Abstract

Sulfide often appears in circulating cooling water due to the presence of sulfate reducing bacteria and could affect corrosion behavior of cooling pipe metals such as stainless steel. Scanning Kelvin probe and scanning electrochemical microscope measurements, combined with electrochemical testing, were used to investigate the micro-electrochemical information of passive film and analyzed the influence of sulfide in simulated cooling water on corrosion resistance of stainless steel. Results showed that the presence of sulfide in water caused a negative shift in surface potential of stainless steel, an increase in surface potential difference, and an increase in local response current on the surface, resulting in a current peak that gradually increased over time. The analysis results of passive film composition showed that the presence of sulfide caused increase in the ratio of Fe/Cr and OH−/O2−, as well as the content of Cr(OH)3 and Fe(OH)3 in passive film, whereas caused a decrease of Cr2O3 content, and led to the formation of FeS2 in the passive film. These changes in the composition of the passive film made it easier for active sites to appear on the surface of stainless steel and enhanced the conductivity of the passive film and significantly reducing its protective performance.

1 Introduction

Stainless steel is commonly used as cooling tube material for condensers that use freshwater as cooling water. In such cooling water, a passive film can spontaneously form on the surface of stainless steel, which has excellent corrosion resistance. Researches have shown that the composition and temperature of the corrosive media, as well as the stress endured by stainless steel, are the main factors affecting corrosion resistance of stainless steel (Bellezze et al. 2018; Steensland 1968; Zheng and Zheng 2016), while the corrosion behavior of stainless steel in cooling water is mainly influenced by the media and temperature (Bellezze et al. 2018; Zheng and Zheng 2016). The corrosion resistance of stainless steel is closely related to the properties of the passive film formed on its surface, which determines the load-bearing capacity of the metal when corroded by harmful ions. Generally, the passive film on the surface of stainless steel in water is mainly composed of iron and chromium oxides (Abreu et al. 2004).

Sulfate-reducing bacteria are common corrosive microorganisms in circulating cooling water systems that can reduce sulfate to sulfide in water. Sulfide ions are considered one kind of the anions that can degrade the passive film of stainless steel cooling tubes (Zheng et al. 2013). Studies have been conducted on the corrosive behavior of stainless steel induced by sulfide. It is suggested that sulfide ions alter the composition, structure, and semiconductor properties of the passive film on stainless steel surface in water, thereby reducing its corrosion resistance (Ferreira et al. 2013). The impact of sulfide on corrosion of stainless steel is more pronounced than that of temperature (Senka et al. 2023). The influence of sulfide on the corrosion behavior of stainless steel is related to factors such as temperature, pH and composition of the water solution, sulfide concentration, and stress applied to the material. Elevated temperatures can enhance the adsorption of S species on the passive film, resulting in more sulfides in the passive film (Wang et al. 2020). In sodium chloride solution, it was found that the sulfide can improve the pitting corrosion resistance of 2205 DSS at a pH of 11.5, attributed to the competitive adsorption of sulfide ions and chloride ions on the metal surface. However, when the pH of the solution is 4–9, sulfide promotes pitting corrosion (Xiao et al. 2022). Low concentrations of sulfide (<0.1 mol/L) have been observed to inhibit pitting corrosion of 2205DSS in HCl solution, but high concentrations of sulfide (>0.137 mol/L) significantly promote corrosion, leading to intergranular corrosion and active dissolution of the metal surface (Tang et al. 2019). Researches have also found that sulfide has an impact on the stress corrosion cracking of stainless steel (Liu et al. 2009, 2015). The presence of sulfides in the solution promotes hydrogen evolution, increasing susceptibility to stress corrosion cracking. Not only sulfides in solution but also sulfide inclusions in stainless steel have been reported to profoundly affect its corrosion behavior, leading to pitting corrosion of the material (Rhode et al. 2013).

There have been many researches on the characteristics and passivation mechanisms of passive films on stainless steel in different environments (Lei et al. 2014; Maysam et al. 2016). Studies indicate that the corrosion resistance of stainless steel is primarily attributed to the passive film formed on the surface. The passive film consists of a nano-thick chromium-rich oxide inner layer and an iron oxide outer layer, and its performance depends on various factors such as the composition of stainless steel and electrolytes (Lee et al. 2016a).

In the past, researches on the corrosiveness of sulfide on stainless steel mainly adopt the methods of electrochemical testing and surface analysis. From the changes in passive film resistance, charge transfer resistance, anodic dissolution process caused by sulfide ions, combined with changes in passive film composition, the destructive effect of sulfide on the passive film of stainless steel is analyzed. Combining with micro-electrochemical techniques such as scanning Kelvin probes (Jiang et al. 2019) and scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) (Ye et al. 2018; Zhao et al. 2013), in situ analysis of the destructive effect of sulfide on passive film can help further understand the corrosiveness of sulfide from a microscopic perspective. However, research in this area is currently still limited.

In order to elucidate the corrosion mechanism of sulfide ions on stainless steel in water environment from a microscopic perspective, the microscopic electrochemical techniques and surface analysis were combined to investigate the relationship between the corrosion resistance of stainless steel in simulated water containing sulfide, the micro-electrochemical changes, and the composition of passive film in this paper.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental material and media

304 stainless steel (304SS) was used as the research material, with the main composition (mass %) as follows: 0.07 % C, 0.075 % Si, 1.11 % Mn, 18.09 % Cr, 7.94 % Ni, 0.060 % Co. A steel plate was initially cut into specimens with a working surface of 10 mm × 10 mm. A copper wire was welded to the back of the working surface, and epoxy resin was used to encapsulate all nonworking surfaces. Prior to each experiment, the working surfaces were polished with different grades of sandpaper (400–1,200 grit) and then degreased with alcohol and rinsed with deionized water. All experiments were conducted in simulated cooling water at a temperature of 45 °C. The composition of the simulated cooling water was provided in Table 1.

The composition of the simulated cooling water.

| Chemical substance | NaCl | NaHCO3 | Na2SO4 | MgSO4 | CaCl2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c (mmol/L) | 7.50 | 2.00 | 3.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 |

During the experimental process, the 304SS electrodes and coupons were initially immersed in simulated water for 5 d, and then different concentrations of sulfide were introduced in water. After 30 min, the electrochemical tests were conducted and the corrosion coupons were taken out for surface analysis.

2.2 Electrochemical measurement

Electrochemical measurements were conducted on an electrochemical workstation (CHI660D). A saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was employed as the reference, and a platinum electrode was served as the auxiliary. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed at open circuit potential (OCP) with a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz and an amplitude of 10 mV. The scan rate for polarization curve measurements was set at 1 mV/s. Mott–Schottky plot was carried out at a frequency of 1,000 Hz, with a potential range from 0.8 to −1.4 V, moving from high to low potential, and with a step size of 50 mV.

2.3 Microelectrochemical measurement

Microscopic electrochemical measurements utilized the microscopic electrochemical scanning system (M370 from AMETEK, USA) with a scanning Kelvin probe (SKP) to measure the relative work function difference on the electrode surface. The scanning probe, using a tungsten electrode with a diameter of 250 μm, was positioned at a distance of approximately 5 μm from the sample, with a vibration frequency of 80 Hz and a scanning rate of 500 μm/s. The testing was conducted using an x-y area scanning method, and the dimensions of the testing area were both 5 mm in length and width.

The corrosion behavior of stainless steel was also investigated by a scanning electrochemical microscope (SECM) in the M370 microscopic electrochemical scanning system. A Pt microelectrode with a radius of 5 μm was employed as auxiliary in the measurements, and K3[Fe(CN)6] was used as the experimental redox medium. The distance between the microelectrode tip and the surface of the working electrode was maintained at 5 μm, with a tip bias of +0.493 V versus Ag/AgCl/KCl (3.0 M). The scanning range was set at 30 μm × 30 μm, and the scanning speed was 10 μm/s. All the measurements were conducted at open-circuit potential.

2.4 XPS analysis

The composition of the passive film on stainless steel surface was analyzed by XPS (PHI5300). All XPS peaks were calibrated to the standard carbon C 1s binding energy (284.8 eV). XPS data analysis was performed by XPS PEAK 4.1 software.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Electrochemical measurement and analysis

3.1.1 EIS measurements and analysis

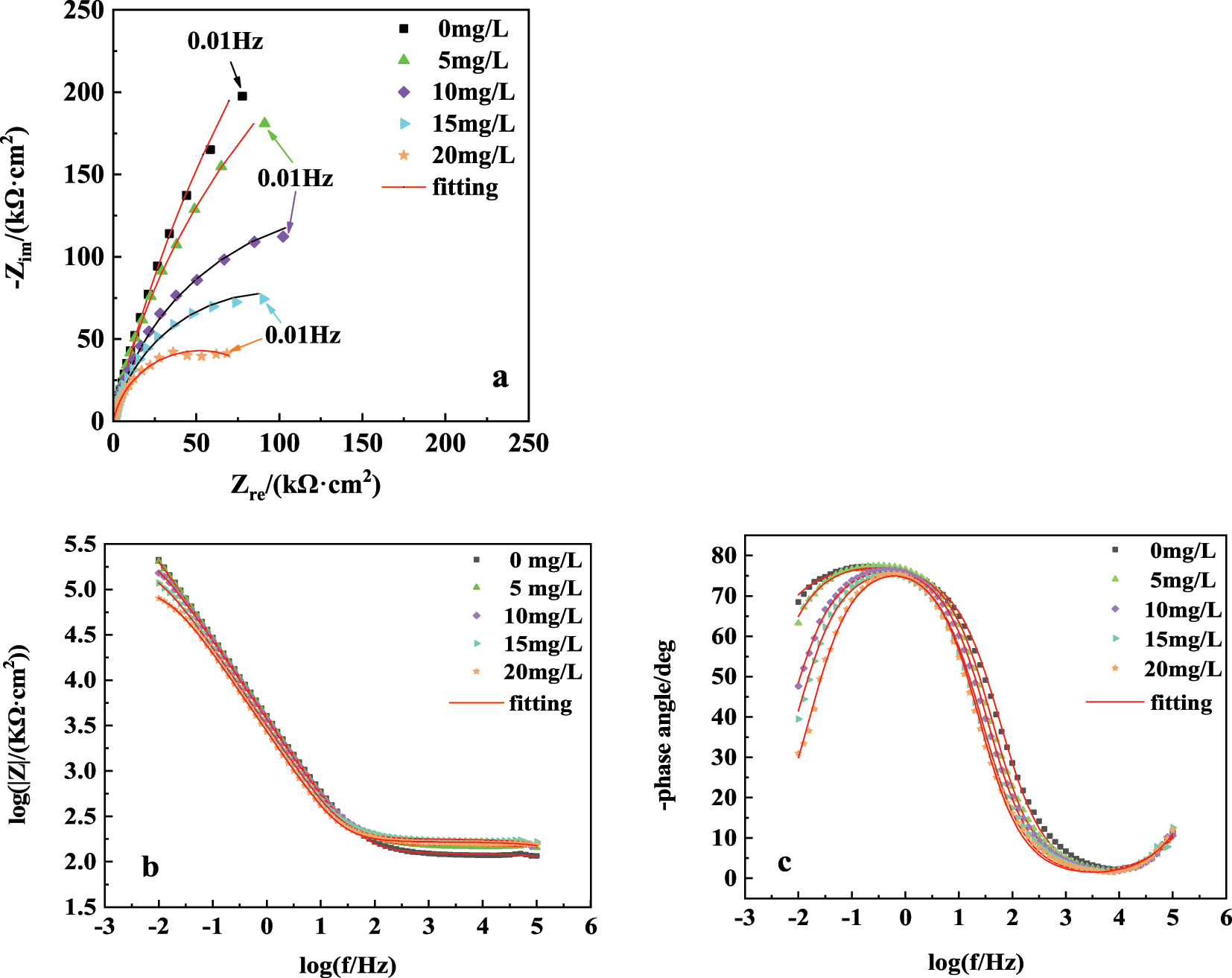

The 304SS electrode was initially immersed in simulated water for 5 days to allow the formation of a certain thickness of passive film on the surface. Subsequently, different concentrations of sulfide were introduced, and the electrochemical tests were conducted after 30 min. Firstly, the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was measured, and the results are shown in Figure 1. The results indicated that the impedance arc diameter of the stainless steel electrode is relatively large in simulated water without sulfide, indicating a higher reaction resistance of stainless steel. With the addition of sulfide, the diameter of the impedance arc decreased, indicating that the addition of sulfide reduces the corrosion resistance of stainless steel.

Nyquist and bode plots of 304SS electrode in simulated cooling water with five concentrations of sulfide.

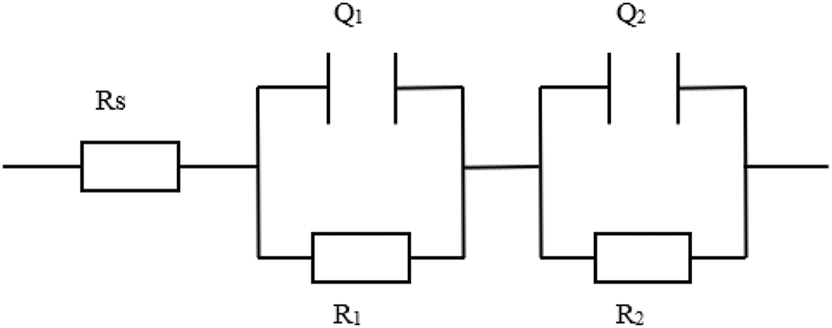

The equivalent circuit in Figure 2 (Barroux et al. 2021; Ge et al. 2003; Li et al. 2024; Liu et al. 2024) was used to fit the EIS data in Figure 1, where R1 and Q1 represent charge transfer resistance and double-layer capacitance, while R2 and Q2 represent film resistance and film capacitance of the stainless steel, respectively. The fitting results displayed in Table 2 reveal that sulfide mainly affect the film resistance (R2) value. Without the addition of sulfide, the film resistance R2 reached 7.3 MΩ cm2, indicating good protective performance of the passive film. After adding 5 mg/L sulfide, the film resistance R2 rapidly decreased to 0.3 MΩ cm2, and it continued to decrease with an increase in sulfide concentration. At the same time, the increase of Q1 and Q2 indicated that sulfide ions adsorbed on the electrode surface and deteriorated the passive film, enhanced the capacitance of electrode, leading to changes in the passive film performance (Ge et al. 2003). Table 2 also shows that in the presence of sulfide, the charge transfer resistance R1 of stainless steel decreased, while the double-layer capacitance Q1 increased, indicating a reduction in the electrochemical reaction resistance at the film/solution interface.

Equivalent circuit for fitting the EIS results.

The fitting results of the EIS in Figure 1.

| Sulfide concentration (mg/L) | Rs (Ω·cm2) | R1 (kΩ·cm2) | Q1 (μS⋅sncm−2) | n1 | R2 (kΩ·cm2) | Q2 (μS⋅sncm−2) | n2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 102.9 ± 2.5 | 2.75 ± 0.06 | 48.4 ± 1.1 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 7,300 ± 26 | 15.7 ± 0.5 | 0.88 ± 0.03 |

| 5 | 100.0 ± 1.8 | 1.83 ± 0.07 | 51.7 ± 1.2 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 300 ± 12 | 30.4 ± 0.9 | 0.84 ± 0.04 |

| 10 | 96.9 ± 1.9 | 1.77 ± 0.04 | 100.5 ± 1.0 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 190 ± 11 | 44.5 ± 0.7 | 0.87 ± 0.02 |

| 15 | 106.4 ± 2.2 | 1.69 ± 0.05 | 98.2 ± 1.6 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 150 ± 9 | 64.6 ± 0.6 | 0.85 ± 0.05 |

| 20 | 94.1 ± 2.3 | 1.64 ± 0.08 | 140.8 ± 1.2 | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 110 ± 6 | 73.0 ± 0.8 | 0.82 ± 0.02 |

3.1.2 Polarization curve measurements and analysis

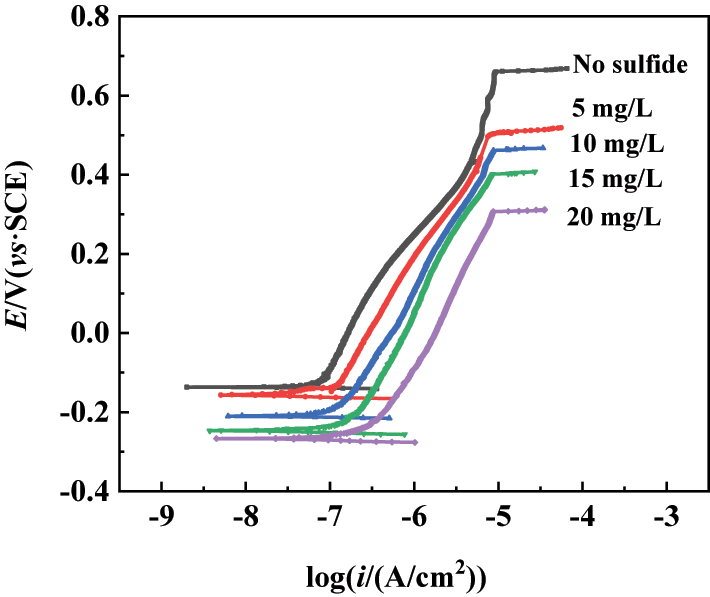

The polarization curves were measured for further analysis of the passive film performance of 304SS, and the results display in Figure 3. Curve 1 in Figure 3 represents the polarization curve of the 304SS electrode immersed in simulated cooling water for 5 days. It is evident that the corrosion potential and the pitting potential of stainless steel in the simulated cooling water were −0.12 V and 0.668 V, respectively, and the passive current density (i p) at the polarization potential of 0 V was 3.31 μA/cm2. The higher the concentration of sulfide, the more negative the corrosion potential and the pitting potential, and the greater the passive current density. When the added concentration of sulfide was 20 mg/L, the passive current density increased to 9.77 μA/cm2. This indicates that sulfide promoted the anodic dissolution of stainless steel, which is consistent with the results of many researchers (Cui et al. 2017; Ge et al. 2003; Luo et al. 2011). Marcus proposed that sulfide can weaken the binding force of metal–metal bonds on surface, leading to an increase in the anodic dissolution rate of the metal (Marcus 1998). In other words, the presence of sulfide reduces the activation energy of the metal dissolution reaction, accelerating the process of metal anodic dissolution. Additionally, with the increase of sulfide concentration, the pitting potential decreased significantly, which may be due to the prevention of the adsorption of OH− or O2− on the surface of stainless steel by sulfide, thereby hindering the regeneration of the passive film and changing its structure (Zhang et al. 2012). Compared with the short-term (1 h) experimental results in the literature (Ge et al. 2003), Figure 3 shows the results of sulfide damage on the surface of stainless steel with thicker passivation film after being passivated in water for 5 days. It shows that the negative shift of corrosion potential and the decrease of pitting potential were more significant, further indicating that the damage of the sulfide mainly changes the performance of the passivation film.

Polarization curves of the 304SS electrode in simulated cooling water containing five concentrations of sulfide.

3.1.3 Mott–Schottky analysis

It is found that the passive film on the surface of 304SS exhibits semiconductor characteristics (Schultze and Lohrengel 2000). The growth kinetics of this semiconductor film is related to the density and types of point defects; thus, the performance of the passive film is influenced by its electronic properties. The Mott–Schottky plots can be used to determine the semiconductor type of the passive film and estimate the carrier concentration in the film. The Mott–Schottky equation is expressed as follow:

where E fb represents the flat-band potential, e is the elementary charge (1.6 × 10−19 C), K is the Boltzmann constant (1.38 × 10−23 J/K), and T is the temperature. ε is the relative dielectric constant of the passive film, and ε 0 is the vacuum permittivity. N is the carrier concentration, which is denoted by NA (acceptor density) and ND (donor density) for p-type and n-type semiconductors, respectively, and can be calculated from the slope of the 1/Csc 2 and E plots. The linear slope for n-type semiconductor is positive, while that for p-type semiconductor is negative.

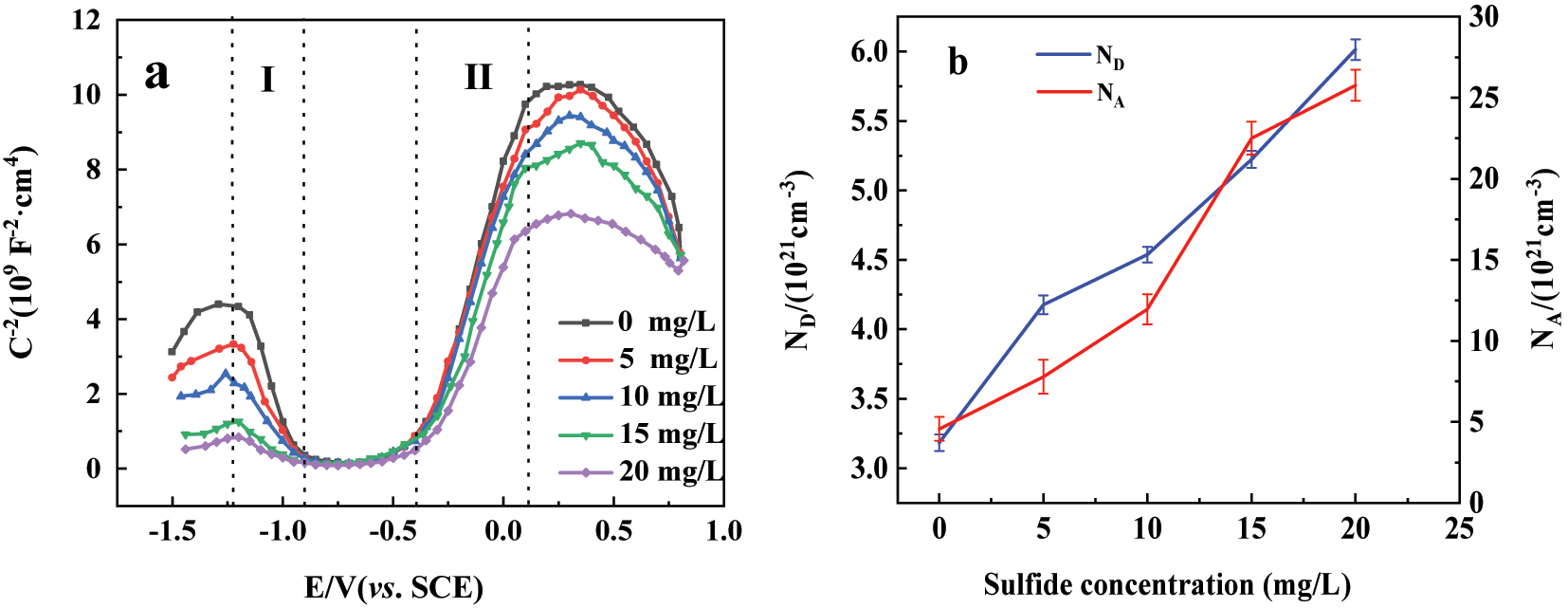

Figure 4(a) displays the Mott–Schottky plot of 304SS in simulated cooling water containing five concentrations of sulfide. Multiple inflection points were observed, indicating the presence of a p–n junction within the passive film (Hakiki et al. 1995; Yao et al. 2019). The region I in Figure 4 with a negative slope corresponds to chromium oxide in the passive film, and the region II with a positive slope corresponds to iron oxide in the passive film (Schmidt et al. 2006; Yao et al. 2019). The results in Figure 4(a) also show that as the concentration of sulfide increased, both the slope of the straight lines in region I and region II gradually decreased, indicating the change in the performance of the passive film.

The Mott–Schottky plots, donor and acceptor densities of the 304SS electrode immersed in simulated cooling water containing five concentrations of sulfide for 5 days: (a) The Mott–Schottky plots; (b) donor and acceptor densities.

Figure 4(b) represents the change of NA and ND of 304SS in water with sulfide concentrations. It can be observed that both NA and ND increased with the raise of sulfide concentration, and the increase of NA was more significant. This suggests that the addition of sulfide may alter the composition and structure of the passive film, enhancing its conductivity. Particularly, it may significantly increase the conductivity of chromium oxide, thereby affecting the corrosion resistance of the passive film (Ge et al. 2011).

3.2 Microelectrochemical analysis

3.2.1 Scanning Kelvin probe mapping analysis

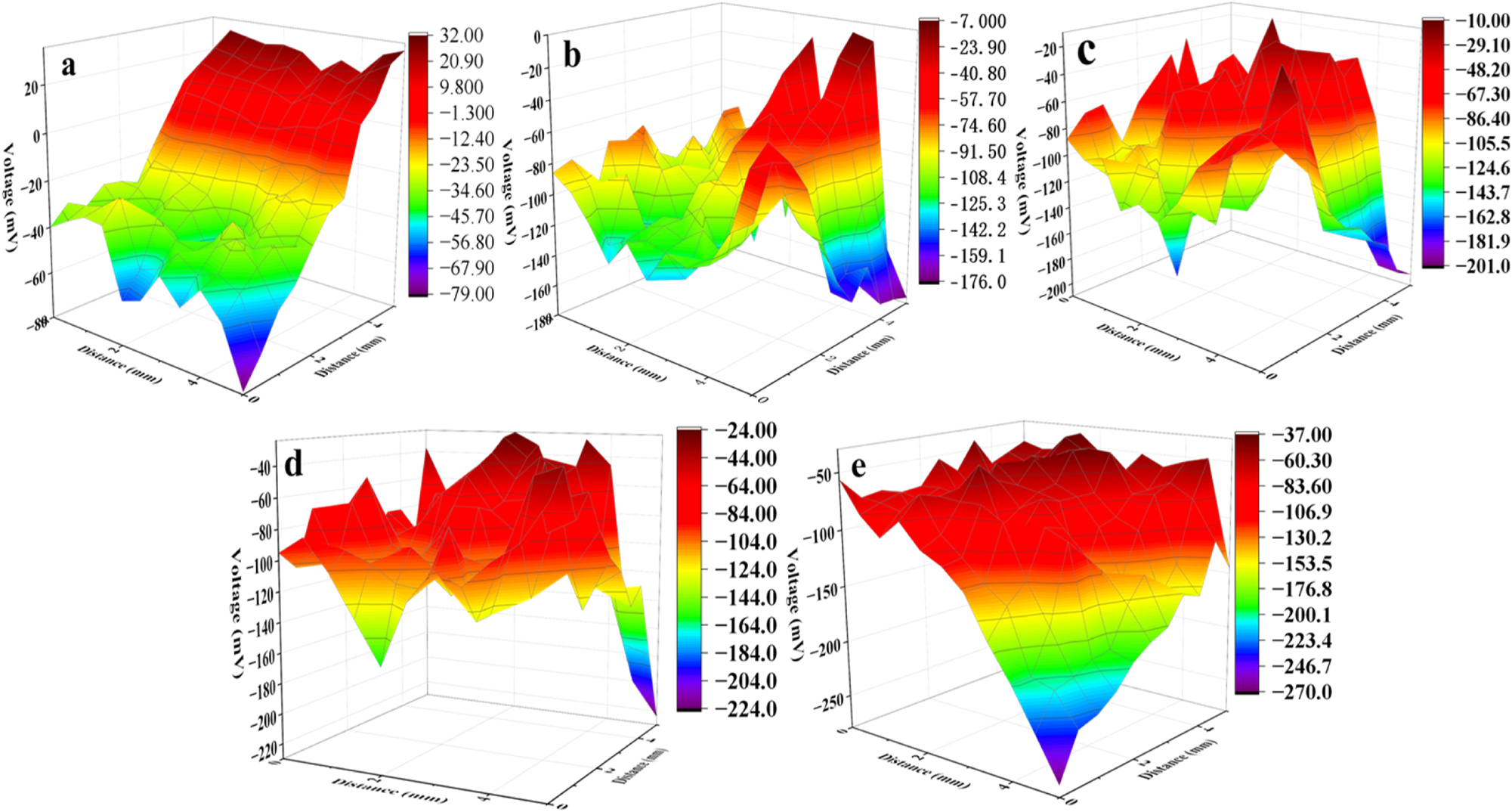

The three-dimensional maps of the surface potential detected by the scanning Kelvin probe were shown in Figure 5, which was carried out to analyze the changes of metal surface state at the microscopic scales. Figure 5(a) corresponds to the system without sulfide, and it can be observed that the surface potential distribution of stainless steel ranged from −79 mV ∼ 32 mV. After adding 5 mg/L sulfide, the surface potential of the electrode shifted negatively to −176 mV ∼ −7 mV, indicating a change in the surface active state in the scanned area. With the increase of sulfide concentration, the surface potential of stainless steel continued to shift negatively. The more negative the surface potential of the metal surface, the stronger the surface activity of the metal (Rohwerder and Turcu 2007; Stratmann et al. 1990). When the sulfide concentration was 20 mg/L, the surface potential shifted negatively to −270 mV ∼ −37 mV, reaching the most negative potential in Figure 5, indicating that the surface of stainless steel exhibits strong activity and a strong tendency toward corrosion under this condition.

Surface Kelvin probe (SKP) images of 304 stainless steel in simulated cooling water with different concentrations of sulfide concentrations of sulfide (mg/L): (a) 0; (b) 5; (c) 10; (d) 15; (e) 20.

According to the principles of electrochemical corrosion, the potential difference between micro-cathodes and micro-anodes on the metal surface is the driving force for microgalvanic corrosion (Tan et al. 2001, 2006). The greater the potential difference, the stronger the corrosion driving force. Table 3 shows the surface potential difference of stainless steel in simulated cooling water with different concentrations of sulfide. The surface potential difference was 111 mV in the water without sulfide. The higher the concentration of sulfide in simulated water, the greater the surface potential difference of stainless steel. The surface potential difference of stainless steel increased to 169 mV in simulated water with 5 mg/L sulfide, and increased to 233 mV in simulated water with 20 mg/L sulfide. The increase in surface potential difference indicates an increase in electrochemical inhomogeneity on the surface of stainless steel, and a decrease in the local corrosion resistance of stainless steel (Barranco et al. 2010).

The potential difference between the anodic and cathodic regions in Figure 5.

| Sulfide concentration (mg/L) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆ESKP (mV) | 111 | 169 | 191 | 200 | 233 |

3.2.2 In situ SECM mapping analysis

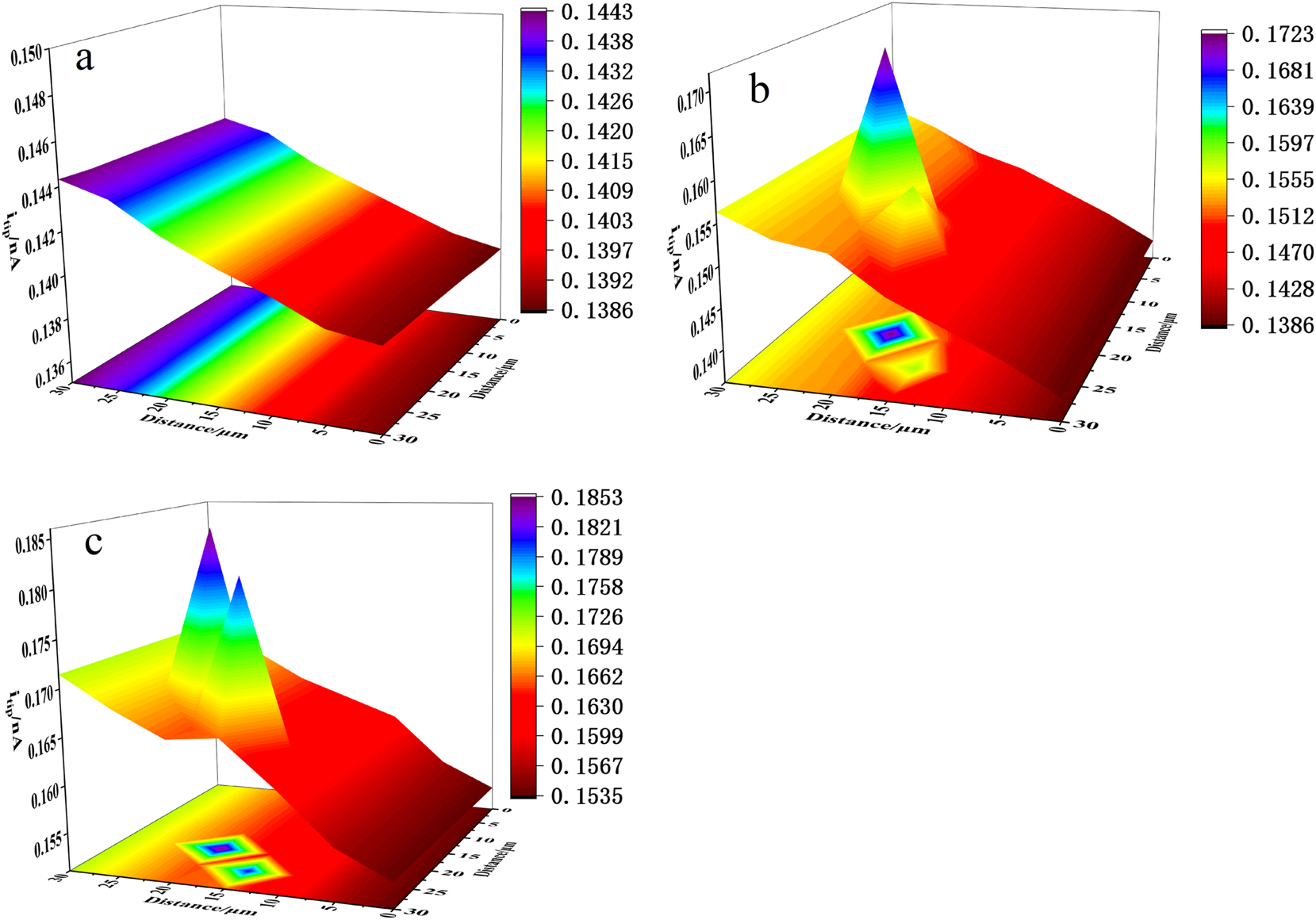

Scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) is an electroanalytical scanning probe technique (Zoski 2016). The surface electrochemical images can be obtained by measuring the current distribution of the redox reaction on the metal surface. The corrosion behavior and the performance of the protective film on metal surface can be analyzed according to the change of the response current. The greater the measured response current, the stronger the reaction activity of the metal surface, and the worse the protection of the film on metal surface. In this study, SECM was employed to analyze the degradation process of the passive film on 304SS surface over time in the simulated water containing sulfide.

The SECM images of stainless steel in simulated water without or with 20 mg/L sulfide are shown in Figure 6. In simulated water without sulfide, the response current on the stainless steel surface was about 0.140 nA–0.144 nA (Figure 6(a)), and no peak current appeared throughout the whole scanning area, indicating a good passivation state of the stainless steel surface. After immersing in simulated water containing 20 mg/L sulfide for 5 min, two obvious current peaks appeared in the SECM image, with the maximum current peak height being approximately 0.172 nA. This indicates the presence of active sites in the scanning area, and the passive film has been damaged to some extent, possibly due to micro pitting corrosion occurring at the weak points of the passive film (Dong et al. 2012). The breakdown of the passive film results in localized substrate exposure on the surface of stainless steel, and the enhanced conductivity of the exposed area leads to larger tip currents (Ma and Chen 2022). After immersing in simulated water containing sulfide for 30 min (Figure 6(c)), the maximum current peak on the passive film surface further increased to 0.185 nA, and the other current peak increased from 0.158 nA at 5 min to 0.181 nA. This indicates that the destructive effect of sulfide on the passive film on stainless steel surface was further enhanced, and the surface active points were developing (Lee and Bard 1990).

SECM images of 304SS surface immersed in the simulated cooling water: (a) without sulfide, (b) with 20 mg/L sulfide for 5 min, and (c) 30 min.

3.3 Passive film analysis by XPS

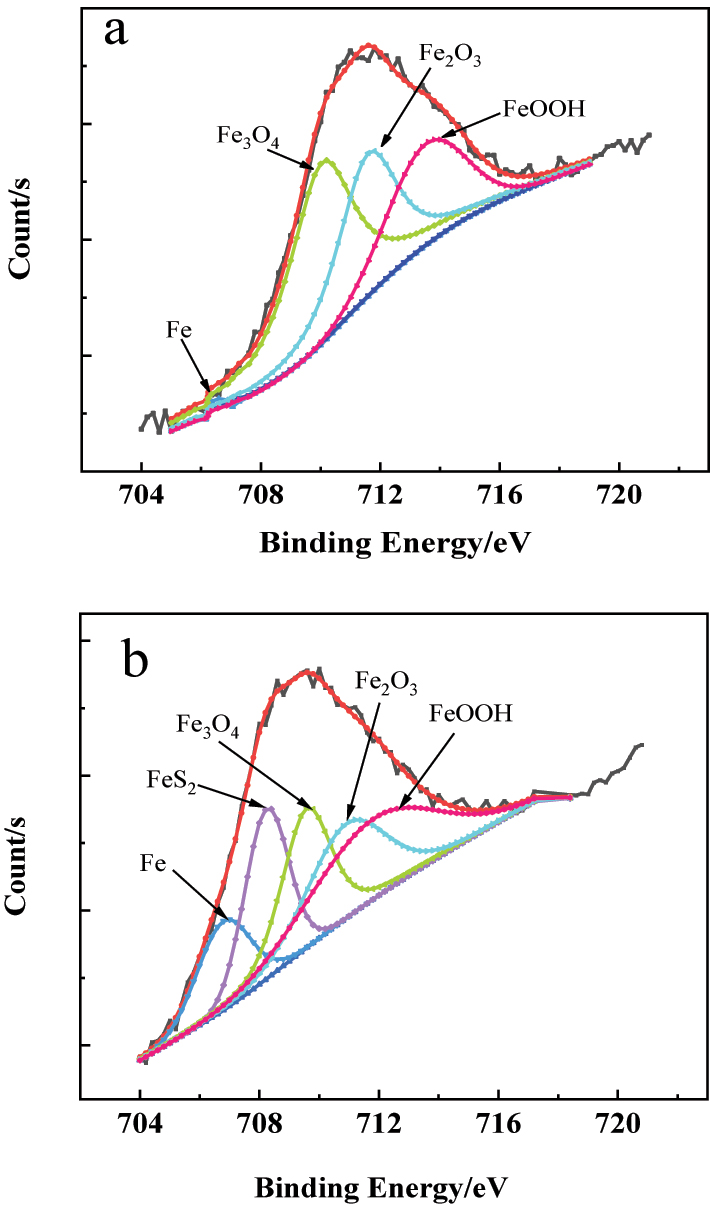

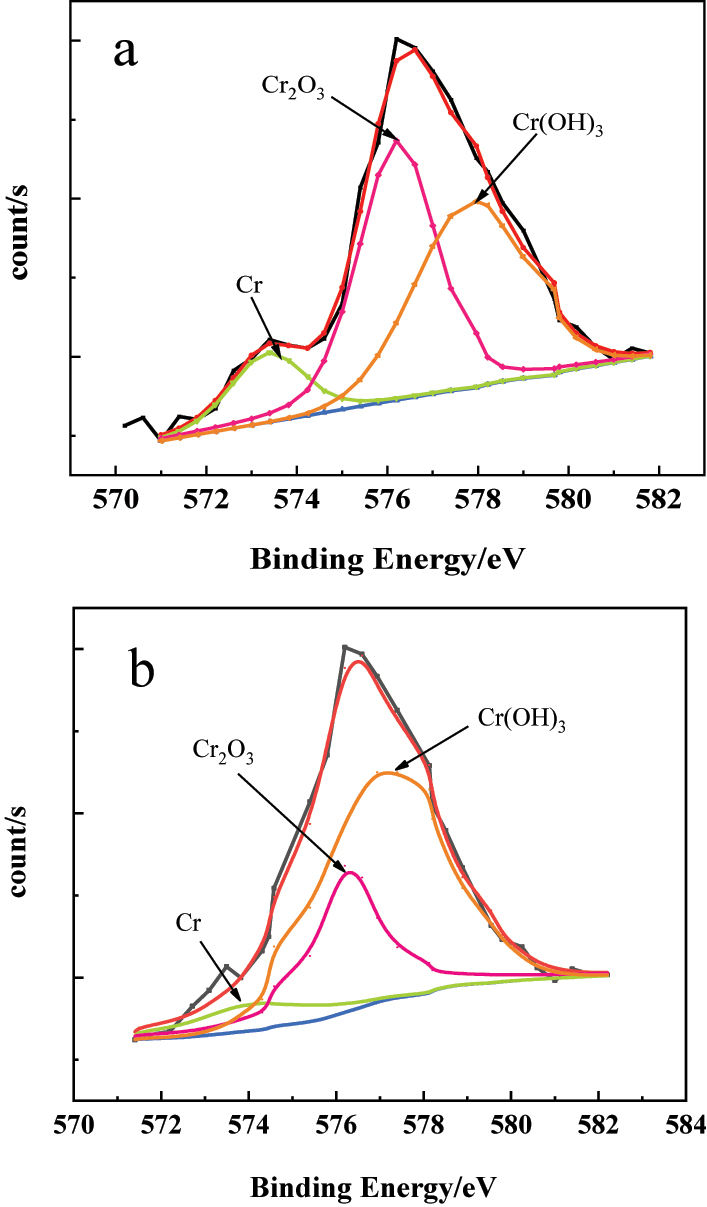

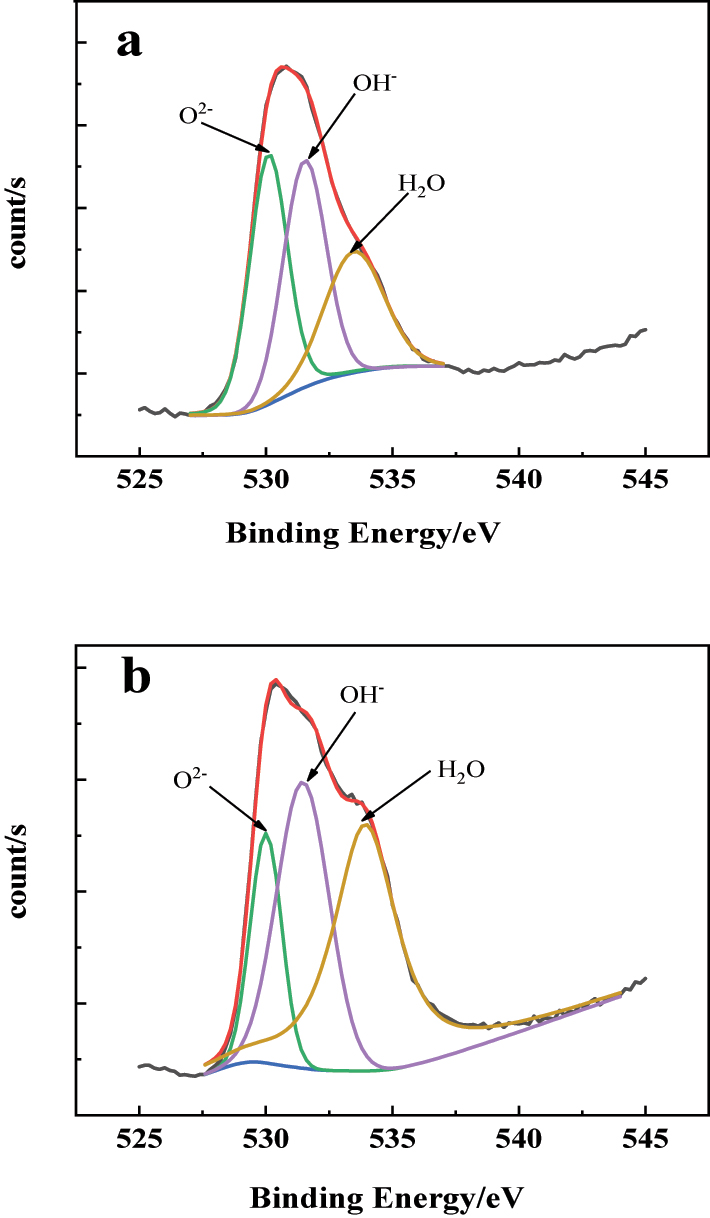

The chemical composition of the passive film on 304SS surface was analyzed by XPS to further understand the destructive effect of sulfide on the passive film. The spectra of the main elements in the passive film on the surface of stainless steel in simulated water without sulfide and with 20 mg/L sulfide were obtained, as shown in Figures 7–9.

The XPS spectrum of the Fe 2p3/2 in the passive film on the 304SS surface in simulated cooling water: (a) without and (b) with sulfide.

The XPS spectrum of the Cr 2p3/2 in the passive film on the 304SS surface in simulated cooling water: (a) without and (b) with sulfide.

The XPS spectrum of the O 1s in the passive film on the 304SS surface in simulated cooling water: (a) without and (b) with sulfide.

Usually, a nano thickness passive film composed of oxides and hydroxides of iron and chromium would form on the surface of stainless steel, located in the outer and inner layers of the passive film, respectively. The composition and content of the passive film determine its performance, among which an increase of chromium oxide and a decrease of hydroxide in the inner layer are beneficial for improving the performance of the passive film (Cui et al. 2023). The main reactions for passive film formation are (Luo et al. 2011):

The results in Figure 7(a) and Figure 8(a) show that, in simulated water without sulfide, iron compounds in the passive film on stainless steel mainly consist of FeOOH, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4, while chromium compounds are mainly Cr2O3 and Cr(OH)3. From a thermodynamic perspective (Yu et al. 2019), comparing the standard potentials of the main components of stainless steel, Cr (−0.74 V), Fe (−0.44 V), and Ni (−0.25 V), it can be found that chromium is more active than other elements. Therefore, chromium has the strongest oxidation tendency on the stainless steel surface, leading to the formation of chromium oxides. Additionally, the iron is also active, making it easy for iron oxides to form on the stainless steel surface.

Figure 7(b) and Figure 8(b) show the XPS spectra of Fe 2p3/2 and Cr 2p3/2 on the surface of 304SS in simulated water containing sulfide. The results in Figure 7(b) exhibit that, compared with the results in Figure 7(a), the content of iron oxides and hydroxides in the passive film decreased, and a new peak corresponding to FeS2 appeared. This might be attributed to the adsorption of HS− from the water on the 304SS surface, inhibiting the formation of oxides (Liu et al. 2009), while Fe and S have a high affinity and will react to form stable FeS2 (Azevedo et al. 1999). However, the formation of FeS2 with poor compactness alters the composition and structure of the passive film, which decreases the protective properties of the passive film. From the chromium compound shown in Figure 8(b), it can be seen that in simulated water containing sulfide, the content of Cr2O3 in the passive film decreased, while the content of Cr(OH)3 increased, compared with the results in Figure 8(a). It is generally believed that Cr2O3 with a network structure (Cr–O–Cr) has good compactness and strong protective performance (Betova et al. 2010). The decrease in content of Cr2O3 and increase in content of Cr(OH)3 in the passive film imply the degradation of the passive film and a decline in its protective performance. Figure 9 shows the XPS spectra of oxygen elements in the passive film of stainless steel surfaces in simulated cooling water without sulfide and with 20 mg/L sulfide. It indicates that the OH− content in the passive film increased, while the O2− content decreased when the water containing sulfide, which is consistent with the results mentioned above.

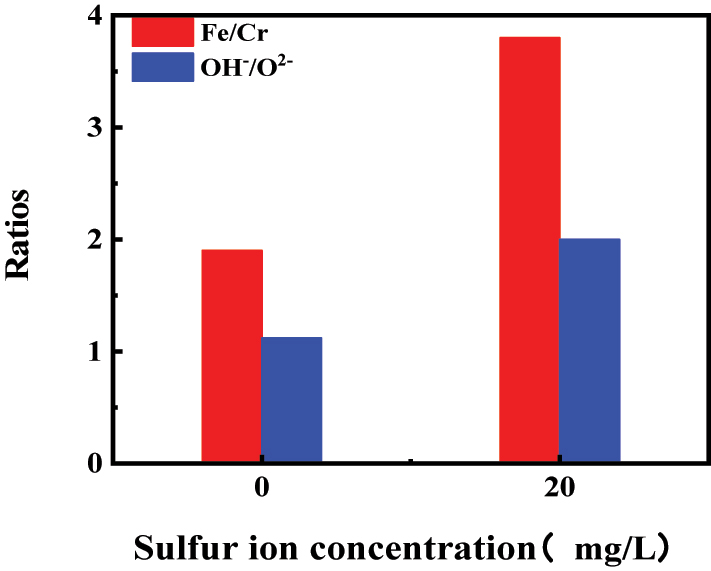

The changes in Fe/Cr and OH−/O2− ratios in the passive film of stainless steel before and after the addition of sulfide in water are shown in Figure 10. It is observed that both the Fe/Cr and OH−/O2− ratio in the passive film increased in the presence of sulfide in water, indicating a decrease in the content of chromium oxides in the passive film and a reduction in its protective performance (Shen et al. 2024). It also suggests an increase in the content of hydroxides and a decrease in the content of oxygen anions in the passive film. This phenomenon might be attributed to the adsorption of HS− on the Helmholtz layer surface, which promotes the formation of metal ions and leads to the combination of metal ions with OH− to form hydroxides (Lee et al. 2016b). The increase in hydroxide content also reduces the density and protection of the passive film, thereby increasing the susceptibility of pitting corrosion.

The Fe/Cr and OH−/O2− ratios in the passive film on the surface of 304SS before and after the addition of sulfide.

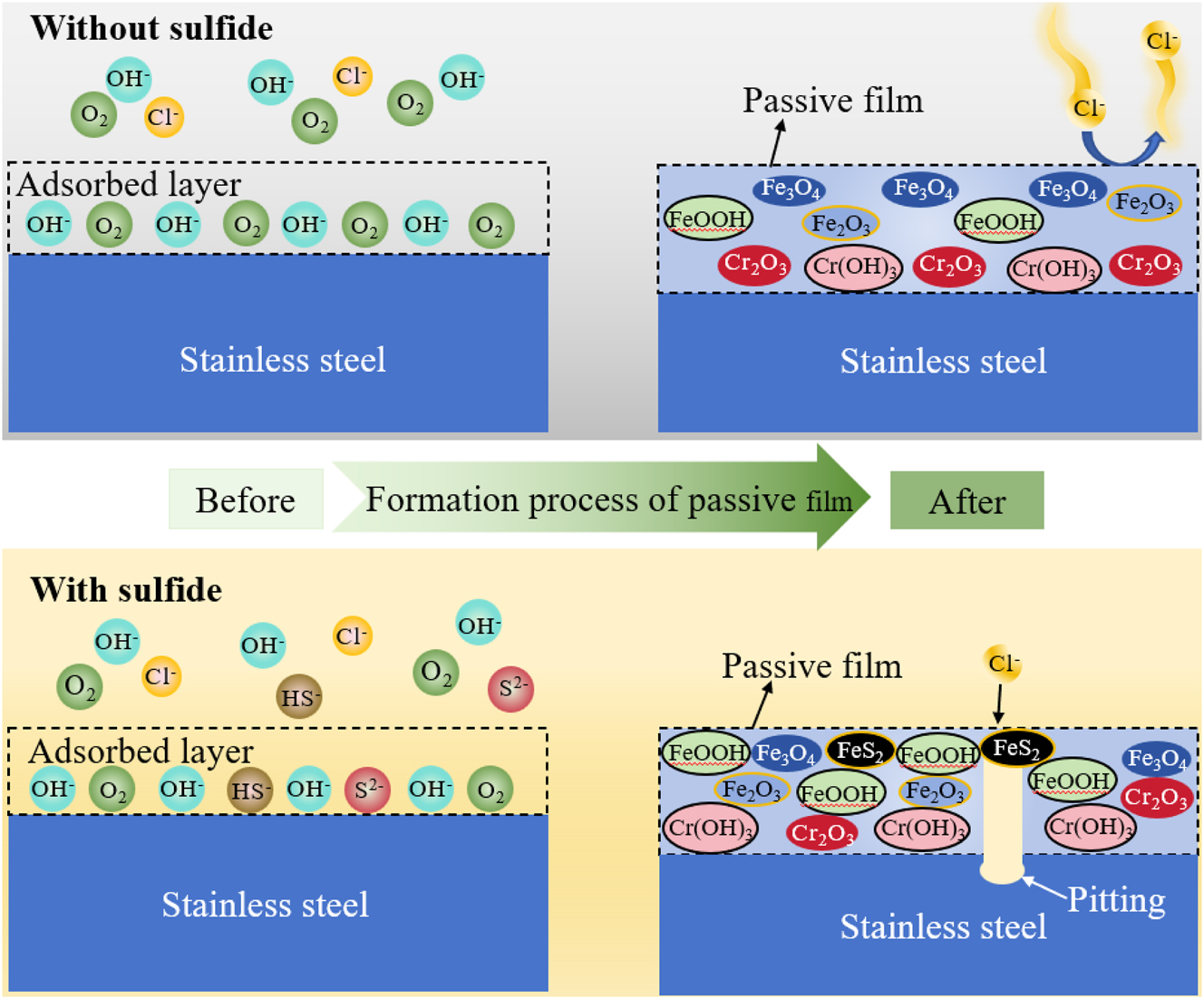

The damage mechanism of sulfide on the passive film of stainless steel can be represented by the schematic diagram in Figure 11. It is generally believed that the passive film on the surface of stainless steel presents a double-layer structure: an inner layer of chromium compound and an outer layer of iron compound (Xiao et al. 2022). The presence of sulfide in the simulated water led to the deterioration of the passive film on the surface of stainless steel, resulting in a decrease in impedance values and an increase in passive current density of the stainless steel electrode. With the increase in sulfide concentration, both the Fe/Cr ratio and the OH−/O2− ratio in the passive film increased, and the sulfide FeS2 appeared in the passive film. This indicates a reduction in the content of chromium oxides and an increase in the content of hydroxides, as well as an increase in electrochemical inhomogeneity of the passive film, thereby altering the compactness and protective performance of the passive film. These changes promote the occurrence of pitting corrosion on the surface of stainless steel.

Schematic diagram of the damage mechanism by sulfide to passive film on 304SS surface.

4 Conclusions

Combining macroscopic and microscopic electrochemical tests, the effect of sulfide in simulated cooling water on the passive film of stainless steel was investigated. The following conclusions were obtained:

The addition of sulfide to simulated water significantly increased the passive current density and accelerated the anodic dissolution process of stainless steel. The film resistance of stainless steel in water decreased significantly with the increase of sulfide concentration, indicating a decline in the protective performance of the passive film.

The donor density (ND) and acceptor density (NA) of the passive film on the surface of stainless steel increased with the addition of sulfide in water, and the increase in NA was more pronounced, indicating an increase in the conductivity of chromium and iron compounds in the passive film, especially chromium compounds.

The presence of sulfide in water enhanced the reactivity of the stainless steel surface, leading to an increase in the response current in SECM. Current peaks were observed in water containing sulfide, and their magnitude increased with time. Sulfide promotes pitting corrosion on the surface of stainless steel.

The presence of sulfide in water increased both the Fe/Cr and OH−/O2− ratios in the passive film on the stainless steel surface, resulting in a decrease in Cr2O3 content, an increase in Cr(OH)3 and Fe(OH)3 content, and the appearance of FeS2. These changes reduce the compactness and protective performance of the passive film, leading to an increase in pitting sensitivity.

Funding source: Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality

Award Identifier / Grant number: 23010501300

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Jinrong Huang: experiments, data analysis, and writing; Jun Wu: replication; Zhuoran Li: data analysis; Honghua Ge: funding, theoretical analysis, and writing; Ping Liu: data analysis and writing.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was financially supported by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (23010501300).

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

Abreu, C.M., Cristóbal, M.J., Losada, R., Nóvoa, X.R., Pena, G., and Pérez, M.C. (2004). Comparative study of passive films of different stainless steels developed on alkaline medium. Electrochim. Acta 49: 3049–3056, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2004.01.064.Search in Google Scholar

Azevedo, C., Bezerra, P.S.A., Esteves, F., Joia, C.J.B.M., and Mattos, O.R. (1999). Hydrogen permeation studied by electrochemical techniques. Electrochim. Acta 44: 4431–4442, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-4686(99)00158-9.Search in Google Scholar

Barranco, V., Onofre, E., Escudero, M.L., and García-Alonso, M.C. (2010). Characterization of roughness and pitting corrosion of surfaces modified by blasting and thermal oxidation. Surf. Coat. Tech. 204: 3783–3793, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2010.04.051.Search in Google Scholar

Barroux, A., Delgado, J., Orazem, M.E., Tribollet, B., Laffont, L., and Blanc, C. (2021). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study of the passive film for laser-beam-melted 17-4PH stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 191: 109750, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109750.Search in Google Scholar

Bellezze, T., Giuliani, G., and Roventi, G. (2018). Study of stainless steels corrosion in a strong acid mixture. Part 1: cyclic potentiodynamic polarization curves examined by means of an analytical method. Corros. Sci. 130: 113–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2017.10.012.Search in Google Scholar

Betova, I., Bojinov, M., Karastoyanov, V., Kinnunen, P., and Saario, T. (2010). Estimation of kinetic and transport parameters by quantitative evaluation of EIS and XPS data. Electrochim. Acta 55: 6163–6173, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2009.11.100.Search in Google Scholar

Cui, T.Y., Qian, H.C., Chang, W.W., Zheng, H.B., Guo, D.W., Kwok, C.T., Tam, L.M., and Zhang, D.W. (2023). Towards understanding Shewanella algae-induced degradation of passive film of stainless steel based on electrochemical, XPS and multi-mode AFM analyses. Corros. Sci. 218: 111174, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2023.111174.Search in Google Scholar

Cui, Z.Y., Chen, S.S., Wang, L.W., Man, C., Liu, Z.Y., Wu, J.S., Wang, X., Chen, S.G., and Li, X.G. (2017). Passivation behavior and surface chemistry of 2507 super duplex stainless steel in acidified artificial seawater containing thiosulfate. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164: C856–C868, https://doi.org/10.1149/2.1901713jes.Search in Google Scholar

Dong, C.F., Luo, H., Xiao, K., Li, X.G., and Cheng, Y.F. (2012). In situ characterization of pitting corrosion of stainless steel by a scanning electrochemical microscopy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 21: 406–410, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-011-9899-y.Search in Google Scholar

Ferreira, M.G.S., Simões, A.M., Oliveira, D.K., and Montemor, M.F. (2013). Influence of sulfide on the electrochemical behavior and passivity of AISI 304 stainless steel in simulated concrete pore solutions. Corros. Sci. 74: 61–71.Search in Google Scholar

Ge, H.H., Zhou, G.D., and Wu, W.Q. (2003). Passivation model of 316 stainless steel in simulated cooling water and the effect of sulfide on the passive film. Appl. Surf. Sci. 211: 321–334, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-4332(03)00355-6.Search in Google Scholar

Ge, H.H., Xu, X.M., Zhao, L., Song, F., Shen, J., and Zhou, G.D. (2011). Semiconducting behavior of passive film formed on stainless steel in borate buffer solution containing sulfide. J. Appl. Electrochem. 41: 519–525, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10800-011-0272-5.Search in Google Scholar

Hakiki, N.B., Boudin, S., Rondot, B., and Belo, M.D.C. (1995). The electronic structure of passive films formed on stainless steels. Corros. Sci. 37: 1809–1822, https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-938x(95)00084-w.Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, B., Guo, T., Peng, Q., Jiao, Z., Volinsky, A.A., Gao, L., Ma, Y., and Qiao, L. (2019). Proton irradiation effects on the electron work function, corrosion and hardness of austenitic stainless steel phases. Corros. Sci. 157: 498–507, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2019.06.011.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, C. and Bard, A.J. (1990). Scanning electrochemical microscopy. Application to polymer and thin metal oxide films. Anal. Chem. 62: 1906–1913, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac00217a003.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, H.S., Park, J.H., Singh, J.K., and Ismail, M.A. (2016a). Protection of reinforced concrete structures of waste water treatment reservoirs with stainless steel coating using arc thermal spraying technique in acidified water. Materials 9: 753, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9090753.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lee, J.S., Kitagawa, Y.C., Nakanishi, T., Hasegawa, Y., and Fushimi, K. (2016b). Passivation behavior of type-316L stainless steel in the presence of hydrogen sulfide ions generated from a local anion generating system. Electrochim. Acta 220: 304–311, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2016.10.124.Search in Google Scholar

Lei, Z., Lu, M.X., Wang, J., Wen, Z.B., and Hao, W.H. (2014). The electrochemical behaviour of 316L austenitic stainless steel in Cl− containing environment under different H2S partial pressures. Appl. Surf. Sci. 289: 33–41, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.10.080.Search in Google Scholar

Li, W., Wang, W., Ren, W., Wu, H., Li, N., and Chen, J. (2024). Microstructure and corrosion properties of Cr41CoFeNi eutectic high-entropy alloy in sulfuric acid solution. J. Alloys Compd. 978: 173443, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.173443.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, R., Li, J., Liu, Z., Du, C., Dong, C., and Li, X. (2015). Effect of pH and H2S concentration on sulfide stress corrosion cracking (CSCC) of API 2205 duplex stainless steel. Int. J. Mater. Res. 106: 608–613, https://doi.org/10.3139/146.111220.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, M., Liu, B., Ni, Z., Du, C., and Li, X. (2024). Elucidating the effect of titanium alloying on the pitting corrosion of ferritic stainless steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 28: 1247–1262, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.12.032.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Z.Y., Dong, C.F., Li, X.G., Zhi, Q., and Cheng, Y.F. (2009). Stress corrosion cracking of 2205 duplex stainless steel in H2S-CO2 environment. J. Mater. Sci. 44: 4228–4234, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-009-3520-x.Search in Google Scholar

Luo, H., Dong, C.F., Xiao, K., and Li, X.G. (2011). Characterization of passive film on 2205 duplex stainless steel in sodium thiosulphate solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258: 631–639, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2011.06.077.Search in Google Scholar

Ma, Y.L. and Chen, M. (2022). Combined SECM and spectroscopy investigation of the interfacial chemistry of chalcopyrite during anodic oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 419: 140393, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2022.140393.Search in Google Scholar

Marcus, P. (1998). Surface science approach of corrosion phenomena. Electrochim. Acta 43: 109–118, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-4686(97)00239-9.Search in Google Scholar

Maysam, M., Choudhary, L., Gadala, I.M., and Alfantazi, A. (2016). Electrochemical and passive layer characterizations of 304L, 316L, and duplex 2205 stainless steels in thiosulfate gold leaching solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163: C883–C894, https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0841614jes.Search in Google Scholar

Rhode, S., Kain, V., Raja, V.S., and Abraham, G. (2013). Factors affecting corrosion behavior of inclusion containing stainless steels: a scanning electrochemical microscopic study. Mater. Charact. 77: 109–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2013.01.006.Search in Google Scholar

Rohwerder, M. and Turcu, F. (2007). High-resolution Kelvin probe microscopy in corrosion science: scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy (SKPFM) versus classical scanning Kelvin probe (SKP). Electrochim. Acta 53: 290–299, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2007.03.016.Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt, A.M., Azambuja, D.S., and Martini, E.M.A. (2006). Semiconductive properties of titanium anodic oxide films in mcIlvaine buffer solution. Corros. Sci. 48: 2901–2912, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2005.10.013.Search in Google Scholar

Schultze, J.W. and Lohrengel, M.M. (2000). Stability reactivity and breakdown of passive films. Problems of recent and future research. Electrochim. Acta 45: 2499–2513, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-4686(00)00347-9.Search in Google Scholar

Senka, G., Vrsalović, L., Matošin, A., Krolo, J., Oguzie, E.E., and Nagode, A. (2023). Corrosion behavior of stainless steel in seawater in the presence of sulfide. Appl. Sci. 13: 4366, https://doi.org/10.3390/app13074366.Search in Google Scholar

Shen, Z.D. (2024). The influence of Cr and Mo on the formation of the passivation film on the surface of ferritic stainless steel. Mater. Today Commun. 38: 108221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.108221.Search in Google Scholar

Steensland, O. (1968). Contribution to the discussion on pitting corrosion of stainless steels. Anti Corros. Method. Mater. 15: 8–19, https://doi.org/10.1108/eb005247.Search in Google Scholar

Stratmann, M. and Streckel, H. (1990). On the atmospheric corrosion of metals which are covered with thin electrolyte layers. II. Experimental results. Corros. Sci. 30: 697–714, https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-938x(90)90033-2.Search in Google Scholar

Tan, Y.J., Bailey, S., and Kinsella, B. (2001). Mapping non-uniform corrosion using the wire beam electrode method (I, II and III). Corros. Sci. 43: 1905–1937.10.1016/S0010-938X(00)00192-XSearch in Google Scholar

Tan, Y.J., Aung, N.N., and Liu, T. (2006). Novel corrosion experiments using the wire beam electrode. (I) Studying electrochemical noise signatures from localised corrosion processes. Corros. Sci. 48: 23–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2004.11.019.Search in Google Scholar

Tang, J.L., Yang, X., Wang, Y.Y., Wang, H., Xiao, Y., Apreutesei, M.H., Nie, Z., and Normand, B. (2019). Corrosion behavior of 2205 duplex stainless steels in HCl solution containing sulfide. Metals 9: 294, https://doi.org/10.3390/met9030294.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Z., Feng, Z., and Zhang, L. (2020). Effect of high temperature on the corrosion behavior and passive film composition of 316 L stainless steel in high H2S-containing environments. Corros. Sci. 174: 108844, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2020.108844.Search in Google Scholar

Xiao, Y., Tang, J.L., Wang, Y.Y., Lin, B., Nie, Z., Li, Y.F., Normand, B., and Wang, H. (2022). Corrosion behavior of 2205 duplex stainless steel in NaCl solutions containing sulfide ions. Corros. Sci. 200: 110240, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2022.110240.Search in Google Scholar

Yao, J.Z., Macdonald, D.D., and Dong, C.F. (2019). Passive film on 2205 duplex stainless steel studied by photo-electrochemistry and ARXPS methods. Corros. Sci. 146: 221–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.10.020.Search in Google Scholar

Ye, Z.N., Zhu, Z.J., Zhang, Q.H., Liu, X.Y., Zhang, J.Q., and Cao, F.H. (2018). In situ SECM mapping of pitting corrosion in stainless steel using submicron Pt ultramicroelectrode and quantitative spatial resolution analysis. Corros. Sci. 143: 221–228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.08.014.Search in Google Scholar

Yu, L.S., Tang, J.L., Wang, H., Wang, Y.Y., Qiao, J.C., Apreutesei, M.H., and Normand, B. (2019). Corrosion behavior of bulk (Zr58Nb3Cu16Ni13Al10)100-XYx (X=0, 0.5, 2.5 at.%) metallic glasses in sulfuric acid. Corros. Sci. 150: 42–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2019.01.016.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, G.A., Zeng, Y., Guo, X.P., Jiang, F., Shi, D.Y., and Chen, Z.Y. (2012). Electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel under dynamic high pressure H2S/CO2 environment. Corros. Sci. 65: 37–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2012.08.007.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, M., Qian, Z.H., Qin, R.J., Yu, J.Y., Wang, Y.J., and Niu, L. (2013). In situ SECM study on concentration profiles of electroactive species from corrosion of stainless steel. Corros. Eng. Sci. Tech. 48: 270–275, https://doi.org/10.1179/1743278212y.0000000066.Search in Google Scholar

Zheng, S.Q., Li, C.Y., Qi, Y.M., Chen, L.Q., and Chen, C.F. (2013). Mechanism of (Mg, Al, Ca)-oxide inclusion-induced pitting corrosion in 316L stainless steel exposed to sulphur environments containing chloride ion. Corros. Sci. 67: 20–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2012.09.044.Search in Google Scholar

Zheng, Z.B. and Zheng, Y.G. (2016). Effects of surface treatments on the corrosion and erosion-corrosion of 304 stainless steel in 3.5% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 112: 657–668, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2016.09.005.Search in Google Scholar

Zoski, C.G. (2016). Review: advances in scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM). J. Electrochem. Soc. 163: 3088–3100, https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0141604jes.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Why is the modified wedge-opening-loaded test inadequate for characterizing gaseous hydrogen embrittlement in pipeline steels? A review

- Research progress on zirconium alloys: applications, development trend, and degradation mechanism in nuclear environment

- Original Articles

- Effect of seawater intrusion in water-glycol hydraulic fluid on the electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel and stainless steel

- Durability of a thermally decomposed iridium(IV) oxide–tantalum(V) oxide coated titanium anode in aqueous ammonium citrate

- Microscopic analysis of the destruction of passive film on stainless steel caused by sulfide in simulated cooling water

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Why is the modified wedge-opening-loaded test inadequate for characterizing gaseous hydrogen embrittlement in pipeline steels? A review

- Research progress on zirconium alloys: applications, development trend, and degradation mechanism in nuclear environment

- Original Articles

- Effect of seawater intrusion in water-glycol hydraulic fluid on the electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel and stainless steel

- Durability of a thermally decomposed iridium(IV) oxide–tantalum(V) oxide coated titanium anode in aqueous ammonium citrate

- Microscopic analysis of the destruction of passive film on stainless steel caused by sulfide in simulated cooling water