Abstract

Background

Precious metal alloys can be supplied in traditional plate form or innovative drop form with high degree of purity.

Objective

The aim of the present work is to evaluate the influence of precious metal alloy form on metallurgical and mechanical properties of the final dental products with particular reference to metal-ceramic bond strength and casting defects.

Method

A widely used alloy for denture was selected; its nominal composition was close to 55 wt% Pd – 34 wt% Ag – 6 wt% In – 3 wt% Sn. Specimens were produced starting from the alloy in both plate and drop forms. A specific test method was developed to obtain results that could be representative of the real conditions of use. In order to achieve further information about the adhesion behaviour and resistance, the fracture surfaces of the samples were observed using ‘Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)’. Moreover, material defects caused by the moulding process were studied.

Results

The form of the alloy before casting does not significantly influence the shear bond strength between the metal and the ceramic material (p-value=0,976); however, according to SEM images, products from drop form alloy show less solidification defects compared to products obtained with plate form alloy. This was attributed to the absence of polluting additives used in the production of drop form alloy.

Conclusions

This study shows that the use of precious metal denture alloys supplied in drop form does not affect the metal-ceramic bond strength compared to alloys supplied in the traditional plate form. However, compared to the plate form, the drop form is found free of solidification defects, less expensive to produce and characterized by minor environmental impacts.

1 Introduction

Teeth play a critically important role in our lives. Loss of their function affects our ability to eat a balanced diet with negative effects on our systemic health. Loss of their aesthetics can negatively impact social function. However, both function and aesthetics can be restored.

Metal-ceramic restorations have been considered from mid-1950s [1]. Since that time, research and improvements in materials and techniques have dramatically increased the use of them. Nowadays, alternatives to these systems exist, mainly all-ceramic restorations that present advantages in terms of aesthetic properties [2, 3]. However, ceramics are brittle and subjected to premature failure, especially under repeated contact loading in a moist environment [4].

Densely sintered zirconia is significantly more stable as framework material than other ceramics; but, complications may occur such as discolorations, secondary caries and loss of retention [5, 6]. According to Donovan et al. [7], the major problem related to all-ceramics restorations is the greater incidence of veneering porcelain chipping (8–50% at 1–2 years) when compared with porcelain fused to metal restorations (4–10% at 10 years).

As reported by Pjetursson et al. [8], metal-ceramic fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) had lower failure rates than all-ceramic FDPs after a mean observation period of at least 3 years.

Eliasson et al. [9]indicates that FPDs fabricated using high-noble alloys have shown survival rates of 80 to 98%, 81 to 97% and 74 to 85% after 5, 10 and 15 years, respectively. Therefore, the metal–ceramic restoration still is the major and the most reliable type of dental restoration; especially, when a good adhesion between the two materials is achieved.

Even though various theories have been proposed and the variables affecting the metal-ceramic bond strength studied, the real mechanism of bonding is still not clear [10, 11]. As indicated by Anusavic et al. [12] the actual bond strength is difficult to determine with tests because of non-uniform stress distributions.

Even though a standard to evaluate the de-bonding of the ceramics by using a three-point bending text exists [13], shear test is the main alternative adopted in literature.

Both the ceramic fracture and bond strength assessment in bend tests are influenced by the Young’s modulus of the alloy. Therefore, it is not clear which characteristic of the metal-ceramic specimens, whether the bond strength or the modulus of elasticity of the metal, is actually tested [14].

There are two types of flexural tests reported in literature, 3-points [6, 15] and 4-point bending tests [16]; while, in the case of shear test, the geometry of the sample and the testing machine can vary.

Henriques et al. [17, 18] and De Melo et al. [19] used the planar interface shear bond strength test, while Shell et al. [20] and Neto et al. [21] used a modified rectangular parallel shear test.

Many types of metal can be used in metal-ceramic restorations [22]. The alloys used for restoration must meet certain minimum requirements for strength, stability, castability, corrosion/tarnish resistance, burnishability, polishability and biocompatibility. Metal-ceramic systems, compared to full metal restoration, have additional requirements that are necessary to achieve a good adhesion between the alloy and the ceramic. Requirements of these alloys include higher melting temperature, thermal compatibility with ceramics, oxide formation and sag resistance.

Gold is the oldest dental restorative material, having been used for dental repairs by Phoenicians and Romans [23]. Gold alloys, in particular Au-Pt-Pd alloys, are the first ones used for metal-ceramic restorations in the last 30 years [24]. As the cost of gold increased, new noble metals were introduced in dentistry. In particular, Pd alloys such as Pd-Ag and Pd-Cu alloys are the most widely used. In recent years, the use of alternative alloys such as base-metal alloys has increased worldwide. The choice of the based-alloy varies from country to country. In the USA nickel-chromium (Ni-Cr) alloys are frequently used, with or without beryllium (Be), while the alloys most often used in Europe and Japan are the cobalt-chromium (Co-Cr) alloys [21, 25, 26]. Titanium alloys are also an alternative [27, 28]. Their elastic moduli are nearly twice as high as those of the other systems, and their hardness may reach 350 HV [29]. Based metal alloys are often selected when cost is of major consideration, while noble metal casting alloys are generally used to fabricate the metal substructure, because of their advantages in terms of biocompatibility and excellent metal–ceramic bond. Moreover, casting of base metal alloys is more difficult than that of noble alloys because of their high melting temperatures and potentials for oxidation during casting [30]. Finally, due to the high hardness of many base metal alloys, a lot of time is required for the finishing operations in the dental laboratory.

Since the reduction of the production cost for noble-metal alloys is a key factor for the diffusion of these alloys in restoration, new technologies should be developed to achieve this result.

Precious metal alloys can be supplied in traditional plate form (PF) or innovative drop form (DF) with higher degree of purity and lower production cost. This research is aimed to investigate the effect of metal fabrication technique process on the metallurgical and mechanical properties of the alloy with particular attention to the metal-ceramic adhesion.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Alloy preparation

Table 1 summarizes the chemical composition of the alloy used in this work, obtained by optical emission spectrometry, while in Table 2 the most relevant material properties are reported.

Base alloy composition (wt%)

| Pd | Ag | Zn | In | Sn | Ga | Ru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55 | 34 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Relevant material properties 31

| Density (g/cm3) | CTE (10—6 1/K) 25-600°C | Young’s Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|

| 11,1 | 15 | 175 |

Two forms of the same alloy were used to produce samples: plate alloy and drop alloy.

The plates are produced by melting the alloy at 1450° C (in a protective atmosphere) and pouring it into a copper stirrup with dimensions equal to 160x105x6 mm. The alloy is then rolled with four rolling passes in order to decrease its thickness to 1 mm. Before each rolling step the material is annealed at 950° C for 1 hour in argon atmosphere and subsequently quenched. Finally, the alloy is cut into several plates and cleaned with solvents to remove oil and impurities.

The drops are produced by melting the alloy at 1380 °C in a protective atmosphere and by sifting it through spinneret holes of diameter equal to 1,4 mm. Finally, the drops are rinsed with soft water and dried into a spin drier.

2.2 Specimens manufacturing

Both alloy forms were used to produce alloy-ceramic specimens with an opaque interlayer at the metal-ceramic interface. In particular, the alloy was casted adopting the lost-wax casting technique and all the samples were manufactured with the same geometry. Fig. 1 shows the sample geometry.

Geometry of the alloy-ceramic specimen (dimensions in mm)

Alloy specimens were sandblasted with 110 μm alumina grains and then heat treated by increasing the temperature from 650°C up to 950°C with a heat rate of 65°C/min in order to oxidize the surfaces. Finally, a vaporization, which is a cleaning process aimed to eliminate Aluminium remains, was carried out at a pressure of 4,5 bar. An opaque interlayer was then applied manually in the form of a creamy paste mixed with an oily substance and dried in the oven starting from a temperature of 450°C up to 950°C (heat rate of approximately 60°C/min). At the end of the cycle, the specimens were removed from the oven and allowed to cool down. A ceramic coat (Shofu Vintage Halo) was then applied. The ceramic material used in this study was in the form of powder mixed with distilled water.

In order to allow the alignment between the crosshead hole and sample, the layers of opaque and ceramic material were applied at a distance of 5 mm from the upper end of the sample (Fig. 1). Since the opaque and ceramic depositions were applied manually, slight geometric irregularities at the edge between metal substrate and ceramic material were inevitable; thus, a grinding process was carried out in order to assure the repeatability of the test and a uniform contact between the crosshead and the opaque-ceramic material. In Fig. 2, the sample before and after grinding process is shown. Three specimens for each alloy form (PF and DF) were manufactured and mechanically tested.

Edge between metal and ceramic material (a) before and (b) after grinding process

2.3 Shear Bond Strength Test

Shear bond tests were carried out at room temperature by means of a universal testing machine (MTS 858 Mini Bionix) with a load cell capacity of 25 kN and a crosshead speed of 2 mm/min.

Fig. 3 shows a schematic of the testing system, which consists of the metal ceramic sample described in 2.2 (A) and a custom-made C45 steel crosshead (B) used to apply the load. The sample was secured in vertical position at the fixed part of the testing machine. The crosshead hole diameter was 5,80 mm (tolerance range H7, according to UNI EN 20286/1-2 [32]). In order to obtain a good matching between the crosshead and the sample, the latter was grinded to achieve a final diameter equal to 5,75 mm (tolerance range js9). After the alignment, a compressive load was applied on the metal-ceramic interface until fracture occurred.

Schematic of the testing system

Figure 4 shows the sample-crosshead alignment before (Figure 4a) and after testing (Figure 4b).

Shear bond strength test architecture (a) before and (b) after the ceramic detachment

The shear bond strength (SBS) was determined according to Eq. 1:

where, F is the force applied by the crosshead on the metal-ceramic interface, Cad is the ceramic axial development and Sp is the sample perimeter.

Both the SBS trend and its value at failure, which refers to the complete detachment between the ceramic material and the substrate, were assessed.

2.4 Analysis of the metal-ceramic interface and failure mode

The analyses of the fracture surfaces were performed by a Scanning Electron Microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS). SEM micrographs were quantitatively analysed by using the Leica QWin image analyser.

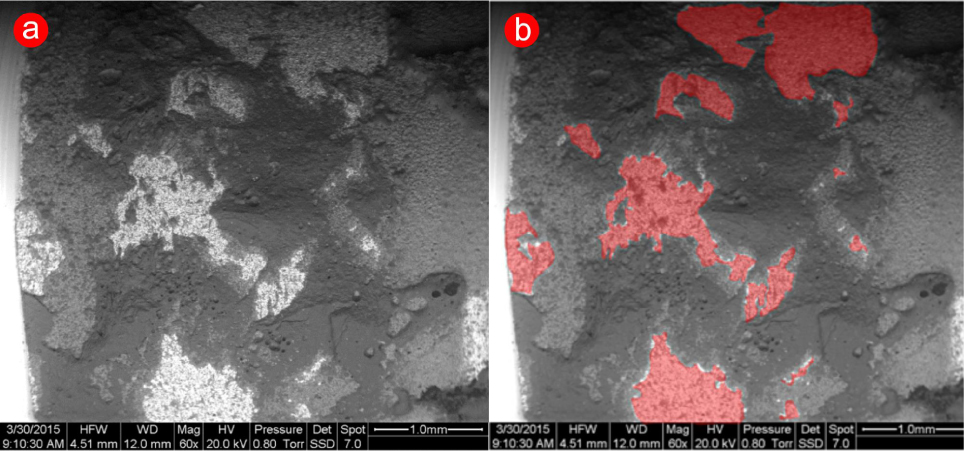

Two modes of failure were observed: (1) fracture occurring at metal-ceramic interface (no remains of opaque or ceramic were found on the metal substrate); (2) fracture occurring within the opaque-ceramic side (remains of ceramic or opaque were found on the metal substrate). Four SEM images were taken from each sample in order to obtain a panoramic view of the fracture surface. The images were then analysed using image analysis in order to quantify the metal-ceramic fracture surface after testing (Fig. 5 shows one of the four images obtained and analysed).

Fracture surface of a sample obtained with the DF precious alloy (a) before and (b) after visible metal area quantification

2.5 Statistical analysis

With the aim to determine whether there were any significant differences between the average values of two or more independent groups, data were analysed using a one-way ANOVA. P-values lower than 0,05 were considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Shear Bond Strength Test

Fig. 6 shows the results of the SBS test done on two specimens obtained from the two different alloy forms analyzed. All tests were interrupted at a crosshead displacement of 2 mm. No interference between crosshead hole and the sample was observed. The increasing of the shear stress with the increasing of the crosshead displacement is due to the attachment of the ceramic residues to the sample after the primary detachment at the first peak of the curve.

Example of shear bond strength results

The mean results, assessed from all the tests carried out on plate and drop form specimens, are reported in Figure 7. The SBS recorded for plate form specimens was 14,36 ± 4,48 MPa (number of tests: 4); while, in the case of drop form, the value was 14,06 ± 3,48 MPa (number of tests: 4).

Mean values of SBS with corresponding standard deviations

3.2 Metal-ceramic interface and failure mode

According to the area percentage of metal visible on the surface of the samples, specimens obtained with drop form alloy were found to present a slightly stronger metal-ceramic bond compared to specimens obtained with plate form alloy. As a matter of fact, the first ones showed less remnants of metal substrate than the second ones (Fig. 8). In particular, the average metal remain areas were 14,22% and 18,18% for drop and plate form, respectively.

Metal remain areas on (a) drop form and (b) plate form specimen

Different EDS analyses were performed on samples of drop and plate form alloy in order to exclude the influence of base metal, ceramic material and oxide layer chemical composition differences on SBS results. An example is shown in Fig. 9.

SEM observations and EDS analyses of the oxide layer: (a) drop form alloy, (b) plate form alloy

Since the SBS results may also be influenced by the oxide and opaque thickness, different optical microscope (OM) micrographs were used to calculate their values (Fig. 10). In Table 3 such values are listed for both the alloy forms. With regard to the opaque layer, the minimum and the maximum thicknesses were assessed; thus, determining a range of variation. Regarding the oxide thickness value, the results listed in Table 3 are the average values of at least thirty measurements.

Metallographic images of the sample interfaces at 200× magnification: (a) drop form alloy, (b) plate form alloy

Results of opaque and oxide layer assessments.

| Opaque layer (μm) Min. thickness | Max. thickness | Oxide layer (μm) Average thickness value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drop form alloy | 16,21±7,9 | 29,4±5,77 | 3,60±1,97 |

| Plate form alloy | 12,34±3,6 | 32,61±8 | 4,59±2,91 |

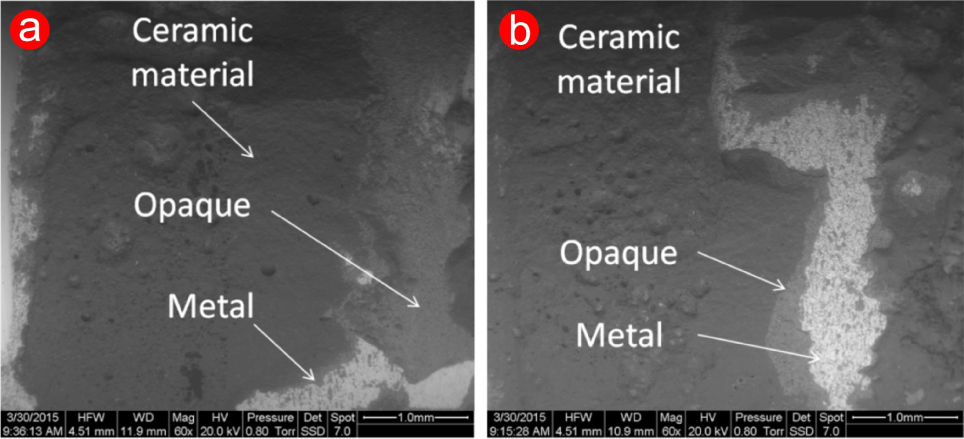

3.3 Bulk precious alloy analysis

In Fig. 11, SEM images of the metal substrate are shown. The sample obtained by plate form alloy (Fig. 11b) shows the presence of gas porosity probably due to contaminants (impurities, oil remains or solvents) used during the production process of the alloy. In contrast, the sample obtained by drop form alloy shows no solidification defects.

SEM images of metal substrate (a) drop form alloy, (b) plate form alloy

3.4 Statistical analysis of SBS data

There were no statistically significant differences between mean SBS values determined by one-way ANOVA (p > 0,05). Results of the two experimental conditions, are summarized in Table 4.

Results of one-way ANOVA for tested conditions according to shear bond strength data.

| Source | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alloy form | 1 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,00 | 0,976 |

| Error | 4 | 64,5 | 16,1 | ||

| Total | 5 | 64,5 |

Statistically significant at a level of p < 0,05. DF: degrees of freedom; SS: Sum of squares; MS: Mean square; F: F-ratio; p: p-value.

4 Discussion

This study evaluates the effect of the alloy form (drop or plate form) used in the production of dental products on the metal-ceramic bond strength. Furthermore, some investigations were carried out in order to assess the metallurgical quality of the casting products obtained, starting from the two analyzed alloy forms.

4.1 Shear test

The standard [13] suggests a three-point-bending-test as testing method; it indicates that the minimum acceptable bond strength to achieve is 25 MPa. On the contrary, Anusavice [33] uses a shear test as testing method and suggests a minimum in vitro bond strength equal to 51 MPa. The SBS values obtained in this study are lower than both the limits suggested in the above-mentioned references. However, due to geometrical differences of the specimens employed in the present work compared to those presented in literature, no direct result comparison can be made.

Comparisons can be made only on results from the same test, as the adopted materials and the sample production technologies have been maintained the same. Moreover, the loading condition has been kept constant. In such conditions, the ANOVA analysis revealed that there is no statistically significant influence of the two alloy forms on the shear bond strength. The mechanical results are consistent with the thickness values of the oxide layers created on the metal surfaces of the samples obtained from both plate and drop form alloy.

It was found that the crack deflects from the joint to the ceramic material due to weakening effect induced by porosities which characterizes the ceramic bulk material (Fig. 5). Significant standard deviation values of the mechanical results may be attributed to slight alteration in the geometric dimensions due to the manual sample preparation and the brittle fracture characteristic which is very sensitive to porosity observed in the ceramic material.

4.2 Metal-ceramic interface and failure mode

Some conclusions about the metal–ceramic adhesion can be drawn by the analysis of the fracture surface. A metal– ceramic system under load will fail at the regions of weakest bonding. The highest bond strength leads to failure within the ceramic; in this case the failure is cohesive. Failures occurring at the interface between metal and oxide layer are adhesive. Depending on the type of fracture, whether it is cohesive or adhesive, the metal–ceramic bonding will be strong or weak, respectively [34]. In this study, according to references [35, 36, 37], the failure types were classified based on the presence of ceramic remnants on the metal substrate after shear tests (i.e. adhesive, cohesive or mixed).

Although adhesion failure is described as a typical failure mechanism of ceramic bonded to noble alloy substrates [38], stereomicroscope observations of the fracture surfaces on the samples analyzed revealed a mixed failure mode. In both cases (plate and drop form alloy), the area of visible metal after the test was lower than 20%; that means a prevalent cohesive failure and thus, a high adhesion strength between metal and ceramic. The difference between plate form and drop form is not significant.

Besides the material chemical compositions, the oxide layer thickness plays an important role in the adhesion between metal and ceramic material. Despite the fact that the average value of the oxide thickness in the samples obtained from plate form alloy is slightly higher than that of the samples obtained from drop form alloy, when making reference to the standard deviation values, it can be concluded that the two kinds of samples have undergone a comparable oxidation process.

4.3 Bulk precious alloy

Despite the same chemical composition, casting products obtained from alloy in plate form showed some solidification defects such as gas porosities. Such defects are linked to the rolling, blanking or continuous annealing used for the production of plates. These processes allow the oily residues, detergents, solvents and oxides to be incorporated and trapped in the micropores present in the metal. The contaminants thus bond indissolubly with the alloy, producing gas porosity in the final casting product. In this case, more expensive and non-conventional castings processes such as vacuum casting process should be used to avoid porosity. On the contrary, specimens obtained with drop form alloy show no solidification defects due to the cleaner drop form alloy production technology. Indeed, the process is contaminant-free, carbon-free and swarf-free. Thus, less or no porosities are generated.

5 Conclusions

Drop and plate alloy are both used in the dental sector but differences between them were not yet analysed in literature. In this paper, a comparison between samples obtained from both plate form and drop form alloy was made in terms of metallurgical and ceramic-alloy adhesion properties. The following conclusions can be drawn:

The shear test results show a good repeatability.

The ANOVA analysis reveals that there is no statistically significant influence of the two alloy forms on the SBS.

Both drop and plate alloy forms show a mixed failure mode, but more than 20% of the surface being covered by ceramic after fracture indicates a good adhesion between metal and ceramic material.

Samples from drop form alloy showed less defects than specimens obtained from plate form alloy. As a matter of fact, the production process for the creation of drop alloy is a direct process that involves instantaneous solidification of the molten metal, via the casting, within specific inert liquids. Drop alloy can thus be considered pure and uniform in composition. Furthermore, granulation significantly reduces production costs and consequently the end price.

Compared to plate alloy, drop alloy helps to reduce the environmental impact because it never come into contact with toxic substances and reduces casting times and production scrap.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Giacomo Mazzacavallo for his support during the experimental tests and Legor Group SpA for the materials supplied

References

[1] S.C. Brecker, “Porcelain baked to gold - a new medium In prosthodontics”, The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 6, pp. 801-810, 195610.1016/0022-3913(56)90077-4Search in Google Scholar

[2] F. Zarone, S. Russo, R. “Sorrentino From porcelain-fused-to-metal to zirconia: Clinical and experimental considerations”, Dental materials, Vol. 27, pp. 83-96, 201110.1016/j.dental.2010.10.024Search in Google Scholar

[3] N.V. Raptis, K.X. Michalakis, H. Hirayama, “Optical Behavior of Current Ceramic Systems” The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry, Vol. 26, pp. 31-41, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[4] B.L. Lawn, Y. Deng, V.P. Thompson, “Use of contact testing in the characterization and design of all-ceramic crown like layer structures: A review”, The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 86, pp. 495-510, 200110.1067/mpr.2001.119581Search in Google Scholar

[5] A.J. Raigrodski, G.K. Meng, M.B. Hillstead, K.-H. Chung, “Survival and complications of zirconia-based fixed dental prostheses: A systematic review”, The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 107, pp. 170-177, 201210.1016/S0022-3913(12)60051-1Search in Google Scholar

[6] M. Guazzato, M. Albakry, S.P. Ringer, M.V. Swain, “Strength, fracture toughness and microstructure of a selection of all-ceramic materials. Part II. Zirconia-based dental ceramics” Dental materials, Vol. 20, pp. 449-456, 200410.1016/j.dental.2003.05.002Search in Google Scholar

[7] T.E. Donovan, jr. EJS, “Porcelain-Fuse-To-Metal (PFM) alternatives”, Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry, Vol. 1, pp. 4-6, 200910.1111/j.1708-8240.2008.00222.xSearch in Google Scholar

[8] B.E. Pjetursson, I. Sailer, N.A. Makarov, M. Zwahlen, D.S. Thoma, “All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part II: Multiple-unit FDPs”, Dental materials, Vol. 31, pp. 624-639, 201510.1016/j.dental.2015.02.013Search in Google Scholar

[9] A. Eliasson, C.-F. Arnelund, A. Johansson, “A clinical evaluation of cobalt-chromium metal-ceramic fixed partial dentures and crowns: A three to seven-year retrospective study”, The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 98, pp. 6-16, 200710.1016/S0022-3913(07)60032-8Search in Google Scholar

[10] W.C. Wagner, K. Asgar, W.C. Bigelow, R.A. Flinn, “Effect of interfacial variables on metal-porcelain bonding”, Journal of biomedical materials research, Vol. 27, pp. 531-537, 199310.1002/jbm.820270414Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] S.J. Marshalla, S.C. Bayne, R. Baier, A.P. Tomsiac, G.W. Marshalla, “A review of adhesion science”, Dental materials, Vol. 26, pp. e11-e6, 201010.1016/j.dental.2009.11.157Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] K.J. Anusavice, P.H. Dehoff, C.W, Fairhurst, “Materials science: comparative evaluation of ceramic-metal bond tests using finite element stress analysis”, Journal of dental research, Vol. 59, pp. 608-613, 198010.1177/00220345800590030901Search in Google Scholar

[13] BSI. Dentistry-Compatibility testing Part 1: Metal-ceramic systems. 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[14] I.A. Hammad, Y.F. Talic, “Design of bond strength tests for metal-ceramic complexes: Review of the literature”, The journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 75, pp. 602-608, 199610.1016/S0022-3913(96)90244-9Search in Google Scholar

[15] T. Korkmaz, V. Asar, “Comparative evaluation of bond strength of various metal-ceramic restorations”, Materials & Design, Vol. 30, pp. 445-451, 200910.1016/j.matdes.2008.06.002Search in Google Scholar

[16] S.E. Elsaka, I.M. Hamouda, Y.A. Elewady, O.B. Abouelatta, M.V. Swaind, “Influence of chromium interlayer on the adhesion of porcelain to machined titanium as determined by the strain energy release rate”, Journal of dentistry, Vol. 38, pp. 648-654, 201010.1016/j.jdent.2010.05.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] B. Henriques, S. Goncalves, D. Soares, F.S. Silva, “Shear bond strength comparison between conventional porcelain fused to metal and new functionally graded dental restorations after thermal-mechanical cycling”, Journal of the mechanical behaviour of biomedical materials, Vol. 13, pp. 194-205, 201210.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.06.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] B. Henriques, D. Soares, F.S. Silva, “Shear bond strength of a hot pressed Au–Pd–Pt alloy–porcelain dental composite”, Journal of the mechanical behaviour of biomedical materials, Vol. 4, pp. 1718-26, 201110.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.05.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] R. Md Melo, A.C. Travassos, M.P. Neisser, “Shear bond strengths of a ceramic system to alternative metal alloys”, The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 93, pp. 64-69, 200510.1016/j.prosdent.2004.10.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] J.S. Shell, J.P. Nielsen, “Study of the Bond between Gold Alloys and Porcelain”, Journal of dental research, Vol. 41, pp. 1424-1437, 196210.1177/00220345620410062101Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] A.J.F. Neto, H. Panzeri, F.D. Neves, R.Ad Prado, G. Mendoca, “Bond Strength of Three Dental Porcelains to Ni-Cr and Co-Cr-Ti Alloys”, Brazialian dental journal, Vol. 17, pp. 24-28, 200610.1590/S0103-64402006000100006Search in Google Scholar

[22] H.W. Roberts, D.W. Berzins, B.K. Moore, D.G. Charlote, “Metal-Ceramic Alloys in Dentistry: A Review”, Journal of prosthodontics, Vol. 18, pp. 188-194, 200910.1111/j.1532-849X.2008.00377.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] H. Knosp, R.J. Holliday, C.W. Corti, “Gold in dentistry: alloys, uses and performance”, Gold bulletin, Vol. 36, pp. 93-102, 200310.1007/BF03215496Search in Google Scholar

[24] R.M. German, “Gold Alloys for Porcelain-Fused-to-Metal Dental Restorations”, Gold bulletin, Vol. 13, pp. 57-62, 198010.1007/BF03215454Search in Google Scholar

[25] J.C. Watada, “Alloys for restoration”, The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 87, pp. 351-363, 200210.1067/mpr.2002.123817Search in Google Scholar

[26] O.L. Bezzon, Md.G.Cd Mattos, R.F. Ribeiro, J.M.D.dA Rollo, “Effect of beryllium on the castability and resistance of ceramometal bonds in nickel-chromium alloys”, The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 80, pp. 570-574, 199810.1016/S0022-3913(98)70034-4Search in Google Scholar

[27] M. Walter, P.D. Reppel, K.B. Ning, W.B. Freesmeyer, “Six-year follow-up of titanium and high-gold porcelain-fused-to-metal fixed partial dentures”, Journal of oral rehability, Vol. 26, pp. 91-96, 199910.1046/j.1365-2842.1999.00373.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] L. Probster, U. Maiwald, H. Weber, “Three-point bending strenght of ceramics fused to cast titanium”, European Journal of Oral Sciences, Vol. 104, pp. 313-319, 199610.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00083.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] J.M. Powers, R.L. Sakaguchi, “Restorative materials -metals”, Craig’s restorative dental materials, 13/e: Elsevier India;. pp. 199-250, 2006Search in Google Scholar

[30] S.F. Rosenstiel, M.F. Land, J. Fujimoto, Contemporary fixed prosthodontics: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Legor. http://products.legor.com/downloadsheet/444/11/IT/-1/-1/none. 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[32] BSI. ISO system of limits and fits — Part 1: Bases of tolerances, deviations and fits and Part 2: Tables of standard tolerance grades and limit deviations for holes and shafts. 1993.Search in Google Scholar

[33] K.J. Anusavice, Phillips’ science of dental materials. Philadelphia: W.B Saunders; 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[34] J.M. Powers, Sakaguchi RL. Craig’s restorative dental materials, 13/e: Elsevier India; 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[35] J.Gd Santos, R.G. Fonseca, L.G. Adabo, C.A.S. Cruz, “Shear bond strength of metal–ceramic repair systems”, the Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 96, pp. 165-173, 200610.1016/j.prosdent.2006.07.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] V.Z.C. Vásqueza, M. Özcan, E.T. Kimpara, “Evaluation of interface characterization and adhesion of glass ceramics to commercially pure titanium and gold alloy after thermal- and mechanical-loading”, Dental materials, Vol. 25, pp. 221-231, 200910.1016/j.dental.2008.07.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] T. Akova, Y. Ucar, A. Tukay, M.C. Balkaya, W.A. Brantley, “Comparison of the bond strength of laser-sintered and cast base metal dental alloys to porcelain”, Dental materials, Vol. 24, pp. 1400-1404, 200810.1016/j.dental.2008.03.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] D.R. Haselton, A.M. Diaz-Arnold, T.James, J. Dunne, “Shearbond strengths of 2 intraoral porcelain repair systems to porcelain or metal substrates”, The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, Vol. 86, pp. 526-531, 2001.10.1067/mpr.2001.119843Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2017 TPaolo Ferro et al.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The Differential Pressure Signal De-noised by Domain Transform Combined with Wavelet Threshold

- Regular Articles

- Robot-operated quality control station based on the UTT method

- Regular Articles

- Regression Models and Fuzzy Logic Prediction of TBM Penetration Rate

- Regular Articles

- Numerical study of chemically reacting unsteady Casson fluid flow past a stretching surface with cross diffusion and thermal radiation

- Regular Articles

- Experimental comparison between R409A and R437A performance in a heat pump unit

- Regular Articles

- Rapid prediction of damage on a struck ship accounting for side impact scenario models

- Regular Articles

- Implementation of Non-Destructive Evaluation and Process Monitoring in DLP-based Additive Manufacturing

- Regular Articles

- Air purification in industrial plants producing automotive rubber components in terms of energy efficiency

- Regular Articles

- On cyclic yield strength in definition of limits for characterisation of fatigue and creep behaviour

- Regular Articles

- Development of an operation strategy for hydrogen production using solar PV energy based on fluid dynamic aspects

- Regular Articles

- An exponential-related function for decision-making in engineering and management

- Regular Articles

- Usability Prediction & Ranking of SDLC Models Using Fuzzy Hierarchical Usability Model

- Regular Articles

- Exact Soliton and Kink Solutions for New (3+1)-Dimensional Nonlinear Modified Equations of Wave Propagation

- Regular Articles

- Entropy generation analysis and effects of slip conditions on micropolar fluid flow due to a rotating disk

- Regular Articles

- Application of the mode-shape expansion based on model order reduction methods to a composite structure

- Regular Articles

- A Combinatory Index based Optimal Reallocation of Generators in the presence of SVC using Krill Herd Algorithm

- Regular Articles

- Quality assessment of compost prepared with municipal solid waste

- Regular Articles

- Influence of polymer fibers on rheological properties of cement mortars

- Regular Articles

- Degradation of flood embankments – Results of observation of the destruction mechanism and comparison with a numerical model

- Regular Articles

- Mechanical Design of Innovative Electromagnetic Linear Actuators for Marine Applications

- Regular Articles

- Influence of addition of calcium sulfate dihydrate on drying of autoclaved aerated concrete

- Regular Articles

- Analysis of Microstrip Line Fed Patch Antenna for Wireless Communications

- Regular Articles

- PEMFC for aeronautic applications: A review on the durability aspects

- Regular Articles

- Laser marking as environment technology

- Regular Articles

- Influence of grain size distribution on dynamic shear modulus of sands

- Regular Articles

- Field evaluation of reflective insulation in south east Asia

- Regular Articles

- Effects of different production technologies on mechanical and metallurgical properties of precious metal denture alloys

- Regular Articles

- Mathematical description of tooth flank surface of globoidal worm gear with straight axial tooth profile

- Regular Articles

- Earth-based construction material field tests characterization in the Alto Douro Wine Region

- Regular Articles

- Experimental and Mathematical Modeling for Prediction of Tool Wear on the Machining of Aluminium 6061 Alloy by High Speed Steel Tools

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- 10.1515/eng-2017-0001

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- The Methodology of Selecting the Transport Mode for Companies on the Slovak Transport Market

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Determinants of Distribution Logistics in the Construction Industry

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Management of Customer Service in Terms of Logistics Information Systems

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- The Use of Simulation Models in Solving the Problems of Merging two Plants of the Company

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Applying the Heuristic to the Risk Assessment within the Automotive Industry Supply Chain

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Modeling the Supply Process Using the Application of Selected Methods of Operational Analysis

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Possibilities of Using Transport Terminals in South Bohemian Region

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Comparison of the Temperature Conditions in the Transport of Perishable Foodstuff

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- E-commerce and its Impact on Logistics Requirements

- Topical Issue Modern Manufacturing Technologies

- Wear-dependent specific coefficients in a mechanistic model for turning of nickel-based superalloy with ceramic tools

- Topical Issue Modern Manufacturing Technologies

- Effects of cutting parameters on machinability characteristics of Ni-based superalloys: a review

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Task Scheduling in Desktop Grids: Open Problems

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- A Volunteer Computing Project for Solving Geoacoustic Inversion Problems

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Improving “tail” computations in a BOINC-based Desktop Grid

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- LHC@Home: a BOINC-based volunteer computing infrastructure for physics studies at CERN

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Comparison of Decisions Quality of Heuristic Methods with Limited Depth-First Search Techniques in the Graph Shortest Path Problem

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Using Volunteer Computing to Study Some Features of Diagonal Latin Squares

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- A polynomial algorithm for packing unit squares in a hypograph of a piecewise linear function

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Numerical Validation of Chemical Compositional Model for Wettability Alteration Processes

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Innovative intelligent technology of distance learning for visually impaired people

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Implementation and verification of global optimization benchmark problems

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- On a program manifold’s stability of one contour automatic control systems

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Multi-agent grid system Agent-GRID with dynamic load balancing of cluster nodes

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The Differential Pressure Signal De-noised by Domain Transform Combined with Wavelet Threshold

- Regular Articles

- Robot-operated quality control station based on the UTT method

- Regular Articles

- Regression Models and Fuzzy Logic Prediction of TBM Penetration Rate

- Regular Articles

- Numerical study of chemically reacting unsteady Casson fluid flow past a stretching surface with cross diffusion and thermal radiation

- Regular Articles

- Experimental comparison between R409A and R437A performance in a heat pump unit

- Regular Articles

- Rapid prediction of damage on a struck ship accounting for side impact scenario models

- Regular Articles

- Implementation of Non-Destructive Evaluation and Process Monitoring in DLP-based Additive Manufacturing

- Regular Articles

- Air purification in industrial plants producing automotive rubber components in terms of energy efficiency

- Regular Articles

- On cyclic yield strength in definition of limits for characterisation of fatigue and creep behaviour

- Regular Articles

- Development of an operation strategy for hydrogen production using solar PV energy based on fluid dynamic aspects

- Regular Articles

- An exponential-related function for decision-making in engineering and management

- Regular Articles

- Usability Prediction & Ranking of SDLC Models Using Fuzzy Hierarchical Usability Model

- Regular Articles

- Exact Soliton and Kink Solutions for New (3+1)-Dimensional Nonlinear Modified Equations of Wave Propagation

- Regular Articles

- Entropy generation analysis and effects of slip conditions on micropolar fluid flow due to a rotating disk

- Regular Articles

- Application of the mode-shape expansion based on model order reduction methods to a composite structure

- Regular Articles

- A Combinatory Index based Optimal Reallocation of Generators in the presence of SVC using Krill Herd Algorithm

- Regular Articles

- Quality assessment of compost prepared with municipal solid waste

- Regular Articles

- Influence of polymer fibers on rheological properties of cement mortars

- Regular Articles

- Degradation of flood embankments – Results of observation of the destruction mechanism and comparison with a numerical model

- Regular Articles

- Mechanical Design of Innovative Electromagnetic Linear Actuators for Marine Applications

- Regular Articles

- Influence of addition of calcium sulfate dihydrate on drying of autoclaved aerated concrete

- Regular Articles

- Analysis of Microstrip Line Fed Patch Antenna for Wireless Communications

- Regular Articles

- PEMFC for aeronautic applications: A review on the durability aspects

- Regular Articles

- Laser marking as environment technology

- Regular Articles

- Influence of grain size distribution on dynamic shear modulus of sands

- Regular Articles

- Field evaluation of reflective insulation in south east Asia

- Regular Articles

- Effects of different production technologies on mechanical and metallurgical properties of precious metal denture alloys

- Regular Articles

- Mathematical description of tooth flank surface of globoidal worm gear with straight axial tooth profile

- Regular Articles

- Earth-based construction material field tests characterization in the Alto Douro Wine Region

- Regular Articles

- Experimental and Mathematical Modeling for Prediction of Tool Wear on the Machining of Aluminium 6061 Alloy by High Speed Steel Tools

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- 10.1515/eng-2017-0001

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- The Methodology of Selecting the Transport Mode for Companies on the Slovak Transport Market

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Determinants of Distribution Logistics in the Construction Industry

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Management of Customer Service in Terms of Logistics Information Systems

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- The Use of Simulation Models in Solving the Problems of Merging two Plants of the Company

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Applying the Heuristic to the Risk Assessment within the Automotive Industry Supply Chain

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Modeling the Supply Process Using the Application of Selected Methods of Operational Analysis

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Possibilities of Using Transport Terminals in South Bohemian Region

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- Comparison of the Temperature Conditions in the Transport of Perishable Foodstuff

- Special Issue on Current Topics, Trends and Applications in Logistics

- E-commerce and its Impact on Logistics Requirements

- Topical Issue Modern Manufacturing Technologies

- Wear-dependent specific coefficients in a mechanistic model for turning of nickel-based superalloy with ceramic tools

- Topical Issue Modern Manufacturing Technologies

- Effects of cutting parameters on machinability characteristics of Ni-based superalloys: a review

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Task Scheduling in Desktop Grids: Open Problems

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- A Volunteer Computing Project for Solving Geoacoustic Inversion Problems

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Improving “tail” computations in a BOINC-based Desktop Grid

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- LHC@Home: a BOINC-based volunteer computing infrastructure for physics studies at CERN

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Comparison of Decisions Quality of Heuristic Methods with Limited Depth-First Search Techniques in the Graph Shortest Path Problem

- Topical Issue Desktop Grids for High Performance Computing

- Using Volunteer Computing to Study Some Features of Diagonal Latin Squares

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- A polynomial algorithm for packing unit squares in a hypograph of a piecewise linear function

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Numerical Validation of Chemical Compositional Model for Wettability Alteration Processes

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Innovative intelligent technology of distance learning for visually impaired people

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Implementation and verification of global optimization benchmark problems

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- On a program manifold’s stability of one contour automatic control systems

- Topical Issue on Mathematical Modelling in Applied Sciences, II

- Multi-agent grid system Agent-GRID with dynamic load balancing of cluster nodes