Abstract

Vocabulary learning is often assigned as out-of-class learning, which learners need to autonomously initiate and be motivated to sustain. Under such learning modes, though independent learners may need less motivational scaffolding, learners who prefer a more interactive study environment may need to be provided with assistance to boost their motivation. Focusing on such personal determinants, this study examines the role of self-construal in vocabulary learning by employing self-determination theory. The participants were 155 engineering students from a Japanese technical college. Path and mediation analyses were performed based on vocabulary test scores and questionnaire responses. Results revealed that independent self-construal had a significant impact on more self-determined types of both motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation and identified regulation) and amotivation, but interdependent self-construal was statistically irrelevant to them, in the context of vocabulary learning. Furthermore, perceived autonomy and competence mediated the relationship between independent self-construal and motivation. These findings indicate that vocabulary learning motivation is shaped and regulated by self-construal and may be enhanced through support of the mediators.

1 Introduction

Although acquisition of vocabulary is important for second language (L2) development (Nation 2001), learning vocabulary requires memorization that some learners consider a burdensome and laborious process. Indeed, the memorization-based nature of vocabulary acquisition is among the major demotivating facets of learning English as a foreign language (EFL) for secondary school students in Japan (Kikuchi 2009). Crucially, motivation plays a vital role in L2 acquisition (Dörnyei and Ryan 2015). As vocabulary development is an important part of L2 learning, investigating the motivation to learn vocabulary in addition to more general L2 learning motivation can lead to a more comprehensive understanding of L2 development. The first phase of the current project on vocabulary learning motivation (Tanaka 2017a) investigated how motivation and its antecedents influence vocabulary learning in a demotivating learning environment using a self-determination theory (SDT) framework (Ryan and Deci 2017). It demonstrated the importance of finding enjoyment and value in vocabulary learning, as well as the roles of autonomy, competence, and peers in either facilitating or dampening learners’ motivation. However, personal attributes are also assumed to influence motivation and L2 learning. In general, L2 learners often study vocabulary alone via self-study. Given the necessity of autonomy in vocabulary learning, independent learners may be at an advantage and need less motivational scaffolding, while learners who prefer a more interactive study environment may need to be provided with some assistance to boost their motivation to learn vocabulary. The concepts of independent and interdependent self-construal (Markus and Kitayama 1991) may be useful in investigating the effects of such individual dispositions. While those with high independent self-construal tend to be independent and autonomous, individuals with high interdependent self-construal are prone to socially oriented thought and behavior. Given the nature of vocabulary learning, which often entails self-study without social interaction, independent and interdependent self-construal are assumed to influence vocabulary learning and its motivation. This study examines the role of self-construal in EFL vocabulary learning using the SDT framework (Ryan and Deci 2017).

2 Literature review

2.1 Vocabulary learning and motivation

Although learning vocabulary is an essential factor in L2 acquisition, the sheer volume of English words poses challenges. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary contains “around 114,000 word families excluding proper names” (Nation 2001, p. 6), and educated speakers of English as a first language know “around 20,000 word families” (Nation 2001, p. 9). Although these numbers are not a realistic or necessary target for EFL learners, learners are usually required to master a large amount of vocabulary to be proficient in the language. As time to study vocabulary in class is frequently limited, vocabulary learning is often assigned as out-of-class learning, which learners need to autonomously initiate and be motivated to sustain.

As is well known, motivation is highly important in L2 learning (Dörnyei and Ryan 2015). Salient roles of motivation are also evident in L2 vocabulary learning. For instance, motivation has been associated with self-regulation (Tseng and Schmitt 2008), strategy use (Mizumoto and Takeuchi 2009), vocabulary size (Tanaka 2013, 2017a), and productive vocabulary development (Zheng 2012). As the challenge of learning vocabulary is among the central demotivators for secondary school students learning English in Japan (Kikuchi 2009), clarifying the factors that facilitate and undermine vocabulary learning motivation can lead to a better understanding of L2 learning in general and of L2 vocabulary acquisition in particular.

As is well known, motivation is highly important in L2 learning (Dörnyei and Ryan 2015). Salient roles of motivation are also evident in L2 vocabulary learning. For instance, motivation has been associated with self-regulation (Tseng and Schmitt 2008), strategy use (Mizumoto and Takeuchi 2009), vocabulary size (Tanaka 2013, 2017a), and productive vocabulary development (Zheng 2012). As the challenge of learning vocabulary is among the central demotivators for secondary school students learning English in Japan (Kikuchi 2009), clarifying the factors that facilitate and undermine vocabulary learning motivation can lead to a better understanding of L2 learning in general and of L2 vocabulary acquisition in particular.

2.2 Self-determination theory

SDT (Ryan and Deci 2017) is among the most widely used theories in motivational psychology (Dörnyei and Ryan 2015). The concept of learner autonomy underpins everything that entails self-study, especially vocabulary learning. Similarly, SDT—which includes the concept of autonomy—is particularly useful when investigating vocabulary learning motivation. SDT provides a framework to understand motivation in terms of the extent to which individual behavior regulation is self-determined. It broadly categorizes motivation into three types: intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation (Ryan and Deci 2017).

With intrinsic motivation, an individual is engaged in activities for their own sake and pleasure. This type of motivation is considered the most self-determined type of motivation, as it is not influenced by external pressure but is congruent with the person’s core self. Amotivation refers to a state in which an individual lacks the motivation to act. It occurs when individuals do not perceive a contingency between their actions and the outcomes of those actions, but believe that external factors beyond their control cause the consequences. In general, individuals in a state of amotivation avoid taking action or behave passively, and terminate their activities as soon as doing so becomes feasible.

Extrinsic motivation is a state regulated by external factors including the desire to earn a reward, avoid punishment, and/or maintain self-worth, and is further classified into four subtypes—external, introjected, identified, and integrated regulation—according to which values are internalized into one’s self-concept. External regulation is the least self-determined type of extrinsic motivation and is typically labeled “extrinsic motivation” in the literature. When externally regulated, an individual’s behavior is controlled by factors outside the self, such as various forms of reward and punishment. As individuals tend to terminate the behavior once the external contingency is removed, the effects of external regulation on behavior are transient. Introjected regulation is a slightly more self-determined type of extrinsic motivation and concerns the maintenance or enhancement of self-worth. In introjected regulation, individuals perform an activity out of a sense of duty, responsibility, or obligation to avoid feelings of guilt and/or shame. While the source of motivation (i.e., feelings of “should” and “ought”) resides within the person, these feelings are not derived from the core self but are instead controlling it. Thus, introjected regulation is not self-determined, although it is more self-determined than external regulation. Identified regulation concerns personal importance and values attached to an activity in relation to a person’s goals and outcomes, and is a more assertively self-determined type of extrinsic motivation. As the values placed on a behavior are relatively consistent with the sense of self, the individual’s behavior is considerably autonomous or self-determined. However, certain values can be separated from one’s other values, and might not necessarily reflect an individual’s overarching values in a given situation. Integrated regulation is the most self-determined type of extrinsic motivation and is similar to identified regulation in terms of personal importance and one’s values regarding an activity. While identified regulation may occur when the value an individual endorses is compartmentalized from his or her sense of self, integrated regulation occurs only when the values are fully assimilated to the self. In this state, the individual’s behavior is completely autonomous or self-determined. However, measurement difficulty has meant that integrated regulation has not been utilized or tested empirically in L2 settings (Noels 2001). Ryan and Deci (2017) argued that these types of motivation/regulation could be positioned along a continuum ranging from intrinsic motivation (the most self-determined form) to amotivation (lack of self-determination) according to the degree of self-determination.

As self-determination is the core concept of the theory, more self-determined types of motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation and identified regulation) are important to promote development (Ryan and Deci 2017). L2 learning researchers have also demonstrated the positive effects of intrinsic motivation and/or identified regulation on various aspects of L2 learning, such as vocabulary size (Tanaka 2013), L2 strategy use (Vandergrift 2005), persistence and self-evaluation (McEown et al. 2014; Noels et al. 1999), anxiety (Noels et al. 1999, 2000), and willingness to communicate (Joe et al. 2017). The first phase of the current project also revealed that intrinsic motivation and identified regulation were positive predictors of EFL vocabulary size (Tanaka 2017a).

Given the importance of more self-determined types of motivation, SDT stipulates that fulfilling the three basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) can promote intrinsic motivation and the internalization of extrinsic values (Ryan and Deci 2017). The current study focuses on the needs for autonomy and competence, which are operationalized as perceived autonomy and competence. Overall, both perceived autonomy and competence play an important role in promoting more self-determined types of motivation in L2 learning (Carreira et al. 2013; Noels et al. 2020). However, the effects do not necessarily appear uniformly in all the conditions (McEown and Oga-Baldwin 2019). For instance, autonomous motivation (intrinsic motivation and identified regulation) did not have a significant positive association with perceived competence (Tanaka 2017b) and perceived autonomy (Agawa and Takeuchi 2016). The first phase of this project (Tanaka 2017a) also demonstrated a lack of association between identified regulation and perceived competence, although perceived autonomy significantly predicted both intrinsic motivation and identified regulation. Despite the non-uniformity of the effects, the importance of these motivational antecedents are universally acknowledged in L2 learning (McEown and Oga-Baldwin, 2019; Noels et al. 2020).

2.3 Self-construal and motivation

Self-construal refers to how individuals define the self in relation to others. The concept was originally employed to investigate cultural differences in behaviors (Cross et al. 2011). As briefly mentioned earlier, self-construal is classified as independent or interdependent (Markus and Kitayama 1991). Independent self-construal is characterized by individualistic views of self. Individuals with high independent self-construal see themselves as distinct and separate from others and attach primary values to independence, autonomy, and individual uniqueness. Conversely, interdependent self-construal refers to views of the self that are inextricably bound to others. Individuals with high interdependent self-construal are oriented toward maintaining harmonious interpersonal connectedness with relevant others and are emotionally interdependent. These constructs have a salient influence on cognition, emotion, and motivation (Cross et al. 2011; Markus and Kitayama 1991). To illustrate, when asked to recall their earliest memory, Caucasians with independent self-construal tended to describe individual-focused memories, whereas Asians with interdependent self-construal tended to describe memories of social interactions (Wang and Ross 2005). Self-construal may affect memory.

Although cultural context shapes and promotes the adoption of a specific type of self-construal (Markus and Kitayama 1991), these modes are not mutually exclusive. Each individual demonstrates both forms of self-construal to some extent regardless of culture (Singelis 1994). With the accumulated evidence of the underlying role of self-construal in information processing, motivation, affect regulation, and social behavior, researchers have come to use the concept to investigate within-culture processes (Cross et al. 2011). For example, self-construal has been used to explain gender differences, as men and women in the United States are theorized to construct and maintain high levels of independent and interdependent self-construal, respectively (Cross and Madson 1997). Self-construal has also been used to investigate differences in motivation. For example, Wiekens and Stapel (2008) showed that when independent self-construal was primed, individuals were more motivated to be independent, autonomous, and alone. On the other hand, when interdependent self-construal was primed, individuals were more motivated to seek acceptance, conformity, and togetherness, and less motivated to be alone and independent. Thus, self-construal may influence an individual’s motivational orientation.

Based on a literature review, it seems that the work of Henry and Cliffordson (2013) is the only extant empirical study to examine the role of self-construal in L2 and third language (L3) learning motivation. Focusing on females’ social orientation, they investigated how gender influences L2 and L3 motivation via self-construal in a population of secondary school students in Sweden. Their structural equation modeling demonstrated that female students had higher interdependent self-construal than their male counterparts, which led to a higher ideal L3 self. As the ideal L3 self entails a vision for future social interaction in L3, the prominence of interdependent self-construal was evidenced in the socially oriented foreign language learning context. Other studies (Serafini 2020; Yashima et al. 2017) have also discussed the concept of self-construal in L2 learning. Serafini (2020) argued the importance of considering an interaction between learner selves and contextual factors, and called for replication studies of Henry and Cliffordson (2013) to be conducted with different types of learners in multiple contexts. Yashima et al. (2017) demonstrated that females tend to have a stronger communication orientation, which leads to a higher ideal L2 self. Although their study did not employ self-construal variables, they argued that the finding might be attributed to women’s high interdependent self-construal with interpersonal orientation. Considered together, previous studies suggested the significant role of self-construal in understanding the motivation to learn a foreign language; specifically, the salience of interdependent self-construal in a social interaction context.

The present study employs an SDT framework to investigate how self-construal is associated with L2 learning motivation. As discussed in the previous section, motivation is classified into five subtypes according to the extent of self-determination in a given behavior (Ryan and Deci 2017). With more self-determined types of motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation and identified regulation), individuals’ motivation is completely or considerably derived from the core self, and is less susceptible to external factors (Ryan and Deci 2017). As individuals with high independent self-construal value independence and separation from others (Markus and Kitayama 1991), their motivation is hypothesized as being independent and less susceptible to externally imposed values. In contrast, those with low independent self-construal might lapse into amotivation more easily because of a lack of self-determination. Conversely, when characterized by less self-determined types of motivation (i.e., introjected and external regulation), individuals do not internalize a behavioral value into their core self but are regulated by external factors (Ryan and Deci 2017). As individuals with high interdependent self-construal are concerned with maintaining social relationships and typically incorporate the perspectives of others in decision making (Cross et al. 2011), their motivation is susceptible to externally imposed values from those in their social circles. Thus, while independent self-construal may influence more self-determined types of motivation and amotivation, interdependent self-construal may be associated with less self-determined types of motivation. Research in other academic fields has also demonstrated the link between independent self-construal and more self-determined types of motivation. For example, Lee and Pounders (2019) showed positive links between independent self-construal, autonomous motivation (intrinsic and identified subscales of SDT), and intrinsic goal-framing. However, a significant association between interdependent self-construal and the SDT factors has not been found in a social marketing context. Kong and Ho (2016) also revealed the positive impact of independent self-construal on intrinsic workplace motivation.

Although prior research demonstrated the advantage of possessing interdependent self-construal in cultivating higher motivation to learn a foreign language in a socially oriented context (Henry and Cliffordson 2013), researchers in other fields have revealed the association between independent self-construal and more self-determined types of SDT motivation. Vocabulary learning is typically assigned as an out-of-class self-study, which requires autonomy on students’ part. Thus, independent self-construal, rather than interdependent self-construal, is assumed to be associated with more self-determined types of SDT motivation and plays a more influential role in this context.

2.4 First phase of the project on vocabulary learning motivation

The first phase of the project (Tanaka 2017a) investigated associations between EFL vocabulary learning motivation, antecedents of the motivation, and vocabulary size with science and engineering students in a somewhat demotivating learning environment. The study demonstrated significant positive associations between more self-determined types of motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation and identified regulation) and vocabulary size, revealing the importance of enjoyment and the values learners cultivate in vocabulary learning. Furthermore, the effects of antecedents on EFL vocabulary learning motivation were demonstrated primarily in the following three aspects: (a) perceived autonomy was important in enhancing intrinsic motivation and identified regulation; (b) while higher perceived competence promoted enjoyment in vocabulary learning (i.e., intrinsic motivation), lower perceived competence led to amotivation; and (c) negative peer influences (i.e., demotivation derived from perceiving peers’ disengagement with vocabulary learning) decreased intrinsic motivation and identified regulation but increased learners’ amotivation.

2.5 This study: The role of self-construal in vocabulary learning

Whereas the first phase of the study focused on the impact of SDT motivation on EFL vocabulary size and the key antecedents affecting that motivation, the focus of this study is to examine how self-construal influences vocabulary learning and its associated motivation. As self-construal may affect memory (Wang and Ross 2005), there may be a link between self-construal and vocabulary size (i.e., the learning outcome of vocabulary acquisition). As both independent self-construal and more self-determined types of SDT motivation entail a high degree of self-determination, the former may influence the latter in the context of vocabulary learning, which often requires students’ autonomy. As perceived autonomy, competence, and negative peer influences (i.e., demotivation derived from perceiving peers’ disengagement with vocabulary learning) are antecedents of more self-determined types of motivation (Tanaka 2017a), self-construal potentially influences the antecedents that in turn, might lead to motivation. To address these issues, this study investigates the following research questions:

RQ1. To what extent does self-construal predict vocabulary size?

RQ2. To what extent does self-construal predict the SDT subtypes of vocabulary learning motivation?

RQ3. To what extent does self-construal predict perceived autonomy, perceived competence, and negative peer influences?

RQ4. To what extent do perceived autonomy, perceived competence, and negative peer influences mediate the relationship between self-construal and motivation?

3 Method

3.1 Participants

Study participants (N = 155; 130 males and 25 females) were first-year science and engineering students at a public technical college in Japan who participated in Tanaka’s (2017a) main study. As the college accepts junior high school graduates who pass its entrance examination, the first year at the college is equivalent to the first year at secondary school in Japan. In general, science and engineering students tend to dislike rote memorization of vocabulary and grammatical patterns (a major pedagogical approach of secondary schools in Japan) and to be demotivated to study English (Apple et al. 2013). As vocabulary learning is one of the major demotivating facets of English learning (Kikuchi 2009), investigating the motivation of relatively demotivated engineering students has the potential to clarify the mechanism of vocabulary learning motivation more vividly.

The participants took five mandatory 45-minute English classes per week. Three classes focused on English reading with the grammar–translation method while the remaining two classes pursued grammar mastery. The students studied vocabulary with a vocabulary-learning book at home and were tested with weekly vocabulary quizzes. Their participation in this study was voluntary.

3.2 Instruments and procedures

Two types of instruments were employed in this study: an English vocabulary test and questionnaires. The participants took the English vocabulary test in class around the culmination of the 2012 academic year. The test items (k = 75) were taken from the first three word-frequency levels (1000–3000 levels) of Form 1 of the PC version of the Mochizuki Vocabulary Size Test (Aizawa and Mochizuki 2010). The participants were asked to choose the English equivalent of each Japanese word as follows:

| (1) dam | (2) sun | (3) war | |

| 太陽 |

-

The correct answer is 2.

The raw test scores were transformed into interval logit scores with Winsteps 3.80.0 (Linacre 2013). As the Rasch reliability estimates were adequately high for person (0.74) and item (0.93), the test was reliable for the participants (Tanaka 2017a).

Two types of questionnaires (i.e., on self-construal and vocabulary learning motivation) were distributed in the class at around the end of the academic year. Concerning the measurement of self-construal, the Self-Construal Scale (SCS; Singelis 1994) is the most commonly employed scale (Cross et al. 2011), but includes some items conforming to the North American culture (e.g., use of the first name; Takata 2000). On the other hand, Takata’s (2000) scale was developed based on Markus and Kitayama (1991) and the literature they drew on to describe interdependency in the Japanese cultural context (Takata 1993). This study employed Takata’s (2000) questionnaire to measure participants’ self-construal as it is contextualized and more appropriate in the Japanese social context (Takata 2003). For more information on the relationship between SCS and Takata’s (2000) scale, see Kashima and Hardie (2000).

As the Appendix shows, the scale consists of four constructs (k = 20). Two constructs were used to measure independent self-construal: dogmatism (k = 6) and individuality (k = 4). Dogmatism refers to the tendency to act based on one’s own decision regardless of others’ opinions. Individuality represents the propensity to recognize oneself as an individual separate from others. The constructs capture autonomy, agency, and independence: the primary aspects of independent self-construal. The remaining two constructs were employed to measure interdependent self-construal: dependency on others (k = 6) and evaluation apprehension (k = 4). Dependency on others represents the tendency to value relatedness and harmony with others. Evaluation apprehension refers to the tendency to be concerned with evaluation from others. Whereas dependency on others represents the typical interdependent self-construal as defined in the literature, evaluation apprehension is peculiar to the scale developed by Takata (2000). As those with high interdependent self-construal strive to maintain a harmonious relationship with relevant others, they tend to be more sensitive to others’ emotions and reactions (Cross and Madson 1997), and are concerned about others’ perspectives about their self. Evaluation apprehension reflects such characteristics of interdependent individuals who define themselves based on other’s view of the self.

Tanaka’s (2017a) questionnaires were used to measure the constructs related to vocabulary learning motivation. This study used 25 items for the five subtypes of SDT vocabulary learning motivation (intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, external regulation, and amotivation), and 15 items to measure the three antecedents of vocabulary learning motivation (perceived autonomy, competence, and negative peer influences). The participants responded to the questionnaire items in Japanese on a scale from 1 = Strongly disagree to 6 = Strongly agree. The reliability of each construct was analyzed with Winsteps 3.80.0 (Linacre 2013). The Rasch person reliability estimate, which is analogous to Cronbach’s α, was as follows: intrinsic motivation (0.81); identified regulation (0.77); introjected regulation (0.88); external regulation (0.77); amotivation (0.80); dogmatism (0.68); individuality (0.75); dependency on others (0.69); and evaluation apprehension (0.81).

4 Results

4.1 Preliminary analysis

4.1.1 Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among variables

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among variables used in this study. To answer the fourth research question, two composite scores were calculated by averaging the logit scores of individuality and dogmatism, and dependency on others and evaluation apprehension, for independent and interdependent self-construal, respectively.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among variables used in the study.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | |||||||||||||||

| 1. Test | − | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.25 | 0.24 | 0.30 | −0.23 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| Motivation | |||||||||||||||

| 2. IM | − | 0.53 | 0.14 | 0.04 | −0.35 | 0.43 | 0.43 | −0.11 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| 3. ID | − | 0.04 | 0.17 | −0.54 | 0.36 | 0.35 | −0.19 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | ||

| 4. IJ | − | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.26 | |||

| 5. EX | − | −0.20 | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.27 | ||||

| 6. AM | − | −0.19 | −0.23 | 0.30 | −0.21 | −0.19 | −0.17 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.08 | |||||

| Antecedents | |||||||||||||||

| 7. AUT | − | 0.75 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.16 | −0.13 | −0.06 | −0.15 | ||||||

| 8. COM | − | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.16 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.05 | |||||||

| 9. NEG | − | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| Self-Construal | |||||||||||||||

| 10. IndSC | − | 0.94 | 0.81 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.07 | |||||||||

| 11. IVT | − | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| 12. DOG | − | −0.23 | −0.15 | −0.23 | |||||||||||

| 13. InterSC | − | 0.78 | 0.96 | ||||||||||||

| 14. DEP | − | 0.56 | |||||||||||||

| 15. EVA | − | ||||||||||||||

| M | 0.23 | −1.22 | −0.16 | −1.68 | 0.15 | −0.70 | 0.16 | −0.56 | 0.94 | 0.36 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.10 |

| SE | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| 95% CI [LB] | 2.17 | −1.57 | −0.48 | −2.16 | −0.19 | −1.08 | −0.09 | −0.80 | 0.61 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.24 | −0.10 | −0.02 | −0.22 |

| 95% CI [UB] | 2.44 | −0.88 | 0.15 | −1.20 | 0.48 | −0.32 | 0.41 | −0.31 | 1.26 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.42 |

| SD | 0.86 | 2.18 | 1.98 | 3.04 | 2.10 | 2.39 | 1.60 | 1.54 | 2.04 | 1.46 | 2.04 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 0.94 | 2.01 |

-

N = 155. IM = Intrinsic motivation; ID = Identified regulation; IJ = Introjected regulation; EX = External regulation; AM = Amotivation; AUT = Perceived autonomy; COM = Perceived competence; NEG = Negative peer influences; IndSC = Independent self-construal; IVT = Individuality; DOG = Dogmatism; InterSC = Interdependent self-construal; DEP = Dependency on others; EVA = Evaluation apprehension. The value of independent self-construal is the composite score of individuality and dogmatism. The value of interdependent self-construal is the composite score of dependency on others and evaluation apprehension. The remaining values are based on Rasch logits of person ability. The descriptive statistics of motivation and its antecedents are taken from Tanaka (2017a).

4.1.2 Path models

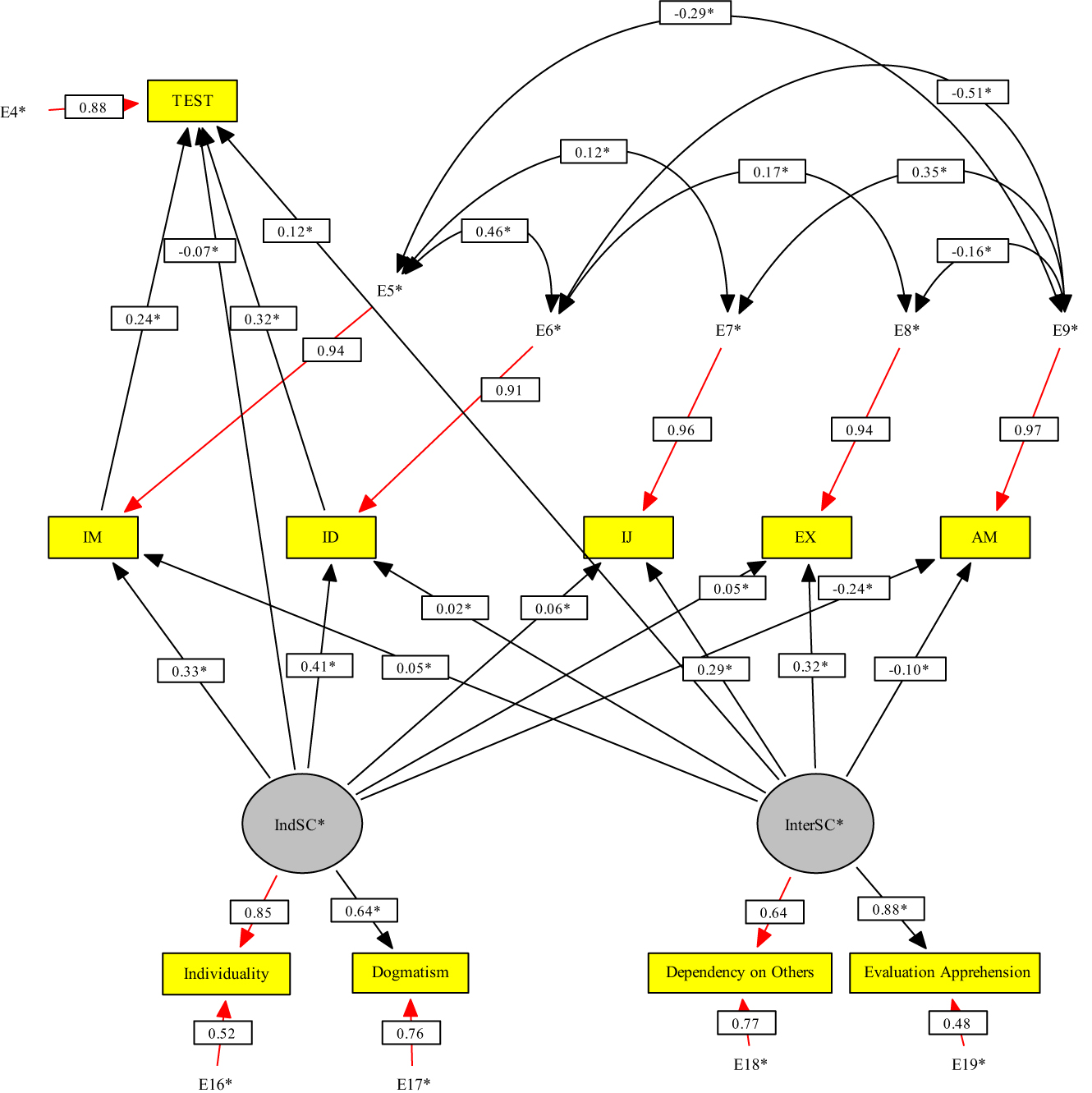

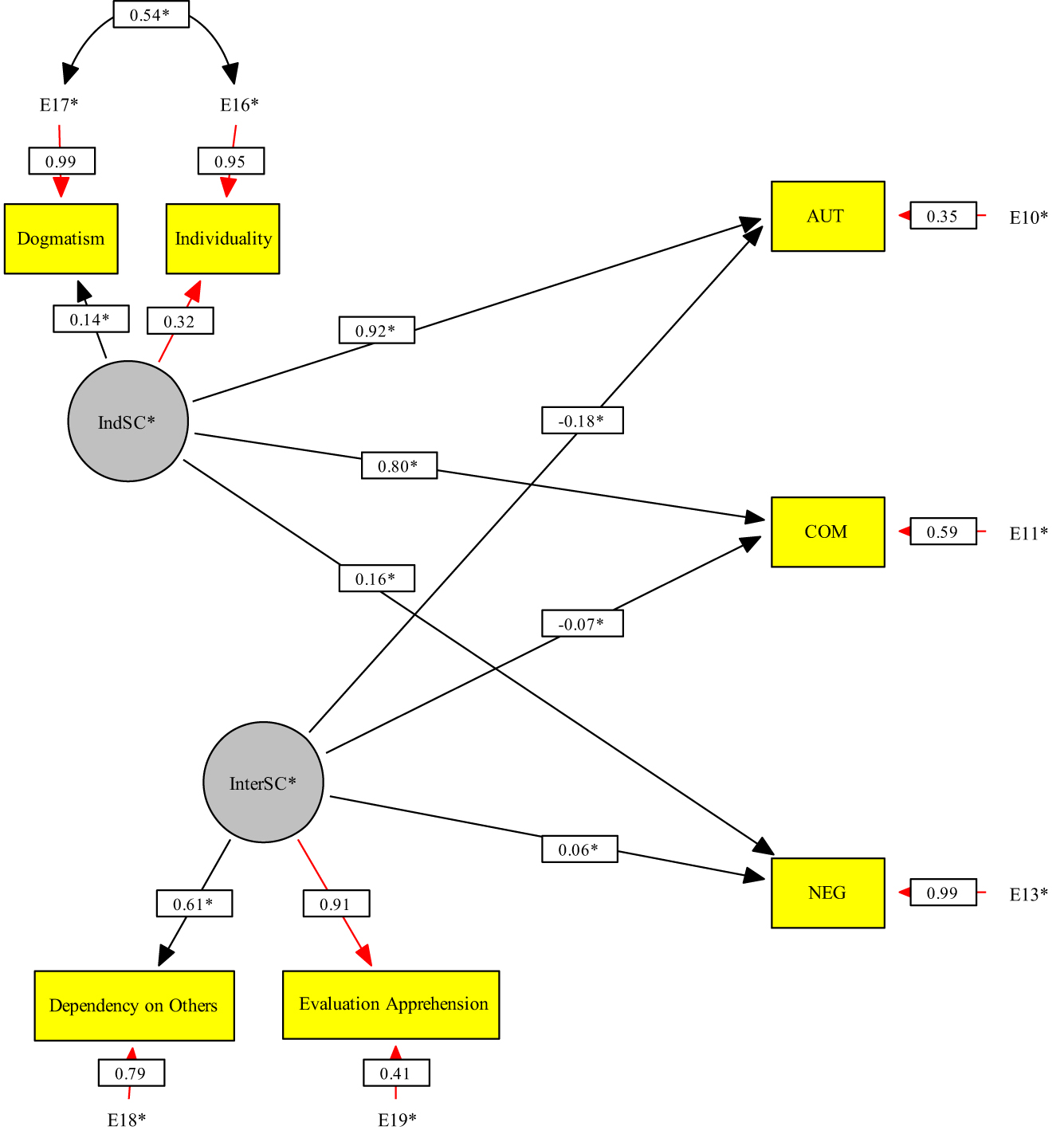

Two path models were built using EQS 6.2 (Bentler and Wu 2012) to answer three research questions. The first path model (Figure 1) concerns the first and second research questions. As Tanaka (2017a) demonstrated that three types of motivation (introjected regulation, external regulation, and amotivation) were not significant predictors of vocabulary size, the paths from these types of motivation to the test scores were deleted in the model. The second path model (Figure 2) was created in response to the third research question. As Mardia’s normalized estimate suggested that data did not show multivariate normal distribution, the parameters for both models were estimated using the Satorra-Bentler scales, using χ2 corrections for maximum likelihood. The fit indices of the models were as follows: χ2 SB (20) = 25.68, p = 0.18, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [90% CI] = 0.04 [0.00, 0.09] for the first model (Figure 1), and χ2 SB (10) = 15.75, p = 0.11, CFI = 0.97, and RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.06 [0.00, 0.12] for the second model (Figure 2). The goodness of fit of the models suggest that the hypothesized models fitted well with the data.

The path model with estimated parameters. IM = Intrinsic motivation; ID = Identified regulation; IJ = Introjected regulation; EX = External regulation; AM = Amotivation; IndSC = Independent self-construal; InterSC = Interdependent self-construal.

The path model with estimated parameters. AUT = Perceived autonomy; COM = Perceived competence; NEG = Negative peer influences; IndSC = Independent self-construal; InterSC = Interdependent self-construal.

4.2 Main analysis

4.2.1 The effects of self-construal on English vocabulary size

To answer the first research question concerning the extent to which self-construal predicts vocabulary size, two paths from independent and interdependent self-construal to the vocabulary test score were examined in the first path model (Figure 1). As shown in Table 2, neither independent self-construal nor interdependent self-construal was a significant predictor of test scores. Aligned with previous findings on the positive effects of more self-determined types of motivation on vocabulary size (Tanaka 2017a), the paths from intrinsic motivation and identified regulation to test scores were significant. Taken together, while motivation may directly influence vocabulary size, self-construal has no direct impact on it.

Parameter estimates for predictors of motivation and vocabulary size.

| Predictor | Outcome | B | SE B | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic motivation | → | Test | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.03 |

| Identified regulation | 0.13 | 0.04 | 2.81 | ||

| IndSC | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.74 | ||

| InterSC | 0.16 | 0.09 | 1.68 | ||

| IndSC | → | Intrinsic motivation | 0.41 | 0.11 | 3.76 |

| Identified regulation | 0.46 | 0.12 | 3.84 | ||

| Introjected regulation | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.58 | ||

| External regulation | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.54 | ||

| Amotivation | −0.32 | 0.13 | −2.49 | ||

| InterSC | → | Intrinsic motivation | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.65 |

| Identified regulation | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.29 | ||

| Introjected regulation | 1.46 | 0.48 | 3.00 | ||

| External regulation | 1.12 | 0.37 | 2.98 | ||

| Amotivation | −0.40 | 0.37 | −1.07 |

-

N = 155. T-values greater than |1.96| are significant at p < 0.05. IndSC = Independent self-construal; InterSC = Interdependent self-construal.

4.2.2 The effects of self-construal on motivation

To answer the second research question concerning the extent to which self-construal predicts the SDT subtypes of vocabulary learning motivation, paths from self-construal to motivation were examined in the first model (see Figure 1 and Table 2). In accordance with the initial hypotheses, independent self-construal predicted more self-determined types of vocabulary learning motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation and identified regulation) positively and amotivation negatively. Conversely, interdependent self-construal positively predicted less self-determined types of motivation (i.e., introjected regulation and external regulation). Thus, while there is a high probability of independent self-construal that influences more self-determined types of SDT motivation and amotivation, interdependent self-construal tends to be irrelevant to both, and is associated with less self-determined types of motivation, in the context of vocabulary learning.

4.2.3 The effects of self-construal on antecedents of motivation

To answer the third research question concerning the extent to which independent and interdependent self-construal predict perceived autonomy, perceived competence, and negative peer influences, path coefficients in the second path model (Figure 2) were examined. As indicated in Table 3, whereas independent self-construal positively predicted perceived autonomy and competence, interdependent self-construal was not related to any of the three dependent variables. Neither independent nor interdependent self-construal predicted negative peer influences. Considered together, those with high independent self-construal have high perceived autonomy and competence, which might lead to more self-determined types of motivation.

Parameter estimates for self-construal predicting the antecedents of motivation.

| Predictor | Outcome | B | SE B | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IndSC | → | Perceived autonomy | 2.24 | 0.60 | 3.73 |

| Perceived competence | 1.90 | 0.45 | 4.16 | ||

| Negative peer influences | 0.48 | 0.32 | 1.49 | ||

| InterSC | → | Perceived autonomy | −0.15 | 0.08 | −1.94 |

| Perceived competence | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.82 | ||

| Negative peer influences | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.71 |

-

N = 155. T-values greater than |1.96| are significant at p < 0.05. IndSC = Independent self-construal; InterSC = Interdependent self-construal.

4.2.4 The mediating roles between self-construal and motivation

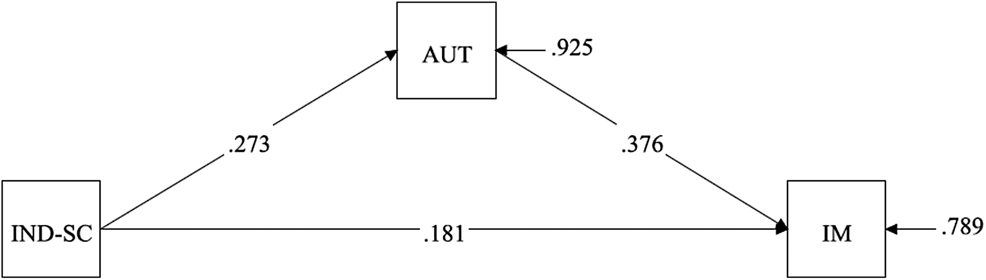

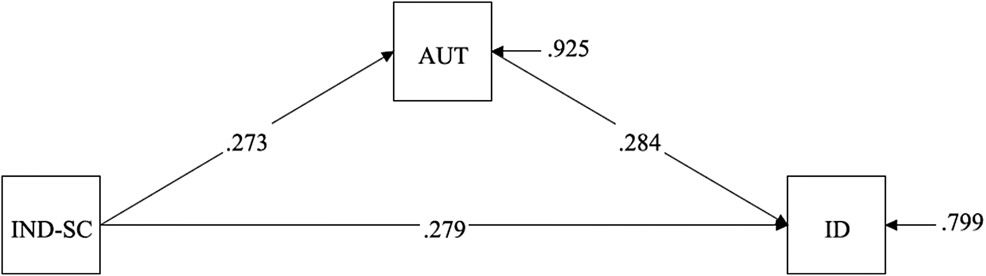

The results of the second and third research questions indicated that independent self-construal has a significant influence both on self-determined types of motivation and on its antecedents. As perceived autonomy and competence are antecedents of more self-determined types of motivation and/or amotivation, they potentially mediate the relationship between independent self-construal and motivation. To answer the fourth research question on this issue, four mediation analyses (Models 1 to 4) were performed using Mplus 8.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2017) with 2,000 bootstrap samples (Figures 3–6).

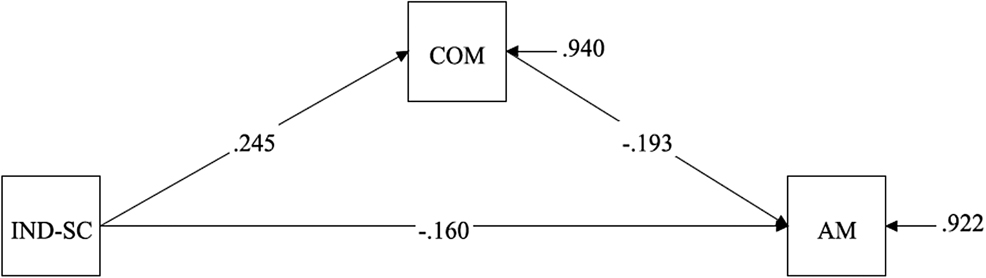

The mediation model with standardized estimates. IND-SC = Independent self-construal; AUT = Perceived autonomy; IM = Intrinsic motivation.

The mediation model with standardized estimates. IND-SC = Independent self-construal; AUT = Perceived autonomy; ID = Identified regulation.

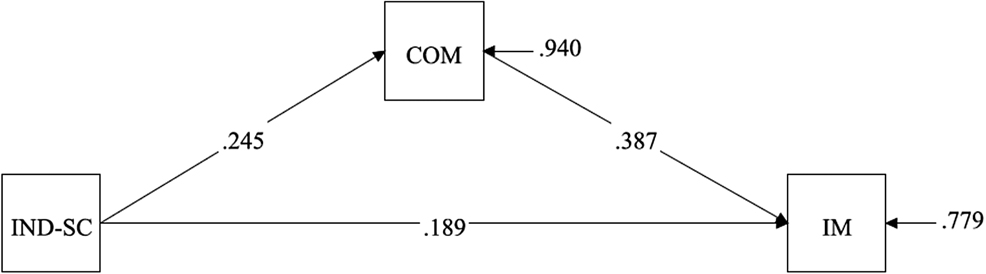

The mediation model with standardized estimates. IND-SC = Independent self-construal; COM = Perceived competence; IM = Intrinsic motivation.

The mediation model with standardized estimates. IND-SC = Independent self-construal; COM = Perceived competence; AM = Amotivation.

As the second path model revealed that interdependent self-construal and negative peer influences were irrelevant to the current research question, they were excluded from further analyses. Less self-determined forms of motivation (i.e., introjected and external regulation) were also abandoned at this stage, as they were not associated with independent self-construal as displayed in the first path model. The four combinations between the dependent variables and mediators were based on the significant link revealed in the first phase of this project (Tanaka 2017a). Table 4 displays the results of the mediation analyses.

Summary of mediation analyses.

| B | SE | t | p | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Model 1: IV (IND-SC) → Mediator (AUT) → DV (IM)

|

|||||

| IV to mediator | 0.29 | 0.07 | 4.14 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| Mediator to DV | 0.51 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 |

| Total effect of IV on DV | 0.42 | 0.09 | 4.33 | 0.00 | 0.28 |

| Direct effect of IV on DV | 0.27 | 0.09 | 2.93 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| Indirect effect of IV on DV |

0.15 (0.07, 0.26) |

0.04 |

3.12 |

0.00 |

0.10 (0.04, 0.16) |

| Model 2: IV (IND-SC) → Mediator (AUT) → DV (ID) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| IV to mediator | 0.29 | 0.07 | 4.14 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| Mediator to DV | 0.35 | 0.09 | 3.62 | 0.00 | 0.28 |

| Total effect of IV on DV | 0.48 | 0.10 | 4.52 | 0.00 | 0.35 |

| Direct effect of IV on DV | 0.37 | 0.10 | 3.56 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| Indirect effect of IV on DV |

0.10 (0.04, 0.19) |

0.03 |

2.71 |

0.00 |

0.07 (0.03, 0.14) |

| Model 3: IV (IND-SC) → Mediator (COM) → DV (IM) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| IV to mediator | 0.25 | 0.08 | 3.07 | 0.00 | 0.24 |

| Mediator to DV | 0.54 | 0.10 | 4.98 | 0.00 | 0.38 |

| Total effect of IV on DV | 0.42 | 0.09 | 4.33 | 0.00 | 0.28 |

| Direct effect of IV on DV | 0.28 | 0.10 | 2.80 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| Indirect effect of IV on DV |

0.14 (0.04, 0.26) |

0.05 |

2.48 |

0.01 |

0.09 (0.03, 0.17) |

| Model 4: IV (IND-SC) → Mediator (COM) → DV (AM) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| IV to mediator | 0.25 | 0.08 | 3.07 | 0.00 | 0.24 |

| Mediator to DV | −0.29 | 0.11 | −2.56 | 0.01 | −0.19 |

| Total effect of IV on DV | −0.34 | 0.13 | −2.53 | 0.01 | −0.20 |

| Direct effect of IV on DV | −0.26 | 0.14 | −1.87 | 0.06 | −0.16 |

| Indirect effect of IV on DV | −0.07 (−0.18, −0.02) | 0.03 | −2.00 | 0.04 | −0.04 (−0.10, −0.01) |

-

N = 155. IM = Intrinsic motivation; ID = Identified regulation; AM = Amotivation; AUT = Perceived autonomy; COM = Perceived competence; IND-SC = Independent self-construal. 95% bias corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (CI) are reported in parentheses. 95% CIs not encompassing zero indicate significant mediated effects.

The total effect of the independent variable (i.e., independent self-construal) on dependent variables (i.e., intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, or amotivation) without the mediators was significant. All the paths from the independent variable (i.e., independent self-construal) to the mediators (i.e., perceived autonomy or competence) and from the mediators (i.e., perceived autonomy or competence) to the dependent variables (i.e., intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, or amotivation) were also significant. The indirect effect of independent self-construal on motivational variables through the mediation of perceived autonomy or perceived competence was significant in all four models, as 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals did not encompass zero. When the mediators (perceived autonomy or competence) were controlled, the direct effect was no longer significant in Model 4, indicating complete mediation with amotivation as the dependent variable, while the direct effect was reduced but remained significant in the remaining three models, indicating partial mediation in Models 1 to 3.

5 Discussion

This study examined the impact of self-construal on EFL vocabulary learning. With regard to the effects of self-construal on vocabulary size (i.e., the first research question), self-construal was not a direct predictor of vocabulary size. This result contrasts sharply with the finding on the effects of motivation on L2 learning outcomes. More self-determined types of vocabulary learning motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation and identified regulation) were positive predictors of vocabulary size. Possibly, motivation was a direct predictor, as it conceptualizes a domain-specific construct. The nature of motivation was focused on and closely related to vocabulary learning. For example, intrinsic motivation refers to finding enjoyment and pleasure in vocabulary learning. It is easily conceivable that those who enjoy learning vocabulary may be more involved with L2 learning, which might lead to the development of a larger vocabulary. On the other hand, self-construal encompasses the general disposition of individuals beyond specific domains. Although self-construal influences the activation of independent and autonomous motivation (Wiekens and Stapel 2008), an individual’s orientation toward independence may vary by domain. For instance, some students may not display autonomy in learning mathematics but may be strongly autonomously involved with the study of history. As many factors beyond personal attributes influence vocabulary learning, self-construal may need to be complemented by a factor more closely tied with vocabulary learning (e.g., motivation) to exert a direct effect on vocabulary size.

Regarding the effects of self-construal on vocabulary learning motivation (i.e., the second research question), self-construal was a significant predictor of vocabulary learning motivation. As with the evidenced link between independent self-construal and more self-determined types of motivation in other academic fields (Kong and Ho 2016; Lee and Pounders 2019), the prominent role of independent self-construal was clarified to encourage more self-determined types of motivation (i.e., the determinants of vocabulary size) in the vocabulary learning context. As those with high independent self-construal tend to value independence and autonomy (Markus and Kitayama 1991), their motivation also tends to be self-determined and independent. They are inclined to enjoy and value learning more (i.e., activating intrinsic motivation and identified regulation) and are less prone to amotivation. Given the importance of more self-determined types of motivation in developing a larger vocabulary, learners with higher independent self-construal are more likely to succeed in vocabulary learning. Conversely, those with lower independent self-construal are disadvantaged in vocabulary learning as they are less likely to enjoy and value learning (i.e., the significant predictors of vocabulary size) and more prone to amotivation.

On the other hand, interdependent self-construal was associated only with less self-determined types of motivation (i.e., introjected and external regulation), but not with more self-determined types of autonomous motivation. While the salient role of interdependent self-construal was demonstrated in promoting foreign language learning motivation in prior research (Henry and Cliffordson 2013), interdependent self-construal may not play a discernible role in vocabulary learning. One possible reason for the incongruence may be contextual differences. Those with high interdependent self-construal are oriented toward social interaction. Interdependent self-construal may have played the dominant role in Henry and Cliffordson (2013), as their study context entailed a vision for future social interaction. Conversely, the context of this study was vocabulary learning, where students often learn on their own without peer interaction. Perhaps, the roles of self-construal in language learning may vary according to learning content and context. As Serafini (2020) proposed, further studies are required to clarify differential roles of self-construal in other L2 learning contexts.

Regarding the effects of self-construal on the antecedents of vocabulary learning motivation (i.e., the third research question), interdependent self-construal was not a significant predictor of perceived autonomy and competence. Learners tended to possess perceived autonomy and competence regardless of the degree of interdependent self-construal. In contrast, independent self-construal had a systematic impact on perceived autonomy and competence. Those with higher independent self-construal are more likely to have higher perceived autonomy and competence, whereas those with lower independent self-construal tend to have lower perceived autonomy and competence. Thus, it would be an advantage to possess higher independent self-construal to cultivate perceived autonomy and competence in the vocabulary learning context.

Based on the associations between independent self-construal, motivation, and perceived autonomy and competence, this study further investigated whether strongly independent self-construal affects motivation directly or via satisfying the individual’s need for autonomy and competence (i.e., the fourth research question). It revealed the significant mediating roles of perceived autonomy and competence in the relationship between self-construal and motivation. Those with higher independent self-construal tended to enjoy and value learning more, partially because of their higher perceived autonomy and/or competence. Those with higher independent self-construal were less prone to amotivation, as they tended to have higher perceived competence. Although perceived autonomy and competence may be enhanced through social factors (Ryan and Deci 2017), self-construal is a relatively rigid trait. The findings offer hope to learners with low independent self-construal, as supporting these mediators could enhance their motivation without changing their relatively unmalleable self-construal.

The dominant types of learners’ motivation tended to vary according to types of self-construal. This insight can enable teachers to provide modified assistance that enhances motivation based on students’ self-construal type. First, learners who may require the most attention are those with low independent self-construal. Learners with this type of self-construal tend to experience low perceived autonomy, low perceived competence, and a lack of motivation, and may possess lower self-determined types of motivation, resulting in the unsuccessful development of vocabulary size. Thus, this type of learner requires special care. In general, self-construal is not easily malleable, but somewhat rigid. Therefore, it is unrealistic and unnecessary to attempt to alter students’ self-construal. As perceived autonomy and competence mediate the relationships between self-construal and various types of motivation, a more realistic and feasible solution is to enhance learners’ perceived autonomy and competence. There are various ways to increase these factors. For example, as self-regulated learning is associated with self-efficacy (Mizumoto 2013), instruction for enhancing self-regulation may lead to higher self-efficacy and perceived competence. As learners have a higher perceived competence when receiving informative teacher feedback in an environment that supports autonomy (Noels 2001), providing feedback opportunities in class may also increase learners’ perceived autonomy and competence. For instance, a brief discussion of weekly vocabulary learning experiences may create opportunities to provide constructive feedback. In large classes where teacher feedback may not be feasible, learners can provide feedback to each other in pairs or groups. In addition, as perceived autonomy and competence can be enhanced through ambient support (Ryan and Deci 2017), engaging peers to monitor and support learning may also help enhance perceived autonomy and competence.

Second, learners with high interdependent self-construal require different types of assistance. SDT stipulates that significant others are key agents in promoting the internalization of extrinsic values (Ryan and Deci 2017). Since learners with high interdependent self-construal are inclined to rely on others and be swayed by external influences, the strategic use of significant social relationships (e.g., peers and teachers) would make these individuals internalize the value of learning and develop more self-determined types of motivation. For instance, as such learners are influenced by those with whom they engage, it can be assumed that they are more motivated in a learning environment where their peers are highly motivated and engaged in learning. Thus, creating a motivating learning environment would assist them in incorporating beneficial learning values from their peers. Furthermore, as these learners are more concerned with the impressions of their social contacts, teachers may promote more self-determined types of motivation by repeating learning values and virtues.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, several limitations should be addressed. First, although self-construal does not often change drastically in a short period, it does evolve with age (Takata 2000). As the participants of this study were adolescents in the process of personality development, the findings may reflect characteristics of this particular age group. Further studies could assess how age moderates the impact of self-construal on L2 learning motivation. Second, the majority of the participants in this study were male. As Henry and Cliffordson (2013) demonstrated, gender has a salient impact on self-construal. It would be worthwhile to examine how gender-related variance on self-construal accounts for L2 learning motivation. Third, as this study used self-reporting questionnaires to gather most of the data, data triangulation using multiple methods (e.g., observations and interviews) would have strengthened the validity of the findings.

Despite these limitations, this study clarified the salient role of self-construal (i.e., individual traits) in L2 learning and its underlying motivation. From an educational perspective, it is unfortunate that the study reveals that learners with a certain type of individual trait are more likely to succeed in language learning, whereas others are less likely to succeed, in particular as individual traits such as self-construal and personality are relatively unchangeable. However, identifying the negative repercussions of individual traits is a first step toward improving them. As this study demonstrated, there may be malleable mediating factors between individual traits and L2 learning outcomes that enable the development of practical supports.

From a theoretical perspective, although there is ample evidence that self-construal underlies cognition, emotion, motivation, and social behavior (Cross et al. 2011), few studies have been conducted on the roles of self-construal in the foreign language learning environment. Although self-construal is a hitherto neglected construct in L2 learning, its impact on language learning is apparent. As Serafini (2020) argued, further research on using self-construal in various learning contexts would provide new insights on L2 learning and L2 learning motivation.

English translation of the questionnaire items for Takata’s (2000) self-construal

To what extent do you agree with each of the following statements?

| Factor 1: Dogmatism (DOG) | |

| DOG1 | The best decisions are the ones I make by myself. |

| DOG2 | When I believe in an idea, I do not care what others think of it. |

| DOG3 | Even if people around me have different ideas, I stick to my beliefs. |

| DOG4 | In general, I make my own decisions. |

| DOG5 | Whether something is good or bad depends on how I think about it. |

| DOG6 | I do not care when my opinions and behaviors are different from others. |

| Factor 2: Individuality (IND) | |

| IND1 | I always try to have opinions of my own. |

| IND2 | I always know what I want to do. |

| IND3 | I always express my opinions clearly. |

| IND4 | I always speak and act with confidence. |

| Factor 3: Dependency on Others (DEP) | |

| DEP1 | It is important to maintain harmony with others. |

| DEP2 | It is important for me to be liked by others. |

| DEP3 | How I feel depends on who I am with and what circumstances I am in. |

| DEP4 | I avoid having conflicts with my groups’ members. |

| DEP5 | When I differ in opinions from others, I often accept their opinions. |

| DEP6 | I sometimes change my attitudes and behaviors depending on who I am with and what circumstances I am in. |

| Factor 4: Evaluation Apprehension (EVA) | |

| EVA1 | I care about what others think of me. |

| EVA2 | Sometimes I am worried about how things will turn out and have difficulty in getting started. |

| EVA3 | I care about how others evaluate me. |

| EVA4 | When interacting with others, I care about my relationships with them and their social status. |

-

All the questionnaire items are randomly ordered 6-point Likert scale items.

References

Agawa, Toshie & Osamu Takeuchi. 2016. Validating self-determination theory in the Japanese EFL context: Relationship between innate needs and motivation. Asian EFL Journal 18(1). 7–33.Suche in Google Scholar

Aizawa, Kazumi & Masamichi Mochizuki. 2010. Eigo goi shidou no jissen aidia shuu [Practical ideas for English vocabulary instruction]. Tokyo: Taishuukan.Suche in Google Scholar

Apple, Matthew, Joseph Falout, & Glen Hill. 2013. Exploring classroom-based constructs of EFL motivation for science and engineering students in Japan. In Matthew Apple, Dexter Silva, & Terry Fellner (eds.), Language learning motivation in Japan, 54–74. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783090518-006Suche in Google Scholar

Bentler, Peter & Eric Wu. 2012. EQS for windows (Version 6.2) [Computer software]. Multivariate Software, Inc.Suche in Google Scholar

Carreira, Junko Matsuzaki, Koken Ozaki, & Tadahiko Maeda. 2013. Motivational model of English learning among elementary school students in Japan. System 41(3). 706–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.07.017.Suche in Google Scholar

Cross, Susan, Erin Hardin, & Berna Gercek-Swing. 2011. The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Review 15(2). 142–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310373752.Suche in Google Scholar

Cross, Susan & Laura Madson. 1997. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin 122(1). 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5.Suche in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltán & Stephen Ryan. 2015. The psychology of the language learner revisited. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315779553Suche in Google Scholar

Henry, Alastair & Christian Cliffordson. 2013. Motivation, gender, and possible selves. Language Learning 63(2). 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12009.Suche in Google Scholar

Joe, Hye-Kyoung, Phil Hiver, & Ali H. Al-Hoorie. 2017. Classroom social climate, self-determined motivation, willingness to communicate, and achievement: A study of structural relationships in instructed second language settings. Learning and Individual Differences 53. 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.11.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Kashima, Emiko & Elizabeth Hardie. 2000. The development and validation of the relational, individual, and collective self-aspects (RIC) scale. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 3(1). 19–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00053.Suche in Google Scholar

Kikuchi, Keita. 2009. Listening to our learners’ voices: What demotivates Japanese high school students? Language Teaching Research 13. 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168809341520.Suche in Google Scholar

Kong, Tony & Violet Ho. 2016. A self-determination perspective of strengths use at work: Examining its determinant and performance implications. The Journal of Positive Psychology 11(1). 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1004555.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Seungae & Kathrynn Pounders. 2019. Intrinsic versus extrinsic goals: The role of self-construal in understanding consumer response to goal framing in social marketing. Journal of Business Research 94. 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.039.Suche in Google Scholar

Linacre, Michael. 2013. Winsteps (Version 3.80.0) [Computer software]. Winsteps.com.Suche in Google Scholar

Markus, Hazel & Shinobu Kitayama. 1991. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review 98(2). 224–253.http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224.10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224Suche in Google Scholar

McEown, Maya, Kimberly Noels, & Kristie Saumure. 2014. Students’ self-determined and integrative orientations and teachers’ motivational support in a Japanese as a foreign language context. System 45. 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.06.001.Suche in Google Scholar

McEown, Maya & Quint Oga-Baldwin. 2019. Self-determination for all language learners: New applications for formal language education. System 86. 102–124.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102124.Suche in Google Scholar

Mizumoto, Atsushi. 2013. Effects of self-regulated vocabulary learning process on self-efficacy. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 7(3). 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2013.836206.Suche in Google Scholar

Mizumoto, Atsushi & Osamu Takeuchi. 2009. Examining the effectiveness of explicit instruction of vocabulary learning strategies with Japanese EFL university students. Language Teaching Research 13(4). 425–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168809341511.Suche in Google Scholar

Muthén, Linda & Bengt Muthén. 2017. Mplus (Version 8.0) [Computer software]. Muthén and Muthén.Suche in Google Scholar

Nation, Paul. 2001. Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139524759Suche in Google Scholar

Noels, Kimberly. 2001. Learning Spanish as a second language: Learners’ orientations and perceptions of their teachers’ communication style. Language and Learning 51(1). 107–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00149.Suche in Google Scholar

Noels, Kimberly, Richard Clément, & Luc Pelletier. 1999. Perceptions of teachers’ communicative style and students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The Modern Language Journal 83(1). 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00003.Suche in Google Scholar

Noels, Kimberly, Nigel Mantou Lou, Dayuma I. Vargas Lascano, Kathryn E. Chaffee, Ali Dincer, Ying Shang Doris Zhang, & Xijia Zhang. 2020. Self-determination and motivated engagement in language learning. In Martin Lamb, Kata Csizér, Alastair Henry, & Stephen Ryan (eds.), The palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning, 95–115. Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-28380-3_5Suche in Google Scholar

Noels, Kimberly, Luc Pelletier, Richard Clément, & Robert Vallerand. 2000. Why are you learning a second language? Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. Language Learning 50(1). 57–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00111.Suche in Google Scholar

Ryan, Richard & Edward Deci. 2017. Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press.10.1521/978.14625/28806Suche in Google Scholar

Serafini, Ellen. 2020. Further situating learner possible selves in context: A proposal to replicate Henry and Cliffordson (2013) and Lasagabaster (2016). Language Teaching 53(2). 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444819000144.Suche in Google Scholar

Singelis, Theodore. 1994. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20(5). 580–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205014.Suche in Google Scholar

Takata, Toshitake. 1993. Social comparison and formation of self-concept in adolescent: Some findings about Japanese college students. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology 41(3). 339–348. https://doi.org/10.5926/jjep1953.41.3_339.Suche in Google Scholar

Takata, Toshitake. 2000. On the scale for measuring independent-interdependent view of self. Bulletin of Research Institute of Nara University 8. 145–163.Suche in Google Scholar

Takata, Toshitake. 2003. Self-enhancement and self-criticism in Japanese culture: An experimental analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 34(5). 542–551.https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022103256477.Suche in Google Scholar

Tanaka, Mitsuko. 2013. Examining kanji learning motivation using self-determination theory. System 41(3). 804–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.08.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Tanaka, Mitsuko. 2017a. Examining EFL vocabulary learning motivation in a demotivating learning environment. System 65. 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.01.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Tanaka, Mitsuko. 2017b. Factors affecting motivation for short in-class extensive reading. The Journal of Asia TEFL 14(1). 98–113. https://doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2017.14.1.7.98.Suche in Google Scholar

Tseng, Wen-Ta & Norbert Schmitt. 2008. Toward a model of motivated vocabulary learning: A structural equation modeling approach. Language Learning 58(2). 357–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2008.00444.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Vandergrift, Larry. 2005. Relationships among motivation orientations, metacognitive awareness, and proficiency in L2 listening. Applied Linguistics 26(1). 70–89.https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amh039.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Qi & Michael Ross. 2005. What we remember and what we tell: The effects of culture and self-priming on memory representations and narratives. Memory 13(6). 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210444000223.Suche in Google Scholar

Wiekens, Carina & Diederik Stapel. 2008. I versus we: The effects of self-construal level on diversity. Social Cognition 26(3). 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2008.26.3.368.Suche in Google Scholar

Yashima, Tomoko, Rieko Nishida, & Atsushi Mizumoto. 2017. Influence of learner beliefs and gender on the motivating power of L2 selves. The Modern Language Journal 101(4). 691–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12430.Suche in Google Scholar

Zheng, Yongyan. 2012. Exploring long-term productive vocabulary development in an EFL context: The role of motivation. System 40(1). 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.01.007.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2020 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- A double-edged sword: Metaphor and metonymy through pictures for learning idioms

- The functional roles of lexical devices in second language learners’ encoding of temporality: A study of Mandarin Chinese-speaking ESL learners

- The same cloze for all occasions?

- The effect of written text on comprehension of spoken English as a foreign language: A replication study

- Cut-offs and co-occurring gestures: Similarities between speakers’ first and second languages

- Bilingual patterns of path encoding: A study of Polish L1-German L2 and Polish L1-Spanish L2 speakers

- Concordancing in writing pedagogy and CAF measures of writing

- D-linked and non-d-linked wh-questions in L2 French and L3 English

- Effects of pragmatic instruction on EFL teenagers’ apologetic email writing: Comprehension, production, and cognitive processes

- Music training and the use of songs or rhythm: Do they help for lexical stress processing?

- Second language processing of English past tense morphology: The role of working memory

- Recasts versus clarification requests: The relevance of linguistic target, proficiency, and communicative ability

- The role of self-construal in EFL vocabulary learning

- The cross-sectional development of verb–noun collocations as constructions in L2 writing

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- A double-edged sword: Metaphor and metonymy through pictures for learning idioms

- The functional roles of lexical devices in second language learners’ encoding of temporality: A study of Mandarin Chinese-speaking ESL learners

- The same cloze for all occasions?

- The effect of written text on comprehension of spoken English as a foreign language: A replication study

- Cut-offs and co-occurring gestures: Similarities between speakers’ first and second languages

- Bilingual patterns of path encoding: A study of Polish L1-German L2 and Polish L1-Spanish L2 speakers

- Concordancing in writing pedagogy and CAF measures of writing

- D-linked and non-d-linked wh-questions in L2 French and L3 English

- Effects of pragmatic instruction on EFL teenagers’ apologetic email writing: Comprehension, production, and cognitive processes

- Music training and the use of songs or rhythm: Do they help for lexical stress processing?

- Second language processing of English past tense morphology: The role of working memory

- Recasts versus clarification requests: The relevance of linguistic target, proficiency, and communicative ability

- The role of self-construal in EFL vocabulary learning

- The cross-sectional development of verb–noun collocations as constructions in L2 writing