Abstract

Water-glycol hydraulic fluid (HFC) has been applied in deep-sea hydraulic systems owing to its flame retardant and environmental performance. However, the corrosion characteristics of metals in HFC have not been widely investigated. The electrochemical corrosion behavior of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC containing four concentrations of seawater (0 %, 3 %, 11 %, 19 %) were evaluated by potentiodynamic polarizations (−800 mV∼1,500 mV vs. Hg/HgO), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), potentiostatic polarizations (0.5 VHg/HgO) and immersion test (240 h). The research results indicate that a corrosion-resistant carbon film is formed on the surface of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel in HFC. The infrared spectroscopy results suggest that the formation of the carbon film is due to the adsorption of the benzene ring of tolyltriazole (TTA) in HFC by the metal C. 45# steel exhibited stronger corrosion resistance than 17-4PH stainless steel due to the formation of a denser carbon film through high carbon content adsorption. The infiltration of seawater into HFC enhanced its corrosiveness by enhancing its conductivity and Cl− pitting on the C film. This research is significant as it sheds light on the corrosion behavior of metals in HFC, a crucial aspect in the design and maintenance of deep-sea hydraulic systems.

1 Introduction

There are abundant resources with development and utilization value in the deep-sea environment, such as manganese nodules, deep-sea oil and gas, hydrothermal deposits, and natural gas hydrates. These are of great value for exploitation and application. Hydraulic systems were widely used in deep-sea resource extraction equipment owing to good rigidity, compact structure, high load-bearing capacity, high power-to-weight ratio, and fast response speed (Quan et al. 2016). The mineral oil in the deep-sea hydraulic system might leak during operation, causing combustion and polluting the marine environment (Ding et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2010). Water-glycol hydraulic fluid (HFC) has shown great potential as a substitute for mineral oil in deep-sea hydraulic systems due to its flame-retardant and environmentally friendly properties (Ding et al. 2019; Totten 2011; Zheng et al. 2010). HFC mainly contained 35–60 % water to resist combustion, non-toxic and biodegradable ethylene glycol as an antifreeze, and thickener (such as polyethylene glycol) to provide the viscosity required for hydraulic systems. In addition, trace and necessary additives in HFC, such as sodium sulfonate, fatty acid ester, phosphate ester, amine salt, carboxylic acid, etc., were used to prevent wear and corrosion of components, foaming of hydraulic fluids, and microbial degradation. Ethylene glycol could oxidize and decompose into organic acids such as glycolic acid and oxalic acid during use, leading to metal corrosion (Zuo et al. 2021). At the same time, these trace and necessary functional additives caused HFC to become an electrolyte solution, resulting in electrochemical corrosion of metal materials (Zavieh and Espallargas 2017). Seawater could enter the hydraulic system in the deep sea due to seal failure, accelerating component corrosion (Al-Malahy and Hodgkiess 2003; Ma et al. 2022; Malik et al. 1994). This led to seawater intrusion into the deep-sea hydraulic system, further affecting corrosion performance. Therefore, the corrosion resistance of metal materials in HFC containing seawater must be evaluated to meet the needs of deep-sea hydraulic systems design.

Zavieh and Espallargas (2017) investigated the tribology and corrosion behavior of UNS S31603 austenitic stainless steel in HFC. The author studied the effect of adding palmitic acid and NaCl solution to water-glycol fluid on its lubricity and corrosiveness. The palmitic acid enhances the stability of passivation films. Wang et al. (2014) reduced the corrosion ability of water-glycol fluid to copper by adding derivatives of 2,5-dimercapto-1,3,4-thiadiazole to water-glycol fluid. 1,3,4-Thiadiazole rings promoted the formation of a protective film on the copper surface as a chelating agent. Xiong et al. (Xiong et al. 2016) studied the anti-corrosion behavior of N-containing heterocyclic imidazoline compounds (BM and MM) as additives for water-glycol fluids. The BM and MM promoted the formation of stable adsorption films on the metal surface, which had good rust and corrosion resistance. Zheng et al. (2022) investigated the anti-corrosion behavior of three eco-friendly protonic ionic liquids (DSD, CPC, and RPR) in water-glycol fluid. RPR showed the highest corrosion inhibition efficiency compared to the other two ionic liquids owing to its most substantial adsorption and the smallest ∆E. Su et al. (2021) improved the corrosion resistance of cast iron in aqueous ethylene glycol solutions by adding protonic ionic liquids. The existing research mainly focuses on the anti-corrosion behavior of a single corrosion additive added to water-glycol liquid. Wang et al. (Wang et al. 2012) found that magnesium alloys could adsorb ethylene glycol to suppress surface pitting corrosion. Zhang et al. (Zhang et al. 2008) found that Al-alcohol film was formed on the surface of 3003 aluminum in an ethylene glycol-water solution, which helps to inhibit the anodic dissolution of Al. Zhang et al. (Zhang et al. 2018) found that pure ethylene glycol can inhibit the anodic dissolution of aluminum alloys. Fekry and Fatayerji (2009) found that ethylene glycol can cover the surface of magnesium alloys, effectively protecting them from water corrosion. However, the inhibitory effect of ethylene glycol and corrosion inhibitors on commonly used materials such as stainless steel and carbon steel used in hydraulic systems is unknown. Therefore, the corrosion behavior of metal materials in HFC used in hydraulic systems has not been thoroughly and systematically studied. The comparison of corrosion resistance of metal materials in HFC was not yet known. The influence of seawater infiltration into HFC on its corrosion performance has not been paid attention to and studied. It was necessary to evaluate the corrosion resistance of metals in HFC containing seawater to meet the design needs of deep-sea hydraulic systems.

In this study, the electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel and stainless steel, two metal materials widely used in deep-sea equipment, in HFC containing four concentrations of seawater (0 %, 3 %, 11 %, 19 %) was studied by using potentiodynamic polarizations, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), potentiostatic polarizations and immersion test. The microstructure, corrosion morphology, and elemental composition of carbon steel and stainless steel in HFC with four seawater contents were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), EDS spectroscopy, and infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR). On this basis, the influence of seawater on the corrosion performance of HFC was studied.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials preparation

Two metal materials were used for electrochemical testing, including stainless steel (17-4PH stainless steel) and carbon steel (45# steel), as these two materials were commonly used in hydraulic systems in the deep sea. A commercial 17-4PH stainless steel was a high-strength and corrosion-resistant martensitic stainless steel, which was composed of 15–17 % Cr, 3.0–5.0 % Ni, 3.0–5.0 % Cu, 0.07 % C (max), 0.15–0.45 % (Nb + Ta) and 78.78–72.48 % Fe (wt.%). A commercial 45# steel was a high-quality carbon structural steel, mainly composed of 0.505 % C, 0.22 % Si, 0.65 % Mn, and 98.625 % Fe in chemical composition. 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel have not undergone heat treatment. Specimens for corrosion testing were polished up to 2,000 mesh and cleaned with anhydrous ethanol. The main components of HFC with a viscosity of 46 are shown in Table 1. Deionized water and sea salt were used to prepare artificial seawater (pH 8.24) to simulate seawater entry. The seal failure in the hydraulic system was simulated by gradually increasing the amount of seawater in the HFC. The deep-sea hydraulic system was installed inside the cabin without direct contact with seawater. At the same time, the heat is generated by the onboard equipment’s operation. Therefore, the working temperature of deep-sea hydraulic systems is generally around 30°Cn (Tian et al. 2022). Thus, the electrochemical experiments in this study were conducted at room temperature.

HFC composition.

| Component | Mass % |

|---|---|

| Deionized water | 59.0 |

| Diethylene glycol | 31.0 |

| Polyether | 4.0 |

| N,N-dimethylethanolamine | 3.0 |

| Capric acid | 1.5 |

| Tolyltriazole (TTA) | 1 |

| Morpholine | 0.5 |

2.2 Electrochemical behavior characterization

An electrochemical workstation (Corrtest, China) with a standard three-electrode system was used to perform potentiodynamic polarizations, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and potentiostatic polarizations in HFC with four proportions of seawater (0 %, 3 %, 11 %, 19 %) at room temperature. The working electrode was the tested specimens, the reference electrode was the Hg/HgO (1.0 mol/L KOH), and the counter electrode was a platinum plate. EIS characterization was performed to achieve testing accuracy after measuring the open circuit potential (OCP) at 7,200 s. The frequency range measured by EIS was from 100 kHz to 10 mHz, and 10 mV was set as the amplitude of the AC disturbance signal. Next, a scanning rate at 1 m V/s and the scanning range of −800∼1,500 mV (vs. Ref) were used to perform the potentiodynamic polarization curve tests. Besides, a passivation potential of 0.5 VHg/HgO was used to proceed with the potentiostatic polarization for 2 h. The obtained EIS data were processed via ZsimpWin software. We use numbers 1–8 to represent the tests of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel under different conditions. The number 1 represents the experiment of 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC without seawater. The number 2 represents the experiment of 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC containing 3 % seawater. The number 3 represents the experiment of 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC containing 11 % seawater. The number 4 represents the experiment of 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC containing 19 % seawater. The number 5 represents the experiment of 45# steel in HFC without seawater. The number 6 represents the experiment of 45# steel in HFC containing 3 % seawater. The number 7 represents the experiment of 45# steel in HFC containing 11 % seawater. The number 8 represents the experiment of 45# steel in HFC containing 19 % seawater. At least three electrochemical measurements were conducted to ensure the accuracy of the experimental results.

2.3 Immersion tests

45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel were immersed in HFC solutions containing 0 and 7 % seawater for 240 h to determine weight loss. After 240 h of immersion, the specimens were cleaned with alcohol and then blown dry. The weight before corrosion and after the removal of corrosion products of specimens were weighted with a precision of 0.0001 g.

2.4 Surface characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, SU3900, HITACHI) and EDS spectroscopy were used to analyze the morphology and composition of metal surfaces. The chemical properties of the surface were characterized by infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) (Nicolet iS50R).

3 Results

3.1 Immersion tests results

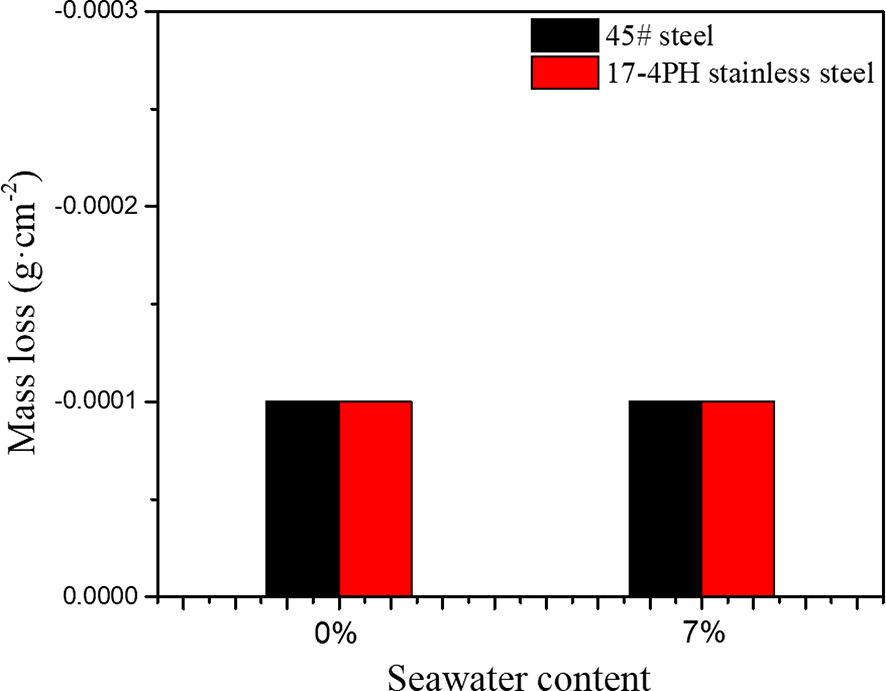

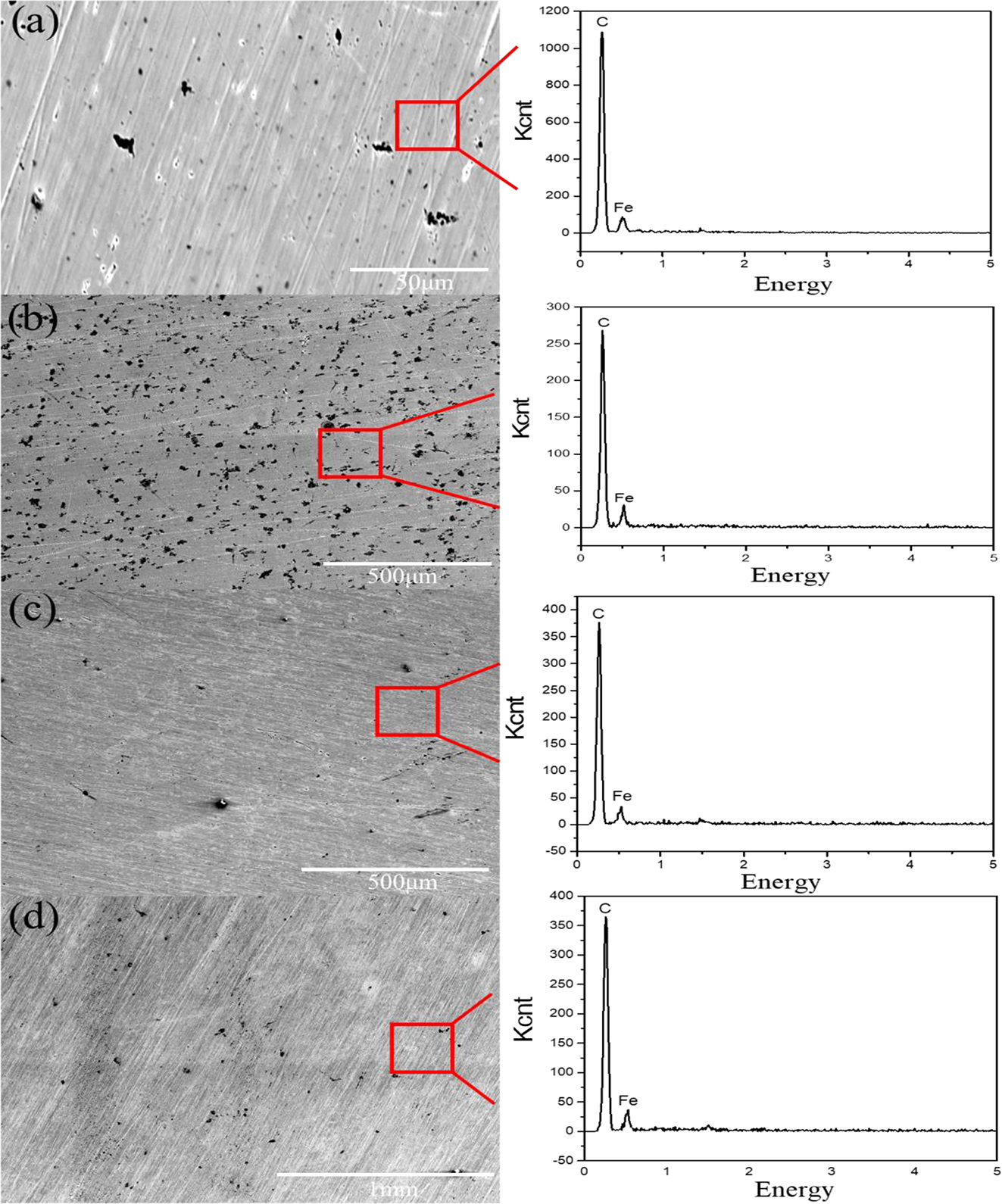

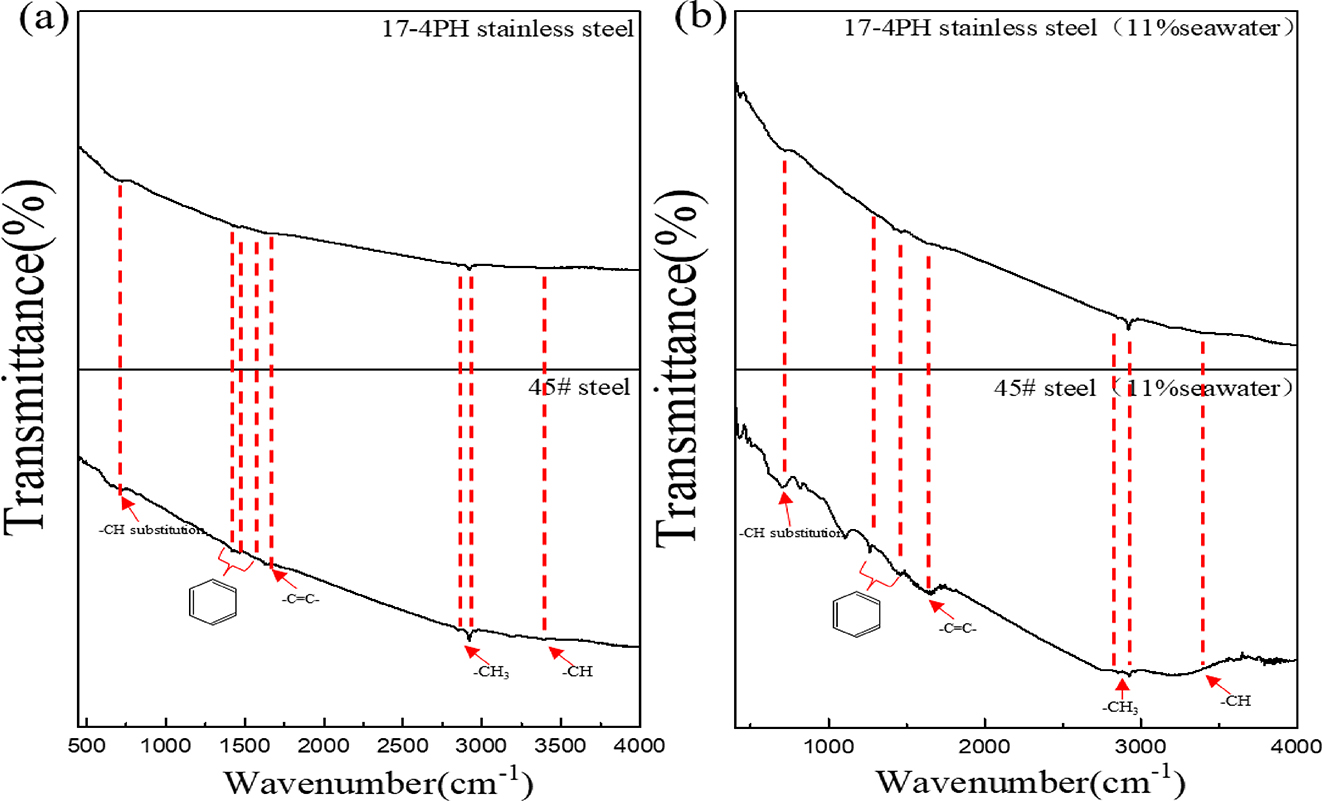

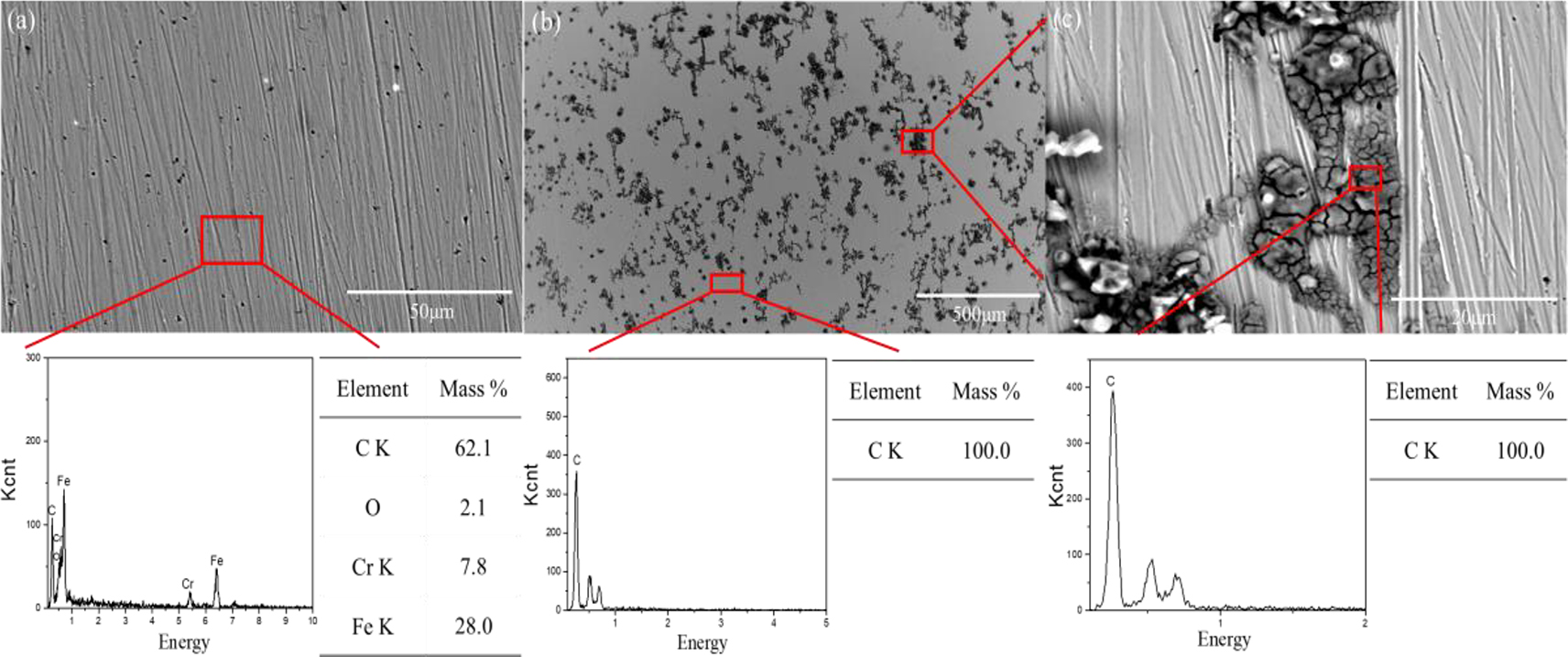

Figure 1 shows the mass changes of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel after being immersed in HFC with two seawater concentrations (0, 7 %) for 240 h. It can be seen from Figure 1 that the weight of the two metals in HFC with two amounts of seawater increased after immersion for 240 h. This meant that both metals adsorb substances in HFC. Figure 2 shows the SEM and EDS results of the surface of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel after immersion for 240 h. The SEM results indicated no noticeable corrosion scars on the surface of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel. The EDS results showed that the products adsorbed on the surface of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel are carbon films. This meant that the metal surface adsorbs substances in HFC to form a passivation layer to resist corrosion. The infrared spectra of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel immersed in HFC containing 7 % seawater for 240 h were shown in Figure 3. The peak at 3,185.70 cm−1 was attributed to the C–H bond on the benzene ring. The peak at 2,919 and 2,849 cm−1 was methyl (CH3). The peak at 1,644 cm−1 was attributed to –C=C–, which might originate from C in 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel. The peaks at 1,527, 1,464, and 1,422 cm−1 were attributed to the benzene ring carbon skeleton. It came from corrosion inhibitors, namely TTA in HFC. The peak at 721 cm−1 was attributed to the partial trisubstitution of H on the benzene ring. The results of infrared spectroscopy indicated that after the C–N cleavage on the benzene ring in methylbenzotriazole, a carbon film is formed by the adsorption of C of metal surface on TTA.

Mass loss of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel.

SEM images and EDS analyses of the surface after being immersed in HFC with two seawater concentrations for 240 h. (a) 45# steel with 0 % seawater, (b) 45# steel with 7 % seawater, (c) 17-4PH stainless steel with 0 % seawater, (d) 17-4PH stainless steel with 7 % seawater.

Infrared spectroscopy of C film on the surface of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel: (a) 0 % seawater, (b) 7 % seawater.

3.2 Potentiodynamic polarization

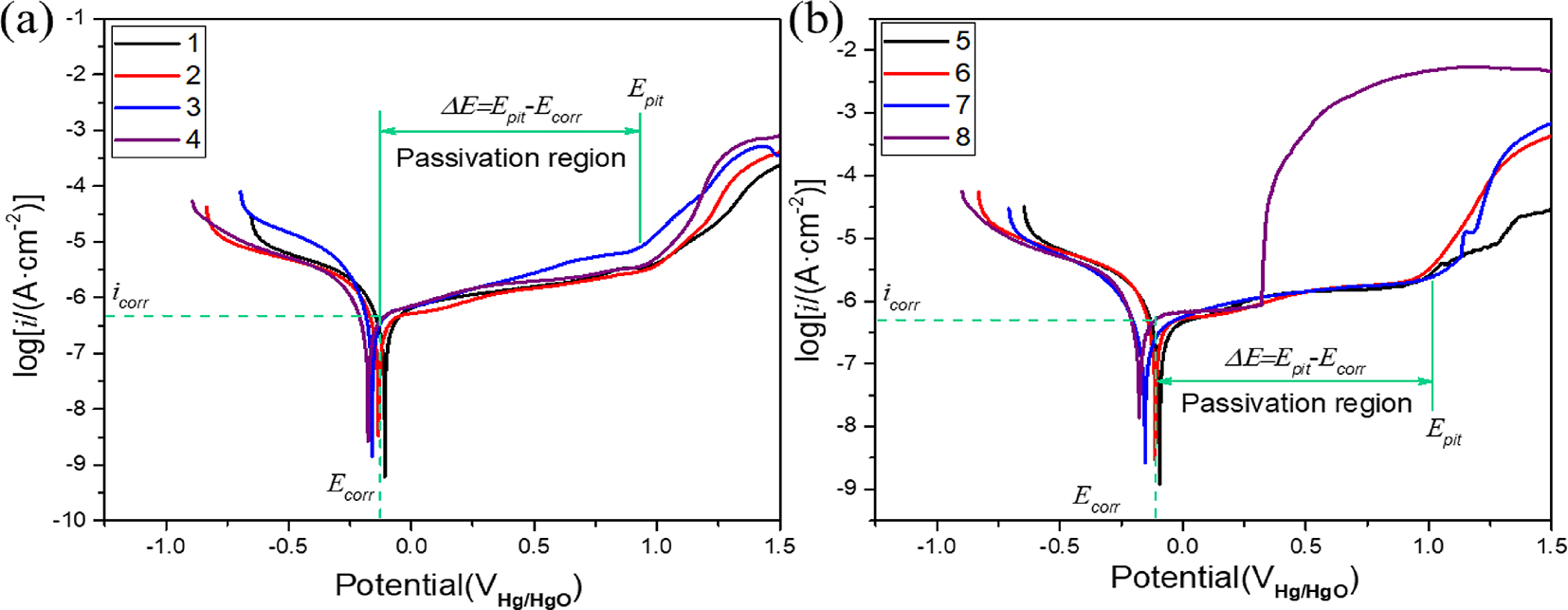

The potentiodynamic polarization curves of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC with four seawater contents are shown in Figure 4. The electrochemical parameters were calculated by Tafel extrapolation through the cathodic and anodic curves of the polarisation curves. Table 2 shows the calculated corrosion current densities (icorr), corrosion potentials (Ecorr), pitting potentials (Epit), passive ranges (ΔE = Epit − Ecorr), and corrosion rates (CR). There is no significant change in the cathode branch, which corresponds to oxygen reduction. The corrosion potential reflected the ease (or trend) of a metal losing electrons in an electrolyte. The corrosion current density reflected the rate of material corrosion, which referred to the amount of current per unit area. A high Ecorr value indicated a low corrosion tendency, while a low icorr value indicated a lower corrosion rate for the material. The corrosion potential of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel decreased with increased seawater content in HFC. This suggested that 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel corrosion tendency increased with increased seawater content in HFC. The corrosion current density of 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC of four seawater was as follows: 0 % > 3 % > 11 % > 19 %. The magnitude of corrosion current density reflected the corrosion rate, indicating that 17-4PH stainless steel had the lowest corrosion rate at 0 % seawater content. The corrosion characteristics of 45# steel under four seawater contents had similar characteristics, and its corrosion current density was as follows: 0 % > 3 % > 11 % > 19 %. These results indicated that seawater enhances the corrosiveness of HFC.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves of (a) 17-4PH stainless steel and (b) 45# steel at under four seawater content.

Due to the formation of a passivation film on 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC, evaluating the performance of the passivation films formed on 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC is a decisive factor in evaluating their corrosion resistance. The passivation film performance of metals was evaluated by the passivation range (Epit − Ecorr), the passivation current density, and the potential (Epit) when the current density suddenly increases after the passive film breakdown in the anode curve. The variation trend of the passivation region of 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC containing four contents of seawater was similar, indicating that the passivation film on the surface of 17-4PH stainless steel also has good stability under seawater intrusion. However, as the seawater content increases, the passivation range and Epit value increase, indicating a decrease in the corrosion resistance of the passivation layer after seawater intrusion. This meant that seawater had a corrosive effect on the passivation film. Passive current density represents the corrosion rate of the passivation zone. A low passive current density indicates a low passive dissolution rate. In HFC without seawater, 17-4PH stainless steel had the lowest passivation current density, indicating the best corrosion-resistant passivation layer. At the beginning stage of the passivation region, the passivation current density under 11 % seawater was less than that under 19 % seawater. As polarization progressed, the passivation current density of 19 % seawater was lower than that of 11 % seawater. This meant that the dissolution rate of the passivation layer under 11 % seawater was accelerated. However, with the breakdown of the surface passivation layer, the current density in 11 % seawater is lower than that in 19 % seawater. This indicates that the passivation layer at this time has stronger resistance to pitting corrosion. 45# steel had the most extensive passivation range, Epit value, and lowest passivation current density in HFC without seawater. This meant that the passivation layer of 45# steel in HFC without seawater had the best corrosion resistance performance. Under 19 % seawater, the Epit of 45# steel significantly decreased, indicating a significant decrease in corrosion resistance of the passivation layer of 45# steel. At the same time, the current density rapidly increased after the breakdown of the passivation layer, indicating that the passivation layer on the surface of the metal is rapidly destroyed and does not continue to adsorb and form. Epit can be used as a criterion for the resistance of passivation films to localized corrosion. The high Epit value reflected the strong resistance of the passivation film to localized corrosion. The primary degradation mode of the passivation film was local corrosion. In this case, the corrosion current density could not be used as the most suitable parameter for evaluating the corrosion performance of passivation films. The best parameters for evaluating passive film stability were pitting potentials (Epit) and passive range (Epit − Ecorr). The larger value of the two parameters best represented the resistance to local corrosion. Therefore, although the passivation current density of 17-4PH stainless steel in 11 % seawater was higher than that in 19 % seawater, it was still considered that the corrosion resistance of the passivation layer in 11 % seawater was more substantial than that in 19 % seawater. The observation results of the polarization curve indicated that each specimen in HFC exhibits a passive range of ∼1.10 V and a pitting potential of ∼0.9 V, indicating that the passivation film formed in HFC has high resistance to local corrosion. The Epit changes of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel had the same trend under four seawater contents, and seawater reduced the corrosion resistance of the passivation film. At the same time, the passivation film of 45# exhibited stronger corrosion resistance compared to 17-4PH stainless steel.

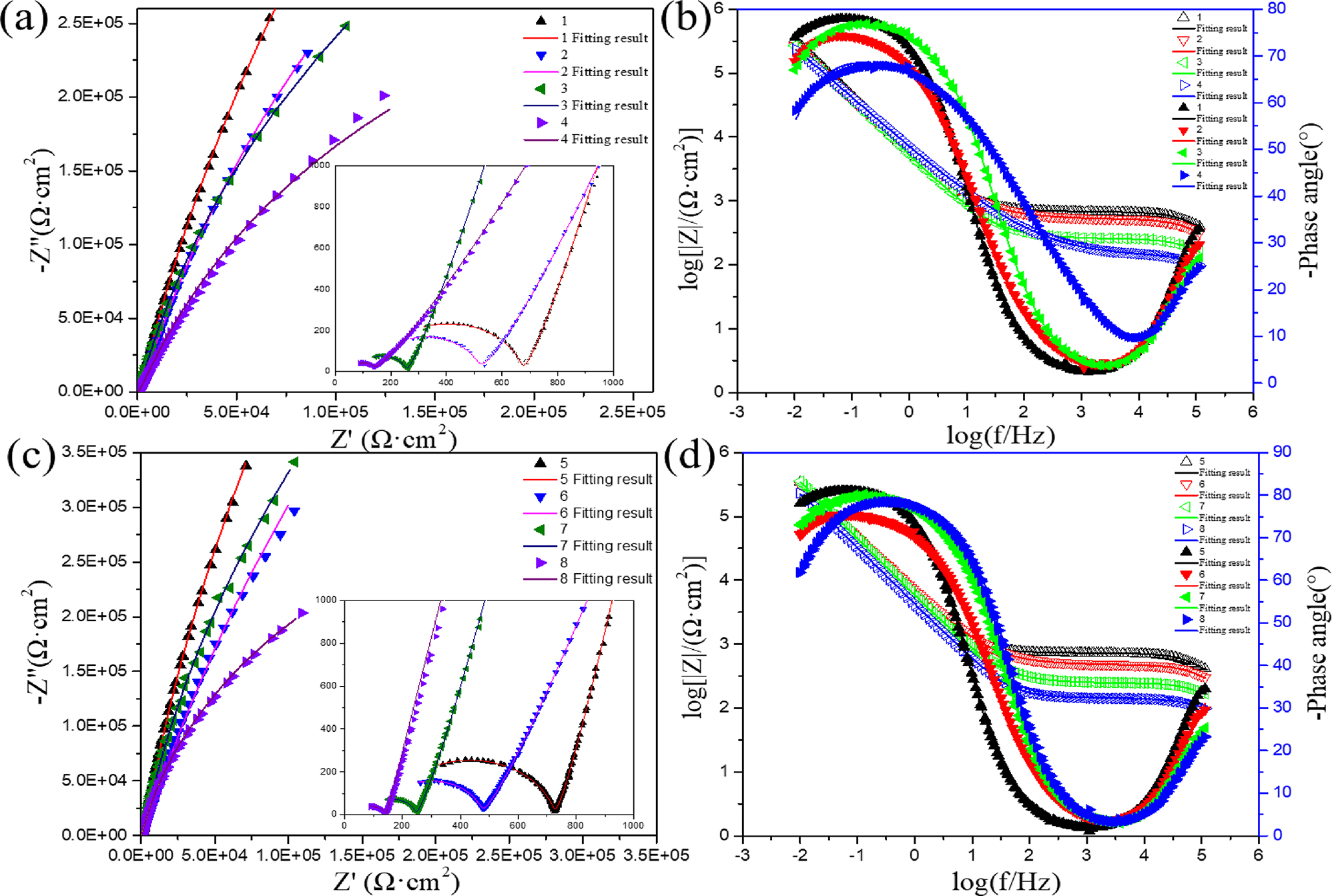

3.3 Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS measurements were carried out to further compare the corrosion behavior of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel in HFCs with four seawater content, and the results were displayed by Nyquist and Bode plots, as shown in Figure 5. There were two capacitive arcs in the Nyquist diagram of 17-4PH stainless steel in the mid to high-frequency region. The radius of the capacitive arc in the higher frequency region was small, which might be attributed to the double layer. The radius of the capacitive arc in the lower frequency region was larger, which might be attributed to the passivation layer. The radius of the two capacitive arcs decreased with the increase in seawater content, indicating that seawater reduced the corrosion resistance of 17-4PH stainless steel. The radius of the capacitance arc in the lower frequency region was much larger than that in, the higher frequency region, indicating that the impedance of the passivation layer is much greater than that of the double layer. Therefore, the passivation layer played a decisive role in the corrosion resistance of metals. A straight line with a slope ≈1 in the low-frequency region might be attributed to Warburg impedance. The Warburg impedance might be attributed to the blocking effect of the passivation film on ions. Figure 5b shows the Bode plot of the amplitude and phase of 17-4PH stainless steel. The peak phase angle in the high-frequency stage was attributed to the double layer. The values of |Z| and phase angle of the double layer decreased with the increase of seawater content, indicating that seawater reduces the impedance of the double layer. At the intermediate frequency stage, the capacitance behavior of the studied system showed a Bode slope of ≈ −1 and a phase angle of ≈ −80°, indicating a high impedance passivation layer formed on the surface of 17-4PH stainless steel. The phase angle of 17-4PH stainless steel was highest in HFC containing 0 % seawater. The maximum phase angle decreased with the increase in seawater content, indicating that seawater reduces the impedance of the passivation layer. In general, the impedance modulus at the lowest frequency (|Z|0.01 Hz) in the Bode diagram was another critical parameter for evaluating the corrosion resistance of materials. At low frequencies, the total impedance of the HFC environment without seawater was the highest.

CC.

Electrochemical parameters.

| Number | Ecorr (mV) vs. Hg/HgO | icorr (µA/cm2) | Epit (V) | ΔE = (Epit − Ecorr) (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −38.7 ± 1.2 | 0.353 ± 0.008 | 1.023 ± 0.015 | 1.062 |

| 2 | −148.3 ± 1 | 0.559 ± 0.01 | 0.913 ± 0.01 | 1.062 |

| 3 | −157 ± 1.3 | 0.569 ± 0.009 | 0.884 ± 0.012 | 1.041 |

| 4 | −159.2 ± 1 | 0.575 ± 0.008 | 0.878 ± 0.011 | 1.037 |

| 5 | −23.2 ± 1.2 | 0.266 ± 0.009 | 1.033 ± 0.011 | 1.056 |

| 6 | −102.7 ± 1.3 | 0.401 ± 0.008 | 0.936 ± 0.013 | 1.038 |

| 7 | −141.9 ± 1.1 | 0.515 ± 0.01 | 0.891 ± 0.013 | 1.033 |

| 8 | −150.1 ± 1 | 0.584 ± 0.008 | 0.337 ± 0.01 | 0.487 |

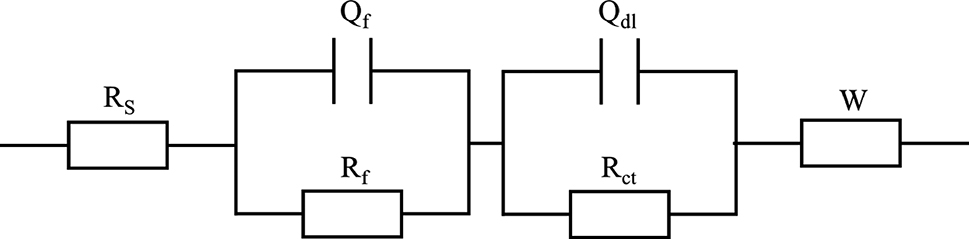

The equivalent circuit (Figure 6) was used to fit the EIS results to analyze the passive film quantitatively, and the fitted results are listed in Table 3. The electrical equivalent circuit (EEC) model of 17-4PH stainless steel consisted of solution resistance (Rs), passivation film resistance (Rf), charge transfer resistance (Rct), constant phase element (CPE), and Warburg impedance (W). Rs represented the resistance of the solution to anions. Rf represented the passivation film’s resistance to the specimen’s surface. Qf was the capacitance between the solution and the passivation layer. Rct represented the resistance between the specimen surface and the solution. Qdl was a double-layer capacitor. At low frequencies in the Nyquist plot, Warburg impedance is represented by a straight line with a slope of 45°. While maintaining the potential, the diffusion process of electroactive species to the electrode surface limits the reaction. It reduces the electrode kinetic speed, which leads to the appearance of Weber impedance. To overcome non-uniformity in the system, CPE replaced the capacitance in the circuit. The impedance ZCPE was defined by Equation (1).

The equivalent circuit models of 17-4PH stainless steel.

The fitting data obtained from equivalent circuits for 17-4PH stainless steel.

| Number | Rs (Ω.cm2) | Rf (kΩ.cm2) | Rct (Ω.cm2) | CPEf | CPEdl | W (Ω.s−0.5.cm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cf (μF.cm−2) | n f | Cdl (μF.cm−2) | n dl | |||||

| 1 | 136.8 | 2,905 | 532 | 59.621 | 0.899 | 3.34 × 10−3 | 0.909 | 1,331.026 |

| 2 | 131.6 | 1,620 | 378.1 | 75.787 | 0.88 | 4.65 × 10−3 | 0.914 | 3,101.737 |

| 3 | 80.75 | 1,248 | 171.6 | 68.126 | 0.884 | 1.08 × 10−3 | 0.913 | 1,119.069 |

| 4 | 52.66 | 829.3 | 80.73 | 66.036 | 0.899 | 2.43 × 10−2 | 0.948 | 892.061 |

Y0 is the proportionality factor, j is the imaginary unit, ω is the angular frequency, and n is the phase shift. The value of n is between 1 and 0 (when n = 1, CPE represents ideal capacitance; when n = 0, CPE represents the ideal resistance), which was a key parameter characterizing capacitive dispersion. By the Equations (3) and (4), the equivalent capacitances (C) of the CPEs were calculated, which took into account a normal distribution of EIS time constants for the surface films and a surface distribution for electrical double layer. The equation for calculating the effective capacitance of the electric double layer (C) was derived from Brug’s formula (Hirschorn et al. 2010).

As shown in Table 3, the decrease of Rs with the increase of seawater indicated that adding seawater enhances the conductivity of HFC, owing to the faster migration rate of Cl− in the solution. The enhancement of solution conductivity enhanced the activity of ions in the solution, thereby reducing the impedance of the solution. The values of Rf and Rct decreased with the increase in seawater content, which indicated that the addition of seawater enhances the corrosiveness of HFC. The value of Rf was much greater than Rs and Rct, which suggested that the passivation film’s corrosion resistance was much more excellent than that of the double layer and solution resistance. Therefore, the passivation film’s corrosion resistance determined the metal’s corrosion behavior in HFC. The value of Rf decreased with the increase of seawater content, which was caused by pitting corrosion of the passivation film by seawater. According to Orazem et al.’s research (Hirschorn et al. 2010; Orazem et al. 2013), by Equation (4), the thickness (δ) of the passive film can be evaluated.

where ε is the dielectric constant, ε0 is the permittivity of vacuum, and ε0 = 8.8542 × 10−14 F cm−1. Cf values were inversely proportional to δ, assuming that ε for all oxide layers of alloys are the same.

The thickness of the passivation film was lower than that of the double layer, which meant that the passivation layer was a porous structure that caused direct contact between the metal surface and the solution. After adding 3 % seawater, the thickness of the passivation film decreased, which may be owing to the corrosion of ions in seawater on the passivation film. The value of passivation Cf after adding seawater was more significant than that without seawater, which indicated fewer defects in the passivation film in the HFC without adding seawater, and the density and uniformity of the passivation film are better. This might be owing to pitting corrosion of the passivation film by ions in seawater. As the seawater content increases, the thickness of the passivation film decreases, and the Warburg impedance decreases, indicating that Cl− in seawater disrupts the protective effect of passivation film on pitting corrosion.

Figure 5c and d shows the Nyquist and Bode diagrams of 45# steel. Two capacitive arcs appeared in Nyquist, consistent with the Nyquist diagram of 17-4PH stainless steel. The capacitive arc at the high-frequency stage represented the double layer, while the capacitive arc at the intermediate-frequency stage represented the passivation layer. The straight lines appearing in the low-frequency stage represented the diffusion process. As the seawater content increased, the radii of the two capacitive arcs at medium and high frequencies decreased, indicating that seawater reduced the impedance of the double layer and passivation layer. Figure 5d shows the Bode plot of the amplitude and phase of 45# steel. The phase angle at the high-frequency stage represented the non-ideal capacitive behavior of the double layer. 45# steel had the highest impedance and phase angle in HFC without adding seawater, indicating the strongest corrosion resistance at the high-frequency stage. The peak phase angle at the intermediate frequency stage represented the non-ideal capacitive behavior of the passivation film. 45# steel had the highest impedance and phase angle at 0 % at the intermediate frequency stage, indicating that the passivation film has the strongest protective effect. 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel have similar EIS, therefore similar equivalent circuit (Figure 6) simulations are used. Table 4 shows the results of fitting the EIS using the equivalent circuit. The electrical equivalent circuit (EEC) model of 45# steel consisted of solution resistance (Rs), passivation film resistance (Rf), charge transfer resistance (Rct), constant phase element (CPE) and Warburg impedance (W). Rs decreased with the increase in seawater content, similar to the above research results. The value of Rct decreased with the rise in seawater content, which indicated that seawater reduces the impedance of the double layer. The value of Rf decreased with the increase of seawater content, indicating that seawater in HFC had a corrosive effect on the passivation film. As the seawater content increased, the thickness of the passivation film decreased, indicating that Cl− in seawater disrupts the protective effect of passivation film on pitting corrosion.

The fitting data obtained from equivalent circuits for 45# steel.

| Number | Rs (Ω.cm2) | Rf (kΩ.cm2) | Rct (Ω.cm2) | CPEf | CPEdl | W (Ω.s−0.5.cm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cf (μF.cm−2) | n f | Cdl (μF.cm−2) | n dl | |||||

| 5 | 140.5 | 4,568 | 580.9 | 56.674 | 0.922 | 3.29 × 10−3 | 0.914 | 797.448 |

| 6 | 124.4 | 3,351 | 343.3 | 72.892 | 0.863 | 5.1 × 10−3 | 0.936 | 2,154.244 |

| 7 | 88.29 | 2,428 | 154.3 | 54.336 | 0.907 | 1.13 × 10−2 | 0.948 | 1,056.301 |

| 8 | 51.91 | 648 | 87.63 | 69.286 | 0.899 | 1.75 × 10−2 | 0.919 | 393.236 |

A passivation film was formed on the surfaces of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel in HFC, effectively hindering the diffusion of ions to the surface. The Cf value of the passivation film on the surface of 45# steel was lower than that of 17-4PH stainless steel, which meant that the passivation film formed on the surface of 45# steel was denser and more uniform. Therefore, 45# steel has stronger corrosion resistance in HFC.

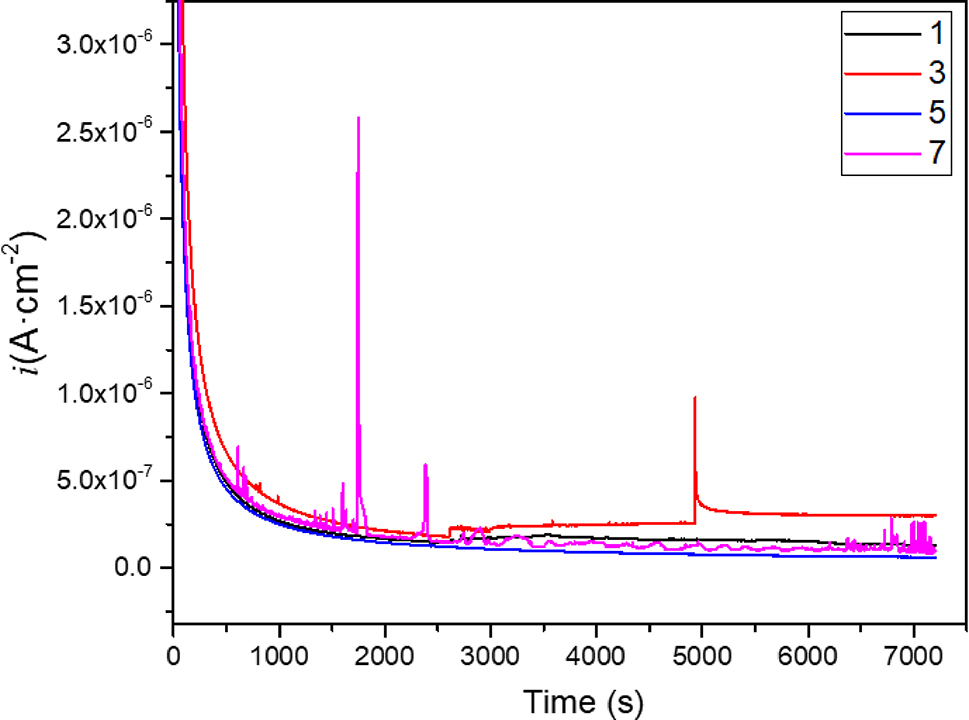

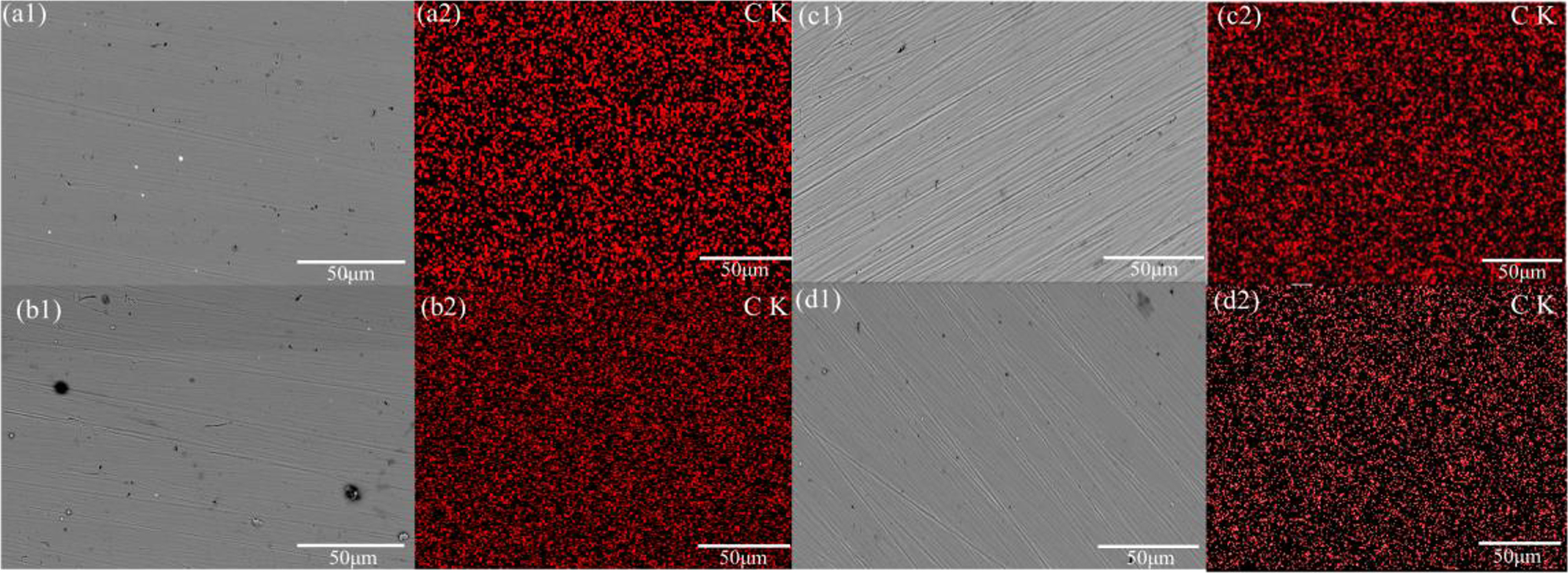

3.4 Passivation film analysis

The corrosion behavior of the passive film of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel in HFC containing two concentrations (0 and 11 %) of seawater was compared by potentiostatic polarization tests. Preparation of passivation film by potentiostatic polarizations at 0.5 VHg/HgO for 2 h. Figure 7 shows the results of the polarization curve. As time increases, the corrosion current density gradually reaches a steady state, indicating that the passivation film thickness maintains a dynamic balance owing to the growth and dissolution of the passivation film reaching equilibrium. The test results showed that the metal surface’s steady-state current densities under different conditions lay in the order of 5 > 1 > 7 > 3, which indicated that the passivation film on the surface of 45# steel in HFC without seawater shows the best corrosion resistance. In addition, the 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel surfaces in HFC containing 11 % seawater were subjected to metastable pitting corrosion events, indicating that seawater has a pitting effect on the passivation film. SEM and EDS mapping were used to analyze the morphology and composition of the passivation film, as shown in Figure 8. 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel showed no corrosion scars on the surface after potentiostatic polarization in HFC. This was owing to the protective effect of the passivation film. The EDS results indicated that the passivation film is composed of C. In HFC containing 11 % seawater, only a C film was observed on the metal surface, indicating that the C film is re-grown and repaired after being corroded by Cl−. No other components were observed in the carbon film formed in the HFC at four seawater concentrations, indicating that the carbon film effectively blocks the transfer of OH− and Cl−. This was the reason for the occurrence of Warburg impedance in the low-frequency stage. The EDS results indicated that the C element does not entirely cover the metal surface, indicating that the C film is a porous structure. The pore position is the location where the double layer is formed.

Potentiostatic polarization curves of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel in HFC with two concentrations of seawater (0 %, 11 %). The applied potential was 0.5 VHg/HgO.

SEM images and EDS mapping analyses of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel after 0.5 V constant potential polarisation tests. These images sequentially display the surface after passivation and EDS elemental mapping from the passivation film (red represents C, and black represents the matrix). (a1–a2) 17-4PH stainless steel (0 % seawater), (b1−b2) 17-4PH stainless steel (11 % seawater), (c1−c2) 45# steel (0 % seawater), (d1−d2) 45# steel (11 % seawater).

The infrared spectra of the C film on 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel are consistent with the results after immersion for 240 h (Figure 3). The structure of the passivation film after constant potential polarization was consistent with that immersed in seawater. The formation of the passivation layer was due to the adsorption of TTA in HFC by carbon elements on the metal surface. The above research results indicate that 45# steel adsorbed a denser carbon film owing to its higher carbon content than 17-4PH stainless steel.

3.5 Polarized surface analysis

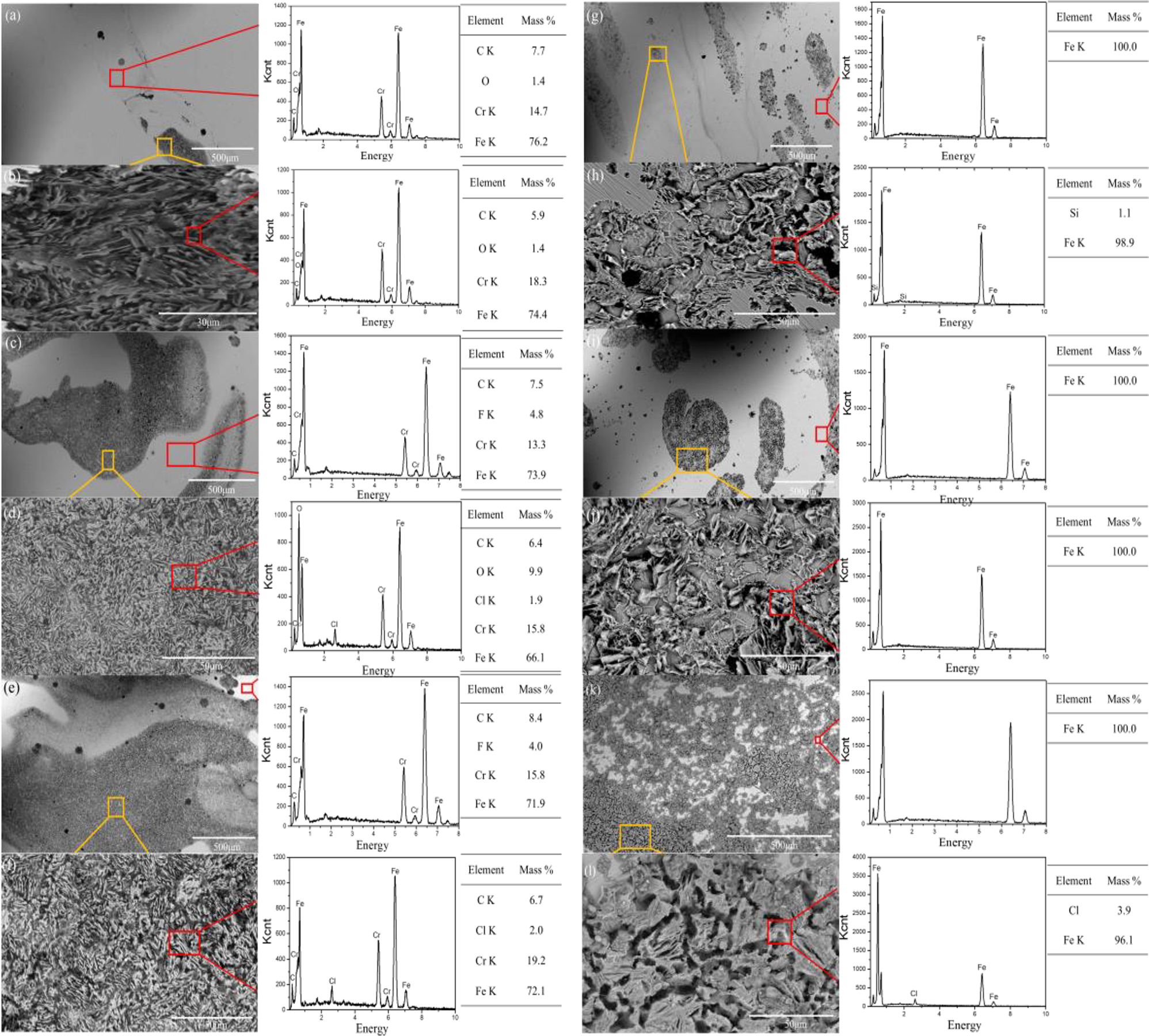

The SEM and EDS results of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel after potentiodynamic polarization in HFC with different seawater contents are shown in Figures 9 and 10. 17-4PH stainless steel showed no obvious corrosion scars on the surface after potentiodynamic polarization in HFC without seawater. This was thanks to the protective effect of the passivation film. The EDS results indicated that the C film on the surface of 17-4PH stainless steel had undergone pitting corrosion. After polarization, the surface of 45# steel still had a complete carbon film in HFC without seawater. At the same time, carbon deposition was observed on the surface, owing to the re-adsorption of carbon film after the passivation film was broken down. This also indicated that 45# steel has a stronger carbon film adsorption effect than 17-4PH stainless steel. 17-4PH stainless steel showed obvious pitting corrosion on the surface in HFC containing 3 % seawater. The preferential sites for corrosion appeared in the thin passive film at a continuous state of breakdown and repair based on the pitting corrosion mechanism (Frankel 1998). With the increasing potential, the pitting area expanded and grew. Cl− in seawater had a destructive effect on the passivation film, accelerating pitting corrosion during the polarization process. With the increase in seawater content, the pitting area on the surface of 17-4PH stainless steel expanded. When the seawater content was 11 and 19 %, the increase in Cl− content in the EDS of the surface pitting area proved the destructive effect of Cl− on the passivation film. Figure 11 shows the surface morphology and elemental analysis of 45# steel after polarization in a HFC containing 3–19 % seawater. Similarly, with the increase of seawater content, the pitting area on the surface of 45# steel expanded. The passivation film on the surface of 45# steel disappeared after polarization in HFC containing seawater, owing to the destructive effect of Cl− in seawater on the C film. When the seawater content was 19 %, the rapid corrosion surface of 45# steel disrupted the adsorption of C of the surface on the carbon film, leading to the rapid destruction of the passivation film. Owing to the higher corrosion resistance of 17-4PH stainless steel compared to 45# steel in seawater. Therefore, the surface corrosion scars of 17-4PH stainless steel were less than those of 45# steel in HFC with high seawater content. The surface after corrosion, it was challenging to adsorb carbon film to protect the surface, so 17-4PH stainless steel exhibits stronger corrosion resistance.

SEM images and EDS analyses of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel after the potentiodynamic polarization tests. (a) 17-4PH stainless steel (0 % seawater), (b and c) 45# steel (0 % seawater).

SEM images and EDS analyses of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel after the potentiodynamic polarization tests. (a, b) 17-4PH stainless steel (3 % seawater), (c, d) 17-4PH stainless steel (11 % seawater), (e, f) 17-4PH stainless steel (19 % seawater), (g, h) 45# steel (3 % seawater), (i, j) 45# steel (11 % seawater), (k, l) 45# steel (19 % seawater).

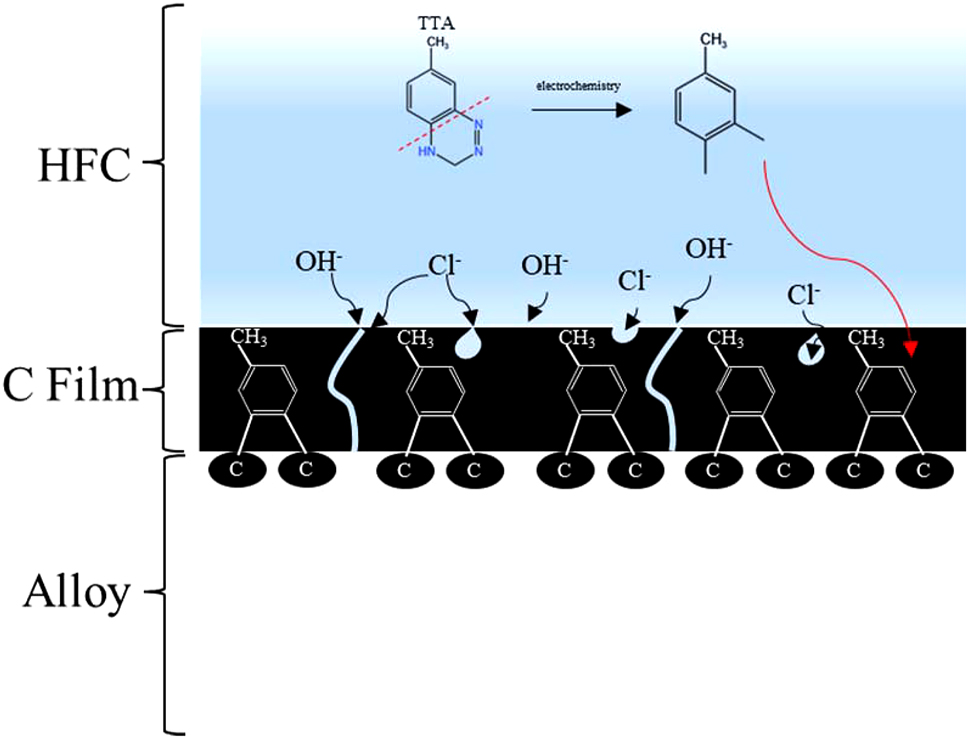

Schematic diagram of corrosion mechanism for alloys immersed in HFC containing seawater.

4 Discussion

The corrosion mechanism of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel in HFC containing seawater is shown in Figure 11. The corrosion inhibitor TTA in HFC undergoes C–N cleavage on the benzene ring under electrochemical action. Subsequently, a carbon film was formed on the surface of 45# steel and 17-4PH stainless steel owing to the adsorption of C element on the benzene ring carbon skeleton of TTA. Carbon film could effectively hinder the migration of ions to the matrix, thus possessing strong corrosion resistance. 45# steel had a more corrosion-resistant carbon film than 17-4PH stainless steel, which might be owing to the higher carbon content in 45# steel compared to 17-4PH stainless steel, which adsorbed more benzene ring carbon skeleton. The carbon film formed on the metal surface was not utterly dense and had few pores. Owing to the high density of the carbon film on the surface of 45 # steel, there are fewer pores on the surface, resulting in a higher impedance of the double layer. After seawater intrusion into HFC, Cl− caused pitting corrosion on the passivation layer.

5 Conclusions

This paper investigated the electrochemical corrosion behavior of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel in HFC with four concentrations of seawater (0 %, 3 %, 11 %, 19 %). The research results obtained were as follows:

A corrosion-resistant carbon film was formed on the surfaces of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel through the adsorption of TTA by C of metal surface in HFC containing seawater, which can effectively hinder the diffusion of ions to the metal surface, thereby protecting the metal surface from corrosion.

45# steel exhibited stronger corrosion resistance in HFC compared to 17-4PH stainless steel, owing to the denser C film formed on the surface of 45# steel due to its high carbon content.

As the seawater content increases, the corrosion resistance of 17-4PH stainless steel and 45# steel decreases. Seawater enhances the corrosion performance of HFC by enhancing its conductivity and pitting the C film.

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: No. 52235001, 52075192

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank for the technical support from the Experiment Center for Advanced Manufacturing and Technology in the School of Mechanical Science & Engineering of HUST. They also acknowledge the technical support from the Technology Analytical & Testing Center of HUST.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Yipan Deng: Conceptualization. Runzhou Xu: Formal analysis, Writing - Original draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Yinshui Liu: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Xianchun Jiang: Investigation.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 52235001, 52075192).

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

Al-Malahy, K.S. and Hodgkiess, T. (2003). Comparative studies of the seawater corrosion behaviour of a range of materials. Desalination 158: 35–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0011-9164(03)00430-2.Search in Google Scholar

Ding, H., Yang, X., Xu, L., Li, M., Li, S., and Xia, J. (2019). Tribological behavior of plant oil-based extreme pressure lubricant additive in water-ethylene glycol liquid. J. Renewable Mater. 7: 1391–1401, https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2019.07207.Search in Google Scholar

Fekry, A.M. and Fatayerji, M.Z. (2009). Electrochemical corrosion behavior of AZ91D alloy in ethylene glycol. Electrochim. Acta 54: 6522–6528, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2009.06.025.Search in Google Scholar

Frankel, G. (1998). Pitting corrosion of metals: a review of the critical factors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 145: 2186–2198, https://doi.org/10.1149/1.1838615.Search in Google Scholar

Hirschorn, B., Orazem, M.E., Tribollet, B., Vivier, V., Frateur, I., and Musiani, M. (2010). Determination of effective capacitance and film thickness from constant-phase-element parameters. Electrochim. Acta 55: 6218–6227, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2009.10.065.Search in Google Scholar

Ma, K., Wu, D., Xu, R., Pang, H., and Liu, Y. (2022). Experimental investigation and theoretical evaluation on the leakage mechanisms of seawater hydraulic axial piston pump under sea depth circumstance. Eng. Failure Anal. 142: 106848, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106848.Search in Google Scholar

Malik, A.U., Siddiqi, N., and Andijani, I.N. (1994). Corrosion behavior of some highly alloyed stainless steels in seawater. Desalination 97: 189–197, https://doi.org/10.1016/0011-9164(94)00086-7.Search in Google Scholar

Orazem, M.E., Frateur, I., Tribollet, B., Vivier, V., Marcelin, S., Pébère, N., Bunge, A.L., White, E.A., Riemer, D.P., and Musiani, M. (2013). Dielectric properties of materials showing constant-phase-element (CPE) impedance response. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160: C215–C225, https://doi.org/10.1149/2.033306jes.Search in Google Scholar

Quan, W., Liu, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, X., and Liu, C. (2016). Scale model test of a semi-active heave compensation system for deep-sea tethered ROVs. Ocean Eng. 126: 353–363, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2016.09.024.Search in Google Scholar

Su, T., Song, G., Zheng, D., Ju, C., and Zhao, Q. (2021). Facile synthesis of protic ionic liquids hybrid for improving antiwear and anticorrosion properties of water-glycol. Tribol. Int. 153: 106660, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2020.106660.Search in Google Scholar

Tian, Y.Q., Liu, S., Long, J.C., Chen, W., and Leng, J.X. (2022). Analysis and experimental research on efficiency characteristics of a deep-sea hydraulic power source. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10: 35, https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse10091296.Search in Google Scholar

Totten, G.E. (2011). Handbook of hydraulic fluid technology, 2nd ed.. CRC, Boca Raton.10.1201/b11225Search in Google Scholar

Wang, L., Zhou, T., and Liang, J. (2012). Corrosion and self-healing behaviour of AZ91D magnesium alloy in ethylene glycol/water solutions. Mater. Corros.-Werkstoffe und Korrosion 63: 713–719, https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.201106131.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, J., Wang, J., Li, C., Zhao, G., and Wang, X. (2014). A study of 2,5-dimercapto-1,3,4-thiadiazole derivatives as multifunctional additives in water-based hydraulic fluid. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 66: 402–410, https://doi.org/10.1108/ilt-11-2011-0094.Search in Google Scholar

Xiong, L.P., He, Z.Y., Han, S., Tang, J., Wu, Y.L., and Zeng, X.Q. (2016). Tribological properties study of N-containing heterocyclic imidazoline derivatives as lubricant additives in water-glycol. Tribol. Int. 104: 98–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2016.08.031.Search in Google Scholar

Zavieh, A. and Espallargas, N. (2017). The effect of friction modifiers on tribocorrosion and tribocorrosion-fatigue of austenitic stainless steel. Tribol. Int. 111: 138–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2017.03.008.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, G.A., Xu, L.Y., and Cheng, Y.F. (2008). Mechanistic aspects of electrochemical corrosion of aluminum alloy in ethylene glycol-water solution. Electrochim. Acta 53: 8245–8252, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2008.06.043.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, X.G., Liu, X., Dong, W.P., Hu, G.K., Yi, P., Huang, Y.H., and Xiao, K. (2018). Corrosion behaviors of 5A06 aluminum alloy in ethylene glycol. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 13: 10470–10479, https://doi.org/10.20964/2018.11.64.Search in Google Scholar

Zheng, L., Neville, A., Gledhill, A., and Johnston, D. (2010). An experimental study of the corrosion behavior of nickel tungsten carbide in some water-glycol hydraulic fluids for subsea applications. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 19: 90–98, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-009-9416-8.Search in Google Scholar

Zheng, D.D., Su, T., and Ju, C. (2022). Influence of ecofriendly protic ionic liquids on the corrosion and lubricating properties of water-glycol. Tribol. Int. 165: 107283, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2021.107283.Search in Google Scholar

Zuo, H.Y., Wang, L., Gong, M., Zheng, X.W., Liu, C.H., Fan, J.L., and Liu, F. (2021). Corrosion behavior of ZrCrMoNb high-entropy alloy coating in ethylene glycol solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 16: 17, https://doi.org/10.20964/2021.01.29.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Why is the modified wedge-opening-loaded test inadequate for characterizing gaseous hydrogen embrittlement in pipeline steels? A review

- Research progress on zirconium alloys: applications, development trend, and degradation mechanism in nuclear environment

- Original Articles

- Effect of seawater intrusion in water-glycol hydraulic fluid on the electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel and stainless steel

- Durability of a thermally decomposed iridium(IV) oxide–tantalum(V) oxide coated titanium anode in aqueous ammonium citrate

- Microscopic analysis of the destruction of passive film on stainless steel caused by sulfide in simulated cooling water

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Why is the modified wedge-opening-loaded test inadequate for characterizing gaseous hydrogen embrittlement in pipeline steels? A review

- Research progress on zirconium alloys: applications, development trend, and degradation mechanism in nuclear environment

- Original Articles

- Effect of seawater intrusion in water-glycol hydraulic fluid on the electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel and stainless steel

- Durability of a thermally decomposed iridium(IV) oxide–tantalum(V) oxide coated titanium anode in aqueous ammonium citrate

- Microscopic analysis of the destruction of passive film on stainless steel caused by sulfide in simulated cooling water