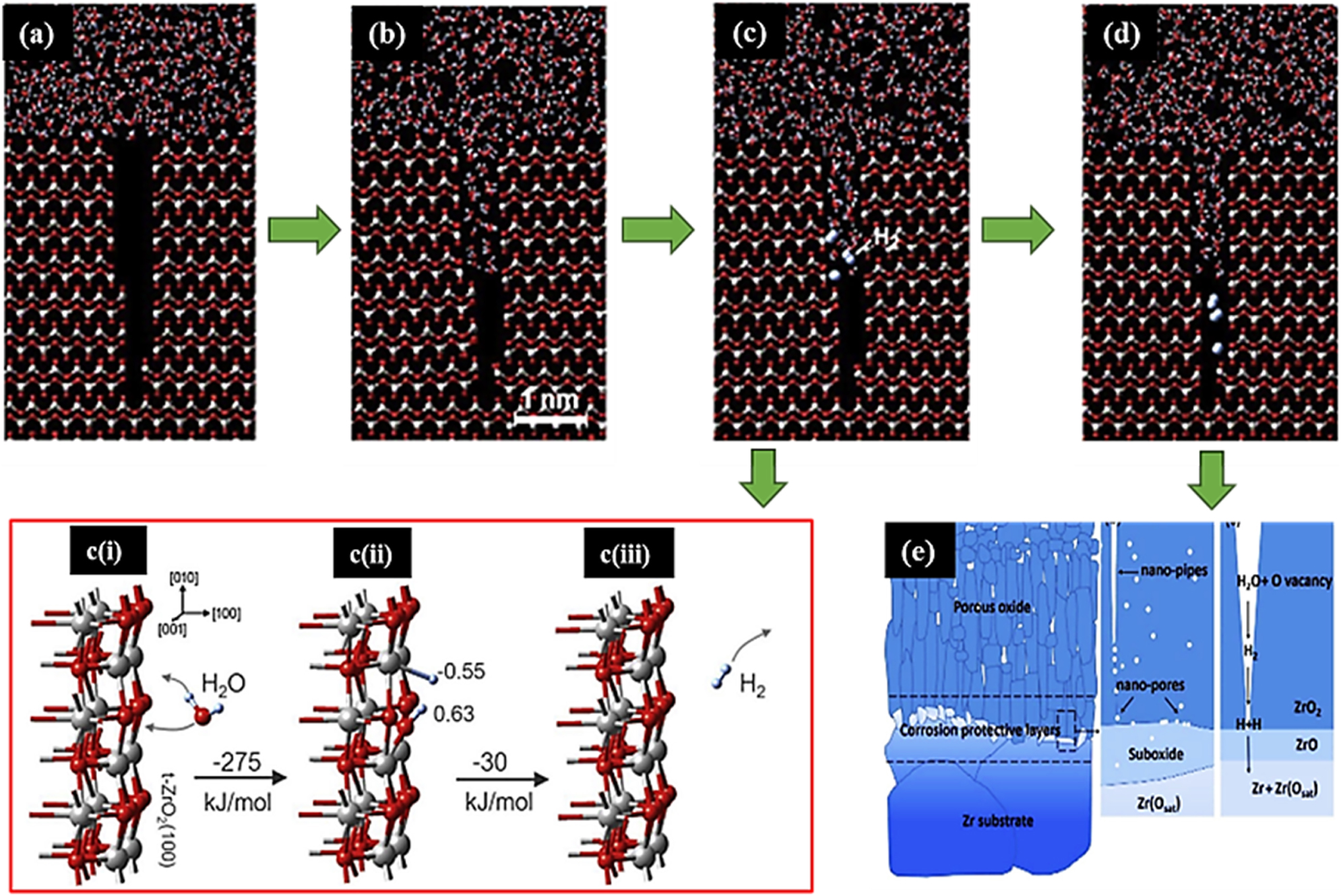

Several mechanisms have been proposed regarding the transport mechanism of hydrogen through the oxide layer to the Zr alloys; however, the mechanism proposed by Hu.et al. (2019) will be the focus herein. According to Hu.et al. (2019), during corrosion, water molecule migrates through pores into the oxide (shown in Figure 10a and b), where they react with vacancies in the side walls of the pores to produce H2 molecule, as presented in the simulation result in Figure 10c (Hu.et al. 2019). Detail of the reaction of water molecules with oxygen vacancies on the surface of ZrO2 is presented in Figure 10c(i)–(iii). The sequence of reactions is that, initially, the water molecule approaches an oxygen vacant site on the ZrO2 surface, as shown in Figure 10c(i). Thereafter, with a release of 275 kJ/mol of energy, the water molecule is chemisorbed and dissociated, as shown in Figure 10c(ii). The oxygen atom fills the vacancy, while one hydrogen atom remains attached to O and the other H atom binds to Zr (Figure 10c(ii)). Finally, the formation and desorption of H2 molecule occurs and is accompanied with a significant exothermic reaction, as shown in Figure 10c(iii). After the H2 molecule is produced, the H2 molecule diffuses through nano-pipes and nano-pores (as shown in Figure 10d), which are less than 0.5 nm in diameter, until they reach the suboxide (ZrO and Zr3O).

The mechanism of hydrogen transport through the oxide layer of Zr alloy proposed by Hu et al. (2019). Adapted from (Hu et al. 2019).

At the suboxide/ZrO2 interface, the hydrogen molecule dissociates and hydrogen atoms are chemisorbed and incorporated into the suboxide lattice, as presented in the schematics in Figure 10e. Although the hydrogen atoms incorporate into the suboxide, some authors have reported that there are barriers that inhibit the free migration of H from the surface to interior of the suboxide, and that these barriers vary between suboxide phases (Hu et al. 2019; Kautz et al. 2023). In addition, it has been previously reported that in regions of tensile strain in the oxide, the diffusion barrier decreases.

In respect to the driving force for hydrogen transport mechanism, recent studies have shown that the driving force for hydrogen uptake is inversely related to the electronic conductivity of the protective oxide (Couet et al. 2014, 2015a). This means that if the oxide electronic conductivity is not sufficiently high, hydrogen can migrate through the protective oxide layer to recombine with electrons and be absorbed into the metal (Couet et al. 2014, 2015a). However, to date, the transport mechanism of hydrogen through the oxide layer in response to driving force is still unclear, even though there is a belief that hydrogen travels through the protective oxide as H+ on the way to entering the Zr (Tupin et al. 2017; Veshchunov and Berdyshev 1998). Subsequently, the migration of hydrogen picked up by the metal into its matrix is dependent on temperature, concentration, and stress gradient (Motta et al. 2015). The oxide film conductivity of Zr alloys can be influenced by factors such as alloying elements and their incorporation into the oxide. Hence, the chemical state of alloying elements presents in the oxide layer, such as Sn, Nb, Cr, and Fe (depending on the alloy), is also an important consideration for developing a mechanistic understanding of hydrogen transport. Overall, the migration of these hydrogens into the metal leads to the formation of hydride phases, which causes severe degradation of Zr alloys in terms of mechanical properties, and significantly increases their corrosion rate (Hu et al. 2019; Motta et al. 2015).

5 Alloying elements role in Zr alloy corrosion behavior

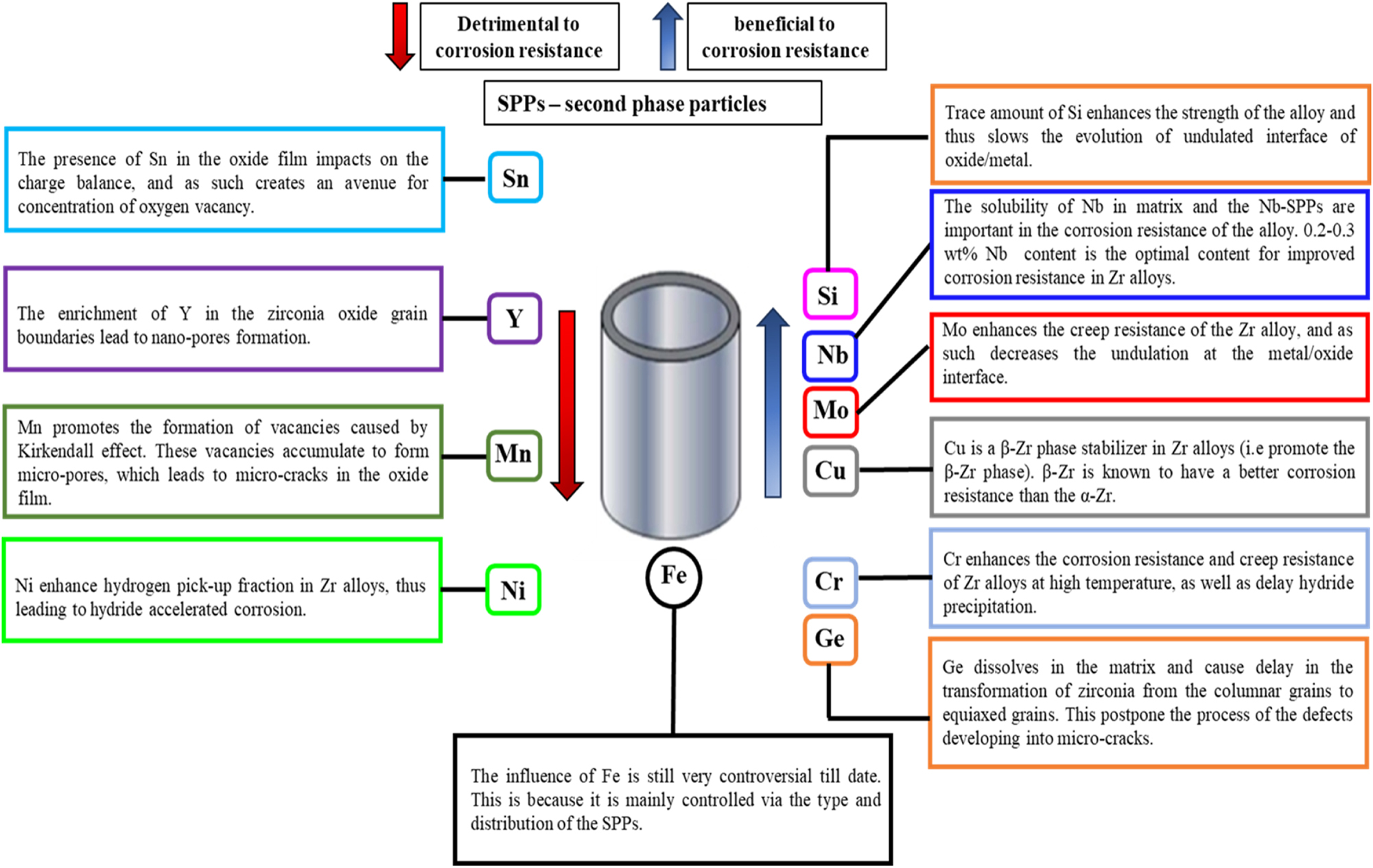

The intrinsic properties of Zr alloys depend primarily on their chemical composition (Chang and Hong 2008; Chen et al. 2015; Chun et al. 1999; Lee et al. 2001). Thus, alloying elements, their concentrations, and the presence of second phase precipitates (SPPs) will certainly play a crucial role in the corrosion behavior of Zr alloys. Retrospectively, many researchers have studied the effects of alloying elements on the corrosion behavior of Zr alloys, which will be discussed in this section. As mentioned earlier in Section 3, the major alloying elements in Zr alloys other than Zr are Sn and Nb; however, some minor alloying elements are added for different target reasons in the development and advancement of Zr alloys and include Y, Fe, Cr, Ni, Si, Mn, Cu, Mo, and Ge. The effects of these alloying elements (either beneficial or detrimental) on Zr alloys are discussed in the subsequent subsections and schematically represented in Figure 11.

Schematics showing the effect of alloying elements and mechanism of action in Zr alloys.

5.1 Alloying elements detrimental to the corrosion performance of Zr alloys

As shown on the left side in Figure 11, alloying elements such as Sn, Y, Ni, and Mn are detrimental to the corrosion performance of Zr alloys. The mechanism of action of these alloying elements is discussed hereafter.

5.1.1 Effect of Sn

During the oxidation of Zr alloy containing Sn, Sn oxidizes alongside with the Zr metal and is found in the formed oxide. However, the oxidation state of Sn can impact the charge balance and the concentration of oxygen vacancies in the formed oxides, which are important in the migration of diffusing species that control the oxidation and hydriding processes in Zr alloys (Kautz et al. 2023). The mechanism of charge imbalance and oxygen vacancy concentration arises from the similarities in the atomic radii of Zr and Sn (with a very slim difference of 2–3 pm), which allows for the substitution of Zr with Sn in the metal and oxide lattices. This mechanism postulates that if Sn is in the charge state of Sn2+ in the oxide, and substitutes for Zr4+, an addition of O2− vacancy would be required to maintain charge neutrality in the oxide. Thus, increasing the concentration of oxygen vacancies invariably leads to defects in the oxide. But if Sn is in the charge state of Sn4+, no oxygen vacancy would be required to maintain charge neutrality (Bell et al. 2015; Kautz et al. 2023). At this state, no harm is brought on the oxide film even with Sn presence. Since both Sn states are observed to be present in the oxides of Zr alloys containing Sn (Bell et al. 2015; Kautz et al. 2023); thus, Sn becomes detrimental to the corrosion performance of the Zr alloy owing to increased concentration of defects in the generated oxide film.

Another perspective to the effect of Sn was pointed out by Wei et al. (2013), who systematically examined the effect of Sn on corrosion mechanism of Zr–Sn–Nb alloys corroded at 360 °C/18 MPa in simulated primary water. The study hypothesized that Sn can stabilize the t-ZrO2 phase, thus reducing the pretransition time of the corroding alloy. This means a decrease in corrosion performance with Sn addition. Garner et al. (2014b) interpreted this hypothesis in terms of microtexture of the oxide formed. According to their finding, Sn-free Zr alloy showed remarkable reduction in oxide thickness and level of hydrogen pickup, as compared to the Sn-containing Zr alloy. From the microtexture and grain misorientation analyses of the oxide film, it was observed that the improved corrosion performance and reduction in hydrogen pickup of the Sn-free Zr alloy was related to the increased oxide texture strength, which resulted in longer, more aligned, and more protective columnar grain growth. This resulted in a reduced t-ZrO2 phase in the Sn-free Zr alloy, as compared to the Sn-containing Zr alloy.

5.1.2 Effect of Y

Yttrium in its ionic form, Y3+, has been observed to have a large diffusion coefficient in ZrO2 than Zr4+ (Chen et al. 2018), thus triggering the Kirkendall effect. The Kirkendall effect on the other hand results in nanoscale porosities in the formed oxide, thereby leading to crack defects in the oxide formed on the Y-containing Zr alloy.

5.1.3 Effect of Ni

The presence of Ni in Zr alloys is known to enhance hydrogen pick-up fraction, which makes it detrimental to their corrosion performance due to hydride accelerated corrosion (Garde et al. 1991; Than et al. 2020).

5.1.4 Effect of Mn

Similar to the Y effect, Mn promotes the formation of oxygen vacancies triggered by the Kirkendall effect (Shi et al. 2019). These vacancies accumulate to form micropores, causing microcracks and disrupting the integrity of the oxide formed, thus making the element Mn detrimental to the corrosion resistance of its containing Zr alloy.

5.2 Alloying elements beneficial to the corrosion performance of Zr alloys

As shown on the right side in Figure 11, some alloying elements such as Si, Nb, Cr, Mo, Cu, and Ge are beneficial to the corrosion performance of Zr alloys. The mechanism of action of these alloying elements is discussed hereafter.

5.2.1 Effect of Nb

The effect of Nb largely depends on its concentration in Zr alloys. Nb at a minimum concentration of 0.2–0.3 wt% is beneficial to the corrosion performance of its containing Zr alloy (Kautz et al. 2023; Kim et al. 2008). Nb improves the corrosion resistance of Zr alloy by inhibiting the inward diffusion of O2− from the surrounding environment and reduces the risk of hydrogen embrittlement (Jiang et al. 2022).

5.2.2 Effect of Si

Studies have shown that Si inclusion is beneficial to Zr alloys (Chen et al. 2015; Jin et al. 2012). This is because trace amounts of Si enhance the strength of alloy, which slows down the evolution of the undulated interface between the oxide/metal matrix associated with the formation of cracks in the oxide. In addition, Si having an oxidation valency of +4 helps to maintain the local electrical neutrality in oxides when Si substitutes Zr. Thus, oxygen vacancies are not produced according to the Hauffer Wagner Theory (Jin et al. 2012).

5.2.3 Effect of Cr

Chromium addition in several studies have shown to be beneficial to Zr alloys by enhancing their corrosion resistance and creep resistance at high temperature, as well as delay hydride precipitation (Christensen et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2015). In regards to the creep resistance, Jung et al. (2010) pointed out that the strengthening effect (creep resistance) of Cr is considered to be efficient when the Zr alloy contains Nb as an alloying element.

5.2.4 Effect of Mo, Cu, and Ge

These three elements are all beneficial to the corrosion performance of Zr alloys. Mo is beneficial by enhancing the creep resistance of its containing Zr alloy and, therefore, decreases the undulation at the oxide/metal interface. This invariably improves the alloy corrosion resistance. However, based on some previous studies, it is recommended to limit its addition to 0.1 wt% (Likhanskii and Kolesnik 2014; Motta et al. 2015). Cu is beneficial by acting as a β-Zr phase stabilizer in Zr alloys (i.e., promote the β-Zr phase) (Hong et al. 2001). The β-Zr phase is known to have better corrosion resistance than the α-Zr phase (Hong et al. 2001). However, the optimum Cu content for improving corrosion resistance in Zr alloy is within the range of 0.1–0.3 wt% (Hong et al. 2001). As for Ge, it dissolves in the matrix and cause delay in ZrO2 phase transformation. Thus, postponing the process of the defects developing into microcracks in the oxide during phase transformation (Chen et al. 2015, 2018).

5.3 Alloying element with unresolved effect on the corrosion performance of Zr alloys

5.3.1 Effect of Fe

As presented in Figure 11, the influence of Fe is still very controversial to date. This is because it is mainly controlled via the type and distribution of the second phase particles (SPPs). Currently, there are three school of thoughts on the role of Fe in the corrosion performance of Fe-containing Zr alloys. First is that, Fe is beneficial to the corrosion resistance of Zr alloys. According to Kaczorowski et al. (2014), addition of Fe from 273–1,330 ppm remarkably improved the corrosion resistance of Zr alloy in a lithium-bearing environment by delaying the kinetic acceleration (i.e., transition stage). Second, is the school of thought that Fe content has no significant effect on the corrosion behavior of Zr alloys. In a recent study (Kaczorowski et al. 2014), the authors investigated the in-pile corrosion of M5™ fuel rods containing Fe content of 1,000 ppm (M5™ – Fe) and correlated their results with the global PWR corrosion exposure of M5™ fuel rods. Their findings showed that the uniform corrosion performance of Fe containing Zr alloy is unaffected by the Fe content. Additionally, they pointed out through autoclave test that the Fe content in the M5™ fuel rods has no effect on its corrosion behavior on exposure to 360 °C simulated primary water and steam environment of 400–415 °C. The third school of thought is that Fe in Zr alloy is detrimental to the alloy’s corrosion performance. For instance, Shi et al. (2019) noticed that the delayed oxidation of Fe SPPs is one of the mechanisms responsible for crack formation in the ZrO2 oxide formed during their study. They noted that the delayed oxidation of Fe SPP will lead to incorporation of the SPP in an unoxidized form in the ZrO2, thus making the volume of the SPP to remain unchanged. As a consequence, the oxide around the SPPs will dilate because of the high BP ratio (1.56 for Zr/ZrO2). The dilation of the oxide will cause its expansion outward because the compressive stress decreases toward the outer oxide surface, which leads to microcracks being formed above the SPPs. Consequently, the formation and connection of these microcracks results in the degradation of the oxide, which in turn leads to a shift in the oxidation kinetics of the Zr alloy (Ni et al. 2011a).

The controversy over the effect of Fe on the corrosion behavior of Fe-containing Zr alloys raises a number of unresolved questions that are seeking attention, which are what is the dissolution mechanism of Fe in Zr alloy oxides and does Fe content affect the transition time as well as the mechanism of the oxidation kinetics of Zr alloys? Thus, it is critical that future studies are conducted to address these scientific questions.

6 Future prospects and concluding remarks

6.1 Future prospects

The development and degradation mechanism of Zr alloys in the nuclear environment is arguably one of the most carefully investigated corrosion processes over the last seven decades. This is because the degradation of Zr alloys in the nuclear environment remains a limiting factor for the upscaling of nuclear fuel operations to high burnups and more extreme conditions required for increased demand for green energy. Consequently, there has been a considerable improvement in the corrosion performance of the advanced Zr alloys relative to the traditional alloys. Over time, mechanistic understanding of the two main degradation mechanisms discussed in this article (corrosion and hydrogen uptake) continues to be developed, with significant progress made in understanding the connections between alloy composition, microstructure, oxide structure, corrosion behavior, and hydrogen uptake mechanism. Notwithstanding, there is still a great deal of work to be done to address several yet unanswered scientific questions related to the development and degradation of Zr alloy. Here is a summary of some of these scientific questions that require future research, cross-referenced to additional discussion elsewhere in this article.

The unclear mechanism of how the several proposed explanations to understand the enhanced in-reactor corrosion of Zr alloy, such as the effect of dissolution of SPP leading to change in microstructure, influence from the formation of a hydride rim, radiation enhancement from neutron or gamma flux, etc., needs to be further investigated.

It is important to further investigate on the current debate as to the exact location of the cathodic site in Zr alloy oxidation, where H+ is reduced. This will provide scientific answers to the uncertainty of the cathodic site being at either the oxide/water interface or within the oxide or even at both locations. Likewise, it is pertinent to clarify the transport mechanism of hydrogen through the oxide layer in response to driving force.

Previously, it has been established that different Zr alloys have different levels of strain accommodation, resulting in different stress accumulation and transition times; however, no in-depth or defined mechanism for such differentiation caused by alloy composition has been provided to date.

The controversy on the effect of Fe on the corrosion behavior of Fe containing Zr alloys needs to be addressed with more advanced and sophisticated experimental tools like XANES, synchrotron-XRD, TEM, and so on, especially in situ studies, which can provide direct visualization at time scales not possible with ex situ studies.

Overall, with the increasing use of machine learning or artificial intelligence in the material science domain, it may be possible to leverage on the advancement in this fast-growing field to explore trends and information in existing datasets. The application of machine learning may be useful in the context of Zr alloy corrosion for building a predictive capability linking microstructure features such as porosity, crack morphology, oxidation state of alloying elements, and oxide grain orientation and structure to corrosion parameters such as environment, exposure time, and temperature, or properties (e.g., thermal conductivity). Additionally, machine learning can be used in exploring the high dimensional alloy chemistry and process design space for development of new Zr alloy claddings with improved properties.

6.2 Concluding remarks

Over the years, there has been some extensive research focused on addressing germane scientific issues related to the development, application, and degradation of Zr alloys. These research efforts have led to the creation of modern Zr alloys that show appreciable improvement in corrosion performance relative to conventional alloys. The mechanistic understanding of the corrosion process is still evolving, but considerable progress has been made in understanding the interaction between alloy chemistry and microstructure, oxide structure, and corrosion behavior, as discussed critically in this article.

In this present work, we expanded on previously identified and addressed scientific questions related to the development, application, and degradation of Zr alloy and discussed recent research findings and efforts to develop fundamental understanding of the role of precipitates in the corrosion process, the role of oxide microstructure and alloy chemistry in reducing hydrogen uptake and corrosion in-service, and the exact nature of the stress accumulation processes. Although a great deal of work has been done, some unclear mechanisms and unresolved questions that still require further research have been identified in this work, and possible ways to resolving these questions have been proposed, such as the use of a combination of machine learning approach and high resolution/advanced techniques.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. BOO: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing-original draft. ZL, LL, JW, E-HH: writing-reviewing and editing.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Not applicable. None of these tools was used in preparing this manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

Abriata, J.P., Garces, J., and Versaci, R. (1986). The Zr-O (zirconium-oxygen) system. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 7: 116–124, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02881546.Suche in Google Scholar

Annand, K.J., MacLaren, I., and Gass, M. (2015). Utilizing dual EELS to probe the nanoscale mechanisms of the corrosion of Zircaloy-4 in 350°C pressurized water. J. Nucl. Mater. 465: 390–399, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2015.06.022.Suche in Google Scholar

Arima, T., Moriyama, K., Gaja, N., Furuya, H., Idemitsu, K., and Inagaki, Y. (1998). Oxidation kinetics of Zircaloy-2 between 450°C and 600°C in oxidizing atmosphere. J. Nucl. Mater. 257: 67–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3115(98)00069-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Bechade, J.L., Brenner, R., Goudeau, P., and Gailhanou, M. (2002). Influence of temperature on X-ray diffraction analysis of ZrO2 oxide layers formed on zirconium-based alloys using a synchrotron radiation. Mater. Sci. Forum 404: 803–808, https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/msf.404-407.803.Suche in Google Scholar

Bell, B.D.C., Murphy, S.T., Burr, P.A., Grimes, R.W., and Wenman, M.R. (2015). Accommodation of tin in tetragonal ZrO2. J. Appl. Phys. 117: 084901, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4909505.Suche in Google Scholar

Bouvier, P., Godlewski, J., and Lucazeau, G. (2002). A Raman study of the nanocrystallite size effect on the pressure-temperature phase diagram of zirconia grown by zirconium-based alloys oxidation. J. Nucl. Mater. 300: 118e126, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3115(01)00756-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Buscail, H., Rolland, R., Issartel, C., Perrier, S., and Latu-Romain, L. (2018). Stress determination by in situ X-ray diffraction – influence of water vapour on the Zircaloy-4 oxidation at high temperature. Corros. Sci. 134: 38–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.02.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Chang, K.I. and Hong, S.I. (2008). Effect of sulphur on the strengthening of a Zr–Nb alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 373: 16–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2007.04.045.Suche in Google Scholar

Chang, W. (2003). Zirconium products: technical data sheet. Allegheny Technologies Inc., Pittsburgh.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, L., Li, J., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L.-C., Lua, W., Zhang, L., Wang, L., and Zhang, D. (2015). Effects of alloyed Si on the autoclave corrosion performance and periodic corrosion kinetics in Zr–Sn–Nb–Fe–O alloys. Corros. Sci. 100: 651–662, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.08.043.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, L., Shen, P., Zhang, L., Lu, S., Chai, L., Yang, Z., and Zhang, L. (2018). Corrosion behavior of non-equilibrium Zr-Sn-Nb-Fe-Cu-O alloys in high temperature 0.01 M LiOH aqueous solution and degradation of the surface oxide films. Corros. Sci. 136: 221–230, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.03.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Christensen, M., Wolf, W., Freeman, C., Wimmer, E., Adamson, R.B., Hallstadius, L., Cantonwine, P.E., and Mader, E.V. (2013). Effect of alloying elements on the properties of Zr and the Zr-H system. J. Nucl. Mater. 445: 241–250, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.10.040.Suche in Google Scholar

Chun, Y.B., Hwang, S.K., Kwun, S.I., and Kim, M.H. (1999). Abnormal grain growth of Zr-1 wt.% Nb alloy and the effect of Mo addition. Scr. Mater. 40: 1165–1170, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1359-6462(99)00018-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Couet, A., Motta, A.T., Comstock, R.J., and Paul, R.L. (2012). Cold neutron prompt gamma activation analysis, a non-destructive technique for hydrogen level assessment in zirconium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 425: 211–217, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2011.06.044.Suche in Google Scholar

Couet, A., Motta, A.T., and Comstock, R.J. (2014). Hydrogen pickup measurements in zirconium alloys: relation to oxidation kinetics. J. Nucl. Mater. 451: 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2014.03.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Couet, A., Motta, A., and Comstock, R. (2015a). Effect of alloying elements on hydrogen pickup in zirconium alloys. In: Zirconium in the nuclear industry, 17. ASTM Int, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India.10.1520/STP154320120215Suche in Google Scholar

Couet, A., Motta, A.T., and Ambard, A. (2015b). The coupled current charge compensation model for zirconium alloy fuel cladding oxidation: I. Parabolic oxidation of zirconium alloys. Corros. Sci. 100: 73–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.07.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Cox, B. (1968). Effect of irradiation on the oxidation of zirconium alloys in high temperature aqueous environments: a review. J. Nucl. Mater. 28: 1–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3115(68)90055-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Cox, B. (2005). Some thoughts on the mechanisms of in-reactor corrosion of zirconium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 336: 331–368, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2004.09.029.Suche in Google Scholar

Cox, B. and Pemsler, J.P. (1968). Diffusion of oxygen in growing zirconia films. J. Nucl. Mater. 28: 73–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3115(68)90058-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Daum, R.S., Majumdar, S., and Billone, M.C. (2003). Mechanical properties of irradiated Zircaloy-4 for dry cask storage conditions and accidents. In: Nuclear safety research conference 2003, Washington, D.C., pp. 85–96.Suche in Google Scholar

Dong, Y., Motta, A.T., and Marquis, E.A. (2013). Atom probe tomography study of alloying element distributions in Zr alloys and their oxides. J. Nucl. Mater. 442: 270–281, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.08.055.Suche in Google Scholar

Efaw, C.M., Vandegrift, J.L., Reynolds, M., Jaques, B.J., Hu, H., Xiong, H., and Hurley, M.F. (2020). Characterization of zirconium oxides part II: new insights on the growth of zirconia revealed through complementary high-resolution mapping techniques. Corros. Sci. 167: 108491, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2020.108491.Suche in Google Scholar

Ensor, B., Spengler, D.J., Seidensticker, J.R., Bajaj, R., Cai, Z., and Motta, A.T. (2019a). Microbeam synchrotron radiation diffraction and fluorescence of oxide layers formed on zirconium alloys at different corrosion temperatures. J. Nucl. Mater. 526: 151779, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2019.151779.Suche in Google Scholar

Ensor, B., Lucadamo, G., Seidensticker, J.R., Bajaj, R., Cai, Z., and Motta, A.T. (2019b). Characterization of long-term, in-reactor Zircaloy-4 corrosion coupons and the impact of flux, fluence, and temperature on oxide growth, stress development, phase formation, and grain size. In: 19th International symposium of zirconium in the nuclear industry. ASTM International, STP 1622. pp. 588–619.10.1520/STP162220190038Suche in Google Scholar

Fromhold, A.T. (1978). Distribution of charge and potential through oxide films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 125: C118–C128.Suche in Google Scholar

Fromhold, A.T. (1979). Easy insight into space-charge effects on steady-state transport in oxide films. Oxid.Met. 13: 475–479, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00605111.Suche in Google Scholar

Fuketa, T., Nagase, F., Ishijima, K., and Fujishiro, T. (1996). NSRRRIA experiments with high burnup PWR fuels. Nucl. Saf. 37: 328–342.10.2172/269705Suche in Google Scholar

Garde, A.M. (1991). Enhancement of aqueous corrosion of Zircaloy-4 due to hydride precipitation at the metal-oxide interface, In: +Zirconium in the nuclear industry: ninth international symposium. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, ASTM STP 1132, pp. 566–594.10.1520/STP25527SSuche in Google Scholar

Garde, A.M., Slagle, H., and Mitchell, D. (2009). Hydrogen pick-up fraction for ZIRLO cladding corrosion and resulting impact on the cladding integrity. In: Proceedings of international conference on light water reactor fuel performance (Top Fuel 2009), Pap. 2136. ANS, La Grange Park, IL.Suche in Google Scholar

Garner, A., Preuss, M., and Frankel, P. (2014a). A method for accurate texture determination of thin oxide films by glancing-angle laboratory X-ray diffraction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 47: 575–583, https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600576714000569.Suche in Google Scholar

Garner, A., Gholinia, A., Frankel, P., Gass, M., MacLaren, I., and Preuss, M. (2014b). The microstructure and microtexture of zirconium oxide films studied by transmission electron backscatter diffraction and automated crystal orientation mapping with transmission electron microscopy. Acta Mater. 80: 159–171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2014.07.062.Suche in Google Scholar

Garner, A., Hu, J., Harte, A., Frankel, P., Grovenor, C., Lozano-Perez, S., and Preuss, M. (2015). The effect of Sn concentration on oxide texture and microstructure formation in zirconium alloys. Acta Mater. 99: 259–272, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2015.08.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Gabory, B.D. and Motta, A.T. (2013). Structure of Zircaloy 4 oxides formed during autoclave corrosion. In: Light water reactor fuel performance meeting (Top Fuel 2013), Pap. 8584. ANS, La Grange Park, IL, pp. 4–12.Suche in Google Scholar

Gabory, B.D., Motta, A.T., and Wang, K. (2015). Transmission electron microscopy characterization of Zircaloy-4 and ZIRLOTM oxide layers. J. Nucl. Mater. 456: 272–280.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2014.09.073Suche in Google Scholar

Gass, M., Fenwick, M., Hulme, H., Waters, M., Binks, P., Panteli, A., Chatterton, M., Allen, V., and Cole-Baker, A. (2018). Corrosion of Zircaloys: relating the microstructural observations to the corrosion kinetics. J. Nucl. Mater. 509: 343–354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2018.07.017.Suche in Google Scholar

Goudeau, P., Faurie, D., Girault, B., Renault, P.O., Le Bourhis, E., Villain, P., Badawi, F., Castelnau, O., Brenner, R., Béchade, J.L., et al.. (2006). Strains, stresses and elastic properties in polycrystalline metallic thin films: in situ deformation combined with X-ray diffraction and simulation experiments. Mater. Sci. Forum 524: 735–740, https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/msf.524-525.735.Suche in Google Scholar

Harada, M. and Wakamatsu, R. (2008) The effect of hydrogen on the transition behavior of the corrosion rate of zirconium alloys, In: Zirconium in the nuclear industry: 15th international symposium. p. 384.10.1520/STP48146SSuche in Google Scholar

Hillner, E. (1977). Corrosion of zirconium-base alloys: an overview. In: Zirconium in the nuclear industry. ASTM Int, West Conshohocken, USA.10.1520/STP35573SSuche in Google Scholar

Hong, H.S., Moon, J.S., Kim, S.J., and Lee, K.S. (2001). Investigation on the oxidation characteristics of copper-added modified Zircaloy-4 alloys in pressurized water at 360°C. J. Nucl. Mater. 297: 113–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3115(01)00601-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Hu, J., Liu, J., Lozano-Perez, S., Grovenor, C.R.M., Christensen, M., Wolf, W., Wimmer, E., and Mader, E.V. (2019). Hydrogen pickup during oxidation in aqueous environments: the role of nano-pores and nano-pipes in zirconium oxide films. Acta Mater. 180: 105–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2019.09.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Hudson, D., Cerezo, A., and Smith, G.D.W. (2009). Zirconium oxidation on the atomic scale. Ultramicroscopy 109: 667–671, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultramic.2008.10.020.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Hume-Rothery, W., Smallman, R.E., and Howarth, C.W. (1969). The structure of metals and alloys, 5th. The Institute of Metals, London.Suche in Google Scholar

Ibrahim, E.F. and Cheadle, B.A. (1985). Development of zirconium alloys for pressure tubes in CANDU reactors. Can. Metall. Q. 24: 273–281, https://doi.org/10.1179/000844385795448533.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiang, G., Xu, D., Yang, W., Liu, L., Zhi, Y., and Yang, J. (2022). High-temperature corrosion of Zr–Nb alloy for nuclear structural materials. Progress Nucl. Energy 154: 104490, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2022.104490.Suche in Google Scholar

Jin, S., Leinenbach, C., Wang, J., Duarte, L.I., Delsante, S., Borzone, G., Scott, A., and Watson, A. (2012). Thermodynamic study and re-assessment of the Ge–Ni system. Calphad 38: 23–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.calphad.2012.03.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Jin, Z., Yang, Y., Zhang, Z., Ma, X., Lv, J., Wang, F., Ma, M., Zhang, X., and Liu, R. (2016). Effect of Hf substitution Cu on glass-forming ability, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of Ni-free Zr–Ti–Cu–Al bulk metallic glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 806: 668–675, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.07.240.Suche in Google Scholar

Jung, Y., Seol, Y., Choi, B., Park, J., and Jeong, Y. (2010). Effect of Cr on the creep properties of zirconium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 396: 303–306, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2009.10.058.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaczorowski, D., Mardon, J.P., Barberis, P., Hoffmann, P.B., and Stevens, J. (2014). Impact of iron in M5TM. In: Comstock, R. and Barberis, P. (Eds.). Zirconium in the nuclear industry: 17th international symposium, STP 1543, pp. 159–183.10.1520/STP154320120195Suche in Google Scholar

Kalavathi, V. and Bhuyan, R.K. (2019). A detailed study on zirconium and its applications in manufacturing process with combinations of other metals, oxides and alloys: a review. In: Mater. today: proceedings. Vol. 19, pp. 781–786.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.08.130Suche in Google Scholar

Kammenzind, B.F., Gruber, J.A., Bajaj, R., and Smee, J.D. (2018). Neutron irradiation effects on the corrosion of Zircaloy-4 in a pressurized water reactor environment. Zirconium in the Nuclear Industry: 18th International Symposium, STP159720160085. ASTM Int, pp. 1318 https://doi.org/10.1520/stp159720160085.Suche in Google Scholar

Kass, S. (1960). Hydrogen pickup in various zirconium alloys during corrosion exposure in high-temperature water and steam. J. Electrochem. Soc. 107: 594–597, https://doi.org/10.1149/1.2427781.Suche in Google Scholar

Kass, S. (1964). The development of the zircaloys. Corrosion of zirconium alloys. ASTM Int, West Conshohocken, USA.10.1520/STP47070SSuche in Google Scholar

Kass, S. and Kirk, W.W. (1962). Corrosion and hydrogen absorption properties of nickel-free Zircaloy-2 and Zircaloy-4. ASM Trans. Q. 55: 77–100.Suche in Google Scholar

Kautz, E., Gwalani, B., Yu, Z., Varga, T., Geelhood, K., Devaraj, A., and Senor, D. (2023). Investigating zirconium alloy corrosion with advanced experimental techniques: a review. J. Nucl. Mater. 585: 154586, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2023.154586.Suche in Google Scholar

Khan, M.A., Williams, R.L., and Williams, D.F. (1999). Conjoint corrosion and wear in titanium alloys. Biomaterials 20: 765–772, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00229-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Kim, H.G., Park, S.Y., Lee, M.H., Jeong, Y.H., and Kim, S.D. (2008). Corrosion and microstructural characteristics of Zr-Nb alloys with different Nb contents. J. Nucl. Mater. 373: 429–432, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2007.05.035.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, T., Kim, J., Choi, K.J., Yoo, S.C., Kim, S., and Kim, J.H. (2015). Phase transformation of oxide film in zirconium alloy in high temperature hydrogenated water. Corros. Sci. 99: 134–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.06.034.Suche in Google Scholar

Kobayashi, E., Doi, H., and Yoneyama, T. (1995). Evaluation of mechanical properties of dental casting TiZr based alloys. J. Japanese Soc. Dental Mater. Devices 14: 321–327.Suche in Google Scholar

Kofstad, P. (1972). Nonstoichiometry, diffusion, and electrical conductivity in binary metal oxides. Mater. Corros. 25: 234–254.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, J.H., Hwang, S.K., Yasuda, K., and Kinoshita, C. (2001). Effect of molybdenum on electron radiation damage of Zr-base alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 289: 334–337, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3115(01)00435-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Leech, W.J. and Yueh, K. (2001). The fuel duty index, a method to assess fuel performance. In: Proceedings of international conference on light water reactor fuel performance (Top Fuel 2001). ANS, La Grange Park, IL, pp. 2–16.Suche in Google Scholar

Lemaignan, C. and Motta, A.T. (1994) Zirconium alloys in nuclear applications. In: Frost, B.R.T. (Ed.). Materials science and technology, Vol. 10B/II. VCH, Weinheim.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, H., Glavicic, H.M., and Szpunar, J.A. (2004). A model of texture formation in ZrO2 films. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 366: 164–174, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0921-5093(02)00787-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Liao, J., Yang, Z., Qiu, S., Peng, Q., Li, Z., and Zhang, J. (2018a). The correlation between tetragonal phase and the undulated metal/oxide interface in the oxide films of zirconium alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 524: 101–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2019.06.039.Suche in Google Scholar

Liao, J.J., Yang, Z.B., Qiu, S.Y., Peng, Q., Li, Z.C., Zhou, M.S., and Liu, H. (2018b). Corrosion of new zirconium claddings in 500 °C/10.3 MPa steam: effects of alloying and metallography. Acta Metall. Sin. 13: 1e14.10.1007/s40195-018-0857-7Suche in Google Scholar