Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has transformed the educational landscape, making exploration of blended learning (BL) instructional delivery important. Higher education institutions are navigating the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on instructional delivery. Using Accra Learning Centre as a case study, this article explores the experiences of adult learners engaged in BL after the COVID-19 crisis in Ghana. A qualitative research method was employed, and a purposive sampling procedure was used to select 15 adult learners. An in-depth interview guide was developed to garner data. Thematic, narrative, and interpretivist analytical approaches were adopted in presenting the results. Participants’ voices, experiences, and meanings were sought. It emerged that BL promotes inquiry-based, self-directed, and constructivist learning rather than using conventional face-to-face teaching and learning, though conventional teaching and learning cannot be discounted, BL fosters self-paced learning among adult learners. It recommends that faculty continue to sharpen their skills in BL instructional delivery and adult learners should be equipped with skills in time management, and effective digital tools used to engage in BL.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis has transformed every aspect of human life. The pandemic had a global impact not only on health systems but education sector too. The pandemic which necessitated the use of social and physical distancing protocols caused UNESCO (2021) to declare temporary closure of educational institutions globally as part of measures to stop the spread of the virus among people. Educational managers, instructors, and students were prohibited from going to campuses, affecting nearly 94% of learners in 200 countries, and forced Higher education institutions (HEIs) to reconsider the delivery of academic programmes (United Nations, 2021). Many HEIs selected emergency remote education as the pedagogical approach for educators to connect with their students to prevent loss of knowledge (Bustamante, 2020).

Emergency remote education is a form of instruction in which educators adapt the content, the available resources, and the conventional teaching and learning procedures for use online (Bustamante, 2020). Online education quickly established itself as the “new normal,” and it was the workable approach at the time of the pandemic (Bruggeman et al., 2021; Moser et al., 2021). This caused traditional learning environments to change into online learning situations, necessitating the acquisition of digital skills and competencies by instructors and learners. However, as the majority of educational institutions began to relax their regulations, blended learning (BL) gained a lot of traction.

BL has emerged as a key trend in higher education (Alexander et al., 2019); that many predicted would continue even after the COVID-19 pandemic (Yang et al., 2022). Hence, researching adult learners on BL in Ghana after the COVID-19 crisis is important. This study aims to solicit adult learners’ experiences as they engaged in BL after COVID-19, using Accra Learning Centre (ALC) as a case study. The ALC hosts over 85% of the University of Ghana distance education students. This study is important because after COVID-19, one was expecting HEIs in Ghana, including the University of Ghana, to stay on online learning, yet it reverted to BL, indicating the importance of BL to adult learners.

Additionally, few studies have been conducted on BL instructional delivery in HEIs in Ghana after the COVID-19 crisis. As researchers, we have read Murugesan and Chidambaram’s (2020) article on the success of online and BL in HEIs, and Agormedah, Henaku, Ayite, and Ansah (2020) study on students’ responses to online and BL. While Agormedah et al. (2020) examined students’ responses to both online and BL, Murugesan and Chidambaram (2020) focused on strategies to make online and BL a success. Similarly, Biney (2023) examined adult learners’ experiences via the BL approach using the Sakai Learning Management System (LMS) in learning. As far as participants’ learning experiences are concerned, none of the papers extensively sought for their rich voices, diverse, and insightful learning experiences.

Similarly, not many studies in the sub-Saharan Africa region have examined the experiences of adult learners after the COVID-19 crisis adapting the BL approach. This study attempts to fill the gap and investigates varied aspects of BL including reasons for students’ participation in BL, comparison of BL with conventional face-to-face learning, satisfaction level of students, benefits of BL, weaknesses, self-directed learning, and importance of digital learning tools. The purpose of this study is to explore the experiences of Ghanaian adult learners engaged in BL after the COVID-19 crisis at ALC.

Lalima and Dangwal (2017) perceived BL as a cutting-edge strategy that combines the advantages of conventional classroom instruction and ICT-supported learning. Thus, BL uses the three techniques of content, media, and technology in the educational process. Institutions, faculties, and students experience the ‘best of both worlds’ as compared to completely face-to-face classroom or completely online learning (McKenna, Gupta, Kaiser, & Lopex, 2019). Studies conclude that a well-designed BL environment can boost pedagogy, accessibility, cost-effectiveness, flexibility, and satisfaction (BakarNordina & Alias, 2013). BL increased adults’ exam scores and pass rates (Deschacht & Goeman, 2015). BL offers the chance to accommodate different groups of adult learners, particularly those who seek social inclusion and social capital (Vanslambrouck et al., 2019). Due to its flexibility without sacrificing face-to-face interaction, BL is preferred by learners over online or face-to-face learning (Bower, Dalgarno, Kennedy, Lee, & Kenney, 2015; Cundell & Sheepy, 2018; Garcia, Abrego, & Calvillo, 2014; Hall & Villareal, 2015). This is true for adult learners with competing responsibilities since students value faculty participation, feedback, and combination of varied input from both in-person and online interactions (Garcia et al., 2014).

The COVID-19 crisis experience has advanced the use of virtual education and highlighted the significance of designing adaptable learning environments, making universities transition to online and conventional face-to-face modes (Peechapol et al. 2018). Despite a growing body of research exploring the attitudes of instructors and learners in the implementation of BL, there are relatively few studies in the context of adult learners beyond the COVID-19 pandemic in the Sub-Saharan African region. This situation informed the researchers to explore the experiences of adult learners at ALC pursuing degree programmes transitioning to BL after the COVID-19 crisis.

2 Research Questions

What experiences have you garnered in BL after the COVID-19 crisis?

Tell me the reason(s) that led you to participate in BL?

What are your views on blended and conventional face-to-face learning?

What satisfaction do you derive from BL as an adult learner?

What are the strengths/benefits and weaknesses/challenges of BL?

Can you tell me how BL environment fosters self-directed learning?

What digital learning tools do you need to remain active in BL?

3 Theoretical Framework

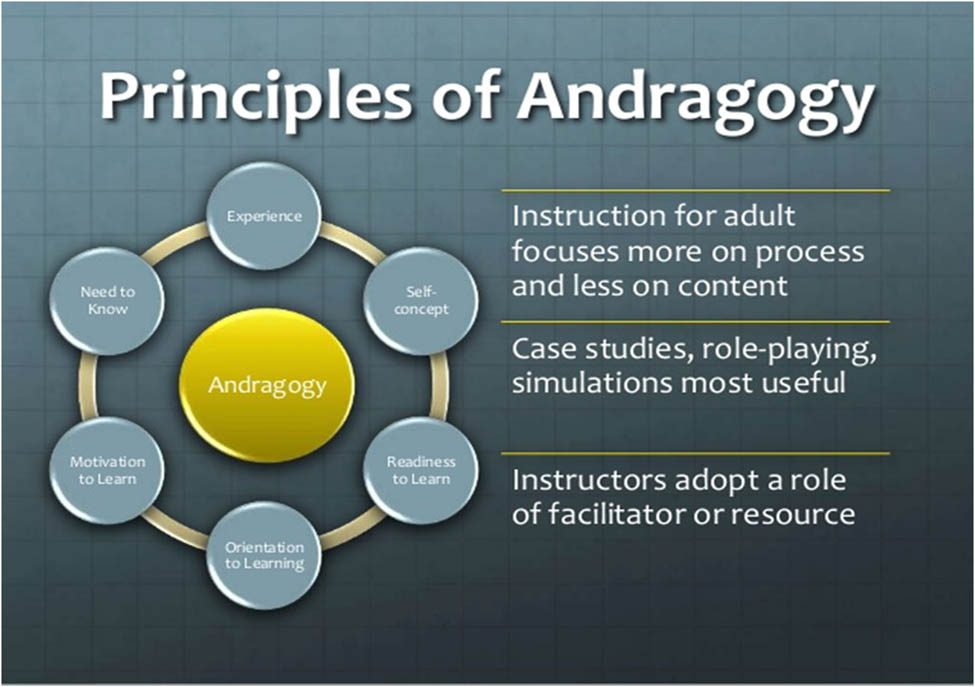

The study is framed by the theory of andragogy developed by Knowles (1980; pp. 43–44) and defined andragogy as “the art and science of teaching adults.” This andragogical theory gave distinct characteristics of adult learners and provided a perspective of adult learners in BL. Bouchrika (2024) opines that andragogy is an approach to learning that is focused on adult learners. King (2017) avers that andragogical principles provide an entry point for reframing our thinking about learning in adulthood and in many contexts. Andragogy provides a foundation for understanding lifelong learning which emphasises the endless scope of our ability to learn as adults (King, 2017).

Andragogy first coined by a German educator, Alexander Kapp in 1833, has since been used to describe a variety of educational philosophies and methods (Loeng, 2018). Knowles andragogy’s central tenet is the art and science of helping adults to learn; yet the foundation for the theory of andragogy is adult learners’ self-directedness (Reischmann, 2004). Andragogical approaches tend to be highly participatory with a strong focus on hands-on learning experiences (Bouchrika, 2020). Thus, adult learners want to be in charge of their learning, and this idea fits in well with BL. In BL, students have the freedom of choice and conviction that they are in charge of their education. Students have the power to decide how they want to attend lectures each week, which enables them to learn on their terms, time, space, and location.

Knowles’ theory of andragogy states that the role of the instructor in andragogy is to assist learning rather than to serve as the subject matter expert. BL relates well to this idea since it allows educators to assist learning rather than lecture because students can take in course material in a variety of ways. Knowles (1984) identified four key principles of adult learning: (1) Adults ought to participate in the planning of their education since students can design their learning strategies because of the BL structure; (2) adult learners ought to experience a sense of personal control over their education; (3) a foundation for learning is provided by adult experience; and (4) adults are most engaged by content that is relevant to their lives. Problem-solving is prioritised in adult education over the material; hence, Knowles classified adult education as a science. Some critics of andragogy, including Reischmann (2004), argue that Knowles presents general principles of education, but like other educational theories, it is one concept borne within a specific historic context. Van Gent (1996) contends that Knowles does not offer a general method, but a very narrow one. Andragogy is less of a cohesive adult learning theory and more of a philosophical approach (Hartree, 1984). Knowles (1989) examined the criticisms and argued that andragogy is more of a conceptual framework for an emerging theory than it is a standalone theory: yet relates to this study.

Knowles (1980). Principles of Andragogy

Similarly, SDL is an underlying principle of andragogy; after all, the first assumption of andragogy is that as a person matures they become more independent and self-directing (Knowles, Holton, Swanson, & Robinson, 2020). This, as observed by Merriam (2017), speaks to the self-directedness of adult learners. An important dimension of SDL is building personal autonomy (Biney, 2021; Knowles et al., 2020). The SDL paradigm was developed as a result of Tough’s (1971) research that the majority of people intend to devote at least 100 h per year to self-planned initiatives. An essential component of adult learning is organising and controlling one’s learning. The adult learner is the focus of Knowles andragogy theory (1968). BL gives adult learners flexibility and convenience and supports and values their autonomy. The adult learning population is catered for by this learner-centred educational approach. BL makes it possible to engage adult learners and gives them the freedom to learn at their own pace by giving them the choice of asynchronous and synchronous learning. However, BL depends on adult learners taking charge and selecting their method of learning: a crucial component of andragogy.

Andragogy has an impact on the ideas of adult learners’ choice, control, learning, and understanding of why they select a certain form of instruction. In BL, adult learners have the freedom to choose how they want to learn rather than receiving the instructor’s full focus in the classroom. In andragogy, the facilitator’s role is that of a resource, and BL fosters this role effectively. BL incorporates the ideas of self-choice, giving adult learners the power to choose their learning and create a learning environment that is relevant to their needs.

4 Related Literature Review

4.1 Instructional Delivery Before the COVID-19 Pandemic

Instructional delivery in HEIs in developing countries was largely face-to-face before the COVID-19 crisis (Biney, 2022). Conventional face-to-face instruction has advantages since it allows for in-person, real-time interaction between educators and learners, and between learners themselves. This engagement can lead to creative analyses and discussions and learners have the chance to ask questions and receive prompt answers (Paul & Jefferson, 2019).

A growing body of research demonstrates that face-to-face instruction motivates students, fosters a feeling of community, and gives them the much-needed reinforcement they require. It enables instructors to recognise non-verbal signs and modify the curriculum and teaching style as necessary (Paul & Jefferson, 2019). While there are several advantages to taking lessons in person, it is an indisputable fact that universities and other HEIs adapted to online learning to continue offering courses during the COVID-19 -crisis. Many academic institutions now use BL; a kind of instruction which combines online learning with face-to-face interactions on campus.

4.2 Online Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Universities and academic institutions all across the world embraced online and alternative learning methodologies as soon as the World Health Organisation (WHO) categorised COVID-19 as a pandemic to lessen the crisis’s impact on education. Universities and institutions were forced to switch to an online medium of education to limit infection (Gewin, 2020). It was difficult for many educators who had never taught online classes to quickly adjust to the new standard and move their curriculum online (Biney, 2023). In a very short period, they had to locate, pick up, and begin using a new, vast set of talents.

Courses that solely required classroom in-person teaching were either cancelled or alternate ways to fulfil the criteria were discovered (Rad, Otaki, Baqain, Zary, & Al-Halabi, 2021). In programmes that needed experiential education to prepare students for employment in professional settings, the effects of course cancellation were magnified (Rad et al., 2021). It is crucial to understand that developing expertise to teach online cannot be done in a few days. For students to have an engaging learning experience there must be careful planning, awareness of pedagogical techniques and theoretical underpinnings, and adoption of course and instructional design concepts (Ellaway & Masters, 2008). Institutions were unable to methodically plan for this transition so they could adjust to the new set of teaching and learning activities because of the emergency situation.

Faculty and students who were used to face-to-face instruction had to quickly adjust to online instruction (Biney, 2023). It is also significant to remember that the majority of these changes occurred at a time when educators and students were concerned for their safety, well-being, and that of their loved ones. Since classes were now being provided online, this led to an increase in psychosocial stress, which was further exacerbated by the lack of human connection (Rad et al., 2021; Saddik et al., 2020). Online learning may not be enjoyable for students who value in-person instruction, in-person interactions, and organic relationships between educators and students (Rovai & Jordan, 2004). They will find it challenging to forego in-person learning experiences in favour of working on a computer.

4.3 Adult Learners’ Experiences of Online Learning During and After COVID-19 Crisis

The role of educators has changed from being distributors of learning resources to being catalysts for students as a result of integrating online learning into education (Hoq, 2020). Hoq research sought to examine the idea of e-learning and debate its significance and use in the field of education, with a focus on how e-learning might help with the disruptions in the field of education brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. The results were that the majority of instructors in Saudi Arabia had a positive attitude toward e-learning, particularly when used as a complement to conventional face-to-face learning.

Basilaia and Kvavadze (2020) also looked into Georgia’s ability to carry on the educational process at schools through online distance learning using online portals, TV Schools, Microsoft Teams for public schools, and alternate options like Zoom. Researchers found that the quick switch to online education was successful and that it might be used as an alternate method of teaching and learning in the future using a case study where the Google Meet platform was employed in a private school with 950 students.

To guarantee that education continues despite the crisis, Ghana, like many other pandemic-affected nations, turned to online distance learning initiatives. Aboagye, Yawson, and Appiah (2020), and Biney (2022) studied the difficulties that tertiary students in online learning during the coronavirus pandemic. Their research revealed that the biggest challenge for students taking online courses was accessibility issues, and contends that it would be preferable to use a BL approach so that students could complete their coursework despite the pandemic.

Henaku (2020) also studied the experiences of some graduate students in Ghana and discovered that they had problems with internet access, financial constraints because internet bundles are expensive, device problems, and disruptions as they have to participate in domestic responsibilities. He concluded that students preferred a blended approach that combined traditional face-to-face instruction with online learning. Owusu-Fordjour, Koomson, and Hanson (2020) add that some students find it difficult to study effectively at home, which makes the online learning system ineffective. Most Ghanaian students had limited access to the internet and lacked the technical expertise of these digital tools during the COVID-19 pandemic, which made efficient online learning challenging. Edem Adzovie and Jibril (2022) conducted a study to evaluate the future success of e-learning in institutions of higher learning and to examine the mediating role of academic innovativeness and technological growth in the successful implementation of this new way of learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their findings showed that the rise in the coronavirus pandemic contributed to academic innovativeness in HEIs in Ghana. However, there is still a need for the management of universities in Ghana and educational policymakers to develop more innovative ways of instructional delivery after the pandemic.

4.4 BL

BL is an approach where educators leverage technology and digital access for learners to create, communicate, collaborate, and apply critical thinking skills to construct knowledge in a connected world (Alpha-Plus, n.d.). It refers to the appropriate and effective use of technology to improve teaching and learning processes and a framework for a course’s instructional design (Allan, Campbell, & Crough, 2019). BL is a paradigm that incorporates many delivery methods that are intended to work in concert with one another and encourage learning and application-learned behaviour (Bruggeman et al., 2021).

Going by these definitions, it is argued that BL uses three techniques content, media, and technology in the educational process. It requires the educator and student to be present online, with some aspects of face-to-face training. A BL programme aims to holistically, deliberately, and successfully integrate technologies, techniques, and pedagogical activities, taking into account constituent features such as online interactive collaboration, student control elements, and linking modalities across the learning pathway (Holley & Oliver, 2010). As a result, BL cannot be viewed as a fixed model. Its layout will change depending on the demands of the students, the subject’s didactics, and the institution’s orientation. Emerging learning technologies facilitate online instruction through synchronous or asynchronous connections, but for students to excel in such a setting, they must feel at ease utilising the technology (Holley & Oliver, 2010).

Technical support is crucial in BL because not all students are familiar with various learning technologies (Johnson, 2017). More technologically savvy students are shown to be more engaged and satisfied with their learning in classroom activities (Min, 2010).

Min (2010): BL combines the “best of both worlds”

4.5 Benefits of BL

The advantages of BL, according to Lalima and Dangwal (2017), include (i) ample time for collaboration between teachers and students in the classroom; (ii) the incorporation of web-based learning into traditional teaching methods; (iii) increased communication opportunities; (iv) increased technological fluency; (v) the development of various professional traits in the students; and (vi) updating and enhancing the course material.

McCown (2014) states that students learn to work cooperatively in group projects through a BL approach. According to Koban-Koç and Koç (2016), students can graduate to higher stages of information and abilities and learn how to think logically by using a BL strategy. BL promotes higher-order abilities and active learning (Varthis, 2016). Numerous research findings indicated that BL increases students’ self-direction, accountability, and productivity in the classroom (Krishnan, 2016). Additionally, BL increases students’ intellectual potential (Rivera, 2017). Graham and colleagues recognised three main advantages of BL: improving pedagogy, expanding accessibility and flexibility, and increasing cost-efficiency (Graham, Allen, & Ure, 2005). A study from the University of Central Florida revealed that BL had higher success rates than both fully conventional face-to-face and online courses (Graham, 2013). Similarly, several studies claim that BL enhanced learners’ capacity for knowledge-building and problem-solving (Bridges, Green, Botelho, & Tsang, 2015).

King and Arnold (2012) assert that BL may promote educational access by allowing for flexibility in learning settings and times. BL may increase education’s cost-effectiveness to lower operating expenses than conventional on-campus learning (Graham, 2013; Vaughan, 2007; Woltering, Herrler, Spitzer, & Spreckelsen, 2009). It is important to keep in mind that online work should be just as stimulating as work done in person in a classroom while creating a course using the BL medium. Asynchronous work gives pupils the chance to learn autonomously. Face-to-face situations, on the other hand, foster conversation, contemplation, and the growth of critical thinking, teamwork, and encourage a proactive approach to learning (Allan et al., 2019). Finally, BL fosters growth and innovation in virtual and online classrooms by integrating technological resources into the learning and teaching process.

4.6 Weaknesses of BL

Studies have discovered several drawbacks of BL, including lack of technological proficiency, network issues, and time wastage (Aldosemani, Shepherd, & Bolliger, 2019). Of course, BL is not a magic bullet for all learning requirements; hence, Bower et al. (2015) aver that BL makes students’ cognitive loads heavier in content and technological demands. It is important to examine the students’ capacity for success under this workload. Similarly, a LMS must be put in place by the University for BL to take place; and this entails spending money on purchasing the software and hiring staff to provide on-going technical assistance for instructors and learners.

HEIs must spend time and money educating faculty and students on how to use the platform (Ashrafi, Zareravasan, Rabiee Savoji, & Amani, 2020; Dhawan, 2020). An adjustment period for students and teachers to embrace this method must be taken into account when BL is implemented. Students must be taught and learn time management skills (Biney, 2022). Educators must develop technological and active learning practices, because people may want to see students and teachers effective at using cutting-edge educational tools (Ożadowicz, 2020; Rasheed, Kamsin, & Abdullah, 2020).

4.7 Experiences of Adult Learners Engaged in BL

Adult learners can experience the “best of both worlds” in BL. The benefits of both modalities, including direct contact, in-person interaction, time for deliberate reflection on discussion responses, and the ability to share resources that reflect key adult learning principles can be used (Merriam & Bierema, 2014). For this reason, BL has been established as the ideal structure for adults. Deschacht and Goeman (2015) discovered that BL increased adults’ examination scores and course pass rates. Similarly, BL offers the chance to accommodate different groups of adult learners, particularly those with varying levels of self-regulation or who seek various degrees of social inclusion and social capital (Vanslambrouck et al., 2019).

Different learning preferences can be accommodated by BL and a wide range of activities are available when employing both modalities (Garcia et al., 2014). Due to its flexibility without sacrificing face-to-face interaction, BL is preferred by students over solely online or face-to-face learning (Bower et al., 2015; Cundell & Sheepy, 2018; Hall & Villareal, 2015). This is true for adult learners who have many competing responsibilities. According to Garcia et al. (2014), students valued faculty participation, feedback, and the combination of various forms of input from both in-person and online interactions. In a poll on students’ satisfaction, 95% of respondents said they would pick a BL model above either a face-to-face or online model (Garcia et al., 2014).

Bower et al. (2015) assert that students learned more in a BL class than in a traditional classroom setting, although both environments had the same sense of community. BL can be more effective than face-to-face instruction when BL course incorporates interactive learning (Castaño-Muñoz, Duart, & Sancho-Vinuesa, 2014). While it may be uncertain which modality produces the best learning outcomes, it is logical to presume that all modalities, when planned and guided effectively, can positively impact students. BL is compatible with established adult learning theories like andragogy (Youde, 2018). Self-directed learning, readiness to learn, and intrinsic motivations are emphasised by andragogy in BL (Merriam & Bierema, 2014; Youde, 2018). Adult learners need the flexibility that BL can offer since they want autonomy in what and how they learn. When creating courses for this group, which is primarily made up of distance learners, instructors must comprehend and put these adult learning principles into practice.

5 Methods

This study conducted at ALC used a case study design. The intention of the researchers is to garner voices and experiences of adult learners as they transitioned to BL instructional delivery from online learning after the COVID-19 crisis. Hence, the study examined seven issues as captured in the research questions and provided information on the methods employed to conduct the study. It commences with the population of the study, research design, sample, and sampling techniques followed. Data collection techniques and data analysis, and the study’s credibility and dependability were established.

5.1 The Population of the Study

The study adopted a qualitative case study design. Adult learners learning via the DE mode, fifteen (15) out of 120 accessible populations, formed the design’s unit of analysis. The target population is adult learners offering DE degree courses at the ALC, using BL instructional delivery approach. This information was obtained from the registered students list at ALC.

5.2 Research Design

The study used a case study research design. The researchers’ intention was to ascertain from adult learners experiences gained by engaging in BL after COVID-19 crisis. Information were solicited via participants’ own ‘voices’ in Ghana. The study adapted an interpretivist research philosophy and a qualitative approach to ascertain evidence to confirm the theoretical claims. Qualitative data was collected through in-depth interviews with participants. The study employed a case study design from a thematic, narrative, and interpretative research dimension (Creswell and Poth (2018). A case study by Merriam and Grenier (2019) focuses on an in-depth analysis of a single phenomenon in order to create a comprehensive description of that precise event.

5.3 Sample and Sampling Techniques

The sample size was based on the total population of DE students at ALC. The participants were many for all to participate in the study; hence, randomisation was implemented, to purposively choose 15 participants to partake in the study. The participants’ experiences, benefits of BL, difficulties, and nuances among others gave the researchers the chance to understand the essence of BL to adult learners learning via DE mode at ALC. Purposive procedures were sought in selecting the sample for the study. The study was conducted at ALC, a University-Based Adult Education institution, which aids adult learners to learn and become useful in today’s digital workplaces.

5.4 Data Collection Techniques

We brought the sampled population together at ALC and explained the purpose of the study to them, and all the 15 sampled participants indicated their interest in participating in the study. An in-depth interview guide was developed and utilised to elicit opinions from adult learners using open-ended questions. In-depth interviews allowed the researchers to speak with participants directly and comprehensively. This approach of generating responses from the participants enabled a detailed exploration of their experiences.

Before the interview, the participants’ consent was obtained and their anonymity was guaranteed. We got to a point of saturation once the trend and pattern of information-rich data gathered to address the issues presented seemed similar. This is significant because, according to Saunders et al. (2017), qualitative research uses saturation as a criterion for stopping data collection and/or analysis.

The interviews lasted between 40 and 50 min. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews conducted were conversational in nature. We carefully listened to the participants and noted their non-verbal cues. We monitored the progress of conversations, participated, and encouraged participants to elaborate on their responses. The conversational nature of the interviews allowed us to summarise what transpired during the interview. We took the opportunity to ask the participants if the notes we took reflected their position. We regularly reviewed the responses from the in-depth interview guides, field notes, and diaries for accuracy and comprehensiveness, as specified by Creswell and Poth (2018). Data was thoroughly edited for consistency and analysed thoroughly via a number of procedures. In order to triangulate the responses obtained from the in-depth interview guides, the challenges and insightful suggestions collected were used as anecdotal evidence. The open-ended nature of the questions allowed us to explain the patterns and themes that emerged from the study. This process enabled us and the participants to co-create and co-construct the narrative.

5.5 Data Analysis

The researchers followed the processes of qualitative researchers like Merriam and Grenier (2019) to analyse the qualitative data acquired. Taped interviews were transcribed verbatim. The valid qualitative in-depth interviews were analysed using a computer programme called ATLAS/ti. Since in qualitative research the analysis starts as soon as the researcher starts collecting the data, we built the structure right from the commencement of data collection, fine-tuning the questions, revising, and editing fieldnotes and diaries. The procedures used in conducting the thematic analysis included familiarisation of the data, generation of initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and report writing (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, 2017). We used a data analysis grid to develop the data coding emerging themes.

The raw data was meticulously examined in the first step to spot any early themes. After discovering broad patterns in the first stage, the second step required creating a thematic framework composed of themes and sub-themes via the use of a data analysis grid. Seven themes that emerged were presented in the introduction of the results section. The themes that had been discovered were then indexed, allowing for the proper categorisation of thematic charts to synthesise the data by giving the same numbers to themes that had comparable interpretations.

For a more complete understanding of the participants’ experiences, we further refined the data into broad categories and topics. The information collected was given interpretations and meanings. In this study, “voice” was used, and this was followed by an interpretivist analysis of the themes, where elements were correctly refined by looking at each column of the thematic chart across all instances to discover the content and dimensions of each case. This made sure that the categories that were found could be refined more effectively. The following stage involved looking for patterns and connections between groups of phenomena as well as between the various viewpoints expressed by the participants. Associative analysis was required at this point. The final phase discussed the findings in the context of the literature. We examined the data in detail before coming up with the final themes and sub-themes. All quotations are given verbatim to accurately portray the participants’ voices. Thematic, narrative, and interpretivist analytical approaches were adopted in presenting the results. Participants’ voices, experiences, and meanings were sought.

5.6 Credibility and Dependability of Results

The trustworthiness of the result is the extent to which a study can be replicated in another context in qualitative research (Merriam & Grenier, 2019). The participants were engaged to ensure the study’s credibility. Enough contextual information about the fieldwork site and participants was provided in the study to ensure transferability. As Armstrong, Marteau, Weinman, and Marteau (1997) observed, assessing inter-rater reliability in qualitative research though complex is an important method for ensuring rigour. As qualitative researchers, we recruited, trained, and involved a research assistant in data collection and analysis to engender researchers’ triangulation and seek inter-rater agreement. The research assistant’s support largely aided in the reduction of bias involved in the analysis, and also enhanced consistency and reliability of the results. This is because, in the finalisation of the analysis of the data, we realised that the research assistant assigned the same rating to each object. That is to say, the qualitative data provides precision and unique insight. Unique codes and themes were built into the data collected. On dependability and conformity of this study, the research methods were explained, and the research questions for the research were explained and discussed with the participants of the study.

5.7 Ethical Consideration

Before we embarked on this study, clearance was sought from the University of Ghana authorities. The participants were informed in writing concerning the study’s objectives, the time and meeting place, and their expectations during the interview. The participants were assured of strict confidentiality of the information and their right to opt out of the interview without any repercussions since their participation was purely voluntary. Participants were also made aware that the interviews would be tape-recorded, and the data would be kept for a period of six months after the study and destroyed afterward.

6 Results

Seven themes emerged from the data analyses undertaken, and they include ‘adult learners experiences in BL’; ‘reasons for participating in BL’; ‘BL and face-to-face learning’; ‘satisfaction from BL as an adult learner’; ‘benefits and weaknesses of BL’; ‘BL environment and SDL’; and finally, ‘digital learning tools and BL’.

7 Experiences of adult learners in BL

On adult learners’ experiences in BL, the participants responded in the affirmative yes. They indicated that they have gained some experience in BL, since BL calls for hands-on practice, and as they continuously engage in hands-on activities on the Sakai LMS to learn, they have acquired some digital skills via usage of the Sakai LMS tools and devices in learning. Some of the participants presented their experiences in these apt ways:

“I have learnt to adapt to changing quickly as switching from traditional face-to-face, blended learning, online learning and back to blended learning was sudden and quick. I experienced engaging facilitation and learning, doing assignments offline and online simultaneously. I also experienced most people choosing to do a lot of academic activities online when they were given the liberty to decide.” (Participant # 2)

“Blended learning after COVID-19 has made teaching and learning easier, especially for me pursuing my degree programme via the distance education mode. There is so much access to information making it much easier to go over lessons. I have learnt to maneuver through online study methods. I’m now more conversant studying online.” (Participant # 1)

“Since my institution commenced blended learning, I have enhanced my skills in virtual communication through the use of virtual platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams in our teaching and learning. I have also observed an improvement in my communication and participation skills on learning platforms at ALC through, including virtual media”. (Participant # 5)

Considering the experiences of participants’ it can be stated that participants’ experiences resonate with Bower et al. (2015); Cundell and Sheepy (2018); Graham et al. (2005); and Hall and Villareal (2015) observation that BL is flexible, and as a result of its flexibility without sacrificing face-to-face interaction, it is preferred by students over online or face-to-face learning. Similarly, a study from the University of Central Florida revealed that BL had higher success rates than conventional face-to-face and online courses (Graham, 2013). This demonstrates the importance of BL as the ‘best of the two worlds’ of instructional delivery (Graham, 2013). This result may not be surprising to today’s social-media-savvy learners who prefer a constructivist approach to learning and learning by ‘doing and sharing’ (Biney, 2022; Parkay, 2013).

8 Reasons for Participating in BL

On reasons that led participants to adapt and participate in BL, the participants revealed that their institution policies informed adapting BL after the COVID-19 crisis. The strategic plan of the University of Ghana in 20214–2024 is to become a research-intensive university, and therefore, had in place facilities that promote instructional delivery via the BL approach. This, therefore, engendered a smooth transition to the BL approach. This is an apt way a participant expressed it;

“I think the policy of my University compelled me to adapt and participate in blended learning instructional delivery and learning. This is because the crisis created by COVID-19 has subsided and I believed that the blended learning can serve us better than solely online teaching and learning which my University resorted to at the peak of COVID-19. The point is that I was already pursuing my degree programme via the blended teaching and learning approach so when my University reverted to blended learning from solely online learning, I felt at home and grabbed the opportunity at once.” (Participant # 7)

These reasons advanced by the (participant # 7) were complemented by some other participants’ observations. They indicated that they were already engaged in BL approach before the COVID-19 crisis so going back to learn via the BL instructional delivery approach was a matter of course. This is because it enables adult learners to have enough time to complete their syllabus. “Whenever we met for the face-to-face interaction, we didn’t have enough time to complete the topics.” Another participant expressed it in this succinct way:

“Distance learning is noted to employ both face-to-face and virtual teaching and learning approaches to make adult learners digitally skilled. So, to me, it is not surprising that after COVID-19, my University has resorted to blended learning approach once more, which I think is appropriate considering the norm of distance learning. Also, I think that blended learning is crucial at this digital age to provide access to many non-traditional learners to benefit from the University education.” (Participant # 8)

Responses provided by the participants resonate with Rosen and Stewart (2015) assertion that BL may be more effective for adult learners than only face-to-face learning or only online learning. They added that participants in BL outperform learners in either face-to-face or online teaching or learning. The participants from the study prefer learning via BL approach and the results make a case for flexibility in learning as crucial to adult learners, because adult learners have competing responsibilities to cater for even as they make time to learn. Some of the participants are workers and prefer to work, earn, and learn at the same time (Biney, 2022; The Economist, 2017).

9 Blended and Face-To-Face Learning

Participants responded that Conventional face-to-face learning takes place when instructors and learners meet on-site for teaching and learning to take place while BL takes place when instructors and learners meet both online and onsite. Participants expressed their experiences with both instructional delivery models in the following ways:

“Personally, I consider face-to-face learning as a kind of onsite student-tutor facilitation and learning, and provide me that interactive learning environment. They are significant models for instructional deliveries. However, the face-to-face model is less expensive on average in contrast to blended learning which combines virtual and face-to-face teaching and learning.” (Participant # 5)

“To me, both models of instructional delivery are useful and important; however, the blended learning approach is self-regulated. And as a worker, I prefer it more to that of the traditional face-to-face teaching and learning.” (Participant # 11)

“Blended learning can be very helpful for courses that have little or no practical work. Otherwise, it is less useful to me as an Economic student with some of my courses statistically inclined. However, blended Learning is convenient.” (Participant # 10)

“For me conventional face-to-face learning means I have to be more attentive in class unlike online classes where there are a lot of distractions that usually emanate from colleagues simultaneously receiving calls and learning online as well. As an adult learner, I tend to understand lessons more when they are taught face-to-face instead of online. Though conventional learning has advantages, blended learning promotes learners digital literacy skills and allows for opportunities to learn.” (Participant # 6)

The result ties in well with Ramirez-Mera, Tur, and Marin (2022) observation that online students focus on the use of information management skills and on self-regulation of the learning process whereas face-to-face students are oriented towards the use of communication skills. Deducing from observations and experiences garnered by the participants on Blended and conventional face-to-face learning, both approaches to facilitation and learning have their own strengths and weaknesses. It is however noted that there is no instructional delivery system that is perfect and that management of DE programmes should continuously improve on BL to make it useful to adult learners to address their learning needs.

10 Satisfaction from BL as an Adult Learner

The participants stated that BL is more satisfactory in the sense that it provides a solid option to teaching and learning. This is because adult learners have a lot of responsibilities and some of them are not likely to be present during the face-to-face tutorials and compensate for that with online meetings. Two of the participants expressed themselves in this apt ways:

“With blended learning, I do not always have to be in a lecture hall. I can be wherever and have the opportunity to participate in class. Indeed, blended learning offers me that flexibility that I would not have had from the conventional face-to-face learning approach”. (Participant # 10)

“Blended learning makes learning easy as compared to the conventional face-to-face learning. Indeed, it makes me feel like I am learning on my own. It also brings more insight and understanding. It is exciting trying new learning methods, especially online. It does not meet optimum satisfaction although it seems effective”. (Participants # 15)

As observed by the participants, both approaches to facilitation and learning have their challenges, yet BL approach provides some satisfaction as compared to conventional face-to-face teaching and learning. Graham (2013) perceives BL as the ‘best of the two worlds’ of instructional delivery. Hence, regular training is to be provided to both lecturers and adult learners to sustain BL instructional delivery to drive effective teaching and learning.

11 Benefits and Weaknesses of BL

The participants see BL as beneficial, yet have some weaknesses. Participants mentioned a number of benefits, including the learning community it fosters, interactions, and quick response:

“I think that timeliness of lessons is an advantage in a blended learning environment, especially if you’re going to employ synchronous webinars as part of that blended solution. I must add that conventional learning has advantages, yet blended learning promotes digital literacy skills and allows for more range to learn” (Participant # 3)

Similar experiences were shared by other participants:

“Well, the benefits come from interacting with people, knowing when to act on ideas or thoughts, being able to bounce them off to someone, and receiving feedback within five seconds. It matters a lot more than if you compose out a lengthy paper, send it off, and then wait for feedback in days later.” (Participant # 7)

“The strength of blended learning is the convenience and flexibility and the weaknesses are distractions when academic activity is done online and how people tend to not grasp things well when they are taught online. Not everyone is open to blended learning as people are generally resistant to change and would prefer everything face-to-face. Blended learning makes teaching and learning easier but it also has some weakness like network problems which does not make it accessible to some people.” (Participant #11)

“I see blended learning as beneficial to students whose proximity to campus is quite long as it spares them the stress in commuting every ‘lecture day’ and minimise the expenses involved. Also virtual lecture days provide a restful ambience to workers. “Network challenges make tutorials quite terrible experience for some students. Others with electronic device problems get to miss virtual tutorials which could have been avoided in the fixed conventional face-to-face learning structure”. (Participant # 14)

“Rescheduling of meeting times for virtual lectures by some tutors is disadvantageous to most adult learners who have to readjust personal schedules to meet that of impromptu lecture times. High costs of data and lack of personal computers are some of blended learning challenges I faced in my studies”. (Participant # 6)

As observed by Alpha-Plus (2022), the BL instructional delivery approach is one that enhances and extends the application of adult learning principles to meet the changing needs of people learning, working, and engaging in the twenty-first-century life. That means that HEIs engaged in the DE mode of learning must continuously innovate to make the BL approach more useful to adult learners to enable them maximise their learning endeavours. Network challenges as observed by Biney (2022) continue to serve as a barrier to successful BL and must be addressed. This would aid adult learners to address their learning needs and become successful in their lifelong learning journey.

12 BL environment and self-directed learning

All the participants stated that BL offers them the opportunity to have autonomy in their learning as adults. The following are some of their views:

“Blended learning offers me more time so when I utilise the time well, I am able to control my own learning. Sometimes students have to create their own understanding of what is been taught, and would not necessarily need a teacher in front of you. I mostly resort to self-directed learning, yet network failures and low speed computers usually affect my independent studies.” (Participant #12)

“Learning on my own seems highly beneficial. During face-to-face tutorial times, the large class sizes create the antithetical environment to ideal learning. Resorting to self-directed learning seems the only option. To me, the only challenge I have with blended learning has to do with increased independent studies.” (Participant # 8)

The participants demonstrated that BL encourages self-directed learning, and that is good for adult learners to the extent that when they complete their programmes they would not see themselves as students forever but as learners who pursue learning throughout their entire lifetime. This is so because adults in the digital age engage in learning when they have no instructor or guide (King, 2017). Learning becomes autonomous when adult learners have the independence or freedom to design their own learning is one ingredient in adult learning. Hence, adult learners must be encouraged continuously to foster or make learning a lifelong learning venture or drive.

13 Digital Learning Tools and BL

Participants were unequivocal that they need digital tools to remain active in BL. The following digital tools, including the SAKAI LMSs, smart mobile phones, and personal laptops come up for mentioning. Applications (Apps) like Microsoft Teams and Zoom are learning platforms largely used by adult learners to learn at ALC. However, the participants indicated that the Sakai LMS at ALC requires retooling and refurbishment to aid their lifelong learning endeavours.

Indeed, Sakai, a version of LMS, is a on the word chef and refers to the Iron Hiroyuki Sakai. It has numerous interactive learning tools, including resources, assignments, chat, and forums among many other tools that aid and ease teaching and learning online (Biney, 2020).

14 Discussions

Never in the history of HEIs has the demand for social distance in teaching and learning been as pressing as it was during the COVID-19 crisis. Academic institutions had to adjust to both in-person and online instruction. This study rather used in-depth interviews to explore the experiences of adult learners after the COVID-19 pandemic to determine how, in their opinion, BL enhanced efficient instruction. The study aligns with andragogy, and since adult learners are all not the same, and BL also not a one-size-fits-all instructional delivery method the study is important. When given the opportunity to make decisions about how to use the course materials, students can choose what suits them best in terms of their learning styles. Some students attend tutorials, others due to workplace commitments could benefit from online learning since they cannot attend tutorials regularly. Flexibility and student satisfactions are some of the benefits BL provides to adult learners learning via the DE mode (Garcia et al., 2014). This observation has been emphasised by Bower et al. (2015), Ramirez-Mera et al. (2022). From the study, BL is preferred by students over online or face-to-face learning (Bower et al., 2015; Cundell & Sheepy, 2018; Hall & Villareal, 2015).

On experiences of adult learners in BL after COVID-19, the participants agreed that they have acquired some experiences with their engagement in BL after the COVID-19 crisis. This is expected because BL integrates online and offline learning, hence, adult learners can experience the “best of both worlds.” The participants indicated that BL is compatible with established adult learning theories like andragogy (Merriam & Bierema, 2014; Youde, 2018). This is because BL offers adult learners opportunities for hands-on experiences in their learning endeavours. Adult learners undertake practical opportunities to experience the ICT or digital tools they employ in learning to address their needs.

Participants noted that the theory of andragogy is highlighted in BL since it emphasises self-directed learning (SDL), readiness to learn, and intrinsic motivations as Merriam and Bierema (2014), and Youde (2018) indicated. Adult learners are able to identify their needs, plan, implement, and control their learning endeavours independently even as they learn. This gives meaning to SDL. As workers and learners, adult learners are able to schedule their timetable taking into consideration their jobs and social responsibilities and learn to achieve their academic goals set for themselves. After all, the participants indicated that they need autonomy in their learning and BL offers them that flexibility to decide on how and when to learn as DE learners.

Learning in this context has become ubiquitous, and can be done anywhere the adult learner finds him or herself. Thus, in SDL, adult learners hold the primary role in their learning (King, 2017). They make the needed choices and actions to take as far as their learning endeavours are concerned. These and other opportunities are realised by adult learners from BL instructional delivery as it is operationalised at UG Learning Centres, including the ALC.

In the case of reasons for participating in BL, the participants affirmed that their participation in BL after the COVID-19 crisis was informed by the University policy. As argued in the literature, universities and academic institutions across the world were forced to switch to an online model of education to limit the COVID-19 spread (Gewin, 2020). Even though it was difficult for many educators who had never taught online classes before, as was the case of some lecturers in the universities in Ghana, the faculty members learned and adjusted to the new standard and moved their curriculum online. Participants averred that their institutions have incorporated the online mode of instruction into conventional face-to-face instruction post-COVID-19 crisis, occasioning the BL. Although the transition was sudden, adult learners were already learning via the BL instructional delivery approach, so adult learners managed to adjust to the change and learn via the BL approach.

On blended and conventional learning, participants indicated that after the COVID-19 crisis, many academic institutions started using BL modes of instruction, thus combining online learning with face-to-face interactions on campuses. The participants aligned BL with Allan et al. (2019) definition and stated that BL is appropriate and effective use of instructional delivery that provided them the independence and flexibility in learning even as they engaged in their day-to-day work. The participants affirmed that BL resonates with Garcia et al. (2014) observation that different learning preferences can be accommodated and a wide range of activities are available when employing both modalities of instructional delivery. The participants further detailed that they prefer BL due to its flexibility without sacrificing face-to-face interaction. Indeed, literature indicates that BL is preferred by students over online or face-to-face learning (Bower et al., 2015; Cundell & Sheepy, 2018; Garcia et al., 2014; Hall & Villareal, 2015), and particularly favours adult learners who have competing responsibilities (Rosen & Stewarts, 2015).

On conventional face-to-face teaching and learning, the participants indicated that many HEIs in Ghana taught lessons entirely face-to-face before the COVID-19 pandemic. The participants added that face-to-face teaching and learning take place when instructors and learners meet on-site whilst BL takes place when instructors and learners meet both online and onsite. Participants stated that face-to-face instruction allows for in-person real-time interaction between teachers and students as well as between students themselves. Such interactions lead to creative analyses and discussions on programmes they pursue respectively. This result confirms Paul and Jefferson (2019) assertion that face-to-face classroom instruction offers students the chance to ask questions and receive answers immediately. Participants were concerned about the community feeling and motivation they derive from conventional face-to-face teaching and learning. Participants’ observations resonate with Paul and Jefferson (2019) that conventional face-to-face instruction enables instructors to recognise non-verbal signs and modify the curriculum and teaching style as necessary. While there are several advantages of taking lessons in-person, it is indisputable that universities and other HEIs adapted to online learning to continue offering courses during the COVID-19 crises.

In terms of participants satisfaction derived from BL, the study revealed that participants were satisfied with BL instructional delivery because it leaves one with an option, especially because adult learners have a lot of responsibilities and they are likely not to be present during the face-to-face tutorials and could participate in the online meetings. Participants’ views complement that adult learners felt BL satisfied their overall need for flexibility in learning as captured in this succinct way: “with BL, I do not always have to be in a classroom. I can be anywhere and have a class.”

On strengths/benefits and weaknesses of BL, the study revealed that participants preferred BL. They valued the flexibility of attending tutorials from any location. The participants see BL beneficial but have some weaknesses that need to be addressed. For strengths and benefits, participants described what Lalima and Dangwal (2017) specified, including ample time for collaboration between teachers and students in the classroom, the incorporation of web-based learning into traditional teaching methods, increased communication opportunities, increased technological fluency, the development of various professional traits in the students and updating and enhancing the course material. Indeed, Megahed and Ghoneim (2022) opine that the integration of in-person lectures with technology creates settings that can improve students’ learning potential. Rivera (2017) also observed that BL increases students’ intellectual potential. Not surprisingly, the participants stated that BL improves pedagogy, expanding accessibility and flexibility, and increases cost-efficiency. In BL, adult learners improve upon their sense of community within the classroom, which they value.

The participants demonstrated that, as adult learners, they know when to act on ideas or thoughts. They added that they are able to bounce new ideas off to someone and receive feedback within five seconds. This according to the participants matters a lot to them than composing an extensive paper, sending it, and getting feedback several days later. More so, virtual tutorial days provide a restful ambiance to workers.

On weaknesses of BL, participants indicated the lack of technological proficiency, network issues, and time wastage as drawbacks of BL. Bower et al. (2015) argue that BL makes students’ cognitive loads heavier in terms of content and technological demands. Participants indicated that they have to spend money to buy network data to participate in online instructions and discussions. Some participants regularly mentioned the need to make an effort to attend face-to-face lectures and difficulties with online learning as succinctly stated here “I find it difficult juggling work and education. My schedule does not allow me to make time to attend tutorials at ALC.” BL may increase education’s cost-effectiveness to lower operating expenses than conventional on-campus learning (Graham, 2013; Vaughan, 2007; Woltering et al., 2009).

On BL environment and self-directed learning, the participants stated that BL offers them the opportunity to have autonomy in their learning as adults. Numerous research findings indicated that BL increases students’ self-directed learning, accountability, and productivity in the classroom (Krishnan, 2016). King and Arnold (2012) and King (2017) assert that BL promotes educational access by allowing for flexibility in learning settings and times. Asynchronous work gives adult learners the chance to learn autonomously. Face-to-face teaching and learning, on the other hand, foster conversation, contemplation, and the growth of critical thinking skills offer venues for teamwork and encourage a proactive approach to learning (Allan et al., 2019). BL offers participants more time, and if that time is utilised well, they are able to have control over their own learning. Indeed, self-directed learning, one of the key principles of andragogy, explains that students should have control over their education (Knowles, 1984). Participants in this study indicated that BL fosters self-directed learning. The participants thought that contacts with peers who did not attend tutorials were not meaningful since students could establish their own learning communities via Sakai LMS, YouTube videos, text messages or social media applications. Adult learners utilise these applications and softwares to communicate and collaborate while working through the course materials.

On digital tools used in BL, participants stated that they need digital tools such as retooled and refurbished Sakai LMS and softwares like Microsoft Teams, Zoom, and personal laptops to remain active in BL. Dhull and Sakshi (2017) observed that online learning deals with a group of technologies that are used to offer education across computer networks. This means that the availability of the internet to access emails, chats, new groups and messages, and audio and video-conferencing are important. Under such a situation, adult learners are able to access learning materials not only from the Sakai LMS, but from the YouTube platform as well.

15 Limitations of the Study

The study noted a few limitations. The study employed a case study method with a small sample size of 15 adult learners on the DE mode of learning. The findings are applicable to these particular participants group which restricts the study’s applicability to other disciplines. To generalise findings, a mixed method research using a larger population on the issue deliberated on is conducted. This study was conducted with adult learners on the DE mode of learning at ALC, and some of the participants combined studies with jobs. It would be interesting to conduct similar research with the pre-tertiary students, especially those in senior high schools, to determine whether students would see any potential for BL instructional delivery after the COVID-19 crisis.

16 Conclusions and Recommendations

The article explored the experiences of adult learners on BL after the COVID-19 crisis in Ghana. Findings include participants acquiring some experiences with their engagement in BL after the COVID-19 crisis, and identified needs, planned, implemented, and controlled learning. Participants added that participation in BL after the COVID-19 crisis was informed by the University policy. Participants indicated further that BL is an appropriate and effective instructional delivery that provided independence and flexibility in learning, yet many HEIs in Ghana taught lessons face-to-face before the COVID-19 pandemic. The study revealed that adult learners felt at home learning via the BL instructional delivery approach and endeavoured to combine studies with work as they participated in BL; yet faced challenges including low-speed internet, poor internet connectivity, and high cost of data to learn.

Pandemics, including COVID-19, can foster creativity and unconventional thinking in educational institutions, and given the options to implement high-quality educational strategies, it is imperative to improve the development of education procedures taking into account andragogy’s fundamental principles and the unique benefits of face-to-face and online learning modalities. Hence, the consideration of learners’ requirements is necessary for BL in adult teaching and learning contexts to foster educational, professional, and social competencies. Instructors should concentrate on developing the right digital skills to support BL instructional delivery if BL is to offer adult learners engaging learning experiences.

Using Knowles andragogy to explore the experiences of adult learners’ engagement in BL after the COVID-19 crisis, the findings of the study summarised served as a foundation for this article, and demonstrate that BL has some potential for adult learners in HEIs than the traditional face-to-face classroom. This becomes important when it comes to fostering students’ independent inquiry-based learning, self-directed, and collaborative learning, because adult learners indicated that the aforementioned skills were fostered. The results did not reject traditional face-to-face instruction; however, BL offers tremendous value to those involved in learning endeavours. BL creates an efficient learning environment while removing the geographical and physical constraints of traditional face-to-face instruction.

The rapid virtualisation of academic activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic gives a chance to adapt the BL paradigm to higher education. It is important to keep up the ground-breaking training that HEIs provided to faculty during the COVID-19 crisis to post-pandemic, taking into account the demands of BL. After all, the participants indicated that BL is ‘the best of the two worlds’, and a suitable instructional delivery approach. The Management of ALC should encourage HEIs in developing countries to employ BL instructional delivery in facilitating the learning of adults in the post-pandemic time.

Additionally, moving towards a constructivist approach that emphasises active learning is essential; however, entails the growth of interdisciplinary competencies which is pertinent for HEIs in developing countries. The effective use of virtual environments and technology is now a prerequisite for the acquisition of digital literacy skills and performance at not only the HEIs, but the workplace. It is worthy to note that BL helps in fostering and building such skills; hence implementing a BL model offers a chance to raise the standard of instruction in HEIs.

The study recommends that the process of implementing a BL model should be accompanied by explicit institutional rules that define the technology tools and platforms. It is further recommended that institutions should update their digital infrastructure and make plans to ensure that students have access to appropriate on-campus areas for independent online study and collaborative spaces for in-person meetings.

Finally, for a successful teaching and learning process to take place, it is essential to train faculty in the integration of virtual and face-to-face facilitation skills. It is crucial to establish and maintain learning communities to share best practices, point out problems, and work together to find solutions. To implement a BL model, it is essential to prioritise meeting students’ needs to ensure that all students have access to educational resources and technologies and can engage in learning activities. To succeed in this learning format, students must receive skills in time management, effective digital tool use, and online learning etiquette.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Prof. Isaac Kofi Biney led the study and Janet data for the study.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Aboagye, E., Yawson, J. A., & Appiah, K. N. (2020). COVID-19 and E-learning: The challenges of students in tertiary institutions. Social Education Research, 1, 1–8. doi: 10.37256/ser.122020422.Search in Google Scholar

Agormedah, E. K., Henaku, E. A., Ayite, D. M. K., & Ansah, E. A. (2020). Online learning in higher education during COVID-19: A case of Ghana. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 3(3), 183–210. doi: 10.31681/jetol.726441.Search in Google Scholar

Aldosemani, T., Shepherd, C. E., & Bolliger, D. U. (2019). Perceptions of instructors’ teaching in Saudi blended learning environments. TechTrends, 3(63), 341–352.10.1007/s11528-018-0342-1Search in Google Scholar

Alexander, B., Ashford-Rowe, K., Barajas-Murph, N., Dobbin, G. Knott, J., McCormack, M., … Weber, N. (2019). Horizon report 2019 higher education edition. EDU19. The Learning and Technology Library. Retrieved 29th July, 2021 from: https//www.learntechhlib.org/p/208644.Search in Google Scholar

Allan, C. N., Campbell, C., & Crough, J. (2019). Blended learning designs in STEM higher education: Putting learning first (1st ed.). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-6982-7.Search in Google Scholar

Alpha-plus. (2022). Defining blended learning in adult education. Accessed November 7, 2022 from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/blendedlearning/chapter/defining/.Search in Google Scholar

Armstrong, G. A. Marteau, J., Weinman, T., & Marteau, T. (1997). The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology 31(3), 1–6. doi: 10.1177/003803859703015.Search in Google Scholar

Ashrafi, A., Zareravasan, A., Rabiee Savoji, S., & Amani, M. (2020). Exploring factors Influencing students’ continuance intention to use the learning management system (LMS): A multi-perspective framework. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(8), 1–23.10.1080/10494820.2020.1734028Search in Google Scholar

BakarNordina, A., & Alias, N. (2013). Learning outcomes and students’ perceptions in using blended learning in history. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103(1), 577–585.10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.375Search in Google Scholar

Basilaia, G., & Kvavadze, D. (2020). Transition to online education in Schools during a SARS COV-2 Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 2–9.10.29333/pr/7937Search in Google Scholar

Biney, I. K. (2020). Experiences of adult learners on using the Sakai management learning system for learning in Ghana. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 26(2), 262–282. doi: 10.1177/1477971419864372.Search in Google Scholar

Biney, I. K. (2021). Revitalizing blended and self-directed learning among adult learners through the distance education mode of learning in Ghana. In C. Bosch, D. Laubscher, & L. Kyei-Blankson (Eds.), Re-envisioning and restructuring blended learning for under-privileged communities. IGI Global. doi: 10.4018978-1-6940-5-ch010.Search in Google Scholar

Biney, I. K. (2022). Experiences of adult learners engaged in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ghana. International Journal of Adult Education and Technology, 13(1), 1–15.10.4018/IJAET.310075Search in Google Scholar

Biney, I. K. (2023). The learning experiences of adult learners in a blended learning environment: Opportunities and challenges. In B. Daniel & R. Bisaso (Eds.), Higher education in sub-Saharan Africa in the 21st century-Pedagogy, research and community-engagement (pp. 389–410). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-3212-2.Search in Google Scholar

Bouchrika, I. (2020). 50 current student stress statistics: 2020/2021 data, analysis and prediction. Retrieved March 2, 2024 from https://research.com/education/student-stress-statistics.Search in Google Scholar

Bouchrika, I. (2024). The andragogy approach: Knowles adult learning theory principles in 2024. Retrieved February 15, 2024 from https://research.com/education/the-andragogy-approach.Search in Google Scholar

Bower, M., Dalgarno, B., Kennedy, G. E., Lee, M. J. W., & Kenney, J. (2015). Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous learning environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Computers & Education, 86, 1–17.10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.006Search in Google Scholar

Bridges, S., Green, J., Botelho, M. G., & Tsang, P. C. S. (2015). Blended learning and PBL: An interactional ethnographic approach to understanding knowledge construction in-situ. In A. Walker, H. Leary, C. Hmelo-Silver, & P. Ertmer (Eds.), Essential readings in problem-based learning (pp. 107–131). Purdue University Press.10.2307/j.ctt6wq6fh.13Search in Google Scholar

Bruggeman, B., Tondeur, J., Struyven, K., Pynoo, B., Garone, A., & Vanslambrouck, S. (2021), Experts speaking: Crucial teacher attributes for implementing blended learning in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 48, 1–11.10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100772Search in Google Scholar

Bustamante, J. (2020). Return to university classroom with blended learning: A possible post-pandemicÐ COVID-19 scenario. Accessed September, 2024 from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362106772_Return_to_University_Classrooms_with_blended_Learning_A_Possible_Post_pandemic_COVID-19_Scenario.Search in Google Scholar

Castaño-Muñoz, J., Duart, J. M., & Sancho-Vinuesa, T. (2014). The Internet in face-to-face higher education: Can interactive learning improve academic achievement? British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(1), 149–159.10.1111/bjet.12007Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research: Choosing among the five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.Search in Google Scholar

Cundell, A., & Sheepy, E. (2018). Student perceptions of the most effective and engaging online learning activities in a blended graduate seminar. Online Learning, 22(3), 87–102. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i3.1467.Search in Google Scholar

Deschacht, N., & Goeman, K. (2015). The effect of blended learning on course persistence and performance of adult learners: A difference-in-differences analysis. Computers & Education, 87, 83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.020.Search in Google Scholar

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5–22.10.1177/0047239520934018Search in Google Scholar

Edem Adzovie, D., & Jibril, A. B. (2022). Assessment of the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on the prospects of e-learning in higher learning institutions: The mediating role of academic innovativeness and technological growth. Cogent Education, 9(1), 204–222.10.1080/2331186X.2022.2041222Search in Google Scholar

Ellaway, R., & Masters, K. (2008). AMEE Guide 32: E-learning in medical education part 1: Learning, teaching and assessment. Medical Teacher, 30(5), 455–473. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 8(1), 77–101.10.1080/01421590802108331Search in Google Scholar

Garcia, A., Abrego, J., & Calvillo, M. (2014). A study of hybrid instructional delivery for graduate students in an educational leadership course. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 29(1), 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

Gewin, V. (2020). Five tips for moving teaching online as COVID-19 takes hold. Nature, 58(7802), 295–296.10.1038/d41586-020-00896-7Search in Google Scholar

Graham, C. R. (2013). Emerging practice and research in blended learning. In M. G. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education (3rd ed.). (pp. 333–350). Routledge.10.4324/9780203803738.ch21Search in Google Scholar

Graham, C. R., Allen, S., & Ure, D. (2005). Benefits and challenges of blended learning environments. In Encyclopedia of information science and technology (1st ed.) (pp. 253–259). IGI Global.10.4018/978-1-59140-553-5.ch047Search in Google Scholar

Hall, S., & Villareal, D. (2015). The hybrid advantage: Graduate student perspectives of hybrid education courses. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 27(1), 69–80.Search in Google Scholar

Hartree, A. (1984). Malcolm Knowles’ theory of andragogy: A critique. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 3(3), 203–210.10.1080/0260137840030304Search in Google Scholar

Henaku, E. A. (2020). COVID-19: Online learning experience of college students: The case of Ghana. Internatonal Jouranl of Multidiscipliary Sciences and Advanced Technology, 1(2), 54–62.Search in Google Scholar

Holley, D., & Oliver, M. (2010). Student engagement and blended learning: Portraits of risk. Computers & Education, 54(3), 693–700.10.1016/j.compedu.2009.08.035Search in Google Scholar

Hoq, M. Z. (2020). E-Learning during the period of pandemic (COVID-19) in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An empirical study. American Journal of Educational Research, 8(7), 457–464.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, C. S. (2017). Collaborative technologies, higher order thinking and self-sufficient learning: A case study of adult learners. Research in Learning Technology, 25, 1–17.10.25304/rlt.v25.1981Search in Google Scholar

King, K. P. (2017). Technology and innovation in adult learning. Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

King, S., & Arnold, K. (2012). Blended learning environments in higher education: A case study of how professors make it happen. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 25, 44–59.Search in Google Scholar

Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education; From pedagogy to andragogy. Englewood Cliffs: Cambridge.Search in Google Scholar

Knowles, M. S. (1989). The making of an adult educator. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Knowles, M. S. (1984). Andragogy in action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., III, Swanson, R. A., & Robinson, P. A. (2020). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (9th ed.). Routledge.10.4324/9780429299612Search in Google Scholar