Abstract

A regular Desktop Grid bag-of-tasks project can take a lot of time to complete computations. An important part of the process is tail computations: when the number of tasks to perform becomes less than the number of computing nodes. At this stage, a dynamic replication could be used to reduce the time needed to complete computations. In this paper, we propose a mathematical model and a strategy of dynamic replication at the tail stage. The results of the numerical experiments are given.

1 Introduction

Desktop Grid is a high-throughput computing paradigm that provides a cheap, easy to install and support, and potentially powerful computing tool. Desktop Grid is based on a distributed computing system which uses idle time of non-dedicated geographically distributed generalpurpose computing nodes (usually, personal computers) connected over the Internet [8]. Desktop Grids popularity is motivated by quick growth of the number of personal computers, and a large increase in their performance, as well as Internet expansion and rise of connection speed. Volunteer computing is a form of Desktop Grid. The first large volunteer computing project, SETI@home, was launched in 1999, providing the basis for development of the BOINC platform. By now, there are several middleware systems for Desktop Grid computing. However, the open source BOINC platform [6] is nowadays considered as a de facto standard among them. Today there are more than 60 active BOINC-based projects using more than 15 million computers worldwide [1]. So, Desktop Grids hold their place among other high-performance systems, such as Computing Grid systems, computing clusters, and supercomputers.

A Desktop Grid consists of a (large) number of computing nodes and a server which distributes tasks among the nodes. The workflow is as follows. A node asks the server for work; the server replies sending one or more tasks to the node. The node performs calculations and when it finishes it, it sends the result (which is a solution of a task or an error report) back to the server. The detailed description of the computational process in BOINC-based Desktop Grids is given in [2].

Because of their nature, task scheduling in Desktop Grids is an important problem. Among other special problems, there is the “tail” computations problem. It is related to a final stage of computations in a Desktop Grid, when the number of tasks is less than the number of computing nodes. Because of the unreliability of the nodes this stage can take much time. Therefore, special mathematical models are needed to reduce duration of the final stage. In this paper a stochastic mathematical model of the “tail” computations based on finishing task probability distribution function is considered.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 describes the motivation and related works. Section 3 is devoted to a mathematical model of the “tail” computations. Section 4 presents the results of numerical experiments. Finally, Section 5 contains final remarks and conclusions.

2 Motivation and Related Works

As it was mentioned in Section 1, BOINC is the most popular Desktop Grid middleware, so we consider scheduling problem based on BOINC workflow.

BOINC is based on the client-server architecture. The client part is software, which is able to employ idle resources of a computer for computations within one or multiple BOINC projects. It is available for computers with various hardware and software characteristics. The server part of BOINC consists of several subsystems responsible for tasks generation, distribution, results verification, assimilation, etc. (see [2]).

BOINC employs several mechanisms to deal with clients’ unreliability. One of them is replication. For each computational task, BOINC holds multiple independent copies of the same task which are called replicas. The replication level is about 2-5 and is an option of a BOINC project. Replicas are computed independently with different computing nodes, and then their results are compared with the aims of verifying the solution. Quorum is the number of equal replicas results needed to verify a task result. This mechanism is used to overcome processing errors and sabotage. Moreover, BOINC settings allow to create and distribute more task replicas dynamically as needed (for example, dynamic replication is used in papers [4, 5, 14] and others).

BOINC employs PULL model to interact with computing nodes. This allows to employ computing nodes that have no direct access to the Internet. But this also leads to impossibility to determine that a node abandons the Desktop Grid and will never return results. So, BOINC uses a deadline value which is set for each task instance to limit tasks completion time. If the server does not get a result before the deadline, the task instance is considered lost.

The replication mechanism as a form of redundant computing serves a number of purposes. The main purpose is to increase reliability by increasing the probability to obtain the correct answer in time even if some nodes become unavailable without having finished the task. This helps, in its turn, to improve efficiency (in particular, throughput of successful results). The same time it significantly decreases accessible computing performance. So, the replication value should be as low as possible to provide verified results in time. The problem of search for optimal replication parameters is studied in practice in [12], where a simple mathematical model of tasks computations is presented. Based on this model, the author determines the most suitable replication value using log data of NetMax@home project [13].

A valuable problem of task scheduling in Desktop Grids is optimization of the so called “tail” computations. A distributed computational experiment involving a batch of tasks inherently consists of two stages (see Fig. 1). At the first one the number of tasks is greater than the number of computing nodes (usually it much more in the very beginning). At this stage, available computing power limits the performance, so it is reasonable to supply each node with a unique task (without replication; from the point of view of the makespan replication is useless as it was shown in [7]). With time, the number of unprocessed tasks decreases until it is equal to the number of computing nodes: then the second stage called the “tail” starts. At this stage there is an excess of computing power which could be used to implement redundant computing to reduce overall computing time.

Two stages of batch completion in a Desktop Grid

A number of research problems related to specifics of Desktop Grids are connected to the two-staged batch completion. One of them is the fastest batch of tasks completion. In practice, the “tail” computations can take a long time (usually, about two or three times greater than deadline value) because of unreliable hosts. A computational network does not have information on the current status of tasks completion. So, the “tail” can accumulate a lot of nodes that have already abandoned the computing network. As a certain task assigned to such node violates the deadline, it is assigned again to a different node, possibly unreliable too. So, this prolongs the “tail” duration. The solution to the problem is in the redundant computing: currently processing tasks are assigned to vacant computing nodes. This strategy significantly increases the chances that at least one copy is solved in time. Employing this strategy, one should take into account characteristics of computational nodes (availability, reliability, computing power, etc.), processing the same task, accumulated task processing time, expected task completion time, and so on.

This problem is described in [8], where a simple mathematical model is proposed. In this paper we propose more complex mathematical model which provides better results.

The fastest batch of tasks completion problem is more complex if a new batch of tasks should be started immediately after the current batch completion. In this case, redundant computing reduces accessible computing power. One more complicated case is connected to interdependency between the tasks of the new batch and completion of certain tasks in the current batch.

The performance improvements resulting from task replication of batch parallel programs running on a SNOW system of distributed computing is analyzed in [7]. The authors show that task replication can result in significant speedup improvements, and derived formulas to calculate it. Also, for some workloads when the reliability of a workstation is low, replication can also improve efficiency. Likewise, as job parallelism increases, replication becomes even more beneficial in improving speedup. In the paper, the problem of extra workstations distribution among the tasks with the aim of speedup improvements is also studied. Based on special mathematical models and workload models, it is shown that in case of workstations excess, it is better to increase the number of replicated tasks than to increase the replication level. If there is only one extra workstation, it is better to allocate the extra workstation to the least replicated task. Finally, if there are extra workstations to distribute among two identical programs, distributing the workstations equally between the two programs gives least mean response time for tightly coupled workload and giving all the extra workstations to one of the programs gives least mean response time for loosely coupled workload. Lastly, an analysis of the trade-off between using an extra workstation to increase parallelism or to increase replication is presented. Authors argue that replication can be more beneficial than parallelism for a range of tightly-coupled workloads.

The “tail” computations problem is also studied in [4, 11]. In [11] the following four task replication strategies are proposed and experimentally tested:

Resource Prioritization — assign tasks to the “best” hosts first.

Resource Exclusion Using a Fixed Threshold — exclude some hosts and never use them to run application tasks, where filtering can be based on a simple threshold such as hosts clock rates.

Resource Exclusion via Makespan Prediction — remove hosts that would not complete a task, if assigned to them, before some expected application completion time.

Task Replication—task failures near the end of the application, and unpredictably slow hosts can cause major delays in application execution. This problem can be remedied by means of replicating tasks on multiple hosts, either to reduce the probability of task failure or to schedule the application on a faster host.

In [4] the following strategy is proposed: When the tail stage starts, all unreliable resources are occupied by instances of different tasks, and the queue is empty. Additional instances are enqueued by a scheduling process: first to the unreliable pool then to the reliable one. This scheduling process is controlled by four user parameters:

Maximal number of instances sent for each task to the unreliable system from the start of the tail stage.

Deadline for an instance.

Timeout, or the minimal time to wait before submitting another instance of the same task.

Ratio of the reliable and unreliable pool sizes.

3 Mathematical Model

To address the “tail” computations problem we present the following mathematical model. It is a normal practice to assign for each batch of tasks (BoT) a certain number of nodes N registered in the Desktop Grid network. Whereas a volunteer or institutional computational networks are normally heterogeneous, we define by ak a computing performance of k-th node, where k = 1,.., N.

The problem of estimating the computational complexity for each task in a BoT can be challenging in the presence of any iterative computations. However integration or statistical problems are examples where it is possible to know the computational task complexity T in advance. Therefore, for each task in a BoT we define a working time needed for k-th node to finish a task as:

Each computing node does not work continuously, so suppose that there is a cumulative probability distribution function (CDF) Fk(t) describing the probability of k-th node to finish a task in certain time. The shape of this CDF and its parameters are discussed in a subsequent section. With d > Tk we define a deadline, that is a time period between task submission to the node, and the moment when the server will reject computation result from that node. Having all thing considered, Fk(c) is probability to successfully finish a task submitted at t = 0 to k-th node before time c, and

Redundant computing can be used to reduce the time needed to finish a BoT. At the beginning of the second stage, when a node comes to the server, there is no unique tasks left (see Fig. 1) and N –1 active tasks are already running on the other nodes. If we make a redundant replication of any running task and send its copy to a free node, the probability to finish that task earlier will increase. Formally, this idea can be described with the rule of addition of non-mutually exclusive events.

Suppose, that a probability of task completion before time c on the node l, where it was started at tl, is given by Fl(c – tl). If we also assign that same task to the freed node k, at the moment tk > tl, there will also appear a nonzero probability that a node k will return a result before c, a Fk(c – tk). Therefore, a probability that any of the nodes l or k will return it’s result before c is given by:

At the same time, a probability that both nodes miss their deadlines is given by

We denote with

where

The maximum number of these functions is N and is reduced continuously as long as tasks complete.

Using the mathematical model described above, one can try to answer the following question: What task is better to replicate in order to reduce “tail” computations? A BoT is finished when the last task of the batch is finished. Therefore, when node k arrives at time tk, it is reasonable to equip it with a replica of the task that has the worst probability to be finished before the others. FT(t) by definition, is strictly increasing function of t. However, sign(FTi – FTj) can switch any number of times for any pair of tasks i ≠ j on [tk, +∞) complicating the identification of the longest predicted task. On the other hand, we know exactly that replication at node k can meaningfully rise FT for t ∈ [tk, tk + d] only. The necessary task than can be defined as:

where FTi (tk + d) is the probability that task Ti will be finished before the moment tk + d.

Taking into account that the problem defined in Eq. 4 has a discrete nature, various simplifications can be purposed for those cases where a comparison between different FTi can be derived analytically based on task submission history. The generic case is accessible by a numerical approximation of each FT that, following our experience, does not require more than 100 reference points and is best done linearly because of oscillations of higher order polynomials at CDF singular points (see below).

4 Numerical Experiments

We model a client computer activity by a sequence of time periods of availability τa and unavailability τu. When a node k is available, it dedicates all its CPU power ak to the current task assigned to it. When a node becomes unavailable, a task computation is immediately suspended and its subsequent resume does not have any additional computational cost. None of internal client machine CPU time scheduling policies are considered.

The work of B. Javadi et al. [9] — a statistical analysis of 230,000 host activity tracks of SETI@home project — has showed a presence of 21% of tracks where τa and τu periods were statistically independent. Activity tracks with the same statistics can be understood as implementations of the same stochastic ergodic process. This process is simple to analyze analytically and permits a random generation of the track statistics without any information loss. To describe such process, it is sufficient to specify the distribution functions for both τa and τu periods. In [10] the same authors used their previous results, and the discovered ergodic tracks have been additionally classified into six clusters with a subsequent fit of τa and τu probability densities by well known analytic distributions. The results of this fit are given in Table 4 of the cited work and were used in our track generator. For convenience, we repeat the probability density functions (PDF) for all six clusters in Fig. 2.

Availability (a) and unavailability (b) per-cluster probability density distributions.

In any ergodic process, integration over ensembles can be replaced with integration over time. In our simulations, we use both cases depending on convenience. It should be stressed, however, that some care must be taken in the case of track ensemble generation. When a particular track is used to simulate node activity, the total number of τa + τu periods is typically low, so the statistical correctness of track starting moment cannot be neglected.

First, we calculate analytically the mean available τa and mean unavailable τu periods. With these values, we define a probability to find a computational node in available state, that is τa/(τa + τu), and use this probability to randomly generate starting state of each new track. Next, we note that track can start at any phase of its first state. A forward recurrence timeτe is defined as the time until the next state change moment. If the process started from available state, τe statistics depends on τa cumulative distribution Fτa only (or a τu distribution if a node was started from unavailable state). The τe CDF is derived in a point process renewal theory, see [3]:

4.1 Task completion time statistics

In the following simulation, we set the same computing power for all the nodes, so that αi = αj = α and does not depend on the node’s statistical cluster. In this case, we can address a task complexity T using time units (hours), that is equal to the task complexity that can be finished during time T of a continuous computation on any node. For the activity track random generator of each cluster, we continuously send the same task, recording its completion time. A task completion time is defined as a period between its submission moment and a node report with an infinite deadline (the node is always available at these moments). For each cluster, a statistical ensemble consisting of 100,000 completion times was collected. Given these statistical ensembles, an experimental PDF was calculated.

In Fig. 3 we show the PDF bar-plots of a single task completion time for all clusters. Each distribution has a notable peak on its left side corresponding to the case when a node was available from the task start and until its completion T. A theoretical probability of this event is not zero and is given by 1 – Fe(T), see Eq. 5. A corresponding CDF of a task completion time Fk is not smooth and has a singularity of the first kind at T, so the corresponding ~ δ behavior in each PDF is not surprising.

Task completion time probability density distributions for each cluster. The task complexity T =168h (1 week).

All six clusters have notably different dispersion. However, their shapes are comparable: a starting peak at T followed by a smooth maximum with a long decay tail. In a single cluster, dispersion also depends on the task complexity T, because it defines a mean number of availability periods sufficient to complete a task. By varying T it is possible to observe nearly all variety of typical shapes present on Fig. 3 for any single cluster.

4.2 A BoT computations simulation

In the following simulation, the BoT is composed of a number of equal complexity tasks. Here we consider the case when the total number of tasks is much greater than the number of computing nodes N. It means that a BoT startmoment is far in the past that no correlations related with its submit heterogeneity can be observed at the final stage. We start our simulations with the number of free tasks exactly equal to the number of nodes. At t0 = 0 each node is equipped with a task pending from previous computation and will complete it successfully at t > t0 requesting for the new one. The time moment with the system configuration described above, appears in any computation, independently of the deadlines due to the replicate limit in real servers. It is convenient to denote a set of tasks left at t0 as TL, with ∣TL∣ = N.

The time period between two subsequent requests for a new task that a node sends to the server is known as the turnaround time, τta. Turnaround values are random, and in our simplified model they depend on the node activity track statistics, task difficulty T and deadline. In our simulations, τta CDF was obtained experimentally for a given set of parameters (the 5-th cluster, T =168h, d = 2T =336h). We demonstrate the results based on the 5th cluster because all the clusters show similar behavior. Unlike the task completion distributions with deadline ignored, τta have two singularities: the first one at T and the second one at d. The other features of τta statistics are similar to

To generate a time (after t0) when each node will return to the server to take one of TL tasks, we calculate a forward recurrence time distribution for a turnaround process (same as in Eq. 5) and use a von Neumann random number generator based on that distribution, which is experimental this time.

In Fig. 4 a fraction of nodes ηTL(t) equipped with unique tasks from T set simulated for 1000 jobs is shown. As it can be seen, a function ηTL (t) mean value linearly grows until the second stage tII starts, that is defined as the moment when ηTL (tII) = 1.

A fraction of nodes ηTL(t) equipped with unique tasks for default BOINC policy for the 5-th cluster with T =168h and d =336h.

The second stage represented in this simulation corresponds to the default BOINC policy and illustrates a BoT completion problem considered in this paper. The default BOINC policy does not have any sense of BoT completeness: when a single task is sent to a computational node, the server will do nothing until either the node response arrives or a deadline comes. Therefore, if the node does not answer until the deadline, a task is left active and will be sent again to the next upcoming node.

From Fig. 4 we observe that ηTL(t) cut dispersion increases beginning from the first deadline occurrences after t0. The maximum of dispersion is reached near tII + d moment and a multiply deadlines stretch for a time notably greater than the “best” BoT completion time (tII + T). Observation of the worst case in real computations is unacceptable; in the final subsection we will see how the situation changes when dedicated server policies are used.

4.3 BoT completion time simulations

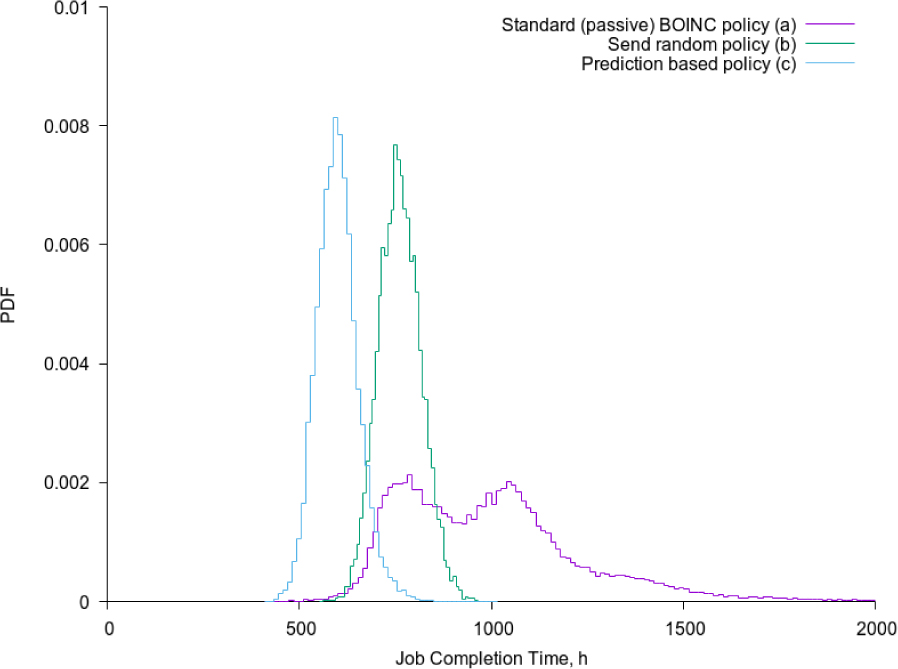

The BoT completion time tend is the moment when its last task result was reported by a computational node. First, on Fig. 5 we observe simulation results of tend PDF for the standard BOINC policy. Theoretically, if all nodes arrive at the same time at t0 and do not have unavailability periods, the job completion time is equal to T. Beyond this moment tend PDF is exactly zero. However, as it can be seen on the plot, this case has negligible probability. A notable shortest tend probabilities appear at times nearly twice greater than T. Then, we see the first maximum at nearly 750h. This corresponds to the case when there were no missing deadlines. The second maximum at 1200h correspond to the case where some tasks suffered exactly one deadline. The small subsequent peak corresponds to two deadlines. Presence of the long tail on the right indicates a nonzero probability that even more subsequently deadlines can be missed.

BoT completion time distributions: 5-th cluster, T=168h, d=336h. The standard BOINC (a), random (b) and the Eq. 4 (c) policies are present.

During the second phase, the number of tasks left is reducing continuously. In a standard policy considered above, each node becomes idle by returning a successfully completed task. However if we send a redundant replicates of the running tasks left to these idle nodes, we expect that the probability distribution of tjob will change. In the following simulation, instead of making a node idle, we send to it a randomly selected task from those that are still not finished. This way a redundant replication appears and no nodes are left idle. As a result, we observe an absence of the missing deadline peaks on tjob–rand PDF, see Fig. 5. So the deadline problem that brings long tail in tjob distribution can be solved simply with a “random” policy. A Gaussian-like distribution obtained, indicates on the good approximation to the central limiting theorem for the sum of availability and unavailability periods for a TL set consisting of only 50 tasks. In the case considered, a mean availability period is less than T so the statistics was sufficient, however a deviations may happen if this criteria is not satisfied.

Random task assignment produces redundant replication for each task without any account that a given task could be already replicated. The policy we consider in this paper is addressed to select such task for each upcoming free node, that has the worst predicted probability to be completed without redundant replication. The simulation results for this case is shown with the curve (c) in Fig 5. In addition to the properties observed for the random policy, in this case the mean job completion time is notably reduced.

5 Conclusions and future work

BOINC-based Desktop Grids are widely used to perform long-running scientific computing projects involving thousands of volunteers. BOINC handles huge amount heterogeneous computing tasks and distributed them among thousands of heterogeneous unreliable computing nodes. That is why task scheduling plays crucial role in providing computing performance. The scheduling problem is complicated by the nature of Desktop Grids.

The “tail” computations is one of the important problems in the domain of task scheduling. It arises when the number of tasks become less than the number of computing nodes. Because of unreliability of computing nodes the “tail” stage can take much time despite of excess of available computing power. The special mathematical models-based dynamic replication strategies can be employed to solve this problem.

In this paper we propose a new mathematical model which is based on known in advance probability distribution functions describing the probability of a node to finish a task in certain time. These functions can be constructed based on computing nodes statistics. Using probability distribution functions we estimate the expected task finishing times and propose to equip free node with a replica of the task that has the worst probability to be finished before the others. So, it will reduce the time needed to finish the “tail” stage of computations.

Our numerical experiments based on wide simulations show advances of the approach. Also, there are different criteria which could be used to optimize the “tail” stage of computations. The examples of these criteria are mean computing time reduction, game theoretical multi-objective payoffs, or look-ahead criteria, etc. These are the possible directions of our future work.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank to UNAM’s DGAPA (Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico), that within it’s PREI program made it possible to collaborate with Evgeny Ivashko personally during the 14/04/2015 – 3/07/2015 period. This work is also partially supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant numbers 16-07-00622 and 15-29-07974).

References

[1] BOINCstats. In https://boincstats.com, 2017-06-22.10.15210/ee.v22i1.11490Search in Google Scholar

[2] David P. Anderson. Boinc: A system for public-resource computing and storage. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE/ACM International Workshop on Grid Computing, GRID ’04, pages 4–10, Washington, DC, USA, 2004. IEEE Computer Society. ISBN 0-7695-2256-4.10.1109/GRID.2004.14. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/GRID.2004.14.10.1109/GRID.2004.14Search in Google Scholar

[3] Soren Asmussen. Applied Probability and Queues. Springer, 2 edition, 2003. ISBN 0-387-00211-1.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Orna Agmon Ben-Yehuda, Assaf Schuster, Artyom Sharov, Mark Silberstein, and Alexandru Iosup. Expert: Pareto-efficient task replication on grids and a cloud. In Parallel & Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), 2012 IEEE 26th International, pages 167–178. IEEE, 2012.10.1109/IPDPS.2012.25Search in Google Scholar

[5] Y. Brun, G. Edwards, J. Y. Bang, and N. Medvidovic. Smart redundancy for distributed computation. In 2011 31st International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems, pages 665–676, June 2011. 10.1109/ICDCS.2011.25.10.1109/ICDCS.2011.25Search in Google Scholar

[6] T. Estrada, D.A. Flores, M. Taufer, P.J. Teller, A. Kerstens, and D.P. Anderson. The effectiveness of threshold-based scheduling policies in BOINC projects. In e-Science and Grid Computing, 2006. e-Science’06. Second IEEE International Conference on, pages 88–88. IEEE, 2006.10.1109/E-SCIENCE.2006.261172Search in Google Scholar

[7] Gaurav D Ghare and Scott T Leutenegger. Improving speedup and response times by replicating parallel programs on a SNOW. In Workshop on Job Scheduling Strategies for Parallel Processing, pages 264–287. Springer, 2004.10.1007/11407522_15Search in Google Scholar

[8] Evgeny Ivashko. Mathematical model of a "tail" computation in a desktop grid. In Proceedings of the XIII International Scientific Conference on Optoelectronic Equipment and Devices in Systems of Pattern Recognition, Image and Symbol Information Processing, pages 54–59. Southwest State University, Faculty of Fundamental and Applied Informatics, Department of Computer Science, Kursk, Russia, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Bahman Javadi, Derrick Kondo, J-M Vincent, and David P Anderson. Mining for statistical models of availability in large-scale distributed systems: An empirical study of seti@ home. In Modeling, Analysis & Simulation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems, 2009. MASCOTS’09. IEEE International Symposium on, pages 1–10. IEEE, 2009.10.1109/MASCOT.2009.5367061Search in Google Scholar

[10] Bahman Javadi, Derrick Kondo, Jean-Marc Vincent, and David P. Anderson. Discovering statistical models of availability in large distributed systems: An empirical study of seti@home. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst., 22(11):1896–1903, November 2011. ISSN 1045-9219. 10.1109/TPDS.2011.50. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TPDS.2011.50.10.1109/TPDS.2011.50Search in Google Scholar

[11] D. Kondo, A.A. Chien, and H. Casanova. Scheduling task parallel applications for rapid turnaround on enterprise desktop grids. 5(4):379–405, oct 2007. ISSN 1570-7873, 1572-9184. 10.1007/s10723-007-9063-y.10.1007/s10723-007-9063-ySearch in Google Scholar

[12] I. Kurochkin. Determination of replication parameters in the project of the voluntary distributed computing NetMax@home. In International scientific conference "High technologies. Business. Society." 14-17.03.2016, Borovets, Bulgaria, pages 10–12, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[13] I.I. Kurochkin. The voluntary distributed computing project net-max@home. In Distributed computing and grid-technologies in science and education: book of abstracts of the 6th international conference, GRID, pages 233–258, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[14] J. Sonnek, A. Chandra, and J. Weissman. Adaptive reputation-based scheduling on unreliable distributed infrastructures. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, 18(11):1551– 1564, Nov 2007. ISSN 1045-9219. 10.1109/TPDS.2007.1094.10.1109/TPDS.2007.1094Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Yevgeniy Kolokoltsev et al.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The Differential Pressure Signal De-noised by Domain Transform Combined with Wavelet Threshold

- Regular Articles

- Robot-operated quality control station based on the UTT method

- Regular Articles

- Regression Models and Fuzzy Logic Prediction of TBM Penetration Rate

- Regular Articles

- Numerical study of chemically reacting unsteady Casson fluid flow past a stretching surface with cross diffusion and thermal radiation

- Regular Articles

- Experimental comparison between R409A and R437A performance in a heat pump unit

- Regular Articles

- Rapid prediction of damage on a struck ship accounting for side impact scenario models

- Regular Articles

- Implementation of Non-Destructive Evaluation and Process Monitoring in DLP-based Additive Manufacturing

- Regular Articles

- Air purification in industrial plants producing automotive rubber components in terms of energy efficiency

- Regular Articles

- On cyclic yield strength in definition of limits for characterisation of fatigue and creep behaviour

- Regular Articles

- Development of an operation strategy for hydrogen production using solar PV energy based on fluid dynamic aspects

- Regular Articles

- An exponential-related function for decision-making in engineering and management

- Regular Articles

- Usability Prediction & Ranking of SDLC Models Using Fuzzy Hierarchical Usability Model

- Regular Articles

- Exact Soliton and Kink Solutions for New (3+1)-Dimensional Nonlinear Modified Equations of Wave Propagation

- Regular Articles

- Entropy generation analysis and effects of slip conditions on micropolar fluid flow due to a rotating disk

- Regular Articles

- Application of the mode-shape expansion based on model order reduction methods to a composite structure

- Regular Articles

- A Combinatory Index based Optimal Reallocation of Generators in the presence of SVC using Krill Herd Algorithm

- Regular Articles

- Quality assessment of compost prepared with municipal solid waste

- Regular Articles

- Influence of polymer fibers on rheological properties of cement mortars

- Regular Articles

- Degradation of flood embankments – Results of observation of the destruction mechanism and comparison with a numerical model

- Regular Articles

- Mechanical Design of Innovative Electromagnetic Linear Actuators for Marine Applications

- Regular Articles

- Influence of addition of calcium sulfate dihydrate on drying of autoclaved aerated concrete

- Regular Articles

- Analysis of Microstrip Line Fed Patch Antenna for Wireless Communications

- Regular Articles

- PEMFC for aeronautic applications: A review on the durability aspects

- Regular Articles

- Laser marking as environment technology

- Regular Articles

- Influence of grain size distribution on dynamic shear modulus of sands

- Regular Articles

- Field evaluation of reflective insulation in south east Asia

- Regular Articles

- Effects of different production technologies on mechanical and metallurgical properties of precious metal denture alloys

- Regular Articles

- Mathematical description of tooth flank surface of globoidal worm gear with straight axial tooth profile

- Regular Articles

- Earth-based construction material field tests characterization in the Alto Douro Wine Region

- Regular Articles

- Experimental and Mathematical Modeling for Prediction of Tool Wear on the Machining of Aluminium 6061 Alloy by High Speed Steel Tools

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- 10.1515/eng-2017-0001

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- The Methodology of Selecting the Transport Mode for Companies on the Slovak Transport Market

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Determinants of Distribution Logistics in the Construction Industry

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Management of Customer Service in Terms of Logistics Information Systems

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- The Use of Simulation Models in Solving the Problems of Merging two Plants of the Company

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Applying the Heuristic to the Risk Assessment within the Automotive Industry Supply Chain

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Modeling the Supply Process Using the Application of Selected Methods of Operational Analysis

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Possibilities of Using Transport Terminals in South Bohemian Region

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Comparison of the Temperature Conditions in the Transport of Perishable Foodstuff

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- E-commerce and its Impact on Logistics Requirements

- Topical Issue Modern Manufacturing Technologies

- Wear-dependent specific coefficients in a mechanistic model for turning of nickel-based superalloy with ceramic tools

- Topical Issue Modern Manufacturing Technologies

- Effects of cutting parameters on machinability characteristics of Ni-based superalloys: a review

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Task Scheduling in Desktop Grids: Open Problems

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- A Volunteer Computing Project for Solving Geoacoustic Inversion Problems

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Improving “tail” computations in a BOINC-based Desktop Grid

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- LHC@Home: a BOINC-based volunteer computing infrastructure for physics studies at CERN

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Comparison of Decisions Quality of Heuristic Methods with Limited Depth-First Search Techniques in the Graph Shortest Path Problem

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Using Volunteer Computing to Study Some Features of Diagonal Latin Squares

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- A polynomial algorithm for packing unit squares in a hypograph of a piecewise linear function

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Numerical Validation of Chemical Compositional Model for Wettability Alteration Processes

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Innovative intelligent technology of distance learning for visually impaired people

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Implementation and verification of global optimization benchmark problems

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- On a program manifold’s stability of one contour automatic control systems

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Multi-agent grid system Agent-GRID with dynamic load balancing of cluster nodes

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The Differential Pressure Signal De-noised by Domain Transform Combined with Wavelet Threshold

- Regular Articles

- Robot-operated quality control station based on the UTT method

- Regular Articles

- Regression Models and Fuzzy Logic Prediction of TBM Penetration Rate

- Regular Articles

- Numerical study of chemically reacting unsteady Casson fluid flow past a stretching surface with cross diffusion and thermal radiation

- Regular Articles

- Experimental comparison between R409A and R437A performance in a heat pump unit

- Regular Articles

- Rapid prediction of damage on a struck ship accounting for side impact scenario models

- Regular Articles

- Implementation of Non-Destructive Evaluation and Process Monitoring in DLP-based Additive Manufacturing

- Regular Articles

- Air purification in industrial plants producing automotive rubber components in terms of energy efficiency

- Regular Articles

- On cyclic yield strength in definition of limits for characterisation of fatigue and creep behaviour

- Regular Articles

- Development of an operation strategy for hydrogen production using solar PV energy based on fluid dynamic aspects

- Regular Articles

- An exponential-related function for decision-making in engineering and management

- Regular Articles

- Usability Prediction & Ranking of SDLC Models Using Fuzzy Hierarchical Usability Model

- Regular Articles

- Exact Soliton and Kink Solutions for New (3+1)-Dimensional Nonlinear Modified Equations of Wave Propagation

- Regular Articles

- Entropy generation analysis and effects of slip conditions on micropolar fluid flow due to a rotating disk

- Regular Articles

- Application of the mode-shape expansion based on model order reduction methods to a composite structure

- Regular Articles

- A Combinatory Index based Optimal Reallocation of Generators in the presence of SVC using Krill Herd Algorithm

- Regular Articles

- Quality assessment of compost prepared with municipal solid waste

- Regular Articles

- Influence of polymer fibers on rheological properties of cement mortars

- Regular Articles

- Degradation of flood embankments – Results of observation of the destruction mechanism and comparison with a numerical model

- Regular Articles

- Mechanical Design of Innovative Electromagnetic Linear Actuators for Marine Applications

- Regular Articles

- Influence of addition of calcium sulfate dihydrate on drying of autoclaved aerated concrete

- Regular Articles

- Analysis of Microstrip Line Fed Patch Antenna for Wireless Communications

- Regular Articles

- PEMFC for aeronautic applications: A review on the durability aspects

- Regular Articles

- Laser marking as environment technology

- Regular Articles

- Influence of grain size distribution on dynamic shear modulus of sands

- Regular Articles

- Field evaluation of reflective insulation in south east Asia

- Regular Articles

- Effects of different production technologies on mechanical and metallurgical properties of precious metal denture alloys

- Regular Articles

- Mathematical description of tooth flank surface of globoidal worm gear with straight axial tooth profile

- Regular Articles

- Earth-based construction material field tests characterization in the Alto Douro Wine Region

- Regular Articles

- Experimental and Mathematical Modeling for Prediction of Tool Wear on the Machining of Aluminium 6061 Alloy by High Speed Steel Tools

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- 10.1515/eng-2017-0001

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- The Methodology of Selecting the Transport Mode for Companies on the Slovak Transport Market

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Determinants of Distribution Logistics in the Construction Industry

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Management of Customer Service in Terms of Logistics Information Systems

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- The Use of Simulation Models in Solving the Problems of Merging two Plants of the Company

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Applying the Heuristic to the Risk Assessment within the Automotive Industry Supply Chain

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Modeling the Supply Process Using the Application of Selected Methods of Operational Analysis

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Possibilities of Using Transport Terminals in South Bohemian Region

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Comparison of the Temperature Conditions in the Transport of Perishable Foodstuff

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- E-commerce and its Impact on Logistics Requirements

- Topical Issue Modern Manufacturing Technologies

- Wear-dependent specific coefficients in a mechanistic model for turning of nickel-based superalloy with ceramic tools

- Topical Issue Modern Manufacturing Technologies

- Effects of cutting parameters on machinability characteristics of Ni-based superalloys: a review

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Task Scheduling in Desktop Grids: Open Problems

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- A Volunteer Computing Project for Solving Geoacoustic Inversion Problems

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Improving “tail” computations in a BOINC-based Desktop Grid

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- LHC@Home: a BOINC-based volunteer computing infrastructure for physics studies at CERN

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Comparison of Decisions Quality of Heuristic Methods with Limited Depth-First Search Techniques in the Graph Shortest Path Problem

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Using Volunteer Computing to Study Some Features of Diagonal Latin Squares

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- A polynomial algorithm for packing unit squares in a hypograph of a piecewise linear function

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Numerical Validation of Chemical Compositional Model for Wettability Alteration Processes

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Innovative intelligent technology of distance learning for visually impaired people

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Implementation and verification of global optimization benchmark problems

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- On a program manifold’s stability of one contour automatic control systems

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Multi-agent grid system Agent-GRID with dynamic load balancing of cluster nodes