Abstract

This article highlight and discuss the complex situation when deaf adults who are emergent readers learn Swedish Sign Language (STS) and Swedish in parallel. As Swedish appears primarily in its written form, they also have to develop reading and writing skills. Study data comes from ethnographically created video recordings of classroom interaction and interviews with teachers and participants. The analysis reveals that while the migrants successively learn basic STS for interacting with other deaf people, learning Swedish takes a different path. The migrants struggle with learning basic reading and writing skills, vocabulary, and grammar. Furthermore, the instruction is highly repetitive, but unstructured and sprawled, using STS to explain and connect signs with written equivalents. The teachers testify in interviews that it seems very difficult for the emergent readers to learn Swedish on a level good enough to cope in Swedish society, which, in turn, puts them in a vulnerable position.

1 Introduction

But then we have the other group … They develop so much more slowly. They learn STS and we try with words and sentences, everyday language, but I find that they forget and forget all the time. Even if they can sign, they forget Swedish all the time.

In this way, the teacher, Elisabeth, describes her experience of teaching written Swedish to deaf adult migrants. When they arrive in Sweden, many deaf adult migrants learn to read and write for the first time ever, i.e. they are emergent readers. Learning a second language in adulthood is demanding for many people, both deaf and hearing, and learning the technique of reading and writing, print literacy, makes learning even more challenging. For deaf people around the world, this situation is further complicated because most of them have had limited exposure to language and schooling during their childhood. In recent years, some scholars have discussed such delayed language acquisition in terms of language deprivation (Gulati 2018; Hall 2017). This, in turn, can affect the ability of deaf people to participate in society on an equal basis and can lead to greater difficulties in acquiring academic skills and print literacy, as these are cognitively demanding.

The literature on deaf students’ reading and writing achievements gives a varied picture of their success rate from various perspectives. Some studies have stressed the importance of promoting sign language development in deaf children to facilitate their print literacy development, and several scholars have suggested that print language should be acquired as a second language (e.g. Howerton-Fox and Falk 2019; Hrastinski and Wilbur 2016; Svartholm 2008). However, most literature has focused on school-aged deaf students, not adults and regarding deaf adult migrants in particular, our knowledge is limited. However, from hearing adult education, we know that many migrants struggle with learning print literacy, particularly those who are emergent readers.

However, it is essential to mention that many deaf people, despite their varying linguistic and educational backgrounds, are multimodal and multilingual. Even those with limited exposure to language probably meet a variety of languages in their everyday lives and use a range of strategies to communicate. They use a large repertoire of different languages and modalities at home, at school, at work, etc., in a more blurring and flexible way as opposed to more traditional notions of “separate” bilingualism, in which the languages are used separately (cf. Duggan and Holmström 2022; Moriarty Harrelson 2019). In recent years, the flexible and multimodal language use of deaf people has been described in terms of translanguaging (see De Meulder et al. 2019).

However, many deaf people worldwide lack formal schooling because their home countries do not offer deaf schools or other educational settings suitable for them. This study focuses on deaf migrants with no or limited educational background who have not learned print literacy before they arrived in Sweden and are therefore emergent readers. When they arrive in Sweden, they are required to inform the authorities about their reasons for coming to Sweden and argue for receiving a residence permit. This requirement can prove difficult for emergent readers with limited language proficiency. They mainly have to rely on Swedish Sign Language (STS) interpreters when communicating with the authorities, even though this is a language that they have not yet mastered. They also need to handle written documents regarding a range of information, applications, signatures, government services, etc., necessary for everyday life and for being issued with a residence permit. However, because they are emergent readers, they cannot read texts in either their home country’s language or Swedish. Thus, upon their arrival, many deaf adult migrants are offered education in STS and Swedish at different schools and programmes funded by the Swedish government. They therefore have to learn two new languages, as well as print literacy, in parallel.

Given the context, it is crucial to enhance our understanding of the learning process of deaf emergent readers in terms of print literacy. To this end, this study aims to generate new insights into the approaches adopted by teachers for teaching writing techniques, vocabulary training, and developing reading skills among migrants, in the context of four folk high schools (independent adult education colleges) in Sweden. The study focuses on identifying common patterns and recurring exercises employed by teachers, as well as the challenges they face. Ultimately, the study aims to contribute to the improvement of teaching methods, with a view to achieving better outcomes in the development of print literacy among emergent readers who are deaf and migrants.

2 Emergent reading

Many migrants move from a home country where literacy skills are not required, or are required to a lesser extent. Some migrants also come from cultures whose language has no written form. However, when they arrive in a Western country, they meet a culture where reading and writing skills are required to fully participate in society, the workplace, access social services, etc. This may be a totally new experience for many migrants, especially those who have never previously learned how to read and write (Holmström and Sivunen 2022).

In general, for adult second language learners, learning to read and write in any language is normally a challenge. However, for those with no previous knowledge of reading and writing, the challenge is obviously greater when they have to learn both a new language and develop print literacy skills (Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014). In a Swedish study, Dahlstedt et al. (2019) state that among migrants who are emergent readers, only a few can acquire higher levels of reading and writing proficiency.

Learning to read and write often requires formal teaching (Wedin et al. 2016). Sweden offers migrants several courses in Swedish (see, e.g. Duggan et al. 2023; Fejes 2019) and the teachers have very different experiences regarding background and education. For example, many teachers in upper secondary schools and folk high schools (folkhögskolor, independent adult education colleges) have teaching degrees and many of them also have knowledge of teaching Swedish as a second language, although they may not be migrants themselves or have experience of learning Swedish as a second language (Fejes et al. 2018b). In contrast, teachers in study circles such as the Workers’ Educational Association (ABF), a Swedish non-governmental and politically independent organisation, are often from migrant backgrounds themselves. They bring experience and understanding that are valuable for new learners of Swedish. However, many of these teachers do not have teaching degrees or have limited experience of teaching (Fejes et al. 2018a). In addition, most educators have personal experience of learning print literacy in childhood but often lack experience and knowledge of teaching learners who lack formal schooling or are learning a new language with no previous knowledge of print literacy (Vinogradov and Liden 2008). This may bring challenges in teaching emergent readers.

The literature and studies on adult emergent readers mainly refer to the importance of the spoken form of the language. Oral skills and phonological awareness of the new language are deemed to be required in order to develop print literacy (see e.g. Kolinsky et al. 2018; Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014; Vinogradov and Bigelow 2010; Wedin et al. 2016). For example, Kolinsky et al. (2018) developed a literacy course based on a phonetic approach and concluded that by using this approach, illiterate adults could learn to decode written texts in three months. This particularly applies to languages with sound-based writing systems, such as Swedish. Wedin et al. (2016) mention that as Swedish has a high grapheme-phoneme correspondence, it is important that teachers have knowledge of both the writing system and Swedish phonology. The authors further mention that most adult students are expected to master spoken communication in any language. Thus, the relationship between speech and writing is important for written language development. This is illustrated by Swedish teaching materials for adults who are learning Swedish for the first time, which is initially largely based on oral ability and oral training using different writing exercises.

However, the focus on oral skills and phonological awareness does not apply to deaf migrants, of which many have limited or no hearing and therefore cannot similarly access speech as hearing migrants. Thus, deaf people in general have a different path to developing print literacy, which will be further described below.

3 Deaf people’s path to print literacy

Research on print literacy in deaf individuals has been mostly centered on children. While we are aware that the focus of this study is on adult learners, we are summarising some key concepts from previous research on print literacy of deaf children and adolescents. In the major research on deaf people’s literacy development, there has been a recurring discussion about their challenges. Often, the lack of access to spoken language has been suggested as an obstacle to developing literacy skills. However, this does not explain why some deaf students become successful readers. It is well documented that deaf children’s early exposure to sign language is critical for developing proficient literacy skills. Those children who grow up in homes where sign language is the main mode of communication (i.e. in signing families) or who are enrolled in a deaf school where sign bilingual education is provided, have a natural context in which to use sign language for socialisation and learning. This calls for a multimodal and multilingual approach to deaf people’s literacy development. Here we could assume the same may be true for deaf adults acquiring literacy.

Print literacy development differs significantly between deaf and hearing individuals. The development of print literacy requires a demanding cognitive process for deaf individuals that is distinct from that of hearing individuals. Learning to read and write for the first time is often equivalent to learning a new language for many deaf individuals. As a result, the approach to print literacy does not involve linking print with sounds as it does for hearing individuals (Caldwell-Harris 2021; Hoffmeister and Caldwell-Harris 2014). Instead, the approach to print literacy entails the use of different learning strategies, such as visual-based decoding strategies, as opposed to the commonly used sound-based strategies (e.g., Kuntze et al. 2014). Additionally, it is suggested that teaching should follow a second language teaching approach (Koulidobrova et al. 2018; Svartholm 2008). Moreover, numerous studies have highlighted the significance of sign language proficiency in the acquisition of spoken or written language (e.g., Strong and Prinz 1997; Chamberlain and Mayberry 2008). Additionally, certain studies have emphasized the crucial role of sign language phonological development in reading development (e.g., McQuarrie and Parrila 2014) as a means of building cognitive phonological representations.

Based on the previous research on language acquisition summarised in Caldwell-Harris (2021: 84), it is suggested that written languages cannot be fully acquired without fluency in a first language. This is supported by studies confirming that fluency in a language is said to be an essential prerequisite for learning a new language, especially in print. For those people who are not fluent in a first language, the only recommendation is to “remediate language deprivation” (Caldwell-Harris 2021: 84). Caldwell-Harris (2021) also mentions that “when there is no fluent L1, there is no large storehouse of vocabulary items to be mapped to printed words, there is no model of linguistic structure to be used as a source domain for analogical explanations, no fluent language to be used to discuss motivation, career aspirations and the future long-term benefits of literacy” (p. 84). Hoffmeister and Caldwell-Harris (2014) mention the importance of deaf people knowing a natural sign language first, before learning a written language.

3.1 The importance of memory

Another part of the challenge of learning a new language through print have been reported to be associated with memory. Deaf people not only need to memorise written words, but also their sign equivalents (including sign variants and concepts/meanings, as well as overlapping signs for the same concepts). This is more cognitively demanding because the “[r]eading process can cause cognitive overload in signing Deaf readers, as the reader’s working memory is tasked not only with decoding but with creating a ‘mental visualization’ (p. 40) of the printed word’s sign equivalent” (Falk et al. 2020 referring to Easterbrooks and Huston 2008, p. 40).

In order to achieve reading fluency, automatic word identification processes are necessary. Words that are highly frequent and thus (should be) automatically recognised are called “sight words”. In US English, a sight word vocabulary list has been established comprising the most frequently occurring words, e.g. the Dolch and Fry word list (Dolch 1936; Fry 1980). Readers familiar with these words can easily recognise them when reading (Also see 3.2.2, for further application of high-frequent/sighted words in pedagogical contexts). Basic print vocabulary allows readers to focus on understanding the words instead of decoding them, as the decoding process requires greater working memory capacity. Thus, knowing more sight words frees the working memory from decoding, and resources are given to comprehension work instead (Falk et al. 2020).

3.2 Pedagogical strategies

In a formal second language learning context, teachers constantly try to find different pedagogical strategies to help students progress in their learning. For example, teachers make different improvements in language vocabulary instruction. However, teachers of the deaf constantly have to formulate their own strategies to teach their students because much of the literature is sound-based, and curricula are developed with hearing students in mind. Below, we will describe three core strategies in deaf classrooms found in the literature that will be connected with our findings later.

3.2.1 Visually based strategies

In classrooms with deaf students, visually-based strategies are essential. Kuntze et al. (2014) propose a change from a more traditional monolingual and linear text-based literacy training to a more multidimensional and multilingual approach, building on the students’ multilingual skills. They suggest a model that uses (American) sign language as an essential component. The model includes visual engagement with training to use eye-gaze, semi-circle seating and increasing visual awareness. Sign language is considered a crucial basis for meaningful interaction in connection with print literacy, for example, through shared reading, metalinguistic discussions, use of fingerspelling, etc. The model also includes awareness of deaf culture and role models, i.e. the visual way of being is considered important to make students conscious about self-identification and to develop a meta-awareness of their own languages and learning. Also, sign bilingual educational materials in video format are important to teaching. Media such as supplementary material, together with social interaction with a teacher, enhance the students’ learning.

3.2.2 Vocabulary learning

Vocabulary training is considered an important initial stage of learning a new language. Beck et al. (2013) argue that “a large and rich vocabulary is the hallmark of an educated individual” (p. 1). They argue that robust vocabulary instruction is needed, i.e. “directly explaining the meanings of words along with thought-provoking, playful, and interactive follow-up” (p. 3). They explain that children commonly learn their early words from the oral environment, i.e. they initially acquire vocabulary through oral communication in specific oral contexts. However, at a later age, children learn new vocabulary in written contexts and it is much harder because “written context lacks many of the features of oral language that support learning new word meanings, such as intonation, body language, and shared physical surroundings” (p. 5). Learning language from texts is challenging as a learner needs to have a vocabulary of between 3,000 and 5,000 words to be able to understand and interpret new words in a written text (Coady and Huckin 1997), and they have to read widely enough, including a range of different texts containing both familiar and unfamiliar words. Unfortunately, few learners engage in such wide reading activities.

Beck et al. (2013) mention oral language as a bridge to reading and writing, but their idea of robust vocabulary instruction can also be applied to deaf learners. For example, elements of robust vocabulary instruction can be found in “The Bedrock Literacy Curriculum”, which provides teachers of deaf and hard-of-hearing students with principles and strategies for effective literacy instruction (Di Perri 2021). Di Perri highlights her own experiences of working with students’ vocabularies where she created word lists from different themes or books her students should read. She states: “[t]here was no structure, sequence, or connectedness to this compilation of vocabulary items. Two major problems emerged: the students neither retaining the vocabulary nor recognizing them if the lexical item showed up during reading instruction at a later date” (p. 136, italics in original). Di Perri found that the students were unable to recognise and comprehend highly frequent words in print and that they lacked knowledge of simple lexical words, i.e. they had another point of departure than the hearing students. Di Perri suggests that one of the limitations of her previous strategy to teach vocabulary was that she and her students only worked on a word list for one week and then continued with new themes and new words, and the previous words were rarely in focus again. The students did not discuss them or frequently encounter them in different texts. Falk et al. (2020), who examined the Bedrock Literacy Curriculum, found that it was effective to teach words with concrete and meaningful meaning (not functional words), taken from the Fry high-frequency word list (Fry 1980). It was also necessary to ensure that the words were stored in their long-term memories (see above). Thus, tests were made to examine whether the students remembered the words after a while. The words they did not remember should be more trained until they were stored in their memory. Thus, the students might initially learn the same words, but after a while, the lists are more personalised due to the students’ differences in memorising words.

In their learning model, Hoffmeister and Caldwell-Harris (2014) mention the importance of using mapping strategies in vocabulary instruction. This means that new written words are mapped to signs the children already know interactively. For example, when introducing a new English print word such as dog, the teacher (or another adult) can sign DOG and point to the written word dog and also fingerspell it. By doing this, the students can depart from their knowledge of the sign DOG and its meaning and connect it with the written word.

3.2.3 Transliteration and translation

Di Perri (2021) highlights that there is a difference between attending to words at a surface level or a deep level, whereby the former means just recognising the word equivalents in two languages when reading a sentence, and the latter means gaining an understanding of the meaning of the word or sentence. The surface-level attainment is closely associated with transliteration, a process whereby a second language learner just connects a sentence in one language word-for-word with another. This usually results in incorrect sentences and different meanings in the transliterated language. In DHH education, it is common to engage in tasks that involve the students reading a written text and signing it word-for-word, inspired by the reading aloud activity that is usual in hearing classrooms. However, such a method does not guarantee comprehension. When just choosing a sign equivalent to a written word, the structure and meaning can become entirely different and unintelligible (cf. Hoffmeister and Caldwell-Harris 2014). Thus, transliteration is not a reliable way of developing reading comprehension. Instead, the students need to understand the sentence at a deep level, i.e. learn to translate the content in a written text or sentence into real sign language. However, translation requires a well-developed knowledge of sign language, and the students need to have sufficient knowledge of this language before they can work with translations. In the Bedrock Literacy Curriculum, this can be trained through the teacher creating single sentences with words that have already been learned, and the students reading them, thinking about them, trying to understand them, and then signing the same meaning in sign language.

4 This study

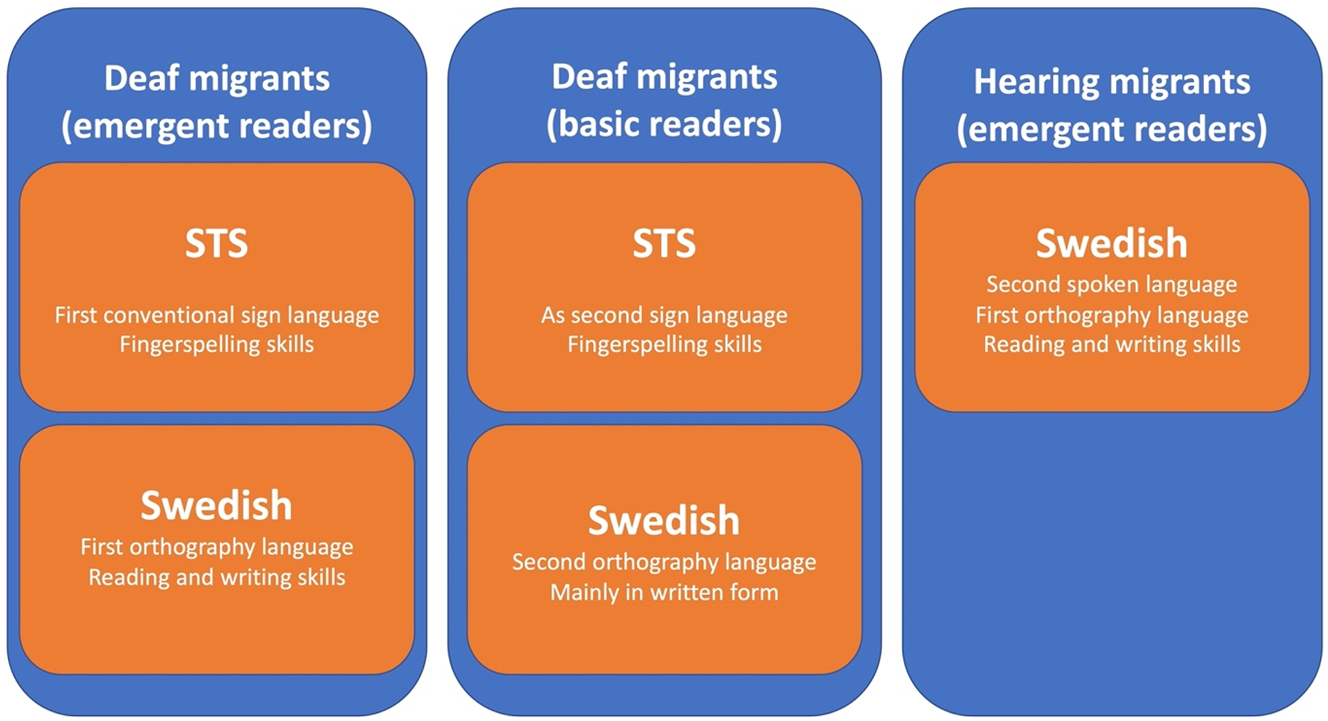

The case of deaf adult emergent readers is particularly compelling against the aforementioned backgrounds. Upon arrival in a Western country such as Sweden, they face numerous challenges, including the acquisition of Swedish sign language (STS) and the Swedish language itself. Additionally, Swedish can only be learned in written form, making the development of print literacy a necessity for successful integration into the Swedish community. Furthermore, they must learn various sub-skills, such as STS fingerspelling and Swedish orthography (see Figure 1), which adds to the complexity of the task.

A comparison of learning tasks of deaf and hearing migrants upon arrival in Sweden. Alt text: Hearing migrants who are emergent readers learn Swedish as a second spoken language and as their first written language. Deaf migrants who are emergent readers learn Swedish Sign Language as their first conventional language and Swedish as their first written language. Other deaf migrants with basic reading skills learn Swedish Sign Language as a second sign language and Swedish as their second written language.

This study is part of an ongoing larger research project funded by the Swedish Research Council (2019-02115), about the multilingual situation of deaf adult migrants in Sweden. Four folk high schools (independent adult education colleges) with programmes for deaf adult migrants located in different places around Sweden participated in this study, allowing the research team to participate in the school setting and create data. The project was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2020-02865) and all involved participants and staff were informed about the project and have given their written consent to participate in the study (see Duggan and Holmström 2022 for a description of designing consent forms for migrants with limited or no written language skills).

4.1 Method and material

Following an ethnographic approach, the research team used observations and interviews to examine the learning context at the different schools. The classes were followed in different lessons during the whole school day, and the classroom interaction was documented through video recordings and field notes. The research team visited the schools several times on different days over four semesters (although the second semester was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic). A total of approximately 45 h of video-recorded classroom interaction were created in the project. In the classroom interaction, a total of 65 participants were included (48 migrants and 17 staff).

In addition to interaction data, interviews were also conducted (all through Swedish Sign Language) with both deaf migrant participants and their teachers. The background interviews comprised approximately 13 h of video recordings and focused on the migrants’ backgrounds and previous experiences, for example, their country of origin, how their families look like, which language(s) they use, and their previous education. However, it is important to mention that conducting the participant interviews could be challenging at times because it depended on the participants’ skills in STS (and other languages), their understanding of their own background and current situation, and their ability to share their experiences. A total of 43 deaf migrants were interviewed, of which 17 were men and 26 were women. Their age ranged from 18 to 60 years and they came from different parts of the world, mainly Western Asia (19 participants). The other participants came from Europe (11), Africa (7), South and East Asia (5) and North America (1). Many migrants had difficulties describing their previous language knowledge: 3 state STS as their first learned language, 7 cannot give a clear answer and 9 mention gestures or homesign as their communication forms. Thirteen migrants have never attended school.

The teachers were interviewed about their educational and linguistic background, teaching experience, and knowledge and experiences of teaching deaf migrants (see Table 1). In total, 14 teachers were interviewed, of which five were men and nine were women. Of the teachers, 11 were deaf and three were hearing. All teachers are proficient in STS. The interviews generated approximately 13 h of video recordings.

Teachers’ education and teaching experience.

| Teacher | Upper secondary school teacher degree | Primary school teacher degree | Folk high school teacher certificate | Folk high school pedagogy (short course) | Sign language teacher certificate | Recreational leadership certificate | Other education | Years of teaching experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenneth | X | X | X | 10 | ||||

| Niklas | X | X | 26 | |||||

| Anita | X | X | 20 | |||||

| Ellinor | X | X | 17 | |||||

| Dennis | X | X | X | 11 | ||||

| Anna | X | 7 | ||||||

| Therese | 10 | |||||||

| Stefan | X | X | X | 20 | ||||

| Elisabeth | X | X | 26 | |||||

| Angela | X | X | 18 | |||||

| Fanny | X | X | X | 6 | ||||

| Oliver | X | X | 12 |

-

Alt text: The 14 teachers have different educational backgrounds, covering Upper secondary school teacher degrees, Primary school teacher degrees, Folk high school teacher certificates, Folk high school pedagogy (short course), Sign language teacher certificates, Recreational leadership certificates, and Other education. Their teaching experience range between 6 and 26 years.

The 43 migrants constitute a very heterogeneous group with very different linguistic and educational backgrounds. However, in this sub-study, the focus was on the migrants who have never attended school and are emergent readers. They are sometimes taught individually, and sometimes in a group with other emergent readers. At other times they participate in groups with participants with a higher level of print literacy knowledge. For this sub-study we have qualitatively analysed the classroom interaction, focusing on Swedish language lessons (approx. 15 h of recordings including all four schools) in which one or more emergent readers were included. In the analysis, we searched for common exercises and recurring patterns in the recorded instruction and after transcribed these into written English. Through this work, we identified five themes which will be presented in the results section below.

5 Results

In the analysis of Swedish language instruction, we found some exercises common and recurring. We also found similar difficulties, regardless of school and teacher. This section presents the results from the classroom interaction analysis by illustrating examples of recurring patterns in exercises in the classrooms. These recurring patterns are divided into five themes: 1) Writing techniques, 2) Vocabulary training through fingerspelling, 3) Vocabulary training using word lists, 4) Surface versus deep reading – transliteration and 5) Cognitive aspects of literacy learning.

5.1 Writing techniques

Emergent readers have to learn a whole new technique when they start learning how to write. In present-day Sweden, this means both handwriting and computer typing. However, here, we will zoom in on handwriting exercises because these seem to be the most complex. Computer typing technique seems to be easier to develop after having learned the alphabet and uppercase and lowercase letters. The migrants can look at written texts and replicate them by typing. Also, this basic knowledge of computer typing and the alphabet allowed them to search for Swedish words in Google pictures or in the STS dictionary. Interestingly, we found that several emergent readers experienced significant difficulty logging on to computers or platforms because they struggled with the process of using usernames and passwords.

Handwriting exercises occurred in several forms, as illustrated in pictures a–d in Figure 2. Emergent readers and migrants with other writing systems than the Latin system were taught to write letters by copying and repeating them in print (picture a), writing from left to right, up to down, and on the lines. They were also taught to write words and sentences by copying and repeating (picture b). The exercises differed between the participants, depending on how recently they had arrived, their previous writing skills, and how quickly they learned to write.

Different handwriting exercises (pictures a–d). Alt text: Different hand-writing exercises cover learning to write the Latin alphabet by copying capital and lowercase letters on rows, copying words and phrases, training to express phrases, and responding to written questions.

As illustrated in picture c, it is not obvious how emergent readers understand how to write sentences. Here, Rashid (emergent reader, arrived in Sweden 1.5 years ago) practices writing his name in sentences, copying a sentence on the board that the teacher has written. When looking at the lines, it is possible to see how the space between the letters becomes bigger and bigger, row by row. In the last rows, the first word in the sentence, jag ‘I’, is spelt as if it is two words instead of one.

Another interesting feature in the learn-to-write process is illustrated in picture d. As previously shown, most exercises are about copying and repeating pre-written letters, words or sentences. Here, however, the participant is going to learn to write answers to questions or add the last part of a sentence without having a pre-written text to copy. In the first sentence, where the first two pre-written words are Jag heter ‘My name is’, Lateefa (emergent reader, arrived in Sweden four years ago) manages to respond correctly with her name, but in the next sentence, Jag kommer från ‘I come from’, she just copies the same words instead of answering with the name of her country. A number of teachers have confirmed that some emergent readers often responded to questions with a copy of the question in itself and mentioned that it was difficult to get them to understand that it was a question they should respond to instead of just copying it.

5.2 Vocabulary training through fingerspelling

In the classrooms, fingerspelling exercises are a common part of vocabulary training. One example is when the teacher Anna, Lateefa and Mahad (emergent reader, arrived in Sweden two years ago) are working with three words, juice ‘juice’ haj ‘shark’ and olja ‘oil’, which have been written on the whiteboard. There was also a TV with pictures from Google. Anna starts by asking Lateefa and Mahad to fingerspell juice. Excerpt 1 below shows the interaction between Anna and the two participants.

Anna clearly tried to structure and scaffold Lateefa’s and Mahad’s fingerspelling of the words. However, despite the word being visible on the whiteboard and Anna fingerspelling the word, letter by letter, both participants, especially Lateefa, have difficulties finding the correct manual alphabet for each letter as in (3) while searching for the U. Anna tried to scaffold through drawing the u in the space as in writing the u. In (6), Lateefa confuses the letter i with the letter l, which is not surprising as i and l are similar in form. In (8), Lateefa first responds to the manual alphabet of S but changes to C. This is interesting as these manual alphabets share the same hand shape and the only difference between them is the hand orientation. The same applies to Mahad in (9) when he hesitated between the manual alphabets of O, G and E. In STS, they look similar in form, i.e. like a fist, but with variation in how the thumb is positioned.

Excerpt 1:

Joint fingerspelling of the word juice.

Alt text: Interaction between the teacher Anna and participants Mahad and Lateefa when train to connect letters in written Swedish to letters in Swedish Sign Language hand alphabet.

After completing this turn of joint fingerspelling, Anna asked them to do it again. Mahad managed to pair the letters with the manual alphabets, while Lateefa got stuck again at the second letter u in (12). Interestingly, Lateefa refers to N as it has the same handshape as U but with a different hand orientation. The excerpt illustrates the complexity of matching letters to manual alphabets. On the one hand, the visual orthography of Swedish letters is not easy to learn, and there are letters that have similar forms (e.g. i and l). On the other hand, the manual alphabets need to be acquired as well, and many manual alphabets have similar hand configurations (i.e. C and S, G and E). The fingerspelling session with the remaining words haj and olja clearly shows that the learners have difficulties decoding the letters and pairing them with the manual alphabet. For example, with the j in haj and olja, Mahad hesitates between I, J, and Y despite practicing correctly on j in the previous word, juice. However, in this context, each word starts with an uppercase letter, i.e. Juice, Haj and Olja. The difference between J and j, as well as the phonological similarity of J and Y (same handshape but different movements), adds complexity to the learning. The fact that the sign equivalent of juice is a lexicalized fingerspelling makes it even more difficult to link the word to the sign. Anna prototypically refers to it as an “orange drink” although there are different kinds of juice. This excerpt further illustrates the importance of careful planning of what words to train and how to practice them, as well as the awareness of the complexity of letters and manual alphabets.

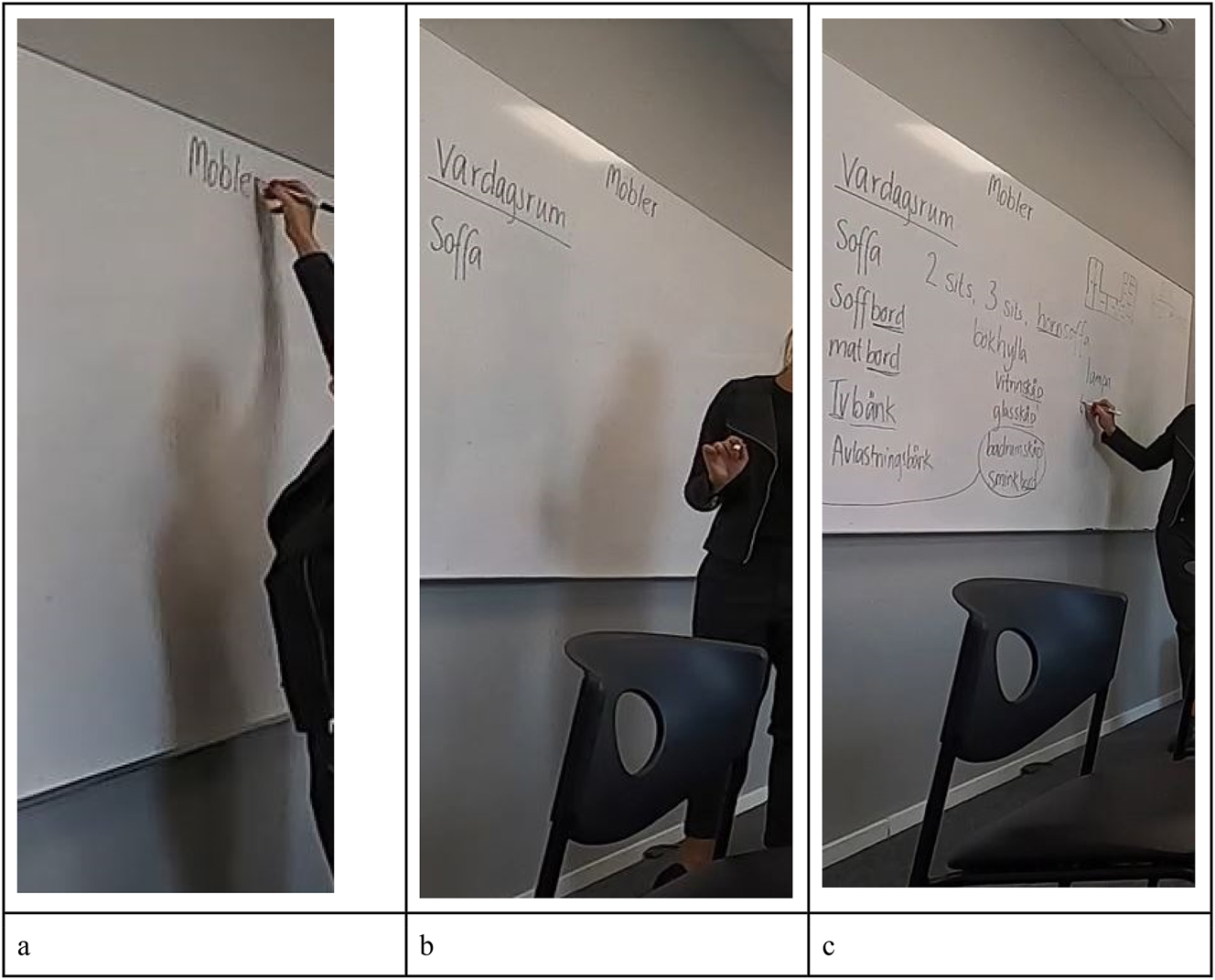

5.3 Vocabulary training using word lists

Another vocabulary exercise is to create lists of Swedish words together by negotiating topics or themes. The teacher usually initiates a theme and asks the participants for words fitting into this theme. The list is gradually expanded during the lesson, and the participants write down the Swedish words in their notebooks, which become filled with a range of words on different topics. STS is constantly used in the negotiation of words. One such recurring exercise is illustrated in Figure 3, in which the teacher Angela starts writing the Swedish word Möbler ‘Furniture’, as illustrated in picture a. She asked Ana (who has previous print literacy skills but recently arrived in Sweden) and Hussein (emergent reader, arrived in Sweden five years ago) for the equivalent STS sign. They both signs the STS sign FURNITURE and Angela agrees. She mentions that they are focusing on the living room by writing Vardagsrum ‘Living room’ on the board. Angela turns to Ana and Hussein, signing LIVING-ROOM, and they imitate the sign. Angela continues, asking which furniture they can find in this room. Hussein illustrates the shape of a sofa or an armchair, and Angela asks him to fingerspell the word, but he responds that he does not know. Angela turns to Ana, but she does not know either. Angela writes the word Soffa ‘Sofa’ on the board (picture b). She then adds different types of sofas for two or three persons, and corner sofas. After this, the negotiation continues and the list is expanded. During the negotiation, Ana and Hussein begin to suggest furniture that is usually found in other rooms, such as makeup tables and bathroom cabinets, and Angela adds them to the list but soon realises that the words do not belong to the topic of “living room” and draws a circle around them with a line and an arrow to connect them to the heading Sovrum ‘bedroom’ instead (picture c).

Vocabulary training (picture a–c). Alt text: The teacher writes words related to the living room on the whiteboard.

After a while, Fatima (emergent reader, arrived in Sweden five years ago) joins the class, and Angela asks Ana and Hussein to note the words on the board in their notebooks. She turns to Fatima, directing her attention to the board that is covered with the range of words that Ana and Hussein have suggested, meaning that Fatima’s learning takes a totally different path. Angela points to the first word Soffa ‘Sofa’, and Fatima fingerspells the word correctly. However, she does not know the meaning of the word, although she can fingerspell the word letter by letter. Angela therefore explains what a sofa is using different signs and examples. And the teaching continues this way. As Fatima was not involved in the previous negotiation process, she is exposed to many words, drawings and arrows simultaneously all over the place.

The example shows how difficult it is for emergent readers (Hussein and Fatima) to connect signs, fingerspelling and written words to meaning. Although Ana has recently arrived in Sweden, she is literate in both Persian and English and appears to develop her written Swedish skills rapidly, while Hussein and Fatima have developed very limited written Swedish skills, even though they have been in Sweden for five years.

The difficulties in using a broad vocabulary and several synonyms were also present in other exercises. For example, it is common to play memory games to pair words with pictures. Word cards can be placed on one side of the table and picture cards on the other. The participants turn the cards, trying to match words that are equivalent to pictures. Hussein turns over a picture card with a house and another card with the word hus ‘house’. However, Ana says that it is not the correct word for that picture. Hussein insists and checks the STS dictionary on his mobile phone. He found the sign for house and was satisfied with being correct. However, Ana is still not convinced. When Angela arrives, she confirms that hus is wrong, as it should be radhus ‘terraced house’. The words are similar, both referring to a type of house, and it seems that the large variety of pictures and words makes everything too complex for the emergent readers, who would benefit from a memory game that had a more limited word list (see also Duggan forthcoming).

5.4 Surface versus deep reading – transliteration

It is seldom that emergent readers independently read texts in the classroom. This is supposedly due to their limited written language skills. Instead, the exercises mainly focus on vocabulary training and connecting words with pictures, usually using Google. The usual exercises mean that emergent readers get documents with different Swedish words and pictures that they try to match using Google or the STS dictionary.

However, a recurring activity in Swedish instruction is joint reading activities in which migrants from different backgrounds are taught collectively. This kind of activity means that the class looks at a page from a book (e.g. via a screen in the classroom) and signs the text word by word together (i.e. transliterating[1]). The teacher sometimes writes the same text on the board to make it easier to point to separate words while the whole class can see them (see Figure 4).

The teacher writes the same sentences from a book on the board. Alt text: A digital screen with a text is visible in the classroom and the teacher write the same sentences on a blackboard.

This method means that the participants learn to connect words with sign equivalents, but it is unclear to what extent they understand the texts’ meaning. It depends on their varied linguistic repertoires. Sometimes, like in the exercise illustrated in Figure 4, the teachers ask the participants to translate the content into STS after having transliterated the text word by word into STS. In such cases, it is apparent that those participants with limited knowledge of Swedish and STS cannot translate as translation requires proficiency in both languages. The emergent readers in our study have not acquired sufficient vocabulary to be able to translate and, for them, the process of first transliterating a written text into STS and then translating it into “real” STS appears to be rather confusing.

For those participants who have some knowledge of print literacy, transliteration also occur when they independently read texts. But while participants with more robust knowledge of print literacy use dictionaries from their home country’s written language (or any written language they previously knew), those participants with more limited knowledge appear to only have STS dictionaries as tools. In Excerpt 2, Flora, who has some previous knowledge of print literacy, reads a text and signs it word by word, i.e. connects a written word to its sign equivalent but follows the grammatical structure of written Swedish.

Excerpt 2:

Transliteration from written Swedish into STS.

Alt text: Flora sign the Swedish text word for word and use the Swedish Sign Language dictionary to check words she do not know the sign for.

When Flora searches for the word helst ‘preferably’ in the dictionary, she gets a variety of available sign equivalents. The first sign is a fingerspelled version of the same word, which does not help her, so she chooses the next and finds a sign that matches the Swedish word. After a while, she arrives at the phrase gå hem och byta om ‘went home to change’. Here, Flora does not capture the difference between the Swedish phrase byta om and the STS phrase CHANGE CLOTHES. Instead, the transliteration leads to an unintelligible utterance because om as a single word means ‘if’ and ‘again’ (among others). However, in this context, om functions as a particle verb which, together with the verb byta, gives a specific meaning associated with “change clothes”. Although learners may have no problem mapping single words with signs, there comes a point when learners need to expand their vocabulary to recognise that some words are part of basic phrases such as byta om ‘change’, växa upp ‘grow up’. These can be hard for learners to learn and teachers to teach and, in such contexts, the transliteration process may result in a completely erroneous meaning. In their three-way model for print literacy learning, Hoffmeister and Caldwell-Harris (2014) point out that many deaf students struggle with this stage of print literacy learning, while sign-word mapping is often fairly unproblematic.

5.5 Cognitive aspects of literacy learning

A common pattern in teaching emergent readers is that they seem to forget written words almost immediately after they have learned them. In the interviews, several teachers highlighted this as a challenge and felt that they lacked the strategies to support the participants. For example, the teacher Angela states:

Many of the participants have such a hard time with [writing Swedish]. And if they didn’t learn to read and write in their home country, it’s even more difficult. […] They even have difficulties with the hand alphabet, that each letter is meaningful, they have such a hard time grasping that – they’re just like symbols for them … We have three participants like this now and they wouldn’t be able to read a note from their employer saying “Can you go to the warehouse and pick up xxx” … They wouldn’t have a clue. They imitate a lot – I think they try to learn written words through visual memory and repeatedly practicing to remember. Sometimes they see a word and then they say “I’ve forgotten how to sign it” – but they haven’t forgotten, they don’t know what the word means. I can sign CUCUMBER and then they say “yes exactly that” and mean that they forgot the sign. But that’s not the case, they don’t understand the word. [---] They keep forgetting. We can go through the same word list seven to eight times and they still don’t remember. It’s something in the brain – they haven’t practiced that. But in STS it gets stuck.

One example of this is illustrated in Excerpt 3. Here, the teacher, Fanny and Fatima negotiate the meaning of written words on the whiteboard. It is full of Swedish words for different kitchen items, e.g. spis ‘stove’, ugn ‘oven’, diskmaskin ‘dishwasher’, mikro ‘micro’. The Swedish word mikro is a contraction of mikrovågsugn ‘microwave oven’. The full Swedish word ends with “-ugn”, the same as in the single word ugn ‘oven’. Fatima has no problem fingerspelling the written words but has difficulties connecting the correct sign equivalent to the written words and remembering them.

Excerpt 3:

Difficulties remembering and connecting signs, fingerspelling and written words.

Alt text: The teacher Fanny and participant Fatima negotiate the meaning of, fingerspelling and sign for different words related to kitchen.

When Fanny points to the word spis ‘stove’ (1), Fatima wrongly suggests the sign for MICROWAVE-OVEN (2). Fanny lets her know that it is wrong, and Fatima then suggests the correct sign STOVE (4). Fanny then points to the next word, ugn ‘oven, and Fatima again suggests MICROWAVE-OVEN (8), but Fanny replies that it is wrong. Fatima fingerspells UGN@b again and tries the sign for MACHINE (10), which is also wrong. Fanny seems to not notice the sign MACHINE, but points to Fatima and says that the sign she has used means micro with the sign equivalent MICROWAVE-OVEN. Then Fanny points again to the word ugn ‘oven’ and Fatima suggests a third sign: DISH (14), also the wrong sign. Fanny tells her the correct sign, OVEN, and Fatima seems to slump, looking both surprised and frustrated (16). Her signing is then a little unclear, but she seems to say that she must practice more. After being briefly interrupted by another participant, Fanny again fingerspells and signs ‘oven’, and Fanny continues to the next word on the list, diskmaskin ‘dishwasher’. Fatima fingerspells correctly but immediately suggests the same sign, OVEN, for this next word (28). Thus, Fatima seems not to be able to make the connections between the written, fingerspelled and sign equivalents and seems to immediately forget the recently negotiated equivalents through using the same sign again. Here it is clear that Fatima’s working memory is very short and that the cognitive workload is too high for her to handle the exercise and manage to add new knowledge.

6 Discussion

This study is one of the first studies providing a closer look at interaction and learning in the classroom when teaching print literacy to deaf emergent readers. Previous research on adult second language learners and emergent readers has emphasised the interactive use of oral language to facilitate the development of print literacy. Thus, new learners of Swedish, for example, are expected to learn the oral language through both natural interaction (cf., Krashen 1985) and formal instruction. The instruction is usually based on the learners knowing some oral Swedish and many exercises aim to train them to express themselves and interact with others through this mode. The writing exercises are usually closely connected to oral language skills in the classroom and in educational materials, etc. For emergent readers, writing technique is also important, as well as learning how phonology is connected to orthography.

The situation for deaf emergent readers differs from that of hearing migrants as they cannot simply rely on their oral language skills. As a result, much of the existing literature based on hearing migrants is not relevant to this group. Additionally, many deaf emergent readers have had limited exposure to sign language and may not have received formal schooling in their home countries. However, it is worth noting that deaf individuals possess significant communication knowledge through the use of gestures, pointing, body language, and signs developed within their home environment (cf. Kusters et al. 2020). Despite their limited exposure to named or standardised language, they possess a broad communicative repertoire.

Upon arrival in a country like Sweden, with a strong monolingual and literary tradition, deaf emergent readers face significant challenges in communication, expressing their needs, and finding work that does not require literacy skills. This often leads to negative perceptions of them as language-deprived, problematic or “having no language” (Duggan and Holmström 2022; Moriarty Harrelson 2019). Simply put, they lack the necessary skills to navigate in a Western country.

However, to be able to participate in Swedish society, deaf emergent readers must develop literacy skills. This can be a slow and cognitively demanding process, particularly for those without a communicative background grounded in a spoken language with a written counterpart. Many emergent readers are also emergent signers of a named sign language, such as STS, and may require a different education model. Currently, deaf migrant education follows a one-size-fits-all approach. For emergent readers/signers, a significant focus on learning STS is essential. It is crucial to develop proficiency in this language first to cope with everyday life in Sweden, communicate needs, and use STS interpreters in different contexts. Once STS proficiency is achieved, print literacy training can begin.

For emergent readers to learn Swedish, the process is two-fold, as they learn print literacy in a new language. Thus, the teaching needs to focus on both vocabulary learning and reading and writing techniques. Emergent readers need to learn how to use pen and paper, as well as a computer, and they also need to learn the written equivalents of their sign vocabulary. As mentioned in the Bedrock Literacy Curriculum, it is not constructive to just create multiple word lists, to use multiple contexts, and mix different types of words and synonyms in a “higgledy-piggledy” manner. The instruction needs to be more pre-planned and structured, with a limited number of (high-frequent/“sight”) words that must be stored in the participants’ long-time memories through frequent repetition.

Our study found that teachers lack such strategies. There could be many reasons for this. For example, the folk high schools’ idea is that education should be based on the students’ needs, previous knowledge and experience. It means that the schools do not have a pre-determined or official curriculum but can develop the content and direction of their own courses independently (see Duggan et al. 2023). This could explain why teachers often created word lists on the board spontaneously together with the participants. They could ask for words connected to a place or a theme (and during the instruction, they extended this list to also include advanced and unusual words) and write them on the board with no limitations or structure. Another reason for the strategies used is that deaf teachers may have their own experience of sign bilingual education. In such settings, it is common to work together in the classrooms with words or text on the board using sign language as a medium, as found in our analysis (see, e.g. Holmström and Schönström 2020). However, in such classrooms in Sweden, the children usually have a robust STS as their first language and are therefore better “equipped” for this approach to work. It is possible that such an approach needs to be adjusted to the ability of the emergent readers, i.e. word lists need to be more selective, texts need to be shorter/simpler, and the work needs to be more structured (cf. Di Perri 2021).

In some exercises in which emergent readers were instructed together with participants who had a more robust previous language, as well as skills in the written language of their home countries, we found that the emergent readers became frustrated and disappointed when they were unable to develop at the same rate as the other participants and did not remember the written words they had just “learned”. In certain contexts, it may be positive to learn from more skilled peers (Vygotsky 1978), but in others, they may need more concentrated and structured instruction in a group of peers who are also emergent readers. In addition, we found that the teachers tended to ask questions to the migrants and then quickly give them the answers. This may be attributable to their frustration at the slow process or because they do not think the participants can answer themselves. It is possible that it would be beneficial if the teachers were more patient and gave the migrants more time to answer. By accepting that the process is very time-consuming, the teachers may be more accepting of the slow teaching rate.

7 Conclusions

In Sweden, (hearing) adult migrants are offered limited time to participate in different kinds of education to learn Swedish, be able to become a member of society and get a job. Various authorities cover the cost of education and expect results according to different time frames. Deaf migrants are offered the same amount of time, even though they have to learn both STS and written Swedish. This is not sustainable. As our study shows, deaf emergent readers struggle greatly when learning written Swedish. The instruction needs to be focused on STS at first, allowing them to interact both in the classroom and in leisure activities and to learn STS in formal instruction. Only after they have developed sufficient communication skills and vocabulary in STS, will they begin to learn written Swedish. If this is to happen, significantly more time is required than is currently offered by the Swedish authorities.

It is possible that the instruction needs to focus on the most necessary aspects of print literacy related to the everyday lives of deaf emergent readers. The participants in our study are adults, and several care for children. They need to “survive” in Swedish society and learn a vocabulary that is “good enough” to deal with the most common situations and activities they meet outside school, for example, buying food, writing their name and address, being able to understand bus and train timetables or understanding official instructions on signs and boards, etc. In other words, the teaching needs to be more pre-planned, selective and structured. It should focus more on a kind of “survival” Swedish. Also, with a fairly robust STS, the emergent readers could use STS interpreters, making their participation in society reasonably satisfying.

Funding source: Vetenskapsrådet

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2019-02115

Acknowledgments

This study is part of an ongoing larger research project funded by the Swedish Research Council (2019-02115). We are grateful to the council for the funding, making it possible to conduct the study. We also would like to thank Nora Duggan for her assistance in data collection and the teachers and participants for their willingness to participate in the study. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier manuscript drafts.

References

Beck, Isabel L., Margaret G. McKeown & Linda Kucan. 2013. Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction, 2nd edn. New York and London: Guilford Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Caldwell-Harris, Catherine L. 2021. Theoretical underpinnings of acquiring English via print. In Charlotte Enns, Jonathan Henner & Lynn McQuarrie (eds.), Discussing bilingualism in deaf children: Essays in honor of Robert Hoffmeister, 73–95. New York and London: Routledge.10.4324/9780367808686-6-7Search in Google Scholar

Chamberlain, Charlene & Rachel I. Mayberry. 2008. American Sign Language syntactic and narrative comprehension in skilled and less skilled readers: Bilingual and bimodal evidence for the linguistic basis of reading. Applied Psycholinguistics 29(3). 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1017/s014271640808017x.Search in Google Scholar

Coady, James & Thomas Huckin. 1997. Second language vocabulary acquisition: A rationale for pedagogy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139524643Search in Google Scholar

Dahlstedt, Magnus, Andreas Fejes & Sabine Gruber. 2019. Folkbildning på svenska? En studie av språkintroduktion för migranter i studieförbundet Sensus regi (Linköping studies in social work and welfare, No. 2019:1). Linköping: Linköping University.Search in Google Scholar

De Meulder, Maartje, Annelies Kusters, Erin Moriarty & Joe J. Murray. 2019. Describe, don’t prescribe. The practice and politics of translanguaging in the context of deaf signers. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40(10). 892–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1592181.Search in Google Scholar

Di Perri, Kristin A. 2021. The bedrock literacy curriculum. In Charlotte Enns, Jonathan Henner & Lynn McQuarrie (eds.), Discussing bilingualism in deaf children: Essays in honor of Robert Hoffmeister, 132–149. New York and London: Routledge.10.4324/9780367808686-9-11Search in Google Scholar

Dolch, Edward W. 1936. A basic sight vocabulary. Elementary School Journal 36(6). 456–460. https://doi.org/10.1086/457353.Search in Google Scholar

Duggan, Nora. forthcoming. “Why the long nose?”: Deaf migrants and linguistic capital in adult education.Search in Google Scholar

Duggan, Nora & Ingela Holmström. 2022. “They have no language”: Exploring language ideologies in adult education for deaf migrants. Apples - Journal of Applied Language Studies 16(2). 147–165. https://doi.org/10.47862/apples.111809.Search in Google Scholar

Duggan, Nora, Ingela Holmström & Krister Schönström. 2023. Translanguaging practice in adult education for deaf migrants. DELTA: Documentação de Estudos em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada 39(1). 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-460X202359764.Search in Google Scholar

Easterbrooks, Susan R. & Sandra G. Huston. 2008. The signed reading fluency of students who are deaf/hard of hearing. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 13(1). 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enm030.Search in Google Scholar

Falk, Jodi L., Kristin A. Di Perri, Amanda Howerton-Fox & Carly Jezik. 2020. Implications of a sight word intervention for Deaf students. American Annals of the Deaf 164(5). 592–607. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2020.0005.Search in Google Scholar

Fejes, Andreas. 2019. Adult education and the fostering of asylum seekers as “full” citizens. International Review of Education 65. 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-019-09769-2.Search in Google Scholar

Fejes, Andreas, Magnus Dahlstedt, Nedžad Mešić & Sofia Nyström. 2018a. Svenska(r) från dag ett: En studie av ABFs arbete med asylsökande. ABFs skriftserie Folkbildning och Forsknin. Stockholm: Arbetarnas bildningsförbund.Search in Google Scholar

Fejes, Andreas, Robert Aman, Magnus Dahlstedt, Sabine Gruber, Ronny Högberg & Sofia Nyström. 2018b. Introduktion på svenska: Om språkintroduktion för nyanlända på gymnasieskola och folkhögskola (Studier av vuxenutbildning och folkbildning, No. 8). Linköping: Linköping University.Search in Google Scholar

Fry, Edward. 1980. The new instant word list. The Reading Teacher 34(3). 284–289.Search in Google Scholar

Gulati, Sanjay. 2018. Language deprivation syndrome. In Neil S. Glickman & Wyatte C. Hall (eds.), Language deprivation and deaf mental health, 24–53. New York and London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315166728-2Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Wyatte C. 2017. What you don’t know can hurt you: The risk of language deprivation by impairing sign language development in deaf children. Maternal and Child Health Journal 21(5). 961–965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2287-y.Search in Google Scholar

Hoffmeister, Robert J. & Catherine L. Caldwell-Harris. 2014. Acquiring English as a second language via print: The task for deaf children. Cognition 132(2). 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.03.014.Search in Google Scholar

Holmström, Ingela & Krister Schönström. 2018. Deaf lecturers’ translanguaging in a higher education setting. A multimodal multilingual perspective. Applied Linguistics Review 9(1). 90–111. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0078.Search in Google Scholar

Holmström, Ingela & Krister Schönström. 2020. Sign languages. In Sara Laviosa & Maria González Davies (eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and education, 341–352. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780367854850-21Search in Google Scholar

Holmström, Ingela & Nina Sivunen. 2022. Diverse challenges for deaf migrants when navigating in Nordic countries. In Christopher Stone, Robert Adam, Ronice Müller de Quadros & Christian Rathmann (eds.), The Routledge handbook of sign language translation and interpretation, 409–424. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003019664-33Search in Google Scholar

Howerton-Fox, Amanda & Jodi L. Falk. 2019. Deaf children as ‘English learners’: The psycholinguistic turn in deaf education. Education Sciences 9(2). 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020133.Search in Google Scholar

Hrastinski, Iva & Ronnie B. Wilbur. 2016. Academic achievement of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in an ASL/English bilingual program. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21(2). 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/env072.Search in Google Scholar

Kolinsky, Régine, Cristina Carvalho, Isabel Leite, Ana Franco & José Morais. 2018. Completely illiterate adults can learn to decode in 3 months. Reading and Writing 31. 649–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9804-7.Search in Google Scholar

Kotik-Friedgut, Bella, Michal Schleifer, Pnina Golan-Cook & Keith Goldstein. 2014. A Lurian systemic-dynamic approach to teaching illiterate adults a new language with literacy. Psychology & Neuroscience 7(4). 493–501. https://doi.org/10.3922/j.psns.2014.4.08.Search in Google Scholar

Koulidobrova, Elena, Marlon Kuntze & Hannah Dostal. 2018. If you use ASL, should you study ESL? Limitations of a modality-b(i)ased policy. Language 94(2). e99–e126. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2018.0029.Search in Google Scholar

Krashen, Stephen D. 1985. The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London and New York: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Kuntze, Marlon, Debbie Golos & Charlotte Enns. 2014. Rethinking literacy: Broadening opportunities for visual learners. Sign Language Studies 14(2). 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1353/sls.2014.0002.Search in Google Scholar

Kusters, Annelies, Mara Green, Erin Moriarty & Kristin Snoddon. 2020. Sign language ideologies: Practices and politics. In Annelies Kusters, Mara Green, Erin Moriarty & Kristin Snoddon (eds.), Sign Language ideologies in practice, 3–22. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781501510090-001Search in Google Scholar

McQuarrie, Lynn & Raulo Parrila. 2014. Literacy and linguistic development in bilingual deaf children: Implications of the “and” for phonological processing. American Annals of the Deaf 159(4). 372–384. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2014.0034.Search in Google Scholar

Moriarty Harrelson, Erin. 2019. Deaf people with “no language”: Mobility and flexible accumulation in languaging practices of deaf people in Cambodia. Applied Linguistics Review 10(1). 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0081.Search in Google Scholar

Strong, Michael & Philip M. Prinz. 1997. A study of the relationship between American Sign Language and English literacy. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 2(1). 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.deafed.a014308.Search in Google Scholar

Svartholm, Kristina. 2008. The written Swedish of deaf children: A foundation for EFL. English in International Deaf Communication. Linguistic Insights 72. 211–250.Search in Google Scholar

Vinogradov, Patsy & Astrid Liden. 2008. Principled training for LESLLA instructors. In Ineke Van de Craats & Jeanne Kurvers (eds.), Low-educated adult second language and literacy acquisition: Proceedings of the fourth symposium, 133–144. Utrecht, The Netherlands: LOT.Search in Google Scholar

Vinogradov, Patsy & Martha Bigelow. 2010. Using oral language skills to build on the emerging literacy of adult English learners. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. http://www.cal.org/caelanetwork/resources/using-oral-language-skills.html (accessed 15 June 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Vygotsky, Lev S. 1978. Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. London: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wedin, Åsa, Jenny Rosén, Sori Rasti & Samira Hennius. 2016. Grundläggande litteracitet. Att undervisa vuxna med svenska som andraspråk. Stockholm: Skolverket.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- “Am I really abroad?” The informal language contact and social networks of Chinese foundation students in the UK

- Comprehension of English articles by Korean learners of L2 English and L3 Spanish

- Motivation and growth in kanji proficiency: a longitudinal study using latent growth curve modeling

- The impact of textual enhancement on the acquisition of third person possessive pronouns by child EFL learners

- Domain-general grit and domain-specific grit: conceptual structures, measurement, and associations with the achievement of German as a foreign language

- The different effects of the ideal L2 self and intrinsic motivation on reading performance via engagement among young Chinese second-language learners

- Image-schema-based-instruction enhanced L2 construction learning with the optimal balance between attention to form and meaning

- Investigating willingness to communicate in synchronous group discussion tasks: one step closer towards authentic communication

- Investigating willingness to communicate vis-à-vis learner talk in a low-proficiency EAP classroom in the UK study-abroad context

- Functions, sociocultural explanations and conversational influence of discourse markers: focus on zenme shuo ne in L2 Chinese

- The impact of abdominal enhancement techniques on L1 Spanish, Japanese and Mandarin speakers’ English pronunciation

- Discourse competence across band scores: an analysis of speaking performance in the General English Proficiency Test

- Videoed storytelling in primary education EFL: exploring trainees’ digital shift

- Competing factors in SLA: how the CASP model of SLA explains the acquisition of English restrictive relative clauses by native speakers of Arabic and Korean

- Factors behind L2 English learners’ performance of oppositional speech acts: a look at pragmatic-related episodes (PREs) during thinking aloud

- Revisiting after-class boredom via exploratory structural equation modeling

- Exploring aural vocabulary knowledge for TOEIC as a language exit requirement in higher education in Taiwan

- Grammatical gender assignment in L3 versus L4 Swedish: a pseudo-longitudinal study

- Strategic reading comprehension in L2 and L3: assuming relative interdependence within Cummins’ linguistic interdependence hypothesis

- Incidental collocational learning from reading-while-listening and the impact of synchronized textual enhancement

- Learnability of L2 collocations and L1 influence on L2 collocational representations of Japanese learners of English

- The use of interlanguage pragmatic learning strategies (IPLS) by L2 learners: the impact of age, gender, language learning experience, and L2 proficiency levels

- “They forget and forget all the time.” The complexity of teaching adult deaf emergent readers print literacy

- Exploring the learning benefits of collaborative writing in L2 Chinese: a product-oriented perspective

- Investigating the effects of varying Accelerative Integrated Method instruction on spoken recall accuracy: a case study with junior primary learners of French

- Testing a model of EFL teachers’ work engagement: the roles of teachers’ professional identity, L2 grit, and foreign language teaching enjoyment

- The combined effects of a higher-level verb distribution and verb semantics on second language learners’ restriction of L2 construction generalization

- Insights from an empirical study on communicative functions and L1 use during conceptual mediation in L2 peer interaction

- On the acquisition of tense and agreement in L2 English by adult speakers of L1 Chinese

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- “Am I really abroad?” The informal language contact and social networks of Chinese foundation students in the UK

- Comprehension of English articles by Korean learners of L2 English and L3 Spanish

- Motivation and growth in kanji proficiency: a longitudinal study using latent growth curve modeling

- The impact of textual enhancement on the acquisition of third person possessive pronouns by child EFL learners

- Domain-general grit and domain-specific grit: conceptual structures, measurement, and associations with the achievement of German as a foreign language

- The different effects of the ideal L2 self and intrinsic motivation on reading performance via engagement among young Chinese second-language learners

- Image-schema-based-instruction enhanced L2 construction learning with the optimal balance between attention to form and meaning

- Investigating willingness to communicate in synchronous group discussion tasks: one step closer towards authentic communication

- Investigating willingness to communicate vis-à-vis learner talk in a low-proficiency EAP classroom in the UK study-abroad context

- Functions, sociocultural explanations and conversational influence of discourse markers: focus on zenme shuo ne in L2 Chinese

- The impact of abdominal enhancement techniques on L1 Spanish, Japanese and Mandarin speakers’ English pronunciation

- Discourse competence across band scores: an analysis of speaking performance in the General English Proficiency Test

- Videoed storytelling in primary education EFL: exploring trainees’ digital shift

- Competing factors in SLA: how the CASP model of SLA explains the acquisition of English restrictive relative clauses by native speakers of Arabic and Korean

- Factors behind L2 English learners’ performance of oppositional speech acts: a look at pragmatic-related episodes (PREs) during thinking aloud

- Revisiting after-class boredom via exploratory structural equation modeling

- Exploring aural vocabulary knowledge for TOEIC as a language exit requirement in higher education in Taiwan

- Grammatical gender assignment in L3 versus L4 Swedish: a pseudo-longitudinal study

- Strategic reading comprehension in L2 and L3: assuming relative interdependence within Cummins’ linguistic interdependence hypothesis

- Incidental collocational learning from reading-while-listening and the impact of synchronized textual enhancement

- Learnability of L2 collocations and L1 influence on L2 collocational representations of Japanese learners of English

- The use of interlanguage pragmatic learning strategies (IPLS) by L2 learners: the impact of age, gender, language learning experience, and L2 proficiency levels

- “They forget and forget all the time.” The complexity of teaching adult deaf emergent readers print literacy

- Exploring the learning benefits of collaborative writing in L2 Chinese: a product-oriented perspective

- Investigating the effects of varying Accelerative Integrated Method instruction on spoken recall accuracy: a case study with junior primary learners of French

- Testing a model of EFL teachers’ work engagement: the roles of teachers’ professional identity, L2 grit, and foreign language teaching enjoyment

- The combined effects of a higher-level verb distribution and verb semantics on second language learners’ restriction of L2 construction generalization

- Insights from an empirical study on communicative functions and L1 use during conceptual mediation in L2 peer interaction

- On the acquisition of tense and agreement in L2 English by adult speakers of L1 Chinese